Abstract

Financial strain is one hardship faced by female survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) that is often overlooked. This paper examined the relationships between multiple forms of abuse—with a focus on economic abuse—and financial strain. Guided by stress process model, this study tested two hypotheses: (1) economic abuse is associated with financial strain more than other types of IPV; and (2) decreased economic abuse relates to financial strain over time. The study sample consists of 229 female IPV survivors who participated in a longitudinal, randomized controlled study evaluating an economic empowerment curriculum. Results from regression models suggest that physical abuse and economic abuse were significantly and positively associated with the magnitude of financial strain. Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition was used to partition the mean differences of financial strain over time that was mainly attributed to the decrease in economic and physical abuse (78%). Particularly, the decrease of economic abuse contributed to over half (58%) of the decrease in financial strain over time. Advocates should assess survivors’ risk of economic abuse, evaluate financial strain, and utilize financial safety planning skills to help survivors build economic security and independence. In addition, policy makers should address issues concerning economic security among female IPV survivors.

Keywords: Economic abuse, Financial strain, Female survivors of intimate partner violence, Stress process model, Decomposition analysis

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is an epidemic that affects millions of Americans as one in three U.S. women experience IPV in their lifetime (Smith et al., 2017). IPV is well documented to negatively impact the physical and mental health of survivors (Oram et al., 2017); recently researchers have been examining the consequences of IPV on survivors’ economic well-being (Adams et al., 2013; Resko, 2010). Women’s experiences of IPV and financial hardship are intertwined with economic inequality, but often overlooked in studies. The term "financial strain" is a ubiquitous form of general stress (American Psycological Association, 2015,2017), but financial strain that commonly befalls female IPV survivors has not been acknowledged and sufficiently researched.

Financial strain is defined as an individual perception of not knowing how to make ends meet (Gutman et al., 2005). Such a definition in reality is crucial to the survival of IPV victims. Women in general, are more likely to experience financial hardship than men, and live with economic hardship for a longer period of time (Tucker & Lowell, 2016). Women also experience higher levels of financial strain resulting in physical complaints and poor psychological well-being (Drentea & Reynolds, 2014; Frank et al., 2014); in turn, causing further economic gender disparity (Ahnquist et al., 2007). Financial strain serves as an indicator of financial wellbeing (Hacker et al., 2014), but is less likely to be linked to women's economic welfare in IPV studies.

Financial difficulties trap women in relationships because they become economically dependent on their abusive partners (Kim & Gray, 2008). Male perpetrators use different forms of abuse to manipulate and control female survivors; the majority of IPV studies primarily focus on physical, psychological, and sexual abuse (Barrios et al., 2015; Beydoun et al., 2017; Whitehead & Bergeman, 2017; Yick, 2000). Currently, research on economic abuse is emerging and has established this behavior as another tactic used by abusers to trap women in relationships (Postmus et al., 2020). Research shows that experiencing IPV harms women economically (Adams et al., 2013); however, no study has precisely examined how different types of IPV impact their financial well-being differently, such as physical, psychological, or economic abuse. Assessing the associations between specific forms of IPV and financial strain is crucial to identify effective intervention and prevention.

Given the significant overlap of IPV and financial strain, this study examines the associations between IPV and financial strain with data collected from a sample of female IPV survivors. In particular, one unique contribution of this study is the examination of economic abuse, considered to be an invisible form of IPV (Postmus et al., 2020) and financial strain. Economic abuse is considered to account for financial well-being more than other forms of IPV due to the nature of economic interference (Postmus et al., 2012). Financial strain of IPV survivors may be impacted by their experience of economic abuse based on similar financial concerns; however, the relationship between economic abuse and financial strain has not been tested. Another unique contribution of this study is the examination of the relationship between economic abuse and financial strain over a period of time.

Few studies emphasize the form of economic abuse on financial well-being. Guided by stress theory, this study tests the impact of IPV on financial strain, and decomposes the components of economic consequences that female IPV survivors face. The specific aims of this paper are (1) to examine the relationship between financial strain and different types of abuse (i.e., physical abuse, psychological abuse, sexual abuse, and economic abuse). Given the common economic nature of economic abuse and financial strain, the expectation is that economic abuse would be more positively related to financial strain than other forms of IPV at the baseline; (2) to analyze contributing factors determining change of financial strain over time. Specifically, changing economic abuse contributes to the change in financial strain over time to a larger extent than other forms of abuse. More specifically, decreased economic abuse will decrease financial strain over time.

Literature Review

Stress Theory

The term “stress” is widely used in common language; moreover, there is an entire science of stress that documents its effect on the human brain, body, and mind (Fink, 2010). Hans Selye (1907–82), known as the “father of stress,” applied stress to biology and publicized the General Adaptation Syndrome (Selye, 1936). He first introduced the term “stressor” for the causative agent and “stress” for the reaction to stressor (Selye, 1976). The term stressor refers to any social event where individuals need to adopt major social readjustment (Rahe et al., 1964), specifically to change their accustomed patterns (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). Kaplan (1983) combined the concepts of stress from psychology and sociology, and used the term “psychosocial stress,” defined as “the socially deprived, conditioned, and situated psychological process that stimulate any or all of the many manifestations of dysphoric affect falling under the rubric of subjective distress (p. 196).” This definition of stress, integrating social structures and individual appraisal, echoes the dual focus of social work: individual well-being in a social context and the well-being of the society (National Association of Social Workers, 2017). Thus, the concept of stress expanded from biological reactions in physiology, and then became more sophisticated along with psychological appraisals and social conditions.

According to the stress theory, IPV can lead to financial strain or vice versa. The direction can be clarified while considering the role of perpetrators and survivors. For perpetrators, the IPV incidence may be an outcome of financial strain because they may actively use violence as a response to the accumulation of financial inadequacies (McKenry et al., 1995; Schwab-Reese et al, 2016). For survivors, the IPV experience is viewed as a stressor stimulus that affects their financial strain (Fox et al., 2004; Lagdon et al., 2014).

Stress Process Model

Stress is better understood as a process that consists of multiple elements and dynamic relationships. Pearlin and colleagues (1981) proposed the Stress Process Model to outline key components in the stress process: the stressors, the mediators, and the outcomes. The conceptual framework of multiple complex elements and their interconnections has been subsequently elaborated. Pearlin and colleagues (1981) developed two sources of stressors: one is “life events” adopted from Holmes and Rahe’s (1967) life change events; the other is “life strains” referring to some life event that turns out to be a long-term life strain.

To fully understand various forms of stressors, Wheaton (1996) developed the stress continuum by adding daily hassles, macro stressors, nonevents, and traumas. Daily hassles are defined as annoying problems or occurring demands that need behavior readjustment of daily life, such as traffic jams or financial concerns (Kanner et al., 1981). Macro stressors are stressors occurring at the macro-level system, i.e., natural disaster or economic recessions. Non-event stressors refer to lack of change or dissatisfaction; for example, being in a job position without promotion for a long time. Traumas are horrifying life experiences that impact deeply and need to be distinguished from regular stressors (Wheaton, 1996).

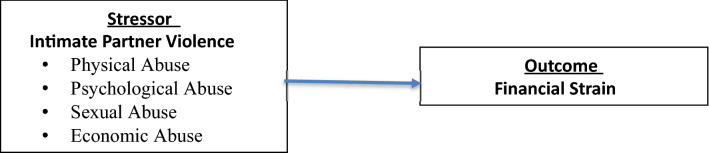

Female IPV survivors simultaneously experience different types of stressors that may affect their wellbeing and health. The stress continuum provides distinct information on intricate stressors and gives a framework for explanatory models. Thoits (1995) suggested that examining multiple stressors and their sequences help to specify the association between stress and health. In this study, the main variables, IPV and financial strain, are considered as stressors to IPV female survivors. IPV is viewed as sudden traumas or chronic stressors depending on the frequency of abuse. Financial strain is considered as a chronic stressor that exists continuously in daily life. This paper adopts the conceptual model (Fig. 1) to understand the relationship between different forms of IPV and financial strain among female survivors.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual model

Financial Strain

Financial strain is one of several stressors that American adults face. Some groups experience higher money-related stress levels than the general American population, such as women, younger Americans, low-income households, and parents of children under the age of 18 (American Psycological Association, 2015). As Thoits (2010) noted, the phenomenon that stress exposure is unequally distributed among different social groups accounts for health inequalities in physical and psychological well-being. Several factors contribute to the increase in financial strain, such as the worldwide economic recession, low savings, consumerism, and high levels of debt (Vosloo et al., 2014; Weller & Logan, 2009).

The term financial strain is widely used interchangeably with various synonyms, such as financial hardship (Azzani et al., 2015), financial stress (Åslund et al., 2014; Ryan, 2012), economic strain (Pearlin et al., 1981; Reeb et al., 2013), economic hardship (Pulgar et al., 2016), and perceived income adequacy (Dziak et al., 2010; Fahmy et al., 2016). The concept of financial strain is operationalized by objective and subjective measures, and can vary from a single question (Dziak et al., 2010) to scales (Aldana & Liljenquist, 1998). Objective measures include the debt-to-income ratio or income-to-needs ratio (Benson et al., 2003; Zimmerman & Katon, 2005). Subjective measures obtain self-reported perceptions of financial difficulties, such as income, paying bills, making ends meet or perceptions of difficulties (Tucker-Seeley et al., 2012; Valentino et al., 2014).

Financial strain is highly linked to socioeconomic status, including employment status, education, and income (Fatimah et al., 2012; Szanton et al., 2010; Zimmerman & Katon, 2005). In particular, low-income families persistently report high levels of financial strain over time (Ribar, 2005). Financial strain can also serve as a mediator between socioeconomic variables, such as income, employment and different outcomes, such as individual psychological distress (Valentino et al., 2014), marital quality (Lincoln & Chae, 2010), or child development (Masarik & Conger, 2017).

IPV and Financial Strain

Despite a substantial body of literature examining the impact of IPV on mental health (Devries et al., 2013; White & Satyen, 2015), research is only recently emerging that explores the consequence of IPV on financial well-being (Adams et al., 2013; Hartley & Renner, 2018; Sauber & O’Brien, 2017). Most available IPV research has primarily focused on economic self-sufficiency, defined as independence from public assistance and the ability providing basic needs for individuals and families (Gowdy & Pearlmutter, 1993). Using a sample of 147 low-income female IPV survivors, Sauber and O’Brien (2017) pointed out that economic abuse, not financial/work-related resource loss, was significantly associated with economic well-being. Goodman et al. (2010) have noted the fact that impoverished women tended to lack the choice or resources to fulfill their basic needs. Hence, using economic self-sufficiency as an indicator of economic well-being may fail to capture real-life financial concerns among low-income families (Sauber & O’Brien, 2017).

Financial resources are critical for IPV survivors to obtain financial independence (Postmus et al., 2012), but research shows that IPV continues to jeopardize women’s economic well-being after leaving an abusive relationship. Adams and colleagues (2013) randomly selected 503 single mothers who received temporary assistance for needy families (TANF), and conducted a longitudinal study over five years. Their study findings showed that women who were recently physically abused in the past two years reported more objective and anticipated material hardship than those who did not experience IPV. Surprisingly, the study participants whose IPV had ended within the prior three years also confronted significantly objective material hardship (Adams et al., 2013). As such research reveals the deleterious economic consequences of physical IPV, the question of how other types of IPV affect survivors’ economic well-being still remains.

More research is needed to explore other indicators of financial well-being among IPV survivors. The concept of economic self-sufficiency may not best fit the financial concerns among low-income populations due to the lack of resources (Goodman et al., 2009; Sauber & O’Brien, 2017). Fox and Chancey (1998) identified financial strain as the strongest predictor of individual and family well-being compared to other measures of economic distress, such as job instability and job insecurity. Adams (2011) suggested that financial stability and subjective financial well-being can be other dimensions to measure the impact of IPV on financial well-being.

Research has shown that financial strain is highly related to the risk of violence against women, predominately physical abuse (Benson et al., 2003; Copp et al., 2016; Fox et al., 2004; Friedan, 1995; Lucero et al., 2016). Fox et al. (2004) examined the impact of economic distress on the risk of domestic violence, and found that the partner’s job strain and financial inadequacy predicted a high risk of physical violence. Benson et al. (2003) found that subjective financial strain increased females’ likelihood of physical violence at a later time. Guided by the family stress model, Copp et al. (2016) confirmed that economic and/or career concerns, and material hardship increased the odds of physical IPV; accordingly, they suggested that interventions should target specific content of economic concerns among young adult couples instead of anger management. Using a sample of 941 women from fragile families and child well-being data, Lucero et al. (2016) found that women who experienced economic hardship had higher odds of experiencing physical and emotional IPV and such relationships persisted over nine years.

Although less recognized, economic abuse is a unique form of IPV (Postmus et al., 2020). Kutin et al. (2017) were the first researchers to link financial strain with economic abuse. Their findings indicated that women who experienced economic abuse reported high levels of financial stress when controlling for physical IPV and emotional IPV (Kutin et al., 2017). Similar results were shown in a sample of 340 Chinese women who reported financial strain associated with risks of experiencing husband’s financial control (Zheng et al., 2019). Both studies revealed the link between economic abuse and financial strain in the general population. Economic abuse is extremely high among IPV survivors as 94% and 99% of the IPV survivors have reported economic abuse (Adams, 2011; Postmus et al., 2012). However, no available studies examine the link between economic abuse and financial strain among only IPV survivors. This paper argues that the link is stronger among female IPV survivors.

Notably, financial strain can be viewed as the outcome of IPV as well. Using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health data, Strenio (2017) found that IPV victimizations increased the probability of reporting economic hardship and welfare assistance for both females and males in later life. Females who experienced high intensity IPV were more likely to face financial challenges compared to those who had low or no IPV experiences.

Several socio-demographic attributes have been connected to both IPV and financial strain among women. Age appears to have mixed impact on IPV experiences, as younger female veterans aged younger than 35 years were more likely to report IPV (Dichter et al., 2017) whereas older Kenyan women aged between 40 and 49 years reported higher levels of IPV (Memiah et al., 2018). Women of color tended to experience more frequent IPV and financial strain compared to their counterparts (Breiding et al., 2008; Golden et al., 2013; Memiah et al., 2018). Becoming married was associated with increased IPV (Dichter et al., 2017). Employment, higher level of education, and income are protective factors of IPV for women (Breiding et al., 2008; Stylianou, 2018; Zheng et al., 2019).

The association between financial strain and different types of IPV is unclear, with IPV being viewed as patterns of coercive control where abusers use force or threats to control victims (Stark, 2007). Matjasko et al. (2013) highlighted that different types of IPV require different prevention approaches because each type is associated with specific risks and protective factors. Identifying the specific form of IPV is pivotal to providing effective intervention and prevention.

Data and Methods

Sample

This study utilized data collected during a longitudinal, randomized controlled trial study evaluating the impact of a financial literacy program with female IPV survivors over 14 months (Postmus et al., 2015a,2015b). The Allstate Foundation collaborated with the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) to create a financial literacy curriculum that specifically addressed survivors’ economic empowerment, entitled “Moving Ahead through Financial Management.” The specific aims of the curriculum were to identify signs of financial abuse, and to enhance financial knowledge to ensure the survivors’ financial well-being.

The research team adopted the purposeful sampling strategy to recruit participants from 14 IPV organizations in 7 states from four regions, including Northeast, Midwest, Texas, and Puerto Rico. To participate, women must have: (1) experienced at least one form of intimate partner violence in the past year (Healthy People, 2020); be female and 18 years old or older; (3) had not taken a financial literacy class within the past 2 years; (4) committed to participate in four interviews; and (5) committed to attend the curriculum if randomly assigned.

Because most IPV agencies serve large populations of English and Spanish survivors, the instruments were translated into Spanish. To serve as a baseline, all participants were randomly assigned into either a control group or a treatment group at Time1 interview (T1). The first face-to-face interviews were conducted as the baseline prior to the implementation of the curriculum. Advocates across IPV agencies implemented the curriculum to IPV survivors who were randomly assigned to the treatment group while the control group received case management and regular services. The follow-up interviews took place 2 months after the first interview (T2), 8 months after the first interview (T3), and 14 months after the first interview (T4). To maintain retention, the incentives increased: T1—$25, T2—$30, T3—$35, and T4—$40.

A total of 477 female IPV survivors initially attended the parent study, and a total of 456 women were randomized at T1 after eligibility screening. The reasons for case removal included lack of abuse experiences (15 participants), completing the interview too early (5 participants), and duplication (1 participant). All participants were randomly assigned into either the control group (n = 240) or the treatment group (n = 216), and 65.6% of participants completed T2 interviews (n = 300). The response rates at T3 and T4 were 61.1% and 53.8% of the total 456 participants, respectively. Longitudinal studies of IPV survivors may face a high rate of attrition because of instability in their living situation caused by the abuse (Dutton et al., 2003); in turn, the attrition bias affects the validity of IPV interventions studies (Ramsay et al., 2005). To address the attrition issue, the sample of compliant participants at both T1 and T4 were used, and then the results were compared to multiple imputed data of the full sample.

Measures

Financial Strain

The dependent variable in this study was measured using an 18-item financial strain survey (FSS) developed by Aldana and Liljenquist (1998) and validated by Hetling et al. (2014) among IPV survivors. The scale utilized a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “1 = never” to “5 = always” on 18 items employing five subscales: poor financial education (i.e., “I feel well informed about financial matters”), poor relationships (i.e., “I tend to argue with others about money”), physical symptoms (i.e., My muscles get tense when I add up my bills), poor credit card e (i.e., “I get new credit cards to pay off old ones”), and inability to meet financial obligations (i.e., “Many of my bills are past due”). The total FSS in this study had a Cronbach’s reliability coefficient of 0.84 at T1 and 0.88 at T4. The five subscales at T1 also demonstrated strong internal reliability (poor financial education, α = 0.81; poor relationships, α = 0.80; physical symptoms = 0.87; poor credit card use, α = 0.54; inability to meet obligation, α = 0.82).

Intimate Partner Violence

The main independent variables consisted of different forms of IPV measured by the 25-item abusive behavior index-revised (ABI-R) scale (Postmus et al., 2015a,2015b), a modified version of 30 items from the original ABI (Shepard & Campbell, 1992). Participants reported behaviors that had been used by their intimate partner or former partner in the past 12 months using a 5-point Likert type scale from “1 = never” to “5 = very often”. Women were asked to report the frequency of experiencing physical abuse (i.e., suffering being pushed, hit, spanked, choked etc.), psychological abuse (i.e., suffering being threatened with or without weapon, humiliated, criticized, etc.), and sexual abuses (i.e., “pressured you to have sex in a way you don’t like.”) (alpha reliability = 0.95 at T1 and 0.97 at T4).

Additionally, economic abuse was measured by the 12-item scale of economic abuse (SEA-12; Postmus et al., 2016). Using a 5-point Likert-type scale from “1 = never” to “5 = quite often”, participants reported frequency of behaviors by their partner or ex-partner in the past 12 months, including employment sabotage (4 items, i.e., “Threaten you to make you leave work”), economic control (5 items, i.e. “Keep financial information from you”), and economic exploitation (3 items, i.e., “Spend the money you needed for rent or other bills.”) (alpha reliability = 0.88 at T1 and 0.92 at T4).

Control Variables

The current study included control variables that may affect IPV and financial strain, such as demographics, socioeconomic characteristics, familial factors, and membership in the treatment or control group. Demographic characteristics in this study consisted of age, ethnicity, and U.S.-born. Age was calculated as the participants’ year of birth subtracted from the year of the interview. Eight attributes of race/ethnicity were dichotomized into Hispanic and non-Hispanic. Participants were asked whether or not they were born in the US. The other three socioeconomic characteristics included education, employment status, and annual income. Participants were asked about their educational attainment; the years of completed education were collapsed into three groups: less than high school, high school, and college and graduate school. Their reports of employment status were dichotomized to employed and unemployed. Average annual household income was measured by 5-level categorical variables from less than U.S. $10,000, $10,001–$15,000, $ 15,001–$25,000, $25,001–$35,000, and more than $35,000. Since approximately half (45%) of the sample earned less than U.S. $10,000 per year, the answers were recorded into a dichotomous variable for whether the woman reported $10,000 or more of income compared with less. Regarding familial factors, participants were asked to reply yes or no to two questions: 1) whether they were currently in a relationship with the abusive partner and 2) responsible for any children under the age of 18. Participants who were randomly assigned to the treatment group received the financial literacy curriculum, whereas the control group received regular services.

Analytic Strategy

Regression and decomposition analysis were used to examine the association between different forms of IPV and financial strain among female survivors. To decompose the change of financial strain among female IPV survivors over time, this study used longitudinal data collected at both T1 (n = 456) and T4 (n = 246, 53.8% of T1 sample). The data on educational attainment, a critical factor associated with financial strain, was only available at T4. Thus, this study is limited to those who answered education level at T4 and used the same responses for their education variable at T1. As a result, this study analyzed the data from 229 female survivors to examine the association between IPV experiences and financial strain.

Missing values in longitudinal panel data is common in IPV studies because IPV survivors may be more likely to leave the study due to violence exposure (Johnson, 2018; Krause et al., 2008). In this study, the results of Little’s MCAR test (X2 = 3047.436, DF = 2897, p = 0.025) and separate-variance t-tests suggested that the data might not be missing completely at random but rather were consistent with missing at random (MAR) (Garson, 2015). To address the attrition issue, the multiple imputation method was used to generate the full sample data at T4 except for the outcome variable, financial strain. The regression results of the imputed data were used to compare with the results of the 229 female survivors at T4.

The fact that female IPV survivors may face living and job instability due to abuse experiences may also lead to higher rates of sample attrition (Dutton et al., 2003); in turn, the attrition bias affects the validity for the IPV longitudinal studies (Ramsay et al., 2005). According to the missing value analysis of the parent study, there was 29% missingness across all values in the data set (Johnson, 2018). Hence, this study used multiple imputation to generate 30 imputations to maintain the full sample of T4 (Graham, 2009). Multiple imputation was only used in the multivariate regression models, not the decomposition analysis because there is no available method to combine the imputation data in the decomposition analysis (Maika et al., 2013).

Multiple regression models were performed to examine the relationship between different types of abuse and socioeconomic variables on financial strain. Based on the linear regression method, the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition method (Blinder, 1973; Oaxaca, 1973) was used to partition different types of abuses in contributing to the change of financial strain over time. To compare the variation in the outcome differences, the decomposition technique has been widely applied to decompose the difference between changes over time (Vujicic & Nasseh, 2014) or the differences between two groups, such as gender wage gap (Oaxaca, 1973), racial wage discrimination (Blinder, 1973), racial placement instability (Foster et al., 2011), or rural–urban digital inequality (Liao et al., 2016). Regression and decomposition analysis were used to perform the data analysis by Stata 15 (StataCorp, 2017).

For the current study, the linear regression model is expressed as:

Y referred to financial strain and X denoted all forms of IPV including economic, physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. The g indicates the different time periods: T1 and T4, and g = (T1, T4), in which g was valued T1 or T4. For i = 1, 2,…, 229 in this sample. The Blinder and Oaxaca decomposition is explained in the following way:

In the above equation, the difference of financial strain at T1 and T4 were divided into two parts with a sum of 100%. The first “explained” part, , displays part of the difference of financial strain between T1 and T4 is due to the mean differences among different types of abuses between T1 and T4. More specifically, female IPV survivors whose financial strain changed over time would be explained by the change of their different experiences of abuse over time (e.g. physical abuse and economic abuse). The second “unexplained” part, , shows the remaining part of financial strain differences over time is beyond the explained coefficients, which could not be explained by the main independent variables. The higher percentage of explained part indicates that the differences of multiple IPV forms contribute to the difference of financial strain over time.

Results

Descriptive Results

In this study, the findings showed that the IPV experiences and financial strain significantly decreased over 14 months among female survivors. In Table 1, the mean of financial strain decreased significantly from 2.83 at T1 to 2.20 at T4. T-test results showed that the difference in financial strain between T1 and T4 was significant, t = 10.25 (p < 0.001). Similarly, each type of IPV significantly decreased from T1 to T4 (p < 0.001), and the significant differences can be decomposed into their contributions to the mean changes of financial strain over time. The majority of IPV survivors were in young adulthood (ages 30–45), Hispanic, college and graduate school, employed, and earned annual income over $10,000. Notably, almost four in five women (80%) were not in a relationship with an abuser at the time of the data collection, and had children under 18 years-old.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Time1 | Time4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Financial strain | 2.83 (0.63) | 2.20*** (0.68) |

| Physical abuse | 2.23 (1.02) | 1.20*** (0.57) |

| Psychological abuse | 3.51 (1.02) | 1.68*** (1.03) |

| Sexual abuse | 2.06 (1.17) | 1.14*** (0.76) |

| Economic abuse | 2.59 (0.93) | 1.43*** (0.77) |

| Age | ||

| Less than 30 | 23.14% | 20.52% |

| 30–45 | 55.02% | 56.33% |

| 45+ | 21.83% | 23.14% |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 14.41% | 14.41% |

| High school | 39.74% | 39.74% |

| College and graduate school | 45.85% | 45.85% |

| Hispanic | 60.26% | 60.26% |

| U.S.-born | 52.84% | 52.84% |

| In a relationship with abuser | 19.65% | 16.59% |

| Having children under 18 year-old | 81.22% | 81.66% |

| Employment status | 50.66% | 64.63% |

| Annual household income over $10,000 | 54.59% | 54.59% |

| Treatment group | 48.91% | 48.91% |

| N | 229 | 229 |

Mean or percentage

Standard deviation in parentheses

***p < 0.001

Multivariate Results

The regression results are presented in Table 2. The full model accounted for an estimated 13% and 22% of the variation in financial strain at T1 and T4, respectively. The effect of economic abuse on financial strain was greater than other factors, and persisted over time. Other types of abuse showed a marginal effect on financial strain. Age, Hispanic, and U.S.-born showed a significant impact on financial strain at T1, but the statistical significance diminished over time. Participation in the treatment group was significantly associated with the decrease in financial strain over time. Interestingly, employment and income status were not significantly associated with the magnitude of financial strain among these survivors. The regression models using multiple imputed data in the full sample of 456 participants at T4 despite attrition supported the research hypothesis that economic abuse, followed by physical abuse were more strongly associated with financial strain than other demographic or socioeconomic characteristics.

Table 2.

Regression models of financial strain on types of abuse and other factors

| T1 | T4 | All | Multiple imputation of T4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical abuse | 0.09 | 0.26* | 0.12 + | 0.32* |

| (0.05) | (0.14) | (0.05) | (0.15) | |

| Psychological abuse | − 0.02 | − 0.09 | 0.11 | − 0.02 |

| (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.09) | |

| Sexual abuse | 0.05 | − 0.17 + | − 0.01 | − 0.21 + |

| (0.04) | (0.12) | (0.04) | (0.11) | |

| Economic abuse | 0.29** | 0.36** | 0.34*** | 0.26* |

| (0.06) | (0.11) | (0.06) | (0.11) | |

| Age less than 30 | (Reference) | |||

| Age 30–45 | 0.16* | 0.16* | 0.15** | 0.20 + |

| (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.08) | (0.11) | |

| Age 45+ | 0.21* | 0.13 | 0.15** | 0.21 |

| (0.13) | (0.14) | (0.10) | (0.14) | |

| Less than high school | (Reference) | |||

| High school | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| (0.13) | (0.13) | (0.09) | (0.13) | |

| College and graduate school | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| (0.14) | (0.14) | (0.10) | (0.13) | |

| Hispanic | 0.20* | − 0.02 | 0.08 + | − 0.04 |

| (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.07) | (0.10) | |

| U.S.-born | 0.18* | − 0.11 | 0.04 | − 0.18 + |

| (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.07) | (0.11) | |

| In a relationship with abuser | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.04 | − 0.00 |

| (0.10) | (0.12) | (0.08) | (0.12) | |

| Having children under 18 year-old | 0.12 | − 0.01 | 0.01 | − 0.03 |

| (0.12) | (0.13) | (0.09) | (0.13) | |

| Employed | 0.01 | − 0.09 | − 0.04 | − 0.18 + |

| (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Annual household income over $10,000 | − 0.05 | − 0.09 | − 0.07 | − 0.11 |

| (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Treatment group | − 0.01 | − 0.21*** | − 0.11** | − 0.26** |

| (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| N | 229 | 229 | 458 | 456 |

| F | 3.32 | 5.39 | 14.06 | – |

| R2_a | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.30 | – |

Standardized beta coefficients; Standard errors in parentheses

+p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The decomposition model examined how time-changing variables accounted for the change of dependent variable. The decomposition results explained 76.68% of the difference on financial strain between T1 and T4, and the alleviation of IPV experiences mainly accounted for the decrease in financial strain (See Table 3). The decrease in economic abuse and physical abuse contributed nearly 77.92% of the difference, and economic abuse contributed over half (58.13%) of the change in financial strain over time. But the change in economic factors (employment and income) did not contribute significantly. The contributions of some variables equaled zero because they did not change over time, such as being Hispanic, U.S.-born, and assigned to the treatment group.

Table 3.

Decomposition results

| Coefficient | Contribution (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | 2.83*** | |

| Time 4 | 2.20*** | |

| Difference | 0.63*** | 100.00 |

| Explained | 0.48*** | 76.68 |

| Physical abuse | 0.10* | 19.79 |

| (0.05) | ||

| Psychological abuse | 0.11 | 22.92 |

| (0.08) | ||

| Sexual abuse | − 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (0.07) | ||

| Economic abuse | 0.28*** | 58.13 |

| (1.31) | ||

| Age | − 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (0.01) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) | ||

| U.S.-Born | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | ||

| Education level | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | ||

| Employment status | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (0.01) | ||

| Annual income over $10,000 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) | ||

| In a relationship with abuser | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| (0.00) | ||

| Having children under 18 year-old | − 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | ||

| Treatment group | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.01) |

Standard errors in parentheses

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion and Implications

Based on the stress process model (Pearlin et al., 1981), this study contributes to the delineation in the associations between IPV (stressor) and financial strain (outcome) among female survivors. This paper included different types of abuse with a focus on economic abuse that has not been previously addressed. For female IPV survivors, their perceptions of financial strain can be understood as the outcome of a prominent stressor: IPV. In particular, this research further identified that physical abuse and economic abuse experiences were significant stressors associated with financial strain based on the results of regression models. Decomposition results showed that 58% of the decrease in financial strain over time was explained by the decrease in economic abuse over a span of 14 months.

There has been increased attention to the relationship between economic abuse and financial consequences of IPV (Kutin et al., 2017; Sauber & O’Brien, 2017). The current findings are consistent with evidence from previous research (Schrag et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2019), which shows that economic abuse is found to be significantly associated with financial strain compared to different forms of IPV. Furthermore, this paper closes the gap showing that a change in economic abuse over time can account for the change in financial strain using longitudinal data. Given the fact that economic abuse involves behaviors aimed at controlling or exploiting individual’s access to finances, assets, or employment (Adams & Beeble, 2019; Postmus et al., 2020), survivors of economic abuse tend to suffer increasing financial strain. Future research based on the Stress Process Model (Pearlin et al., 1981) can explore potential moderators or mediators to modify the association by adding social support and coping behaviors. Also, future research can consider the association between IPV and financial strain as a stressor to examine its impact on mental health outcome such as depression.

Similar to the results of previous studies (Copp et al., 2016; Lucero et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2019), this study also found that physical abuse is associated with financial strain. Informed by the stress process model, the consequences of physical abuse may cause additional financial-related stressors leading to increased self-perceived financial strain. For instance, a physical injury may force women to leave work temporarily and then lose their source of income to make ends meet. Moreover, this study included the form of economic abuse and further specified that the impact of economic abuse on financial strain was stronger than other forms of IPV including physical abuse.

As economic abuse is commonly experienced among IPV survivors (Stylianou, 2018), this paper points out the importance of economic abuse and financial consequences of IPV that needs more attention in direct services. For example, social workers and risk assessors need to screen for economic abuse that is a less recognized form of IPV (Postmus et al., 2020). Clinicians and therapists need to assess financial well-being of IPV survivors. To alleviate financial strain, advocates need to be well versed in supporting survivors to develop safety plans aimed at decreasing physical and economic abuse experiences.

Notably, the COVID-19 related stressors resulted in increasing IPV as well as financial strain due to lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, social distancing guidelines, job loss, and financial uncertainty (Sri et al., 2021; Usher et al., 2020; Yenilmez & Çelik, 2020). The findings of this study highlight an urgent need to make IPV resources accessible for vulnerable populations, such as IPV screening for economic abuse and telehealth platforms on financial safety (Jarnecke & Flanagan, 2020). Future work can continue to investigate the association between economic abuse and financial strain among IPV survivors both during the COVID pandemic and beyond.

This study is the first study to use longitudinal panel data to confirm that the reduction in economic abuse subsequently improves women’s financial strain over time. Such findings are particularly salient in light of long-term financial insecurity and financial recovery for IPV survivors. Research has shown that COVID-19 related financial strain is highly associated with psychological impact such as loneliness, anxiety, depression (Kujawa et al., 2020; Refaeli & Achdut, 2021; Thayer & Gildner, 2020). To enhance the mental health of IPV survivors during macro economic events such as the pandemic, it is crucial to provide interventions to reduce economic abuse and financial strain.

One policy implication from the findings is evidence that experiencing IPV and financial hardship are often intertwined with economic inequality. Policy makers have a responsibility to protect IPV survivors from immediate and chronic abuse, and then follow up with legislation designed to secure their financial wellbeing. Legal systems should take proactive responses to address economic abuse against women; for instance, the violence against women act should be amended to include economic abuse as unacceptable behavior and hold perpetrators of economic abuse accountable (Postmus et al., 2015b). In addition, the criminal system needs to address protection for physical safety and financial security of IPV victims and survivors.

Although socioeconomic status is highly related to financial strain in the general population (Fatimah et al., 2012; Szanton et al., 2010; Zimmerman & Katon, 2005), such socioeconomic variables showed no associations with the magnitude of financial strain when IPV experiences were included. In this sample, nearly half of female survivors had college degrees and above, were employed but earning less than $10,000 per year. The sample did not have enough variation to test this relationship between socioeconomic status and financial strain. One possible reason is that economic abuse experiences directly affect individuals economic reality and financial well-being. Interestingly, age was the only demographic variable linked to financial strain. Older female survivors reported higher levels of financial strain, perhaps because they face a higher risk of no other income source.

Additionally, the decomposition results showed that 23.32% of the variance remained unexplained, after capturing all potential effects other than different types of abuse. One possible explanation may be that financial strain of female survivors decreased because they received formal support as a result of their help-seeking behaviors. As the sample of female IPV survivors were recruited from shelters and advocacy agencies, external resources may decrease their perceptions of financial strain over time. More research is needed to examine other potential factors.

The findings of this study examined the relationship between IPV and financial strain faced by many female survivors, and a few limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. With regard to the characteristics of the study sample, the self-selected responses and limited sample size impacted the generalizability. First, the missing data of education attainment at T1 limited the full understanding of association between socioeconomic status and financial wellbeing among female survivors. Second, the study sample for the parent study was a purposive sample in certain states and was not randomly selected from a population of female IPV survivors. Participants who received domestic violence services volunteered to participate in a financial literacy program and chose to respond to the evaluation survey. The response bias limited the generalizability of the findings to other female IPV survivors across the nation. Further research is suggested to determine if these results hold up over a longer period of time. The finding of this study evidenced the prominent association between economic abuse and financial strain; researchers can further include financial strain as a significant variable and examine its effect on other outcomes including depression.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of all the survivors, agencies, advocates, and members of the research team who made this study possible.

Funding

This project was supported by The Allstate Foundation, Economics Against Abuse Program. Points of view in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of The Allstate Foundation. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of all the survivors, agencies, advocates and members of the research team who made this study possible.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams AE. Measuring the effects of domestic violence on women’s financial well-being. Center for Financial Security, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Issue Brief. 2011;5:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adams AE, Beeble ML. Intimate partner violence and psychological well-being: Examining the effect of economic abuse on women’s quality of life. Psychology of Violence. 2019;9(5):517–525. doi: 10.1037/vio0000174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams AE, Tolman RM, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Kennedy AC. The impact of intimate partner violence on low-income women’s economic well-being: The mediating role of job stability. Violence against Women. 2013;18(12):1345–1367. doi: 10.1177/1077801212474294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahnquist J, Fredlund P, Wamala SP. Is cumulative exposure to economic hardships more hazardous to women’s health than men’s? A 16-year follow-up study of the Swedish Survey of Living Conditions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61(4):331. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.049395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldana SG, Liljenquist W. Validity and reliability of a financial strain survey. Financial Counseling and Planning. 1998;9(2):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- American Psycological Association. (2015). Stress in America. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2014/stress-report.pdf

- American Psycological Association. (2017). Stress in America. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2017/state-nation.pdf

- Åslund C, Larm P, Starrin B, Nilsson K. The buffering effect of tangible social support on financial stress: influence on psychological well-being and psychosomatic symptoms in a large sample of the adult general population. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2014 doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0085-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzani M, Roslani AC, Su TT. The perceived cancer-related financial hardship among patients and their families: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2015;23(3):889–898. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2474-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios YV, Gelaye B, Zhong Q, Nicolaidis C, Rondon MB, Garcia PJ, Sanchez PAM, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Association of childhood physical and sexual abuse with intimate partner violence, poor general health and depressive symptoms among pregnant women. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(1):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson ML, Fox GL, DeMaris A, Van Wyk J. Neighborhood disadvantage, individual economic distress and violence against women in intimate relationships. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2003;19(3):207–235. doi: 10.1023/A:1024930208331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun HA, Williams M, Beydoun MA, Eid SM, Zonderman AB. Relationship of physical intimate partner violence with mental health diagnoses in the Nationwide Emergency Department sample. Journal of Women's Health. 2017;26(2):141–151. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinder AS. Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources. 1973;8(4):436–455. doi: 10.2307/144855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp JE, Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA. Couple-level economic and career concerns and intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2016;78(3):744–758. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, Astbury J, Watts CH. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(5):e1001439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Haywood TN, Butler AE, Bellamy SL, Iverson KM. Intimate partner violence screening in the veterans health administration: Demographic and military service characteristics. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2017;52(6):761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drentea P, Reynolds JR. Where does debt fit in the stress process model. Society and Mental Health. 2014 doi: 10.1177/2156869314554486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Jouriles E, McDonald R, Krishnana S, McFarlane J. Recruitment and retention in intimate partner violence research. Department of Justice; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dziak E, Janzen BL, Muhajarine N. Inequalities in the psychological well-being of employed, single and partnered mothers: The role of psychosocial work quality and work-family conflict. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2010;9(6):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, E., Williamson, E., & Pantazis, C. (2016). Evidence and policy review—Domestic violence and poverty. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Retrived from https://research-information.bristol.ac.uk/files/80376377/JRF_DV_POVERTY_REPORT_FINAL_COPY_.pdf

- Fatimah O, Noraishah D, Nasir R, Khairuddin R. Employment security as moderator on the effect of job security on worker's job satisfaction and well being. Asian Social Science. 2012;8(9):50. doi: 10.5539/ass.v8n9p50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fink G. Stress: Definition and history. In: Fink G, editor. Stress science: Neuroendocrinology. Elsevier; 2010. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Foster EM, Hillemeier MM, Bai Y. Explaining the disparity in placement instability among African-American and white children in child welfare: A Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(1):118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, Benson ML, DeMaris AA, Wyk J. Economic distress and intimate violence: Testing family stress and resources theories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;64(3):793–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00793.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, Chancey D. Sources of economic distress: Individual and family outcomes. Journal of Family Issues. 1998;19(6):725–749. doi: 10.1177/019251398019006004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C, Davis CG, Elgar FJ. Financial strain, social capital, and perceived health during economic recession: A longitudinal survey in rural Canada. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2014;27(4):422–438. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.864389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedan B. Incorporating men into the women's movement. Georgetown Journal on Fighting Poverty. 1995;3(1):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Garson GD. Missing values analysis and data imputation. Statistical Associates Publishers; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Golden SD, Perreira KM, Durrance CP. Troubled times, troubled relationships: How economic resources, gender beliefs, and neighborhood disadvantage influence intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28(10):2134–2155. doi: 10.1177/0886260512471083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Banyard V. Beyond the 50-minute hour: Increasing control, choice, and connections in the lives of low-income women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, Singer R. When crises collide: How intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping? Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10(4):306–329. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowdy EA, Pearlmutter S. Economic self-sufficiency: It's not just money. Affilia. 1993;8(4):368–387. doi: 10.1177/088610999300800402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60(1):549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, McLoyd VC, Tokoyawa T. Financial strain, neighborhood stress, parenting behaviors, and adolescent adjustment in urban African American families. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15(4):425–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00106.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker JS, Huber GA, Nichols A, Rehm P, Schlesinger M, Valletta R, Craig S. The economic security index: A new measure for research and policy analysis. Review of Income and Wealth. 2014;60(Supp. 1):S5–S32. doi: 10.1111/roiw.12053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley C, Renner L. Economic self-sufficiency among women who experienced intimate partner violence and received civil legal services. Journal of Family Violence. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10896-018-9977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People. (2020). Adults with major depressive episodes (percent, 18+ years) by sex. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data/Chart/4814?category=2&by=Sex.

- Hetling A, Stylianou AM, Postmus JL. Measuring financial strain in the lives of survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0886260514539758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarnecke AM, Flanagan JC. Staying safe during COVID-19: How a pandemic can escalate risk for intimate partner violence and what can be done to provide individuals with resources and support. Psychological Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S202. doi: 10.1037/tra0000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L. Increasing financial empowerment for survivors of intimate partner violence: A longitudinal evaluation of financial knowledge curriculum Rutgers. The State University of New Jersey; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, Lazarus RS. Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1981;4(1):1–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00844845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB. Psychological distress in sociological context: Toward a general theory of psychosocial stress. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial stress: Trends in theory and research. Academic Press Inc; 1983. pp. 195–264. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Gray KA. Leave or stay?: Battered women's decision after intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(10):1465–1482. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Dutton MA. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: A longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(1):83–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Green H, Compas BE, Dickey L, Pegg S. Exposure to COVID-19 pandemic stress: Associations with depression and anxiety in emerging adults in the United States. Depression and Anxiety. 2020;37(12):1280–1288. doi: 10.1002/da.23109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutin J, Russell R, Reid M. Economic abuse between intimate partners in Australia: Prevalence, health status, disability and financial stress. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2017;41(3):269–274. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagdon S, Armour C, Stringer M. Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2014;5(1):24794. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.24794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P-A, Chang H-H, Wang J-H, Sun L-C. What are the determinants of rural-urban digital inequality among schoolchildren in Taiwan? Insights from Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Computers & Education. 2016;95:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chae DH. Stress, marital satisfaction, and psychological distress among African Americans. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31(8):1081–1105. doi: 10.1177/0192513x10365826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero JL, Lim S, Santiago AM. Changes in economic hardship and intimate partner violence: A family stress framework. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2016;37(3):395–406. doi: 10.1007/s10834-016-9488-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maika A, Mittinty MN, Brinkman S, Harper S, Satriawan E, Lynch JW. Changes in socioeconomic inequality in Indonesian children’s cognitive function from 2000 to 2007: A decomposition analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e78809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masarik AS, Conger RD. Stress and child development: A review of the family stress model. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017;13:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matjasko JL, Niolon PH, Valle LA. Different types of intimate partner violence likely require different types of approaches to prevention: A response to Buzawa and Buzawa. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2013;32(1):137–139. doi: 10.1002/pam.21667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenry PC, Julian TW, Gavazzi SM. Toward a biopsychosocial model of domestic violence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:307–320. doi: 10.2307/353685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Memiah P, Ah Mu T, Prevot K, Cook CK, Mwangi MM, Mwangi EW, Owuor K, Biadgilign S. The prevalence of intimate partner violence, associated risk factors, and other moderating effects: Findings from the Kenya National Health Demographic Survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0886260518804177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Preamble to the code of ethics. Retrieved from, https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics

- Oaxaca R. Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review. 1973;14(3):693–709. doi: 10.2307/2525981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oram S, Khalifeh H, Howard LM. Violence against women and mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(2):159–170. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22(4):337–356. doi: 10.2307/2136676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postmus JL, Hetling A, Hoge GL. Evaluating a financial education curriculum as an intervention to improve financial behaviors and financial well-being of survivors of domestic violence: Results from a longitudinal randomized controlled study. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 2015;49(1):250–266. doi: 10.1111/joca.12057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Postmus JL, Stylianou AM, McMahon S. The abusive behavior inventory-revised. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0886260515581882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postmus JL, Hoge GL, Breckenridge J, Sharp-Jeffs N, Chung D. Economic abuse as an invisible form of domestic violence: A multicountry review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2020;2(2):261–283. doi: 10.1177/1524838018764160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postmus JL, Plummer S-B, McMahon S, Murshid NS, Kim MS. Understanding economic abuse in the lives of survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(3):411–430. doi: 10.1177/0886260511421669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postmus JL, Plummer S-B, Stylianou AM. Measuring economic abuse in the lives of survivors: Revising the Scale of Economic Abuse. Violence against Women. 2016;22(6):692–703. doi: 10.1177/1077801215610012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulgar CA, Trejo G, Suerken C, Ip EH, Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Economic hardship and depression among women in Latino farmworker families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2016;18(3):497–504. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahe RH, Meyer M, Smith M, Kjaer G, Holmes TH. Social stress and illness onset. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1964;8(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(64)90020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay J, Feder G, Rivas C, Carter Y, Davidson L, Hegarty K, Taft A, Warburton A. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Wiley; 2005. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb BT, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Perceived economic strain exacerbates the effect of paternal depressed mood on hostility. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27(2):263–270. doi: 10.1037/a0031898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refaeli T, Achdut N. Financial strain and loneliness among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of psychosocial resources. Sustainability. 2021;13(12):6942. doi: 10.3390/su13126942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resko SM. Intimate partner violence and women's economic insecurity. LFB Scholarly Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ribar, D. (2005). The persistence of financial strains among low-income families: An analysis of multiple indicators. unpublished paper, Department of Economics, The George Washington University.

- Ryan C. Responses to financial stress at life transition points. FaHCSIA Occasional Paper No. 41. 2012 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2230176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sauber EW, O’Brien KM. Multiple losses: The psychological and economic well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0886260517706760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag RJV, Ravi KE, Robinson SR. The role of social support in the link between economic abuse and economic hardship. Journal of Family Violence. 2020;35(1):85–93. doi: 10.1007/s10896-018-0019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Reese LM, Peek-Asa C, Parker E. Associations of financial stressors and physical intimate partner violence perpetration. Injury Epidemiology. 2016;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40621-016-0069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature. 1936;138(3479):32. doi: 10.1038/138032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. The stress of life (Revised ed.) McGraw-Hill; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard MF, Campbell JA. The abusive behavior inventory: A measure of psychological and physical abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992;7(3):291–305. doi: 10.1177/088626092007003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Basile KC, Gilbert LK, Merrick MT, Patel N, Walling M, Jain A. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 State report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sri AS, Das P, Gnanapragasam S, Persaud A. COVID-19 and the violence against women and girls: ‘The shadow pandemic’. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2021;67(8):971–973. doi: 10.1177/0020764021995556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark E. Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata statistics/data analysis software: Release 15.1. StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Strenio, J. A. (2017). The economic consequences of intimate partner violence during young adulthood: Longitudinal evidence from the US. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Department of Economics, University of Utah. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/593c20e615d5db6254ba71c7/t/5a292f7e9140b775cde5489e/1512648575097/Strenio_JMP_Nov30.pdf

- Stylianou AM. Economic abuse experiences and depressive symptoms among victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2018;33(6):381–392. doi: 10.1007/s10896-018-9973-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Whitfield K. Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer ZM, Gildner TE. COVID-19-related financial stress associated with higher likelihood of depression among pregnant women living in the United States. American Journal of Human Biology. 2021;33(3):e23508. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.23508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995 doi: 10.2307/2626957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(s):S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, J., & Lowell, C. (2016). National snapshot: Poverty among women and families, 2015. National Women’s Law Center. Retrieved from https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Poverty-Snapshot-Factsheet-2016.pdf

- Tucker-Seeley RD, Harley AE, Stoddard AM, Sorensen GG. Financial hardship and self-rated health among low-income housing residents. Health Education & Behavior. 2012;40(4):442–448. doi: 10.1177/1090198112463021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher K, Bhullar N, Durkin J, Gyamfi N, Jackson D. Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2020 doi: 10.1111/inm.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino SW, Moore JE, Cleveland MJ, Greenberg MT, Tan X. Profiles of financial stress over time using subgroup analysis. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2014;35(1):51–64. doi: 10.1007/s10834-012-9345-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vosloo W, Fouché J, Barnard J. The relationship between financial efficacy, satisfaction with remuneration and personal financial well-being. International Business & Economics Research Journal. 2014;13(6):1455–1470. doi: 10.19030/iber.v13i6.8934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vujicic M, Nasseh K. A decade in dental care utilization among adults and children (2001–2010) Health Services Research. 2014;49(2):460–480. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller CE, Logan AM. Measuring middle class economic security. Journal of Economic Issues. 2009;43(2):327–336. doi: 10.2753/JEI0021-3624430205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. The domains and boundaries of stress concepts. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial stress: Perspectives on structure, theory, life-course, and methods. Academic Press; 1996. pp. 29–70. [Google Scholar]

- White ME, Satyen L. Cross-cultural differences in intimate partner violence and depression: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2015;24:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead BR, Bergeman CS. The effect of the financial crisis on physical health: Perceived impact matters. Journal of Health Psychology. 2017;22(7):864–873. doi: 10.1177/1359105315617329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeni̇lmez Mİ, Çeli̇k OB. Pandemics and domestic violence during Covid-19. International Journal of Contemporary Economics and Administrative Sciences. 2020;10(1):213–234. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3940534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yick AG. Predictors of physical spousal/Intimate violence in Chinese American families. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15(3):249–267. doi: 10.1023/A:1007501518668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Xu X, Xu T, Yang L, Gu X, Wang L. Financial strain and intimate partner violence against married women in postreform China: Evidence from Chengdu. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0886260519853406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman FJ, Katon W. Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: What lies behind the income-depression relationship? Health Economics. 2005;14(12):1197–1215. doi: 10.1002/hec.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]