Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, intensive care units (ICU) introduced restrictions to in-person family visiting to safeguard patients, healthcare personnel, and visitors.

Methods

We conducted a web-based survey (March–July 2021) investigating ICU visiting practices before the pandemic, at peak COVID-19 ICU admissions, and at the time of survey response. We sought data on visiting policies and communication modes including use of virtual visiting (videoconferencing).

Results

We obtained 667 valid responses representing ICUs in all continents. Before the pandemic, 20% (106/525) had unrestricted visiting hours; 6% (30/525) did not allow in-person visiting. At peak, 84% (558/667) did not allow in-person visiting for patients with COVID-19; 66% for patients without COVID-19. This proportion had decreased to 55% (369/667) at time of survey reporting. A government mandate to restrict hospital visiting was reported by 53% (354/646). Most ICUs (55%, 353/615) used regular telephone updates; 50% (306/667) used telephone for formal meetings and discussions regarding prognosis or end-of-life. Virtual visiting was available in 63% (418/667) at time of survey.

Conclusions

Highly restrictive visiting policies were introduced at the initial pandemic peaks, were subsequently liberalized, but without returning to pre-pandemic practices. Telephone became the primary communication mode in most ICUs, supplemented with virtual visits.

Keywords: Visiting, Restriction, Intensive care, Family, COVID-19

1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, countries across the world introduced restrictions to intensive care unit (ICU) in-person visiting to safeguard patients, healthcare personnel, and visitors [[1], [2], [3]]. In many countries, rapid policy implementation resulted in restriction of all visiting or visits only for immediate family or at end-of-life [2,[4], [5], [6]]. Such restrictions caused significant distress to patients, their friends, family and relatives, and the staff caring for them [[7], [8], [9]]. In response, new ways to connect family to patients and to communicate with the ICU team were established.

Emerging evidence on ICU communication practices and virtual visiting during the pandemic describes variable practices in a regional location or city (e.g. Michigan in the US [6]), a single country (e.g. Canada [2]) or a nation (e.g. the United Kingdom (UK) [4,10]). These studies report the adoption of family communication teams, frequent telephone calls to provide information, and ad hoc implementation of virtual visiting strategies using video-conferencing software, smartphones, and tablets with little initial guidance from professional societies or peers [10]. To-date, no comprehensive study has assessed international variation in visiting policy and practices before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such data could guide decision makers informing local and national policy as to best practices, resource allocation, as well as professional society guidelines.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to report on ICU visiting worldwide at three time-points, before the COVID-19 pandemic, at peak of admissions during a pandemic wave, and at time of survey completion.

2. Methods

We conducted a web-based cross-sectional survey collecting data from ICUs worldwide on visiting policies and methods of communication with relatives and friends of ICU patients prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We report the study according to the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS) [11].

2.1. Survey instrument

We designed a three domain, 32-item survey refined by study investigators over iterative email rounds. The survey was evaluated for content validity, language clarity, time to complete, and ease of administration by the investigators and other collaborators. Items were reformatted, refined, and reduced according to feedback. Pilot testing was not conducted. Test-retest reliability was not performed as the survey primarily sought objective description as opposed to opinion or perceptions. Responses during the content validity evaluation phase were not included in the data analyses.

The survey instrument (see electronic supplement) contained items investigating 3 domains over three timepoints – before COVID-19, at peak ICU admissions, and at time of survey completion. We also distinguished between newly created (for the pandemic) and pre-existing ICUs.

We used the following definitions:

-

•

‘Before COVID-19’ to provide baseline data before restrictions to visiting or changes in ICU organization.

-

•

‘At peak’, defined as the period with the highest number of COVID-19 patients in the ICU prior to survey completion. This corresponds to the first or second pandemic wave peaks depending on geographical location.

-

•

‘At time of survey’, defined as the time of survey completion.

Survey domains comprised: (1) staffing ratios and visiting hours; (2) how visiting and family communication policies were developed and modified over the pandemic; (3) communication strategies and use of virtual visiting. Domain (1) was investigated at the 3 timepoints while domains (2) and (3) were investigated at time of survey.

The survey was translated by the investigators from English to Italian (AC), Japanese (TU), French (AT, NS, FB) and Spanish (LG) languages. Translated versions were checked for content and contextual validity by the study investigators. Back-translation was not performed.

2.2. Distribution

The survey was prepared in four languages using the SurveyMonkey® platform (SVMK Inc., San Mateo, USA) by the principal investigator and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) research staff (AT, GF). The survey was promoted on the ESICM website and open to participants from 18/03/2021 to 05/07/2021. Participants were invited via email using mailing lists of the endorsing societies and research groups (See appendix). In addition, ad hoc emails and advertisements were made via study investigators personal networks and social media accounts. COVISIT was a unit level survey, with an explicit plan to analyze one response per ICU. We defined an ICU as any unit providing advanced monitoring and/or organ supportive therapy to critically ill patients.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data were exported from SurveyMonkey, prepared using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and analyzed using STATA 15 (StataCorp LLC., College Station, TX). Duplicate responses were identified manually using country, city, hospital name, and department data. Duplicates were excluded following a pre-specified order according to the respondent role i.e. using the following hierarchy: medical director, nurse unit manager or nursing director, senior medical role, senior nursing role, medical other, nursing other, administrative role, other. Geographical regions and income categories were defined using the United Nations M49 standard [12]. We asked each respondent to confirm data validity in the last question of the survey as described in the electronic supplement. Unconfirmed data or questionnaires not completed to this final item were excluded.

Continuous variables were transformed into categorical variables to describe frequency and percentages using clinically relevant cutoffs. ICUs completed data for relevant time points only (before, at peak, and at time of survey). For ICUs that were at the peak at the time of survey response, peak data is equal to time of survey. Values were reported for available responses for each variable at the relevant timepoint. Number of missing data were shown with item denominators.

3. Results

The survey was opened 1352 times, however 579 were incomplete entries. We received 773 complete surveys, 667 from unique ICUs in 640 hospitals and included in analyses (see flowchart in figure esup-1). Of the 667, 52% (344/667) were from Europe and Central Asia, 18% (118/667) from Middle East and North Africa, 15% (100/667) from East Asia and the Pacific, 7% (48/667) from Latin America and the Caribbean, 4% (28/667) from Sub-Saharan Africa, 3% (18/667) from South Asia, and 2% (11/667) from North America (See Figure esup-2 and table esup-1). Intensive care units from high-income countries comprised 60% (397/667) of responses, with 23% (156/667), 14% (94/667), and 3% (20/667) from upper-middle, lower-middle, and low-income countries respectively. Most responses (76%, 508/667) were from ICUs in public hospitals, with 13% (89/667), 9% (59/667), and 2% (11/667) from private for-profit, private not-for-profit and mixed funding hospitals respectively. Of the 667 ICUs, 14% (90/667) were created specifically for the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospital size was available for 510 ICUs and ranged from less than 250 beds (33%, 169/510), 250 to 499 beds (25%, 128/510), 500 to 999 beds (26%, 131/510) and more than 1000 beds (16%, 82/510). Eleven per cent (73/667) of ICUs were at peak COVID-19 admissions at time of responding. For those ICUs not at peak, the mean (SD) time between at peak and survey completion was 8 (5) months.

3.1. ICU capacity and staffing

At peak, 38% (249/651) of responding ICUs reported >90% of admitted patients had a COVID-19 diagnosis, dropping to 16% (105/664) of ICUs at time of survey (Table 1 ). Most (57%, 262/458) reported increased bed capacity before COVID-19 and at peak admissions, with 44% (256/582) still using peak bed capacity at time of survey. The percentage of ICUs with a ratio of 1 senior doctor to >10 patients increased from 4% (16/423) before COVID-19 to 19% (100/535) at peak and reduced to 15% (80/530) at time of survey. Those with a ratio of 1 nurse to >3 patients increased from 7% (32/442) before COVID-19 to 15% (86/561) at peak subsequently reducing to 12% (67/555) at time of survey. Geographical variation in ratios was observed with lower staff-to-patient ratios in the South Asia, East Asia and Pacific, and North American regions (Table esup-1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of ICUs of respondents over the three study periods.

| Characteristics | Before COVID-19 |

At Peak |

At time of survey |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| ICU patients with COVID-19 (%) | n = 651 | n = 664 | |

| Less than 25 | – | 218 (33) | 379 (57) |

| 25 to 49 | – | 68 (10) | 72 (11) |

| 50 to 89 | – | 116 (18) | 108 (16) |

| 90 or more | – | 249 (38) | 105 (16) |

| Total number of ICU beds | n = 521 | n = 662 | n = 658 |

| 1 to 8 | 143 (27) | 110 (17) | 152 (23) |

| 9 to 16 | 195 (37) | 203 (31) | 221 (34) |

| 17 to 24 | 76 (15) | 130 (20) | 112 (17) |

| 25 to 40 | 58 (11) | 110 (17) | 92 (14) |

| More than 40 | 49 (9) | 109 (16) | 81 (12) |

| Senior doctor to patient ratio | n = 423 | n = 535 | n = 530 |

| Less than 1:6 | 210 (50) | 211 (39) | 225 (42) |

| 1:6 to 1:10 | 197 (47) | 224 (42) | 225 (42) |

| More than 1:10 | 16 (4) | 100 (19) | 80 (15) |

| Junior doctor-to-patient ratio | n = 345 | n = 458 | n = 454 |

| Less than 1:6 | 226 (66) | 267 (58) | 269 (59) |

| 1:6 to 1:10 | 108 (31) | 141 (31) | 144 (32) |

| More than 1:10 | 11 (3) | 50 (11) | 41 (9) |

| Nurse-to-patient ratio | n = 442 | n = 561 | n = 555 |

| 1:1 | 77 (17) | 86 (15) | 86 (15) |

| 1:2 | 211 (48) | 244 (43) | 256 (46) |

| 1:3 | 122 (28) | 145 (26) | 146 (26) |

| More than 1:3 | 32 (7) | 86 (15) | 67 (12) |

Footnotes: ICU characteristics at the 3 study time points. Respondents only provided data for the periods that were relevant to their ICU (i.e., ICUs created for the COVID-19 pandemic did not provide ‘before’ data, and peak data was included as time of survey for those ICUs currently at peak). % figures do not sum up to 100 due to rounding.

3.2. ICU visiting

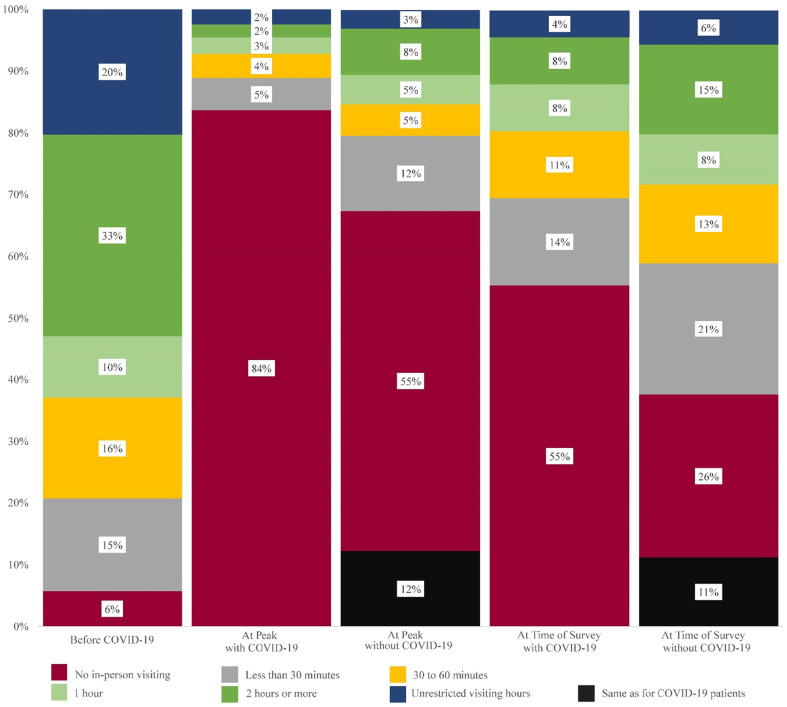

Before the pandemic, 20% (106/525) of ICUs had unrestricted visiting hours; 6% (30/525) did not allow in-person visiting. At peak, 84% (558/667) of ICUs had implemented a no in-person visiting policy for patients with COVID-19; 66% (440/664) for patients without COVID-19 (Fig. 1 ). At peak, 12% (81/664) of ICUs applied the same visiting policy irrespective of COVID-19 diagnosis; 11% (75/667) at time of survey. At time of survey, the policy of ‘no in-person visiting’ had decreased to 55% (369/667) for patients with COVID-19; 33% (218/667) for patients without. Between peak and time of survey periods, 48% (237/493) had increased in-person visiting hours although this had not returned to pre-pandemic levels. Unrestricted visiting hours remained uncommon, ranging from 2% to 6% at peak and time of survey. As shown in table esup-2, in-person visiting restrictions varied around the world with a larger proportion of East Asian and Pacific ICUs having no in-person visiting policies compared to other regions. At time of survey, 10% (71/667) of responding ICUs reported unrestricted in-person visiting policy in other hospital wards.

Fig. 1.

Visiting policies before COVID-19, at peak, and at time of survey timepoints according to the COVID-19 status of the patients. Footnotes: Times represent the total duration allowed for in-person visiting each day.

3.3. Regulations and policies

At time of survey, most ICUs (67%, 447/667) had a written visiting policy that was designed or revised to include COVID-19 specifics with 53% (354/667) reporting a government mandated restriction to all hospital visiting. As detailed in Tables 2 and esup-3, the policy could be modified for specific patients or situations with decision-making responsibility assigned to the attending doctor in 45% (300/667), the ICU director in 44% (292/667,) and the nursing director in 17% (114/667). A written request from relatives was required in 8%. Eighty-three percent (491/590) of respondents perceived that at least in some cases relatives were offered more liberal in-person visiting options than allowed in the set policy.

Table 2.

Regulations and policies in respondents' ICUs at time of survey.

| Visiting policies | n (%) |

|---|---|

| n = 667 | |

| Written visiting policy designed or revised for COVID-19 | |

| Yes | 447 (67) |

| Government mandated visiting policy a | |

| No, there are no government mandated restrictions in place | 313 (47) |

| Yes, but our ICU has its own policy | 157 (24) |

| Yes, and our ICU follows the policy | 197 (30) |

| COVID-19 related hospital visiting policy for the hospital wards b | |

| No, the hospital does not restrict visiting for wards | 71 (11) |

| Visiting policies in wards are variable and different for each ward of our hospital | 90 (13) |

| Yes, and our ICU follows the same policy | 289 (43) |

| Yes, and our ICU is more restrictive than hospital policy | 112 (17) |

| Yes, and our ICU is less restrictive than the hospital policy | 105 (16) |

| ICU visiting policy be changed for specific patients or situations b | |

| Not relevant - no specific policy | 46 (7) |

| It requires a written request from the relatives | 53 (8) |

| The bedside nurse can make the decision | 60 (9) |

| The doctor can make the decision | 300 (45) |

| The ICU medical director can make the decision | 292 (44) |

| The ICU nursing director can make the decision | 114 (17) |

| Hospital hierarchy can make the decision | 130 (19) |

| It requires approval at a higher level | 21 (3) |

| The ICU visiting policy cannot be changed for specific situations or patients | 74 (11) |

| Estimated % difference between set policy and what is offered to relatives | n = 590 |

| 0 | 99 (17) |

| 1 to 9 | 106 (18) |

| 10 to 24 | 202 (34) |

| 25 to 49 | 95 (16) |

| 50 or more | 88 (15) |

Footnotes: a % do not sum to 100 due to rounding, b % do not sum to 100 as participants could select multiple options.

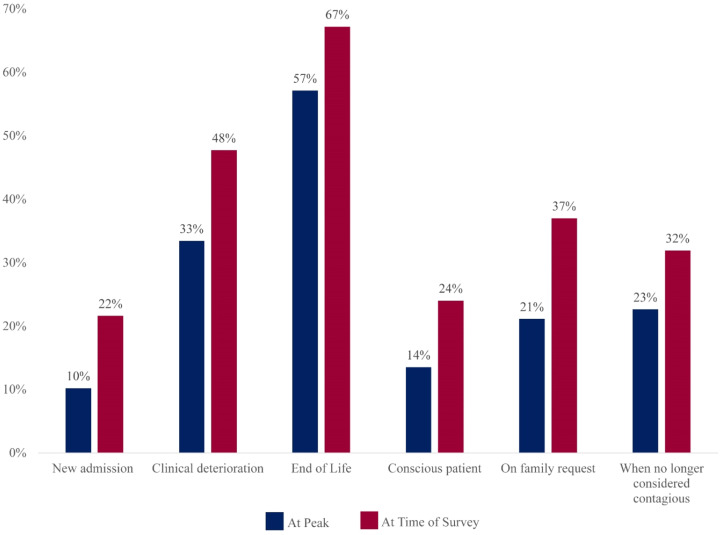

The most frequent situations in which the visiting policy was liberalized were end-of-life, followed by clinical deterioration (Fig. 2 ). The respondents' perceived reasons why relatives did not or could not visit when in-person visiting was in theory possible included: fear of catching COVID-19 (29%), own COVID-19 illness (26%), inability to enter the hospital (26%), inability to travel due to lockdown (21%), fear of being overwhelmed by the ICU environment (11%), and fear of disturbing clinical care (10%).

Fig. 2.

Reasons for non-adherence to restrictive in-person visiting policies.

Footnotes: Reasons why visitors may be allowed to visit or allowed for longer time periods despite restrictions.

3.4. Communication and support for relatives

At time of survey, 43% (285/667) of ICUs had a physical and/or digital information booklet available which contained information on COVID-19, visiting policies, and use of protective personal equipment (PPE). Most (55%, 353/646) provided regular general and daily updates on the patient's status over the telephone. Slightly fewer ICUs (50%, 306/615) used the telephone for formal meetings and discussions regarding prognosis, treatment plans, or end-of-life discussions (Table 3 ). Virtual visiting was available in 63% (418/667) of ICUs, but only protocolised in 14% (92/667). Dedicated virtual visiting devices such as tablets and computers were available in 67% (279/418) of these ICUs, however 24% (102/418) reported use of personal devices of staff members. Use of video-technology for communication and virtual visiting was less frequently available for ICUs from the Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa compared to other regions (Table esup-4).

Table 3.

Communication and support for relatives at time of survey.

| Family support | n (%) |

|---|---|

| ICU information booklet contains information on COVID-19 | n = 667 |

| Not available | 382 (57) |

| Digital format only | 122 (18) |

| Physical format (booklet) | 122 (18) |

| Both (digital + physical formats) | 41 (6) |

| Mode of delivery of general or daily updatesa | n = 646 |

| In person at bedside (within visiting restrictions) | 143 (22) |

| In person, but outside the ICU clinical area. | 230 (36) |

| In person, but outside of the hospital and outdoors | 26 (4) |

| On the phone, on family's request | 279 (43) |

| On the phone, families called at regular intervals by ICU staff | 353 (55) |

| Via virtual/video-conferences | 130 (20) |

| Formal meetings or discussions regarding prognosis, treatment plans or end of life care a | n = 615 |

| In person in the same place as before COVID-19 | 230 (37) |

| In person but in an area dedicated to meetings setup since COVID-19 | 176 (29) |

| Outside of the building, outdoors | 36 (6) |

| Via video-conference | 103 (17) |

| Over the phone | 306 (50) |

| Virtual / video visiting | n = 667 |

| Is not available | 249 (37) |

| Is available, but use is not protocolized | 326 (50) |

| Is available, and use is protocolized | 92 (14) |

| Which devices are used for virtual visiting? a | n = 418 |

| Personal devices provided by staff members | 102 (24) |

| Personal devices provided by patients or their relatives | 180 (43) |

| Computers that are also used for patient care / clinical information systems | 30 (7) |

| Devices dedicated to virtual visiting and not used for something else | 279 (67) |

| Devices usually dedicated to virtual clinical rounds repurposed for virtual visiting | 31 (7) |

| How is virtual visiting organized? a | n = 402 |

| Staff organized appointments offered to relatives on a regular basis | 138 (34) |

| Staff organized appointments when requested by the doctor or nurse | 153 (38) |

| Appointments organized when requested by relatives | 223 (55) |

| Virtual visiting initiated on request from a relative or patient (no appointment) | 176 (44) |

| How frequently do you use virtual visiting? | n = 418 |

| Daily or almost daily for most patients | 111 (27) |

| Several times per week for most patients | 126 (30) |

| Not more than once a week for most patients | 47 (11) |

| Infrequently, only for a few patients | 128 (31) |

| Never | 6 (1) |

Footnotes: a % figures do not sum up to 100 as participants could select multiple options.

4. Discussion

Given the importance of family visiting to ICU patients', relatives', and the ICU team mental health, we conducted this study to describe family visiting and communication policies before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most respondents reported increased bed capacity and reduced staff-to-patient ratios in their ICUs. We found restrictive in-person visiting policies were introduced across all geographic regions, frequently due to government mandate, with most ICUs having a no-visitor policy, particularly for patients with COVID-19. Although in-person visiting restrictions became more liberal over time, visiting practices remained significantly restricted at time of survey and had not returned to pre-COVID-19 baseline. Telephone was the primary communication strategy across all regions. However, at the time of survey, virtual visiting was a common adjunct to facilitating communication, although rarely protocolized and sometimes conducted using staff or patient personal devices.

Our findings are consistent with results of previous more localised studies. In a Canadian environmental policy scan, Fiest and colleagues reported 66% of ICUs offered unrestricted visiting before the COVID-19 pandemic, however by May 2020, 86% had implemented a no in-person visiting policy [2]. Surveying 49 ICUs in Michigan (USA) in April–May 2020, Valley and colleagues found 98% had a no-visitor policy but 59% allowed exceptions such as end-of-life and specific clinical situations [6]. Similar findings were reported from Denmark, Norway and Sweden [13], and from the UK. These restrictions on in-person visiting and the delivery of family-centred care have been so widespread they have been described as “an outbreak of restrictive ICU visiting policies” [7,14].

We report wide variability in government mandates and restrictions to ICU visiting with ICUs from the East-Asia and Pacific region (mostly Japan and Australia) reporting a higher proportion of “no in-person visiting” than other regions. Interestingly, this region had the lowest proportion of COVID-19 patients in responding ICUs, at both peak and time of survey periods. While both countries pursued SARS-COV-2 strong suppression or elimination strategies, most ICUs from Australia reported a government mandated restriction, while those from Japan did not. Differences highlight the complex interplay between different levels of government intervention with societal and cultural differences resulting in global variability in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We identified that by early to mid-2021, the majority of responding ICUs had implemented some form of virtual visiting albeit mostly non-protocolized, with a third using it daily and another third several times per week. Protocols are known to minimize practice variation, facilitate adoption of new information, improve communication, and decrease errors [15]. Further to these benefits, protocolizing virtual visiting may improve the set up and conduct of virtual visiting as well as identification of patients for whom virtual- or in-person visiting would be appropriate. Although an imperfect replacement for family in-person presence, virtual visiting can mitigate the effects of visiting restrictions by enabling a closer, deeper, and more realistic connection than can be achieved with voice only telephone calls. Rose and colleagues recently surveyed 182 ICUs in the UK where virtual visiting has been implemented extensively [10]. Reported benefits were reducing patients' distress, reorienting patients with delirium, and improving staff morale. While the main indication for virtual visiting was ‘alert and oriented patients’ (88%), it was also used at the end of life (63%), during rehabilitation activities (52%), and for unconscious or sedated patients (45%). Early and widespread adoption of virtual visiting highlights recognition of the importance of family presence by and for ICUs caregivers. Videoconferencing for daily updates or formal discussions may improve the quality of family communication compared to voice only telephone calls. However, some relatives may experience difficulties with technology and lack access to informal or formal support to use it. Anxiety may arise from the lack of in-person contact and difficulties communicating via a screen. In these situations, staff may be unable to provide the same psychological support they would with in-person visiting. Concerns regarding security, privacy, and lack of prior consent in unconscious patients are known barriers to virtual visiting [10]. Further, this communication method may not reach the same quality of information delivery as a face to face conversation [16]. Indeed, a proportion of our respondents conducted formal meetings in the same place as before, in a newly setup and dedicated area or outdoors.

Impacting all actors within the circle of ICU care, restrictions to visiting are associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression for ICU team members [17], fear and anxiety for family members [18], and increased incidence of delirium and emotional distress for the patients [8,19]. Despite diminishing numbers of COVID-19 admissions, our data suggest that 12 to 18 months after the onset of the pandemic, ICUs had not returned to pre-pandemic levels of in-person visiting. Most respondents indicated that they offered, at least sometimes, more flexible visiting than the set policy. This included situations where compassion and family presence are most obviously required such as in the end of life, but also done for conscious patients or on family's requests.

Reopening our ICUs to visitors is recommended by professional societies and is outlined with guidance documents worldwide [3,5,7,20]. While recognizing resource allocation may be limited for ICUs still dealing with COVID-19 [21], there is a need for health policymaker involvement to enable supportive policies and provision of resources to reinstate previous levels of in-person visiting with addition of virtual visiting as an adjunct enabling greater flexibility for relatives unable to visit in person. Indeed, the implementation of succinct, prioritized, flexible and evidence-based visiting policies with involvement of a diverse stakeholder taskforce has been recommended to facilitate the return of family-centred care in the ICU [22]. Programs that delineate visiting policies according to levels of hospital and ICU strain, with valets checking for COVID-19 symptoms and vaccination status (where applicable) while assisting with PPE outline a framework that may facilitate reopening hospitals and ICUs to visitors [1]. Importantly, similar to the case prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the process of re-implementing a more open visiting strategy must involve shared decision making and governance among all ICU team members, availability of appropriate family spaces, and always ensuring safety and well-being of visitors, patients, and staff [3,23,24]. We must work towards the return of family centred critical care, including open visiting policies. Virtual visiting can then be used to facilitate the presence of those family members who are unable to visit, rather than as the norm in the setting of blanket in-person visiting restrictions.

Limitations of our survey include the challenges of reporting a status representative of the worldwide situation given the evolving nature of the pandemic. To obtain perspectives on how visiting policies changed over time, we collected data on 3 time-points which differed according to region, and with definition of peak subject to respondent interpretation. We defined at peak as the period the responding ICU had the highest number of COVID-19 patients, however this did not enable us to differentiate practices and policies that may have differed between 1st and 2nd pandemic waves. We are unable to report a response rate due to a multi-modal and snowballing approach to survey distribution. Our results are subject to self-selection bias with responders from ICUs with a specific interest in visiting restrictions. As with any self-reported survey without on-site data validation, described practices may reflect opinion as opposed to actual practice. Lastly, in our study there was an over-representation of ICUs from Europe, Central Asia, East Asia and Pacific regions compared to other regions, which decreases generalisability of our findings.

5. Conclusion

Our international survey demonstrates highly restrictive in-person visiting policies introduced early in the COVID-19 pandemic, which have since been liberalized, but have not returned to pre-pandemic practices. Telephone became the primary communication mode supplemented with virtual visits by 2021. Although no in-person visiting policies were dominant, most ICUs allowed exceptions, most commonly in end-of-life situations. It is now critical to restore previous levels of flexible in-person visiting practices. Continuation of virtual visiting for those family members unable to visit could become a routine option outside of pandemic conditions, providing further flexibility in visiting thereby promoting family-centred intensive care.

Ethics approval

The study was approved and granted an exemption of full ethical review by the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (LNR/2020/QRBW/71880), Brisbane, Australia.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Financial disclosure statement

This project was conducted without funding. Guy Francois is an employee of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) and as such his time working on the project and access to SurveyMonkey platform was supported by ESICM.

CRediT author statement

Conceptualization: Alexis Tabah.

Methodology: Alexis Tabah, Muhammed Elhadi, Andrea Cortegiani, Takeshi Unoki, Laurą Galarza, Regis Goulart Rosa, Francois Barbier, Nathalie Ssi Yan Kai, Marlies Ostermann, Jan J De Waele, Kirsten Fiest, Julie Benbenishty, Mariangela Pellegrini.

Translations: Alexis Tabah Nathalie Ssi Yan Kai, François Barbier, Andrea Cortegiani, Laura Galarza, Takeshi Unoki.

Resources and Software: Alexis Tabah, Guy Francois,

Validation: Andrea Cortegiani, Jan J De Waele, Takeshi Unoki, Laurą Galarza, Francois Barbier, Alexis Tabah.

Data curation: Alexis Tabah, Muhammed Elhadi.

Formal analysis: Emma Ballard.

Investigation: Alexis Tabah, Muhammed Elhadi,Andrea Cortegiani, Maurizio Cecconi, Takeshi Unoki, Laurą Galarza, Regis Goulart Rosa, Francois Barbier, Elie Azoulay, Kevin B Laupland, Nathalie Ssi Yan Kai, Marlies Ostermann, Guy Francois, Jan J De Waele, Kirsten Fiest, Peter Spronk, Julie Benbenishty, Mariangela Pellegrini, Louise Rose.

Project administration: Alexis Tabah, Guy Francois.

Supervision: Jan J De Waele, Louise Rose, Alexis Tabah.

Visualization; Alexis Tabah, Emma Ballard.

Roles/Writing –original draft: Alexis Tabah, Louise Rose.

Writing – review & editing: Alexis Tabah, Muhammed Elhadi, Emma Ballard, Andrea Cortegiani, Maurizio Cecconi, Takeshi Unoki, Laurą Galarza, Regis Goulart Rosa, Francois Barbier, Elie Azoulay, Kevin B Laupland, Nathalie Ssi Yan Kai, Marlies Ostermann, Guy Francois, Jan J De Waele, Kirsten Fiest, Peter Spronk, Julie Benbenishty, Mariangela Pellegrini, Louise Rose.

Conflict of interest statement

Alexis Tabah has nothing to disclose, Muhammed Elhadi has nothing to disclose, Emma Ballard has nothing to disclose, Andrea Cortegiani has nothing to disclose, Maurizio Cecconi reports personal fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Directed Systems, Takeshi Unoki has nothing to disclose, Laurą Galarza has nothing to disclose, Regis Goulart Rosa has received research grants from the Brazilian Ministry of Health to conduct studies on the topic of ICU visiting policies, Francois Barbier reported consulting and lecture fees, conference invitation from MSD and lecture fees from BioMérieux, Elie Azoulay reports receiving fees for lectures from Gilead, Pfizer, Baxter, and Alexion. His research group has been supported by Ablynx, Fisher & Payckle, Jazz Pharma, and MSD, outside the submitted work, Kevin B Laupland has nothing to disclose, Nathalie Ssi Yan Kai has nothing to disclose, Marlies Ostermann has nothing to disclose, Guy Francois has nothing to disclose, Jan J De Waele reports grants from Research Foundation Flanders, during the conduct of the study; other from Pfizer, other from MSD, outside the submitted work, Kirsten Fiest has nothing to disclose, Peter Spronk has nothing to disclose, Julie Benbenishty has nothing to disclose, Mariangela Pellegrini has nothing to disclose, Louise Rose is a co-founder of Life Lines, a philanthropic COVID-19 rapid response project that received charitable donations to enable provision of 4G enabled Android tablets and a bespoke virtual visiting solution to ICUs across the UK. LR has no financial or commercial interests in Life Lines or the virtual visiting solution. Major philanthropic contributors to Life Lines include Google, True Colours and the Gatsby Trust. British Telecom contributed in-kind time and resources to facilitate the supply of 4G enabled tablets to UK ICUs.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following scientific societies for endorsing and distributing the survey to their members:

-

•

European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM)

-

•

Associazione Nazionale Infermieri di Area Critica (ANIARTI)

-

•

Società Italiana di Anestesia Analgesia Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva (SIAARTI)

-

•

Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias (SEMICYUC)

We thank the following scientific societies for distributing the survey to their members:

-

•

Croatian Society of Intensive Care Medicine

-

•

Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine

-

•

Belgian Society of Intensive Care Medicine

-

•

Canadian critical care society

-

•

Sociedade Portuguesa de Medicina Intensiva

-

•

The Swedish Society of Anesthesia and Intensive care (SFAI)

-

•

Intensive Care Society (United Kingdom)

-

•

Famirea (France)

-

•

Queensland Critical Care Research Network (QCCRN).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2022.154050.

Contributor Information

the COVISIT contributors:

Mahesh Ramanan, Rachel Bailey, Irmgard E. Kronberger, Anis Cerovac, Wendy Sligl, Jasminka Peršec, Eddy Lincango-Naranjo, Nermin Osman, Yousef Tanas, Yomna Dean, Ahmed Mohamed Abbas, Mohamed Gamal Elbahnasawy, Eslam Mohamed Elshennawy, Omar Elmandouh, Fatima Hamed Ahmed, Despoina Koulenti, Ioannis Tsakiridis, Mohan Gurjar, Marilaeta Cindryani, Ata Mahmoodpoor, Hogir Imad Rasheed Aldawoody, Francesco Zuccaro, Pasquale Iozzo, Mariachiara Ippolito, Yukiko Katayama, Tomoki Kuribara, Satoko Miyazaki, Asami Nakayama, Akira Ouchi, Hideaki Sakuramoto, Mitsuhiro Tamoto, Toru Yamada, Hashem Abdulaziz Abu Serhan, Saqr Ghaleb Ghassab Alsakarneh, Zhannur Kaligozhin, Dmitriy Viderman, Lina Karout, Mohd Shahnaz Hasan, Andee Dzulkarnaen Zakaria, Silvio A. Ñamendys-Silva, Lajpat Rai, Antonio Thaddeus R. Abello, Pedro Povoa, Dana Tomescu, Evgeniy Drozdov, Alberto Orejas Gallego, Ursula M. Jariod-Ferrer, Bernardo Nuñez-Garçia, Ahmed Mohamed Ibrahim Mohamed, Abram Raymon Moneer George, Marie-Madlen Jeitziner, Kemal Tolga Saracoglu, Arda Isik, Abdullah Tarik Aslan, and Tomasz Torlinski

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Queensland Government Chief Health Officer Public Health Directions. 2021. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/system-governance/legislation/cho-public-health-directions-under-expanded-public-health-act-powers; accessed 29/11/2021.

- 2.Fiest K.M., Krewulak K.D., Hiploylee C., Bagshaw S.M., Burns K.E.A., Cook D.J., et al. An environmental scan of visitation policies in Canadian intensive care units during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Anaesth. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-02049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mistraletti G., Giannini A., Gristina G., Malacarne P., Mazzon D., Cerutti E., et al. Why and how to open intensive care units to family visits during the pandemic. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03608-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulton A.J., Jordan H., Adams C.E., Polgarova P., Morris A.C., Arora N. Intensive care unit visiting and family communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: a UK survey. J Intens Care Soc. 2021;17511437211007779 doi: 10.1177/17511437211007779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phua J., Weng L., Ling L., Egi M., Lim C.M., Divatia J.V., et al. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):506–517. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valley T.S., Schutz A., Nagle M.T., Miles L.J., Lipman K., Ketcham S.W., et al. Changes to visitation policies and communication practices in Michigan ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(6):883–885. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1706LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azoulay É., Curtis J.R., Kentish-Barnes N. Ten reasons for focusing on the care we provide for family members of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(2):230–233. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06319-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kentish-Barnes N., Degos P., Viau C., Pochard F., Azoulay E. “It was a nightmare until I saw my wife”: the importance of family presence for patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(7):792–794. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azoulay E., Cariou A., Bruneel F., Demoule A., Kouatchet A., Reuter D., et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and Peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19. A cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(10):1388–1398. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2568OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose L., Yu L., Casey J., Cook A., Metaxa V., Pattison N., et al. Communication and virtual visiting for families of patients in intensive care during COVID-19: a UK National Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202012-1500OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma A., Minh Duc N.T., Luu Lam Thang T., Nam N.H., Ng S.J., Abbas K.S., et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS) J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(10):3179–3187. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06737-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UN Statistics Division Standard Country and Area Codes for Statistical Use. 2022. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/; accessed 29/11/2021.

- 13.Jensen H.I., Akerman E., Lind R., Alfheim H.B., Frivold G., Fridh I., et al. Conditions and strategies to meet the challenges imposed by the COVID-19-related visiting restrictions in the intensive care unit: a Scandinavian cross-sectional study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2022;68 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dos Santos S.S., Nassar Junior A.P. An outbreak of restrictive intensive care unit visiting policies. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;103140 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang S.Y., Sevransky J., Martin G.S. Protocols in the management of critical illness. Crit Care. 2012;16(2):306. doi: 10.1186/cc10578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos J., Westphal C., Fezer A.P., Moerschberger M.S., Westphal G.A. Effect of virtual information on the satisfaction for decision-making among family members of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06616-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azoulay E., Pochard F., Reignier J., Argaud L., Bruneel F., Courbon P., et al. Symptoms of mental health disorders in critical care physicians facing the second COVID-19 wave: a cross-sectional study. Chest. 2021;160(3):944–955. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg J.A., Basapur S., Quinn T.V., Bulger J.L., Schwartz N.H., Oh S.K., et al. Challenges faced by families of critically ill patients during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kandori K., Okada Y., Ishii W., Narumiya H., Maebayashi Y., Iizuka R. Association between visitation restriction during the COVID-19 pandemic and delirium incidence among emergency admission patients: a single-center retrospective observational cohort study in Japan. J Intensive Care. 2020;8(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00511-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bloomer M.J., Bouchoucha S. Australian College of Critical Care Nurses and Australasian College for infection prevention and control position statement on facilitating next-of-kin presence for patients dying from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the intensive care unit. Aust Crit Care. 2021;34(2):132–134. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruyneel A., Lucchini A., Hoogendoorn M. Impact of COVID-19 on nursing workload as measured with the nursing activities score in intensive care: summary of findings. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;103170 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiest K.M., Krewulak K.D., Hernández L.C., Jaworska N., Makuk K., Schalm E., et al. Evidence-informed consensus statements to guide COVID-19 patient visitation policies: results from a national stakeholder meeting. Can J Anesth. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12630-022-02235-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milner K.A., Marmo S., Goncalves S. Implementation and sustainment strategies for open visitation in the intensive care unit: a multicentre qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;102927 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey R.L., Ramanan M., Litton E., Yan Kai N.S., Coyer F.M., Garrouste-Orgeas M., et al. Staff perceptions of family access and visitation policies in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units: the WELCOME-ICU survey. Aust Crit Care. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material