Abstract

Introduction:

Hematologic malignancies are cancers of the blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes and represent a heterogenous group of diseases that affect people of all ages. Treatment generally involves chemotherapeutic or targeted agents that aim to kill malignant cells. In some cases, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) is required to replenish the killed blood and stem cells. Both disease and therapies are associated with pulmonary complications. As survivors live longer with the disease and are treated with novel agents that may result in secondary immunodeficiency, airway diseases and respiratory infections will increasingly be encountered. To prevent airways diseases from adding to the morbidity of survivors or leading to long-term mortality, improved understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of viral bronchiolitis, BOS, and bronchiectasis is necessary.

Areas covered:

This review focuses on viral bronchitis, BOS and bronchiectasis in people with haematological malignancy. Literature was reviewed from Pubmed for the areas covered.

Expert opinion:

Airway disease impacts significantly on hematologic malignancies. Viral bronchiolitis, BOS and bronchiectasis are common respiratory manifestations in haematological malignancy. Strategies to identify patients early in their disease course may improve the efficacy of treatment and halt progression of lung function decline and improve quality of life.

Keywords: haematologic malignancy, graft versus host disease, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, bronchiectasis, airway disease, viral bronchitis

Introduction

Hematologic malignancies are cancers of the blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes and represent a heterogenous group of diseases that affect people of all ages. The estimated prevalence of haematologic malignancy in the UK and USA are similar and range from 282 to 549 per 100 000 people1. Treatment generally involves chemotherapeutic or targeted agents that aim to kill malignant cells. In some cases, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) is required to replenish the killed blood and stem cells. Both disease and therapies are associated with pulmonary complications. In this review we explore the wider impact of incident airway disease in hematologic malignancies and discuss three specific conditions: viral bronchiolitis, pulmonary graft-versus-host disease - bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), and bronchiectasis. This review will not discuss airway diseases that predate the diagnosis of hematologic malignancies. Other infectious and non-infections complications of hematologic malignancy, including interstitial and pleural diseases, are well described and discussed elsewhere2,3.

Viral bronchiolitis

Respiratory viral infections are a common occurrence in the general population, but more often result in severe disease and poorer outcomes in patients with hematologic malignancies4. Influenza and the pneumovirus respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)5, and paramyxoviruses, including parainfluenza virus (PIV)6 and human metapneumovirus (hMPV)7 are well known to cause high mortality in immunocompromised patients with lower respiratory infection. However, even respiratory viruses that are typically considered to cause mild “common colds”, such as rhinovirus and coronavirus, are associated with more severe outcomes in patients with hematologic malignancies8,9.

Viral lower respiratory infections can present either as a bronchopneumonia or as acute airway inflammation in the form of bronchitis and bronchiolitis10. Bronchitis generally refers to inflammation of the large airways, while bronchiolitis refers to inflammation of the small airways. Small airways are classically defined as being less than 2 mm in diameter and lacking cartilage11; both of these elements are important in this classification, since up to 96% of airways in the 7th generation contain cartilaginous elements evident on optical coherence tomography despite a mean airway diameter of less than 2 mm12. On the other hand, most 9th generation airways and beyond lack cartilage. The presence or absence of airway cartilage is important, since the predisposition for small airways to collapse when inflamed heavily influences the increase in total airway resistance in obstructive airway diseases, due to the fact that small airways account for a large portion of total airway cross-sectional area13.

While small declines in pulmonary function are common after a viral infection in healthy adults14, severe acute bronchiolitis is rare. RSV infection is well known to cause acute bronchiolitis in children, affecting as many as 2–3% of children15. Co-infections with a second virus, such as hMPV, may lead to more severe bronchiolitis16. However, despite increasing the risk for future asthma17, long-term outcomes after RSV bronchiolitis in children remain generally good18. Adenovirus, while rarer, is associated with post-infectious bronchiolitis obliterans in children, causing permanent and sometimes progressive airflow obstruction19. Viral bronchiolitis is typically self-limiting in healthy adults20, though respiratory viruses are well known to cause airflow impairments in patients with asthma or smoking-related obstructive lung disease21. In addition, ongoing bronchiolitis is a likely cause for many prolonged post-viral cough syndromes22,23.

The exact incidence of viral bronchiolitis is difficult to isolate from that of viral bronchopneumonia in immunocompromised patients due to definitional overlap24. Most definitions require a combination of symptoms and radiographic findings in the presence of symptoms. However, mucus plugging, a common finding in viral bronchiolitis, can often manifest as a tree-in-bud nodular infiltrate on chest CT and be misinterpreted as “pneumonia”25. Furthermore, mucus plugs can be extensive in inflammatory airway diseases, causing subsegmental atelectasis that can be misinterpreted as a bronchopneumonia26. Finally, viral infection is well-known to increase the incidence of secondary bacterial pneumonia, possibly due to enhanced adhesion of bacteria to epithelial surfaces27. Therefore, a finding of a lobar infiltrate does not rule out bronchiolitis as the etiologic cause of clinical presentation.

Viral lower respiratory tract infections are common in patients with hematologic malignancy28. For example, in a study of 239 immunocompromised patients with RSV infection, nearly half presented with lower respiratory symptoms, which is nearly twice the rate of lower respiratory symptoms in healthy adults infected with RSV20,29. Furthermore, in a study of nearly 2900 allogeneic HCT recipients at a single institution, 2.5% (n=73) developed adenoviral infection30. Of these 73, 22% (n=16) died, mostly due to pneumonia. While risk factors for bronchiolitis, specifically, have not been identified in patients with hematologic malignancies, several studies have examined risk factors for the development of lower respiratory disease in the broader sense. Khanna et al identified that severe immunodeficiency, defined by characteristics such as lymphopenia or recent T- or B-cell depleting therapies, was more common in patients with lower respiratory RSV infection31. These criteria were validated in a larger study of viral infections with RSV, PIV, and hMPV; severe immunodeficiency was associated with higher rates of hospitalization, respiratory failure, and death after viral infection32. The Immunodeficiency Scoring Index (ISI) was specifically designed to measure rates of progression from upper to lower respiratory disease, and developed and validated initially in RSV infection33. Factors such as age, lymphopenia, and neutropenia were strongly predictive of subsequent pneumonia after RSV infection. Both scoring methods have been associated with death after RSV infection5,34. These studies show that hematologic malignancies that result in significant neutropenia (absolute count < 500 cells/uL) or lymphopenia (absolute count < 200 cells/uL) and exposure to corticosteroids, such as in the setting of HCT, are risk factors for the progression from upper to lower respiratory tract disease.

Long-term pulmonary impairments are also prevalent after respiratory viral infection in allogeneic HCT recipients. In a study of 223 allogeneic HCT recipients who survived respiratory viral infection with RSV, PIV, or influenza virus, 34% had declines in FEV1 of at least 10% following the infection35. Nearly 16% of these patients eventually developed graft-versus-host disease of the lung, and two-year non-relapse mortality was around 25% in patients with pulmonary function decline after respiratory viral infection, as compared to 8% in those without. Mortality was similar whether impairments were obstructive or restrictive. Viral infections are particularly common in the first 100 days after HCT 36 and are well known to result in high mortality rates (10–50%) with nearly every commonly-tested respiratory virus5,7,8,37,38. Similarly high mortality rates are noted in patients with leukemia who develop lower respiratory infections with PIV, RSV, or influenza6,39–41.

Viral lower respiratory infections clearly pose a significant burden to immunocompromised patients42, and in particular HCT recipients43. Viral lower respiratory infections, in general, are an under-recognized problem44. Therapies for viral lower respiratory infections are desperately needed, as most are ineffective once signs of lower respiratory disease manifest45,46. Furthermore, most antiviral agents are used off label for the targeted virus and evidence for their use is weak (Table 1). The use of novel strategies that broadly augment immune responses may be beneficial, since the mechanism of antiviral therapies are typically specific to a single virus47. Given the substantial impact of the novel SARS-CoV-2 pandemic coronavirus, we hope that the coming years will be more fruitful in developing a broad armamentarium of antiviral therapies.

Table 1:

Respiratory viruses and treatments used

| Virus | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Influenza | Neuraminidase inhibitors (zanamivir, peramivir oseltamivir) Polymerase inhibitors (baloxivir) Amantadine |

| Parainfluenza | Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)* |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Ribavarin** Palivizumab* IVIG* |

| Human metapneumovirus | IVIG* |

| Adenovirus | Cidofovir* Brincidofovir*** |

Off-label use (low level evidence)

Off-label use in immunocompromised patients

available through expandable access programme

Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation

HCT is an important curative option for many refractory or high-risk malignancies48. Over 50,000 HCTs are performed annually worldwide49. Allogeneic HCT is often required to achieve disease control in acute leukemias, particularly acute myeloid leukemia (AML)50. A major complication of allogeneic HCT is chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD), which occurs in about 40% of allogeneic HCT recipients 51. cGVHD is associated with lower rates of disease relapse, consistent with a more active graft-versus-tumor effect, but treatment-related mortality rises in parallel to the severity of cGVHD52. cGVHD is a major contributor to late mortality after allogeneic HCT and remains a critical problem for cancer survivors and treating physicians53.

Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) is increasingly being recognized as a source of treatment-related morbidity and mortality in HCT recipients54. BOS typically occurs later in the course of transplant, with a median onset around 15 months post-HCT55. The pathogenesis of BOS remains incompletely understood, though pre-clinical data in animal lung transplantation models implicate a depletion of airway progenitor stem cells56,57, likely in response to ongoing alloimmune inflammation and injury to the airway epithelium58. Pre-clinical models for post-HCT BOS have not been explored in significant detail, but suggest that B-cells and macrophages may play important roles in the pathogenesis59,60. Further pre-clinical work is necessary to identify events that trigger and perpetuate alloimmune inflammation in the context of post-HCT BOS.

Lymphocytic inflammation of the airways may be more present in early stages of BOS, fibroproliferative changes (or “constriction”) may be more indicative of a later stage of BOS10,61. Alternatively, these histopathologic features may indicate different subtypes of BOS, but recent work suggests that airway inflammation and fibrosis are often found in varying degrees concurrently62. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) define BOS as forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1) <75% of predicted values, in addition to a FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio <0.763, in the presence of an increased residual volume relative to total lung capacity or evidence of air trapping on imaging (Figure 1). Importantly, the NIH criteria may miss early BOS, particularly in those who had supranormal lung function prior to HCT and subsequently experienced a significant decline. Furthermore, the NIH criteria diagnose airflow obstruction in the form of a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio, but “pseudorestriction” can occur in BOS when FEV1 and FVC decline concurrently in the presence of small airway inflammation;64 concurrent declines in FEV1 and FVC are commonly seen in patients with cGVHD, and are associated with the development of BOS or death after HCT65. Pulmonary impairment of a lesser degree than stipulated by NIH criteria may signal the development of early BOS, but diagnosis of BOS at this stage (stage 0p) is associated with a high false positive rate66. Importantly, the diagnosis of BOS must be made in the absence of infection. Because 1) viral infections are well known to increase the risk for subsequent BOS67, 2) acute viral bronchiolitis may be indistinguishable from BOS, and 3) prolonged shedding of remote viral infections may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of viral bronchiolitis in the setting of BOS68, a firm diagnosis of BOS is often difficult to establish when first evaluating a patient. Other known risk factors include older age, pre-HCT airflow obstruction, and early declines in mid-flow expiratory rates69,70.

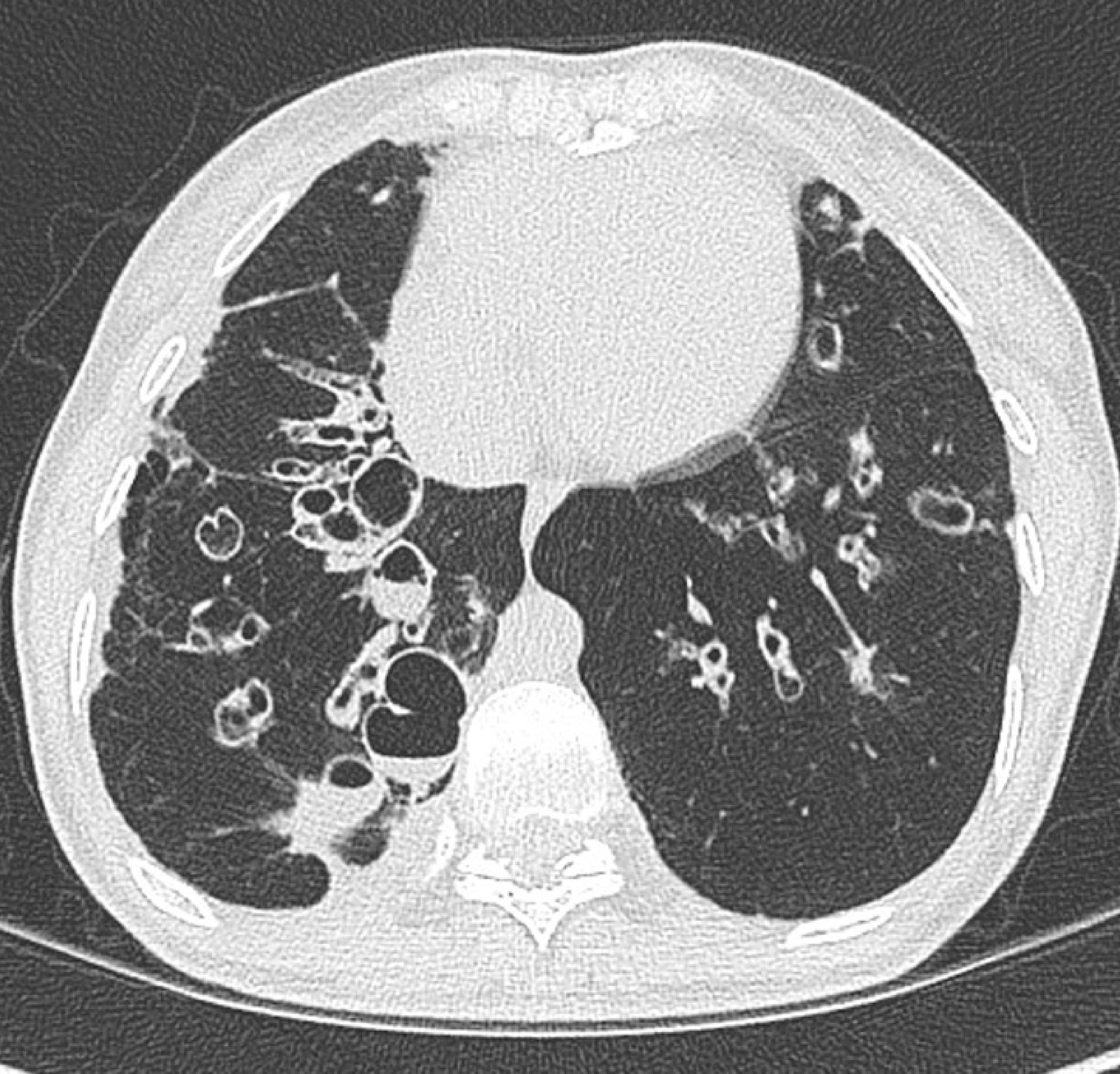

Figure 1:

CT Chest of a patient with pulmonary GVHD after HCT for AML. (right) Expiratory images demonstrate mosaicism secondary to air-trapping, (Left) Inspiratory images show bronchial wall thickening and early bronchiectasis.

Common symptoms of BOS include shortness of breath, chest tightness, and productive or non-productive cough. Symptoms often lag behind the development of pulmonary impairment as measure by spirometry71, and therefore symptoms cannot be a sole screening tool for early BOS. Diagnosing BOS early in its course may be beneficial, but detecting early BOS remains a challenge due to sporadic pulmonary function screening after the first year of HCT. Milder pulmonary impairment at the time of BOS diagnosis is associated with better long-term outcomes72, while disease onset earlier in the course of HCT is associated with a more severe course 73. Home spirometry may allow for more frequent screening of lung function without requiring HCT recipients to travel to a pulmonary function lab74–76. However, barriers to the implementation of efficient home spirometry screening programs include patient adherence, effective centralized transmission of pulmonary function data, and the likelihood of false-positive results due to variations in home spirometry technique. Newer techniques, such as quantitative computed tomographic (CT) imaging77 or hyperpolarized gas magnetic resonance imaging78, may improve the accuracy of diagnosing early BOS by accurately quantifying the degree of air trapping and ventilation defects. For example, paired inspiratory and expiratory CT images can be used to precisely quantify the burden of air trapping in the lung77. Newer techniques can quantify the amount of lung strain at the level of individual voxels, giving precise estimates for abnormalities in the mechanics of the lung79. Standardized image acquisition algorithms may allow for widespread implementation of these quantitative techniques80.

The treatment of BOS is primarily focused on reducing inflammation in the airways through inhaled and systemic anti-inflammatory agents. Inhaled corticosteroids, in combination with a course of oral corticosteroids and/or an increase in immunosuppression, are often effective in halting the progression of BOS81–83. Photopheresis can be useful as an adjunctive therapy, but requires an indwelling catheter and proximity to an apheresis center84. Other cGVHD therapies, such as ibrutinib85 and ruxolitinib86, may have some efficacy in BOS, but most efficacy data is derived from non-lung cGVHD syndromes. Inhaled cyclosporine was previously found to be effective to treat BOS after lung transplantation, but early formulations were associated with a high rate of adverse events87. Phase 3 studies of a newer liposomal formulation are underway to treat BOS in lung allograft recipients, and studies in patients with post-HCT BOS are planned. In dire cases, lung transplantation may be necessary88,89. Pulmonary rehabilitation is an underutilized supportive treatment that improves the functional capacity of patients with BOS90. Other supportive therapies, like inhaled hypertonic saline solution for airway clearance, may improve symptoms, but have not been shown to improve survival.

Azithromycin has recently come under scrutiny due to its association with higher rates of hematologic relapse after HCT when used as a prophylactic drug at the time of conditioning91. Azithromycin has been effective to slow the rate of allograft rejection in some lung transplant recipients92,93, presumably by attenuating the degree of airway inflammation. Results of azithromycin monotherapy in HCT recipients with BOS have been disappointing; a single-arm study suggested an improvement in FEV1, but this was not found in a more definitive randomized controlled trials94,95. The combination of inhaled corticosteroids, azithromycin, and montelukast stabilized lung function in uncontrolled studies of BOS72,96,97. A randomized controlled trial of azithromycin vs. placebo given at the time of HCT conditioning was prematurely halted due to lower survival and increase rates of cancer relapse91. This resulted in a Food and Drug Administration warning for prophylactic azithromycin use in HCT recipients. Importantly, azithromycin is typically given at the time of BOS, which occurs as rates of hematologic relapse are declining98. Subsequently, a study of 316 HCT recipients with BOS found no evidence of increased cancer relapse after azithromycin administration, but found an increase in subsequent neoplasms, most of which were skin cancers99. A second study found no evidence of increased cancer relapse in most HCT recipients, but found a concerning increase in the rate of relapse in matched unrelated donor transplant recipients who received anti-thymocyte globulin100. The use of azithromycin to treat post-HCT BOS remains controversial.

Survival after a diagnosis of BOS remains low, particularly in those who are found to have significant pulmonary impairment on diagnosis72. Mechanistic studies are necessary to unravel the pathophysiology that underpins the development and progression of BOS. Furthermore, diagnostic and screening platforms should leverage modern technologies to efficiently screen and accurately diagnose BOS at an early stage. Finally, trials of second-line therapies should examine outcomes specifically in BOS patients, as improved outcomes in cGVHD of other organs may not necessarily translate to improved outcomes for BOS.

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is defined as the permanent abnormal dilatation of one or more bronchi visualised on radiological imaging, often associated with bronchial wall thickening101. On axial CT images, the bronchial caliber is larger (a bronchial-artery ratio of greater than 1.5) than the accompanying artery at the same level due to lack of the normal airway tapering. Bronchiectasis, however, is only clinically significant when structural airway abnormalities are accompanied by chronic respiratory symptoms such as persistent cough, sputum production, and recurrent respiratory infections. Bronchiectasis itself is the end result of several pathophysiological processes that trigger Cole’s vicious cycle hypothesis of airway inflammation and/or infection that results in bronchial epithelial injury and subsequently promotes further inflammation, injury and infection102.

The pathogenesis for the development of bronchiectasis in individuals with hematologic malignancy has not been extensively investigated and likely differs amongst the different hematologic malignancies and those post-allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Hematologic malignancies often result in secondary immunodeficiency and the development of bronchiectasis in these patients is increasingly recognised. Indeed, case reports or series have described bronchiectasis occurring de novo in patients with hematologic malignancy103, particularly in those post-HCT, with lung GVHD and those with CLL104; in rare instances, bronchial wall infiltration can occur in CLL105. The incidence of bronchiectasis is increasing and the prevalence is highest amongst females and those over 60 years of age106. The mortality rate of bronchiectasis patients varies between studies and ranges from 16% to 30% in cohorts with 4 and 10 years of follow up107,108. In contrast to those without hematologic malignancy, patients with hematologic malignancy and bronchiectasis are younger and approximately two-thirds are male, in keeping with the characteristics of patients with myeloid and lymphoid malignancies109.

A significant proportion of cases with hematologic malignancy who develop bronchiectasis have had HCT with or without lung GHVD or exhibit IgG deficiency. These three factors, either alone or in combination, are present in approximately 80% of patients110, suggesting that secondary immunodeficiency contributes to the development of bronchiectasis in many of these individuals. Most hematologic malignancy patients with bronchiectasis receive intensive combination chemotherapy with drugs like fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, and rituximab111. These agents are known to cause immunosuppression, but also drug-related toxicity, and it is unknown if subclinical pulmonary toxicity could influence the development of bronchiectasis in addition to recurrent infections caused by the immunosuppression. However, the prolonged median duration between diagnosis of hematologic malignancy (3–5 years)110,111, when most of the chemotherapeutic agents would have been administered, and the development of bronchiectasis, suggests that direct drug toxicity likely does not play a major role. The exception is rituximab, as the study by José et al. showed that patients that received rituximab developed bronchiectasis more rapidly than those that had not received rituximab (40% vs 13% within 1 year of hematologic diagnosis)110. Rituximab was used in all patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, and over two-thirds of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma cases, which were the most common hematologic malignancies identified in their cohort with bronchiectasis110. Furthermore, the risk of IgG deficiency was 6-fold greater in those that received rituximab110. Overall, rituximab use appears to be an important factor in the development of bronchiectasis in hematologic malignancy alongside HCT and lung GVHD due to impairment in humoral immunity.

Bronchiectasis has three distinct radiological appearances consisting of cylindrical, varicose and cystic bronchiectasis; the last being associated with more severe disease (Figure 2). Most patients with hematologic malignancy that develop bronchiectasis have cylindrical bronchiectasis110. Using the modified Bhalla method that assesses bronchial dilatation and bronchial wall thickness, they have low radiological scores111, suggesting mild disease. However, half of patients with bronchiectasis have disease in 3 or more lobes at the time of diagnosis, suggestive that the diagnosis of bronchiectasis in many patients is only made when there is already widespread lung involvement. Furthermore, bronchiectasis often progresses over time. 110,111. Chen et al. also demonstrated that 45% of patients had at least one admission to hospital for the treatment of respiratory infection prior the diagnosis of bronchiectasis, indicating that likelihood of missed opportunities to confirm the diagnosis earlier, which could result in implementation of preventative strategies111. To prevent progression of bronchiectasis, individuals should be identified early in the course of disease. Primary care physicians and haematologists who often see these patients should have a high index of suspicion when patients with hematologic malignancies present with recurrent infections or with chronic productive cough. The isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the sputum should also raise suspicion for the presence of bronchiectasis. José et al found that 16% of bronchiectasis patients had evidence of bacterial colonisation, and half were colonised with Pseudomonas aeruginosa110. Similarly, Chen et al. found that 70% of patients had positive bacterial cultures, with P. aeruginosa isolated in 30%111. P. aeruginosa is an important pathogen in patients with bronchiectasis because of its natural resistance to most oral antibiotics and its impact on clinical outcomes. P. aeruginosa isolation from sputum is associated with reduced lung function 112, more frequent exacerbations and inferior quality of life113.

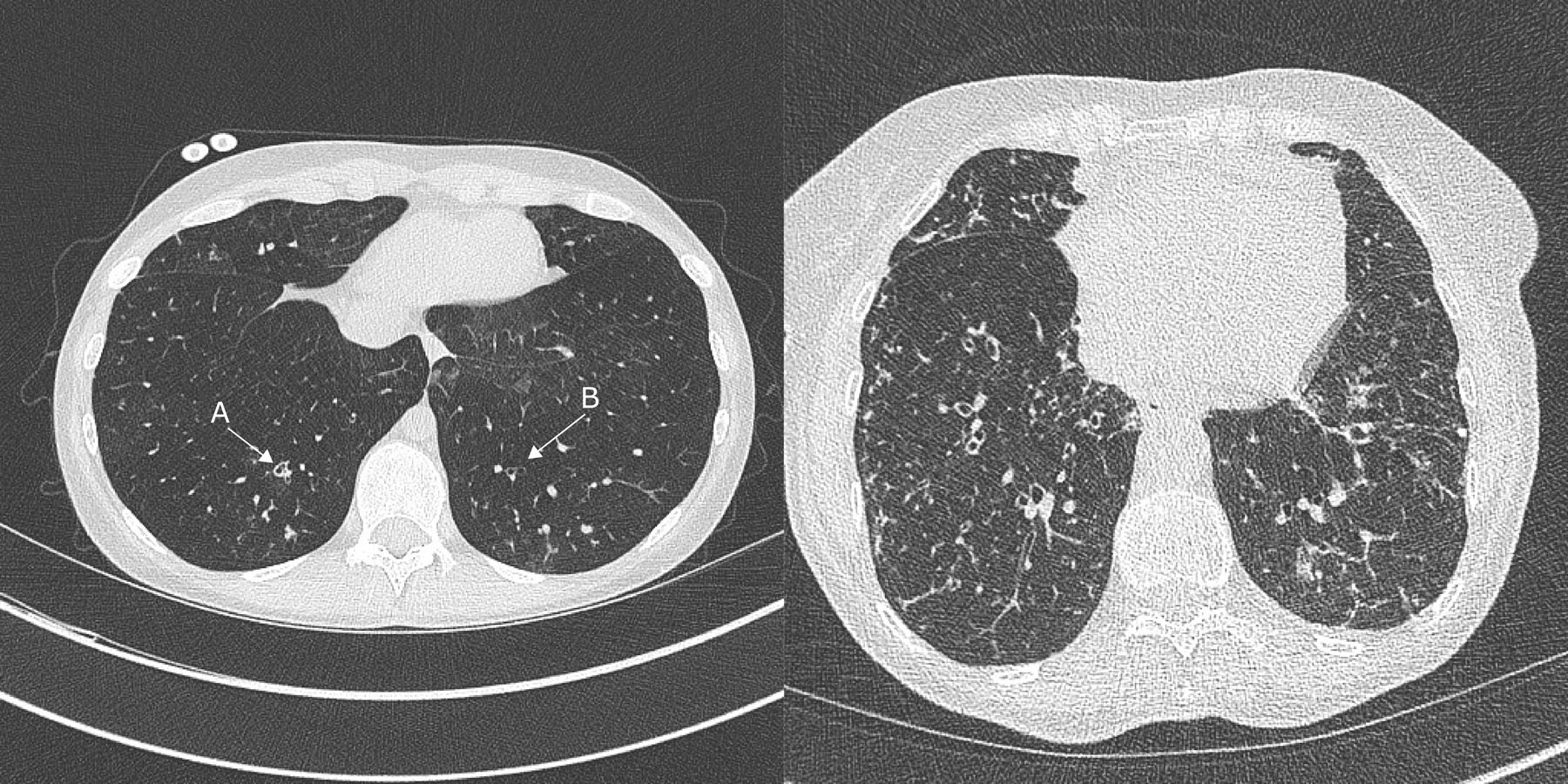

Figure 2:

Cystic bronchiectasis with mucus

Mortality appears to be high amongst patients with bronchiectasis and hematologic malignancies. In a cohort study of 75 patients, 27% died, and most deaths occurred within the first 2 years following the bronchiectasis diagnosis, particularly amongst those post-HCT. The observation that the development of bronchiectasis occurs in many patients after 3 years following the diagnosis of hematologic malignancy, and that death occurs relatively soon following the diagnosis of bronchiectasis, leads to the suggestion that bronchiectasis may be an important contributor to death in this group; prospective cohort studies are needed to confirm this, as well to assess the impact of timely bronchiectasis treatment. The main factors impacting on survival appear to be increasing age (>40 years), lower FEV1% predicted, and three or more lobes affected at the time of diagnosis. Early identification of these patients may allow for treatment before significant progression of disease.

The goal of therapy in bronchiectasis is to prevent infective exacerbations and to treat these rapidly and adequately. This will reduce inflammation and injury in the airways, thereby attenuating progression of the disease. Furthermore, treatment aims to reduce symptoms and maintain quality of life. Patients should be assessed by a pulmonologist with a special interest in bronchiectasis and pulmonary infections to receive a comprehensive assessment of host immunity, and to develop personalized therapeutic strategies that include airway clearance, early treatment of infections, prevention of frequent infective exacerbations using prophylactic oral or nebulised antibiotics, and vaccinations. The general management of bronchiectasis is discussed elsewhere101,114. Of importance in patients with hematologic malignancies is the identification of those with significant IgG deficiency, severe deficiency of switched memory B-cells, or functional antibody deficiency with poor responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination. In those with >2 exacerbations per year despite prophylactic antibiotics, administration of intravenous immunoglobulins must be considered. In the study by José et al, IgG deficiency was not associated with survival, most likely due to universal immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Monitoring of IgG and the impact of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) on the incidence of infections is required to assess efficacy of treatment. In some cases, IgG levels return to normal and IVIG may no longer be required. However, an assessment of function (e.g. vaccination responses) is necessary because function may remain impaired despite normal total IgG levels. Prophylactic antibiotics usually consist of azithromycin 250 mg daily or 500 mg three times, or, if contra-indicated, doxycycline 100 mg daily. In some patients, with drug intolerances other antibiotics are used, usually guided by the sensitivity of previously identified bacteria. For example, in patients with frequent infections with Stenotropomonas maltophilia or Acinetobacter baumanii, co-trimoxazole is considered. In cases where recurrent infections / exacerbations persist, nebulised antibiotics such as colomycin or nebulised are also used, particularly when infections are frequently due to gram negative bacteria.

Viral bronchiolitis, BOS and bronchiectasis: an important triad in hematologic malignancy

Although viral bronchiolitis, BOS and bronchiectasis are independent conditions, there are overlapping features (e.g. symptoms of cough, breathlessness, wheeze, and radiological presence of bronchial dilatation, bronchial wall thickening and air-trapping) that may make it difficult to distinguish between them in patients with hematologic malignancy, and in some cases with BOS post-allogeneic stem cell transplantation, all three may be present in the same individual. Furthermore, the presence of one may predispose to the other (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

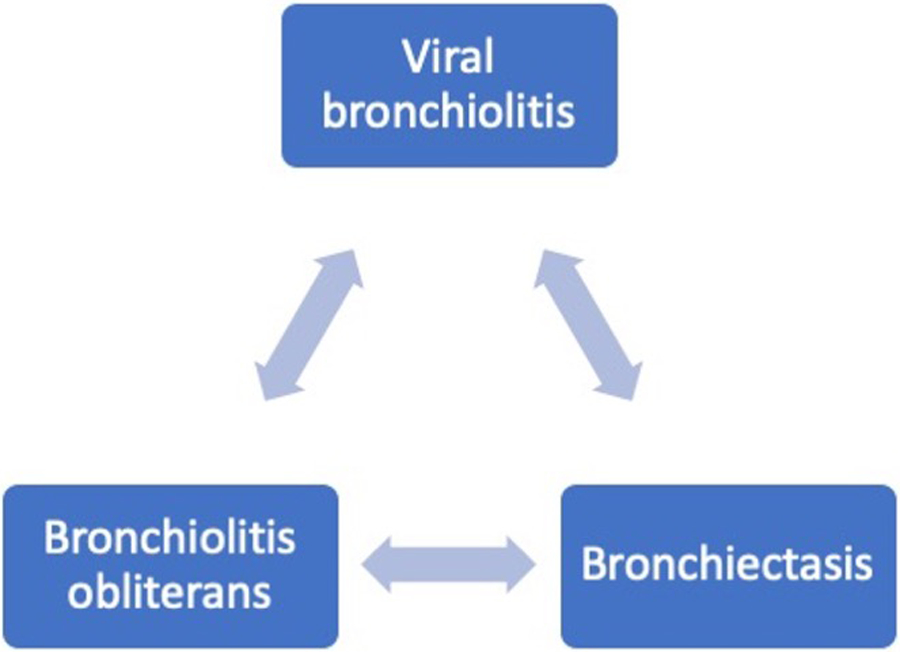

Figure 3:

Airway complications in hematologic malignancy post-allograft stem cell transplantation

Figure 4:

CT chest (left) demonstrates mild bronchiectasis in a patient with GVHD following HCT for AML - (A) Bronchial dilatation and bronchial wall thickness (B) bronchial dilatation without wall thickness. The CT Chest (right) demonstrates bronchiectasis with widespread tree-in-bud changes during influenza A infection due to small airway inflammation and mucus plugging.

Viral bronchiolitis is common post-HCT, and inflammation of the small airways can lead to bronchial wall thickening and occasionally bronchial dilatation10. These features are usually transient and resolve within weeks, but in a minority may progress to bronchiectasis, though definitive causality has not been established. Similarly, in BOS, mild bronchial dilatation is common, but only some HCT recipients subsequently develop bronchiectasis. The presence of bronchiectasis is also known to occur in other airway diseases, but the exact mechanism for this is not well established. For example, bronchial dilatation is frequently seen in patients with asthma and COPD, particularly in disease115,116.

Bronchiectasis appears to be more common amongst patients exposed to corticosteroids in the context of asthma and with IgG / IgG subclass deficiency, potentially linking frequent infections to the development of bronchiectasis117. In patients with stable bronchiectasis, respiratory viruses are frequently detected in asymptomatic individuals during the Winter season but do not appear to be a common driver of bronchiectasis exacerbations118–120. One study identified respiratory viruses in the sputum of 4% of bronchiectasis patients in their stable state and in 29% of patients during exacerbations, but in only half of these cases was a virus present without new bacteria121. However, respiratory viruses have been implicated in the pathogenesis of BOS post-HCT43, and in a small cohort of post-HCT recipients with BOS, 42% had radiological evidence of bronchiectasis104. Patients with BOS and co-existent bronchiectasis in the context of lung transplantation have worse survival, more infections and colonisation with P. aeruginosa122. A similar effect on outcome may be present in those post-HCT with bronchiectasis, but this requires study. Importantly, when considering bronchiectasis in post-HCT BOS, there should be more evidence than bronchial dilatation on radiology. Bronchiectasis in patients with existing airway disease may be misdiagnosed, since radiologic findings may reverse with therapy123, and in COPD it appears that in some cases it is the artery diameter that is reduced and not the bronchial diameter that is larger124, giving the impression of bronchiectasis. Therefore, a radiological finding of bronchial dilatation relative to vessel calibre alone is likely not sufficient for a firm diagnosis of bronchiectasis in this context.

Future directions

The global incidence of hematologic malignancy is increasing125 and with recent successes in treatment strategies, survival has also increased. As survivors live longer with the disease and are treated with novel agents that may result in secondary immunodeficiency, airway diseases and respiratory infections will increasingly be encountered. To prevent airways diseases from adding to the morbidity of survivors or leading to long-term mortality, improved understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of viral bronchiolitis, BOS, and bronchiectasis in this context is necessary. Strategies to identify patients early in their disease course may further improve the efficacy of treatment.

Expert opinion

Haematological malignancies occur with increasing frequency amongst the population, and both the malignancies and their treatments are associated with respiratory complications. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) is the most often recognised airway complication of stem cell transplantation and results in irreversible pulmonary impairment, a high symptom burden, a significant drain on healthcare resources, and often in death. The current implementation of pulmonary function screening is insufficient to diagnose BOS at an early stage, and treatments for progressive or severe BOS are lacking. Patients with BOS often survive their hematological malignancy, only to be faced with a crippling, permanent pulmonary disease.

Airway disease is also seen in the form of viral bronchiolitis and bronchiectasis. In this review we have sought to explore how BOS, viral bronchiolitis and bronchiectasis relate to one another, and particularly in how they may synergize to increase the burden of respiratory disease in this vulnerable population. Haematological malignancies and its treatments are often associated with immunosuppression, predisposing to pulmonary infections that are often of greater severity than in the general population. Viral infections are common among hematologic malignancy patients and they frequently progress to lower respiratory tract infection, resulting in inflammation of the lower airways, exudative plugging of the small airways, and airflow obstruction. Screening programs for these infections vary from institution to institution, and other than influenza and now SARS-CoV-2, proven antiviral therapies are often lacking. New antiviral therapies and strategies to induced post-viral airway inflammation may mitigate some of the burden of viral respiratory infections, but pivotal trials are lacking.

Recurrent respiratory infections also predispose to the development of bronchiectasis, which manifests with inflamed bronchial walls and mucus plugging of the small airways that predispose to further infections. This cycle of infection can ultimately result in airway damage and permanent bronchial dilatation. Finally, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome may progress to irreversible cylindrical bronchiectasis due to recurrent infections associated with immunosuppression, the presence of hypogammaglobulinaemia, or the disease pathogenesis itself. These airway diseases place an enormous burden on patients with hematological malignancies, and new treatments are needed to prevent airway infections, reduce airway inflammation, and halt the vicious cycle of recurrent airway infections.

Future studies in this space should examine ways to screen for early disease and to identify treatments that are efficacious in early and advanced disease. For example, in BOS, novel strategies such as home spirometry may address gaps in screening, and the early implementation of anti-inflammatory therapies may prevent severe pulmonary impairment. Screening for viral infections is now routine in the setting of SARS-CoV-2, and similar low-cost screening approaches may identify viral infections before they progress to severe lower respiratory infections. Preventive strategies, such as new vaccines, and new antiviral therapies will further mitigate the impact of these infections. Finally, early detection of hypogammaglobulinaemia and initiation of prophylactic antibiotics in those with recurrent bacterial lower respiratory tract infections and / or initiation of immunoglobulin replacement therapy may prevent the development or progression of bronchiectasis in this population and further study is needed.

Article highlights.

Haematological malignancies and its treatments are commonly associated with respiratory complications.

Pulmonary graft versus host disease is a highly morbid respiratory complication of stem cell transplantation

Viral bronchiolitis and bronchiectasis are increasingly recognised respiratory complications resulting in long-term pulmonary impairment and symptom burden

Viral bronchiolitis, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and bronchiectasis may occur in combination with or as a consequopence of one another.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This manuscript was in part supported by NIH grant - NIH/NIAID K23 AI117024 (to A. Sheshadri)

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Li J, Smith A, Crouch S, Oliver S, Roman E. Estimating the prevalence of hematological malignancies and precursor conditions using data from Haematological Malignancy Research Network (HMRN). Cancer Causes Control 2016; 27: 1019–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jose RJ, Faiz SA, Dickey BF, Brown JS. Non-infectious respiratory disease in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2014; 75: 691–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jose RJ, Dickey BF, Brown JS. Infectious respiratory disease in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2014; 75: 685–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chemaly RF, Shah DP, Boeckh MJ. Management of respiratory viral infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and patients with hematologic malignancies. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59 Suppl 5: S344–51.* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vakil E, Sheshadri A, Faiz SA, et al. Risk factors for mortality after respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection in adults with hematologic malignancies. Transpl Infect Dis 2018; 20: e12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chemaly RF, Hanmod SS, Rathod DB, et al. The characteristics and outcomes of parainfluenza virus infections in 200 patients with leukemia or recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2012; 119: 2738–45; quiz 2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renaud C, Xie H, Seo S, et al. Mortality rates of human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections in hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2013; 19: 1220–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogimi C, Englund JA, Bradford MC, Qin X, Boeckh M, Waghmare A. Characteristics and outcomes of coronavirus infection in children: The role of viral factors and an immunocompromised state. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2019. DOI: 10.1093/jpids/pix093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seo S, Waghmare A, Scott EM, et al. Human rhinovirus detection in the lower respiratory tract of hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: association with mortality. Haematologica 2017; 102: 1120–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu JH, Myers JL, Swensen SJ. Bronchiolar disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168: 1277–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogg JC, Macklem PT, Thurlbeck WM. Site and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med 1968. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM196806202782501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su ZQ, Guan WJ, Li SY, et al. Evaluation of the Normal Airway Morphology Using Optical Coherence Tomography. Chest 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogg JC, Paré PD, Hackett TL. The contribution of small airway obstruction to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol Rev 2017. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall WJ, Hall CB. Alterations in Pulmonary Function Following Respiratory Viral Infection. Chest 1979. DOI: 10.1378/chest.76.4.458.* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meissner HC. Viral bronchiolitis in children. N. Engl. J. Med 2016. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1413456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semple MG, Cowell A, Dove W, et al. Dual Infection of Infants by Human Metapneumovirus and Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Is Strongly Associated with Severe Bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis 2005. DOI: 10.1086/426457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigurs N, Aljassim F, Kjellman B, et al. Asthma and allergy patterns over 18 years after severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life. Thorax 2010. DOI: 10.1136/thx.2009.121582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krilov LR, Mandel FS, Barone SR, et al. Follow-up of children with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in 1986 and 1987: Potential effect of ribavirin on long term pulmonary function. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997. DOI: 10.1097/00006454-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colom AJ, Teper AM, Vollmer WM, Diette GB. Risk factors for the development of bronchiolitis obliterons in children with bronchiolitis. Thorax 2006. DOI: 10.1136/thx.2005.044909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections in Previously Healthy Working Adults. Clin Infect Dis 2001. DOI: 10.1086/322657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson DJ, Makrinioti H, Rana BM, et al. IL-33-dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190: 1373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laitinen LA, Elkin RB, Empey DW, Jacobs L, Mills J, Nadel JA. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in normal subjects during attenuated influenza virus infection. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 143: 358–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little JW, Hall WJ, Douglas RG Jr., Mudholkar GS, Speers DM, Patel K. Airway hyperreactivity and peripheral airway dysfunction in influenza A infection. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978; 118: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vakil E, Evans SE. Viral Pneumonia in Patients with Hematologic Malignancy or Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clin Chest Med 2017; 38: 97–111.* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panchabhai TS, Mukhopadhyay S, Sehgal S, Bandyopadhyay D, Erzurum SC, Mehta AC. Plugs of the Air Passages: A Clinicopathologic Review. Chest 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunican EM, Elicker BM, Gierada DS, et al. Mucus plugs in patients with asthma linked to eosinophilia and airflow obstruction. J Clin Invest 2018. DOI: 10.1172/JCI95693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avadhanula V, Rodriguez CA, Devincenzo JP, et al. Respiratory viruses augment the adhesion of bacterial pathogens to respiratory epithelium in a viral species- and cell type-dependent manner. J Virol 2006; 80: 1629–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfromm A, Porcher R, Legoff J, et al. Viral respiratory infections diagnosed by multiplex PCR after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: long-term incidence and outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2014; 20: 1238–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatzis O, Darbre S, Pasquier J, et al. Burden of severe RSV disease among immunocompromised children and adults: A 10 year retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 2018. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-018-3002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yilmaz M, Chemaly RF, Han XY, et al. Adenoviral infections in adult allogeneic hematopoietic SCT recipients: A single center experience. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013. DOI: 10.1038/bmt.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khanna N, Widmer AF, Decker M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients with hematological diseases: single-center study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46: 402–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spahr Y, Tschudin-Sutter S, Baettig V, et al. Community-Acquired Respiratory Paramyxovirus Infection After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Single-Center Experience. Open forum Infect Dis 2018; 5: ofy077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah DP, Ghantoji SS, Ariza-Heredia EJ, et al. Immunodeficiency scoring index to predict poor outcomes in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients with RSV infections. Blood 2014; 123: 3263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damlaj M, Bartoo G, Cartin-Ceba R, et al. Corticosteroid use as adjunct therapy for respiratory syncytial virus infection in adult allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 2016; 18: 216–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheshadri A, Chemaly RF, Alousi AM, et al. Pulmonary Impairment after Respiratory Viral Infections Is Associated with High Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2019; 25: 800–9.** [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milano F, Campbell AP, Guthrie KA, et al. Human rhinovirus and coronavirus detection among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients. Blood 2010. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ljungman P, de la Camara R, Perez-Bercoff L, et al. Outcome of pandemic H1N1 infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Haematologica 2011; 96: 1231–5.* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chemaly RF, Ghosh S, Bodey GP, et al. Respiratory viral infections in adults with hematologic malignancies and human stem cell transplantation recipients: a retrospective study at a major cancer center. Med 2006; 85: 278–87.** [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres HA, Aguilera EA, Mattiuzzi GN, et al. Characteristics and outcome of respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients with leukemia. Haematologica 2007; 92: 1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcolini JA, Malik S, Suki D, Whimbey E, Bodey GP. Respiratory disease due to parainfluenza virus in adult leukemia patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2003. DOI: 10.1007/s10096-002-0864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee GE, Fisher BT, Xiao R, et al. Burden of influenza-related hospitalizations and attributable mortality in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2015. DOI: 10.1093/jpids/piu066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khalifah AP, Hachem RR, Chakinala MM, et al. Respiratory viral infections are a distinct risk for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and death. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1359oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Versluys AB, Rossen JW, van Ewijk B, Schuurman R, Bierings MB, Boelens JJ. Strong association between respiratory viral infection early after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and the development of life-threatening acute and chronic alloimmune lung syndromes. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2010; 16: 782–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 415–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chemaly RF, Aitken SL, Wolfe CR, Jain R, Boeckh MJ. Aerosolized ribavirin: the most expensive drug for pneumonia. Transpl Infect Dis 2016; 18: 634–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fry AM, Goswami D, Nahar K, et al. Efficacy of oseltamivir treatment started within 5 days of symptom onset to reduce influenza illness duration and virus shedding in an urban setting in Bangladesh: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leiva-Juarez MM, Kirkpatrick CT, Gilbert BE, et al. Combined aerosolized Toll-like receptor ligands are an effective therapeutic agent against influenza pneumonia when co-administered with oseltamivir. Eur J Pharmacol 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milojkovic D, Mufti GJ. Extending the role of allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Lancet 2001; 357: 652–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Aljurf M, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a global perspective. JAMA 2010; 303: 1617–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sureda A, Bader P, Cesaro S, et al. Indications for allo- and auto-SCT for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: current practice in Europe, 2015. Bone Marrow Transpl 2015; 50: 1037–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arai S, Arora M, Wang T, et al. Increasing incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic transplantation: a report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2015; 21: 266–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee SJ, Klein JP, Barrett AJ, et al. Severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease: association with treatment-related mortality and relapse. Blood 2002; 100: 406–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pidala J, Kim J, Anasetti C, et al. The global severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease, determined by National Institutes of Health consensus criteria, is associated with overall survival and non-relapse mortality. Haematologica 2011; 96: 1678–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergeron A, Chevret S, Peffault de Latour R, et al. Noninfectious lung complications after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur Respir J 2018; 51. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.02617-2017.* [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Au BK, Au MA, Chien JW. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome epidemiology after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2011; 17: 1072–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swatek AM, Lynch TJ, Crooke AK, et al. Depletion of Airway Submucosal Glands and TP63(+)KRT5(+) Basal Cells in Obliterative Bronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: 1045–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lynch TJ, Anderson PJ, Rotti PG, et al. Submucosal Gland Myoepithelial Cells Are Reserve Stem Cells That Can Regenerate Mouse Tracheal Epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 2018; 22: 779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Z, Liao F, Scozzi D, et al. An obligatory role for club cells in preventing obliterative bronchiolitis in lung transplants. JCI Insight 2019. DOI: 10.1172/jci.insight.124732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flynn R, Du J, Veenstra RG, et al. Increased T follicular helper cells and germinal center B cells are required for cGVHD and bronchiolitis obliterans. Blood 2014; 123: 3988–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alexander KA, Flynn R, Lineburg KE, et al. CSF-1–dependant donor-derived macrophages mediate chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 4266–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holbro A, Lehmann T, Girsberger S, et al. Lung histology predicts outcome of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2013; 19: 973–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meignin V, Thivolet-Bejui F, Kambouchner M, et al. Lung histopathology of non-infectious pulmonary complications after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Histopathology 2018; 73: 832–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11: 945–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bergeron A, Godet C, Chevret S, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: phenotypes and prognosis. Bone Marrow Transpl 2013; 48: 819–24.* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Dwyer DN, Wang Y, Myers D, Moore BB, Murray S, Yanik GA. Concurrent Reductions in Spirometry Predict Mortality and Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18: 720–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abedin S, Yanik GA, Braun T, et al. Predictive value of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome stage 0p in chronic graft-versus-host disease of the lung. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2015; 21: 1127–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erard V, Chien JW, Kim HW, et al. Airflow decline after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: the role of community respiratory viruses. J Infect Dis 2006; 193: 1619–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogimi C, Xie H, Leisenring WM, et al. Initial High Viral Load Is Associated with Prolonged Shedding of Human Rhinovirus in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2018; 24: 2160–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chien JW, Martin PJ, Gooley TA, et al. Airflow obstruction after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168: 208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jamani K, He Q, Liu Y, et al. Early Post-Transplantation Spirometry Is Associated with the Development of Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Palmer J, Williams K, Inamoto Y, et al. Pulmonary symptoms measured by the national institutes of health lung score predict overall survival, nonrelapse mortality, and patient-reported outcomes in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng GS, Storer B, Chien JW, et al. Lung Function Trajectory in Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13: 1932–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vieira AG, Funke VA, Nunes EC, Frare R, Pasquini R. Bronchiolitis obliterans in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transpl 2014; 49: 812–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng GS, Campbell AP, Xie H, et al. Correlation and Agreement of Handheld Spirometry with Laboratory Spirometry in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2016; 22: 925–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turner J, He Q, Baker K, et al. Home Spirometry Telemonitoring for Early Detection of Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome in Patients with Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Transplant Cell Ther 2021; 27: 616.e1–616.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sheshadri A, Alousi A, Bashoura L, et al. Feasibility and Reliability of Home-based Spirometry Telemonitoring in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020; 17: 1329–33.* [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Galban CJ, Boes JL, Bule M, et al. Parametric response mapping as an indicator of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2014; 20: 1592–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Walkup LL, Myers K, El-Bietar J, et al. Xenon-129 MRI detects ventilation deficits in paediatric stem cell transplant patients unable to perform spirometry. Eur Respir J 2019. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01779-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Choi S, Hoffman EA, Wenzel SE, et al. Quantitative computed tomographic imaging-based clustering differentiates asthmatic subgroups with distinctive clinical phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140: 690–700.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sieren JP, Newell JD, Barr RG, et al. SPIROMICS Protocol for Multicenter Quantitative Computed Tomography to Phenotype the Lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 794–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bashoura L, Gupta S, Jain A, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids stabilize constrictive bronchiolitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008; 41: 63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bergeron A, Belle A, Chevret S, et al. Combined inhaled steroids and bronchodilatators in obstructive airway disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl 2007; 39: 547–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bergeron A, Chevret S, Chagnon K, et al. Budesonide/Formoterol for bronchiolitis obliterans after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191: 1242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hefazi M, Langer KJ, Khera N, et al. Extracorporeal Photopheresis Improves Survival in Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Patients with Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome without Significantly Impacting Measured Pulmonary Functions. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2018; 24: 1906–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miklos D, Cutler CS, Arora M, et al. Ibrutinib for chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of prior therapy. Blood 2017; 130: 2243–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Modi B, Hernandez-Henderson M, Yang D, et al. Ruxolitinib as Salvage Therapy for Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2019; 25: 265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Iacono AT, Johnson BA, Grgurich WF, et al. A randomized trial of inhaled cyclosporine in lung-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cheng GS, Edelman JD, Madtes DK, Martin PJ, Flowers ME. Outcomes of lung transplantation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2014; 20: 1169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Greer M, Berastegui C, Jaksch P, et al. Lung transplantation after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a pan-European experience. Eur Respir J 2018; 51. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01330-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tran J, Norder EE, Diaz PT, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2012; 18: 1250–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bergeron A, Chevret S, Granata A, et al. Effect of Azithromycin on Airflow Decline-Free Survival After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: The ALLOZITHRO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017; 318: 557–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Verleden SE, Vandooren J, Vos R, et al. Azithromycin decreases MMP-9 expression in the airways of lung transplant recipients. Transpl Immunol 2011; 25: 159–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vos R, Vanaudenaerde BM, Verleden SE, et al. A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin to prevent chronic rejection after lung transplantation. Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khalid M, Al Saghir A, Saleemi S, et al. Azithromycin in bronchiolitis obliterans complicating bone marrow transplantation: a preliminary study. Eur Respir J 2005; 25: 490–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lam DC, Lam B, Wong MK, et al. Effects of azithromycin in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic SCT--a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled study. Bone Marrow Transpl 2011; 46: 1551–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Norman BC, Jacobsohn DA, Williams KM, et al. Fluticasone, azithromycin and montelukast therapy in reducing corticosteroid exposure in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: a case series of eight patients. Bone Marrow Transpl 2011; 46: 1369–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Williams KM, Cheng GS, Pusic I, et al. Fluticasone, Azithromycin, and Montelukast Treatment for New-Onset Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2016; 22: 710–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kahl C, Storer BE, Sandmaier BM, et al. Relapse risk in patients with malignant diseases given allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood 2007; 110: 2744–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cheng GS, Bondeelle L, Gooley T, et al. Azithromycin use and increased cancer risk among patients with bronchiolitis obliterans after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sheshadri A, Saliba R, Patel B, et al. Azithromycin may increase hematologic relapse rates in matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplant recipients who receive anti-thymocyte globulin, but not in most other recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2021; 56: 745–8.** [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.José RJ, Brown JS. Bronchiectasis. Br J Hosp Med 2014; 75. DOI: 10.12968/hmed.2014.75.Sup10.C146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cole PJ. Inflammation: a two-edged sword--the model of bronchiectasis. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl 1986; 147: 6–15.* [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Morehead RS. Bronchiectasis in bone marrow transplantation. Thorax 1997; 52: 392–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gunn MLD, Godwin JD, Kanne JP, Flowers ME, Chien JW. High-resolution CT Findings of Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. J Thorac Imaging 2008; 23: 244–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chernoff A, Rymuza J, Lippmann ML. Endobronchial lymphocytic infiltration. Unusual manifestation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Med 1984; 77: 755–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Quint J, Millett E, Hurst J, Smeeth L, Brown J. Time Trends in Incidence and Prevalence of Bronchiectasis in the UK. Thorax 2012; 67: A138–A138. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Loebinger MR, Wells AU, Hansell DM, et al. Mortality in bronchiectasis: a long-term study assessing the factors influencing survival. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 843–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Onen ZP, Gulbay BE, Sen E, et al. Analysis of the factors related to mortality in patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Med 2007; 101: 1390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 1684–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.José RJ, Hall J, Brown JS. De novo bronchiectasis in haematological malignancies: patient characteristics, risk factors and survival. ERJ Open Res 2019; 5: 00166–2019.** [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen LW, McShane PJ, Karkowsky W, et al. De Novo Development of Bronchiectasis in Patients With Hematologic Malignancy. Chest 2017; 152: 683–5.** [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Davies G, Wells AU, Doffman S, Watanabe S, Wilson R. The effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on pulmonary function in patients with bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2006; 28: 974–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wilson CB, Jones PW, O’Leary CJ, Hansell DM, Cole PJ, Wilson R. Effect of sputum bacteriology on the quality of life of patients with bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 1997; 10: 1754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.E P, PC G, MJ M, et al. European Respiratory Society Guidelines for the Management of Adult Bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 2017; 50. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.00629-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Takemura M, Niimi A, Minakuchi M, et al. Bronchial dilatation in asthma: relation to clinical and sputum indices. Chest 2004; 125: 1352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hurst JR, Elborn JS, Soyza A De. COPD–bronchiectasis overlap syndrome. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 310–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Luján M, Gallardo X, Amengual MJ, Bosque M, Mirapeix RM, Domingo C. Prevalence of Bronchiectasis in Asthma according to Oral Steroid Requirement: Influence of Immunoglobulin Levels. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mitchell AB, Mourad B, Buddle L, Peters MJ, Oliver BGG, Morgan LC. Viruses in bronchiectasis: a pilot study to explore the presence of community acquired respiratory viruses in stable patients and during acute exacerbations. BMC Pulm Med 2018; 18: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Thng KX, Mac Aogáin M, Ali NABM, et al. Viral prevalence in stable bronchiectasis: analysis of the Cohort of Asian and Matched European Bronchiectasis (CAMEB). In: Respiratory infections European Respiratory Society, 2019: PA2875. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jose RJ, Hassan S, Butler M, Watson D, Kuitert L. P167 Screening for viral upper respiratory tract infection in pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2011; 66: A135–A135. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chen C-L, Huang Y, Yuan J-J, et al. The Roles of Bacteria and Viruses in Bronchiectasis Exacerbation: A Prospective Study. Arch Bronconeumol 2020; published online April 8. DOI: 10.1016/J.ARBRES.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Van Herck A, Sacreas A, Heigl T, et al. Bronchiectasis as prognostic factor in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. In: Transplantation European Respiratory Society, 2018: OA3334. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cukier A, Stelmach R, Kavakama JI, Terra Filho M, Vargas F. Persistent asthma in adults: comparison of high resolution computed tomography of the lungs after one year of follow-up. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 2001; 56: 63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.AA D, TP Y, DJ M, et al. Quantitative CT Measures of Bronchiectasis in Smokers. Chest 2017; 151. DOI: 10.1016/J.CHEST.2016.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fitzmaurice C, Akinyemiju TF, Al Lami FH, et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2016. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4: 1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]