Summary

The Japanese government implemented a large-scale vaccination policy against the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, primarily using messenger RNA vaccines in 2021. Its hallmark was prioritized vaccination for the elderly after healthcare workers in a short period of time. Vaccination for the elderly, vulnerable to infection and severe disease, was carried out rapidly in approximately 4 months since April 2021. We evaluated the impact of Japan's vaccination policy against COVID-19 during the pandemic, with a particular focus on how prioritized vaccination for the elderly affected the pandemic. We observed a remarkable decrease in the number of infections, cluster events in long-term care facilities, and severe disease among the elderly during the fifth wave (August 2021) despite rising incidence of infections in the overall population. In conclusion, we think that prioritized vaccination for the elderly was efficacious in preventing infections and severe COVID-19 among the elderly during the fifth wave in Japan.

Keywords: vaccination policy, pandemic, messenger RNA vaccines

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused a pandemic since its emergence at the end of 2019, with Japan experienced five endemic waves during 2020 and 2021. No treatment was known for this infectious disease until various protocols were developed, including vaccination. In 2021, the Japanese government implemented a large-scale vaccination policy using messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines (1). The highest priority group for vaccination included healthcare workers who provide medical care for patients with COVID-19, followed by the elderly aged ≥ 65 years. Japan rapidly achieved approximately 80% coverage with two-dose vaccinations among the elderly from April to the end of July in 2021 (2), which was completed in the early stage of the fifth wave. With limited medical resources (3), it is important to review how this vaccination strategy helped control the spread of infection. However, there is a paucity of reports on the impact of prioritized vaccination on the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan.

In this study, we aimed to discuss the impact of the prioritized vaccination policy against COVID-19 during the pandemic in Japan, with a particular focus on how prioritized vaccination for the elderly affected the situation.

Materials and Methods

W'e analyzed open data on COVID-19 published by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, including the number of new infections, severe cases, and cluster events (4). We determined the number of infections using the Vaccination Record System data published by the Digital Agency of the Japanese government (5). We also used the latest population estimates published by the Statistics Bureau of Japan to estimate vaccination rates (6).

Based on the age categories in these data sources, for new infections and severe cases, patients aged ≥ 70 years were regarded as the elderly, whereas for vaccination rate, patients aged ≥ 65 years were regarded as the elderly. Regarding the epidemic curves of COVID-19 in Japan in 2021, we defined the third, fourth, and fifth waves as substantial increases in the number of infections, occurring primarily in January, May, and August, respectively (7).

The need for ethical approval was waived in accordance with the guidelines of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine Ethics Committee.

Results and Discussion

The Japanese government started a vaccination program for healthcare workers on February 17, and a prioritized large-scale vaccination program for approximately 36 million elderly people started on April 12, 2021.

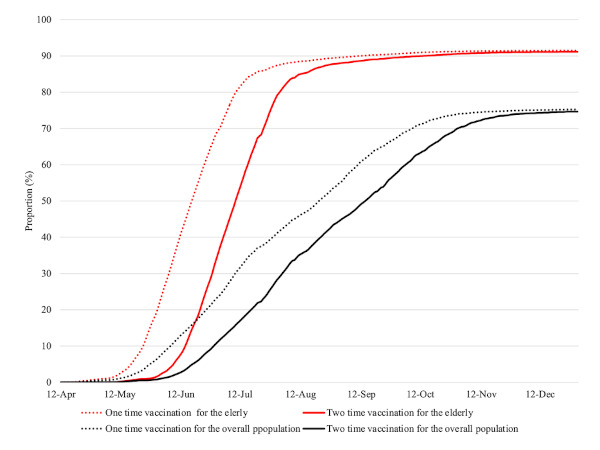

Figure 1 illustrates the vaccination rate in the elderly and the overall population from April 12 to December 31, 2021. The two-dose vaccination rate among the elderly was 79.1% on July 31, whereas the rate for overall population was 28.3%. Finally, two-dose vaccination rate for the elderly was 91.1% by the end of December.

Figure 1.

Changes in vaccination rate for COVID-19 over time in 2021. The red dotted and solid lines represent one-and two-dose vaccination rates for the elderly, respectively. The black dotted and solid lines represent the one-and two-dose vaccination rates for the overall population, respectively.

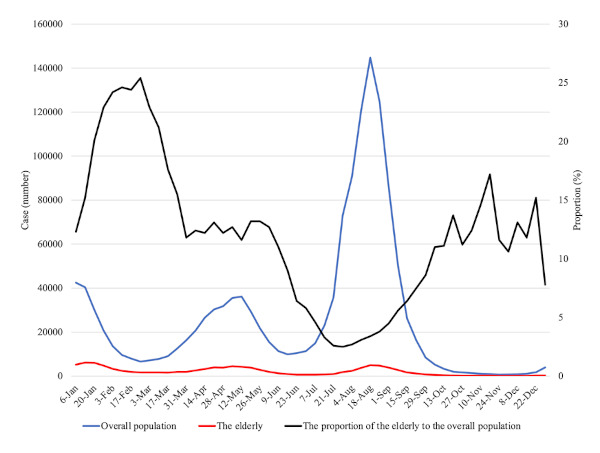

Figure 2 shows a comparison of weekly counts of newly confirmed patients over time between patients aged ≥ 70 years and all patients. In the middle of the third wave, the proportion of weekly new infections in patients aged ≥ 70 years reached 25.4%. However, it decreased sharply from June with a minimum of 2.5% in the fifth wave. This trend continued until the late stage of the fifth wave, when the overall number of infections radically decreased.

Figure 2.

Number of newly confirmed COVID-19 patients over time in 2021. The blue and red lines represent the number of infections in the overall population and those aged ≥ 70 years, respectively. The black line represents the proportion of elderly patients among all patients.

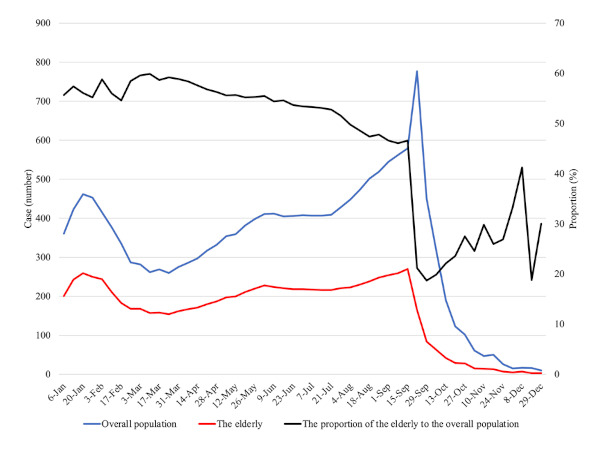

Figure 3 shows the change in weekly severe cases of COVID-19 in patients aged ≥ 70 years and in all patients. Despite the increase in the number of severe cases in all patients since mid-September 2021, the proportion of severe cases in patients aged ≥ 70 years declined from 46.6% in mid-September to 18.7% in early-October.

Figure 3.

Number of severe diseases of COVID-19 over time in 2021. The blue and red lines represent the number of severe COVID-19 cases among the overall population and those aged ≥ 70 years, respectively. The black line represents the proportion of elderly patients among all patients. Patients with severe COVID-19 were defined as those who were on a ventilator or on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or were treated in an ICU.

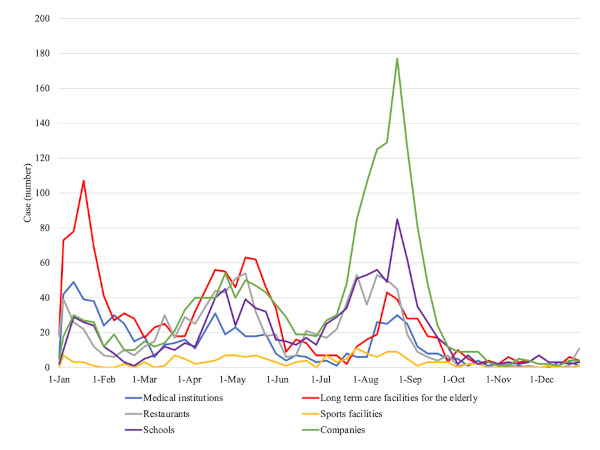

Figure 4 presents the number of outbreaks by facility type in 2021. In the third and fourth waves of January and May 2021, long-term care facilities (LTCFs) for the elderly were facilities with the highest proportion of cluster events. In contrast, during the fifth wave in August, schools and offices had the highest number of cluster events, whereas there were relatively few cluster events in LTCFs for the elderly.

Figure 4.

Number of cluster events by different types of facilities over time in 2021. The red, blue, violet, gray, yellow, and green lines represent cluster events in the long-term care facilities for the elderly, medical institutions, schools, restaurants, sports facilities, and companies, respectively.

In Japan, vaccination of the elderly, who are vulnerable to infection, was accomplished in approximately 4 months. In the subsequent fifth wave, large differences were noted in immunization coverage among generations. The proportion of the elderly among the newly confirmed patients and patients with severe disease was low and the number of cluster events in LTCFs was small. On the other hand, increased spread of infection was noted among the younger populations. Based on these disparities in epidemics among generations in the fifth wave and comparison of the fifth wave to previous waves in terms of infections among the elderly, we believe that prioritized vaccination for the elderly is largely responsible for the decline in the incidence of infection in the elderly.

Japan's Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency reviews new drugs, and the Minister of Health, Labor, and Welfare grants final approval. The Pfizer- BioNTech mRNA vaccine was approved on February 14, 2021, and both the Moderna mRNA vaccine and the Oxford/Astra Zeneca vaccines were approved on May 21, 2021 (8). Subsequently, the Japanese government made mRNA vaccines the mainstay of large-scale vaccination.

Healthcare workers who provide medical care for COVID-19 were given the highest vaccination priority. Next, the elderly (people aged ≥ 65 years) were regarded as the second-priority group for vaccination. Large-scale vaccination centers were established in each area to prepare for mass vaccination within a short period of time (9). In addition, LTCFs for the elderly were registered as satellite facilities for vaccine administration.

Older age is a risk factor for severe COVID-19, and various comorbidities in the elderly are associated with severe disease. A high incidence of severe disease in patients aged ≥ 65 years was reported in the first and second waves in Japan (10). Our previous study, which used multicenter registry data that included patients up to the third wave, showed that the proportion of severe disease and death increased with age among the elderly (11). Additionally, the number and size of clusters in LTCFs were associated with increased mortality due to COVID-19 (12). Japan is a country with a super-aged population. The average life expectancy in 2019 ranked highly worldwide: 87.4 years for women; and 81.4 years for men (13). The proportion of the elderly population is the highest worldwide, at 28.7%. Additionally, 950,000 people received services from LTCFs in 2019 (14). Therefore, reducing the risk of infection and severe COVID-19 in the elderly has become a critical issue in Japan.

Given the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, prioritizing limited vaccine resources was a major issue. A variety of ethical aspects must be considered in vaccine prioritization (15). Vaccines can not only prevent the direct health problems associated with diseases but also reduce the accompanying socioeconomic losses. Equity for different groups of people should also be considered. However, prioritizing vaccine distribution to protect more disadvantaged groups is a fundamental issue. In the United States, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) advised the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to prioritize COVID-19 vaccines. The ACIP recommended that healthcare personnel and residents of LTCFs be offered vaccination in the initial phase 1a of the COVID-19 vaccination program (16). Elderly populations and people with underlying diseases were given second priority for phases 1b and 1c. The strategy for prioritizing vaccination against COVID-19 in Japan was determined through discussions within the Committee on Vaccination Basic Policy of the Inoculation and Vaccination Working Group of the Health Science Council at the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (17). Its main purpose is to reduce the risk of severe diseases and maintain the healthcare delivery system. Japan decided that the elderly would be the second priority for vaccination after medical personnel.

Despite the largest increase in the number of infections in the fifth wave, we observed a sharp decrease in the proportion of newly confirmed cases and severe cases among the elderly in that wave after initiating prioritized vaccination. This radical change in the epidemic curve indicates that prioritizing vaccination for more vulnerable populations in a short period, and achieving high vaccine coverage, was efficacious in handling the outbreak with limited medical resources. The proportion of newly confirmed patients among the elderly began to decline relatively early in June, along with an increase in vaccine coverage among the elderly. Additionally, the proportion of patients with severe disease among the elderly began to decline in mid- September, with a time lag of approximately 3 months. This time interval suggests that intensive vaccination over a short period can effectively control the transmission of infection. Meanwhile, it might take time to prevent severe disease, possibly due to the difficulty in treating COVID-19 in the elderly and the prolonged care needed for various complications during the clinical course.

In conclusion, prioritizing the elderly for vaccination against COVID-19 seems efficacious in reducing the number of new infection cases, severe disease, and cluster events in LTCFs among the elderly during the pandemic in Japan. This contributed to reducing the burden on healthcare facilities and making effective use of limited healthcare resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future strategies should include administration of appropriate booster shots to cope with attenuated vaccine efficacy and novel variant strains with immune escape from currently available vaccines.

Funding: This research was supported by the NCGM COVID-19 Gift Fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. NIKKEI Asia. Japan starts COVID vaccination drive: five things to know. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Japan-starts-COVID-vaccination-drive-five-things-to-know (accessed January 28, 2022).

- 2. Prime Minister's Office of Japan. Ministerial Meeting on the Progress in Countermeasures against the Novel Coronavirus Disease. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/99_suga/actions/202108/04corona.html (accessed January 28, 2022). (in Japanese) .

- 3. Kokudo N, Sugiyama H. Hospital capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob Health Med. 2021; 3:56-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Visualizing the data: information on COVID-19 infections. https://covid19.mhlw.go.jp/en/ (accessed January 28, 2022).

- 5. Digital Agency. Vaccination Record System: Vaccination status of novel corona virus. https://info.vrs.digital.go.jp/dashboard (accessed January 28, 2022). (in Japanese) .

- 6. Statistics of Japan. Population Estimates by Age (Five- Year Groups) and Sex - September 1, 2021 (Final estimates), February 1, 2022 (Provisional estimates). https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200524&tstat=000000090001&cycle=1&year=20220&month=11010302&tclass1=000001011678&tclass2val=0 (accessed January 28, 2022).

- 7. Song P, Karako T. The strategy behind Japan's response to COVID-19 from 2020-2021 and future challenges posed by the uncertainty of the Omicron variant in 2022. Biosci Trends. 2022; 15:350-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters. Basic policy for countermeasures against novel coronavirus infections. https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/novel_coronavirus/th_siryou/kihon_r_040218.pdf (accessed January 28, 2022). (in Japanese) .

- 9. Ministry of Defense. SDF large-scale vaccination centers in Tokyo and Osaka. https://www.mod.go.jp/en/article/2021/05/d767c5209c1b9599a7b77d877b44b226d435fd9c.html (accessed January 28, 2021).

- 10. Saito S, Asai Y, Matsunaga N, Hayakawa K, Terada M, Ohtsu H, Tsuzuki S, Ohmagari N. First and second COVID-19 waves in Japan: A comparison of disease severity and characteristics. J Infect. 2021; 82:84-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asai Y, Nomoto H, Hayakawa K, Matsunaga N, Tsuzuki S, Terada M, Ohtsu H, Kitajima K, Suzuki K, Suzuki T, Nakamura K, Morioka S, Saito S, Saito F, Ohmagari N. Comorbidities as risk factors for severe disease in hospitalized elderly COVID-19 patients by different age-groups in Japan. Gerontology. 2022; 1-11. doi: 10.1159/000521000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iritani O, Okuno T, Hama D, Kane A, Kodera K, Morigaki K, Terai T, Maeno N, Morimoto S. Clusters of COVID-19 in long-term care hospitals and facilities in Japan from 16 January to 9 May 2020. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020; 20:715-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Life expectancies at birth in some countries. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/lifetb19/dl/lifetb19-03.pdf (accessed January 28, 2022). (in Japanese) .

- 14. Report on Long-Term Care Insurance Operation (2021). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/kaigo/osirase/jigyo/19/dl/r01_point.pdf (accessed January 28, 2022). (in Japanese) .

- 15. Persad G, Peek ME, Emanuel EJ. Fairly prioritizing groups for access to COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA. 2020; 324:1601-1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, McClung N, Chamberland M, Lee GM, Talbot HK, Romero JR, Bell BP, Oliver SE. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Updated Interim Recommendation for Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021; 69:1657-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Committee on Vaccination Basic Policy of the Inoculation and Vaccination Working Group of the Health Science Council. The 45th meeting. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/shingi-kousei_127714.html (accessed January 28, 2022). (in Japanese) .