Abstract

Background

PRKAG2 syndrome is a rare disease characterized as left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), ventricular preexcitation syndrome, and sudden cardiac death. Its natural course, treatment, and prognosis were significantly different from sarcomeric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). However, it is often clinically misdiagnosed as sarcomeric HCM. PRKAG2 patients tend to experience delayed treatment. The delay may lead to adverse outcomes. This study aimed to identify the echocardiographic parameters which can differentiate PRKAG2 syndrome from sarcomeric HCM.

Methods

Nine PRKAG2 patients with LVH, 41 HCM patients with sarcomere gene mutations, and 202 healthy volunteers were enrolled. Clinical characteristics, conventional echocardiography, and three-dimensional images were recorded, and reviewed by an attending cardiologist. We evaluated the parameters of left ventricular strains from three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography (3D STE) by TomTec software. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves analysis was used to assess clinical and echocardiographic parameters’ differential diagnosis potential.

Results

The heart rate (HR) of the PRKAG2 group was significantly lower than both the healthy group (53.11 ± 10.14 vs. 69.22 ± 10.48 bpm, P < 0.001) and the sarcomeric HCM group (53.11 ± 10.14 vs. 67.23 ± 10.32 bpm, P = 0.001). The PRKAG2 group had similar interventricular septal thickness (IVS), posterior wall thickness (PWT), and maximum wall thickness (MWT) to the HCM group (P > 0.05). The absolute value of GLS in the PRKAG2 group was significantly higher than HCM patients (-18.92 ± 4.98 vs. -13.43 ± 4.30%, P = 0.004). SV calculated from EDV and ESV in PRKAG2 syndrome showed a higher value than sarcomeric HCM (61.83 ± 13.52 vs. 44.96 ± 17.53%, P = 0.020). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for HR + GLS was 0.911 (0.803 -1). For HR + GLS, the sensitivity and specificity of the best cut-off value (0.114) were 69.0% and 100%, respectively.

Conclusions

PRKAG2 patients present deteriorated LV diastolic function and preserved LV systolic function. Bradycardia and preserved GLS are useful to identify PRKAG2 syndrome from sarcomeric HCM, which may be beneficial for clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12947-022-00284-3.

Keywords: PRKAG2 syndrome, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 3D STE, Strain, GLS

Background

PRKAG2 syndrome is a rare cardiac abnormality manifesting left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) with electrophysiological abnormalities caused by mutations in the gene of the γ2 subunit (PRKAG2) of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [1, 2]. AMPK facilitates cellular glucose and fatty acid metabolic pathways. It acts as an enzymatic modulator of adenosine triphosphate utilizing pathways by phosphorylation [3]. The defect of the PRKAG2 gene alters AMPK’s activity resulting in excessive cellular glycogen storage. The perturbation in the exquisite regulation of cardiac metabolism leads to LVH, ventricular preexcitation, supraventricular arrhythmias, implantation of a pacemaker, and even sudden cardiac death [4–6]. Although PRKAG2 syndrome’s pathophysiology distinguishes it from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), the phenotype of LVH can mimic sarcomeric HCM and interfere with earlier differential diagnosis [7]. We aimed to identify the clinical and echocardiographic parameters that could differentiate PRKAG2 syndrome from sarcomeric HCM.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional, retrospective study included 252 participants of three groups: nine PRKAG2 patients with LVH, 41 HCM patients with sarcomere gene mutations, and 202 healthy volunteers. We excluded patients who were diagnosed with hypertension, aortic stenosis, or coronary heart disease. Mutations in PRKAG2 and sarcomere genes were identified by whole-exome sequencing and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects before participation.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography examinations were performed by an experienced licensed echocardiographic physician using Philips iE33 ultrasound machines (Philips Medical System, Andover, MA, USA). Standard apical four-chamber, apical two-chamber, apical long-axis, parasternal long-axis, and parasternal short-axis views were obtained with S5-1 transducer. Cardiac diameters were measured according to current guidelines [8]. Left ventricular wall asymmetry (LVWa) was the ratio of interventricular septum thickness (IVS) to left ventricular posterior wall thickness (PWT) measured in the parasternal long-axis view. Relative wall thickness (RWT) was measured as the ratio of 2* PWT over LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated using the biplane Simpson’s method.

Early and late transmitral velocity (E, A) were obtained using pulsed-wave Doppler echocardiography at the mitral valve inflow. Also, early diastolic and systolic mitral annular displacement velocity (e’, s’) were acquired using tissue Doppler echocardiography.

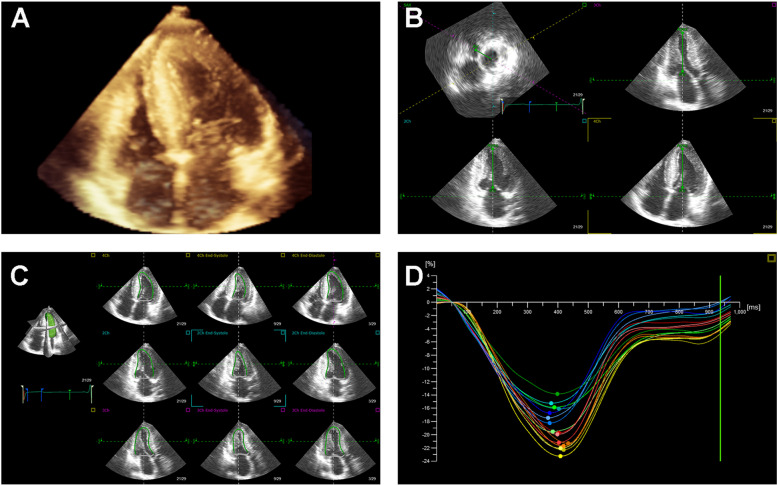

Three-dimensional images were recorded from the apical four-chamber view for four heartbeats using an X5-1 transducer. All 3D echocardiographic images were analyzed offline by TomTec software (TomTec Imaging Systems, Unterschleissheim, Germany). As shown in Fig. 1, the left ventricular (LV) endocardial border could be automatically tracked and then manually adjusted. Then, stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), global longitudinal strain (GLS), global circumferential strain (GCS), twist, torsion, systolic timing dispersion index (SDII), and systolic timing deviation index (SDI) of LV were calculated based on speckle tracking echocardiography (STE).

Fig. 1.

3D STE offline analysis. A An apical four-chamber 3D full volume image. B The points of the cardiac apex and mitral valve are manually adjusted for software automatic identification. C The endocardial border is traced and tracked in the apical triplane views. D An example of GLS obtained from 3D STE analysis

Echocardiography, electrocardiography, and blood pressure measurement were performed in all subjects at rest.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Normality was determined by Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test. T-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare numerical variables between the PRKAG2 group and other groups. Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze the differences between categorical variables. To evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of multiple variables to predict PRKAG2 syndrome, logistic regression was performed to combine parameters as a new predictor. Then, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) to distinguish the PRKAG2 group from the HCM group. Data was assessed by R software, version 3.6.0 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing). P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics and ECG findings

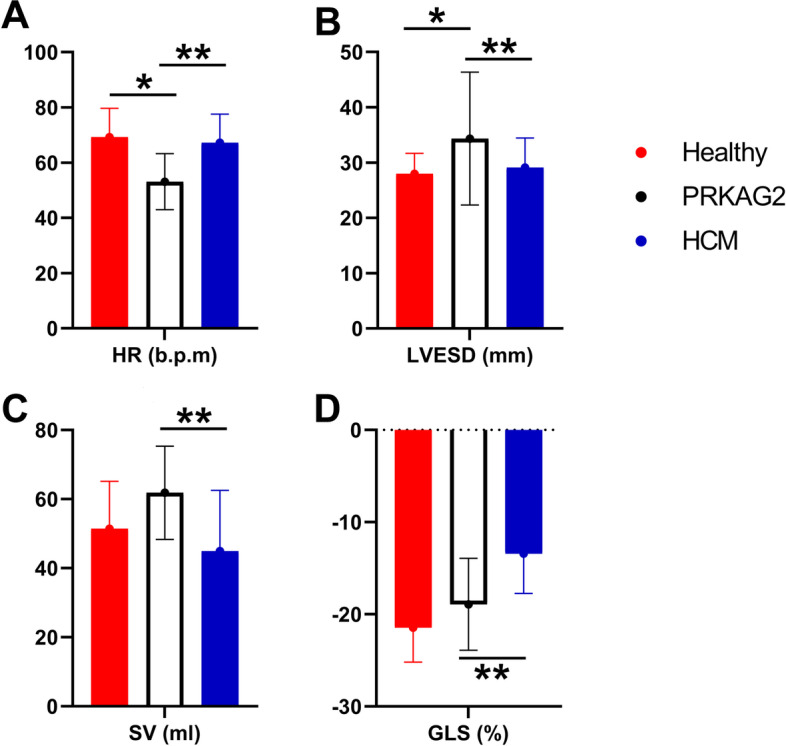

Clinical characteristics and HR were presented in Table 1. In general, we observed nine patients with PRKAG2 syndrome in six independent families (Supplementary Fig. 1). One patient (IV-1 in Family D) suffered from intellectual disability and somnambulism for more than ten years. Two patients showed LV preexcitation. Six patients presented LVH on ECG images, and one patient demonstrated abnormal Q waves. The heart rate (HR) of the PRKAG2 group was significantly lower than both the healthy group (53.11 ± 10.14 vs. 69.22 ± 10.48, P < 0.001) and the HCM group (53.11 ± 10.14 vs. 67.23 ± 10.32 bpm, P = 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Four in nine PRKAG2 patients and 17 in 41 HCM patients received beta blocker treatment (P = 1.000).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| Variable | PRKAG2 | Healthy | HCM | P1 | P2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 40.22 ± 14.01 | 42.04 ± 14.86 | 49.59 ± 12.75 | 0.719 | 0.056 |

| Male/female | 5/4 | 68/134 | 28/13 | 0.281 | 0.467 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.74 ± 0.20 | 1.65 ± 0.19 | 1.78 ± 0.21 | 0.199 | 0.627 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.80 ± 2.77 | 23.39 ± 3.88 | 25.45 ± 3.54 | 0.771 | 0.256 |

| HR, bpm | 53.11 ± 10.14 | 69.22 ± 10.48 | 67.23 ± 10.32 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

P1: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the healthy volunteers, P2: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the sarcomeric HCM group. BSA Body surface area, BMI Body mass index, HR heart rate

Fig. 2.

There were significant differences in HR, LVESD, SV, and GLS between PRKAG2 syndrome and sarcomeric HCM patients. HR and LVESD of PRKAG2 LVH also had significant differences compared with healthy volunteers. * refers to P < 0.05 between the PRKAG2 syndrome group and the healthy group. ** refers to P < 0.05 between the PRKAG2 syndrome group and the sarcomeric HCM group

Parameters of conventional echocardiography

Conventional echocardiographic parameters were shown in Table 2. The PRKAG2 group had similar interventricular septal thickness (IVS), posterior wall thickness (PWT), maximum wall thickness (MWT), and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) to the sarcomeric HCM group (P > 0.05). The LVWa of the PRAKG2 patients was significantly higher than that of the healthy volunteers (1.42 ± 0.52 vs. 1.05 ± 0.14 mm, P < 0.001), which was close to that of the HCM patients (1.42 ± 0.52 vs. 1.55 ± 0.63 mm, P = 0.551). RWT of the PRKAG2 group was significantly higher than that of the healthy group (0.48 ± 0.15 vs. 0.39 ± 0.07, P = 0.002). The left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) of the PRKAG2 group were significantly larger compared with the sarcomeric HCM group and the healthy volunteers (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). PRKAG2 syndrome patients demonstrated impaired LV diastolic function parameters, including A, e’ and E/e’. However, their LVEF remained in the normal range (PRKAG2 syndrome 62.67 ± 8.56 vs. healthy group 65.79 ± 6.88%, P = 0.189).

Table 2.

Conventional echocardiographic parameters

| Variable | PRKAG2 | Healthy | HCM | P1 | P2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AoD, mm | 31.89 ± 2.71 | 30.39 ± 3.45 | 32.76 ± 3.09 | 0.200 | 0.441 |

| LAD, mm | 42.56 ± 7.40 | 33.65 ± 3.88 | 44.59 ± 7.70 | < 0.001 | 0.475 |

| IVS, mm | 16.56 ± 6.31 | 8.84 ± 1.67 | 17.27 ± 5.51 | < 0.001 | 0.733 |

| PWT, mm | 11.89 ± 3.76 | 8.48 ± 1.38 | 11.73 ± 3.36 | < 0.001 | 0.585 |

| LVWa | 1.42 ± 0.52 | 1.05 ± 0.14 | 1.55 ± 0.63 | < 0.001 | 0.551 |

| MWT, mm | 21.89 ± 6.45 | 9.05 ± 1.63 | 21.48 ± 5.97 | < 0.001 | 0.853 |

| LVEDD, mm | 50.33 ± 8.38 | 43.64 ± 4.55 | 45.49 ± 5.38 | 0.005 | 0.107 |

| LVESD, mm | 34.44 ± 12.01 | 27.96 ± 3.71 | 29.12 ± 5.33 | < 0.001 | 0.046 |

| LVEF, % | 62.67 ± 8.56 | 65.79 ± 6.88 | 64.22 ± 7.39 | 0.189 | 0.581 |

| E, cm/s | 76.84 ± 19.76 | 81.81 ± 17.46 | 72.23 ± 20.66 | 0.408 | 0.553 |

| A, cm/s | 51.67 ± 10.84 | 64.13 ± 16.98 | 66.03 ± 25.29 | 0.030 | 0.107 |

| s’, cm/s | 6.67 ± 1.91 | 10.01 ± 2.42 | 7.40 ± 1.38 | < 0.001 | 0.186 |

| e', cm/s | 7.92 ± 2.38 | 12.04 ± 3.78 | 6.80 ± 1.96 | 0.001 | 0.208 |

| E/e' | 10.31 ± 4.10 | 7.34 ± 2.37 | 11.24 ± 4.45 | < 0.001 | 0.578 |

P1: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the healthy volunteers, P2: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the sarcomeric HCM group. AoD aortic dimension, LAD left atrial dimension, IVS interventricular septum thickness, PWT posterior wall thickness, LVWa left ventricular wall asymmetry, MWT maximum wall thickness, LVEDD left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, LVESD left ventricular end-systolic diameter, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction

Parameters of speckle tracking imaging

The results of the 3D STE analysis were shown in Table 3. EDV and ESV from 3D STE also enlarged in PRKAG2 syndrome (P < 0.05). The differences were not significant compared with the sarcomeric HCM group (P > 0.05). However, SV calculated from EDV and ESV in PRKAG2 syndrome was larger than that of sarcomeric HCM (61.83 ± 13.52 vs. 44.96 ± 17.53%, P = 0.020) (Fig. 2C). The value of GLS in PRKAG2 syndrome was significantly better than that of HCM (-18.92 ± 4.98 vs. -13.43 ± 4.30%, P = 0.004) and near the healthy level (-18.92 ± 4.98 vs. -21.45 ± 3.73%, P = 0.083) (Fig. 2D). In terms of dyssynchrony, SDI increased in the PRKAG2 group compared with the control group (5.83 ± 1.17 vs. 4.59 ± 1.56%, P = 0.033). However, there were no significant differences of SDI or SDII between the PRKAG2 group and the HCM group.

Table 3.

3D STE parameters

| Variable | PRKAG2 | Healthy | HCM | P1 | P2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDV, ml | 107.89 ± 34.79 | 81.16 ± 21.80 | 89.58 ± 32.80 | 0.002 | 0.183 |

| ESV, ml | 46.06 ± 25.80 | 29.72 ± 12.28 | 44.61 ± 21.57 | 0.001 | 0.874 |

| SV, ml | 61.83 ± 13.52 | 51.43 ± 13.73 | 44.96 ± 17.53 | 0.050 | 0.020 |

| EF, % | 59.78 ± 11.69 | 63.97 ± 8.51 | 50.97 ± 11.88 | 0.207 | 0.076 |

| GLS, % | -18.92 ± 4.98 | -21.45 ± 3.73 | -13.43 ± 4.30 | 0.083 | 0.004 |

| GCS, % | -29.27 ± 9.06 | -31.17 ± 6.93 | -23.99 ± 7.30 | 0.481 | 0.095 |

| SDI, % | 5.83 ± 1.17 | 4.59 ± 1.56 | 8.66 ± 5.12 | 0.033 | 0.098 |

| SDII, % | 11.70 ± 2.36 | 8.72 ± 5.85 | 12.27 ± 4.78 | 0.180 | 0.761 |

| Twist, ° | 12.67 ± 3.11 | 13.88 ± 8.39 | 14.25 ± 8.78 | 0.704 | 0.643 |

| Torsion, °/cm | 1.55 ± 0.44 | 1.89 ± 1.14 | 1.85 ± 1.12 | 0.433 | 0.491 |

P1: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the healthy volunteers; P2: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the sarcomeric HCM group. EDV end-diastolic volume, ESV end-systolic volume, SV stroke volume, EF ejection fraction, GLS global longitudinal strain, GCS global circumferential strain, SDI systolic timing deviation index, SDII systolic timing dispersion index

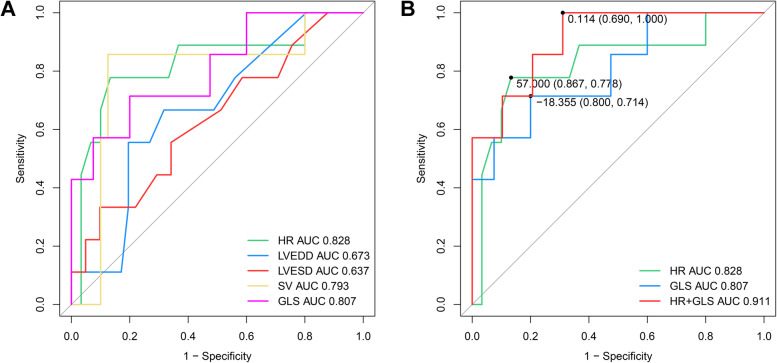

Parameters for differential diagnosis

The area under the curve (AUC) and the confidence interval of AUC from ROC analysis were demonstrated in Table 4 and Fig. 3A. Among them, the AUC of HR and GLS were the highest with the lower confidence limit > 0.6. We put HR and GLS into the Logistic regression test and got a new predictor of HR + GLS. The AUC for HR + GLS was 0.911 (0.803—1), which was higher than that of HR (0.828, 0.646—1) and GLS (0.807, 0.614—1) (Fig. 3B). For HR + GLS, the sensitivity and specificity of the best cut-off value (0.114) were 69.0% and 100%, respectively.

Table 4.

ROC curve analysis results

| Variable | AUC | 95% CI | Cut-off value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 0.828 | 0.646–1 | 57 | 0.867 | 0.778 |

| LVEDD | 0.673 | 0.487–0.86 | 50.5 | 0.805 | 0.556 |

| LVESD | 0.637 | 0.427–0.846 | 35.5 | 0.902 | 0.333 |

| SV | 0.793 | 0.581–1 | 58.79 | 0.875 | 0.857 |

| GLS | 0.807 | 0.614–1 | -18.355 | 0.800 | 0.714 |

| HR + GLS | 0.911 | 0.803–1 | 0.114 | 0.690 | 1.000 |

P1: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the healthy volunteers; P2: P values between the PRKAG2 group and the sarcomeric HCM group. HR heart rate, LVEDD left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, LVESD left ventricular end-systolic diameter, SV stroke volume, GLS global longitudinal strain

Fig. 3.

Comparison of ROC curve analysis for prediction of PRKAG2 syndrome in LVH patients. A The ROC curves are based on statistically significant parameters, including HR, LVEDD, LVESD, SV, and GLS. B The two parameters (HR and GLS) with the highest AUC were selected for Logistic regression analysis. We put the new predictor (HR + GLS) into ROC curve analysis and got the highest AUC of 0.911. The best cut-off value (0.114) sensitivity and specificity were 69.0% and 100%, respectively

Discussion

PRKAG2 syndrome is a progressive glycogen storage disease. It had been considered a part of HCM for several decades until 2001 when autosomal dominant inherited mutations in the PRKAG2 gene were first observed to be responsible for this syndrome [6]. PRKAG2 gene encodes the γ2 regulatory subunit of AMPK, enhancing glucose and lipids metabolism [9]. This rare disease is characterized by LVH, ventricular preexcitation, diverse arrhythmia, advanced heart failure, and sudden cardiac death. Almost 10% of PRKAG2 cases suffered from sudden death; more than 30% required pacemaker implantation [10]. Although PRKAG2 syndrome comprises less than one percent of unexplained LVH, the differential diagnosis is crucial because of its distinct natural history, poor prognosis, and active treatment strategies.

Echocardiography is a noninvasive, widely available, and first-line technique to identify and quantify LVH [11]. This study collected the parameters of conventional two-dimensional echocardiography, Doppler ultrasound, and 3D STE. We aimed to compare PRKA2G syndrome with healthy volunteers and sarcomeric HCM.

In literature, MWT of PRAKG2 syndrome is from 20 to 21 mm, which is similar to our measurements of 21.89 ± 6.45 mm [10, 12]. The RWT of PRKAG2 syndrome in this study was 0.48 ± 0.15, which reached the definition of concentric hypertrophy pattern (RWT > 0.42) [13]. These findings confirmed the concentric LVH pattern of PRKAG2 syndrome. However, we also observed asymmetric septal hypertrophy in our PRKAG2 patients (LVWa = 1.42 ± 0.52). This may reflect the diversity of PRKAG2 syndrome. Larger size studies are needed to find the exact ratio of hypertrophy patterns.

We evaluated LV diastolic function using parameters of Doppler echocardiography parameters (E, A, e’, E/e’). Most parameters indicated PRKAG2 LV diastolic dysfunction similar to sarcomeric HCM.

General HCM patients had worse GLS compared with healthy individuals [14]. Recently, STE has been reported to be a non-Doppler-oriented and angle-independent technique that helped detect different causes of LVH [15–17]. However, few articles focused on the STE parameters in PRKAG2 syndrome because of the low prevalence.

Interestingly, we observed preserved GLS and GCS in our PRKAG2 patients compared with healthy volunteers (GLS -18.92 ± 4.98 vs. -21.45 ± 3.73%, P = 0.083; GCS -29.27 ± 9.06 vs. -31.17 ± 6.93%, P = 0.481). However, in a recent study using STE, the GLS and GCS strains of PRKAG2 syndrome decreased as -13 ± 4.8% and -16.1 ± 4.4%, respectively [12]. Healthy controls were not involved in that study. Different echocardiographic systems, software, operators, and pathophysiological heterogeneity might contribute to the discrepancy. In our study, LVEF and EF from 3D STE also evidenced the uncompromised PRKAG2 LV systolic function.

To distinguish PRKAG2 syndrome from HCM, we combined HR and GLS for ROC curve analysis. For the best cut-off value (0.114), the sensitivity and the specificity were 69% and 100%, respectively. The progression of gene sequencing provides opportunities to identify patients with PRKAG2 syndrome from HCM patients. However, gene sequencing is limited by clinical availability and economic factors. Clinically, the suspicion is based on “red flags”, which traditionally include young age, unexplained LVH, bradycardia, ventricular preexcitation, and high-grade conduction disease [1]. LVH has been reported as the most common clinical phenotype of PRKAG2 syndrome [2]. Only one-third of PRKAG2 patients demonstrate preexcitation [10]. For PRKAG2 patients whose phenocopies mimic HCM, preserved GLS may also be used as “red flags”. The AUC for HR was 0.828 (95% CI, 0.646—1); the best cut-off value’s sensitivity and specificity (57 bpm) were 86.7% and 77.8%, respectively. When GLS was incorporated, the specificity increased to 100%, with the sensitivity decreasing to 69%. ECG examination has the potential for screening PRKAG2 syndrome. 3D STE can also be performed for more evidence of PRKAG2 syndrome.

Limitations

The studied population is a sample of PRKAG2 syndrome with LVH. However, some PRKAG2 patients do not present LVH. The 3D STE characteristics of those patients are not investigated in this study. Another limitation is that the number of PRKAG patients enrolled was small and all the patients were from the same hospital.

Conclusions

In conclusion, PRKAG2 patients present deteriorated LV diastolic function and preserved LV systolic function compared with healthy subjects. Bradycardia and preserved GLS have the potential to distinguish PRKAG2 syndrome from HCM with high specificity. Our study demonstrates that ECG and 3D STE are useful for identifying patients with PRKAG2 syndrome, which may help clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Family pedigrees of PRKAG2 syndrome.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- LVH

Left ventricular hypertrophy

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- GLS

Global longitudinal strain

- GCS

Global circumstantial strain

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

Authors’ contributions

LT, XL, NZ, and YJ participated in data collection and 3D STE analysis. CP and XS reviewed the echocardiography examinations. LT and XL performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved of the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants 81671685 from National Natural Science Foundation of China and grants 17411954400 from the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University (Lot Number: 2016‐16B). All patients were enrolled after the signing of the informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lu Tang and Xuejie Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Porto AG, Brun F, Severini GM, Losurdo P, Fabris E, Taylor M, et al. Clinical Spectrum of PRKAG2 Syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e3121. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy RT, Mogensen J, McGarry K, Bahl A, Evans A, Osman E, et al. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase disease mimicks hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: natural history. J AM COLL CARDIOL. 2005;5:922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf CM, Arad M, Ahmad F, Sanbe A, Bernstein S, Toka O, et al. Reversibility of PRKAG2 glycogen-storage cardiomyopathy and electrophysiological manifestations. Circulation. 2008;117:144–154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.726752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gollob MH, Seger JJ, Gollob TN, Tapscott T, Gonzales O, Bachinski L, et al. Novel PRKAG2 mutation responsible for the genetic syndrome of ventricular preexcitation and conduction system disease with childhood onset and absence of cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2001;104:3030–3033. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.102111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arad M, Benson DW, Perez-Atayde AR, McKenna WJ, Sparks EA, Kanter RJ, et al. Constitutively active AMP kinase mutations cause glycogen storage disease mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J CLIN INVEST. 2002;109:357–362. doi: 10.1172/JCI0214571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gollob MH, Green MS, Tang AS, Gollob T, Karibe A, Ali HA, et al. Identification of a gene responsible for familial Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1823–1831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106143442403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Kayvanpour E, Tugrul OF, Lai A, Amr A, Haas J, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with sarcomere mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a meta-analysis on 7675 individuals. CLIN RES CARDIOL. 2018;107:30–41. doi: 10.1007/s00392-017-1155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vlachaki WJ, Robb JL, Cruz AM, Malhi A, Weightman PP, Ashford MLJ, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator A-769662 increases intracellular calcium and ATP release from astrocytes in an AMPK-independent manner. DIABETES OBES METAB. 2017;19:997–1005. doi: 10.1111/dom.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Sainz A, Dominguez F, Lopes LR, Ochoa JP, Barriales-Villa R, Climent V, et al. Clinical Features and Natural History of PRKAG2 Variant Cardiac Glycogenosis. J AM COLL CARDIOL. 2020;76:186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marwick TH, Gillebert TC, Aurigemma G, Chirinos J, Derumeaux G, Galderisi M, et al. Recommendations on the Use of Echocardiography in Adult Hypertension: A Report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:727–754. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pena J, Santos WC, Siqueira M, Sampario IH, Moura ICG, Sternick EB. Glycogen storage cardiomyopathy (PRKAG2): diagnostic findings of standard and advanced echocardiography techniques. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22(7):800–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7:79–108. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardim N, Galderisi M, Edvardsen T, Plein S, Popescu BA, D’Andrea A, et al. Role of multimodality cardiac imaging in the management of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an expert consensus of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging Endorsed by the Saudi Heart Association. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:280. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Militaru S, Jurcut R, Adam R, Rosca M, Ginghina C, Popescu BA. Echocardiographic features of Fabry cardiomyopathy-Comparison with hypertrophy-matched sarcomeric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography. 2019;36:2041–2049. doi: 10.1111/echo.14508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnell F, Matelot D, Daudin M, Kervio G, Mabo P, Carre F, et al. Mechanical Dispersion by Strain Echocardiography: A Novel Tool to Diagnose Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Athletes. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnell F, Donal E, Bernard-Brunet A, Reynaud A, Wilson MG, Thebault C, et al. Strain analysis during exercise in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: impact of etiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Family pedigrees of PRKAG2 syndrome.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.