Abstract

Patients with pathologic complete response (pCR) achievement can consider local excision or “watch and wait” strategy instead of a radical surgery. This study analyzed the predictive factors of pCR in rectal cancer patients who underwent radical operation after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT). This study also analyzed the recurrence patterns in patients who achieved pCR and the oncologic outcomes and prognostic factors by ypStage. Between 2000 and 2013, 1,089 consecutive rectal cancer patients who underwent radical resection after nCRT were analyzed. These patients were classified into two groups according to pCR. The clinicopathologic and oncologic outcomes were analyzed and compared between the two groups. Multivariate analysis was conducted on factors related to pCR. The proportion of patients achieving pCR was 18.2% (n = 198). The pCR group demonstrated earlier clinical T and N stages, smaller tumor size, better differentiation, and a lower percentage of circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement than did the non-pCR group. The prognostic factors associated with poorer disease-free survival were high preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen levels, non-pCR, poor histology, lymphatic/perineural invasion, and involvement of CRM. Multivariate analysis revealed that clinical node negativity, tumor size < 4 cm, and well differentiation were significant independent clinical predictors for achieving pCR. Patients with pCR displayed better long-term outcomes than those with non-pCR. The pCR-prediction model, based on predictive factors, is potentially useful for prognosis and for prescribing a treatment strategy in patients with advanced rectal cancer who need nCRT.

Subject terms: Colorectal cancer, Surgical oncology

Introduction

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, patients with advanced rectal cancer are initially treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT)1. The purpose of nCRT in rectal cancer patients is to increase the rate of radical resection and sphincter-saving and decrease the rate of local recurrence2. The incidence of a pathologic complete response (pCR) ranges from 10 to 30% and has been associated with favorable oncological outcomes3–7. Total mesorectal excision (TME) is considered the standard method of rectal cancer surgery. It may lead to urinary and sexual dysfunction and the possibility of stoma formation8,9. Recently, studies have reported on patients who achieved clinical complete response (cCR) after nCRT using the “watch-and-wait” approach instead of destructive surgery3,10,11. Therefore, it is imperative to determine the predictive factors for pCR in order to select patients eligible for the “watch-and-wait” approach. It is also necessary to determine whether the oncologic outcomes of patients with pCR are actually better than those of those with non-pCR. Several studies have reported on predictive factors for pCR and the oncological outcomes of patients who achieved pCR12. However, few studies predict pCR based on clinical factors.

The purpose of this study was to analyze the predictive clinical factors of pCR in patients with rectal cancer who had undergone radical surgery after nCRT. This study also analyzed the recurrence patterns in patients who had achieved pCR as well as the oncologic outcomes and prognostic factors by ypStage.

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients according to the pCR

Among the 1,089 patients in this study, the proportion of pCR patients was 18.2% (n = 198). The clinicopathological features of all patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, sex, preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, TME grade, and vascular invasion between the pCR and non-pCR groups. However, there were statistically significant differences in histology (P < 0.001), clinical T stage (P = 0.007), and N stage (P = 0.030). There was no difference between the two groups in preoperative treatment-related factors. Similar results were shown between the two groups at the interval between nCRT and surgery (P = 0.710), neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen (P = 0.683), and neoadjvuant radiotherapy dose (P = 0.774).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients.

| ypCR (n = 198) |

Non-ypCR (n = 891 ) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ( years, median±SD) | 55±11 | 56±11 | 0.264 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7±3.0 | 23.8±3.0 | <0.001 |

| Gender, n(%) | 0.748 | ||

| Male | 133 (67.2) | 609 (68.4) | |

| Female | 65 (32.8) | 282 (31.6) | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.151 | ||

| <5 | 192 (97.0) | 842 (94.5) | |

| ≥5 | 6 (3.0) | 49 (5.5) | |

| Mean height from AV (cm) | 4.4±1.9 | 4.3±2.3 | 0.187 |

| Clinical T stage, n(%) | 0.007 | ||

| cT1 | 2 (1.0) | 3(0.3) | |

| cT2 | 24 (12.1) | 104 (11.7) | |

| cT3 | 158 (79.8) | 640 (71.8) | |

| cT4 | 14 (7.1) | 144 (16.2) | |

| Clinical N stage, n(%) | 0.030 | ||

| cN negative | 63 (31.8) | 217 (24.4) | |

| cN positive | 135 (68.2) | 674 (75.6) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen | 0.683 | ||

| Xeloda | 95 (48.0) | 389 (43.7) | |

| 5-FU | 66 (33.3) | 321 (36.0) | |

| FL | 32 (16.2) | 162 (18.2) | |

| Others | 5 (2.5) | 19 (2.1) | |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy dose | 0.774 | ||

| 5040Gy | 172 (86.9) | 790 (88.7) | |

| 5400Gy | 6 (3.0) | 24 (2.7) | |

|

Others nCRT-operative inveraval (days) |

20 (10.1) 54±7 |

77 (8.6) 54±11 |

0.710 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy, n(%) | 175 (88.4) | 836 (93.8) | 0.007 |

| Pretreatment Cell differentiation, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| Well differentiated | 90 (45.4) | 132 (14.8) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 95 (48.0) | 671 (75.3) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 10 (5.1) | 26 (2.9) | |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 2 (1.0) | 7 (0.8) | |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 1 (0.5) | 55 (6.2) | |

| Pathologic T stage, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| ypT0 | 198 (100.0) | 15 (1.7) | |

| ypT1 | 0 (0.0) | 49 (5.5) | |

| ypT2 | 0 (0.0) | 312 (35.0) | |

| ypT3 | 0 (0.0) | 492 (55.2) | |

| ypT4 | 0 (0.0) | 23 (2.6) | |

| Pathologic N stage, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| ypN0 | 198 (100.0) | 574 (64.4) | |

| ypN1 | 0 (0.0) | 237 (26.6) | |

| ypN2 | 0 (0.0) | 80 (9.0) | |

| Tumor regression grade, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.9) | |

| Minimal | 0 (0.0) | 276 (31.0) | |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0) | 600 (67.3) | |

| Near complete | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.8) | |

| Complete | 198 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lymph node harvest, n(%) | 0.006 | ||

| >12 | 135 (68.2) | 513 (57.6) | |

| ≤12 | 63 (31.8) | 378 (42.4) | |

| Mean tumor size (cm) | 2.0±1.0 | 2.7±1.5 | <0.001 |

| CRM involvement, n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 43 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Distal resection involvement, n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0.669 |

| TME grade, n(%) | 0.453 | ||

| Complete | 197 (99.5) | 889 (99.8) | |

| Incomplete | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Lymphatic invasion, n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 128 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Perineural invasion, n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 107 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| Vascular invasion, n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 83 (9.3) | <0.001 |

BMI body mass index, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, AV anal verge, 5-FU fluorouracil, FL fluorouracil/leucovorin, nCRT neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, CRM circumferential resection margin, TME total mesorectal excision.

In terms of perioperative outcomes, as shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences between the two groups.

Table 2.

Perioperative results of the patients according to the pCR.

| ypCR (n = 198) |

Non-ypCR (n = 891) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical approach | 0.830 | ||

| Open | 134 (67.7) | 610 (68.5) | |

| MIS | 64 (32.3) | 281 (31.5) | |

| Name of operation | 0.055 | ||

| LAR | 175 (88.4) | 721 (80.9) | |

| ISR | 7 (3.5) | 65 (7.3) | |

| APR | 14 (7.1) | 78 (8.8) | |

| Hartmann operation | 2 (1.0) | 27 (3.0) | |

| Mean operation time (min) | 178±60 | 183±70 | 0.359 |

| Diverting stoma, n(%) | 91 (46.0) | 410 (46.0) | 1.000 |

| Open conversion, n(%) | 2 (1.6) | 10 (1.6) | 1.000 |

| Intraoperative transfusion, n(%) | 0.019 | ||

| (+) | 1 (0.5) | 33 (3.7) | |

| (-) | 197 (99.5) | 858 (96.3) | |

| Length of stay (days) | 11±8 | 12±8 | 0.699 |

| Postoperative complications, n(%) | 55 (27.8) | 259 (29.1) | 0.848 |

| Surgical complications | 51 (92.7) | 237 (91.5) | |

| Non-surgical complications | 2 (3.6) | 8 (3.1) | |

| Both | 2 (3.6) | 14 (5.4) | |

| Surgical complications | |||

| Anastomotic leakage | 11 (5.6) | 58 (6.5) | 0.618 |

| Rectovaginal fistula | 3 (1.5) | 10 (1.1) | 0.715 |

| Postoperative ileus | 15 (7.6) | 83 (9.3) | 0.439 |

| Urinary retention | 10 (5.1) | 61 (6.8) | 0.427 |

| Superficial surgical site infection | 13 (6.6) | 51 (5.7) | 0.649 |

| Intraabdominal bleeding | 3 (1.5) | 12 (1.3) | 0.743 |

| Intraluminal bleeding | 1 (0.5) | 10 (1.1) | 0.700 |

| Clavien-Dindo classification | 1.000 | ||

| I-II | 41 (74.5) | 193 (74.5) | |

| III-IV | 14 (25.5) | 66 (25.5) | |

| Postoperative mortality (<30days), n(%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | 0.547 |

CR complete response, MIS minimally invasive surgery, LAR low anterior resection, ISR intersphincteric resection, APR abdominoperineal resection.

As can be seen from Table 2, there was also no significant difference in surgical procedures, such as open or minimally invasive surgery, operation time, and rate of diverting stoma between the two groups.

Survival according to response to neoadjuvant treatment and pCR

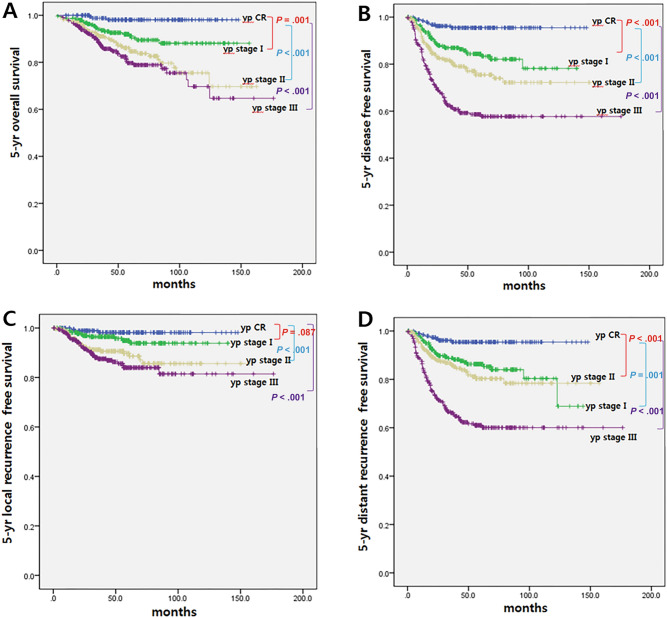

Figure 1 shows the survival rates according to the ypStage. The 5-yr overall survival (OS), 5-yr disease-free survival (DFS), and 5-yr local recurrence-free survival (LRFS) showed statistically significant differences by ypStage. To identify the impact of pCR on oncologic outcomes, we analyzed 5-yr OS, 5-yr DFS, 5-yr LRFS, and 5-yr distant recurrence-free survival (DRFS) rates according to ypStage. In the pCR group, 5-yr OS was 98.1%, 5-yr DFS was 95.5%, 5-yr LRFS was 98.2%, and 5-yr DRFS was 95.4%, which were the highest statistically significant values compared to those of other ypStages.

Figure 1.

Survival according to response to neoadjuvant treatment. (A) 5-yr overall survival (B) 5-yr disease free survival (C) 5-yr local recurrence free survival (D) 5-yr distant recurrence free survival.

Prognostic factors of OS and DFS

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the value of pCR as an independent prognostic factor with respect to 5-yr OS and 5-yr DFS. From univariate analysis (Table 3), factors associated with poor overall survival included age ≥ 65 years, high preoperative CEA level, clinical node positivity, non-pCR, ypII–III, poor histology, and perineural invasion. In multivariate analysis, high preoperative CEA level, clinical node positivity, non-pCR, ypII–III, poor histology, and perineural invasion were associated with poor overall survival.

Table 3.

Prognostic factors of OS, DFS, and LRFS.

| Factors | Overall survival | Disease free survival | Local recurrence free survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| P | HR (95% CI) | P | P | HR (95% CI) | P | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Preoperative CEA (mg/ml) | |||||||||

| ≥5 versus <5 | 0.036 | 2.727 (1.630-4.563) | <0.001 | 0.022 | 3.269 (1.078-9.920) | 0.036 | 0.022 | 1.071 (0.582-1.969) | 0.825 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| ≥60 versus <60 | 0.035 | 1.585 (1.112-2.258) | 0.011 | 0.272 | 0.272 | 0.334 | |||

| Surgical approach | 1.150 (0.866-1.527) | ||||||||

| Open versus MIS | 0.150 | 0.882 | 0.882 | ||||||

| Type of operation | |||||||||

| SSS versus Non-SSS | 0.563 | 0.294 | 0.294 | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female versus male | 0.212 | 0.642 | 0.642 | ||||||

| Clinical T stages | |||||||||

| 2 versus 1 | 0.937 | 0.954 | 0.954 | ||||||

| 3 versus 1 | 0.946 | 0.949 | 0.949 | ||||||

| 4 versus 1 | 0.928 | 0.946 | 0.946 | ||||||

| Clinical N stages | |||||||||

| Positive versus negative | 0.141 | 0.703 | 0.703 | ||||||

| Pathologic CR | |||||||||

| No versus yes | 0.046 | 9.973 (3.171-31.366) | <0.001 | 0.037 | 6.972 (3.442-14.120) | <0.001 | 0.037 | <0.001 | |

| ypII-III versus yp0-I | 0.817 | 0.282 | 0.282 | ||||||

| Cell differentiation | 6.049 (2.981- | ||||||||

| PD/MUC/SRC versus | 0.003 | 3.311 (2.180-5.027) | <0.001 | 0.003 | 1.665 (1.127-2.459) | 0.010 | 0.455 | 12.273) | |

| WD/MD | |||||||||

| Lymphatic invasion | |||||||||

| Yes versus no | 0.616 | 0.062 | 0.062 | ||||||

| Venous invasion | |||||||||

| Yes versus no | 0.732 | 0.350 | 0.350 | ||||||

| Perineural invasion | |||||||||

| Yes versus no | 0.022 | 2.583 (1.576-4.234) | <0.001 | 0.035 | 2.848 (2.032-3.991) | <0.001 | 0.035 | <0.001 | |

| CRM involvement | |||||||||

| Yes versus no | 0.524 | 0.050 | 2.307 (1.387-3.838) | 0.001 | 0.058 | 2.858 (1.995-4.095) | 0.498 | ||

| Lymph node harvest | 0.297 | 0.025 | 0.900 (0.691-1.173) | 0.437 | 0.025 | ||||

| >12 versus ≤12 | 0.907 (0.684-1.203) | ||||||||

| Postoperative complications | 0.899 | 0.805 | 0.805 | ||||||

| CDC III-IV versus I-II | |||||||||

| Adjuvant treatment | |||||||||

| Yes versus no | 0.160 | 0.346 | 0.346 | ||||||

LRFS local recurrence free survival, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, CR complete response, PD poorly differentiated, MUC mucinous carcinoma, SRC signet ring cell carcinoma, WD well differentiated, MD moderately differentiated, CRM circumferential resection margin, MIS minimally invasive surgery, SSS sphincter saving surgery, CDC Clavien-Dindo Classification.

The results were similar with respect to DFS. In multivariate analysis, high preoperative CEA level, non-pCR, poor histology, lymphatic invasion, perineural invasion, and CRM involvement were associated with poor DFS (Table 3).

Predictive factors of pCR and ypIII

Several pretreatment clinical factors were analyzed to identify the predictive factors of pCR (Table 4). Factors that were significantly associated with the achievement of a pCR were smaller tumor size (< 4 cm), clinical node negativity, and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Table 4.

Predictor factors of ypCR and yp stage III.

| ypCR | yp stageIII | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| p | OR (95% CI) | p | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Initial CEA (ng/l) | ||||||

| ≥5 versus <5 | 0.306 | 0.046 | 1.809 (1.041-3.144) | 0.035 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≥60 versus <60 | 0.238 | 0.894 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female versus male | 0.594 | 0.260 | ||||

| Mean height from AV (cm) | ||||||

| ≥5 versus <5 | 0.491 | 0.306 | ||||

| Pretreatment tumor size (cm) | ||||||

| <0.001 | 0.228 (0.136-0.383) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2.010 (1.508-2.679) | <0.001 | |

| ≥4 versus <4 | ||||||

| Clinical T stages | 0.189 | 0.107 | ||||

| 2 versus 1 | 0.559 | 0.306 | ||||

|

3 versus 1 4 versus 1 |

0.080 | 0.751 | ||||

|

Clinical N stages Positive versus negative |

0.010 | 0.690 (0.493-0.965) | 0.030 | <0.001 | 2.200 (1.570-3.081) | <0.001 |

| Cell differentiation | <0.01 | 0.027 (0.004-0.196) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.461 (2.236-5.355) | <0.001 |

| MD versus WD | 0.004 | 0.128 (0.018-0.939) | 0.043 | <0.001 | 7.538 (3.488-16.295) | |

| PD versus WD | 0.005 | <0.001 | ||||

| SRC versus WD | 0.001 | 0.047 (0.006-0.389) | 0.033 | 0.010 | 6.031 (1.522-23.899) | 0.011 |

| MUC versus WD | 0.001 | 0.064 (0.005-0.796) | <0.001 | 7.538 (3.878-14.653) | <0.011 | |

CR complete response, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, AV anal verge, WD well differentiated, MD moderately differentiated, PD poorly differentiated, MUC mucinous carcinoma, SRC signet ring cell carcinoma.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were also performed to evaluate the risk factors associated with ypIII. On univariate analysis (Table 4), factors associated with ypIII included high preoperative CEA level, tumor size > 4 cm, clinical node positivity, and poor histology. Figure 2 shows the ROC curve based on factors such as age (60 years), sex, preoperative CEA level, clinical T and N stage, tumor location (AV 5 cm), tumor size (4 cm), and cell differentiation as well as the graph for application to the validation model (Fig. 2). We also grouped well differentiated and moderately differentiated together to analyze the prediction model and apply it to the validation model. The AUC value decreased slightly, but similar results were shown (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

ROC curve for ypCR and validation model.

Figure 3.

ROC curve for ypCR and validation model. Well differentiated and moderately differentiaed into groups.

Patterns of recurrence in pCR

Eight (4.0%) out of 198 patients with pCR had recurrence. Local recurrence, on the lateral pelvic side wall, occurred in 1 patient; distant metastasis occurred in 6 patients (5 lung metastases, 1 liver metastasis, and 1 bone metastasis); and concurrent local recurrence and distant metastasis in 1 patient. The characteristics of these 8 patients are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Details of the 8 patients with recurrence after achieving pCR.

| Age | Sex | Clinical staging | Tumor location from AV (cm) | CTx | RTx dose (Gy) | nCRT-surgery interval (wks) | Surgery | No.of harvested LNs | Cell diff | Adjuvant CTx | Location of recurrence | Treatment after recurrence | RFS (mon) | Death | OS (mon) | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | M | T4N1 | 1 | 5-FU | 45.0 | 6 | APR | 4 | WD | No | Pelvic/lung | CTx | 17.0 | Y | 40.5 | Death |

| 76 | M | T3N2 | 3 | FL | 50.4 | 6 | ISR | 10 | WD | FL | Pelvic | No | 14.4 | N | 69.2 | Alive |

| 51 | M | T3N1 | 3 | 5-FU | 50.4 | 6 | ISR | 6 | MD | 5-FU | Lung | Op, CTx | 36.0 | N | 53.0 | Alive |

| 59 | M | T3N1 | 6 | Xeloda | 50.4 | 7 | LAR | 13 | MD | 5-FU | Bone | RTx | 5.4 | Y | 28.1 | Death |

| 65 | M | T3N1 | 2 | FL | 50.4 | 6 | ISR | 8 | WD | No | Lung | Op, CTx | 11.7 | N | 36.8 | Alive |

| 58 | M | T3N2 | 2 | Xeloda | 50.4 | 8 | ISR | 13 | WD | No | Lung | No | 6.3 | N | 7.7 | Alive |

| 72 | M | T3N2 | 3 | Xeloda | 50.4 | 6 | ISR | 3 | MD | No | Lung | Op | 19.0 | N | 55.9 | Alive |

| 59 | M | T3N2 | 5 | FL | 54.0 | 7 | LAR | 3 | MD | FL | Liver | RFA | 23.1 | N | 26.5 | Alive |

CR complete response, AV anal verge, CTx chemotherapy, Op operation, 5-FU fluorouracil, FL fluorouracil/leucovorin, RTx radiotherapy, nCRT neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, APR abdominoperineal resection, ISR intersphincteric resection, LAR low anterior resection, diff differentiation, WD well differentiated, MD moderately differentiated, RFA radiofrequency ablation, RFS recurrence free survival, OS overall survival.

Discussion

In other studies, the rates of pCR after nCRT for rectal cancer are various from 10 to 30%4,13,14. In this study, the rate of non-metastatic rectal cancer patients who achieved pCR between 2000 and 2013 was 18.2%. We have identified several pretreatment clinical factors, such as tumor size ˂ 4 cm, clinical node negativity, and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma that can predict pCR. Several studies have reported various useful predictive factors for pCR, such as cell differentiation, tumor size, preoperative CEA level, and clinical T and N stages14–18. Understanding these factors can lead to the establishment of a treatment strategy for rectal cancer. Patients with high pCR achievement can consider local excision or the “watch and wait” strategy instead of a radical surgery. In contrast, more aggressive neoadjuvant treatment may be considered for patients with lower pCR prediction3,10,11,19,20.

In this study, univariate analysis revealed that clinical N-positive stage, tumor size ˃ 4 cm, and poorly differentiated tumors were significantly associated with lower odds of pCR and higher odds of ypIII. These results potentially assist in predicting response to nCRT and, on this premise, allow a more accurate prediction of patients likely to achieve pCR. Currently, “watch and wait” is not a routine procedure in our hospital. We have reserved “watch and wait” for patients with comorbidities or those with cCR, after sufficient explanation and informed consent, including the possibility of recurrence and frequent follow-up.

The present study also demonstrated better oncologic outcomes in patients who achieved pCR than in those who did not. This result corroborates those of previous studies, which reported that patients who achieved pCR showed better oncologic outcomes3,4. The finding that the prognosis of a patient with pCR is better than that of one without pCR suggests that it is important to achieve pCR. In patients who have predictive factors for poor response to nCRT, such as large tumor size, advanced clinical node stage, and aggressive histology, aggressive neoadjuvant treatment may be a preferred option, such as increased radiation dose or boosts or additional chemotherapy.

Although several patients achieved pCR after nCRT and radical surgery, some of them were at risk of recurrence, and, overall, recurrence occurred in 8 patients (4.0%) with pCR after TME in this analysis. One patient developed local recurrence, while distant metastases occurred in 6 patients, and one patient had both local and distant recurrence. The individual data of these 8 recurrent patients did not help in explaining these local and distant recurrences. It was difficult to analyze statistically significant prognostic factors because there were fewer cases of recurrence. However, we observed that distant metastases were the major recurrence pattern in patients who had achieved pCR after nCRT, which concurs with the findings of other studies6,21,22. The patients with recurrence had the following features: clinical T3–4 tumors and node positivity, tumor location from the anal verge lower than 5 cm, and history of intersphincteric resection. Four of the patients with recurrent metastases received adjuvant chemotherapy, and the other four did not. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with pCR following nCRT and radical resection is still not entirely clear. However, we consider administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with these factors, even for those who have achieved pCR following nCRT and radical resection.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective and single-center design. Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to propose predictive factors for pCR and predictive models based on ypCR. Furthermore, this study analyzed the oncologic outcomes of pCR, which could offer a treatment strategy for rectal cancer. Less invasive methods, such as “watch and wait,” may be considered for those who are predicted to achieve pCR, whereas more aggressive neoadjuvant treatment, including increased radiation dose or induction/consolidation chemotherapy, could be considered for patients at high risk of ypIII.

In conclusion, the factors significantly associated with the achievement of a pCR were smaller tumor size (< 4 cm), clinical node-negativity, and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Patients with pCR displayed better long-term outcomes than those with non-pCR. The pCR-prediction model, based on predictive factors, is potentially useful for prognosis and for prescribing a treatment strategy in patients with advanced rectal cancer who need nCRT.

Patients and methods

Between January 2000 and December 2013, a total of 1,089 patients with primary rectal cancer received nCRT followed by radical resection at a single institution. Patients who had undergone radical resection were included if they had biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma of the rectum ≤ 10 cm from the anal verge. Patients were excluded if they had recurrent or metastatic cancer, previous chemotherapy or pelvic radiotherapy, hereditary rectal cancer, or local excision. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine (IRB No. SMC 2019-10-134-001). Since it was a retrospective study through medical charts, the need for written informed consent was waived by the IRB of Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine.

All patients underwent preoperative staging with rectal magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans of the abdominopelvic and thoracic cavities. Tumor size and lymph node metastasis were measured through rectum or pelvic MRI performed at the time of diagnosis. The size of tumor was measured by longitudinal tumor size on MRI. Lymph node metastasis was determined based on size, irregular margin, and heterogenic signal intensity. The above results were officially reported by a radiologist specializing in colorectal cancer. Patients with clinical T3 and higher or with clinical nodal involvement received nCRT. The chemoradiation regimen consisted of long-course radiation with 4500–5400 cGy over 5–6 weeks with synchronous intravenous 5-fluorouracil, Xeloda, or FL (FL fluorouracil/leucovorin) chemotherapy. Surgery was performed–6–8 weeks after completion of chemoradiation. Postoperative chemotherapy after radical resection was recommended for all patients.

The macroscopic quality of TME specimens was assessed by a single pathologist specializing in colorectal disease immediate after surgery according to the grading system used by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z605123.

There are three pathologists specializing in colorectal cancer who analyze specimens with microscope and report the final pathological staging. A positive circumferential resection margin (CRM) was defined as a distance ≤ 1 mm between the deepest tumor invasion and the mesorectal fascia24.

The stage was determined according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual25. A pCR was defined as the absence of viable cancer cells observed in the specimen after radical resection. We used the Dworak system to determine the degree of tumor regression, which ranges from GR 0 (abscess of regression) to GR 4 (complete regression)26.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis. The chi-square test, Mann–Whitney U test, or Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze the differences between the two groups. The Kaplan–Meier method was used for survival rate analysis. Multivariate analyses were performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. Clinical factors were then subjected to stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Author contributions

Study design: J.K.S., Jung Wook Huh; Data acquisition: J.K.S., J.W.H., Y.A.P.; Data analysis and interpretation: J.K.S., J.W.H., H.C.K.; Manuscript preparation: J.K.S., J.W.H., Y.B.C.; Manuscript editing: J.K.S., J.W.H., S.H.Y.; Manuscript review: J.K.S., J.W.H., W.Y.L.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Rectal cancer, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2018;16(7):874–901. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(6):575–582. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maas M, Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(35):4633–4640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.7176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(9):835–844. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(34):8688–8696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Campos-Lobato LF, Stocchi L, da Luz MA, et al. Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer decreases distant recurrence and could eradicate local recurrence. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011;18(6):1590–1598. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park IJ, You YN, Agarwal A, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment response as an early response indicator for patients with rectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(15):1770–1776. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1(8496):1479–1482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snijders HS, Bakker IS, Dekker JW, et al. High 1-year complication rate after anterior resection for rectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014;18(4):831–838. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: Long-term results. Ann. Surg. 2004;240(4):711–717. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141194.27992.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beets GL. Critical appraisal of the 'wait and see' approach in rectal cancer for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation (Br J Surg 2012; 99: 897–909) Br. J. Surg. 2012;99(7):910. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan WH, Xiao J, An X, et al. Patterns of recurrence in patients achieving pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017;143(8):1461–1467. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorimer PD, Motz BM, Kirks RC, et al. Pathologic complete response rates after neoadjuvant treatment in rectal cancer: An analysis of the national cancer database. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017;24(8):2095–2103. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huh JW, Kim HR, Kim YJ. Clinical prediction of pathological complete response after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2013;56(6):698–703. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182837e5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan Y, Fu D, Li D, et al. Predictors and risk factors of pathologic complete response following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: A population-based analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:497. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zorcolo L, Rosman AS, Restivo A, et al. Complete pathologic response after combined modality treatment for rectal cancer and long-term survival: A meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012;19(9):2822–2832. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith FM, Winter D. Pathologic complete response of primary tumor following preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: Long-term outcomes and prognostic significance of pathologic Nodal Status (KROG 09–01) Ann. Surg. 2017;265(4):e27–e28. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolthuis AM, Penninckx F, Haustermans K, et al. Impact of interval between neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and TME for locally advanced rectal cancer on pathologic response and oncologic outcome. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012;19(9):2833–2841. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huh JW, Jung EJ, Park YA, Lee KY, Sohn SK. Preoperative chemoradiation followed by transanal excision for rectal cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2008;148(2):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim CJ, Yeatman TJ, Coppola D, et al. Local excision of T2 and T3 rectal cancers after downstaging chemoradiation. Ann. Surg. 2001;234(3):352–358. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200109000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith KD, Tan D, Das P, et al. Clinical significance of acellular mucin in rectal adenocarcinoma patients with a pathologic complete response to preoperative chemoradiation. Ann. Surg. 2010;251(2):261–264. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bdfc27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capirci C, Valentini V, Cionini L, et al. Prognostic value of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: Long-term analysis of 566 ypCR patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008;72(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, van der Worp E, et al. Macroscopic evaluation of rectal cancer resection specimen: Clinical significance of the pathologist in quality control. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20(7):1729–1734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JS, Huh JW, Park YA, et al. A circumferential resection margin of 1 mm is a negative prognostic factor in rectal cancer patients with and without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2014;57(8):933–940. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiser MR. AJCC 8th edition: Colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018;25(6):1454–1455. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dworak O, Keilholz L, Hoffmann A. Pathological features of rectal cancer after preoperative radiochemotherapy. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 1997;12(1):19–23. doi: 10.1007/s003840050072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]