Abstract

目的

探讨颧骨缺损不同治疗方法的修复效果及特点。

方法

选择2012年8月至2019年8月于北京大学口腔医院口腔颌面外科就诊的颧骨缺损行修复重建的37例患者。根据颧骨缺损涉及的部位, 将缺损分为四类: 0类, 缺损不涉及颧骨区段结构, 仅为厚度(突度)变化; Ⅰ类, 单个缺损位于颧骨体部或只涉及一个突起方向的缺损; Ⅱ类, 单个缺损累及两个突起方向; Ⅲa类, 单个缺损累及三个突起方向以上的缺损; Ⅲb类, 颧骨缺损同时累及相应上颌骨的大范围缺损。统计分析各类颧骨缺损的病因、缺损时间、缺损大小及特点、采用的修复重建方式, 并随访记录术后并发症等。术后CT评价颧骨突度及对称性恢复效果, 进行色谱差值分析评价术后稳定效果。

结果

本组患者中, 由创伤引起的颧骨缺损有25例(67.57%), 肿瘤切除引起的颧骨缺损有11例(29.73%), 另1例为骨发育畸形导致的颧骨缺损。19例患者行单纯自体骨移植修复, 6例患者行血管化组织瓣修复, 5例患者仅使用外植入物, 另外7例患者使用血管化组织瓣联合外植入物修复。导航组和非导航组健、患侧颧骨突度差值中位数分别为0.45 mm(0.20~2.50 mm)和1.60 mm(0.10~2.90 mm), 两组差值有统计学意义(P=0.045)。2例使用钛网结合股前外侧皮瓣修复的患者术后钛网发生明显变形或断裂, 2例铸造个性化钛修复术后因感染而取出。

结论

对于无明显结构改变的颧骨缺损, 可以用自体骨游离移植或异体材料修复。颧骨缺损存在骨支柱破坏、慢性炎症、口鼻腔相通或伴有明显软组织量不足时, 建议带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣或血管化骨组织瓣修复。钛网可用于修复大量骨组织缺损的病例, 同时建议联合血管化骨组织瓣移植修复。

Keywords: 颧骨, 骨和骨组织, 修复外科手术, 预后

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect and summarize the characteristics of different treatment methods in repairing zygomatic defect.

Methods

A total of 37 patients with zygomatic defect were reviewed in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology from August 2012 to August 2019. According to the anatomical scope of defect, the zygomatic defects were divided into four categories: Class 0, the defect did not involve changes in zygomatic structure or continuity, only deficiency in thickness or projection; Class Ⅰ, defect was located in the zygomatic body or involved only one process; Class Ⅱ, a single defect involved two processes; Class Ⅲa, referred to a single defect involving three processes and above; Class Ⅲb, referred to zygomatic defects associated with large maxillary defects. The etiology, defect time, defect size and characteristics of zygomatic defects, the repair and reconstruction methods, and postoperative complications were collected and analyzed. Postoperative computed tomography (CT) data were collected to evaluate the outcome of zygomatic protrusion. Chromatographic analysis was used to assess the postoperative stability.

Results

Among the causes of defects, 25 cases (67.57%) were caused by trauma, and 11 cases (29.73%) were of surgical defects following tumor resection. We performed autologous bone grafts in 19 cases, 6 cases underwent vascularized tissue flap, 5 cases underwent external implants alone, and 7 cases underwent vascularized tissue flap combined with external implants. After the recovery of the affected side, the average difference of the zygomatic projection between the navigation group and the non-navigation group was 0.45 mm (0.20-2.50 mm) and 1.60 mm (0.10-2.90 mm), with a significant difference (P=0.045). Two patients repaired with titanium mesh combined with anterolateral thigh flap had obvious deformation or fracture of titanium mesh; 2 patients with customized casting prosthesis had infection after surgery and fetched out the prosthesis finally.

Conclusion

Autologous free grafts or alloplastic materials may be used in cases without significant structural changes. Pedicle skull flap or vascularized bone tissue flap is recommended for zygomatic bone defects with bone pillar destruction, chronic inflammation, oral and nasal communication or significant soft tissue insufficiency. Titanium mesh can be used to repair a large defect of zygomatic bone, and it is suggested to combine with vascularized bone flap transplantation.

Keywords: Zygoma, Bone and bones, Reconstructive surgical procedures, Prognosis

颧骨位于面中部外侧,支撑面中部轮廓,同时承接面部受力的侧方垂直支柱和水平支柱[1]。颧骨的位置突出,易受外伤导致骨折,可能继发缺损及畸形;在上颌骨肿瘤行上颌骨扩大切除时通常也会造成一部分颧上颌突、眶下缘甚至颧骨体部缺损。目前,较少见针对颧骨缺损修复的研究,且研究多集中在如何修复颧面部外形。作为面中部承力的垂直支柱和水平支柱,颧骨会承担一部分上颌骨传导的咀嚼力及其骨面附着的肌肉的牵拉力,单纯的外形修复理论上可能存在远期稳定性的变化。此外,不同范围、部位的颧骨缺损的修复方式选择不同,其治疗效果是否一致也尚不清楚。

针对以上临床问题,本研究对颧骨缺损修复病例进行回顾性分析,总结颧骨缺损常见类型、临床常用修复方式和治疗效果。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究对象

回顾性分析2012年8月至2019年6月于北京大学口腔医院创伤中心接受颧骨缺损修复的病例。纳入标准:(1)因创伤、肿瘤切除、先天性原因引起单侧颧骨缺损或畸形,需进行修复或重建治疗的患者;(2)具备完整的临床和影像学资料;(3)随访时间超过6个月。排除肿瘤术后复发及术后行放疗、化疗的患者。本研究通过北京大学口腔医院生物医学伦理委员会批准(PKUSSIRB-201949138),患者均签署知情同意书。

收集患者一般资料,包括年龄,性别,缺损原因、时间、大小和部位,采用的修复重建方式以及手术是否采用导航引导数字化外科等。使用Excel2016(Microsoft,Redmond,WA)以表格格式收集数据,以便进行后续统计分析。

1.2. 颧骨缺损的分类

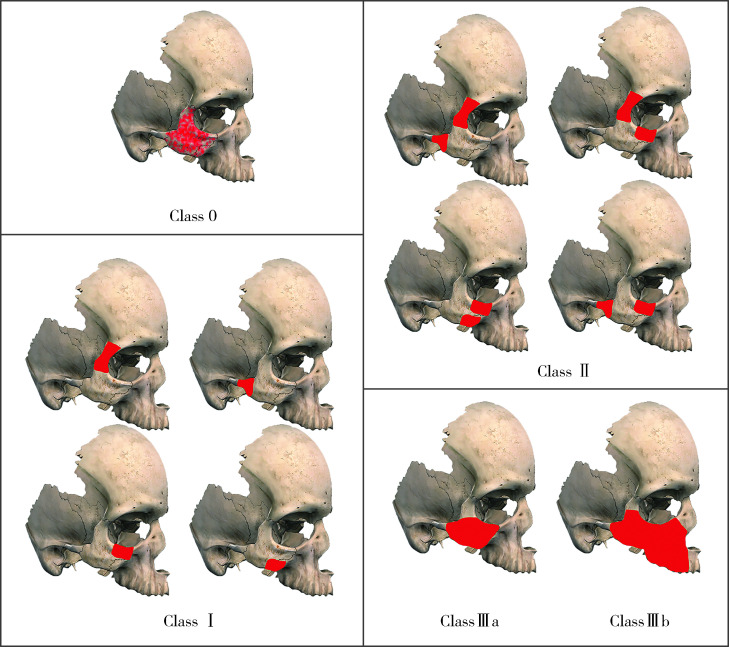

根据解剖结构将颧骨分为体部和4个突起(额蝶突、上颌突、颞突和眶突),根据缺损涉及的部位和大小将颧骨缺损分为4类(图 1):0类,缺损不涉及颧骨区段结构,仅为厚度(突度)变化;Ⅰ类,单个缺损位于颧骨体部或只涉及1个突起方向的缺损;Ⅱ类,单个缺损累及2个突起方向;Ⅲa类,单个缺损累及3个突起方向以上的缺损;Ⅲb类,颧骨缺损同时累及相应上颌骨的大范围缺损(即包括上颌骨Brown 3类)。

图 1.

颧骨缺损的分类

Classification of zygomatic defects

Class 0, defects does not involve changes in the zygomatic structure, and involves in only thickness or suddenness; Class Ⅰ, defects are located in the zygomatic body or involved only one process; Class Ⅱ, a single defect involving two processes; Class Ⅲa, a single defect involving three processes and above; Class Ⅲb, zygomatic defects are associated with large maxillary defects (including Brown 3).

1.3. 术后效果

1.3.1. 并发症

对患者进行随访,记录是否有继发感染、植入物暴露、继发畸形等手术并发症,以及同一病损是否需要后续手术。

1.3.2. 颧骨对称性

将患者术后CT数据以DICOM格式导入ProPlan CMF 3.0(Materialise,Bei-gium),进行阈值分割及三维重建,根据眶耳平面摆正头颅位置,过蝶鞍中心画对称平面,调整至横断面,在颧骨缺损修复层面上,以对称平面与枕骨前缘的交点记为原点,定义颧骨修复后移植中心到原点的距离为恢复突度,以平面对称的点到原点的距离为健侧参考突度,以测量双侧突度后相减得到的数值评估恢复效果,差值小于3 mm为重建恢复效果好(图 2)。同时根据术中是否采用导航辅助技术对Ⅰ~Ⅲa类缺损患者进行分组,并比较导航组和非导航组缺损修复后健、患侧颧骨突度的差值。

图 2.

术后颧骨突度测量

Postoperative zygomatic protrusion was measured

In ProPlan CMF 3.0, after calibration of the symmetric plane, the dif-ferences in the values of zygomatic arch protrusion on both sides were analyzed and compared.

1.3.3. 长期稳定性

将患者术后1周和6个月以上的CT数据以DICOM格式导入ProPlan CMF 3.0进行三维重建,以STL文件导入Geomagic Studio 12.0(Geomagic,USA),通过“N点对齐”结合“最佳拟合对齐”功能进行对齐配准,运用缺损修复区域色谱差值分析、评价修复术后长期稳定性。

1.4. 统计学方法

使用SPSS Statistic 20(IBM,USA)进行统计学分析。根据术中是否采用导航,对颧骨缺损修复术后健侧和患侧的突度差值进行Mann-Whitney U非参数检验,双侧P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 一般情况

本组共纳入患者37例,其中男性26例,女性11例,平均年龄39.0岁(9~77岁),病例平均随访时长19.7个月(6~84个月)。缺损时间最短者为肿物切除术后即刻修复,最长者为20年骨发育畸形导致的颧骨缺损。其中因创伤导致的25例缺损患者的平均缺损时间为23.4个月(最长达11年),有20例(80%)在1个月后选择修复。11例肿瘤患者中,5例在肿瘤切除同期修复(表 1)。

表 1.

不同颧骨缺损的基本信息

General information of different types of zygomatic bone defects

| Items | 0 (n=1) | Ⅰ (n=15) | Ⅱ (n=7) | Ⅲa (n=5) | Ⅲb (n=9) |

| CNTS, computer aided navigation technical surgery. Data are shown as n or M (range). | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 0 | 14 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Female | 1 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Age/years | 22 | 44 (23-77) | 41 (9-67) | 31 (22-40) | 36 (21-57) |

| Etiology | |||||

| Skeletal dysplasia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trauma | 0 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Tumor | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| CNTS | |||||

| Yes | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 9 |

| No | 0 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

2.2. 手术选择

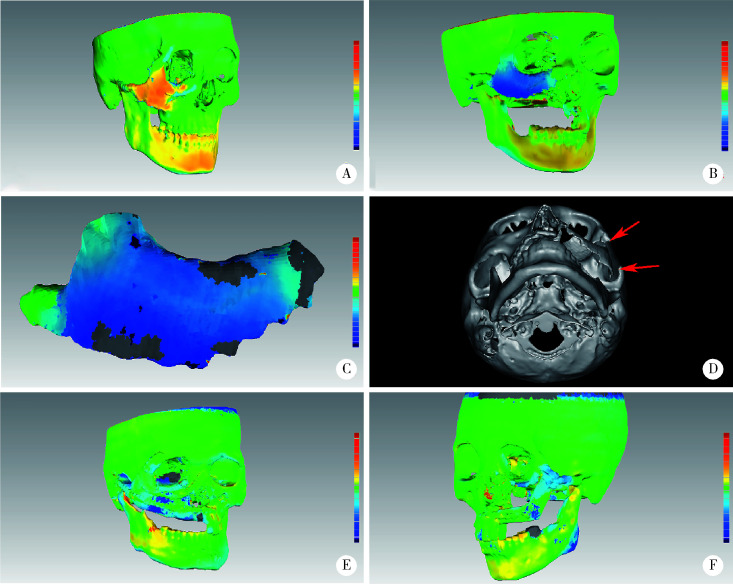

本组37例患者的修复方式如下:单纯自体骨游离移植19例(51.35%)、血管化组织瓣修复6例(16.22%)、外植入物修复5例(13.51%)、血管化组织瓣修复联合外植入物修复7例(18.92%)。自体骨游离移植的供骨区包括颅骨外板(图 3A)、肋骨、下颌骨颏部、喙突和髂骨;血管化组织瓣包括带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣(图 3B)、股前外侧皮瓣、血管化髂骨瓣(图 3C)和血管化腓骨瓣;外植入物包括钛网(0.6 mm,Symthes GmbH,Switzerland)、重建钛板(2.4 mm,Symthes GmbH,Switzerland)、铸造式修复体(图 4)。

图 3.

部分常用的修复手术方式

Some commonly used prosthodontic surgical methods

A, cranial bone grafts repair the continuity of the zygomatic arch; B, pedicled cranial bone flap was prepared and transferred to repair the zygomatic body; C, vascularized iliac crest bone flap was used to repair the defects of right zygomatic bone caused by trauma; D, the defect of right zygomatic ma-xillary bone was repaired using preoperatively bent titanium mesh; E, after tumor resection of right zygomatic-maxillary bone, the titanium mesh was used to repair the defects of zygomatic-maxillary bone; F, Ti-mesh + anterolateral femoral flap was used to repair the defects after tumor resection of the left zygomatic maxilla.

图 4.

铸造式个性化修复体

Customized casting prosthesis

A, the model of customized casting prosthesis of zygomatic-maxillary bone; B, under the guidance of intraoperative navigation, a customized titanium casting prosthesis was implanted into the zygomatic maxillary bone.

1例0类缺损患者采用颅骨外板移植修复。Ⅰ类缺损患者中13例为自体骨游离移植,其中最常使用的是颅骨外板,另有2例分别使用带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣和重建钛板修复。Ⅱ类缺损患者中5例为自体骨游离移植,另有2例使用带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣。Ⅲa类缺损患者中3例为铸造式修复体修复(图 4),另2例分别使用带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣和血管化髂骨瓣修复。Ⅲb类缺损患者中1例仅使用血管化髂骨瓣修复,另8例均使用钛网修复(图 3D、E),包括7例钛网结合血管化组织瓣修复(图 3F)。

此外,共25例(67.57%)患者术中采用导航辅助外科或数字化外科技术,包括全部14例Ⅲ类缺损患者。

2.3. 临床并发症

0类、Ⅰ类和Ⅱ类缺损的23例患者中,均无明显并发症发生。Ⅲa类缺损的患者中,1例行血管化髂骨瓣修复的患者术后出现软组织量不足;1例使用带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣修复的患者术后3个月仍存在骨组织量不足,随后使用多孔聚乙烯生物材料(Medpor,Porex Surgical Inc.,Newman,GA)植入以修复骨量不足;另有2例使用铸造式修复体的患者,术后1个月开始出现感染,同时植入物逐渐外露,经多次清创和抗炎治疗无效后,分别在术后1年和2年取出。

2.4. 对称性评价

回顾所有患者术后CT图像,患侧恢复的颧骨突度和健侧颧骨突度差值均在3 mm以内。在研究导航辅助技术对颧骨突度恢复的影响时,排除了钛网和铸造式修复体修复的病例,最终非导航组和导航组各纳入12例。研究结果表明,非导航组健、患侧颧骨突度差值中位数为1.60 mm(0.10~2.90 mm),导航组健、患侧颧骨突度差值中位数为0.45 mm(0.20~2.50 mm),两组差值有统计学意义(P=0.045)。

2.5. 稳定性评价

比较患者术后随访的CT结果,在Ⅰ类和Ⅱ类缺损中以自体骨游离移植和带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣修复的患者,术后CT表现均无明显变化,其中1例以颅骨外板游离移植的患者术后2年出现局部增厚(图 5A)。Ⅲb类缺损患者中以钛网结合股前外侧皮瓣修复的2例患者,1例术后2年钛网发生明显变形(图 5B、C),另1例术后2年钛网发生断裂(图 5D)。以钛网结合髂骨瓣修复的患者,术后髂骨密度发生不同程度减低(图 5E),但髂骨高度未发生显著变化,整体稳定性较好。以钛网结合血管化腓骨瓣修复的患者,术后1年无明显变化(图 5F),但同样有局部增厚的问题。

图 5.

运用色谱及CT数据进行稳定性分析

Chromatographic and CT data were used for stability evaluation

A, the defects of zygomatic temporal process and zygomatic orbital process after trauma were repaired with cranial bone grafts 2 years later, and chromatographic analysis showed overall thickening of the local thickness of the zygomatic bone; B, C, the defects of zygomatic maxilla were repaired using personalized pre-curved Ti-mesh and anterolateral femoral flap after resection of adenoid cystic carcinoma, and chromatographic analysis showed obvious deformation of titanium mesh 2 years later; D, 2 years after the repair of left zygomatic maxilla with Ti-mesh and anterolateral thigh flap, CT showed fracture of the titanium mesh at the zygomatic arch and zygomatic frontal suture; E, Ti-mesh combined with iliac crest bone flap was used to repair the defect of zygomatic maxillary bone, and chromatographic analysis showed that the local thickness of the ilium was decreased one year later; F, Ti-mesh combined with fibular flap was used to repair the defect of zygomatic maxillary bone, showing no significant changes one year later.

3. 讨论

本研究旨在分析不同颧骨缺损的修复方法和临床适应症。根据颧骨缺损的大小和部位,将本组37例患者分为4类不同的缺损类型,分析其采用的修复方法。

对于0类缺损的患者,没有颧骨结构和连续性的破坏,只有颧骨突度的改变。这一类的缺损修复,以自体骨移植[2]或外植入物修复[3]可以达到很好的手术效果。Medpor作为一种多孔的聚乙烯医用植入物材料,因其良好的生物相容性、组织安全性及较好的抗感染能力,在颌面部骨缺损修复重建中被广泛应用[4]。但对于大范围的缺损修复,Medpor可能存在强度不足的问题,而且相对来说仍有一定的感染风险,较适用于组织量少但结构连续的病例患者。

Ⅰ类和Ⅱ类缺损多为创伤来源的缺损,主要采用自体骨游离移植修复(18/22),其中绝大多数为颅骨外板移植修复。颅骨的结构包括外板、板障层和内板,在顶骨的平均总厚度约为7 mm[5-7]。颅骨的成骨方式为膜性成骨,与肋骨等其他自体骨供骨区的成骨方式不同,其优势在于有更好的机械和生物性能,移植后有更强的抗感染能力和更小的吸收率[8-9]。但因儿童患者颅骨板障层血运丰富,术中容易造成大量出血,应谨慎使用[6, 10];同样,在术前CT或MRI检查发现板障层狭小或缺如者也应禁用颅骨外板移植修复。

Ⅰ类和Ⅱ类缺损中,如局部伴发感染、炎症,或者暴露于鼻窦(如上颌窦),可以选择带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣修复。本组患者有3例使用带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣修复,术后均取得满意的修复效果。带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣由于表面骨膜和颞肌筋膜瓣的丰富血运而具有较好的抗感染能力。同时,带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣可提供一定数量的软组织用于修复相应的软组织缺损,因此,可用于局部血运较差及伴有高感染风险的缺损修复[11-12]。

目前,仍将显微外科皮瓣转移修复作为Ⅲ类缺损患者修复重建的金标准[13]。对于Ⅲb类的缺损,修复重建时往往还需要重建咬合功能,游离腓骨和带蒂髂骨瓣是主要选择[14],但这两种修复方式仍存在塑性不佳的问题,建议联合钛网使用。钛网可以根据打印模型进行术前预弯[15-17],恢复患者术后的面型,CT结果也提示可达到满意效果。在Ⅲ类缺损中,若单独使用钛网修复,由于强度不够可能存在钛网变形或断裂风险。本组8例使用钛网修复的患者中,5例联合使用带蒂髂骨瓣或血管化腓骨瓣修复,均取得良好的效果,其中3例已完成牙列种植和咬合重建。髂骨瓣的优势是供骨量大,最大可以提供10 cm×3 cm的全厚髂骨[14],缺点是提供的软组织量较少,并发症较多[18]。同时,对Ⅲb类缺损患者,尤其是肿瘤来源的颧骨缺损,往往还伴有周围大量软组织的缺失,因此,与髂骨瓣相比,腓骨肌皮瓣有着不可替代的优越性[19-20]。

另外,个性化修复体在临床应用中因不存在供区损伤,不受供区的影响而具有独到的优势,早在2011年,国外就有3D打印个性化下颌骨修复体成功应用的报道[21]。本组有3例患者采用个性化铸造式颧骨钛修复体,其中2例术后发生了感染暴露,最终将修复体取出。感染的原因可能有两个方面:一是内在因素即软组织覆盖的问题,病损区域往往会伴有软组织的缺损,因此,在植入修复体的同时应考虑结合血管化软组织瓣等方式在修复体表面形成软组织覆盖;二是钛合金的弹性模量较大,在骨-修复体界面将产生应力屏蔽,造成界面的骨吸收,同时引起修复体的松动[22-23]。随着3D打印技术的发展与应用,制造结构更为复杂、立体多孔的修复体变成可能。多孔修复体的优势在于可以在减少质量的同时,优化材料的力学性质,为组织和骨的长入提供条件。

综上,本研究提出可根据颧骨的解剖结构将颧骨缺损分为4类。0类颧骨缺损患者采用自体骨移植或外植入物移植修复可达到较为满意的效果。Ⅰ类、Ⅱ类颧骨缺损患者的修复方式以自体骨游离移植为主,首选颅骨外板移植修复;当有较高感染风险或软组织量不足时,建议使用带蒂颅骨骨膜瓣修复。Ⅲ类颧骨缺损患者,可以选择钛网恢复面部外形,同时结合血管化骨瓣恢复硬组织结构以维持长期稳定。对于同时伴有大范围软组织缺损的患者,建议钛网结合血管化游离腓骨瓣修复。

Funding Statement

国家重点研发专项(2017YFB1104103)

Supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (2017YFB1104103)

References

- 1.Kokemueller H, Tavassol F, Rücker M, et al. Complex midfacial reconstruction: A combined technique of computer-assisted surgery and microvascular tissue transfer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66(11):2398–2406. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zunz E, Blanc O, Leibovitch I. Traumatic orbital floor fractures: Repair with autogenous bone grafts in a tertiary trauma center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(3):584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.白 萍, 刘 和荣, 郝 月军. Medpor在眼眶重建和眼球内陷复位手术中的应用. 中国美容医学. 2004;13(3):353–354. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-6455.2004.03.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butscher A, Bohner M, Hofmann S, et al. Structural and material approaches to bone tissue engineering in powder-based three-dimensional printing. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(3):907–920. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pensler J, McCarthy JG. The calvarial donor site: An anatomic study in cadavers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(5):648–651. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz NR. Cranial bone grafting in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123(7):206–211. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1992.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatum SA, Kellman RM. Cranial bone grafting in maxillofacial trauma and reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg. 1998;14(1):117–129. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusiak JF, Zins JE, Whitaker LA. The early revascularization of membranous bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(4):510–516. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers GF, Greene AK. Autogenous bone graft: Basic science and clinical implications. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(1):323–327. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318241dcba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Movahed R, Pinto LP, Morales-Ryan C, et al. Application of cranial bone grafts for reconstruction of maxillofacial deformities. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2013;26(3):252–255. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2013.11928973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandervord JG, Watson JD, Teasdale GM. Forehead reconstruction using a bi-pedicled bone flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1982;35(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(82)90090-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He W, Gong X, He Y, et al. Application of a lateral pedicled cranial bone flap for the treatment of secondary zygomaticomaxillary defects. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(7):e661–e664. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerressen M, Pastaschek CI, Riediger D, et al. Microsurgical free flap reconstructions of head and neck region in 406 cases: A 13-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(3):628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghassemi A, Ghassemi M, Riediger D, et al. Comparison of donor-site engraftment after harvesting vascularized and nonvascularized iliac bone grafts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(8):1589–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takano M, Sugahara K, Koyachi M, et al. Maxillary reconstruction using tunneling flap technique with 3D custom-made titanium mesh plate and particulate cancellous bone and marrow graft: A case report. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;41(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s40902-019-0228-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghanaati S, Al-Maawi S, Conrad T, et al. Biomaterial-based bone regeneration and soft tissue management of the individualized 3D-titanium mesh: An alternative concept to autologous transplantation and flap mobilization. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019;47(10):1633–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2019.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang WB, Yu Y, Mao C, et al. Outcomes of zygomatic complex reconstruction with patient-specific titanium mesh using computer-assisted techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(9):1915–1927. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mischkowski RA, Selbach I, Neugebauer J, et al. Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and iliac crest bone grafts: Anatomical and clinical considerations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35(4):366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei FC, Celik N, Yang WG, et al. Complications after reconstruction by plate and soft-tissue free flap in composite mandibular defects and secondary salvage reconstruction with osteocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(1):37–42. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000065911.00623.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidalgo DA, Pusic AL. Free-flap mandibular reconstruction: A 10-year follow-up study. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(2):438–449. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nickels L. World's first patient-specific jaw implant. Metal Powder Report. 2012;67(2):12–14. doi: 10.1016/S0026-0657(12)70128-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macheras G, Kateros K, Kostakos A, et al. Eight- to ten-year clinical and radiographic outcome of a porous tantalum monoblock acetabular component. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(5):705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehouse MR, Masri BA, Duncan CP, et al. Continued good results with modular trabecular metal augments for acetabular defects in hip arthroplasty at 7 to 11 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):521–527. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3861-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]