Summary

Identification of rare-variant associations is crucial to full characterization of the genetic architecture of complex traits and diseases. Essential in this process is the evaluation of novel methods in simulated data that mirror the distribution of rare variants and haplotype structure in real data. Additionally, importing real-variant annotation enables in silico comparison of methods, such as rare-variant association tests and polygenic scoring methods, that focus on putative causal variants. Existing simulation methods are either unable to employ real-variant annotation or severely under- or overestimate the number of singletons and doubletons, thereby reducing the ability to generalize simulation results to real studies. We present RAREsim, a flexible and accurate rare-variant simulation algorithm. Using parameters and haplotypes derived from real sequencing data, RAREsim efficiently simulates the expected variant distribution and enables real-variant annotations. We highlight RAREsim’s utility across various genetic regions, sample sizes, ancestries, and variant classes.

Keywords: rare variants, simulated data, simulated genetic variants, RAREsim

Introduction

Studies of rare variants are important if researchers are to gain a full understanding of the genetics of health and disease; such studies inform targeted drug development and precision medicine. Rare variants (minor-allele frequency [MAF] < 1%) have been associated with traits across many diseases, including kidney, neurodevelopmental, cardiovascular, and infectious diseases and cancer. With decreasing sequencing costs, rare-variant data are increasingly accessible,1 resulting in large sequencing studies (e.g., >35,000; >45,000; and >70,000 subjects), databases including the UK Biobank, GenomeAsia, and NIH programs such as the Genome Sequencing Program (GSP) and Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed). Researchers continue to develop rare-variant methods (e.g., SKAT-O, iECAT, ProxECAT, and ACAT) to take advantage of the ever-increasing sequencing data.

Simulation studies enable evaluation of methods and study design (e.g., estimates of power and sample size) in known and controlled settings. Simulations that do not adequately mirror essential properties of real data might have issues generalizing to real data, potentially resulting in incorrect conclusions of method efficacy or power. In general, four qualities are necessary in rare-variant simulations of a genetic region: (1) allele-frequency spectrum (AFS), (2) total number of variants, (3) haplotype structure, and (4) variant annotation. To our knowledge, no existing rare-variant simulation method currently incorporates all four qualities.

-

(1)

AFS is the distribution of variant-allele frequencies within a genetic region. Numerous studies have shown that the AFS is skewed toward very rare variants; the vast majority of variants are singletons and doubletons.2, 3, 4

-

(2)

The total number of variants, especially very rare variants, differs by ancestry and sample size. The total number of known variants is expected to increase as more ancestrally diverse and larger samples are sequenced.5,6

-

(3)

Haplotype structure, which is the linkage disequilibrium (LD) and the probability that rare single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) appear on the same haplotype background, varies across the genome and by ancestry.

-

(4)

Variant annotation is often used in rare-variant methods and is thus essential for accurate evaluation of those methods. For instance, weighting functional variants has been shown to increase the power to detect rare-variant association in a gene region.1,7,8 Other variant annotation, such as association with disease, is used to evaluate pleiotropy and in genetic correlation and polygenic risk scores. A great variety of variant annotation exists such as functional consequences, conservation score, chromatin state, eQTLs, epigenetic information, and prior disease associations, among other annotations.9 Although in silico simulation of variant annotation can capture and emulate some annotation patterns, simulations derived from real data can easily incorporate precise empirical patterns from multiple annotation types, even those unique to a specific genetic region of interest, providing a more direct link between simulations and real data.

Population-genetics simulation methods, such as the Wright-Fisher10,11 and coalescent methods,12 require only demographic and recombination information as inputs and often achieve an AFS, total number of variants, and LD structure similar to those of real data. However, these methods can be extremely computationally expensive or are not designed to emulate existing genetic regions, resulting in an inability to use real-variant annotations. By contrast, resampling methods create haplotype mosaics from real genetic data by using techniques that mimic recombination and mutations, maintaining the ability to use existing annotations. These methods, such as HAPGEN2, derived from the original work of Li and Stephens,13 are relatively computationally efficient and maintain the appropriate AFS, expected number of variants, and haplotype structure when simulating common variants.14,15 However, as we and others16 show, HAPGEN2 does not simulate the correct total number or AFS for rare variants and thus simulates too few rare and very rare variants (e.g., singletons and doubletons). There is currently no available software that simulates rare-variant genetic data with a realistic AFS while retaining variant annotation.

To address this gap, we present RAREsim, a flexible and scalable genetic simulation method designed for accurate simulation of rare variants. We assess and show the utility of RAREsim across a variety of genetic regions, datasets, ancestries, and sample sizes. We provide RAREsim as an R package to enable easy implementation and appropriate simulation of rare-variant data.

Material and methods

Algorithm

RAREsim uses two primary datasets: input simulation data and target data. The input simulation dataset is a sample of haplotypes (e.g., 1000 Genomes haplotypes3) with minor alleles coded as 1 and all reference alleles, including monomorphic bases, coded as 0. The target dataset is summary-level data used for estimating RAREsim parameters. The target data has two components: the allele count at each variant and the total number of variants in a genetic region of interest at various sample sizes (e.g., downsamplings from gnomAD2). Although the input simulation dataset is required, the target dataset is not necessary if default or user-defined parameters are used.

RAREsim has three main steps: (1) simulating haplotypes, (2) estimating the expected number of variants, and (3) pruning rare variants to match the expected number. A flowchart summarizing the RAREsim algorithm is in Figure 1.

-

(1)

Simulating an abundance of rare variants. RAREsim uses HAPGEN214 to simulate haplotypes for individuals. HAPGEN2 simulates haplotypes by creating mosaics of input and already simulated haplotypes by using recombination information so that regional LD is retained for common variants.14,15 When all sequencing bases, including monomorphic bases, are included in the input haplotypes, HAPGEN2 (i.e., HAPGEN2 with all bp) simulates more de novo variants than expected. De novo mutations are added to each haplotype with a probability based on the mutation rate. Each simulated haplotype is added to the sample of haplotypes from which new haplotypes are simulated. Thus, in addition to arising from novel mutations, simulated de novo mutations with more than one allele in the sample might arise from resampling of the set of previously simulated haplotypes. The probability that a rare allele is chosen from the haplotype sample is much larger than the de novo mutation probability (probabilities provided in the supplemental methods). Thus, just as in real data, a rare allele observed in multiple subjects is likely to be on the same haplotype background.

-

(2)

Estimating the expected number of variants per minor-allele count (MAC) bin. The number of variants per MAC bin is estimated via two functions. The parameters for these functions are estimated from target data (described below). Alternatively, user-defined or default parameters can be used, eliminating the need for the user to provide and fit target data. The default parameters were derived from the default target data.

-

(2a)

“Number of variants” function. The total number of variants in a region depends on the sample size. RAREsim estimates the expected number of variants per kilobase (Kb) for a sample size by using the “number of variants” function. Specifically,

Figure 1.

Flowchart of RAREsim

Flowchart describing the RAREsim simulation process. Simulation parameters can be estimated from target data, default parameters, or user-defined parameters (gray).

∗Haplotypes must include information at all sequencing bases to allow for an abundance of variants for subsequent pruning.

where is the number of variants per Kb for individuals. The parameters and are estimated to modify the scale and shape of the function, respectively. When simulating individuals, RAREsim calculates the total number of variants in the region by multiplying the size of the region in Kb, by the expected number of variants per Kb,

The target data used for the “number of variants” function provides the observed number of variants per Kb, , in the simulation region as observed at sample size . The parameters are optimized by minimization of a least-squares loss function summed over all observed sample sizes in the target data:

Sequential quadratic programming (SQP) via the slsqp function in the nloptr R package17 is used with constraints and to minimize the loss function. The initial starting values for the algorithm are and such that the largest observed sample size, , fits the observed number of variants per Kb at , . If the initial starting values do not result in a sufficient fit (loss > 1,000), a range of starting values are evaluated: .

-

(2b)

Allele frequency spectrum function (AFS Function). The AFS function, , estimates the proportion of variants with MAC . The largest MAC, , has MAF 1% in the target dataset. For a target dataset with individuals, . Specifically,

The scale parameter ensures that the sum of all individual rare MAC proportions equals the total proportion of rare variants observed in the target data, The classic model for the allele frequency spectrum,18 , is used as the base function, and parameters and determine the shape of the distribution.

Because individual MAC might have no observed minor alleles in the target data, particularly for higher rare MACs (e.g., MAC = 10, 11, 12), MAC bins are used for optimizing parameters. MAC bins are mutually exclusive, exhaustive groups of rare MACs. Seven MAC bins are used here: singletons, doubletons, MAC = 3–5, MAC = 6–10, MAC = 11–20, MAC = 21to MAF = 0.5%, and MAF = 0.5%–1%, denoted as respectively. The total number of bins and thresholds by which bins are defined can be modified by the user. Within each bin j, the estimated proportion of variants is compared to the observed proportion of variants in the target data, . is the observed proportion of variants with MAC . SQP17 is used for obtaining parameter estimates for and via minimization of the least-squares loss over all bins, where :

-

(2c)

Expected number of variants per MAC bin. RAREsim uses the total number of variants within a genetic region for individuals, , and the proportion of variants in to obtain the expected number of variants in each MAC bin, ,

The expected total number of rare variants is calculated by summation across all rare MAC bins.

The total number of simulated rare variants is calculated by summation over all MAC bins.

-

(3)

Pruning. As described in (1), simulations using HAPGEN2 usually result in a larger total number of simulated rare variants than expected from step (2). The algorithm prunes simulated variants by retuning all or a subset of alternate alleles to reference alleles. Within HAPGEN2 and similar-to-real haplotypes, rare alleles have a high probability of being on the same haplotype background. Pruning alternate alleles preserves the high likelihood that rare alleles are on the same haplotype. Variants are probabilistically pruned, creating variability over the simulation replicates in the number of variants per MAC bin.

RAREsim sequentially prunes variants from high to low MAC bins, starting with the highest rare MAC bin that has at least 10% more simulated variants than expected (i.e., ).

-

(1)

For MAC bins with more simulated variants than expected, a simulated variant is pruned with probability , where

For each variant within the bin, RAREsim randomly draws from a uniform(0,1) distribution. If the draw is within , the variant is pruned. The location of a pruned variant is stored to allow variants to be added back at lower MAC bins that have fewer simulated variants than expected, as described in the next section.

(2) For MAC bins with fewer simulated variants than expected (i.e. ), each of the previously pruned variants from higher MAC bins are added to with probability

Random draws from the uniform(0,1) distribution are used for determining which variants to add. The variant is added if the draw is within The MAC for each added variant is determined with a random sample from all possible MACs within RAREsim then randomly samples, without replacement, the necessary number of haplotypes containing the alternate allele for the given variant. The allele for all other haplotypes is returned to reference.

Input simulation datasets

For the input simulation dataset, we used haplotypes, legend files (an accompanying variant list), and a recombination map from 1000 Genomes phase 3 (hg19).3 The files were modified to include information at each sequencing base. The recombination map was derived from the combined sample of all ancestries (OMNI).3 Links to these resources are in Table S1.

For the simulation haplotypes, African, East Asian, non-Finnish European, and South Asian global ancestries were used without inclusion of admixed African samples (African Caribbeans in Barbados [ACB] and Americans of African ancestry in Southwest Utah [ASW]). HAPGEN2 simulates biallelic SNVs. Hence, we omitted indels present in the 1000G haplotypes. For multiallelic SNVs, we kept the first alternate allele with at least one observed alternate allele in the legend file.

Target datasets

Exome sequencing data from gnomAD v2.12 on chromosome 19 were used as target data to estimate the simulation parameters. For the “number of variants” function, the observed number of loss-of-function, synonymous, and missense variants classified by gene, ancestry group, and sample size (e.g., 500, 1000, 2000, 5000, etc.) from Karczewski et al.2 was used (link in Table S1). The number of variants for all three function classification groups were summed to provide the total number of variants observed per gene. The GENCODE v19 file19 (link in Table S1) contains the genomic positions of the canonical transcript coding regions that Karczewski et al.2 used to define genes. The total number of variants within the simulation region of interest was found through summation over all genes in the region. When a region contained overlapping genes, the proportion of overlap was calculated and removed from one gene so that variants would not be counted twice.

For the AFS target data, allele counts for biallelic SNVs in the coding region of canonical transcripts for four ancestry groups from gnomAD v2.1 were used (African, n = 8,128; East Asian, n = 9,197; non-Finnish European, n = 56,885; South Asian, n = 15,308)2 (link in Table S1). We observed slight discrepancies for some regions in the total number of variants between the gnomAD v2.1 data used for the AFS target data and the gnomAD downsampling data used for the “number of variants” target data (Figure S1). Differences in the number of variants per gene most likely arise as a result of inconsistencies between the two datasets with respect to classification of variant function removal of overlapping genes, and a few other differences. The discrepancies did not substantially affect the simulation results, as shown when the simulated haplotypes are compared to the gnomAD data (Results).

Centimorgan blocks

Chromosome 19 was divided into 1 cM blocks for simulation. The cM blocks were defined on the basis of the 1000 Genomes Project recombination map estimated from the combined set of all ancestries3 (“input simulation datasets”). Blocks were restricted to the coding region of the canonical transcript for each gene. Genes that overlapped multiple blocks or were between cM blocks (the recombination map did not contain information at all base pairs) were included with the previous cM block. Of the 107 cM blocks, two blocks did not meet the requirement of containing at least two genes (blocks 17 and 23). Additionally, there were four blocks (blocks 8, 50, 57, and 92) with fewer than 100 SNVs in at least one ancestry in the gnomAD target data. These six blocks were merged with the preceding adjacent block, resulting in 101 blocks for simulation (Table S2). Blocks ranged from 3,183 bp to 81,253 bp (median = 19,029; Q1 = 11,037; Q3 = 27,204).

Implementation of RAREsim

We implemented RAREsim for a genetic region of interest by using the computing flowchart shown in Figure S2. First, we modified the input haplotype and legend files to include all base pairs, including monomorphic bases. Then, we simulated haplotypes for each cM block by using HAPGEN214 with default parameters. The relative risk was set to 1.0; hence, no disease loci were simulated. The random seed in HAPGEN2 is set by time. Therefore, simulation replicates cannot be run in parallel across multiple cores at the same time. To avoid this, we simulated replicates for the same simulation scenario on the same computing core in series. Alternatively, the “pause” Bash command could be used for simulating haplotypes in parallel. Then, we calculated the expected number of variants per MAC bin by using the “expected_variants” RAREsim function with either default simulation parameters or region-specific simulation parameters estimated withthe “fit_afs” and “fit_nvariants” functions. We used the RAREsim python package to convert the simulated haplotypes into sparse matrices by using convert.py. Finally, we pruned the haplotypes and legend files by using sim.py.

Evaluation of “allele frequency spectrum” and "number of variants" functions

In our application, parameters for the “number of variants” and AFS functions were estimated for each of the 101 blocks and four ancestry groups from gnomAD. To evaluate how well the “number of variants” function fit the target data, we calculated the relative difference for the observed target data at the sample size available in gnomAD, , to the “number of variants” function estimate, . The relative difference was calculated as

We evaluated fit of the AFS function with the difference between the estimated proportion of variants, , and the observed proportion in gnomAD, , for each MAC ,

Default function parameters

We calculated ancestry-specific default parameters by using the median target data over all blocks (i.e., median number of variants per Kb at each sample size [“number of variants” function] and median proportion of variants in each MAC bin [AFS function]). For the “number of variants” function, we used the 5th and 95th percentile observations over the 101 blocks to estimate 5th and 95th percentile functions.

Evaluation of simulation results

One hundred replicates of each block were simulated for the gnomAD sample size of each ancestry group . The matched sample size enabled a direct comparison between gnomAD and simulated data because sample size greatly influences the number of variants expected in MAC bins. We compared RAREsim to the default implementation of HAPGEN2 with only polymorphic SNVs in the input simulation data and to HAPGEN2 using all base pairs, including monomorphic base pairs. Each block was simulated and pruned independently. To evaluate simulations from chromosome 19 as a whole, we summed the variant counts for each MAC bin over all cM blocks.

COSI comparison

RAREsim was compared to COSI,20 a coalescent simulator. Haplotypes from African and non-Finnish European ancestries were simulated to match the sample sizes observed in gnomAD (nAFR = 8,128 and nNFE = 56,885) for the block with the median number of base pairs. Schaffner et al.20 provides “bestfit” COSI simulation parameters for various ancestries, including African and European. COSI was implemented with these default parameters (referred to as COSI) as well as with a specified number of mutation sites observed in the target gnomAD data (referred to as COSI—matched Nvariants). Ten COSI replicates were simulated per ancestry. Default parameters were used for the ten RAREsim replicates for each ancestry.

Correlation of simulated individuals

To evaluate whether RAREsim might increase the correlation between individuals in the simulated sample, we compared the identity-by-state (IBS) measurements from 1000 Genomes data to IBS estimates from ten RAREsim replicates. We matched ancestry and sample size and used the cM block with the median number of bases. We performed RAREsim simulations for the ancestry-specific sample size observed in gnomAD v2 and then performed subsampling so we could match the sample size of the 1000 Genomes reference data for comparison (African: n = 504; East Asian: n = 504; non-Finnish European: n = 404; South Asian: n = 489). We used the “distance square ibs” command in PLINK v1.921 to calculate IBS and compared pairwise IBS estimates by using summary statistics (e.g., mean, median, min, max); these estimates are not intended for an interpretable measure of relatedness in this scenario.

Ancestry-specific linkage disequilibrium

To evaluate whether ancestry-specific LD was maintained by RAREsim for common variants, we restricted variants to 40 that were within one LD block and were common (MAF ≥ 1%) in all four ancestries within the 1000 Genomes reference data. We then calculated the pairwise r2 for each variant pair by using the PLINK v1.921 “r2 square” command. Pairwise r2 was calculated for the 1000 Genomes reference data and a RAREsim replicate of the region that matched the ancestry-specific sample size of the 1000 Genomes data.

To evaluate LD for rare and low-frequency variants, we calculated pairwise r2 and D` for all variants with MAC = 5 to MAF 1%. We used PLINK to calculate pairwise r2 as previously described for common variants, and the "r2 dprime" command was used to calculate pairwise D`. The calculations were performed for the 1000 Genomes data and ten replicates of RAREsim simulated data. For simulations of RAREsim replicates, the sample size and rare MACs observed in 1000 Genomes for each ancestry were matched.

Generalizability of default parameters

Generalizability of default parameters was assessed on different chromosomes, for other sample sizes, in an intergenic region, and in another dataset. To evaluate the performance of the default parameters for other chromosomes, we simulated GENCODE regions on chromosomes 1, 6, and 9, which were chosen to be representative of the genome19 (Table S3). As with the blocks on chromosome 19, the regions were restricted to canonical coding exons. These blocks were each 500 Kb, but when restricted to the coding region, they were 24,918; 12,519; and 17,051 bp on chromosomes 1, 6, and 9, respectively.

We used whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data from gnomAD v3 to evaluate the performance of default parameters for different sample sizes and for intergenic regions. To evaluate default parameters for different sample sizes, we simulated three blocks (5th, 50th, and 95th percentile blocks for number of variants) for the African ancestry group (n = 21,042 for v3 compared to n = 8,128 for v2.1) and non-Finnish European ancestry group (n = 32,299 for v3 compared to n = 56,885 for v2.1). To evaluate the utility of default parameters for intergenic regions, we simulated intergenic regions within the three blocks and limited these to the original coding-region size.

Finally, to evaluate performance of the default parameters in another dataset and sample size, we simulated a non-Finnish European sample to match the UK Biobank.22 Because of an error in the UK Biobank 50K release, the 95th percentile block contained missing data; thus, we used the 5th, 50th, and 94th percentile blocks instead. We simulated 41,246 non-Finnish European individuals, which was the number of individuals in the exome-sequencing British sample after ethnic outliers were removed.

Stratified simulation of functional and synonymous variants

To demonstrate RAREsim’s ability to simulate different types of variants, such as variants in different functional classes, variants were stratified and simulated by functional and synonymous status. The reference and alternate allele are required for variant annotation. For polymorphic variants within gnomAD, the observed reference and alternate alleles were used. We annotated monomorphic base pairs in gnomAD by using all possible alternate alleles with the convert2annovar function in ANNOVAR.23 To restrict to one alternate allele, we first annotated each allele as a transition or transversion. Within the exome, Wang et al.24 observed transition to transversion ratios (Ti/Tv) between 2.79 and 2.84 across ancestries. Here, we used the average Ti/Tv of 2.815 to calculate the probability (0.7379) of a transition for each variant. For each monomorphic base pair, we performed a random draw from a Uniform(0,1) distribution. If the random draw was within , the transition alternate allele was used. Otherwise, the variant was annotated as a transversion, and the alternate allele was assigned randomly from the two possible alternate alleles.

Variants were annotated with Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP)25 release 100. For variants with multiple annotations, the most severe consequence was chosen via the “most severe consequence” filter in VEP. Synonymous variants were those annotated as synonymous. Matching gnomAD’s annotation,2 functional variants were those annotated as missense, frameshift, splice-site disrupting, and stop gained. Stratified simulation, including both refitting target data and pruning separately for each variant class (i.e., functional vs synonymous), was performed for the block with the median number of base pairs.

Simulation of large sample sizes

We fit the “number of variants” function to the median cM block for the total gnomAD v2.1 sample (n = 125,748) and compared the fitted, ancestry-specific “number of variants” functions extrapolated to large sample sizes.

Computing time

Computing time was evaluated on an Ubuntu 18.04.2 LTS desktop with Intel Core TM i7-6700 CPG at CPU 8 × 3.40 Ghz. The desktop is 64 bit with 1.1 TB (disk) GNOME 3.28.2 and 32 GB RAM. For each ancestry, the simulation time for the cM block with the minimum (3,183), median (19,029), and maximum (81,235) bp was recorded. To re-evaluate the simulation of haplotypes with HAPGEN2 with more memory, we used a Dual Intel Xeon E5-2670v2 (2.5 Ghz × 10 cores, each), 192GB PC3-12800R RAM (12 × 16 GB sticks).

Results

Evaluation of ‘number of variants’ and ‘allele frequency spectrum’ functions

Parameters for the AFS and “number of variants” functions were estimated for each block for the four ancestry-and-sample-size groups (Table S4). The ancestry- and sample-size-specific fitted “number of variants” function closely matches the observed values for all four ancestries (Figures 2 and Figure S3). 90% of cM blocks had a relative difference within 2.42% for the estimated versus observed number of variants per Kb. The average relative difference for all ancestries was [90% CI = ], an overestimation of 0.92 variants. Ancestry-specific averages were [African, 90% CI = ], [East Asian, 90% CI = ], (non-Finnish European, 90% CI = , and [South Asian, 90% CI = ] (Figure S4). The negative mean relative differences indicate a slight but systematic overestimation of the number of variants per Kb for most blocks. Although systematic, the overestimation is small. Of the 404 cM blocks across the ancestries (1,616 blocks in total), only four have a difference of more than four variants. These four blocks each had at least 143 variants per Kb (maximum 179 variants per Kb) and were all non-Finnish European. Within a given target dataset, the “number of variants” function appears to slightly overestimate the observations of larger sample sizes and underestimate the observations of smaller sample sizes (Figure S3).

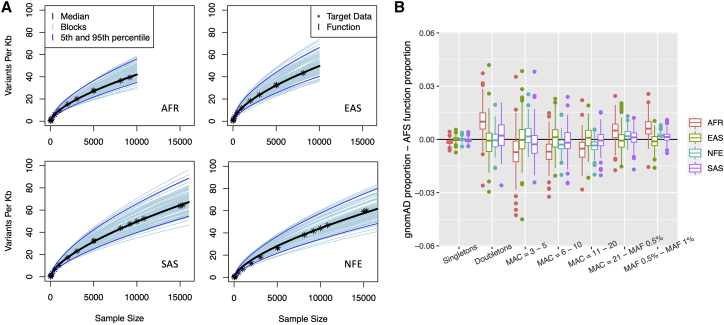

Figure 2.

Evaluation of function fit

(A) “Number of variants” function: fitted “number of variants” functions for all cM blocks. The median block is shown in black, and the 5th and 95th blocks are shown in dark blue. The observed target data (∗) for the median block are close to the fitted function for all four ancestries. Sample sizes up to 15,000 are shown here. The full sample size for the non-Finnish European sample is in Figure S3.

(B) AFS function: difference between the gnomAD target data and estimates from the AFS function for the proportion of variants in each MAC bin for all chromosome 19 blocks by ancestry and MAC bin. All absolute differences are within 0.05, indicating the AFS function fits the target data well.

Observed and estimated variation in the number of variants per Kb across cM blocks increases with sample size (Figure 2A). However, even for the largest available target data sample size (non-Finnish European, n = 56,885), the variability of the number of variants per Kb remains low; 90% of the block-specific estimates are within 35 variants of the median estimate.

The AFS function matched the observed data well and showed no apparent systematic bias. The average absolute difference between the observed and estimated proportion of variants in each MAC bin over all ancestries, blocks, and MAC bins was 0.53% [90% CI = (0.51%, 0.55%)] (Figure 2B). 90% of the estimated proportions were within 1.3% of that observed. The maximum absolute difference in MAC bin proportion was 4.50% (observed in East Asian, MAC 3-5). Singleton counts matched particularly well and had a maximum absolute difference of 0.73%.

Despite different ancestries and widely different sample sizes (from n = 8,128 to n = 56,885 for African and non-Finnish European, respectively) the proportion of variants per MAC bin were similar (Figure S5). There is more variation between ancestry-and-sample-size groups for the total proportion of rare variants (i.e., proportion of all variants with MAF < 1%) (Figure S6). Regardless, within each ancestry, variation of the AFS between cM blocks remains small. For instance, 90% of the blocks in the MAC bin with the most variation (East Asian singleton bin) have estimated proportions within 6.3% of the median.

Evaluation of simulation results

One hundred replicates of each block were simulated with RAREsim and HAPGEN2, and the gnomAD v2.1 sample size was matched for each ancestry group (Figure 3). The number of variants produced by RAREsim was similar to that produced by gnomAD across all ancestry groups and MAC bins, indicating that the total number of variants and AFS are representative of real sequencing data. Conversely, HAPGEN214 with only polymorphic SNVs greatly underestimated the total number of rare variants, especially very rare variants. HAPGEN2 simulations including all sequencing bases produced many more rare variants than observed. These results are consistent across all cM blocks and for the cumulative chromosome 19 coding region (Figures S7–S10 and Tables S5–S8).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of RAREsim

The distribution and number of variants simulated via RAREsim (pink), HAPGEN2 with only polymorphic SNVs (default, green), and HAPGEN2 with all sequencing bases (yellow) are compared to those from gnomAD (blue) for the cM block with the median number of base pairs. Ancestry-specific simulations are shown for African (n = 8,128; left) and non-Finnish European (n = 56,885; right), where the sample size observed in gnomAD v2.1 was matched. RAREsim emulates the expected number of variants within each MAC bin, whereas the other simulation methods either grossly underestimate (HAPGEN2 with polymorphic SNVs) or overestimate (HAPGEN2 with all sequencing bp) the number of variants.

COSI comparison

For the African sample (nAFR = 8,128), COSI with default parameters severely undersimulated the total number of rare variants (Figure S11), whereas the number of rare variants produced by COSI—matched Nvariants and RAREsim was more similar, although still slightly below, that observed in gnomAD. Compared to the gnomAD target data, both implementations of COSI underestimated the proportion of singletons and doubletons and consequently slightly overestimated the proportion of variants in higher MAC bins.

For the non-Finnish European sample (nNFE = 56,885), COSI under default parameters severely oversimulated the total number of rare variants. As opposed to what was seen for the smaller-sample-sized African simulations, both implementations of COSI oversimulated the proportion of singletons and undersimulated the proportion of variants with MACs ≥ 3. For both ancestries, RAREsim more closely matched the gnomAD target data, with respect to both the number of rare variants and AFS. It is worth noting that COSI’s mismatch of AFS was much less severe than what was observed with HAPGEN2. Because COSI did not match the target gnomAD data well for either ancestry and sample-size combination assessed here, additional evaluation and calibration of simulation parameters would be needed if COSI were to be used for matching target data such as that in gnomAD.

Correlation of simulated individuals

Within each of the four ancestral populations, pairwise IBS was calculated for ten RAREsim replicates. On average over the ten replicates, we found the distribution of pairwise IBS estimates to be slightly smaller than found in the original 1000 Genomes data (Table S9). This suggests that the simulated data are not more correlated than the subjects in the original 1000 Genomes data.

As a result of the relatively small number of variants (n = 179.48 on average) used in the IBS calculation, the IBS statistics are only a metric useful for comparing the simulated data to the real data, not for estimating relatedness. We found that a small number of pairs of individuals within the simulation had identical genotypes (IBS = 1) for the cM block examined here. The small number of variants (n ≤ 256) also makes it likely that some individuals have matching genotypes by chance rather than as a result of relatedness. Within the East Asian data, 16 identical pairs were observed in real data, whereas the RAREsim East Asian replicates had an average of 14.9 identical pairs (6–23 of 126,756 total pairs observed across the 10 replicates). Of the ten African RAREsim replicates, there were no identical pairs within the samples. Six RAREsim non-Finnish European RAREsim replicates had at least one identical pair (five replicates with a single pair; one replicate with two pairs; 81,406 total pairs), and all ten South Asian replicates had at least one identical pair (seven replicates had a single pair; two replicates had two pairs; one replicate had three pairs; 119,316 total pairs). If identical genetic information within the simulated genetic region is a concern, users can remove one individual from the identical pair after simulation.

Ancestry-specific linkage disequilibrium

As expected, LD patterns differed by ancestry. African ancestry and non-Finnish European ancestry had the smallest and largest pairwise r2, respectively (Figure S12). Ancestry-specific LD patterns were maintained in RAREsim’s simulation process; there were only small differences between the pairwise r2 for the 1000 Genomes data and the respective ancestry simulated by RAREsim (90% of pairwise r2 values were below 0.01988, 0.03859, 0.04372, and 0.03209 for African, East Asian, European, and South Asian ancestries, respectively; Figure S12). Some differences in in pairwise r2 between the real and simulated data are expected because of variability between simulation replicates. Indeed, no differences in LD between the real and simulated data would indicate that no randomness was introduced by the simulation process, defeating the primary purpose of simulations.

For rare and low-frequency variants (MAC = 5 − MAF 1%), LD patterns were similar between the original 1000 Genomes data and the RAREsim replicates for both r2 and D′ (Table S10). The average D′ for the ten RAREsim replicates and proportion of D′ = 1 differed by no more than 0.009 across the four ancestries. The average r2 was consistently, but slightly, higher (i.e., < 0.01) for RAREsim compared to 1000 Genomes in all four ancestries. Similarly, the average proportion of r2 = 1 for the ten RAREsim replicates was slightly higher than 1000 Genomes for all four ancestries. The range of the proportion of variant pairs with r2 = 1 across the ten RAREsim replicates contained the 1000 Genomes value for three of the four ancestries. For the South Asian ancestry, the minimum proportion of r2 = 1 across the ten replicates was 0.0545, whereas 0.0370 was observed within 1000 Genomes.

Generalizability of default parameters

Ancestry- and sample-size-specific default parameters for the “number of variants” and AFS functions (Table 1) were estimated from the median observation over cM blocks for each ancestry-and-sample-size group. RAREsim default parameters performed well and were able to match the observed number of variants and AFS in a wide variety of situations, including three GENCODE regions on chromosomes 1, 6, and 9,19 in non-coding regions within blocks, as well as in other datasets and sample sizes: gnomAD v3 and UK Biobank22 (Figure 4, Figures S13–S18). The simulated sample sizes evaluated were up to ∼3× larger (gnomAD v3 African) and ∼2× smaller (gnomAD v3 non-Finnish European) than the sample sizes used for deriving the default parameters. The default parameters often performed similarly to the cM-block-specific simulation parameters and always outperformed HAPGEN2.

Table 1.

Default estimates of function parameters

|

Number of variants |

Allele frequency spectrum |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African | 0.1576 | 0.6247 | 1.5883 | −0.3083 | 0.2872 |

| East Asian | 0.1191 | 0.6369 | 1.6656 | −0.2951 | 0.3137 |

| Non-Finnish European | 0.1073 | 0.6539 | 1.9470 | 0.1180 | 0.6676 |

| South Asian | 0.1249 | 0.6495 | 1.6977 | −0.2273 | 0.3564 |

Figure 4.

Generalizability of default parameters

Utility of RAREsim’s ancestry-specific default parameters for different chromosomes (A), sample sizes (B and C), intergenic regions (B), and other target datasets (B and C). RAREsim simulations closely approximate the observed number of variants (y axis) in each MAC bin (x axis) in all scenarios.

(A) Simulations using South Asian default parameters for chromosome 6 GENCODE region.

(B) Simulation of a sample size of 21,042 with African-ancestry default parameters (derived from n = 8,128) for an intergenic region from gnomAD v3.

(C) Simulation of a sample size of 41,246 to match a British sample from the UK Biobank under non-Finnish European default parameters (derived from n = 56,885).

Stratified simulation of functional and synonymous variants

As expected, we observed more functional than synonymous SNVs;2 the largest differences were observed at MAC (Figure S19). This resulted in substantially different fitted “number of variants” functions for the two types of variants (Figure S20). Stratified simulation of functional and synonymous variants closely approximated the number of variants observed in each MAC bin and suggests utility in separately simulating different groups of variants (Figure S21). We also found that performing simulations with non-stratified, region-specific parameters emulated the observed data for each class (Figure S22). Indeed, the functional/synonymous stratification performed well, but not substantially better than the non-stratified parameters. This is most likely because the 1000 Genomes reference data are representative of the proportion of each variant class.

Simulation of large sample sizes

As discussed previously (see “generalizability of default parameters”), RAREsim accurately simulated 21,042 African samples to match gnomAD v3 under ancestry-specific default parameters derived from African gnomAD v2.1 (n = 8,128). We currently assume that the AFS does not change with sample size. A consistent shape of AFS was observed over the gnomAD v2.1 ancestry-and-sample-size groups . Furthermore, ancestry-specific fitted “number of variants” functions that were extrapolated to larger sample sizes than those observed were similar to the shape of the fitted “number of variants” function for the total gnomAD v2.1 sample (n = 125,748) (Figure S23). Therefore, we believe simulating sample sizes up to ∼125,000 is probably reasonable.

Computation time

The time it took to simulate one replicate on a desktop with 32 GB RAM for a cM block on chromosome 19 varied between 8 s for the smallest block (3,183 bp) and sample size (nAfrican = 8,128) and 11 h 18 min, 21 s for the largest block (81,235 bp) and sample size (nnon-Finnish European = 56,5885). The median run time was 1 min, 19 s (Table S11).

The amount of time it took to simulate haplotypes with RAREsim was dependent on the number of samples being simulated and the size of the region. Simulating a region with ∼19 Kb varied between 49 s for n = 8,128 and 15 min 53 s for n = 56,885. When simulating n = 15,308 individuals, RAREsim simulations took between 8 s for a region of ∼3 Kb and 8 min 9 s for a region of ∼81 Kb. The rate-limiting step in large simulations was HAPGEN2. For the largest region and sample size, HAPGEN2 took more than 11 h to perform a simulation on a machine with 32 GB RAM. The same region was simulated in ∼1 h and 19 min when 192 GB RAM was used, indicating that memory capacity was reached under the original computing specs (see Methods).

Discussion

Here we present RAREsim, a rare-variant simulation algorithm. Unlike HAPGEN2, which either severely under- or over-simulates the proportion of very rare variants, RAREsim simulates the expected proportion of rare and very rare variants across a variety of genetic regions, ancestries, and sample sizes. RAREsim produces simulations that match the expected AFS, total number of variants, and haplotype structure while enabling variant annotation. Although coalescent simulation models can also match the expected proportion of rare variants, these models lose connection to variant-specific annotation in real data. With RAREsim, the sequencing bases in a genetic region of interest maintain their genetic meaning because RAREsim simulates from real data. To our knowledge, no other existing simulation software is able to emulate real data in all of these areas. We show that RAREsim’s ancestry-specific default parameters derived from the coding regions of chromosome 19 generalize to other chromosomes, datasets, sample sizes, and non-coding regions, approximating the number of variants per MAC bin with remarkable accuracy. We offer user flexibility by enabling use of RAREsim with default parameters, user-defined parameters, or parameters estimated to match user-provided target data.

For typical uses of simulated genetic data (i.e., evaluating or comparing methods and general power analysis), we recommend performing simulations with the default parameters. Default parameters were shown to be robust across sample sizes, chromosomes, coding and intergenic regions, and datasets. It is possible, although we believe unlikely, that the default parameters will perform poorly when used in scenarios not evaluated here. If precise matching of a particular empirical data characteristic such as functional variant type, genetic region, sample size, or ancestry is important, we recommend re-estimating the simulation parameters by using RAREsim functions. Additionally, users can specify parameters without fitting target data. For example, to simulate a specific ancestry, a user could make an educated decision on the total number of variants on the basis of the relationship to the ancestries evaluated here (e.g., total number of variants between African and European ancestries).

RAREsim simulates haplotypes in the same form as HAPGEN2: hap/leg/sample files.[14] Haplotype files can be converted to vcf files with the SHAPEIT “convert” command26 or bcftools “haplegendsample2vcf” command.27 Genetic association with disease can be simulated from a sample of generated haplotypes with an existing software such as PhenotypeSimulator.28 Simulation of families or large pedigrees can be performed with a pedigree simulation software such as ped-sim.29

Users can complete simulations by stratifying over non-overlapping classes of variants, as demonstrated with the functional/synonymous stratification. Users may annotate and stratify by using any exhaustive, mutually exclusive annotation, provided that HAPGEN2 with all sequencing bases over-simulates each class to allow for pruning. A lack of over-simulation was not observed in any of our regions or scenarios. Stratified RAREsim could be especially useful in regions where the distribution of rare variants is expected or observed to differ greatly between annotation classes. To complete stratified simulations by variant class, RAREsim requires stratified target data. Users can obtain the AFS target data simply by annotating summary-level target data by variant class; the “number of variants” target data must be estimated from individual-level data by down-sampling the number of individuals in the sample. For the functional and synonymous stratification exemplar presented here, we used the down-sampled data from gnomAD, which has number of variants by functional and synonymous class.

There is increasing interest in WGS and studies of non-coding regions. Here, we show that the default parameters for RAREsim work well in exemplar non-coding regions. Additionally, one can include any empirical annotation in non-coding regions either by stratifying the simulation pipeline by annotation class similar to our example with functional and synonymous variants or by simulating as usual and adding annotation onto the simulated data.

It has been shown that sample sizes in the tens to hundreds of thousands are needed to provide sufficient power to detect associations with rare variants.30 Because of the lack of very large (>100,000), ancestry-specific, publicly available target data at the time of publication, we could not assess the accuracy of the RAREsim simulations for very large sample sizes. As genetic sequencing resources continue to increase in size, RAREsim will be ideally suited to simulate large sample sizes with estimation of new simulation parameters. For the “number of variants” function, the extrapolated, ancestry-specific “number of variants” functions were compared with that of the full sample available in gnomAD v2.1. We believe that the “number of variants” function is able to accurately simulate sample sizes up to what is observed in gnomAD v2.1 (∼125,000). Alternatively, users can use population-genetics theory or other resources to make an informed decision about the total number of variants expected for very large samples. One such resource is the Capture-Recapture31 algorithm, which can be used for estimating the number of segregating sites given allele-count data. Athough Capture-Recapture can extrapolate to larger sample sizes, the software cannot be easily used for sample sizes that are smaller than the observed target data. RAREsim does not currently modify the AFS function as sample size increases. Consistent AFS were observed over the gnomAD sample sizes (n = 8,128–56,88). However, we expect the AFS to deviate with very large sample sizes. A user can update the AFS function parameters if desired, and research into estimating the expected AFS for very large sample sizes is ongoing. We believe that RAREsim can currently accurately simulate sample sizes up to ∼125,000.

Even as large, publicly available haplotype samples (e.g., UK Biobank) become available, RAREsim and other simulation methods will continue to be important. While these large samples can be used as reference haplotypes for RAREsim, simply resampling would result in less variability between replicates15 and no novel rare variants. Additionally, RAREsim allows for simulation of diverse ancestral groups, which are not yet available as large haplotype pools.

There are several limitations to RAREsim. First, RAREsim is only as good as the data on which the simulations are based. Errors or inconsistencies in the target data or input simulation haplotypes will be propagated through the simulations. Second, the default parameters were developed and evaluated on autosomes. A user can fit sex-chromosome target data or assume parameters extend to sex chromosomes. Finally, RAREsim requires additional memory (e.g., > 32 GB RAM) for simulations of large regions and sample sizes. For efficient simulation of large regions and sample sizes, highmem computing or breaking up the simulation region into smaller portions and combining after simulation is needed. We are actively working on extensions for these limitations.

One of the primary benefits of RAREsim is its ability to match real target data, either provided by the user or as done here with gnomAD v2.1. Matching observed data allows RAREsim to adapt as sequencing data evolves as a result of technological advances or improved genetic resources from additional ancestral populations and increased sample sizes. For example, RAREsim will be able to approximate TopMED32 and ALFA, aggregated allele frequencies from dbGaP33 once these resources are released. RAREsim can also simulate unique characteristics of a specific genetic region such as haploinsufficiency, contribution to a polygenic risk score, or selection. The flexibility of RAREsim to emulate real data allows users to assess methods and complete power analyses for relevant and realistic genetic regions and samples.

Acknowledgments

The UK Biobank data was gathered with the UK Biobank resource under application number 42614. We would like to thank Achilleas Pitsillides for obtaining the UK Biobank allele counts. We would also like to thank Robert Goedman for providing programming insight. We thank Ferdinand Baer for support of this project. This work was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (R35HG011293 and U01HG009080 to A.E.H. and C.G.R.; U01HG009080-05S1 to C.G.R.).

Declaration of interests

C.R.G. owns stock in 23andMe.

Published: March 16, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.02.009.

Data and code availability

The reference haplotype and legend files including all monomorphic sequencing bases within the coding regions are available at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. Target data for each block is included in the ‘Stratified_Target_Data’ folder and are annotated with functional and synonymous variant annotation to allow users to estimate stratified parameters. RAREsim is an open-source R package, and all code can be found at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim. A small example simulation with the necessary script is available at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. Code to complete the majority of the analyses included here can also found at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. Already-simulated rare-variant data can also be found at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. For each of the four ancestral populations, 1,000 replicates of the block with the median number of bp (19,029 bp) was simulated for twice the sample size observed in gnomAD: African: n = 16,256; East Asian: n = 18,394; non-Finnish European: n = 113,770; South Asian: n = 30,616.

Web resources

All data used in this research are publicly available with links found in Table S1.

RARESim example, https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Povysil G., Petrovski S., Hostyk J., Aggarwal V., Allen A.S., Goldstein D.B. Rare-variant collapsing analyses for complex traits: guidelines and applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:747–759. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., Cummings B.B., Alföldi J., Wang Q., Collins R.L., Laricchia K.M., Ganna A., Birnbaum D.P., et al. Genome Aggregation Database Consortium The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auton A., Brooks L.D., Durbin R.M., Garrison E.P., Kang H.M., Korbel J.O., Marchini J.L., McCarthy S., McVean G.A., Abecasis G.R., 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter K., Min J.L., Huang J., Crooks L., Memari Y., McCarthy S., Perry J.R., Xu C., Futema M., Lawson D., et al. UK10K Consortium The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease. Nature. 2015;526:82–90. doi: 10.1038/nature14962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbitoff Y.A., Skitchenko R.K., Poleshchuk O.I., Shikov A.E., Serebryakova E.A., Nasykhova Y.A., Polev D.E., Shuvalova A.R., Shcherbakova I.V., Fedyakov M.A., et al. Whole-exome sequencing provides insights into monogenic disease prevalence in Northwest Russia. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2019;7:e964. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coventry A., Bull-Otterson L.M., Liu X., Clark A.G., Maxwell T.J., Crosby J., Hixson J.E., Rea T.J., Muzny D.M., Lewis L.R., et al. Deep resequencing reveals excess rare recent variants consistent with explosive population growth. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:131. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madsen B.E., Browning S.R. A groupwise association test for rare mutations using a weighted sum statistic. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendricks A.E., Bochukova E.G., Marenne G., Keogh J.M., Atanassova N., Bounds R., Wheeler E., Mistry V., Henning E., Körner A., et al. Understanding Society Scientific Group. EPIC-CVD Consortium. UK10K Consortium Rare Variant Analysis of Human and Rodent Obesity Genes in Individuals with Severe Childhood Obesity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4394. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03054-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X., Li Z., Zhou H., Gaynor S.M., Liu Y., Chen H., Sun R., Dey R., Arnett D.K., Aslibekyan S., et al. NHLBI Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Consortium. TOPMed Lipids Working Group Dynamic incorporation of multiple in silico functional annotations empowers rare variant association analysis of large whole-genome sequencing studies at scale. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:969–983. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0676-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher R.A. On the dominance ratio. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. 1923;42:321–341. doi: 10.1007/BF02459576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright S. Evolution in Mendelian Populations. Genetics. 1931;16:97–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/16.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingman J. On the genealogy of large populations. J. Appl. Probab. 1982;19:27–43. doi: 10.2307/3213548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li N., Stephens M. Modeling linkage disequilibrium and identifying recombination hotspots using single-nucleotide polymorphism data. Genetics. 2003;165:2213–2233. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su Z., Marchini J., Donnelly P. HAPGEN2: simulation of multiple disease SNPs. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2304–2305. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendricks A.E., Dupuis J., Gupta M., Logue M.W., Lunetta K.L. A comparison of gene region simulation methods. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moutsianas L., Agarwala V., Fuchsberger C., Flannick J., Rivas M.A., Gaulton K.J., Albers P.K., McVean G., Boehnke M., Altshuler D., McCarthy M.I., GoT2D Consortium The power of gene-based rare variant methods to detect disease-associated variation and test hypotheses about complex disease. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, S.G. The NLopt nonlinear-optimization package, http://ab-initio.mit.edu/nlopt.

- 18.Fu Y.X. Statistical properties of segregating sites. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1995;48:172–197. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.1995.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankish A., Diekhans M., Ferreira A.M., Johnson R., Jungreis I., Loveland J., Mudge J.M., Sisu C., Wright J., Armstrong J., et al. GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D766–D773. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaffner S.F., Foo C., Gabriel S., Reich D., Daly M.J., Altshuler D. Calibrating a coalescent simulation of human genome sequence variation. Genome Res. 2005;15:1576–1583. doi: 10.1101/gr.3709305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Hout C.V., Tachmazidou I., Backman J.D., Hoffman J.D., Liu D., Pandey A.K., Gonzaga-Jauregui C., Khalid S., Ye B., Banerjee N., et al. Geisinger-Regeneron DiscovEHR Collaboration. Regeneron Genetics Center Exome sequencing and characterization of 49,960 individuals in the UK Biobank. Nature. 2020;586:749–756. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2853-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J., Raskin L., Samuels D.C., Shyr Y., Guo Y. Genome measures used for quality control are dependent on gene function and ancestry. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:318–323. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaren W., Gil L., Hunt S.E., Riat H.S., Ritchie G.R., Thormann A., Flicek P., Cunningham F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connell J., Sharp K., Shrine N., Wain L., Hall I., Tobin M., Zagury J.F., Delaneau O., Marchini J. Haplotype estimation for biobank-scale data sets. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:817–820. doi: 10.1038/ng.3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R., 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer H.V., Birney E. PhenotypeSimulator: A comprehensive framework for simulating multi-trait, multi-locus genotype to phenotype relationships. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2951–2956. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caballero M., Seidman D.N., Qiao Y., Sannerud J., Dyer T.D., Lehman D.M., Curran J.E., Duggirala R., Blangero J., Carmi S., Williams A.L. Crossover interference and sex-specific genetic maps shape identical by descent sharing in close relatives. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1007979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuk O., Schaffner S.F., Samocha K., Do R., Hechter E., Kathiresan S., Daly M.J., Neale B.M., Sunyaev S.R., Lander E.S. Searching for missing heritability: designing rare variant association studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E455–E464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322563111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gravel S., National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) GO Exome Sequencing Project Predicting discovery rates of genomic features. Genetics. 2014;197:601–610. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.162149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taliun D., Harris D.N., Kessler M.D., Carlson J., Szpiech Z.A., Torres R., Taliun S.A.G., Corvelo A., Gogarten S.M., Kang H.M., et al. NHLBI Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Consortium Sequencing of 53,831 diverse genomes from the NHLBI TOPMed Program. Nature. 2021;590:290–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phan L., Jin Y., Zhang H., Qiang W., Shekhtman E., Shao D., Revoe D., Villamarin R., Ivanchenko E., Kimura M., et al. 2020. ALFA: Allele Frequency Aggregator. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/docs/gsr/alfa/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The reference haplotype and legend files including all monomorphic sequencing bases within the coding regions are available at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. Target data for each block is included in the ‘Stratified_Target_Data’ folder and are annotated with functional and synonymous variant annotation to allow users to estimate stratified parameters. RAREsim is an open-source R package, and all code can be found at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim. A small example simulation with the necessary script is available at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. Code to complete the majority of the analyses included here can also found at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. Already-simulated rare-variant data can also be found at https://github.com/meganmichelle/RAREsim_Example. For each of the four ancestral populations, 1,000 replicates of the block with the median number of bp (19,029 bp) was simulated for twice the sample size observed in gnomAD: African: n = 16,256; East Asian: n = 18,394; non-Finnish European: n = 113,770; South Asian: n = 30,616.