Abstract

Aim: We aimed to evaluate the impact of pharmaceutical service intervention on medication adherence and patient-reported outcomes among patients diagnosed with depression in a private psychiatric hospital in Nepal. Methods: A single-center, open trial with a parallel design was conducted among 18 to 65 years aged patients, diagnosed with depression and under antidepressant medication(s) for ≥2 months. Patients were randomised into either the intervention or control group. The control group (n = 98) received the usual care, while the intervention group (n = 98) received a pharmaceutical service intervention. The two groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, independent t-test, or chi-square test at 2 and 4 months for changes in medication adherence and patient-reported [severity of depression and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)] outcomes. Results: One hundred ninety adult patients were enrolled in the study. At baseline, there were no significant differences in any of the outcome measures between the intervention and control groups. At 2 and 4 months, the intervention group had a significant improvement only in medication adherence (P < .001) compared with the control group [MGL score: 1 (2) vs 2 (2) and 1 (1) vs 2 (1), P < .001, respectively]. Conclusion: Our study suggests that a brief pharmaceutical service intervention in the hospital setting can have a significant impact on patients’ adherence to antidepressants but does not improve their severity of depression and HRQoL.

Keywords: antidepressants, depression, health-related quality of life, interventions, medication adherence, pharmacist, severity of depression

Introduction

Depression is a common chronic psychiatric illness, affecting more than 265 million people around the globe. 1 It is associated with several specific symptoms, such as depressed mood, fatigue or loss of energy, reduced interest or pleasure in day-to-day activities, weight gain or loss, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, psychomotor retardation, and frequent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation. 2 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that by year 2020, it would be the second leading cause of worldwide disability, and by 2030, it would possibly become the most significant factor contributing to the global burden of disease. 3 In Nepal, 1 in every 3 people suffers from mental illness, and an estimated 90% of them lack access to the treatment they need. 4 A survey conducted in 2019 in three districts representing three geographical regions of Nepal estimated the prevalence of mental illness to be 13.2% among adults and 11.2% among children. 5

Medication adherence to antidepressants is directly associated with the nature and duration of therapy, severity of the disease, adverse effects of medicines, drug interactions, comorbid conditions, patient perspective about the disease and medication, and treatment cost. 6 Likewise, characteristics of the healthcare system, physician-patient interaction, and socio-cultural characteristics such as religious and cultural beliefs and stigma also hampers patients adherence to their medication. 7 Despite the proven effectiveness of antidepressant medications, patient compliance with treatment guidelines and medication adherence rate is low.8,9 Literature data shows that approximately 56% of patients prescribed antidepressants do not adhere to the therapy. 10 Non-adherence leads to treatment failure, relapse, a chronic course of depression, complications, increased healthcare costs, and impaired physical and social functioning.11,12 Hence, adherence to antidepressant treatment is an essential component for better therapeutic outcomes and enhanced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients. 13

The role of pharmacists in Nepal, unlike other developing countries, is confined to dispensing function despite having knowledge and unique skills to play a significant role in the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases, medication management, providing patient education, conducting clinical trials, and other related roles.14-16 Evidence suggests that pharmacists delivering interventions to depressed patients can have a significant positive effect on adherence, patient perceptions of depression and antidepressants, severity of depression, patient satisfaction with treatment, and hence HRQoL.17,18 Such an area has not yet been explored in the Nepalese context, especially in hospital settings. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of pharmaceutical service provided by a clinical pharmacist on medication adherence and patient-reported outcomes among patients diagnosed with depression in a private psychiatric hospital in the western part of Nepal.

Methods

Study Design

A single-center, open trial with a parallel design was conducted to assess the impact of pharmacist intervention on medication adherence and patient-reported outcomes in patients with depression who visited the outpatient department of B.G. Hospital between August 2019 and January 2020. B.G. hospital is a psychiatric hospital located at Pokhara-12, Kaski, Nepal. This study was approved by the institutional review committee (IRC) of Pokhara University Research Center (PURC) (Ref. No. 18-076-077). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to their involvement in the study, and all the information was kept confidential.

Sampling and Recruitment

Patients aged between 18 and 65 years, diagnosed with depression, taking at least one antidepressant medication for at least 2 months, and having regular visits to B.G. hospital for follow-up and/or medication refill were eligible to be included in the study. Pregnant or lactating mothers, those with a history of psychotic, bipolar disorder, or drug abuse, those with cognitive impairment, and those unable to communicate and understand the Nepali language were excluded.

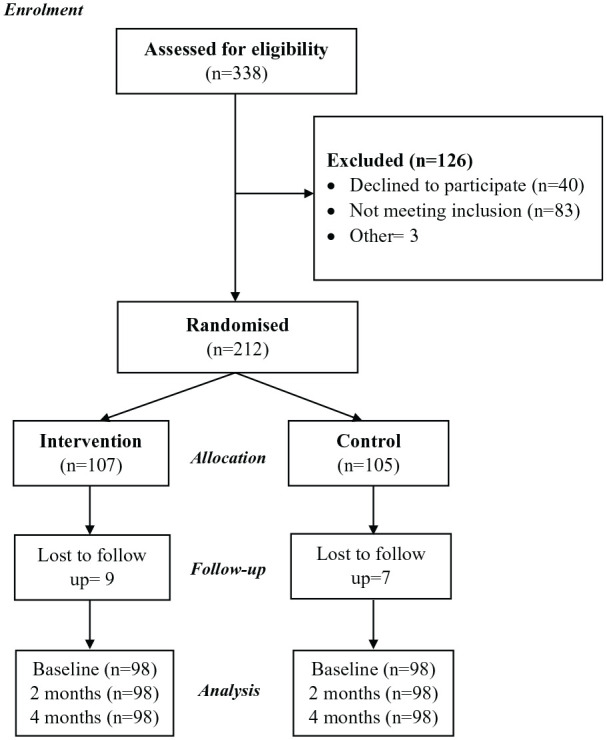

Assuming alpha risk of 0.05 and beta risk of <0.20 and allowing for a 20% dropout rate, 19 to provide 80% power, a difference in the percentage of medication intake at a confidence interval of 95% by 17 points is needed. 20 This gave us a target sample size of 195 patients to achieve adequate power. A random allocation sequence was generated using a computer to allocate participants randomly into the intervention group and the control group in a 1:1 ratio (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Recruitment and participation.

Control and Intervention

At first, the patients who gave consent for participating in the study were evaluated for their eligibility to be included in the study. Then they were randomly grouped into either the intervention group or control group. Patients assigned to the control group received usual care as provided in the hospital in regular visits including usual pharmaceutical service from a pharmacist. Patients allotted to intervention group received usual care with additional pharmaceutical services from a clinical pharmacist. A clinical pharmacist delivered the intervention and another pharmacist (blinded) performed the assessment. The intervention provided to the patients were: (i) face-to-face counselling on depression and associated risk factors for approximately 15 minutes; (ii) patients education on the use of antidepressant medications, their potential adverse effects, and essential lifestyle modifications to be practiced by the patients. Additionally, a leaflet of the session was provided to each participants after providing additional pharmaceutical services. This was followed by two consequent follow-ups in an interval of two months.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of the study was medication adherence. The secondary outcomes were the severity of depression and HRQoL. These were measured at baseline and at two follow-ups (at 2 months and 4 months). Data on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were collected at baseline, while medication adherence, severity, and HRQoL were obtained at baseline and at the two follow-ups. Their adherence to medication was evaluated using the Morisky Green Levine Scale (MGLS). The MGL scale consists of four yes/no questions and is classified as high (0 points), medium (1-2 points), and low adherence (3-4 points). 21 The severity of depression was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item depression module (PHQ-9). 22 In this study, we used the Nepali Version of the PHQ-9. 23 According to the PHQ-9 scale, patients’ status was classified as none (0-4 points), mild (5-9 points), moderate (10-14 points), moderately severe (15-19 points), and severe depression (20-27) by presenting 9 questions that have bothered patients in the last two weeks. Similarly, HRQoL was evaluated using the EQ-5D instrument developed by the EuroQoL group. 24 It consists of two parts, where self-reported problems in any one of the domains, that is, mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression were recorded as per the severity level. The severity level is classified as no problems, some problems, and extreme problems. Self-assessed health by study subjects on a visual analogue scale (VAS), a vertical 20 cm line, is recorded in the second part of the instrument. This scale scores the best and worst health states of subjects as 100 and 0, respectively. 24

Statistical Analysis

The data collected were entered into and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The normality test was performed for numeric variables using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The difference in the characteristics at baseline and the outcome measures at the first and second follow-ups between the intervention and control groups were determined using the Mann-Whitney U test, independent t-test and Chi-square test where appropriate. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 338 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 196 patients were included in this study to randomise an equal number of participants in the intervention and control groups (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population, stratified by the type of intervention. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in demographic and clinical parameters, including age, gender, medication adherence, the severity of depression (PHQ-9), and HRQoL.

Table 1.

Baseline Demography, Medication Adherence, Severity (PHQ-9), and HRQoL (n = 196).

| Characteristics | Enrolment | Control (n = 98) | Intervention (n = 98) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% female) | 74 (75.51) | 68 (69.38) | .177 | |

| Age in years | 18-30 | 30 (30.61) | 27 (7.1) | |

| 31-40 | 28 (28.57) | 30 (30.61) | .459 | |

| 41-50 | 25 (25.51) | 22 (22.44) | ||

| 50-65 | 15 (15.30) | 19 (19.38) | ||

| Education | Illiterate | 26 (26.53) | 25 (25.51) | .247 |

| Primary | 33 (33.67) | 32 (32.65) | ||

| High school and above | 39 (39.79) | 41 (41.83) | ||

| Employed (Yes) | 55 (56.12) | 60 (61.22) | .184 | |

| Number of antidepressants prescribed | One | 72 | 85 | .432 |

| Two | 22 | 13 | ||

| a MGL score [median(IQR)] | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | .812 | |

| Medication adherence | Low | 13 (54.2) | 11 (45.8) | .075 |

| Medium | 12 (41.4) | 17 (58.6) | ||

| High | 3 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| PHQ-9 score—[mean ± SD] | 18.90 ± 10.27 | 17.44 ± 9.89 | .408 | |

| b HRQoL score EQ-5D—[mean ± SD] | 0.62 ± 0.36 | 0.64 ± 0.38 | .648 | |

Note. All the values in the control and intervention columns are n (%). All P-values were computed using the Chi-square test unless otherwise stated. HRQoL = health-related quality of life; MGL = Morisky Green Levine medication adherence scale; PHQ-9 = patient health questionnaire-9.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Independent t-test. Higher MGL scores indicate low adherence, while higher HRQoL scores suggest a better quality of life.

As indicated in Table 2, in the first follow-up at 2 months, there were significant improvements in the median (IQR) MGL score (P < .001) after the pharmaceutical intervention by a clinical pharmacist. The intervention group had a lower median (IQR) MGL score than the control group [1 (2) vs 2 (2)]. In the second follow-up at 4 months, there were significant improvements in the medication adherence. MGL scores were lower in the intervention group than in the control group [MGL score: 1 (1) vs 2 (1), P < .001]. Furthermore, the severity of depression and HRQoL were not significantly changed between the control and intervention groups at the end of 2 and 4 months of follow-up.

Table 2.

Differences in the Outcome Measures between the Intervention and Control Groups (n = 56).

| Outcomes | First follow-up (2 months) |

Second follow-up (4 months) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | P-value | Control | Intervention | P-value | ||

| a MGL score | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | <.001* | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | <.001* | |

| b Medication adherence, n (%) | Low | 45 (54.2) | 42 (45.8) | .067 | 37 (100.0) | 0 | <.001* |

| Medium | 46 (41.4) | 56 (58.6) | 56 (53.1) | 59 (46.9) | |||

| High | 7 (100.0) | 0 | 5 (18.8) | 39 (81.3) | |||

| PHQ-9 score | 17.9 (9.89) | 16.8 (8.88) | .789 | 15.8 (8.74) | 13.95 (7.89) | .897 | |

| a HRQoL-score EQ-5D | 0.64 (0.38) | 0.66 (0.38) | .839 | 0.66 (0.38) | 0.68 (0.40) | .729 | |

Note. MGL = Morisky Green Levine medication adherence scale; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; PHQ-9 = patient health questionnaire-9.

Mann-Whitney U-test.

Chi-square test.

Significant Lower MGL and higher HRQoL scores suggest higher medication adherence and better quality of life, respectively.

Discussion

Our study evaluated the impact of pharmaceutical service on patient-related outcomes in patients with depression in a psychiatric hospital in the western part of Nepal. The majority of the study population was female and aged between 31 to 40 years, but there was no significant difference in the demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups. Additionally, at the start of the study, the outcome measures (medication adherence, severity, and HRQoL) remained similar between them. At the first follow-up (at 2 months) and second follow-up (at 4 months) after the intervention, medication adherence in the intervention group had a significant improvement compared with the control group. This included a statistically significant rise in medication adherence but no change in the severity and HRQoL.

The findings of the study suggested that the pharmaceutical services provided by clinical pharmacists significantly improved self-reported medication adherence to antidepressant medication in patients with depression under antidepressant medication for at least 2 months. Our study finding of improvement in medication adherence is consistent with many other studies.17-19 A systematic review reported that the antidepressant adherence level was improved by 15% to 27% with pharmacist interventions in 2012. 16 Likewise, in 2018, other systematic review and meta-analyses showed an increased adherence rate by 2.5 times in patients who received the pharmacist intervention compared to usual pharmacist care. 9 Medication adherence is the foremost component for the effective management of depression in patients, but a previous study reported poor adherence to antidepressants among Nepalese patients with depression. 13 The intervention in our study was provided by a clinical pharmacist, which could be the key point in the improvement of patient adherence toward their medication in 4 months. In the case of a similar study in the community setting, the findings could be strengthened through educational interventions by community pharmacists when patient visits for a medication refill or other healthcare services. 25

Furthermore, our study illustrated that both groups showed some improvements in depression severity at 2 and 4 months, but no significant difference was observed between the groups. Our finding was consistent with that of a previous study from Spain, where despite some improvements seen in the patients symptoms, no significant differences in depression severity was observed between the groups. 26 But, in that study, the intervention was provided by community pharmacists in primary care health centers, and follow-up was conducted at 3 and 6 months. It might be the improved adherence due to intervention that bought some improvements in the symptoms and hence the severity of depression. Since the finding was of the short study period, the significant change in the severity remained unexplored.

One of the major objectives of every interventional study is to improve the HRQoL of patients. HRQoL is greatly affected by various psychological comorbidities, among which depression is one of the most important.27,28 Our study did not find significant differences in HRQoL between the intervention and control groups. This finding is well supported by other studies from Saudi Arabia. 17 In both studies, a very specific tool, EQ-5D, was used to assess HRQoL. This tool is reported to produce insensitive information; hence, small changes might not be detected, especially when both groups have moderate scores at baseline. 17 In contrast, a hospital-based study from Brazil conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of pharmaceutical care on the quality of life of a patient with depression reported a statistically significant reduction of depressive symptoms (P < .0001) and increased quality of life (P < .0001) in 8 months of study duration. 18 Hence, long-term evaluation should be performed for better evidence of the severity and HRQoL outcomes in patients with depression. Additionally, there is a need for a detailed guideline that provides algorithms and instructions for worldwide pharmacists on how and when pharmaceutical care should be provided to patients with depressive disorders. 29

Limitations and Strength

There are some limitations to our study. This was a single-centered study conducted in the western part of Nepal and a small sample population. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings remains to be explored. The impact of the intervention observed in this study was within 6 months, which does not specifically account for the long-term effect of the intervention. Similarly, failure to do a subgroup analysis of different antidepressant drug classes limits the power of the study. Likewise, a self-reported medication adherence tool was used, which might be associated with subjective bias. Hence, other experimental methods, such as pill count and mechanical device recording, could strengthen the findings on medication adherence. However, this study is probably the first of its kind in Nepal and can be considered a starting point to elaborate similar studies in the near future.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that a brief pharmaceutical service intervention in the hospital setting can have a significant impact on patients’ adherence to antidepressants but does not improve their severity of depression and HRQoL. These findings highlight the need for further interventional studies, preferably from multicenter, prospective randomised controlled studies, to establish its long-term impact on patient-related outcomes and generalizability of the findings.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Nirmal Raj Marasine  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4353-382X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4353-382X

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Health topics: depression. Accessed August 15, 2020. https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1

- 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Accessed August 15, 2020. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

- 3. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease 2004 update. WHO. 2008. Accessed August 15, 2020. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4. HERD. Mental health in Nepal: what do evidence say? Accessed August 15, 2020. https://www.herd.org.np

- 5. Jha AK, Ojha SP, Dahal S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Nepal: findings from the pilot study. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2019;17(2):141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banerjee S, Varma RP. Factors affecting non-adherence among patients diagnosed with unipolar depression in a psychiatric department of a tertiary hospital in Kolkata, India. Depress Res Treat. Published online December 4, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/809542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marasine NR, Sankhi S. Factors associated with antidepressant medication non-adherence: a review. Turk J Pharm Sci. Published online June 1, 20120. doi: 10.4274/tjps.galenos.2020.49799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pampallona S, Bollini P, Tibaldi G, Kupelnick B, Munizza C. Patient adherence in the treatment of depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180(2):104-109. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.2.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Readdean KC, Heuer AJ, Parrott JS. Effect of pharmacist intervention on improving antidepressant medication adherence and depression symptomology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018;14(4):321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moore CM, Powell BD, Kyle JK. The role of the community pharmacist in mental health. US Pharm. 2018;43:13-20. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Effectiveness of interventions to improve antidepressant medication adherence: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(9):954-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alekhya P, Sriharsha M, Ramudu RV, et al. Adherence to antidepressant therapy: sociodemographic factor wise distribution. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;7(3):180-184. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shrestha Manandhar J, Shrestha R, Basnet N, Silwal P, Shrestha H, Risal A. Study of adherence pattern of antidepressants in patients with depression. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2017;57(1):3-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khanal S, Nissen L, Veerman L, Hollingworth S. Pharmacy workforce to prevent and manage non-communicable diseases in developing nations: the case of Nepal. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(4):655-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Erku DA, Ayele AA, Mekuria AB, Belachew SA, Hailemeskel B, Tegegn HG. The impact of pharmacist-led medication therapy management on medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomised controlled study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2017;15(3):1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al-Jumah KA, Qureshi NA. Impact of pharmacist interventions on patients’ adherence to antidepressants and patient-reported outcomes: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aljumah K, Hassali MA. Impact of pharmacist intervention on adherence and measurable patient outcomes among depressed patients: a randomised controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gomes NC, Abrao PH, Fernandes MR, Beijo LA, Magalhaes VF, Marques LA. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical care about the quality of life in patients with depression. SM J Depress Res Treat. 2015;1(1):1005. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simon GE, Goldberg D, Tiemens BG, Ustun TB. Outcomes of recognized and unrecognized depression in an international primary care study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1999;21(2):97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brook OH, van Hout H, Stalman W, et al. A pharmacy-based coaching program to improve adherence to antidepressant treatment among primary care patients. Psychiatric Serv. 2005; 56(4):487-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):509-515. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kohrt BA, Luitel NP, Acharya P, Jordans MJ. Detection of depression in low resource settings: validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and cultural concepts of distress in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0768-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. EuroQol G. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 1990;16(3):199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharma S, Bhuvan K, Alrasheedy AA, Kaundinnyayana A, Khanal A. Impact of community pharmacy-based educational intervention on patients with hypertension in Western Nepal. Australas Medical J. 2014;7(7):304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rubio-Valera M, Pujol MM, Fernandez A, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist intervention on patients initiating pharmacological treatment for depression: a randomised controlled superiority trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(9):1057-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bulloch AG, Patten SB. Non-adherence with psychotropic medications in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(1):47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Magán I, Sanz J, García-Vera MP. Psychometric properties of a Spanish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) in general population. Span J Psychol. 2008;11(2):626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamusheva M, Ignatova D, Golda A, Skowron A. The potential role of the pharmacist in supporting patients with depression—a literature-based point of view. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2020;9:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]