Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) disease is a global epidemic caused by the pathogenic Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Tools that can track the replication status of viable Mtb cells within macrophages are vital for the elucidation of host-pathogen interactions. Here, we present a cephalosphorinase-dependent green trehalose (CDG-Tre) fluorogenic probe that enables fluorescence labeling of single live Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) cells within macrophages at concentrations as low as 2 μM. CDG-Tre fluoresces upon activation by BlaC, the β-lactamase uniquely expressed by Mtb, and the fluorescent product is subsequently incorporated within the bacterial cell wall via trehalose metabolic pathway. CDG-Tre showed high selectivity for mycobacteria over other clinically prevalent species in the Corynebacterineae suborder. The unique labeling strategy of BCG by CDG-Tre provides a versatile tool for tracking Mtb in both pre- and post-phagocytosis and elucidating fundamental physiological and pathological processes related to the mycomembrane.

Tuberculosis (TB) disease, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains the leading cause of mortality by a single pathogen.1 Upon inhalation of Mtb-containing droplets, Mtb cells invade host lung macrophages where they have evolved a variety of strategies to persist and replicate.2 In some cases, these Mtb cells will eventually induce host cell death and escape innate immune defenses.3–5 The ability to track Mtb metabolic status, cell growth and division, at the single-cell level, with high temporal and spatial resolution could greatly facilitate our understanding of the host-pathogen interactions and fuel innovations in both clinical detection and discovery of novel anti-TB therapeutic strategies.6,7

Several technologies have been reported for labeling and tracking phagocytosed Mtb, from genetic labeling with fluorescent reporter proteins,8,9 metabolic labeling with fluorophores conjugated to cell wall building blocks,10 to enzymatic labeling with small molecule fluorescent probes.11 Since its introduction, the genetic inheritance of fluorescent proteins has been favored in monitoring gene expression and tracking live organisms, including Mtb.12,13 Nonetheless, the long half-life of fluorescent proteins prevents real-time monitoring of cellular dynamic changes. As well, such genetic manipulation in mycobacteria may compromise cell virulence significantly.14–16 Genetic labeling has not yet been demonstrated to report on cell wall biosynthesis, a critical component for understanding Mtb pathogenesis and the development of effective antibiotics.17,18 Metabolic engineering for labeling the bacterial cell surface in macrophages19–22 includes the first use of fluorescent trehalose analogs, FITC-Tre,23 and recently, DMN-Tre.24,25 These trehalose derivatives are processed by antigen 85 (Ag85) enzymes, and incorporated into the mycolyl arabinogalactan (mAG) layer metabolically.26 Their generally poor membrane permeability and strict requirement of high working concentration (e.g. FITC-Tre, 200 μM; DMN-Tre, 100 μM), however, raised concerns in their potential toxicity in macrophages. Enzyme-activated fluorescent small molecule probes have shown great promise for sensitive Mtb detection.11 CDG-DNB3, for example, enabled rapid and specific labeling of single live Mtb by taking the advantage of two enzymes expressed by Mtb: β-lactamase C (BlaC) that activates the probe to restore fluorescence, and decaprenylphosphoryl-β-D-ribose 2’-epimerase (DprE1) that traps the fluorescent product via a covalent linkage.27 Unlike metabolic labeling, this probe is not incorporated into cell wall; however, its efficacy in labeling of post-phagocytosed Mtb remains to be demonstrated.

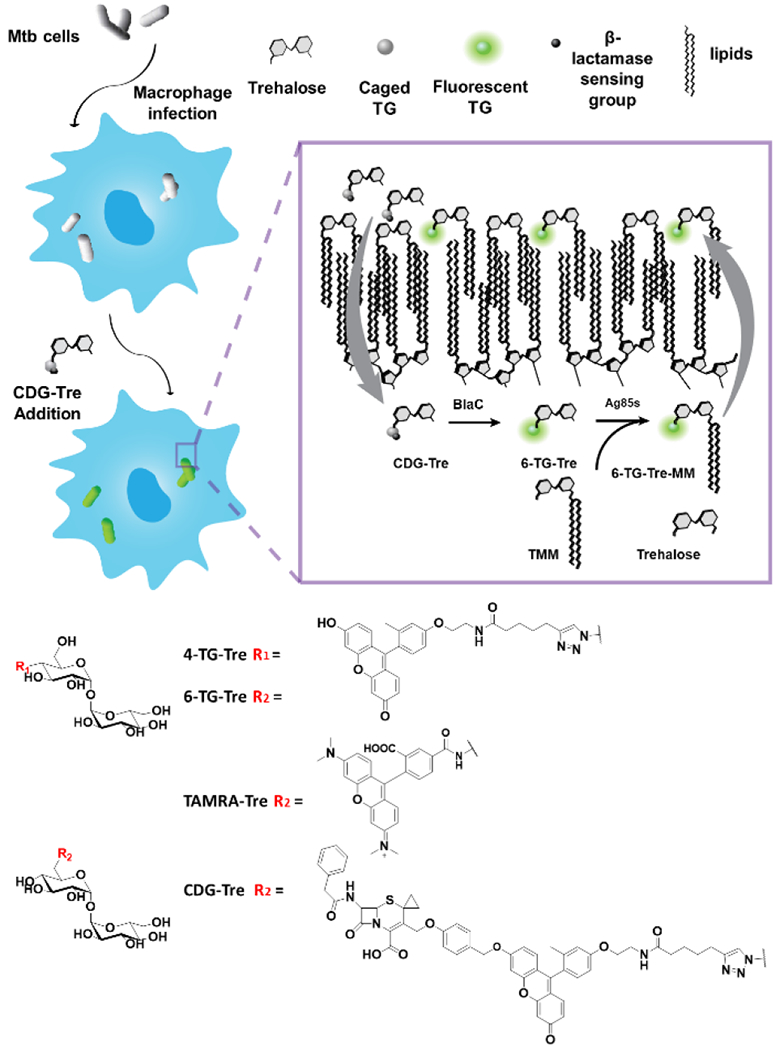

In this work, we developed a fluorogenic probe--a conjugate of cephalosporin and trehalose, named CDG-Tre--to improve the labeling of phagocytosed Mtb (Fig. 1). By employing a cephalosporin analog to cage 2-Me TokyoGreen (TG) fluorophore conjugated to trehalose, we envision that the lactam ring will be hydrolyzed by BlaC.28,29 In the presence of a leaving group at the 3’ position, the hydrolyzed product will proceed with spontaneous fragmentation, resulting in the release and fluorescence turn-on. Subsequently, the fluorescent trehalose fragment will be processed via the Ag85-mediated trehalose pathway, resulting in the metabolic labeling of the cell wall (Fig. 1). We characterized CDG-Tre in a series of experiments and demonstrated the BlaC/Ag85 dependent labeling mechanism. Importantly, we show efficient labeling of phagocytosed Mtb using very low concentrations of CDG-Tre (2 μM).

Figure 1.

Structures of fluorescent trehalose derivatives and the proposed labeling of Mtb phagocytosed within macrophages. CDG-Tre probes are taken up by macrophages into phagosomes, then reach the periplasmic layer of Mtb cells. [Inset] The probes are activated by BlaC and processed by Ag85 enzymes into 6-TG-Tre monomycolate (6-TG-Tre-MM) with a mycolate chain transferred from another molecule of trehalose monomycolate (TMM). 6-TG-Tre-MM was further incorporated into the outer leaflet of the capsule.

Different positions on the trehalose molecule have been decorated, resulting in varying efficacy for mycobacterial cell wall labeling.23 It has been shown that the Ag85 complex processes modifications at the trehalose 4- or 6-hydroxyl group position more efficiently.30 In this study, TG, a fluorescein derivative where the carboxylic group was replaced with a methyl group, was chosen as the fluorophore. This probe has great photostability and is highly fluorescent in its anionic form while the quantum yield is near zero when the hydroxy group is alkylated because the fluorescence is quenched via intramolecular photoinduced electron transfer (PeT).27,31 Therefore, we coupled TG with 6-heptynoic acid, followed by Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) with trehalose, to yield 4-TG-Tre and 6-TG-Tre analogs (Fig. S1).

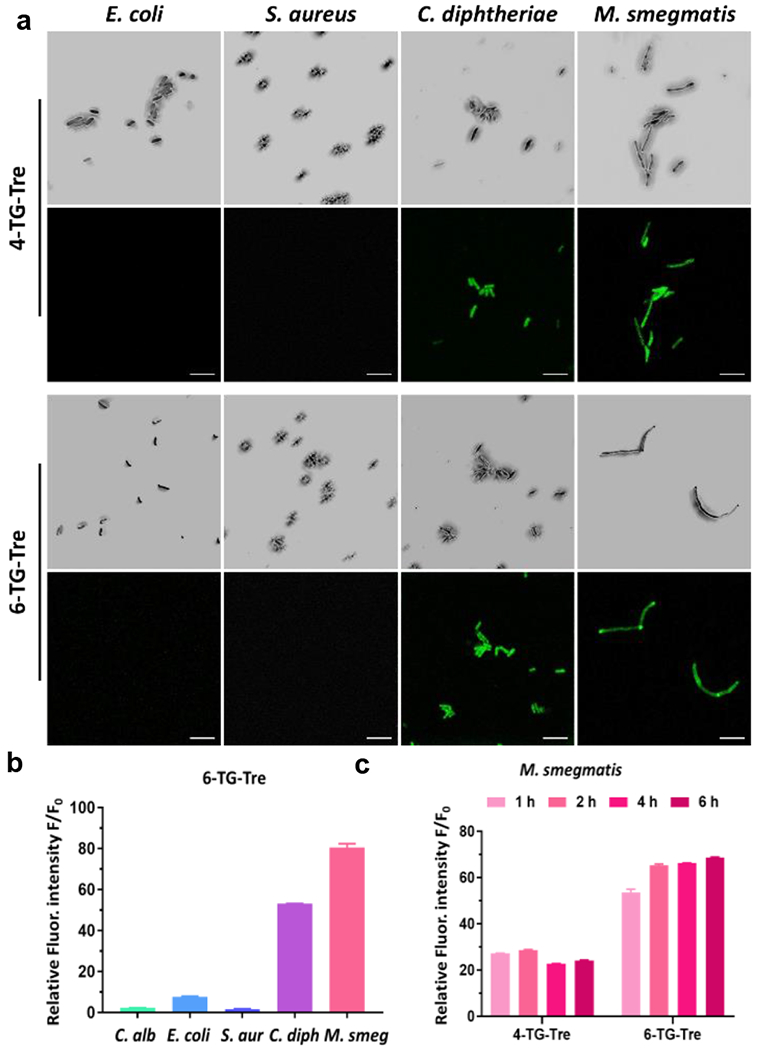

The uptake of 4-TG-Tre and 6-TG-Tre was evaluated in several representative species of bacteria and fungi including Candida albicans (C. albicans, the most prevalent cause of fungal infection in human32), Escherichia coli (E. coli, a commonly used gram-negative bacteria model), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, frequently found in the respiratory tract of patients with pulmonary diseases), Corynebacterium diphtheriae (C. diphtheriae) and Mycobacterium smegmatis (M. smegmatis). Corynebacterium commonly colonizes the skin and mucous membranes of human with C. diphtheriae as one of the most pathogenic species. M. smegmatis has been widely used as a laboratory model organism for Mtb studies due to the genetic similarity and its rapid growth compared to Mtb. Both C. diphtheriae and M. smegmatis belong to Actinobacteria phylum and carry the mAG layer. Following incubation with 50 μM of 4-TG-Tre or 6-TG-Tre at 37 °C for 2 h, C. diphtheriae and M. smegmatis exhibited strong green fluorescence labeling while little uptake was observed in C. albicans, E. coli, and S. aureus due to the lack of Ag85 enzymes and mAG structure (Figs. 2a & S3).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence analysis of different species of bacteria and fungi labeled with 4-TG-Tre or 6-TG-Tre. (a) Confocal images of freshly cultured E. coli (TOP10), S. aureus, C. diphtheriae and M. smegmatis stained with 50 μM of 4-TG-Tre and 6-TG-Tre in PBS for 2 h at 37 °C. For each set of images, the top row = bright field; bottom row = green fluorescence, 63x/oil, Ex-490 nm/Em-520 nm. Scale bars indicate 5 μm. (b-c) Green fluorescence activated flow cytometry analysis of (b) freshly cultured C. albicans, E. coli (TOP10), S. aureus, C. diphtheriae and M. smegmatis with 50 μM of 6-TG-Tre in PBS at 37 °C for 2h; or (c) M. smegmatis stained with 50 μM of 4-TG-Tre and 6-TG-Tre in PBS at 37 °C for 1, 2, 4, 6 h. The autofluorescence of unlabeled bacteria (F0) was utilized to normalize the intensity. N=3, error bars represent standard deviation.

We quantitated the mean fluorescence intensity of each labeled species by flow cytometry. Within 2 h, 6-TG-Tre treated M. smegmatis showed approximately 80-fold increase in fluorescent intensity over unlabeled bacteria in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Similarly, C. diphtheriae showed a 50-fold increase. For C. albicans, E. coli, and S. aureus, the fluorescence intensity was only 2-, 7- and 1-fold higher than the background, respectively (Fig. 2b). As illustrated in Fig. 2c, the labeling efficiency of 6-TG-Tre was higher than that of 4-TG-Tre. A longer incubation of M. smegmatis with 6-TG-Tre for 4 and 6 h barely improved the total uptake. To confirm Ag85 processing of 6-TG-Tre, we purified Mtb Ag85c (Fig. S4) and resorufin butyrate was used as an acyl donor in the assay as previously reported (Fig. S5 and S6).33 Mass spectrometry analysis confirmed the addition of butyrate on 6-TG-Tre by Ag85c. Collectively, these data suggested that 6-TG-Tre is a suitable candidate for the specific labeling of mycobacteria and corynebacteria.

Next, the cephalosporin scaffold was coupled with TG to generate CDG-Tre (Fig. S2). The fluorogenic property of CDG-Tre was evaluated with recombinant BlaC (Fig. S7). In the presence of BlaC, the fluorescence of CDG-Tre was rapidly turned on (within 20 minutes) and the hydrolyzed product 6-TG-Tre was confirmed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) (Fig. S8). We further tested if CDG-Tre could be processed by Ag85c as an acyl acceptor before the cleavage by BlaC. Surprisingly, unlike 6-TG-Tre, the product with butyrate addition was not found (Fig. S9). These data suggested that in order to be processed and incorporated by Ag85c, CDG-Tre must be first uncaged by BlaC.

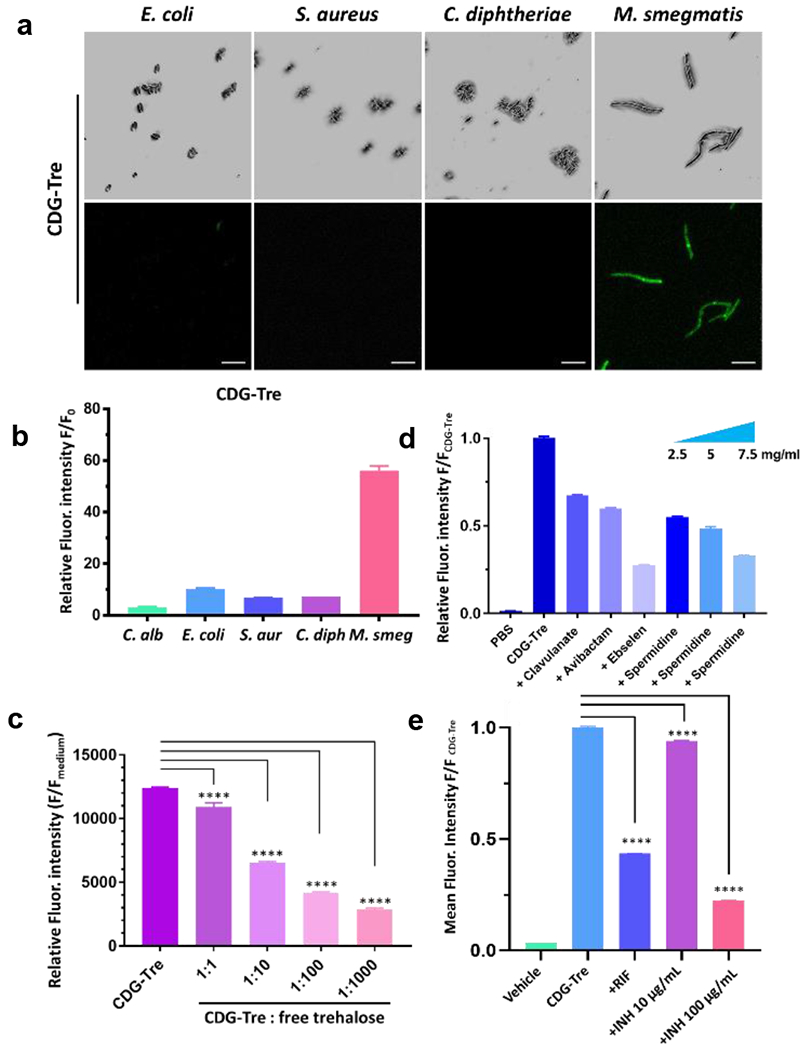

The capability of CDG-Tre in differentiating cephalosporin resistant mycobacteria was assessed in live bacteria and fungi. Unlike C. diphtheriae which is sensitive to β-lactam antibiotics and lacks the ability to activate CDG-Tre, M. smegmatis naturally expresses a β-lactamase called BlaS which could rapidly hydrolyze CDG-Tre and turn on fluorescence.28 As shown in Figs. 3a, 3b and S10, up to a 55-fold increase in fluorescence intensity was observed in M. smegmatis whereas the uptake by C. albicans, E. coli, S. aureus and C. diphtheriae was minimal. Inhibitors of Ag85 enzymes and BlaC were used to confirm the labeling mechanism of CDG-Tre. Both trehalose and ebselen (Ag85 inhibitors) inhibited the labeling of M. smegmatis by CDG-Tre (Fig. 3c & 3d). Two β-lactamase inhibitors, clavulanic acid and avibactam,34,35 reduced the fluorescence of labeled M. smegmatis by 33% and 40%, respectively (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, studies have reported that cephalosporin antibiotics could be taken up through porins.36,37 We pretreated M. smegmatis with spermidine, a polyamine compound known to interfere with the bacterial porin function.38 Dose-dependent inhibition in fluorescent labeling was observed, confirming the involvement of porins in the uptake of CDG-Tre (Fig. 3d). We also applied CDG-Tre for drug susceptibility test. In particular, we sought to visualize changes in cells when treated with front-line TB drugs, such as rifampicin (RIF), a transcriptional inhibitor that targets specifically the RNA polymerases of bacteria, and isoniazid (INH), a mycolic acid biosynthesis inhibitor.39As presented in Fig. 3e, M. smegmatis cells treated with RIF (0.2 μg/mL) or INH (10 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL) for 3 h exhibited a significantly reduced mean fluorescence intensity after CDG-Tre incubation. Together, these results have established the mechanism of the uptake, activation, and metabolic incorporation of CDG-Tre by mycobacteria.

Figure 3.

Characterization of CDG-Tre labeling. (a) Confocal images (top row = bright field and bottom row = green fluorescence, Ex-490 nm/Em-520 nm) of freshly cultured E. coli (TOP10), S. aureus, C. diphtheriae and M. smegmatis incubated with 50 μM of CDG-Tre in PBS at 37 °C for 2 h. Scale bars indicate 5 μm. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of bacteria and fungi shown in (a). The unlabeled bacterial autofluorescence in PBS (F0) was utilized to normalize and calculate the relative fluorescence intensity. (c) Inhibitory study with increasing concentrations of free trehalose at 1, 10, 100, 1000-fold over CDG-Tre (100 μM) with M. smegmatis. (d) Inhibitory study with clavulanate (2 mg/ml), avibactam (2 mg/ml), ebselen (200 μg/ml) and spermidine (2.5, 5, 7.5 mg/ml) in the presence of 50 μM CDG-Tre with M. smegmatis. M. smegmatis treated with CDG-Tre exhibited a 60-fold increase of mean fluorescence intensity over PBS, which was arbitrarily set as 1 to normalize the test samples and show percentage inhibition. (e) M. smegmatis was treated with rifampicin (RIF, 0.2 μg/mL) or isoniazid (INH, 10 μg/mL or 100 μg/mL) for 3 h before incubation with CDG-Tre (100 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C. Mean fluorescent intensity of CDG-Tre was arbitrarily set as 1 to normalize other samples with drugs treatment and show percentage inhibition. All error bars represent standard deviation of three independent measurements. ****=P<0.0001

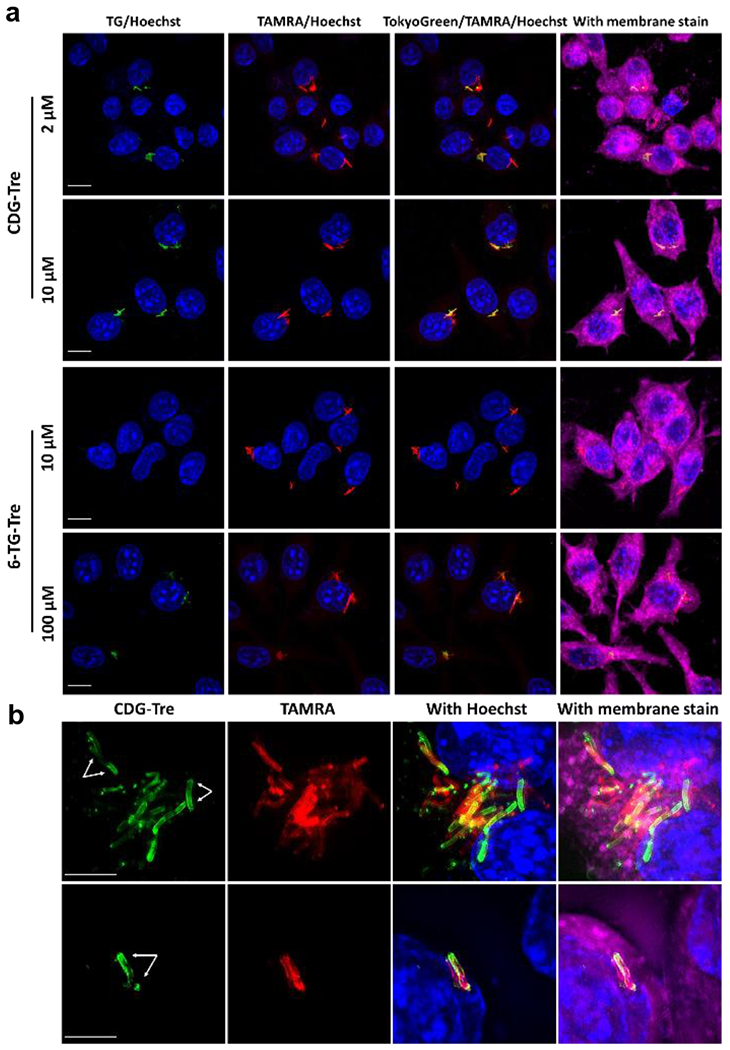

Lastly, we investigated whether CDG-Tre could label BCG cells phagocytosed within macrophages. Freshly cultured BCG were pre-labeled with TAMRA-Tre40 overnight then washed and incubated with mouse RAW macrophage at a ratio of multiplicities of infection (MOI) 10 to 1 in complete medium for 6 h. The macrophages were washed, then incubated with CDG-DNB3 (20 μM), 6-TG-Tre (20 μM) or CDG-Tre (20 μM) for 4 h in serum free medium (Fig. S11). CDG-DNB3 has been utilized for pre-labeling live BCG and tracking the process of phagocytosis in macrophages.27 Nonetheless, a post-labeling within 4 h generated significant non-specific green fluorescent background in macrophages. 6-TG-Tre presented clean background in macrophages, yet no probe uptake was observed in BCG. Considering the rapid uptake of 6-TG-Tre by mycobacteria alone (Fig. 2c), we hypothesized that the availability of 6-TG-Tre within live macrophages, especially in phagosomes, must be highly compromised. In CDG-Tre treated macrophages, green fluorescent BCG cells were observed (overlaying with the red fluorescence from TAMRA-Tre), in addition to green punctuates. When the incubation time of CDG-Tre increased to 22 h, followed by overnight culturing in complete medium, the fluorescence labeling intensity of phagocytosed live BCG was significantly enhanced, and the green punctuates disappeared to produce a very clean background. Staining of macrophages that had phagocytosed pre-killed BCG did not show any fluorescent labeling (Fig. S12).

For 6-TG-Tre, under the same conditions, some weak fluorescent labeling of phagocytosed live BCG could be observed when the probe concentration was over 100 μM (Fig. 4a). Both 6-TG-Tre and CDG-Tre displayed high stability in serum free medium at 37 °C (Fig. S13), and comparable toxicity to macrophages (Fig. S14). However, the required high labeling concentration of 6-TG-Tre (100 μM) made it toxic to macrophages. We performed super resolution structured illuminated microscopy (SR-SIM) analysis in an attempt to examine if CDG-Tre was incorporated into the bacterial cell walls. As shown in Fig. 4b, single BCG bacilli localized within macrophages presented bright green fluorescent cell wall structure. Interestingly, the green fluorescence from CDG-Tre staining did not completely overlay with the red fluorescence in BCG (from pre-labeling by TARMA-Tre). This fluorescence was preferentially localized to the polar regions of the bacilli in an asymmetric manner. In a previously proposed model, mycobacteria are believed to grow and elongate asymmetrically with new biosynthetic materials enriched in the poles.21 Therefore, CDG-Tre fluorescence is observed at poles where the newly biosynthesized cell wall membrane of live BCG is located. Taken together, these results demonstrate the advantages of CDG-Tre for labeling live BCG cells phagocytosed in macrophages.

Figure 4.

Imaging of live BCG cells within macrophage phagosomes with CDG-Tre. a) Freshly cultured BCG was pre-labeled with TAMRA-Tre (50 μM in PBS, red fluorescent) overnight then washed and incubated with macrophages at a 10-to-1 ratio in complete medium for 6 h. Macrophages were washed with HBSS three times, incubated with 6-TG-Tre or CDG-Tre in serum free medium at different concentrations for 22 h, then further incubated in complete medium overnight. b) Phagocytosed BCG cells were post-labeled by CDG-Tre (10 μM) and imaged with a superresolution structured illuminated microscope. Blue: Hoechst; Green: CDG-Tre or TG-Tre; Red: TAMRA; Deep Red: Membrane stain. White arrows point to the asymmetrical labeling of a single BCG. Scale bars indicate 10

The introduction of the cephalosporin molecule in CDG-Tre endows the probe the fluorogenic feature and a dual activation mechanism by both BlaC and Ag85 enzymes. Additionally, better performance of CDG-Tre (compared to TG-Tre) in labeling intracellular BCG cells in macrophages may be due to CDG-Tre enhanced uptake by macrophages into the phagosomes. We suspect the hydrophobic nature of the lactam unit may be contributing to this effect. Indeed, a recent study reported that lipid droplets in macrophages facilitated the transferring of bedaquiline, a lipophilic antibiotic, to intracellular Mtb.41 The hydrophobic lactam unit in CDG-Tre may promote its association with lipid droplets in macrophages, resulting in more efficient uptake and transferring to phagosomes for labeling of BCG (compared to more hydrophilic TG-Tre). Further investigation is required to confirm the underlying mechanism.

In summary, we report a new dual targeting fluorogenic probe CDG-Tre that can be sequentially activated by two target enzymes expressed in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: BlaC and Ag85s. We investigated the mechanism of the uptake, activation, and metabolic incorporation of CDG-Tre by mycobacteria and demonstrated the advantages of CDG-Tre over previous methods. CDG-Tre was shown to report changes on bacteria viability 3 h following drug treatment, while genetic labeled bacteria cells usually require longer incubation time to reflect the changes (24 h for M. smegmatis and 5 d for Mtb).42 In compared to other trehalose fluorescent probes that are generally poor cell permeable and work at high concentrations (typically at 100-200 μM), CDG-Tre enabled high contrast imaging at a low working concentration that displayed low toxicity to the macrophages in labeling phagocytosed BCG cells within macrophages. The post-phagocytosis labeling by CDG-Tre may provide a new approach to tracking the kinetics of a single Mtb cell within macrophages and probe their interactions with high temporal and spatial resolution.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility (CSIF) for help on SR-SIM, Stanford Neuroscience Microscopy Service (supported by NIH NS069375) for help on confocal imaging, Stanford Shared FACS Facility for instrumentation and assistance with flow cytometry, and Vincent Coates Foundation Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Stanford University Mass Spectrometry for support on mass spectrometry analysis. This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI125286. T.D. thanks the support from the Center for Molecular Analysis and Design (CMAD) at Stanford.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental methods, supporting figures, and chemical characterizations (HRMS, 1H and 13C NMR spectra). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).World Health Organization (WHO), “Global tuberculosis report 2019” (WHO Press, 2019) [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ehrt S; Schnappinger D Mycobacterial survival strategies in the phagosome: defence against host stresses. Cell. Microbiol 2009, 11 (8), 1170–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mahamed D; Boulle M; Ganga Y; Mc Arthur C; Skroch S; Oom L; Catinas O; Pillay K; Naicker M; Rampersad S; Mathonsi C; Hunter J; Wong EB; Suleman M; Sreejit G; Pym AS; Lustig G; Sigal A Intracellular growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis after macrophage cell death leads to serial killing of host cells. eLife 2017, 6, e22028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Simeone R; Bobard A; Lippmann J; Bitter W; Majlessi L; Brosch R; Enninga J Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8 (2), e1002507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lerner TR; Borel S; Greenwood DJ; Repnik U; Russell MRG; Herbst S; Jones ML; Collinson LM; Griffiths G; Gutierrez MG Mycobacterium tuberculosis replicates within necrotic human macrophages. J. Cell Biol 2017, 216 (3), 583–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zheng X; Av-Gay Y System for efficacy and cytotoxicity screening of inhibitors targeting intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2017, No. 122, 55273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Stanley SA; Barczak AK; Silvis MR; Luo SS; Sogi K; Vokes M; Bray M-A; Carpenter AE; Moore CB; Siddiqi N; Rubin EJ; Hung DT Identification of host-targeted small molecules that restrict intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10 (2), e1003946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Chalfie M; Tu Y; Euskirchen G; Ward WW; Prasher DC Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science 1994, 263 (5148), 802–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ghim C-M; Lee S-K; Takayama S; Mitchell RJ The art of reporter proteins in science: past, present and future applications. BMB Rep. 2010, 43 (7), 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Siegrist MS; Swarts BM; Fox DM; Lim SA; Bertozzi CR Illumination of growth, division and secretion by metabolic labeling of the bacterial cell surface. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2015, 39 (2), 184–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Chyan W; Raines RT Enzyme-activated fluorogenic probes for live-cell and in vivo imaging. ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13 (7), 1810–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kong Y; Yang D; Cirillo SLG; Li S; Akin A; Francis KP; Maloney T; Cirillo JD Application of fluorescent protein expressing strains to evaluation of anti-tuberculosis therapeutic efficacy in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2016, 11 (3), e0149972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).MacGilvary NJ; Tan S Fluorescent Mycobacterium tuberculosis reporters: illuminating host–pathogen interactions. Pathog. Dis 2018, 76 (3), fty017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mutoji KN; Ennis DG Expression of common fluorescent reporters may modulate virulence for Mycobacterium marinum: dramatic attenuation results from GFP over-expression. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol 2012, 155 (1), 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Rang C; Galen JE; Kaper JB; Chao L Fitness cost of the green fluorescent protein in gastrointestinal bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol 2003, 49 (9), 531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Allison DG; Sattenstall MA The influence of green fluorescent protein incorporation on bacterial physiology: a note of caution. J. Appl. Microbiol 2007, 103 (2), 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Brennan PJ; Crick DC The cell-wall core of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the context of drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 2007, 7 (5), 475–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Seiler P; Ulrichs T; Bandermann S; Pradl L; Jörg S; Krenn V; Morawietz L; Kaufmann SHE; Aichele P Cell-wall alterations as an attribute of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in latent infection. J. Infect. Dis 2003, 188 (9), 1326–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Swarts BM; Holsclaw CM; Jewett JC; Alber M; Fox DM; Siegrist MS; Leary JA; Kalscheuer R; Bertozzi CR Probing the mycobacterial trehalome with bioorthogonal chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (39), 16123–16126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Foley HN; Stewart JA; Kavunja HW; Rundell SR; Swarts BM Bioorthogonal chemical reporters for selective in situ probing of mycomembrane components in mycobacteria. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55 (6), 2053–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hodges HL; Brown RA; Crooks JA; Weibel DB; Kiessling LL Imaging mycobacterial growth and division with a fluorogenic probe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2018, 115 (20), 5271–5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yang D; Ding F; Mitachi K; Kurosu M; Lee RE; Kong Y A Fluorescent probe for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis and identifying genes critical for cell entry. Front. Microbiol 2016, 7, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Backus KM; Boshoff HI; Barry CS; Boutureira O; Patel MK; D’Hooge F; Lee SS; Via LE; Tahlan K; Barry CE; Davis BG Uptake of unnatural trehalose analogs as a reporter for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Chem. Biol 2011, 7 (4), 228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Sahile HA; Rens C; Shapira T; Andersen RJ; Av-Gay Y DMN-Tre labeling for detection and high-content screening of compounds against Iintracellular mycobacteria. ACS Omega 2020, 3661–3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kamariza M; Shieh P; Ealand CS; Peters JS; Chu B; Rodriguez-Rivera FP; Sait MRB; Treuren WV; Martinson N; Kalscheuer R; Kana BD; Bertozzi CR Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum with a solvatochromic trehalose probe. Sci. Transl. Med 2018, 10 (430), eaam6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Belisle JT; Vissa VD; Sievert T; Takayama K; Brennan PJ; Besra GS Role of the major antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cell wall biogenesis. Science 1997, 276 (5317), 1420–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cheng Y; Xie J; Lee K-H; Gaur RL; Song A; Dai T; Ren H; Wu J; Sun Z; Banaei N; Akin D; Rao J Rapid and specific labeling of single live Mycobacterium tuberculosis with a dual-targeting fluorogenic probe. Sci. Transl. Med 2018, 10 (454), eaar4470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Flores AR; Parsons LM; Pavelka. Genetic analysis of the β-lactamases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis and susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics. Microbiology , 2005, 151 (2), 521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kurz SG; Wolff KA; Hujer AM; Nguyen L; Bonomo RA Sequence analysis of the beta-lactamase gene BlaC in clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals a conserved therapeutic target. In B59. Advances in treating tuberculosis; American Thoracic Society International Conference Abstracts; American Thoracic Society, 2013; pp A3182–A3182. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Rodriguez-Rivera FP; Zhou X; Theriot JA; Bertozzi CR Visualization of mycobacterial membrane dynamics in live cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (9), 3488–3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Urano Y; Kamiya M; Kanda K; Ueno T; Hirose K; Nagano T Evolution of fluorescein as a platform for finely tunable fluorescence probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (13), 4888–4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Richards MJ; Edwards JR; Culver DH; Gaynes RP; System NNIS Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol 2000, 21 (8), 510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Favrot L; Grzegorzewicz AE; Lajiness DH; Marvin RK; Boucau J; Isailovic D; Jackson M; Ronning DR Mechanism of inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85 by ebselen. Nat. Commun 2013, 4, 2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Reading C; Cole M Clavulanic Acid: A beta-lactamase-inhibiting beta-lactam from Streptomyces clavuligerus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 1977, 11 (5), 852–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ehmann DE; Jahić H; Ross PL; Gu R-F; Hu J; Kern G; Walkup GK; Fisher SL Avibactam is a covalent, reversible, non–β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109 (29), 11663–11668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Nikaido H; Jarlier V Permeability of the mycobacterial cell wall. Res. Microbiol 1991, 142 (4), 437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Nestorovich EM; Danelon C; Winterhalter M; Bezrukov SM Designed to penetrate: time-resolved interaction of single antibiotic molecules with bacterial pores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A 2002, 99 (15), 9789–9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Sarathy JP; Lee E; Dartois V Polyamines inhibit porin-mediated fluoroquinolone uptake in mycobacteria. PLoS One 2013, 8 (6), e65806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zumla A; Nahid P; Cole ST Advances in the development of new tuberculosis drugs and treatment regimens. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2013, 12 (5), 388–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Rodriguez-Rivera FP; Zhou X; Theriot JA; Bertozzi CR Acute modulation of mycobacterial cell envelope biogenesis by front-line TB drugs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57 (19), 5267–5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Greenwood DJ; Santos MSD; Huang S; Russell MRG; Collinson LM; MacRae JI; West A; Jiang H; Gutierrez MG Subcellular antibiotic visualization reveals a dynamic drug reservoir in infected macrophages. Science 2019, 364 (6447), 1279–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Smith TC; Pullen KM; Olson MC; McNellis ME; Richardson I; Hu S; Larkins-Ford J; Wang X; Freundlich JS; Ando DM; Aldridge BB Morphological profiling of tubercle bacilli identifies drug pathways of action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2020, 117 (31), 18744–18753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.