Abstract

Research on sex differences in the association of psychopathy with fluid intelligence is limited, and it remains unknown if fluid intelligence plays a meaningful role in explaining the psychopathy-aggression link for men and women. The present study aimed to test for sex differences in the relation between the 4-facet model of psychopathy and intelligence, and to assess whether fluid intelligence moderates the link between psychopathy and aggression. In a community sample of men (n=356) and women (n=196), we assessed psychopathy using the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV), fluid intelligence using the Raven’s Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., 2000), and types of aggression using the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ). Hierarchical regressions showed the psychopathy lifestyle facet was negatively associated with intelligence and there were no sex differences. Our analyses for types of aggression revealed sex differences and similarities. For both men and women, total AQ scores were predicted by higher antisocial facet scores. Lower intelligence moderated the link between higher antisocial facet scores and aggression in men, but not for women. Physical aggression in women was associated with higher interpersonal, affective, and antisocial facet scores, whereas for men, it was only associated with higher antisocial facet scores. Verbal and indirect aggression were associated with higher intelligence in both men and women. For men only, higher antisocial facet scores were associated with verbal and indirect aggression. Higher intelligence moderated the link between the lifestyle facet and indirect aggression for women, whereas for men it moderated the link between the affective facet and indirect aggression. This study further highlights sex differences in mechanisms of psychopathy-related aggression, which need to be considered in the development of violence interventions and risk assessment.

Keywords: violence, alcohol and drugs, community violence, mental health and violence

Early portrayals of psychopaths described these individuals as having “good” intelligence (Cleckley, 1988 p.338). In 1939, Henderson went so far as to describe one psychopathic state, the creative psychopath, as “near genius” (1939 p.112). Yet, recent evidence suggests this may not be the case, and that there is a small association between psychopathy and intelligence (Hare & Neumann, 2008). However, there is evidence to suggest that the association may be stronger depending on what features of psychopathy are being assessed. Traditionally, psychopathy was best understood using two factors (Guy & Douglas, 2006). Factor 1 includes interpersonal-affective traits, while factor 2 includes impulsive-antisocial traits. More recently, researchers have found that a 4-facet structure provides a superior model fit than the 2-factor model (Neumann, Hare, & Newman, 2007; Vitacco, Neumann, & Wodushek, 2008), and that the 4facet model has been critical to understanding sex differences in the association of psychopathy with aggressive and violent behavior (Thomson, Bozgunov, Psederska, & Vassileva, 2019; Thomson, Kiehl, & Bjork, 2018). The 4-facet model divides each of the factors into two facets. Thus, factor 1 includes the interpersonal (i.e., grandiosity, superficial charm, manipulative) and affective facets (i.e., lack of remorse, shallow affect, callous lack of empathy), while factor 2 includes the lifestyle (i.e., boredom susceptibility, impulsivity, lack of realistic long-term goals) and antisocial facets (i.e., poor behavioral controls, juvenile and adult delinquency). Research exploring the relation between the 4-facet model of psychopathy and intelligence is lacking, and studies examining sex differences are limited. In addition, while there has been a periodic flurry of research testing the psychopathy-intelligence relation, there remains little understanding of the importance of this association. Therefore, the aim of the present study is twofold: to test the association between the 4-facet model of psychopathy and intelligence in men and women, and to assess if intelligence has a moderating role in the link between psychopathy and aggression.

Psychopathy and Intelligence

Most research on psychopathy and intelligence has come from male offender samples or undergraduate students, which has provided mixed results. Variability of findings are often attributable to a lack of standardized measures of intelligence and psychopathy. Using total scores of psychopathy, some research has found no association with intelligence using the Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Short Form (PPI-SF; Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996; Watts et al., 2016) and the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R; Hare et al., 1990; Johansson & Kerr, 2005), while others have found a negative association using the PCL-R (Beggs & Grace, 2008) and the Psychopathy Checklist-Screening Version (PCL:SV; DeLisi et al. 2010; Hart et al. 1995). Further, Watts et al. (2016) did not find any differences between men and women in the association between intelligence and self-report psychopathy (PPI) in a student sample. Studies using the factor and facet structure of clinical assessments of psychopathy have yielded more consistent results, such that factor 2, the lifestyle facet, and the antisocial facet have been consistently found to be related to lower intelligence (Bozgunov et al., 2014; Heinzen et al, 2011; Neumann & Hare, 2008). Using a mixed sex Bulgarian community sample (N=332), Bozgunov et al. (2014) found that fluid intelligence, broadly defined as the ability to deploy analytical reasoning and problem-solving when presented with novel information (Cattell, 1971), as measured by Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM; Raven et al. 2000), was negatively related to both psychopathy factors and the total psychopathy score of the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV; Hart et al., 1995). After controlling for the effect of each factor, the only correlation to remain significant was between factor 2 and intelligence, suggesting that intelligence is uniquely related to factor 2 (Bozgunov et al., 2014). However, the 2-factor model of psychopathy may yield mixed findings with intelligence because of the different associations among the interpersonal and affective facets, which are embedded within factor 1. For example, in three separate samples, including men and women psychiatric inpatients, male jail inmates, and male Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity acquittees, the interpersonal facet was positively associated with intelligence, while the affective facet was negatively associated with intelligence (Thomson, Galusha, et al., 2019; Vitacco et al., 2005, 2008). Thus, the 4-facet model may be more suited for understanding specific associations between psychopathy and intelligence.

Mixed findings on the psychopathy-intelligence link have also been documented within female criminal offenders, across correctional and forensic samples. In women, Spironelli et al., (2014) found that lower intelligence in Italian inpatients, indexed with the RPM, was related to higher factor 1, factor 2, and each of the four facets of psychopathy using the PCL-R. Because of the small sample size (N=56) this study was limited to correlations and was unable to control for the other facets, therefore, unique effects were not assessed. In contrast, a study involving highrisk female offenders in the UK (Mckeown & Thomson, 2019) and a study including a mixed sample of hospitalized and incarcerated violent female offenders from Finland (Weizmann-Henelius, Viemerö, & Eronen, 2004) both found intelligence was unrelated to the PCL-R total score, factors, and facets. Results in women have also been found to differ based on ethnicity. For example, higher total psychopathy scores were linked to lower intelligence in a sample of nonpsychotic female offenders, but this was only significant for African Americans but not Caucasians (Vitale et al., 2002). Although sex differences in the relation between psychopathy and intelligence may exist, it is difficult to compare and interpret these potential differences across studies due to the diversity in sample types.

Psychopathy and Aggression

Psychopathy and aggression are strongly linked (Robertson & Knight, 2014; Thomson et al,, 2020), and recent research has begun to attempt to explain the mechanisms of psychopathy-related aggression (Garofalo et al., 2020). This research has largely focused on incarcerated individuals (Thomson, 2017), and few studies have examined differences between men and women (Thomson, Bozgunov, Psederska, et al., 2019). Understanding the relationship between psychopathy and aggression in community samples offers several benefits. Firstly, studying at the community-level provides the opportunity to explore what features of psychopathy are catalytic for aggressive behavior when individuals are living more freely in society. This is important as prior research suggests that the context by which aggressive behavior occurs plays an integral role in understanding specific risk factors, particularly for psychopathy (Thomson, 2020; Thomson et al., 2018). That is, psychopathy may be differently related to aggression for people living in the community than it is for prisoners or inpatients who are supervised 24/7. In addition to where aggression is occurring contextually, it is important to consider the type of aggression, such as overt or covert forms of aggression.

Overt forms of aggression can be characterized as physical (e.g., causing physical harm to another person) or verbal (e.g., intimidation, verbal abuse, threats, etc.), while covert forms of aggression are often characterized as indirect and relational (e.g., character defamation, gossiping behind someone’s back). There are well-established sex differences in forms of aggression; men display more overt aggression, whereas women engage in similar or higher levels of covert aggression (Österman & Björkqvist, 2018). Research on psychopathy has found men and women share similarities in physical aggression being related to antisocial psychopathic traits, while affective psychopathic traits are related to physical aggression in women (Thomson, Bozgunov, Psederska, et al., 2019). However, less is known about the relation between psychopathy facets and the other forms of aggression (i.e., verbal and indirect) in men and women. Existing research shows verbal aggression is related to higher interpersonal facet scores for both men and women, while indirect aggression is related to antisocial facet scores for only men (Thomson, Bozgunov, Psederska, et al., 2019). Emerging evidence has suggested that cognitive function (i.e., emotion regulation capabilities) may play a crucial role linking psychopathy to specific forms of aggression. For example, both Garofalo et al. (2020) and Thomson, Kiehl, and Bjork (2019) found poor emotion regulation (self-report and biological indices, respectively) explained or strengthened the link between psychopathic traits and physical aggression. However, this was not the case for verbal aggression (Garofalo et al., 2020). Although limited research has explored the link between psychopathy and covert forms of aggression, it could be expected that more intricate (e.g., planned) forms of aggression require higher levels of cognitive functioning (Thomson & Centifanti, 2018).

Psychopathy, Intelligence, and Aggression

Based on research testing the Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory of Intelligence, fluid intelligence, as measured by the RPM, is contingent on bilateral frontal and parietal brain region functioning (Duncan et al., 2000; Kroger et al., 2002), in particular the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC), inferior and superior parietal lobule, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and regions within the temporal and occipital lobes (Vakhtin et al., 2014). Indeed, several of these brain regions have been implicated in those with psychopathic traits, such as the dorsolateral PFC (Korponay et al., 2017) and the ACC (Abe et al., 2018; Blair, 2007). These brain regions, as well as fluid intelligence, have also been linked to aggressive and violent behavior (Boes et al., 2008; Choy et al., 2018; Jacob et al., 2018). The mechanisms of this link have been further examined within research in clinical populations. In support of the idea that intelligence may moderate the association between psychopathy and aggression, a recent study including male and female adolescents from a closed treatment institute found intelligence moderated the association between the impulsive irresponsibility facet of the Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory (YPI; Andershed et al., 2002) and aggression (Jambroes et al., 2018). This facet most closely represents the lifestyle facet in adults. Although the authors did not test for sex differences, these results are the first to highlight the importance of considering the role of intelligence in the link between specific psychopathic traits and aggressive behavior. In this case, the link between the lifestyle facet and aggression may be contingent on low intelligence.

Although the discussion of intelligence and aggression typically focuses on low intelligence, it is possible that higher intelligence when coupled with risky personality traits may greatly increase the risk of aggressive behavior. Indeed, Cleckley (1988) stated “psychometric tests also very frequently show him [the psychopath] of superior intelligence” (p. 339), and this was particular to the superficially charming features of psychopathy. Research has since supported the link between the interpersonal facet and higher intelligence (Ben-Yaacov & Glicksohn, 2018; Jambroes et al., 2018; Mckeown & Thomson, 2019; Nijman et al., 2009; Salekin et al., 2004; Vitacco et al., 2005). Therefore, it may be that higher levels of intelligence promote more calculated forms of aggression (i.e., indirect), and thus, increases the general versatility of psychopathy-related aggression.

Current Study

To further understand the link between psychopathy and intelligence in men and women, our first aim is to test which facets of the PCL:SV are associated with fluid intelligence using the RPM, while testing for sex differences. Based on prior research, we expected the affective, lifestyle, and antisocial facets to be negatively related to fluid intelligence, and the interpersonal facet to be positively related to intelligence (Neumann & Hare, 2008; Thomson, Galusha, et al., 2019). We did not expect to find any sex differences. Our second aim is to test if intelligence moderates the association between psychopathy facets and types of aggression (total scores, physical aggression, verbal aggression, and indirect aggression). Although this is the first study to test the moderating role of fluid intelligence on the link between the four-facet model of the PCL:SV and types of aggression, we have based our hypothesis on theoretical positions. Because aggression (cumulative forms), verbal aggression and physical aggression (i.e., violence) are related to low intelligence (Duran-Bonavila et al., 2017; Lösel & Murray, 2016), as well as higher affective, lifestyle, and antisocial facets in men and women (Neumann & Hare, 2008; Thomson, Galusha, et al., 2019), we anticipated that low intelligence would moderate the association between the affective, lifestyle, and antisocial facets with total aggression, verbal aggression, and physical aggression. No sex differences were expected. Because recent research in youth has found higher intelligence to moderate the link between affective traits and instrumental aggression (Jambroes et al., 2018), we expected to find a similar association with indirect aggression because the two forms of aggression require planning (Thomson, Bozgunov, Psederska, et al., 2019). We did not have any sex-specific expectations due to the lack of research in this area.

Method

Participants and Data Collection

Data were collected as part of a larger ongoing study investigating impulsivity among substance dependent individuals in a community sample in Bulgaria. The data was collected in two sessions on two separate days, which included a combination of clinical interviews, self-report surveys, and neurocognitive tasks. Testing was conducted by an experienced team of psychologists at the Bulgarian Addictions Institute. All participants provided informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Virginia Commonwealth University and Medical University of Sofia on behalf of the Bulgarian Addictions Institute.

The sample consisted of healthy controls with no history of substance abuse or dependence and individuals who had a past history of opiate or stimulant dependence as defined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, text rev.; DSM-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2000) criteria. Thus, analyses covaried for the presence of substance use disorder (SUD). All participants met the following inclusion criteria: a minimum of an eighth grade education, being able to read and write in Bulgarian, no history of head injury, and having an estimated IQ higher than 75, which is a standard cutoff score to measure intellectual functioning in individuals without cognitive disabilities and is commonly used in IQ-related research (Wilson et al., 2014). The sample included 314 male and 174 female Bulgarian adults between the ages of 18 and 45 with a mean age of 27.68 (SD=6.33), 87% of whom had achieved a high school diploma; 51% percent met diagnostic criteria for substance dependence and 7.3% met the diagnostic cut-off for psychopathy (PCL:SV >18).

Psychopathy

The Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV; Hart et al., 1995) is a 12-item semi-structured interview based on the PCL-R, which has been adapted and validated cross-culturally (Douglas et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2014). Items are scored on a three-point scale (0 = absent; 1 = somewhat present; 2 = definitely present) and summed to provide total scores ranging from 0 to 24 points. Psychometric analysis of the Bulgarian version of the PCL:SV with a subset of the current Bulgarian sample was performed by Wilson et al. (2014), which demonstrated good fit and adequate internal consistency of the 4-facet model of psychopathy. Interrater reliability was good for Affective (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.95), Interpersonal (ICC = 0.92), Lifestyle (ICC = 0.96) and Antisocial facets (ICC = 0.98). The PCL:SV was conducted by trained research assistants and clinicians at the Bulgarian Addictions Institute. The research team was trained on the PCL:SV by J.V., who created the authorized version of the Bulgarian PCL-R with its publisher Multi-Health Systems. Additional training and supervision were provided throughout the study by G.V., who had completed formal training workshops led by Dr. Robert Hare. The two trainers (J.V. and G.V.) have substantial experience with the use of the PCL-R and PCL:SV and with the construct of psychopathy.

Intelligence

To measure fluid intelligence, the Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., 2000) was administered. The RPM is among the most widely used IQ-tests in the clinical practice, which provide a nonverbal, culturally-free assessment of the general ability to solve novel problems and adapt to new situations. The instrument consists of 60 multiple choice visual items, divided into 5 sets of 12 items each. The test items within each set are listed in order of increasing difficulty. All of the items presented a pattern of shapes with a missing piece. The participant is asked to identify the missing element which completes the pattern of shapes by choosing one out of six or eight options for each item. In the current study we used the paperpencil version of the RPM.

Aggression

The Aggression Questionnaire (AQ; Buss & Warren, 2000) measures the tendency to behave aggressively across multiple forms and risk factors for aggression (i.e., physical aggression, verbal aggression, indirect aggression, anger, and hostility). The anger and hostility subscales are risk factors for being aggressive and not direct measures of aggression. Because the present study focuses on acts of aggressive behavior, we only analyzed total aggression, physical aggression (e.g., “If somebody hits me, I hit back”), verbal aggression (“When people annoy me, I may tell them what I think of them”), and indirect aggression (e.g., “…spread gossip about people I don’t like”). Consistent with prior research (see Gresham et al., 2016), the reliability of the scales in the present sample were adequate to good (α = .68-.91).

Substance Dependence

Substance use disorders (SUD) were assessed using the Substance Abuse Module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I; First et al., 1996). Raters assessed the presence of DSM-IV symptoms of alcohol, cannabis, opiate, and stimulant abuse and dependence using a three-point scale (0 = not present, 1 = subthreshold, 2 = present). A diagnosis of SUD was made if the participant displayed three or more of the substance dependence criteria within 12-months.

Data Analytic Plan

First, we conducted bivariate correlations among the main study variables for men and women. Next, we conducted hierarchical linear regressions to assess what facets of psychopathy were related to intelligence, and if there were sex differences in these associations. Step 1 included all predictors (age, sex, SUD, and psychopathy facets), and Step 2 included the interaction terms between the facets and sex. To test whether intelligence moderated the association between psychopathy facets and subtypes of aggression for men and women, we conducted a series of hierarchical linear regressions for predicting total aggression, physical aggression, indirect aggression, and verbal aggression. Separate regressions were conducted for men and women, which followed the same order: Step 1 included age, SUD, and intelligence; Step 2 included the psychopathy facets; Step 3 included the interaction terms between the psychopathy facets and intelligence. Significant interactions were probed using simple slopes analysis (Aiken & West, 1991). A power analysis indicated the sample size for sex-specific analyses was adequate to detect a medium effect (f2=.15) with a power of 0.95 and an alpha of 0.05.

Results

Psychopathy and Intelligence

Bivariate correlations among the main study variables for women (Table 1) and men (Table 1) showed all facets of psychopathy were positively correlated with total scores of aggression, physical aggression, indirect aggression, and verbal aggression. In women, intelligence was not associated with any psychopathy facets, but was positively related to indirect and verbal aggression. In men, intelligence was negatively related to all psychopathy facets, and unrelated to all forms of aggression.

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptives for main study variables: Women (n=196)

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Interpersonal | - | ||||||||

| 2. Affective | .47*** | - | |||||||

| 3. Lifestyle | .40*** | .54*** | - | ||||||

| 4. Antisocial | .52*** | .58*** | .66*** | - | |||||

| 5. Intelligence | .01 | −.04 | −.11 | −.09 | - | ||||

| 6. Aggression | .31*** | .34*** | .38*** | .45*** | .04 | - | |||

| 7. Physical aggression | .40*** | .44*** | .35*** | .47*** | .12 | .66*** | - | ||

| 8. Indirect aggression | .24** | .26*** | .26*** | .25*** | .21** | .67*** | .57*** | - | |

| 9. Verbal aggression | .20** | .16* | .24** | .26*** | .18** | .63*** | .37*** | .41*** | - |

| M | 0.73 | 0.73 | 1.49 | 1.44 | 110.49 | 39.34 | 14.09 | 13.81 | 8.18 |

| SD | .94 | 1.17 | 1.61 | 1.64 | 11.34 | 10.45 | 5.29 | 3.79 | 2.81 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

To test for sex differences in the association between psychopathy and intelligence, while controlling for the non-target psychopathy facets, a hierarchical linear regression was conducted (see Table 3). Step 1 included sex, age, substance use disorder (SUD), and the four facets of the PCL:SV (F (7, 545) = 5.70, p < .001). The lifestyle facet (p=.013) and age (p=.016) were significant. Step 2 added the interaction term between the PCL:SV facets and sex (F (11, 541) = 3.85, p < .001), however, no interactions were significant. Thus, higher PCL:SV lifestyle scores were associated with lower intelligence, and there were no sex differences in the relation between psychopathy and intelligence.

Table 3.

PCL:SV facets predicting intelligence, moderated by sex

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Step 1 | .07*** | |||

| Sex | −1.49 | 1.22 | −0.06 | |

| Age | −1.44 | 0.60 | −0.10* | |

| SUD | 0.48 | 1.54 | 0.02 | |

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.01 | |

| PCL:SV Affective | −0.13 | 0.81 | −0.01 | |

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | −2.10 | 0.84 | −0.16* | |

| PCL:SV Antisocial | −0.92 | 0.96 | −0.07 | |

| Step 2 | .00 | |||

| Sex | −2.46 | 1.39 | −0.09 | |

| Age | −1.42 | 0.60 | −0.10* | |

| SUD | 0.38 | 1.56 | 0.02 | |

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 1.60 | 1.60 | 0.12 | |

| PCL:SV Affective | 0.24 | 1.75 | 0.02 | |

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | −1.45 | 1.47 | −0.11 | |

| PCL:SV Antisocial | −1.39 | 1.76 | −0.11 | |

| Interpersonal X Sex | −1.88 | 1.79 | −0.12 | |

| Affective X Sex | −0.32 | 1.98 | −0.02 | |

| Lifestyle X Sex | −0.96 | 1.77 | −0.06 | |

| Antisocial X Sex | 0.62 | 1.96 | 0.04 | |

Note. SUD = Substance Use Disorder; Sex = Men (1) Women (0)

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

The Moderating Role of Intelligence Between Psychopathy and Total Aggression Scores

Results of the hierarchical linear regression predicting total scores on the Aggression Questionnaire for men and women are displayed in Table 4. For women, step 1 was significant (F (3, 193) = 5.66, p =.001) and SUD (p<.001) was positively associated with aggression. Step 2 was significant (F (7, 189) = 9.45, p <.001) and the antisocial facet was positively associated with aggression (p<.001). Step 3 included the interaction terms between the PCL:SV facets and intelligence (F (11, 185) = 7.12, p < .001) but no significant interactions emerged.

Table 4.

Psychopathy and Intelligence as Predictors of Total Aggression Questionnaire Scores

| Aggression: Women | Aggression: Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Step 1 | .08** | .15*** | ||||||

| Age | −1.17 | 0.77 | −0.11 | −1.46 | 0.77 | −0.10 | ||

| SUD | 5.54 | 1.51 | 0.26*** | 10.18 | 1.32 | 0.39*** | ||

| Intelligence | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.03 | −0.25 | 0.65 | −0.02 | ||

| Step 2 | .18*** | .12*** | ||||||

| Age | −1.17 | 0.71 | −0.11 | −1.45 | 0.72 | −0.10* | ||

| SUD | −4.02 | 2.02 | −0.19* | 1.43 | 1.73 | 0.06 | ||

| Intelligence | 0.56 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.04 | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 1.20 | 1.21 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.07 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | 1.13 | 1.31 | 0.07 | −0.17 | 0.83 | −0.01 | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 2.14 | 1.11 | 0.17 | 1.26 | 0.93 | 0.10 | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 5.17 | 1.46 | 0.39*** | 4.73 | 1.00 | 0.38*** | ||

| Step 2 | 04* | .02 | ||||||

| Age | −1.50 | 0.71 | −0.14* | −1.50 | 0.72 | −0.10* | ||

| SUD | −3.09 | 2.05 | −0.14 | 1.51 | 1.73 | 0.06 | ||

| Intelligence | 0.61 | 1.02 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.03 | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 2.40 | 1.32 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 0.74 | 0.08 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | 0.54 | 1.42 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.00 | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 2.14 | 1.12 | 0.17 | 1.29 | 0.93 | 0.10 | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 4.39 | 1.48 | 0.33** | 4.48 | 1.01 | 0.36*** | ||

| Interpersonal*Intelligence | −2.36 | 1.32 | −0.16 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.07 | ||

| Affective*Intelligence | 1.75 | 1.51 | 0.12 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.04 | ||

| Lifestyle*Intelligence | 2.42 | 1.24 | 0.18 | 1.81 | 0.93 | 0.14 | ||

| Antisocial*Intelligence | −0.86 | 1.49 | −0.07 | −1.91 | 0.94 | −0.16* | ||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

For men, step 1 was significant (F (3, 353) = 20.65, p < .001), and SUD was positively associated with aggression (p<.001). Step 2 was significant (F (7, 349) = 17.95, p < .001), and the antisocial facet was positively associated with aggression (p<.001). Step 3 was significant (F (1, 345) = 12.34, p < .001), revealing significant interaction between the antisocial facet and intelligence (p =.042). Simple slopes analysis (see Figure 1) showed high antisocial traits predicted aggression for men with low intelligence (p<.001) but not for men with high intelligence (p=.080).

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of intelligence on the association between antisocial psychopathic traits and aggression in men.

Note. Low and high values represents +1.0 and −1.0 SD from the mean.

Physical Aggression

Results of the hierarchical linear regression predicting physical aggression for men and women are displayed in Table 5. For women, step 1 was significant (F (3, 193) = 6.76, p <.001), and SUD (p<.001) was positively associated with physical aggression. Step 2 was significant (F (7, 189) = 12.17, p < .001), and the interpersonal (p=.033), affective (p=.013), and antisocial facets (p=.001) were positively associated with physical aggression. No significant interactions emerged in step 3 (F (11, 185) = 8.09, p < .001).

Table 5.

Psychopathy and Intelligence as Predictors of Physical Aggression

| Physical Aggression: Women | Physical Aggression: Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Step 1 | .10*** | .17*** | ||||||

| Age | −0.25 | 0.38 | −0.05 | −1.16 | 0.38 | −0.15** | ||

| SUD | 3.10 | 0.75 | 0.29*** | 5.36 | 0.65 | 0.41*** | ||

| Intelligence | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.01 | ||

| Step 2 | .22*** | .20*** | ||||||

| Age | −0.28 | 0.34 | −0.05 | −1.18 | 0.33 | −0.15*** | ||

| SUD | −1.61 | 0.98 | −0.15 | −0.30 | 0.80 | −0.02 | ||

| Intelligence | 0.77 | 0.38 | 0.13* | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.07 | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 1.26 | 0.59 | 0.16* | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.09 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | 1.60 | 0.64 | 0.20* | 0.68 | 0.38 | 0.11 | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.02 | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 2.39 | 0.70 | 0.36** | 3.00 | 0.46 | 0.49*** | ||

| Step 2 | 01 | .01 | ||||||

| Age | −0.36 | 0.35 | −0.07 | −1.21 | 0.33 | −0.16*** | ||

| SUD | −1.51 | 1.01 | −0.14 | −0.31 | 0.80 | −0.02 | ||

| Intelligence | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.06 | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 1.74 | 0.65 | 0.22** | 0.61 | 0.34 | 0.09 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | 1.49 | 0.70 | 0.19* | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.13* | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 0.21 | 0.55 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.02*** | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 2.19 | 0.73 | 0.33** | 2.91 | 0.47 | 0.47 | ||

| Interpersonal*Intelligence | −1.18 | 0.65 | −0.16 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.04 | ||

| Affective*Intelligence | 0.05 | 0.74 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.07 | ||

| Lifestyle*Intelligence | 0.41 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.08 | ||

| Antisocial*Intelligence | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.02 | −0.62 | 0.43 | −0.10 | ||

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

For men, step 1 was significant (F (7, 353) = 23.98, p < .001), and age (p < .001) and SUD (p < .001) were associated with physical aggression. Step 2 was significant (F (7, 349) = 29.02, p < .001), and only the antisocial facet was significant (p < .001). Although Step 3 was significant (F (11, 345) = 18.99, p < .001) no interactions were significant predictors of physical aggression.

Indirect Aggression

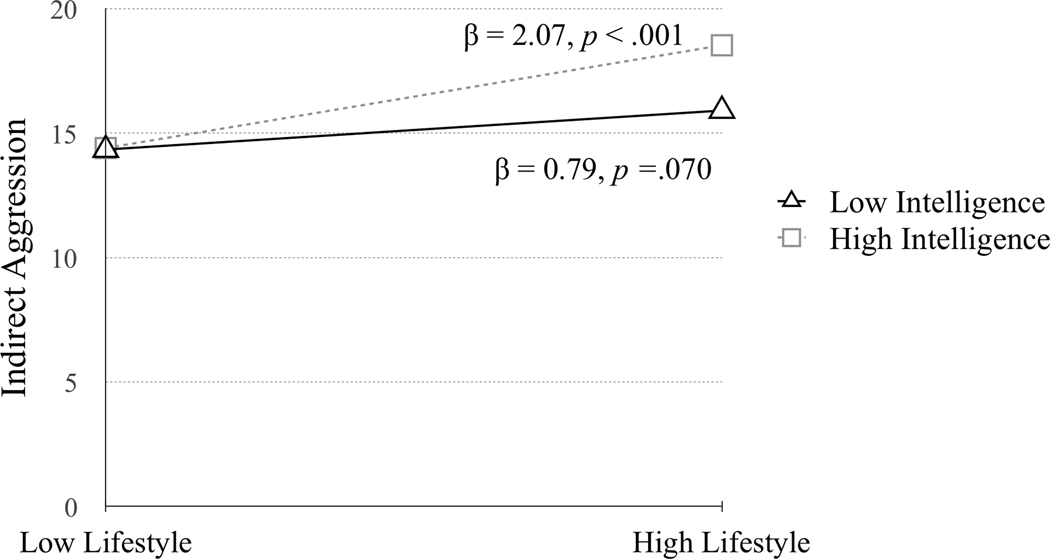

Results of the hierarchical linear regression predicting indirect aggression for men and women are displayed in Table 6. For women, step 1 was significant (F (3, 189) = 5.14, p =.002), and SUD (p=.024) and intelligence (p=.004) were positively associated with indirect aggression. Step 2 was significant (F (7, 185) = 5.57, p < .001) but no significant associations emerged. Step 3 was significant F (11, 181) = 5.42, p < .001) and the interaction between the lifestyle facet and intelligence was significant (p=.007). Figure 2 shows the simple slopes analysis which found higher antisocial facet scores and higher intelligence predicted indirect aggression for women (p <.001).

Table 6.

Psychopathy and Intelligence as Predictors of Indirect Aggression

| Indirect Aggression: Women | Indirect Aggression: Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Step 1 | .08** | .13*** | ||||||

| Age | −0.34 | 0.28 | −0.08 | −0.68 | 0.28 | −0.12* | ||

| SUD | 1.26 | 0.55 | 0.16* | 3.45 | 0.48 | 0.37*** | ||

| Intelligence | 0.91 | 0.32 | 0.21** | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.08 | ||

| Step 2 | .10*** | .12*** | ||||||

| Age | −0.43 | 0.28 | −0.11 | −0.69 | 0.26 | −0.13** | ||

| SUD | −1.01 | 0.80 | −0.13 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 0.03 | ||

| Intelligence | 0.85 | 0.30 | 0.19** | 0.63 | 0.23 | 0.13** | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 0.80 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.06 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.11 | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 0.84 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.07 | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 1.41 | 0.37 | 0.31*** | ||

| Step 2 | 07** | .04** | ||||||

| Age | −0.53 | 0.27 | −0.13 | −0.75 | 0.26 | −0.14** | ||

| SUD | −0.42 | 0.80 | −0.05 | 0.22 | 0.63 | 0.02 | ||

| Intelligence | 1.34 | 0.40 | 0.30** | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.10* | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 1.09 | 0.51 | 0.19* | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.07 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.13 | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 0.79 | 0.43 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.08 | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 1.31 | 0.36 | 0.29*** | ||

| Interpersonal*Intelligence | −0.41 | 0.50 | −0.08 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.09 | ||

| Affective*Intelligence | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.30 | 0.16* | ||

| Lifestyle*Intelligence | 1.28 | 0.47 | 0.26** | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.08 | ||

| Antisocial*Intelligence | −0.16 | 0.58 | −0.03 | −0.66 | 0.34 | −0.15 | ||

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of fluid intelligence on the association between lifestyle psychopathic traits and indirect aggression scores for women.

Note. Low and high values represents +1.0 and −1.0 SD from the mean.

For men, step 1 was significant (F (3, 353) = 17.78, p <.001). Age (p=.016) and SUD (p<.001) were associated with indirect aggression. Step 2 was significant (F (7, 349) = 16.27, p < .001), and the antisocial facet was significant (p<.001). Step 3 was significant F (11, 345) = 12.31, p < .001), and the interaction between the affective facet and intelligence was significant (p=.016). Figure 3 shows the simple slopes analysis which found high intelligence moderated the association between higher levels of affective psychopathic traits and indirect aggression (p =.014).

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of fluid intelligence on the association between affective psychopathic traits and indirect aggression scores for men.

Note. Low and high values represents +1.0 and −1.0 SD from the mean.

Verbal Aggression

Results of the hierarchical linear regression predicting verbal aggression for men and women are displayed in Table 7. For women, step 1 was significant (F (3, 193) = 4.26, p =.006), and SUD (p =.018) and intelligence (p =.015) were positively associated with verbal aggression. No predictors were significant in Step 2 (F (7, 189) = 3.99, p <.001) nor in Step 3 (F (11, 185) = 2.97, p = .001). For men, step 1 was significant (F (3, 353) = 7.60, p <.001), and SUD (p<.001) and intelligence (p=.044) were positively associated with verbal aggression. Step 2 was significant (F (7, 349) = 4.87, p < .001), and the antisocial facet was significant (p=.030). No significant predictors emerged in Step 3 F (11, 345) = 3.48, p < .001).

Table 7.

Psychopathy and Intelligence as Predictors of Verbal Aggression

| Verbal Aggression: Women | Verbal Aggression: Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Step 1 | .06** | .06*** | ||||||

| Age | −0.21 | 0.21 | −0.07 | −0.37 | 0.22 | −0.09 | ||

| SUD | 0.97 | 0.41 | 0.17* | 1.69 | 0.38 | 0.24*** | ||

| Intelligence | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.18* | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.11* | ||

| Step 2 | .07** | .03* | ||||||

| Age | −0.23 | 0.21 | −0.08 | −0.38 | 0.22 | −0.09 | ||

| SUD | −0.49 | 0.59 | −0.08 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.10 | ||

| Intelligence | 0.60 | 0.23 | 0.18** | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.13* | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.09 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | −0.18 | 0.38 | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.25 | −0.03 | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.17 | −0.08 | 0.29 | −0.02 | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 0.72 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 0.20* | ||

| Step 2 | 02 | .01 | ||||||

| Age | −0.28 | 0.21 | −0.09 | −0.39 | 0.22 | −0.09 | ||

| SUD | −0.23 | 0.61 | −0.04 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.10 | ||

| Intelligence | 0.66 | 0.30 | 0.20* | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.11* | ||

| PCL:SV Interpersonal | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.11 | ||

| PCL:SV Affective | −0.17 | 0.42 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.26 | −0.03 | ||

| PCL:SV Lifestyle | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.16 | −0.08 | 0.29 | −0.02 | ||

| PCL:SV Antisocial | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.18* | ||

| Interpersonal*Intelligence | −0.10 | 0.39 | −0.03 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.10 | ||

| Affective*Intelligence | 0.15 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.02 | ||

| Lifestyle*Intelligence | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.05 | ||

| Antisocial*Intelligence | −0.31 | 0.44 | −0.09 | −0.28 | 0.29 | −0.08 | ||

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

p=.05

Discussion

The aims of the present study were to assess the association between the PCL:SV facets and fluid intelligence, and to test if fluid intelligence moderated the link between psychopathy and types of aggression for men and women. Drawing from a large community sample of men and women, zero order correlations showed psychopathy facets were unrelated to intelligence in women, whereas in men all psychopathy facets were negatively related to intelligence. However, when testing for sex differences while covarying for SUD, age, and other psychopathy facets, there were no sex differences and only the lifestyle facet was associated with lower intelligence. Prior research has suggested that psychopathy may manifest differently for men and women (Sprague et al., 2012; Thomson, 2019), but these results suggest that differential manifestations seem to be unrelated to intelligence, as measured by the RPM. In contrast, our findings suggest there are sex differences in the moderating role of intelligence in the association between psychopathy and aggression. Firstly, intelligence does not seem to be a meaningful contributor to a general measure of aggression (total AQ scores) in women, and does not moderate the association between psychopathy facets and aggression. Similar to women, intelligence was not uniquely related to general aggression in men - but unlike women, intelligence did moderate the association between the antisocial facet and aggression. Thus, low intelligence moderated the association between high antisocial psychopathic traits with high levels of aggression.

Drawing from Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory of Intelligence, fluid intelligence is contingent on bilateral frontal and parietal brain regions (Duncan et al., 2000; Kroger et al., 2002), which include brain regions found to be implicated in individuals with psychopathic traits (Abe et al., 2018; Korponay et al., 2017) and the same brain regions and poor intelligence have been associated with aggressive behavior (Boes et al., 2008; Choy et al., 2018; Jacob et al., 2018). In the present study, low intelligence only moderated the association between antisocial psychopathic traits and total scores of aggression. This may indicate that individuals with more extensive antisocial behaviors (e.g., criminal versatility) are more at risk of aggression when they have cognitive deficits. Thus, the moderating role of low intelligence between antisocial psychopathic traits and total scores of aggression may be explained by deficits in key brain regions (e.g., PFC, ACC).

For physical aggression, women and men who scored higher on the antisocial facet had higher physical aggression scores. For women only, affective and interpersonal facets were related to higher physical aggression. These associations were not moderated by intelligence for either men or women. Thus, as found in prior research, it seems that antisocial psychopathic traits are a gender-neutral risk factor for violence, while affective and interpersonal psychopathic traits may be female-specific risk factors for violence in women (Thomson, 2019). This is important from a treatment perspective, as violence intervention strategies that target antisocial behavior and criminal thinking styles may be effective in reducing psychopathy-related aggression in men and women. However, it is clear from the present study, and from past research, that women who engage in violence need gender-specific interventions to target female-specific risk factors. In this case, there is evidence that in women violence is related to the personality features of psychopathy, and recent research shows that this association is strengthened when women have histories of abuse (Thomson, Bozgunov, Aboutanos, Vasilev, & Vassileva, 2019). Thus, to reduce the heightened risk of psychopathy-related violence, treatment efforts in women need to become tailored to women’s needs by becoming trauma-informed (Thomson, 2019).

Indirect aggression was related to higher intelligence in both men and women, even after controlling for psychopathy. This highlights that manipulative and behind-the-back forms of aggression require intact cognitive function. The results also show that higher intelligence moderated the associations between psychopathy facets and indirect aggression differently for men and women. Women with high lifestyle facet scores and intelligence reported higher levels of indirect aggression. Whereas men with high affective facet scores and intelligence reported higher levels of indirect aggression. These results suggest that indirect aggression in men with high intelligence may be related to more affect-driven features of psychopathy than in women. This suggests that not all risk factors for psychopathy-related aggression are deficit-related Furthermore, this finding highlights that the affective features of psychopathy can be related to aggression in men, but the pathways or mechanisms in which this occurs may be different than for women.

Similarly, higher intelligence was also related to higher verbal aggression for men and women, while the antisocial facet of psychopathy was related to verbal aggression but only for men. Intelligence did not moderate any psychopathy associations with verbal aggression. The associations between higher intelligence and verbal aggression, across the sexes, highlight the significance of higher cognitive functioning (i.e., higher fluid intelligence levels) in predicting verbal forms of aggression in men and women more generally. In this case, verbal aggression was found to be related to non-verbal cognitive abilities, given that the RPM only accounts for non-verbal faculties associated with fluid intelligence. Ultimately, the positive associations detailed in the relation between intelligence and the behavioral manifestations of aggression (e.g., verbal aggression), may be attributable to the poor behavioral controls that are endemic to antisocial traits including psychopathy, but there is a missing link within this explanation as to why these associations were only detected in men. This may be, in part, because of the greater likelihood of men to engage more frequently in overt aggressive behaviors, such as verbal aggression, than women (Österman & Björkqvist, 2018). Similarly, these findings may also partially be explained by the lower prevalence of antisocial traits within women in community samples, or a lack of research that bolsters these claims. However, these findings do corroborate prior research that found a positive association between antisocial traits and verbal aggression in men only (Thomson, Bozgunov, Psederska, et al., 2019). Thus, antisocial psychopathic traits may be the most robust, male-specific predictor of verbal aggression, further highlighting the consistent pattern of sex differences that places these associations outside of a one-size-fits-all model of behavior. Nevertheless, findings remain consistent in revealing similarities between the men and women in that fluid intelligence had no significant role in this relationship.

The present study is not without limitations. Prior research has shown that psychopathy facets are differently related to subtypes of intelligence, such as the interpersonal facet is positively related to verbal intelligence (McKeown & Thomson, 2019). Therefore, we may have found different associations between psychopathy facets and specific forms of intelligence, which may differ for men and women. Furthermore, it is also possible that different forms and types of aggression may be more influenced by certain types of intelligence. For example, it may be that higher verbal intelligence moderates the link between the interpersonal facet and indirect/relational aggression. However, because the RPM does not measure verbal intelligence, we were unable to test this association. Furthermore, because this is the first study to test if fluid intelligence moderates the association between the four PCL:SV facets with these subtypes of aggression, it is important that findings are replicated in clinical and forensic samples where levels of aggression are higher. Nevertheless, our findings suggest there are important similarities between men and women in the association between psychopathy and intelligence, but also notable sex differences for the moderating role of intelligence in the link between psychopathy and aggression. It is important to recognize that the present sample had a large number of individuals with a prior SUD. Thus, interpretation of the present findings should keep this in mind. Current findings provide a good starting point for future studies to test these associations across different populations, with and without SUD. Lastly, although prior research has demonstrated validity of the psychopathy construct, as measured by the PCL:SV, in Bulgarian community samples (Wilson et al., 2014), future research is needed to assess cross-cultural generalizability of these results.

There has been longstanding debate on the association between psychopathy and intelligence. The first aim of the present study was to add evidence to this debate, by showing that when controlling for other facets of psychopathy, there were no significant sex differences in the relation between psychopathy and intelligence. Based on the research conducted to date, as well as the present study, there seems to be a consistency among studies showing a negative association between behavioral features of psychopathy and intelligence, which holds for both men and women, as we show. The second aim provided evidence that higher intelligence plays a role in strengthening the association between psychopathy and different types of aggression, further elucidating the nuanced pathways moderating physical, verbal, and indirect aggressive behaviors in men and women, underscoring the need for gender-responsive interventions and further research that parses apart the distinct mechanisms that characterize sex-specific trajectories of aggressive behavior.

Table 2.

Correlations and descriptives for main study variables: Men (n = 356)

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 1. Interpersonal | - | ||||||||

| 2. Affective | .55*** | - | |||||||

| 3. Lifestyle | .50*** | .64*** | - | ||||||

| 4. Antisocial | .52*** | .68*** | .73*** | - | |||||

| 5. Intelligence | −.13* | −.17** | −.22*** | −.22*** | - | ||||

| 6. Aggression | .28*** | .35*** | .42*** | .50*** | −.08 | - | |||

| 7. Physical aggression | .34*** | .45*** | .45*** | .57*** | −.05 | .80*** | - | ||

| 8. Indirect aggression | .29*** | .37*** | .38*** | .45*** | .02 | .70*** | .64*** | - | |

| 9. Verbal aggression | .15** | .15** | .17** | .24*** | .07 | .72*** | .52*** | .44*** | - |

| M | 1.95 | 2.17 | 2.66 | 2.79 | 107.28 | 42.86 | 18.26 | 14.35 | 9.15 |

| SD | 1.45 | 1.88 | 1.91 | 2.13 | 13.37 | 12.82 | 6.48 | 4.66 | 3.48 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Fogarty International Center under award number R01DA021421 (JV). Dr. Thomson’s work on this article was supported by the National Center for Injury and Violence Prevention and Control of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: K01CE003160.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: GV has ownership interests in the Bulgarian Addictions Institute, where data collection took place.

Contributor Information

Nicholas D. Thomson, Division of Acute Care Surgical Services, Department of Surgery and Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Salpi Kevorkian, Department of Surgery, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Kiril Bozgunov, Bulgarian Addictions Institute, Sofia, Bulgaria

Elena Psederska, Bulgarian Addictions Institute, Sofia, Bulgaria; Department of Cognitive Science and Psychology, New Bulgarian University, Sofia, Bulgaria.

Michel Aboutanos, Division of Acute Care Surgical Services, Department of Surgery, Virginia Commonwealth University Health

Georgi Vasilev, Bulgarian Addictions Institute, Sofia, Bulgaria.

Jasmin Vassileva, Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology, Institute for Drug and Alcohol Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University

References

- Abe N, Greene JD, & Kiehl KA (2018). Reduced engagement of the anterior cingulate cortex in the dishonest decision-making of incarcerated psychopaths. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(8), 797–807. 10.1093/scan/nsy050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). [Google Scholar]

- Andershed H, Kerr M, Stattin H, & Levander S. (2002). Psychopathic traits in non-referred youths: Initial test of a new assessment tool. In Blaauw E. & Sheridan L. (Eds.), Psychopaths: Current international perspectives (pp. 131–158). The Hague, the Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Beggs SM, & Grace RC (2008). Psychopathy, Intelligence, and Recidivism in Child Molesters: Evidence of an Interaction Effect. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(6), 683–695. 10.1177/0093854808314786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yaacov T, & Glicksohn J. (2018). Intelligence and psychopathy: A study on non-incarcerated females from the normal population. Cogent Psychology, 5(1). 10.1080/23311908.2018.1429519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR (2007). The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in morality and psychopathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(9), 387–392. 10.1016/J.TICS.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes AD, Tranel D, Anderson SW, & Nopoulos P. (2008). Right anterior cingulate: A neuroanatomical correlate of aggression and defiance in boys. Behavioral Neuroscience, 122(3), 677–684. 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozgunov K, Vasilev G, & Vassileva J. (2014). Investigating the association between psychopathy and intelligence in the Bulgarian population. Clinical and Consulting Psychology VI, 1(19), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, & Warren WL (2000). The Aggression Questionnaire manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB (Raymond B. (1971). Abilities: their structure, growth, and action. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Choy O, Raine A, & Hamilton RH (2018). Stimulation of the Prefrontal Cortex Reduces Intentions to Commit Aggression: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Stratified, Parallel-Group Trial. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 38(29), 6505–6512. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3317-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley H. (1988). The Mask of Sanity (5th ed.). St. Louis: Emily S. Cleckley. [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi Matt, Vaughn MG, Beaver KM, & Wright JP (2010). The Hannibal Lecter Myth: Psychopathy and Verbal Intelligence in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(2), 169–177. 10.1007/s10862-009-9147-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas KS, Strand S, Belfrage H, Fransson G, & Levander S. (2005). Reliability and Validity Evaluation of the Psychopathy Checklist:: Screening Version (PCL:SV) in Swedish Correctional and Forensic Psychiatric Samples. Assessment, 12(2), 145–161. 10.1177/1073191105275455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J, Seitz RJ, Kolodny J, Bor D, Herzog H, Ahmed A, … Emslie H. (2000). A neural basis for general intelligence. Science (New York, N.Y.), 289(5478), 457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Bonavila S, Morales-Vives F, Cosi S, & Vigil-Colet A. (2017). How impulsivity and intelligence are related to different forms of aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 66–70. 10.1016/J.PAID.2017.05.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (1996). User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I Disorders— Research version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo C, Neumann CS, & Velotti P. (2020). Psychopathy and Aggression: The Role of Emotion Dysregulation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 088626051990094. 10.1177/0886260519900946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham D, Melvin GA, & Gullone E. (2016). The Role of Anger in the Relationship Between Internalising Symptoms and Aggression in Adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2674–2682. 10.1007/s10826-016-0435-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guy LS, & Douglas KS (2006). Examining the utility of the PCL:SV as a screening measure using competing factor models of psychopathy. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 225–230. 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Harpur TJ, Hakstian a. R., Forth AE, Hart SD, & Newman JP (1990). The revised Psychopathy Checklist: Reliability and factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 2(3), 338–341. 10.1037/1040-3590.2.3.338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, & Neumann CS (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4(1), 217–246. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SD, Cox DN, & Hare RD (1995). The Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version. North Tonowanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzen H, Köhler D, Godt N, Geiger F, & Huchzermeier C. (2011). Psychopathy, intelligence and conviction history. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 34(5), 336–340. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson DK (1939). Psychopathic states. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, INC. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob L, Haro JM, & Koyanagi A. (2018). Association between intelligence quotient and violence perpetration in the English general population. Psychological Medicine, 1–8. 10.1017/S0033291718001939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambroes T, Jansen LMC, Ven VDPM, Claassen T, Glennon JC, Vermeiren RRJM, … Popma A. (2018). Dimensions of psychopathy in relation to proactive and reactive aggression: Does intelligence matter? Personality and Individual Differences, 129, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P, & Kerr M. (2005). Psychopathy and intelligence: a second look. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(4), 357–369. 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korponay C, Pujara M, Deming P, Philippi C, Decety J, Kosson DS, … Koenigs M. (2017). Impulsive-antisocial psychopathic traits linked to increased volume and functional connectivity within prefrontal cortex. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(7), 1169–1178. 10.1093/scan/nsx042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger JK, Sabb FW, Fales CL, Bookheimer SY, Cohen MS, & Holyoak KJ (2002). Recruitment of anterior dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in human reasoning: a parametric study of relational complexity. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 12(5), 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, & Andrews BP (1996). Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal populations. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(3), 488–524. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6603_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lösel F, & Murray J. (2016). Intelligence as a protective factor against offending: A metaanalytic review of prospective longitudinal studies. Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 4–18. 10.1016/J.JCRIMJUS.2016.02.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown A, & Thomson ND (2019). Psychopathy and Intelligence: A Profile of High-Risk Violent Female Offenders. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, & Hare RD (2008). Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 893–899. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Hare RD, & Newman JP (2007). The Super-Ordinate Nature of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21(2), 102–117. 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.2.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman H, Merckelbach H, & Cima M. (2009). Performance intelligence, sexual offending and psychopathy. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 15(3), 319–330. 10.1080/13552600903195057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Österman K, & Björkqvist K. (2018). Sex differences in aggression. In Ireland JL, Birch P, & Ireland C. (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Human Aggression (pp. 47– 58). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Raven J, Raven JC, & Court JH (2000). Raven manual: Section III standard progressive matrices. Oxford: Oxford Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CA, & Knight RA (2014). Relating sexual sadism and psychopathy to one another, non-sexual violence, and sexual crime behaviors. Aggressive Behavior, 40(1), 12–23. 10.1002/ab.21505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Neumann CS, Leistico A-MR, & Zalot AA (2004). Psychopathy in youth and intelligence: an investigation of Cleckley’s hypothesis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(4), 731–742. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spironelli C, Segrè D, Stegagno L, & Angrilli A. (2014). Intelligence and psychopathy: a correlational study on insane female offenders. Psychological Medicine, 44(1), 111–116. 10.1017/S0033291713000615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague J, Javdani S, Sadeh N, Newman JP, & Verona E. (2012). Borderline personality disorder as a female phenotypic expression of psychopathy? Personality Disorders, 3(2), 127–139. 10.1037/a0024134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND (2019). Understanding Psychopathy: The Biopsychosocial Perspective. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND (2020a). An Exploratory Study of Female Psychopathy and Drug-Related Violent Crime. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 088626051769087. 10.1177/0886260517690876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND, Kevorkian S, & Thomson AA (2020b). Psychopathy and aggression. In Vitale JE (Ed.), Complexity of psychopathy. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND, Bozgunov K, Aboutanos M, Vasilev G, & Vassileva J. (2019). Physical Abuse Moderates the Psychopathy-Violence Link Differently for Men and Women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson N, Bozgunov K, Psederska E, Aboutanos M, Vasilev G, & Vassileva J. (2019). Lifetime Physical Abuse Moderates the Psychopathy-Violence Link Differently for Men and Women. Biological Psychiatry, 85(10), S272. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.03.689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND, Bozgunov K, Psederska E, & Vassileva J. (2019). Sex differences on the four-facet model of psychopathy predict physical, verbal, and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 45(3), 265–274. 10.1002/ab.21816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND, & Centifanti LCM (2018). Proactive and Reactive Aggression Subgroups in Typically Developing Children: The Role of Executive Functioning, Psychophysiology, and Psychopathy. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49(2), 197–208. 10.1007/s10578-017-0741-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND, Galusha C, Wheeler EMA, & Ingram L. (2019). Psychopathy and Intelligence: A Study on Male Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity (NGRI) Acquittees. Journal of Behavioral Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson ND, Kiehl KA, & Bjork JM (2018). Predicting Violence and Aggression in Young Women: The Importance of Psychopathy and Neurobiological Function. Physiology & Behavior, 201, 130–138. 10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2018.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakhtin AA, Ryman SG, Flores RA, & Jung RE (2014). Functional brain networks contributing to the Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory of Intelligence. NeuroImage, 103, 349–354. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitacco MJ, Neumann CS, & Jackson RL (2005). Testing a Four-Factor Model of Psychopathy and Its Association With Ethnicity, Gender, Intelligence, and Violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 466–476. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitacco MJ, Neumann CS, & Wodushek T. (2008). Differential Relationships Between the Dimensions of Psychopathy and Intelligence: Replication With Adult Jail Inmates. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(1), 48–55. 10.1177/0093854807309806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale JE, Smith SS, Brinkley CA, & Newman JP (2002). The Reliability and Validity of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised in a Sample of Female Offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 29(2), 202–231. 10.1177/0093854802029002005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts AL, Salekin RT, Harrison N, Clark A, Waldman ID, Vitacco MJ, & Lilienfeld SO (2016). Psychopathy: Relations with three conceptions of intelligence. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7(3), 269–279. 10.1037/per0000183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weizmann-Henelius G, Viemerö V, & Eronen M. (2004). Psychopathy in violent female offenders in Finland. Psychopathology, 37(5), 213–221. 10.1159/000080716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MJ, Abramowitz C, Vasilev G, Bozgunov K, & Vassileva J. (2014). Psychopathy in Bulgaria: The cross-cultural generalizability of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(3), 389–400. 10.1007/s10862-014-9405-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]