Abstract

Conventional synthetic methods to yield polycyclic heteroarenes have largely relied on metal-mediated arylation reactions requiring pre-functionalised substrates. However, the functionalisation of unactivated azines has been restricted because of their intrinsic low reactivity. Herein, we report a transition-metal-free, radical relay π-extension approach to produce N-doped polycyclic aromatic compounds directly from simple azines and cyclic iodonium salts. Mechanistic and electron paramagnetic resonance studies provide evidence for the in situ generation of organic electron donors, while chemical trapping and electrochemical experiments implicate an iodanyl radical intermediate serving as a formal biaryl radical equivalent. This intermediate, formed by one-electron reduction of the cyclic iodonium salt, acts as the key intermediate driving the Minisci-type arylation reaction. The synthetic utility of this radical-based annulative π-extension method is highlighted by the preparation of an N-doped heptacyclic nanographene fragment through fourfold C–H arylation.

Subject terms: Organocatalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

The functionalisation of unactivated azines has been restricted because of their intrinsic low reactivity. Here the authors show a transition-metal-free, radical relay π-extension approach to produce N-doped polycyclic aromatic compounds directly from simple azines and cyclic iodonium salts.

Introduction

Polycyclic arenes have received considerable attention not only in the synthetic chemistry community but also in the chemical industry because of their controllable electronic, electrochemical, and photophysical properties1–5. While the preparation of such compounds, including nanographene segments, can, in principle, be achieved in a top-down manner from bulk materials or in a bottom-up approach from molecular building blocks, the bottom-up assembly is advantageous, because it allows for the precise control of molecular size and structure6–9. Transition-metal-catalysed cross-coupling and C–H arylation reactions have been extensively explored in the synthesis of structurally well-defined polycyclic arenes10–18. However, these methods require multistep procedures, including halogenation or metalation reactions, to pre-functionalize substrates. In addition, the assembled, arylated products must be converted into the fully fused polycyclic arenes by intramolecular dehydrogenative oxidation (Scholl reaction)19.

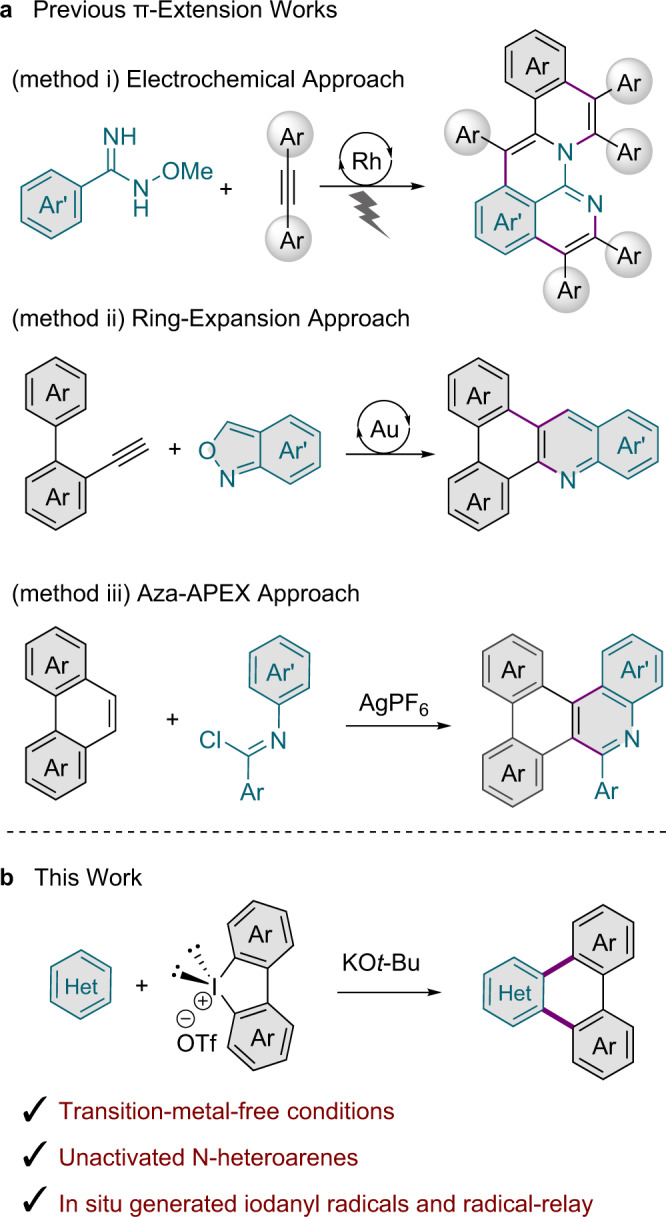

Metal-catalysed annulative π-extension (APEX) reactions are regarded as an appealing approach for rapidly constructing polycyclic arenes20–23, while obviating the need for pre-activation of substrates and Scholl oxidation. Recently, synthetic methods to produce N-doped polycyclic aromatic compounds (N-PACs) through π-extension chemistry have also been reported. Heteroatoms embedded within π-conjugated systems can alter their topology, band gap, and optoelectronic and electrochemical properties24. Ackermann and colleagues developed a Rh-electrocatalytic C–H functionalisation method (Fig. 1a, method (i)) that uses directing-group-bearing arene substrates and alkynes25. Hashimi et al. reported a gold-catalysed ring-expansion using o-ethynylbiaryls as π-extension agents (Fig. 1a, method (ii))26. Additionally, the Itami group described an aza-annulative approach (Fig. 1a, method (iii)) facilitating the extension of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in their K-region positions27. However, these methods have still been limited to electron-rich (hetero)arene substrates and require the aid of transition-metal catalysis or silver-assisted oxidation.

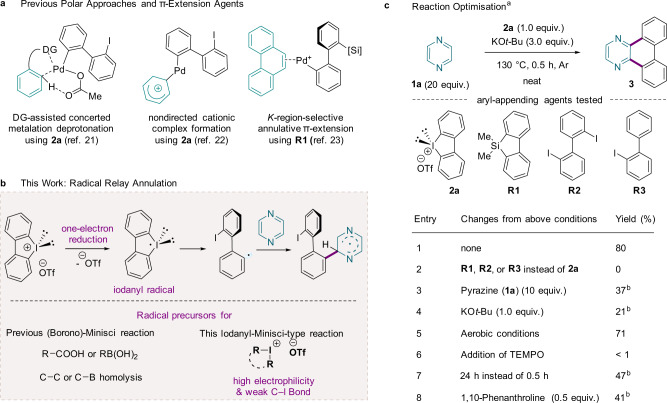

Fig. 1. Annulative strategies to access polycyclic heteroaromatic systems.

a Previous π-extension works. b This work: iodanyl-Minisci-type radical approach.

Azines, six-membered-ring heteroarenes bearing nitrogen atom(s), are privileged structural moieties in biological science, pharmaceutical industry, and materials chemistry28. Despite significant progress, annulative transformations of unactivated, simple azines, free of pre-installed functional groups, remain a highly challenging topic because of their electron-deficient character and potential for undesired coordination29,30. Herein, we show the direct transformation of simple and electron-deficient heteroarenes to N-PACs based on an APEX reaction that is initiated by electron transfer and proceeds through radical relay events akin to the Minisci reaction (Fig. 1b).

Results and discussion

Development and optimisation

To develop a method for the synthesis of N-PACs from electron-deficient heteroarenes, we initially sought to extend existing metal-catalysed APEX reactions to the annulation of pyrazine (1a). In particular, we attempted to apply Itami’s cationic-palladium-catalysed K-region-selective APEX method, our directing-group-assisted palladium-catalysed APEX method, and an acid-promoted electrophilic APEX method (Fig. 2a; see also Supplementary Information Section 1.4)21–23. However, these methods failed to yield the target product 3, which was likely due to catalyst deactivation.

Fig. 2. Polar versus radical annulation approaches.

a Transition-metal-catalysed polar annulation approaches. b Transition-metal-free radical relay annulation approach, wherein an in situ generated iodanyl radical directly activates a C–H bond of an unactivated azine. c Reaction optimisation. aStandard reaction conditions: 1a (4.0 mmol, 20 equiv.), 2a (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), KOt-Bu (0.60 mmol, 3.0 equiv.) at 130 °C under Ar for 0.5 h. Isolated yields. bGC yields using n-dodecane as an internal standard. DG directing group; −OTf triflate (CF3SO3−); KOt-Bu potassium tert-butoxide.

Inspired by the recently developed organocatalytic methods for the construction of biaryl moieties through aryl radical species31–40, we then considered radical reactions as an alternative to polar reactions. In base-promoted homolytic aromatic substitution (BHAS) or unimolecular radical nucleophilic substitution (SRN1) reactions, aryl radicals are generated by single-electron transfer (SET) from organic electron donors (OEDs) to aryl halides. As π-extension agents, cyclic diaryliodonium salts21,22 and dibenzosilole derivatives23 have been successfully applied in both directed and nondirected C–H annulations (Fig. 2a). Given the enhanced electrophilic character as well as the weak C–I bond of hypervalent iodine(III) reagents41–45, we surmised that an iodanyl radical may be generated from a cyclic iodonium salt through one-electron reduction and may act as a formal biaryl radical equivalent. Coupling of a C-centred radical, formed through subsequent homolysis of the C–I bond, with an unactivated azine may then give a heteroarene radical through an iodanyl-Minisci-type radical relay reaction (Fig. 2b).

Therefore, we examined transition-metal-free screening conditions for the annulation of 1a by varying the base, organic additive, aryl-appending partner, solvent, and reaction temperature (see also the Supplementary Information, Section 1.5). Remarkably, the use of potassium tert-butoxide (KOt-Bu) and cyclic diphenyliodonium salt 2a at 130 °C yielded the desired dibenzo[f,h]quinoxaline (3) in 80% yield (entry 1 in Fig. 2c). Intriguingly, other aryl-appending agents (R1, R2, and R3) failed to deliver the target compound, indicating the importance of iodonium salt 2a (entry 2). 1a was used not only as the substrate but also as the solvent, and an excess of it (20 equiv.) was required for optimal yield (entry 3). The use of KOt-Bu (3.0 equiv.) was determined to be crucial, because reducing its amount or replacing it with other bases significantly diminished the product yields (entry 4; see also Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Under aerobic conditions the APEX product 3 was obtained in a slightly reduced yield (entry 5). However, the addition of 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) inhibited the reaction, indicating the involvement of a radical pathway in this annulation (entry 6). A longer reaction time lowered the yield (entry 7; see also Supplementary Table 4). Organic additives, including 1,10-phenanthroline and its derivatives, did not improve the reaction efficiency (entry 8; see also Supplementary Table 6), consistent with a role of 1a as an inherent additive that produces OEDs in the presence of KOt-Bu.

Scope of the reaction

A series of iodonium salts (2) was explored using this protocol (Fig. 3a). While a fluorine-substituted aryl-transfer reagent gave 4 in a decreased yield, a broad range of alkyl- and aryl-substituted cyclic diaryliodonium salts tolerated the annulation conditions and provided the corresponding products (5–11) in moderate yields. Various electron-rich and electron-deficient heterocyclic iodonium salts were also subjected to the reaction conditions to yield the desired π-extended N-PACs (12–15). However, a six-membered cyclic iodonium salt did not operate with this protocol and failed to produce the corresponding product (16). Substituted azines gave products 17–23' in diminished yields, and quinoxaline provided the site-selectively annulated product 24 in 53% yield. Furthermore, we also conducted additional substrate scope studies using quinoxaline (see also the Supplementary Information, Section 1.6.2). The desired products were observed, and interestingly the reactivity pattern of this radical APEX strategy involving the azine-moiety activation within the quinoxaline framework is complementary to Itami’s M-region APEX46 that operates through a two-step dearomatization-annulation approach. This annulation protocol not only is compatible with simple azines but can also be amended to unactivated benzene to produce the PACs 25–32. These reactions were performed with 1a as an additive (2 equiv.) to provide a pathway for OED formation (vide infra). Notably, products 30 and 31 were inaccessible through direct C–H arylation reactions22. APEX reactions to access well-defined PACs or N-PACs typically have low-to-moderate yields because they (i) employ unfunctionalized substrates and (ii) involve twofold C–C bond formation via C–H functionalization. Moreover, the annulative functionalization of simple azines has not been demonstrated yet. Given the difficulties in constructing a diverse array of tailored N-PACs, the reaction scope and yields in this work are comparable to those of previously reported APEX methods22,27.

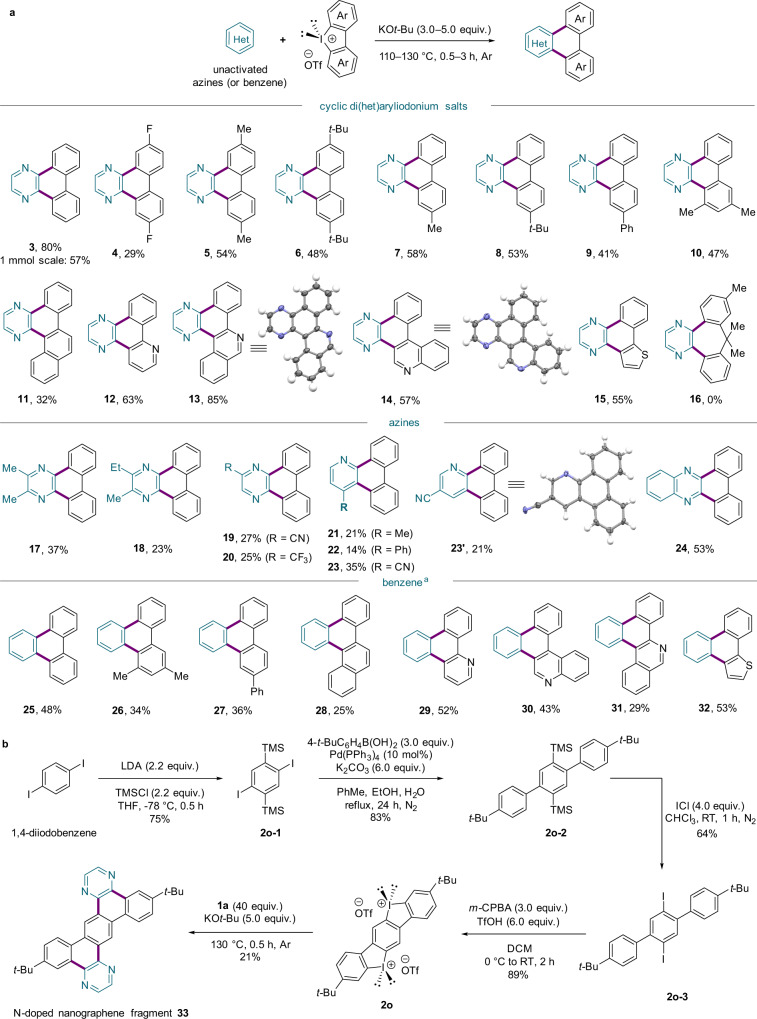

Fig. 3. Scope of transition-metal-free APEX reactions.

a Reactions were carried out on a 0.20 mmol scale for cyclic aryliodonium salt 2. aConditions for reactions with benzene: 1a (2.0 equiv., used as an additive), 2 (1.0 equiv.), KOt-Bu (5.0 equiv.) in benzene (2 mL) at 110 °C under Ar for 3 h. b Access to an N-doped nanographene fragment. Isolated yields are reported.

Access to an N-doped heptacyclic nanographene fragment

Remarkably, this protocol was readily applicable to a one-pot, fourfold arylation that yielded the N-doped heptacyclic nanographene fragment 33 in a bottom-up manner (Fig. 3b). Our synthetic route commenced with 1,4-diiodo-2,5-bis(trimethylsilyl)benzene (2o-1), which was prepared in 75% yield by treating trimethylsilyl chloride (TMSCl) and 1,4-diiodobenzene with lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) in THF at −78 °C47. Subsequent Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling with 4-tert-butylphenylboronic acid as the aryl-coupling partner was employed to afford disilylteraryl 2o-2 in 83% yield. Iodination of 2o-2 with ICl provided diiodoteraryl 2o-3, which was converted into bis(iodonium) salt 2o by meta-chloroperbenzoic acid (m-CPBA)-mediated oxidation. Finally, the desired N-doped nanographene fragment 33 could be obtained in 21% yield via our annulation protocol.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy

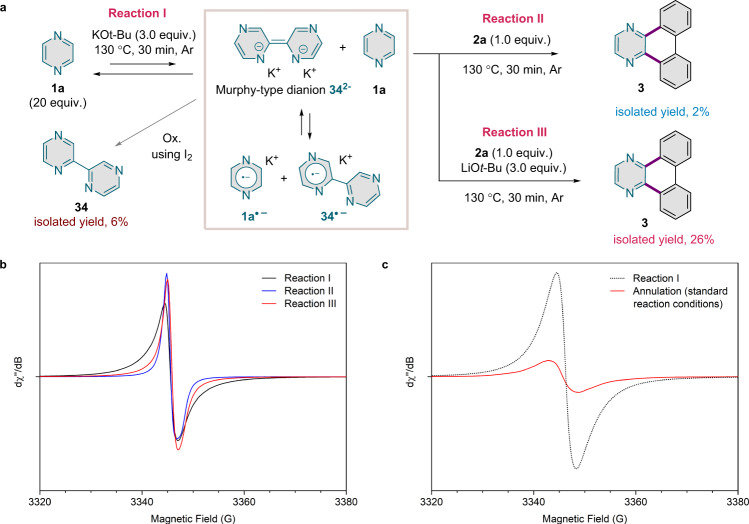

To gain insight into the reaction mechanism of the annulation of pyrazine, we first considered the reaction of 1a with KOt-Bu (Fig. 4a, reaction I; see also Supplementary Information Sections 1.9 and 1.10). The related reactions of 1,10-phenanthroline or pyridine with KOt-Bu were reported to proceed through deprotonation and coupling of the N-heterocyclic compound to afford electron-rich dianions32,48. Additionally, in the case of 1,10-phenanthroline, radical species were independently observed by the Murphy32 and the Jutand/Lei33 groups. Indeed, EPR spectra of samples from the reaction of 1a with KOt-Bu exhibit a resonance signal centred at g = 2.003 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Information Section 1.11). This signal appears to be very similar to the one reported for the corresponding reaction of 1,10-phenanthroline in toluene33, which was attributed to a mixture of the phenanthroline and diphenanthrolinyl radical anions32. Based on that precedent, we suggest that 1a first produces the dianion 342− as a strong OED and then comproportionates with the dianion to give the two corresponding radical anions (1a·−/34·−) as additional OEDs. This reaction sequence is supported by the isolation of 2,2'-bipyrazine (34) after oxidative workup using iodine (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Information Section 1.9).

Fig. 4. EPR spectroscopic studies.

a Experiments illustrating the dual role of KOt-Bu. b EPR spectra (X-band, 295 K) of samples from the reaction of 1a with KOt-Bu (reaction I; solid black line), from the two-step reaction of 1a with KOt-Bu and then with 2a (reaction II; solid blue line), and from the two-step reaction of 1a with KOt-Bu and then with 2a and LiOt-Bu (reaction III; solid red line). c EPR spectra (X-band, 295 K) of samples from the reaction of 1a with KOt-Bu (reaction I; dotted black line) and from the annulation of 1a with KOt-Bu and 2a (solid red line), with sample transfer conducted in an Ar atmosphere in both cases. The spectrum of the annulation was acquired using a microwave power one hundred times that used for the spectrum of the 1a–KOt-Bu reaction.

We then evaluated the possibility of product formation from the proposed dianion/radical anion species. Pre-activation of 1a with KOt-Bu for 30 min followed by addition of iodonium salt 2a gave product 3 only in a marginal yield (Fig. 4a, reaction II, and Supplementary Information Section 1.10). Presumably, KOt-Bu is required in the ensuing reaction but had been entirely consumed by reaction with 1a prior to the addition of 2a. By contrast, 3 was observed when LiOt-Bu was added along with 2a in the second step (reaction III), indicating that a base is required to complete the reaction. Moreover, EPR spectra of samples from these two-step experiments show a substantial decrease of the intensity of the resonance signal (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Section 1.11, Supplementary Fig. 13), demonstrating that one or both of the radical anions are directly involved in the reaction with 2a.

To elucidate the intermediacy of radical species in the annulation of 1a under standard conditions, we measured EPR spectra of samples taken from this reaction. These spectra also display a resonance signal at g = 2.003, but this signal is of much lower intensity than that of the pyrazine-derived radical anions 1a·−/34·− (Fig. 4c). It also is broader (peak-to-peak separation, 6 G vs 4 G) and less symmetric (Supplementary Fig. 14). These differences indicate that the radical anions 1a·−/34·− do not accumulate substantially, if at all, and that other radical species are present during the annulation. Furthermore, those species are, unlike 1a·−/34·−, fairly sensitive to air, as is evident from the considerably lower signal intensity and the appearance of a shoulder in spectra of samples handled in air (Supplementary Fig. 16).

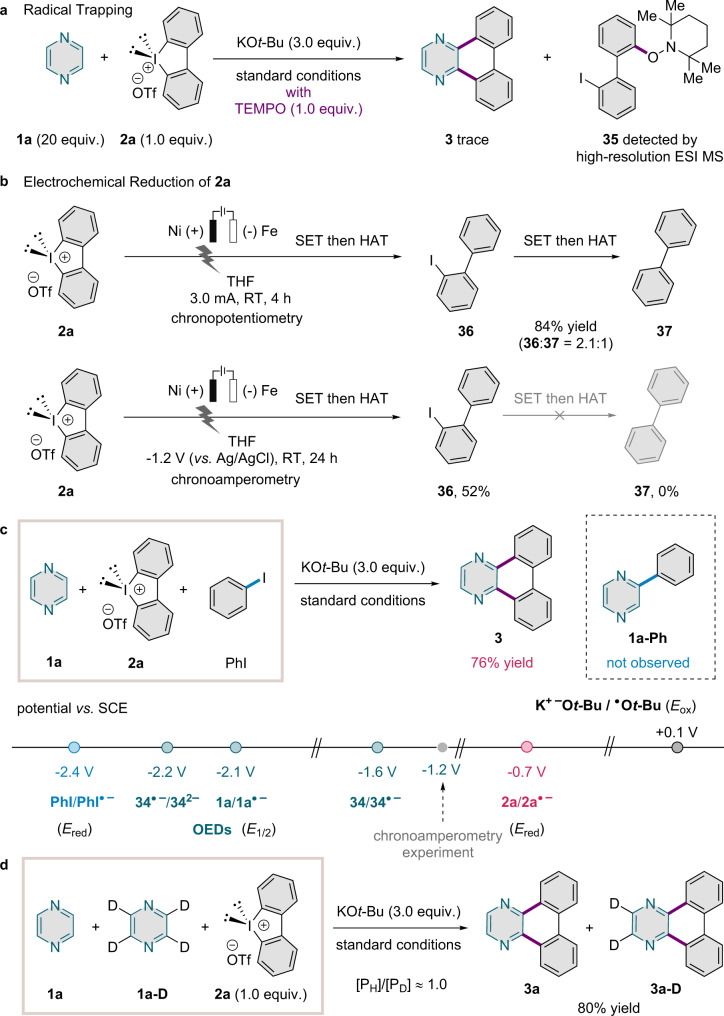

Mechanistic studies: iodanyl radical intermediacy and electron transfer

The combined reaction system of KOt-Bu and iodonium salt allowed the otherwise challenging APEX of simple azines. In this section, we provide experimental evidence of an iodanyl radical intermediate and the involvement of an electron transfer process in the reaction mechanism. Analysis of the radical trapping experiment described above by high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI MS) revealed the formation of the TEMPO adduct of an iodobiphenyl radical (35) (Fig. 5a; see also Supplementary Information Section 1.12). This radical may have been derived from 2a by one-electron reduction to give an iodanyl radical intermediate and subsequent C–I homolysis. To probe whether formation of this radical by electron transfer from a strong electron donor is feasible, we performed several electrochemical and competition experiments. The electrochemical reduction of iodonium salt 2a (Fig. 5b) under chronopotentiometric conditions (at a constant current of 3.0 mA in THF) afforded both 2-iodobiphenyl (36) and biphenyl (37). In contrast, reduction under chronoamperometric conditions (at a constant potential of −1.2 V versus Ag/AgCl in THF) afforded only 36, revealing the importance of the redox potential in the selective formation of 36. The formation of compound 36 can be explained by hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT) to an iodobiphenyl radical. The source of the H atoms is the solvent, THF, as was confirmed by an experiment with deuterated solvent, THF-d8 (see the Supplementary Information Section 1.13).

Fig. 5. Mechanistic studies.

a Radical trapping. b Electrochemical reduction of 2a. c Competition experiments and CV measurements. Potentials were converted to the SCE scale using ferrocene as an external standard, where necessary. d KIE experiment.

A competition experiment of the arylation with iodonium salt 2a and PhI produced only 3 and no 1a-Ph, revealing that the hypervalent iodine compound was inherently more reactive (Fig. 5c). Compound 2a also exhibits a much more favourable reduction potential (Ered2a/2a•− = −0.7 V versus SCE in DMF) than PhI (EredPhI/PhI•− = −2.4 V versus SCE in DMF)32. For comparison, the reduction potential of Ph2IBF4 in MeCN was reported as −0.58 V (versus Ag/AgCl)49. The reduction potential of 2-iodobiphenyl is −2.2 V (versus SCE in DMF), which is significantly more negative than the potential applied in the chronoamperometric experiment. Relevant redox potentials of the OEDs presumably present (i.e., 342−, 34·−, and 1a·−) were determined from cyclic voltammograms of 1a and 34. Unlike the mismatched potential (Eox) of KOt-Bu32,33, these redox potentials are located in the matched potential range of −1.6–−2.2 V toward iodonium salt 2a (Fig. 5c; see also Supplementary Information Section 1.15).

The H/D kinetic isotope effect (KIE) for this annulation reaction was also investigated, using 1a and its fully deuterated isotopologue (1a-D), to examine whether deprotonation reactions are involved in the rate-determining step (RDS) (Fig. 5d; see Supplementary Information Section 1.16.2). In a competition experiment, with the iodonium salt as the limiting reactant, a KIE value of [PH]/[PD] ≈ 1.0 was observed, indicating that the RDS was not associated with deprotonation of C–H bond by KOt-Bu. This result is in the line with the previous results from the Shirakawa/Hayashi group on the metal-free synthesis of biaryl compounds through radical chemistry39. As suggested by Murphy and Shirakawa/Hayashi for the relevant BHAS reactions of arenes, OED formation50 or one-electron reduction39 might be related to the RDS in this radical relay annulation.

Mechanistic discussion

BHAS has been applied as a transition-metal-free method to furnish biphenyl compounds39,40. The combination of alkali metal tert-butoxides, commonly KOt-Bu and NaOt-Bu, with organic additives plays a critical role in the initiation of the radical relay by converting aryl halides into aryl radicals, which have emerged as versatile synthetic intermediates in the construction of C–C bonds. In this work, we questioned whether cyclic diaryliodonium salts can act as radical precursors in annulation reactions. The working hypothesis was validated by a combined mechanistic investigation: Organic radical species attributable to OED formation were detected by EPR spectroscopy and shown to be consumed in the reaction with cyclic diphenyliodonium salt 2a, forming the annulation product 3 (Fig. 4). The involvement of radical intermediates in the annulation reaction was confirmed by a trapping experiment, which completely shut down the reaction and gave rise to the TEMPO-iodobiphenyl adduct (Fig. 2c, entry 6, and Fig. 5a). An iodobiphenyl radical intermediate was also implicated in the electrochemical reduction of 2a (Fig. 5b), and cyclic voltammetry demonstrated matched redox potentials for the reduction of cyclic diphenyliodonium salt 2a by the OEDs identified in our mechanistic and spectroscopic studies (342−, 34•−, and 1a·−; Fig. 5c).

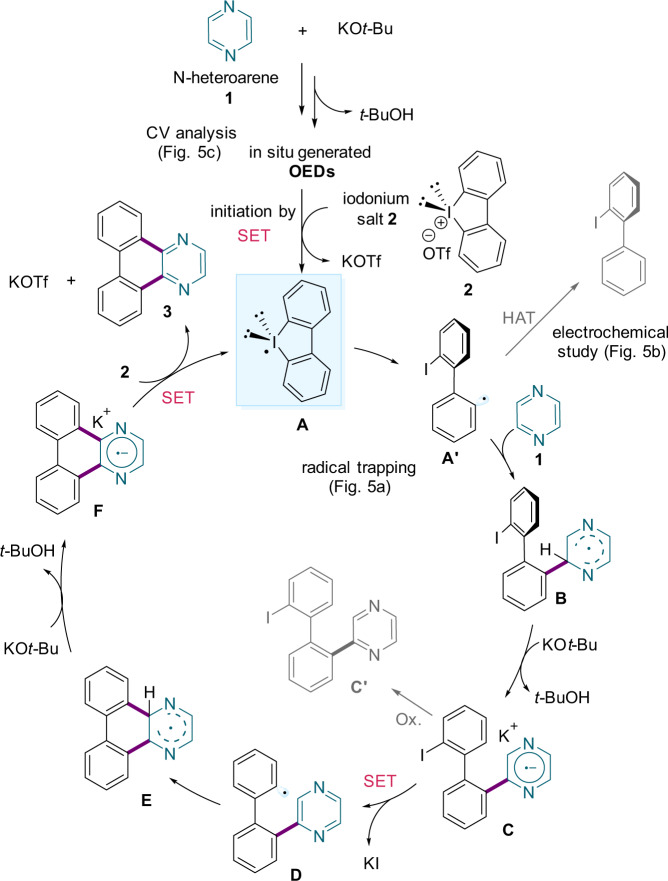

On the basis of our experimental studies and literature reports32–40,51–55, we propose that the mechanism of this annulation proceeds via a base-promoted cascade of two radical relay events (Fig. 6). The reaction pathway is initiated through the one-electron reduction of electrophilic diaryliodonium salt 2 by the OEDs, formed in situ from 1 and KOt-Bu, to generate reactive iodanyl radical A45,56. Homolysis of the C–I bond affords the carbon-centred radical A', which undergoes an iodanyl-Minisci-type addition to heteroarene 1 to afford aryl-heteroaryl radical species B. Subsequent deprotonation by KOt-Bu produces monoarylated radical anion C, whose oxidation product (C') was detected by high-resolution ESI MS (see also the Supplementary Information Section 1.17). Intramolecular SET generates carbon-centred radical D upon release of KI, which is followed by radical addition and deprotonation of intermediate E by KOt-Bu to provide radical anion F. Finally, SET from F to iodonium salt 2 regenerates iodanyl radical A, while furnishing the desired annulation product 3. A table summarizing the mechanistic and spectroscopic studies is also shown in the Supplementary Information (Section 1.19).

Fig. 6. Proposed iodanyl-Minisci-type APEX reaction mechanism of simple azines.

This radical relay-based annulation approach allows the formation of polycyclic N-heteroarenes.

We have demonstrated a Minisci-type annulation of simple azines to rapidly access polycyclic N-heteroarenes. Mechanistic and spectroscopic studies provide experimental evidence of one-electron reduction of a cyclic iodonium salt by in situ generated organic electron donors affording an iodanyl radical, which may trigger a radical relay cascade to complete the annulative aryl-appending process. The synthetic utility of this iodanyl-Minisci-type reaction is highlighted by the preparation of an N-doped heptacyclic nanographene fragment. We anticipate that our transition-metal-free, radical-based protocol and mechanistic studies can contribute to the straightforward construction of complex polycyclic heteroaromatic compounds.

Methods

General procedure for APEX of azines with cyclic iodonium salts

In an Ar-filled glove box, a screw-cap 1-dram vial was charged with cyclic diaryliodonium salt 2 (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), KOt-Bu (0.60 mmol, 3.0 equiv.) and azine 1 (4.0 mmol, 20 equiv.). After the reaction mixture was stirred at 130 °C for 30 min, it was allowed to cool to RT and diluted with DCM (2 mL). After the sample was sonicated for 1 h at RT, it was directly purified by column chromatography to afford the desired APEX product. See Supplementary Information for experimental details and the characterisation of each compound.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for financial supports provided by Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) grant funded by the Korean government (21ZB1200, development of ICT materials, components and equipment technologies) and UNIST research fund (1.190118.01). J.B.L. is grateful for the support from National Research Foundation of Korea grant (NRF-2020R1A5A1019631) funded by the Korean government (MSIT).

Author contributions

J.B.L., J.-U.R. and S.Y.H. conceived the project. J.B.L., J.H.J. S.Y.J. and J.-H.C. prepared substrates, and examined the annulation reactions. S.L. and W.C. solved single crystal X-ray structures. G.H.K., J.P., D.L., Y.K., J.K.S. and S.J.K. worked on analytical sections for the mechanistic experiments. J.B.L., J.-U.R. and S.Y.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed results and provided input on the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files. The crystallographic data generated in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers 2047992 (13), 2047991 (14), and 2116428 (23'). These crystallographic data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jan-Uwe Rohde, Email: rohde@unist.ac.kr.

Sung You Hong, Email: syhong@unist.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-30086-0.

References

- 1.Hammer BAG, Müllen K. Dimensional evolution of polyphenylenes: expanding in all directions. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:2103–2140. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segawa Y, Maekawa T, Itami K. Synthesis of extended π-systems through C–H activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:66–81. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaujuge PM, Fréchet JMJ. Molecular design and ordering effects in π-functional materials for transistor and solar cell applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20009–20029. doi: 10.1021/ja2073643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shea JJ, Luo C. Organic electrode materials for metal ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:5361–5380. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morita Y, et al. Organic tailored batteries materials using stable open-shell molecules with degenerate frontier orbitals. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:947–951. doi: 10.1038/nmat3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimsdale AC, Müllen K. The chemistry of organic nanomaterials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5592–5629. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segawa Y, Ito H, Itami K. Structurally uniform and atomically precise carbon nanostructures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;1:15002. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2015.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segawa Y, Yagi A, Matsui K, Itami K. Design and synthesis of carbon nanotube segments. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:5136–5158. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narita A, Wang X-Y, Feng X, Müllen K. New advances in nanographene chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:6616–6643. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00183H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, et al. Pd(II)-catalyzed regioselective multiple C–H arylations of 1-naphthamides with cyclic diaryliodonium salts: one-step access to [4]- and [5]carbohelicenes. Org. Lett. 2020;22:135–139. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b04046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagui W, Doucet H, Soule J-F. Application of palladium-catalyzed C(sp2)–H bond arylation to the synthesis of polycyclic (hetero)aromatics. Chem. 2019;5:2006–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye Z, Li Y, Xu K, Chen N, Zhang F. Cascade π-extended decarboxylative annulation involving cyclic diaryliodonium salts: site-selective synthesis of phenanthridines and benzocarbazoles via a traceless directing group strategy. Org. Lett. 2019;21:9869–9873. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu T, et al. Two-in-one strategy for the Pd(II)-catalyzed tandem C–H arylation/decarboxylative annulation involved with cyclic diaryliodonium salts. Org. Lett. 2019;21:7233–7237. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu C, et al. Bottom-up construction of π-extended arenes by a palladium-catalyzed annulative dimerization of o-iodobiaryl compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:8848–8853. doi: 10.1002/anie.201803603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang S, et al. Site-selective synthesis of functionalized dibenzo[f,h]quinolines and their derivatives involving cyclic diaryliodonium salts via a decarboxylative annulation strategy. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:3239–3242. doi: 10.1039/C8CC00300A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S, Wang F, Wu Y, Hua W, Zhang F. Synthesis of functionalized triphenylenes via a traceless directing group strategy. Org. Lett. 2018;20:1491–1495. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Y, et al. Palladium catalyzed dual C–H functionalization of indoles with cyclic diaryliodoniums, an approach to ring fused carbazole derivatives. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:9777–9780. doi: 10.1039/C4OB02170C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen T-A, Liu R-S. Synthesis of large polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from bis(biaryl)acetylenes: large planar PAHs with low π-sextets. Org. Lett. 2011;13:4644–4647. doi: 10.1021/ol201854g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King BT, et al. Controlling the Scholl reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:2279–2288. doi: 10.1021/jo061515x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito H, Segawa Y, Kurakami K, Itami K. Polycyclic arene synthesis by annulative π-extension. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:3–10. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b09232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathew BP, et al. An annulative synthetic strategy for building triphenylene frameworks by multiple C–H bond activations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:5007–5011. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JB, et al. Annulative π-extension of unactivated benzene derivatives through nondirected C–H arylation. Org. Lett. 2019;21:7004–7008. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozaki K, Kawasumi K, Shibata M, Ito H, Itami K. One-shot K-region selective annulative π-extension for nanographene synthesis and functionalization. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6251. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirai M, Tanaka N, Sakai M, Yamaguchi S. Structurally constrained boron-, nitrogen-, silicon-, and phosphorus-centered polycyclic π-conjugated systems. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:8291–8331. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong W-J, Shen Z, Finger LH, Ackermann L. Electrochemical access to aza-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: rhoda-electrocatalyzed domino alkyne annulations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:5551–5556. doi: 10.1002/anie.201914775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng Z, et al. Gold-catalyzed regiospecific C–H annulation of o-ethynylbiaryls with anthranils: π-extension by ring-expansion en route to N-doped PAHs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:6935–6939. doi: 10.1002/anie.201802445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawahara KP, Matsuoka W, Ito H, Itami K. Synthesis of nitrogen-containing polyaromatics by aza-annulative π-extension of unfunctionalized aromatics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:6383–6388. doi: 10.1002/anie.201913394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami K, Yamada S, Kaneda T, Itami K. C–H functionalization of azines. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:9302–9332. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proctor RSJ, Phipps RJ. Recent advances in Minisci-type reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:13666–13699. doi: 10.1002/anie.201900977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seiple IB, et al. Direct C–H arylation of electron-deficient heterocycles with arylboronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13194–13196. doi: 10.1021/ja1066459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dohi T, et al. Selective aryl radical transfers into N-heteroaromatics from diaryliodonoium salts with trimethoxybenzene auxiliary. Heterocycles. 2017;95:1272–1284. doi: 10.3987/COM-16-S(S)90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barham JP, et al. KOtBu: a privileged reagent for electron transfer reactions? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:7402–7410. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi H, Jutand A, Lei A. Evidence for the interaction between tBuOK and 1,10-phenanthroline to form the 1,10-phenthroline radical anion: a key step for the activation of aryl bromides by electron transfer. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:545–548. doi: 10.1039/C4CC07299E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao S, et al. Base promoted direct C4-arylation of 4-substituted-pyrazolin-5-ones with diaryliodonium salts. RSC Adv. 2015;5:36390–36393. doi: 10.1039/C5RA03819G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobisu M, Furukawa T, Chatani N. Visible light-mediated direct arylation of arenes and heteroarenes using diaryliodonium salts in the presence and absence of a photocatalyst. Chem. Lett. 2013;42:1203–1205. doi: 10.1246/cl.130547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen J, Zhang R-Y, Chen S-Y, Zhang J, Yu X-Q. Direct arylation of arene and N-heteroarenes with diaryliodonium salts without the use of transition metal catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:766–771. doi: 10.1021/jo202150t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu W, et al. Organocatalysis in cross-coupling: DMEDA-catalyzed direct C–H arylation of unactivated benzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16737–16740. doi: 10.1021/ja103050x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun C-L, et al. An efficient organocatalytic method for constructing biaryls through aromatic C–H activation. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:1044–1049. doi: 10.1038/nchem.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shirakawa E, Itoh K-i, Higashino T, Hayashi T. tert-Butoxide-mediated arylation of benzene with aryl halides in the presence of a catalytic 1,10-phenanthroline derivative. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15537–15539. doi: 10.1021/ja1080822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanagisawa S, Ueda K, Taniguchi T, Itami K. Potassium t-butoxide alone can promote the biaryl coupling of electron-deficient nitrogen heterocycles and haloarenes. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4673–4676. doi: 10.1021/ol8019764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merritt EA, Olofsson B. Diaryliodonium salts: a journey from obscurity to fame. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9052–9070. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshimura A, Zhdankin VV. Advances in synthetic applications of hypervalent iodine compounds. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:3328–3435. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhdankin VV, Stang PJ. Chemistry of polyvalent iodine. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:5299–5358. doi: 10.1021/cr800332c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wirth T. Hypervalent iodine chemistry in synthesis: scope and new directions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3656–3665. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Studer A. Iodine(III) reagents in radical chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:1712–1724. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuoka W, Ito H, Sarlar D, Itami K. Diversity-oriented synthesis of nanographenes enabled by dearomative annulative π-extension. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3940. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24261-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lulinski S, Serwatowski J. Bromine as the ortho-directing group in the aromatic metalation/silylation of substituted bromobenzenes. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:9384–9388. doi: 10.1021/jo034790h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Studer A, Curran DP. Catalysis of radical reactions: a radical chemistry perspective. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:58–102. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magdesieva TV, Kravchuk DN, Butin KP. Electrochemical arylation of cobalt and nickel chelates with diphenyliodonium salts. Russ. Chem. Bull. Int. Ed. 2002;51:85–89. doi: 10.1023/A:1015009729780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou S, et al. Organic super electron-donors: initiators in transition metal-free haloarene-arene coupling. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:476–482. doi: 10.1039/C3SC52315B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nocera G, Murphy JA. Ground state cross-coupling of haloarenes with arenes initiated by organic electron donors, formed in situ: an overview. Synthesis. 2020;52:327–336. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1690614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang L, Yang H, Jiao L. Revisiting the radical initiation mechanism of the diamine-promoted transition-metal-free cross-coupling reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:7151–7160. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Studer A, Curran DP. The electron is a catalyst. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:765–773. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barham JP, et al. Double deprotonation of pyridinols generates potent organic electron-donor initiators for haloarene–arene coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:4492–4496. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Broggi J, Terme T, Vanelle P. Organic electron donors as powerful single-electron reducing agents in organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:384–413. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X, Studer A. Regio- and stereoselective cyanotriflation of alkynes using aryl(cyano)iodonium triflates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2977–2980. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files. The crystallographic data generated in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers 2047992 (13), 2047991 (14), and 2116428 (23'). These crystallographic data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.