Abstract

Background

Reflection in postgraduate medical education has been found to aid in the development of professional skills, improve clinical expertise, and problem solving with the aim of advancing lifelong learning skills and self-awareness, leading to good medical practice among postgraduate residents. Despite the evidenced benefits, reflection remains underused as a tool for teaching and learning, and few trainee physicians regularly engage in the process. Factors that affect the uptake of reflective learning in residency training have not yet been adequately explored.

Objective

The purpose of this review is to demonstrate the factors that influence the adoption of reflective learning for postgraduate students and their centrality to good clinical practice.

Methods

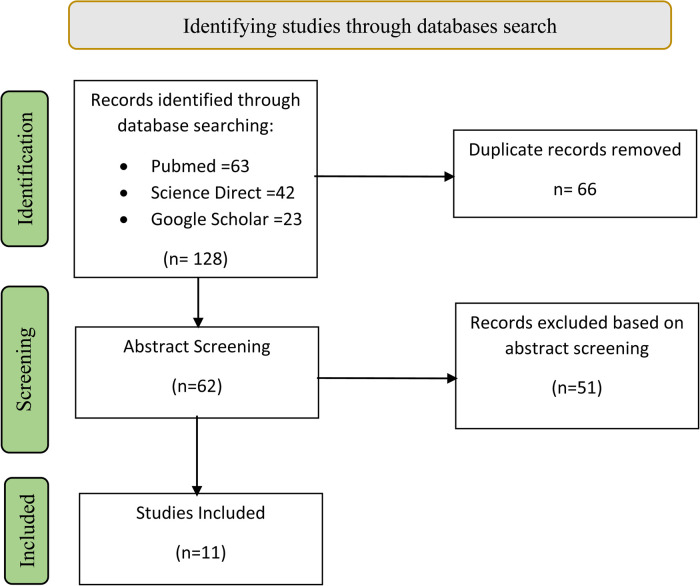

A review of the literature was performed using defined databases and the following search terms: ‘reflection’, ‘reflective learning’, ‘postgraduate medical education’, ‘barriers’ and ‘facilitators’. The search was limited to peer-reviewed published material in English between 2011 and 2020 and included research papers, reviews, and expert opinion pieces.

Results

Eleven relevant articles were included, which identified three main categories as facilitators and barriers to the adoption of reflective learning in postgraduate medical education. These included structure, assessment and relational factors. The structure of reflective practice is important, but it should not be too rigid. Assessments are paramount, but they should be multidimensional to accommodate the multicomponent nature of reflections. Relational factors such as motivation, coaching, and role modeling facilitate sustainable reflective practice.

Conclusions

This review suggests that the same factors that facilitate reflection can be a barrier if not used within the right epistemic. Educators should consider these factors to increase the acceptance and integration of reflective learning in curriculums by both teachers and learners.

Keywords: reflection, reflective learning, postgraduate medical education, barriers, facilitators

Introduction

Reflection is a process that involves using previous experiences to create greater insight and understanding of a situation so that this newly acquired understanding can inform future actions. 1 Reflection is the art of ‘thinking about one's actions during or after the action, usually with the aim of improving performance’. 2 A reflection framework involves careful thinking and exploring critical experiences and considering their implications for future practice. 3 Its structure is somewhat difficult, and there is still no consensus on its definition. 4

In recent decades, reflective learning and reflection have become familiar terms and widely accepted by medical educators, with a good amount of robust literature published on the subject. 5 Dewey 6 was one of the first philosophers to come up with the concept of reflection, referring to it as the ‘reconstruction or reorganization of experience that adds to the meaning of the experience’, in essence, a meaning-making process. Moon, 7 however, cautions us not to merely consider reflection as a recollection of experiences but as a complex mental process. Reflective learning is what happens in this process and has been defined by Kolb 8 as ‘the process by which knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’.

Despite these significant contributions to understanding the meaning of reflection in medical education, there is little consensus on the nature of reflection and how it should be structured, practised, and assessed in medical education.

Furthermore, to promote reflective learning, the current use of an instrumental approach has gained popularity within medical education and professional studies. It provides useful framing devices to help conceptualize some important processes in reflective learning. 5 This review examines the barriers and facilitators surrounding the learning of reflection in graduate studies, offering suggestions on how to promote it in postgraduate medical education.

Methods

Aim

The purpose of this review is to demonstrate the factors that influence the adoption of reflective learning for postgraduate students and their centrality to good clinical practice.

Study Question

Two research questions guided this study:

- What are the facilitators of reflective learning in postgraduate medical education?

- What are the barriers to reflective learning in postgraduate medical education?

Study Design

This article was written based on a narrative review of literature. 9

Results

Eleven relevant articles were found. They were classified according to methodology (see Table 1. Relevant studies). This review included six qualitative studies of mixed categories (one umbrella review, one systematic review, and four narrative reviews), one literature review, one mixed method study, and three reviews / opinions of the authors. Qualitative methodology was the main research output, providing largely descriptive data and, for the most part, were thoroughly described and of good quality.

Table 1.

Relevant studies: facilitators and barriers.

| Study methodology | Author | Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative - Umbrella Review | Fragkos, 2016 |

|

|

| Qualitative - Systematic Review | Winkel, 2017 |

|

|

| Qualitative – Non-Systematic review | Ng, 2015 |

|

|

| Qualitative – Narrative review | Platt, 2014 |

|

|

| Qualitative – Narrative review | Checticut, 2011 |

|

|

| Literature review | Chaffey, 2012 |

|

|

| Mixed methods | Bruno, 2017 |

|

|

| Expert opinion / report | R and S, 2011 |

|

|

| De la Croix, 2018 |

|

|

|

| Naidu and Kumagai, 2016 |

|

||

| Wass, 2014 | • Acknowledging individuality in reflective practice | • Lack of mentoring |

The results of reflective learning in postgraduate medical education are summarized below based on methodology and findings (Table 1). An analysis of emerging themes is also provided (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Summary of findings based on themes that emerged.

| Themes | Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

| Assessments |

|

|

| Relational Factors |

|

|

Facilitators

Structure

-

Curriculum alignment

Understanding the context of the reflective exercise and its alignment within the curriculum helps facilitate reflection for graduate students.10,11 In this review, Chaffey et al 12 noted that for learners to reflect effectively, they need to understand the benefits of reflection and its place in their academic studies. Another study noted that this allows the learner to diagnose individual learning needs, set learning objectives, identify a suitable learning strategy, and decide how to evaluate the learning outcome. 13

-

Flexibility in the instructional approach

Theorists like Gibbs (1988) and Kolb (2014) describe the reflective process itself as a nonlinear and cyclic process, illustrating the ongoing development of a practitioner. Subsequent models have described conceptual frameworks that include key steps or sets of processes that may be deemed necessary in the reflective process. 4 Although this may be important in providing a good starting point for naïve reflectors, current research now argues for a less rigid structure in graduate learning. Teachers are urged to allow ‘sufficient flexibility of choice within the existing range of reflection frameworks’ 14 to further reflective learning. De la Croix et al, 15 support this statement by adding that this would accommodate learners with personality types or learning preferences that do not naturally support reflective practice.

-

Creative writing

Appreciating differences in the methodology of reflective writing is of utmost importance. Platt 10 states that teachers should move toward a more humanistic approach to reflective practice and accommodate more novel approaches to reflection away from traditional methods like journal writing and portfolios of learning.

-

Safe environment

Creating conditions that foster reflection rather than imposing a predetermined reflective format on students has been argued to be the ideal structure to facilitate reflection. 16 Indeed, it is about time that academics change their view of reflection from a ‘one-way’ scientific-centred approach to a more artistic skill that can be implemented in multiple ways. 10 In his article, Drissen 17 adds that providing a trusted environment can stimulate a reflective mind and foster attributes of lifelong learning.

-

Accommodating diversity

Wass et al, 14 suggest that allowing students to navigate their way around an approach to reflective practice may be crucial in accommodating their diverse learning styles. This theme has been mentioned by other authors.2,15,18 In an opinion piece, 15 De la Croix reports that acknowledging the diversity of reflection will allow educators to move away from a ‘checklist approach’. Practically, this means that students can work out their own way of engaging in reflection.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Showing Studies Selection. 32

Assessment

-

Use of Portfolios of Learning

In initial skill acquisition, several authors found that adopting instructional approaches with some structure is superior compared to following some abstract principles of reflection.12,19,20 The portfolio was considered important to capture and store workplace-based assessments and feedback, which can be used further during formative and summative assessments. 19 Other tools, such as journaling, have been found to help students reflect on action and develop metacognitive skills. 20 Web-based portfolios seem to receive a lot of attention from students as they give a provision of revisiting and editing the assessment and can also aid in future references. 11 However, not all learners perceive this tool as enhancing their ability to reflect, 12 and factors like poor perception and lack of confidence in building a portfolio may affect the depth of reflection.

-

Formative assessment

Evidence supports that providing ongoing feedback on student reflective writing, rather than summative, can promote the improvement of the depth and quality of reflective practice over time. 20 Students seem to appreciate a continuous and longitudinal formative assessment, but more so the feedback from supervisors that accompany it.

-

Incorporating multiple approaches

Despite the fact that evaluating the reflective process would help exclude subjectivity from this process and become beneficial in the formative assessment, facilitators must be aware that it may not be a ‘one-size-fits-all’ assessment process. 13 Nguyen et al, advises not to dichotomize the reflection assessment based on its multicomponent nature but rather use a multidimensional scale that can measure the development of reflective practice. 4

-

Faculty Development

Naidu et al 2 mention that teachers of higher medical education need to receive some training on how to facilitate and measure reflection in postgraduate students. Those who teach and support our students’ learning must be effectively trained; otherwise, the assessment validity of reflective practices would raise concerns as to whether they measure what they are supposed to.

-

The Sociocultural Context in Reflection

Innovating different ways to incorporate reflection, such as group reflection, may promote an interactional social dimension that could enhance its output. Naidu 2 further suggests that this transformative approach would lead to the transference of reflective practice from a solitary, inward act and externalizing it to a social act, making it more meaningful. Wass et al, 14 support this idea by adding that learners need to understand that reflection not only leads to personal growth and development but also has the potential to impact those around them.

Relational Factors

-

Role modeling

According to Chaffey et al, 12 modeling of reflective practice by faculty and tutors is significant in facilitating students’ reflective capacity. Additionally, faculty who reflect and are trained to be expressive about their reflections are better at modeling this to their learners. A teacher who models reflection acts as a catalyst that can stir ideas of reflection in their students.

-

Coaching

Coaching helps learners identify their own learning needs and know what questions to ask to enhance the reflective process. 12 Learners are more likely to develop a culture of reflection if they see their faculty reflecting regularly and benefitting from this work practice daily. 21

-

Empowerment

A move to empower students to reflect, rather than imposing reflection on them, may be the fundamental change that would be needed to improve their acceptance by graduate students. 16 Tutors who provide a facilitative framework and leave control and responsibility for learning to students may ultimately improve the sustainability of reflective practice beyond graduation.

-

Motivation of students

Motivation in the academic setting has been unequivocally found to facilitate reflection by several authors.10,12,20 Internal motivation is essential to avoid rote learning and encourage the practice of reflection. Platt 10 reports that educators who facilitate student diversity in reflecting, away from a simple tick-box activity of recording achievement, have a higher chance of motivating learners to embed this into their higher education culture. De la Croix 15 adds that motivation is what makes students turn reflection into a lifelong practice. External motivating factors, such as assessment and supervision, also play a role in facilitating reflection in graduate students by increasing task motivation, as Chaffey et al 12 reported in their study.

-

Motivation of teachers

For teachers to motivate learners, they must be equally motivated. This comes from the acquisition of skills that create confidence to facilitate and practice reflection. Chetcuti et al, 21 advise on the importance of peer mentorship among teachers, stating that mentoring new teachers and involving them in reflective activities may build interest and morale in the subject. Motivation is not a one-sided attribute; it is a noteworthy observation that motivated students motivate their teachers and vice versa.

Barriers

Structure

-

Ambiguity in the purpose of reflection

In his study, 12 Chaffey noted that the purposes of reflective tasks were often ambiguous for the students, leaving them unaware of their intentions to facilitate learning.

-

Epistemological incongruence

Ng et al, 22 report that some of the ways reflection is being applied seem to be ‘divorced from the original theories of reflection and reflective practice’. Other reports15,18,22 note that adopting such an approach stems from a reductionist mindset and is therefore incongruent with the philosophical underpinnings of reflection and reflective practice. According to Fragkos et al, 18 a reductionist approach appears to guide the teaching of reflective learning based on certain principles such as evidence-based medicine, rather than on the artistic-philosophical underpinnings of reflective medicine.

-

A utilitarian approach

One of the many cautions of the reviewed studies is the avoidance, as much as possible, of a utilitarian approach.18,22 The instrumental approach adapted by teachers in medical education tends to dilute the richness that comes with true reflection into a simple tick-box exercise, making it less meaningful. 20 The prescriptive nature of reflective exercises may require learners to follow a guide in an effort to pass embedded assessments rather than genuinely engage in reflective behaviour. 15

Assessment

-

Ambiguity in Assessment Tools

The assessment tools we choose, as De la Croix 15 advises, can influence whether the human nature of reflection remains or is eliminated in the process. He argues that it then becomes challenging for another person to judge whether the student has reflected and, if so, the quality of the reflection.

-

Summative assessments

An outcome focus of the assessments can be a limiting factor to genuine reflection.10,15 In fact, as Platt 10 would argue, the summative assessment of reflection is questionable. Assessment tools may not be able to reliably distinguish ‘reflective zombies’ as one author has called them 15 from students who reflect authentically. Furthermore, the demonstration of reflection using checklists can dilute its impact, resulting in scripted output in learners without the awareness of true reflection.

Relational Factors

-

Time factor

Time is an essential commodity required for reflection to occur, as Chaffey et al 12 noted. This is often elusive for postgraduate trainees due to competing demands in higher education and may hinder the development of true reflective practice. 10

-

Lack of motivation

Wass et al, 14 suggest that teaching reflection in its simplicity to students and trainees, then fostering acceptance from their end, is often a challenging task. He further argues that reflection is essentially individualistic and introspective; hence, internal motivation plays a vital role in its implementation and, therefore, its absence may turn a meaningful exercise into a redundant ritual.

-

Poor teacher training, confidence, and commitment

According to Platt, 10 teachers who lack confidence and commitment can also result in poor and ‘staged’ reflections from their learners. This may be borne out of the lack of training, and hence lack of knowledge on how to facilitate reflection. Platt warns that this may lead to a mimicry form of reflection, reducing its pedagogical function to merely an ideology. Poor tutor perception of reflective learning, leading to a lack of commitment in its implementation, was another critical factor in determining the value that students placed on the reflection activity. 12

Discussion

The factors that affect reflective learning in postgraduate training are either positively or negatively affected by issues that revolve around three themes that are more elaborately discussed below.

Structure

From the analyzed literature, it is arguable that a form of reflective practice guidance provides opportunities for graduate students to synthesize and evaluate issues emerging from clinical experiences and may support the development of clinical judgment. This agrees with previous reviews 23 that report that reflective tools without guidelines had little effect on developing reflective skills, while instructive guidelines amplified student learning. We find that, for example, making explicit the actions to be taken after thinking about the experience may serve as a guide to begin the reflective process.

In addition, reflective learning must correspond to its purpose and both students and faculty must know its desired form and function. It should not in any way describe specific outcomes that a reflective exercise must achieve, but rather its process, as Nguyen et al 4 reported. The evidence in this review points to the fact that an outcome-based approach is redundant and would lead to poor and less meaningful reflection. This is similar to previous reviews 24 that caution the assumption that there is a specific prescription to the structure of reflection in medical education that tends toward a ‘recipe following’ instrumentalist approach and with a scientific outlook. It will ultimately threaten its meaningful outcome.

Moreover, these results suggest that an open structure is applicable once learners have developed their reflective skills, as standardized reflection may impede students with good reflective skills. 12 We conclude that flexible structures that accommodate diversity in learning styles may be more helpful for reflection, particularly in graduate studies. Junior residents or those naive to reflection may need more structure in the beginning and later graduate to an open approach as they mature to be critical reflectors.

Models and guidelines have been shown to help students structure their thinking and learning. We reckon that it is unrealistic to expect one reflective model to be effective for all. Furthermore, the most significant risk accompanying these reflection models is when they are turned into checklists that students work through mechanically. 24 This was not Schön's original purpose for this tool. We argue that current reflective practices taught and practiced in institutions of higher education suffer incongruence with the philosophical underpinnings due to an overemphasis on the quantification of achievement through the measurement of learning outcomes. Reflection, based on its theoretical roots, has no ‘outcome’, ‘proof’ or ‘evidence’ of what really happened. A realignment of reflective learning and practice in higher education based on the fundamental theories that guide its practice can solve the problem of ‘how’ to structure and assess reflection.

We acknowledge that with respect to the content of reflection, the use of a shared discourse so that students and teachers can develop reflections from common understandings and vocabulary is indeed key to facilitating its practice, as reported by some authors.11,22 This mirrors the previous literature reviewed where most authors agree that reflective strategies must be content-specific in line with their original intentions and unifying the models and definitions as of practical benefit to the reflective student and teacher. 4

Empowering learners to truly reflect intrinsically shapes them to be critical and autonomous scholars. Respecting the autonomy of learners’ needs must remain central in the learning process. However, this individualistic nature of reflection can also be criticized in current practice since it denies learners the opportunity for peer learning through reflection among colleagues and other interprofessional teams. Therefore, reflection should be contextualized within the sociocultural environment, based on its theoretical background. This is consistent with the findings of previous authors,24,25 which report an interplay between the person reflecting and his or her local context. The solution lies in providing a balance between adopting a social context and accommodating the individuality of the learners in the reflective process.

Incorporating reflection into higher education curriculums and embedding it at the programme level, mapping it across specific learning programmes rather than its practice in silos, within specific modules, may allow for more emphasis to be placed on it. 10

Assessments

Similarly to previous studies, the findings of this study generally advocate the use of some form of assessment according to the foundational principles of assessment in that it drives and motivates learning. 26

Some studies in this review found that the assessment of reflection as a competence requires its demonstration through portfolios. 21 This we found to be a plausible reason to incorporate reflective writing in portfolios in postgraduate training. They act as a repository to track the engagement of students in their reflective capacities. This is similar to other medical education literature, where scholars have found portfolios to complement traditional measures of student competence. 27 In addition to portfolios, the use of reflective writing assignments and journals to facilitate reflective practice has also been previously documented. 28 Recent trends include the use of rubrics such as REFLECT 29 in measuring reflective activities; however, experimental evidence for their generalizable efficacy is limited.

Therefore, the results of this review point to portfolios that act as facilitators of learning. We argue that in as much as they have their utility, the balance lies in avoiding overly regulating tools of measuring reflection, as they might unintentionally serve as tools for scrutiny and governance rather than as opportunities for active learning.

In the case of the type of assessment, we argue that summative reflection assessments are an impediment to reflective practice, whereas formative feedback assessment promotes reflective practice. This is in line with previous studies 30 and has been suggested by Platt 10 in his review. The findings further suggest the importance of teacher feedback within the formative assessment, as it had significant positive findings on student learning. These results are similar to a previous review by Aronson et al, 23 suggesting that the process of reflection in higher education requires guidance, critique, feedback, and reinforcement rather than just more practice.

To enhance reflective culture in learning institutions, avoiding standardized reflective assessments for learners and allowing personal choice within a specific range of theoretical frameworks may be a possible solution. Indeed, the results of this analysis argue that a utilitarian approach serves as an impediment to reflection.18,22 We conclude from the reviewed literature that assessment methods and tools are not entirely problematic in themselves but may need a more holistic approach, accommodating the diversity of students and allowing a fair amount of adaptation by educators.

Relational Factors

Concerning motivational prerequisites in reflective learning, it greatly facilitates reflective learning, especially since it is rooted in student-teacher relationship factors such as coaching and mentorship, all of which result in creating a safe and positive environment for students to reflect. Mentorship, as theorists like Schön reported, enhances reflective learning. 31 Role modeling and coaching is another facilitator of reflective practice found in this literature review.11,12,21 Evidence indicates that if students are unclear about the process of reflecting, do not see how it is linked to curriculum or assessment, and do not see educators modeling reflective behaviours, they are likely to undervalue this vital skill regardless of the associated learning. 12 Study findings are consistent with previous literature that coaching, role modelling, and motivation of both the students and teachers collectively facilitate reflective learning. 30 The importance of a trusting relationship between students and their teachers was also highlighted in previous review. 24

Conclusion

From these articles, there is credible evidence to support the notion that reflection is an essential aspect of graduate student learning and has the potential to achieve meaningful development of good medical practice. These intended outcomes will only be achieved if careful attention is paid to reflective processes.

Emerging themes did not reveal any consensus on the ‘best practice’ of how reflection should be structured or taught. The barrier with the current structure of reflection is that it is less in tandem with the epistemology of practice by trying to fit an artistry idea into the scientific model of outcome-based practice. The assessment techniques used in reflective practice (summative, formative, group vs. individual) may have been associated with learning but should be flexible enough to allow the multidimensional aspects of reflective practice. Relational factors are significant contributors to sustainable reflective practice, and both learners and teachers seem to agree that their absence may deter the development of reflective capacity.

Collectively, the twelve reviewed studies suggest that the same factors that facilitate reflection can act as barriers if not used within the right theoretical, practical and contextual background. Structure is important, but it should not be too rigid. Assessments are paramount, but they should be multidimensional to accommodate the multicomponent nature of reflections. Internal motivation within a backdrop of external coaching and role modeling by coaches and mentors is, indeed, a very effective tool in facilitating reflection. A trusting relationship with the teacher and an environment in which the student feels safe are prerequisites.

Educators and students have the potential to benefit from reflective learning in graduate studies. This requires overcoming many obstacles such as lack of motivation, time, and knowledge of the practice of reflection. Awareness of these factors is vital to developing effective educational strategies.

Indeed, facilitating reflective learning has its challenges, which, if overcome, are value-added to postgraduate medical learning. Educators who wish to incorporate reflective practice into residency curricula will need to be innovative, resilient, and willing to challenge norms while adopting sustainable practices.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sandars. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44: Medical Teacher: Vol 31, No 8. Published 2009. Accessed December 2, 2020. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01421590903050374?journalCode=imte20.

- 2.Naidu T, Kumagai AK. Troubling muddy waters: problematizing reflective practice in global medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(3):317-321. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2007;14(4):595-621. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen QD, Fernandez N, Karsenti T, Charlin B. What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component model. Med Educ. 2014;48(12):1176-1189. doi: 10.1111/medu.12583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boud D. Relocating reflection in the context of practice. In: ; 2010.

- 6.Dewey J. A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. DC Heath. 1933;1(1). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon JA. Reflection in learning and professional development: Theory and practice. Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolb. Kolb: Experiential learning: experience as the source… Google Scholar. Published 2014. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?hl=en&publication_year=1984&author=D. + A. + Kolb&title=Experiential + Learning.

- 9.Bryman A. Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platt L. The ‘wicked problem’ of reflective practice: a critical literature review. Innov Pract. 2014;9(1):44-53. doi: 10.24377/LJMU.iip.vol9iss1article108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkel. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. PubMed. Published 2017. Accessed December 2, 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28824754/.

- 12.Lj C, Ej de L, Ga F. Facilitating students’ reflective practice in a medical course: literature review. Educ Health (Abingdon, England). 2012;25(3):198-198. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.109787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Shea E. Self-directed learning in nurse education: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(1):62-70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wass V, Harrison C. Empowering the learner to reflect: do we need another approach? Med Educ. 2014;48(12):1146-1147. doi: 10.1111/medu.12612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Croix A, Veen M. The reflective zombie: problematizing the conceptual framework of reflection in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(6):394-400. doi: 10.1007/s40037-018-0479-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hays R, Gay S. Reflection or “pre-reflection”: what are we actually measuring in reflective practice? Med Educ. 2011;45(2):116-118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03813.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driessen E. Do portfolios have a future? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22(1):221-228. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9679-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fragkos KC. Reflective practice in healthcare education: an umbrella review. Educ Sci. 2016;6(3):27. doi: 10.3390/educsci6030027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heeneman S, de Grave W. Tensions in mentoring medical students toward self-directed and reflective learning in a longitudinal portfolio-based mentoring system: an activity theory analysis. Med Teach. 2017;39(4):368-376. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1286308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruno A, Dell’Aversana G. Reflective practice for psychology students: the use of reflective journal feedback in higher education. Psychol Learn Teach. 2017;16(2):248-260. doi: 10.1177/1475725716686288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chetcuti D, Buhagiar MA, Cardona A. The professional development portfolio: learning through reflection in the first year of teaching. Reflective Pract. 2011;12(1):61-72. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2011.541095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng SL, Kinsella EA, Friesen F, Hodges B. Reclaiming a theoretical orientation to reflection in medical education research: a critical narrative review. Med Educ. 2015;49(5):461-475. doi: 10.1111/medu.12680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aronson L, Niehaus B, Hill–Sakurai L, Lai C, O’Sullivan PS. A comparison of two methods of teaching reflective ability in year 3 medical students. Med Educ. 2012;46(8):807-814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boud D, Walker D. Promoting reflection in professional courses: the challenge of context. Stud High Educ. 1998;23(2):191-206. doi: 10.1080/03075079812331380384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raelin JA. Toward an epistemology of practice. Acad Manag Learn Educ. 2007;6(4):495-519. doi: 10.5465/amle.2007.27694950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. How to design a useful test. In: Understanding Medical Education. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013:241-254. doi: 10.1002/9781118472361.ch18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernsten L, Fernsten J. Portfolio assessment and reflection: enhancing learning through effective practice. Reflective Pract. 2005;6(2):303-309. doi: 10.1080/14623940500106542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boud D. Using journal writing to enhance reflective practice. Promot J Writ Adult Educ. 2001;6(90):43344-43356. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):41-50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823b55fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koole S, Dornan T, Aper L, et al. Factors confounding the assessment of reflection: a critical review. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):104. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schön. Schön: Educating the reflective practitioner - Google Scholar. Published 1987. Accessed: December 5, 2020. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?hl=en&publication_year=1983&author=D. + Sch%C3%B6n&title= + The + reflective + practitioner + .

- 32.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med 18(3): e1003583. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]