Abstract

Background

Apert syndrome (AS) is a rare congenital disorder that correlates with many craniofacial features, like craniosynostosis, midfacial malformation, and symmetrical syndactyly of the hands and feet.

Aim

This paper describes the facial and oral manifestations in a 20-year-old female previously diagnosed with AS, discusses the complex dental treatment plan and treatments, including the use of a customized toothbrush handle to enhance the patient's brushing ability.

Results

A satisfactory outcome was provided, and the patients quality of life improved significantly due to this comprehensive multi-disciplinary care process.

Conclusions

Comprehensive examination, extensive medical history reviewed, parental and patient consent are needed to establish a comprehensive treatment plan regarding the special needs of these patients.

Keywords: Apert syndrome, Craniosynostosis, Dental care, Customized handle for toothbrush, Syndactyly

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Apert syndrome (AS), or acrocephalosyndactyly, is a rare congenital autosomal disorder associated with premature fusion of multiple sutures, including the coronal, sagittal, squamosal, and lambdoid sutures. It is considered one of the least common and most severe craniosynostosis syndromes,1,2 with an incidence ranging between 1/65,000 and 1/200,000 newborns, without predilection by gender.3

AS is associated with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern related to advanced paternal age, maternal infections, maternal drug consumption, and cranial inflammatory processes.4 More than 98% of cases are caused by Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGFR2) gene-specific missense mutations at chromosome 10q25-10q26.2,5,6

Apert Syndrome is usually a sporadic condition characterized by severe craniosynostosis and craniofacial anomalies. The patient typically presents with symmetry of 2nd, 3rd, and 4th digit syndactyly in hands and feet, partial or complete fusion of the skin and bones of fingers and toes with a common nail, and cervical spine premature fusion of the fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae.7,8

Severe cases of AS may lead to brain disorders such as ventriculomegaly or hydrocephalus and malformations of the corpus callosum or limbic structures. Some children, additionally, may exhibit a mild mental deficit, with an average Intelligence Quotient of 74.9

The facial, oral, and dental features of AS can be summarized as in the following Table 18,10, 11, 12, 13

Table 1.

The facial, oral, and dental features of Apert syndrome.

| Facial characteristics | Oral characteristics | Dental characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric facies. | Class III malocclusion. | Sever crowding. |

| Cone-shaped head. | Skeletal anterior open bite. | Supernumerary teeth. |

| Flat forehead and occiput. | Soft palate cleft. | Delayed dental eruption. |

| Proptosis. | Narrower dimensions of dental arches. | Dental fusion. |

| Depressed broad nose. Bulbous tip. | Bilateral posterior crossbite. | Enamel hypoplasia. |

| Deviated septum. | Hypotonic lips. | Ectopic eruption of upper first permanent molars. |

| Impaired speech. | Shovel-shaped incisors. | |

| Bifid uvula. |

Patients with AS who survive past childhood and don't have heart problems are likely to have a near-normal life expectancy due to surgical techniques and follow-up care.14

Although clinicians may make generalizations of the typical characteristics of AS, each affected child can exhibit a different presentation, requiring unique preventive and therapeutic strategies.3 Therefore, the present case report aims to present the oral and dental findings and dental care for a female patient aged 20 years with AS.

2. Patient presentation

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the first author's University (protocol code 1674 and date of approval in May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects/caregivers involved in the study.

A 20-year-old female was referred to the Department of Pediatric Dentistry for Special Needs Care at the first author's University with a chief complaint of discomfort from the appearance of the upper incisors.

The patient presented with unusual craniofacial and dental features. During the parents' interview, information revealed that the patient is the third child from a non-consanguineous marriage. The mother reported a normal delivery with no history of trauma, infection, or drug use. The patient hadn't any cardiac-related symptoms but had experienced difficulties with her respiratory system, such as shortness of breath and frequent ear infections. Although she had minimal signs of mental retardation, she is very self-conscious of her physical appearance, cooperative with everyday speech and language use. The patient has sufficient communication skills and is self-dependent in personal health care and hygiene.

-

A.All previous surgeries were done under general anesthesia and reported to have occurred in this sequence:

-

1)Cranioplasty was performed for craniosynostosis at the age of 7 months.

-

2)At the age of one year, the cleft palate was closed.

-

3)At the age of 3 years, corrective surgery for hands digit syndactyly.

-

4)At the age of 17 years, a mastoidectomy was performed.

-

5)At the age of 19 years, an operation for a Polycystic ovary was performed.

-

1)

-

B.History dental treatments are as follows:

-

1)At the age of 10, the patient had dental treatments that included extractions and restorative treatment for primary and permanent teeth.

-

2)At the age of 16, the patient had dental treatment that included extractions for three permanent teeth.

-

1)

-

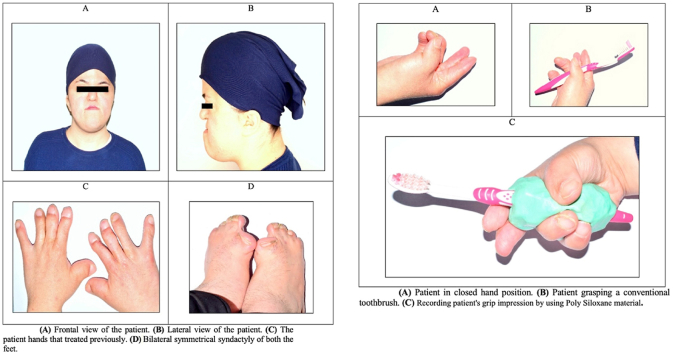

C.Extraoral clinical examination showed the patient presented with abnormal characteristics:

-

•cone-shaped head, high forehead, hydrocephalus, exophthalmos hypertelorism, low-set ears, depressed nasal bridge, midface hypoplasia with a relative mandibular prognathism (Fig. 1A and B), mouth breathing, oily skin with acne, and syndactyly of feet and hand that were treated previously (Fig. 1C and D).

-

•

-

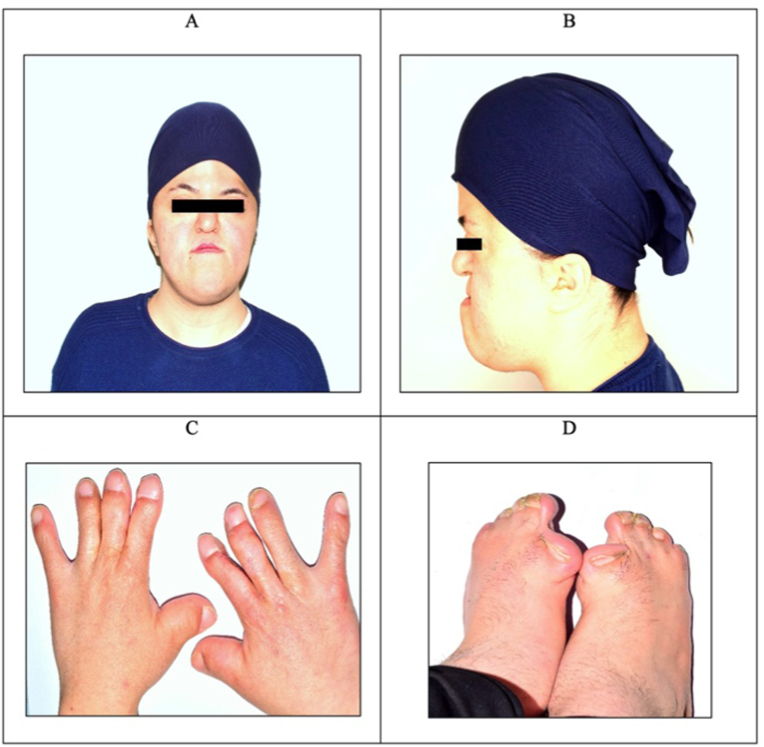

D.Intraoral clinical presentation and examination:

-

1)Oral manifestations: hypoplastic maxilla, high arched palate, hypotonic lips, skeletal anterior open bite, bilateral posterior crossbite, class III malocclusion, and generalized gingivitis with dental plaque accumulation (Fig. 2A–C).

-

2)Poor oral hygiene.

-

3)Dental manifestations were crowding, rotated upper central incisors, carious lesions on teeth # 11-21-33-43-44-45-46.

-

4)Ten teeth were clinically present in the maxillary jaw, and in the mandibular jaw was 14 teeth.

-

1)

-

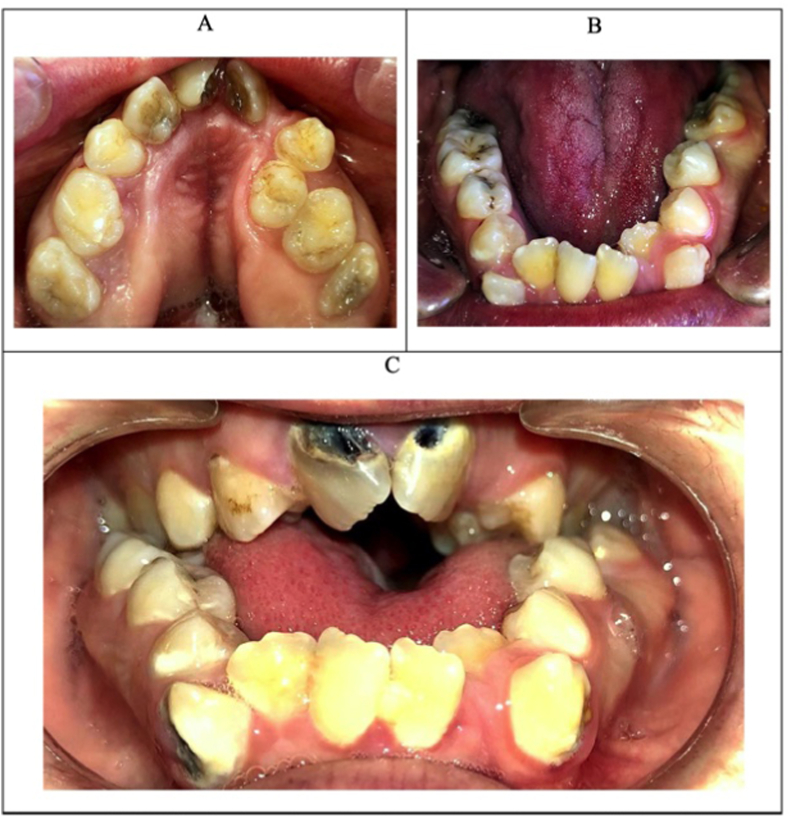

E.Radiographic examination showed:

-

1)Twelve teeth in the maxillary jaw (two impacted) and 14 teeth in the mandibular jaw.

-

2)Missing teeth #18-12-22-23-36-48.

-

3)Carious lesions on teeth # 11, 21, 33, 43, 44-45-46.

-

4)Necrotic pulp tooth # 43

-

5)Impacted teeth #14-27 (Fig. 3).

-

1)

Fig. 1.

(A) Frontal view of the patient. (B) Lateral view of the patient (C) The patient hands that treated previously. (D) Bilateral symmetrical syndactyly of both the feet.

Fig. 2.

(A) Occlusal view of maxilla. (B) Occlusal view mandibular. (C) Frontal view of both arches in occlusion.

Fig. 3.

A panoramic radiograph showing Impacted teeth # 14-27, extremely large carious lesions teeth # 11,21,33,43 and superficial carious lesion teeth # 44-45-46.

After reviewing medical history and comprehensive intraoral, extraoral, and radiographic examination, the patient was diagnosed as outlined in Table 2.

- A.comprehensive treatment plan was established, including:

-

1)Medical consultations with the patient's primary care physician.

-

2)Monitor and improve oral hygiene through oral hygiene instructions, fluoride use, and dietary education.

-

3)Caries control on teeth # 11-21-33-44-45-46.

-

4)Endodontic treatment for teeth # 11-21.

-

5)Restorative treatment on teeth # 44-45-46.

-

6)Dental extraction on teeth # 33-43.

-

7)Preventative treatments including fluoride varnish application and sealant on teeth 13-14-16-18-24-25-26-28-34-35-37-38-47.

-

8)Transfer to the orthodontic department to determine if improvement of alignment of teeth would be possible.

-

1)

Table 2.

A diagnosis and a problem list.

| Diagnosis | Problem List |

|---|---|

| Apert syndrome. | Poorly compliant parents. |

| Malocclusion. | High caries risk and poor oral hygiene. |

| Generalized gingivitis. | Special health needs. |

| Carious lesions on teeth # 11-21-33-44-45-46. | Patient has difficulties brushing her teeth. |

| Necrotic pulp tooth # 43. | Enamel demineralization. |

| Missing teeth 18-12-22-23-36-48. | Low socioeconomic status. |

| Impacted teeth #14-27. | Poor oral hygiene measured via plaque score. |

| High sugar intake measured via dietary chart. |

The detailed treatment plan was discussed with the parents, who agreed on treatment and signed an informed consent document.

3. Management

Tell-Show-Do behavioral management technique was used in all stages of treatment.

-

Step1

-

•Prophylactic treatment, including sub and supragingival scaling, prophy brush, and prophy paste for plaque removal.

-

•Oral hygiene instructions given to patient and parents included: brushing twice a day for at least 2 min each time, using fluoridated toothpaste, flossing at least once a day, and using chlorhexidine mouthwash (0.12%) as prescribed for two weeks. Parents were encouraged to supervise the patient's tooth brushing.

-

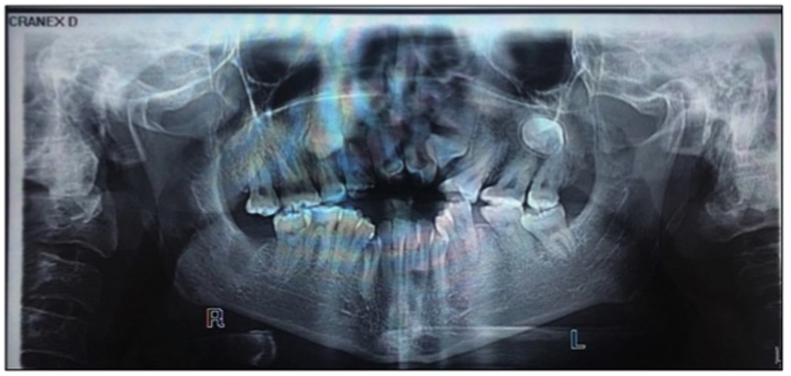

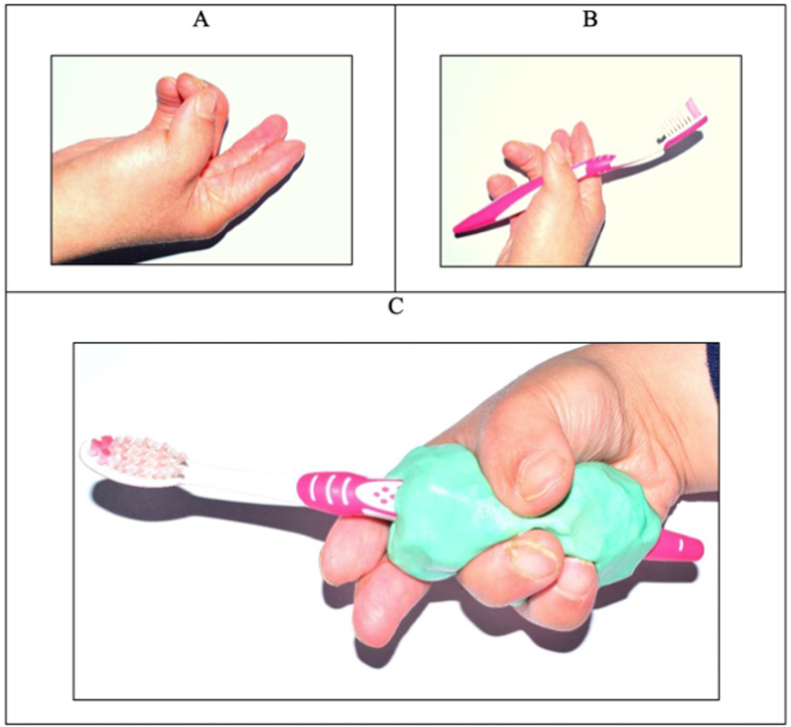

•A customized handle for the toothbrush was fabricated for the patient using an impression of her grip with polysiloxane impression material. Customization improved the patient's ability to manipulate and control the toothbrush (Fig. 4A–C).

-

•

-

Step 2

-

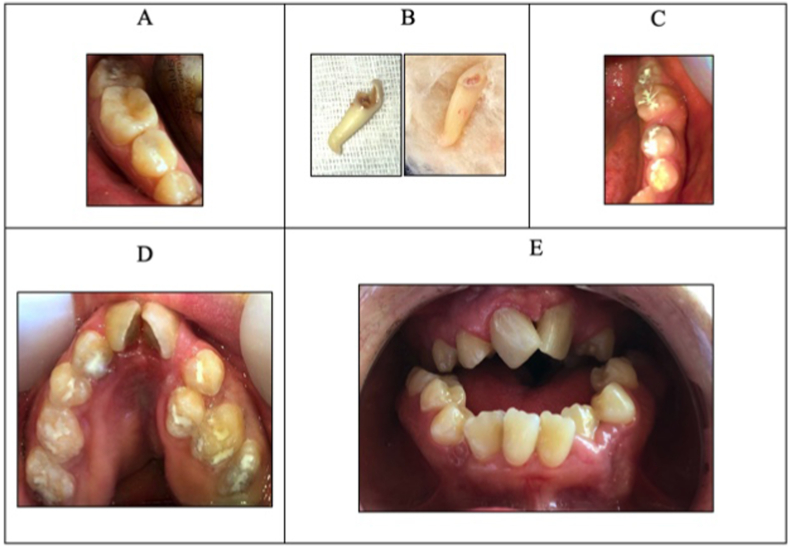

•Root canal treatment was performed on teeth # 11-21 in one visit. These teeth were then restored with direct composite restorations (Fig. 5).

-

•

-

Step 3

-

•Carious removal on teeth # 44-45-46 and restored with direct composite restorations (Fig. 6A).

-

•

-

Step 4

-

•Considering teeth # 33-43 and their questionable restorability, arch position, and after an orthodontic consult, a decision was made to extract teeth # 33-43 (Fig. 6B).

-

•

-

Step 5

-

•Fissure sealants were applied on teeth # 13-14-16-18-24-25-26-28-34-35-37- 38-47, and fluoride varnish was applied for all teeth (Fig. 6C and D).

-

•

-

Step 6

-

•After all the dental treatments were performed (Fig. 6E), oral hygiene instructions were reinforced with the patient and parents.

-

•

Fig. 4.

(A) Patient in closed hand position. (B) Patient grasping a conventional toothbrush. (C) Recording patient's grip impression by using Poly Siloxane material.

Fig. 5.

A periapical radiograph for root canal treatment teeth # 11-21.

Fig. 6.

(A) Restorative treatment on teeth # 44-45-46 and sealant applied on tooth # 47. (B) Extracted teeth # 11,21. (C-D) Sealant applied on teeth # 13-14-16-18-24-25-26-28-34-35-37-38. (E) Frontal view of restored dentition.

4. Discussion

Apert Syndrome, or type I acrocephalosyndactyly, is a rare, congenital craniosynostosis condition resulting from missense mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor 2. It is characterized by specific clinical features of midface hypoplasia and limb abnormalities (syndactyly of hands and feet).15 This case has all the classical clinical and radiological features.

Mental retardation is considered typical in patients with Apert syndrome and, in most cases, is due to high intracranial pressure. This patient had cranioplasty when she was seven months old. Early cranioplasty corrected functional consequences of craniosynostosis and resulted in minimal signs of mental retardation.15,16

Oral health is an inseparable part of general health and well-being17 because oral diseases can have a direct and indirect devastating impact on healthy individuals' health and quality of life and those with systemic health problems or conditions.18,19

Individuals with special health care needs (SHCN) may be at increased risk for oral diseases. It is essential to evaluate the patient's caries risk and incorporate preventive therapy to reduce patient risk factors. SHCN patients are considered at high-caries risk and require preventive interventions.18,19 The dental team should develop an individualized oral hygiene program and preventive strategies that consider the unique disability of the patient. To prevent caries and periodontal disease, brushing with fluoridated toothpaste for plaque removal twice per day should be emphasized to help prevent caries and periodontal disease.20

Oral examination revealed poor oral hygiene, multiple carious lesions, and generalized gingivitis in the present case. An aggressive prophylactic approach was needed, including regular mechanical and chemical professional plaque control, including fluoride and chlorhexidine applications, which is considered to be essential.10

In the present case, all at-risk pits and fissures were sealed with a resin sealant. Patients with SHCN can benefit from sealants. Sealants reduce the risk of caries in susceptible pits and fissures of primary and permanent teeth.20

Orthodontic treatment at an early age is recommended for patients with AS1,15 because of the high incidence of patients with orthodontic anomalies, mal-occlusion, maxillary hypoplasia, and severe crowding. All of the above symptoms were present in this patient. However, the parents showed no interest in pursuing orthodontic treatment. The major problem for patients with AS is the syndactyly of hands and feet.

Syndactyly causes immobility of fingers. Although, in this case, the patient had received treatment for the hand syndactyly when she was three years old, the patient still could not move her index and middle fingers in both hands. Customizing toothbrushes handles can help patients with restricted hand and finger movement.21 Armed with this information, a customized handle toothbrush was made to help overcome the hand syndrome, enable the patient to hold the toothbrush, and improve her ability to brush.

5. Conclusion

To establish a diagnosis and comprehensive treatment plan that will fit patient needs, the dentist and dental team should fully understand any abnormalities and disorders correlated with their patients. In this case, the team obtained complete extraoral and intraoral examination, extensive medical history reviewed, parents interviewed, and consults to establish a comprehensive treatment plan. The care was provided to the patient in a pediatric dental operatory due to the patients’ special needs, and the patient was cooperative with behavioral management techniques.

Importance of this paper to dentists

-

•

Discusses the unique issues associated with Apert Syndrome (AS) patients.

-

•

Explore the multi-disciplinary needs for rendering care for patients with AS.

-

•

Describes a way to improve home care opportunities working with the issue of syndactyly of hands and feet.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the first author's University (protocol code 1674 and date of approval in May 2020).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects/caregivers involved in the study.

Data availability statement

The study did not report any numerical data in the current case report.

Author contributions

L.D.: conceptualization, design, study conduction, drafting manuscript. M.L.: conceptualization, study conduction, drafting manuscript.

Y.A.T.: study conduction, critical revision of manuscript, supervision. J.C.: critical revision and finalization of manuscript.

All authors have read and agreed to published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The parents signed written consent forms to allow their patient's case to be published.

Contributor Information

Line Droubi, Email: droubiline@gmail.com.

Mohannad Laflouf, Email: dr.laflouf@hotmail.com.

Yasser Alsayed Tolibah, Email: Firedragoon1994@hotmail.com.

John C. Comisi, Email: comisi@musc.edu.

References

- 1.Bhatia P.V., Patel P.S., Jani Y.V., Soni N.C. Apert's syndrome: report of a rare case. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol: JOMFP. 2013;17(2):294. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.119782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu C., Cui Y., Luan J., Zhou X., Han J. The molecular and cellular basis of Apert syndrome. Intract Rare Dis Res. 2013;2(4):115–122. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2013.v2.4.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surman T., Logan R., Townsend G., Anderson P. Oral features in Apert syndrome: a histological investigation. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2010;13(1):61–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2009.01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sannomiya E.K., Reis S., Asaumi J., Silva J., Barbara A., Kishi K. Clinical and radiographic presentation and preparation of the prototyping model for pre-surgical planning in Apert's syndrome. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2006;35(2):119–124. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/77056158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibarra-Arce A., de Zárate-Alarcón G.O., Flores-Peña L., Martínez-Hernández F., Romero- Valdovinos M., Olivo-Díaz A. Mutations in the FGFR2 gene in Mexican patients with Apert syndrome. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(1):2341–2346. doi: 10.4238/2015.March.27.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres L., Hernández G., Barrera A., Ospina S., Prada R. Molecular analysis of exons 8, 9 and 10 of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene in two families with index cases of Apert Syndrome. Colomb Méd. 2015;46(3):150–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixit S., Singh A., Mamatha G., Desai R.S., Jaju P. Apert's syndrome: report of a new case and its management. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2008;1(1):48. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behrman R.E., Kliegman R., Schor N.F., et al. 2020. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalben G.d.S., Neves L.T.d., Gomide M.R. Oral findings in patients with Apert syndrome. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006;14(6):465–469. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572006000600014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Şoancă A., Dudea D., Gocan H., Roman A., Culic B. Oral manifestations in Apert syndrome: case presentation and a brief review of the literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2010;51(3):581–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendiola S.E.C., Martínez I.O.P., Saavedra Á.E.M., Contreras J.T., Hernández A.L.G. Clinical applications of molecular basis for craniosynostosis: a narrative review. J Oral Res. 2016;5(3):124–134. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpentier S., Schoenaers J., Carels C., Verdonck A. Cranio-maxillofacial, orthodontic and dental treatment in three patients with Apert syndrome. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15(4):281–289. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Letra A., de Almeida A.L.P.F., Kaizer R., Esper L.A., Sgarbosa S., Granjeiro J.M. Intraoral features of Apert's syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(5):e38–e41. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkie A.O., Bochukova E.G., Hansen R.M., et al. Clinical dividends from the molecular genetic diagnosis of craniosynostosis. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140(23):2631–2639. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Estudillo A.S., Rosales-Berber M.A., Ruiz-Rodriguez S., Pozos-Guillen A., Noyola- Frias M.A., Garrocho-Rangel A. Dental approach for Apert syndrome in children: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22(6):e660–e668. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan S., Chatra L., Shenai P., Veena K. Apert syndrome: a case report. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2012;5(3):203–206. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Symposium on lifetime oral health care for patients with special needs. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29(2):92–152. [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; Rockville, Md: 2000. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thikkurissy S., Lal S. Oral health burden in children with systemic disease. Dent Clin. 2009;53(2):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.12.004. xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Definition of special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38(special issue):16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeson M.G., Jepson N.J. Customizing the size of toothbrush handles for patients with restricted hand and finger movement. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87(6):700. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.120840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not report any numerical data in the current case report.