Abstract

Background

Pretreatment invasive nodal staging is paramount for appropriate treatment decisions in non-small cell lung cancer. Despite guidelines recommending when to perform staging, many studies suggest that invasive nodal staging is underused. Attitudes and barriers to guideline-recommended staging are unclear. The National Lung Cancer Roundtable initiated this study to better understand the factors associated with guideline-adherent nodal staging.

Research Question

What are the knowledge gaps, attitudes, and beliefs of thoracic surgeons and pulmonologists about invasive nodal staging? What are the barriers to guideline-recommended staging?

Study Design and Methods

A web-based survey of a random sample of pulmonologists and thoracic surgeons identified as members of American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) was conducted in 2019. Survey domains included knowledge of invasive nodal staging guidelines, attitudes and beliefs toward implementation, and perceived barriers to guideline adherence.

Results

Among 453 responding physicians, 29% were unaware that invasive nodal staging guidelines exist. Among the 320 physicians who knew guidelines exist, attitudes toward the guidelines were favorable, with 91% agreeing guidelines are generalizable and 90% agreeing that recommendations improved their staging and treatment decisions. Approximately 80% responded that guideline recommendations are based on satisfactory levels of scientific evidence, and 50% stated a lack of evidence linking adherence to guidelines to changes in management or better patient outcomes. Nearly 9 in 10 physicians reported at least one barrier to guideline adherence. The most common barriers included patient anxiety associated with treatment delays (62%), difficulty implementing guidelines into routine practice (52%), and time delays of additional testing (51%).

Interpretation

Among physicians who responded to our survey, more than one-quarter were unaware of invasive nodal staging guidelines. Attitudes toward guideline recommendations were positive, although 20% reported insufficient evidence to support staging algorithms. Most physicians reported barriers to implementing guidelines. Multilevel interventions are likely needed to increase rates of guideline-recommended invasive nodal staging.

Key Words: invasive nodal staging, lung cancer guidelines

Graphical Abstract

Take-home Points.

Research Question: What are the knowledge gaps, attitudes, and beliefs of thoracic surgeons and pulmonologists about invasive nodal staging? What are the barriers to guideline-recommended staging?

Results: More than one-quarter of thoracic surgeons and pulmonologists were unaware that invasive nodal staging guidelines exist. Among those aware of the guidelines, most agreed that guidelines were favorable and generalizable and that the recommendations improved their staging and treatment decisions, with only 20% responding that staging guidelines are not based on satisfactory levels of scientific evidence. Barriers to guideline adherence were reported commonly and included patient anxiety associated with treatment delays, difficulty implementing guidelines into routine practice, and time delays of additional testing.

Interpretation: Most physicians who reported being aware of guidelines have positive attitudes toward invasive nodal staging, but most face barriers to guideline implementation. Multilevel interventions are needed to improve knowledge and dissemination and to increase rates of guideline-recommended invasive nodal staging in non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung cancer staging is critically important for appropriate treatment selection, which is a key determinant of patient outcomes. Historically, invasive staging of mediastinal nodes has been the focus of intrathoracic staging in lung cancer. However, in the era of stereotactic body radiotherapy as an alternative treatment for patients with inoperable stage I non-small cell lung cancer, staging the hilar nodes when indicated by endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration is important before treatment. Herein, we refer to pretreatment intrathoracic staging, including hilar and mediastinal nodes, as invasive nodal staging. Several professional organizations have published largely congruent practice recommendations to guide optimal invasive nodal staging based on the best available evidence.1,2 However, treating physicians tend to underuse invasive nodal staging.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Moreover, evidence of substantial and inexplicable variation in invasive nodal staging in lung cancer exists across patients and centers.11, 12, 13, 14 Furthermore, when staging is performed, the quality of staging often fails to meet expectations.15 For instance, a significant proportion of patients undergoing invasive nodal staging have inadequate tissue samples sent for pathologic examination, the diagnostic yield is low, or both.3,10,13,16 Collectively, these observations indicate a gap in the quality of lung cancer care in the United States.

We surveyed pulmonologists and thoracic surgeons to understand the reasons underlying discordant and variable invasive nodal staging in lung cancer within the United States. Specifically, we sought (1) to determine physician knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about invasive nodal staging practice guidelines and the level of evidence base supporting the recommendations; and (2) to evaluate perceived barriers to adherence with guideline-recommended invasive nodal staging.

Study Design and Methods

Survey Development

We based our survey questions on those used in a mixed-methods study that aimed to understand the reasons underlying guideline-discordant and variable treatment of locally advanced lung cancer among patients residing within Ontario, Canada.17 Key informant interviews from that investigation revealed that patient, family, physician, and clinical team factors, as well as scientific evidence, were important themes that emerged when providers considered determinants of treatment decision-making. Accordingly, we used these themes to develop additional items in our barrier analysis.

In the fall of 2018 and early 2019, we developed our survey in collaboration with a subgroup of the National Lung Cancer Roundtable Triage for Appropriate Treatment Task Group, comprising two pulmonologists specializing in lung cancer, two thoracic surgeons, one radiologist, two radiation oncologists, and one epidemiologist. The National Lung Cancer Roundtable Triage for Appropriate Treatment Task Group provided feedback and guidance on the survey question content and formatting. The 44-item survey included the following domains: respondent demographics; guideline knowledge; beliefs, attitudes, and institutional practices about guideline recommendations; and barriers to adherence to invasive nodal staging guideline recommendations. Survey questions comprised Likert scale, multiple-choice, and short-answer items.

The survey was pilot tested with eight pulmonary fellows and one thoracic surgery fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina before going live. Pilot test respondents were provided with a link to the test survey and were asked to take notes about the content as they completed the survey. Specifically, they were asked to focus on language that was not clear and response sets that did not reflect their range of possible answers to the question. At the end of the survey, respondents were asked to provide their notes regarding content issues. The pilot test respondents raised no major structural issues, but several minor language edits were suggested to improve question clarity. These comments were reviewed with the clinical advisory team on this project, and several language edits were made to the final survey script (e-Appendix 1) before launch.

Survey Deployment

The survey was deployed to pulmonologists and thoracic surgeons identified from the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Analytics database in April and May 2019. The CHEST Analytics database comprises 25,237 clinicians in the United States. Of the 14,208 pulmonologists in the database, we randomly sampled 7,238 pulmonologists (regardless of clinical interests) and all (1,067) thoracic surgeons, with a total of 8,305 individuals receiving the survey. To be included, respondents were required to self-report that (1) they see patients for at least one half-day per week and (2) they diagnose at least one new case of lung cancer per month, on average. Respondents who did not meet these requirements were excluded from participation (n = 49 pulmonologists and n = 4 thoracic surgeons), leaving 8,252 as the denominator.

Each respondent was contacted up to three times by e-mail to maximize the survey response rate. The initial contact was by e-mail in April 2019 with an introduction letter to the survey and a survey link. Each targeted respondent received the initial survey invitation, a second e-mail reminder 5 to 7 days after the initial request, and a third e-mail reminder 2 to 3 days after the second e-mail, unless they already had responded to the survey. An incentive of $50 in the form of an electronic gift card was offered to respondents who completed the survey. This study was designated as exempt by the institutional review board at Medical University of South Carolina.

Statistical Analyses

We determined the proportion of physicians who were aware of invasive nodal staging guidelines and compared knowledge by physician specialty, practice setting, and volume of new lung cancer cases diagnosed per month using χ2 tests. Among those who were aware of guidelines, we assessed attitudes and barriers toward adherence to guideline recommendations. For the attitude toward invasive nodal staging questions, we combined responses of strongly agree and agree into one category of agree and responses of disagree and strongly disagree into one category of disagree. For the barriers to invasive nodal staging questions, we combined responses of never and almost never into responses of no and responses of sometimes, almost always, and always into responses of yes.

Results

Guideline Knowledge

The response rate was 5.5% (453/8,252). Of the 453 respondents, 29% (n = 133) reported being unaware of the existence of invasive nodal staging guidelines (Table 1). Knowledge of guidelines was lower among general pulmonologists compared with interventional pulmonologists and thoracic surgeons (65% vs 85% and 82%, respectively; P = .0004). Physicians in academic settings were more likely to report knowing guidelines exist than those in community settings (76% vs 67.5%; P = .0457). Because of the small number of responders in subgroups, we did not evaluate differences by physician specialty or setting type further.

Table 1.

Knowledge of Mediastinal Staging Guidelines by Specialty, Practice Setting, and Case Volume

| Characteristic | Alla | Do Guidelines Exist? |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nob | Yesb | P Value | ||

| All respondents | 453 (100) | 133 (29.4) | 320 (70.6) | N/A |

| Specialty | ||||

| General pulmonologist | 327 (72.2) | 113 (34.6) | 214 (65.4) | .0004 |

| Interventional pulmonologist | 82 (18.1) | 12 (14.6) | 70 (85.4) | ... |

| Thoracic surgeon | 44 (9.7) | 8 (18.2) | 36 (81.8) | ... |

| Practice setting | ||||

| Academic medical center | 161 (35.5) | 38 (23.6) | 123 (76.4) | .0457 |

| Community based | 292 (64.5) | 95 (32.5) | 197 (67.5) | ... |

| Average no. of new lung cancer cases diagnosed/mo | ||||

| 1-4 | 211 (46.6) | 66 (31.3) | 145 (68.7) | .1732 |

| 5-9 | 135 (29.8) | 44 (32.6) | 91 (67.4) | ... |

| 10-14 | 65 (14.3) | 12 (18.5) | 53 (81.5) | ... |

| 15+ | 42 (9.3) | 11 (26.2) | 31 (73.8) | ... |

Data are presented as No. (%), unless otherwise indicated. N/A = not applicable.

Column percentages.

Row percentages.

Beliefs, Attitudes, and Institutional Practices

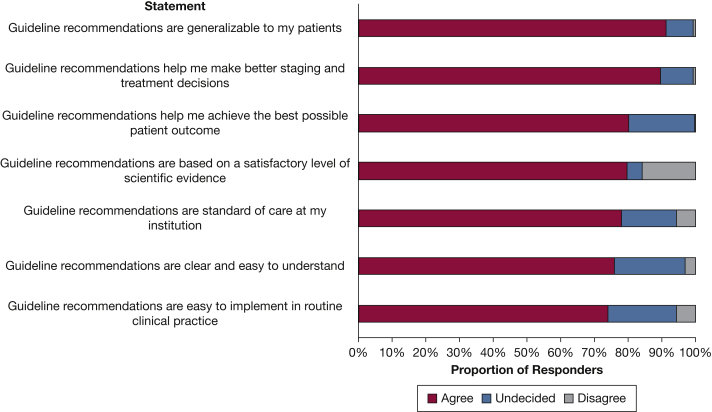

Physicians who were aware of guidelines (n = 320) were asked to indicate their level of agreement with seven statements about guideline recommendations for invasive mediastinal staging (Fig 1). Ninety-one percent agreed that recommendations are generalizable to their patients and 90% agreed that guidelines help them to make better staging and treatment decisions. Although the large majority (80%) of physicians agreed that guidelines help them to achieve the best possible patient outcome, 20% were undecided. Twenty percent of respondents believed that guideline recommendations were not based on a satisfactory level of evidence. Approximately three-quarters of physicians agreed with the statements that recommendations (1) are a standard of care in their institutions, (2) are clear and easy to understand, and (3) are easy to implement in routine clinical practice.

Figure 1.

Bar graph showing attitudes toward invasive mediastinal staging guidelines among 320 physicians who indicated that guidelines exist.

Perceived Barriers to Guideline-Concordant Mediastinal Staging

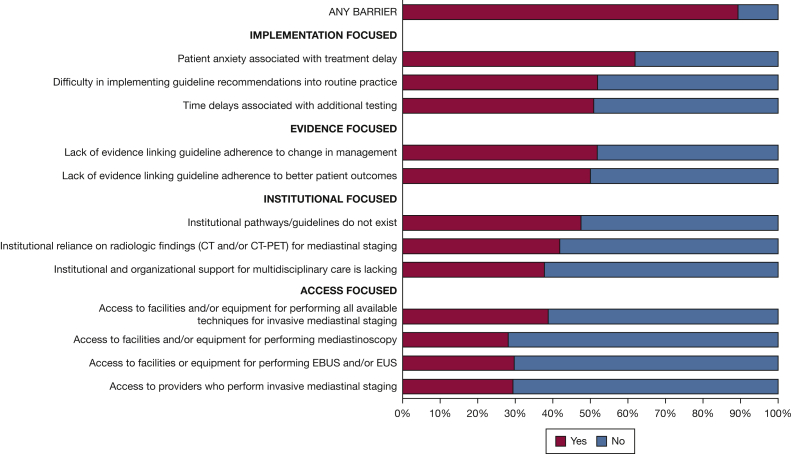

When respondents were asked to indicate how often they perceived a list of 12 items to be a barrier to adherence to invasive mediastinal staging guideline recommendations, 89% reported at least one barrier (Fig 2). The most commonly reported barriers were focused on guideline implementation and the evidence base. In terms of implementation, 62% reported patient anxiety associated with treatment delay. About half of respondents reported difficulty implementing guideline recommendations into routine practice or time delays associated with additional testing and a lack of evidence linking guideline adherence to both changes in management and better patient outcomes. Institutional barriers included 47% reporting that pathways or guidelines do not exist, 42% reporting reliance on radiologic findings for staging, and 38% reporting that institutional and organizational support for multidisciplinary care is lacking. Access to facilities and specialists who perform mediastinal staging also was noted as a barrier by 28% to 39% of physicians, respectively.

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing reported barriers to adherence to invasive mediastinal staging guideline recommendations among 320 physicians who indicated that guidelines exist. EBUS = endobronchial ultrasound; EUS = endoscopic ultrasound.

Discussion

Although guidelines are developed to help standardize clinical practice,18 the fact that more than one-quarter of respondents are not aware of the existence of invasive nodal staging guidelines is greatly concerning and likely is a significant factor in the lack of guideline-adherent care. However, a certain amount of variation in the delivery of guideline-recommended care is expected in patients with the same disease characteristics because of differences in health-care settings, available resources, patient characteristics, and clinician preferences.19 Nonetheless, variation in the practice of invasive nodal staging is significant, and evidence shows that a substantial number of patients with non-small cell lung cancer do not receive guideline-appropriate staging.4,5,7,8 What accounts for the variability in invasive nodal staging is uncertain,20 but likely multifactorial, including gaps in knowledge of existing guidelines (as noted previously), distrust in existing recommendations resulting from low levels of evidence supporting a link between guideline adherence and better patient outcomes, interest in higher-value staging practices,21 relying on local practice traditions and routines, patient preferences, and lack of access to facilities and specialty care.

US studies showed up to 25-fold center-level variation not explained by case mix, access to specialists, or chance.13,14 Additionally, a similar degree of center-level variability was noted in populations cared for by community and specialty clinicians. Lack of adherence to guidelines is not unique to the United States. A study of mediastinal staging by thoracic surgeons in Canada found significant variation in staging practices, with deviations from guidelines.22

Our results indicate that physicians, in general, have positive attitudes toward invasive nodal staging, with about 90% agreeing that guidelines help to make better decisions. Interestingly, about 20% of physicians reported that the guidelines are not based on a satisfactory level of scientific evidence. This is understandable; as is generally true for diagnostic tests, the supporting evidence for invasive nodal staging is based on evidence of disease incidence (eg, N2, N3 node involvement) and test performance characteristics (eg, sensitivity, specificity), rather than level I evidence demonstrating an effect of test use on patient outcomes (eg, survival).

In this study, we sought to understand better the barriers that impact delivery of guideline-recommended invasive nodal staging to be able to develop interventions to address the barriers. We found that limited physician knowledge, limited access to facilities and specialists, and belief that evidence was limited for guideline recommendations—but not physician attitudes—are barriers to guideline-concordant invasive nodal staging. A study investigating clinical variation across guideline-based care identified physician overreliance on subjective judgment and patient preferences as factors in lack of adherence to guidelines.23 In the context of invasive staging, we found that patient anxiety (ie, preferences) over delays in initiation of treatment was a barrier to guideline-recommended invasive nodal staging. Additional barriers to guideline adherence include institutional or organizational constraints, lack of knowledge regarding guideline recommendations, and factors such as unclear or ambiguous guideline recommendations.24 In this study, gaps in the knowledge of existing guidelines and lack of access to facilities and specialists were the more notable barriers to guideline-concordant invasive nodal staging. In this survey, barriers seem to be related to access in terms of both physicians performing staging procedures and facilities that provide the procedures. However, in population-based studies, center-level variability in invasive nodal staging seems to be unrelated to the community vs specialty setting13,14 or general vs thoracic surgeons.12 Potential explanations for these discordant findings are: (1) our sample of physicians may not be generalizable; (2) barriers to guideline-recommended staging may be different at the clinician vs center level; or (3) both.

Strengths of our study include the national sample of 453 physicians covering several subspecialties and in-depth questions on attitudes and barriers. Limitations of our study include the low response rate and the small sample size, which did not permit comparisons between specialty physicians and setting types. Future research should evaluate the type of physicians who are not following guidelines for invasive mediastinal node staging so that factors associated with nonadherence to guideline recommendations can be addressed. We were also limited in our ability to assess nonresponse bias because we do not have information on the nonrespondents that would allow for computation of sampling weights. Finally, the low response rate among the membership of CHEST raises the possibility that the respondents were a highly select group of physicians with an interest in invasive mediastinal staging. If true, then the generalizability of the responses may be limited.

Interpretation

Of physicians who reported being aware of guidelines, most have positive attitudes toward invasive nodal staging, but most face barriers to guideline implementation. More than one-quarter of physicians who report that on average they diagnose at least one new case of lung cancer per month were unaware of invasive nodal staging guidelines. Efforts to improve dissemination of available staging guidelines and to improve knowledge are needed, as well as multilevel interventions designed to topple barriers to guideline-recommended care, including generation of higher levels of scientific evidence to support recommendations.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: L. M. H., F. F., F. D., R. A. S., G. A. S., and M. P. R. contributed to the conception and design of the survey and the study. L. M. H., F. F., F. D., R. A. S., G. A. S., and M. P. R. guarantee the content of the manuscript. R. A. S. and G. A. S. contributed to the acquisition of the data. L. M. H. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data. L. M. H. contributed substantially to statistical analysis. L. M. H., F. F., and M. P. R. contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. L. M. H., F. F., F. D., R. A. S., G. A. S., and M. P. R. contributed to revisions of the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. All of the authors approved this version of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: M. P. R. in 2019 served on the advisory boards of Biodesix, bioaAffinity Technologies, and Johnson & Johnson. R. A. S. is employed by the American Cancer Society, which receives unrestricted educational grants from private companies and corporate foundations to support the National Lung Cancer Roundtable. His salary is funded solely through American Cancer Society funds. None declared (L. M. H., F. F., F. D., G. A. S.).

Additional information: The e-Appendix can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was funded the American Cancer Society National Lung Cancer Roundtable. L. M. H. receives funding from the National Institutes of Health. F. F. receives funding from PCORI and the National Institutes of Health. M. P. R. receives funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Silvestri G.A., Gonzalez A.V., Jantz M.A., et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 suppl):e211S–e250S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettinger D.S., Wood D.E., Aggarwal C., et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 1.2020: NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1464–1472. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little A.G., Rusch V.W., Bonner J.A., et al. Patterns of surgical care of lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(6):2051–2056. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.071. discussion 2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little A.G., Gay E.G., Gaspar L.E., Stewart A.K. National survey of non-small cell lung cancer in the United States: epidemiology, pathology and patterns of care. Lung Cancer. 2007;57(3):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farjah F., Flum D.R., Ramsey S.D., et al. Multi-modality mediastinal staging for lung cancer among Medicare beneficiaries. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(3):355–363. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318197f4d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinan M.A., Curtis L.H., Carpenter W.R., et al. M. Stage migration, selection bias, and survival associated with the adoption of positron emission tomography among Medicare beneficiaries with non-small-cell lung cancer, 1998-2003. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(22):2725–2730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ost D.E., Niu J., Elting L.S., Buchholz T.A., Giordano S.H. Determinants of practice patterns and quality gaps in lung cancer staging and diagnosis. Chest. 2014;145(5):1097–1113. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ost D.E., Niu J., Elting L.S., Buchholz T.A., Giordano S.H. Quality gaps and comparative effectiveness in lung cancer staging and diagnosis. Chest. 2014;145(2):331–345. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flanagan M.R., Varghese T.K., Backhus L.M., et al. Gaps in guideline concordant use of diagnostic tests among lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(6):2006–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osarogiabon R.U., Lee Y.S., Faris N.R., et al. Invasive mediastinal staging for resected non-small cell lung cancer in a population-based cohort. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158(4):1220–1229.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.04.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lathan C.S., Neville B.A., Earle C.C. The effect of race on invasive staging and surgery in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):413–418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farjah F., Flum D.R., Varghese T.K., Jr., et al. Surgeon specialty and long-term survival after pulmonary resection for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(4):995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornblade L.W., Wood D.E., Mulligan M.S., et al. Variability in invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer: a multi-center regional study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(6):2658–2671. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.12.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krantz S.B., Howington J.A., Wood D.E., et al. Invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer by Society of Thoracic Surgeons database participants. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106(4):1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navani N., Fisher D.J., Tierney J.F., et al. NSCLC Meta-analysis Collaborative Group. The accuracy of clinical staging of stage I-IIIa non-small cell lung cancer. An analysis based on individual participant data. Chest. 2019;155(3):502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ost D.E., Ernst A., Lei X., et al. Diagnostic yield of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: results of the AQuIRE Bronchoscopy Registry. Chest. 2011;140(6):1557–1566. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouwers M.C., Makarski J., Garcia K., et al. A mixed methods approach to understand variation in lung cancer practice and the role of guidelines. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jazieh A., Alkaiyat M.O., Ali Y., et al. Improving adherence to lung cancer guidelines: a quality improvement project that uses chart review, audit and feedback approach. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birkmeyer J.D., Reames B.N., McCulloch P., et al. Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. Lancet. 2013;28;382(9898):1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61215-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farjah F., Silvestri G.A., Wood D.E. Commentary: invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer—quality gap, evidence gap, both? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158(4):1232–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verdial F.C., Madtes D.K., Hwang B., et al. Prediction model for nodal disease among patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(6):1600–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner S.R., Seyednejad N., Nasir B.S. Patterns of practice in mediastinal lymph node staging for non-small cell lung cancer in Canada. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106(2):428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James B. Quality improvement opportunities in health care. Making it easy to do it right. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8:394–399. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2002.8.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lugtenberg M., Zegers-van Schaick J.M., Westert G.P., et al. Why don’t physicians adhere to guideline recommendations in practice? An analysis of barriers among Dutch general practitioners. Implementation Sci. 2009;4:54. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.