Abstract

In three Escherichia coli mutants, a change (Ala-51 to Val) in the gyrase A protein outside the standard quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) lowered the level of quinolone susceptibility more than changes at amino acids 67, 82, 84, and 106 did. Revision of the QRDR to include amino acid 51 is indicated.

The quinolones are antibacterial agents that act by forming ternary complexes with DNA gyrase and DNA topoisomerase IV on chromosomal DNA. Resistance to the compounds is generally associated with amino acid substitutions in portions of the GyrA (gyrase) and ParC (topoisomerase IV) proteins called the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) (20). In Escherichia coli, the GyrA QRDR spans amino acids 67 to 106, with alteration at positions 83 and 87 often associated with clinical resistance (19). A similar association with resistance has been observed for a variety of pathogens (1, 6, 12, 16, 17), suggesting that resistance is due to altered drug targets. The use of fluoroquinolones that mitigate the protective effects of alterations at positions 83 and 87 (7, 21) may cause other alleles to assume a more important role in reducing the level of susceptibility (4). To help define additional sites that may contribute to resistance, we examined three nalidixic acid-resistant mutants of E. coli that are also thermotolerant (2, 3).

Independent, nalidixic acid-resistant (Nalr) strains of E. coli CGSC 6353 (3) were obtained by selecting for growth on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (9) containing 20 μg of nalidixic acid per ml, and members of the thermotolerant (T/r+) subset were identified by growth on LB agar plates at 48°C. These strains were designated MF1, MF3, and MF4-1; a Nalr strain that lacked thermotolerance was designated MF13. Nalr was mapped by P1-mediated transduction (18), DNA was isolated by phenol extraction, PCR was used to amplify regions of the gyrA gene, and nucleotide sequences in amplified regions were determined by automated sequencing. The protective effect of the gyrA mutations was compared by determining the fluoroquinolone concentration required to inhibit colony formation by 99% (MIC99) rather than by standard MIC determinations to focus more sharply on bacteriostatic activity. For this measurement cells grown to the stationary phase in LB medium were diluted and applied to quinolone-containing agar plates; the colonies were counted after incubation at 37°C for 1 day. Preliminary determinations with twofold dilutions of the fluoroquinolone provided an approximate value for the MIC99; a second measurement, plus a replicate, then used linear drug concentration increments that were 10 to 20% of the MIC99. The numbers of colonies recovered were plotted against the drug concentration to determine the MIC99 by interpolation.

P1-mediated transduction showed that a gyrA mutation was associated with nalidixic acid resistance. In this experiment a zfa-3145::Tn10 Kanr marker, which is 70% cotransducible with gyrA, was first transferred by transduction from strain CAG 12183 (Nals Kanr) (14) into strain MF4-1 (Nalr T/r+). About 30% of the Kanr transductants retained the Nalr phenotype, indicating that a mutation at or near gyrA can confer nalidixic acid resistance. Then, the Nalr marker was transferred into wild-type cells. Two Kanr Nalr transductants (KD1719 and KD1720) from the initial transduction were used to prepare phage lysates that were used to infect the parental Nals strain (CGSC 6353) and two other wild-type strains, DM4100 (15) and C600 (5). Cotransduction frequencies between Kanr and Nalr were 70, 80, and 70% for the three recipient strains, respectively. Thus, a mutation at or near gyrA was sufficient to confer nalidixic acid resistance.

The change associated with Nalr in the gyrA QRDR was determined by nucleotide sequence analysis following PCR with primers 1037 and 1038 (Table 1). As shown in Table 2, the parental strain (CGSC 6353) had a predicted amino acid sequence identical to a sequence found in GenBank (accession no. X06744). In contrast, Nalr T/r+ mutants (strains MF4-1, MF1, and MF3) contained a change that altered amino acid 51 from alanine to valine. The Nalr mutant that was not thermotolerant, strain MF-13, had a 5′ base change (G to T) in codon 87 expected to reduce the level of quinolone susceptibility by substituting tyrosine for aspartic acid (11).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for PCR and sequence determination

| Oligonucleotide no. | Nucleotide sequence | Position in gyrA |

|---|---|---|

| 1037 | 5′-AGTGGATCCGTAATTGGCAAG ACAAACGAG-3′ | −110 to −134 |

| 1038 | 5′-CGGCCATCAGTTCATGGGCA-3′ | 390 to 409 |

| 1042 | 5′-TTGAATTCAAACAAGGGAGAT AGCTCC-3′ | 2651 to 2674 |

| 1043 | 5′-TACGGAAATCCGTCTGGCGA-3′ | 366 to 385 |

| 1044 | 5′-TCATTAACGGTCGTCGCGGT-3′ | 665 to 684 |

| 1045 | 5′-TCCCAGACCCAGTTGCAGGT-3′ | 964 to 984 |

| 1046 | 5′-TGCTCGAACGTGCTGGCGAC-3′ | 1268 to 1288 |

| 1047 | 5′-CGCCAACAGCGCAGACATCA-3′ | 1565 to 1585 |

| 1048 | 5′-GTCAACCTGCTGCCGCTGGA-3′ | 1858 to 1878 |

| 1049 | 5′-TCGCGGTATTCGCTTAGGTG-3′ | 2163 to 2183 |

| 1050 | 5′-CAGGGCGTGATCCTCATCCG-3′ | 2458 to 2478 |

TABLE 2.

Properties of nalidixic acid-resistant mutants

| Strain | Relevant phenotype | Nucleotide sequence (amino acid) in GyrA

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Codon 51 | Codon 87 | ||

| CGSC 6353 | Nals T/r− | GCC (Ala) | GAC (Asp) |

| MF4-1 | Nalr T/r+ | GTC (Val) | GAC (Asp) |

| MF1 | Nalr T/r+ | GTC (Val) | GAC (Asp) |

| MF3 | Nalr T/r+ | GTC (Val) | GAC (Asp) |

| MF13 | Nalr T/r− | GCC (Ala) | TAC (Tyr) |

To determine whether a Nalr T/r+ isolate contains additional changes in gyrA, we determined the sequence of the entire gene for parental (CGSC 6353) and mutant (MF4-1) strains. The gyrA gene was amplified with primers 1037 and 1042 (Table 1) and sequenced with primers 1043 through 1050 (Table 1). No further differences were observed between these two strains. Thus, an Ala-51-to-Val change in GyrA is sufficient to confer nalidixic acid resistance.

The Ala-51-to-Val substitution was neither necessary nor sufficient to confer thermotolerance: a Nals transductant of MF4-1 (strain KD1567) retained thermotolerance. Moreover, the Nalr transductants of CGSC 6353, DM4100, and C600 were not thermotolerant: Nalr transductants and their parental strains were indistinguishable with respect to growth on salt-free LB agar plates at both 43.5 and 46°C. In previous work (3), we reported that a plasmid-borne, wild-type gyrA gene suppressed both Nalr and T/r+, suggesting that a GyrA alteration was necessary for thermotolerance. Suppression of thermotolerance by expression of GyrA from a plasmid probably arises from the presence of multiple copies of the gyrA gene. The genetic basis for thermotolerance remains unclear.

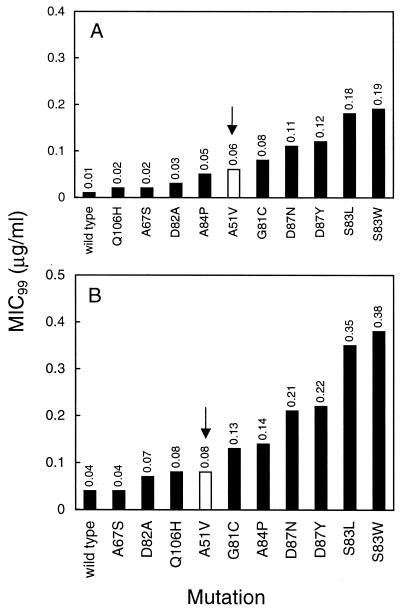

We compared the loss of quinolone susceptibility associated with the Ala-51-to-Val change to that seen with other GyrA variants. As shown in Fig. 1, Val-51 was associated with intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and gatifloxacin that was greater than that seen for four other amino acid changes generally considered to be within the QRDR (Ala-67 to Ser, Asp-82 to Ala, and Gln-106 to His). In the case of ciprofloxacin, this was also true for the Ala-84-to-Pro change. We conclude that the QRDR should be expanded to include position 51.

FIG. 1.

Relative susceptibilites of gyrase mutants to fluoroquinolones. The MIC99s (see text) of ciprofloxacin (A) and gatifloxacin (B) were determined for a series of GyrA variants and are indicated above each bar (each determination was made twice with similar results). For illustrative purposes, the results for the mutant with the Ala-51-to-Val substitution are shown in white and are indicated by the arrows. All strains are gyrA Nalr transductants of wild-type strain DM4100, as described in the text or elsewhere (8). Amino acid changes in the GyrA QRDR and strain numbers (in parentheses) are as follows: S83L (KD66), A51V (KD1721), A67S (KD1911), G81C (KD1915), S83W (KD1909), D87N (KD1913), Q106H (KD1917), D82A (KD1973), A84P (KD1975), and D87Y (KD1977).

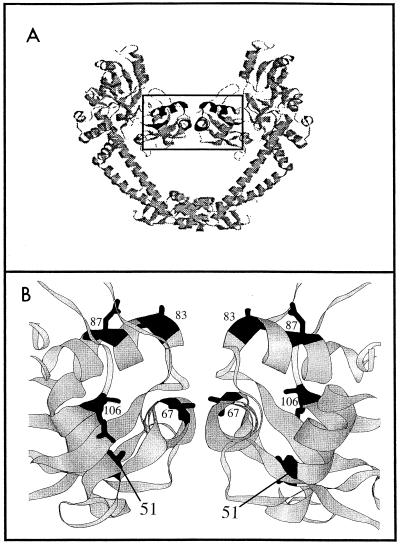

Examination of the crystal structure of the GyrA59 dimer (10) reveals that Ala-51 lies in helix 2, which is below the DNA recognition helix (helix 4; Fig. 2). Changes at positions 83 and 87 that cause the greatest loss in quinolone susceptibility are located on the surface of the recognition helix (Fig. 2), where quinolone binding may occur (8, 10, 13, 22). We speculate that the Ala-51-to-Val substitution distorts the region, altering its ability to interact with fluoroquinolones.

FIG. 2.

Structure of the GyrA59 dimer. The figure shows a ribbon representation (generated in RasMol) of the GyrA59 fragment (10), courtesy of J. G. Heddle (John Innes Centre, Norwich, United Kingdom). (A) The entire GyrA59 dimer. (B) An enlargement of the boxed region in panel A. Amino acids that change to confer quinolone resistance are indicated in black and by the amino acid numbers. Amino acid 51 is in helix 2, amino acid 67 is in helix 3, and amino acids 83 and 87 are in helix 4.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marila Gennaro, Jonathan Heddle, Anthony Maxwell, and Xilin Zhao for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by PSC-CUNY Faculty Research Award grants 66181 and 69197 to S.M.F. and by NIH grant AI35257 to K.D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachoual R, Dubreuil L, Soussy C-J, Tankovic J. Roles of gyrA mutations in resistance of clinical isolates and in vitro mutants of Bacteroides fragilis to the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1842–1845. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1842-1845.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman S M, Droffner M L, Yamamoto N. Thermotolerant nalidixic acid-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol. 1991;22:311–316. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman S M, Malik M, Drlica K. DNA supercoiling in a thermotolerant mutant of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:417–422. doi: 10.1007/BF02191641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ince D, Hooper D. Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to premafloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus: novel mutations suggest novel drug-target interactions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3344–3350. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3344-3350.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jendrisak J, Young R, Engel J. In: Guide to molecular cloning techniques. Berger S, Kimmel A, editors. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1978. pp. 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones M E, Sahm D F, Martin N, Scheuring S, Heisig P, Thornsberry C, Köhrer K, Schmitz F-J. Prevalence of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE mutations in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with decreased susceptibilities to different fluoroquinolones and originating from worldwide surveillance studies during the 1997–1998 respiratory season. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:462–466. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.462-466.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitamura A, Hoshino K, Kimura Y, Hayakawa I, Sato K. Contribution of the C-8 substituent of DU-6859a, a new potent fluoroquinolone, to its activity against DNA gyrase mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1467–1471. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu T, Zhao X, Drlica K. Gatifloxacin activity against quinolone-resistant gyrase: allele-specific enhancement of bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity by the C-8-methoxy group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2969–2974. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morais-Cabral J H, Jackson A P, Smith C V, Shikotra N, Maxwell A, Liddington R C. Crystal structure of the breakage-reunion domain of DNA gyrase. Nature. 1997;388:903–906. doi: 10.1038/42294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura S. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance. J Infect Chemother. 1997;3:128–138. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitz F-J, Fluit A, Brisse S, Verhoef J, Koher K, Milatovic D. Molecular epidemiology of quinolone resistance and comparative in vitro activities of new quinolones against European Staphylococcus aureus isolates. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sindelar G, Zhao X, Liew A, Dong Y, Zhou J, Domagala J, Drlica K. Mutant prevention concentration as a measure of fluoroquinolone potency against mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3337–3343. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3337-3343.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer M, Baker T A, Schnitzler G, Deischel S M, Goel M, Dove W, Jaacks K J, Grossman A D, Erickson J W, Gross C A. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:1–24. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.1-24.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sternglanz R, DiNardo S, Voelkel K A, Nishimura Y, Hirota Y, Becherer A K, Zumstein L, Wang J C. Mutations in the gene coding for Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I affecting transcription and transposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2747–2751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan E A, Kreiswirth B N, Palumbo L, Kapur V, Musser J M, Ebrahimzadeh A, Frieden T R. Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant tuberculosis in New York City. Lancet. 1995;345:1148–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90980-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka M, Nakayama H, Haraoka M, Saika T, Kobayashi I, Naito S. Susceptibilities of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates containing amino acid substitutions in gyrA, with or without substitutions in parC, to newer fluoroquinolones and other antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:192–195. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.192-195.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wall J D, Harriman P D. Phage P1 mutants with altered transducing abilities for Escherichia coli. Virology. 1974;59:532–544. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoo J-H, Huh D-H, Choi J-H, Shin W-S, Kang J-W, Kim C-C, Kim D J. Molecular epidemiological analysis of quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli causing bacteremia in neutropenic patients with leukemia in Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1385–1391. doi: 10.1086/516132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1271–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Xu C, Domagala J, Drlica K. DNA topoisomerase targets of the fluoroquinolones: a strategy for avoiding bacterial resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13991–13996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J-F, Dong Y, Zhao X, Lee S, Amin A, Ramaswamy S, Domagala J, Musser J M, Drlica K. Selection of antibiotic resistance: allelic diversity among fluoroquinolone-resistant mutations. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:517–525. doi: 10.1086/315708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]