Abstract

Purpose: Hospital pharmacists contribute to patient safety and quality initiatives by overseeing the prescribing of antidiabetic medications. A pharmacist-driven glycemic control protocol was developed to reduce the rate of severe hypoglycemia events (SHE) in high-risk hospitalized patients. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed the rates of SHE (defined as blood glucose ≤40 mg/dL), before and after instituting a pharmacist-driven glycemic control protocol over a 4-year period. A hospital glucose management team that included a lead Certified Diabetes Educator Pharmacist (CDEP), 5 pharmacists trained in diabetes, a lead hospitalist, critical care and hospital providers established a process to first identify patients at risk for severe hypoglycemia and then implement our protocol. Criteria from the American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists was utilized to identify and treat patients at risk for SHE. We analyzed and compared the rate of SHE and physician acceptance rates before and after protocol initiation. Results: From January 2015 to March 2019, 18 297 patients met criteria for this study; 139 patients experienced a SHE and approximately 80% were considered high risk diabetes patients. Physician acceptance rates for the new protocol ranged from 77% to 81% from the year of initiation (2016) through 2018. The absolute risk reduction of SHE was 9 events per 1000 hospitalized diabetic patients and the relative risk reduction was 74% SHE from the start to the end of the protocol implementation. Linear regression analysis demonstrated that SHE decreased by 1.5 events per 1000 hospitalized diabetic patients (95% confidence interval, −1.54 to −1.48, P < .001) during the 2 years following the introduction of the protocol. This represents a 15% relative reduction of SHE per year. Conclusion: The pharmacist-driven glycemic control protocol was well accepted by our hospitalists and led to a significant reduction in SHE in high-risk diabetes patient groups at our hospital. It was cost effective and strengthened our physician-pharmacist relationship while improving diabetes care.

Keywords: severe hypoglycemia, steroid induced hyperglycemia, glycemic control, pharmacist driven protocol, insulin pumps

Key Points

Pharmacist-Driven Glycemic Control Protocols can lead to reduction in severe hypoglycemia events in high risk diabetes patient groups.

The close collaboration and communication between lead Certified Diabetes Educator pharmacist and physician were instrumental in the implementation and continued success of the Pharmacist-Driven Glycemic Protocol.

Empowerment of the lead Pharmacist to develop and redesign the Glycemic Control Protocol can result in improved quality of diabetes care in hospitals nationwide.

Introduction

Over 30 million people in the United States have diabetes accounting for over 7 million hospital admissions in 2014.1,2 Diabetes care totaled 327 billion dollars in 2017 representing approximately 10% of total US healthcare costs. 3 Uncontrolled inpatient hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia are associated with increased morbidity, mortality, hospital length of stay, hospital costs, and resource utilization.4,5 Nationally, severe hypoglycemia events (SHE) increase the rates of organ injury, seizures, falls, coma, and death, resulting in an increase in hospital costs of approximately 1.6 billion dollars annually.5,6 Improving diabetes control in hospitalized patients will decrease the burden and healthcare costs associated with diabetes.

Quality improvement initiatives are an integral part of modern healthcare systems; and many hospitals have instituted a multidisciplinary approach to improve glycemic control. Pharmacist-supervised care programs have supported the participation of pharmacists to improve the care of patients with diabetes. 7 Identifying high-risk groups such as patients with impaired renal function, rapidly fluctuating blood glucose levels, inconsistent caloric intake along with focused patient management protocols can help mitigate the risk for SHE. 7 There is limited information in the literature on strategies to optimize glycemic control and to identify patients who are at high-risk for SHE. Additionally, there is a lack of data evaluating the benefit of effective pharmacist-provider communication strategies and its subsequent impact on the management of SHE in high risk patient groups.

In this study, a certified diabetes educator pharmacist (CDEP) worked with a lead hospitalist to develop a Pharmacist-Driven Glycemic Control Protocol (RxGCP). We hypothesized that this protocol would reduce the number of SHE among high-risk patients at our community-based hospital.

Methods

A CDEP at our hospital organized and led an interdisciplinary team composed of the CDEP, five pharmacists trained in glucose management, a lead hospitalist, critical care and hospital providers. The CDEP had a comprehensive knowledge base of glucose management and education and held a certification from the National Certification Board for Diabetes Education in the United States.

The Pharmacist-driven protocol, developed by the CDEP and lead hospitalist, consisted of two steps:

Screening Process

During the first step of the protocol, the glucose trained Pharmacist or the CDEP screened all patients daily and used the criteria listed below to identify patients for further workup:

- Inpatients who had a glycosylated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) > 8%, which correlates with a blood glucose level of 183 mg/dL, or a blood glucose < 70 mg/dL or > 180 mg/dL. We did not include random or post prandial blood glucose values.

- Inpatients on continuous insulin infusions or ambulatory insulin pumps.

- Patients presenting with SHE on admission.

Intervention Process

After screening, the high-risk patients were identified by reviewing the electronic medical records (EMR) for each patient. The high-risk categories included the following elements: diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome (HHS), sepsis, chronic renal failure, steroid-induced hyperglycemia, total parenteral nutrition, enteral nutrition, ambulatory insulin pumps, history of hypoglycemia, and new-onset diabetes.8-22

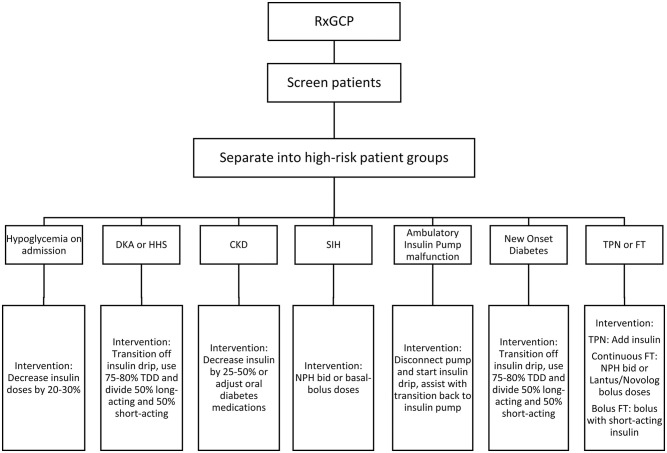

After high risk patients were identified (Figure 1), the intervention recommendations were based on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologist (AACE) standards with an overall target glucose range of 70-179 mg/dL. Postprandial blood glucose target was <180 mg/dL; pre-prandial glucose target was <140 mg/dL. The glucose target for elderly patients and those with terminal illness was <200 mg/dL23-25 (Figure 1). All diabetes regimens were individualized during the hospitalization and patients were followed on a daily basis. Patients who experienced a SHE during the hospital stay were further evaluated by the hospital quality improvement team and changes were made to the protocol if warranted.

Figure 1.

Flowsheet of pharmacist-driven glycemic control protocol.

Note. DKA = diabetic ketoacidosis, HHS = hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome, CKD = chronic kidney disease, SIH = steroid induced hyperglycemia, FT = feeding tube, TPN = total parenteral nutrition.

Pharmacist recommendations included the following: prospective development of an insulin regimen for patients with new onset diabetes; conversion from continuous insulin infusion to short-acting and long-acting insulin; and insulin dosage adjustments based on nutritional status, steroid administration, and concomitant oral diabetic medications. Inpatient insulin regimens were adjusted daily when additional risk factors arose, such as impaired renal function, hepatic failure or new-onset sepsis. The majority of Pharmacists’ recommendations were transmitted via written communication which was the preferred method. In some situations, we paged the hospitalists when changes to a diabetes regimen could not wait until the end of the shift due to the potential for a hypoglycemia event. The physician hospitalists and critical care providers either accepted, modified, or rejected the clinical pharmacists’ recommendations on a patient-by-patient basis. All charts with glucose recommendations were reviewed daily; the acceptance, the modification, or the rejection of the recommendations were entered a data collection spreadsheet. The most commonly rejected recommendations were changes to long acting insulin in the setting of steroid induced hyperglycemia. These rejected recommendations often correlated with a change in the steroid dose by the hospitalist. Another commonly rejected recommendation was to reinitiate prehospital oral antihyperglycemic agents; hospitalists often preferred to reinitiate these medications at the time of discharge from the hospital.

We incorporated several established protocols, utilized information from the ADA/AACE standards, and incorporated an iterative process to individualize diabetes regimens in these high-risk patients.19,21-24,26,27 The CDEP assisted with protocol development and redesign, augmented physician-pharmacist communication, optimized order sets and continuous insulin infusion algorithms. The team quantified all recommendations, analyzed physician acceptance rates and analyzed the impact of the interventions on SHE.

A retrospective analysis of patients who had SHE from 2015 to 2019 was done at our 150-bed community hospital. Institutional ethical approval was obtained prior to the implementation of our protocol (IRB ID 00004669).

Data Analysis

Our primary endpoint was a change in the rate of SHE after protocol initiation. The rate of SHE was calculated as follows:

Our secondary outcome was the acceptance rates of pharmacist recommendations by hospitalists. We calculated rates for SHE’s from 2015 to 2018, which included rates prior to protocol initiation, that is, 2015 and 2016, and rates after protocol initiation, that is, 2017 to 2018. Linear regression models were created to estimate the temporal change in the rates of SHEs. The year term was modeled as a continuous variable, and an offset for the log number of SHEs per year was used to adjust for yearly variation in hospital admissions. A two-sided P-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (V.25, Armonk, NY).

Results

From January 2015 to March 2019, 18 297 patients received at least 1 antihyperglycemic medication. The most common causes of either severe hypoglycemic or hyperglycemic events in order of frequency were (1) nutrition-insulin mismatch, (2) steroid-induced hyperglycemia, (3) insulin pump re-programming, (4) acute changes to renal or hepatic function, and (5) suboptimal patient insulin injection technique.

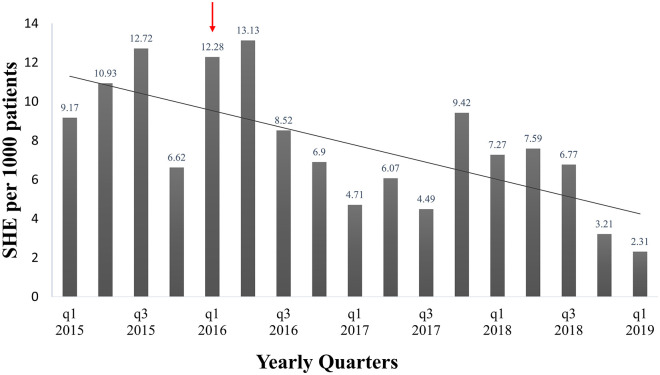

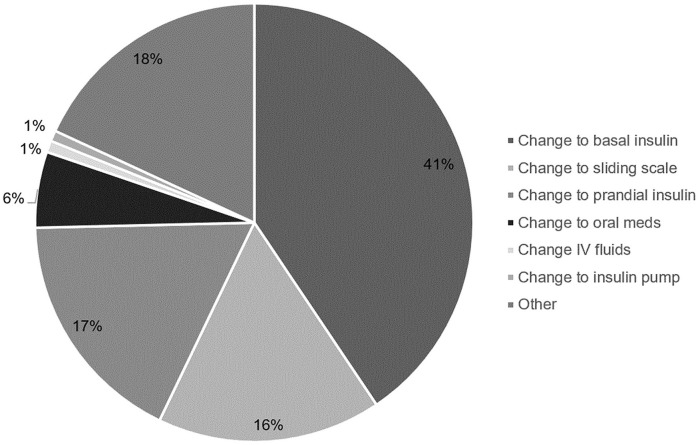

The data demonstrated a significant reduction in the frequency of SHE after the implementation of the RxGCP (Figure 2). We used 12.28 SHE per 1000 patients in quarter 1, 2016 and 3.21 SHE per 1000 patients in quarter 4, 2018 to calculate the absolute and relative risk reduction. The absolute risk reduction of SHE was 9 events per 1000 hospitalized diabetic patients. When extrapolated to include quarter 1, 2019, the absolute risk reduction was 10 SHE per 1000 patients. The relative risk reduction in the rate of SHE was 74% from the initiation to the completion of the protocol implementation. When extrapolated to include quarter 1, 2019, the relative risk reduction in the rate of SHE was 81%. The linear regression analysis demonstrated that SHE reduced by 1.5 events per 1000 hospitalized diabetic patients each year. The acceptance rates from pharmacist recommendations remained stable, varying from 77% in 2016 to 78% in 2018. The most common recommendations were changes to the basal insulin, short-acting insulin, and sliding-scale insulin regimens (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Rates of severe hypoglycemic events per 1000 patients who received at least 1 antihyperglycemic medication.

Note. Arrow represents protocol initiation, January 2016.

Figure 3.

Pharmacist Recommendations for the period 2016-2018 showing the types of diabetes regimen changes. The most common changes were to basal and prandial insulin doses and to the selection of the insulin correction scale (low, medium, or high).

Discussion

In our study, the implementation of our Pharmacist-driven Glycemic Control Protocol resulted in a significant and sustained reduction in SHE in several high-risk patient groups. The protocol was originally developed because a review of glycemic control at our hospital revealed frequent hypoglycemia events. The hospital quality management team requested the assistance from the pharmacists to manage glycemic control to reduce the frequency of SHE. The hospital did not have an endocrinologist team as do other hospitals within our health care system. However, our hospital had a CDEP on staff who collaborated with the physician team to develop a protocol to optimize the glycemic control of patients in the hospital. The CDEP and the interdisciplinary leadership team reviewed several nationally published protocols which yielded positive clinical patient outcomes from pharmacist-physician management protocols for several chronic diseases.28,29

Our protocol focused on moderate to severe hypoglycemia after analysis of the reported SHE and identification of the commonalities associated with hypoglycemia events. Several published protocols were reviewed to develop the screening process to identify high-risk patient groups needing closer monitoring of daily blood glucose.8-11,14 The number of protocol changes decreased over time. In the first 12 months of the protocol development, over 5 protocol revisions were required. In the last year of the protocol, we optimized 2 order sets to address issues associated with moderate to severe hypoglycemia: “Management of Ambulatory Insulin Pumps” and “Continuous Intravenous Insulin Infusion.”

The interdisciplinary team made adjustments to the RxGCP several times during the study to overcome barriers to glycemic control for individual patients. In the early stages of the protocol implementation, there were challenges due to limited guidelines from the ADA and AACE for some high-risk patient groups such as the specific adjustments of insulin in the setting of steroid administration or the adjustment of insulin in the setting of changes in enteral or total parenteral nutrition. The CDEP improved the order sets for the management of ambulatory insulin pumps as many of these patients experienced hypoglycemia due to changing variables like sepsis, DKA, steroid-induced hyperglycemia, worsening renal function and nutrition status. A system wide diabetes steering committee consisting of advanced practice nurses, CDE pharmacist and nurses, clinical pharmacists and dieticians was consulted on all proposed changes to diabetes order sets.

The success of our RxGCP in reducing SHE was based on the process of identifying high-risk patient groups, providing standard guidelines to writing inpatient diabetes regimens, presenting case studies to the nurses and other health care providers on causes of SHE, combined with improved physician-pharmacist collaboration. Protocol considerations for the high-risk groups:

Glycemic Control in Frail Patients

Frail patients were characterized by low body mass index (BMI), low serum albumin levels or low creatinine clearance. In this patient population, we empirically recommended a reduction in insulin doses by 20% to 30% rather than depend on clinical symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Glycemic control in patients with chronic kidney disease

The causes for hypoglycemia in patients with chronic kidney disease include decreased insulin clearance, drug interactions, albuminuria, malnutrition, infections, problems associated with dialysis, and concomitant hepatic insufficiency.10,11 We closely monitored blood glucose levels and recommended reduction of insulin doses by 25% to 50%. We also recommended the discontinuation of renally excreted oral diabetes medications and instituted insulin therapy as needed.

Glycemic control in patients with steroid-induced hyperglycemia

Steroids increase insulin resistance, increase glucose production in the liver, reduce insulin-receptor binding, and decrease insulin secretion. We designed glucose-management protocols for these high-risk patients; NPH insulin was administered for non-insulin dependent patients on concomitant steroids, and insulin glargine and insulin aspart dosages were adjusted for patients on home insulin.12,24 When appropriate, we recommended the initiation of a continuous insulin infusion with subsequent transition to basal and prandial subcutaneous insulin. During steroid dose reduction, patients were closely monitored to reduce the risk of SHE.

Glycemic control in patients on enteral or parenteral nutrition

We followed ADA/ACE guidelines for glycemic control using basal, prandial and correctional components. We collaborated with the registered dieticians and hospitalists to provide recommendations during planned or unexpected interruptions in nutrition.13-15,24

Glycemic control in patients controlled on insulin pumps

ADA guidelines support inpatient use of insulin pumps; however, patients using insulin pumps in hospital pose additional challenges. These included complex insulin regimens, the need to adjust basal and prandial insulin infusion rates due to changing variables, and patient non-compliance. We provided daily recommendations to account for changes in caloric intake, initiation of steroids, and renal impairment. 30

Glycemic control in patients on continuous insulin infusions presenting with DKA or HHS

Patients in DKA or HHS were admitted to the intensive care unit and managed using an insulin-infusion algorithm. During the transition from continuous insulin infusion to subcutaneous insulin, we recommended the use of 75% to 80% of the total daily intravenous infusion dose and divided it proportionally into basal and prandial components per ADA guidelines. 19 We developed a “clinical pearl” teaching tool to help other pharmacists with the transition from continuous insulin infusions to hospital basal-bolus regimens.

Optimization

Optimizing inpatient glycemic requires an interdisciplinary team-approach for continued success. Currently, pharmacists represent the third largest group of healthcare professionals with a diabetes educator credentialing program. 31 However, there are many other training opportunities to help hospital pharmacists expand their knowledge of diabetes care. For example, the American Pharmacists Association offers a certified training program called “The Pharmacist and Patient-Centered Diabetes Care.” Several pharmacy colleges offer certified training programs which provide hospital pharmacists with the needed knowledge to lead a pharmacist-physician diabetes management team at any institution. Allocation of additional staff to cover evenings and weekends is an additional barrier to establish and maintain pharmacist-driven diabetes management programs.

Limitation

The limitations of this study were acknowledged; this was a retrospective study from a single center. Additionally, it was challenging to account for other patient-level or hospital-level confounders such as patient comorbidities, acuity of presentation, the type and severity of diabetes, all of which may affect the effectiveness of the protocol. However, this is 1 of the few studies that incorporated a CDEP led pharmacist-physician collaborative team in the management of diabetes in an inpatient setting. The protocol was simple, cost-effective as it utilized existing pharmacist staff, and associated with a decrease SHE in the high-risk diabetes patients.

Conclusion

Following the implementation of a pharmacist-driven protocol for glycemic control, there was a significant reduction in SHE in high-risk diabetes patient groups at our hospital. We were able to use our existing pharmacy staff in the process and strengthened our physician-pharmacist relationship. As hospital pharmacists acquire enhanced clinical skills and expertise in diabetes management, improvement in diabetes management will be expected. The implementation of more pharmacist-driven glycemic control protocols across hospital systems is encouraged. Future studies might focus on developing cost-effective strategies to reduce risk of inpatient SHE using optimize protocols and pharmacist-physician collaborative teams in diabetes care.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support provided by Blake Tranby-Laudahl, PharmD and the M Health Fairview Ridges Hospital inpatient pharmacy team.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Colleen A. Cook  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3115-8017

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3115-8017

References

- 1. New CDC Report: More than 100 Million Americans have Diabetes or Prediabetes. Accessed December 18, 2019. www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p0718-diabetes-report.html

- 2. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Center for Disease Control; 2017. Accessed December 18, 2019. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- 3. Martin AB, Hartman M, Washington B, et al. National health care spending in 2017: growth slows to post-great recession rates; Share of GDP stabilizes. Health Aff. 2019;38(1):1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turchin A, Matheny ME, Shubina M, et al. Hypoglycemia and clinical options in patients with diabetes hospitalized in the general ward. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1153-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goyal RK, Sura SD, Mehta HB. Direct medical costs of hypoglycemia hospitalizations in the United States. Value Health. 2017;20:A498. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalra S, Mukherjee J, Venkataraman S, et al. Hypoglycemia: the neglected complication. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(5):819-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Upadhyay DK, Ibrahim MI, Mishra P, et al. Does pharmacist-supervised intervention through a pharmaceutical care program influence direct healthcare cost burden of newly diagnosed diabetics in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal: a non-clinical randomized controlled trial approach. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2016;24(1):1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoonyoung C, Staley B, Rene S, et al. Common inpatient hypoglycemia phenotypes identified from an automated electronic health record-based prediction model. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2019;76(3):166-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Varghese Pl, Gleason V, Sorokin R, et al. Hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients treated with antihyperglycemic agents. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):234-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alsahli M, Gerich JE. Hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes and renal disease. J Clin Med. 2015;4:948-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dendy JA, Chockalingam V, Tirumalasetty NN, et al. Identifying risk factors for severe hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:1051-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grommesh B, Lausch M, Vannelli A, et al. Hospital insulin protocol aims for glucose control in glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olvera G, Tapia MJ, Ocon J, et al. Parenteral nutrition-associated hyperglycemia in non-critically ill inpatients increases the risk of in-hospital mortality. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5): 1061-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kinnare K, Bacon CA, Chen Y, et al. Risk factors for predicting hypoglycemia in patients receiving concomitant parenteral nutrition and insulin therapy. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(2):263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Korythowski M, Salata R, Koerbel G, et al. Insulin therapy and glycemic control in hospitalized patients with diabetes during enteral nutrition therapy: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(4):594-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vriesendorp TM, van Santen S, DeVries JH, et al. Predisposing factors for hypoglycemia in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):96-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Geller AI, Shehab N, Lovergrove M, et al. National estimates of insulin-related hypoglycemia and errors leading to emergency department visits and hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:678-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mcewan P, Thorsted BL, Wolden M, et al. Healthcare resource implications of hypoglycemia-related hospital admissions and inpatient hypoglycemia: retrospective record-linked cohort studies in England. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3: e000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1119-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korythowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in a non-critical care setting: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:16-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petite SE. Non-insulin medication therapy for hospitalized patients with diabetes melitus. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2018; 75:1361-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hulkower RD, Pollack RM, Zonszein J. Understanding hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients. Diabetes Manag. 2014;4:165-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Griesdale DE, de Souza RJ, van Dam RM, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and mortality among critically ill patients: a meta-analysis including NICE-SUGAR study data. CMAJ. 2009; 180:821-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in Diabetes - 2019. Diabetes Care. 2019; 42(suppl 1):S1-187. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Folz HN, Murphy BL. Implementation of an outpatient, pharmacist-directed clinic for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exc Pharm Res J. 2016;2(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 26. NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Winterstein AG, Jeon N, Stanley B, et al. Development and validation of an automated algorithm for identifying patients at high risk for drug-induced hypoglycemia. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1714-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maiguma T, Komoto A, Shiraga E, et al. Influence of pharmacist intervention on re-evaluation of glycated hemoglobin for diabetic outpatients. Hosp Pharm. Published online October 23, 2019. doi: 10.1177/0018578719883806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wenzler E, Wang F, Goff DA, et al. An automated, pharmacist-driven initiative improves quality of care for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:194-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Umpierrez GE, Klonoff DC. Diabetes technology update: use of insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitoring in the hospital. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1579-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gonzalvo JD, Lantaff WM. CDE pharmacists in the United States. Diabetes Educ. 2018;44:278-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]