Abstract

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive fibrotic lung disease that is characterised by aberrant proliferation of activated myofibroblasts and pathological remodelling of the extracellular matrix. Previous studies have revealed that the intermediate filament protein nestin plays key roles in tissue regeneration and wound healing in different organs. Whether nestin plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of IPF needs to be clarified.

Methods

Nestin expression in lung tissues from bleomycin-treated mice and IPF patients was determined. Transfection with nestin short hairpin RNA vectors in vitro that regulated transcription growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad signalling was conducted. Biotinylation assays to observe plasma membrane TβRI, TβRI endocytosis and TβRI recycling after nestin knockdown were performed. Adeno-associated virus serotype (AAV)6-mediated nestin knockdown was assessed in vivo.

Results

We found that nestin expression was increased in a murine pulmonary fibrosis model and IPF patients, and that the upregulated protein primarily localised in lung α-smooth muscle actin-positive myofibroblasts. Mechanistically, we determined that nestin knockdown inhibited TGF-β signalling by suppressing recycling of TβRI to the cell surface and that Rab11 was required for the ability of nestin to promote TβRI recycling. In vivo, we found that intratracheal administration of AAV6-mediated nestin knockdown significantly alleviated pulmonary fibrosis in multiple experimental mice models.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal a pro-fibrotic function of nestin partially through facilitating Rab11-dependent recycling of TβRI and shed new light on pulmonary fibrosis treatment.

Short abstract

Nestin regulates the vesicular trafficking system by promoting Rab11-dependent recycling of TβRI and thereby contributes to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Precise targeting of nestin may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for IPF. https://bit.ly/3zO75c3

Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis is a pathological outcome of many chronic inflammatory and autoimmune pulmonary diseases. The most common form of pulmonary fibrosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), is characterised by alveolar epithelial cell injury, fibroblast proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation and progressive collagen deposition, eventually leading to organ malfunction and death [1–4]. Currently, there is still a lack of an effective medical therapy for IPF, in part because its pathogenic mechanisms remain unclear [5]. Thus, it is urgent to explore the exact molecular mechanism underlying IPF progression, with the goal of developing new treatments.

Nestin is a type VI intermediate filament protein that was originally identified in neural progenitor/stem cells of the developing central nervous system [6, 7]. Recent studies have shown that nestin is not only a common marker of multilineage stem cells, but also plays direct biological roles in active proliferation and tissue regeneration in different tissues and organs [8, 9]. Our previous studies showed that nestin could regulate the structural and functional homeostasis of mitochondria [10]. We also demonstrated that nestin regulated the antioxidant capacity of cells through the Keap1-Nrf2 feedback loop [11] and that nuclear nestin regulated the homeostasis of nuclear lamin A/C and contributed to cellular senescence [12]. In addition, nestin was reported to participate in the pathogenesis of fibrosis in multiple organs. For example, nestin expression was increased in activated rat hepatic stellate cells, fibrotic kidney and heart tissues [13–15], suggesting that it might be an activation marker of tissue fibrosis. However, the exact molecular mechanisms through which nestin contributes to pulmonary fibrosis remain poorly understood.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is a multifunctional cytokine that has been shown to play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of organ fibrosis [16, 17]. TGF-β activates the phosphorylation of Smad by TGF-β receptor I (TβRI) and TGF-β receptor II (TβRII) [16]. Furthermore, phosphorylated Smad translocates into the nucleus, where it modulates the transcription of downstream target genes, including α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and collagen I [17]. Abundant evidence has demonstrated that endocytosis and trafficking of TGF-β receptors significantly regulate the activation of TGF-β intracellular signalling [18–20]. Endosomal TGF-β receptors follow two trafficking routes in cells: some are recycled to the plasma membrane, while others are sorted to late endosomes/lysosomes for degradation [21]. In addition, small Ras-like GTPases are well-recognised regulators of various membrane trafficking events [22–24]. For instance, Rab11 and Rab4 are known to play essential roles in regulating recycling endosomes [25]. Therefore, whether nestin participates in the endocytosis and trafficking of TGF-β receptors still needs to be clarified.

Here, we detected the expression and localisation of nestin in the lungs of bleomycin-induced murine pulmonary fibrosis model mice and IPF patients, and investigated the potential role of nestin in regulating TGF-β/Smad signalling and Rab11-mediated TβRI recycling. Additionally, we addressed whether targeting nestin could be an attractive strategy for attenuating pulmonary fibrosis in vivo.

Material and methods

A detailed description of methods is provided in the supplementary material.

Animal experiments

Animal use was approved by the ethical committee of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China). C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory. Nestin–GFP mice (expressing nestin promoter-driven green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the C57BL/6 genetic background) were provided by Masahiro Yamaguchi (Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Japan) [26]. All mice were provided free access to food and water and kept in a colony room on a 12:12 h light/dark cycle in the Sun Yat-sen University animal centre. For bleomycin or amiodarone instillation, 8-week-old mice were anaesthetised with isoflurane and injected intratracheally with bleomycin (Teva Pharmaceutical; 3 U·kg−1) or with amiodarone (Sigma-Aldrich; 0.8 mg·kg−1 per 5 days). Control groups received injections with an equal volume of PBS or 4% ethanol. The TGF-β1-overexpression lung fibrosis model has been described previously [27, 28]. Adenovirus expressing constitutively active TGF-β1 and control virus vector were purchased from the Hanbio Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). For AdTGF-β1 instillation, 8-week-old mice were anaesthetised with isoflurane and injected intratracheally with AdTGF-β1 (1.5×1012 pfu) or with Advector (1.5×1012 pfu).

Study population

Human lung tissues with fibrosis were obtained by diagnostic surgical lung biopsies from patients who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for IPF at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou, China). Control human lung tissue samples were collected from surgical lung resections from patients with lung cancer at the same hospital. All patients signed informed consent for their samples to be used for research, and approval was obtained from the committees for ethical review of research.

Statistics

All data are reported as the mean±sd of at least three independent experiments. Sample sizes are all presented in the figure legends. Statistical analysis between two groups was performed using unpaired t-test. Statistical analysis between multiple groups was performed by one-way ANOVA, with Tukey's multiple comparison test. All data were analysed using Prism software (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was taken as p<0.05, with significance defined as p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001.

Results

Nestin is upregulated in experimental pulmonary fibrosis and localises mainly in lung myofibroblasts

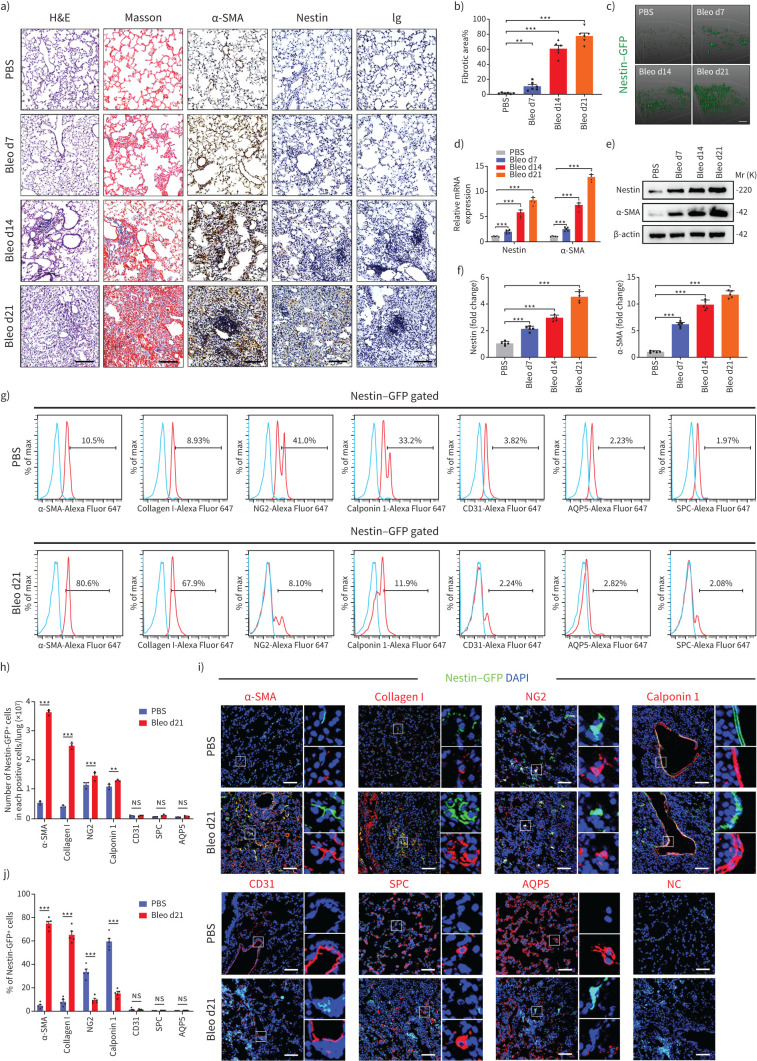

First, we confirmed that bleomycin instillation led to lung collagen deposition and fibrosis, as demonstrated by haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson trichrome and α-SMA staining. Meanwhile, we found that nestin protein levels and the proportion of nestin+ cells gradually increased during the development of lung fibrosis (figure 1a–c and supplementary figure S1a and b). Then, we further confirmed that both mRNA and protein levels of nestin increased markedly in fibrotic lung tissues as the degree of lung fibrosis increased (figure 1d–f). In addition, analysis of bulk RNA-sequence data from GSE110533 revealed significant upregulation of nestin in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis mice [29] (supplementary figure S1c). In addition, overexpression of nestin observed in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis was predominantly localised to lung myofibroblasts, as validated by flow cytometry and immunofluorescent staining (figure 1g–j and supplementary figure S1d). Besides, these findings were further evidenced by single-cell RNA-seq analyses from GSE132771 [30] (supplementary figure S1e–i). Furthermore, we found that some nestin+ cells co-expressed pericyte marker (NG2+) or smooth muscle cell marker (calponin 1+) in lung tissues and there was a slight increase of these two cell types in pulmonary fibrosis, although the percentage of nestin+NG2+ and nestin+calponin 1+ cells in all nestin+ cells decreased (figure 1g–j). Meanwhile, there was little to no colocalisation between nestin and CD31 (vascular endothelial cells), surfactant protein C (type II alveolar epithelial cells) or aquaporin 5 (type I alveolar epithelial cells) (figure 1g–j). These results suggested that nestin expression in lung myofibroblasts is positively correlated with the severity of pulmonary fibrosis.

FIGURE 1.

Nestin is upregulated in experimental pulmonary fibrosis, and localised mainly in lung myofibroblasts. a) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Masson's trichrome staining and immunohistochemistry images obtained using anti-α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), anti-nestin antibody of lung sections from C57/BL6 mice on days (d)7, 14 and 21 after bleomycin exposure (n=6 per group). b) Quantification of the area occupied by fibrotic stroma in the Masson's trichrome staining results presented in a) (n=6 per group). c) Two-photon fluorescent images of lung sections obtained from nestin–green fluorescent protein (GFP) mice (n=6 per group). Scale bars=100 µm. d) Quantitative (q)PCR analysis of α-SMA and nestin mRNA expression levels in lungs on days 7, 14 and 21 after bleomycin exposure (n=5 mice per group). e) Western blot analysis and f) quantification of nestin and α-SMA expression in lungs 7, 14 and 21 days after bleomycin exposure (n=5 mice per group). g) Flow cytometry was carried out to determine the co-expression of nestin and α-SMA and collagen I (myofibroblasts), NG2 (pericytes), calponin 1 (smooth muscle cells), CD31 (vascular endothelial cells), surfactant protein C (SPC) (type II alveolar epithelial cells), or aquaporin (AQP)5 (type I alveolar epithelial cells) in mice control and fibrotic lung samples. h) Statistical analysis of the number of nestin-positive cells in each positive cell type, as obtained from g) (n=3 mice per group). i) Immunofluorescence was carried out to determine the co-localisation of nestin–GFP (green) and α-SMA (myofibroblasts), collagen I (myofibroblasts), NG2 (pericytes), calponin 1 (smooth muscle cells), CD31 (vascular endothelial cells), SPC (type II alveolar epithelial cells) or AQP5 (type I alveolar epithelial cells) (red) in lungs. Scale bars=50 µm. NC: negative control. j) Semiquantitative scoring of double-positive cells as a percentage of nestin-positive cells, as obtained from immunofluorescent images (n=5 mice per group; five fields assessed per sample). ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sd; **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

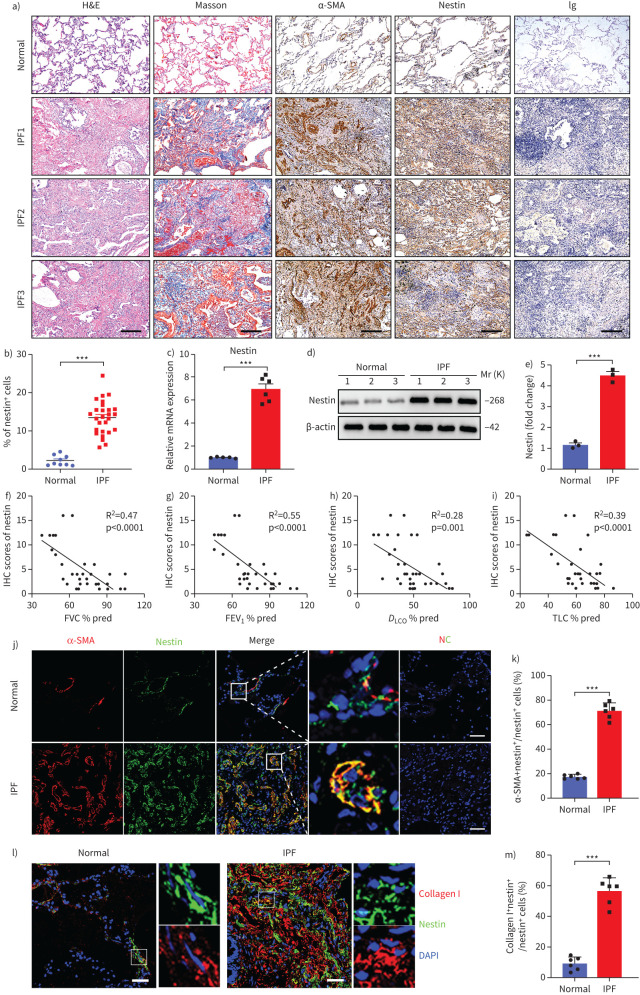

Nestin is upregulated in the lungs of patients with IPF

Next, we examined nestin expression in the lungs of IPF patients and healthy donors. Similarly, we found that nestin was markedly overexpressed in IPF fibrotic lungs compared with normal lungs (figure 2a–e). This was further confirmed by bulk RNA-seq data analysis of lungs from IPF samples and control samples from GSE124685 [31] (supplementary figure S2a). Single-cell RNA-sequencing of normal and fibrotic human lungs (GSE132771) also proved the similar phenomenon as in mice [30] (supplementary figure S2b–f). In addition, we analysed the correlation between nestin expression in patients with IPF and certain clinical lung function test parameters. Interestingly, nestin expression was negatively correlated with percentage predicted values for total lung capacity, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, forced expiratory volume in 1 s and forced vital capacity (figure 2f–i, supplementary tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, immunofluorescence assays and single-cell RNA-seq analysis both revealed that nestin was primarily expressed in myofibroblasts, as evidenced by colocalisation with both α-SMA and collagen I (figure 2j–m and supplementary figure S2b–h). The results suggested that nestin may play an important role in regulating the progression of IPF.

FIGURE 2.

Nestin is upregulated in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). a) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Masson's trichrome staining and immunohistochemistry images of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and nestin in lung sections from IPF patients and healthy donors. Scale bars=200 µm. b) Quantification of nestin-positive cells of immunohistochemistry images from IPF patients and healthy donors (n=27 IPF patients, n=9 healthy donors; five fields assessed per sample). c) Quantitative (q)PCR analysis of nestin mRNA expression in the lungs from IPF patients and healthy donors (n=6 IPF patients, n=5 healthy donors). d) Western blot analysis and e) quantification of nestin expression in lung sections from IPF patients and healthy donors (n=3 IPF patients, n=3 healthy donors). Linear regression between nestin expression in patients with IPF and clinical parameters such as f) forced vital capacity (FVC) % pred, g) forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) % pred, h) diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) % pred and i) total lung capacity (TLC) % pred (n=35 IPF patients). j) Immunofluorescence staining of nestin and α-SMA in lung sections from IPF patients and healthy donors. Scale bars=50 µm. NC: negative control. k) Semiquantitative scoring of double-positive cells as a percentage of nestin-positive cells, as obtained from immunofluorescent images (n=6 IPF patients, n=6 healthy donors; five fields assessed per sample). l) Immunofluorescence staining of lung tissues from normal and IPF patients visualised using anti-nestin (green) and anti-collagen I (red). Scale bars=50 µm. m) Semiquantitative scoring of double-positive cells as a percentage of nestin-positive cells, as obtained from immunofluorescent images (n=6 IPF patients, n=6 healthy donors; five fields assessed per sample). IHC: immunohistochemistry. Data are presented mean±sd of three independent experiments; ***: p<0.001; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

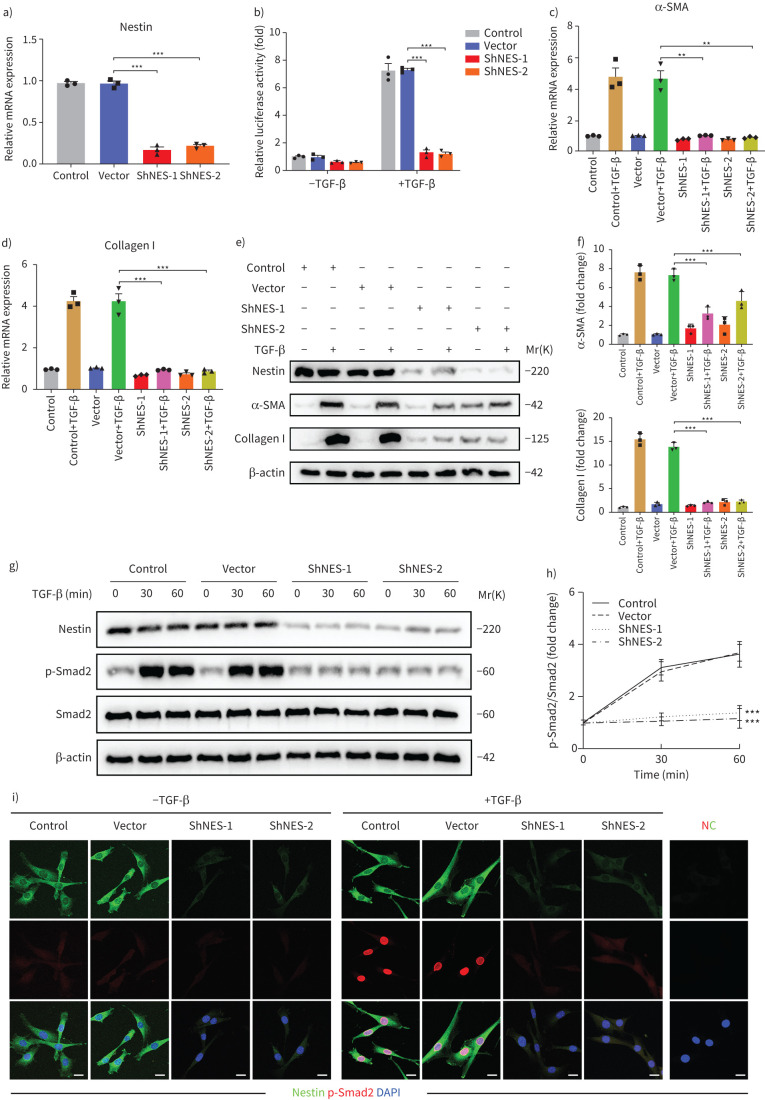

Nestin knockdown inhibits the TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway

Next, we isolated primary fibroblasts from the lungs of mice and evaluated the functions of nestin. First, nestin was significantly downregulated in primary mouse lung fibroblasts subjected to nestin knockdown by two different short hairpin RNAs and the TGFβ-inducible Smad binding element (SBE) luciferase activities were accordingly decreased (figure 3a and b). Then, we observed decreases in α-SMA and collagen I mRNA and protein levels after nestin knockdown (figure 3c–f). Furthermore, knockdown of nestin suppressed Smad2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation (figure 3g–i and supplementary figure S3a–d). To further confirm the overall influences of nestin on TGF-β pathway, we knocked out nestin in human fetal lung fibroblast cell line (MRC-5) as reported in our previous study [12]. Consistent with these results, TGF-β-mediated phosphorylated Smad2 and α-SMA expression were markedly decreased (supplementary figure S3e–j). In addition, we investigated the effect of nestin on the activities of non-Smad TGF-β pathways through using luciferase reporters and found no significant differences in these pathways after nestin knockdown (supplementary figure S4a–d). There were no marked changes in other effectors, such as Cav1 and Akt phosphorylation and β-catenin translocation, except Pai-1 (supplementary figure S4e–i). Taken together, these results revealed that nestin deficiency primarily inhibits the TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway in vitro.

FIGURE 3.

Nestin knockdown inhibits transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad signalling. a) Nestin expression in primary mouse lung fibroblasts was analysed by quantitative (q)PCR (n=3 per group). b) Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts were transfected with pGL3-SBE9-luciferase constructs and treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) for 24 h, and luciferase activity was measured (n=3 per group). c) qPCR analysis of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) mRNA expression in primary mouse lung fibroblasts with nestin knockdown (n=3 per group). d) qPCR analysis of collagen I mRNA expression in primary mouse lung fibroblasts with nestin knockdown (n=3 per group). e) Western blot analysis and f) quantification of α-SMA and collagen I expression in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated for 72 h with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) (n=3 per group). g) Western blot analysis and h) quantification of p-Smad2 and Smad2 expression in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) (n=3 per group). i) Immunofluorescence staining of nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) and visualised using anti-nestin (green) and anti-p-Smad2 (red). Scale bars=10 µm. NC: negative control. Data are presented as the mean±sd of three independent experiments; **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

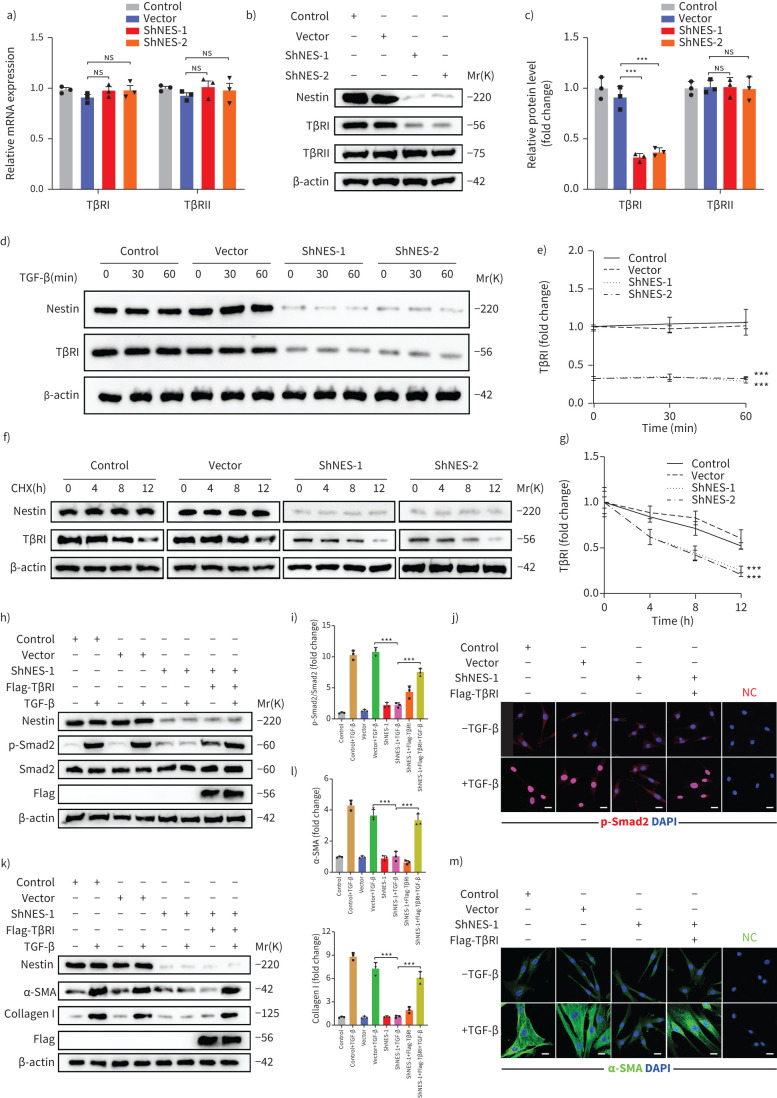

Nestin knockdown inhibits TGF-β signalling by regulating the stability of TβRI

TGF-β signalling is a canonical pathway that involves the phosphorylation of Smad by TβRI and TβRII. Given that TGF-β receptors have been widely reported to significantly regulate the activation of the intracellular TGF-β signalling pathway [18–20], we assessed whether nestin regulated the expression of TGF-β receptors and found that nestin knockdown decreased the protein levels of TβRI instead of the mRNA levels of TβRI or TβRII in primary mouse lung fibroblasts and MRC5 (figure 4a–c and supplementary figure S5a–c). Furthermore, we tested the effect of nestin knockdown on TβRI at different time points after TGF-β stimulation and found no differences with or without TGF-β stimulation (figure 4d and e). Accordingly, we treated primary mouse lung fibroblasts with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide and detected that nestin knockdown resulted in a shortened half-life of TβRI (figure 4f and g). These data suggested that nestin may modulate the stability of TβRI at the post-translational level independent of TGF-β stimulation. Furthermore, the nestin knockdown-induced inhibition of TGF-β-mediated Smad2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation was completely restored by the re-introduction of TβRI (figure 4h–j and supplementary figure S5d). In addition, we found that nestin knockdown suppressed the TGF-β-mediated upregulation of α-SMA and collagen I, and this effect could be rescued by overexpression of TβRI (figure 4k–m). These data suggested that nestin knockdown inhibits TGF-β signalling and myofibroblast activation by inducing downregulation of TβRI expression.

FIGURE 4.

Nestin knockdown inhibits transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad signalling via regulating the stability of TGF-β receptor I (TβRI) in mice. a) Quantitative (q)PCR analysis of TβRI and TβRII mRNA expression levels in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). b) Western blot analysis and c) quantification of TβRI and TβRII expression in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). d) Western blot analysis and e) quantification of TβRI expression in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts at different time points after TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) stimulation (n=3 per group). f) Half-life analysis and g) quantification of TβRI in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts. All cell groups were treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg·mL−1) harvested at the indicated times (0, 4, 8, 12 h after CHX treatment) and subjected to immunoblotting (n=3 per group). h) Western blot analysis and i) quantification of Smad2 phosphorylation levels with nestin knockdown and TβRI overexpression treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) (n=3 per group). j) Immunofluorescence staining of p-Smad2 in primary mouse lung fibroblasts by nestin knockdown and overexpression of TβRI. Scale bars=20 µm. NC: negative control. k) Western blot analysis and l) quantification of α-SMA and collagen I expression levels in primary mouse lung fibroblasts by nestin knockdown and overexpression of TβRI (n=3 per group). m) Immunofluorescence staining of α-SMA in primary mouse lung fibroblasts by nestin knockdown and overexpression of TβRI. Scale bars=20 µm. ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as the mean±sd of three independent experiments; ***: p<0.001; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

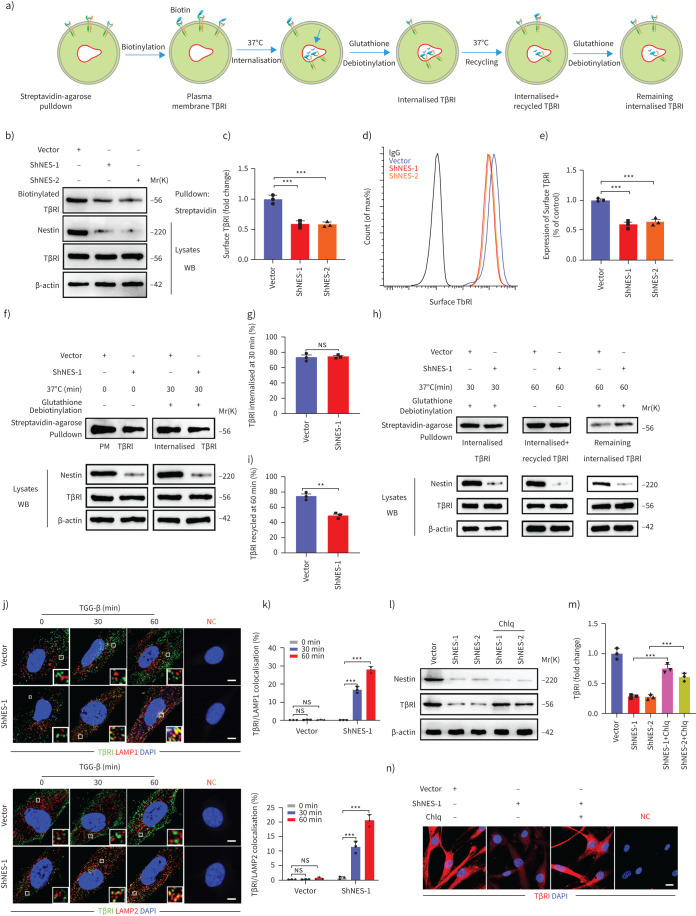

Nestin knockdown inhibits the recycling of TβRI to the cell surface

Since TβRI is known to be endocytosed and recycled to the cell surface (figure 5a) and intracellular trafficking of TβRI is known to be required for TGF-β signalling [18], we first used biotinylation of cell-surface proteins to determine whether nestin affected TβRI protein levels on the plasma membrane. Interestingly, the protein level of TβRI on the cell surface was decreased in nestin-knockdown cells (figure 5b and c). Similarly, this result was further confirmed by flow cytometry (figure 5d and e). Endosomal receptors follow two trafficking routes in cells: some are recycled to the plasma membrane, while others are sorted to late endosomes/lysosomes for degradation [21, 23]. Accordingly, we used biotinylation assays to examine plasma membrane TβRI, TβRI endocytosis and TβRI recycling and found that only 50% of internalised TβRI was recycled in nestin-knockdown cells compared to 75% in control cells (figure 5f–i). Conversely, we also found that nestin knockdown significantly increased the amount of TβRI that reached lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP)1+ or LAMP2+ vesicles (figure 5j and k). Moreover, knockdown of nestin destabilised TβRI in primary mouse lung fibroblasts, which could be partially rescued by the lysosome inhibitor, chloroquine (figure 5l–n). Together, these data indicated that nestin knockdown may suppress TβRI recycling.

FIGURE 5.

Nestin knockdown inhibits the recycling of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor (TβR)I to the cell surface. a) Schematic overview of the biotinylation assay for quantifying plasma membrane TβRI level, TβRI endocytosis and recycling. b) Detection of the protein levels of TβRI on the plasma membrane in biotinylated serum-starved nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts after treatment with chloroquine (Chlq, 100 μM) for 4 h. c) Quantification of the surface TβRI protein levels in b) (n=3 per group). d) Live-cell fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of surface TβRI levels in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts. e) Quantification of TβRI levels shown in panel d) (n=3 per group). f) Biotinylated serum-starved nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts were placed at 37°C for 30 min and then treated with glutathione after treated with Chlq (100 μM) for 4 h, and subjected to streptavidin agarose pulldown and Western blot analysis of TβRI. g) Quantification of the percentage of internalised TβRI in f) (n=3 per group); TβRI internalisation rate=total internalised TβRI at 30 min/plasma membrane TβRI×100%. h) Western blot analysis of recycled TβRI at 60 min. i) Quantification of the percentage of recycled TβRI in h) (n=3 per group); TβRI recycling rate=(internalised and recycled TβRI at 60 min−internalised TβRI at 60 min)/total internalised TβRI at 30 min×100%. j) Immunofluorescence staining of lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP)1 or LAMP2 and TβRI in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1). Scale bars=5 µm. NC: negative control. k) Quantification of the percentage of TβRI colocalised with LAMP1 or LAMP2 (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). l) Western blot analysis and m) quantification of TβRI expression levels in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with or without Chlq (100 μM) (n=3 per group). n) Immunofluorescence staining of TβRI in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with or without Chlq (100 μM) for 4 h. Scale bars=20 µm. PM: plasma membrane; ns: nonsignificant. Data are presented as mean±sd of three independent experiments; ***: p<0.001; unpaired t-test and one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

Nestin overexpression promotes TGF-β/Smad signalling and the recycling of TβRI

To further confirm the impact of nestin on TβRI expression, recycling and signalling, we overexpressed flag-nestin in primary mouse lung fibroblasts (supplementary figure S6a). Consistently, nestin overexpression increased the protein levels of TβRI instead of the mRNA levels of TβRI or TβRII, and the TGFβ-inducible SBEs luciferase activities accordingly increased (supplementary figure S6b–e). Overexpression of nestin promoted phosphorylated Smad2 nuclear translocation and upregulated the mRNA and protein levels of α-SMA and collagen I (supplementary figure S6f–i). Furthermore, the protein level of surface TβRI was increased in nestin-overexpressed cells (supplementary figure S6j and k), and nestin overexpression significantly enhanced TβRI recycling to the cell surface, but showed no apparent effects on TβRI internalisation (supplementary figure S6l–o).

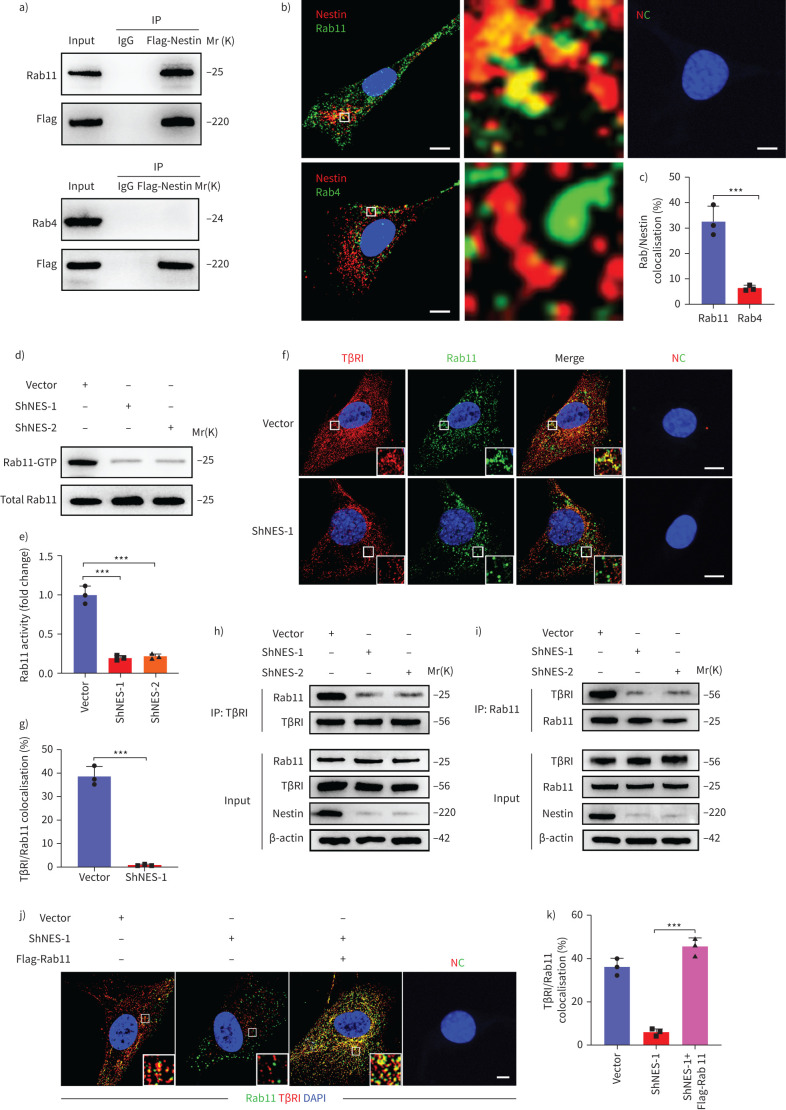

Rab11 is required for the ability of nestin to promote the recycling of TβRI to the cell surface

Recycling of TβRI to the plasma membrane is known to depend on Rab-like GTPases [25]. Rab4 and Rab11 play key roles in regulating the transport of cargo from early and late recycling endosomes to the cell surface, respectively [22–25]. Accordingly, we found that nestin could colocalise with Rab11, but not Rab4 in primary mouse lung fibroblasts (figure 6a–c). Moreover, nestin knockdown inhibited Rab11 GTPase activity (figure 6d–e). Furthermore, immunofluorescence and co-immunoprecipitation showed that TβRI colocalised less with Rab11 in nestin-knockdown cells (figure 6f–i). Thus, nestin knockdown appears to inhibit the Rab11-dependent transportation of TβRI-containing recycling endosomes. We then investigated whether Rab11 was involved in nestin-mediated TβRI recycling and found that TβRI in nestin-knockdown cells colocalised less with Rab11+ recycling vesicles, but more with lysosomes, which could be partly rescued by overexpression of Rab11 (figure 6j–k and supplementary figure S7a–c). Meanwhile, the suppression of TGF-β-mediated Smad2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation by nestin knockdown could be blocked by Rab11 overexpression (supplementary figure S7d–f). Similarly, the inhibition of α-SMA and collagen I upregulation in nestin-knockdown cells after TGF-β stimulation was also rescued by reintroducing Rab11 (supplementary figure S7g–i). Taken together, these data suggest that Rab11 plays a critical role in nestin-mediated recycling of TβRI to the plasma membrane.

FIGURE 6.

Rab11 is required for the ability of nestin to promote the recycling of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor (TβR)I to the cell surface. a) Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using an anti-flag-nestin antibody, and immunoblotting of the protein levels of Rab11 and Rab4 in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts. b) Immunofluorescence staining showed the colocalisation between nestin and Rab11, Rab4 in primary mouse lung fibroblasts. Scale bars=10 µm. NC: negative control. c) Quantification of the percentage of nestin co-localised with Rab11 and Rab4 (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). d) Rab11 activity assays were performed in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts. e) Quantification of Rab11GTPase activity (n=3 per group). f) Immunofluorescence staining of Rab11 and TβRI in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts. Scale bars=5 µm. g) Quantification of the percentage of TβRI colocalised with Rab11 (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). h) Immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-TβRI antibody, and immunoblotting of the protein levels of Rab11 in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with chloroquine (Chlq) (100 μM) for 4 h. i) Immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-Rab11 antibody, and immunoblotting of the protein levels of TβRI in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with Chlq (100 μM) for 4 h. j) Immunofluorescence staining of TβRI and Rab11 in nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts with overexpression of Rab11. Scale bars=5 µm. k) Quantification of the percentage of TβRI colocalised with Rab11 (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). Scale bars=5 µm. Data are presented as mean±sd of three independent experiments; ***: p<0.001; unpaired t-test and one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

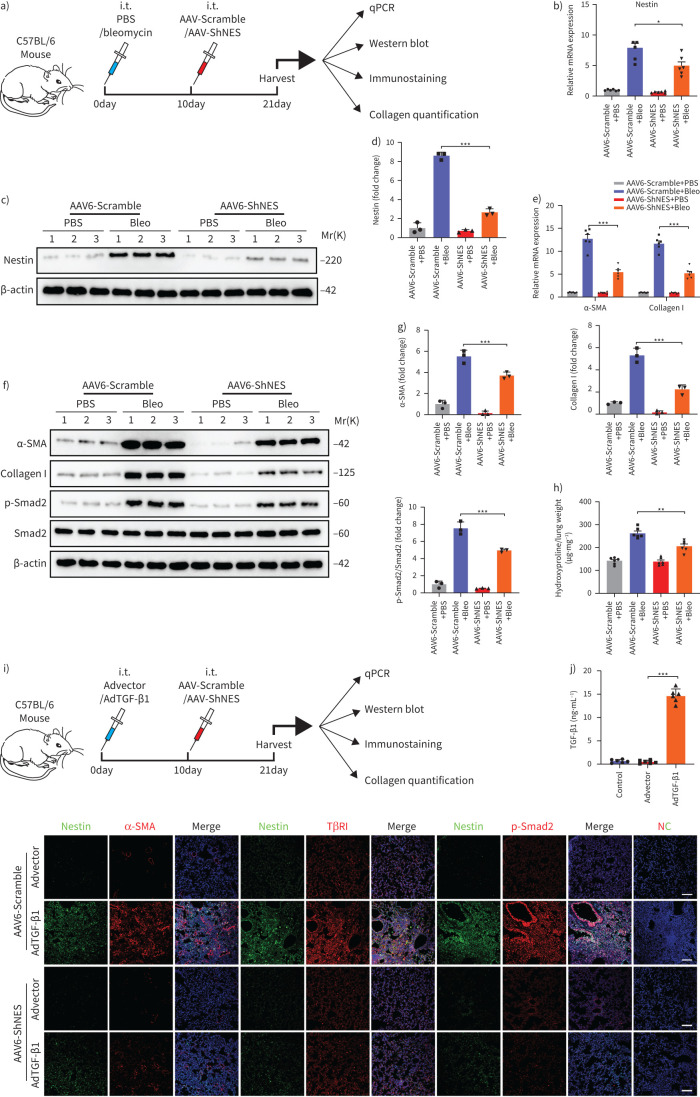

Downregulation of nestin attenuates pulmonary fibrosis in multiple experimental mice models

To examine the role of nestin in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis in vivo, we subjected C57/BL6 mice to bleomycin or PBS injection and then intratracheally delivered Adeno-associated virus serotype (AAV)6-Scramble or AAV6-ShNES to the mice 10 days later (figure 7a). At 11 days after AAV6 delivery, we harvested lung tissues for analysis and found that both nestin, collagen I and α-SMA expression and Smad2 phosphorylation in lung tissues from the AAV6-ShNES group were significantly lower than in lung tissues from the AAV6-Scramble group (figure 7b–g). Consistently, the administration of AAV6-ShNES could attenuate bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, which was evidenced by hydroxyproline assays, H&E and Masson trichrome staining (figure 7h and supplementary figure S8a). Furthermore, knockdown of nestin dramatically downregulated the bleomycin-induced expression of surface TβRI and α-SMA (supplementary figure S8b–d). Together, these data suggest that nestin knockdown attenuated bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in vivo, and similar effects were observed in a mouse three-dimensional lung tissue model and amiodarone-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model (supplementary figure S8e–m and S9a–h). In addition, we made a noninflammatory lung fibrosis model by administration of adenovirus containing TGF-β1 cDNA (figure 7i–j and supplementary figure S10a). Consistently, collagen I and α-SMA levels in lungs of AAV6-ShNES group were decreased compared with those of AAV6-Scramble group in AdTGF-β1-treated mice and nestin knockdown inhibited TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway, which indicated the function of nestin in pulmonary fibrosis may be dependent on TGF-β/Smad signalling rather than inflammation (figure 7k and supplementary figure S10b–l). Besides the therapeutic role of nestin knockdown in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, pre-treatment with AAV6-ShNES prior to bleomycin instillation further demonstrated the preventive effects of nestin knockdown on bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (supplementary figure S11a–l and supplementary figure S12a–e).

FIGURE 7.

Downregulation of nestin attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β overexpression-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. a) Experimental design. 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were injected intratracheally with bleomycin (3 U·kg−1) or PBS. 10 days later, the mice were injected intratracheally with Adeno-associated virus serotype (AAV)6-ShNES or AAV6-Scramble. Samples were collected for analysis 21 days after bleomycin administration. b) Quantitative (q)PCR analysis of nestin mRNA expression in the lungs of C57/BL6 mice from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). c) Western blot analysis and d) quantification of nestin expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3 per group). e) qPCR analysis of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and collagen I mRNA expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=6 mice per group). f) Western blot analysis and g) quantification of α-SMA, collagen I, p-Smad2 and Smad2 expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3 per group). h) Hydroxyproline levels in lungs of C57/BL6 mice from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). i) Experimental design. 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were injected intratracheally with AdTGF-β1 or Advector. 10 days later, the mice were injected intratracheally with AAV6-ShNES or AAV6-Scramble. Samples were collected for analysis 21 days after bleomycin administration. j) TGF-β1 levels in the lungs of C57/BL6 mice from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). k) Immunofluorescence staining with nestin, α-SMA, TβRI and p-Smad2 in lung slices from the different groups. Scale bars=70 µm. NC: negative control. Data are presented as the mean±sd of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

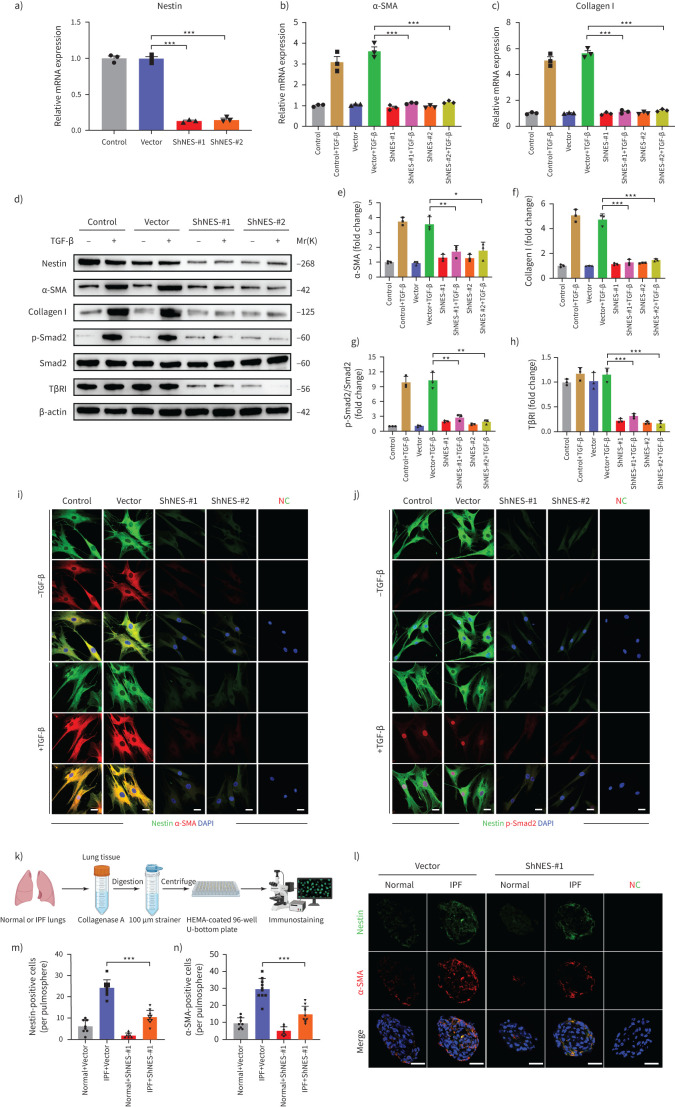

Downregulation of nestin inhibits the TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway in human fibroblasts and pulmospheres

Furthermore, in order to demonstrate the potential of nestin in a human background, we separated fibroblasts from human lung tissues and treated with nestin expression interference [32]. The results showed that nestin knockdown not only inhibited the expression of collagen I and α-SMA, but also decreased TβRI expression and suppressed Smad2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation in human fibroblasts with TGF-β treatment (figure 8a–j). Moreover, to clarify the therapeutic potential role of nestin inhibition in human fibrosis model, we obtained human pulmospheres from normal and IPF lung biopsies (figure 8k). We observed decrease in α-SMA levels after nestin knockdown in IPF pulmospheres (figure 8l–n). These data further confirmed that nestin played a critical role in regulating TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway in a human background.

FIGURE 8.

Nestin knockdown inhibits transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad signalling in human fibroblasts and pulmospheres. a) Nestin expression in primary human lung fibroblasts was analysed by quantitative (q)PCR (n=3 per group). b) qPCR analysis of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) mRNA expression in human lung fibroblasts with nestin knockdown (n=3 per group). c) qPCR analysis of collagen I mRNA expression in human lung fibroblasts with nestin knockdown (n=3 per group). d) Western blot analysis and quantification of e) α-SMA, f) collagen I, g) p-smad2, smad2 and h) TGF-β receptor (TβR)I expression in nestin-knockdown human lung fibroblasts treated for 72 h with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) (n=3 per group). i) Immunofluorescence staining of nestin-knockdown human lung fibroblasts treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) and visualised using anti-nestin (green) and anti-α-SMA (red). Scale bars=10 µm. NC: negative control. j) Immunofluorescence staining of nestin-knockdown human lung fibroblasts treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL−1) and visualised using anti-nestin (green) and anti-p-Smad2 (red). Scale bars=10 µm. k) Overview of human pulmospheres preparation from normal and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) lung tissues and immunostaining. l) Immunofluorescence staining of nestin-knockdown human pulmospheres and visualised using anti-nestin (green) and anti-α-SMA (red). Scale bars=50 µm. m) Quantification of nestin-positive cells per pulmosphere in l). n) Quantification of α-SMA positive cells per pulmosphere in l). Data are presented as mean±sd of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

IPF is a deadly disease with a high prevalence which affects 1 million people worldwide; its management remains an ongoing challenge because of its complex and undefined aetiology [5]. Recent results indicate that nestin expression is induced during fibrosis development in multiple organs, suggesting that this protein might be involved in the development of organ fibrosis [13, 33, 34]. Here, we provide evidence showing that nestin regulates the vesicular trafficking system by promoting recycling of TβRI to the cell membrane through Rab11 and thereby contributes to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis (supplementary figure S13). More importantly, precise targeting of nestin expression within lung myofibroblasts can alleviate lung fibrogenesis and may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for IPF.

Nestin is an intermediate filament protein. While it is widely known as a marker of neural stem cells, it is also expressed in the mesenchymal parts of various organs during the development and wound repair [8, 9]. Previous studies identified nestin+ fibroblasts in rat lungs, and a subpopulation exhibited a myofibroblast phenotype delineated by co-expression of α-SMA, indicating that they play a role in facilitating the reactive fibrotic response [33]. In an asthmatic nestin-Cre; ROSA26-EYFP mouse model, Ke et al. [35] observed that nestin+ cells could differentiate into fibroblasts/myofibroblasts through RhoA/ROCK signalling activation. In this study, we found that the nestin level primarily increased in α-SMA+ myofibroblasts in the lungs of IPF patients and bleomycin-treated mice, which resulted in collagen deposition and pulmonary fibrosis, similar to observations in previous studies. Conversely, we also found that several nestin+ cells co-expressed pericyte marker (NG2+) or smooth muscle cell marker (calponin 1+), with an increase of the absolute number of nestin+NG2+ and nestin+calponin 1+ cells, although the percentage of these two cell types decreased in lung fibrosis. Using a pulmonary hypertension nestin–GFP mouse model, Saboor et al. [36] reported that nestin-expressing pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells drive the development of pulmonary hypertension. Moreover, NG2+ pericytes also accumulate and produce collagen near the fibrotic tissue in the lungs after injury, which leads to scar formation [37]. Considering that nestin+NG2+ or nestin+calponin 1+ cells might also participate in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis, it will be interesting to further characterise the heterogeneity of nestin+ cells in lung fibrosis via single-cell sequencing and lineage tracing tools in the future.

The TGF-β/Smad family pathway plays a critical role in the activation of myofibroblasts and the progression of pulmonary fibrosis [17]. Many studies have demonstrated that endocytosis, intracellular trafficking and recycling of TGF-β receptors take part in TGF-β downstream signalling [23]. Clathrin-mediated and caveolae-mediated endocytosis are the two major pathways participating in the internalisation of TGF-β receptors [19, 38]. Internalisation of TGF-β receptors via clathrin-coated pits can enhance TGF-β signalling [18], whereas caveolae-mediated endocytosis of TGF-β receptors facilitates receptor degradation and thus the turn-off of signalling [39]. In this study, we demonstrated that nestin is a central regulator of the intracellular vesicular trafficking system and promotes the recycling of TβRI to the cell membrane via Rab11. However, we did not observe significant changes on caveolin-1 protein expression after nestin knockdown in primary mouse lung fibroblasts (supplementary figure S4f and g), which indicates that nestin might not be mainly involved in caveolae-mediated endocytosis of TβRI in pulmonary fibrosis. Because the clathrin-mediated pathway also participates in internalisation and transportation of TGF-β receptors to early endosomes [40], whether nestin regulates TGF-β receptors endocytosis and recycling through the clathrin-mediated pathway needs to be clarified in future studies.

Although the TGF-β/Smad signalling pathway is one of the drivers of organ fibrosis progression, TGF-β receptor inhibitors might not be suitable for treating pulmonary fibrosis [41], because TGF-β receptors are widely distributed in various cell types and participate in the pleiotropic functions including cellular proliferation, differentiation and migration [42]. Therefore, more precise cellular and molecular targets are urgently needed. Recently, AAV vectors have come to be regarded as an effective and relatively safe gene delivery tool in clinical trials, due to their low oncogenicity and weak immunogenicity [43, 44]. In the present study, we injected AAV6 vectors intratracheally to knockdown nestin in the lungs of mice and found that the efficacy of AAV6 transduction in α-SMA+ myofibroblasts was ∼80%, indicating a relatively high targeting effect of AAV6-ShNES on lung myofibroblasts. Compared with the AAV6-Scramble group, those subjected to AAV6-mediated nestin knockdown exhibited dramatic attenuation of pulmonary fibrosis, as indicated by the alleviation of collagen accumulation and improvement of histopathological alterations. Further exploration of the therapeutic effects of targeting nestin in lung fibrosis will be of interest.

There are several limitations to our study. Firstly, nestin mRNA abundance was different from its protein expression, probably because there might exist multiple processes beyond transcript concentration contributing to establishing the expression level of a protein [45]. Secondly, there existed different types of protein–mRNA correlations [46], which might be due to the single-cell RNA-seq sensitivity, which limited the detection of some transcripts in a large proportion of cells [47, 48].

Besides, myofibroblasts are a group of heterogeneous cells, which are the major source of accumulated extracellular matrix during organ fibrosis [49], and the origin of these cells may come from multiple cell types, such as proliferating lung resident fibroblasts [50], CD73+ and Pdgfrb1+ pericytes [51], Gli1+ mesenchymal stromal cells [52] and dysfunctional epithelial cells [53]. Meanwhile, as for the regulation and cell-type expression of nestin in normal and fibrotic lungs, it was demonstrated that nestin was expressed heterogeneously in various cell populations in lungs such as fibroblasts/myofibroblasts or pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells [33, 35, 36]. In our study, we found that nestin mainly expressed in myofibroblasts and some expressed in pericytes and smooth muscle cells in normal and fibrotic lungs. Therefore, lineage tracing experiments will need to be performed to determine whether nestin+ cells can serve as the origin of lung myofibroblasts in vivo in future studies.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary methods and tables. ERJ-03721-2020.Supplement (361.5KB, pdf)

Supplementary figure S1. Nestin expression in experimental pulmonary fibrosis and RNA-seq data, and co-expression of Nestin and Collagen I, α-SMA, NG2, Calponin 1, CD31, SPC or AQP5 in mice lungs. a) Immunofluorescence staining of Nestin in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice on day 7, 14 and 21 days after bleomycin exposure. Scale bars: 100 μm. b) Quantification of Nestin-positive cells from immunofluorescent images in a) (n=6 mice per group; five fields assessed per sample). c) Nestin gene expression extracted from GSE110533 in mice fibrotic and control lung samples. d) Gating strategies of Nestin-GFP positive cells in myofibroblasts (both α-SMA+ and Collagen I+), pericytes (NG2+), smooth muscle cells (Calponin 1+), vascular endothelial cells (CD31+), type II alveolar epithelial cells (SPC+), or type I alveolar epithelial cells (AQP5+) respectively in flow cytometry analysis. e) Cell clusters of the sc-RNA-seq data from GSE132771. f) UMAP plot of all cells of the scRNA-seq data in e). g) UMAP plots of Hhip, Aspn, Acta2, Col1a1, Cspg4 and Cnn1 of the scRNA-seq data in e). Blue indicates high expression. h) UMAP of Nestin of the scRNA-seq data in e). i) Violin plot of Nestin expression in each cell cluster. Green box indicates myofibroblast cluster. Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S1 (2.5MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S2. Nestin expression in IPF and co-localisation of Nestin and Collagen I, NG2, Calponin 1, CD31, SPC or AQP5 in IPF lungs. a) Nestin gene expression extracted from GSE124685 in IPF and control lung samples. b) Cell clusters of the sc-RNA-seq data from GSE132771. c) UMAP plot of all cells of the sc-RNA-seq data from GSE132771 in IPF and normal conditions. d) UMAP plots of ASPN, COL1A1, POSTN and CTHRC1 of the scRNA-seq data in IPF. Blue indicates high expression. e) UMAP plots of NESTIN of the scRNA-seq data in IPF. Blue indicates high expression. f) Violin plot of NESTIN in each cell cluster. Red box indicates myofibroblast cluster. g) Immunofluorescence assay was carried out to determine the co-localization of Nestin (green) and NG2 (pericytes), Calponin 1 (smooth muscle cells), CD31 (vascular endothelial cells), SPC (type II alveolar epithelial cells) or AQP5 (type I alveolar epithelial cells) (red) respectively in IPF lungs. Scale bars: 40 μm. h) Semiquantitative scoring of double-positive cells as a percentage of Nestin-positive cells, as obtained from immunofluorescent images (n=6 per group; five fields assessed per sample). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S2 (4.2MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S3. Nestin knockdown inhibits TGF-β/Smad signalling. a) Immunoblotting analysis of p-Smad2 and Smad2 protein levels in nucleus and cytoplasm. Control and Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts were treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1). b-d) Quantification of p-Smad2 and Smad2 levels in total, cytoplasmic and nuclear cell lysates (n=3 per group). e) Western blot analysis and f) quantification of p-Smad2 and Smad2 levels with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Nestin knockout (Nestin KO1) or overexpression of Nestin treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) in MRC5s (n=3 per group). g) Western blot analysis and h) quantification of α-SMA levels with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Nestin knockout (Nestin KO1) or overexpression of Nestin treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) in MRC5s (n=3 per group). i) Western blot analysis and j) quantification of p-Smad2, Smad2 and α-SMA levels with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Nestin knockout (Nestin KO2) or overexpression of Nestin treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) in MRC5s (n=3 per group). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S3 (1.4MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S4. The effect of Nestin on the activity of non-smad TGF-β pathways. a-d) Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts were transfected with pGL3-SRE, pGL3-FOXO, pGL3-AP-1 and pGL3-ELK-1 luciferase reporters and treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) for 24 h, and luciferase activities were measured (n=3 per group). e) qPCR analysis of PAI-1 mRNA expression in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). f) Western blot analysis and g-h) quantification of Cav1, p-Akt and Akt expression in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated for 72 h with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) (n=3 per group). i) Immunofluorescence staining of Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) and visualised using anti-β-catenin (red). Scale bars: 20 μm. Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S4 (2.1MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S5. Nestin knockdown inhibits TGF-β/Smad signalling via regulating TβRI stability in MRC5s. a) qPCR analysis of TβRI and TβRII mRNA expression in Nestin-knockdown MRC5s (n=3 per group). b) Western blot analysis and c) quantification of TβRI and TβRII expression in Nestin-knockdown MRC5s (n=3 per group). d) Immunofluorescence staining of p-Smad2 in MRC5s with Nestin knockdown and overexpression of TβRI treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1). Scale bars: 20 μm. Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S5 (991.7KB, tif)

Supplementary figure S6. Nestin overexpression promotes TGF-β/Smad signalling and TβRI recycling. a) qPCR analysis of Nestin expression in Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). b) qPCR analysis of TβRI and TβRII mRNA expression levels in Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). c) Western blot analysis and d) quantification of TβRI and TβRII expression in Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). e) Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts were transfected with pGL3-SBE9-luciferase constructs and treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) for 24 h, and luciferase activity was measured (n=3 per group). f) qPCR analysis of α-SMA and Collagen I expression in Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). g) Western blot analysis and h) quantification of α-SMA and Collagen I expression treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) in Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts (n=3 per group). i) Immunofluorescence staining of Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) and visualised using anti-Nestin (green) and anti-p-Smad2 (red). Scale bars: 20 μm. j) Detect the protein levels of TβRI on the plasma membrane in biotinylated serum-starved Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts after treated with Chlq (100 μM) for 4 h. k) quantification of surface TβRI protein levels in j) (n=3 per group). l) Biotinylated serum-starved Nestin-overexpressed primary mouse lung fibroblasts were placed at 37 C for 30 min and then treated with glutathione after treated with Chlq (100 μM) for 4 h, and then harvested and subjected to streptavidin agarose pull down and western blot analysis of TβRI, PM: plasma membrane. m) Quantification of the percentage of internalised TβRI in l) (n=3 per group); TβRI internalisation rate = total internalised TβRI at 30 min / Plasma membrane TβRI × 100%. n) Western blot analysis of recycled TβRI at 60 min. o) Quantification of the percentage of recycled TβRI in n) (n=3 per group); TβRI recycling rate = (internalised and recycled TβRI at 60 min - internalised TβRI at 60 min) / total internalised TβRI at 30 min × 100%). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; Unpaired t test and one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S6 (2.5MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S7. Rab11 is required for the ability of Nestin to promote the recycling of TβRI to the cell surface. a) Immunofluorescence staining of TβRI and LAMP1 in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts with or without overexpression of Rab11. Scale bars: 5 μm. b) Immunofluorescence staining of TβRI and LAMP2 in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts with or without overexpression of Rab11. Scale bars: 5 μm. c) Quantification of the percentage of TβRI co-localised with LAMP1 and LAMP2. (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). d) Western blot analysis and e) quantification of p-Smad2 and Smad2 expression levels in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts with Rab11 overexpression and treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) (n=3 per group). f) Immunofluorescence staining of p-Smad2 and Nestin in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts with Rab11 overexpression and treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1). Scale bars: 20 μm. g) Western blot analysis and h) quantification of α-SMA and Collagen I expression levels in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts with Rab11 overexpression and treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1) (n=3 per group). i) Immunofluorescence staining of α-SMA in Nestin-knockdown primary mouse lung fibroblasts with Rab11 overexpression and treated with or without TGF-β (5 ng·mL-1). Scale bars: 20 μm. Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S7 (2.6MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S8. Downregulation of Nestin attenuates pulmonary fibrosis in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis model and 3D-LTC. a) HE staining and Masson’s trichrome staining in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups. Scale bars: 100 μm. b) Immunofluorescence staining with surface TβRI and α-SMA in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups. Scale bars: 50 μm. c-d) Mean fluorescence intensity of surface TβRI and α-SMA in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). e) Experimental design. 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally injected with bleomycin (3 U·kg-1) or PBS. Three weeks after the bleomycin, 3D-LTC was performed and treated with AAV6-ShNES or AAV6-Scramble after 48 h. Samples were collected for analysis 72 h after AAV6 administration. f) qPCR analysis of Nestin mRNA expression in lung slices from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). g) Immunofluorescence staining with collagen I in lung slices from the different groups. Scale bars: 70 μm. h) Mean fluorescence intensity of collagen I in lung slices from the different groups (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). i) Western blot analysis and j) quantification of Nestin expression levels in 3D-LTCs of the different groups (n=3 per group). k) qPCR analysis of α-SMA and Collagen I mRNA expression levels in 3D-LTCs of the different groups (n=6 mice per group). l) Western blot analysis and m) quantification of α-SMA, Collagen I expression levels in 3D-LTCs of the different groups (n=3 per group). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; Unpaired t test and one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S8 (4.4MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S9. Downregulation of Nestin attenuates pulmonary fibrosis in amiodarone-induced mouse pulmonary fibrosis model. a) Experimental design. 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally injected with amiodarone (0.8mg·kg-1 per day) or 4% Ethanol. The mice were intratracheally injected with AAV6-ShNES or AAV6-Scramble three days after first amiodarone administration. Samples were collected for analysis 14 days after first amiodarone administration. b) qPCR analysis of α-SMA and Collagen I mRNA expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=6 mice per group). c) Western blot analysis and d) quantification of α-SMA, Collagen I expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3 per group). e) HE staining and Masson’s trichrome staining in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups. Scale bars: 100 μm. f) Immunofluorescence staining of α-SMA in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups. Scale bars: 50 μm. g) Mean fluorescence intensity of α-SMA in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). h) Hydroxyproline levels in lungs of C57/BL6 mice from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S9 (2.3MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S10. Downregulation of Nestin attenuates pulmonary fibrosis in TGF-β overexpression-induced pulmonary fibrosis model. a) HE staining and Masson’s trichrome staining in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups. Scale bars: 100 μm. qPCR analysis of b) α-SMA and c) Collagen I mRNA expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=6 mice per group). d) Western blot analysis and quantification of e) Nestin, f) Collagen I, g) α-SMA, h) p-Smad2 and Smad2 expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3 per group). Mean fluorescence intensity of i) collagen I, j) TβRI and k) p-Smad2 in lung slices from the different groups as obtained from images in figure 7k (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). l) Hydroxyproline levels in lungs of C57/BL6 mice from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S10 (2.1MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S11. Downregulation of Nestin exerts preventive effects on bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. a) Experimental design. 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally injected with AAV6-ShNES or AAV6-Scramble. 21 days after the AAV administration, the mice were intratracheally injected with bleomycin (3 U·kg-1) or PBS. Samples were collected for analysis 21 days after bleomycin administration. b) qPCR analysis of Nestin mRNA expression in the lungs of C57/BL6 mice from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). c) Western blot analysis and d) quantification of Nestin expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3 per group). e) qPCR analysis of α-SMA and Collagen I mRNA expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=6 mice per group). f) Western blot analysis and g) quantification of α-SMA, Collagen I, p-Smad2 and Smad2 expression levels in lungs from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3 per group). h) Hydroxyproline levels in lungs of C57/BL6 mice from the different groups (n=6 mice per group). i) HE staining and Masson’s trichrome staining in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups. Scale bars: 100 μm. j) Immunofluorescence staining with surface TβRI and α-SMA lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups. Scale bars: 50 μm. k-l) Mean fluorescence intensity of surface TβRI and α-SMA in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice of the different groups (n=3; five fields assessed per sample). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S11 (4.5MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S12. AAV6 exposure targets α-SMA positive myofibroblasts in bleomycin-induced mouse pulmonary fibrosis model. a) Immunofluorescence was carried out to determine the co-localisation of AAV6-GFP (green) and α-SMA (red). Scale bars: 20 μm. b) Statistical analysis of efficacy of AAV6 transduction in α-SMA positive myofibroblasts (n=6 mice per group; five fields assessed per sample). c) Gating strategies of AAV6-GFP positive cells in myofibroblasts (α-SMA+). d) Flow cytometry was carried out to determine cell specificity of the AAV exposure. e) Statistical analysis of efficacy of AAV6 transduction in α-SMA positive myofibroblasts (n=3 mice per group). Data are presented as the mean±SD. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S12 (3.5MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S13. Illustration of Nestin-TβRI-Rab11 trimeric complexes in the regulation of pulmonary fibrosis. Some endosomal TGF-β receptors are recycled to the plasma membrane while others are sorted to late endosomes/lysosomes for degradation. Nestin can form trimeric complexes with TβRI and Rab11. Nestin knockdown inhibits the recycling of TβRI to the cell surface in a Rab11-dependent manner and promotes the degradation of TβRI via lysosome-dependent way, thereby suppressing TGF-β/Smad signalling. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S13 (520.4KB, tif)

Supplementary figure S14. Full length images of immunoblots. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S14 (1.3MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S15. Full length images of immunoblots. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S15 (1.4MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S16. Full length images of immunoblots. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S16 (1.5MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S17. Full length images of immunoblots. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S17 (1.2MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S18. Full length images of immunoblots. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S18 (1.2MB, tif)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

We thank the Center Core Facility, Zhongshan School of Medicine, Sun Yat-Sen University for providing instruments for two-photon fluorescence microscopy and a Zeiss 880 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope with Airyscan.

Footnotes

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.03146-2021

Conflict of interest: J. Wang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Lai has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Yao has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. Chen has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Cai has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Luo has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Wang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Qiu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Huang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Wei has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Wang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Q. Lu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Guan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Wang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Li has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.P. Xiang has nothing to disclose.

Support statement: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Stem cell and Translational Research (2018YFA0107200, 2017YFA0103403, 2017YFA0103802), Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA16010103, XDA16020701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730005, 81721003, 31771616, 81802402, 81971372, 32130046, 32170799, 82101367, 82170613), the Key Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2017B020231001, 2019B020234001, 2019B020236002, 2019B020235002), Key Scientific and Technological Program of Guangzhou City (201803040011), Regional Joint Fund-Youth Fund Projects of Guangdong Province (2020A1515110118) and the Research Start-up Fund of the Seventh Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (393011). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Sheppard D. ROCKing pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 1005–1006. doi: 10.1172/JCI68417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, et al. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahluwalia N, Shea BS, Tager AM. New therapeutic targets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Aiming to rein in runaway wound-healing responses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190: 867–878. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0509PP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 136–151. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, McKay RD. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell 1990; 60: 585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cattaneo E, McKay R. Proliferation and differentiation of neuronal stem cells regulated by nerve growth factor. Nature 1990; 347: 762–765. doi: 10.1038/347762a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 2010; 466: 829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang MH, Cai B, Tuo Y, et al. Characterization of Nestin-positive stem Leydig cells as a potential source for the treatment of testicular Leydig cell dysfunction. Cell Res 2014; 24: 1466–1485. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Cai J, Huang Y, et al. Nestin regulates proliferation and invasion of gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells by altering mitochondrial dynamics. Oncogene 2016; 35: 3139–3150. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Lu Q, Cai J, et al. Nestin regulates cellular redox homeostasis in lung cancer through the Keap1-Nrf2 feedback loop. Nat Commun 2019; 10: 5043. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Wang J, Huang W, et al. Nuclear Nestin deficiency drives tumor senescence via lamin A/C-dependent nuclear deformation. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 3613. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05808-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niki T, Pekny M, Hellemans K, et al. Class VI intermediate filament protein nestin is induced during activation of rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 1999; 29: 520–527. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomioka M, Hiromura K, Sakairi T, et al. Nestin is a novel marker for renal tubulointerstitial injury in immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Nephrology 2010; 15: 568–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Béguin PC, Gosselin H, Mamarbachi M, et al. Nestin expression is lost in ventricular fibroblasts during postnatal development of the rat heart and re-expressed in scar myofibroblasts. J Cell Physiol 2012; 227: 813–820. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correction: Role of transforming growth factor β in human disease. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 228. doi: 10.1056/nejm200007203430322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez IE, Eickelberg O. The impact of TGF-β on lung fibrosis: from targeting to biomarkers. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2012; 9: 111–116. doi: 10.1513/pats.201203-023AW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, et al. Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-β receptor signalling and turnover. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5: 410–421. doi: 10.1038/ncb975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YG. Endocytic regulation of TGF-β signaling. Cell Res 2009; 19: 58–70. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Krishnaveni MS, Li C, et al. Epithelium-specific deletion of TGF-β receptor type II protects mice from bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 277–287. doi: 10.1172/JCI42090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahimi RA, Leof EB. TGF-β signaling: a tale of two responses. J Cell Biochem 2007; 102: 593–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butterworth MB, Edinger RS, Silvis MR, et al. Rab11b regulates the trafficking and recycling of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2012; 302: F581–F590. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00304.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant BD, Donaldson JG. Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009; 10: 597–608. doi: 10.1038/nrm2755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi S, Kubo K, Waguri S, et al. Rab11 regulates exocytosis of recycling vesicles at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci 2012; 125: 4049–4057. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell H, Choudhury A, Pagano RE, et al. Ligand-dependent and -independent transforming growth factor-β receptor recycling regulated by clathrin-mediated endocytosis and Rab11. Mol Biol Cell 2004; 15: 4166–4178. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-03-0245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang MH, Li G, Liu J, et al. Nestin+ kidney resident mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of acute kidney ischemia injury. Biomaterials 2015; 50: 56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu RM, Vayalil PK, Ballinger C, et al. Transforming growth factor β suppresses glutamate-cysteine ligase gene expression and induces oxidative stress in a lung fibrosis model. Free Radic Biol Med 2012; 53: 554–563. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie N, Tan Z, Banerjee S, et al. Glycolytic reprogramming in myofibroblast differentiation and lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192: 1462–1474. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0780OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shichino S, Ueha S, Hashimoto S, et al. Transcriptome network analysis identifies protective role of the LXR/SREBP-1c axis in murine pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 2019; 4: e122164. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.122163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsukui T, Sun KH, Wetter JB, et al. Collagen-producing lung cell atlas identifies multiple subsets with distinct localization and relevance to fibrosis. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 1920. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15647-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonough JE, Ahangari F, Li Q, et al. Transcriptional regulatory model of fibrosis progression in the human lung. JCI Insight 2019; 4: e131597. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bueno M, Lai YC, Romero Y, et al. PINK1 deficiency impairs mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2015; 125: 521–538. doi: 10.1172/JCI74942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chabot A, Meus MA, Naud P, et al. Nestin is a marker of lung remodeling secondary to myocardial infarction and type I diabetes in the rat. J Cell Physiol 2015; 230: 170–179. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakairi T, Hiromura K, Yamashita S, et al. Nestin expression in the kidney with an obstructed ureter. Kidney Int 2007; 72: 307–318. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke X, Do DC, Li C, et al. Ras homolog family member A/Rho-associated protein kinase 1 signaling modulates lineage commitment of mesenchymal stem cells in asthmatic patients through lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143: 1560–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saboor F, Reckmann AN, Tomczyk CU, et al. Nestin-expressing vascular wall cells drive development of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 876–888. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00574-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birbrair A, Zhang T, Files DC, et al. Type-1 pericytes accumulate after tissue injury and produce collagen in an organ-dependent manner. Stem Cell Res Ther 2014; 5: 122. doi: 10.1186/scrt512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem 2009; 78: 857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayes S, Chawla A, Corvera S. TGF beta receptor internalization into EEA1-enriched early endosomes: role in signaling to Smad2. J Cell Biol 2002; 158: 1239–1249. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takei K, Haucke V. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: membrane factors pull the trigger. Trends Cell Biol 2001; 11: 385–391. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02082-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akhurst RJ, Hata A. Targeting the TGFβ signalling pathway in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012; 11: 790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hata A, Chen YG. TGF-β signaling from receptors to Smads. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016; 8: a022061. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crystal RG. Adenovirus: the first effective in vivo gene delivery vector. Hum Gene Ther 2014; 25: 3–11. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.2527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Malani N, Hamilton SR, et al. Assessing the potential for AAV vector genotoxicity in a murine model. Blood 2011; 117: 3311–3319. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McManus J, Cheng Z, Vogel C. Next-generation analysis of gene expression regulation – comparing the roles of synthesis and degradation. Mol Biosyst 2015; 11: 2680–2689. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00310E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell 2016; 165: 535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziegenhain C, Vieth B, Parekh S, et al. Comparative analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing methods. Mol Cell 2017; 65: 631–643. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svensson V, Natarajan KN, Ly LH, et al. Power analysis of single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments. Nat Methods 2017; 14: 381–387. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, et al. Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling. Am J Pathol 2012; 180: 1340–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosas IO, Kottmann RM, Sime PJ. New light is shed on the enigmatic origin of the lung myofibroblast. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 765–766. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1494ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hung C, Linn G, Chow YH, et al. Role of lung pericytes and resident fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 820–830. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2297OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassandras M, Wang C, Kathiriya J, et al. Gli1+ mesenchymal stromal cells form a pathological niche to promote airway progenitor metaplasia in the fibrotic lung. Nat Cell Biol 2020; 22: 1295–1306. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-00591-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Auyeung VC, Sheppard D. Stuck in a moment: does abnormal persistence of epithelial progenitors drive pulmonary fibrosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 203: 667–669. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202010-3898ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary methods and tables. ERJ-03721-2020.Supplement (361.5KB, pdf)

Supplementary figure S1. Nestin expression in experimental pulmonary fibrosis and RNA-seq data, and co-expression of Nestin and Collagen I, α-SMA, NG2, Calponin 1, CD31, SPC or AQP5 in mice lungs. a) Immunofluorescence staining of Nestin in lung sections from C57/BL6 mice on day 7, 14 and 21 days after bleomycin exposure. Scale bars: 100 μm. b) Quantification of Nestin-positive cells from immunofluorescent images in a) (n=6 mice per group; five fields assessed per sample). c) Nestin gene expression extracted from GSE110533 in mice fibrotic and control lung samples. d) Gating strategies of Nestin-GFP positive cells in myofibroblasts (both α-SMA+ and Collagen I+), pericytes (NG2+), smooth muscle cells (Calponin 1+), vascular endothelial cells (CD31+), type II alveolar epithelial cells (SPC+), or type I alveolar epithelial cells (AQP5+) respectively in flow cytometry analysis. e) Cell clusters of the sc-RNA-seq data from GSE132771. f) UMAP plot of all cells of the scRNA-seq data in e). g) UMAP plots of Hhip, Aspn, Acta2, Col1a1, Cspg4 and Cnn1 of the scRNA-seq data in e). Blue indicates high expression. h) UMAP of Nestin of the scRNA-seq data in e). i) Violin plot of Nestin expression in each cell cluster. Green box indicates myofibroblast cluster. Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S1 (2.5MB, tif)

Supplementary figure S2. Nestin expression in IPF and co-localisation of Nestin and Collagen I, NG2, Calponin 1, CD31, SPC or AQP5 in IPF lungs. a) Nestin gene expression extracted from GSE124685 in IPF and control lung samples. b) Cell clusters of the sc-RNA-seq data from GSE132771. c) UMAP plot of all cells of the sc-RNA-seq data from GSE132771 in IPF and normal conditions. d) UMAP plots of ASPN, COL1A1, POSTN and CTHRC1 of the scRNA-seq data in IPF. Blue indicates high expression. e) UMAP plots of NESTIN of the scRNA-seq data in IPF. Blue indicates high expression. f) Violin plot of NESTIN in each cell cluster. Red box indicates myofibroblast cluster. g) Immunofluorescence assay was carried out to determine the co-localization of Nestin (green) and NG2 (pericytes), Calponin 1 (smooth muscle cells), CD31 (vascular endothelial cells), SPC (type II alveolar epithelial cells) or AQP5 (type I alveolar epithelial cells) (red) respectively in IPF lungs. Scale bars: 40 μm. h) Semiquantitative scoring of double-positive cells as a percentage of Nestin-positive cells, as obtained from immunofluorescent images (n=6 per group; five fields assessed per sample). Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments; *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001; One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ERJ-03721-2020.Figure_S2 (4.2MB, tif)