Abstract

Written languaging (WL) as a facilitator of second/foreign language (L2) learning has remained under-researched in the languaging literature. This study investigated the potentials of pair and self-languaging dynamics to determine (1) the attributes of quantity, focus, and conceptual processes in WL episodes and (2) translation tasks accomplishment. In a pretest–posttest research design, 60 undergraduate English-as-a-Foreign-Language (EFL) learners were selected and assigned into two groups of pair and self-languagers. For three weeks, they produced WL episodes while completing Persian-to-English translation tasks at three stages of translating, comparing to the model translation, and revising translation. Chi-square analysis indicated significant interactions between (1) languaging dynamics and the quantity of WL, and (2) languaging dynamics and the focus of WL. Accordingly, pair languagers produced more WL than self-languagers, while both groups produced fewer WL through stage-wise translation task performance. Also, while both groups focused on lexis (L-WL) more than grammar (G-WL), pair languagers produced more L-WL than self-languagers who had a higher record in producing G-WL. Moreover, the distribution of conceptual processes underlying WL episodes was uneven and more in favor of self-assessment and hypothesis formation in both groups. Finally, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated another interaction between languaging dynamics and translation task performance. Accordingly, pair languagers outperformed self-languagers on the posttest despite their mutual language learning progress. Pedagogical implications of the study promote the critical role of WL as a metacognitive mediator and translation as a form-focused task in the L2 context.

Keywords: Focus, Conceptual process, Pair/Self-dynamics, Quantity, Written languaging

Abstract

本研究探討何種鷹架動態(配對與自我)對於書面言語(WL)在數量、焦點、概念過程及EFL學習者語言學習進步歸因的影響程度. 在前後測的實驗設計中, 我們挑選了60名大學EFL學習者, 並且將他們分成配對言語組及自我言語組. 每週他們在完成3個從波斯語譯成英語的翻譯任務的同時, 要在翻譯、與範例譯文進行比較、修改譯文的這三個階段產出WL的段落. WL段落的統計分析結果顯示, 鷹架動態與WL的數量之間存在部分的交互作用, 因此, 雖然配對言語組較自我言語組產出較多的WL段落, 兩組在完成翻譯任務的過程中, 均有階段性WL段落減少的模式. 分析結果也發現鷹架動態與WL的焦點有部分交互作用, 因此, 配對言語組與自我言語組在進行翻譯任務時, 均更聚焦在詞彙 (L-WL)而非文法 (G-WL). 然而, 配對言語組較自我言語組產出更多L-WL的段落, 自我言語組則產出更多G-WL的段落. 兩組概念過程的比例均不平均, 配對言語組與自我言語組均更傾向於自我評估與假說的形成. ANOVA分析結果顯示, 配對言語組與自我言語組前後測的表現均有進步, 但配對言語組後測分數的進步超過了自我言語組. 本文最後對L2教師與SLA研究者提出一些教學上的啟示.

關鍵詞: 配對言語, 鷹架, 自我言語, 翻譯, 書面言語

Introduction

Soon after Swain (2005) introduced the concept of languaging, a growing number of studies in second language acquisition (SLA) research were conducted on the mediation role of languaging in complex cognitive tasks performance (Negueruela, 2003, 2008; Qi & Lapkin, 2001; Swain, 2005; Swain et al., 2009). By definition, languaging is a metacognitive output or an “action—a dynamic, never-ending process of using language to make meaning” ((Swain, 2005), p. 96).

Within Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of mind (SCT), empirical findings have supported Swain’s claim that languaging is a semiotic and metacognitive tool that can largely contribute to second/foreign language (L2) learning (Pourdana et al., 2021; Tocalli-Beller & Swain, 2005, 2007). In other words, L2 learners “externalize their thoughts and then, these externalized thoughts transform into artifacts that allow other learners to contemplate” when they produce languaging with the self (i.e., self-languaging) or with others (i.e., pair/peer languaging) (Swain, 2005, p. 478). Therefore, by producing languaging episodes, L2 learners seem capable of regulating their thoughts and showing better performance on challenging tasks (Behbahani et al., 2011; Swain, 2006; Swain & Lapkin, 1998; Swain et al., 2009).

In the languaging research literature, a greater interest has been shown in oral languaging than languaging in written mode (DiCamilla & Lantolf, 1994; Suzuki, 2012; Swain, 2005). Suzuki (2009, p. 4) introduced the concept of written languaging (hereafter, WL) as an “equivalent of private speech, but in writing” and promoted three important advantages of WL, in terms of (a) offering more time to focus on the language form, (b) releasing extra cognitive load and allowing deeper language processing, and (c) offering the external memory space accessible in the future. Suzuki (2009, p. 4) even argued that WL “might stimulate even more elucidation and clarification of thoughts than oral languaging.” Accordingly, the L2 learners’ thoughts and ideas are more effectively shaped into written artifacts through WL for further deliberation (Ishikawa, 2013, 2015). However, WL has mostly been utilized as a medium of data collection in research (Hanaoka, 2007; Heidari et al., 2019; Izumi, 2002), rather than as an important mediator of L2 learning in the real classroom (Suzuki, 2009, 2012).

In a series of experiments, Swain and Suzuki, (2008) redefined languaging as a self-scaffolding platform that L2 learners can efficiently use to complete problem-solving tasks. In other words, L2 learners do languaging to internalize their private speech and gradually transfer this internalized cognition to learn complex linguistic structures (Knouzi et al., 2010). In parallel, peer/pair languaging is assumed as a zone of collective scaffolding through social interactions, when L2 learners share ideas and shape their own and others’ cognition (Donato et al., 1994; Pourdana et al., 2014; Swain, 2006). But the key question is whether the pair and self-languaging dynamics would generate different impacts on L2 learning development which is the concern of the current study.

Literature Review

Languaging in SLA Research

Grounded in the Vygotskyan SCT framework, languaging is a semiotic tool that L2 learners use to regulate their minds while performing challenging tasks (Vygotsky, 1987). Swain (2005, p. 106) maintained that languaging is the verbalized mediation of the mind with “the cognition and recognition of experience and knowledge” to facilitate target language learning. Swain argued that L2 learners produce double outputs—the primary L2 output and the secondary languaging output—when they are languaging about language. Such concurrence in various classroom tasks would likely enhance the noticing and metacognitive functions of the L2 learners in learning complex language structures.

Languaging can take place either through a collaborative dialogue with others or an egocentric dialogue with the self. Swain and Lapkin (2002) corresponded pair/peer languaging to Donato (1994, p. 102) collaborative dialogue and redefined it as the “dialogue in which speakers are engaged in problem-solving and knowledge building.” A few years later, Negueruela and Lantolf (2006, p. 86) paralleled self-languaging with private speech and modified it as “the intentional use of overt self-directed speech to explain concepts to the self.” Both pair and self-dynamics of languaging were supported as effective scaffolding mediations in several SLA studies (de la Colina & García Mayo, 2007; Knouzi et al., 2010; Suzuki, 2009; Swain & Lapkin, 1998; Vygotsky, 1987).

Recent SLA literature has narrowed its scope to the interplay between languaging and L2 learner proficiency (Pourdana et al., 2021) and the focus of languaging episodes (Suzuki, 2012) with minimal interest in the pair/self-dynamics of languaging (Yang, 2016). For instance, in a case study of two Mandarin English-as-a-second language (ESL) learners, Qi and Lapkin (2001) investigated how self-languaging affected composing and reformulation in writing tasks by a higher-proficiency and a lower-proficiency languagers. They reported that self-languaging benefited the noticing process in both languagers. Yet, the lower-level languager paid more attention to lexis than grammar in contrast to the higher-level languager. In another experiment with 141 Japanese EFL learners, Suzuki and Itagaki (2009) investigated the potential interactions among types of focus in WL episodes (i.e., grammar-based vs. lexis-based), types of grammar exercises (i.e., comprehension-based vs. production-oriented), and L2 learners’ higher and lower levels of proficiency. Their analysis of WL episodes indicated that the total number of grammar-based WL was much more than lexis-based WL in both comprehension-based and production-based translation tasks. Further analysis also supported that higher-level languagers produced more grammar-based WL than lower-level languagers. Therefore, they argued that producing languaging could make a considerable impact on the amount of L2 learners’ language production in general. Besides their remarkable findings, Suzuki and Itagaki (2009) promoted the pedagogical implications of translation as a discrete, form-focused writing task that can play a critical role in EFL classroom contexts.

From a different perspective, Zeng and Takatsuka (2009) focused on the pair languaging dynamic by collecting text-based WL episodes from 16 Chinese EFL learners’ who collaborated on online writing tasks in the Moodle™ course management system. The online chat logs were analyzed for the quantity, focus, and resolution of WL episodes. The researchers concluded that peer languaging could draw the L2 learners’ attention to grammatical forms and subsequently improve their language learning. The L2 learners’ responses to a post-task survey supported the researchers’ findings and the participants’ enjoyment of virtual languaging and their positive evaluation of peer languaging.

Languaging on Translation Tasks

Recently, translation has been viewed as a versatile language skill that is actively used by “intercultural mediators, foreign trade experts, international marketing professionals, global content managers, and multilingual secretaries or diplomats” (Calvo, 2011, p. 14). Despite a generally negative attitude toward using the mother tongue (L1) in L2 classrooms, translation is becoming an important communicative task and a learning tool (Cook, 2010; Ishikawa, 2015; Karim & Nassaji, 2013; Károly, 2014; Malmkjær, 1998; Suzuki, 2012). Illuminating the constructive role of translation in the L2 learning context, Nord (2005) argued that a contrastive analysis of the interlingual commonalities between the source and the target languages can develop metalinguistic awareness and improve language learning in translation tasks. In other words, translation can assist L2 learners to make smart decisions on their lexical and grammatical choices in the target language.

In terms of task outcomes, languaging on translation tasks can suitably raise deeper language processing and classroom interactions through interlingual comparisons (Heidari et al., 2019). According to Källkvist (2013), translation tasks can provide a forum where L2 learners can explore a wide range of language features including lexical, grammatical, and writing conventions. In other words, “this forum can generate more genuine communication than other tasks” (p. 229). Moreover, Suzuki and Itagaki (2009) speculated that performing form-focused tasks such as translation can positively affect the attributes of languaging episodes such as quantity and focus. Accordingly, in form-focused tasks, the L2 learners engage in form-meaning mapping in the target language, integrate the processing and producing of the target language form(s), and juxtapose their interlanguage form(s) with the target language model. Therefore, in L2 contexts where students and teachers usually speak a similar L1 such as in Japan (Ishikawa, 2013) or Iran (Moradian et al., 2017), translation tasks can generate a large body of languaging episodes which reciprocate further improvement in language learning.

Further support for the benefits of translation tasks goes back to Brooks and Donato (1994) who reported excessive L1-mediated oral interactions by L2 learners and supported the critical role of L1 as a common and normal psycholinguistic process. During the L1 languaging, the “utterances in L1 mediate the cognitive processes that learners use in problem-solving tasks, specifically, to reflect on the content and the form of the text” (Antón & DiCamilla, 1998, p. 238). Therefore, integrating languaging on translation tasks is believed to generate more language output, foster scaffolding, and externalize private speech in terms of languaging (Ishikawa, 2015).

This Study

This study was motivated by major gaps in the languaging literature:

Despite several arguments in favor of comparable impacts of oral languaging and WL on L2 learning improvement (Swain, 2005), several counter-arguments speculated such an equivalence (Storch, 2013; Suzuki, 2009). For instance, some research findings provided evidence of the superiority of WL over oral languaging for its potential to release the time pressure that L2 learners experience or its relative permanency (Ishikawa, 2015; Ishikawa & Suzuki, 2016; Suzuki, 2009).

SLA researchers have mostly focused on the mediating role of oral self-languaging (Qi & Lapkin, 2001; Suzuki, 2012) in L2 learning improvement, whereas the effectiveness of pair languaging in written mode is under-documented.

Finally, SLA languaging literature lacks the cross-examination of the WL attributes in pair/self-languaging dynamics.

Therefore, it was attempted to analyze the attributes of WL episodes (quantity, focus, and underlying conceptual processes) across the dynamics of pair and self-languaging on the form-focused translation tasks. To fulfill the objectives of the study, the following research questions were raised:

(1) Do the pair/self-languaging dynamics have any differential impacts on the quantity of WL episodes?

(2) Do the pair/self-languaging dynamics have any differential impacts on the focus of WL episodes?

(3) Do the pair/self-languaging dynamics have any differential impacts on the underlying conceptual processes of WL episodes?

(4) Do the pair/self-languaging dynamics have any differential impacts on EFL learners’ L2 learning improvement?

Method

Participants

This research was conducted in 2019, a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Out of a pool of 71 volunteers, 60 Persian-speaking EFL learners (25 females and 35 males) who were undergraduate students majoring in English Translation Studies were selected to take part in this study. The participants were non-randomly selected through convenience sampling. Their ages ranged from 23 to 26 years (M = 24.02, SD = 0.99), and the average length of their exposure to English in formal schooling was 12.2 years. The participants had been receiving instructions both in English and Persian (L1) in the course-related subjects, such as translation of political and journalistic texts, and academic writing. However, English was the dominant medium of instruction in their classrooms, adhered to the curriculum.

Since findings in Ishikawa and Suzuki (2016) and Watanabe and Swain (2007) indicated that the EFL learners’ level of language proficiency can play a critical role in optimizing the attributes of languaging, it was decided to select a homogeneous sample of participants with high proficiency by running the Oxford Placement Test (OPT, Version 1.1, 2001). The participants’ OPT scores indicated their language proficiency as advanced level (48–54, C1 in OPT ranking system) (M = 50.00, SD = 0.41, Cronbach’s α = 0.802).

The researchers in this study were two university professors with a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics and 14 years of teaching in various translation courses, and a professional translator with a Master’s degree in English Translation Studies.

Treatment Tasks of Translation

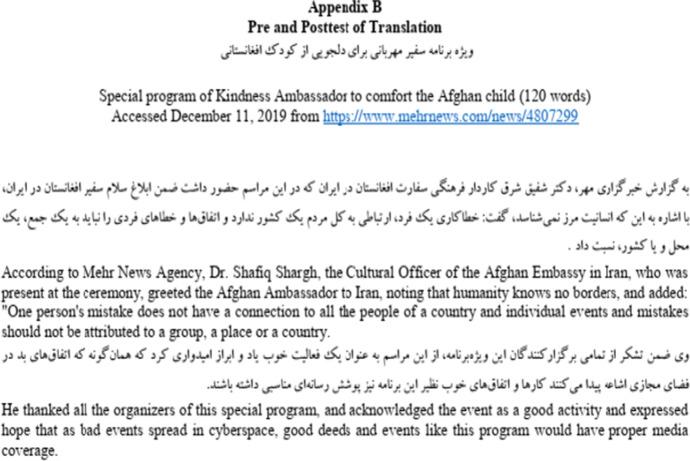

A set of Persian-to-English translations (N = 3) was prepared as the treatment tasks in this study (Appendix 1). The collected WL episodes on these tasks were analyzed for their quantity, focus and conceptual processing. The tasks input consisted of three authentic passages extracted from a Persian news website (www.mehrnews.com) in December 2019. The content of every translation task consisted of four to six sentences (counted words = 86 to 108, M = 22), with a readability index of 55.10 in the Flesch Reading Ease scoring system. The readability index was interpreted as challenging enough to trigger a large number of WL episodes. The participants were required to engage in producing WL while completing the translation tasks for a total of 40 min. The corresponding English model translation to every task was prepared by the researchers collaboratively (Cronbach’s α = 0.901) and presented to the languagers at Stage 2 of task completion.

The developed translation tasks were stage-wise. The pair and self-languagers completed the translation tasks by producing their translation at Stage 1, comparing it with the model translation to notice their errors at Stage 2, and revising their translation at Stage 3. This condition created an output–input sequence similar to the recast type of feedback (Ishikawa, 2015). The logic behind developing procedural tasks was to analyze how languaging dynamics might affect the languagers’ performance on translation tasks to address research questions 1 to 3.

Summative Assessment Tasks of Translation

We adopted a pretest–posttest design to assess the participants’ translation outcomes summatively. The participants were asked to complete an identical Persian-to-English translation task (without WL) which functioned as the pretest and posttest. The passage consisted of four Persian sentences with (counted words = 115, M = 29) retrieved in December 2019 from the Mehr News website. The readability index of the passage was measured as 57.30 (i.e., fairly difficult to read) in the Flesch Reading Ease scoring system.

The target quality criteria for rating the participants’ performance on the pretest and posttest were their accuracy of lexical choices and grammatical structures (Appendix 2). Therefore, the translation outcomes were co-rated by calculating the percentages of the correct translated items. The inter-rater reliability was measured as Cronbach’s α = 0.782, representing strong inter-rater reliability. The discrepancies in rating were consulted and resolved case-by-case.

Analysis of WL Episodes

Swain and Lakpin (2002, p. 326) provided the operational definition of a languaging episode as “any part of a dialogue where the students talk about the language they are producing, question their language use, or correct themselves or others.” To analyze the collected WL data, we collaborated in counting the WL episodes produced by the pair and self-languagers and reached an inter-rater agreement of 98.4%. Those WL episodes which could not be labeled for their focus such as “OK,” “really?,” or “wait a minute,” or the WL episodes produced over the spelling or punctuations of the word were eliminated from further analysis. To examine the focus of WL episodes, we adopted Yang’s (2016) typology:

Grammar-focused (G-WL) episodes address different aspects of morphology or syntax, including the use of articles, tense, or voice.

Lexis-focused (L-WL) episodes address word choices, word meaning, or equivalence.

Finally, WL episodes were analyzed in terms of the conceptual processes or “units” underlying the WL episodes, following the classification in Swain et al. (2009):

Paraphrasing: repeating a conceptual unit in the source text;

Inferencing: including integration (using the metalinguistic terms while translating), elaboration (comparing and contrasting the equivalents in L1 and L2), and hypothesis formation (formulating a hypothesis about the quality and accuracy of translation);

Analyzing: breaking the sentence in the source text into different parts of speech or semantic roles;

Self-assessment: monitoring one’s understanding of the source text;

Rereading;

Data Collection Procedure

Since producing WL is not a natural practice in any language learning experience, we strongly believed that training in WL production was necessary. Therefore, this study commenced by launching a two-day extra-curricular workshop on Languaging on Translation. It was held in four sessions of 90 min. In this workshop, the 71 attending volunteers were introduced to the notion of WL, its focus, and its seven conceptual processes (i.e., paraphrasing, inferencing including integration, elaboration, hypothesis formation, analyzing, self-assessment, and rereading). At the outset, one of the researchers demonstrated how to translate a Persian sentence into English Arya dar sokout goosh faraa midad. (= Arya was listening in silence.) while languaging in written mode.

When the researcher was translating the verb goosh faraa midad into “was listening,” she wrote a red-colored sentence on the margin of the whiteboard (should I use a simple verb or should I use –ing form here?) (as an example of the Integration process in WL). Or, when she was translating dar sokout (= in silence) which was moved from the mid-position in the Persian sentence to the final position in English translated sentence, she wrote on the margin of the board (Let’s see if it sounds better to put “in silence” between “was” and “listening”) as an example of hypothesis formation in WL.

After the tutorial was over, the participants engaged in translating by pair and self-languaging interchangeably. So, the self-languagers wrote their WL episodes in solitary, in parallel to the pair languagers who collaborated in producing WL episodes. Next, the OPT was administered to select a homogeneous sample of participants. After excluding 11 outliers whose scores were below the threshold of C1, the remaining participants signed a consent form and were voluntarily assigned into two groups of pair languagers (hereafter, PL) (N = 15 pairs) and self-languagers (hereafter, SL) (N = 30 individuals). In Week 2, the participants were pretested for 20 min.

In Weeks 3–5, the participants in both PL and SL groups were required to produce WL episodes on three weekly translation tasks, while they were translating the passage (Stage 1), comparing their translation output against a model translation to notice the mismatches (Stage 2), and revising their translation accordingly (Stage 3) (Table 1). In Week 6, the participants worked on a posttest of translation identical to the pretest (without languaging) for 20 min. To minimize the chances of oral languaging and verbal interactions, the participants were required to share their user IDs in Telegram™, a free and open-source mobile application.

Table 1.

Data collection framework

| Week 1 | Two-day Workshop of “Languaging on Translation” (6 h: 4 sessions) | |||||

| Week 1 | Oxford Placement Test (45 m) + Group Assignment | |||||

| Week 2 | Pretest of Translation (20 m) | |||||

| Stage | PL Group | Duration | Stage | SL Group | Duration | |

| Week 3 | 1 | Translating + pair languaging | 20 m | 1 | Translating + self-languaging | 20 m |

| 2 | Comparing to the model | 10 m | 2 | Comparing to the model | 10 m | |

| Translation | translation + pair languaging | translation+ self-languaging | ||||

| Task # 1 | 3 | Revising translation + pair | 10 m | 3 | Revising translation + self- | 10 m |

| languaging | languaging | |||||

| Week 4 | Translation Task 2 (40 m) | |||||

| Week 5 | Translation Task 3 (40 m) | |||||

| Week 6 | Posttest of Translation (20 m) | |||||

Every week, the translation tasks were sent to the private chatrooms of the pair and self-languagers and their translations were collected accordingly. The researchers coordinated the procedures as the administrators of the Telegram chatrooms. They also downloaded and printed the translations along with the WL episodes for future content analysis. The procedure is summarized in Table 1.

In Table 2, samples of WL episodes by pair languagers in the PL group and a self-languager in the SL group were presented for the second sentence of Translation Task # 3. As illustrated in Table 2, while the pair and self-languaging counterparts produced a rather similar amount of WL episodes (15 and 13, respectively), the distributions of G-WL and L-WL episodes and the types of conceptual processing are notably different at three stages of the task completion as both within- and between-group sources of difference.

Table 2.

Samples of WL episodes produced by pair and self-languagers

| Stage 1: Translating: Nirouhaye raahdari dar amadehbash hastand. (= The road maintenance force is on standby.) | |||||

| Pair languagers in PL group | WL Focus | WL Conceptual Process | A self-languager in the SL group | WL Focus | WL Conceptual Process |

|

A: I think rahdari doesn’t have an equivalent in English! B: “keeping road”? A: I haven’t heard this word before A: What about “road police”? B: You mean like “patrol”? A: Yes! Road patrol B: OK Uploaded output: The road patrol is on standby |

L-WL L-WL L-WL L-WL L-WL L-WL |

elaboration hypothesis formation self-assessment hypothesis formation elaboration hypothesis formation |

- I am not sure. Can I say “sheriff”? - I don’t have any word for it. But I am sure I have seen this word before! - …. are ready? - Ready for what? - dar amadehbash, is it a verb or an adverb in this sentence? - It was a difficult sentence for me! Uploaded output: The sheriff are ready |

L-WL L-WL L-WL L-WL G-WL G-WL |

hypothesis formation self-assessment hypothesis formation analyzing/integration integration self-assessment |

| Total WL episodes: 6 | Total WL episodes: 6 | ||||

| Stage 2: Comparing to the model translation: The road maintenance force is on standby | |||||

|

A: Oh, “road maintenance force”! We had it before B: Really? A: Yes, we had it last semester A: We were correct about “standby.” A: The word “force” shouldn’t be plural in meaning? A: So why not “… are standby”? B. I don’t know! |

L-WL L-WL G-WL G-WL G-WL |

re-reading self-assessment analyzing/integration hypothesis formation self-assessment |

- My translation was completely wrong! - “Road maintenance” officers or force? - I think it should be “officers.” - “Standby” is a good adjective! - I totally forgot “standby”! |

G-WL L-WL L-WL L-WL L-WL |

self-assessment elaboration hypothesis formation integration self-assessment |

| Total WL episodes: 7 | Total WL episodes: 5 | ||||

| Stage 3: Revising | |||||

|

B: Do we want to change any word, anything else? A: Nothing! It is correct B. OK Submitted output: The road maintenance force is on standby |

L-WL G-WL |

self-assessment self-assessment |

- I like “officers” more than “force.” - In fact, I think “force” is not correct for those who protect the roads! Submitted output: The road maintenance officers are standby |

L-WL L-WL |

self-assessment paraphrasing |

| Total WL episodes: 2 | Total WL episodes: 2 | ||||

Results

To explore the first three research questions, the WL episodes produced by the pair and self-languagers on the treatment tasks were collected and analyzed for their quantity, focus, and underlying conceptual processes. Next, to address the fourth research question, the percentages of correctly translated items on the pretest and posttest were obtained for the PL and SL groups and statistically analyzed by running a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Quantity of WL Episodes

The first research question queried the possible differences in the amount of WL episodes produced by pair and self-languagers. As Table 3 displays, the pair languagers produced more WL episodes than the self-languagers (2398 to 2100) at three stages of task completion. Moreover, it can be seen that the quantity of WL episodes was dropped off from Stage 1 (N = 2413) and Stage 2 (N = 1602) to Stage 3 (N = 480) by both groups.

Table 3.

Quantity of WL episodes in pair and self-languagers

| Task Group | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| 1 |

PL SL |

380 | 192 | 80 |

| 340 | 184 | 64 | ||

| 2 |

PL SL |

428 | 318 | 80 |

| 404 | 240 | 72 | ||

| 3 |

PL SL |

444 | 380 | 96 |

| 420 | 288 | 88 | ||

| Total |

PL SL |

1252 (52.42) | 890 (55.55) | 256 (53.33) |

| 1161 (47.58) | 712 (44.44) | 224 (46.67) | ||

To examine the significance of the observed between-group differences in the amounts of WL episodes, a cross-tabulation was conducted for the languaging dynamics (pair vs. self) and the amount of WL episodes. The result was significant (Pearson χ2 (4498) = 20.79, p < 0.00, Cramer’s V = 0.59, interpreted as a medium effect size) which supported the advantage of pair languagers in terms of producing more WL episodes.

The Focus of WL Episodes

To address the second research question, we cross-examined the distribution of G-WL and L-WL episodes produced by pair and self-languagers at three stages of task completion (Table 4). As indicated in Table 4, both pair and self-languagers produced more L-WL than G-WL episodes at every stage of task completion. Also, it can be seen that pair languagers produced more L-WL episodes (1688 to 1323, respectively), and the self-languagers produced more G-WL episodes (774 to 710, respectively) at three stages of completing translation tasks.

Table 4.

Distribution of G-WL and L-WL episodes in pair and self-languagers

| Task Group | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-WL | L-WL | G-WL | L-WL | G-WL | L-WL | ||

| N (%) of Total |

N (%) of Total |

N (%) of Total | N (%) of Total | N (%) of Total | N (%) of Total | ||

| 1 |

PL SL |

80 | 278 | 102 | 112 | 20 | 60 |

| 91 | 284 | 120 | 93 | 25 | 39 | ||

| 2 |

PL SL |

87 | 326 | 102 | 231 | 12 | 68 |

| 78 | 189 | 151 | 162 | 23 | 49 | ||

| 3 |

PL SL |

112 | 269 | 175 | 268 | 20 | 76 |

| 103 | 259 | 161 | 185 | 22 | 66 | ||

| Total |

PL SL |

272 (49.37) | 873 (54.49) | 379 (46.73) | 611 (64.24) | 52(42.62) | 204 (56.82) |

| 279 (50.63) | 729 (45.50) | 432 (53.26) | 440 (37.75) | 70(53.37) | 154 (43.17) | ||

To explore the significance of the observed differences in the proportions of the G-WL and L-WL episodes across pair and self-languagers, we ran a table of contingency for the languaging dynamics and the focus of WL episodes. The result was significant (Pearson χ2 (3, 4498) = 44.32, p = 0.00, Cramer’s V = 0.60, representing a medium effect size) which was interpreted as the main effect of languaging dynamics on the focus of WL episodes.

Conceptual Processes Underlying WL Episodes

The third research question explored the relative distribution of the conceptual processes underlying WL episodes by the pair and self-languagers (Table 5). Descriptive statistics reported a similar but uneven pattern in conceptual processes by pair and self-languagers (2400 to 2100, respectively). Accordingly, among the types of conceptual processes, self-assessment (N = 1576) and hypothesis formation (N = 1420) underlined the majority of WL episodes by pair and self-languagers, while rereading (N = 144) was the least frequent process involved in producing WL episodes.

Table 5.

Distribution of conceptual processes underlying WL episodes in pair and self-languagers

| Task Group | Paraphrasing | Integration | Elaboration | Hypothesis Formation |

Analyzing | Self-assessment | Rereading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| 1 | PL | 40 | 40 | 24 | 216 | 56 | 260 | 16 |

| SL | 24 | 32 | 48 | 224 | 48 | 244 | 32 | |

| 2 | PL | 56 | 32 | 56 | 274 | 88 | 298 | 24 |

| SL | 40 | 56 | 48 | 204 | 88 | 208 | 8 | |

| 3 | PL | 72 | 72 | 80 | 256 | 120 | 280 | 40 |

| SL | 64 | 48 | 48 | 246 | 80 | 286 | 24 | |

| Total | PL | 168 (56.75) | 144 (51.42) | 160 (52.63) | 746 (52.53) | 264 (55.00) | 838 (53.17) | 80 (55.55) |

| SL | 128 (43.24) | 136 (48.57) | 144 (47.36) | 674 (47.46) | 216 (45.00) | 738 (46.82) | 64 (44.44) | |

The significance of the observed differences in the proportions of conceptual processes by pair and self-languagers was examined by running another cross-tabulation between the languaging dynamics and seven conceptual processes. The result was insignificant (Pearson χ2 (4500) = 0.70, p = 0.19, Cramer’s V = 0.16, interpreted as a weak effect size) which indicated no between-group differences for pair and self-languagers.

Pair/Self-Languaging Dynamics and Language Learning Improvement

To address the fourth research question, a one-way ANOVA was conducted between the languaging dynamics as the between-group variable and time (pretest–posttest) as the within-group variable. We assumed the pair and self-languagers’ improved performance on the pretest to the posttest summative assessment as a sign of language learning improvement.

Before running the test of ANOVA, primary descriptive statistics reported the average percentages of correctly translated items in pretest and posttest by the PL group (M pretest = 40.65 ± 7.19 and M posttest = 85.60 ± 6.12) and the SL group (M pretest = 36.72 ± 7.05 and M posttest = 73.27 ± 5.73), respectively.

The results of one-way ANOVA indicated no significant effect of time [F (1, 58) = 2.875, p > 0.05], but the significant effect of languaging dynamics [F (1, 58) = 40.698, p < 0.05, η2 = 2.12, interpreted as a strong effect size]. In other words, while both pair and self-languagers showed considerable language learning improvement, pair languagers outperformed self-languagers on the posttest.

Discussion

The first research question is discussed in terms of the outnumbered WL episodes by pair languagers to accentuate the role of collaboration in languaging and language learning. Our findings are anchored in Vygotsky’s SCT model which substantiates the role of social mediation from the more knowledgeable (e.g., teachers or peers) to the less knowledgeable (novice) L2 learners (Donato, 1994; Storch, 2008; Vygotsky, 1987). As Donato (1994, p. 8) suggested, collaborative languaging can become a “collective cognitive activity which serves as a transitional mechanism from the social to internal planes of psychological functioning.” In other words, collaboration might amplify the languaging effect when languagers co-construct a message in the target language.

Secondly, the number of WL episodes dramatically decreased from Stage 1 when both pair and self-languagers actively engaged in languaging and translating, through Stage 2 when they were offered a translation model to notice their errors, to Stage 3 of revising their translation. Such a descending pattern in the quantity of WL episodes might be due to the unloading cognitive demands in both pair and self-languagers. In other words, once they began to resolve their errors at Stage 3, in the absence of teacher corrective feedback, they seemed unable to pay more selective attention to their task outcome or produce more WL episodes (Gass & Mackey, 2006; Pourdana & Behbahani, 2012; Pourdana et al., 2014; Suzuki & Itagaki, 2009).

Our findings are consistent with several SLA studies in the languaging literature (Storch, 2008; Vygotsky, 1987). For instance, in an experiment with Japanese EFL learners, Watanabe and Swain (2007) argued that once L2 learners take part in peer–peer collaborative languaging, they could benefit more in learning vocabulary and grammar than languaging in solitary. Our findings, however, were inconsistent with findings in Borer (2007) who reported mutual impacts of collaborative dialogue and self-talk on learning five unknown words by eight English-for-academic-purposes (EAP) students, while they were completing writing tasks. Borer (2007) reported results are arguably inconclusive due to the small size of the participants and subsequent collected languaging data.

Our discussion of the second research question which examined the focus of WL episodes (G-WL and L-WL) produced by pair and self-languagers is twofold. Firstly, it was found that the total number of L-WL episodes exceeded the G-WL episodes at three stages of task completion. Yet, pair languagers produced more L-WL episodes than self-languagers. In other words, pair languagers focused more on the lexical choices and target language equivalents than self-languagers whose concern was more about the accuracy of grammatical structures. To account for this observation, we concentrate on the role of positive and negative evidence which is largely exchanged in peer–peer collaboration of any nature, including WL.

Positive/negative evidence refers to sending or receiving signals about what is or is not possible in the target language (Long, 2006). In pair languaging, the abundant peer feedback, recast, and requests for clarification—as common techniques of negative and positive evidence—could stimulate selective attention to the content of the message as well as “incidental focus on form” (Loewen, 2005, p. 361). In other words, pair languagers focused more on conveying the message as accurately as possible at the cost of preserving language form(s) (Watanabe & Swain, 2007). In the absence of positive and/or negative evidence, self-languagers had to produce WL episodes more on the target language forms to self-repair and revise their translation output by themselves. For instance, referring to the samples of WL episodes in Table 2, to find the proper English equivalent for rahdari (= road maintenance force) at Stage 1, the pair languagers produced six L-WL episodes by sharing ideas and coming to an agreement over the word “road patrol.” In parallel, the self-languager stopped languaging to find the same English equivalent after only four L-WL episodes and came up with the word “sheriff” (incorrect choice of words).

Studies on collaborative languaging are a few, among which Hanaoka (2007) and Williams (2001) are prominent and consistent with our findings. To explore the noticing effects of metacognitive output (i.e., languaging effect), Hanaoka (2007) examined 37 Japanese EFL college students with a procedural writing task. His findings indicated that the collaborative languagers noticed lexical choices much more than grammatical features and incorporated them more into their subsequent writings. In a case study, Williams (2001) likewise examined the chances of collaborative languaging on focus-on-form (FoF) tasks with eight EFL learners and found that except for the cases of “request for assistance from the teacher,” the L2 learners randomly attended to language form in their languaging episodes. The findings in our study are not supported by Yang (2016) who explored the role of WL to facilitate eight Chinese EFL learners’ performance on a procedural form-focused task. The participants’ engagement in languaging was later analyzed in terms of the rates of L-WL and G-WL episodes. Yang’s findings indicated that when the participants engaged in language production, they produced a high number of L-WL episodes, but at the comparing and revising stages, they generated more G-WL episodes.

The findings on the third research question suggested that both pair and self-languagers relied more upon self-assessment and hypothesis formation processes in producing WL episodes. In other words, through languaging, the participants were able “to form and test their hypotheses about the appropriate and correct use of language, as well as reflect on their language use” (Swain et al., 2009, p. 3). It is speculated that both pair and self-languagers’ hypothesis formation followed by self-assessment could raise an opportunity for self-repair and critical reflection, especially by comparing their task output to the model translation at Stage 2. For instance, reported in Table 2, when the self-languager noticed the mismatch between her translation output and the model translation, she refused to resolve her WL episodes. Instead, she critically evaluated the model translation and puzzled between the “road maintenance officers and force.” She continued self-languaging by writing “I think it should be officers,” or “I think force is not correct for those who protect the roads!”. Eventually, the self-languager refused to revise her wrong choice of English equivalent (i.e., unsuccessful resolution).

The findings on the distribution of conceptual processes partly corroborate Swain et al. (2009) and Knouzi et al. (2010). In a case study with French-as-a-Foreign-Language (FFL) learners, Swain et al. (2009) explored the role of languaging in learning the concept of voice in a grammar course. They analyzed the languaging episodes into five major conceptual units of paraphrasing, inferencing, analyzing, self-assessment, and rereading. They further reported that the higher-level languagers self-assessed more than the mid-level and lower-level languagers who preferred rereading more than other conceptual processes of languaging. To further examine the quality of languaging in successful language learners, Knouzi et al. (2010) analyzed the conceptual processes of higher-level and lower-level languagers and monitored their learning of voice in French grammar. They reported “better-quality” languaging in the higher-level languagers.

To address the fourth research question, the statistical analysis indicated language learning improvement in both pair and self-languagers in terms of pretest-to-posttest achievement and the outperformance of pair languagers on the posttest. From the Vygotskyan SCT viewpoint, we might deliberate the pair languagers’ observed benefit once again as a result of collaboration. Accordingly, the pair languagers externalized and shared their thoughts more frequently than the self-languagers, which could account for deeper processing of the target language. Seemingly, by the cohort of collaboration and languaging, pair languagers could regulate each other’s cognitive activities, co-construct complex language structures, and eventually optimize their language learning improvement (Williams, 2001). Our results are in line with Niu (2009) Niu and Li (2017) who investigated the eight pairs of Chinese EFL learners’ languaging on two collaborative speaking and writing tasks. Her analysis of the languaging episodes reported the pair languagers’ larger quantity of languaging episodes, more attention to language form, and better language learning improvement on the writing task.

Conclusion and Implications

This study investigated the potential of the pair/self-languaging dynamics in determining the attributes of WL (quantity, focus, and conceptual processing) and improving EFL learners’ translation tasks performance. The results supported that languaging dynamics could prominently affect the quantity and focus of WL episodes, but not the conceptual processes underlying WL episodes. In other words, pair languagers could produce more WL episodes and focus more on lexical items (L-WL episodes) than self-languagers, yet both pair and self-languagers engaged in similar conceptual processes in producing WL. Moreover, in the face of mutual progress by pair and self-languagers on their pretest-to-posttest translation performance, pair languagers benefitted more from languaging in terms of their posttest gain scores.

In light of the findings of this study, several implications are suggested to future SLA researchers and L2 practitioners. First and foremost, the pedagogical standpoint of oral and written languaging in the L2 teaching context might have an interesting and worth-thinking prospect. Therefore, L2 teachers are highly recommended to create opportunities for different modes of languaging both in and out of the classroom by training L2 learners how to language. To benefit more, the teacher-imposed languaging can be carried out to redefine languaging as a task rather than a task by-product (Niu, 2009), so that it offers the teachers with better access to the students’ inner talks. Also, the languagers’ agency and perception of languaging which was beyond the scope of this study has been under-documented and requires further research. Languagers’ stance on different languaging dynamics, languaging modes (i.e., oral or written), or modalities (i.e., face-to-face or computer-mediated) can engage them more in languaging and mediate their language learning progress. Moreover, the L2 teachers are encouraged to adopt an alternative approach to translation to benefit the potential of translation tasks as a platform to raise more awareness of the complex linguistic structures.

The arguments in this research are still inconclusive due to some limitations. One of the major blocking factors was the time restriction that was imposed upon us due to the surge of the COVID-19 pandemic and the following lockdowns. It costs us several adjustments to our communications for data analysis, deadlines, and follow-up discussions. The next limitation was the non-random sampling of the participants. The selected participants were EFL university students who volunteered to join the study. As a result, their enthusiasm and advanced level of language proficiency could have positively affected the attributes of languaging (Knouzi et al., 2010; Li, 2015) in various aspects. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings to L2 learners with different proficiency levels or levels of task engagement should be done cautiously.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Funding

There is no funding for this research.

Data Availability

Please contact the corresponding author at Natasha.qale@gmail.com for data requests.

Declarations

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Elnaz Keshanchi, Email: eli.keshanchi@gmail.com.

Natasha Pourdana, Email: Natasha.pourdana@kiau.ac.ir, Email: Natasha.Qale@gmail.com.

Gholamhassan Famil Khalili, Email: khalili@kiau.ac.ir, Email: familkhalili@yahoo.com.

References

- Antón M, DiCamilla F. Socio-cognitive functions of L1 collaborative interaction in the L2 classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review. 1998;54:314–342. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.54.3.314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behbahani SMK, Pourdana N, Maleki M, Javanbakht Z. EFL task-induced involvement and incidental vocabulary learning: succeeded or surrounded. In International Conference on Languages, Literature and Linguistics. IPEDR Proceedings. 2011;26:323–325. [Google Scholar]

- Borer L. Depth of processing in private and social speech: Its role in the retention of word knowledge by adult EAP learners. Canadian Modern Language Review. 2007;64:269–295. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.64.2.269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks FB, Donato R. Vygotskian approaches to understanding foreign language learner discourse during communicative tasks. Hispania. 1994;77:262–274. doi: 10.2307/344508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo E. Translation and/or translator skills as organizing principles for curriculum development practice. JoSTrans. 2011;16:5–25. [Google Scholar]

- de la Colina, A. A., & García Mayo, M. (2007). Attention to form across collaborative tasks by low-proficiency learners in an EFL setting. In M. P. García Mayo (Ed.), Investigating tasks in formal language learning (pp. 91–116). Multilingual Matters.

- Cook G. Translation in language teaching. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DiCamilla FJ, Lantolf JP. The linguistic analysis of private writing. Language Sciences. 1994;16:347–369. doi: 10.1016/0388-0001(94)90008-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donato R. Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In: Lantolf JP, Appel G, editors. Vygotskian approaches to second language research. Ablex; 1994. pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gass S, Mackey A. Input, interaction and output in SLA. In: VanPatten B, Williams J, editors. Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction. Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka O. Output, noticing, and learning: An investigation into the role of spontaneous attention to form in a four-stage writing task. Language Teaching Research. 2007;11(4):459–479. doi: 10.1177/1362168807080963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari S, Pourdana N, Famil Khalili GF. Retrospective and introspective think-aloud protocols in translation quality assessment: A qual-quan mixed methods research. Language and Translation. 2019;9(4):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M. Examining the effect of written languaging: The role of metanotes as a mediator of second language learning. Language Awareness. 2013;22(3):220–233. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2012.683435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M. Metanotes (written languaging) in a translation task: Do L2 proficiency and task outcome matter? Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching. 2015;9(2):115–129. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2013.857342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Suzuki W. The effect of written languaging on learning the hypothetical conditional in English. System. 2016;58:97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2016.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi S. Output, input enhancement, and the noticing hypothesis: An experimental study on ESL relativization. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 2002;24:541–577. doi: 10.1017/S0272263102004023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Källkvist M. Languaging in translation tasks used in a university setting: Particular potential for student agency? The Modern Language Journal. 2013;97(1):217–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.01430.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karim K, Nassaji H. First language transfer in second language writing: An examination of current research. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research. 2013;1(1):117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Károly K. Translation in foreign language teaching: A case study from a functional perspective. Linguistics and Education. 2014;25:90–107. doi: 10.1016/j.linged.2013.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knouzi I, Swain M, Lapkin S, Brooks L. Self-scaffolding mediated by languaging: Microgenetic analysis of high and low performers. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. 2010;20(1):23–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00227.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. Effect of languaging on the acquisition of tense and aspect. Papers on Education. 2015;19:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Loewen S. Incidental focus on form and second language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 2005;27(3):361–386. doi: 10.1017/S0272263105050163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long M. Recasts: The story so far. In: Long MH, editor. Problems in SLA. Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 75–116. [Google Scholar]

- Malmkjær K. Introduction: Translation and language teaching. In: Malmkjær K, editor. Translation and language teaching: Language teaching and translation. St. Jerome; 1998. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Moradian MR, Miri M, Nasab MH. Contribution of written languaging to enhancing the efficiency of written corrective feedback. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. 2017;27(2):406–421. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negueruela, E. (2003). Systemic-theoretical instruction and L2 development: A sociocultural approach to teaching-learning and researching L2 learning. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

- Negueruela E. Revolutionary pedagogies: Learning that leads to second language development. In: Lantolf JP, Poehner M, editors. Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages. Equinox Press; 2008. pp. 189–227. [Google Scholar]

- Negueruela, E., & Lantolf J. P. (2006), Concept-based pedagogy and the acquisition of L2 Spanish. In R. M. Salaberry & B. A. Laftolf (Eds,), The art of teaching Spanish: Second language acquisition from research to praxis (pp. 79–102). Washington DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Niu R. Effect of task-inherent production modes on EFL learners' focus on form. Language Awareness. 2009;18(3–4):384–402. doi: 10.1080/09658410903197256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu R, Li L. A Review of Studies on Languaging and Second Language Learning (2006–2017) Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 2017;7(12):1222–1228. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0712.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nord, C. (2005). Text analysis in translation: Theory, methodology, and didactic application of a model for translation-oriented text analysis (2nd ed.). Rodopi.

- Pourdana N, Sahebalzamani S, Rajeski JS. Metaphorical awareness: A new horizon in vocabulary retention by Asian EFL learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature. 2014;3(4):213–220. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.3n.4p.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pourdana, N., & Behbahani, S. M. K. (2012). Task types in EFL context: Accuracy, fluency, and complexity in assessing writing performance. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 2(1), 10.7763/IJSSH.2012.V2.73

- Pourdana, N., Nour, P., & Yousefi, F. (2021). Investigating metalinguistic written corrective feedback focused on EFL learners’ discourse markers accuracy in mobile-mediated context. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 6(7), 10.1186/s40862-021-00111-8

- Qi DS, Lapkin S. Exploring the role of noticing in a three-stage second language writing task. Journal of Second Language Writing. 2001;10:277–303. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(01)00046-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storch N. Metatalk in a pair work activity: Level of engagement and implications for language development. Language Awareness. 2008;17(2):95–114. doi: 10.1080/09658410802146644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storch N. Collaborative writing in L2 classrooms. Multilingual Matters; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki W. Improving Japanese university students' second language writing accuracy: Effects of languaging. Annual Review of English Language Education in Japan. 2009;20:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki W. Written languaging, direct correction, and second language writing revision. Language Learning. 2012;62(4):1110–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2012.00720.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki W, Itagaki N. Languaging in grammar exercises by Japanese EFL learners of differing proficiency. System. 2009;37:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2008.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swain M. The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In: Hinkel E, editor. The handbook of research in second language teaching and learning. Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 471–483. [Google Scholar]

- Swain M. Languaging, agency and collaboration in advanced second language proficiency. In: Heidi B, editor. Advanced language learning: The contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky. Continuum; 2006. pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Swain M, Lapkin S. Interaction and second language learning: Two adolescent French immersion students working together. The Modern Language Journal. 1998;82:320–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01209.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swain M, Lapkin S. Focus on form through collaborative dialogue: Exploring task effects. In: Bygate M, Skehan P, Swain M, editors. Researching pedagogic tasks: Second language learning, teaching and testing. Longman; 2001. pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Swain M, Lapkin S. Talking it through: Two French immersion learners’ response to reformulation. International Journal of Educational Research. 2002;37(3&4):285–304. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00006-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swain M, Suzuki W. Interaction, output and communicative language learning. In: Spolsky B, Hult FM, editors. The handbook of educational linguistics. Blackwell; 2008. pp. 557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Swain M, Lapkin S, Knouzi I, Suzuki W, Brooks L. Languaging: University students learn the grammatical concept of voice in French. The Modern Language Journal. 2009;93:5–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00825.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swain M., & Watanabe, Y. (2013). Languaging: Collaborative Dialogue as a Source of Second Language Learning. In C. A. Chapelle, The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (Ed.) (pp. 3218–3225). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Tocalli-Beller A, Swain M. Reformulation: The cognitive conflict and L2 learning it generates. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. 2005;15:5–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-4192.2005.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tocalli-Beller A, Swain M. Riddles and puns in the ESL classroom: Adults talk to learn. In: Mackey A, editor. Conversational interaction in second language acquisition. Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton (Eds.), The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky: Vol. 1: Problems of general psychology (pp. 39–285). Plenum.

- Watanabe Y, Swain M. Effects of proficiency differences and patterns of pair interaction on second language learning: Collaborative dialogue between adult ESL learners. Language Teaching Research. 2007;11:121–142. doi: 10.1177/136216880607074599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. Learner-generated attention to form. Language Learning. 2001;51(2):303–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.2001.tb00020.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. Languaging in story rewriting tasks by Chinese EFL students. Language Awareness. 2016;25(3):241–255. doi: 10.1080/09658416.2016.1197230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng G, Takatsuka S. Text-based peer-peer collaborative dialogue in a computer-mediated learning environment in the EFL context. System. 2009;37(3):434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2009.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author at Natasha.qale@gmail.com for data requests.