Abstract

Protein sorting at the trans Golgi network (TGN) usually requires the assistance of cargo adaptors. However, it remains to be examined how the same complex can mediate both the export and retention of different proteins or how sorting complexes interact among themselves. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the exomer complex is involved in the polarized transport of some proteins from the TGN to the plasma membrane (PM). Intriguingly, exomer and its cargos also show a sort of functional relationship with TGN clathrin adaptors that is still unsolved. Here, using a wide range of techniques, including time-lapse and BIFC microscopy, we describe new molecular implications of the exomer complex in protein sorting and address its different layers of functional interaction with clathrin adaptor complexes. Exomer mutants show impaired amino acid uptake because it facilitates not only the polarized delivery of amino acid permeases to the PM but also participates in their endosomal traffic. We propose a model for exomer where it modulates the recruitment of TGN clathrin adaptors directly or indirectly through Arf1 function. Moreover, we describe an in vivo competitive relationship between the exomer and AP-1 complexes for the model cargo Chs3. These results highlight a broad role for exomer in regulating protein sorting at the TGN that is complementary to its role as cargo adaptor and present a model to understand the complexity of TGN protein sorting.

INTRODUCTION

The trans Golgi network (TGN) is a major intracellular cargo sorting station, where newly synthesized proteins and endocytosed proteins need to be accurately identified and sorted to distinct subcellular destinations (1). Cells utilize sophisticated cargo sorting machineries to meticulously package the cargo molecules into the right transport carriers (1). During this process, cargo adaptors often play pivotal roles in both cargo recognition and in coat assembly (2, 3), while coat assembly ultimately leads to membrane deformation and fission (4). One critical coat at the TGN is the clathrin coat, which generates clathrin-coated vesicles (CCV). Although it is clear that in most eukaryotes the clathrin adaptor complex-1 (AP-1) plays a critical role in TGN sorting, growing evidence suggests it may play a role in both export and retention, moreover AP-1 shows genetic interaction with several other sorting complexes suggesting communication between complexes may help maintain the protein sorting function (2, 3). CCV assembly has been extensively analyzed in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5). In this yeast, several clathrin adaptors are sequentially recruited to TGN membranes through a coordinated mechanism that depends on PtdIns(4)P and the Arf1 GTPase (3). The adaptor complex GGA is first recruited, followed by AP-1. Deletion of Gga2 alters the dynamics of the recruitment of AP-1. By contrast, AP-1 has minor mechanistic effects in the assembly of the other clathrin adaptor complexes (6). Clathrin and its adaptor complexes have a general role in the regulation of the traffic of multiple proteins to the pre-vacuolar compartment (PVC) facilitating their recycling back to the TGN. Accordingly, the involvement of these complexes in the late endosomal traffic of multiple amino acid transporters has been described (7–10). Recycling from the PVC has been well characterized for TGN resident proteins like Kex2, Vps10 and Tlg1 (11–13). However, a role for clathrin in the formation of a distinct subset of secretory vesicles has also been reported (14), but the nature of these vesicles and their cargos has remained elusive.

The function of clathrin and its adaptors in the anterograde traffic from the TGN to PM is poorly understood, yet another sorting complex, exomer, has a more established role in this TGN to PM traffic. The exomer complex is a cargo adaptor required for the delivery of three cargoes to the PM, the major chitin synthase, Chs3, (15–17), Fus1 (18), and Pin2 (19), all three integral transmembrane proteins. Exomer consists of a tetramer formed by a dimer of the scaffold protein Chs5 and two accessory proteins (20) that are encoded by four different genes: the paralogous BCH1 / BUD7 and CHS6 / BCH2 gene pairs (17, 21). Together these four proteins are called the ChAPs (Chs5-Arf1 binding proteins). The ChAPs are thought to bind directly to cargos, Arf1, and membranes thereby acting as the cargo recognition face of the complex. The current view is that any two of the four ChAPs can be incorporated into the exomer complexes, providing different functionalities (21–23). For example, only an exomer containing the Chs6 ChAP is able to mediate the traffic of Chs3 to the PM (17, 21, 24), because Chs3 interacts physically with the exomer through the Chs6 ChAP (24–26). In contrast, the Bch1 Bud7 paralogous proteins appear to interact directly with the TGN membrane to favor the membrane curvature required for vesicle formation (22).

Interestingly, all known exomer cargos are also subject to AP-1-mediated traffic (18, 19, 27). This was first reported for Chs3, where deletion of the AP-1 complex restores Chs3 PM localization in cells lacking exomer (25, 27). This restoration is thought to indicate a role for clathrin and AP-1 in the retention of Chs3 at the TGN (27), which allows the exomer to deliver Chs3 to the PM in a cell cycle or stress-regulated manner (28). The mechanistic relationship between exomer and AP-1 complexes in this retention mechanism is unclear. In addition, exomer is well conserved in other fungi (21, 29), and it has been recently reported that the Schizosaccharomyces pombe exomer interacts functionally with clathrin adaptors as a means to maintain the integrity of diverse cellular compartments (30). Taken together, these results, reported in several organisms, highlight the potential multiple levels of interaction among exomer and other TGN complexes in order to facilitate protein traffic.

In this work, we explored additional roles for exomer in protein traffic and its unsolved relationship with TGN clathrin adaptors using multiple aproaches. We show that exomer not only facilitates the anterograde traffic of several integral PM proteins from the TGN, but also plays a general role in protein traffic by modulating the assembly of TGN clathrin adaptors thus regulating proper traffic from the TGN to the PVC. Finally, we conclude that exomer maintains different associations with cargos and clathrin adaptors, which differ along fungal lineage.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Yeast strains construction.

The yeasts strains used throughout this work were made in the W303, BY4741 or X2180 genetic backgrounds as indicated in the Table 1. Cells were transformed using lithium acetate/ polyethylene glycol procedure (31). Gene deletions were made using a PCR-mediated gene replacement technique, using different deletion cassettes based on the natMX4, kanMX4, or hphNT1 resistance genes (32). For the insertion of the GAL1 promoter in front of ORFs, the cassette was amplified from pFA6a-kanMX4::pGAL1 (33) (Table 2). Proteins were tagged chromosomally at their C-terminus with 3xHA, GFP, mCherry and Venus CT or NT fragments, employing integrative cassettes amplified from pFA6a-3xHA::hphMx6/ pFA6a-GFP::hphMx6/ pFA6a-GFP::natMx4/ pFN21/ pFA6a-VN::HIS3Mx6/ pFA6a-VC::kanMX6 (34). The Delitto Perfetto technique was performed to generate the internal gene modifications within the genome. In brief, this approach allows for in vivo mutagenesis using two rounds of homologous recombination. The first step involves the insertion of a cassette containing two markers at or near the locus to be altered and the second involves complete removal of the cassette and transfer of the expected genetic modification to the chosen DNA locus as previously described (35).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used.

| Strain | Genotype | Origin / Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae strains | ||

| CRM67 | W303, mat a, (leu2-3,112 trp1-1 can1-100 ura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11,15) | Lab. collection |

| CRM2268 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM3066 | W303, mat a, bch1 Δ::kanMx4 bud7Δ::natMx4 | (42) |

| CRM3081 | W303, mat a, chs6Δ::kanMx4 bch2Δ::natMx4 | (42) |

| CRM3851 | W303, mat a, tat2Δ::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3853 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 tat2Δ::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3909 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-TAT2::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3917 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 PGAL1-TAT2::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM2868 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-GFP-SSY1::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM2871 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 PGAL1-GFP-SSY1 ::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3811 | W303, mat a, STP1-3xHA::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3825 | W303, mat a, STP1-3xHA::hphNT1 chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3813 | W303, mat a, GLN3-3xHa::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3827 | W303, mat a, GLN3-3XHΔ::hphNT1 chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3023 | W303, mat a, GTR1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3032 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 GTR1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3017 | W303, mat a, TCO89-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3020 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 TCO89-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM2972 | W303, mat a, GAP1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM2979 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 GAP1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM2894 | W303, mat a, TAT2-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM2903 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 TAT2-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3531 | W303, mat a, MUP1-GFP::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3540 | W303, mat a, MUP1-GFP::KanMx4 chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3882 | W303, mat a, TAT252-53-3xHA (internal by Delitto Perfetto) | This study |

| CRM3890 | W303, mat a, TAT252-53-3xHA chs5Δ:: kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3862 | W303, mat a, bul1Δ:: kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3903 | W303, mat a, bul2Δ:: hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3880 | W303, mat a, bul1Δ:: kanMx4 bul2Δ:: hphNTl | This study |

| CRM3864 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ:: kanMx4 bul1Δ:: kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3950 | W303 mat a, gga2Δ:: hphNT1 chs5Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3526 | W303 mat a, rcy1Δ:: kanMx4 gga1A:: natMx4 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM3602 | W303 mat a, rcy1Δ:: kanMx4 gga2Δ:: hphNT1 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM4025 | W303 mat a, rcy1Δ:: kanMx4 aps1Δ:: hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3432 | W303 mat a, APL4-VC::kanMx4 CHS5-VN::HIS3 | This study |

| CRM3477 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3997 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VN::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4003 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VN::kanMx4 MUP1-VC::HIS3 | This study |

| CRM4070 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VN::kanMx4 GGA2-VC::HIS3 | This study |

| CRM2879 | W303 mat a, SEC7-mRuby2::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM2882 | W303 mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 SEC7-mRuby2::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4088 | W303 mat a, arf1Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4090 | W303 mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 arf1Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM1278 | W303 mat a, chs3A:: URA3 chs5Δ:: natMx4 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM1590 | W303 mat a, chs3A:: natMx4 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM3089 | W303, mat a, bch1Δ::kanMx4 bud7Δ:: natMx4 chs3Δ::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3091 | W303 mat a, chs6Δ::kanMx4 bch2Δ:: natMx4 chs3Δ::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4098 | W303 mat a, chs3Δ:: URA3 chs6Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3534 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 gga2Δ:: hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3511 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 chs6Δ:: natMx4 bch2A::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3668 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 bch1Δ:: hphNT1 bud7A:: natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3641 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 chs7Δ:: hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3674 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 chs3Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| CRM3511 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 chs6Δ:: natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3676 | W303 mat a, CHS5-VC::kanMx4 chs6Δ:: natMx4 chs3Δ:: URA3 | This study |

| CRM3432 | W303 mat a, APL4-VC::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3453 | W303 mat a, APL4-VC::kanMx4 gga2Δ:: hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM3436 | W303 mat a, chs3Δ::URA3 APL4-VC::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM2248 | W303, mat a, CHS5-mCherry::natMx4 APS1-GFP:: hphNT1 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM2533 | W303, mat a, CHS5-mCherry::natMx4 GGA1-GFP:: hphNT1 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM808 | BY4741, mat a (his3A1, leu2A0, met15A0, ura3A0) | EUROSCARF |

| CRM1435 | BY4741, mat a, chs3Δ::natMx4 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM2453 | BY4741, mat a, chs3Δ::natMx4 chs5Δ::hphNT1 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM3922 | BY4741, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM3924 | BY4741, mat a, art1Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3926 | BY4741, mat a, art2Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3928 | BY4741, mat a, art3Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3930 | BY4741, mat a, art4Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3932 | BY4741, mat a, art5Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3934 | BY4741, mat a, art6Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3935 | BY4741, mat a, art7Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3937 | BY4741, mat a, art8Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3939 | BY4741, mat a, art9Δ::kanMx4chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3941 | BY4741, mat a, art10Δ::kanMx4 chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM4019 | BY4741, mat a, GGA2-GFP::hphNT1 APL4-mCherry:: natMx4 | This study |

| CRM2761 | X2180-1A, mat a (SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1) | Francisco del Rey |

| CRM2763 | X2180-1A, mat a, chs5Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3957 | X2180-1A, mat a, tat2Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM3959 | X2180-1A, mat a, chs5Δ::kanMx4 tat2Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM2783 | X2180-1A, mat a, ssy1Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM3010 | X2180-1A, mat a, ssy1Δ::natMx4 chs5Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4311 | W303, mat a, ARF1-GFP: :hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4134 | W303, mat a, CHS3-2xGFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4136 | W303, mat a, CHS3-2xGFP::hphNT1 chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM4140 | W303, mat a, CHS3-2xGFP::hphNT1 arf1Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4138 | W303, mat a, CHS3-2xGFP::hphNT1 chs5Δ::natMx4 arf1Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4157 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-ARF1::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4159 | W303, mat a, chs5Δ::natMx4 PGAL1-ARF1::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4302 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-SEC7::KanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4339 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-SEC7::KanMx4 chs5Δ::natMx4 | This study |

| CRM2818 | BY4741, mat a, CHS5-GFP::hphNT1 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM4160 | BY4741, mat a, CHS5-GFP::hphNT1 arf1Δ::kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4594 | W303, mat a, CHS5-VN::kanMx4 ANP1-VC::HIS3 | This study |

| CRM4586 | W303, mat a, CHS5-mCherry::natMx4 GGA1-GFP::hphNT1 arf1Δ:: kanMx4 | This study |

| CRM4584 | W303, mat a, CHS5-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4573 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-GGA2::KanMx4 CHS5-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4118 | W303, mat a, APS1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4153 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-GGA2::KanMx4 APS1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4571 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-BUD7::KanMx4 APS1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| CRM4576 | W303, mat a, PGAL1-BCH1::KanMx4 APS1-GFP::hphNT1 | This study |

| C. albicans strains | ||

| CRM2499 | BWP17, (ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 his1 ::hisG/his1::hisG arg4: :hisG/arg4::hisG) | (75) |

| CRM2531 | BWP17, Cachs5Δ::ARG4/Cachs5Δ::HIS1 | Lab. Collection |

| CRM3258 | BWP17, Caaps1Δ::SAT1/Caaps1 Δ::URA3 | This study |

| CRM3261 | BWP17, Cachs5Δ::ARG4/Cachs5Δ::HIS1 Caaps1Δ::SAT1/Caaps1Δ::URA3 | This study |

Table 2.

Plasmids used.

| Plasmid | Genotype | Origin / Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CRM160 | pRS313 (HIS3) | Lab collection |

| CRM161 | pRS314 (TRP1) | Lab collection |

| CRM264 | pRS315 (LEU2) | Lab collection |

| CRM265 | pRS316 (URA3) | Lab collection |

| CRM166 | pRS426 (URA3) | Lab collection |

| CRM2546 | pAG25 (natMx4) | (32) |

| CRM1188 | pUG6 (kanMx4) | (32) |

| CRM2546 | pUG72 (URA3) | (32) |

| CRM1451 | pFA6a-hphNT1 | (32) |

| CRM1807 | pFA6a-3xHΔ::hphNT1 | (34) |

| CRM1995 | pFA6a-GFP::hphNT1 | (34) |

| CRM1811 | pFA6a-GFP::natMx4 | (34) |

| CRM2653 | pFN21 (mCherry::natMx4) | (34) |

| CRM2037 | pFA6a-kanMX4-pGAL1 | (33) |

| CRM2827 | pFA6a-kanMX4-pGAL1-GFP | (33) |

| CRM2360 | pGSHU (CORE Delitto Perfetto) | (35) |

| CRM3469 | pFA6a-VenusCterminal::HIS3 | (39) |

| CRM3470 | pFA6a-VenusNterminal::HIS3 | (39) |

| CRM3471 | pFA6a-VenusCterminal:: kanMX4 | (39) |

| CRM3472 | pFA6a-VenusNterminal:: kanMX4 | (39) |

| CRM2328 | pFA6a- link-yomRuby2::CaURA3 | (76) |

| CRM1131 | pRS315::CHS3-GFP | (77) |

| CRM3456 | pRS315::CHS3-VN::HIS3 | This study |

| CRM2084 | pRS315::CHS3L24A-GFP | (78) |

| CRM1868 | pRS315-GFP-Snc1 | Anne Spang |

| CRM3236 | pFA-CaHIS1 | (79) |

| CRM3238 | pFA-CaARG4 | (79) |

| CRM3240 | pFA-CaURA3 | (79) |

| CRM2583 | pFA-GFP-SAT1 | (80) |

Construction of TAT252-53-3xHA. To obtain a fully functional tagged version of Tat2, we generated a chromosomally internally-tagged version of Tat2 in a region suitable for causing less reduced interference in Tat2 function, regulation and transport (between amino acids 52-53) using the Delitto Perfetto technique. Contrary to the GFP versions, this HA tagged protein fully complemented the tat2∆-associated phenotypes, and importantly, had no effect on the chs5∆ requirement for external tryptophan. For microscopic localization we used a GFP C-terminus tagged version of the protein. This protein is functional based on the complementation of the tat2∆ mutant, but showed a reduced rate of endocytosis (36).

The C. albicans mutants were generated as previously described (29).

Media and growth assays.

Yeast cells were grown at 28ºC in YEPD (1 % Bacto yeast extract, 2 % peptone, 2 % glucose), in SD medium (2 % glucose, 0.7 % Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids) or SD-N (2 % glucose, 0.16 % Difco yeast nitrogen base without ammonium and amino acids) supplemented with the pertinent amino acids and 2 % agar in the case of solid media. Calcofluor white (CW) sensitivity was always tested on YEPD or SD medium buffered with 50 mM potassium phthalate at pH 6.2 as described (37).

C. albicans media.

LEE (2 % agar, 0.5 % (NH4)2SO4, 0.25 % K2HPO4, 0.02 % MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 % NaCl, 0.05 % proline, 1.25 % glucose), LEE NAGA (LEE w/o glucose + 1.25 % N-Acetylglucosamine), LEE SERUM (LEE + 4 % fetal bovine serum) and M199 (M199 [Gibco BRL], 2 % agar, 80 mg/L uridine).

Drop tests.

To assess the growth phenotypes, cells of each tested strain from early logarithmic cultures were resuspended in water and adjusted to an OD600 of 1.0. Ten-fold serial dilutions were prepared and drops were spotted onto the appropriate agar plates containing media supplemented as indicated. Plates were incubated at 28ºC for 2–5 days.

Quantification of half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50).

Sensitivity to myriocin and sertraline was analyzed in liquid YEPD media by growing strains in a 96-well plate with different drug concentrations and measuring the OD600 using a Spectra Max 340PC plate reader as described in (38).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Yeast cells expressing GFP/ mCherry/ Venus tagged proteins were grown to early logarithmic phase in SD medium supplemented with 0.2 % adenine. Living cells were visualized directly by fluorescence microscopy. The bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BIFC) technique was used to analyze proximity among different proteins in vivo (39). For CW staining, 50 μg/ml CW was directly added to the fresh cells growing in YEPD and the cultures were incubated at 28ºC for 1h before images were taken (40).

For non-quantitative purposes, images were routinely obtained using a Nikon 90i Epifluorescence microscope (x100 objective; NA: 1.45) equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA ER digital camera, specific Chroma filters (49000 ET-DAPI, 49002 ET-GFP, 49003 ET-YFP, 49005 ET-DsRed) and controlled by Metamorph software. Images for quantitative purposes, such as co-localization, particle description or stream time-lapse of TGN-tagged proteins were acquired in a Spinning Disk confocal microscope (Olympus IX81 with Roper technology) with an Evolve EMCCD camera, 100X/1.40 Plan Apo lens, 488nm / 561nm lasers, 525/45 – 609/54 Semrock emission filters and controlled by Metamorph 7.7 software.

Protein extracts and immunoblotting.

The trichloroacetic acid (TCA) protocol was used for protein processing for the Western blot analyses. Extracts were made using an equal numbers of cells from logarithmic growing cultures. Cells were centrifuged, resuspended in 20 % TCA, and frozen at −80ºC for at least 3 hours. The samples were then thawed on ice and the centrifuged cells were disrupted in 1.5 ml tubes with 100 μl of 20 % TCA and glass beads (0.45 mm, SIGMA), during 3 pulses of 30 seconds with an intensity of 5.5 in a Fast prep (FP120, BIO101). Extracts were transferred to new tubes and 5% TCA was added to dilute TCA concentration to 10 %. Precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 900xg for 10 min and the supernatant was completely discarded. Pelleted proteins were resuspended in 50 μl of 2x Sample Buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 4 % SDS, 20 % glycerol, 25 mM DTT and traces of bromophenol blue) by vortexing, followed by the addition of 50μl of 2 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5. Samples were maintained on ice throughout this process. Finally, the extracts were heated to 37ºC for 30 min (for multipass transmembrane proteins) or 95ºC for 5 min (for other proteins) and centrifuged for 5 min at 15000xg. The supernatant was collected and 15μl were used for Western blot analysis.

Extracts were separated on 7.5 % SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (37). The membranes were then blocked with TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) supplemented with 3 % non-fat dry milk for 1 hour and incubated with the corresponding antibodies in TBST with 3 % milk for 2 h at room temperature (RT) or overnight (O/N) at 4ºC: anti-GFP JL-8 monoclonal antibody (Living colors, Clontech), anti-HA 12CA5 (Roche), anti-tubulin (T5162 Sigma). The blots were developed using anti-Rsp6-P (Cell SignalingTech: Phospho-Ser/Thr Akt Substrate Antibody #9611s) and 5 % BSA replaced the non-fat dry milk in all steps. After 3 washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated for 50 min together with the secondary antibodies in TBST with 3 % milk: polyclonal anti-Mouse or anti-Rabbit conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. After 3 washes with TBST, the blots were developed using the ECL kit (Advansta).

Subcellular fractionation by centrifugation in a sucrose gradient.

For subcellular fractionations, 50 ml of culture with an OD600 of 0.8–1 were collected and NaN3 and NaF were added up to a final concentration of 20 mM. The cultures were centrifuged at 4ºC at 4000xrpm for 4 min, resuspended with ice-cold water in 1.5 ml tubes, centrifuged at 6000xrpm for 2 min and resuspended in 1 ml of Azida Buffer (10 mM DTT, 20 mM NaN3, 20 mM NaF, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 9.4). After a 10-minute incubation step at RT, the samples were centrifuged at 6000xrpm for 2 min and resuspended in 600 μl of Spheroplast Buffer (1 M sorbitol, 20 mM NaN3, 20 mM NaF, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 in YEPD medium). Afterwards, 60 μl of zymolyase (100T, unfiltered, 4.76 mg/ml) were added and incubated at 30ºC during 30–40 min under gentle mixing until spheroplasts were produced based on microscopic analysis. The spheroplast samples were then washed twice with spheroplast buffer and collected by 500xg centrifugation for 4 min at 4ºC. The washed spheroplasts were incubated with 300 μl Lysis Buffer (10 % sucrose, protease inhibitors, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5) and incubated 10 min at RT with gradual pipetting (6-8 times). Lysis was microscopically assessed. Then, cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 500xg for 4min at 4ºC, the supernatants were collected and 250 μl of the supernatants were layered on the top of a mini-step sucrose gradient (EDTA 5 mM, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5) made as follows: 300 μl 55%, 750 μl 45%, 500 μl 41%, 300 μl 37%, 250 μl 29%. The gradients were centrifuged at 200,000xg for 3.5 h at 4ºC (Beckman Coulter L-80 XP, SW 55 Ti rotor) and 7 fractions of 300 μl were manually collected from the top of the gradient. Finally, 100 μl of each fraction were denatured in the sample buffer plus 1 % SDS for 30 min at 37ºC.

Tryptophan uptake assay.

Tryptophan was measured adapting protocols previously described (36, 41). Specifically, cells were grown to early log phase in 50 mL of SD medium (without Trp) at 30°C until an OD600 of 0.4–0.8. Then, the cells were washed twice with wash buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, pH 4.5, and 20 mM (NH4)2SO4) and resuspended in 3.6 ml of incubation medium (10 mM sodium citrate, pH 4.5, 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 2 % glucose). The absorbance at 600 nm was measured to refer values to cell number. The assay was initiated by the addition of 400 μl of radiolabeled tryptophan solution (390 μl of the incubation medium and 10 μl of L-[5-3H]-tryptophan at 31 Ci/mmol GE healthcare, UK). Two aliquots (500 μl) were collected at each time point and chilled by the addition of 1 ml of the ice-cold incubation medium. Cells were collected by filtration through a nitrocellulose filter (0.45 μm pore size, 25 mm diameter [Millipore HAWP]) and washed three times with chilled water. Moist filters were transferred to Filter Count solution (Perkin Elmer, USA). Radioactivity was measured using a Tri-Carb® 4910 TR liquid scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer, USA).

Digital quantification, statistics and figure design.

Microscopy and Western blot image processing and quantification were performed using ImageJ-FIJI software (1.48k version, NIH). For quantification of dot co-localization, pre-filtering with a custom built ImageJ Macro (Macro1, see Table 3) was used followed by the analysis of the co-localization using the JACoP ImageJ plugin (co-localization based on centers of mass-particles coincidence, particle size 4−∞ pixels). For the particle descriptors (intensity and area), ROIs were selected using a custom built Macro (Macro2, see Table 3), applying the same intensity threshold per-experiment and loaded to ROIManager with AnalyzeParticles (0.07−∞ μm2, exclude on edges). In the case of Chs3-GFP TGN-EE structures, due to the difficulty of the segmentation, dots were selected manually for maximum intensity and maximum diameter quantification. A more detailed description of the macros used is presented in the supplementary materials.

Table 3.

ImageJ Macros used:

| Macrol: Pre-filtering for dot co-localization |

|---|

| showMessage(“Open Channel Red”); //Select Channel Red |

| open(); |

| red = getTitle(); |

| showMessage(“Open Channel GFP“); //Select Channel GFP |

| open(); |

| gfp = getTitle(); //Then, we are going to filter both channels |

| selectWindow(gfp); |

| run(“Median…”, “radius=1 stack”); //Filtering |

| run(“Unsharp Mask…”, “radius=2 mask=0.5 stack”); //Filtering |

| selectWindow(red); |

| run(“Median…”, “radius=1 stack”); //Filtering |

| run(“Unsharp Mask…”, “radius=2 mask=0.5 stack”); //Filtering |

| run(“JACoP ”); //Open JACoP plugin |

| Macro2: Analyze dots |

|

|

| showMessage(“Open the Image”); //Select image |

| open(); |

| run(“Duplicate…”, “ ”); //We want to do the segmentation in a copy of the original, therefore we duplicate |

| run(“Median…”, “radius=1”); //Filtering |

| run(“Unsharp Mask…”, “radius=2 mask=0.50”); //Filtering |

| run(“Threshold…”); // to open the threshold window if not opened yet |

| waitForUser(“Set the threshold and press OK, or cancel to exit macro”); // pauses the execution and lets you access ImageJ manually |

| run(“Analyze Particles…”); //to take the ROIs |

| waitForUser(“Finally, use these ROIs in the original window”); //A note to correctly continue after the macro |

| Macro3: Counting colonies |

|

|

| showMessage(“Open the Image”); //Select image with colonies |

| open(); |

| rename(“Initial”); |

| run(“Duplicate…”, “ ”); |

| run(“Threshold…”); // to open the threshold window if not opened yet |

| waitForUser(“set the threshold and press OK, or cancel to exit macro”); // pauses the execution and lets you access ImageJ manually as long as you donť press OK, which resumes the macro execution |

| run(“Convert to Mask”); // to binarize, if you use this command, donť press ‘Apply’ in the threshold window |

| run(“Watershed”); //to separate close colonies |

| rename(“Mask”); |

| waitForUser(“Calibration: Draw a line along the Petri dish \nand introduce the known size in Analize/SetScale, then press OK”); |

| run(“Threshold…”); |

| waitForUser(“Set the threshold and press OK, or cancel to exit macro”); // pauses the execution and lets you access ImageJ manually |

| run(“Analyze Particles…”); //to take the ROIs |

For the quick time-lapse experiments, continuous images were acquired through the streaming mode on a Spinning Disk microscope in 3 z-planes separated by 0.2 μm to avoid loss of the highly dynamic TGN-structures in z-axis and to partially reduce photo-bleaching. Z-maximum intensity projections were analyzed manually or with the TrackMate ImageJ plugin. For the Sec7-mR2 structures, tracking was done using the TrackMate ImageJ plugin (LoG detector, Diameter 0.5 μm, Threshold 80, Median filter, Sub-pixel loc.; LAP Tracker; Frame to Frame 0.5 μm, No Gap, Split 0.5μM, Merge 0.5 μm, tracks with ≥ 5 spots). The analysis was performed only on tracks that initiated and completed during the collection. For analyzing the recruitment of the exomer and clathrin adaptor complexes, images were taken of strains expressing CHS5-mCh/GGA1-GFP and CHS5-mCh/APS1-GFP. Afterwards, only the trajectories of structures showing both signals (mCh/GFP), present for ≥10 s, were selected manually or with the help of TrackMate (LoG detector, Diameter 1 μm, Threshold 15–30, Median filter, Sub-pixel loc.; LAP Tracker; Frame to Frame 0.5 μm, No Gap, No Split, No Merge, Duration ≥ 8s) and the Extract track stack option (half of vesicles extracted from each channels). The average recruitment duration (temporal region with intensity ≥ 25 % of the maximum intensity per channel), as well as the temporal distance between maximum intensity peaks referring to Chs5-mCh for 30 trajectories, were manually calculated.

To obtain an unbiased measurement of the cellular polarization of PM proteins, the daughter/mother plasma membrane signal coefficient (polarization coefficient) of single cells was determined as described (42).

Image measurements were statistically analyzed using the T-test for unpaired data in GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, USA). Significantly different values (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001) are indicated (*, **, ***, ****).

The presented images were prepared using Adobe Photoshop CS5 and Adobe Illustrator CS5 (San José, CA, USA) software. All images shown in each series were acquired under identical conditions and processed in parallel to preserve the relative intensities of fluorescence for comparative purposes. If not indicated, the scale bar represents 5 µm.

RESULTS

Exomer mutants show ammonium sensitivity due to the reduced uptake of tryptophan.

Exomer has been described to function as a cargo adaptor complex based on its role in the transport of Chs3, the catalytic subunit of the major chitin synthase in budding yeast (17, 21, 24). However, our recent work, based on the evolutionary characterization of exomer function across the fungi kingdom, suggests exomer may have additional functions (29). More importantly, S. cerevisiae exomer mutants showed multiple phenotypes that cannot be explained by known cargoes of exomer such as sensitivity to ammonium (21, 29).

In an effort to better understand the functionality of exomer, we first confirmed the ammonium sensitivity of the exomer mutant chs5∆ by showing that this mutant grew poorly in YEPD supplemented with 0.2 M ammonium (Figure 1A). This sensitivity was also observed in SD media (Figure S1A). Interestingly, the absence of the two paralogous pairs of ChAPs produced different growth phenotypes (Figure 1A). The bch1∆ bud7∆ double mutant was as sensitive to ammonium as chs5∆; however chs6∆ bch2∆ double mutant was not sensitive to ammonium. This result is notable since Chs6/Bch2 are known to function as cargo adaptors, whereas Bch1/Bud7 are thought to function in membrane association without cargo selectivity (22–24). These results could therefore reflect a role for exomer that is independent of its function as cargo adaptor.

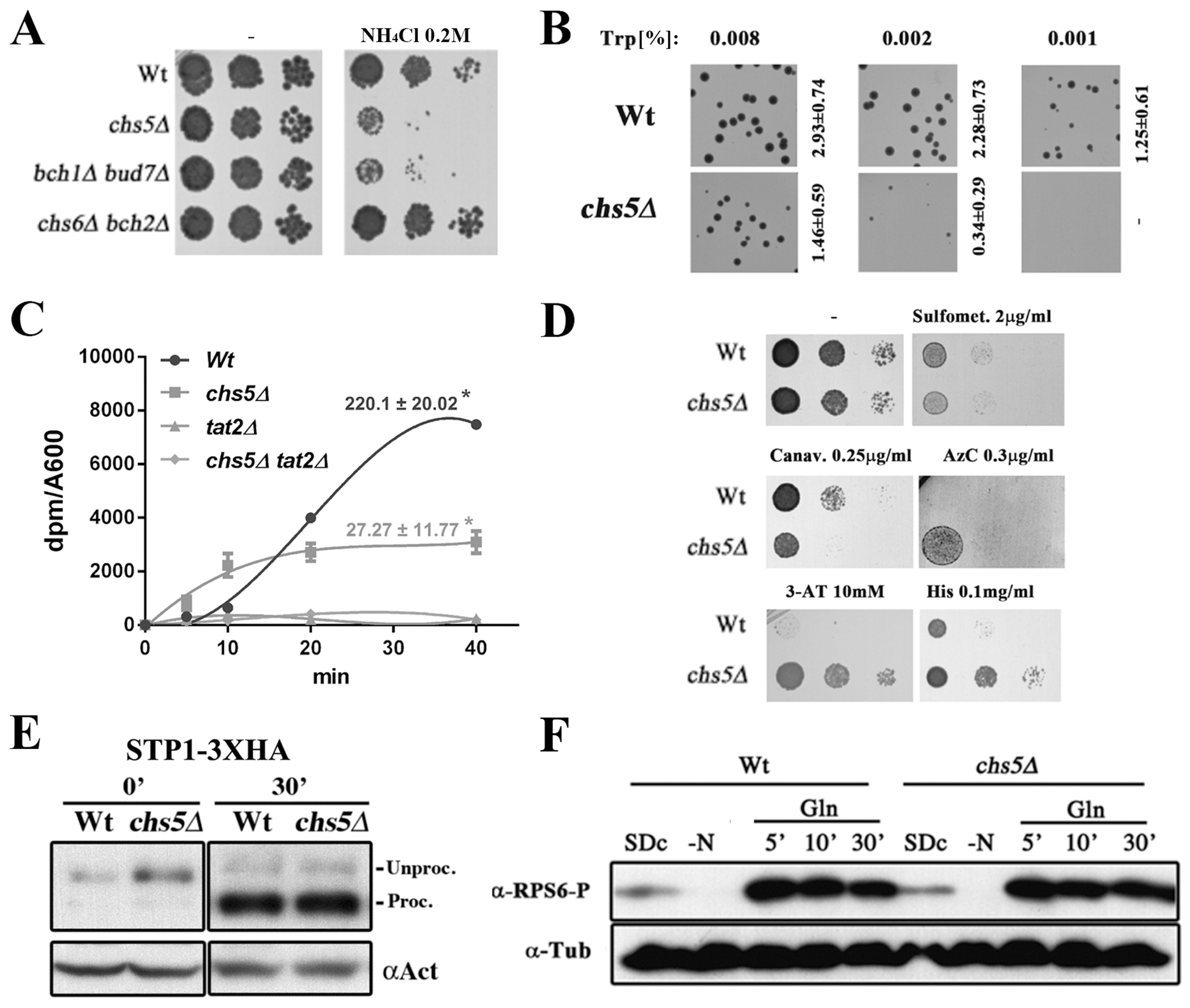

Figure 1.

Ammonium sensitivity of the exomer mutants is due to defects in amino acid uptake. (A) Overnight (O/N) cultures of the indicated strains in the W303 genetic background were diluted and plated onto YEPD media supplemented with 0.2 M NH4Cl. Note the similar level of sensitivity of the chs5∆ and bch1∆/bud7∆ mutants. (B) O/N cultures of the indicated strains in the W303 background were diluted and spread on synthetic defined media (SD) supplemented with the indicated concentrations of tryptophan. Note that low concentrations (%) of tryptophan (Trp) allowed the wild-type strain to completely grow, but was unable to efficiently support the growth of the chs5∆ mutant. The numbers indicate the average diameter ± standard deviation of the colonies growing on the different media quantified using ImageJ (Macro3). Also refer to supplemental Figure S1 for additional data on ammonium sensitivity. (C) L-[5-3H]-tryptophan uptake in SD media by the indicated X2180-derived prototrophic strains. Numeric values indicate the incorporation rate (dpm/A600/min) calculated as the slope of the linear regression made using 10 to 40 minutes time points. Note the absence of Trp incorporation in the tat2∆ mutants used as the control. (D) Sensitivity of the indicated X2180-derived strains to toxic amino acids analogs. Growth was analyzed in YEPD supplemented with the indicated concentrations of the following analogs: Sulfometuron-metil; L-canavanine; L-azetidin-2-carboxilate (AzC); 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) and L-histidine as indicated. (E) Western blot of the total protein from the cellular extracts of strains carrying STP1-3xHA integrated at the chromosomal locus. Cultures starved for 1 hour in YNB-N-aa media were transferred to rich YEPD media and samples were taken at 0 and 30 minutes. Note the similar processing of the Spt1 transcription factor in the wild-type and chs5∆ strains. (F) Induction of Rsp6 phosphorylation after adding glutamine. X2180 strains grown on SD complete media were transferred to media lacking a nitrogen source for 1h; glutamine (500 μg/ml) was then added to the media. Note that the kinetics of the phosphorylation induced in the wild type and chs5∆ are similar. Phosphorylation was determined by Western blot using a phospho-(Ser/Thr) Akt substrate antibody (#9611s, Cell SignalingTech). Also refer to supplemental Figure S2 for the rationale behind these experiments.

A first indication for the source of the ammonium sensitivity of the exomer mutants came from the observation that the chs5∆ mutant was not sensitive to ammonium in the prototrophic X2180 background (Figure S1A). Although ammonium toxicity in yeast is poorly understood, one mechanism for ammonium detoxification involves the active excretion of amino acids across the PM (43). We hypothesized that as cells excrete amino acids as a response to ammonium toxicity, they deplete internal pools of amino acids and the prototrophic strain is able to compensate by synthesizing higher levels of the essential amino acids. We further pinpointed the key auxotrophic requirement through the observation that the chs5∆ mutant was not sensitive to ammonium in the BY strain, which differs from W303 in that it is not auxotrophic for tryptophan. In order to confirm this, we transformed the chs5∆ mutant in the W303 background with different plasmids that restore the ability to synthesize amino acids for each auxotrophy. The restoration of the ability to synthesize tryptophan by a plasmid encoding TRP1, strongly reduced the ammonium sensitivity of the chs5∆ mutant, while the plasmid containing HIS3 and URA3 genes showed no effect on ammonium sensitivity (Figure S1B). By contrast, restoration of the ability to synthesize leucine by a plasmid encoding LEU2 slightly reduced ammonium sensitivity. Moreover, the addition of tryptophan to the medium also abolished ammonium sensitivity in all strains. These results could indicate that the chs5∆ mutant has a reduced uptake of tryptophan, and, therefore, this mutant may require higher amounts of external tryptophan for growth. Consistent with this model, the wild-type auxotroph strain in SD media could form colonies with as little as 0.001 mg/ml of tryptophan, while the chs5∆ mutant required 8 times more tryptophan in the medium to obtain substantial colony growth (Figure 1B). In order to confirm these results, we measured tryptophan uptake directly (Figure 1C). Consistent with the increased requirement for extracellular tryptophan, tryptophan uptake was severely reduced in the absence of exomer compared to wild-type yeast. However, uptake was not as low as cells lacking the tryptophan permease Tat2 (44). Together these results show that in exomer mutants, the deficient uptake of tryptophan restricts the growth of tryptophan auxotrophs in a low concentration of tryptophan or in the presence of ammonium.

Deficient Trp uptake of exomer mutants is directly linked to Tat2 permease but independent on nitrogen source regulation.

In yeast, tryptophan is primarily transported by one of two permeases, the general amino acid permease, Gap1, and the high affinity specific Trp-permease, Tat2 (45). In media containing high ammonium levels, such as SD, Gap1 is not expressed; therefore, we hypothesized that the chs5∆ defect could be associated with defects in Tat2 localization or function. Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpression of TAT2 suppressed the ammonium sensitivity of chs5∆ (Figure S1C). These results strongly suggest that ammonium and tryptophan phenotypes observed in chs5∆ are caused by defective function of Tat2 permease. Notably, the ammonium sensitivity of the double mutant tat2∆ chs5∆ was not fully suppressed by external tryptophan (Figure S1C, D), suggesting that the absence of exomer may affect additional amino acid transporters. This conclusion is consistent with the partial alleviation of ammonium sensitivity after LEU2 introduction (Figure S1B). As an additional test of the effect of exomer on amino acid transporters, we analyzed the sensitivity of exomer mutants to toxic analogs of different amino acids (46–50). Sensitivity to these analogs can indicate changes in the plasma membrane levels or activity of the relevant amino acid transporter. In the X2180 background, the exomer mutant chs5∆ was moderately more sensitive to the arginine analogue Canavanine, but significantly more resistant to the proline analogue AzC, to the HIS3 inhibitor 3-AT and to toxic concentrations of histidine (Figure 1D). These results are consistent with a potential defect in the uptake of several amino acids, owing to a defect in the localization or function of several amino acid permeases (AAPs).

Alternatively, the observed phenotypes could simply reflect a defect in the regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the absence of exomer. To test this possibility, we first investigated whether the chs5∆ mutant showed altered signaling through the Ssy1p-Ptr3p-Ssy5 (SPS) sensor of extracellular amino acids (45) (Figure S2B). We first compared the phenotypes of the cells lacking SPS to those of cells lacking exomer. We found that the phenotype of ssy1∆, the core SPS sensor, was not identical to that of chs5∆. Unlike chs5∆, ssy1∆ was resistant to canavanine and sensitive to 3-AT, although similar to chs5∆ it was resistant to AzC (Figure S2A). Moreover, chs5∆ ssy1∆ double mutant exhibited phenotypes of sensitivity to canavanine and resistance to AzC, 3-AT and to toxic concentrations of histidine as that of chs5∆. We then monitored whether loss of exomer disrupted SPS function. We found that the localization of Ssy1-GFP in the chs5∆ strain was indistinguishable from the wild type (Figure S2C). More importantly, loss of exomer did not affect the proteolytic processing of the SPS effector Stp1 in response to amino acids, a key step in the SPS signaling pathway (45) (Figure 1E). Taken together, these observations indicate that the SPS signaling pathway is fully functional in the absence of exomer.

As an additional test for whether exomer controls amino acids signaling, we investigated the TORC1 pathway, which regulates many AAPs (45). TORC1 signaling occurs in preferred nitrogen sources like glutamine and during this signaling, two kinase regulatory subunits, Gtr1 and Tco89, are recruited to the vacuolar membrane, from where they triggers the phosphorylation of the small ribosomal subunit, Rsp6, and the Nitrogen Catabolite Repression (NCR) signaling pathway transcription factor, Gln3 (51, 52) (Figure S2D). We found that Gtr1 and Tco89 localized normally at the vacuolar membrane in the chs5∆ mutant (Figure S2E), the phosphorylation timing of Rps6 occurred normally in this mutant upon growth in different nitrogen sources (Figure 1F) and the levels of Gln3 phosphorylation were indistinguishable from control under different nutritional conditions (Figure S2F).

All of these results strongly indicate that nitrogen signaling occurs normally in the absence of exomer. We therefore hypothesized that the observed phenotypes might be associated directly with a defective transport of one or several AAPs.

Exomer is required for proper intracellular traffic of the Tat2 and Mup1 permeases.

In order to test this hypothesis, we first monitored the localization of the amino acid permeases Tat2 and Mup1. These proteins localized at the PM in induction media under steady-state conditions (Figure 2A) in either the wild-type or chs5∆ mutant strains. However, in the chs5∆ mutant, Tat2 was conspicuously absent at the vacuole and some of the protein was localized in intracellular spots. Similarly, Mup1 was also localized in intracellular spots in the absence of exomer. Terminally-tagged versions of Tat2 show impaired endocytosis (see materials and methods section and references therein). Therefore, to confirm whether Tat2 localization changes in chs5∆, we performed subcellular fractionations using an internally HA-tagged version of Tat2 (Figure 2B). In the wild-type strain, Tat2–3xHA localized primarily in the lightest fractions of the gradient together with Pma1, a marker of the plasma membrane fraction. However, in the chs5∆ mutant Tat2–3xHA showed a bimodal distribution, with part of the protein co-migrating with Pma1 and the other significant part co-migrating with the TGN/endosomal marker Pep12 in the heavier fractions. These observations suggest that chs5∆ causes partial intracellular accumulation of Tat2 and Mup1 at the TGN/endosomal compartment. This event would lead to a reduction in the levels of the permeases at the PM, leading to the tryptophan and amino acid analog responses described above.

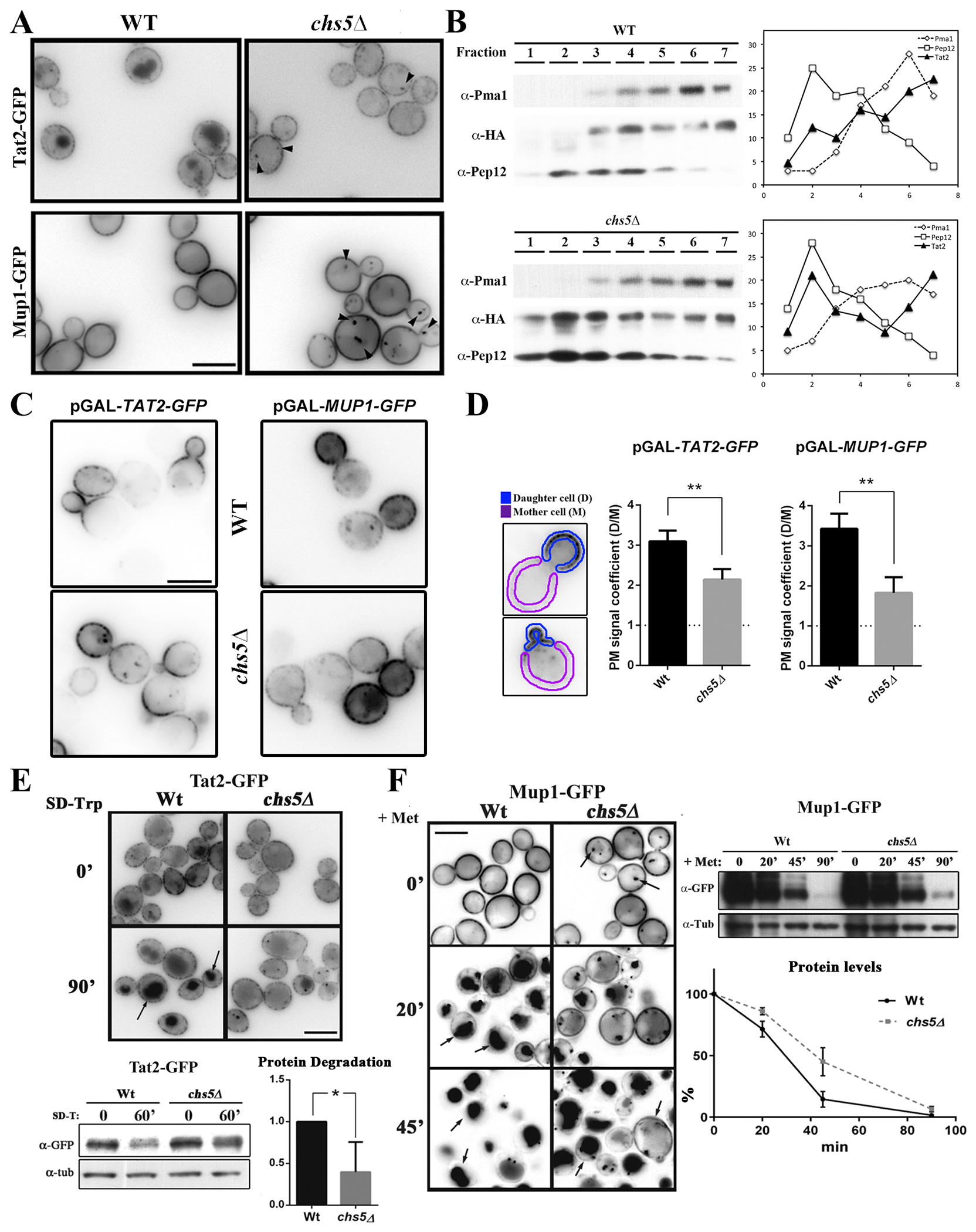

Figure 2.

Exomer controls the traffic of several amino acid permeases. (A) Localization of Tat2-GFP and Mup1-GFP under steady state growth conditions in induction media. Note the subtle differences of Tat2 and Mup1 intracellular localization in the exomer mutant and their accumulation at intracellular spots (see arrowheads). (B) Intracellular distribution of Tat252-53-3xHA in wild-type and chs5∆ strains after discontinuous subcellular fractionation. Proteins were visualized by Western blot as described in the Material and Methods section. Graphs on the right represent the percentage of each protein at each fraction. Pma1 and Pep12 were used as markers for the PM and TGN/endosome fraction respectively. (C) Analysis of the PM anterograde transport of Tat2-GFP and Mup1-GFP, with their gene expression under the control of the GAL1 promoter. In both cases, for pGAL-TAT2-GFP and pGAL-MUP1-GFP strains, the cells were grown O/N in SD 2 % raffinose media and then transferred to a SD 2% galactose media. In the case of Tat2, and taking in to account the lethality of the lack of Tat2, 0.02% Trp was added to the SD raffinose media and the galactose induction phase was done in a SD media with standard tryptophan concentrations (0.002 %). All images were acquired just one hour after the addition of galactose. (D) Quantitative analysis of the polarization of these proteins along the PM using images from the experiment shown in C. A daughter cell/ mother cell PM signal coefficient was measured following the scheme shown in the left panel (details in Material and Methods section). The horizontal dashed line represents the condition of the lack of polarization of PM protein distribution. (E) Localization and dynamics of Tat2-GFP after the induction of its endocytosis in Trp-depleted media (53). The same experiment was analyzed by Western blot and relative protein degradation after 60 min of induction was calculated from 3 independent experiments (lower panels). (F) Localization and dynamics of Mup1-GFP after the induction of its endocytosis by adding methionine (20 mg/L) (54). The same experiment was analyzed by Western blot and relative protein levels were calculated for each point (lower panel).

The steady state localization of AAPs reflects the balance of anterograde transport of newly synthesized proteins, endocytosis, and recycling. Therefore, the mislocalization of Tat2 or Mup1 could reflect a defect in any of these steps. To test whether exomer contributes to anterograde traffic of Tat2 and Mup1, we used a regulated expression system based on the GAL1 promoter. Growth on galactose induces expression thus allowing us to examine anterograde transport based on the arrival of each permease at the PM. One hour after induction, both proteins were readily apparent at the plasma membrane in both wild-type and chs5∆ cells, suggesting that the overall rate of anterograde traffic is not dramatically reduced in chs5∆ cells (Figure 2C). However, both Tat2 and Mup1 were less polarized in the chs5∆ mutant. In wild-type cells, both Tat2 and Mup1 were highly polarized in the growing bud, whereas in the chs5∆ mutant a significant amount of each transporter was observed spread along the PM of the mother cell. A quantitative analysis of Tat2 and Mup1 distribution indicated that the PM signal in the daughter cells is significantly reduced in the absence of the exomer for both proteins (Figure 2D). Although the functional significance of the defect in polarized distribution is unclear, these results indicate that exomer contributes to the polarized delivery of these proteins to the PM, in a similar fashion to what has been described for Ena1 (42).

Following on, we examined the effect of exomer on the behavior of AAPs after endocytosis. Tat2 is endocytosed after the depletion of tryptophan from the media and trafficked to the vacuole for degradation (53). In a wild-type strain, Tat2-GFP signal was increased in the vacuole after tryptophan depletion and the total amount of the protein was significantly reduced (Figure 2E). However, in the chs5∆ mutant, fluorescence in the vacuole was reduced compared to the wild type, and intracellular spots became more numerous and intense (Figure 2E). In addition, the total amount of Tat2 was significantly higher in the chs5∆ mutant than in the wild type after tryptophan depletion. Mup1 is also rapidly endocytosed, trafficked to the vacuole and degraded in presence of an excess of methionine in wild-type cells (Figure 2F) (54). Similar to Tat2, in cells lacking exomer Mup1 traffic to the vacuole was reduced 20 minutes after adding methionine, with fewer cells showing vacuolar fluorescence and more cells showing substantial plasma membrane signal in the chs5∆ mutant compared to the wild type. This defect was associated with an increase in the number of cells with bright intracellular spots. However, vacuolar localization was apparent in chs5∆ after 45 minutes. Analysis of the total levels of Mup1 by Western blot after adding methionine indicated that protein degradation was significantly delayed in the absence of exomer (Figure 2F). These results are consistent with a function for exomer in the proper traffic of AAPs, and may explain the phenotypes associated with chs5∆ in terms of the cells being sensitive to different levels of tryptophan and toxic amino acids.

Exomer dependent recycling of Tat2 differs from that of Chs3.

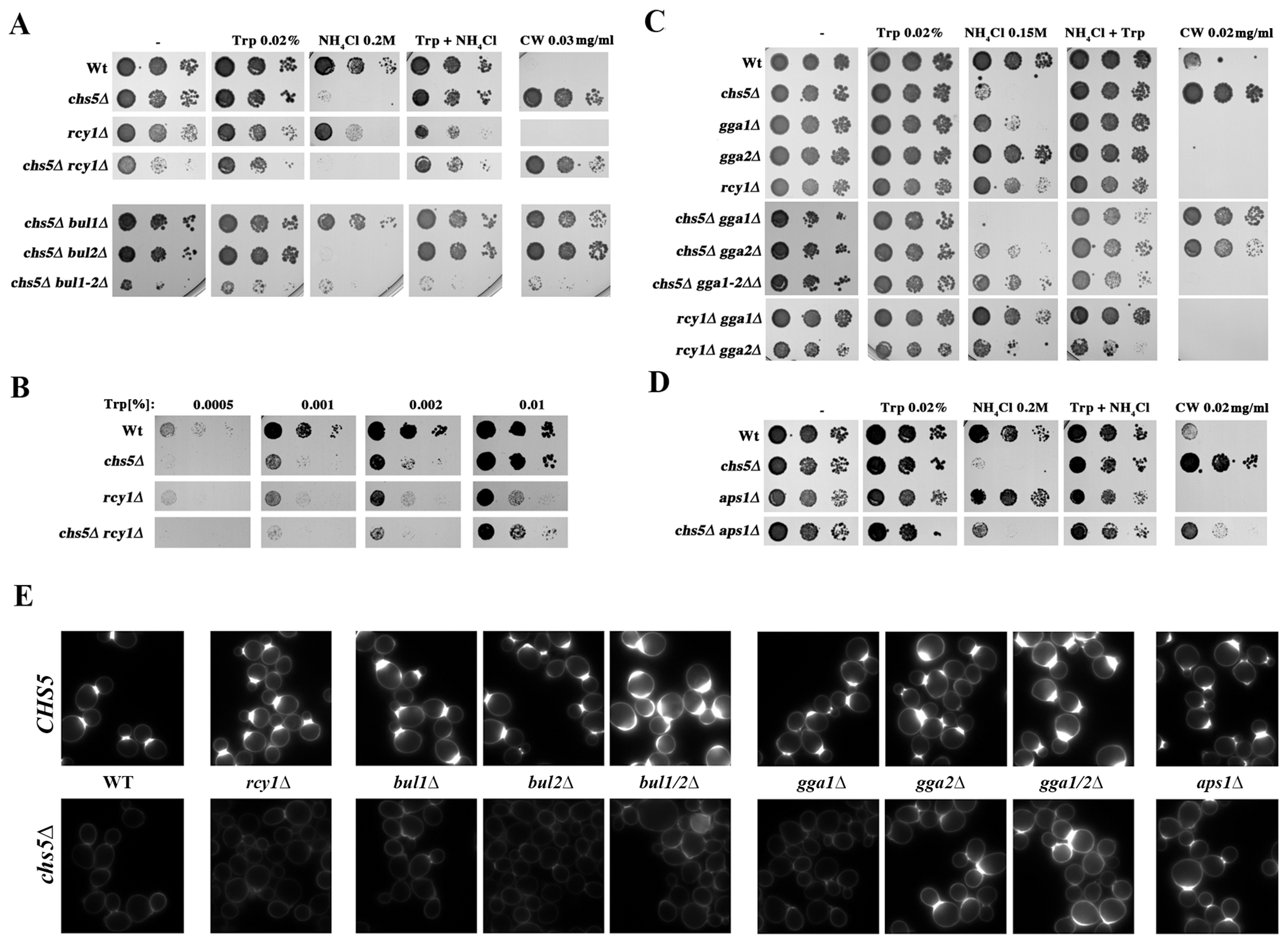

Based on the proposed role of exomer in the recycling of Chs3 (27), we tested whether exomer controlled the recycling of Tat2. In yeast, the recycling of Tat2 and Mup1 depends on the f-box protein Rcy1 (55). To determine whether exomer contributes to this step in recycling, we first compared the phenotypes of rcy1∆ and chs5∆ mutants. We found that rcy1∆ was sensitive to ammonium, and, as previously reported, required an external supply of tryptophan for growth (55) (Figure 3A,B). These results are consistent with a model that proposes that both exomer and Rcy1 may participate in the recycling of AAPs. Interestingly, the double rcy1∆ chs5∆ mutant required a greater concentration of tryptophan for growth than the single-gene deletion mutants, which could suggest Rcy1 and exomer act at different steps in recycling or that the recycling pathway is only partially functional in the absence of either factor (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The need for tryptophan and the blockage of chitin synthesis of the chs5∆ mutant are differentially suppressed by several mutations affecting TGN traffic. (A) Growth of the indicated strains in YEPD media with the indicated supplements. (B) Growth of the indicated strains in SD w/o Trp media supplemented with the indicated concentrations of Trp. (C, D) Growth of the indicated strains in YEPD media with the indicated supplements. All strains used are W303 derivatives grown O/N in YEPD media, serially diluted and plated onto the indicated media. Each panel represents a single experiment using a unique set of plates; note the slight differences in the growth of similar strains between different panels/experiments. (E) Calcofluor staining of the indicated strains. Cells grown in YEPD media were stained for 1.5 hours with calcofluor (50 μg/ml). Note the reduction in calcofluor staining shown by all chs5∆ strains that is partially reverted by gga2∆, gga1∆/gga2∆ and aps1∆ concomitant mutations. This result coincides with their higher level of sensitivity to this drug, which is shown in the other figure panels.

To distinguish between these possibilities, we explored the genetic interactions between chs5∆ and rcy1∆ and additional regulators of Tat2. We first examined clathrin adaptors Gga1 and Gga2, which alter cell surface levels of Tat2 in some mutant backgrounds by controlling sorting from the TGN to the vacuole (36). We found that chs5∆ and rcy1∆ showed different effects when combined with deletion of gga2∆, or the gga1∆ gga2∆ double mutant (Figure 3C). The ammonium sensitivity of chs5∆ was suppressed by gga2∆ and more so by the gga1∆ gga2∆ double mutation. In contrast, the rcy1∆ phenotype was not suppressed by gga2∆. Interestingly, the gga1∆ mutant was sensitive to ammonium on its own, a sensitivity that was additive with the chs5∆ mutant, but not with the rcy1∆ mutant. Together these results suggest that exomer and Rcy1 may affect different steps of AAPs trafficking.

The suppression of the ammonium sensitivity of chs5∆ by gga2∆ is reminiscent of the previously reported suppression of the calcofluor resistance of chs5∆ by gga2∆ (27, 56). We therefore sought to determine whether the exomer-mediated traffic of Tat2 was similar to the exomer-mediated traffic of Chs3. In addition to Gga1 and Gga2, the clathrin adaptor protein complex AP-1 alters the traffic of Chs3 in exomer mutant cells (27). We first asked whether deletion of the small subunit of AP-1 (aps1∆) suppressed the ammonium sensitivity of chs5∆. Unlike calcofluor resistance, aps1∆ did not suppress the ammonium sensitivity of chs5∆ (Figure 3D). Similarly, aps1∆ did not suppress the sensitivity of chs5∆ to low tryptophan while gga2∆ did it efficiently (Figure S3), suggesting that the traffic of Chs3 and AAPs are strikingly different.

To further explore the differential requirements for Chs3 and AAP traffic, we explored the role of the arrestin family of ubiquitin ligase adaptors because the recycling of Tat2 is controlled by its ubiquitination mediated by the Bul1 arrestin-like protein (57). Accordingly, bul1∆ suppressed the ammonium sensitivity of the chs5∆ mutant (Figure 3A). In contrast, after analyzing calcofluor sensitivity and staining, the deletion of BUL1 did not restore Chs3 PM transport in the chs5∆ mutant (Figure 3A, E). Because Bul1 is one of a number of arrestin-like adaptors, we also tested the partially redundant Bul2 ligase, the bul1∆ bul2∆ double mutant, and individual deletions of ten additional arrestin ligases. None of the arrestin mutants suppressed the calcofluor resistance of chs5∆, highlighting the difference between AAPs and Chs3 (See Figure S4). In summary, while both Tat2 and Chs3 proteins can be re-routed by Gga2 proteins in the absence of exomer, the two proteins likely diverge at one or more steps in their traffic, suggesting that the mechanistic requirement for exomer differs for the two proteins.

Exomer is involved in traffic to late endosomes by modulating the proper assembly of the clathrin adaptor complexes.

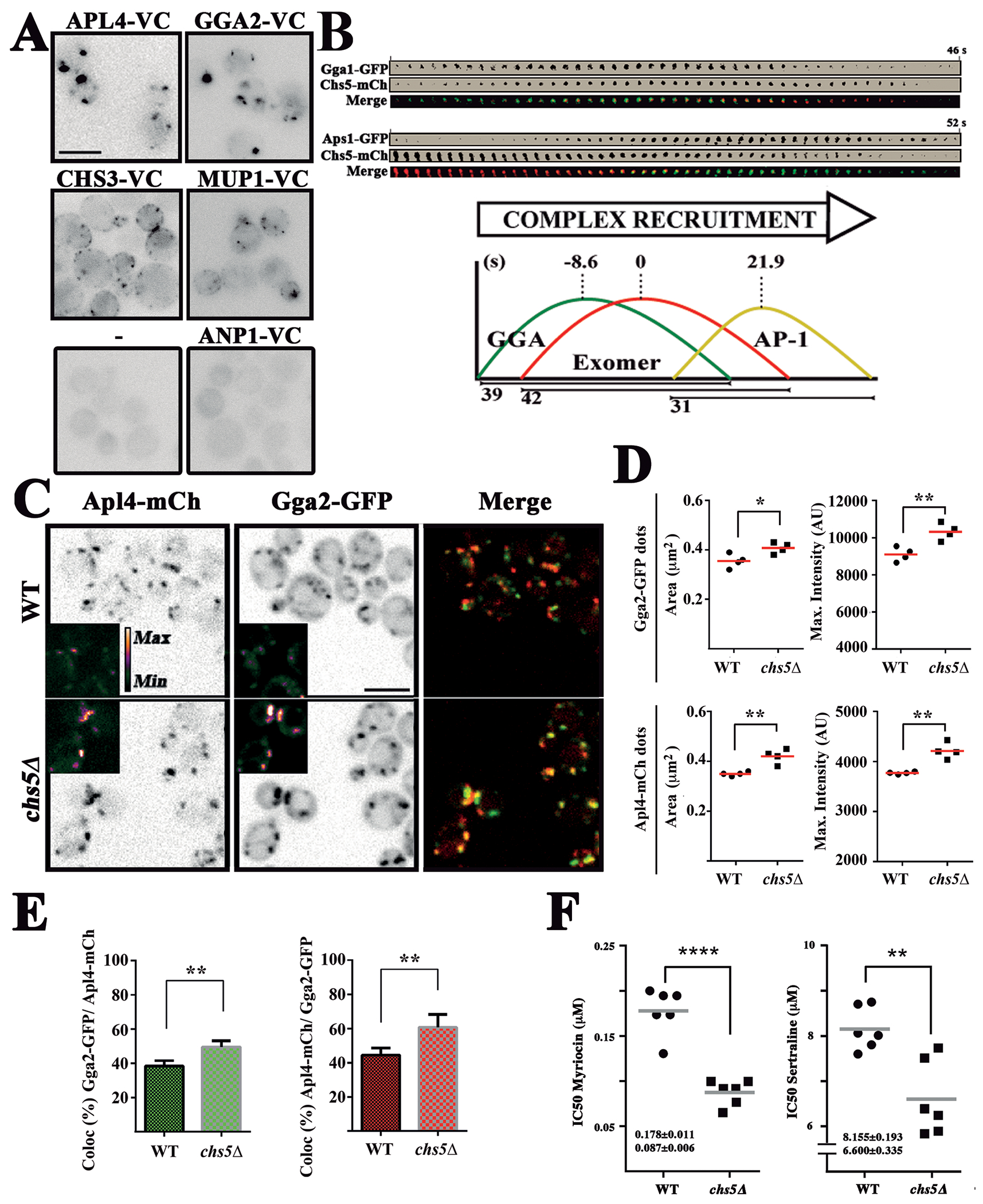

Exomer and clathrin adaptors mediate the traffic of common cargoes including Chs3 and AAPs, however, their functions appear to be largely antagonistic to one another. Mechanistically, this antagonism could be explained by direct physical competition between exomer and clathrin adaptors for cargo, or something more complex. In order to understand the antagonistic roles of exomer and clathrin adaptors, we explored their proximity to one another using bi-molecular fluorescence complementation (BIFC) (39). Exomer comes into close proximity to both AP-1 and Gga2, based on the appearance of fluorescent puncta in strains containing Chs5-VN and either Apl4-VC or Gga2-VC. Our BIFC results also confirmed the previously reported physical interaction of exomer with its cargo Chs3 (Figure 4A), but also revealed close proximity of exomer with Mup1 (Figure 4A), suggesting exomer may play a direct role in Mup1 traffic.

Figure 4.

Exomer contributes to TGN clathrin adaptor recruitment. (A) BIFC analysis of the interaction of Chs5-VN with the indicated proteins tagged with the VC fragment. Note the unexpected localization of Chs5-VN/Chs3-VC along the PM. (B) Time-lapse analysis of the recruitment of the clathrin adaptor complexes and exomer. Individual dots for each protein were visualized by two color confocal spinning disk microscopy over time. Graphs represent the average recruitment duration of each complex using exomer as a reference. For more detailed information see Figure S5. (C) Localization of Apl4-mCh and Gga2-GFP in the wild-type and chs5∆ strains. Note the larger and more intense dots of both proteins in chs5∆ and the apparent increase in co-localization. (D) Quantitative analysis of Gga2-GFP and Apl4-mCh dots in the experiment shown in C. Note the significant increase in the area and intensity of the dots for both proteins in the absence of exomer. The results are the average of 4 independent experiments. (E) Co-localization analysis between Gga2-GFP and Apl4-mCh. The values are the average of four independent experiments. (F) Sensitivity of the indicated strains to myriocin and sertraline represented by the IC50 coefficient, calculated as described in the Material and Method section. Values represent the average of six independent experiments.

Because BIFC can trap transient proximity between proteins and does not report on the dynamic changes in protein localization, we next addressed the dynamic TGN localization of exomer and clathrin adaptors using two-channel spinning disk-confocal microscopy (Figure 4B, Figure S5). Previous work has established an ordered recruitment of clathrin adaptors, with Gga2 reaching peak fluorescence several seconds before AP-1 (6, 58). We found that exomer is recruited shortly after GGA, and significantly before (21.9 seconds) AP-1 (Figure 4B), a temporal distribution that overlaps with both clathrin adaptor complexes. This distribution is also consistent with the co-localization observed between exomer and GGA and AP-1 complexes (Figure S5E).

Next, we explored whether the absence of exomer affected the localization of clathrin adaptors. In the chs5∆ mutant, Gga2 collapsed in significantly brighter and larger puncta compared to wild-type cells (Figure 4C,D) and similar results were observed for the AP-1 (Apl4) complex. Moreover, co-localization between Gga2 and Apl4 was significantly increased in the chs5∆ mutant compared with the control (Figure 4C,E).

In order to confirm the physiological relevance of these defects, we determined the sensitivity of the chs5∆ mutant to sertraline and myriocin. These drugs affect membrane fluidity and lipid biosynthesis, and selectively inhibit the growth of yeast with impaired AP-1 functions (59, 60). We found that chs5∆ mutant was significantly more sensitive to both drugs, showing a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.087 ± 0.005 mM and 6.60 ± 0.33 mM to myrocin and sertraline respectively, IC50s significantly (p<0.01) lower than those observed for the wild-type strain (0.178 ± 0.011 mM and 8.16 ± 0.19 mM). This increased sensitivity to both drugs is consistent with altered AP-1 function in the chs5∆ mutant (Figure 4F).

Re-exploring the functional link between Arf1 GTPase and the exomer complex.

Exomer was described as an Arf1 GTPase-dependent protein complex (13,15) and was later co-crystalized with Arf1 (14). Interestingly, TGN clathrin adaptors also bind Arf1 GTPase (6, 20). Therefore, the antagonistic functions of these complexes may be through direct competition for active Arf1.

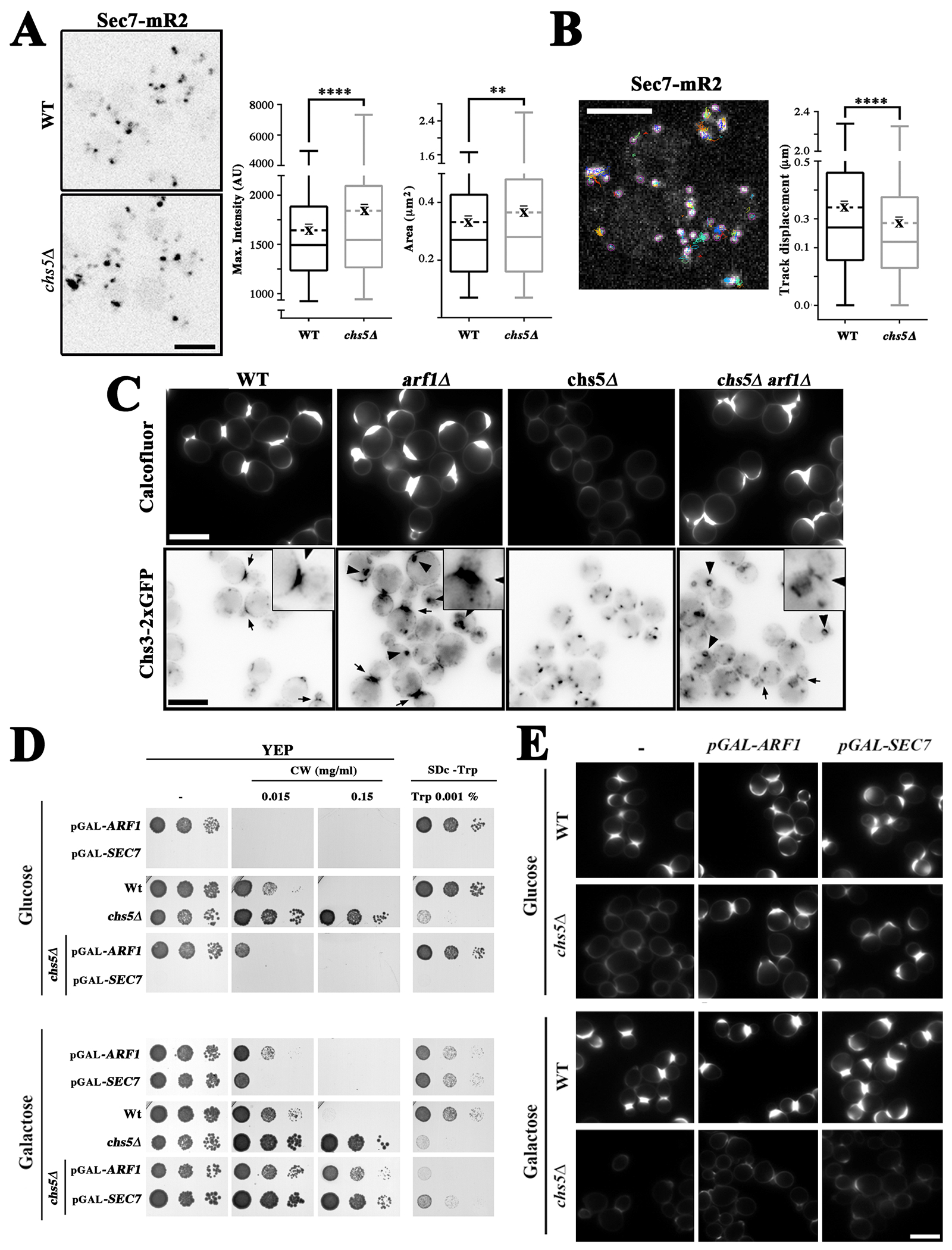

We next sought to monitor the effects of exomer on Arf1 localization. Unfortunately, GFP tagging of Arf1 disrupts its function (61) and alters TGN/EE morphology (Figure S6A), similarly to what has been described for the null mutant (62). We therefore analyzed as an alternative the localization of Sec7, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that stimulates Arf1 activity at the TGN (63) promoting clathrin adaptor localization (6). We found that similar to clathrin adaptors, the intensity and area of Sec7 puncta were greater in the chs5∆ mutant (Figure 5A). Moreover, time-lapse analysis showed that in the exomer mutant chs5∆ the Sec7 dots moved significantly slower and showed reduced track displacement, although the lifespan of the structures was only slightly increased (Figure 5B, Figure S6B,C). The functional significance of this altered movement is unclear but, altogether, our results suggest that exomer could influence the behavior of clathrin adaptors through Arf1/Sec7. In view of this implication of exomer in Arf1/Sec7 dynamics, we sought to revisit the role of Arf1/Sec7 in exomer functionality.

Figure 5.

Functional link between Arf1 GTPase and the exomer complex. (A) Localization of Sec7-mR2 in the wild-type and chs5∆ strains. The right panels show the quantitative analysis of Sec7-mR2 TGN structures using Macro2. The box-plots represent the intensity and the area of Sec7-mR2 dots (the average is represented by the dashed line, n ≥ 700 dots acquired in 4 independent experiments). (B) Analysis of Sec7-mR2 dynamics in the absence of exomer with the TrackMate ImageJ plugin. The Box-plots represent the average track displacement of Sec7-mR2 dots calculated from more than 2500 trajectories for each strain acquired in 4 independent experiments (the average is represented by the dashed line). See Figure S6C for additional data on the dynamics of Sec7. (C) Effect of Arf1 deletion on chitin synthesis. Upper panels show calcofluor staining in the indicated strains. Lower panels show the localization of Chs3–2xGFP in the indicated strains. Arrows show the accumulation of Chs3 at bud necks and the arrowheads mark aberrant TGN/EE structures. (D) Effects of the deregulation of Arf1/Sec7 expression in cells expressing the indicated chromosomal genes from the GAL1 promoter in the wild-type or chs5∆ strains. Cells were grown O/N in YEP 2 % raffinose and 0.1 % galactose, serially diluted and spotted on the indicated media containing glucose (upper panel) or galactose (lower panel) as the carbon source. Growth was recorded after 2–3 days at 28ºC. Note how the pGAL1-SEC7 strains were unable to grow on media containing glucose. (E) Calcofluor staining of multiple strains in which the indicated chromosomal gene is under the control of the GAL1 promoter. Cells were grown O/N as indicated above and transferred to the indicated media for two hours; then, calcofluor was added and chitin staining was visualized after an additional 90 minutes. Note that repression of ARF1 and SEC7 in glucose media restored calcofluor staining in the chs5∆ mutant.

We first addressed the effect of the arf1∆ mutation. Surprisingly this mutant showed increased levels of chitin based on calcofluor staining (Figure 5C, upper panels), which were in clear agreement with increased levels of Chs3 at the bud neck (Figure 5C, lower panels, see arrows and amplified insets), despite the partial accumulation of part of this protein in aberrant TGN/EE structures (Figure 5C, lower panels, see arrowheads). The absence of Arf1 reversed the effect of the chs5∆ mutation on calcofluor staining and Chs3 localization as previously described (27), likely through rerouting Chs3 to the PM in a less polarized fashion (Figure 5C). Similar results were obtained when we depleted Arf1 by growing the pGAL1-ARF1 strain in glucose. (Figure 5D, E). Moreover, Arf1 depletion in glucose also relieved the calcofluor and tryptophan phenotypes associated with the chs5∆ mutant (Figure 5D, E and S6D). Although the effects of Sec7 were difficult to assess due its absence being lethal, the transient depletion of Sec7 in the pGAL-SEC7 strains after growth in glucose slightly increased chitin synthesis in the wild-type strain and restored chitin synthesis in the chs5∆ mutant (Figure 5D,E).

Interestingly, overexpression of either Arf1 or Sec7 in the wild-type strain after growth in galactose caused hypersensitivity to calcofluor (Figure 5D), which in the case of Sec7 could be linked to an increased deposition of chitin towards the bud (Figure 5E). However, the overexpression of either protein did not restore chitin synthesis in chs5∆. In contrast, overexpression of Sec7, but not of Arf1, alleviated the tryptophan and ammonium phenotypes of chs5∆ mutant (Figure 5D and S6D), suggesting that Sec7 has a different effect on the traffic of amino acid permeases.

Finally, given the ability of exomer to influence the localization of clathrin adaptors, we tested the effect of GGA overexpression on exomer function using the GAL1 promoter. We found that the overexpression of Gga2 in a wild-type strain significantly reduced the recruitment of exomer and AP-1 complexes at the TGN (Figure S7A–D). However, this overexpression did not produce a significant physiological effect on chitin synthesis or ammonium sensitivity, probably because Gga2 exerts a pleiotropic effect on both complexes (Figure S7E, F). Remarkably, in the absence of the exomer complex, overexpression of Gga2 partially recovered chitin synthesis and diminished sensitivity to ammonium (Figure S7E, F). While the chitin phenotype could be explained by alteration of the AP-1 complex, which in turn promotes the aperture of the alternative route for the chitin synthase to the PM, the ammonium phenotype is probably more complex and likely associated with general alterations of the TGN.

Altogether our results support the existence of a complex network of functional interactions between Arf1, exomer and clathrin adaptors. Moreover, although it is known that Arf1 activity favors the polarized delivery of Chs3 by exomer, this activity, contrary to previous reports (17), was found not to be essential for exomer function since polarization of Chs3 occurred normally in the absence of Arf1/Sec7 (Figure 5C), when exomer was still present at the TGN/EE membranes (Figure S6E). In contrast, the ablation of Arf1/Sec7 function reroutes Chs3 and amino acid permeases to the PM, independently of exomer, through alternative route/s likely to be associated with the effects of this ablation in the recruitment of clathrin adaptors (6). Interestingly, overexpression of Sec7 only had a significant effect on the traffic of amino acid permeases in the absence of exomer, reinforcing our previous findings (see above) that suggest that different links exits between exomer and Chs3 and amino acid permeases.

The intracellular traffic of the exomer bona fide cargoes is dependent on their competitive interactions between exomer and AP-1 complexes.

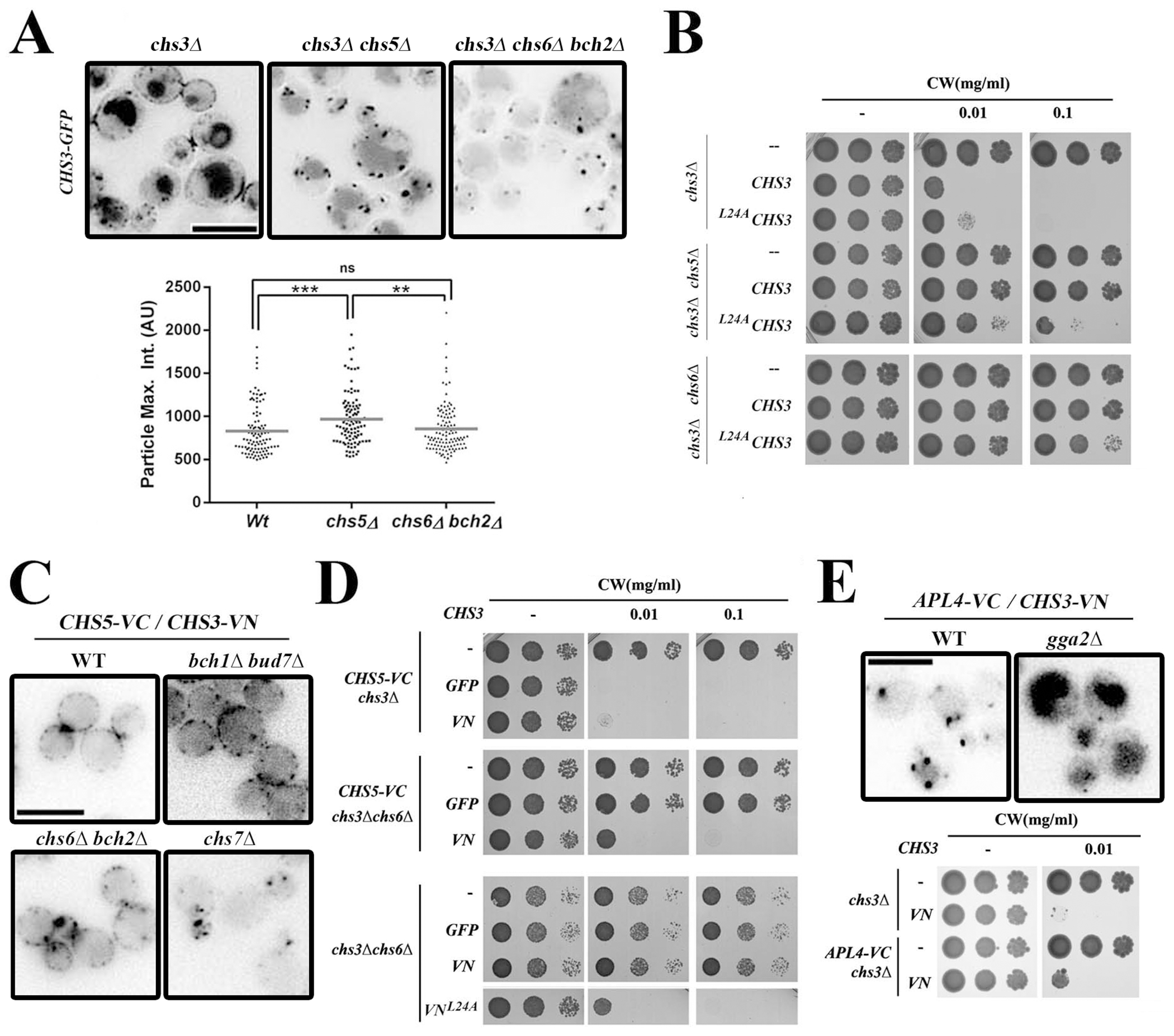

Previous studies suggest that exomer assembled by different ChAPs subunits may have dramatically different functions. The Chs6/Bch2 pair is proposed to directly mediate association with selected cargoes like Chs3, whereas the Bch1/Bud7 pair contributes to exomer association with membranes and membrane remodeling together with Arf1 (22–24). Given the effects of exomer on clathrin adaptors, we revisited the roles of the different exomer subunits in the traffic of Chs3.

In the absence of a functional exomer (chs5∆), or when both members of a group of ChAP paralogs are deleted (chs6∆ bch2∆ or bch1∆ bud7∆), yeast cells become resistant to calcofluor owing to the intracellular retention of Chs3 (review in (64)). However, we found that in the complete absence of functional exomer the subcellular localization of Chs3 differed compared to the loss of the cargo binding paralogs Chs6/Bch2. In the absence of a functional exomer (chs5∆), Chs3 was found in significantly brighter puncta compared to the wild type (Figure 6A), similar to what was observed for Gga2/Apl4 in this mutant (Figure 4C). A similar phenotype was also seen in the bch1∆ bud7∆ double mutant (Figure S8B). However, in the chs6∆ bch2∆ mutant, Chs3 puncta were similar to that of the wild type. This suggests exomer complexes associated with different ChAPs paralogs may have different effects on Chs3 traffic. We hypothesized that exomer containing the Chs6 and/or Bch2 paralogs may strictly act as a cargo receptor whereas the exomer containing Bch1 and/or Bud7 paralogs may have more general effects on traffic, as described above for AAPs.

Figure 6.

Analysis of Chs3 transport reveals different phenotypes among the mutants of different exomer subunits and shows cargo competition between the exomer and AP-1 complexes. (A) Localization of Chs3-GFP in chs5∆ and chs6∆ bch2∆ mutants. Static images and quantitative analysis of the intracellular dots of Chs3 in both mutants are shown. Note the reduced diameter and intensity of Chs3-GFP in the chs6∆ bch2∆ strain compared to chs5∆. (B) Calcofluor sensitivity of cells expressing wild-type Chs3 and mutant L24AChs3 proteins. (C) Analysis of the Chs3/Chs5 interaction by BIFC. Most of the signal is distributed along the PM, even in the absence of a functional exomer as in the bud7∆ bch1∆ double mutant. However, this localization is prevented if Chs3 exit from the ER is blocked as in the chs7∆ mutant. (D) Calcofluor resistance of the different Chs3 constructs in the indicated strains. Note that the interaction Chs5-VC/Chs3-VN suppressed the resistance of the chs6∆ mutant to calcofluor, similar to the effects observed for the L24AChs3 protein. (E) Analysis of the Chs3/Apl4 interaction by BIFC. Upper panel shows localization of Chs3/Apl4 interaction. Lower panel shows calcofluor resistance of the indicated strains. Note that Apl4-VC/Chs3-VN interaction confers moderate resistance to calcofluor on its own (lower panel).

To test this hypothesis, we explored the effect of the exomer mutants on the localization of Chs3L24A mutant protein which cannot bind the AP-1 complex (25). We found that chs5∆ cells expressing Chs3L24A were sensitive to calcofluor white, whereas chs6∆ cells expressing Chs3L24A were moderately resistant to the same calcofluor concentration (Figure 6B). This suggests that in cells lacking Chs5, Chs3L24A reaches the cell surface, while in cells lacking Chs6 Chs3L24A does not reach the plasma membrane. As an independent confirmation, we monitored the localization of Chs3L24A-GFP in chs5∆, chs6∆ bch2∆ and bch1∆ bud7∆ cells. We found Chs3L24A-GFP on the cell surface in chs5∆ and bch1∆ bud7∆ cells but not in chs6∆ bch2∆ cells, indicating that the two ChAP paralogous pairs play different roles in Chs3 traffic (Figure S8B).

We sought to explore this hypothesis further by examining the localization of Chs5-Chs3 BIFC complexes in different ChAPs mutant backgrounds. We hypothesized that if complexes containing Chs6/Bch2 were exclusively required for cargo loading in exocytic vesicles then the formation of the Chs5-Chs3 BIFC complexes could be able to bypass this requirement. Surprisingly, we found that Chs5-Chs3 BIFC complexes localized along the cell surface in both chs6∆ bch2∆ or bch1∆ bud7∆ cells (Figure 6C, S8A). However, these BIFC complexes could not reach the PM in the absence of Chs7 (chs7∆ strain), a specific chaperon implicated in a Chs3-exocytic step prior to exomer complex function (37). This suggests that, under this condition, complexes containing only Bch1/Bud7 are competent for exocytosis, and that exocytosis may not be the only role of exomer containing Chs6 and Bch2. Consistent with these findings, we found that the concomitant expression of Chs5-VC and Chs3-VN was able to restore calcofluor white sensitivity to chs6∆ (Figure 6D). Interestingly, the Chs5-Chs3 BIFC complexes were conspicuously absent from the neck region in both double mutants, chs6∆ bch2∆ and bch1∆ bud7∆, consistent with a lower polarization of the protein similar to the localization observed for the Chs3L24A protein, which is unable to bind the AP-1 complex (Figure S8A).

One explanation for these phenotypes is that the artificially stable Chs3-Chs5 dimer induced by BIFC tags prevents AP-1 from retaining Chs3 in the TGN and therefore the protein can reach the PM without Chs6 or Bch1/Bud7 following an alternative route (27). To test if the converse could be true, we tested the effect of the formation of Apl4-Chs3 BIFC complexes on global Chs3 localization. We found Apl4-Chs3 BIFC complexes were only detected as intracellular dots, consistent with the intracellular localization of the AP-1 complex (Figure 6E, upper panel). The formation of these complexes was highly specific because they were clearly altered in the absence of Gga2 (Figure 6E), a finding that clearly agrees with the proposed role for GGAs in the recruitment of AP-1 to the TGN (6). More important, cells expressing these BIFC complexes were moderately resistant to calcofluor, indicating that artificial stable interaction of Chs3 with AP-1 reduced the exit of Chs3 to the plasma membrane (Figure 6E, lower panel).

Altogether our results suggest that the exomer and AP-1 complexes can compete for some cargoes in S. cerevisiae, such as Chs3, but not others such as AAPs. These findings may be highly relevant and influence our understanding of how protein sorting at the TGN (see discussion) may have evolved.

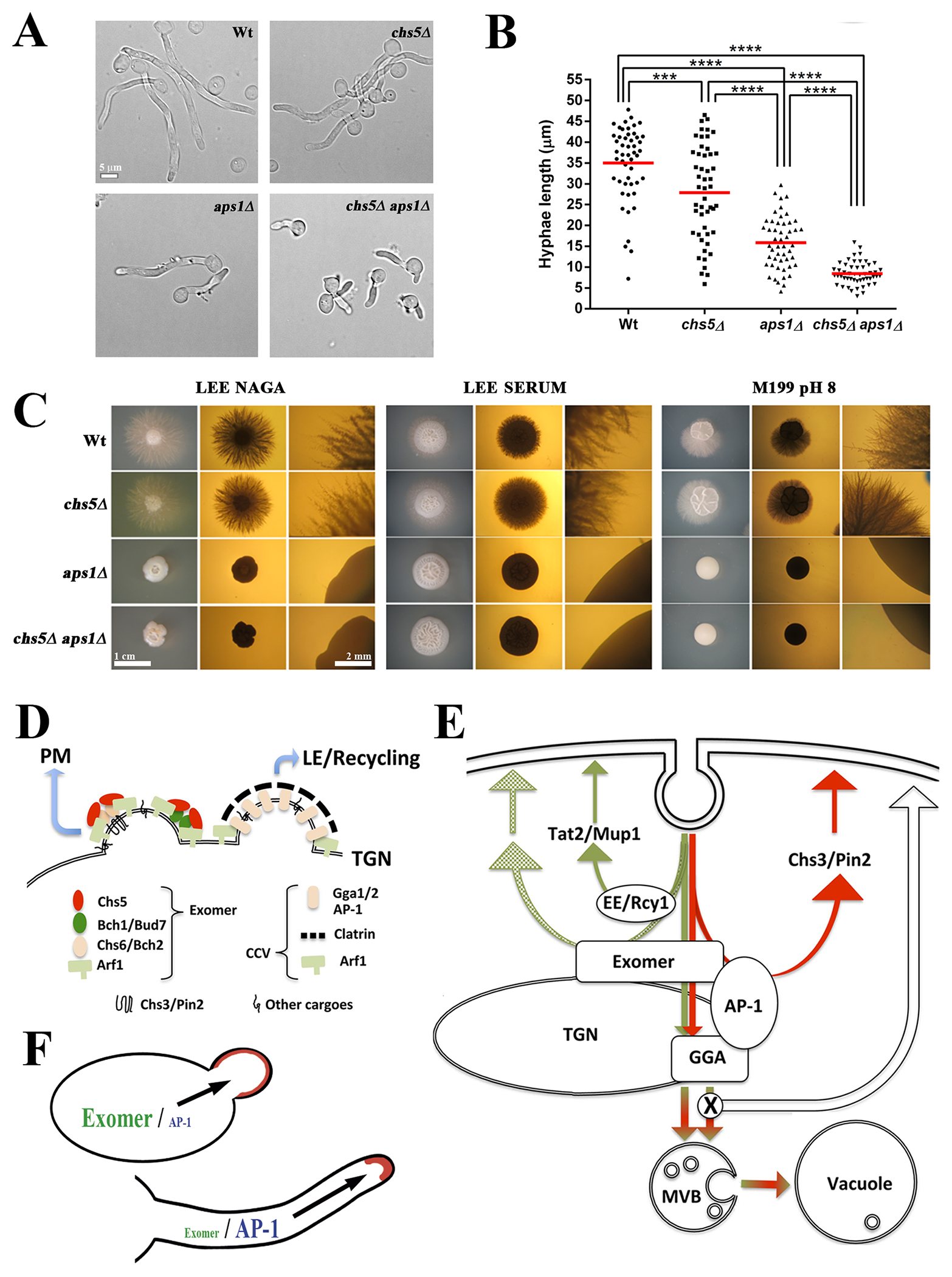

Exploring the physiological relationship between the exomer and AP-1 complexes in Candida albicans.

These multiple lines of evidence support the idea of a TGN niche in where exomer and AP-1 complexes maintain competitive and regulated relationships between themselves and with respect to their cargoes. Thus, we sought to analyze whether these relationships have been conserved along evolution. Considering the evolutionary distribution of the exomer complex (65), we decided to analyze this relationship in Candida albicans where both complexes exist. Given the effect of exomer on polarized exocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we examined filamentous growth which strongly depends on polarized exocytosis. We examined the filamentous growth of cells lacking exomer and AP-1 in liquid (Figure 7A,B) and on different solid media (Figure 7C). Surprisingly, loss of exomer only weakly affected filamentous growth whereas the AP-1 complex was indispensable for hyphal formation on solid media and its absence strongly reduced the rate of hyphal growth in liquid media. However, exomer deletion only partially altered the morphology of filaments growing on solid and in liquid media, and slightly reduces hyphal growth in liquid media. Interestingly, the double mutant showed additive phenotypes, with stronger alterations in colony morphology and a lower hyphal extension rate in liquid media. These results highlight the significant differences between the role of the exomer and AP-1 complexes in yeast or hyphal cells, and suggest that the AP-1 complex has an important role in maintaining polarity during mycelial growth.

Figure 7.

Exomer and clathrin adaptors in protein sorting: implications of exomer and AP-1 relationship in Candida albicans physiology and a model for TGN sorting. (A) C. albicans cells of the indicated strains were induced for filamentation at 37ºC in filamentation media (YEPD, 80 mg/L uridine and 10 % fetal bovine serum). Images were acquired after 2 hours of growth. (B) Quantification of the length of the hyphae in the experiment shown in A. (C) C. albicans filamentation in different solid media. Individual cells were plated onto the indicated filamentation media and incubated for 3–4 days at 37ºC. Images were acquired with a stereomicroscope with upper (left panel) or lower (central and right panels) illumination. Right panels present images with a higher amplification to show the details of filamentation (scales 1cm and 2mm). Note the absence of hyphae in the aps1∆ and aps1∆ chs5∆ mutants under all conditions tested. All tested strains are diploids and homozygous for the indicated genes. (D) Exomer and CCV are assembled at nearby localizations of the TGN and share a requirement for Arf1-GTPase activity. Exomer assembles as different complexes with different properties and facilitates the anterograde delivery of multiple proteins to the PM. CCV vesicles facilitate the late endosomal traffic of several proteins, affecting their recycling. (E) Exomer is required for the transport to the PM of a limited set of proteins that interact with both the exomer and AP-1 complexes (red lines). The anterograde traffic and the recycling of these bona fide exomer cargoes strictly depend on the coordinated action of both exomer and AP-1, a distinctive characteristic of S. cerevisiae cells. By contrast, exomer has a more general role in protein sorting at the TGN region that facilities polarized delivery of multiple proteins to the PM, independent of Rcy1-mediated recycling (green lines). In addition, exomer contributes to the correct assembly of the clathrin adaptor complexes, thereby, facilitating the proper late endosomal traffic of multiple proteins through the vacuole. Disruption of these clathrin adaptor complexes allows the transit of all these proteins to the PM by alternative pathways. PM: plasma membrane, TGN: trans-Golgi network; MVB: multi vesicular body. (F) A diagram showing the differential role of the exomer and AP-1 complexes in the polarized growth of fungi depending on how cells grow as yeasts or as hyphae.

DISCUSSION

Exomer facilitates the polarized delivery of several proteins to the PM.

The TGN is a major platform for the intracellular sorting of proteins where anterograde and recycling pathways converge (3, 66). Surprisingly, even in yeast, the mechanisms for protein sorting to the PM remain unclear (2). Some years ago, the discovery of exomer as an adaptor complex at the TGN, required for the delivery of Chs3 to the PM (17, 21), opened a pathway to study these mechanisms. However, the number of proteins that depend on exomer for their transport is limited, this observation was striking given the evolutionary maintenance of this sophisticated machinery. Moreover, the phenotypes of mutants lacking exomer, as well as the range of its genetic interaction, suggested additional roles in protein trafficking (21, 42).

The characterization of the sensitivity of exomer mutants to ammonium ((21) and this work) expands the previously reported role of exomer in protein traffic regulation. Here, we have shown that the ammonium sensitivity of exomer mutants is linked to the absence of the unique scaffold Chs5 or the pair of ChAPs Bch1/Bud7, but not to the absence of the other pair of ChAPs Chs6/Bch2, which has been described as cargo adaptor for the Chs3 and Pin2 proteins (22, 23). This suggests additional functions for exomer containing Bch1/Bud7 that are independent of the cargo binding ChAPs.