Abstract

Nearly half of all adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) live in India and China. These populations have an underlying predisposition to deficient insulin secretion, which has a key role in the pathogenesis of T2DM. Indian and Chinese people might be more susceptible to hepatic or skeletal muscle insulin resistance, respectively, than other populations, resulting in specific forms of insulin deficiency. Cluster-based phenotypic analyses demonstrate a higher frequency of severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus and younger ages at diagnosis, lower β-cell function, lower insulin resistance and lower BMI among Indian and Chinese people compared with European people. Individuals diagnosed earliest in life have the most aggressive course of disease and the highest risk of complications. These characteristics might contribute to distinctive responses to glucose-lowering medications. Incretin-based agents are particularly effective for lowering glucose levels in these populations; they enhance incretin-augmented insulin secretion and suppress glucagon secretion. Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors might also lower blood levels of glucose especially effectively among Asian people, while α-glucosidase inhibitors are better tolerated in east Asian populations versus other populations. Further research is needed to better characterize and address the pathophysiology and phenotypes of T2DM in Indian and Chinese populations, and to further develop individualized treatment strategies.

Subject terms: Type 2 diabetes, Diabetes

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is increasing substantially in India and China. This Review discusses the epidemiology, phenotypes and pathogenesis of T2DM in India and China and evaluates options for optimal pharmacological management.

Key points

India and China account for nearly half of the global number of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and incidence rates are rising rapidly among young people.

Indian and Chinese people seem to have increased susceptibility to reduced insulin secretion, which probably has a stronger or more frequent role than insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of T2DM than in other populations.

In many Indian people, deficient first-phase insulin secretion and increased hepatic insulin resistance result in impaired fasting glucose, while in many Chinese people, deficient first-phase and second-phase insulin secretion and increased skeletal muscle insulin resistance result in impaired glucose tolerance.

Cluster-based phenotypic analyses demonstrate a higher frequency of severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus and demonstrate generally younger ages at diagnosis, lower β-cell function, lower insulin resistance and lower BMI among Indian people and Chinese people compared with European people.

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists improve pancreatic β-cell function and reduce blood levels of glucose especially effectively in Indian and Chinese people compared with other populations.

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors might lower blood levels of glucose more effectively in Asian people than in European people, while α-glucosidase inhibitors are better tolerated among east Asian people than in other populations.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a complex, heritable and heterogeneous condition that manifests in a range of phenotypes1. Characterizing these phenotypes could reveal insights into the underlying pathophysiology, which is relevant in individualizing clinical management to each patient2,3. There is keen interest in personalizing the treatment of T2DM using a ‘precision medicine’ approach that integrates epidemiological, phenotypic, genetic and molecular data4,5. However, much of the evidence in this arena has been limited to studies in populations of European descent.

Of the estimated 463 million adults with diabetes mellitus globally, >90% have T2DM and nearly half live in two large countries: India and the People’s Republic of China (henceforth referred to as China)6. Indian and Chinese people exhibit differences in the characteristics of T2DM compared with people of European descent, including a younger age at diagnosis, greater tendency towards β-cell failure and leaner body habitus7–9. In these populations, novel analytical approaches have revealed phenotypic variations in young-onset T2DM (defined in this Review as age at diagnosis <40 years10) and other subtypes of T2DM, and have revealed unique responses to certain glucose-lowering medications (for example, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and α-glucosidase inhibitors). Examining how the pathophysiology and phenotypes of T2DM vary among Indian and Chinese people could generate valuable insights to inform the development, refinement and broader implementation of precision medicine strategies.

In this Review, we synthesize the latest evidence regarding the epidemiology, pathophysiology, phenotypes and glycaemic management of T2DM among Indian and Chinese populations and their diasporas, and identify novel avenues of research to advance therapeutic approaches. Because the vast majority (98.0–99.7%11,12) of Chinese and Indian adults with diabetes mellitus have T2DM, we included population-based studies of diabetes mellitus in general, as these are likely to be representative of T2DM. We also include studies that report pertinent findings for Asian people in general (including people from India, China and other Asian regions) if country-specific or ethnicity-specific data were unavailable. Atypical forms of diabetes mellitus (including fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes mellitus13,14) are beyond the scope of this Review.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

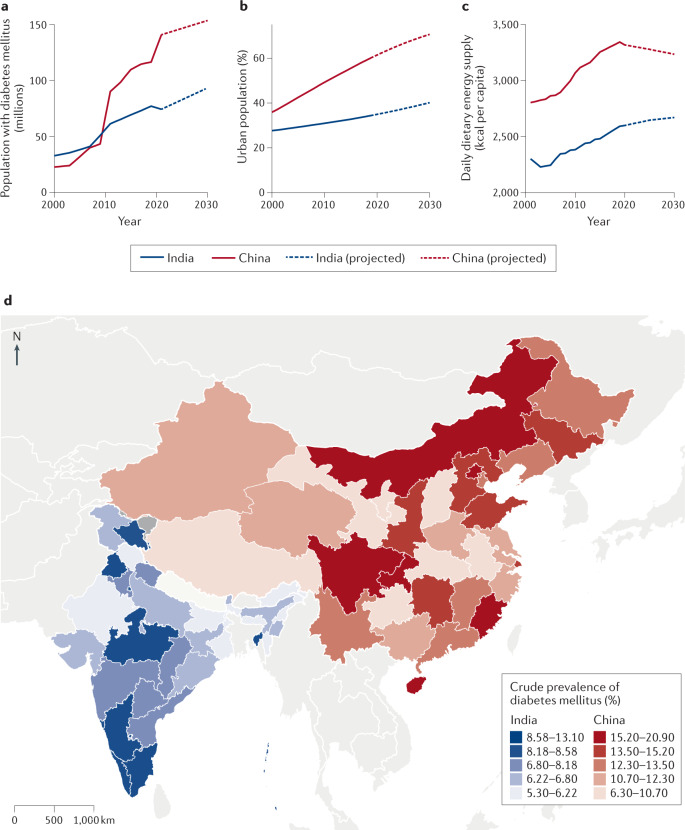

In 2021, the estimated age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 10.6% (95% CI 9.2–12.0%) in China and 9.6% (95% CI 8.5–10.6%) in India, accounting for 145 million and 74 million people, respectively, or 41% of the global number of adults with diabetes mellitus6 (Fig. 1). The large burden of diabetes mellitus in India and China has been shaped by various behavioural, geographical, socioeconomic and cultural factors in each country (Box 1).

Fig. 1. Burden of diabetes mellitus and its correlates in India and China.

a | Estimated number of adults with diabetes mellitus (millions) aged 20–79 years in India and China from 2000 with projections to 2030. b | Percentage of population residing in urban areas in India and China from 2000 with projections to 2030. c | Average daily dietary energy supply in India and China from 2000 with projections to 2030. Dietary energy supply indicates the amount of calories available for consumption in a given country; measures of individual caloric intake are not available at the national population level253,254. d | Crude prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the states of India (2016) and provinces of China (2015–2017). Crude prevalence rates are shown to illustrate spatial distribution. Rates are not directly comparable between countries owing to differences in the age distribution between countries (comparable age-standardized data unavailable). In China and India, the rising prevalence of diabetes mellitus is driven by rapid urbanization, increased caloric intake and reduced physical activity255–258. The high crude prevalence and number of people with diabetes mellitus in China relative to India is driven in part by China’s older age distribution259,260. Panel a is derived from data from the International Diabetes Federation Atlas6. Panel b is derived from data from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, & Population Division261. Panel c is derived from data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations253,254. Panel d is derived from data from Tandon et al.262 and Li et al.53.

Box 1 Comparing contextual factors affecting T2DM in India and China.

Health-related behaviours

Rapid economic growth, unprecedented urbanization, sedentary behaviour, insufficient sleep, increased carbohydrate and saturated fat consumption and reduced fibre consumption drive an increase in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) prevalence255–258.

Packaged foods and beverages in India and China have the highest energy density and saturated fat content in a comparison with 12 other countries92.

High rates of tobacco use among men (China: 50.5%; India: 19.0%)266,267 are associated with increased risk of T2DM268 and its complications268,269.

Geographical and socioeconomic factors

Owing to the high population and large size of China and India, both countries have wide variations in prevalence: the highest rates are in southern India (Tamil Nadu, Kerala: 12.1–12.3%)262 and northern China (Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia: 12.7%)270.

Diabetes mellitus is most prevalent among wealthy271,272 and urban populations (India: urban 11.2%, rural 5.2%48; China: urban 13.1%; rural 8.7%270).

Public health-care systems are limited by inadequate public investment, especially in India relative to China (1% versus 5% of gross domestic product, respectively)273.

Limited health services and high risk of unaffordable health-care costs contribute to disparities in outcome among rural and low socioeconomic status populations compared with wealthier, urban populations274–277.

Culture, tradition and religion

Linguistic, ethnic and sociocultural variation across India and China (especially ethnic minorities that are not Han Chinese) shape lived experiences278,279 and should inform T2DM interventions276,277.

Religious fasting (such as Ramadan and Navaratri) affects diet and physical activity; optimal T2DM management requires education and individualization280,281.

Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine) and traditional Chinese medicine are often used as holistic, patient-focused approaches to address T2DM.

Traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda include components such as litchi (also called lychee)282 and pomegranate283 to address T2DM284. Litchi toxicity causes hypoglycaemia in children285, and some components can alter the gut microbiome286.

Incidence

In India, the incidence of total diabetes mellitus has been estimated within local and regional studies. In Tamil Nadu, the Chennai Urban Population Study reported an incidence of 20.2 per 1,000 person-years for the period 1996–1997 (n = 513)15. The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (2001–2013) estimated an incidence of 33.1 per 1,000 person-years (n = 1,376)16. Among adults aged 20–44 years in Delhi and Chennai, the Centre for Cardiometabolic Risk Reduction in South Asia Study (CARRS) (2010–2018) reported incidence rates of 14.2 (men) and 14.8 (women) per 1,000 person-years (n = 6,676)17,18. In Puducherry, the incidence was 21.5 per 1,000 person-years in 2007 (n = 1,223)19, while in urban Kerala, the incidence was 24.5 per 1,000 person-years between 2007 and 2017 (n = 869)20.

In China, T2DM incidence trends have been estimated in local and regional studies using population-based data. In Zhejiang province, the incidence of T2DM increased from 193.8 to 443.7 (men) and 212.9 to 370.5 (women) per 100,000 person-years over the period 2007–2017 (ref.21). In Hong Kong, the incidence of young-onset T2DM increased from 75.4 to 110.8 (men) and 45.0 to 62.1 (women) per 100,000 population over the period 2002–2015 (ref.11). Among those aged 40–59 years in Hong Kong, incidence increased from 697.0 to 852.7 (men) and 569.7 to 639.8 (women) per 100,000 person-years between 2005 and 2012 and 2005 and 2011, respectively, while incidence declined among those aged ≥60 years.

International comparisons of T2DM incidence are limited by differences in age standardization, time period during which incidence rates were measured, living environments and methodologies. In a comparative study using similar paediatric registries (age <20 years), the incidence of young-onset T2DM was lower in Chennai and New Delhi (0.5 per 100,000 population) than in the US SEARCH for Diabetes study (5.9 per 100,000 population). However, this difference could have been due to greater diagnostic delay in India than in the USA22. Multi-ethnic studies in high-income countries suggest that T2DM incidence is higher among populations of Indian origin than in populations of Chinese origin in the global diaspora. A Canadian population-based study reported nearly double the incidence of T2DM among individuals of south Asian origin (defined here as ethnic origin from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh or Sri Lanka) compared with individuals of Chinese origin23. Young-onset T2DM incidence among individuals of south Asian origin was triple that of individuals of Chinese origin aged 20–29 years (147.2 versus 46.9 per 100,000 patient-years), and more than double that of individuals of European origin aged 20–29 years (147.2 versus 67.1 per 100,000 patient-years)24. In a population-based international comparative study, T2DM incidence was highly heterogeneous among Chinese Canadians. People who had emigrated from the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan had respectively higher, similar and lower T2DM incidence rates compared with their origin populations25.

Pathophysiology

Insulin resistance and impairments in insulin secretion are crucial factors in the pathophysiology of T2DM26,27 (Box 2). Insulin is secreted by pancreatic β-cells in response to rising arterial concentrations of glucose28. First-phase insulin release peaks at 2–4 min after the initial rise in arterial levels of glucose and drops sharply by 10–15 min, while second-phase insulin release is more gradual, achieving a steady state at 2–3 h after the initial rise in arterial levels of glucose28. Under conditions of insulin resistance, β-cells are stimulated to secrete more insulin than under conditions of normal insulin sensitivity28. Insufficient insulin secretion, especially in the presence of insulin resistance, glucolipotoxicity and obesity-related inflammation, results in hyperglycaemia and, eventually, T2DM29.

Box 2 Indices of β-cell function.

The gold standard for quantifying insulin secretion and insulin resistance are the hyperglycaemic and euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamps, respectively287. During these tests, the concentration of glucose in the blood is ‘clamped’ at a constant concentration to reduce the confounding effects of prevailing blood levels of glucose on insulin action or secretion287. However, clamps are intensive and impractical to implement in large studies. Simpler surrogate measures have been developed using fasting blood tests that assess fasting levels of insulin and glucose in a steady state. The Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA) method is a mathematical model that indirectly estimates β-cell function (HOMA-β) or hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) on the basis of fasting plasma levels of glucose and insulin or C-peptide concentrations288. There are various versions of the HOMA model288. The HOMA method can also quantify insulin sensitivity (HOMA-S), which is the reciprocal of HOMA-IR288. HOMA-β is modestly correlated with the gold standard (r = 0.69), whereas HOMA-IR is more strongly correlated with the gold standard (r = 0.88)288,289. It is important to note that HOMA and clamps reflect steady and dynamic states, respectively, and could therefore be viewed as complementary measures288. Other methods of measuring in vivo insulin secretion have been derived using stimulated measurements with intravenous glucose, oral glucose and mixed-meal tolerance tests. These methods are reviewed elsewhere289,290. In particular, the oral disposition index is a measure of insulin secretion corrected for insulin sensitivity, and this test generally yields similar results to the clamp studies289.

In large epidemiological studies, the decline in β-cell function over time might be indirectly quantified as glycaemic deterioration121,122,291,292. The rate of glycaemic deterioration is equivalent to the slope of HbA1c over time, after accounting for glucose-lowering drugs using statistical adjustment121. As with HOMA methods288, glycaemic deterioration cannot be estimated among people treated with exogenous insulin121.

β-Cell dysfunction and insulin resistance

Although the natural history of T2DM has been traditionally described as a process of increasing age-related insulin resistance followed by declining β-cell function and insufficient insulin secretion, it has been postulated that people predisposed to T2DM probably have a primary genetic factor that impairs β-cell function26,28,30. This hypothesis is based partly on studies that demonstrate reduced first-phase and second-phase insulin secretion among healthy, normoglycaemic and insulin-sensitive first-degree relatives of people with T2DM28. Accordingly, T2DM might develop among genetically predisposed people when obesity or other factors such as age increase insulin resistance to overwhelm their intrinsically limited β-cell insulin secretion.

Several studies in south Asian populations suggested that people of Indian origin develop early β-cell failure in response to increased insulin resistance. This concept was demonstrated in the prospective British Whitehall study of 5,749 white civil servants and 230 civil servants of south Asian origin without diabetes mellitus at baseline (1991–2009)31. In this cohort, the Homeostatic Model Assessment of insulin sensitivity (HOMA-S) was lower among people of south Asian origin than in white people, but declined with age in both groups. However, the increase in the Homeostatic Model Assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-β), which might reflect a compensatory response to insulin resistance, was much greater and peaked around 15 years earlier (at age 50–60 years) in people of south Asian origin than in white people. During the study, fasting blood levels of glucose remained constant among white people but increased linearly with time among people of south Asian origin, indicating that compensatory insulin secretion was insufficient to overcome insulin resistance. These differences were partially explained by higher rates of obesity, less healthy dietary patterns and lower socioeconomic status in the south Asian versus the white population. Similar findings were reported in the Netherlands32 and in the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) and the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohorts of US adults with or without diabetes mellitus33.

By contrast, many people of Chinese origin seem to exhibit progressive β-cell failure despite declining insulin resistance over time. In the MASALA and MESA cohorts, HOMA-β dropped sharply during adulthood up to age 60 years, followed by a steadier decline after this age, in the presence of steadily declining Homeostatic Model Assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) across all ages33. In a systematic review, east Asian people (defined here as having an ethnic origin from China, Japan, South Korea or Taiwan) had high sensitivity to insulin but a severely limited innate capacity to secrete insulin34. This limited capacity meant that even a small reduction in insulin secretion (for example, due to ageing or β-cell exhaustion) would result in T2DM.

Multi-ethnic comparisons

In the MASALA and MESA cohorts33, HOMA-β was statistically significantly lower in south Asian people than in Chinese people33. Insulin secretion among south Asian and Chinese people was the lowest among all ethnic groups. South Asian people had a higher HOMA-IR than white or Chinese people, especially at the ages of 40–60 years33. After age 60 years, white people had the highest insulin resistance among these ethnic groups. In the CARRS cohort of adults in India and Pakistan without diabetes mellitus at baseline, HOMA-β was statistically significantly lower in these south Asian people compared with Pima Indian people35 and Black, but not white, people in the USA36 after adjusting for age and BMI. In the Singapore Adults Metabolism Study, β-cell function among people of Indian origin was not statistically significantly different from that of people of Chinese origin among lean (BMI <23 kg/m2) individuals without diabetes mellitus. People of Indian origin also had higher insulin resistance (measured using the euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp) than people of Chinese origin37.

Relative contributions of β-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance

Studies published during the past year suggest that decreased insulin secretion among Indian people could be more important than insulin resistance in predicting progression to T2DM. In the CARRS cohort, fewer Indian and Pakistani participants had obesity, and Indian and Pakistani participants had a lower HOMA-IR compared with age-matched Pima Indian people35, white people36 and Black people in the USA36. HOMA-IR also had a weaker association with incident diabetes mellitus among the south Asian CARRS cohort (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 2.28–3.58)35 compared with Pima Indian people (HR 4.40, 95% CI 3.49–5.56)35. This association between HOMA-IR and incident diabetes mellitus was also weaker in the CARRS cohort of south Asian people (HR 2.67, 95% CI 2.05–3.48)36 compared with Black people (HR 14.55, 95% CI 11.11–19.07)36 or white people (HR 34.64, 95% CI 27.63–43.42)36. Interestingly, higher HOMA-β was associated with lower diabetes mellitus incidence among all of these populations. This association was weaker among south Asian people (HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.34–0.58) compared with Black people (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.06–0.11) and white people (HR 0.05, 95% CI 0.04–0.06)36, but was similar among south Asian people (HR 0.35, 95% CI 0.28–0.44) and Pima Indian people (HR 0.34, 95% CI 0.26–0.43)35. In the MASALA study, insulin secretion, measured using the oral disposition index (Box 2), was associated with progression to pre-diabetes or T2DM after a mean of 2.5 years, while the insulin sensitivity index did not significantly predict incident pre-diabetes or T2DM after accounting for the level of visceral adipose tissue38. In Chennai, the Diabetes Community Lifestyle Improvement programme reported that the contribution of impaired β-cell function to impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) was greater than that of insulin resistance, suggesting that β-cell dysfunction was the main contributor to IFG and IGT39.

Studies in Chinese populations report mixed findings on the relative contributions of impaired insulin secretion and insulin resistance to T2DM pathogenesis. In Shanghai, cross-sectional studies reported worse β-cell function in people with T2DM compared with individuals with pre-diabetes, whereas insulin sensitivity was similar across groups40,41. Studies in Nanjing city42 and Zhejiang province43 found that both β-cell function and insulin resistance were worse among people with T2DM compared with people with pre-diabetes or normal glucose tolerance. Furthermore, in Zhejiang, insulin resistance was associated with increased odds ratio of pre-diabetes, whereas impaired β-cell function was associated with increased odds ratio of T2DM43. The nationwide China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort Study of 94,952 people found that a greater proportion of incident diabetes mellitus cases were attributable to HOMA-IR (24.4%, 95% CI 23.6–25.2%) than to HOMA-β (12.4%, 95% CI 11.2–13.7%)44 and that small increases in body weight were associated with increased risks of diabetes mellitus44. Although these studies seem to be conflicting, their interpretation is limited by potential confounders, including socioeconomic and health-related behavioural changes over time and the lack of dynamic insulin secretion indices.

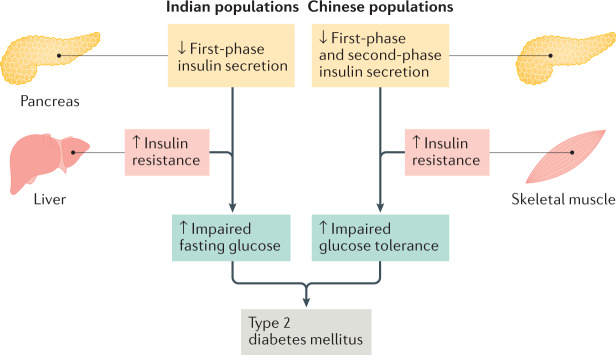

Distinct pathways of T2DM development

An indirect approach to characterizing the development of T2DM involves examining epidemiological patterns of IFG and IGT, which are different states of pre-diabetes associated with distinct metabolic abnormalities and a high risk of progression to T2DM45–47 (Fig. 2). In India, there is a preponderance of isolated IFG relative to isolated IGT (prevalence rate of 6.5%, 95% CI 6.3–6.7% and 2.8%, 95% CI 2.7–3.0%, respectively, in most states)48. This pattern is similar to white, Black and Hispanic populations in the USA, in which IFG is more common than IGT49. IFG is characterized by hepatic insulin resistance causing increased hepatic gluconeogenesis and reduced first-phase insulin secretion38,46,50. These changes are consistent with the observation of elevated HOMA-IR, a key indicator of hepatic insulin resistance, among people with IFG versus those with normoglycaemia46. Increased hepatic lipid accumulation might have an especially important role in Indian people51. In a multi-ethnic study of lean, healthy men in the USA, increased insulin resistance among people of Indian origin (relative to people who are not Asian and people of east Asian origin) was associated with increased hepatic triglyceride content, suggesting a predisposition to hepatic steatosis and hepatic insulin resistance52.

Fig. 2. Distinctive pathways of T2DM development commonly observed among Indian and Chinese populations.

This conceptualization is based on the epidemiological patterns of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) versus impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) prevalence observed in India and China, the known pancreatic β-cell defects associated with IFG and IGT and evidence from single-ethnic and multi-ethnic studies. In Indian populations, β-cell dysfunction often causes reduced first-phase insulin secretion. In the presence of increased insulin resistance, especially hepatic insulin resistance, Indian people have an increased risk of developing IFG, which might ultimately lead to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). In Chinese populations, β-cell dysfunction might predispose to globally impaired insulin secretion (reduced first-phase and second-phase insulin secretion). In the presence of insulin resistance, especially skeletal muscle insulin resistance, Chinese people have an increased risk of developing IGT, which might lead to T2DM. Hepatic insulin resistance and adiposity can be more severe in Indian people than in Chinese people, thus exacerbating insulin deficiency and causing relatively early (before age 40 years) and increased incidence of T2DM. Given the heterogeneous nature of T2DM pathogenesis, these features sometimes intersect within or vary between Indian and Chinese individuals.

By contrast, China has a much higher prevalence of isolated IGT (11.5%, 95% CI 10.5–12.7) than isolated IFG (2.4%, 95% CI 2.0–2.9)53. IGT is characterized by skeletal muscle insulin resistance and changes in both first-phase and second-phase insulin secretion46,50,54, a finding that has been specifically confirmed in Chinese people55. Hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp studies have demonstrated that insulin-stimulated glucose disposal, a key indicator of muscle insulin sensitivity, is reduced in IGT across ethnicities46. Furthermore, IGT could be associated with an increased risk of cardiometabolic disease compared with IFG among Chinese people56,57 and other populations54. IFG and IGT might arise from distinct β-cell abnormalities50 and confer different risks of progression to T2DM54. These issues require further characterization in Chinese and Indian populations.

Pathophysiological mechanisms

Genetic architecture

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have revealed insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms of T2DM, which is a complex polygenic disease. Most of the >500 currently identified genetic loci for T2DM58–60 are related to β-cell function or mass61. Most common genetic variants are similar across populations of south Asian, east Asian and European ancestry, suggesting that genetic susceptibility to T2DM is mostly shared across ethnicities62–65. However, some alleles vary in frequency across populations, and ancestry-specific genetic variants might partly explain some features of T2DM among Indian and Chinese populations. A south Asian GWAS that involved 5,700 Indian participants identified six novel genetic loci, including HNF4A (linked to defective insulin secretion in maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 1), GRB14 (which encodes a protein that binds to the insulin receptor and inhibits signalling) and ST6GAL1 (which encodes a protein that might influence insulin action)64. Other novel loci include SGCG (which encodes a protein expressed in skeletal muscle) among Indian Punjabi Sikh people66 and TMEM163 (which encodes a synaptic vesicle membrane protein linked to insulin secretion) among Indian people65. In the UK Biobank, people of south Asian origin had a lower frequency of genetic variants predisposing to subcutaneous adiposity compared with the white population, which might predispose them to increased visceral adiposity and adipocyte hypertrophy, resulting in β-cell glucolipotoxicity67. Because the population of India is particularly genetically complex owing to endogamy and diverse sociolinguistic groupings68, large sample sizes are required to ensure adequately powered GWAS and to stratify by Indian subpopulation69.

The unique genetic variants for T2DM in Indian populations seem to be distinct from those in Chinese populations. Large GWAS have confirmed that genetic loci such as PAX4 (which encodes a pancreatic islet transcription factor), PSMD6 and ZFAND3 (which encode proteins involved in insulin secretion), NID2 (associated with lipodystrophy traits or body adipose tissue distribution after adjustment for BMI) and ALDH2 (which encodes an enzyme for alcohol metabolism associated with T2DM in men) are unusually frequent among east Asian people60,63,70, who might have limited β-cell regenerative capacity71. In particular, polymorphisms of PSMD6 and PAX4 (which appears to be monomorphic in people who are not east Asian60) might reduce insulin secretion and β-cell functional mass, respectively72. These polymorphisms might also predict responses to rosiglitazone in Chinese populations (rosiglitazone is no longer used in most regions over concerns about increased cardiovascular risk73)74,75. Other studies suggest that genetic variants might predict responses to metformin and time to insulin therapy76, but further pharmacogenetic studies are required77.

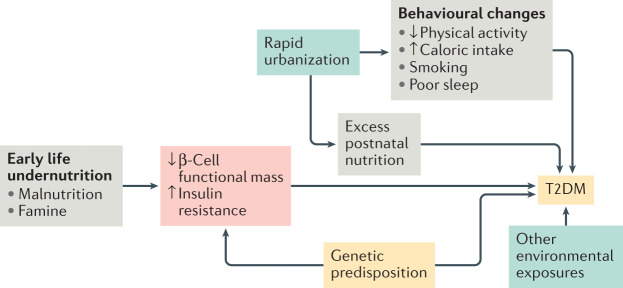

Early life environment

According to the developmental origins of health and disease ‘thrifty phenotype’ hypothesis, intrauterine and early life exposure to malnutrition followed by an energy-rich setting in later life results in a high risk of T2DM78 (Fig. 3). Major events such as the great Bengal famine (1943)79 and Chinese famine (1959–1961)80 affected millions of Indian and Chinese people, respectively. Fetal and childhood exposure to the Chinese famine, followed by high socioeconomic status during adulthood, were associated with increased T2DM incidence in several studies80,81. The effect of famine and malnutrition might be mediated by epigenetic changes82,83, decreased pancreatic β-cell proliferation and increased insulin resistance compared with individuals not exposed to famine or malnutrition84. In India, the prospective Pune Maternal Nutrition Study demonstrated that maternal undernutrition and vitamin B12 deficiency predicted low birthweight, childhood adiposity and childhood insulin resistance85. However, paternal T2DM is also associated with low birthweight86. This observation suggests that a genetic predisposition to insulin deficiency also partly explains the relationship between low birthweight and T2DM risk (the fetal insulin hypothesis)87. Conversely, maternal hyperglycaemia and obesity are associated with higher birthweight and increased risk of T2DM82 compared with mothers without hyperglycaemia or obesity during pregnancy. This association was demonstrated in the prospective Mysore Parthenon Birth Cohort Study, which reported increased childhood adiposity and insulin resistance among offspring of mothers with T2DM compared with those from mothers without T2DM88.

Fig. 3. Key factors influencing the development of T2DM.

According to the developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis, fetal or early life exposure to undernutrition results in low birthweight and adaptive responses characterized by reduced β-cell secretion and increased insulin resistance. Genetic predisposition to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) probably also contributes to these changes, as proposed by the fetal insulin hypothesis. In the context of the rapid pace of urbanization in India and China, the postnatal environment often provides excess nutrition, which further exacerbates the risk of T2DM. Health-related behaviours such as low levels of physical activity, high caloric intake, poor sleep and smoking independently raise the risk of T2DM255–258. Some genetic variants that predispose to T2DM seem to be unique among populations of east and south Asian ancestry. However, currently identified genetic variants explain <10% of the estimated 30–70% heritability of T2DM263–265. This figure is not exhaustive; concepts have been simplified here for the purposes of illustration.

Islet amyloid

Amyloid deposits within the pancreatic islets might have a role in T2DM pathogenesis by accelerating β-cell apoptosis26,89,90. An estimated 40–100% of individuals with T2DM have islet amyloid deposits90. A Chinese autopsy study demonstrated that individuals with T2DM were statistically significantly more likely to have islet amyloid deposits at autopsy than individuals without T2DM91. High dietary fat intake (which appears to be particularly common in India and China92) might increase islet secretion of amyloid89,90. Genetic studies investigating a link between T2DM risk and mutations of the islet amyloid polypeptide (also known as amylin) gene have shown that the S20G mutation is associated with T2DM and an earlier age at T2DM diagnosis (age <40 years) among Chinese93 and other east Asian populations90, but not in European-origin and Indian populations90,94. Animal studies suggest that this mutation might reduce the number and function of β-cells95.

Gut microbiome

Emerging evidence suggests that gut microbial composition might affect T2DM risk by modulating inflammation and affecting gut permeability, insulin resistance, carbohydrate processing and fatty acid oxidation96. Local differences in diet and environment probably contribute to unique gut microbial signatures among Indian97 and Chinese98 populations. These differences could affect T2DM risk and responses to glucose-lowering drugs97,98.

Infection

Infections increase insulin resistance by activating inflammatory mediators (for example, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and C-reactive protein) and could have a role in T2DM pathogenesis99,100. Hepatitis B infection is common in India and China, but, unlike hepatitis C infection, has not been consistently associated with T2DM in these populations101,102. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection increases insulin resistance among previously normoglycaemic individuals and might predispose to future T2DM development103. Limited evidence suggests that tuberculosis and its treatments might increase the risk of T2DM104,105. Helicobacter pylori infection has been inconsistently linked to T2DM in Chinese populations106,107.

Phenotypes

Subgroups of diabetes mellitus

In the Swedish All New Diabetics in Scania (ANDIS) cohort108, all incident cases of diabetes mellitus were classified into five subgroups using a cluster analysis based on specific phenotypic characteristics: age at diagnosis, BMI, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies, HOMA-β and HOMA-IR. The severe autoimmune diabetes mellitus subgroup consisted of people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and latent autoimmune diabetes mellitus of adulthood, and T2DM was divided into subgroups hypothesized to relate to disease aetiology: severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus, severe insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, mild obesity-related diabetes mellitus and mild age-related diabetes mellitus108.

Although this method of classification has been criticized as oversimplified109, comparing the clinical characteristics across subgroups and populations suggests distinct phenotypes of diabetes mellitus in Indian and Chinese people (Table 1). In India, a cluster-based analysis was performed among people with diabetes mellitus (disease duration <5 years) identified within private clinics across nine states110. Although GAD antibodies were unavailable to identify severe autoimmune diabetes mellitus, when compared with the ANDIS cohort, severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus occurred more often (26.2% versus 17.5%), at a younger age (mean 42.5 years versus 56.7 years), at a lower BMI (mean 24.9 kg/m2 versus 28.9 kg/m2) and with lower levels of β-cell function and insulin resistance within this Indian cohort. Individuals within the remaining subgroups were also younger at diagnosis, with lower BMI and lower β-cell function compared with the ANDIS cohort. In particular, the Indian subgroup with severe insulin resistance also had low β-cell function, a characteristic not observed in the Swedish subgroup with severe insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus (mean HOMA-β 64.5 versus 150.5). Indian people with obesity-related diabetes mellitus also had higher insulin resistance compared with Swedish people in this subgroup (mean HOMA-IR 4.1 versus 3.4). Although selection bias was a potential limitation, these findings appeared consistent when validated among a larger community-dwelling population sampled across 15 Indian states110.

Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics among subgroups of diabetes mellitus identified in Indian, Chinese and Swedish cohorts

| Parameter | Sweden | India | Chinaa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANDIS | INSPIRED110 | INDIAB110 | Li et al.111 | CNDMDS114 | Xiong et al.112 b | |

| Sample size (n) | 8,980 | 19,084 | 2,204 | 15,772 | 2,316 | 5,414 |

| Newly diagnosed | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Disease duration (years; mean (s.d.)) | 0 (0.0) | <5 | Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8.6 (6.3) |

| Setting | Clinic | Clinic | Survey | Clinic | Survey | Clinic |

| Location | Scania | Nine states | Fifteen states | National | National | Hunan |

| Severe autoimmune diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Frequency (%) | 6.4 | NA | NA | 6.2 | NA | 3.7 |

| Age at diagnosis (years; mean (s.d.)) | 50.5 (17.9) | NA | NA | 42.7 (14.0) | NA | 49.3 (12.1) |

| HbA1c (%; mean (s.d.)) | 9.5 (2.8) | NA | NA | 10.7 (5.3) | NA | 8.9 (2.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean (s.d.)) | 27.5 (6.4) | NA | NA | 22.0 (3.8) | NA | 24.3 (3.9) |

| HOMA-β (mean (s.d.)) | 56.7 (44.7) | NA | NA | 21.9 | NA | 84.0 (112.8) |

| HOMA-IR (mean (s.d.)) | 2.2 (1.6) | NA | NA | 0.7 | NA | 3.7 (7.9) |

| Severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Frequency (%) | 17.5 | 26.2 | 27.4 | 24.8 | 13.5 | 41.2 |

| Age at diagnosis (years; mean (s.d.)) | 56.7 (11.1) | 42.5 (10.8) | 40.1 (9.8) | 50.5 (11.6) | 52.4 (11.9) | 46.6 (10.7) |

| HbA1c (%; mean (s.d.)) | 11.5 (1.8) | 10.7 (2.1) | 10.0 (2.1) | 12.5 (4.0) | NA | 10.2 (1.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean (s.d.)) | 28.9 (4.8) | 24.9 (3.5) | 22.7 (3.1) | 22.5 (2.6) | 25.4 (3.2) | 25.0 (3.7) |

| HOMA-β (mean (s.d.)) | 47.6 (28.9) | 38.8 (26.9) | NA | 20.2 | NA | 32.2 (19.5) |

| HOMA-IR (mean (s.d.)) | 3.2 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.6) | NA | 1.1 | NA | 1.3 (0.8) |

| Severe insulin-resistant diabetes mellitusc | ||||||

| Frequency (%) | 15.3 | 12.1 | 7.6 | 16.6 | 8.6 | NA |

| Age at diagnosis (years; mean (s.d.)) | 65.3 (9.3) | 42.1 (9.8) | 45.4 (10.2) | 51.8 (11.0) | 47.4 (13.4) | NA |

| HbA1c (%; mean (s.d.)) | 7.1 (3.6) | 9.1 (1.9) | 9.0 (2.0) | 7.2 (3.6) | NA | NA |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean (s.d.)) | 33.9 (5.2) | 26.5 (3.1) | 25.0 (2.9) | 27.0 (3.2) | 27.8 (4.3) | NA |

| HOMA-β (mean (s.d.)) | 150.5 (47.2) | 64.5 (37.7) | NA | 98.6 | NA | NA |

| HOMA-IR (mean (s.d.)) | 5.5 (2.7) | 3.8 (1.9) | NA | 2.2 | NA | NA |

| Moderate obesity-related diabetes mellitusc | ||||||

| Frequency (%) | 21.6 | 25.9 | 30.3 | 21.6 | 32.7 | NA |

| Age at diagnosis (years; mean (s.d.)) | 49.0 (9.5) | 46.5 (10.4) | 48.2 (9.6) | 39.1 (10.2) | 52.1 (11.7) | NA |

| HbA1c (%; mean (s.d.)) | 7.4 (3.6) | 8.3 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.8) | 10.1 (4.1) | NA | NA |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean (s.d.)) | 35.7 (5.4) | 32.6 (4.1) | 29.9 (3.6) | 27.9 (3.0) | 29.3 (2.7) | NA |

| HOMA-β (mean (s.d.)) | 95.0 (32.5) | 100.8 (51.5) | NA | 36.0 | NA | NA |

| HOMA-IR (mean (s.d.)) | 3.4 (1.2) | 4.1 (1.5) | NA | 1.8 | NA | NA |

| Mild age-related diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| Frequency (%) | 39.1 | 35.8 | 34.8 | 30.9 | 45.1 | 55.1 |

| Age at diagnosis (years; mean (s.d.)) | 67.4 (8.6) | 50.2 (10.3) | 55.5 (9.8) | 54.8 (9.8) | 53.2 (12.7) | 53.6 (10.0) |

| HbA1c (%; mean (s.d.)) | 6.7 (3.1) | 7.2 (1.2) | 6.7 (1.2) | 7.6 (3.5) | NA | 7.1 (1.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean (s.d.)) | 27.9 (3.4) | 25.9 (2.9) | 23.4 (2.8) | 23.4 (2.6) | 23.3 (2.3) | 24.7 (3.5) |

| HOMA-β (mean (s.d.)) | 86.6 (26.4) | 94.1 (43.1) | NA | 48.8 | NA | 82.6 (42.6) |

| HOMA-IR (mean (s.d.)) | 2.6 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) | NA | 1.3 | NA | 1.5 (0.8) |

Cohorts included people with newly diagnosed or established diabetes mellitus as indicated. Among cohorts with established diabetes mellitus, age at diagnosis was ascertained retrospectively, and biomarkers were measured at variable times after diagnosis (indicated by disease duration). Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA) values included in this table were all calculated using C-peptide values. ANDIS, All New Diabetics in Scania; HOMA-β, Homeostatic Model Assessment of β-cell function; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment of insulin resistance; INDIAB, Indian Council of Medical Research-India Diabetes study; INSPIRED, India–Scotland Partnership for Precision Medicine in Diabetes project; CNDMDS, China National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study; NA, not available; s.d., standard deviation. aThe study by Wang et al.113 was excluded from this table owing to data unavailability. bStandardized by sex. cThe subgroup originally characterized by Anjana et al.110 as ‘combined insulin resistant and deficient diabetes’ in both Indian cohorts is referred to in this table and the text as severe insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus for consistency and ease of comparison. Similarly, the subgroup originally characterized as ‘insulin-resistant obese diabetes’ is referred to as moderate obesity-related diabetes mellitus. The distinctive characteristics of these subgroups are reviewed in the text.

In China, cluster-based analyses similarly revealed low levels of HOMA-β, HOMA-IR and BMI across subgroups, with younger ages at diagnosis and an increased frequency of severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus in some111–113, but not all114, cohorts compared with the ANDIS cohort. In a 2020 study (the largest study conducted in clinics across China)111, all subgroups had lower levels of HOMA-β, HOMA-IR and BMI compared with the ANDIS cohort. Severe autoimmune diabetes mellitus occurred at a younger age (mean 42.7 years) than in Swedish people (mean 50.5 years). As with Indian people, severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus was more common (24.8% versus 17.5%) than in the ANDIS cohort and occurred >5 years earlier in life. Severe insulin-resistant and moderate obesity-related diabetes mellitus were diagnosed at least a decade earlier in life than in ANDIS. Finally, the mild age-related diabetes mellitus subgroup was less frequent and was diagnosed a decade earlier compared with ANDIS. In the China National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study (CNDMDS), people with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus were identified in a nationally representative survey, but autoantibodies were unavailable and surrogate measures were used for HbA1c and C-peptide114. The findings were broadly similar to those of the 2020 study111, except for lower proportions of severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus and severe insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, higher proportions of moderate obesity-related diabetes mellitus and mild age-related diabetes mellitus, and older age at diagnosis of moderate obesity-related diabetes mellitus114. A similar study among hospital inpatients in Beijing reported younger age at diagnosis for severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus, but disease durations were unreported113. In Hunan, a clinic-based study of people with long disease duration was unable to replicate the ANDIS subgroups112.

In comparison with the Chinese cohorts, it appears that Indian people have generally higher levels of insulin resistance across subgroups, along with higher levels of insulin secretion across most subgroups110–112,114. Severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus presented earlier in life (around age 40 years), at a similar BMI, but with higher HOMA-β and HOMA-IR in the Indian cohort than in the Chinese cohorts110–112,114. Severe insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus also presented earlier in life, but with much lower HOMA-β in the context of higher HOMA-IR in Indian people compared with Chinese people110–112,114. Moderate obesity-related diabetes mellitus occurred with a similar frequency but with higher BMI, HOMA-β and HOMA-IR values among Indian cohorts compared with Chinese cohorts110–112,114. Mild age-related diabetes mellitus featured much higher HOMA-β and HOMA-IR among Indian people, but was otherwise generally similar to that seen in Chinese people110–112,114.

These Indian and Chinese cohorts generally featured younger ages at diagnosis compared with the ANDIS cohort108,110–112,114. Although these findings seem to conflict with previous multi-ethnic studies in high-income countries that report a higher incidence of young-onset T2DM among people of Indian origin relative to people of European or Chinese origin23,24, immigrant populations are heterogeneous and vary from the populations from which they emigrated according to socioeconomic status and other factors25. Moreover, young-onset T2DM incidence in Canada among men who have emigrated from China has risen over the past decade to surpass that seen in people who are not Chinese Canadian as of 2017 (ref.25). Although selection bias could have inflated the proportion of younger individuals in the clinic-based or hospital-based Chinese studies, new cases of diabetes mellitus in the nationally representative CNDMDS cohort were similarly diagnosed at younger ages compared with the ANDIS cohort111,112. Further research is required to confirm whether these data reflect a skewed distribution towards earlier age at T2DM diagnosis in Chinese people.

One US multi-ethnic cluster-based study included people aged ≥45 years in the MASALA and MESA cohorts examined on average 5.7 years after diagnosis with diabetes mellitus (standard deviation (s.d.) 7.8 years), without data on GAD antibodies115. People taking insulin were excluded from the cluster analysis and manually classified on the basis of age at diagnosis. Although the results were not directly comparable to those of ANDIS, five unique subgroups were identified: older age at onset (43%), severe hyperglycaemia (26%), severe obesity (20%), younger age at onset (1%) and requiring insulin medication use (9%). People of Chinese origin were more likely to be classified in the older age at onset subgroup than people of other ethnicities, and less likely to be classified in the severe obesity subgroups, while people of south Asian origin were most likely to be classified in the severe hyperglycaemia subgroup. Although the authors suggested that different metabolic processes might be occurring among south Asian and Chinese populations, further multi-ethnic studies are required to explore this possibility.

Young-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus

Phenotypes of T2DM have also been classified by age at diagnosis10,116. Young-onset T2DM is especially important in Indian and Chinese populations because of their tendency to be diagnosed at an early age (<40 years)110–112,114, as well as the aggressive course and poor outcomes of this condition10.

Rapid β-cell dysfunction

In the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) study of 699 mostly Black, white and Hispanic youth with young-onset T2DM (mean age 13.8–14.1 years) randomized to receive metformin with or without rosiglitazone or basal insulin, the oral disposition index declined by 20–35% per year, which is a much faster decline in insulin secretion than that seen in older populations117. For example, the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS; mean age 52–53 years) reported that HOMA-β declined by approximately 7% per year in people with newly diagnosed T2DM118,119. In A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial (ADOPT), HOMA-β declined by approximately 7–11% per year in mostly white, Black and Hispanic adults with T2DM (mean age 56.3–57.9 years) randomized to receive rosiglitazone, metformin or glyburide monotherapy120. The percentage decline in HOMA-β was equivalent to a glycaemic deterioration rate of around 0.07–0.14% per year120, which is similar in magnitude to that of a Scottish observational cohort121.

In China, multiple lines of evidence have confirmed the accelerated rates of β-cell decline in young-onset T2DM. In a Hong Kong population-based study of adults aged 18–75 years, the steepest rates of glycaemic deterioration were among those with young-onset T2DM, especially those diagnosed at age 20 years122. Aggressive glycaemic deterioration in young-onset T2DM contributed to persistently increased HbA1c levels and more than triple the cumulative exposure to hyperglycaemia from diagnosis until age 75 years, compared with usual-onset T2DM (defined here as age at diagnosis ≥40 years)122. A national Chinese cross-sectional survey of people with newly diagnosed T2DM showed that HOMA-β was similar across ages at diagnosis, but the difference in HOMA-β between people with T2DM and age-matched control individuals was much greater among people with young-onset than in people with usual-onset T2DM123. Furthermore, people with young-onset T2DM had the most abnormal HOMA-IR and oral disposition index out of all the groups in the study123. Similarly, a study conducted in India of 82 people aged <25 years with either young-onset T2DM, pre-diabetes or normoglycaemia showed that T2DM was associated with a lower oral disposition index, but not insulin resistance, after adjustment for age and obesity124.

High risk of complications

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration estimated that people with usual-onset T2DM might die up to 6 years earlier than those without T2DM125, but an analysis of the Swedish National Diabetes Registry estimated that those diagnosed with young-onset T2DM at age 15 years might lose 12 years of life compared with people without T2DM126. This increased risk of mortality is driven by an elevated risk of T2DM complications compared with usual-onset T2DM127–130.

In China, a national cross-sectional study of 200,000 people with T2DM who were identified using the China National HbA1c Surveillance System reported that those with young-onset T2DM had an increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.81–2.02)131. In a subset of this population, the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease was also higher among people with young-onset T2DM (5.1%) than those with usual-onset T2DM (1.5%; OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.46–1.95)132. In Hong Kong, young-onset T2DM was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.17–1.88) and diabetic kidney disease (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.12–1.62) versus usual-onset T2DM133. Furthermore, young-onset T2DM was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization owing to mental illness, with 36.1% of all hospitalizations of people with young-onset T2DM before age 40 years attributable to psychiatric conditions, including psychotic disorders and mood disorders134. In these studies, the increased risk of complications associated with a younger age at diagnosis was not entirely explained by longer disease duration131–134. The prevalence of complications in China varies along a north to south gradient, with higher rates among northern Chinese populations than southern Chinese populations for both young-onset and usual-onset T2DM135.

In India, the epidemiology of complications in young-onset T2DM is described at the local and regional level. In a large diabetes mellitus centre in Chennai, 267 people with young-onset T2DM diagnosed before age 25 years had a similar odds ratio of having diabetic nephropathy (OR 1.07, 95% CI 0.66–1.73) and higher odds ratio of having diabetic retinopathy (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.38–2.95) compared with 267 people with usual-onset T2DM diagnosed after age 50 years, and metabolic risk factors were more poorly controlled in the young-onset T2DM group136. In the same centre, a study of people diagnosed with diabetes mellitus at age 10–25 years found that people with young-onset T2DM had double the odds ratio of having any microvascular or macrovascular complication (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.27–3.51) compared with people who had T1DM137. A subsequent study estimated that the incidence of diabetic nephropathy was 13.8 per 1,000 person-years in T2DM compared with 6.2 per 1,000 person-years in T1DM (attained age <20 years)138.

Few international studies have systematically compared complication rates specifically among people with young-onset T2DM in India and China. In a cross-sectional study of people with T2DM from outpatient clinics across Asia (n = 5,646 (China, public clinics), 15,341 (Hong Kong, public clinics), 9,107 (India, private clinics)), the Joint Asia Diabetes Evaluation programme found that Indian people with young-onset T2DM had a higher prevalence of ischaemic heart disease (India, 8.3%; China, 2.8%; Hong Kong, 5.8%) and diabetic kidney disease (India, 19.7%; China, 1.3%; Hong Kong, 5.7%) than Chinese people; however, differences in disease duration (median: 9.0 years (India), 4.0 years (China) and 14.0 years (Hong Kong)) might have had a role139. The prevalence of stroke was higher among Chinese people than in Indian people with young-onset T2DM (China, 1.5%; Hong Kong, 3.3%; India, 0.7%)139.

Emerging management strategies

Clinical recommendations for management of young-onset T2DM lack evidence because most intervention studies have been conducted in people with usual-onset T2DM140,141. In China, short-term intensive insulin therapy is a standard treatment option for newly diagnosed T2DM142. Younger age at diagnosis predicted a reduced rate of glycaemic relapse (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.58–0.95 for every 10 years) after 2 weeks of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion among 124 Chinese adults with newly diagnosed T2DM (mean age 47.33 ± 9.45 years)143. A retrospective analysis of a randomized controlled trial that compared subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy with or without metformin among people with newly diagnosed T2DM showed that people with young-onset T2DM treated with metformin required lower doses of insulin than people with usual-onset T2DM. This finding suggests that people with young-onset T2DM might be more sensitive to metformin than people with usual-onset T2DM144. By contrast, an observational study of adults in Hong Kong showed that metformin alone or in combination with other drugs was associated with a similar degree of glycaemic lowering among people with young-onset T2DM and usual-onset T2DM122. In the TODAY study, metformin monotherapy was associated with treatment failure in 51.7% of people with young-onset T2DM diagnosed at age 10–17 years, with lower treatment failure rates when metformin was combined with rosiglitazone (38.6%) or behavioural intervention (46.6%)145. In the Restoring Insulin Secretion study, treatment for 3 months with insulin glargine followed by 9 months with metformin improved β-cell function compared with metformin monotherapy among adults diagnosed with T2DM at ages 20–65 years, but not among those diagnosed at ages 10–19 years146.

Additionally, early combination therapy with multiple glucose-lowering agents147 is a promising strategy for young-onset T2DM. In a 5-year randomized clinical trial, early treatment with metformin and the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitor vildagliptin led to greater and more durable glycaemic lowering compared with a sequential strategy of metformin followed by augmentation with vildagliptin148,149. These effects were similar in Asian people and people who are not Asian148, and the benefit was even greater in young-onset T2DM than usual-onset T2DM (48% versus 24% reduction in risk of treatment failure)150.

Pharmacological glycaemic management

Reducing the incidence of microvascular and macrovascular complications requires optimal glycaemic control, a fundamental cornerstone of multifactorial T2DM management151. Multiple classes of non-insulin pharmacological agent are commonly used to treat hyperglycaemia. In accordance with their distinctive pathophysiology and phenotypes, Indian and Chinese people with T2DM respond differently to many of these medications compared with other populations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and consensus recommendations for the use of non-insulin glucose-lowering drugs in Indian and Chinese populations

| Drug class | Drug action | Glycaemic lowering | Other characteristics | Consensus guidelines and recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India217 | China142 | USA and Europe218 | ||||

| Metformin (biguanide) | Activates AMP-activated protein kinase, reduces hepatic glucose production, enhances insulin-mediated glucose uptake, increases glucose utilization and GLP1 secretion in the gut without weight gain or hypoglycaemia219–221 | Probably efficacious in Asian people153, but there have been no studies comparing the effects of metformin in Asian populations and populations that were not Asian | Improves β-cell function among Indian154 and Chinese155 people | First-line monotherapy (HbA1c <9%) or as component of dual oral therapy (asymptomatic HbA1c >9%)217 | Preferred first-line monotherapy222 | First-line monotherapy218 |

| α-Glucosidase inhibitors | Delay carbohydrate absorption in the small bowel, thus reducing postprandial glucose excursion and postprandial insulin secretion223 | Glycaemic-lowering efficacy is similar to that of metformin156 and DPP4 inhibitors157 | Fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects (specifically diarrhoea) in east Asian populations than people who are not Asian163 | Second-choice second-line therapy in combination with metformin for asymptomatic HbA1c >9%217 | Less preferred as first-line monotherapy than metformin142 | Not specifically recommended218 |

| Real-world glucose-lowering effectiveness might be better in Chinese (and other east and southeast Asian) people than Indian (and other south Asian) and European people161 | Better weight reduction than metformin or DPP4 inhibitor among Chinese people156,157 | Second-line or third-line therapy in combination with metformin142 | ||||

| Sulfonylureas | Reduce blood levels of glucose in a glucose-independent manner by binding to the SUR and closing the ATP-sensitive potassium channels, thus stimulating β-cell insulin secretion165 | Gliclazide reduces blood levels of glucose efficaciously in Asian populations and populations that were not Asian172 | Glyburide accelerates β-cell decline, especially in severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus (no studies in Asian people)116 | First-choice second-line therapy in combination with metformin for asymptomatic HbA1c >9%217 | Less preferred as first-line monotherapy than metformin142 | Second-line or third-line therapy in situations in which cost is a major issue218 |

| Probably no effect on the risk of cardiovascular disease224 | Greater glycaemic-lowering effectiveness than thiazolidinediones for men with BMI <30 kg/m2 among people of European origin (no studies in Asian people)174 | Probably do not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease across Asian populations and populations that are not Asian225 | Consider as an initial monotherapy (especially gliclazide167) if a patient has a contraindication or intolerance to metformin166 | Second-line or third-line therapy in combination with metformin142 | ||

| DPP4 inhibitors | Inhibit DPP4, an enzyme that catalyses the degradation of incretins such as GLP1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide175,176 | Sitagliptin has greater glucose-lowering efficacy in Asian populations than in populations that are not Asian; these182 benefits to Asian populations might apply to all DPP4 inhibitors185,186 | Less improvement in β-cell function among Asian populations compared with populations that were not Asian187 | First-choice second-line therapy in combination with metformin for asymptomatic HbA1c >9%217 | Second-line or third-line therapy in combination with metformin142 | Second-line or third-line therapy for individuals with a compelling need to minimize hypoglycaemia218 |

| No effect on cardiovascular events224,226 | Higher insulin resistance associated with less-effective glucose lowering among people of European origin (no studies in Asian people)183 | |||||

| Thiazolidinediones | Decrease insulin resistance by activating the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, stimulating differentiation of pre-adipocytes to adipocytes, shifting adipose tissue distribution from visceral to subcutaneous, ameliorating glucolipotoxicity and inflammation227 | Probably efficacious in Asian people189, but no studies comparing effects with people who were not Asian | Improved insulin sensitivity and pancreatic β-cell function among Indian190 and Chinese people191 | Second-choice second-line therapy in combination with metformin for asymptomatic HbA1c >9%217 | Second-line or third-line therapy in combination with metformin142 | Second-line or third-line therapy if cost is a major issue or if there is a compelling need to minimize hypoglycaemia218 |

| Might reduce the risk of cardiovascular complications in Chinese people197 | ||||||

| Increased risk of heart failure, fracture and bladder carcinoma (pioglitazone)194,228–230 | Less efficacious in preventing T2DM among south Asian people than in people who were not Asian192 | Does not increase the risk of hospitalization due to heart failure among east Asian people193 | ||||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Lower blood levels of glucose by inhibiting SGLT2-mediated glucose reabsorption in the kidney in an insulin-independent manner231,232 | Similar200,201 or more186 efficacious glucose lowering in Asian people compared with people who were not Asian | Similar200,201 or more186 efficacious weight lowering in Asian people versus people who were not Asian | First-choice second-line therapy in combination with metformin for asymptomatic HbA1c >9%217,233 | Second-line or third-line therapy in combination with metformin142 | Recommended independently of HbA1c for patients with established ASCVD (or indicators of high ASCVD risk), heart failure or chronic kidney disease218 |

| Reduce weight234–236, blood pressure231, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality234–237, non-fatal myocardial infarction234–237, heart failure hospitalization237–239, progression of diabetic kidney disease234–237,240; increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis241,242, genital mycotic infections237,242 and lower-extremity amputations241,242 | Similar cardiovascular risk reduction in Asian people compared with white people202 | Consider as first-line monotherapy if a patient has intolerance or a contraindication to metformin233 | Recommended in addition to metformin for patients with established ASCVD, high risk of ASCVD or chronic kidney disease | Second-line or third-line therapy for individuals with a compelling need to minimize hypoglycaemia218 | ||

| SGLT2 inhibitors are preferred over GLP1 receptor agonists for patients with heart failure243 | Second-line or third-line therapy for individuals with a compelling need to minimize weight gain or promote weight loss218 | |||||

| GLP1 receptor agonists | Activate the GLP1 receptor with multiple actions, including delayed absorption of nutrients in the stomach and small bowel, decreased appetite and food consumption, weight loss, glucose-dependent insulin secretion and suppression of glucagon, resulting in reduction in hyperglycaemia239,244. | Similarly efficacious glucose lowering in Asian people and people who are not Asian186 | Greater cardiovascular risk reduction in Asian people compared with white people202 | Second-choice second-line therapy in combination with metformin for asymptomatic HbA1c >9%217 | Second-line or third-line therapy in combination with metformin142 | Recommended independently of HbA1c for patients with established ASCVD (or indicators of high ASCVD risk)218 |

| Reduced cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and diabetic kidney disease progression237,245–251 | More effective glucose lowering among Chinese people with shorter disease duration and higher baseline HbA1c213 | Consider as monotherapy if a patient has metformin intolerance, obesity, established ASCVD or high risk of ASVCD215 | Recommended in addition to metformin for established ASCVD, high risk of ASCVD or chronic kidney disease with contraindication to SGLT2 inhibitors, regardless of baseline HbA1c243,252 | Second-line or third-line therapy for individuals with a compelling need to minimize hypoglycaemia218 | ||

| Associated with gastrointestinal adverse effects, such as nausea237. | Second-line or third-line therapy for individuals with a compelling need to minimize weight gain or promote weight loss218 | |||||

AMP, adenosine monophosphate; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; GLP1, glucagon-like peptide 1; SGLT2, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2; SUR, sulfonylurea receptor; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Metformin

The efficacy of metformin as a treatment for T2DM was first demonstrated in the UKPDS study152. Subsequent studies have verified that metformin lowers glucose levels efficaciously among Chinese and south Asian people153, and improves β-cell function among Indian people154 and Chinese155 people without obesity. However, no studies to our knowledge have directly compared its effects across Chinese, Indian and other populations.

α-Glucosidase inhibitors

In China, the Metformin and Acarbose in Chinese as the Initial Hypoglycaemic Treatment study reported that acarbose was not inferior to metformin in HbA1c lowering (mean difference 0.01%, 95% CI −0.12% to 0.14%), and resulted in better weight reduction and improved levels of lipids compared with metformin156. A meta-analysis comparing acarbose with DPP4 inhibitors also reported that acarbose had superior weight loss efficacy with a similar degree of glucose lowering157. In western populations with IGT, acarbose was found to reduce the risk of developing T2DM (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.63–0.90) compared with placebo158. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported that acarbose had a greater HbA1c-lowering effect among east Asian populations than in western populations (1.26% (s.d. 1.20%) versus 0.62% (s.d. 1.28%))159. This difference was postulated to be driven by the fairly large proportion of starch content in east Asian diets160. An observational study of 21 countries also found that east and southeast (defined here as having an ethnic origin from Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Cambodia or Singapore) Asian people had larger HbA1c reductions with acarbose compared with south Asian people and European people161. These findings conflict with other systematic reviews reporting similar HbA1c-lowering effects in east Asian people and western people162,163. The incidence of diarrhoea as an adverse effect might be less common in Asian people than people who are not Asian163. This finding may be most applicable to east Asian people because the Asian populations included within this meta-analysis were predominantly east Asian. In a trial among Chinese people with coronary artery disease and IGT, acarbose prevented the onset of diabetes mellitus but did not reduce the frequency of cardiovascular events164.

Sulfonylureas

Although sulfonylureas can cause hypoglycaemia and weight gain165, they are cheap and are the second most common oral glucose-lowering medication in India166–168 and China169,170 after metformin. Glycaemic improvements with sulfonylureas might be less durable compared with improvements with other classes of glucose-lowering medication owing to accelerated β-cell failure, especially with older sulfonylureas165. In ADOPT, the incidence of elevated fasting blood levels of glucose >10.0 mmol/l after a median of 4.0 years of treatment was 34% for glyburide compared with 21% and 15% for metformin and rosiglitazone, respectively120. A cluster-based analysis of the ADOPT cohort showed that glycaemic deterioration was the steepest among those with severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus treated with glyburide, while those with mild age-related diabetes mellitus showed the greatest benefit116. An intensive glucose-lowering strategy using modified-release gliclazide, a modern sulfonylurea, successfully lowered HbA1c to 6.5% after a median of 5 years in the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial171. A sub-analysis of the ADVANCE trial showed that HbA1c lowering was similar among Asian people (defined in this study as people from China, India, Malaysia and the Philippines) (−0.78%, 95% CI −0.83% to −0.74%) and eastern European people (−0.71%, 95% CI −0.78% to −0.64%)172. Secondary analyses of clinical trials suggest that sulfonylureas lower blood levels of glucose more effectively among men of European origin without obesity, and less effectively among women of European origin with obesity, compared with thiazolidinediones173,174. These findings have not been replicated in Indian and Chinese populations.

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors

DPP4 inhibitors lower blood levels of glucose by restoring first-phase insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner and suppressing abnormally elevated glucagon levels175,176, thus targeting two crucial issues in T2DM and IGT177. These features of DPP4 inhibitors are especially important in the context of β-cell dysfunction among Indian and Chinese people. Although the initial uptake of DPP4 inhibitors was slow in China170,178 and India168, their popularity seems to be rapidly increasing178–180, especially with the availability of low-cost tenegliptin in India181. In the Trial Evaluating Cardiovascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin study, east Asian people had the greatest initial reduction in HbA1c (−0.60%) compared with other groups (≤0.55% reduction)182. This greater effect in east Asian people has been attributed to the restoration of first-phase insulin secretion176. Lower levels of insulin resistance among east Asian people111,112,114 relative to people of European origin108 could also have a role, as insulin resistance is associated with less-effective glucose lowering with DPP4 inhibitors among people of European origin183. Further research is required to confirm whether these findings extend to Indian people184. A meta-analysis that compared randomized controlled trials including mostly Asian participants with trials that included mostly participants who were not Asian found that DPP4 inhibitors lowered HbA1c better in Asian people than in people who were not Asian (between-group HbA1c difference –0.26%, 95% CI –0.36% to –0.17%)185. Another meta-analysis that compared randomized controlled trials that included mostly white participants with trials that included mostly Asian participants reported similar HbA1c lowering in white people (−0.49%, 95% CI −0.59% to −0.38%) and Asian people (−0.62%, 95% CI −0.8% to −0.45%)186, but a sensitivity analysis restricted to studies 12–52 weeks in duration showed greater HbA1c lowering among Asian people (mostly east Asian people; −0.73%, 95% CI −0.88% to −0.57%) versus white people (−0.49%, 95% CI −0.59% to −0.39%)186. An additional meta-analysis reported better glucose lowering with DPP4 inhibitors in Asian people compared with white people (between-group HbA1c difference –0.18%, 95% CI –0.32% to –0.04%), but improvements in HOMA-β were smaller in Asian people than in white people187. Similar findings have been described with DPP4 inhibitor and metformin combination therapy188.

Thiazolidinediones

A meta-analysis reported that pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are efficacious in lowering HbA1c among Chinese, Indian and other Asian people189, but, to our knowledge, there are no studies comparing Chinese, Indian or Asian people in general with people who are not Asian. In a UK study of 177 people of Indian descent with T2DM, rosiglitazone reduced HbA1c by 1.16% compared with placebo and improved insulin sensitivity and β-cell function190. Similar findings have been described with pioglitazone in China191. In the multi-ethnic Diabetes Reduction Assessment with Ramipril and Rosiglitazone Medication trial, rosiglitazone was less efficacious in reducing the incidence of diabetes mellitus in south Asian people than in people of other ethnicities192. An international observational study reported that pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are associated with increased hospitalization for heart failure in Australia and Canada, but not in east Asian countries or regions193. In European populations, pioglitazone reduces all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction and stroke among people with T2DM194,195, especially those with insulin resistance196. In China, an observational study suggested that pioglitazone was associated with a 30% reduction in myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke197. Pioglitazone is commonly used in China (5.6–17.0% of people with T2DM who are treated with oral agents)169,170 and India (regularly prescribed by 56.2% of Indian physicians)198,199.

SGLT2 inhibitors

Several meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors are probably similarly200,201 or more186 effective in reducing blood levels of glucose and body weight, and similarly effective in reducing the incidence of adverse cardiovascular events202, in Asian people and people who were not Asian or white people. It is unknown whether these effects might differ between Indian people and Chinese people186,200. Although SGLT2 inhibitors are widely recommended among Asian populations203–205, data on the real-world use of SGLT2 inhibitors in China and India are scarce. In Hong Kong, the use of SGLT2 inhibitors increased rapidly from 2015 to 2016 (0.04% to 0.4% of non-insulin glucose-lowering medications)178. In India, the availability of low-cost remogliflozin and future generic options will probably expand the uptake of this class168,206.

GLP1 receptor agonists

In a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial, the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) receptor agonist liraglutide lowered blood levels of glucose by a similar degree among south Asian people and western European people207. A meta-analysis comparing 19 studies including predominantly white participants with three studies including predominantly Asian participants found that the glucose-lowering efficacy of GLP1 receptor agonists was similar across both groups186. A similar meta-analysis reported that the glucose-lowering effectiveness seemed to be similar among Asian people and people who are not Asian regardless of baseline weight208.

Previous meta-analyses comparing cardiovascular risk reduction among Asian people and people who are not Asian reported mixed findings209,210, but an updated meta-analysis of six cardiovascular outcome trials for GLP1 receptor agonists reported that reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events were greater among Asian people than in white people202. Emerging evidence suggests that GLP1 receptor agonists could be more effective when initiated early in the course of disease among people with adequate β-cell function211. In the prospective observational Predicting Response to Incretin Based Agents study, long duration of diabetes mellitus, low C-peptide concentrations, treatment with insulin and positive GAD or islet antibodies were associated with reduced lowering of blood levels of glucose211. However, a post hoc analysis of A Study in Participants With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus found that dulaglutide lowered blood levels of glucose similarly among people with high and low titres of GAD antibodies212. In China, a retrospective cohort study reported that those with a shorter duration of T2DM and a higher baseline HbA1c had greater reductions in levels of glucose with exenatide213, a finding that has been replicated in Korean people214. Similar studies have not been conducted among Indian people. GLP1 receptor agonists are not commonly used in India168 or China170,178 owing to barriers such as high costs215.

Conclusions

Although the massively growing burden of T2DM in India and China has been strongly driven by rapid urbanization, these populations also have an inherent, shared predisposition to deficient insulin secretion. This susceptibility confers an increased risk of severe insulin-deficient diabetes mellitus occurring even among lean people at young ages <40 years. Other subtypes of T2DM also seem to present earlier in life and with lower β-cell function, lower insulin resistance and lower BMI among Chinese people and most Indian people compared with European people. These distinctions are key to deciphering the unique responses to glucose-lowering medications among Indian and Chinese populations. In particular, incretin-based therapies have a key role in enhancing pancreatic β-cell function in these populations, providing effective glucose lowering with DPP4 inhibitors and providing highly effective glucose lowering with GLP1 receptor agonists if initiated early in the course of disease when β-cell function is still fairly well preserved. Informed by these differences, future precision medicine strategies should be adapted, recalibrated and rigorously validated among Indian and Chinese populations. In particular, better treatments tailored to phenotype are required for those diagnosed at the youngest ages, and further work is required to identify effective early combination therapies. Future research will need to integrate basic sciences, clinical, epidemiological, genetic and other sources of data216 to better characterize and treat the unique pathophysiology and phenotypes of T2DM in India and China, and throughout their global diasporas.

Acknowledgements