Abstract

The expression of the ubiquitin (Ub) gene in dermatophytes was examined for its relation to resistance against the antifungal drug fluconazole. The nucleotide sequences and the deduced amino acid sequences of the Ub gene in Microsporum canis were proven to be 99% similar to those of the Ub gene in Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Expression of mRNA of Ub in M. canis and T. mentagrophytes was enhanced when the fungi were cultured with fluconazole. The antifungal activity of fluconazole against these dermatophytes was increased in the presence of Ub proteasome inhibitor.

Selective protein degradation in eukaryotic cells is mainly carried out by the ubiquitin (Ub) system (7, 17, 18). Ub is a highly conserved 76-residue protein which is distributed in eukaryotic cells and linked to a vast range of proteins (19). The Ub system plays important roles in many cellular functions, including cell cycle control, signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, the nuclear transport process, receptor control by endocytosis, etc. (4, 19).

Several Ubs have been identified in fungi (11, 15, 16) and analyzed for their functions in cell biology. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ub genes, named UBI1, UBI2, UBI3, and UBI4 (10) were expressed under stress conditions including heat stress and starvation (4, 12). Aspergillus nidulans Ubs were strongly expressed in the presence of antifungal drugs like amphotericin B and miconazole (10). Therefore, we hypothesized that Ubs in fungi might be related to resistance against antifungal drugs.

Dermatophytoses are dermatophyte infections in keratinized tissues, i.e., epidermis, hair, and nails (9). In a previous study (8), the Ub gene of Trichophyton mentagrophytes, the anamorph of Arthroderma benhamiae, which frequently causes human and animal infections (1), was cloned. The Ub gene of this dermatophyte encoded two Ub repeats (8).

Microsporum canis infection is most common in dogs and cats, and these animals can sometimes transmit the disease to humans (9). Accordingly, M. canis and T. mentagrophytes infections in humans and animals are most frequently treated with antifungal drugs.

In the present study, we have taken a genetic approach to the two Ub repeats in M. canis and T. mentagrophytes in relation to a possible role in resistance against antifungal drugs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

A standard strain of Arthroderma otae, (−) mating type, VUT-77055 (6), the teleomorph of M. canis, and a standard strain of Arthroderma benhamiae, (+) mating type, VUT-77011 (RV 26678) (1), one of the teleomorphs of T. mentagrophytes, were used in this study.

Preparation of cDNA.

The mycelial samples were obtained by culturing the dermatophytes in Sabouraud's dextrose broth (9) at 27°C for 7 days. The mycelia were collected by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 5 min, and then they were homogenized in liquid nitrogen. Total RNAs were extracted from 500-μg samples with RNeasy total RNA kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, Calif.). Reverse transcription (RT) of the poly(A)+ RNA was performed with an Omniscript reverse transcriptase kit (QIAGEN).

Cloning of the M. canis Ub gene.

PCR primers were prepared based on the sequences from T. mentagrophytes (8). The primer sequences used for amplification of M. canis Ub were 5′-ATGCAAATCTTCGTGAAAAC-3′ (primer UB1S; nucleotides [nt] 162 to 181 in T. mentagrophytes Ub, GenBank accession no. AB025792) and 5′-CTCGAGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ [primer poly(dT)]. With these primers, a 740-bp fragment containing the coding sequence of Ub was expected to be amplified. The cDNA was amplified by PCR in a reaction mixture (30 μl) containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% gelatin, 200 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.0 U of Taq polymerase (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), and 0.5 μg of a primer pair. The PCR amplification was carried out for 35 cycles consisting of template denaturation (1 min at 94°C), primer annealing (2 min at 55°C), and polymerization (2 min at 72°C). The approximately 740-bp PCR product was analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel and then directly cloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The plasmid DNAs were extracted with the QIAGEN plasmid kit, and they were sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method using an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.).

RT-PCR assay of Ub induced by fluconazole.

We first determined the MIC of fluconazole against M. canis and T. mentagrophytes in Sabouraud's dextrose broth. The mycelial samples of M. canis and T. mentagrophytes were cultured in Sabouraud's dextrose broth containing 20 μg of fluconazole (Diflucan for injection; Pfizer, Tokyo, Japan) per ml. When these dermatophytes were cultured in medium containing more than 20 μg of fluconazole per ml, fungal growth was inhibited. Therefore, the amount of RNA extracted was not sufficient for investigation by RT-PCR assay.

After 5 days of culture at 27°C, mycelia were collected by centrifugation under the conditions stated above and homogenized in liquid nitrogen. RT of the poly(A)+ RNA was performed with an Omniscript reverse transcriptase kit (QIAGEN).

The cDNA samples (100 ng) were amplified by RT-PCR with UB1S and poly(dT) primers. The cDNA was amplified by PCR in a reaction mixture (30 μl) containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.001% gelatin, 200 mM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.0 U of Taq polymerase (Takara), and 0.5 μg of the primer pair. The PCR amplification was carried out for 24, 27, and 30 cycles consisting of template denaturation (1 min at 94°C), primer annealing (2 min at 55°C), and polymerization (2 min at 72°C).

As controls for gene expression, mRNA of the A. benhamiae chitin synthase 1 (CHS1) gene was determined. The primer sequences used to amplify A. benhamiae CHS1 were 5′-CAT CGA GTA CAT GTG CTC GC-3′ (primer CHS1 Uni1S; nt 943 to 960 in A. benhamiae CHS1) and 5′-CTC GAG GTC AAA AGC ACG CC-3′ (primer CHS1 Uni1R; nt 1368 to 1387 in A. benhamiae CHS1). With these primers, a 410-bp fragment containing the coding sequence of A. benhamiae CHS1 gene was expected to be amplified.

The PCR amplification was carried out for 30 cycles consisting of template denaturation (1 min at 94°C), primer annealing (2 min at 63°C), and polymerization (3 min at 72°C). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized with UV light.

Culture with fluconazole and proteasome inhibitor.

M. canis VUT-77055 and T. mentagrophytes VUT-77011 were cultured on diluted Sabouraud's dextrose agar (SDA) (2% glucose, 1% neopeptone, 1% MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1% KH2PO4, and 2% agar) (9) for 1 week at 24°C. M. canis and T. mentagrophytes were harvested from the diluted SDA and each fungus was suspended in 500 μl of sterile deionized water. The cells (microconidia, arthroconidia, and hyphae) were stirred and centrifuged at 300 × g for 3 min. The cells were resuspended in water and enumerated by direct microscopic count.

Approximately 1,000 cells/10 μl of M. canis or T. mentagrophytes were inoculated onto the center (spot diameter, 4 mm) of plates (diameter, 3 cm) which contained the diluted SDA and SDA with fluconazole (20 μg/ml) and/or β-lactone (1 μM) (Ub proteasome inhibitor; MBL, Aichi, Japan) (3). Since 1 mM β-lactone was an effective inhibitor for mammalian cells, β-lactone was used at this concentration (3). Three plates of each inoculum were cultured for 5 days at 27°C, and then the diameters of the fungal colonies were measured. Mean diameters of the colonies on diluted SDA with fluconazole alone and on media with fluconazole and/or β-lactone were analyzed by Student's paired two-tailed t test.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequences for M. canis Ub reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AB035543.

RESULTS

M. canis Ub gene.

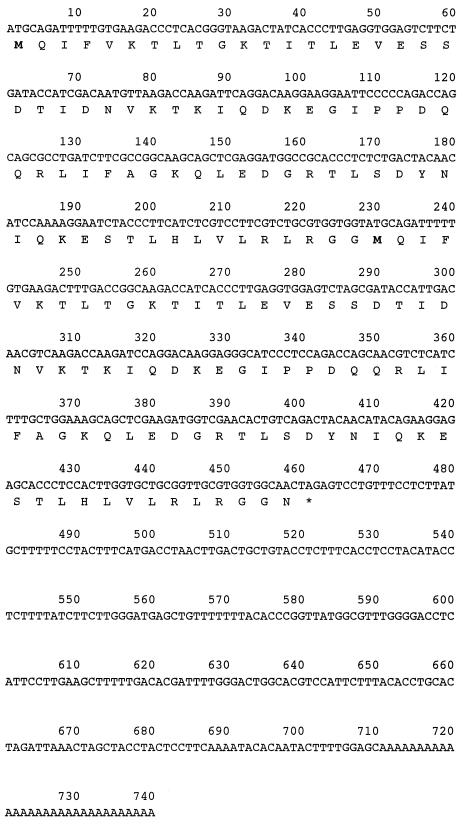

Using M. canis cDNA as a template, we isolated the M. canis Ub gene by PCR amplification with the UB1S and poly(dT) primers. Electrophoresis of the PCR product gave a single DNA band with an expected size of approximately 740 bp. After this DNA fragment was cloned into a pCRII plasmid vector, the nucleotide sequence of the PCR-amplified cDNA clone [Ub1S-poly(dT)] was revealed to be 740 bp and displayed greater than 99% similarity with that of the T. mentagrophytes Ub gene. The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the M. canis Ub gene also encoded two Ub repeats in bp 1 to 460 (Fig. 1), just like those of T. mentagrophytes (8).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of M. canis ubiquitin cDNA. The M. canis Ub gene encoded two Ub repeats in bp 1 to 460 (the first Ub is bp 1 to 230). Residues are numbered from the 5′ end of the coding region. The deduced amino acid sequence is shown by the single-letter amino acid code under the nucleotide sequence. Asterisk, identities with stop codon (TAG).

The deduced amino acid sequence of M. canis Ub was identical in sequence to that of T. mentagrophytes (GenBank accession no. AB025792) (8).

Ub mRNA induced by fluconazole.

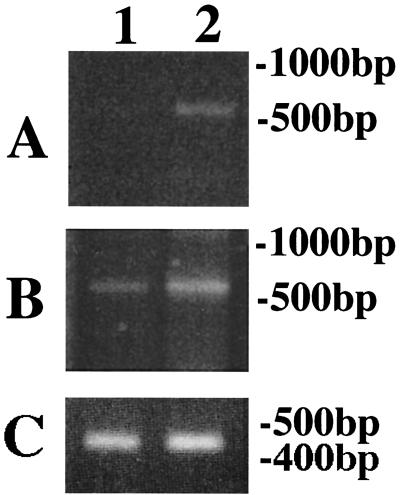

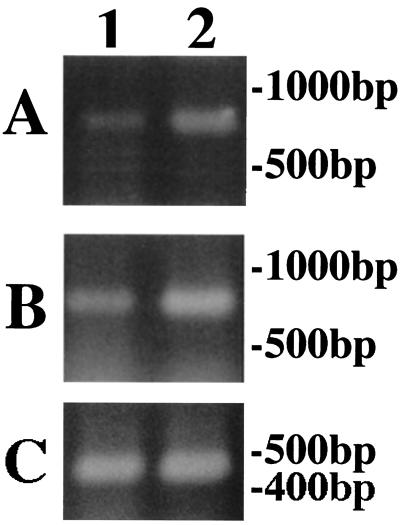

After 27 cycles of amplification by RT-PCR, Ub mRNA was detectable in M. canis and T. mentagrophytes when cultured with fluconazole rather than without fluconazole (Fig. 2 and 3), suggesting that fluconazole might stimulate the expression of Ub mRNA in the dermatophytes.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR assay of Ub induced by fluconazole using UB1S and poly(dT) primers. The PCR products from M. canis cDNAs were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel. M. canis was cultured in Sabouraud's broth (lane 1) or in Sabouraud's broth containing fluconazole (20 μg/ml) (lane 2). (A) PCR amplification was carried out for 27 cycles. (B) PCR amplification was carried out for 30 cycles. (C) controls for gene expression to compare the levels of mRNA. The CHS1 gene of M. canis was amplified for 30 cycles.

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR assay of Ub induced by fluconazole using UB1S and poly(dT) primers. The PCR products from T. mentagrophytes cDNAs were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel. T. mentagrophytes was cultured in Sabouraud's broth (lane 1) or in Sabouraud's broth containing fluconazole (20 μg/ml) (lane 2). (A) PCR amplification was carried out for 27 cycles. (B) PCR amplification was carried out for 30 cycles. (C) Controls for gene expression to compare the levels of mRNA. The CHS1 gene of T. mentagrophytes was amplified for 30 cycles.

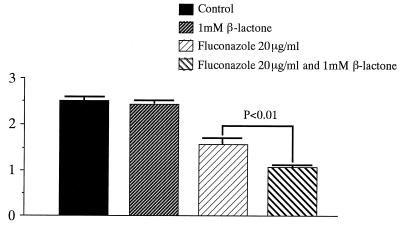

Effects on fungal cell growth of fluconazole and proteasome inhibitor.

The mean diameters of the colonies of M. canis and T. mentagrophytes cultured on the diluted SDA alone or with fluconazole and/or β-lactone were calculated (Fig. 4 and 5). The mean diameters of the colonies of M. canis on the diluted SDA and on the diluted SDA with β-lactone (1 μM) were 2.5 and 2.4 cm, respectively. The mean diameters of the colonies of T. mentagrophytes on the diluted SDA and on the diluted SDA with β-lactone (1 μM) were 2.4 and 2.3 cm, respectively.

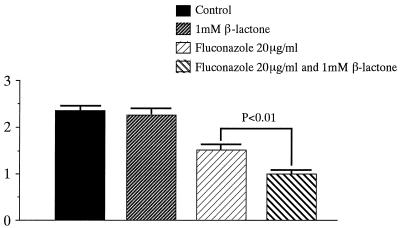

FIG. 4.

An estimated 1,000 cells of M. canis were cultured in diluted Sabouraud's agar with fluconazole (20 μg/ml) and/or 1 μM β-lactone. After 5 days at 27°C, colony diameters were measured (units on the y axis are in centimeters).

FIG. 5.

An estimated 1,000 cells of T. mentagrophytes were cultured in diluted Sabouraud's agar with fluconazole (20 μg/ml) and/or 1 μM β-lactone. After 5 days at 27°C, colony diameters were measured (units on the y axis are in centimeters).

The mean colony diameters of the colonies of M. canis and T. mentagrophytes on SDA with fluconazole (20 μg/ml) were 1.7 and 1.5 cm, respectively. The mean diameters of the two fungi on the media with fluconazole (20 μg/ml) and β-lactone (1 μM) were 1.2 and 1.1 cm, respectively. Statistical analysis of the mean diameters of colonies on diluted SDA with fluconazole and with fluconazole and β-lactone revealed significant differences between these groups (P < 0.01). These results suggested that Ub proteasome inhibitor might enhance the antifungal activity of fluconazole against M. canis and T. mentagrophytes.

DISCUSSION

The Ub gene in M. canis also encoded two Ub repeats, which has not been reported for fungi other than T. mentagrophytes (8). Two Ub repeats might be a common feature in dermatophytes. However, the precise function of this type of Ub has not been clarified in dermatophytes. Noventa-Jordao et al. reported that A. nidulans Ubs were strongly expressed in the presence of antifungal drugs like amphotericin B and miconazole (10). However, the relationship of Ubs and drug resistance in fungal cells has not been well investigated.

In this study, RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that fluconazole also stimulated Ub mRNA production in M. canis and T. mentagrophytes. The Ub proteasome inhibitor increased the antifungal activity of the fluconazole against M. canis and T. mentagrophytes. Therefore, expression of the Ub gene in fungi might be enhanced by different kinds of antifungal drugs and may correlate with resistance to drugs. The diluted SDA is preferable for determining the effects of drugs, as this medium contains a lower concentration of nutrients.

Fluconazole has been most widely used as an antifungal drug, since it can be given orally and parenterally, lacks major side effects, and has broad efficacy against Candida albicans infections (2). The treatment of oral candidiasis in AIDS patients encountered clinical resistance due to the emergence of fluconazole-resistant strains as a result of prolonged fluconazole therapy for recurrent infections (2). Therefore, we presumed that dermatophytes might also be resistant to fluconazole and were interested in the resistance mechanism of fluconazole in dermatophytes. Fischman et al. reported that levels of fluconazole >10 μg/g of human tissue were needed to treat infection with Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides immitis, and Histoplasma capsulatum (5). This observation prompted us to adjust the concentration of fluconazole in the medium to 20 μg/ml for our experiments on the effect of fluconazole and/or proteasome inhibitor on fungal growth.

There is no evidence that the inhibition of β-lactone is interfering with sterol biosynthesis. This might be just an additional effect of two inhibitors acting independently.

Ub was found to localize predominantly in the cell wall area of C. albicans by immunofluorescence analysis with the commercial antisera of anti-Ub (13), suggesting that Ub might be associated with different receptor-like components at the cell surface. For example, Ubs combined with the laminin receptor, fibrinogen-binding mannoprotein, and candidial C3d receptor of C. albicans (13). Therefore, Sepulveda et al. suggested that ubiquitination might modulate the activities of these receptors (13, 14) and ubiquitinated receptors could be related to antifungal drug resistance. Further analysis is required to elucidate the precise role of Ub in the resistance of dermatophytes against antifungal drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Errol Reiss, Mycotic Diseases Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajello L, Cheng S. The perfect state of Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Sabouraudia. 1967;4:230–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowen L E, Sanglard D, Calabrese D, Sirjusing C, Anderson J B, Kohn L M. Evolution of drug resistance in experimental populations of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1515–1522. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1515-1522.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dick L R, Cruishank A A, Destree A T, Grenier L, McCormack T A, Melandri F D, Nunes S L, Palombella V J, Parent L A, Plamondon L, Stein R L. Mechanistic studies on the inactivation of the proteasome by lactacystin in cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:182–188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finley D, Ozkaynak E, Varshavsky A. The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stress. Cell. 1987;48:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischman A J, Alpert N M, Livni E, Ray S, Sincair I, Callahan R J, Correia J A, Webb D, Strauss H W, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of 18F-labeled fluconazole in healthy human subjects by positron emission tomography. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1270–1277. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa A, Usui K. Nannizzia otae sp. nov, the perfect state of Microsporum canis Bodin. Jpn J Med Mycol. 1975;16:148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system for protein degradation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:760–807. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kano R, Nakamura Y, Watari T, Watanabe S, Tsujimoto H, Hasegawa A. Repeated ubiquitin genes in Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Curr Microbiol. 1999;39:302–305. doi: 10.1007/s002849900463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon-Chung K J, Bennett J E. Medical mycology. 1992. pp. 136–137. and 816–817. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noventa-Jordao A M, Nascimento A M, Goldman M H S, Terenzi H F, Goldman G H. Molecular characterization of ubiquitin genes from Aspergillus nidulans: mRNA expression on different stress and growth conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1490:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Özkaynak E, Finley D, Solomon M J, Varshavsky A. The yeast ubiquitin genes: family of natural gene fusions. EMBO J. 1987;6:1429–1439. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Özkaynak E, Finley D, Varshavsky A. The yeast ubiquitin gene: head-to-tail repeats encoding a polyubiquitin precursor protein. Nature. 1984;312:663–666. doi: 10.1038/312663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sepulveda P, Lopez-Ribot J L, Gozalbo D, Cervera A, Martinez J P, Chaffin W L. Ubiquitin-like epitopes associated with Candida albicans cell surface receptors. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4406–4408. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4406-4408.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sepulveda P, Cervera A M, Lopez-Ribot J L, Chaffin W L, Martinez J P, Gozalbo D. Cloning and characterization of cDNA coding for Candida albicans polyubiquitin. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:315–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer E D, Spitzer S G. Structure of the ubiquitin-encoding gene of Cryptococcus neoformans. Gene. 1995;161:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00231-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taccioli G E, Grotewold E, Aisemberg G O, Judewicz N D. Ubiquitin expression in Neurospora crassa: cloning and sequencing of a polyubiquitin gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6153–6165. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varshavsky A. The n-end rule. Cell. 1992;69:752–735. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90285-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiborg O, Pedersen M S, Wind A, Berglund L E, Marcker K A, Vuust J. The human ubiquitin multigene family: some genes contain multiple directly repeated ubiquitin coding sequences. EMBO J. 1985;4:755–759. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamao F. Ubiquitin system: selectivity and timing of protein destruction. J Biochem. 1999;125:223–229. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]