Abstract

Objective:

We evaluated an alternative administration route, reduced schedule priming series, and increased intervals between booster doses for anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA). AVA’s originally licensed schedule was 6 subcutaneous (SQ) priming injections administered at months (m) 0, 0.5, 1, 6, 12 and 18 with annual boosters; a simpler schedule is desired.

Methods:

Through a multicenter randomized, double blind, non-inferiority Phase IV human clinical trial, the originally licensed schedule was compared to four alternative and two placebo schedules. 8-SQ group participants received 6 SQ injections with m30 and m42 “annual” boosters; participants in the 8-IM group received intramuscular (IM) injections according to the same schedule. Reduced schedule groups (7-IM, 5-IM, 4-IM) received IM injections at m0, m1, m6; at least one of the m0.5, m12, m18, m30 vaccine doses were replaced with saline. All reduced schedule groups received a m42 booster. Post-injection blood draws were taken two to four weeks following injection. Non-inferiority of the alternative schedules was compared to the 8-SQ group at m2, m7, and m43. Reactogenicity outcomes were proportions of injection site and systemic adverse events (AEs).

Results:

The 8-IM group’s m2 response was non-inferior to the 8-SQ group for the three primary endpoints of anti-protective antigen IgG geometric mean concentration (GMC), geometric mean titer, and proportion of responders with a 4-fold rise in titer. At m7 anti-PA IgG GMCs for the three reduced dosage groups were non-inferior to the 8-SQ group GMCs. At m43, 8-IM, 5-IM, and 4-IM group GMCs were superior to the 8-SQ group. Solicited injection site AEs occurred at lower proportions in the IM group compared to SQ. Route of administration did not influence the occurrence of systemic AEs. A 3 dose IM priming schedule with doses administered at m0, m1, and m6 elicited long term immunological responses and robust immunological memory that was efficiently stimulated by a single booster vaccination at 42 months.

Conclusions:

A priming series of 3 intramuscular doses administered at m0, m1, and m6 with a triennial booster was non-inferior to more complex schedules for achieving antibody response.

Keywords: Anthrax vaccines, Bacillus anthracis, Bacterial vaccines, Vaccination, Adverse events

1. Introduction

The U.S. licensed vaccine, anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA) (BioThrax®, Emergent BioSolutions Inc., Lansing, MI), is prepared from a cell-free culture filtrate which contains a mixture of proteins, including the principal immunogen protective antigen (PA), adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (Alhydrogel, Brenntag Group, Denmark) as an adjuvant. AVA was originally licensed in 1970 [1,2] as a series of 0.5 mL injections administered subcutaneously in the upper outer arm, over the deltoid muscle, at months 0, 0.5, 1, 6, 12, and 18, followed by annual boosters. Evidence for the efficacy of AVA comes from several studies in animals, a controlled vaccine trial in humans using a similar product, observational data in humans, and immunogenicity data for humans and other mammals [3-14].

Due in part to increased vaccination of military personnel beginning in 1997 [15], the US Congress tasked the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to expand upon the Department of Defense (DoD) pilot studies of dose and schedule optimization [16,17] by undertaking the largest ever prospective study of AVA safety and immunogenicity in a diverse study population. The primary focus of the CDC Anthrax Vaccine Research Program (AVRP) was a 43-month prospective, randomized, double-blind, phase IV, placebo controlled clinical trial. The objectives of the AVRP were to document and ensure the safety and immunogenicity of AVA, and subsequently to minimize the priming dose series and optimize the booster schedule [18]. An interim analysis of safety and immunogenicity data generated on 1005 study participants through the first 7 months of their participation [19] provided the basis in 2008 for FDA to support a change to IM administration and elimination of the week 2 (m0.5) dose in the priming series [20]. We present a final study analysis of data collected from 1563 participants through all 43 months of participation.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and recruitment

The study was sponsored by CDC under an Investigational New Drug (IND) application, was approved by the human investigations committees at participating clinical sites and at CDC, and was conducted according to the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practices (GCP). Study centers included Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX; Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN and University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL. Oversight was provided by a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB).

Volunteers had to be no less than 18 years and no greater than 61 years of age at the time of enrollment. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria, methods for randomization and blinding, as well as sample size calculations, are presented as supplemental material. The number of enrollees required by sample size calculations was doubled to allow for attrition due to the length of the study.

2.2. Interventions

AVA was provided by the Military Vaccine (MilVax) Agency, DoD, through the United States Army Medical Materiel Agency (USAMMA). Over the study duration 6 lots of vaccine were used: FAV063, FAV074, FAV079, FAV087, FAV107, and FAV113. Placebo injections were saline (0.9% (w/v) NaCl, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL).

Participants were randomized to one of 6 study groups. One group (8-SQ) received AVA as originally licensed, or 6 SQ injections of AVA administered at months 0, 0.5, 1, 6, 12, and 18, followed by 2 annual boosters administered at months 30 and 42. A second group (8-IM) received AVA administered intramuscularly (IM) on the same schedule as the 8-SQ group. Three groups received AVA on reduced dose schedules (7-IM, 5-IM, 4-IM). These reduced dose schedule groups all received AVA at m0, m1, and m6, with one or more of the doses at m0.5, m12, m18 and/or m30 replaced with saline injection. All reduced dosage group participants received a booster at m42 (Table 1). The final group was administered saline placebo at all 8 times points, with participants equally divided between SQ and IM route of administration (Fig. 1 and Table 1). All vaccine and placebo injections were administered as a 0.5 mL dose.

Table 1.

Anthrax clinical trial: schedule of injections.

| Study group | Number of participants at enrollment |

Number of AVA doses |

Route | Month 0 | Month 0.5 | Month 1 | Month 6 | Month 12 | Month 18 | Month 30 (booster) |

Month 42 (booster) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-SQ | 259 | 8 | SQ | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA |

| 8-IM | 262 | 8 | IM | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA |

| 7-IM | 256 | 7 | IM | AVA | S | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA | AVA |

| 5-IM | 258 | 5 | IM | AVA | S | AVA | AVA | S | AVA | S | AVA |

| 4-IM | 268 | 4 | IM | AVA | S | AVA | AVA | S | S | S | AVA |

| Placebo IM | 127 | 0 | IM | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Placebo SQ | 133 | 0 | SQ | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

SQ, subcutaneous route; IM, intramuscular route; AVA, anthrax vaccine adsorbed; S, saline placebo. Blood drawn during injection visit was taken prior to injection and served as pre-injection sample; post injection samples were drawn 4 weeks following injection. All injections were administered as a 0.5 mL dose.

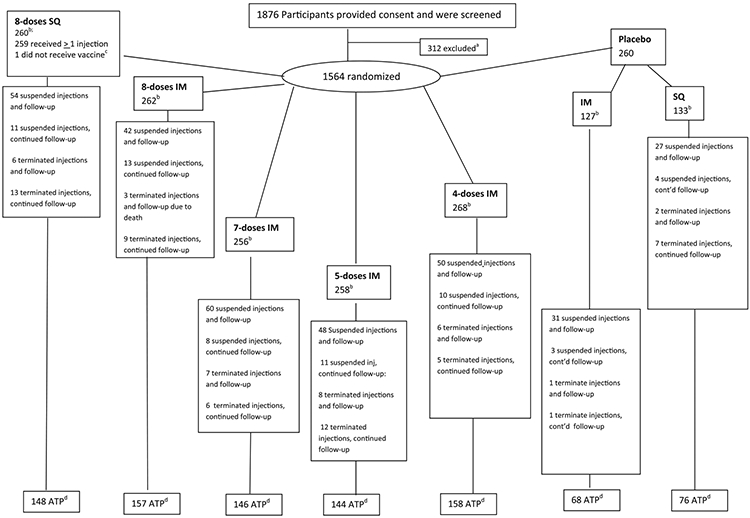

Fig. 1. Participant flow for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Anthrax Vaccine Research Program human clinical trial.

a Indicates that reasons for exclusion included abnormal electrocardiogram results, allergy to aluminum, autoimmune disorder, chronic condition or disease, compromised injection site, current or planned pregnancy, genetic disorder, history of anthrax vaccine adsorbed injections, history of or current cancer, mental illness, military commitment, neurologic condition, ongoing immune suppression therapy, planned surgery poor venous access, security risk, and substance abuse.

b number of participants per group following randomization

c one participant consented and was randomized, but withdrew from study prior to first injection

d number of participants in the According to Protocol (ATP) cohort at month 43

‘Terminated injections” means that no more injections were received by participant. “Suspended injections” means that the participant withdrew from receiving injections at one point during the study, only to either resume injections or be terminated at a later date. “Terminated follow-up” means the participant was no longer followed with blood draws or for adverse event data, while “Continued follow-up” indicates a participant continued to communicate with the study site, either for continued blood draws or adverse event follow-up.

Exact reasons for suspension or termination are included in the Supplemental Materials

IM = intramuscular, SQ= subcutaneous

2.3. Serological evaluation

Participant immune response profiles were determined for 13 serial pre- and post-injection blood samples.4 Samples were assayed for anti-PA IgG by ELISA and reported as titers and concentration in μg/ml [21-24]. Dilutional titers were calculated on a continuous scale and reported as the reciprocal of dilution [25]. The ELISA lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 3.7 μg/ml for concentrations of anti-PA IgG and 58 for titers. All reported values were from a minimum of two independent tests. The three primary endpoints based on the magnitude of anti-PA IgG antibody response were: (1) the proportion of participants achieving a ≥4-fold rise in anti-PA specific IgG titer compared to pre-injection titer (%4XR), (2) the geometric mean anti-PA specific IgG titer (GMT), and (3) the geometric mean concentration (GMC). To calculate geometric mean concentrations and titers, IgG concentrations and titers below the LLOQ [26] were set to ½ LLOQ, or 1.85 μg/ml and 1/29 respectively; 4-fold responses for participants < LLOQ were defined at 4 times the LLOQ. This is in contrast to the interim analysis in which ½ LLOQ was used [19].

Lethal toxin (LTx) neutralization activity (TNA) was determined for a subset of enrollees. A secondary endpoint, the TNA geometric mean titer (ED50 GMT), was calculated as the reciprocal of the serum dilution which neutralized 50% of in vitro LTx cytotoxicity [27-31]; TNA samples were run in triplicate. The LLOQ for the TNA assay was an ED50 titer of 36; TNA ED50 titers below the LLOQ were set to ½ LLOQ titer, or 18.

2.4. Safety evaluation

An adverse event (AE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence, regardless of causal relationship to vaccination. Solicited injection site and systemic AEs were predefined based on data from previous AVA studies [16]. Solicited reactogenicity endpoints included injection site adverse events (warmth, tenderness, itching, pain, arm motion limitation, erythema, induration, edema, nodule formation, and bruise) as well as systemic adverse events (fatigue, muscle ache, headache, fever, axillary adenopathy).

Solicited and unsolicited AE data were collected during scheduled in-clinic examinations, self-reported using AE diaries, or spontaneously reported at any time during the study and through follow-up by telephone of participants who did not return for scheduled visits. AEs were scored by participants as mild (no interference with routine activities, or temperature < 102.3 °F), moderate (interfered with routine activities, or temperature between 102.3 and 104 °F), or severe (incapacitating, or temperature <104°F). Serious adverse events (SAEs) were classified according to US regulations [32] as those resulting in: death, a life-threatening event, initial inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization, significant or persistent disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly/birth defect, and a medical event that required medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes. While remaining blinded to the participant’s study status, the DSMB Medical Monitor and site PI assessed the causal relationship using the World Health Organization causality assessment criteria [33].

2.5. Statistical methods

All immunogenicity analyses were conducted using the according-to-protocol (ATP) population which consisted of participants who: received all injections through that time point in the windows defined by the protocol, received the correct agent administered via the correct route, and received the correct injection volume (≥0.3 ml). A one-sided non-inferiority hypothesis was applied in this study. Serologic non-inferiority was assessed at the critical study time points of months 2, 7, and 43. These time points specifically evaluate the onset (m2) and completion (m7) of immunological priming, and the establishment of long term immunological memory (m43), in response to injections up to months 1, 6, and 42, respectively.

For the GMC and GMT outcomes, the criterion was the ratio of GMC and GMT of the originally licensed 8-SQ reference group to the 8-IM and reduced dosage groups. For the %4XR outcome, the criterion was the difference between the proportion of four-fold responders between the 8-SQ reference group and the 8-IM and reduced dosage groups. If the upper 97.5% confidence bound for a comparison was less than the non-inferiority margin, then the test group was judged to be non-inferior to the reference group. Non-inferiority margins of 1.5 and 0.10 were used for comparing the ratios of the geometric means and differences in fold-response, respectively. These values were derived from the FDA and ICH guidelines and literature precedent [34-36]. There was no expectation that non-inferiority would be achieved following placebo injection in reduced dose schedules. Due to equivalent schedules, serologic results for study groups 7-IM, 5-IM, and 4-IM were combined for immunogenicity analysis for assay data resulting from injections through month 6 and referred to as the “combined reduced priming series group” (Table 1).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were constructed to analyze log transformed antibody data. Models accounted for the longitudinal nature of the data and included adjustments for study site, age group, sex, race, and significant interactions. Analyses of proportion fold-responses were stratified by the time points and compared using χ2 statistics. Demographic distributions were calculated for 3 time points (months 0, 7 and 43) and also compared using χ2 statistics. Non-inferiority calculations stratified by sex were performed only for the three primary endpoints.

All reactogenicity analyses were conducted on the safety population, which consisted of participants who received at least one injection of the correct agent administered by the assigned route. Reactogenicity end points were injection site and systemic AEs. The incidence of AEs was computed after each dose and analyzed as dichotomous (yes/no); pain upon injection was analyzed as an ordinal endpoint. All hypothesis testing was performed using a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05. The presented analysis combined data from all groups receiving AVA via the IM route (8-IM, 7-IM, 5-IM < 4-IM) into a single IM group, dropping from the analysis any placebo injections in the reduced dosage groups. Analysis of in-clinic examination data is presented here; analyses of the AE summary data are presented in the supplemental material, along with the methodology for safety data collection.

Analyses of AEs focused on differences in the occurrence of AEs between the IM versus SQ groups, and females versus males. Logistic regression models using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were used to estimate the odds-ratios (OR) for the local and systemic AEs. Odds-ratios for the AE pain upon injection were estimated using a multinomial GEE model. Factors considered in all models were study site, study group, sex, race, age, time, and interactions of treatment group by sex and race. Time was a continuous variable defined as the number of days between dose 1 and subsequent doses. Study site, study group, sex, and race remained in the models regardless of significance. Other non-significant factors and interactions were removed in a stepwise fashion. All AEs were assessed and included in the analysis; however, this study was not designed to evaluate possible associations between AVA and rare SAEs.

Missing data were considered to be missing at random and were not imputed. All analyses were conducted using the SAS software system, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Participant flow, recruitment and demographics

Study participation was from May 15, 2002 (first enrollment) to November 28, 2007 (last blood draw). A total of 1876 participants provided consent and were screened. Of these, 312 were excluded from enrollment, with the remaining 1564 participants randomized into 6 study groups (Fig. 1 and Table 1); one person withdrew from the study following enrollment and randomization, but prior to first vaccination, leaving 1563 participants. Of the 1563 original participants, 897 (57.4%) retained ATP status and were included in this final analysis. Less than 3.3% of the ATP data set was missing at any time point.

The mean age at enrollment was 39 years. The proportion of participants (% of total) at enrollment in each of four age groups was similar for age categories of <30 years (n = 439, 28.1%) and 40–49 years (n = 460, 29.4%), but was lower for the 30–39 years (n = 361, 23.1%) and 50–61 years categories (n = 303, 19.4). The proportion of participants in each age category differed across treatment groups at the beginning of the study (p = 0.01) but was not statistically different at m75 (p-value = 0.08) or m435 (p = 0.39). The proportion of males/females at enrollment was nearly equal, with 48.8% of the study population male. This proportion did not differ significantly across treatment groups at enrollment (p = 0.99), m75 (p = 0.99), or m432 (p-value = 0.92). At enrollment, overall race distribution was 74.2% White (n = 1159), 20.7% Black (n = 324), and 5.1% Other (n = 80). The distributions of the 3 race categories were consistent and did not differ across treatment groups at enrollment (p = 0.54), m75 (p = 0.66), or m435 (p = 0.37) across the 3 time points. Less than 5% of the study population was Hispanic (n = 70; 4.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics for 1563 participants in the CDC Anthrax Vaccine Research Program human clinical triala.

| Groupb | Overall | Femalec | Malec | Age (years)d |

Racee |

Ethnicitye |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–61 | White | Black | Other | Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | ||||

| 8SQ | 259 | 134 | 125 | 77 | 42 | 91 | 49 | 199 | 47 | 13 | 246 | 13 |

| 8IM | 262 | 135 | 127 | 63 | 57 | 87 | 55 | 197 | 48 | 17 | 250 | 12 |

| 7IM | 256 | 132 | 124 | 75 | 77 | 54 | 50 | 194 | 49 | 13 | 247 | 9 |

| 5IM | 258 | 131 | 127 | 77 | 65 | 64 | 52 | 183 | 62 | 13 | 243 | 15 |

| 4IM | 268 | 136 | 132 | 72 | 60 | 91 | 45 | 201 | 59 | 8 | 256 | 12 |

| Placebo | 260 | |||||||||||

| Pl – IM | 127 | 64 | 63 | 35 | 29 | 35 | 28 | 90 | 28 | 9 | 122 | 5 |

| Pl – SQ | 133 | 68 | 65 | 40 | 31 | 38 | 24 | 95 | 31 | 7 | 129 | 4 |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; SQ, subcutaneous; IM, intramuscular; Pl, placebo.

Mean study group size was 261 (range 260–268).

Groups 7IM through 4IM were combined for some analyses.

Proportions of men (n = 763, 48.8%) to women (n = 800, 51.2%) were not statistically different across treatment groups or time points.

Mean age was 39 years.

Race/ethnicity categories were defined per 2000 census specifications, which allowed people to select more than one racial category. To simplify the analysis, we resolved multi-race selections to the pre-2000 discrete categories using methodologies described in NCHS’s Vital and Health Statistics document, series 2, number 135: ‘United States Census 2000 Population with Bridged Race Categories’.

3.2. Serological evaluation

As previously noted, 4-fold responses for participants <LLOQ were defined at 4 times the LLOQ; this is in contrast to the interim analysis in which ½ LLOQ was used. One direct result of this is that %4RX values reported for months 1, 2, 6, and 7 will be lower than those reported in 2008 [19].

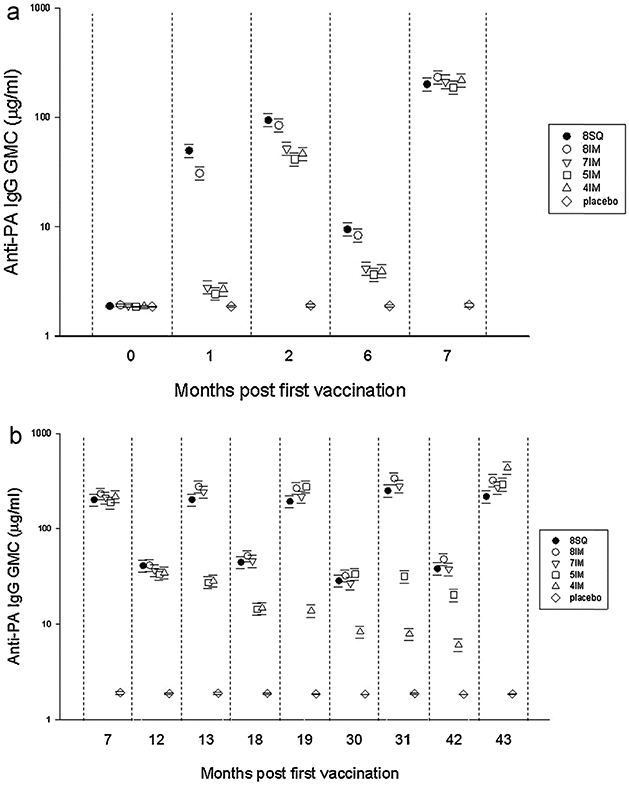

At m2, in response to the injections administered at m0, m0.5 and m1, the 8-IM group was non-inferior to 8-SQ for all 3 anti-PA specific IgG primary endpoints and the TNA ED50 GMT, while the combined reduced priming series group was not non-inferior for any of the endpoints (Table 3 and Fig. 2). At m7, in response to the m6 injection, the 8-IM and the combined reduced priming series group were non-inferior to 8-SQ for all anti-PA IgG and TNA ED50 endpoints (Table 3). At m43, all 4 treatment arms were non-inferior to 8-SQ for all anti-PA IgG and TNA ED50 primary and secondary endpoints; the 8-IM, 5-IM and 4-IM groups produced statistically superior responses for 2 of the 3 primary endpoints (Table 3).

Table 3.

Vaccination regimens, serum anti-PA IgG antibody responses and TNA ED50 GMT by study group, according to treatment population (ATP)a,b.

| Group (n = 1563) | Month 1 |

Month 2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-PA IgG GMC (μ/ml) |

Anti-PA IgG GMT (μ/ml) |

4-Fold response in Anti-PA IgG titer Response % |

TNA ED50 Titer GMT (unadjusted) |

Anti-PA IgG GMC (μ/ml) |

Anti-PA IgG GMT (μ/ml) |

4-Fold response in Anti-PA IgG titer Response % |

TNA ED50 Titer GMT (unadjusted) |

|

| 8 SQ | 49.7 | 565.2 | 81 | 100.4 | 94.3 | 1048.5 | 94.9 | 229.1 |

| (43.3, 57.1) | (492.6, 648.5) | (75.5, 85.7) | (77.9, 129.4) | (82.1, 108.3) | (913.1, 1204.1) | (91.3, 97.3) | (190.9, 274.9) | |

| 242 | 242 | 242 | 105 | 235 | 235 | 235 | 112 | |

| 8 IM | 30.8 | 354.5 | 63.5 | 81.4 | 84.5d | 934.8d | 91.9d | 240.8d |

| (26.9, 35.2) | (309.6, 405.9) | (57.1, 69.6) | (63.7, 103.9) | (73.7, 96.8) | (815.6, 1071.3) | (87.6, 95.0) | (196.5, 295.2) | |

| 241 | 241 | 241 | 108 | 234 | 234 | 234 | 103 | |

| 7 IMc | 2.6 | 36.6 | 4.15 | 20.2 | 46.4 | 514.6 | 78.8 | 165.5 |

| 5 IMc | (2.4, 2.9) | (33.3, 40.2) | (2.8, 5.9) | (19.2, 21.3) | (42.2, 51.0) | (468.1, 565.7) | (75.6, 81.8) | (146.2, 187.4) |

| 4 IMc | 723 | 723 | 723 | 337 | 698 | 698 | 698 | 315 |

| Placebo IM/SQ | 1.9 | 29.1 | 0 | 18 | 1.9 | 29.7 | 0.4 | 18 |

| (1.85, 1.91) | (28.9, 29.4) | (0.0, 1.5) | (,)e | (1.9, 2.0) | (28.7, 30.6) | (0.01, 2.3) | (,)e | |

| 246 | 246 | 246 | 116 | 243 | 243 | 243 | 124 | |

| Month 6 |

Month 7 |

|||||||

| Anti-PA IgG GMC (μ/ml) |

Anti-PA IgG GMT (μ/ml) |

4-Fold response in Anti-PA IgG titer Response % |

TNA ED50 Titer GMT (unadjusted) |

Anti-PA IgG GMC (μ/ml) |

Anti-PA IgG GMT (μ/ml) |

4-Fold response in Anti-PA IgG titer Response % |

TNA ED50 Titer GMT (unadjusted) |

|

| 8 SQ | 9.5 | 102.6 | 16.8 | 40.8 | 201.1 | 2211.9 | 98.6 | 1281.1 |

| (8.3, 10.9) | (89.2, 118.0) | (12.2, 22.3) | (34.4, 48.3) | (174.7, 231.6) | (1921.8, 2545.9) | (96.1, 99.7) | (1073.9, 1528.3) | |

| 226 | 226 | 226 | 99 | 219 | 219 | 219 | 100 | |

| 8 IM | 8.4 | 92.3 | 19.5 | 41.7 | 232.6d | 2545.6d | 98.6d | 1630.0d |

| (7.3, 9.6) | (80.4, 105.9) | (14.5, 25.2) | (35.4, 49.1) | (202.4, 267.3) | (2215.1, 2925.1) | (96.0, 99.7) | (1354.3, 1961.7) | |

| 226 | 226 | 226 | 124 | 215 | 215 | 215 | 105 | |

| 7 IMc | 3.9 | 46.9 | 5.7 | 22.2 | 206.9d | 2257.d | 97.8d | 1423.9d |

| 5 IMc | (3.6, 4.3) | (42.6, 51.6) | (4.1, 7.8) | (20.8, 23.6) | (187.1, 227.0) | (2050.1, 2484.9) | (96.3, 99.0) | (1253.1, 1617.9) |

| 4 IMc | 662 | 662 | 662 | 313 | 636 | 636 | 636 | 289 |

| Placebo IM/SQ | 1.89 | 29.3 | 0 | 18 | 1.9 | 29.7 | 0.5 | 18.1 |

| (1.89, 1.93) | (28.9, 29.7) | (0.0, 1.6) | (,)e | (1.9, 2.0) | (28.7, 30.8) | (0.0, 2.5) | (17.9, 18.4) | |

| 230 | 230 | 230 | 114 | 220 | 220 | 220 | ||

| Month 42 |

Month 43 |

|||||||

| Anti-PA IgG GMC (μ/ml) |

Anti-PA IgG GMT (μ/ml) |

4-Fold response in Anti-PA IgG titer Response % |

TNA ED50 Titer GMT (unadjusted) |

Anti-PA IgG GMC (μ/ml) |

Anti-PA IgG GMT (μ/ml) |

4-Fold response in Anti-PA IgG titer Response % |

TNA ED50 Titer GMT (unadjusted) |

|

| 8 SQ | 38.1 | 385 | 76.2 | 215.1 | 216.8 | 2282.4 | 100 | 1015 |

| (32.7, 44.4) | (330.4, 448.5) | (68.6, 82.7) | (169.7, 272.7) | (185.8, 253.1) | (1955.8, 2663.5) | (97.5, 100.0) | (827.8, 1244.4) | |

| 151 | 151 | 151 | 64 | 144 | 144 | 144 | 60 | |

| 8 IM | 47.8 | 486.5 | 74.2 | 298.9 | 320.5f | 3425.4f | 100.0d | 1540.3d |

| (41.2, 55.4) | (419.3, 564.5) | (66.3, 81.0) | (245.7, 363.6) | (276.0, 372.1) | (2950.4, 3976.9) | (97.7, 100.0) | (1 274.6, 1861.4) | |

| 159 | 159 | 159 | 73 | 156 | 156 | 156 | 72 | |

| 7 IM | 35.7 | 364 | 85.5 | 215.2 | 254.8d | 2760.4d | 100.0d | 1451.0d |

| (31.2, 40.9) | (317.8, 416.8) | (79.1, 90.6) | (166.4, 278.4) | (222.0, 292.4) | (2404.7, 3168.6) | (97.4, 100.0) | (1139.5, 1847.7) | |

| 147 | 147 | 147 | 67 | 139 | 139 | 139 | 56 | |

| 5 IM | 21.6 | 200.7 | 49 | 174.1 | 310.0f | 3286.4f | 99.3d | 1876.2d |

| (18.9, 24.7) | (175.2, 229.8) | (40.6, 57.4) | (139.3, 217.6) | (270.5, 355.3) | (2866.5, 3767.8) | (96.1, 100.0) | (1603.1, 2195.9) | |

| 145 | 145 | 145 | 72 | 141 | 141 | 141 | 67 | |

| 4 IM | 6 | 61.3 | 13 | 42.7 | 433.2f | 4683.8f | 99.4d | 2825.9d |

| (5.3, 6.9) | (53.8, 69.9) | (8.3, 19.2) | (33.8, 54.0) | (379.6, 494.4) | (4103.0, 5346.8) | (96.5, 100.0) | (2175.2, 3671.3) | |

| 161 | 161 | 161 | 70 | 157 | 157 | 157 | 66 | |

| Placebo IM/SQ | 1.9 | 29 | 0 | 18 | 1.86 | 29 | 0 | 18 |

| (,)e | (,)e | (0.0, 2.5) | (,)e | (1.84, 1.88) | (,)e | (0.0, 2.6) | (,)e | |

| 149 | 149 | 149 | 76 | 139 | 139 | 139 | 66 | |

CI, confidence interval; GMC, geometric mean concentration; GMT, geometric mean titer; IM, intramuscular route; PA, protective antigen; SQ, subcutaneous route; TNA, toxin neutralizing activity; ED50, effective dilution 50%.

Geometric means and CIs were adjusted for study site, age group, sex, race and significant interactions. Geometric means and CIs for the control group, TNA ED50, and titer fold response proportions and CIs were stratified by time period.

Each cell lists the point estimate, 95% confidence interval, and number of participants per group at time point.

The 7 IM, 5 IM, and 4IM groups were combined for this analysis.

Non-inferiority was achieved 4 weeks following study agent injection if the upper bound of the 95% CI for the ratio of the geometric means of the 8-SQ group to that of the test groups was less than 1.5 and if the analogous upper bound for the differences in proportions of 4-fold response was less than 0.10.

All values were the same (i.e., the lower limit of quantification); as a result the variance is 0 and the confidence intervals are undefined.

Statistical superiority was achieved.

Fig. 2.

Anti-protective antigen IgG geometric mean concentration profiles. Time points for serological non-inferiority were months 2, 7, and 43; the responses to injections up to months 0.5, 6, and 42, respectively. Primary serological endpoints were geometric mean concentration (GMC), geometric mean titers (GMT) and proportion of responders with a 4-fold rise in titer (4%XR). Because of the strong positive correlation between anti-protective antigen (PA) IgG concentration and antibody titers (r = 0.99; P < 0.0001), only GMC data are presented in the figure. Analysis-of-variance models were constructed to analyze log-transformed antibody data. Models allowed for the longitudinal nature of the data and included adjustments for study site, age group, sex, race, and significant interactions. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We assessed immune response at month 42, following completion of the priming series but prior to the m43 booster. Among participants in the 4-IM group, 66% had quantifiable anti-PA IgG and 14.3% had levels at least 4-fold greater than LLOQ at m42. Among participants in the 5-IM group, 95.9% of participants had quantifiable anti-PA IgG and 55.9% had levels at least 4-fold greater than LLOQ at m42. All of the individuals in the 4-IM and 5-IM groups responded to the 42-month booster with >99% in both groups achieving at least a 4-fold increase over their month 42 pre-boost anti-PA IgG levels (Fig. 2b). At m43, the 4-IM group post-injection anti-PA IgG response was two-fold greater than that generated by the 8-SQ group (GMC 433.2 μg/ml vs. 216.8 μg/ml) with a 100% frequency of responders (Table 3).

Data were also analyzed at multiple time points for statistical differences between sexes. At m2, there was not a statistical difference between males and females in the 8-SQ group, but there was a statistical difference between males and females in the 8-IM (GMC 67.9 μg/ml males, 103.9 μg/ml females, p < 0.01) and the combined reduced priming series groups (GMC 38.0 μg/ml males, 56.0 μg/ml females, p < 0.01). At m7 and m43 there were no statistically significant differences between sexes (Supplemental Table 1).

In general, there was a decrease in antibody response with age category when assessed within each study group. With few exceptions younger participants mounted a response greater than older participants. This gradient was more pronounced in the peak response time points of months 2, 7, and 43 (Supplemental Table 2). There was no clear pattern in comparisons of race across study groups and time periods. When significant differences did occur, antibody responses in white and “other” race categories almost always exceeded the responses in blacks (Supplemental Table 3).

At the decisive time points of months 2, 7, and 43 there was a strong positive correlation between log(anti-PA IgG concentrations) and log(TNA ED50) (r < 0.91; p > 0.0001). There were no detectable differences in the anti-PA IgG vs. TNA correlations between treatment groups at any of the time points, indicating that neither route of administration nor vaccination schedule had a significant influence on the TNA.

3.3. Reactogenicity

Analysis of in-clinic examination data for injection site AEs demonstrated a significant reduction of occurrence for warmth [females (F): OR = 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) and males (M): OR = 0.25 (0.19, 0.33)], itching (OR = 0.19 (0.14, 0.24), erythema [F: OR = 0.14 (0.10, 0.18), M: OR = 0.29 (0.23, 0.37)], induration [F: OR = 0.19 (0.15, 0.24), M: OR = 0.32 (0.25, 0.42)], edema [OR = 0.36 (0.31, 0.43)], nodules [F: OR = 0.07 (0.05, 0.09), M: OR = 0.20 (0.14, 0.28)] and bruise [OR = 0.72 (0.52, 0.99)] (Table 4) for IM recipients compared to SQ. There was a significant increase in reports of arm motion limitation (AML) for IM compared to SQ [OR = 1.80 (1.37, 2.38)]. There was no significant difference between IM and SQ groups for pain at the injection site [OR = 1.03 (0.84, 1.26)], but the odds of experiencing pain upon injection were reduced by approximately 40% for the IM versus SQ groups [OR = 0.61 (0.51, 0.73)]. Some local AEs increased as the number of injections increased but there was no consistent pattern in regards to increasing reports of AEs with increased number of injections (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 4.

Proportion of adverse events reported by dose during in-clinic exams, by sex and route.

| AE | Sex | IM incidenceb (% of doses) |

SQ incidenceb (% of doses) |

Comparison | Odds ratioc | 95% CI | P-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injection site | |||||||

| Warmtha | Female | 344/2772 (12.4) | 500/952 (52.5) | F vs. M (SQ) | 4.01 | 2.98, 5.40 | <0.01 |

| F vs. M (IM) | 1.71 | 1.33, 2.19 | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 189/2556 (7.4) | 186/827 (22.5) | IM vs. SQ (F) | 0.11 | 0.08, 0.14 | <0.01 | |

| IM vs. SQ (M) | 0.25 | 0.19, 0.33 | <0.01 | ||||

| Tendernessa | Female | 1398/2806 (49.8) | 667/952 (70.1) | F vs. M (SQ) | 2.53 | 1.86, 3.44 | <0.01 |

| F vs. M (IM) | 1.46 | 1.25, 1.72 | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 1075/2584 (41.6) | 410/832 (49.3) | IM vs. SQ (F) | 0.42 | 0.33, 0.53 | <0.01 | |

| IM vs. SQ (M) | 0.73 | 0.57, 0.93 | 0.01 | ||||

| Itching | Female | 160/2762 (5.8) | 247/946 (26.1) | F vs. M | 2.19 | 1.64, 2.93 | <0.01 |

| Male | 77/2551 (3.0) | 80/824 (9.7) | IM vs. SQ | 0.19 | 0.14, 0.24 | <0.01 | |

| Paind | Female | 569/2780 (20.5) | 201/942 (21.3) | F vs. M | 1.67 | 1.41, 1.97 | <0.01 |

| Male | 341/2561 (13.3) | 96/826 (11.6) | IM vs. SQ | 1.03 | 0.84, 1.26 | 0.77 | |

| Arm motion limitation | Female | 434/2771 (15.7) | 94/943 (10.0) | F vs. M | 1.67 | 1.33, 2.09 | <0.01 |

| Male | 218/2558 (8.5) | 50/822 (6.1) | IM vs. SQ | 1.80 | 1.37, 2.38 | <0.01 | |

| Erythemaa | Female | 952/2791 (34.1) | 723/958 (75.5) | F vs. M (SQ) | 3.68 | 2.68, 5.06 | <0.01 |

| F vs. M (IM) | 1.74 | 1.47, 2.05 | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 603/2565 (23.5) | 399/835 (47.8) | IM vs. SQ (F) | 0.14 | 0.10, 0.18 | <0.01 | |

| IM vs. SQ (M) | 0.29 | 0.23, 0.37 | <0.01 | ||||

| Indurationa | Female | 386/2772 (13.9) | 411/946 (43.4) | F vs. M (SQ) | 2.75 | 2.05, 3.69 | <0.01 |

| F vs. M (IM) | 1.59 | 1.29, 1.97 | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 245/2555 (9.6) | 195/830 (23.5) | IM vs. SQ (F) | 0.19 | 0.15, 0.24 | <0.01 | |

| IM vs. SQ (M) | 0.32 | 0.25, 0.42 | <0.01 | ||||

| Edema | Female | 528/2772 (19.0) | 345/948 (36.4) | F vs. M | 1.49 | 1.27, 1.75 | <0.01 |

| Male | 354/2558 (13.8) | 225/827 (27.2) | IM vs. SQ | 0.36 | 0.31, 0.43 | <0.01 | |

| Nodulesa | Female | 161/2762 (5.8) | 409/947 (43.2) | F vs. M (SQ) | 3.96 | 2.83, 5.55 | <0.01 |

| F vs. M (IM) | 1.34 | 0.98, 1.81 | 0.06 | ||||

| Male | 98/2554 (3.8) | 133/825 (16.1) | IM vs. SQ (F) | 0.07 | 0.05, 0.09 | <0.01 | |

| IM vs. SQ (M) | 0.20 | 0.14, 0.28 | <0.01 | ||||

| Bruise | Female | 150/2764 (5.4) | 69/942 (7.3) | F vs. M | 2.21 | 1.68, 2.89 | <0.01 |

| Male | 65/2552 (2.5) | 32/822 (3.9) | IM vs. SQ | 0.72 | 0.52, 0.99 | 0.04 | |

| Systemic | |||||||

| Fatigue | Female | 278/2768 (10.0) | 118/942 (12.5) | F vs. M | 1.39 | 1.11, 1.74 | <0.01 |

| Male | 182/2564 (7.1) | 69/825 (8.4) | IM vs. SQ | 0.80 | 0.62, 1.03 | 0.08 | |

| Muscle ache | Female | 226/2769 (8.2) | 57/942 (6.1) | F vs. M | 1.40 | 1.10, 1.77 | <0.01 |

| Male | 132/2558 (5.2) | 36/825 (4.4) | IM vs. SQ | 1.59 | 1.13, 2.23 | <0.01 | |

| Headache | Female | 219/2767 (7.9) | 90/942 (9.6) | F vs. M | 1.87 | 1.45, 2.42 | <0.01 |

| Male | 105/2559 (4.1) | 39/823 (4.7) | IM vs. SQ | 0.81 | 0.62, 1.06 | 0.12 | |

| Fever | Female | 0/2745 (0.0) | 0/937 (0.0) | F vs. M | NA | NA | NA |

| Male | 1/2546 (0.04) | 0/822 (0.0) | IM vs. SQ | NA | NA | NA | |

| Tender/painful axillary | Female | 17/2762 (0.6) | 10/939 (1.1) | F vs. M | 2.11 | 0.96, 4.67 | 0.06 |

| adenopathy | Male | 8/2553 (0.3) | 3/823 (0.4) | IM vs. SQ | 0.51 | 0.22, 1.20 | 0.12 |

Injection site adverse events with a significant sex and treatment interaction.

Incidence calculated using the safety population cohort.

Odds ratios and p-values are determined from multivariable modeling using the safety population cohort and are adjusted for all factors in the model. If there were ≤5 occurrences in the placebo groups, they were removed prior to model fit. If interactions were significant, then comparisons were conducted within groups.

Pain is defined as a subjective feeling of discomfort in the area of the injection site; this is not pain upon injection which is assessed immediately following the injection using a visual scale. ‘NA’ indicates analyses that could not be conducted due to insufficient number of occurrences (≤5) in the AVA groups. Significance level p ≤ 0.05; SQ, full dose regimen given SQ; IM, full dose regimen given IM. The safety analysis combined data from all groups receiving AVA via the IM route (8-IM, 7-IM, 5-IM and 4-IM) into one IM group, dropping from the analysis any placebo injections in the reduced dosage groups

Route of administration did not have a significant influence on systemic AE occurrence (Table 4), except for a significantly higher occurrence of generalized muscle ache (6.7%) amongst IM recipients compared to SQ (5.3%) [OR 1.59 (1.13, 2.23)]. A lower occurrence of fatigue among IM recipients (8.6%) compared to SQ (10.6%) was observed, but was not significant [OR = 0.80 (0.62, 1.03)].

Regardless of route of injection, females were almost twice as likely as males to experience any injection site AE [OR = 1.90 (1.63, 2.21)]; however, the absolute differences between females and males for warmth, tenderness, itching, pain, erythema, induration, edema, bruise, and nodules (all except AML) were largest amongst SQ recipients (Table 4). Females also had a significant increase in the odds of experiencing greater pain upon injection compared to males [OR = 1.91 (1.64, 2.22)]. When looking at in-clinic data, females had a significantly increased odds for the occurrence of solicited systemic AEs fatigue [OR = 1.39 (1.11, 1.74)], muscle ache [OR = 1.40 (1.10, 1.77)], and headache [OR 1.87 (1.45, 2.42)] when compared to males (Table 4). The sex by treatment group interaction term for systemic AEs was not significant in any of the models, indicating that the differences in systemic AEs between men and women were generally consistent across all study groups. These findings were consistent when AE summary data were analyzed, which also demonstrated that occurrence of fever was not significantly different between males and females [OR 1.26 (0.86, 1.85)].

231 serious AEs, including 7 deaths, occurred following 11,135 injections. These serious AEs occurred in 186 (11.9%) of the 1563 participants and were distributed across all 6 study groups. After a blinded review the Medical Monitor concluded that serious AEs occurring in 7 participants were possibly related to the study agent; it was noted upon unblinding that 1 of the 7 received placebo (Supplemental Table 5). None of the deaths were considered possibly related to vaccination. All other events were considered to be unrelated or unlikely related to the investigational agent.

4. Comment

These data confirm that the minimal schedule, comprised of a 3-dose IM priming series administered at months 0, 1 and 6, followed by a single booster at month 42 (4-IM group), established robust immunological priming and sustained immunological memory to at least 42 months. At month 7, and all points subsequent when vaccine was administered, the anti-PA IgG responses generated in IM recipients were non-inferior to those in SQ recipients. This study confirms IM administration has significant advantages in reducing reactogenicity without compromising immunogenicity. These data endorse the conclusions from the study interim analysis up to the month 7 time point that were central to the change in use of AVA to IM administration and elimination of the dose at week 2 (0.5m) approved in 2008 [19,20]. As of July 2013, these data were used to support the first approval for AVA use in the European Union. The approval was in Germany and is for the 3-IM priming series (injections at m0, 1, and 6) with a triennial (m42) booster.

Attaining noninferiority at month 7 emphasizes the importance of completing the 0, 1, 6 month priming series. In the Brachman study of a predecessor anthrax vaccine [3] there were three vaccine breakthrough cases. All three cases had received only the 0–2–4wk initial series of the schedule at the time they contracted disease; 2 cases contracted cutaneous anthrax just prior to receiving the month 6 dose and the third case contracted cutaneous anthrax at 15 months having received only the initial series. There were no cases reported in participants receiving the month 6 dose [3]. Vaccine induced protection during the first six months of the priming series is a major focus for studies of AVA use during post-exposure prophylaxis [37].

As expected, the extended periods between booster doses in the reduced vaccination schedules resulted in lower levels of anti-PA IgG prior to vaccination. However, the persistence of quantifiable anti-PA IgG and the exceptional recall responses to a booster dose administered at either m18 or m42 were noteworthy. Most striking was the immune response among the 4-IM group to the m42 injection, the triennial booster. Prior to the m42 booster the 4-IM group had lower antibody levels than the 5-IM group; however, the booster elicited anti-PA IgG GMCs in the 4-IM group that by m43 were 2-fold higher (exceeding 430 μg/ml) and statistically superior to those achieved by the originally licensed 8-SQ annual booster at the same time point (Table 3). Collectively these data confirm that the 3-dose IM priming series established long term antibody secreting plasma cell populations and robust immunological memory manifested by rapid and high anamnestic responses. These factors are central to mounting a protective immune response to inhalation anthrax when circulating anti-PA antibody levels are low [38,39]. These data, together with duration of protection studies in rhesus macaques, challenge the AVA vaccination dogma that annual boosters are required to maintain immunity [40,41]. Additionally, the consistent high correlations between anti-PA levels and their TNA indicate that the functional integrity of the humoral immune response to AVA was maintained across all schedules tested for the duration of the study. The data from this analysis were used to support the recent change (May 2012) in the AVA schedule to a 3 dose IM priming series (0,1,6 months) with subsequent boosters at 12 and 18 months, and annually thereafter (http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm304758.htm). In conjunction with data from non-human primate studies [41,42], these human data also demonstrate the feasibility of reducing the annual booster schedule to a less demanding but no less effective, triennial booster schedule.

In this study, IM administered AVA behaved like other aluminum containing vaccines such as DTP, Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B, with adverse events typically limited to injection site reactions such as erythema and nodule formation [18,43]. Adverse event rates were similar between IM administered AVA and IM administered Alhydrogel recombinant Protective Antigen (rPA) vaccines currently under development [44-46]. These data demonstrate that IM administration improves the safety profile for AVA. Independent review by the Medical Monitor concluded that SAEs were unrelated or unlikely related to AVA. The study was not statistically powered to identify very rare SAEs.

Previously published data from the interim analysis [19] was utilized by ACIP when the current recommendations [40] were developed. The current ACIP recommendation for post exposure prophylaxis (PEP) use of AVA is SQ administration of 3 doses at 0, 2, and 4 weeks [40]. Although not an objective of the AVRP clinical trial, these results may provide guidance for the PEP regimen. IM administration does result in decreased reactogenicity, which might enhance adherence to the PEP regimen. Analysis of the final study data identified robust anti-PA IgG responses at the m2 time point following both IM and SQ vaccination. However, statistically significant sex related differences in the magnitude of the anti-PA IgG responses occurred at the m2 time point following IM vaccination compared to SQ; the clinical significance of this is not known. Although achieving high anti-PA levels by m2, males vaccinated IM had significantly lower anti-PA IgG GMC levels than females (67.9 μg/ml vs. 103.86 μg/ml respectively; p = 0.01). By month 7, there were no significant differences in SQ and IM between the sexes in any group. For optimization of AVA use for PEP it will be important to understand the impact of sex related differences on vaccine effectiveness.

5. Conclusion

These final analyses clearly demonstrate that a 3 dose IM priming schedule elicits long term immunological responses and robust immunological memory that is efficiently stimulated by a single booster vaccination at 42 months. When 3 dose IM priming injections are followed by triennial boosters, the resultant immune response is non-inferior and in some instances statistically superior to the SQ schedule, indicating a more robust response to fewer doses of vaccine administered IM. The data demonstrate that AVA is as safe as other aluminum containing vaccines currently licensed in the US, and that IM administration remains significantly associated with a reduction in injection site AEs.

Supplementary Material

Funding/support

The study was funded through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Role of the sponsor

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was responsible for the development of the study protocol and for the statistical analyses.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

Abbreviations:

- IM

intramuscularly

- SQ

subcutaneous

- AVA

anthrax vaccine adsorbed

- PA

protective antigen

- DoD

Department of Defense

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- AVRP

Anthrax Vaccine Research Program

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IND

Investigational New Drug

- GCP

Good Clinical Practices

- USAMMA

United States Army Medical Materiel Agency

- LTx

lethal toxin

- AE

adverse event.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

No financial conflicts were reported for any author.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.039.

This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov under the registry number NCT00119067.

Pre-injection samples were obtained during the injection visits (m0, m1, m6, m12, m18, m30, m42); m0 served as the baseline sample. Post-injection samples were obtained 4 weeks following injection (m1, m2, m7, m13, m19, m31, m43); m1 served as the post-injection sample for both the m0 and m0.5 injections.

Data for 7 and 43 month time points are for ATP cohort.

References

- [1].Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed. United States patent US 3208909; September 28, 1965.

- [2].BioThrax (anthrax vaccine adsorbed) [Vaccine package insert]. Rockville, MD: Emergent BioSolutions; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brachman PS, Gold H, Plotkin SA, Fekety FR, Werrin M, Ingraham NR. Field evaluation of a human anthrax vaccine. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1962;52(4):632–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wright GG, Green TW, Kanode RG Jr. Studies on immunity in anthrax. V. Immunizing activity of alum-precipitated protective antigen. J Immunol 1954;73:387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tresselt HB, Boor AK. An antigen prepared in vitro effective for immunization against anthrax. III. Immunization of monkeys against anthrax. J Infect Dis 1955;97:207–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Turnbull PC, Broster MG, Carman JA, Manchee RJ, Melling J. Development of antibodies to protective antigen and lethal factor components of anthrax toxin in humans and guinea pigs and their relevance to protective immunity. Infect Immun 1986;52:356–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Little SF, Knudson GB. Comparative efficacy of Bacillus anthracis live spore vaccine and protective antigen vaccine against anthrax in the guinea pig. Infect Immun 1986;52:509–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ivins BE, Ezzell Jr JW, Jemski J, Hedlund KW, Ristroph JD, Leppla SH. Immunization studies with attenuated strains of Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun 1986;52:454–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Darlow H, Belton F, Henderson D. The use of anthrax antigen to immunise man and monkey. Lancet 1956;271:476–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Auerbach S, Wright GG. Studies on immunity in anthrax. VI. Immunizing activity of protective antigen against various strains of Bacillus anthracis.J Immunol 1955;75:129–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ward MK, McGann VG, Hogge AL Jr, Huff ML, Kanode RG Jr, Roberts EO. Studies on anthrax infections in immunized guinea pigs. J Infect Dis 1965;115:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ivins B, Fellows P, Pitt M. Efficacy of a standard human anthrax vaccine against Bacillus anthracis aerosol spore challenge in rhesus monkeys. Salisbury Med Bull 1995;87(Suppl. 125–126). [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pitt M, Ivins BE, Estep JE, Farchaus J, Friedlander AM. Comparison of the efficacy of purified protective antigen and MDPH to protect non-human primates from inhalation anthrax. Salisbury Med Bull 1996;87:130. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ivins BE, Pitt ML, Fellows PF, Farchaus JW, Benner GE, Waag DM, et al. Comparative efficacy of experimental anthrax vaccine candidates against inhalation anthrax in Rhesus macaques. Vaccine 1998;16:1141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cohen WA, The Secretary of Defense. Implementation of the Anthrax Vaccination Program for the Total Force. May 18, 1998. http://www.vaccines.mil/documents/902implementationpolicy.pdf [accessed 13.06.11]. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pittman PR, Kim-Ahn G, Pifat DY, Coonan K, Gibbs P, Little S, et al. Anthrax vaccine: immunogenicity and safety of a dose-reduction, route-change comparison study in humans. Vaccine 2002;20(9–10):1412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pittman PR, Mangiafico JA, Rossi CA, Cannon TL, Gibbs PH, Parker GW, et al. Anthrax vaccine: increasing intervals between the first two doses enhances antibody response in humans. Vaccine 2000;19(2–3):213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Joellenbeck L, Zwanziger LL, Durch JS, Strom BL. The anthrax vaccine: is it safe? Does it work? Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Marano N, Plikaytis BD, Martin SW, Rose C, Semenova VA, Martin SK, et al. Effects of a reduced dose schedule and intramuscular administration of anthrax vaccine adsorbed on immunogenicity and safety at 7 months: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008;300:1532–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sun W, Food and Drug Administration. Biologics license application supplement approval letter. December 11, 2008. Available at http://www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm124462.htm [accessed 13.06.11]. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Quinn CP, Semenova VA, Elie CM, Romero-Steiner S, Greene C, Li H, et al. Specific, sensitive, and quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human immunoglobulin G antibodies to anthrax toxin protective antigen. Emerg Inf Dis 2002;8(10):1103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Semenova VA, Steward-Clark E, Stamey KL, Taylor TH, Schmidt DS, Martin SK, et al. Mass value assignment of total and subclass immunoglobulin G in a human standard reference serum. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2004;11(5):919–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Plikaytis BD, Holder PF, Carlone GM. ELISA for Windows user’s manual, version 2.00. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/bimb/ELISA.htm [accessed 14.09.11]. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Soroka SD, Schiffer JM, Semenova VA, Li H, Foster L, Quinn CP. A two stage multilevel quality control system for serological assays in anthrax vaccine clinical trials. Biologicals 2010;38(6):675–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Soroka SD, Taylor TH, Freeman AE, Semenova VA, Plikaytis BD, Quinn CP. A new mathematical approach to calculating dilutional titer endpoints (abstract No. P34). In: Bacillus ACT05 international conference on Bacillus anthracis, B. thuringiensis and B. cereus. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hornung RW, Reed LD. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 1990;5:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Li H, Soroka SD, Taylor TH Jr, Stamey KL, Stinson KW, Freeman AE, et al. Standardized, mathematical model-bases and validated in vitro analysis of anthrax lethal toxin neutralization. J Immunol Methods 2008;33:89–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hering D, Thompson W, Hewetson J, Little S, Norris S, Pace-Templeton J. Validation of the anthrax lethal toxin neutralization assay. Biologicals 2004;32:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lu H, Catania J, Baranji K, Feng J, Gu M, Lathey J, et al. Characterization of the native form of anthrax lethal factor for use in the toxin neutralization assay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013;20(July (7)):986–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Castelán-Vega J, Corvette L, Sirota L, Arciniega J. Reduction of immunogenicity of anthrax vaccines subjected to thermal stress, as measured by a toxin neutralization assay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011;18(February (2)):349–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Omland KS, Brys A, Lansky D, Clement K, Lynn F. Participating laboratories. Interlaboratory comparison of results of an anthrax lethal toxin neutralization assay for assessment of functional antibodies in multiple species. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2008;15(June (6)):946–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].“What is a Serious Adverse Event?”. US Food and Drug Administration, page last updated 23.06.11. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/HowToReport/ucm053087.htm [accessed 02.09.11]. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Causality assessment of adverse events following immunization. Wkly Epidemiol Record 23 March 2011;12(76):85–92 http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/causality/en/ [accessed 30.01.12]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schuirmann DJ. A comparison of the two onesided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability.J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1987;15(6):657–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Phillips KF. Power of the two one-sided tests procedure in bioequivalence. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1990;18(2):137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Farrington CP, Manning G. Test statistics and sample size formulae for comparative binomial trials with null hypothesis of non-zero risk difference or nonunity relative risk. Stat Med 1990;9(12):1447–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ionin B, Hopkins RJ, Pleune B, Sivko GS, Reid FM, Clement KH, et al. Evaluation of immunogenicity and efficacy of anthrax vaccine adsorbed for postexposure prophylaxis. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013;20(July (7)):1016–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Livingston BD, Little SF, Luxembourg A, Ellefsen B, Hannaman D. Comparative performance of a licensed anthrac vaccine versus electroporation based delivery of a PA encoding DNA vaccine in Rhesus macaques. Vaccine 2010;28(January (4)):1056–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Marcus H, Danieli R, Epstein E, Velan B, Shafferman A, Reuveny S. Contribution of immunological memory to protective immunity conferred by a Bacillus anthracis protective antigen-based vaccine. Infect Immun 2004;72(June (6)):3471–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].CDC. Use of anthrax vaccine in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morb Mort Wkly Rep 2009;59(RR-6). July 23, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Quinn CP, Sabourin CL, Niemuth NA, Li H, Semenova VA, Rudge TL,et al. A three dose intramuscular schedule of anthrax vaccine adsorbed generates sustained humoral and cellular immune responses to protective antigen and provides long term protection against inhalation anthrax in Rhesus macaques. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012;19(11):1730–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Madigan D 8 November 2007. Anthrax vaccines: bridging correlates of protection in animals to immunogenicity in humans. Washington, DC: Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/NewsEvents/WorkshopsMeetingsConferences/TranscriptsMinutes/UCM054424.pdf [accessed 06.07.12]. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Eickhoff TC, Myers M. Workshop summary. Aluminum in vaccines. Vaccine 2002;20(May (Suppl. 3)):S1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Campbell JD, Clement KH, Wasserman SS, Donegan S, Chrisley L, Kotloff KL. Safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of are combinant protective antigen anthrax vaccine given to healthy adults. Hum Vaccine 2007;3:205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gorse GJ, Keitel W, Keyserling H, Taylor DN, Lock M, Alves K, et al. Immunogenicity and tolerance of ascending doses of a recombinant protective antigen (rPA102) anthrax vaccine: a randomized, double-blinded, controlled, multicenter trial. Vaccine 2006;24:5950–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Brown BK, Cox J, Gillis A, VanCott TC, Marovich M, Milazzo M, et al. Phase I study of safety and immunogenicity of an Escherichia coli-derived recombinant protective antigen (rPA) vaccine to prevent anthrax in adults. PLoS One 2010;5(November (11)):e1384P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.