Abstract

Background:

Outcomes are thought to be worse in head and neck (H&N) melanoma patients. However, definitive evidence of inferior outcomes in H&N melanoma in the modern era is lacking. We sought to ascertain whether H&N melanomas carry a worse prognosis than melanomas of other sites.

Methods:

All patients who underwent excision for primary melanoma by fellowship-trained surgical oncologists at a single institution from 2014 to 2020 were queried from the electronic medical record. Patients who had AJCC eighth edition stage I-III disease were included.

Results:

Of 1127 patients, 28.7% had primary H&N melanoma. H&N patients were more likely to be male, older, and present with more advanced AJCC stage. Median follow-up was 20.0 months (IQR 26.4). On multivariable analyses controlling for other variables, H&N melanoma was associated with worse RFS. Notably, H&N melanoma was not associated with worse MSS, DMFS, or OS on univariate or multivariable analyses. Among patients who recurred, H&N patients were significantly more likely to recur locally compared to non-H&N patients. On subgroup analysis, scalp melanoma was also associated with worse RFS compared to patients with melanoma in locations other than the scalp. When patients with scalp melanoma were excluded from analysis, non-scalp H&N RFS was not significantly different from the non-H&N group on univariate or multivariable analyses.

Discussion:

In this series from a high-volume tertiary referral center, the differences in rates and sites of recurrence between H&N and non-H&N melanoma do not impact melanoma-specific or overall survival, suggesting that H&N melanoma patients should be treated similarly with respect to regional and systemic therapies.

Keywords: Head/neck, melanoma

Background

The historical association of cutaneous head and neck (H&N) melanoma with poor outcomes compared to melanomas of other anatomic sites has been well established. Several studies over the past decades have demonstrated inferior recurrence-free and/or overall survival.1–4 Several key differences have been identified between H&N and non-H&N melanoma that may account for these survival discrepancies. For example, in many series, H&N patients tend to be male and of more advanced age.5 Unlike truncal and extremity melanomas, which are primarily managed by surgical oncologists, head and neck melanomas are often treated by surgeons of varying specialties such as plastic and reconstructive surgery, otorhinolaryngology, and oral and maxillofacial surgery. Furthermore, the utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has been called into question due to concerns regarding feasibility and high rate of false negatives3,6,7; consequently, widespread adoption of SLNB in H&N melanoma patients is more limited than for melanomas of other sites, and approaches for nodal sampling and dissection among surgeons within the United States vary widely.8 Head and neck melanomas are also often near many critical anatomic structures, which are supplied by rich and variable vasculature and lymphatics. Cosmetically and functionally sensitive structures frequently limit the feasibility of resection with wide margins,9 and/or demand advanced reconstructive techniques for adequate closure of the resection bed.10

However, there is a paucity of data examining these survival patterns in the context of contemporary melanoma management. The introduction of immunotherapy and targeted and regional therapies has transformed the treatment of melanoma over the past decade and has resulted in dramatic improvements in survival.11 Especially in light of evolving neoadjuvant and surgical treatment, it is critical to identify and analyze an appropriately modern patient data set in order to contextualize treatment strategies moving forward. This study aims to describe a contemporary data set of H&N melanoma patients treated at a single institution by a single surgical subspecialty to minimize variability in treatment strategies and clinical experience. We also aim to determine if H&N melanoma treated in the contemporary era portends a worse prognosis than melanomas of other anatomic locations and identify any evidence indicating a biological difference, including recurrence patterns, between melanomas of different anatomic sites. We hypothesize that patients with melanomas of the H&N have similar outcomes to non-H&N melanomas and therefore should undergo similar locoregional surgical management.

Methods

This study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Data from patients with AJCC eighth edition stage I-III cutaneous melanoma diagnosed between October 1, 2013 and January 2019 and treated by fellowship-trained surgical oncologists at a single institution were queried. All adult patients with biopsy-proven cutaneous melanoma who underwent wide excision and who had at least one follow-up appointment were included. Minors, patients with melanoma of unknown primary, patients with stage 0 or stage IV disease, and patients for whom no post-surgical follow-up data are available were excluded.

Descriptive statistics with chi-square test were reported for all patients meeting inclusion criteria. These included age at diagnosis, sex, race, T stage, N stage, and overall stage as well as follow-up time (calculated as time from initial surgery to last clinic visit or death). Recurrence-free survival was defined as time in months from initial surgery to either recurrence or last follow-up (patients were censored at last clinical follow-up if they had not experienced recurrence). Distant metastasis-free, overall, and melanoma-specific survival were defined as time in months from initial surgery to the event (distant disease progression, death, or death due to melanoma, respectively) or censored at last clinical follow-up if the event had not occurred. Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests were generated to compare groups for each outcome. The univariate cox regression analysis was used to test the effect of each independent covariate on survival outcome. Multivariable analyses were performed using Cox regression analysis including the primary variable of interest (H&N vs non-H&N) as well as covariates identified on univariate analyses.

Subsequent descriptive and outcome analyses were performed on patients with primary scalp melanoma. An additional analysis was performed by excluding all patients who did not recur; descriptive statistics with chi-square test were generated for these groups. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27, Armonk, NY.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of patients queried, 1127 met criteria for inclusion. Of these, 324 (28.7%) were H&N primary melanomas, including 144 (% of entire cohort) primary scalp melanomas. Head and Neck melanoma patients were significantly more likely to be older (median age 67.0 years [IQR 19.0] vs 60.0 years, [20.0], P<.01), male (75.9% vs 55.7%, P<.01), and present with a more advanced AJCC eighth edition stage (53.1% vs 61.5% stage I, 31.5% vs 22.8% stage II, and 15.4% vs 15.7% stage III, P<.01). Race (P = .79), T stage (P = .08), N stage (P = .57), and follow-up time (P = .1) were not significantly different between groups. Receipt of adjuvant immunotherapy was also not different between groups (P = .98). Head and Neck melanoma patients were more likely to have narrower margins employed at their initial surgery (5.6% vs 1.4% <1 cm margin, 65.4% vs 62.3% 1 cm, and 12.7% vs 21.9% 2 cm margin, P<.01) and more likely to have excision specimens positive for melanoma at the margins (21.0% vs 7.8%, P<.01) (Supplementary Table 1).

Survival Analyses

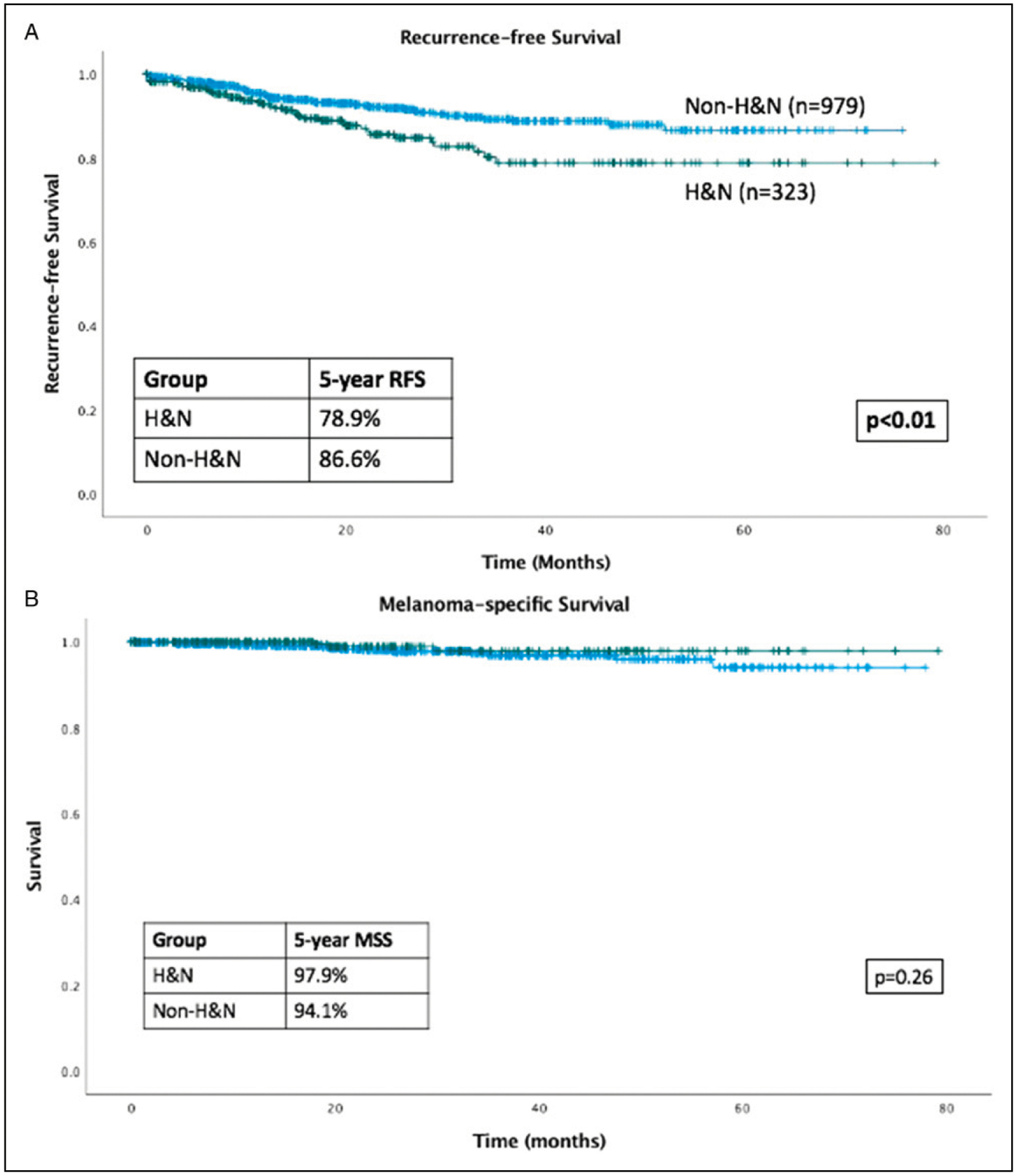

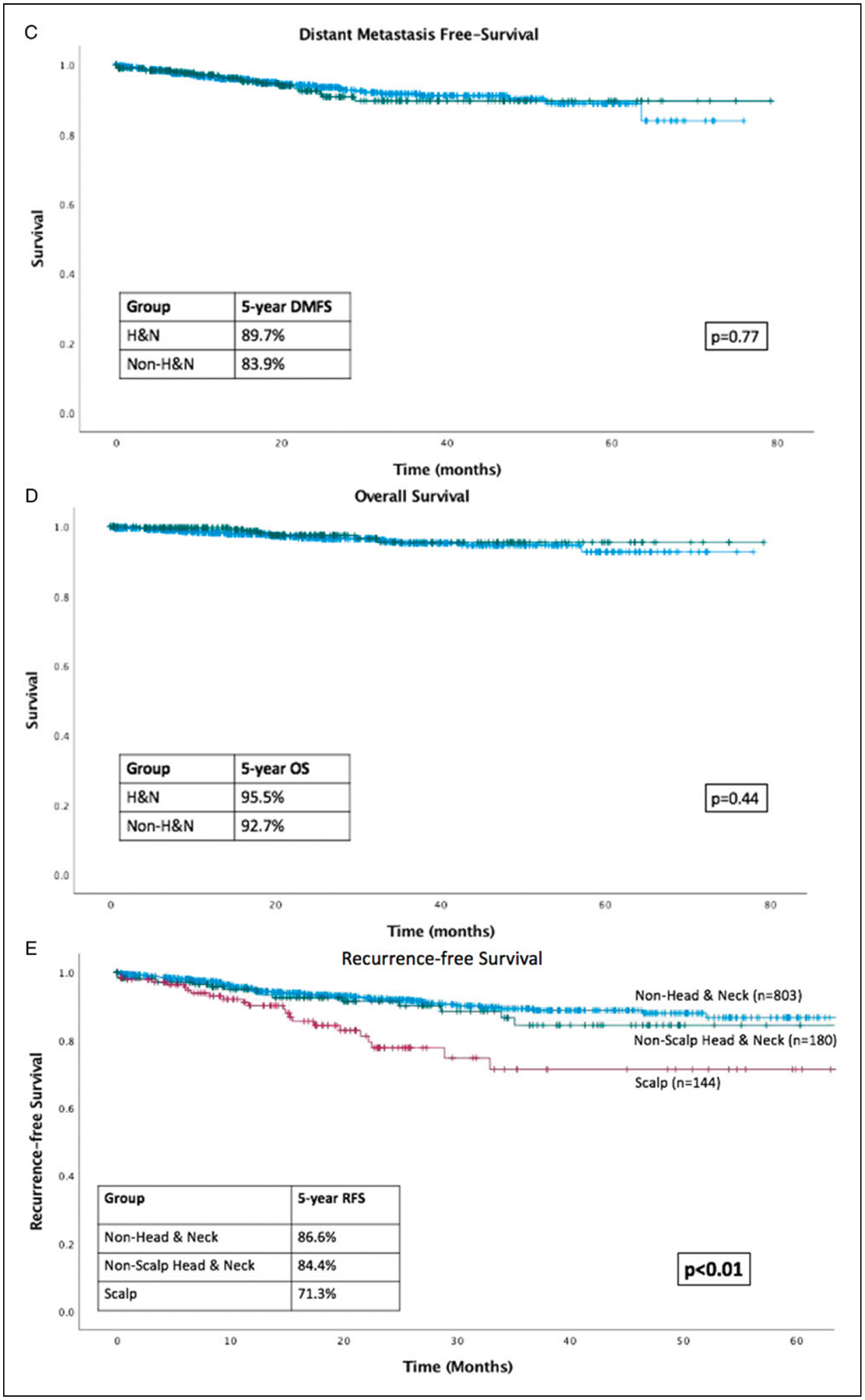

At a median follow-up of 20.0 months, H&N melanoma was associated with worse RFS (HR = 1.79; 95% CI 1.19–2.69, P<.01) compared to non-H&N (Figure 1A). This difference remained significant on multivariable analysis accounting for age, sex, T stage, and N stage (Table 1). Head and Neck melanoma was not associated with a difference in DMFS, OS, or MSS on univariate analyses (Table 2, Figure 1 B–D).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves. (A) RFS is inferior in head and neck (H&N) vs non-H&N patients; (B) MSS is equivalent in H&N vs non-H&N patients; (C) DMFS is equivalent in H&N vs non-H&N patients; (D) OS is equivalent in H&N vs non-H&N patients; (E) RFS is inferior in scalp patients compared to non-scalp H&N and non-H&N patients.

Table 1.

Univariate and Multivariable Outcomes Analyses for Head and Neck (H&N) vs Non-H&N Patients.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Recurrence-free survival | 1.79 (1.19–2.69) | <.01 | 1.64 (1.07–2.53) | .02 |

| Melanoma-specific survival | .51 (.15–1.77) | .29 | .50 (.14–1.76) | .28 |

| Overall survival | .737 (.318–1.712) | .48 | .64 (.27–1.51) | .31 |

| Distant metastasis-free survival | 1.11 (.65–1.90) | .71 | .97 (.55–1.72) | .92 |

Table 2.

Univariate Outcomes Analyses for All Variables.

| RFS | MSS | OS | Distant metastasis-free survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age at diagnosis (median, range) | 1.015 (1.00–1.03) | .04 | 1.01 (.98–1.05) | .48 | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | .02 | 1.01 (.99–1.03) | .37 | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Female | .608 (.390–.950) | .03 | .78 (.29–2.07) | .61 | .74 (.35–1.58) | .44 | .62 (.36–1.08) | .09 | |

| T Stage | |||||||||

| 1 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| 2 | 3.34 (1.48–7.56) | <.01 | .94 (.09–10.39) | .96 | 1.86 (.47–7.44) | .38 | 2.49 (.86–7.17) | .09 | |

| 3 | 9.89 (4.72–20.73) | <.01 | 5.60 (1.02–30.57) | .05 | 4.18 (1.18–14.80) | .03 | 9.02 (3.60–22.59) | <.01 | |

| 4 | 15.15 (7.28=31.54) | <.01 | 21.01 (4.65–94.92) | <.01 | 15.83 (5.32–47.07) | <.01 | 17.51 (7.22–42.44) | <.01 | |

| N Stage | |||||||||

| 0 or not assessed | - | - | - | - | |||||

| 1 | 4.80 (2.98–7.72) | <.01 | 4.50 (1.51–13.42) | <.01 | 2.43 (.98–6.06) | .06 | 5.08 (2.87–8.99) | <.01 | |

| 2 | 6.61 (3.50–12.49) | <.01 | 5.44 (1.18–25.22) | .03 | 2.42 (.57–10.35) | .23 | 5.68 (2.50–12.92) | <.01 | |

| 3 | 16.10 (8.10–31.98) | <.01 | 13.74 (2.95–63.94) | <.01 | 9.31 (2.76–31.43) | <.01 | 13.13 (5.46–31.58) | <.01 | |

| AJCC 8th ed. Stage | |||||||||

| 1 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| 2 | 5.31 (2.83–9.95) | <.01 | 8.13 (1.69–39.14) | <.01 | 4.30 (1.72–10.79) | <.01 | 6.76 (3.02–15.11) | <.01 | |

| 3 | 14.20 (7.84–25.71) | <.01 | 17.72 (3.83–82.02) | <.01 | 6.18 (2.39–15.94) | <.01 | 16.28 (7.50–35.36) | <.01 | |

| Head and neck | |||||||||

| No | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Yes | 1.79 (1.19–2.69) | <.01 | .51 (.15–1.77) | .29 | .737 (.318–1.712) | .48 | 1.11 (.65–1.90) | .71 | |

| Scalp | |||||||||

| No | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Yes | 2.39 (1.44–3.96) | <.01 | .40 (.052–3.01) | .37 | .73 (.22–2.42) | 0.6 | 1.13 (.54–2.33) | .75 | |

Primary scalp melanoma was also associated with worse RFS on univariate analysis compared to non-scalp melanoma (including non-scalp H&N, truncal, and extremity). When patients with scalp melanoma were excluded from analyses, there was no difference in RFS between H&N and non-H&N patients (HR 1.30, CI 0.73–2.34, P = .38). Characteristics of the patients with scalp melanoma were compared to non-scalp melanoma patients. Scalp patients were more likely to be older, male, and presented with a higher T and overall stage (all P<.05) compared to non-scalp patients; race and N stage were equivalent between groups (all P>.05). On univariate analysis, RFS was significantly worse for scalp patients (HR 2.39, CI 1.44–3.96, P<.01) compared to non-scalp, but there was no difference in DMFS, OS, and MSS. Three-way Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the non-H&N, non-scalp H&N, and scalp recurrence-free survival with non-H&N recurring the least and scalp the most (P<.01, Figure 1 E). On multivariable analyses accounting for age, sex, T stage, and N stage as well as scalp and/or H&N location, neither scalp nor H&N location was significantly associated with worse RFS compared to non-H&N (P = .35 and .43, respectively).

Patterns of Recurrence

Most patients (n = 1026, 91.4%) did not experience recurrence during the follow-up period. Overall rate of local recurrence was 2.8% (n = 31); in transit recurrence was 2.0% (n = 22); nodal recurrence was 1.6% (n = 19); and rate of distant metastasis as first site of recurrence was 2.0% (n = 23) (Supplementary Table 2). Of the 95 patients who recurred, 39 (41.1%) were H&N patients and 56 (58.9%) were non-H&N. Head and Neck and non-H&N patients underwent similar frequency of SLNB (69.2% for H&N vs 76.8% for non-H&N) and lymph node dissection (10.3% vs 8.9% for non-H&N) during initial treatment (P = .69); furthermore, rates of sentinel node positivity were similar between the groups (53.8% H&N vs 44.6% non-H&N, P = .34). Head and Neck patients were more likely to require advanced reconstructive techniques for closure (skin graft or tissue transfer) (Table 3). The majority of H&N patients recurred locally, whereas non-H&N patients were more likely to recur at in transit, nodal, or distant sites (Table 3). Among those who recurred locally, there was no significant difference in the category of margins that were used for the initial excision (<1 cm, 1 cm, or greater than or equal to 2 cm) or initial margin positivity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of All Patients Who Recurred, and Comparisons Between H&N vs Non-H&N and Scalp vs Non-Scalp Patients.

| All patients who recurred | All patients n = 95 | Head and neck n = 39 | Non-head and neck n = 56 | Chi-square | Scalp n = 23 | Non-scalp n = 72 | Chi-square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodal sampling | .69 | 0.4 | ||||||

| None | 16 (16.8) | 8 (20.5) | 8 (14.3) | 6 (26.1) | 10 (13.9) | |||

| SLNB | 70 (73.7) | 27 (69.2) | 43 (76.8) | 15 (65.2) | 55 (76.4) | |||

| LND | 9 (9.5) | 4 (10.3) | 5 (8.9) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (9.7) | |||

| Nodal positivity | .34 | .15 | ||||||

| None | 46 (47.9) | 21 (53.8) | 25 (44.6) | 14 (60.9) | 32 (44.4) | |||

| 1 or more | 50 (52.1) | 18 (46.2) | 32 (57.1) | 9 (39.1) | 41 (56.9) | |||

| Type of reconstruction | <.01 | <.01 | ||||||

| Primary closure | 67 (70.5) | 18 (46.2) | 49 (87.5) | 8 (34.8) | 59 (81.9) | |||

| Skin graft | 18 (18.9) | 17 (43.6) | 1 (1.8) | 14 (60.9) | 4 (5.6) | |||

| Tissue transfer/pedicled flap | 6 (6.3) | 4 (10.3) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.3) | 5 (6.9) | |||

| Secondary intention | 4 (4.2) | 0 | 4 (7.1) | 0 | 4 (5.6) | |||

| Site of recurrence | .01 | .35 | ||||||

| Local | 31 (32.6) | 20 (51.3) | 11 (19.6) | 11 (47.8) | 20 (27.8) | |||

| In transit | 22 (23.2) | 6 (15.4) | 16 (28.6) | 4 (17.4) | 18 (25.0) | |||

| Nodal | 19 (20.2) | 6 (15.4) | 13 (23.2) | 4 (17.4) | 15 (20.8) | |||

| Distant | 23 (24.2) | 7 (17.9) | 16 (28.6) | 4 (17.4) | 19 (26.4) | |||

| All patients who recurred locally | All patients n = 31 | Head and neck n = 20 | Non-head and neck n = 11 | Chi-square | Scalp n = 11 | Non-scalp n = 20 | Chi-square | |

| Margin width | .93 | .46 | ||||||

| <1 cm | 2 (6.5) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.0) | |||

| 1 cm | 13 (41.9) | 8 (40.0) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (36.4) | 9 (45.0) | |||

| 2 cm | 14 (45.2) | 9 (45.0) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 8 (40.0) | |||

| Other | 2 (6.5) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Initial margin | .12 | .47 | ||||||

| Negative | 23 (74.2) | 13 (65.0) | 10 (90.9) | 9 (81.8) | 14 (70.0) | |||

| Positive | 8 (25.8) | 7 (35.0) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (18.1) | 6 (30.0) |

Discussion

This analysis of a large single-institution data set of patients with stage I-III cutaneous melanoma demonstrates that although H&N melanoma is associated with inferior RFS, there is no difference in overall survival, melanoma-specific survival, or distant metastasis-free survival.

Characteristics of our patient population are comparable to those found in the literature; frequency of H&N cutaneous melanoma is typically reported as between 20 and 30% of all cutaneous melanomas,9,12–14 although some papers and series report lower frequencies.15–17 Demographics associated with H&N location were also similar to published findings, with H&N melanomas being more frequently associated with male sex and older age.9,18

Investigations of histopathologic subtypes of H&N melanoma compared to melanoma of other sites have not revealed any evidence to suggest that H&N melanoma is a biologically distinct entity.18 There is, however, myriad evidence demonstrating that scalp melanoma tends to present with increased Breslow depth and presence of ulceration, and that scalp subsite is associated with inferior survival outcomes.17,19–22 The current study adds to the data condemning scalp subsite as a particular contributor to increased risk of recurrence. However, our series demonstrates the important finding that neither scalp nor H&N site is associated with worse overall or melanoma-specific survival. A 2017 study of scalp melanoma patients over the past two decades demonstrated similar findings regarding OS,23 although in that study there was an association with inferior MSS on univariate analyses. In our study including only patients treated since 2014, H&N site was not associated with inferior MSS. Other studies have further stratified this population and identified the posterior scalp as a particular site of poor prognosis with worse MSS compared to other sites with similar clinicopathologic variables, in which the authors attribute specifically to the increased sun exposure.24 The same study also demonstrated that melanomas of the forehead, cheeks, ears, and lips were not particularly associated with inferior MSS, which further substantiates our results.

Recurrence-free survival in our H&N cohort was significantly higher than rates reported elsewhere in the literature.3,22,25 This may be due in part to the shorter median follow-up time of 20.0 months in this study; however, this patient cohort also represents a group of patients who underwent treatment much more recently than in many published studies. With the improvements in outcomes resulting from advancements in systemic and regional therapies in the past decade, it is both reasonable and encouraging to see that these benefits may have extended to the H&N population. As these patients’ age and longer follow-up times are obtained, it will be critical to continue to assess the survival of these patients and the long-term outcomes for patients who are treated in the modern era.

Another element of historical concern regarding surgical management of H&N melanoma is that of the false negative sentinel node biopsy. Data addressing this issue are controversial; many researchers have found that the rate of false negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in H&N melanomas is higher than that of melanomas of other sites.26–28 Results of MSLT-II indeed found a near-significant association with MSS favoring CLND in H&N patients.16 However, still others have identified SLNB as an important and reasonably accurate tool for diagnosing nodal metastases in H&N melanoma.7,13,29 In our study, we found that despite the comparable N stage between groups determined at initial treatment, the rate of false negatives (ie, those who went on to develop nodal recurrence) among those who recurred was in fact lower than that of other sites. In context of the entire cohort, only 6 H&N patients (of 324 total H&N, 1.9%) recurred in the nodal basin where the SLN biopsy was performed, whereas 13 non-H&N (of 803 total non-H&N, 1.6%) recurred in the same nodal basin (P = .57). These data provide a compelling argument that in a well-controlled setting with highly trained surgeons and near-uniform surgical management, the rate of false negative SLNB in the H&N population is negligible compared to melanomas of other sites. This argues against the employment of uniform CLND in H&N patients or studies that mandate CLND as part of the treatment protocol. Furthermore, the increased risk of recurrence in this study’s H&N population was due to local recurrence. Consequently, we posit that risk of local rather than nodal recurrence should drive surveillance patterns in this population.

The present study demonstrates a propensity of H&N melanoma to preferentially recur locally. When examining solely the patients who did recur locally, there was no significant difference between margin width or positivity. Among the entire cohort, however, our data set revealed a higher frequency of margin positivity and use of narrower margins in H&N patients, which has been documented elsewhere.9 This provides a strong argument against the notion that H&N melanoma behaves as a unique biologic entity: margin status is similar in those who will recur locally, regardless of melanoma site, and the increase in relative frequency of local recurrence in H&N patients may be explained by limited margins due to anatomic and cosmetic restrictions on the initial operation.

Several strengths of this study are the large number of patients included and the recent time frame within which treatment was provided. Additionally, all operative interventions were performed within the same institution by highly trained surgical oncologists, which allows for a high degree of confidence in the uniformity of nodal assessment. However, some may argue that this could also be a limitation of this study, as it could hinder applicability to a larger population. Additional limitations include all those inherent in a retrospective study, as well as assessments being made on a relatively small population of patients with unfavorable survival outcomes.

In summary, despite a higher rate of recurrence in H&N melanoma patients, overall and melanoma-specific survival as well as distant metastasis-free survival are equivalent between groups, and therefore H&N melanoma should be similarly to melanoma of other sites. Furthermore, we demonstrate that SLNB false negative rate is similar in H&N and other melanoma patients, and that higher risk of local recurrence should guide surveillance considerations in this population.

Supplementary Material

Key Takeaways.

Head and neck melanoma patients have inferior recurrence-free survival compared to patients with melanoma of other sites but have equivalent melanoma-specific and overall survival.

The difference in recurrence-free survival is driven in part by a subset of patients with scalp melanoma.

In the event of a recurrence after initial surgical treatment, head and neck patients are more likely to recur locally than patients with melanoma of other sites.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Garbe C, Büttner P, Bertz J, et al. Primary cutaneous melanoma prognostic classification of anatomic location. Cancer. 1995;75(10):2492–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher SR, Seigler HF, George SL. Therapeutic and prognostic considerations of head and neck melanoma. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;28(1):78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachar G, Tzelnick S, Amiti N, Gutman H. Patterns of failure in patients with cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(5):914–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thörn M, Adami HO, Ringborg U, Bergström R, Krusemo U. The association between anatomic site and survival in malignant melanoma an analysis of 12,353 cases from the swedish cancer registry. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1989; 25(3):483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Višnjić A, Kovačević P, Veličkov A, Stojanović M, Mladenović S. Head and neck cutaneous melanoma: 5-year survival analysis in a Serbian university center. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18(1):312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lentsch EJ, McMasters KM. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma of the head and neck. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2003;3(5):673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanks JE, Kovatch KJ, Ali SA, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck melanoma: Long-term outcomes, prognostic value, accuracy, and safety. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(4):520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawh-Martinez R, Douglas S, Pavri S, Ariyan S, Narayan D. Management of head and neck melanoma: Results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73(suppl 2): S175–S177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Qurayshi Z, Hassan M, Srivastav S, et al. Risk and survival of patients with head and neck cutaneous melanoma: National perspective. Oncology. 2017;93(1):18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namin AW, Cornell GE, Smith EH, Zitsch RP III. Considerations for timing of defect reconstruction in cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Facial Plast Surg. 2019; 35(4):404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrow NE, Turner MC, Salama AKS, Beasley GM. Overall survival improved for contemporary patients with melanoma: A 2004–2015 national cancer database analysis. Oncol Ther. 2020;8(2):261–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Rosa N, Lyman GH, Silbermins D, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for head and neck melanoma: A systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(3):375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evrard D, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(5):1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina JE, Ferlito A, Brandwein MS, et al. Current management of cutaneous malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122(8):900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigual NR, Popat SR, Jayaprakash V, Jaggernauth W, Wong M. Cutaneous head and neck melanoma: The old and the new. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8(3):403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Completion dissection or observation for sentinel-node metastasis in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2211–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porto AC, Pinto Blumetti T, Oliveira Santos Filho IDA, Calsavara VF, Duprat Neto JP, Tavoloni Braga JC. Primary cutaneous melanoma of the scalp: Patterns of clinical, histological and epidemiological characteristics in Brazil. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0240864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoersch B, Leiter U, Garbe C. Is head and neck melanoma a distinct entity? A clinical registry-based comparative study in 5702 patients with melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(4):771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozao-Choy J, Nelson DW, Hiles J, et al. The prognostic importance of scalp location in primary head and neck melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116(3):337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saaiq M, Zalaudek I, Rao B, et al. A brief synopsis on scalp melanoma. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wee E, Wolfe R, McLean C, Kelly JW, Pan Y. The anatomic distribution of cutaneous melanoma: A detailed study of 5141 lesions. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(2):125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terakedis BE, Anker CJ, Leachman SA, et al. Patterns of failure and predictors of outcome in cutaneous malignant melanoma of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3): 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie C, Pan Y, McLean C, Mar V, Wolfe R, Kelly J. Impact of scalp location on survival in head and neck melanoma: A retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017; 76(3):494–498. e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard MD, Wee E, Wolfe R, McLean CA, Kelly JW, Pan Y. Anatomic location of primary melanoma: Survival differences and sun exposure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 81(2):500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sparks DS, Read T, Lonne M, et al. Primary cutaneous melanoma of the scalp: Patterns of recurrence. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(4):449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penicaud M, Cammilleri S, Giorgi R, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck melanoma: A single institution analysis. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2014; 135(3):115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller MW, Vetto JT, Monroe MM, Weerasinghe R, Andersen PE, Gross ND. False-negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck melanoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(4):606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saltman BE, Ganly I, Patel SG, et al. Prognostic implication of sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Head Neck. 2010;32(12):1686–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Passmore-Webb B, Gurney B, Yuen HM, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma of the head and neck: A multicentre study to examine safety, efficacy, and prognostic value. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57(9):891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.