Abstract

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) is an emerging standard for diagnosing and prognosing prostate cancer, but ~ 20% of clinically significant tumors are invisible to mpMRI, as defined by the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2 (PI-RADSv2) score of one or two. To understand the biological underpinnings of tumor visibility on mpMRI, we examined the proteomes of forty clinically significant tumors (i.e., International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Grade Group 2)—twenty mpMRI-visible and twenty mpMRI-invisible, with matched histologically normal prostate. Normal prostate tissue was indistinguishable between patients with visible and invisible tumors, and invisible tumors closely resembled the normal prostate. These data indicate that mpMRI-visibility arises when tumor evolution leads to large-magnitude proteomic divergences from histologically normal prostate.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13045-022-01268-6.

Keywords: Proteomics, Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging, Prostate cancer

To the Editor,

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) has dramatically enhanced the management of localized prostate cancer, providing an opportunity to improve diagnosis and risk stratification while simultaneously reducing unnecessary and risky needle biopsies [1]. However, because ~ 20% of clinically significant tumors remain invisible to mpMRI [2], there is limited consensus on when a biopsy can be safely avoided upon a negative mpMRI. The reasons for prostate cancer mpMRI invisibility are largely unknown, despite mpMRI-visible tumors harboring more adverse pathological and biological features [3–6]. Within International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Grade Group 2, mpMRI visibility is associated with increased genomic instability, presence of intraductal carcinoma and/or cribriform architecture (IDC/CA) histology and hypoxia, a constellation of features termed nimbosus [3, 7]. Given the role of cellular density and perfusion in mpMRI, differences in stromal organization in non-malignant tissue [4] are hypothesized to affect water diffusion and thus mediate tumor microenvironmental influence on mpMRI visibility.

To understand the biological underpinnings of tumor visibility on mpMRI, we performed global proteomics on twenty mpMRI-invisible (Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2 [PI-RADSv2] 1–2) and twenty mpMRI-visible (PI-RADSv2 5) tumors, all from patients with a solitary pathological ISUP Grade Group 2 lesion larger than 1.5 cm [3]. We analyzed both tumor and adjacent histologically normal tissue (NAT) from all patients, leading to 81 proteomes (Fig. 1A, Additional file 3: Table S1). A detailed description of the methods can be found in Additional file 1: Methods (available online).

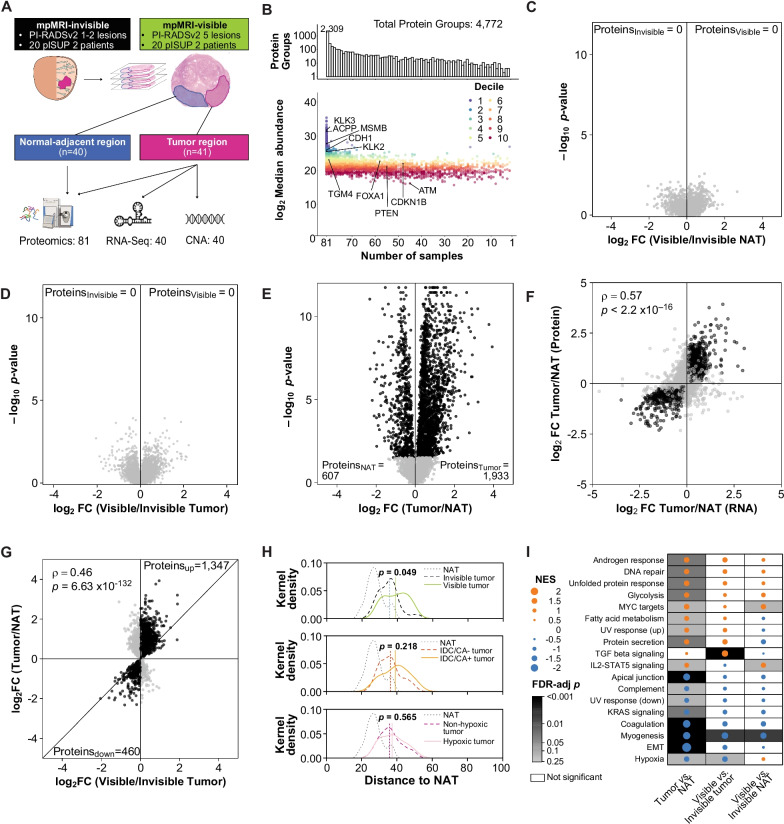

Fig. 1.

Proteomics of mpMRI visibility. A Sample outline. B Summary of quantified proteins in various number of samples. Differentially abundant proteins in mpMRI-visible (n = 20) and mpMRI-invisible (n = 20) NATs (C), mpMRI-visible (n = 21) and mpMRI-invisible tumors (n = 20) (D), and tumor (n = 40) and NAT regions (n = 40) (E). Statistically significant (FDR < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test) proteins colored in black. F Comparison of tumor/NAT in the proteome (ntumor = 40, nNAT = 40) and transcriptome (ntumor = 499, nNAT = 53). Genes that were significantly associated with tumors or NATs at both the protein and RNA levels (FDR < 0.05) are colored in black. G Associations of protein abundance changes between tumor versus NAT and mpMRI-visible tumor versus mpMRI-invisible tumor, using proteins that were significantly differentially expressed in tumor versus NAT (n = 2540). Significant (FDR < 0.05) proteins from the tumor/NAT comparison that had the same directionality in the mpMRI-visible/invisible tumor comparison are colored in black. H Distribution of Euclidean distance between each group and median protein abundance in NATs. Only proteins that were quantified in all tumor and NAT samples were used (n = 2309). IDC/CA groups were determined based on the presence of intraductal carcinoma (IDC) or cribriform architecture (CA) histology (IDC/CA+, n = 11) or not (IDC/CA−, n = 29). Hypoxia groups (n = 20 per group) were determined by median dichotomization (median Ragnum score = −1). I Gene set enrichment analysis for 3 sets of comparisons (Tumor/NAT, mpMRI-visible/invisible tumor, and mpMRI-visible/invisible NAT) using the Hallmark gene set. The union of significant terms (FDR < 0.25) are shown. The size of the dot represents the magnitude of the effect, the color denotes the direction (positive: orange; negative: blue), and background shading the FDR-adjusted p-value. Only significant associations (FDR < 0.25) have gray background. mpMRI: multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging; PI-RADSv2: Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2; pISUP: pathological International Society of Urological Pathology Grade Group; CNA: Copy number abberation; NAT: normal tissue adjacent to the tumor; FDR: Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate; FC: fold change; ρ: Spearman’s rho; p: p-value; NES: normalized enrichment score; and IDC/CA: Intraductal carcinoma or cribriform architecture

We quantified 4772 proteins (Additional file 4: Table S2), of which 2309 were detected in all 81 samples (Fig. 1B). Clustering by protein abundance yielded four protein subtypes and four sample subtypes (Additional file 2: Fig. S1A). The sample subtypes were driven by differences between tumors and NATs (Adjusted Rand Index [ARI] = 0.22, p = 0.001) and not mpMRI visibility (ARI = − 0.01, p = 0.64). The protein subtypes reflected specific biological pathways. For example, P1 genes were associated with immune response and extracellular matrix organization and were more abundant in tumors than NATs (Additional file 5: Table S3).

To test the important and widespread hypothesis that the tumor microenvironment influences visibility on mpMRI [3, 8], we compared protein abundances between NATs from patients with mpMRI-visible and mpMRI-invisible tumors. To our surprise, not a single protein differed between the two groups (Fig. 1C). Similarly, differences in the proteomes of mpMRI-visible and mpMRI-invisible tumors were also small and not statistically significant, albeit with larger effect sizes compared to the result from NATs (Fig. 1D). In contrast, we observed the expected large, statistically significant differences between the proteomes of tumors and NATs (Fig. 1E). Similarly, large differences were observed at the transcriptome level (Additional file 1: Methods, Additional file 2: Fig. S1B), where most tumor/NAT proteomic differences were corroborated (Spearman’s ρ = 0.57, p < 2.2 × 10–16, Fig. 1F).

Given these modest differences between mpMRI-visible and mpMRI-invisible tumor proteomes, we hypothesized that mpMRI-invisible tumors might reflect an intermediate state between NATs and mpMRI visibility. Consistent with this, protein abundance differences associated with tumor mpMRI visibility were correlated with NAT-tumor differences (Spearman’s ρ = 0.46, p < 1 × 10–16, Fig. 1G). These associations were diminished in the NAT proteomes (Spearman’s ρ = 0.13, p = 7.01 × 10–11, Additional file 2: Fig. S1C), and in the matched tumor transcriptomes [3] (Spearman’s ρ = 0.00, p = 0.79, Additional file 2: Fig. S1D). The proteome of mpMRI-invisible tumors was more similar to that of NATs compared to the proteome of mpMRI-visible tumors (Fig. 1H), likely contributing to their invisibility. Consistently, normoxic tumors and tumors lacking IDC/CA histology were more similar to NATs (Fig. 1H). Altered pathways in mpMRI-visible tumors vs. mpMRI-invisible tumors overlapped substantially with those distinguishing tumors from NATs (hypergeometric test p = 5.5 × 10–14, Fig. 1I). Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and myogenesis genes were enriched in mpMRI-invisible tumors compared to mpMRI-visible tumors, consistent with reports that stromal and extracellular matrix genes were enriched in mpMRI-invisible tumors [4]. mpMRI-visible tumors were enriched in pathways associated with advanced disease, including androgen response, DNA repair, and MYC and TGF-β signaling [9]. Taken together, these data help explain the aggressive clinical behavior of mpMRI-visible tumors, concordant with increased PTEN loss [10], higher Oncotype and Decipher genomic classifier scores [5], and elevated nimbosus hallmarks [3].

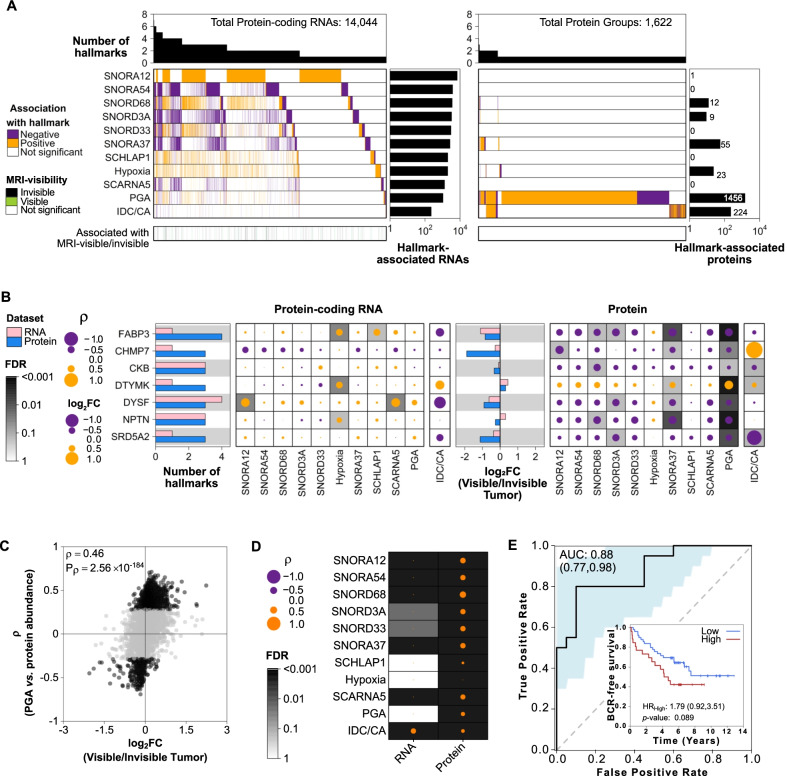

To identify protein-coding RNAs and proteins associated with mpMRI visibility and disease aggression, we next focused on the nimbosus hallmarks [3, 7] and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNA) that are associated with mpMRI visibility [3, 7]. These hallmarks were previously shown to be associated with mpMRI visibility and disease aggression at the genomic and transcriptomic level [3]. An independent discovery cohort of 144 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) intermediate-risk tumors was used to discover associations between RNA abundance and each hallmark (Additional file 1: Methods) [11, 12]. We identified 14,044 protein-coding RNAs and 1,622 proteins associated with at least one nimbosus hallmark in this cohort (Fig. 2A, Additional file 1: Methods). Proportion of the genome with a copy number aberration (PGA) and IDC/CA status showed the largest effects on the transcriptome and proteome. Proteins more abundant in mpMRI-invisible tumors were also negatively correlated with these hallmarks (Fig. 2B). Proteins associated with high PGA were preferentially associated with mpMRI visibility (hypergeometric test p = 3.3 × 10–2; Fig. 2C). mpMRI visibility was also strongly associated with aggressive hallmarks such as hypoxia, presence of IDC/CA, and SChLAP1 expression through proteins, rather than protein-coding RNAs (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Protein associations with genomic, transcriptomic, and pathological hallmarks of mpMRI visibility. A Protein-coding RNAs (left) and proteins (right) associated with hallmarks of mpMRI visibility, colored by positive (orange) or negative (purple) associations. Top barplot shows the number of hallmarks each RNA or protein was associated with. Side barplot shows the number of validated RNAs or proteins associated with each hallmark (Additional file 1: Methods). Bottom covariate bar indicates significant RNAs or proteins associated with visible (green) or invisible (black) tumors (FDR < 0.05). B Genes that were associated with three or more hallmarks or mpMRI visibility at the protein level. Left barplot shows the number of hallmarks each gene is associated with at the RNA (pink) or protein (blue) level. Dot maps show the effect size of the association between gene expression and each hallmark. The size of the dot represents the magnitude of the effect, the color denotes the direction (positive: orange; negative: purple), and background shading the FDR. Only significant associations have a gray background. Right barplot shows the log2 fold change between mpMRI-visible and invisible tumors for RNA and protein. C Spearman’s correlation between tumor protein/PGA and protein/mpMRI visibility associations. Validated proteins with abundance significantly correlated with PGA (FDR < 0.2) are colored in black. D Summary of the correlation between associations with each hallmark and mpMRI visibility in protein-coding RNAs and proteins. E A 3-protein model classified mpMRI-visible tumors with an area under the curve (AUC) of 88%. AUC confidence intervals in parentheses and shaded in blue. Inset: The protein signature was associated with worse biochemical recurrence (BCR)-free survival in an independent cohort (n = 76 patients) [11]. Low: n = 49, 20 events; High: n = 26, 15 events. PGA: proportion of the genome with a copy number abberation; IDC/CA: intraductal carcinoma or cribriform architecture; mpMRI: multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging; FDR: false discovery rate; ρ: Spearman’s rho; FC: fold change; HR: hazard ratio

Finally, we employed a machine learning approach to find proteins that best differentiate mpMRI-visible and mpMRI-invisible tumors in our cohort. Following feature selection, we created a three-protein logistic regression model (LDHB, GNA11, SRD5A2) that classified mpMRI visibility status with an AUC of 0.88 (95% CI = 0.77–0.98, Fig. 2E, Additional file 1: Methods). This model was associated with worse biochemical recurrence-free survival in an independent cohort of 76 predominantly NCCN intermediate-risk tumors (HR = 1.79, 95% CI = 0.92–3.51, p = 0.089, median follow-up 6.02 years, Fig. 2E, inset) [11], further supporting the association between proteomic determinants of mpMRI visibility and tumor aggressiveness.

These data establish that mpMRI visibility is largely independent of the molecular features of tumor-adjacent stromal cells in the prostate. Rather, the proteome of mpMRI-invisible tumors is more similar to that of normal tissues [4, 10], suggesting that mpMRI visibility reflects the degree of proteomic dysregulation. Caveats of this study include uncertain generalization beyond ISUP Grade Group 2 tumors, the Caucasian ancestry of most patients, and study of only PI-RADSv2 scores of 1–2 and 5. These data suggest that tumors are invisible to mpMRI because their proteome does not differ sufficiently from normal prostate.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1 Methods. Method details.

Additional file 2. Fig. S1. Tumor/NAT differences. A Consensus clustering of samples (n = 81, K = 4) using the top 25% most variable proteins (n = 1,193, K = 4). B Differentially abundant protein-coding RNAs in tumors and NATs from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Statistically significant genes (FDR < 0.05) are colored in black. C Associations of protein abundance changes between tumor versus NAT, and mpMRI-visible NAT versus mpMRI-invisible NAT. Only proteins that were significantly differentially expressed in tumor and NAT regions (FDR < 0.05) were used for this analysis. D Associations of protein-coding RNA abundance changes between tumor versus NAT, and mpMRI-visible tumor versus mpMRI-invisible tumor. Only protein-coding RNAs that were significantly differentially expressed in tumor and NAT regions (FDR < 0.05) were used for this analysis. Proteins or transcripts that were significant (FDR < 0.05) in the tumor-NAT comparison and had the same directionality are marked in black. NAT: histologically normal prostate adjacent to the tumor; mpMRI: multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging; FDR: Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted p-value.

Additional file 3. Table S1. Summary and characteristics of patient cohort.

Additional file 4. Table S2. Proteins quantified by mass spectrometry.

Additional file 5. Table S3. Pathway analysis of protein clusters.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the Kislinger, Boutros, and Reiter laboratories for their helpful suggestions and comments.

Abbreviations

- 95% CI

95% Confidence interval

- ARI

Adjusted Rand Index

- AUC

Area under the curve

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- IDC/CA

Intraductal carcinoma or cribriform architecture histology

- ISUP

International Society of Urological Pathology

- mpMRI

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging

- NAT

Adjacent histologically normal tissue

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- PGA

Proportion of the genome with a copy number aberration

- PI-RADSv2

Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System version 2

- snoRNA

Small nucleolar RNA

Author contributions

The corresponding authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RER, PCB, and TK initiated the project. AK, AP, SSR, AES, EF, and AS acquired the data. AK, LYL, VI, PCB, TK, and RER analyzed and interpreted the data. AK, LYL, TK, and PCB drafted the manuscript. RER, PCB, and TK supervised research. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an operating grant from the National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network (grant number 1U01CA214194-01) and a Canadian Cancer Society Impact Grant (grant number 705649) to T.K. and P.C.B. and by a CIHR Project grant (Grant Number PJT162384) to T.K, an NIH/NCI award (Grant Number P30CA016042), a Prostate Cancer Foundation Special Challenge Award to P.C.B. (Grant Number 20CHAS01). This work was made possible by the generosity of Mr. Larry Ruvo. P.C.B. was supported by CIHR operating grant (Grant Number 388344). A.K. was supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship and a Paul STARITA Graduate Student Fellowship. L.Y.L was supported by a CIHR Vanier Award. Sample collection was supported by the UCLA IDx program.

Data availability

Mass spectrometry data and proteinGroups.txt output table was deposited in the MassIVE database under the accession MSV000088000 at ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000088000/. Oncoscan Copy Number Aberration (CNA) data and RNA-seq data can be found at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under accession EGAS00001003179.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada, and University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

This manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors to publish and is not submitted or under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Competing interests

The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Robert E. Reiter, Email: rreiter@mednet.ucla.edu

Paul C. Boutros, Email: PBoutros@mednet.ucla.edu

Thomas Kislinger, Email: thomas.kislinger@mail.utoronto.ca.

References

- 1.Klotz L, Chin J, Black PC, Finelli A, Anidjar M, Bladou F, et al. Comparison of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-targeted biopsy with systematic transrectal ultrasonography biopsy for biopsy-naive men at risk for prostate cancer: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(4):534–542. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, Gabe R, Kaplan R, Parmar MK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houlahan KE, Salmasi A, Sadun TY, Pooli A, Felker ER, Livingstone J, et al. Molecular hallmarks of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging visibility in prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;76(1):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pachynski RK, Kim EH, Miheecheva N, Kotlov N, Ramachandran A, Postovalova E, et al. Single-cell spatial proteomic revelations on the multiparametric MRI heterogeneity of clinically significant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(12):3478–3490. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purysko AS, Magi-Galluzzi C, Mian OY, Sittenfeld S, Davicioni E, du Plessis M, et al. Correlation between MRI phenotypes and a genomic classifier of prostate cancer: preliminary findings. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(9):4861–4870. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li P, You S, Nguyen C, Wang Y, Kim J, Sirohi D, et al. Genes involved in prostate cancer progression determine MRI visibility. Theranostics. 2018;8(7):1752–1765. doi: 10.7150/thno.23180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chua MLK, Lo W, Pintilie M, Murgic J, Lalonde E, Bhandari V, et al. A prostate cancer “Nimbosus”: genomic instability and SChLAP1 dysregulation underpin aggression of intraductal and cribriform subpathologies. Eur Urol. 2017;72(5):665–674. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhandari V, Hoey C, Liu LY, Lalonde E, Ray J, Livingstone J, et al. Molecular landmarks of tumor hypoxia across cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):308–318. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner EW, Yip SM, Chi KN, Wyatt AW. DNA repair defects in prostate cancer: impact for screening, prognostication and treatment. BJU Int. 2019;123(5):769–776. doi: 10.1111/bju.14576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salami SS, Kaplan JB, Nallandhighal S, Takhar M, Tosoian JJ, Lee M, et al. Biologic significance of magnetic resonance imaging invisibility in localized prostate cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3:1–12. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha A, Huang V, Livingstone J, Wang J, Fox NS, Kurganovs N, et al. The proteogenomic landscape of curable prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(3):414–427.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen S, Huang V, Xu X, Bristow RG, Boutros PC. Widespread and functional RNA circularization in localized prostate cancer. Cell. 2019;176(4):831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Methods. Method details.

Additional file 2. Fig. S1. Tumor/NAT differences. A Consensus clustering of samples (n = 81, K = 4) using the top 25% most variable proteins (n = 1,193, K = 4). B Differentially abundant protein-coding RNAs in tumors and NATs from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Statistically significant genes (FDR < 0.05) are colored in black. C Associations of protein abundance changes between tumor versus NAT, and mpMRI-visible NAT versus mpMRI-invisible NAT. Only proteins that were significantly differentially expressed in tumor and NAT regions (FDR < 0.05) were used for this analysis. D Associations of protein-coding RNA abundance changes between tumor versus NAT, and mpMRI-visible tumor versus mpMRI-invisible tumor. Only protein-coding RNAs that were significantly differentially expressed in tumor and NAT regions (FDR < 0.05) were used for this analysis. Proteins or transcripts that were significant (FDR < 0.05) in the tumor-NAT comparison and had the same directionality are marked in black. NAT: histologically normal prostate adjacent to the tumor; mpMRI: multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging; FDR: Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted p-value.

Additional file 3. Table S1. Summary and characteristics of patient cohort.

Additional file 4. Table S2. Proteins quantified by mass spectrometry.

Additional file 5. Table S3. Pathway analysis of protein clusters.

Data Availability Statement

Mass spectrometry data and proteinGroups.txt output table was deposited in the MassIVE database under the accession MSV000088000 at ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000088000/. Oncoscan Copy Number Aberration (CNA) data and RNA-seq data can be found at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) under accession EGAS00001003179.