ABSTRACT

Epigenome editing consists of fusing a predesigned DNA recognition unit to the catalytic domain of a chromatin modifying enzyme leading to the introduction or removal of an epigenetic mark at a specific locus. These platforms enabled the study of the mechanisms and roles of epigenetic changes in several research domains such as those addressing pathogenesis and progression of cancer. Despite the continued efforts required to overcome some limitations, which include specificity, off-target effects, efficacy, and longevity, these tools have been rapidly progressing and improving.

Since prostate cancer is characterized by multiple genetic and epigenetic alterations that affect different signalling pathways, epigenetic editing constitutes a promising strategy to hamper cancer progression. Therefore, by modulating chromatin structure through epigenome editing, its conformation might be better understood and events that drive prostate carcinogenesis might be further unveiled.

This review describes the different epigenome engineering tools, their mechanisms concerning gene’s expression and regulation, highlighting the challenges and opportunities concerning prostate cancer research.

KEYWORDS: Prostate cancer, epigenome editing, crispr-dCas9, fusion proteins

Introduction

Chromatin roughly adopts two distinct states: heterochromatin, which represents condensed DNA, and euchromatin, composed of less packaged DNA [1]. Epigenetics deals with the biochemical modifications of histone proteins and DNA which determine such chromatin structures and subsequently govern gene expression patterns. These alterations are heritable, reversible, and persist during cell division but, unlike genetic abnormalities, do not alter DNA sequence [2,3]. Until now, four major epigenetic mechanisms have been disclosed: DNA methylation, histone post-translation modifications (PTM) in close interplay with chromatin remodelling and histone variants. Although little is known about how these mechanisms are directed, some non-coding RNAs have been described to play a role here [4].

In humans, DNA methylation occurs mostly at cytosines of cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, often located at gene promoters [4,5]. It consists of covalent addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of the cytosine ring, catalysed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), resulting in a new DNA base, 5-methylcytosine (5mC) [6]. Reversal of DNA methylation may be passively achieved if the methyl mark fails to be reproduced after DNA replication. Alternatively, ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes can oxidize 5mC and through sequential steps thereby actively leading to unmethylated cytosine [7].

Histone proteins may also be chemically modified. These alterations are introduced and removed by so-called writers and erasers, and recognized by chromatin remodellers [8]. Among them, histone methyltransferases (HMTs) catalyse the transfer of a methyl group to histones’ arginine or lysine residues, while histone demethylases (HDMs) remove it. Additionally, lysines can be either mono-, di- or trimethylated, whereas arginines may be mono- or symmetric or asymmetrically dimethylated [9]. Moreover, histone acetyltransferases (HATs) transfer an acetyl group from acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) to histone lysine residues. Conversely, histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove the acetyl group [8]. Apart from these alterations, histones can undergo other post-translational modifications (PTMs), which include lysine ubiquitination, lysine sumoylation, ADP-ribosylation, serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphorylation among others [10].

Interestingly, not only chromatin modifications influence transcription, but also vice versa with transcription actively altering epigenetic marks. This bi-directional relationship between gene expression and epigenetic modifications is intensely investigated and its causality is currently under exploration [11,12].

Epigenetic deregulation has been commonly reported in cancer initiation [13] and the heritable and reversible nature of these abnormalities have led to epigenetic therapies entering the cancer treatment arena [4]. Thus far, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two epigenetic drugs targeting DNMTs azacitidine (Vidaza) and decitabine (Dacogen), for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes [14–17]. Furthermore, four HDACs inhibitors, namely Vorinostat, Romidepsin, Belinostat, and Panobinostat, have also been FDA-approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), refractory CTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), and multiple myeloma, respectively [18–21]. Nonetheless, these drugs typically lack gene specificity, resulting in epigenome-wide modifications, which can contribute to tumorigenesis, progression, and aggressiveness [22]. Additionally, the lack of success of these drugs in solid tumours may be explained by the higher proliferative rate of hematolymphoid malignancies [23–25]. Thus, molecular tools which may precisely edit specific genomic sites are needed to establish a causal relationship between epigenetic marks and specific gene transcription profiles.

The quest for this specificity entailed the development of epigenetic editing tools which are largely inspired by the genomic editing platforms that were available beforehand. Epigenetic editing is achieved by fusing a predesigned DNA recognition unit to the catalytic domain of a chromatin modifying enzyme leading to the introduction or removal of an epigenetic mark at a specific locus [26,27]. Ideally, the introduction of the desired epigenetic modification at a locus-specific site could cause long-lasting effects on chromatin and hence affect gene expression [27]. However, only few examples addressed longevity [28–33].

Epigenome Engineering Tools

Zinc-Finger Proteins

The earliest protein-based epigenome editing platform developed was based on zinc finger proteins (ZFs) (Figure 1a). ZFs are small, simple, versatile, and high affinity DNA-binding domains consisting of several Cys2His2 (C2H2) motifs, with 28–30 amino acids disposed in a linear arrangement [27,34–36]. Whereas, in general, each zinc finger recognizes three DNA base pairs (bp) [37], multi-ZF proteins consist of three to six individual ZFs engineered to bind to a target site of nine to 18 base pairs (bp). Since multi-ZF protein do not possess intrinsic regulatory properties, they generally are linked to an effector domain with either transcriptional activity or epigenetic modifying properties, although they can repress gene transcription without any effector [27,38] (Figure 2).

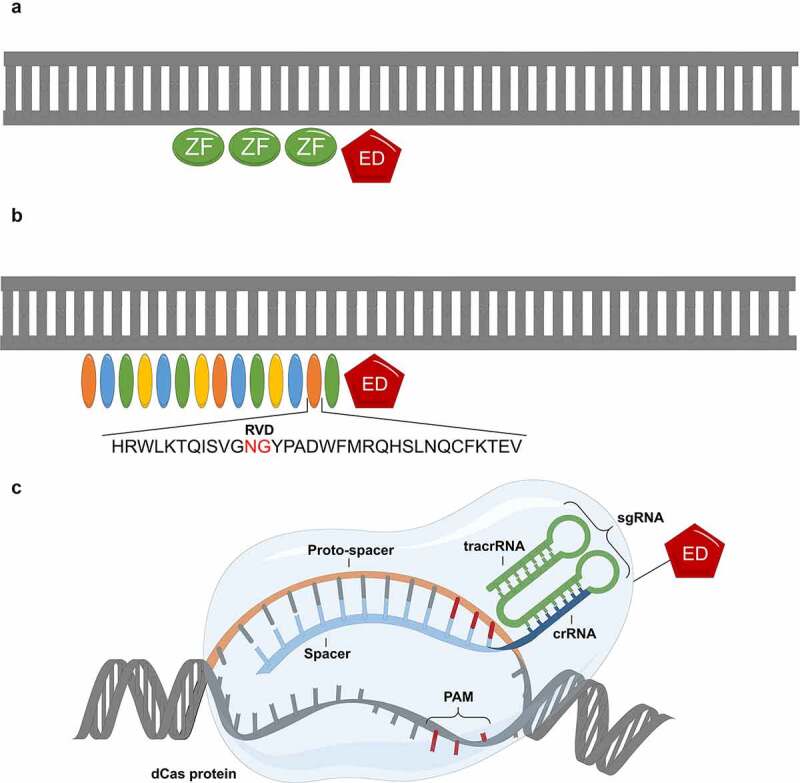

Figure 1.

Epigenome engineering tools: (a) Zinc Finger Proteins (ZF), (b) Transcriptional Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) and (c) clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-dCas9. ED-effector domain.

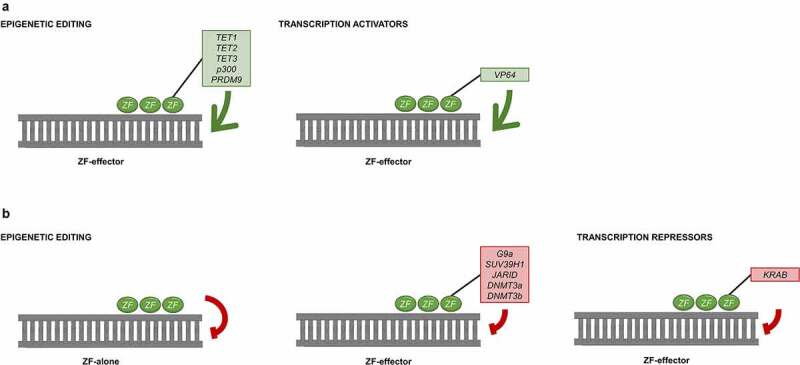

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of ZF to modulate gene expression: gene activation (a) can be accomplished with epigenetic effectors (green box) or transcription activators (green box); gene repression (b) is achieved with ZF alone or with an epigenetic effector (red box) or with transcription repressors (red box).

The first generation of ZFs was coupled to a transcriptional activator, namely VP64, which led to the activation of many tumour suppressor genes (TSG) that were silenced by methylation in cancer [39–45]. Additionally, they have also been linked to epigenetic effectors to induce upregulation of gene expression. For instance, ZFs have been coupled to either the entire epigenetic protein or just the effector domain such as TET1, TET2, and TET3 enzymes [46,47], HATs proteins, such as p300 [48], as well as HMTs proteins like PRDM9 [29].

ZFs have been linked to HMTs G9a and SUV39H1, promoting VEGF-A and Her2/neu gene repression [49,50] and to HDMs JARID, resulting in a TCTN2 downregulation [51]. Interestingly, the combination of ZF-HMTs with ZF-HDACs increased repression further, contrarily to multiple ZFs with each of the effector domain alone, suggesting that there is a synergistic activity between HDACs and HMTs [49]. Besides these studies, the first example of targeted DNA methylation in human cells was the fusion of DNMT3a or DNMT3b to ZFs, demonstrating that several genes could be successfully downregulated [38,52–55]

The Krüppel-associated box (KRAB)-ZF fusion was also demonstrated to promote gene repression, although its mechanism of action remains unclear. On the one hand, it is suggested that KRAB reduces H3 acetylation at the target promoter [50]. On the other hand, repression induction was reported without any change in histone modifications [56]. Furthermore, ZF-DNMT3a or ZF-KRAB fusions have been successfully used with doxycycline-inducible lentiviruses resulting in long-term stable gene repression in cancer cells [32,53].

Transcriptional Activator-Like Effectors

The second generation of modular DNA-binding domains arose from the transcriptional activator-like effectors (TALEs) (Figure 1b). TALE proteins are secreted by Xanthomonas bacteria and translocate directly into the plant cells. Once there, they act as transcription factors which recognize and activate host genes to support bacterial growth or release from the plant [57,58].

TALEs consist of individual TALE modules (7–34 tandem repeats) each composed of 33–35 amino acids [57,59]. These amino acids are highly conserved with the exception of the repeat-variable di-residue (RVD) at positions 12 and 13, which determine the base to which the TALE module binds [59,60]. In contrast to ZF proteins, each TALE RVD binds with high specificity to one nucleotide. RVDs comprising NI, HD, NG, and NN residues bind to A, C, T, and G/A nucleotides, respectively [61]. Therefore, by combining repeats specific to each DNA nucleotide, TALE engineer tool allows for more specific targeting of any DNA sequence of interest. The specific binding properties of a RVD depend on the number of repeats in the TALE, the position of the repeat within the TALE and the identity of neighbouring repeats [62]. Despite the one-to-one interaction between RVD and nucleotide, there are still off-targets that can be assessed by several tools, such as SIFTED and TALgetter [62,63]. However, most of them are based on the specificity and binding strength of individual RVDs [63].

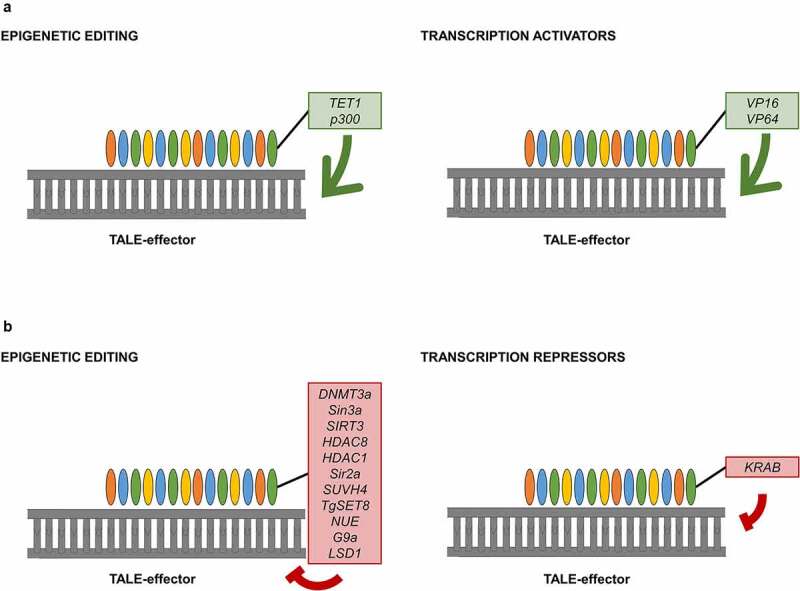

TALEs have been engineered for regulation of endogenous genes (Figure 3). The most common combination is with transcriptional activators such as VP16 [64] and its tetramer, VP64 [65]. Similarly to ZFs, TALEs were also linked to epigenetic effectors such as TET1 [66] as well as DNMT3a leading to successful editing of DNA methylation in human cells [67] and demonstrating its potency as epigenetic editor [68]. Other epigenetic enzymes such as HDACs Sin3a, SIRT3, HDAC8, HDAC1, and Sir2a have also been coupled to TALEs, resulting in repression of Neurog2 and Grm2. These genes have been also repressed, by targeting TALEs fused to HMTs, such as SUVH4 from a plant (Arabidopsis thaliana), TgSET8 from a parasite (Toxoplasma gondii) and NUE from a bacteria (Chlamydia trachomatis) [69]. Similar to ZF-G9a studies, TALEs have also been fused to G9a, targeting E-Cadherin [70]. In order to activate gene expression, the catalytic core of the p300 HATs has been linked to ZFs [48]. Finally, TALE-KRAB and TALE fused with HDMs lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) were used as alternative epigenetic editing tools for gene repression [71,72].

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of TALE to modulate gene expression: gene activation (a) can be accomplished with epigenetic effectors (green box) or transcription activators (green box); gene repression (b) is achieved with an epigenetic effector (red box) or with transcription repressors (red box).

CRISPR-dCas9

The discovery of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR) systems revolutionized genome and epigenome editing techniques. In bacteria, small fragments of invading nucleic acids, the proto-spacers are integrated into the host genome upon bacteriophage infection. Subsequently, spacers are transcribed into various CRISPR RNAs (crRNA), complementary to the sequence in invader DNA, and direct Cas proteins to the appropriate cleavage site [73,74]. A second RNA, the transactivating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), is also transcribed from a genomic locus upstream the CRISPR locus [75]. Together with crRNA, they form the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) which recognizes 18–20 bp target sequences [76]. Unlike ZFs and TALEs, CRISPR systems thus rely on Watson/Crick base-pairing between sgRNA and target DNA [1,33]. Cas proteins which perform helicase and nuclease functions at target sites upstream of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). This sequence varies according to CRISPR-Cas system type [77] and is necessary for both target recognition and cleavage [76] (Figure 1c). Thus far, two classes and six types of CRISPR-Cas systems have been described, and the most commonly used is class 2 type II CRISPR system of Streptococcus pyogenes (Sp) [77,78].

Cas9 was firstly used in genome editing, in which it cleaves double-stranded DNA, to introduce gene changes by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or precise changes induced through homology-directed repair (HDR) [79,80]. However, mutations D10A and H840A in Cas9 nuclease domains RuvC and HNH allowed for the creation of a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9), which is still able to bind to DNA in a sequence-specific manner but is unable to cleave DNA [77,81,82]. The fusion of dCas9 with effector domains, such as transcription enhancing and repressing factors and epigenetic modulators has enabled epigenome editing [81,83] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of CRISPR-dCas9 to modulate gene expression: gene activation (a) can be accomplished with epigenetic effectors (green box) or transcription activators (green box) or with a conjunction of effectors, such as in VPR-, SAM- and SunTag-systems; gene repression (b) is achieved with dCas9 alone or with an epigenetic effector (red box) or with transcription repressors (red box) .

The first examples using dCas9 for transcriptional regulation were fusions with conventional transcriptional activators such as VP64 [84], VP160 [85], VP192 [86] which are composed of tandem copies of VP16, p65, or even a subunit of RNA polymerase [87], or with a new system that fuses VP64-dCas9 with a blue fluorescent protein (BFP)-VP64 [88] (Figure 4a). Further efforts led to a second-generation of activators, which recruit multiple effectors to a single dCas9-sgRNA complex. For instance, the multi-part activation system, VPR, consisting of VP64, p65, and Epstein–Barr virus R transactivator (Rta) allowed for an improved upregulation of the target gene by delivering a single sgRNA [89]. Moreover, the engineering of protein-interacting RNA aptamers in the sgRNA increased the efficacy of transcriptional upregulation. In this technique, aptamer loops were introduced to be recognized by the MS2 bacteriophage coat protein and by MS2-VP64 fusion proteins. Thus, instead of VP64 being directly linked to dCas9, MS2-VP64 is recruited to the sgRNA at the target site [90]. With the same principle, the synergistic activation mediator (SAM) system used sgRNA engineered with aptamer loops to bind MS2 fused to p65 and HSF1, delivered together with dCas9-VP64 [91]. This system has also been exploited using dCas9-VPR instead of dCas9-VP64 [92]. Another variation of CRISPR activation system was achieved with SUperNova tagging (SunTag) system, which consists of 10 repeats of the GCN4 peptide separated by short linkers, fused to dCas9. These peptides recruit single-chain variable fragments (scFVs) which are linked to VP64, thus directing up to 10 fused protein to a single dCas9 for stronger transactivation [93]. Extending this method, fusing scFVs to TET1 allowed for DNA demethylation at a target region rather than transcriptional activation [94], resulting in a significant demethylation of CpG islands and promoters, with subsequent transcriptional upregulating of several genes, both in vitro and in vivo [95–98]. Interestingly, dCas9-TET1 could reverse gene silencing to levels similar to 5-aza, which were not obtained using dCas9-VP160 and dCas9-p300 [28]. In contrast, another study reported that dCas9-ROS1 (active DNA demethylation enzyme in plants) could reactivate methylated silenced genes more effectively than dCas9-TET1. This can be attributable to the different sizes of both enzymes, since TET1 is larger than ROS1, thus hampering its incorporation. In this study, dCas9-ROS1 demethylation induction was as successful in promoting re-expression as dCas9-VP160 and dCas9-p300 [99].

The dCas9 was also linked to HATs p300 and directed to enhancers to activate gene expression. dCas9-p300 demonstrated more robust editing capacities and consequent activation compared to ZF- and TALE-p300 [48]. However, in contrast to dCas9-VP64, delivering dCas9-p300 with multiple sgRNA for a single target locus did not result in synergistic effect [48].

Moreover, dCas9-HDAC3 was successful in modulating gene expression, although gene upregulation depended on the position of sgRNA. This finding indicates that HDAC3 may recruit different effectors depending on the proximity of sgRNA to H3K27ac marks as well as on chromatin microenvironment [100]. Similarly, dCas9-EZH2 and dCas9-KRAB enabled long-term SNURF repression, but at HER2 dCas-KRAB could only bring a transient effect [31]. These data demonstrate that fine-tuning of targeting tools is necessary to target different loci in any cell type. Furthermore, the HATs domain of transcriptional coactivators CREB binding protein (CBP) was also coupled to dCas9, leading to increased OCT4 expression [101].

In addition to histone acetylation, the CRISPR-dCas9 gene activation system has also been applied to histone methylation. HMTs PRDM9 was linked to dCas9, resulting in histone methylation and increased transcription levels. DOT1L, another HMTs, has also been fused with dCas9. The delivery of both dCas9-PRDM9 and dCas9-DOT1L resulted in more potent and long-lasting epigenetic editing than either of them alone [29]. Finally, SMYD3, also an HMTs, has been engineered with dCas9, which elucidated its mechanistic involvement in stimulating oncogenic processes [102].

CRISPR-dCas9 systems have been also explored for gene repression studies (Figure 4b). It has been demonstrated that the direction of dCas9 to proximal promoters without any effector domain leads to gene repression [103]. Nevertheless, the fused dCas9-KRAB system has led to more potent gene repression [87,104]. When targeted to an enhancer region, dCas9-KRAB induced H3K9me3, reduced chromatin accessibility of the enhancer and respective promoter and silenced gene expression of multiple sites that were related to the enhancer [105]. Both KRAB and LSD1 were engineered with Neisseria meningitidis (Nm) dCas9. Whereas NmdCas9-LSD1 only altered epigenetic marks at the enhancer, NmdCas9-KRAB modified them both at enhancer and promoter level, thus leading to gene repression, indicating that NmdCas9-LSD1 mechanism was enhancer specific [106].

Gene repression has also been accomplished with the induction of histone methylation via dCas9 tool. HMTs G9a was linked to dCas9, producing stable gene repression in contrast to dCas9-KRAB system, which could only repress the same gene temporarily [55,107]. EZH2, another HMTs, was linked to dCas9, manipulating H3K27me3, consequently inducing gene repression in Japanese fish embryos [108]. In addition, another study observed long-term repression of SNURF and HER2 using the combination of EZH2-dCas9 with DNMT3a-dCas9 and DNMT3L-dCas9 tools [31].

Besides, CRISPR-Cas9 systems have been applied for targeted DNA methylation as well. dCas9-DNMT3a was used to decrease expression of several genes [95,109,110]. Nevertheless, it was not very stable and returned to the previous epigenetic profile five to 15 days after transfection. However, this engineered tool was more efficient than TALE-DNMT3a [110]. The further developed dCas9-DNMT3a-DNMT3L fusion displayed approximately 4–5 times stronger DNA methylation and corresponding gene silencing comparing to DNMT3a alone [111]. A bacterial DNMT (M.SssI-MQ1) was also engineered with dCas9 in human cells. Interestingly, this fusion protein increased methylation levels at the three studied loci. In fact, compared to dCas9-DNMT3a, the bacterial fusion required shorter incubation times (1 day) to achieve maximal effects, whereas dCas9-DNMT3a reached its methylation peak at day 7. However, dCas9-DNMT3a was found to be more suitable for editing a wider region (~150 bp), contrasting with the centralized methylation pattern of dCas9-MQ1 (~30 bp). Hence, this study demonstrated that both fusions may be optimal depending on their applications. Moreover, this study tested for the first time dCas9-MQ1 system in mice by microinjecting this fusion into mouse zygotes, demonstrating its potential use in vivo [112].

Although most of these engineered tools do not offer lasting epigenetic editing after ceasing the expression of the editing constructs, the codelivery of dCas9-DNMT3L, dCas9-DNMT3a, and dCas9-KRAB induced a long-term increase of DNA methylation level and corresponding gene repression with only temporary expression of the effector domains. Overall, to achieve long-term editing, histone modifications, and DNA methylation should be co-targeted [28–32].

Critical Parameters of Epigenetic Editing

Specificity and longevity

Off-target activity occurs due to accidental epigenetic modification at non-specific site. As previously discussed, ZFs display off-target binding throughout the genome [50,56], but TALEs exhibit lower levels of binding to off-target sites [72,113]. Although some studies claim that CRISPR-Cas discloses levels of off-target binding similar to ZFs, CRISPR-Cas systems might be improved to show great specificity [113–116]. Indeed, sgRNA have been altered to increase their targeting specificities, such as their length, secondary structure, or chemical composition. However, it is important to consider their on-target activity at the same time [75]. In general, there are several in silico tools which analyse target selection and specificity of ZFs [117], TALEs [62] and CRISPR-Cas platforms [118–128].

To overcome the limited specificity of CRISPR-SpCas9 systems, other Cas9 proteins have been investigated. This approach offers more flexibility in targeting sequences due to the requirement of different PAM sequences, the different size of the Cas9 orthologs as well as their specificity. The size of the Cas9 protein is particularly relevant for in vivo editing approaches due to the limited capacity delivery of well-established vectors, such as AAVs. Nevertheless, this limitation can be circumvented by the use of smaller Cas9 orthologs, such as those found in Staphylococcus aureus dCas9 (SaCas9), without compromising editing efficiencies [129].

The ability to use Cas9 proteins from different origins that are guided by their respective cognate sgRNAs in the context of their specific PAMs has enabled the simultaneous targeting of different loci within the same cell at the same time, without cross interference [130]. For example, class 2 type IV CRISPR nuclease from Prevotella and Francisella1 (Cpf1) (also known as Cas12a) recognizes 5ʹ-TTN-3ʹ PAM and uses only a short crRNA which displays RNase activity rather than a crRNA and a tracrRNA complex [131–133]. Cpf1 nucleases have been also isolated from Acidaminococcus sp. and Lachnospiraceae sp. and were proven to be very specific [134,135]. DNase dead Cpf1 has been also engineered for gene expression studies without any effector domain [136,137]. In addition to this Cas protein alternative, high-specificity SpCas9 variants have also been exploited [138,139].

Another way to investigate epigenetic editing specificity is to perform ChIP-seq, methylation assays, and DNase-seq. Thereby, binding locations of DNA binding domains, changes in epigenetic marks, or chromatin accessibility can be monitored for each platform [28,72,94,95,113]. Furthermore, an increasing number of studies showed that it may be beneficial to use inducible systems to improve specificity and decrease off-targets while simultaneously offering better testing of the epigenetic alteration stability [140]. These third-generation systems may be controlled by drugs at post-transcriptional level, drug induced dimerization, conformation recovery, nuclear localization, protein dimerization, light, temperature, or another protein [33,141,142]. The introduction of a temporal and spatial control provides a quantitative analysis of the kinetics and dynamics of epigenome establishment, remodelling and maintenance [33,143].

Concerning editing longevity, it remains unclear why some target sites work better with certain editing engineered tools. Nonetheless, the expression levels of these editing domains influence the potency and duration of epigenetic editing [48,66,95,104]. To increase potency, the use of multiple effector domains in different epigenetic pathways may bring a synergistic effect [89,91] and constitute the most reliable way to create long-lasting epigenetic memory [28].

Chromatin accessibility

It was already established that chromatin microenvironment, as well as the requirement of histone PTM crosstalk, greatly influences epigenetic reprogramming, highlighting the importance of chromatin accessibility [29,144] .

The three epigenetic editing systems respond differently to chromatin organization. Whereas ZFs depict high binding affinity to CG rich sequences and are able to edit hypermethylated DNA regions [29,45,47,145], CRISPR-Cas technique is reported to access hypermethylated regions with more difficulty [29,144]. If this system is, in fact, hampered to access hypermethylated regions, this is a significant limitation for epigenome editing. Concerning TALEs, studies are controversial. Their binding was severely harmed in hypermethylated regions in some studies [64,146], whereas in others they could bind to highly methylated DNA regions [113,147].

Design and delivery

Both ZFs and TALEs require the design and synthesis of a new protein every time a new target is chosen, which is expensive and labour-intensive [148]. The advantage of CRISPR-Cas system is that it constitutes a much simpler RNA-based DNA recognition approach which only requires a sgRNA and might be easily designed and delivered with the same dCas9 protein. This explains why CRISPR-Cas technology has been adopted so fast in comparison to ZFs and TALEs. The construction of new sgRNA requires only short oligonucleotides carrying the crRNA sequence, which may be easily obtained through a commercial synthesis service. Moreover, this platform allows for multiplexing and high-throughput studies, providing simultaneous activation or repression of different genes [149,150]. However, since sgRNAs vary in efficacy, it is advised to test multiple sgRNAs and select the most efficient.

Due to the limited number of efficient and safe delivery methods, several delivery methods have been tested, including physical administration, viral vector delivery, and particle-mediated delivery (Table 1). Of all aforementioned techniques, the nanoparticle delivery systems provide safety in living organisms and target the desired cells with high specificity while constituting, probably, the most promising delivery method.

Table 1.

Advantages and limitations of different delivery systems

| Delivery system | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | |||

| Microinjection | Usually well controlled, efficacy in delivery into cell of interest | Time-consuming, difficult and requires expertise, usually in vitro | [234,235] |

| Electroporation | High efficacy, delivery to cell population, suitable for any cell type | Non-specific transfection | [235,236] |

| Hydrodynamic delivery | Virus-free, low cost, easy technique, suitable for in vivo experiments in small animals | Non-specific, traumatic to tissues, not suitable for clinical applications | [235,236] |

| Induced Transduction By Osmocytosis And Propanebetaine (iTOP) | Virus-free, high efficacy | Lower efficacy in primary cells, only reported in vitro | [235,237] |

| Viral vector | |||

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | High infection efficacy, minimal immunogenicity | Packaging constraints | [234,235] |

| Lentivirus (LV) | High infection efficacy, persistent gene expression, large packing size | Gene rearrangement, transgene silencing | [235,238] |

| Adenovirus (AdV) | High infection efficiency | Immunogenicity, difficult to scale-up | [239] |

| Particle-mediated | |||

| Dendronised polymers | High efficacy, non-toxic | Highly controlled synthesis | [240] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LPNs) | Virus-free, low cost, simple manipulation | Low delivery efficiency due to endolysosomal degradation | [235,241–243] |

| Liposome Protamine RNA (LPR) | Low immune stimulation, multiple different ligands delivered to several cell types | More toxic in vivo | [242,243] |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides (CPPs) | Virus-free, delivers intact proteins | Variable penetrating efficiency, Chemical conjugation is needed | [235,244] |

| DNA Nanoclew | Virus-free | Need template DNA modifications | [245] |

| Nanoblades | Simple, inexpensive, suitable for in vivo, high efficacy | Short time frame | [246] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Inert, Membrane-fusion-like delivery | Non-Specific inflammatory response | [247] |

| Multistage Delivery Nanoparticles (MDNPS) | Suitable for in vivo experiments, good efficiency, present different surface properties at different delivery stages |

Loading capacity is limited | [248,249] |

Immunogenicity, safety, and ethical issues

Epigenome editing must be performed with minimal toxicity and immunogenicity. Overall, ZF proteins are thought to bind to several target sites, leading to gene regulation and phenotype switching at unwanted sites, constituting unpredicted off-target effects a limitation of this editing tool. Nevertheless, the addition of effector domains to ZFs might increase off-targets binding overall, even in non-promoter regions [56]. Several studies have described some techniques that decrease ZF’s cytotoxicity. For instance, targeted changes within ZF’s dimer promotes robust homologous recombination, reducing off-target cleavage and diminishing toxicity [151]. Additionally, small molecule regulation of ZF protein expression has also demonstrated to reduce its toxicity [152].

CRISPR-Cas systems are protein complexes derived from bacteria and archaea and, in fact, some of them are present in common infectious agents affecting humans. Several studies have described immunogenic properties of gene-editing components, highlighting the necessity of studying risk associations with immune responses against Cas proteins in clinical trials [75]. Therefore, anti-CRISPR proteins are being used to inhibit the CRISPR system. For example, AcrIIA4 disrupts PAM sequence when Cas9 forms a complex with its sgRNA [153]. In contrast, owing to the similarity with mammalian transcription factors, ZFs are much less immunogenic [154].

The previously discussed limitations are the reason for the rare reports on successful targeted DNA methylation of endogenous genes in vivo. More recently, however, a group developed three different methods using SunTag-dCas9 system recruiting GFP-TET1 protein, that were able to successfully demethylate H19 and Igf2 using mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or fertilized eggs [155].

In this context, the main ethical concern lies in the boundary between a therapy that corrects a disorder and an intervention that enhances human activity. Indeed, editing tools’ impact on ethics, society, and environment has been intensively discussed concerning genome-editing. Although epigenetic alterations are much less invasive, they are also under scrutiny [156].

Epigenetic alterations in PCa

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most commonly diagnosed non-cutaneous malignancy and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death among men, worldwide [157]. Currently, more than 80% of PCa cases are diagnosed as localized disease [158–160], but up to one third of these patients recur, entailing the need for androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) [159,160]. Despite initial response to ADT, patients soon become resistant and progress to an aggressive disease state, castration-resistant PCa (CRPC), within 12–30 months [159,161,162]. Unfortunately, there are no curative therapies available for those patients [163].

Besides the well-known genetic alterations, epigenetics is nowadays considered key to the molecular pathogenesis of PCa. Recent studies estimated that approximately 15%-20% of PCa harbour genetic mutations in epigenetic machinery components’ genes [164]. Conversely, the accumulation of these epigenetic alterations eventually promotes genetic instability. Thus, genetic and epigenetic alterations contribute, both individually and collectively, to pathogenesis and progression of PCa. Although the inevitable progression to CRPC cannot be attributed to a single mechanism, alterations in androgen receptor (AR) are important drivers of this phenomenon. Remarkably, the interaction between AR pathways and other signalling pathways can be influenced by epigenetic mechanisms, in which these pathways’ proteins modify epigenetic proteins and vice-versa [165]. For instance, c-Myc amplification has been shown to provide androgen-independent growth in PCa cells. Interestingly, its overexpression in CRPC might induce chromatin reprogramming [166]. Of note, comparatively to primary PCa or benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH), CRPC tissues display chromatin in a more open conformation. Interestingly, this chromatin patterns were very similar between primary PCa and BPH, indicating that chromatin reprogramming occurs mostly during acquisition of therapy resistance and/or CRPC progression [166].

DNA methylation

Altered DNA methylation occurs in 70% or more of PCa cases, compared to normal prostate [164]. Hundreds of genes involved in different pathways such as hormonal response, tumour cell invasion, metastasis, cell cycle control, apoptosis, and DNA damage repair reportedly disclose hypermethylated promoters in PCa [165]. This is the case of TSG glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP1), Ras association domain family protein 1 isoform A (RASSF1) and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) [164] (Table 2). Indeed, GSTP1 hypermethylation is demonstrated in more than 90% of PCa cases regardless of disease stage [167]. DNMTs expression and activity are also elevated in primary PCa as well as in the CRPC phenotype [168].

Table 2.

Epigenetic alterations in prostate cancer

| DNA methylation | Alteration in PCa | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| APC | Hypermethylated | [164] | |

| DNMTs | DNMTs expression and activity are elevated in PCa tumours as well as in CRPC phenotype | [168] | |

| FASN | Hypomethylation in 9% of PCa patients; promotes its tumorigenesis | [174] | |

| GSTP1 | Hypermethylated in more than 90% of PCa cases | [164,167] | |

| PLAU | Significantly methylated in early-stage and benign PCa, while it gets demethylated in highly invasive malignant cells; promotes aggressive phenotype of PCa cells | [172,173] | |

| PRDM10 | Hypomethylated in 7% of PCa patients, being overexpressed and leading to tumour development; functions as a transcriptional cofactor recruiting histone-modifying enzymes to target promoters | [174] | |

| RASSF1 | Hypermethylated | [164] | |

| HMTs | A.k.a. | ALTERATION IN PCa | REFERENCES |

| KMTs | |||

| ASH1L | KMT2H | Downregulated | [183] |

| DOT1L | KMT4 | Downregulated | [183] |

| EHMT1 | KMT1D | Downregulated | [183] |

| EZH2 | KMT6A | Its overexpression is associated with poorer outcomes; its expression is activated by the transcription factor E2F, but repressed by p53; Akt activation phosphorylates EZH2, which leads to the development and progression of highly aggressive PCa that are likely to resist standard therapies; Blocks nonprostatic differentiation | [189,250,251] |

| KMT2 | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| KMT5A | SETD8 | Downregulated | [183] |

| NSD1 | KMT3B | Downregulated | [183] |

| NSD2 | KMT3G | Upregulated in metastatic PCa; associated with biochemical recurrence; high levels are related to PSA | [187,188] |

| PRDM2 | KMT8A | Downregulated | [183] |

| SETD1A | KMT2F | Downregulated | [183] |

| SETD2 | KMT3A | Downregulated | [183] |

| SETD4 | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| SETD5 | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| SETD7 | KMT7 | Upregulated in malignant epithelial cells from PCa tissue; improves gene expression | [252,253] |

| SETDB1 | KMT1E | Upregulated; increases PCa cell migration and invasion; associated with the development of bone metastases | [181,182] |

| SMYD2 | KMT3C | Downregulated | [183] |

| SMYD3 | KMT3E | Upregulated; promotes cell migration and proliferation; its expression levels were an independent prognostic value for the prediction of disease-specific survival of PCa patients with clinically localized disease | [184,185] |

| SUV39H1 | KMT1A | Upregulated; increases PCa cell migration and invasion | [181] |

| SUV39H2 | KMT1B | Upregulated; interacts with AR, increasing androgen-dependent transcriptional activity | [183,184] |

| PRMTs | |||

| CARM1 | PRMT4 | Downregulated | [183] |

| PRMT3 | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| PRMT5 | - | Stimulates AR-targeted gene expression by arginine methylation; interacts with the transcriptor factor Sp1 | [254] |

| PRMT6 | - | Upregulated; its inhibition resulted in restored AR signalling, highlighting its oncogenic function | [183,255] |

| PRMT7 | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| HDMs | A.k.a. | ALTERNATION IN PCa | REFERENCES |

| KDMs | |||

| KDM2A | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| KDM2B | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| KDM3A | - | Regulates AR activity only in the presence of androgens; its silencing reduced the levels of ARV7 in PCa cells | [186,195,200] |

| KDM3B | - | Downregulated; CRPC growth is affected by KDM3B; acts independently of AR pathways | [183,202] |

| KDM4A | - | Modulates AR transcriptional activity by stimulating ligand-independent gene transcription; drives prostate carcinogenesis through transcription factor ETV1; positively correlates with aggressive PCa tumours | [186,195,199,202] |

| KDM4B | - | Act as AR coactivators | [194,195] |

| KDM4C | - | Forms a complex with AR, leading to transcription of androgen-dependent genes; associated with poorer outcome in primary PCa patients and prostate tumorigenesis | [195,198] |

| KDM5A | - | Upregulated | [183] |

| KDM5B | - | Upregulated; acts as an AR coactivator | [192,195] |

| KDM5C | - | Upregulated; predictive marker for therapy failure after prostatectomy | [195,196,200] |

| KDM5D | - | Downregulated; suppresses invasion and progression of PCa cells; Promotes PCa cell proliferation, migration, invasion and neuroendocrine differentiation; highly correlated with poor prognosis; Induced by hypoxia | [197] |

| KDM6A | - | Upregulated | [183] |

| KDM6B | - | Upregulated in metastatic PCa | [195,201] |

| KDM7A | - | Upregulated in enzalutamide resistant CRPC cell lines; its expression is correlated with PCa progression and GS | [195] |

| KDM8 | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| LSD1 | KDM1A | Upregulated; predictive marker for aggressive tumour biology and tumour recurrence during therapy; stimulates or represses AR transcriptional expression depending on promoter context; interacts with AR, promoting the transcription of AR target genes, increasing cell growth; acts as co-repressor by recruiting co-repressor complexes | [186,203–205] |

| PHF8 | KDM7B | Act as AR coactivators | [191,193,195,196] |

| RDMs | |||

| JMJD6 | - | Downregulated | [183] |

| HATs | A.k.a. | ALTERATION IN PCa | REFERENCES |

| p300 | KAT3A | Upregulated in PCa; associated with poor outcomes; it acetylates the AR, enhancing its transcriptional activity | [166,206] |

| HDACs | A.k.a. | ALTERATION IN PCa | REFERENCES |

| Class I | |||

| HDAC1 | Positively correlated with GS; downregulates AR; its expression correlated with tumour dedifferentiation |

[210,211,213] | |

| HDAC2 | Positively correlated with GS; high levels are associated with shortened patient relapse-free survival time in PCa | [210,213] | |

| HDAC3 | Its high levels might bring novel therapeutic studies in PCa | [213] | |

| Class II | |||

| HDAC6 | Acetylates HSP90, which leads to AR destabilization and consequent degradation | [214] | |

| HDAC7 | Downregulates AR | [212] | |

| Class III | |||

| SIRT1 | Interacts directly with AR, reduces its activity and regulates cellular growth through AR deacetylation | [207,208] | |

| SIRT2 | Downregulation of SIRT2 has been associated with poorer outcomes and decreased sensitivity to ADT | [209] | |

| OTHER HISTONE PTM | ALTERATION IN PCa | REFERENCES | |

| H2A.Zub | Reduces AR activity | [219] | |

| H2Aub1 | Lower in prostate tumours comparing to normal tissues | [217] | |

| H2Bub1 | Increased the transcription of the AR target genes, enhancing proliferation of PCa cells | [218] | |

| γ-H2AX | Identified in multiple PCa cell lines, recruiting important components for DNA damage repair and active checkpoint proteins for cell cycle arrest | [215] | |

| γ-H3T11 | Leads to increased androgen target gene activation | [216] | |

| EPIGENETIC READERS | ALTERATION IN PCa | REFERENCES | |

| BRD4 | Interacts with AR, facilitating its recruitment to its target site, increasing its target genes expression; contributes to aggressive phenotypes; Regulates MYC and AR; interacts with ERG, regulating genes that are upregulated in CRPC | [164,210,222] | |

| CHD1 | Mutated in 43% of advanced PCa; related with PCa aggressiveness | [223] | |

| TRIM24 | Upregulated in CRPC; contributes to proliferation of CRPC cells; acts as transcriptional activator of genes involved in cycle progression by interacting with AR; | [224] | |

Alternatively, DNA hypomethylation may also contribute to oncogenesis and cancer progression as it leads to genomic instability and mutation events [165]. Several studies indicate that DNA hypomethylation is more common in advanced and metastatic PCa, thus associating with the potential for disease dissemination [169–171]. For instance, urokinase plasminogen activator (PLAU) is hypothesized to promote an aggressive PCa phenotype [172]. Its promoter is significantly methylated at early-stage PCa, whereas demethylation occurs in highly invasive malignant cells [173]. Furthermore, both PRDM10, a putative recruiter of histone-modifying enzymes to target promoters, and fatty acid synthase (FASN) seem to promote tumour progression, being hypomethylated and overexpressed in 7% and 9% of PCa patients, respectively [174].

Histone modifications

Like methylation, changes in particular histone marks define the epigenetic profile of PCa, consequently altering critical signalling pathways which that contribute to carcinogenesis and cancer progression [165] (Table 1).

Di- and trimethylation of H3K9 and acetylation of H3 and H4 are significantly reduced in PCa whereas all H3K4 methylation states are upregulated in CRPC, correlating with clinicopathological parameters [175]. The H4K20me3 mark was identified in normal prostate, as well as in localized and metastatic hormone-naïve tumours. In contrast, CRPC displays low H4K20me1 and H4K20me2 levels, which correlated with lymph node metastases and Gleason score (GS), respectively [176]. Similarly to H4K20me2, H4R3me2 is also positively correlated with GS [177]. In addition to these marks, H3K27me1 and H3K27me3 correlate with aggressive tumour features [178,179] whereas H3K18ac was associated with an increased (threefold) risk of tumour relapse [180].

Histone alterations result mostly from changes in acetylases, deacetylases, methyltransferases, and demethylases. These alterations play an important role in prostate carcinogenesis and in the transcriptional regulation [175]. Several lysine (SUV39H1, SETDB1, SETD7, SUV39H2, SMYD3, and NSD2) and arginine (PRMT5 PMRT6) HMTs were found upregulated in PCa. SUV39H1 (KMT1A) and SETDB1 (KMT1E) both increase cell migration and invasion [181] and SETDB1 has been associated with the development of bone metastases [182]. SUV39H2 (KMT1B), PRMT5 and 6 were implicated in androgen-dependent transcriptional activity [183,184]. Moreover, SET and MYND domain-containing protein 3 (SMYD3)(KMT3E) promotes cell migration and proliferation and its expression levels disclose independent prognostic value for disease-specific survival of PCa patients with clinically localized disease [184,185]. The nuclear receptor binding SET domain protein 2 (NSD2)(KMT3G) seems to be a robust marker of lethal metastatic PCa [186] and its levels are positively correlated with those of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), the paramount indicator of biochemical recurrence [187,188].

In contrast, several HMTs were found to be downregulated in PCa tissues, such as KMT2 family, EHMT1 (KMT1D), PRDM2 (KMT8A), SETD5, ASH1L (KMT2H), KMT5A (SETD8), NSD1 (KMT3B), SETD1A (KMT2F), SETD4, PRMT7, SETD2 (KMT3A), PRMT3, CARM1 (PRMT4), DOT1L (KMT4), and SMYD2 (KMT3C) [183].

The most important HMTs involved in PCa is the methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) which has been also reported to be involved in AR signalling pathway. In PCa, its overexpression is associated with poorer outcome [189,190].

HDMs are also deregulated in PCa, being mostly upregulated. Multiple HDMs from the family of the Jumonji C domain-containing demethylases (JMJD) were demonstrated to play critical roles in PCa cell proliferation and survival [191]. KDM5B, KDM4B, and PHD-finger protein 8 (PHF8)(KDM7B) act as AR coactivators [192–194]. Along with PHF8 and KDM5B, KDM5C is overexpressed in PCa and may be used as a predictive marker for therapy failure after radical prostatectomy [195,196]. KDM5A and KDM6A are also overexpressed in PCa [183] and PHF8 promotes PCa cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and neuroendocrine differentiation. Its expression, induced by hypoxia, is correlated with poor prognosis [191,193]. In contrast, KDM5D is downregulated in PCa, since it suppresses invasion and progression [197]. Furthermore, KDM4C forms a complex with AR, leading to transcription of androgen-dependent genes. Thus, it is associated with prostate tumorigenesis and poorer outcome in primary PCa patients [195,198]. Furthermore, KDM4A also modulates AR transcriptional activity by stimulating ligand-independent gene transcription [195,199]. Alternatively, KDM3A, another putative oncogene functioning as AR coactivator, regulates AR activity only in the presence of androgens [195,200]. KDM7A expression is correlated with PCa progression and GS in tissue samples. Finally, KDM6B is upregulated in metastatic PCa [201]. Contrarily, KMD8, KDM2A, KDM2B, and JMJD6 are downregulated in PCa tissues [183]. Although KDM3B is also downregulated in PCa [183], a more recent study suggested that CRPC growth is affected by KDM3B which acts independently of AR pathways [202].

LSD1 (KDM1A), an important enzyme that is involved in AR regulation and PCa progression, deserves a special note since it can stimulate or repress AR transcriptional expression depending on promoter context [203,204]. LSD1 interacts with AR, promoting the transcription of AR target genes, increasing cell growth [203]. Because it is significantly overexpressed in CRPC, it may be a predictive biomarker of aggressive PCa and tumour recurrence during therapy [186,205]. Conversely, it may act as co-repressor by recruiting co-repressor complexes [204].

HATs and HDACs also contribute to epigenetic alterations in PCa. For instance, p300 (KAT3A) is overexpressed in PCa and associates with poor outcome [166], which may be due to acetylation-mediated increase of AR transcriptional activity [206]. Conversely, several HDACs inhibit AR activity through deacetylating. For example, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) interacts directly with AR, reduces its activity and consequently regulates cellular growth through AR deacetylation [207,208]. Furthermore, downregulation of SIRT2 has been associated with poorer outcome and decreased sensitivity to ADT [209]. Generally, HDACs levels are elevated in PCa, especially in advanced stage tumours. Specifically, HDAC1 and HDAC2 are positively correlated with GS [210]. Also, HDAC1 and HDAC7 down-regulate AR [211,212]. Another study demonstrated that novel therapeutics might be developed due to high percentage of PCa overexpressing HDAC3 [213]. Lastly, HDAC6 acetylates HSP90, which leads to AR destabilization and consequent degradation [214].

Besides methylation and acetylation, other types of histone modifications have also been reported in PCa. Phosphorylation of histone variant H2AX at Ser139 has been identified in multiple PCa cell lines, leading to recruitment of important components for DNA damage repair and active checkpoint proteins for cell cycle arrest [215] whereas phosphorylation of H3T11 leads to increased androgen target gene activation [216]. Apart from phosphorylation, monoubiquitination of H2A is lower in PCa compared to normal tissues [217]. Differently, monoubiquitination of H2B at K120 increased transcription of AR target genes, consequently enhancing proliferation of PCa cells [218] whereas ubiquitination of histone variant H2A.Z reduces AR activity [219].

Chromatin Readers

More than 50% of primary and metastatic PCa disclose genomic alterations in bromodomain-containing proteins (chromatin readers) [220]. H3ac colocalizes with AR binding sites and, thus, epigenetic regulatory proteins that can read this mark are capable of regulating the transactivation of the androgen-responsive genes [221]. For example, the bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4), which interacts with acetylated histones, binds with high affinity to AR, facilitating its translocation into the nucleus and recruitment to target sites (Table 1). Thereby, it increases AR target genes’ expression and contributes to more aggressive phenotypes of PCa cells [222]. It is also reported that BRD4 regulates MYC and AR itself [164] and that it interacts with ERG, thereby regulating the expression of common target genes which are upregulated in CRPC [210].

Another example is the chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 1 (CHD1) which is mutated in 43% of advanced PCa and whose loss is associated with tumour aggressiveness [223]. Finally, TRIM24, another epigenetic reader upregulated in the transition from primary PCa to CRPC, contributes to CRPC cell proliferation. It acts as a transcriptional activator of genes involved in cycle progression by interacting with AR pathway [224].

Epigenetic editing tools in PCa

Since the epigenetic machinery is involved in multiple steps of cancer development and progression, several epigenetic drugs have been investigated as anti-cancer agents. However, they remain mostly ineffective for the treatment of solid tumours, including PCa. Since these drugs typically lack location-specificity, having a broad therapeutic spectrum, it is challenging to determine at which site the modification occurs, and, subsequently, which one is responsible for the phenotypic or functional alterations. Consequently, the study of their pharmacological behaviour, potency, and side effects become more difficult to explore. In addition, most of the epigenetic enzymes’ functions remain unclear. Moreover, considering the heterogeneous nature of PCa, the effect of a particular epigenetic mark might be variable from case to case and context-dependent. Thus, development of target-specific epigenetic drugs is mandatory for clinical use, which until now has been unsuccessful. Hence, it is important to develop more targeted approaches to fully understand the molecular interaction between epigenetic mechanisms and the development and progression of PCa. Specifically, it is of paramount importance to understand in depth not only the roles of these epigenetic modifications in transcription regulation, but also their precise interaction with other epigenetic marks and other signalling pathways. In this context, epigenome editing tools might allow to unravel these epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, as well as their contribution to PCa development and progression in a more precise manner [165].

It has been already demonstrated that AR overexpression initiates a positive feedback loop, consequently increasing the chromatin accessibility to AR and other transcript factors in CRPC, activating several oncogenes, leading to tumour growth and therapy resistance. Hence, these chromatin alterations may be considered a determinant contributor to PCa progression. In this respect, a recent study using dCas9-KRAB fusion demonstrated that repression of putative AR enhancer leads to a decrease in AR transcript. Importantly, this AR enhancer becomes activated in CRPC, leading to desensitization of cancer cells to ADT. This study demonstrated that dCas9-KRAB decreased H3K27ac levels, highlighting once again that dCas9-KRAB transcriptional regulation might be linked to other, largely unexplored, epigenetic mechanisms [225].

Furthermore, epigenetic editing might bring novel strategies by targeting other signalling pathways or even revert several alterations driven by therapy resistance/adaptation [166]. For example, AR overexpression, which has been documented in more than 50% of CRPC patients [226], could be restrained with a methylating or deacetylating effector. Alternatively, the subgroup of patients with epigenetically silenced AR could be targeted using this editing approach, resulting in a reversion of CRPC. In this way, they would be re-sensitized to the already available AR-targeted therapies.

Epigenetic editing tools can modulate the expression of oncogenes and TSG, but also of genes that contribute to cancer onset and progression. Apart from AR, one of the most frequent altered genes in CRPC is the tumour suppressor gene phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is lost in 40% of CRPC cases [227]. One study demonstrated that both TSG RASSF1 and PTEN hypermethylation by dCas9-DNMT3a-DNMT3L prevents gene expression changes associated with senescence in cells isolated from reduction mammoplasty tissue [228]. Therefore, methylation reversal tools such as dCas9-TET1 could be used in PCa to activate senescence. Additionally, designed chimeric TALE (dTALE) epigenetic tool was also demonstrated to control PCa metastasis, a major cause for patients’ disease progression and therapy-resistance. Remarkably, demethylation of the metastasis suppressor gene CRMP4 through dTALE-TET1 in metastatic PC-3 cells abolished metastasis in multiple organs. Conversely, CRMP4 methylation via dTALE-DNMT3A in non-metastatic 22Rv1 cells induced metastasis [229]. Thus, altering gene expression through locus-specific modification of gene promoter can be achieved with dTALEs, consequently being a potential new approach for disease metastasis modulation.

Concerning chemotherapy resistance, re-expression of the TSG Par4 in recurrent breast cancer using dCas9-p300 sensitized these tumours to chemotherapy, both in vitro and in vivo [230]. This TSG regulates autophagy, senescence, as well as metastasis and induces apoptosis selectively in cancer cells [231]. Therefore, by re-expressing Par4 in PCa through an epigenome editing approach, chemotherapy resistance might be overpassed by sensitizing prostate tumour cells to apoptosis [232].

Finally, from a clinical point of view, reprogramming the epigenetic landscape requires a long-lasting effect. Epigenetic editing tools were already used to re-express FMR1 in fragile X syndrome. Indeed, the introduction of a fusion dCas9-TET1 targeting the CGG repeats of FRM1 resulted in an 85% methylation decrease, which was enough to reactivate the gene. Nevertheless, this re-expression only lasted two weeks [233]. Hence, several epigenetic effectors might need to be targeted simultaneously in a locus-specific way to re-write the epigenetic mark in a more stable and, consequently, long-lasting manner [29,30]. This also implies that although this tool might be explored in the clinical field, it would need to be applied periodically to maintain the methylation reversion [233]. This evanescent effect is one of the major hurdles that epigenetic editing tools face in the translation to clinical practice.

Conclusions

Gene expression reprogramming might be achieved by targeted epigenetic editing of locus-specific sites via several DNA-binding platforms. Unravelling epigenetic mechanisms as well as improved understanding of their causal relationship with gene expression has brought progress to this field. Nevertheless, continued efforts are required to overcome some limitations concerning specificity and off-target effects, efficacy, routine implementation, and longevity. Despite the previously described limitations, these platforms are rapidly progressing and improving.

Since PCa is characterized by multiple genetic and epigenetic alterations which contribute both individually and collectively to pathogenesis and progression, epigenetic editing constitutes a promising strategy. In addition, these modifications influence strongly the other deregulated pathways in this disease. Hence, by modulating chromatin structure through epigenome editing, we can not only better understand its conformation, but also predict and order events that drive to PCa development and progression. Hence, we may assess whether these epigenetic alterations take part in the causal mechanisms that lead to PCa or are simply transient events. Furthermore, a better understanding of the epigenetic mechanisms involved in PCa initiation and progression will certainly allow for development of novel therapeutic strategies that target the epigenetic processes.

Funding Statement

CJ research is supported by Programa Operacional Competitividade e Internacionalização (POCI), in the component FEDER, and by national funds (OE) through FCT/MCTES, in the scope of the project HyTherCaP- POCI-01-0145-FEDER-29030 (PTDC/MECONC/29030/2017). The HyTherCaP project is also acknowledged for VC Junior Researcher position. MBP was supported by a fellowship from Liga Portuguesa Contra o Cancro-Núcleo Regional do Norte.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1] .Waryah CB, Moses C, Arooj M. et al. Zinc Fingers, TALEs, and CRISPR Systems: a comparison of tools for epigenome editing. Methods Mol Biol. Epigenome Editing. 2018; 19–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Allis CD, Jenuwein T.. The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nat Genet. 2016;17(8):487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kanwal R, Epigenetic GS. Epigenetic modifications in cancer. Clin Genet. 2012;81(4):303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA, et al. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):27–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jerónimo C, Bastian PJ, Bjartell A, et al. Epigenetics in prostate cancer: biologic and clinical relevance. Eur Urol. 2011;60(9):753–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yong WS, Hsu FM, Chen PY, et al. Profiling genome ‑ wide DNA methylation. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2016;9(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5- methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcyto-sine. Science. 2011;333(6047):1300–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lavender P, Kelly A, Hendy E, et al. CRISPR-based reagents to study the influence of the epigenome on gene expression. J Transl Immunol. 2018;194:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Youn H. Methylation and demethylation of DNA and histones in chromatin: the most complicated epigenetic marker. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(4):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rothbart SB, Strahl BD. Interpreting the language of histone and DNA modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839(8):627–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Henikoff S, Shilatifard A. Histone modification: cause or cog? Trends Genet. 2011;27(10):389–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Turner BM. The adjustable nucleosome: an epigenetic signaling module. Trends Genet. 2012;28(9):436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, et al. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature. 2004;429(6990):457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Verhoef G, Bosly A, Ravoet C, et al. Low-dose 5-aza-2ʹ-deoxycytidine, a DNA hypomethylating agent, for the treatment of high-risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome : a multicenter Phase II study in elderly patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(5):956–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Issa JJ, Garcia-manero G, Giles FJ, et al. Phase 1 study of low-dose prolonged exposure schedules of the hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2ʹ-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood J. 2013;103(5):1635–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kaminskas E, Farrell A, Abraham S, et al. Approval summary: azacitidine for treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(10):3604–3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Issa JJ, Rosenfeld CS, Ph D, et al. Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes results of a phase iii randomized study. Cancer. 2006;106(8):1794–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mann BS, Johnson JR, Cohen MH, et al. FDA approval summary: vorinostat for treatment of advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncologist. 2007;12(10):1247–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Whittaker SJ, Demierre M, Kim EJ, et al. Final results from a multicenter, international, pivotal study of romidepsin in refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4485–4491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Poole RM. Belinostat: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74(13):1543–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Moore D. Panobinostat (Farydak) a novel option for the treatment of relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Pharm Ther. 2016;41(5):296–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ganesan A, Arimondo PB, Rots MG, et al. The timeline of epigenetic drug discovery : from reality to dreams. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11(1):1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bauman J, Verschraegen C, Belinsky S, et al. A phase I study of 5-azacytidine and erlotinib in advanced solid tumor malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69(2):547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thibault A, Fig WD, Bergan RC, et al. A Phase II study of 5-Aza-2ʹDeoxycytidine (Decitabine) in hormone independent metastatic (D2) prostate cancer. Tumori. 1998;84(1):87–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Azad N, Zahnow CA, Rudin CM, et al. The future of epigenetic therapy in solid tumours — lessons from the past. Nat Rev Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2013;10(5):256–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].De GML, Verschure PJ, Rots MG, et al. Epigenetic editing: targeted rewriting of epigenetic marks to modulate expression of selected target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(21):10596–10613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27] .Rots MG, Jeltsch A. Editing the epigenome: overview, open questions, and directions of future development. In: Epigenome Editing - Methods and Protocols; 2018: 3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Amabile A, Migliara A, Capasso P, et al. Inheritable silencing of endogenous genes by hit-and-run targeted epigenetic editing. Cell. 2016;167(1):219–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cano-rodriguez D, Gjaltema RAF, Jilderda LJ, et al. Writing of H3K4Me3 overcomes epigenetic silencing in a sustained but context-dependent manner. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mlambo T, Nitsch S, Hildenbeutel M, et al. Designer epigenome modifiers enable robust and sustained gene silencing in clinically relevant human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(9):4456–4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Geen HO, Bates SL, Carter SS, et al. Ezh2‑dCas9 and KRAB‑dCas9 enable engineering of epigenetic memory in a context‑dependent manner. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2019;12(26):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gjaltema RAF, Huisman C, Brouwer U, et al. KRAB-induced heterochromatin effectively silences PLOD2 gene expression in somatic cells and is resilient to TGFβ1 activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10):1–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhao W, Wang Y, Liang F-S, et al. Chemical and light inducible epigenome editing. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Durai S, Mani M, Kandavelou K, et al. Zinc finger nucleases: custom-designed molecular scissors for genome engineering of plant and mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(18):5978–5990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Najafabadi HS, Mnaimneh S, Schmitges FW, et al. C2H2 zinc finger proteins greatly expand the human regulatory lexicon. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):555–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Moore M, Klug A, Choo Y, et al. Improved DNA binding specificity from polyzinc finger peptides by using strings of two-finger units. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(4):1437–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Segal DJ, Beerli RR, Blancafort P, et al. Evaluation of a modular strategy for the construction of novel polydactyl zinc finger DNA-binding proteins†. Biochemistry. 2003;268(7):2137–2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Siddique AN, Nunna S, Rajavelu A, et al. Targeted methylation and gene silencing of VEGF-A in human cells by using a designed Dnmt3a–Dnmt3L single-chain fusion protein with increased DNA methylation activity. J Mol Biol [Internet]. 2013;425(3):479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Beerli RR, Dreier B, Iii CFB, et al. Positive and negative regulation of endogenous genes by designed transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97(4):1495–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Beltran A, Parikh S, Liu Y, et al. Re-activation of a dormant tumor suppressor gene maspin by designed transcription factors. Oncogene. 2007;53(19):2791–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Beltran AS, Russo A, Lara H, et al. Suppression of breast tumor growth and metastasis by an engineered transcription factor. PLoS One. 2011;6(9). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Beltran AS, Blancafort P. Reactivation of MASPIN in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) cells by artificial transcription factors (ATFs). Epigenetics. 2011;6(2):224–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Huisman C, Wisman GBA, Kazemier HG, et al. Functional validation of putative tumor suppressor gene C13ORF18 in cervical cancer by artificial transcription factors. Mol Oncol. 2013;7(3):669–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhang B, Xiang S, Zhong Q, et al. The p16- specific reactivation and inhibition of cell migration through demethylation of CpG Islands by engineered transcription factors. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23(10):1071–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Huisman C, MGP VDW, Falahi F, et al. Prolonged re-expression of the hypermethylated gene EPB41L3 using arti fi cial transcription factors and epigenetic drugs. Epigenetics. 2015;10(5):384–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Huisman C, Wijst MGPVD, Schokker M, et al. Re-expression of selected epigenetically silenced candidate tumor suppressor genes in cervical cancer by TET2-directed demethylation. Am Soc Gene Cell Ther. 2016;24(3):536–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chen H, Kazemier HG, De GML, et al. Induced DNA demethylation by targeting Ten-Eleven Translocation 2 to the human ICAM-1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(3):1563–1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hilton IB, D’Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):510–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Snowden AW, Gregory PD, Case CC, et al. Gene-specific targeting of H3K9 methylation is sufficient for initiating repression in vivo. Curr Biol. 2002;12(24):2159–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Falahi F, Huisman C, Kazemier HG, et al. Towards sustained silencing of HER2/neu in cancer by epigenetic editing. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11(9):1029–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cano-rodriguez D, Campagnoli S, Grandi A, et al. TCTN2: a novel tumor marker with oncogenic properties. Oncotarget. 2017;8(56):95256–95269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Stolzenburg S, Beltran AS, Swift-Scanlan T, et al. Stable oncogenic silencing in vivo by programmable and targeted de novo DNA methylation in breast cancer. Oncogene [Internet]. 2015;34(43):5427–5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rivenbark AG, Stolzenburg S, Beltran AS. et al. Epigenetic reprogramming of cancer cells via targeted DNA methylation. Epigenetic Cancer Ther. 2012;7(4):350–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Li F, Papworth M, Minczuk M, et al. Chimeric DNA methyltransferases target DNA methylation to specific DNA sequences and repress expression of target genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(1):100–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Song XJ, Cano-rodriquez D, Winkle M, et al. Targeted epigenetic editing of SPDEF reduces mucus production in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312(3):334–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Grimmer MR, Stolzenburg S, Ford E, et al. Analysis of an artificial zinc finger epigenetic modulator: widespread binding but limited regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(16):10856–10868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Boch J, Bonas U. Xanthomonas AvrBs3 Family-Type III effectors: discovery and function. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48(1):419–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kay S, Hahn S, Marois E, et al. A bacterial effector acts as a plant transcription factor and induces a cell size regulator. Science. 2007;318(5850):648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Jankele R, Svoboda P. TAL effectors: tools for DNA targeting. Brief Funct Genomics. 2014;13(5):409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Boch J, Scholze H, Schornack S, et al. Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-Type III effectors. Science. 2009;326(5959):1509–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Deng D, Yin P, Yan C, et al. Recognition of methylated DNA by TAL effectors. Cell Res. 2012;22(10):1502–1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rogers JM, Barrera LA, Reyon D, et al. Context influences on TALE-DNA binding revealed by quantitative profiling. Nat Commun. 2015;6(7440):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Grau J, Wolf A, Reschke M, et al. Computational predictions provide insights into the biology of TAL effector target sites. Plos Comput Biol. 2013;9(3):1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bultmann S, Morbitzer R, Schmidt CS, et al. Targeted transcriptional activation of silent oct4 pluripotency gene by combining designer TALEs and inhibition of epigenetic modifiers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(12):5368–5377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zhang F, Cong L, Lodato S, et al. Efficient construction of sequence-specific TAL effectors for modulating mammalian transcription. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(2):149–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Maeder ML, Angstman JF, Richardson ME, et al. Targeted DNA demethylation and endogenous genes activation using programmable TALE-TET1 fusions. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;31(12):1137–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lo C, Choudhury SR, Irudayaraj J, et al. Epigenetic editing of Ascl1 gene in neural stem cells by optogenetics. Sci Rep. 2017;7(12):1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bernstein DL, Le LJE, Ruano EG, et al. TALE-mediated epigenetic suppression of CDKN2A increases replication in human fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):1998–2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, et al. Optical control of mammalian endogenous transcription and epigenetic states. Nature. 2013;500(7463):472–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cho H, Kang JG, Lee J, et al. Direct regulation of E-cadherin by targeted histone methylation of TALE-SET fusion protein in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27). DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Cong L, Zhou R, Kuo Y, et al. Comprehensive interrogation of natural TALE DNA binding modules and transcriptional repressor domains. Nat Commun. 2012;3(1):1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Mendenhall EM, Williamson KE, Reyon D, et al. Locus-specific editing of histone modifications at endogenous enhancers. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(12):1133–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;11(3):181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Garneau JE, M-È D, Villion M, et al. The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature. 2010;468(7320):67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Broeders M, Herrero-hernandez P, Ernst MPT, et al. Sharpening the molecular scissors: advances in gene-editing technology. iSCIENCE. 2020;23(100789):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, et al. DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nat. 2014;507(7490):62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, et al. A programmable dual RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Mojica FJM, et al. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18(2):67–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339(6121):823–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ghasemi S. Cancer’s epigenetic drugs: where are they in the cancer medicines ? Pharmacogenomics J. 2019. DOI: 10.1038/s41397-019-0138-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, et al. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-Guided Platform for SequenceSpecific Control of Gene Expression. Cell. 2013;152(5):1173–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Rahman MM, Tollefsbol TO. Targeting cancer epigenetics with CRISPR-dCAS9: principles and prospects. Methods. 2020;187:77–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Maeder ML, Linder SJ, Cascio VM, et al. CRISPR RNA – guided activation of endogenous human genes. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):977–981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Cheng AW, Wang H, Yang H, et al. Multiplexed activation of endogenous genes by CRISPR-on, an RNA-guided transcriptional activator system. Cell Res. 2013;23(10):1163–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Balboa D, Weltner J, Eurola S, et al. Conditionally stabilized dCas9 activator for controlling gene expression in human cell reprogramming and differentiation. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5(3):448–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA- guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2014;154(2):442–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Chakraborty S, Ji H, Kabadi AM, et al. A CRISPR/Cas9-based system for reprogramming cell lineage specification. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3(6):940–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Chavez A, Scheiman J, Vora S, et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated transcriptional programming. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):326–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, et al. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):833–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nat. 2014;517(7536):583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Garcia-bloj B, Moses C, Sgro A, et al. Waking up dormant tumor suppressor genes with zinc fingers, TALEs and the CRISPR/dCas9 system. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):60535–60554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Tanenbaum ME, Gilbert LA, Qi LS, et al. A protein-tagging system for signal amplification in gene expression and fluorescence imaging. Cell. 2015;159(3):635–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]