Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are tiny (20–24 nucleotides long), non-coding, highly conserved RNA molecules that play a crucial role within the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression via sequence-specific mechanisms. Since the miRNA transcriptome is involved in multiple molecular processes needed for cellular homeostasis, its altered expression can trigger the development and progression of several human pathologies. In this context, over the last few years, several relevant studies have demonstrated that dysregulated miRNAs affect a wide range of molecular mechanisms associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a common gastrointestinal disorder. For instance, abnormal miRNA expression in IBS patients is related to the alteration of intestinal permeability, visceral hyperalgesia, inflammatory pathways, and pain sensitivity. Besides, specific miRNAs are differentially expressed in the different subtypes of IBS, and therefore, they might be used as biomarkers for precise diagnosis of these pathological conditions. Accordingly, miRNAs have noteworthy potential as theragnostic targets for IBS. Hence, in this current review, we present an overview of the recent discoveries regarding the clinical relevance of miRNAs in IBS, which might be useful in the future for the development of miRNA-based drugs against this disorder.

Keywords: MicroRNAs, Irritable bowel syndrome, Gastrointestinal diseases, Gene regulation, Biomarker, Therapeutics

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID), currently called disorders of gut–brain interactions (DGBIs). According to Rome IV criteria, IBS is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain, related to defecation, and associated with changes in stool form and/or stool frequency [1–4]. Beyond gastrointestinal symptoms, IBS patients usually have a reduced quality of life associated with both chronic (e.g., fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue) and psychological (e.g., anxiety disorders and depression) conditions [5, 6]. Further, compelling evidence indicates that IBS patients avoid daily activities, including work, exercise, travel, eating, leisure, sexual intercourse, and socializing [7, 8]. Suicidal ideation has also been linked with IBS due to the unavailability of proper treatments, symptom severity, and daily life disruption [9, 10]. Globally, IBS affects 1 in 10 people [2]; however, its prevalence varies depending on the geographical region, e.g., Egypt (7.6%), Russia (5.9%), South Africa (5.9%), the United States (5.3%), Bangladesh (4.6%), China (2.3%), Japan (2.2%), Singapore (1.3%), and India (0.2%) [11].

Although the pathophysiological mechanisms that trigger IBS are still elusive, several advances in this research arena have proved that food intolerance, enteric infections, anxiety, depression, stress, sleep disorders, and microbiota are some of the factors involved in the development of this disease [12–15]. Lately (in 2021), the results of a relevant inquiry suggested that IBS patients might be predisposed to developing gastrointestinal symptoms in response to the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the gastrointestinal tract due to alterations in sensorimotor function [16]. To discriminate IBS cases according to predominant stool pattern, IBS has been classified into four subgroups: IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D, which is more common in the male sex); IBS with constipation (IBS-C, which is predominant in the female sex); IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M); and IBS unclassified (IBS-U), which involves cases that do not meet the criteria from the other three categories [4, 17–19].

To date, the diagnosis of IBS is mainly based on the Rome diagnostic criteria; however, this method lacks precision since it is tough to classify healthy controls relative to IBS patients according to these standards. Under this premise, biomarkers might represent potential tools to develop accurate diagnosis protocols for IBS that could help to differentiate among the different subgroups of IBS, as well as from other intestinal diseases [20–22]. Besides, current treatments for the different subclassifications of IBS comprise selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antispasmodics, peppermint oil, tricyclic antidepressants, opioid agonists, probiotics, antibiotics, bile salt sequestrants, among others [23]. However, most of these treatments mainly focus on symptom relief and have not shown long-lasting effectiveness [5, 24]. In this concern, it has been proposed that a better comprehension of the epigenetic mechanisms behind the pathology of IBS could be beneficial to develop novel therapeutic approaches and diagnostic procedures for this disease [25].

In this regard, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been described as notable master regulators of gene expression with emerging roles within the treatment and diagnosis of several multifactorial ailments, such as child neuropsychiatric disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, parasite-specific diseases, hair loss disorders, metabolic diseases, chronic pediatric diseases, cancer, bone diseases, and COVID-19 [26–34]. MiRNAs are small (20 to 24 nucleotides long), single-stranded, non-coding RNAs that act as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression by binding to the 3′-untranslated regions (3’-UTR) of their target mRNAs and prevent protein production by inducing cleavage or translational inhibition [35]. These small RNA molecules were described for the first time (1993) in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans [36], and this discovery has led to the identification of more than 17,000 miRNAs in at least 142 species, among which are Homo sapiens (humans) [37].

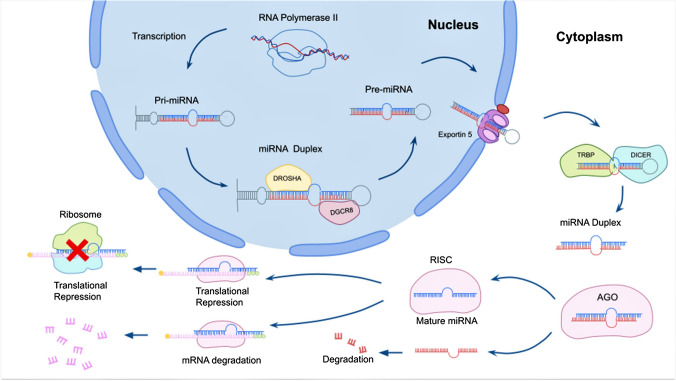

The biogenesis of miRNAs begins inside the nucleus when the transcription of primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) is carried out by RNA polymerase II (POL II). Subsequently, the pri-miRNAs are processed to form stem-loop/hairpin pre-miRNAs by a protein complex constituted by RNase III (DROSHA) and an RNA binding protein named DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8 (DGCR8). They are exported outside the nucleus by Exportin-5 (XPO5) [38, 39]. Afterward, pre-miRNAs bind to the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) endoribonuclease/transactivation response (TAR) RNA binding protein (DICER/TRBP) complex, which cleaves the hairpin and produces an RNA duplex of approximately 22 base pairs [38]. Finally, the guide strands of mature miRNAs are preferentially integrated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) together with the Argonaute protein AGO2 to attain the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression and the component 3 promoter of the RISC (C3PO) degrades the passenger strands [38, 40]. The biogenesis pathway of miRNAs is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The biogenesis of miRNAs starts in the nucleus, where the RNA Polymerase II transcribes the miRNA gene to generate the pri-miRNA. Subsequently, the pri-miR is cleaved by the microprocessor complex made up of Drosha and DGCR8 proteins, generating a pre-miRNA. This pre-miRNA is then transported to the cytoplasm by XPO5, where the RNAse III enzyme Dicer leads further processing with the RNA binding protein TRBP and protein kinase RNA activator (PACT) to generate the miRNA duplexes isolated by a helicase enzyme. Finally, the guide strand of the miRNA duplex is loaded into the RISC, together with the AGO protein, to target mRNAs by a sequence complementary recognition and cause gene silencing via mRNA degradation or translational repression

It has been demonstrated that human miRNAs regulate approximately 60% of protein-coding genes associated with several cellular processes, and their altered expression can lead to the development of a wide range of human pathologies [41–44]. Besides, miRNAs are present in the extracellular environment (e.g., plasma, serum, blood, saliva, and urine) as circulating miRNAs (which might be transported in exosomes) and in specialized tissues. Remarkably, circulating miRNAs are highly stable within extracellular fluids, and hence, they are considered promising biomarkers for human ailments [45–47]. In this context, several recent investigations have been made to understand the molecular crosstalk between the miRNA transcriptome and the mechanisms that promote intestinal diseases [48], including IBS [49]. Predominantly, miR-29a/b, miR-24, miR-510, miR-212, miR-150, miR-342-3p, miR-199a, miR-125b-5p, miR-16, miR-144, miR-200a, miR-214, and miR-103 are proposed as the potential theragnostic targets for IBS [25, 50–52]. Moreover, some differentially expressed miRNAs (e.g., miR-342-3p and miR-663b) could be helpful to accurately diagnose the diverse subtypes of IBS [53]. Likewise, the variations between the different transcriptomic profiles of mRNAs and miRNAs that occur during intestinal diseases could simplify their proper diagnosis. For instance, it has been proposed that the differential expression of mRNAs and miRNAs may assist in distinguishing between ulcerative colitis (UC) and IBS [54].

Besides, it is worth mentioning that miRNA-based therapeutics could offer great advantages over chemical drugs and DNA therapy. Firstly, miRNAs, unlike chemotherapeutic compounds, are endogenous molecules in human cells that have all the systems for processing and downstream targeting in place [55]. Secondly, a set of functionally linked genes in a pathway can be targeted by manipulating the expression of a single miRNA, which is far more effective than standard DNA therapy or drug therapy [56]. In this context, numerous miRNAs are believed to influence different intestinal pathways in IBS patients, resulting in multiple epigenetic and genetic events such as chronic inflammation [50]; this fact indicates that miRNAs are notable therapeutic targets for the management of IBS. Thirdly, miRNAs offer the advantages of being obtained through various feasible techniques, being stable in tissues and circulation, and being quickly measured using real-time PCR or microarrays [57]. Last but not least, miRNAs play a pivotal role in gut cellular processes, both physiological and pathological, and their regulatory involvement in the expression of numerous proteins indicates that these molecules could be useful in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of DGBIs, including IBS [58].

Accordingly, illustrating the regulatory role of miRNAs during IBS initiation and progression will serve as a springboard for developing new therapies and diagnostic tools for IBS. Therefore, in this current review, we discuss the experimental evidence that has been reported throughout the last few years in studies associated with the potential use of miRNAs as theragnostic targets for IBS to strengthen this research arena. Furthermore, we provide an overview of the concerns that should be addressed in future investigations to design miRNA-based therapeutic strategies for the IBS.

Functional Implications of miRNAs in IBS and Their Clinical Potential

Barrier Functions, Intestinal Permeability and miRNAs

Tight junction (TJ) proteins are found at epithelial, endothelial, and myelinated cell tight junctions. The importance of this multiprotein junctional complex lies in the fact that it regulates the movement of ions, water, and solutes through the paracellular pathway [59, 60]. Diverse reports have shown that miRNAs regulate the expression of TJ proteins, which are essential for controlling intestinal epithelial barrier functions [61]. Under this premise, Martínez et al. [62] discovered that the lessened expression of hsa-miR-125b-5p and hsa-miR-16 in small bowel mucosa contributes to the atypical upregulation of two TJ protein-coding genes, i.e., cingulin (CGN) and claudin-2 (CLDN2), leading to bowel dysfunction and altered barrier function in patients with IBS-D.

To provide more evidence about this miRNA-based gene regulation, an intestinal epithelial cell model was used to mimic the IBS-D condition by inducing the downregulated expression of hsa-miR-16 and hsa-miR-125b-5p as well as the upregulation of CLDN2 and CGN, and consistently, functional disruption of the epithelial barrier was observed in the studied tissues [62]. The same group of researchers also showed that the ultrastructural abnormalities in the epithelial barrier of IBS patients might be associated with mast cell activation. Mastocytes are plentiful within the intestines, and when activated, they communicate with nearby cells, such as neuronal, epithelial, and other types of immunological cells [63]. Besides, mental and emotional stress exacerbates allergic mast cell activation [64]. Interestingly, a positive correlation between mast cell numbers and expression of CGN and CLDN2 proteins and a negative correlation with their respective targeting miRNAs were also shown [62].

This study also indicated that patients with higher stress levels have major mast cell counts; this might cause the corresponding miRNAs to be expressed at a lower level, resulting in greater target protein expression and a disrupted barrier. However, the precise mechanism that associates mast cells, miRNAs/targets dysregulation, and the development of IBS symptoms needs further elucidation [62]. Later, another study demonstrated that miR-29a could have a role in the pathogenesis of IBS-D by downregulating tight junction protein ZO-1 and claudin-1 (CLDN1) expression (proteins that are implicated in paracellular permeability of the intestinal barrier), thus implying that miR-29a is a key regulator of intestinal barrier function and a potential therapeutic target for IBS-D [65].

Further, miR-29a is a member of the miR-29 family, which has been reported to be associated with IBS [66]. Additionally, it is well established that increased intestinal permeability is a key factor in IBS since increased intestinal permeability enables bacteria and antigens to move through the gut's mucosal layer. As a consequence, these factors trigger mucosal immune responses, thus provoking persistent diarrhea and abdominal pain in IBS patients [67]. In this regard, Zhou et al. [68] assessed the permeability of the intestinal membrane in nineteen IBS-D patients and ten controls and evaluated miRNA expression in blood microvesicles, small bowel, and colon tissues. Their results revealed that the overexpression of miR-29a in colon tissues, small bowel, and blood microvesicles reduced the occurrence of its target, i.e., glutamate-ammonia ligase (GLUL), which is associated with the tissue localization by catalyzing ATP-dependent conversion of glutamate and ammonia into glutamine [69]. These outcomes support that miR-29a could serve as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for IBS since its expression regulates intestinal permeability through the glutamine-dependent mechanism interactions between miR-29a and GLUL gene [68].

Subsequently, it was demonstrated that miR-29a/b could also increase intestinal permeability in patients with IBS-D by targeting nuclear factor-κB-repressing factor (NKRF) and CLDN1, whose primary functions are the regulation of the formation of impermeable intestinal barriers [70]. Interestingly, the silencing of the expression of the miR-29a/b cluster overturns intestinal hyperpermeability, and hence, this fact may represent a revolutionary approach to manage IBS in patients with high intestinal permeability [70]. In a further investigation, Chao and colleagues [71] stated that increased membrane permeability in IBS-D rats might be affected by the downregulation of some aquaporins (i.e., AQP1, AQP3, and AQP8) targeted by miR-29a, which play an essential role in the transportation of water in the colon and the composition of the intestinal mucosal barrier.

Mahurkar-Joshi and colleagues [72] analyzed colonic mucosal biopsies of twenty-nine IBS patients (15 IBS with IBS-C and 14 with IBS-D) to identify differentially expressed miRNAs within those tissues. Results revealed that miR-219a-5p and miR-338-3p were significantly downregulated in patients with IBS. Besides, it was observed that the inhibition of miR-219a-5p augmented intestinal epithelial cells’ permeability, while transepithelial electrical resistance was decreased and dextran flux was boosted. On the other hand, miR-338-3p inhibition triggered alterations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway genes that regulate several cellular processes related to intracellular responses, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and motility [73]. In summary, the altered expression of miR-219a-5p and miR-338-3p in IBS might be implicated in permeability and visceral nociception during IBS, thus representing potential therapeutic targets for this disease [72].

Recently (in 2021), it has been acknowledged that serum exosomes from IBS patients own elevated levels of miR-148b-5p. Consequently, researchers cultured HT-29 cells with such exosomes and observed that miR-148b-5p became upregulated in the treated cells, thus increasing cell permeability and lessening the expression of its direct target regulator of G protein signaling 2 (RGS2), a polypeptide associated with intestinal inflammation and visceral pain. These outcomes suggest that serum-derived exosomes from IBS patients may enhance colonic epithelial permeability through the interaction between miR-148b-5p and RGS2, and hence, they represent therapeutic targets for IBS [74].

Visceral Conditions and miRNAs

It is worth mentioning that miR-199 regulates hyperalgesia by targeting pathways triggered by the transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 (TRPV1) [75]. In this context, Zhou et al. [76] detected the decreased expression of miR-199a/b in patients with IBS-D linked to visceral pain. Likewise, researchers also noticed that reduced miR-199a expression in the dorsal root ganglion and colon tissue of rats was related to increased visceral hypersensitivity. Therefore, the induced upregulation of miR-199a reduced visceral discomfort by inhibiting TRPV1 signaling in vivo. Furthermore, TRPV1, the target of miR-199, has been previously associated with visceral sensitivity and mechanically induced sensations. As a result, miR-199 could be an attractive therapeutic candidate for treating visceral pain during IBS [76].

Additionally, Hou et al. [77] reported that the downregulation of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) and serotonin transporter (SERT), mediated by miR-200a, may cause visceral hyperalgesia, worsening or contributing to the development and progression of IBS-D in rats. Indeed, miR-200a might be a regulator of visceral hypersensitivity, suggesting that it could be used to treat IBS-D. Moreover, it has been noticed that IBS patients can experience visceral hypersensitivity or visceral hyperalgesia, which might cause abdominal pain [78]. To demonstrate the influence of miR-29a in visceral hyperalgesia, Zhu et al. [79] examined its expression in the intestinal biopsies of IBS patients, and they observed that miR-29a plays a key role in visceral hyperalgesia regulating the expression of one of its targets, the serotonin receptor 7 (HTR7), which is implicated in the regulation of sleep circadian rhythms and mood [80]. Therefore, a detailed molecular study of miR-29a-HTR7 interaction might provide a potential therapeutic strategy to manage hypersensitivity in IBS [79].

Furthermore, Fei and Wang [81] revealed that the overexpression of miR-495 ameliorated visceral sensitivity in IBS-D mice via targeting protein kinase inhibitor beta (PKIB) and thus inhibiting the phosphatidylinositol 3‑kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signaling pathway (which can be activated by the abnormally upregulated PKIB). Therefore, miR-495 is a clinical target that should be thoroughly explored in the following years to develop miRNA-based drugs for IBS-D. Later, the outcomes of a study in which the clinical efficacy of acupuncture for IBS-D management indicated that this therapeutic approach promotes the expression of miR-199 in the colon, diminishes the activation of TRPV1 and ameliorates visceral hypersensitivity [82]. Notwithstanding, these results should be validated in forthcoming studies to ensure the reliability of this therapy.

Inflammatory Conditions and miRNAs

A preliminary study in which blood samples of 43 participants, involving 12 IBS patients and 31 healthy controls, were analyzed, confirming that miR-150 and miR-342-3p were upregulated in patients suffering from IBS [83]. In addition, the outcomes of this investigation suggested that miR-150 is linked to inflammatory bowel condition and discomfort since this miRNA regulates a protein kinase (i.e., AKT serine/threonine kinase 2, AKT2) involved in inflammation pathways, especially within the PI3K/AKT pathway. On the other hand, miR-342-3p was predicted to target transcripts involved in colonic motility, pain signaling, and smooth muscle function, particularly calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C (CACNA1C) [83]. Nevertheless, further studies with larger samples are necessary to establish the relevance of this miRNA and its potential to be used as a biomarker. Remarkably, the upregulation of miR-150 and miR-342-3p in IBS patients was later confirmed using a protocol based on multiplexed high-throughput gene expression platform [53]. In particular, miR-342-3p was detected to be significantly upregulated in patients with IBS-D and IBS-C [53].

Another investigation detected that miR-510 is downregulated in post-infectious IBS colonic mucosal tissues and inversely correlated with the expression levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [84]. Contrary to this, the induced overexpression of this miRNA promoted the improvement of Caco-2 cells that suffered lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory injury. In this same study, researchers also discovered that the target of miR-510 is peroxiredoxin-1 (PRDX1), and the suppression of miR-510 in Caco-2 cells augmented the inflammatory damage of LPS due to the upregulation of PRDX1. These outcomes suggest that miR-510 represents a novel therapeutic target for IBS management that deserves further analysis [84].

Moreover, Ji et al. [85] noticed that miR-181c-5p was downregulated, whereas interleukin 1α (IL1A, which is involved in cellular progress and inflammatory process) expression was increased in IBS rats. Thereafter, they demonstrated that the overexpression of miR-181c-5p inhibited low-grade inflammation in IBS rats by targeting IL1A and decreasing the expression of TNF-α, interleukin-2 (IL-2), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Therefore, miR-181c-5p could be used to design miRNA-based drugs for IBS in the future.

Cellular Remodeling of Gastrointestinal Cells and miRNAs

Over the last years, a variety of studies have elucidated that miRNAs have an important role in the remodeling process of gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells (SMCs), enteric neurons, immune cells, and gastrointestinal pacemaking cells, which in turn are associated with the functional attributes, phenotype and pathophysiological mechanisms of the gastrointestinal tract [55, 86]. For instance, Park et al. [87] showed that SMC-specific Dicer knockout mice manifested severe dilatation of the intestinal tract, diminished contractile motility in the intestine, and downregulated smooth muscle contractile genes and transcriptional modulators. Such results indicated that the phenotype of SMCs is regulated by the molecular crosstalk between SMC miRNAs, serum response factor (SRF), and additional transcriptional factors. As well, this group of researchers stated that SMC miRNAs are crucial for SMCs development, persistence, and remodeling in the gastrointestinal tract [87].

Corroborating with the aforementioned study, Park et al. [88] carried out an experiment that elucidated that the phenotype of gastrointestinal SMCs is controlled by SRF-dependent SMC miRNAs that modulate the occurrence of SRF (miR-199a-3p and miR-214), myocardin (MYOCD, regulated by miR-145), and erythroblast transformation-specific (ETS) domain-containing protein Elk-1 (ELK1; regulated by miR-143, miR-145, and miR-214). The outcomes of an additional study indicated that SRF-induced expression of miR-143 and miR-145 fostered gastrointestinal SMC differentiation and inhibition of proliferation. Besides, the silenced expression of SRF in Srf knockout SMCs repressed the occurrence of SRF-dependent miRNAs, stimulating the expression of apoptotic proteins that triggered SMC death [89].

Another investigation revealed that a high-fat diet could induce apoptosis in enteric neuronal cells, slowing colonic transit. This effect was associated with miR-375, which was also linked with the decreased expression level of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (Pdk1), a protein involved in cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. Accordingly, miR-375 could be a therapeutic target to improve enteric neuron survival and gastrointestinal motility [90]. Altogether, these observations enlight some of the major pathophysiological mechanisms of the gastrointestinal tract, which are implicated in IBS.

miRNAs and Other Biological Implications in IBS

An initial study carried out by Kapeller et al. [91] demonstrated that IBS-D is linked to the variant c.*76G > A (rs62625044) in the 3′-UTR of the serotonin receptor 3E (HTR3E) gene, which, in fact, alters the binding site of miR-510 in female British and German populations. However, additional analyses are required to clarify why the c.*76G > A variant seems to have a gender-specific effect. Afterward, Zhang et al. [92] reported that the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs56109847 could be involved in developing IBS-D in the South Chinese Han female population since it impedes the proper miRNA binding of miR-510 to its target gene (i.e., HTR3E) and hence promotes its overexpression. Besides, downregulation of miR-510 could increase the risk of developing IBS-D due to the fact that this altered miRNA expression promotes higher expression levels of the serotonin receptor 3 (specifically the HTR3E receptor); accordingly, this miRNA may be used as a biomarker for IBS-D. Researchers also found that miR-510 expression is lower in the colonic mucosal tissues of patients with IBS-D than healthy controls. On the other hand, the HTR3E protein expression level was upregulated in colonic tissues of IBS-D patients [92].

In addition, Tao et al. [93] reported that the circulating miR-29b, as well as miR-106b and miR-26a, were upregulated in type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients with IBS-D. These researchers pointed out that the aforesaid miRNAs might be involved in the MAPK signaling pathway; nevertheless, further studies are required to elucidate their precise roles in developing T2D with IBS-D. In 2018, the results of an investigation unveiled that three miRNAs were significantly dysregulated in patients with different subtypes of IBS. These miRNAs were miR-145 (downregulated in IBS-C), miR-148-5p (upregulated in IBS-D), and miR-592 (downregulated in IBS-D). Subsequently, the altered expression of the aforesaid miRNAs was linked with the estrogen-dependent local intestinal modulation of the immune response [94].

Moreover, different investigations have demonstrated that intestinal microbiota plays a significant role in IBS progression [95, 96]. In this regard, an investigation performed by Mansour et al. [97] revealed that patients with different subtypes of IBS had an increased amount of coliforms and decreased expression levels of serum miR-199b, thus showing that there is a negative correlation between these factors during IBS. According to preceding studies, researchers suggested that the reduced miR-199b expression causes Notch signaling anomalies that influence T and B cell activity, limiting innate immunological responses against commensal bacteria in the gut microbiota [97].

During the last few years, many miRNAs have been shown to be associated with the pathological mechanisms that contribute to the development and progression of IBS. For example, a microarray-based study showed that 23 miRNAs were upregulated, and 1 (hsa-miR-204-5p) was downregulated in patients with IBS-D. Likewise, hsa-miR-18b-5p, hsa-miR-29b-1-5p, hsa-miR-3121-3p, and hsa-miR-5003-3p were detected to be upregulated in IBS-C patients [98]. Moreover, researchers observed that among the identified miRNAs, 14 were associated with regulating calcium ion channels, 7 with neurotransmitter release (e.g., hsa-miR-18b-5p, hsa-miR-204-5p, hsa-miR-3121-3p, and hsa-miR-3158-3p), and 2 with pain sensitivity (hsa-miR-5580-3p and hsa-miR-1323). Consequently, these differentially expressed miRNAs might contribute to the progression of IBS; nonetheless, more investigations are required to discover their gene targets and precise functional implications [98].

The results of an investigation carried out by Liao et al. [99] demonstrated that miR-24 is significantly upregulated in the epithelial cells of intestinal mucosa of patients and mice with IBS. Besides, since the target of miR-24 is SERT, its miRNA-based regulated expression impedes serotonin reuptake and promotes the progression of IBS. Accordingly, researchers treated IBS mice with a miR-24 inhibitor that induced the upregulation of SERT and ameliorated both intestinal pain and inflammation. Additionally, Wohlfarth et al. [100] demonstrated that serotonin receptor 4 (HTR4) expression is modulated by the SNP c.*61 T > C or low expression levels of miR-16 and miR-103. Accordingly, miRNA-profiling indicated that both miR-16 and miR-103 were downregulated in the jejunum of IBS-D patients and that these miRNAs were associated with the symptoms of this subtype of IBS. As well, it was elucidated that the levels and functions of HTR4 receptors may be affected by a non-coding cis-regulatory variation in HTR4, leading to an IBS phenotype with diarrhea symptoms in carriers. Moreover, the SNP (rs201253747) c.*61 T > C inside the gene HTR4 was shown to be more prevalent in IBS-D patients; it impacts miR-16, miR-103, and miR-107 binding sites within the HTR4b/i isoforms, potentially impairing the expression of HTR4. These observations imply that HTR4, miR-16, miR-103, and miR-107 play a role in developing IBS-D [100].

Later, the outcomes of another inquiry revealed that miR-490-5p is implicated within the progression of IBS since it regulates mast cell proliferation and apoptosis, and this miRNA is upregulated in IBS-D patients. Besides, mRNA expression levels of mast cell tryptase and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) were increased after downregulating miR-490-5p in p815 mast cells. However, the precise target gene that associates miR-490-5p with IBS pathology remains elusive; therefore, further experiments are necessary to unveil this target gene to develop innovative miRNA-based therapies for IBS [101]. An additional relevant study elucidated that miR-10b-5p plays a fundamental role in diabetes and gastrointestinal dysmotility by regulating the Krueppel-like factor 11-tyrosine kinase receptor (KLF11-KIT) pathway; however, this miRNA was shown to be downregulated in intestinal cells of Cajal of diabetic mice [102]. In this context, since altered gut motility is involucrated within the pathophysiology of IBS [103], restoration of miR-10b-5p expression levels could represent a feasible approach for IBS treatment [102].

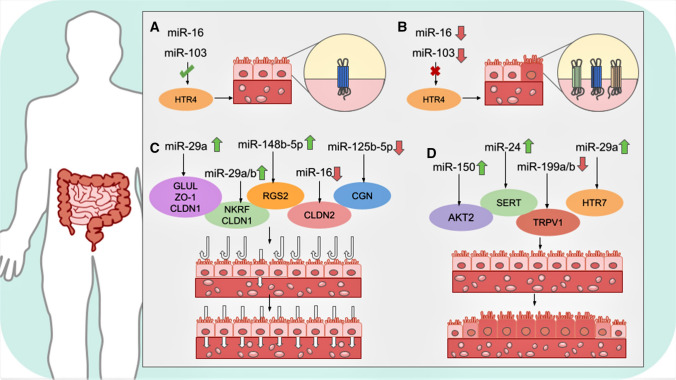

Guo et al. [104] detected that miR-135a-5p, miR-148a-3p, miR-149-5p, miR-190a-5p, miR-575, and miR-1305 were significantly upregulated in IBS-D patients, while miR-127-5p and miR-194-5p were substantially downregulated. Intriguingly, it was also observed that acupuncture could decrease or improve IBS-D symptoms by downregulating miR-148a-3p through several mechanisms, and hence, further analyses are required to confirm the clinical potential of acupuncture for IBS treatment. Some of the most relevant functional implications of miRNAs within IBS are depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the effect of some miRNAs on IBS. A. Healthy cells present normal expression levels of serotonin receptors. B. Dysregulated miRNA expression and affected miRNA binding sites alter serotonin receptor regulation, resulting in IBS symptoms. C. Alteration of permeability and deficiency of barrier function in intestinal cells due to upregulation/downregulation of certain miRNAs. D. Inflammation of intestinal cells produced by aberrantly expressed miRNAs produces pain and discomfort

Potential Use of miRNAs as Biomarkers for IBS

Yang et al. [105] examined the miRNA profile of white hair, black eye (WHBE), and Japanese white (JW) IBS rabbits. Their results evidenced that let-7f-5p, let-7 g-5p, let-7i-5p, miR-24-3p, miR-29a-3p, miR-126-3p, miR-192-5p, miR-221-3p, and miR-130b-3p were upregulated in WHBE IBS rabbits, whereas miR-132 and miR-324-3p were downregulated in the same group of rabbits. On the other hand, let-7i-5p, miR-29a-3p, miR-126-3p. and miR-192-5p were significantly upregulated solely in JW IBS rabbits, while miR-132, miR-223-3p, and miR-324-3p were downregulated in this group. Interestingly, the expression levels of let-7f-5p, miR-24-3p, miR-126-3p, miR-130b-3p, and miR-221-3p were superior in WHBE IBS rabbits than in JW IBS rabbits; this fact deserves further exploration since it could be related to an increased sensitivity to IBS [105].

In another study, scientists detected that miR-23a and miR-181b were upregulated in serum samples of IBS and colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. However, no statistically significant differences were detected in the expression pattern of such miRNAs in both diseases, thus implying that upcoming investigations should focus on clarifying the cut-off limits to properly diagnose IBS and CRC based on these biomarkers [106]. In a case–control study involving 130 patients (i.e., 33 with CRC, 37 with UC, 30 with IBS, and 30 healthy controls), Ahmed Hassan et al. [107] found that miR-92a was present in plasma samples isolated from IBS patients; nevertheless, the expression levels of this miRNA were significantly higher in CRC and UC patients. Thus, miR-92a could be a promising biomarker to discriminate between CRC and UC patients and between UC and non-UC patients (IBS and controls), but not for the prognosis or diagnostic of IBS itself. Since no previous research on the relationship between miR-92a and IBS has been performed, the pathophysiological role of this miRNA on IBS is still unclear, and more investigations are needed to understand its functional implication within the progression of this syndrome [107]. Table 1 lists some of the most important roles of miRNAs involved in the pathophysiology of IBS.

Table 1.

Clinical implications of miRNAs within the pathophysiology of the different subtypes of IBS

| General functional implication | miRNA | miRNA regulation | Target | Specific biological role | Type of sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrier functions, intestinal permeability and miRNAs | miR-16 | Downregulated | CLDN2 | Barrier function | Small bowel mucosa | [62] |

| miR-125b-5p | Downregulated | CGN | Barrier function | Small bowel mucosa | ||

| miR-29a | Upregulated | ZO-1 and CLDN1 | Regulation of intestinal barrier function | Human intestinal mucosal epithelia | [65] | |

| miR-29a | Upregulated | GLUL | Regulation of intestinal permeability | Blood microvesicles, small bowel and colon tissues | [68] | |

| miR-29a | Upregulated | AQP1, AQP3, and AQP8 | Regulation of intestinal permeability | Colonic epithelial cells from IBS rats | [71] | |

| miR-29a/b | Upregulated | NKRF and CLDN1 | Regulation of intestinal permeability | Intestinal tissues | [70] | |

| miR-148b-5p | Upregulated | RGS2 | Regulation of colonic epithelial permeability | Serum exosomes | [74] | |

| miR-219a-5p | Downregulated | – | Intestinal permeability and visceral nociception | Colonic mucosal biopsies | [72] | |

| miR-338-3p | Downregulated | – | Intestinal permeability and visceral nociception | Colonic mucosal biopsies | ||

| Visceral conditions and miRNAs | miR-29a | Upregulated | HTR7 | Visceral hyperalgesia | Intestinal biopsies | [79] |

| miR-199 | Upregulated (due to acupuncture) | TRPV1 | Visceral hypersensitivity | Colonic tissue | [82] | |

| miR-199a/b | Downregulated | TRPV1 | Visceral pain | Biopsies from the ascending, transverse, and descending colon | [76] | |

| miR-200a | Upregulated | CNR1 and SERT | Visceral hyperalgesia | Distal colon tissues from IBS-D rats | [77] | |

| miR-495 | Downregulated | PKIB | Visceral sensitivity | Mouse rectal tissue | [81] | |

| Inflammatory conditions and miRNAs | miR-150 | Upregulated | AKT2 | Inflammatory bowel condition and discomfort | Blood | [53, 83] |

| miR-342-3p | Upregulated | CACNA1C | Colonic motility, pain signaling, and smooth muscle function | Blood | ||

| miR-181c-5p | Downregulated | IL1A | Low-grade inflammation | Colon tissues of IBS rats | [85] | |

| miR-510 | Downregulated | PRDX1 | LPS-induced inflammatory damage | Post-infectious IBS colonic mucosal tissues | [84] | |

| Cellular remodeling of gastrointestinal cells and miRNAs | miR-199a-3p | Downregulated | SRF | Regulation of gastrointestinal SMC phenotype | SMCs | [88] |

| miR-214 | Downregulated | SRF | ||||

| miR-145 | Downregulated | MYOCD | ||||

| miR-143 | Downregulated | ELK1 | ||||

| miR-145 | Downregulated | ELK1 | ||||

| miR-214 | Downregulated | ELK1 | ||||

| miR-143 | Downregulated | SRF | SMC differentiation and proliferation | SMCs | [89] | |

| miR-145 | Downregulated | SRF | ||||

| miR-375 | Upregulated | Pdk1 | Enteric neuron survival and gastrointestinal motility | Enteric neurons | [90] | |

| Other biological implications in IBS | miR-10b-5p | Downregulated | KLF11 | Diabetes and intestinal dysmotility | Interstitial cells of Cajal | [102] |

| miR-24 | Upregulated | SERT | Pain and inflammation | Intestinal mucosa epithelial cells of IBS patients and mice | [99] | |

| miR-26a | Upregulated | – | Involved in the MAKP signaling pathway | Plasma | [93] | |

| miR-29b | Upregulated | – | Involved in the MAKP signaling pathway | Plasma | ||

| miR-106b | Upregulated | – | Involved in the MAKP signaling pathway | Plasma | ||

| miR-145 | Downregulated in IBS-C | – | Estrogen-dependent local intestinal modulation of immune response | Colon mucosa | [94] | |

| miR-148-5p | Upregulated in IBS-D | – | Colon mucosa | |||

| miR-592 | Downregulated in IBS-D | – | Colon mucosa | |||

| miR-16 | Downregulated | HTR4 | IBS-D symptoms | Jejunal mucosal biopsies | [100] | |

| miR-103 | Downregulated | HTR4 | IBS-D symptoms | Jejunal mucosal biopsies | ||

| miR-199b | Downregulated | – | Increased number of coliforms | Serum | [97] | |

| miR-490-5p | Downregulated | – | Regulation of mast cell proliferation and apoptosis | p815 mast cells | [101] | |

| miR-510 | Downregulated | HTR3E | Increased IBS-D risk | Colonic mucosal tissue | [92] | |

| miR-135a-5p | Upregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | [104] | |

| miR-148a-3p | Upregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | ||

| miR-149-5p | Upregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | ||

| miR-190a-5p | Upregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | ||

| miR-575 | Upregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | ||

| miR-1305 | Upregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | ||

| miR-194-5p | Downregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | ||

| miR-127-5p | Downregulated | – | IBS-D symptoms | Serum | ||

| Biomarkers | miR-23a | Upregulated | – | – | Serum | [106] |

| miR-181b | Upregulated | – | – | Serum |

Conclusions

Over the past years, different investigations have enlightened the fact that there is a significant association between the miRNA transcriptome and the molecular pathophysiology of IBS. As discussed throughout the manuscript, the outcomes that have been obtained in this research arena are encouraging; for instance, it has been demonstrated that the dysregulated expression of miRNAs is associated with the altered manifestation of genes implicated in different events that occur during IBS, such as anomalous intestinal permeability, visceral hyperalgesia, visceral pain, inflammation, and pain sensitivity. Furthermore, differentially expressed miRNAs among the diverse subtypes of IBS and other intestinal disorders might contribute to properly differentiating and identifying these human ailments using miRNAs as biomarkers. Therefore, the evidence presented herein could help to pave the way for developing effective miRNA-based treatments and diagnostic protocols for IBS. However, the limited information about the functional implications of miRNAs in IBS indicates that additional inquiries are required to acknowledge the clinical significance of these master regulators of gene expression in the development and progression of IBS and other intestinal diseases.

Future Perspectives

The information presented in this current review elucidates that the research arena regarding the relationship between the miRNA transcriptome and IBS has grown in the last decade. However, molecular biologists are working tirelessly to develop miRNA-based treatments and diagnoses for IBS. Nonetheless, this field of study is still at an early stage of development, and more investigations are required to understand the underlying genetic etiology and functional implications of miRNAs during IBS. For example, as previously discussed, it is well established that serotonin deficiency is a key factor that affects the prevalence of IBS [108]. Accordingly, forthcoming studies should thoroughly explore the potential therapeutic applications of those miRNAs that target SERT, especially miR-24 and miR-200a, whose regulatory functions have been validated in intestinal epithelial cells [109].

Likewise, a wide range of functions triggered by serotonin (e.g., gut motility, visceral sensation, neuronal signaling of the gut–brain axis, secretion, and absorption) are mediated by 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors [55, 110], and IBS symptoms can be handled with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists [111]; thus, more research is required to comprise the miRNA-based regulation of gene expression of such receptors. Besides, the impact of SNPs on these modulatory functions needs to be addressed in the future since the functional implications of certain miRNAs, such as miR-16, miR-103, miR-107, and miR-510, are altered due to SNPs [55]. In addition, P2Y1, P2Y2, and TRPV1 receptors have been linked with visceral hypersensitivity and abdominal pain during IBS [112–115], and hence, forthcoming research should be focused on identifying and validating those miRNAs that can target the mRNAs coding for these receptors; under this premise, miR-199 has a great potentiality for the treatment of IBS via regulating TRPV1 expression [75, 76, 82].

On the other hand, a number of studies have shown that gut microbiota is associated with the pathophysiology of IBS and; consequently, prebiotics, probiotics, specific diets, and symbiotics are proposed as promising therapies for this intestinal disease [116–118]. However, the molecular crosstalk between the miRNA transcriptome and gut microbiota in IBS remains unknown, and scientists should address this concern in the future. In this regard, previous studies have demonstrated that a variety of miRNAs, including miR-223, miR-155, miR-150, miR-143, among others, participate in miRNA-microbiota interactions within the intestines [61]. Remarkably, the aforesaid miRNAs, as well as miR-18a*, miR‑146a, miR‑20a‑5p, miR‑183‑5p, miR‑206‑3p, and additional miRNAs, are influenced by gut microbiota and may affect the pathophysiology of intestinal diseases [119]. Furthermore, plant-derived miRNAs might modulate gut microbiota, thus having an important influence on host health [120]. Gut microbiota could also affect intestinal permeability and hence have an impact on plant xenomiR absorption [121]. Consequently, assessing the associations between intestinal microbiota and miRNAs (endogenous and exogenous) during IBS could be favorable for developing novel medications for this disorder.

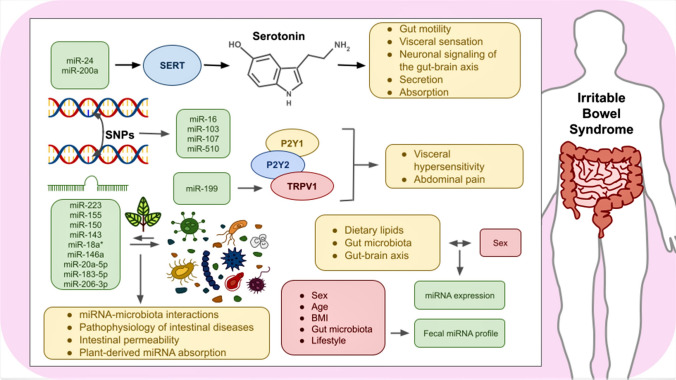

In addition, several reports have stated that miRNA expression is affected by a variety of factors, such as age, sex, and lifestyle (i.e., physical activity, diet, alcohol consumption, and smoking) [122–124]. In this respect, data from relevant reports indicated that the fecal miRNA profile is related to sex, age, body mass index (BMI), gut microbiota, and lifestyle. Remarkably, stool may represent a source of non-invasive biomarkers for diagnosing gastrointestinal disorders [125, 126]. The observations of another study indicated that sex has an impact on intestinal miRNA expression when consuming dietary lipids [127]. Moreover, miRNA expression in the gut–brain axis might be modulated by the gut microbiome in a sex-dependent manner [128]. Thus, these factors should be considered throughout the examination of the potential clinical applications of miRNAs in IBS (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Potential implications of miRNAs in IBS. As depicted, a wide variety of miRNAs are involved in regulating serotonin transporter, P2Y1, P2Y2, and TRPV1 receptors, and gut microbiota, thus being promising targets for their thorough study within the development of IBS. As well, SNPs, miRNA-microbiota interactions, and plant-derived miRNAs own prospective implications in IBS pathophysiology. Besides, certain factors, including sex, age, BMI, gut microbiota, and lifestyle, have been linked with both fecal and intestinal miRNA profile, and hence further inquiries should be focused on clarifying the clinical significance of these variables in IBS

Finally, it is worth mentioning that in the last few years, the design of miRNA-based drugs has had outstanding progress, and specialized pharmacological companies have emerged to evaluate their clinical applications (e.g., miRagen Therapeutics Inc., Regulus Therapeutics, Santaris Pharma, and Mirna Therapeutics Inc.) [129, 130]. In fact, a few of these promising medicines have been entered into either preclinical or clinical trials. Some examples of such drugs are miravirsen and RG-101 (for hepatitis C virus); lademirsen (for Alport syndrome); RG-125 (for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease); MRX34, mesomiR-1, and cobomarsen (for a variety of cancers); MGN-2677 (for vascular disease), MGN-5804 (for cardiometabolic disease); and MRG-110 (for skin excisional wound) [131–133]. Nonetheless, there is no miRNA-based approach for IBS in clinical trials.

Nevertheless, a number of considerations should be taken into account during the designing of miRNA-based drugs for IBS management. For instance, miRNA administration might prompt the activation of immune responses through interactions with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which identify pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and mediate immunogenicity. Therefore, different strategies have been suggested to deal with this issue, such as using phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) to avoid the interaction between small RNAs and PRRs, applying routine administration of limited doses of miRNA-based medications over a prolonged period (analogous to metronomic chemotherapy), and combining RNA therapeutics with other clinical approaches (e.g., radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy) [134].

On the other hand, to enhance the specificity of miRNA-mediated IBS treatments, as well as to avoid off-target and undesirable on-target effects, cell-specific miRNA modulation technique by expressing the miRNA employing a vector under the regulation of a promoter overexpressed in the target cell should be used [134]. Apart from the above, difficulties in delivering miRNA-based drugs specifically to target organs have hindered the advancement of these therapeutic approaches [135]. Thus, the design of systems that allow the efficient delivery of miRNA drugs for IBS should guarantee the integral arrival of these therapeutic molecules to the intestinal tissues. Such delivery systems might comprise plant-derived edible nanoparticles, bovine milk extracellular vesicles, or human extracellular vesicles [136–138].

Consequently, for miRNA-based drugs targeting IBS to reach pharmacological insight, several obstacles must be handled hereafter, including the development of efficient delivery systems, assessment of large sample sizes, regulated diets, the assurance of the absence of adverse immune effects, and the execution of toxicity analyses, as well as pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. Thus, we consider that the information presented in this review will support further research into the functional implications of miRNAs within IBS to establish a therapeutic outline for clinical trials.

Author’s contribution

LABV, SujayP conceived, performed the literature search, and wrote the manuscript. IMR, LDMG, JRM, FISC performed the literature search and contributed to writing the manuscript. SP, AntaraB, AB, AKD critically revised the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2020;396:1675–1688. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black CJ, Ford AC. Global burden of irritable bowel syndrome: trends, predictions and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:473–486. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What Is New in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:151–163. doi: 10.5056/jnm16214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasant DH, Paine PA, Black CJ, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2021;70:1214–1240. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Silva A, MacQueen G, Nasser Y, et al. Yoga as a Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:2503–2514. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05989-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gracie DJ, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Longitudinal impact of IBS-type symptoms on disease activity, healthcare utilization, psychological health, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:702–712. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballou S, McMahon C, Lee HN, et al. Effects of Irritable Bowel Syndrome on Daily Activities Vary Among Subtypes Based on Results From the IBS in America Survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2471–2478.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eswaran S, Chey WD, Jackson K, et al. A Diet Low in Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, and Monosaccharides and Polyols Improves Quality of Life and Reduces Activity Impairment in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1890–1899.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu J, Shi L, Huang D, et al. Depression and Structural Factors Are Associated With Symptoms in Patients of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;26:505–513. doi: 10.5056/jnm19166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller V, Hopkins L, Whorwell PJ. Suicidal ideation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1064–1068. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:99–114.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadjivasilis A, Tsioutis C, Michalinos A, et al. New insights into irritable bowel syndrome: From pathophysiology to treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32:554–564. doi: 10.20524/aog.2019.0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creed F. Review article: the incidence and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome in population-based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:507–516. doi: 10.1111/apt.15396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black CJ, Yiannakou Y, Houghton LA, et al. Anxiety-related factors associated with symptom severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32:e13872. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadjivasilis A, Demetriou K. Microbiome and Metabolome of Patients with Slow Transit Constipation: Unity in Diversity? Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2847–2848. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aroniadis OC, Wang X, Gong T, et al. Factors Associated with the Development of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19. Dig Dis Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07286-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asano T, Tanaka K, Tada A, et al. Aminophylline suppresses stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity and defecation in irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40214. doi: 10.1038/srep40214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YS, Kim N. Sex-Gender Differences in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:544–558. doi: 10.5056/jnm18082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sultan S, Malhotra A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:ITC81–ITC94. 10.7326/AITC201706060. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kim JH, Lin E, Pimentel M. Biomarkers of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:20–26. doi: 10.5056/jnm16135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morales W, Rezaie A, Barlow G, et al. Second-Generation Biomarker Testing for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Using Plasma Anti-CdtB and Anti-Vinculin Levels. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:3115–3121. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jang DE, Bae JH, Chang YJ, et al. Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase Is a Novel Biomarker for the Interstitial Cells of Cajal in Stress-Induced Diarrhea-Dominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-4933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weaver KR, Melkus GDE, Henderson WA. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Nurs. 2017;117:48–55. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000520253.57459.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kopczyńska M, Mokros Ł, Pietras T, et al. Quality of life and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Prz Gastroenterol. 2018;13:102–108. doi: 10.5114/pg.2018.75819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahurkar-Joshi S, Chang L. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:805. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paul S, Reyes PR, Sánchez Garza B, et al. MicroRNAs and Child Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Brief Review. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:232–240. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02917-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul S, Bravo Vázquez LA, Pérez Uribe S, et al. Current Status of microRNA-Based Therapeutic Approaches in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cells. 2020;9:1698. doi: 10.3390/cells9071698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paul S, Ruiz-Manriquez LM, Serrano-Cano FI, et al. Human microRNAs in host–parasite interaction: a review. 3 Biotech. 2020;10:510. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02498-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paul S, Licona-Vázquez I, Serrano-Cano FI, et al. Current insight into the functions of microRNAs in common human hair loss disorders: a mini review. Hum Cell. 2021;34:1040–1050. doi: 10.1007/s13577-021-00540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul S, Bravo Vázquez LA, Pérez Uribe S, et al. Roles of microRNAs in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism disorders and their therapeutic potential. Biochimie. 2021;187:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2021.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul S, Ruiz-Manriquez LM, Ledesma-Pacheco SJ, et al. Roles of microRNAs in chronic pediatric diseases and their use as potential biomarkers: A review. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2021;699:108763. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2021.108763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruiz-Manriquez LM, Estrada-Meza C, Benavides-Aguilar JA, et al. Phytochemicals mediated modulation of microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs in cancer prevention and therapy. Phyther Res. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ptr.7338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bravo Vázquez LA, Moreno Becerril MY, Mora Hernández EO, et al. The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in Bone Diseases and Their Therapeutic Potential. Molecules. 2022;27:211. doi: 10.3390/molecules27010211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul S, Bravo Vázquez LA, Reyes-Pérez PR, et al. The role of microRNAs in solving COVID-19 puzzle from infection to therapeutics: A mini-review. Virus Res. 2022;308:198631. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2021.198631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangukia N, Rao P, Patel K, et al. Identifying potential human and medicinal plant microRNAs against SARS-CoV-2 3′UTR region: A computational genomics assessment. Comput Biol Med. 2021;136:104662. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dwivedi S, Purohit P, Sharma P. MicroRNAs and Diseases: Promising Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2019;34:243–245. doi: 10.1007/s12291-019-00844-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stavast CJ, Erkeland SJ. The Non-Canonical Aspects of MicroRNAs: Many Roads to Gene Regulation. Cells. 2019;8:1465. doi: 10.3390/cells8111465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, et al. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:402. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glaich O, Parikh S, Bell RE, et al. DNA methylation directs microRNA biogenesis in mammalian cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5657. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13527-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assmann TS, Recamonde-Mendoza M, de Souza BM, et al. MicroRNAs and diabetic kidney disease: Systematic review and bioinformatic analysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;477:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juźwik CA, Drake SS, Zhang Y, et al. microRNA dysregulation in neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Prog Neurobiol. 2019;182:101664. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.101664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Makarova J, Turchinovich A, Shkurnikov M, et al. Extracellular miRNAs and Cell-Cell Communication: Problems and Prospects. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46:640–651. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadri Nahand J, Moghoofei M, Salmaninejad A, et al. Pathogenic role of exosomes and microRNAs in HPV-mediated inflammation and cervical cancer: A review. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:305–320. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, et al. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542:450–455. doi: 10.1038/nature21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tölle A, Blobel CC, Jung K. Circulating miRNAs in blood and urine as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for bladder cancer: An update in 2017. Biomark Med. 2018;12:667–676. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2017-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donati S, Ciuffi S, Brandi ML. Human circulating miRNAs real-time qRT-PCR-based analysis: An overview of endogenous reference genes used for data normalization. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4353. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang C, Chen J. microRNAs as therapeutic targets in intestinal diseases. ExRNA. 2019;1:23. doi: 10.1186/s41544-019-0026-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park JH. Dysregulated MicroRNA Expression in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:166–167. doi: 10.5056/jnm16044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Q, Verne GN. miRNA-based therapies for the irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:991–995. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.577060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakov R, Snegarova V, Dimitrova-Yurukova D, et al. Biomarkers in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: biological rationale and diagnostic value. Dig Dis. 2021;40:23–32. doi: 10.1159/000516027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camilleri M, Halawi H, Oduyebo I. Biomarkers as a diagnostic tool for irritable bowel syndrome: where are we? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:303–316. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1288096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fourie NH, Peace RM, Abey SK, et al. Perturbations of Circulating miRNAs in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Detected Using a Multiplexed High-throughput Gene Expression Platform. J Vis Exp. 2016 doi: 10.3791/54693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo H, Dai J, Liu C, et al. Distinct transcriptomic signature of mRNA and microRNA in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.19.21253573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh R, Zogg H, Ro S. Role of microRNAs in Disorders of Gut-Brain Interactions: Clinical Insights and Therapeutic Alternatives. J Pers Med. 2021;11:1021. doi: 10.3390/jpm11101021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meng Z, Zhou D, Gao Y, et al. miRNA delivery for skin wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;129:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chapman CG, Pekow J. The emerging role of miRNAs in inflammatory bowel disease: A review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8:4–22. doi: 10.1177/1756283X14547360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh R, Wei L, Ghoshal UC. Micro-organic basis of functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders: Role of microRNAs in GI pacemaking cells. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2021;40:102–110. doi: 10.1007/s12664-021-01159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slifer ZM, Blikslager AT. The integral role of tight junction proteins in the repair of injured intestinal epithelium. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:972. doi: 10.3390/ijms21030972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhat AA, Uppada S, Achkar IW, et al. Tight Junction Proteins and Signaling Pathways in Cancer and Inflammation: A Functional Crosstalk. Front Physiol. 2019;9:1942. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bi K, Zhang X, Chen W, et al. MicroRNAs Regulate Intestinal Immunity and Gut Microbiota for Gastrointestinal Health: A Comprehensive Review. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:1075. doi: 10.3390/genes11091075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martínez C, Rodinõ-Janeiro BK, Lobo B, et al. miR-16 and miR-125b are involved in barrier function dysregulation through the modulation of claudin-2 and cingulin expression in the jejunum in IBS with diarrhoea. Gut. 2017;66:1537–1538. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee KN, Lee OY. The Role of Mast Cells in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:2031480. doi: 10.1155/2016/2031480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vanuytsel T, van Wanrooy S, Vanheel H, et al. Psychological stress and corticotropin-releasing hormone increase intestinal permeability in humans by a mast cell-dependent mechanism. Gut. 2014;63:1293–1299. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu H, Xiao X, Shi Y, et al. Inhibition of miRNA-29a regulates intestinal barrier function in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by upregulating ZO-1 and CLDN1. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:155. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaiopoulou A, Karamanolis G, Psaltopoulou T, et al. Molecular basis of the irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:376–383. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou Q, Zhang B, Verne GN. Intestinal membrane permeability and hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2009;146:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou Q, Souba WW, Croce CM, et al. MicroRNA-29a regulates intestinal membrane permeability in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2010;59:775–784. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.181834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vermeulen T, Görg B, Vogl T, et al. Glutamine synthetase is essential for proliferation of fetal skin fibroblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;478:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou Q, Costinean S, Croce CM, et al. MicroRNA 29 targets nuclear factor-κB-repressing factor and claudin 1 to increase intestinal permeability. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:158–169.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chao G, Wang Y, Zhang S, et al. MicroRNA-29a increased the intestinal membrane permeability of colonic epithelial cells in irritable bowel syndrome rats. Oncotarget. 2017;8:85828–85837. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mahurkar-Joshi S, Rankin CR, Videlock EJ, et al. The Colonic Mucosal MicroRNAs, MicroRNA-219a-5p, and MicroRNA-338-3p Are Downregulated in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Are Associated With Barrier Function and MAPK Signaling. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2409–2422.e19. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cargnello M, Roux PP. Activation and Function of the MAPKs and Their Substrates, the MAPK-Activated Protein Kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:50–83. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.00031-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xing Y, Xue S, Wu J, et al. Serum Exosomes Derived from Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patient Increase Cell Permeability via Regulating miR-148b-5p/RGS2 Signaling in Human Colonic Epithelium Cells. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2021;2021:6655900. doi: 10.1155/2021/6655900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou Q, Croce C, Verne G. MicroRNA-199 modulates hyperalgesia via TRPV1 dependent pathways. J Pain. 2012;13:S35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.01.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou Q, Yang L, Larson S, et al. Decreased miR-199 augments visceral pain in patients with IBS through translational upregulation of TRPV1. Gut. 2016;65:797–805. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hou Q, Huang Y, Zhang C, et al. MicroRNA-200a Targets Cannabinoid Receptor 1 and Serotonin Transporter to Increase Visceral Hyperalgesia in Diarrhea-predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Rats. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:656–668. doi: 10.5056/jnm18037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Farzaei MH, Bahramsoltani R, Abdollahi M, et al. The Role of Visceral Hypersensitivity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Pharmacological Targets and Novel Treatments. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:558–574. doi: 10.5056/jnm16001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu H, Xiao X, Chai Y, et al. MiRNA-29a modulates visceral hyperalgesia in irritable bowel syndrome by targeting HTR7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;511:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nikiforuk A. Targeting the Serotonin 5-HT7 Receptor in the Search for Treatments for CNS Disorders: Rationale and Progress to Date. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:265–275. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0236-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fei L, Wang Y. microRNA-495 reduces visceral sensitivity in mice with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome through suppression of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway via PKIB. IUBMB Life. 2020;72:1468–1480. doi: 10.1002/iub.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pei L, Chen H, Guo J, et al. Effect of acupuncture and its influence on visceral hypersensitivity in IBS-D patients: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e10877. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fourie NH, Peace RM, Abey SK, et al. Elevated circulating miR-150 and miR-342-3p in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Exp Mol Pathol. 2014;96:422–425. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Y, Wu X, Wu J, et al. Decreased expression of microRNA-510 in intestinal tissue contributes to post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome via targeting PRDX1. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:7385–7397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ji LJ, Li F, Zhao P, et al. Silencing interleukin 1α underlies a novel inhibitory role of miR-181c-5p in alleviating low-grade inflammation of rats with irritable bowel syndrome. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:15268–15279. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krishna CV, Singh J, Thangavel C, et al. Role of microRNAs in gastrointestinal smooth muscle fibrosis and dysfunction: novel molecular perspectives on the pathophysiology and therapeutic targeting. Am J Physiol - Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310:G449–G459. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00445.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Park C, Yan W, Ward SM, et al. MicroRNAs Dynamically Remodel Gastrointestinal Smooth Muscle Cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Park C, Hennig GW, Sanders KM, et al. Serum Response Factor-Dependent MicroRNAs Regulate Gastrointestinal Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:164–175. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Park C, Lee MY, Slivano OJ, et al. Loss of serum response factor induces microRNA-mediated apoptosis in intestinal smooth muscle cells. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e2011. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nezami BG, Mwangi SM, Lee JE, et al. MicroRNA 375 Mediates Palmitate-Induced Enteric Neuronal Damage and High-Fat Diet-Induced Delayed Intestinal Transit in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:473–483.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kapeller J, Houghton LA, Mönnikes H, et al. First evidence for an association of a functional variant in the microRNA-510 target site of the serotonin receptor-type 3E gene with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2967–2977. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang Y, Li Y, Hao Z, et al. Association of the Serotonin Receptor 3E Gene as a Functional Variant in the MicroRNA-510 Target Site with Diarrhea Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Chinese Women. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:272–281. doi: 10.5056/jnm15138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tao W, Dong X, Kong G, et al. Elevated Circulating hsa-miR-106b, hsa-miR-26a, and hsa-miR-29b in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:9256209. doi: 10.1155/2016/9256209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jacenik D, Cygankiewicz AI, Fichna J, et al. Estrogen signaling deregulation related with local immune response modulation in irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;471:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mishima Y, Ishihara S. Enteric Microbiota-Mediated Serotonergic Signaling in Pathogenesis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:10235. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barandouzi ZA, Lee J, Maas K, et al. Altered Gut Microbiota in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Its Association with Food Components. J Pers Med. 2021;11:35. doi: 10.3390/jpm11010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mansour MA, Sabbah NA, Mansour SA, et al. MicroRNA-199b expression level and coliform count in irritable bowel syndrome. IUBMB Life. 2016;68:335–342. doi: 10.1002/iub.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Guo XW, Zhang FC, Liang LX, et al. A microarray analysis of microRNAs profiles in irritable bowel syndrome. FASEB J. 2014;28:595.1. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.28.1_supplement.595.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liao XJ, Mao WM, Wang Q, et al. MicroRNA-24 inhibits serotonin reuptake transporter expression and aggravates irritable bowel syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;469:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wohlfarth C, Schmitteckert S, Härtle JD, et al. miR-16 and miR-103 impact 5-HT4 receptor signalling and correlate with symptom profile in irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14680. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13982-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ren HX, Zhang FC, Luo HS, et al. Role of mast cell-miR-490-5p in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:93–102. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Singh R, Ha SE, Wei L, et al. miR-10b-5p Rescues Diabetes and Gastrointestinal Dysmotility. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1662–1678.e18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wei L, Singh R, Ro S, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Underpinning the symptoms and pathophysiology. JGH Open. 2021;5:976–987. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Guo J, Lu G, Chen L, et al. Regulation of serum microRNA expression by acupuncture in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Acupunct Med. 2022;40:34–42. doi: 10.1177/09645284211027892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang QQ, Xu XP, Zhao HS, et al. Differential expression of microRNA related to irritable bowel syndrome in a rabbit model. J Dig Dis. 2017;18:330–342. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chira A, Muresan MS, Braicu C, et al. Serum patterns of mir-23a and mir-181b in irritable bowel syndrome and colorectal cancer—A pilot study. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2020;20:254–261. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2019.4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hassan EA, El-Din Abd El-Rehim AS, Mohammed Kholef EF, et al. Potential role of plasma miR-21 and miR-92a in distinguishing between irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, and colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2020;13:147–154. doi: 10.22037/ghfbb.v13i2.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bruta K, Vanshika, Bhasin K, et al. The role of serotonin and diet in the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Transl Med Commun. 2021;6:1. doi: 10.1186/s41231-020-00081-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Manzella C, Singhal M, Ackerman M, et al. Serotonin transporter untranslated regions influence mRNA abundance and protein expression. Gene Rep. 2020;18:100513. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2019.100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Coates MD, Tekin I, Vrana KE, et al. Review article: the many potential roles of intestinal serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) signalling in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:569–580. doi: 10.1111/apt.14226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Iwasaki M, Akiba Y, Kaunitz JD. Duodenal Chemosensing of Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Implications for GI Diseases. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:35. doi: 10.1007/s11894-019-0702-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Luo Y, Feng C, Wu J, et al. P2Y1, P2Y2, and TRPV1 Receptors Are Increased in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome and P2Y2 Correlates with Abdominal Pain. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2878–2886. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Perna E, Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Florens MV, et al. Effect of resolvins on sensitisation of TRPV1 and visceral hypersensitivity in IBS. Gut. 2021;70:1275–1286. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wu J, Cheng Y, Zhang R, et al. P2Y1R is involved in visceral hypersensitivity in rats with experimental irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6339–6349. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhao J, Li H, Shi C, et al. Electroacupuncture Inhibits the Activity of Astrocytes in Spinal Cord in Rats with Visceral Hypersensitivity by Inhibiting P2Y1 Receptor-Mediated MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathway. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2020;2020:4956179. doi: 10.1155/2020/4956179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pittayanon R, Lau JT, Yuan Y, et al. Gut Microbiota in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome—A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:97–108. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rodiño-Janeiro BK, Vicario M, Alonso-Cotoner C, et al. A Review of Microbiota and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Future in Therapies. Adv Ther. 2018;35:289–310. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pimentel M, Lembo A. Microbiome and Its Role in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:829–839. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Li M, Chen WD, Wang YD. The roles of the gut microbiota–miRNA interaction in the host pathophysiology. Mol Med. 2020;26:101. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00234-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Spinler JK, Oezguen N, Runge JK, et al. Dietary impact of a plant-derived microRNA on the gut microbiome. ExRNA. 2020;2:11. doi: 10.1186/s41544-020-00053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]