Abstract

Background and Purpose:

The general cardiovascular Framingham risk score (FRS) identifies adults at increased risk for stroke. We tested the hypothesis that baseline FRS is associated with the presence of postmortem cerebrovascular disease (CVD) pathologies.

Methods:

We studied the brains of 1672 older decedents with baseline FRS and measured CVD pathologies including macroinfarcts, microinfarcts, atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. We employed a series of logistic regressions to examine the association of baseline FRS with each of the five CVD pathologies.

Results:

Average age at baseline was 80.5±7.0 years and average age at death was 89.2±6.7 years. A higher baseline FRS was associated with higher odds of macroinfarcts (OR=1.10, 95%CI: 1.07–1.13, p<0.001), microinfarcts (OR=1.04, 95%CI: 1.01–1.07, p=0.009), atherosclerosis (OR=1.07, 95%CI: 1.04–1.11, p<0.001), and arteriolosclerosis (OR=1.04, 95%CI: 1.01–1.07, p=0.005). C-statistics for these models ranged from 0.537 to 0.595 indicating low accuracy for predicting CVD pathologies. FRS was not associated with the presence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Conclusions:

A higher FRS score in older adults is associated with higher odds of some, but not all, CVD pathologies, with low discrimination at the individual level. Further work is needed to develop a more robust risk score to identify adults at risk for accumulating CVD pathologies.

Keywords: Risk factors, Postmortem changes, Autopsy, Cerebral infarction, Atherosclerosis, Arteriolosclerosis, Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

INTRODUCTION

Acute stroke can have devastating clinical consequences and affect about 10% of Americans 60 years or older1. Public health efforts to reduce stroke have focused on reducing risk factors for cerebrovascular disease (CVD). CVD risk factors cluster and interact multiplicatively to increase the risk of stroke highlighting the need for clinical risk scores for stroke. Risk scores are employed to identify older adults who might benefit from aggressive early treatments of CVD risk factors to prevent the occurrence of strokes.

There is increased recognition that CVD pathologies develop over many years before manifesting clinical symptoms of stroke 2. Moreover, brain imaging studies suggest that many older adults show evidence of subclinical CVD pathologies such as infarcts without any prior history of clinical stroke 3. Additionally, subclinical CVD pathology is not benign and may make important contributions to late-life cognitive 4 and motor decline 5. Thus, preventing the accumulation of CVD pathologies is crucial to maintain independent living in older adults 6.

While conventional brain MRI imaging can identify macroinfarcts, they cannot identify adults with evidence of microvascular pathologies. Microvascular pathologies including microinfarcts, arteriolosclerosis or cerebral amyloid angiopathy can only be identified via postmortem microscopic exam of brain tissues. Thus, there is a particular need for risk scores capable of identifying older adults at risk for microvascular pathologies which commonly accumulate in older brains.

There is a paucity of data about whether currently available risk scores for clinical stroke, like the Framingham risk score, can identify adults at risk for CVD pathologies, especially among the oldest old. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted this study.

METHODS

Participants

The study participants came from one of three ongoing community-based longitudinal studies of aging directed by the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center 7. The Religious Orders Study (ROS) began recruiting nuns, priests, and brothers across the United States in 1994. In 1997, the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP) began recruiting older adults from retirement centers and subsidized housings across the greater Chicago metropolitan area. Older adults without known dementia who consent to annual testing and autopsy at the time of death are eligible for inclusion in these studies. Since 2004, the Minority Aging Research Study (MARS) has recruited participants who are exclusively African Americans8. MARS participants are recruited from a variety of settings including churches, subsidized housings, and retirement communities. Unlike ROS and MAP, MARS participants were not required to consent for brain donation as a requisite to join the study given their sensitivity to brain donation due, at least in part, to a historical legacy of exploitation and abuse in medical research among African Americans. However, investigators proposed brain donation as an option to the MARS participants after establishing relationships with them based on trust and respect. Yet, all participants across the three studies consent to annual clinical evaluation, and all studies employ common clinical and postmortem data collection methods performed by the same staff, a strategy that facilitates joint analysis 7. A Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved each study.

From 1994 through February 2020, 872 ROS participants with complete baseline data had died, 802 had undergone autopsy and 788 had complete autopsy data at the time of these analyses. In MAP, 891 of 1079 decedents had undergone autopsy, and 856 had complete autopsy data. In MARS, 35 of 61 decedents who agreed to autopsy had undergone autopsy, and 33 had complete autopsy data. From 1677 participants with available autopsy, vascular risk factor data was missing in four MAP and one MARS participants. Therefore, 1672 participants comprised the analytic sample. De-identified data, including those used in these analyses, may be requested via submitting an application through the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center Research Resource Sharing Hub at www.radc.rush.edu.

Assessment of the Framingham risk score

Cardiovascular risk burden was quantified using the general cardiovascular Framingham risk score (FRS) which is calculated separately for women and men and has 5 components: a) age, b) body mass index (BMI), c) systolic blood pressure (SBP), d) smoking, and e) diabetes mellitus9. SBP is scored differently for individuals with or without medical treatment for hypertension 9.

At baseline assessment, medical conditions and cardiovascular risk factors, including history of smoking and diabetes mellitus were documented. Height and weight were measured for calculating BMI. All medications were inspected and names and dosages were recorded and coded using Medi-Span Drug Data Base System 10. Standing and sitting SBP was measured by trained research assistants using automated sphygmomanometers, and an average SBP was calculated as described previously 11.

Assessment of postmortem cerebrovascular disease pathologies

A structured brain autopsy, as described in prior publications, was performed by staff blinded to clinical data collected prior to death 7,12. The brain was cut into slabs, and tissue blocks were prepared from the slabs of predefined brain regions for collection of histopathologic indices.

Macroinfarcts:

The main objective of the study was to examine the association between baseline FRS and CVD pathologies. Thus, as we have done in prior postmortem studies, we included only chronic infarcts that would be more reflective of the cumulative effects of the vascular risk burden 12,13. Slabs were inspected with the naked eye for the presence of macroinfarcts, and suspected lesions were confirmed microscopically 14. For these analyses we summarized macroinfarcts as a dichotomous (presence/absence) or a trichotomous (0, 1, 2 or more) ordinal variable. We also categorized macroinfarcts by location into cortical and subcortical ones that were not mutually exclusive, and a participant could have macroinfarcts in both locations.

Microinfarcts:

Microinfarcts are not visible to the naked eye and can only be identified under microscopy. Sections were prepared from tissue blocks of 9 brain regions in 1 hemisphere, and were examined for microinfarcts. Six cortical brain regions (frontal, temporal, entorhinal, hippocampal, parietal, and anterior cingulate), two subcortical regions (anterior basal ganglia and thalamus), and the midbrain were examined. As noted above for macroinfarcts, we only examined chronic microinfarcts in these analyses. Microinfarcts were summarized as a dichotomous (presence/absence) or trichotomous (0, 1, 2 or more) ordinal variable. Following macroinfarcts, microinfarcts were also categorized by location into cortical and subcortical ones.

Atherosclerosis:

The vessels of the circle of Willis at the base of the brain (vertebral, basilar, posterior, middle, and anterior cerebral arteries) were assessed for atherosclerosis using a semiquantitative scale (none to severe), as described previously 15. For these analyses, we dichotomized the absence of atherosclerosis (none/mild) or its presence (moderate/severe) as done in prior publications 16.

Arteriolosclerosis:

Arteriolosclerosis was based on the assessment of small arterioles of the anterior basal ganglia. A semi-quantitative scoring scale was used to assess concentric hyaline thickening and narrowing of the arterioles 15. Like atherosclerosis, we constructed a dichotomous variable for the presence or absence of moderate/severe arteriolosclerosis 16.

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA):

CAA was based on amyloid-β immunostaining of meningeal and parenchymal vessels in sections from four brain regions (frontal, temporal, angular, and calcarine cortices). CAA was scaled semi-quantitatively in each brain region and the average score for the four regions was calculated. From this continuous CAA score, a semi-quantitative CAA scale has also been developed 15. For these analyses, we constructed a dichotomous variable for the presence or absence of moderate/severe CAA, as done in prior publications 16.

Assessment of covariates

At the baseline evaluation, sex and years of education were assessed by self-report. History of vascular diseases, including stroke and heart attack, was also documented through self-report.

Statistical analyses

We used t-tests to examine the bivariate associations of FRS with CVD pathologies, and Spearman correlation coefficient to examine bivariate association of education with FRS. In our primary analyses, we used logistic regression models to examine the association of the FRS with each of the five CVD pathologies. In secondary analyses, we first examined whether the associations were confounded or modified by the time interval between the FRS assessment and the time of death or the number of years of formal education. Second, we excluded participants with a history of stroke or myocardial infarction to examine whether the association between FRS and the CVD pathologies were driven by these subsets of participants. We used SAS version 9.4 for the analyses, and set 0.05 as the cut-point to reject the null hypotheses.

RESULTS

Characteristics of study participants.

Clinical Characteristics:

There were 1672 participants and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. On average, participants were 80 years old at baseline and were followed for about 9 years [8.6 years (SD=5.3)] before death. Hypertension was the most common risk factor, and affected approximately half of the participants at baseline.

Table 1:

Participants’ characteristics (N=1672).

| Measure | Mean(SD) or n(%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age at baseline (years), mean (SD) | 80.5(7.0) |

| Age at death (years), mean (SD) | 89.2(6.7) |

| Female, n(%) | 1126(67) |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 16.2(3.6) |

| Clinical characteristics at baseline | |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 26.8(5.1) |

| Hypertension, n(%) | 790(47) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD) | 135.8(17.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD) | 72.3(10.8) |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n(%) | 211(13) |

| Antihypertensive medication use, n(%) | 1077(64) |

| Smoking history, n(%) | 527(32) |

| History of stroke, n(%) | 160(10) |

| History of myocardial infarction, n(%) | 222(13) |

| Postmortem indices of cerebrovascular pathologies | |

| Macroinfarcts (1 or more), n(%) | 591(35) |

| Cortical macroinfarcts (1 or more), n(%) | 222(13) |

| Subcortical macroinfarcts (1 or more), n(%) | 457(27) |

| Microinfarcts (1 or more), n(%) | 504(30) |

| Cortical microinfarcts (1 or more), n(%) | 317(19) |

| Subcortical microinfarcts (1 or more), n(%) | 246(15) |

| Atherosclerosis | |

| None or mild, n(%) | 1123(68) |

| Moderate or severe, n(%) | 541(33) |

| Arteriolosclerosis | |

| None or mild, n(%) | 1119(67) |

| Moderate or severe, n(%) | 541(33) |

| Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy | |

| None or mild, n(%) | 1050(64) |

| Moderate or severe, n(%) | 582(36) |

Postmortem Indices:

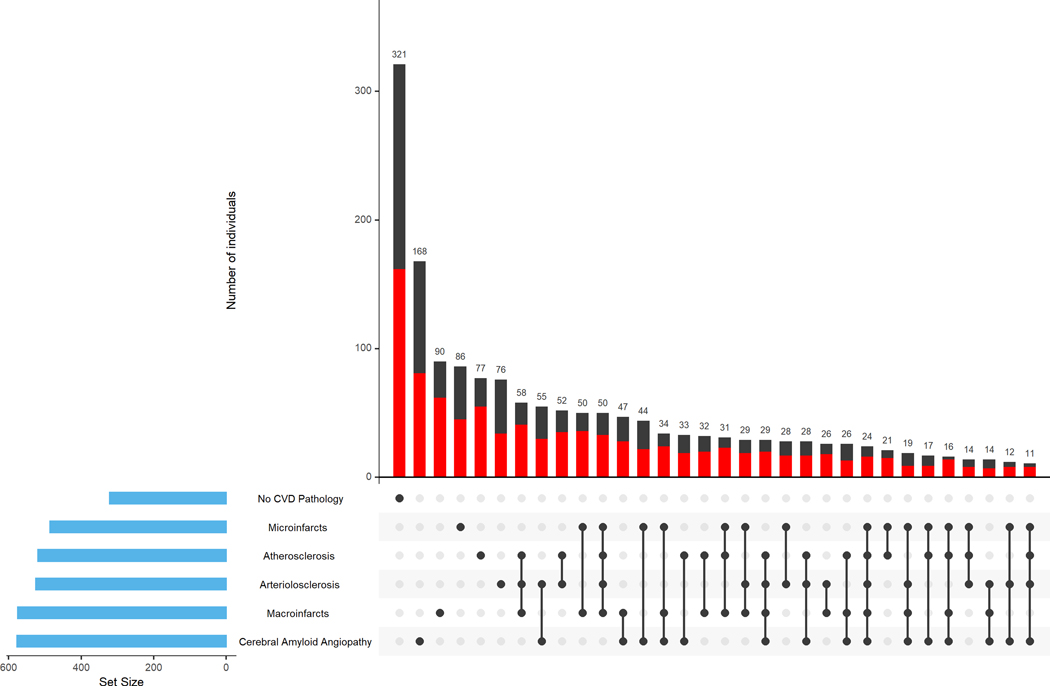

The average postmortem interval was 9.6 (SD=9.0) hours. Figure 1 highlights the heterogeneity of cerebrovascular disease pathologies accumulating in aging brains. The majority of participants had one or more cerebrovascular pathologies (80%) with 30% having one vascular pathology, and about 50% of the participants having more than one vascular pathology (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Burden of cerebrovascular disease pathologies in the brain.

The figure highlights the heterogeneity of cerebrovascular disease pathologies accumulating in aging brains. The bar chart in the lower left corner shows the frequency of each of the CVD pathologies and participants without any of the CVD pathologies. Connected black dots on the x-axis indicate the most frequent combinations of CVD pathologies. The histograms in the main panel show the frequencies of the combinations of CVD pathologies in the participants with high (red) vs. low (black) Framingham risk score (FRS) [stratified based on the median FRS score that was 19], ordered by their frequency. The high FRS was defined as scores equal or more than the median compared to low FRS that was defined as scores less than the median. The height of each bar corresponds to the number of participants with each individual or combination of CVD pathologies. Cerebrovascular disease pathologies occurred alone in a minority of participants (30%, 497 of 1672) and combinations of cerebrovascular pathologies occurred in about half of the participants (51%, 854 of 1672 with 2 or more CVD pathologies).

Baseline Framingham risk score and macroinfarcts

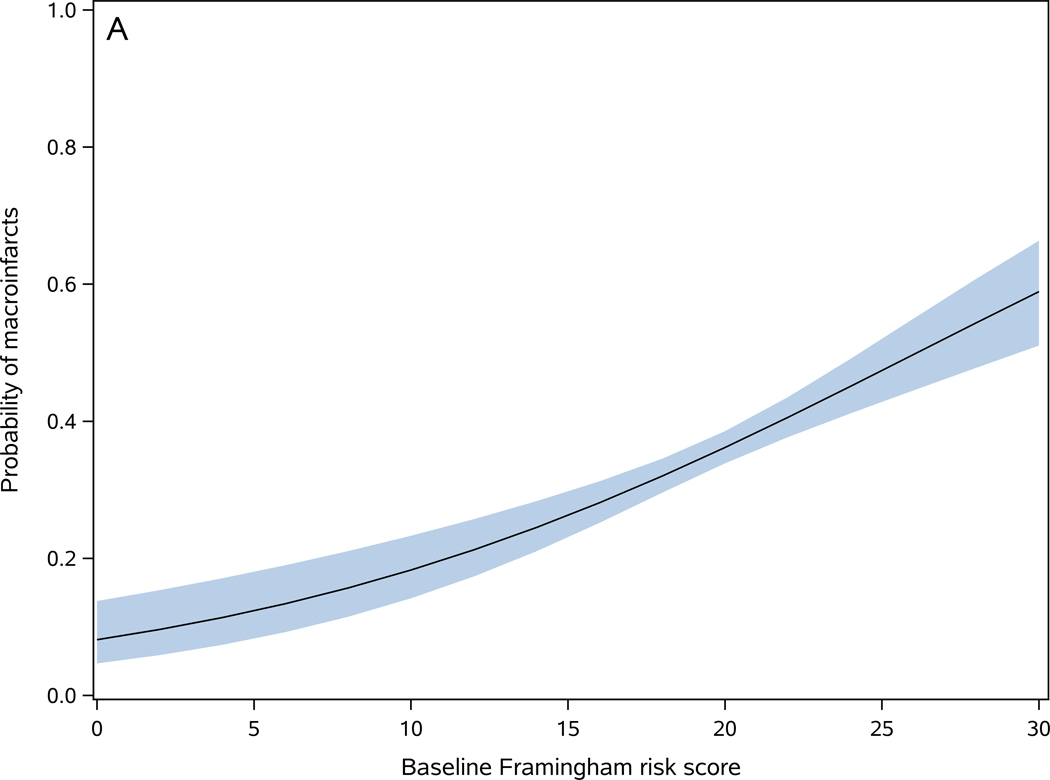

On average, the baseline FRS score was 19.5 (SD=3.5). FRS was higher in participants with macroinfarcts [present (20.2±3.3) versus absent (19.1±3.5)] (t1670=6.33, p<0.001). In a logistic regression, a 1-point increase in the baseline FRS was associated with a 10% increase in the odds of macroinfarcts (OR=1.10, 95%CI: 1.07–1.13, p <0.001) (Figure 2-A). The c-statistics for this model was 0.595, indicating low discrimination in predicting macroinfarcts for an individual. To examine whether a more granular assessment of macroinfarct could change its association with FRS or improve its prediction discrimination, we replaced the dichotomous macroinfarcts measure with a trichotomous measure [no macroinfarct (n=1081), 1 macroinfarct (n=308), and 2 or more macroinfarcts (n=283)]. In an ordinal logistic regression model, a 1-point increase in FRS score was associated with a 9% increase in the odds of more macroinfarcts (OR=1.09, 95%CI: 1.06–1.12, p<0.001), and the c statistics of the model was 0.580. These findings suggest that a more granular assessment of macroinfarct does not improve its prediction by FRS.

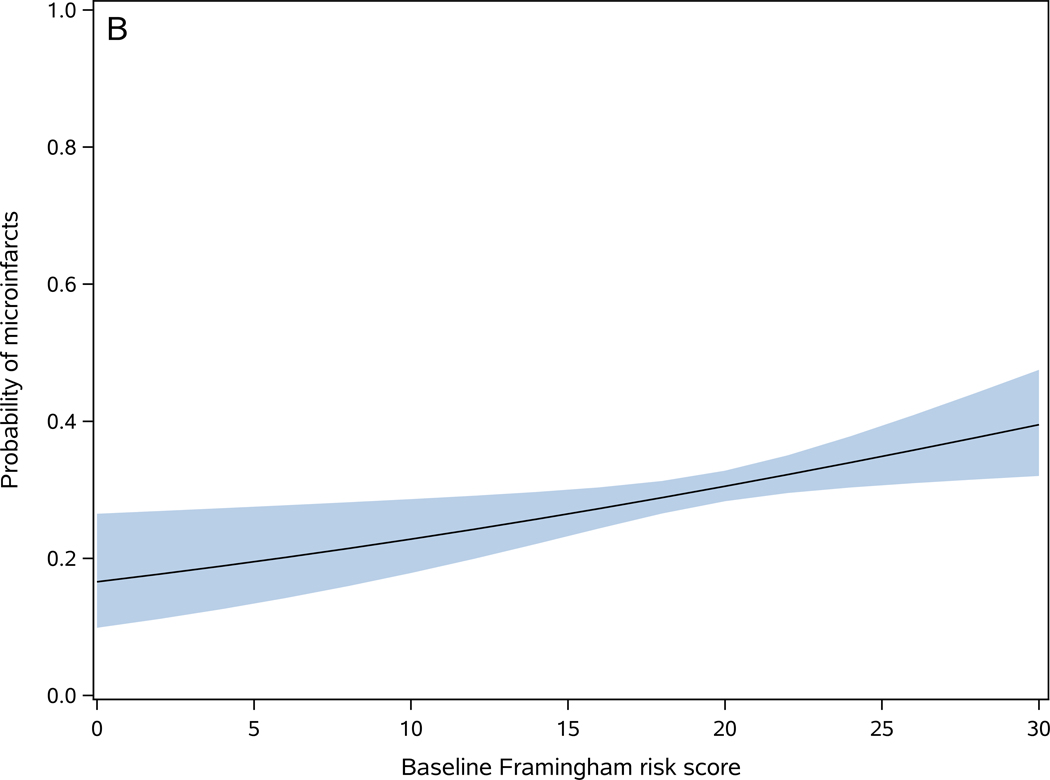

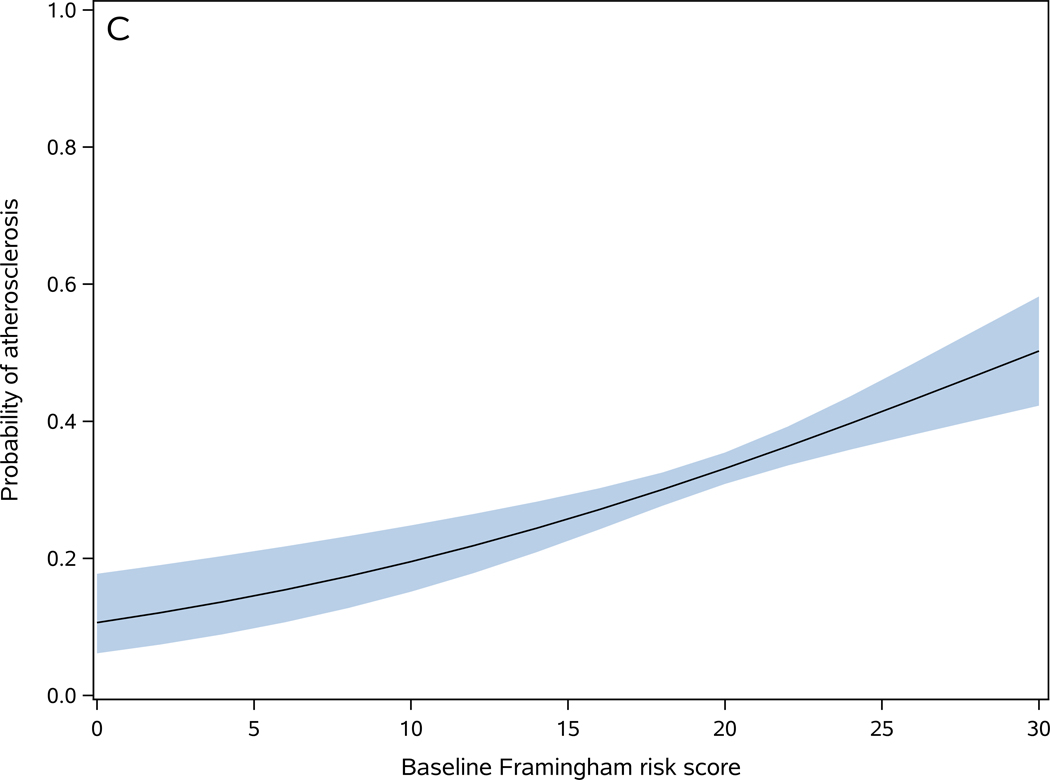

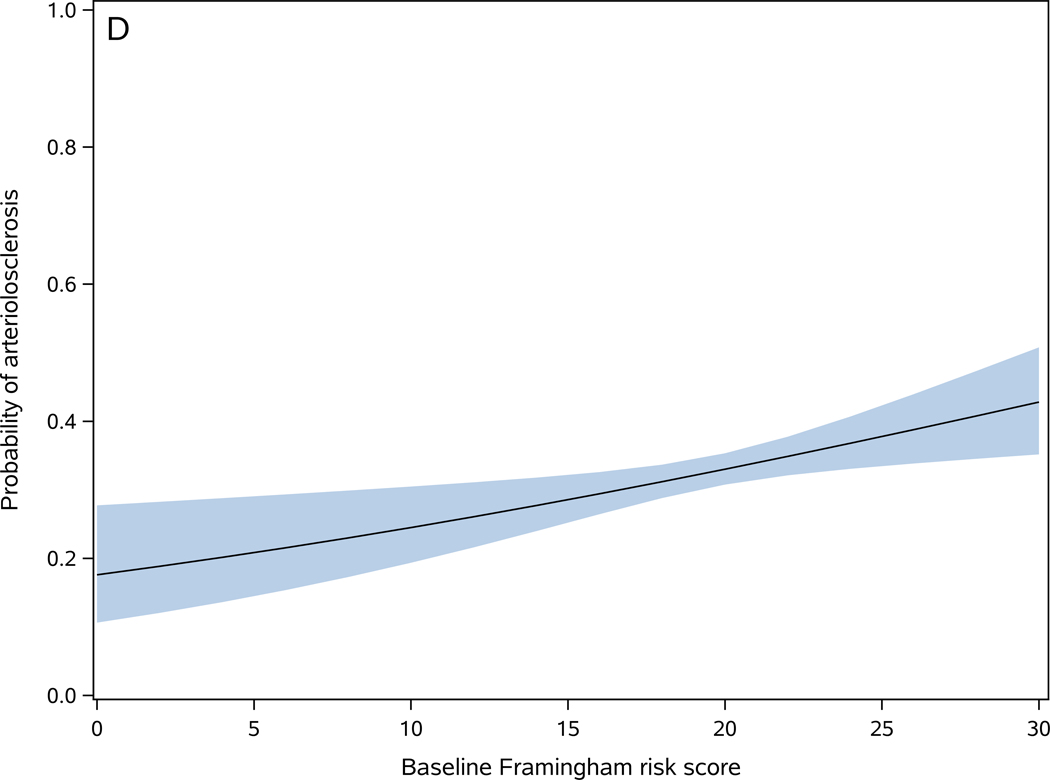

Figure 2. Baseline Framingham risk score is associated with cerebrovascular disease pathologies.

Probability of one or more macroinfarcts (A), microinfarcts (B), moderate to severe atherosclerosis (C), and moderate to severe arteriolosclerosis (D) as a function of baseline Framingham risk score. The shaded area represents 95% confidence interval of the probabilities.

Location of Infarcts:

In further analyses, we examined the association of FRS with the location of macroinfarcts (cortical versus subcortical, Table 1). In logistic regressions, a 1-point increase in the baseline FRS was associated with a 10% increase in the odds of subcortical infarcts (OR=1.10, 95%CI: 1.07–1.14, p<0.001), but with only 4% increase in the odds of cortical infarcts (OR=1.04, 95%CI: 1.00–1.08, p=0.044). .

Secondary Analyses

We examined a series of analyses to determine whether the association between FRS and macroinfarcts was attenuated by common clinical covariates or when subsets of individuals with a history of clinical stroke or myocardial infarctions were excluded.

We examined if the time interval between FRS assessment and death confounded the association of FRS and macroinfarcts. On average, participants’ FRS was assessed 8.6 (SD=5.3) years before death. Adding a term for the time interval between the FRS assessment and death did not attenuate the association of FRS with macroinfarcts (Table 2, Model 1). Next we added to the previous model an interaction term between the FRS score and the time interval between the time of FRS assessment and death. The association between the FRS score and the presence of macroinfarcts did not vary with the time interval between FRS assessment and the time of death (Table 2, Model 2).

Table 2.

Association of the Framingham risk score at baseline with postmortem cerebrovascular disease (CVD) pathologies (N=1672).

| Model | Macroinfarcts | Microinfarcts | Atherosclerosis | Arteriolosclerosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 1.10 (1.07–1.13), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07), 0.009 | 1.07 (1.04–1.11), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.07), 0.005 |

| 1 | 1.10 (1.07–1.13), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.07), 0.008 | 1.08 (1.04–1.11), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.07), 0.005 |

| 2 | 1.10 (1.07–1.13), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.07), 0.007 | 1.07 (1.04–1.11), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.07), 0.005 |

| 3 | 1.09 (1.06–1.13), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.07), 0.020 | 1.07 (1.04–1.11), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.07), 0.009 |

| 4 | 1.10 (1.06–1.13), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.08), 0.009 | 1.09 (1.05–1.12), <0.001 | 1.05 (1.02 – 1.08), 0.004 |

| 5 | 1.09 (1.06–1.13), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.00 – 1.07), 0.033 | 1.08 (1.04–1.11), <0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 – 1.08), 0.009 |

Each cell shows the odds ratios (95% confidence interval) and p-values for the association of FRS and a different CVD pathology derived from a logistic regression model. For each CVD pathology, five models examined whether the association of the FRS with the CVD pathology in our primary models (Reference Model) was attenuated by additional terms or by excluding subsets of participants with a history of CVD. Model 1 included terms for FRS and the time (years) from the FRS assessment to the time of death. Model 2 added an interaction term (FRS × time interval (years) from assessment to death) to the model 1 terms. Model 3 included terms for FRS and education (years). Model 4 included a term for FRS but excluded participants with a history of stroke (n=221). Model 5 included a term for FRS but excluded participants with a history of myocardial infarction (n=224).

Education is not included in the calculation of the FRS score while a lower level of education is a risk factor for clinical stroke 17. In our study, education was inversely correlated with the FRS score (rs = −0.11, p<0.001). Therefore, we examined if education attenuated the association between FRS and macroinfarcts. Adjustment for education did not change the association between FRS and macroinfarcts (Table 2, Model 3). Finally, we examined whether the association between FRS and macroinfarcts was driven by participants with a history of stroke or myocardial infarction. However, excluding participants with a history of stroke or myocardial infarction did not attenuate the association of FRS and macroinfarcts (Table 2, Models 4–5).

Baseline Framingham risk score and microinfarcts

FRS was higher in participants with microinfarcts [present (19.8±3.3) versus absent (19.3±3.6)] (t1670=2.61, p=0.009). In a logistic regression, a 1-point increase in the baseline FRS was associated with 4% increase in the odds of microinfarcts (OR=1.04, 95%CI: 1.01–1.07, p=0.009) (Figure 2-B). The c-statistics for this model was 0.542, indicating poor discrimination in predicting microinfarcts for an individual. To examine whether a more granular assessment of microinfarct could change its association with FRS or improve its prediction discrimination, we replaced the dichotomous microinfarcts measure with a trichotomous measure [no microinfarct (n=1168), 1 microinfarct (n=299), and 2 or more microinfarcts (n=205)]. In an ordinal logistic regression model, a 1-point increase in FRS score was associated with an 4% increase in the odds of more microinfarcts (OR=1.04, 95%CI: 1.01–1.07, p=0.008), and the c statistics of the model was 0.540. These findings suggest that a more granular assessment of microinfarct does not improve its prediction by FRS.

The same as macroinfarcts, we examined the association of FRS with subcortical vs. cortical microinfarcts. FRS was associated with subcortical microinfarcts (OR=1.06, 95%CI: 1.02–1.10, p=0.004), but not cortical ones (OR=1.01, 95%CI: 0.97–1.04, p=0.625).

Secondary Analyses

The association of FRS with microinfarcts neither was changed through adjustment for nor was modified by the time interval between FRS assessment and time of death (Table 2, Models 1–2). The association between FRS and microinfarcts did not change after adjustment for education (Table 2, Model 3) or after exclusion of participants with a history of stroke or myocardial infarction (Table 2, Models 4–5).

Baseline Framingham risk score and the presence of cerebrovascular disease pathologies of large and small cerebral blood vessels

Atherosclerosis:

Baseline FRS score was higher in participants with postmortem evidence of atherosclerosis [present (20.1±3.2) versus absent (19.2±3.6)] (t1662=4.77, p<0.001). In a logistic regression model, a 1-point increase in baseline FRS score was associated with 7% increase in the odds of atherosclerosis (OR=1.07, 95%CI: 1.04–1.11, p<0.001) (Figure 2-C). The c-statistics for this model was 0.577, indicating low discrimination for predicting atherosclerosis in an individual participant 18.

Secondary Analyses

The association of FRS with atherosclerosis did not change after adjustment for the time interval between FRS assessment and time of death (Table 2, Models 1–2) or education (Table 2, Model 3), or after exclusion of participants with a history of stroke or myocardial infarction (Table 2, Models 4–5).

Arteriolosclerosis:

Baseline FRS score was higher in participants with postmortem evidence of arteriolosclerosis [present (19.8±3.4) versus absent (19.3±3.5)] (t1658=2.80, p=0.005). In a logistic regression model, a 1-point higher baseline FRS score was associated with 3% higher odds of arteriolosclerosis (OR=1.04, 95%CI: 1.01–1.07, p=0.005) (Figure 2-D). However, the c-statistics of the model was 0.537, indicating poor discrimination for predicting arteriolosclerosis in an individual participant 18.

Secondary Analyses

The association of FRS with arteriolosclerosis did not change after adjustment for the time interval between FRS assessment and time of death (Table 2, Models 1–2) or education (Table 2, Model 3), or after exclusion of participants with a history of stroke or myocardial infarction (Table 2, Models 4–5).

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy:

Baseline FRS score was similar in participants with and without the presence of CAA (t1630=1.19, p=0.233). In a logistic regression model, baseline FRS score was not associated with the presence of CAA (OR=0.98, 95%CI: 0.95–1.01, p=0.232).

DISCUSSION

The FRS has been used in many clinical studies to identify adults with an increased risk of stroke. Examining data from approximately 1700 older adults, we found that a higher baseline FRS was associated with postmortem evidence of macroinfarcts, microinfarcts, atherosclerosis, and arteriolosclerosis, but not CAA. While these novel findings are encouraging, our analysis suggests that FRS showed low discrimination for predicting the presence of postmortem CVD pathologies in an individual adult. These data suggest that the FRS, in its current form, has limited clinical utility to identify adults at risk for the accumulation of postmortem CVD pathologies. Further studies are needed to develop a more robust risk score for identifying older adults at risk for accumulating CVD pathologies. Moreover, given the varied types of CVD pathologies several risk scores may be needed to facilitate targeted interventions to prevent specific CVD pathologies, e.g. macroinfarcts versus microvascular pathologies.

Current guidelines recommend that physicians use vascular risk scores to gauge an individual’s risk for major cardiovascular events 19. Risk scores such as the FRS were developed to identify risk for the occurrence of major vascular events such as myocardial infarction20. Their utility has been extended for identifying adults at risk for stroke 21. However, these risk scores were not designed for predicting the presence of postmortem CVD pathologies that are commonly associated with late-life cognitive and motor decline 22–25. Moreover, they were developed and examined in prediction of vascular events in younger populations. Consequently, it was not known to what extent the FRS was associated with postmortem indices of CVD pathologies in older brains 11,26,27.

The current study provides novel data about the association of FRS and CVD pathologies that accumulate in older adults. The finding that the baseline FRS was associated with macroinfarcts and atherosclerosis validates prior epidemiological studies reporting the association of FRS with clinical stroke 21 and with carotid intima media thickness 28. These current findings are encouraging and suggest that FRS might identify adults at risk both for clinical stroke and accumulating CVD pathologies. However, further examination of the models in the current study suggests that FRS may be of limited clinical utility as FRS showed limited discriminative ability in predicting older adults at risk of CVD pathologies. The C statistics of the current study models including FRS for predicting CVD pathologies were 0.54 – 0.60, which were less than 0.84 reported by previous studies for models predicting clinical stroke 9. These results highlight the need for further work to develop a more robust risk score for CVD pathologies.

The current study identified additional important limitations of the FRS for risk stratification of CVD pathologies. Conventional brain imaging cannot identify various microvascular pathologies that commonly occur i.e. microinfarcts, arteriolosclerosis and CAA. Examining postmortem brain pathologies showed that FRS had lower discriminative ability in predicting indices of microvascular pathologies including microinfarcts and arteriolosclerosis than predicting macroinfarcts, and FRS was not associated with CAA. These findings, which have been suggested by some prior studies 27,29–31, underscore the need for more robust CVD pathologies risk scores.

To develop a more robust risk score to identify older adults at risk for CVD pathologies, it will likely be necessary to add additional factors to the current FRS. Executive cognitive dysfunction can be one of the variables; previous studies have shown it to be a risk factor for clinical stroke 32 and to be related to the vascular brain pathologies33. In prior work, we have shown that parkinsonism, a motor phenotype, is strongly associated with CVD pathologies 25. Psychological variables like purpose in life 34 have also been shown to be associated with vascular brain pathologies. Several polygenic risk scores have been developed for predicting clinical stroke.35,36 In a prior work, we identified several vascular risk factors’ susceptibility genes that were also associated with CVD pathological changes.37 Further work adding a polygenic risk score to FRS may increase its accuracy and specificity for postmortem CVD pathologies. The development of risk profiles based on more varied clinical functions and genetic data together with brain imaging and biofluid biomarkers are likely to be needed to obtain more robust risk scores that identify adults at risk for CVD pathologies.

The study has several strengths. It included clinical and postmortem data from approximately 1700 well-characterized older adults. Structured autopsy was performed, and pathologic indices of both large and small cerebral vasculature were studied. However, the study has limitations. A reliable histopathologic measure of white matter disease or brain imaging metrics of white matter hyperintensities known to correlate with vascular risk factors and diseases was not measured. The participants were mainly Caucasians with high levels of education, limiting the generalizability of the results.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank participants of the Religious Orders Study, the Rush Memory and Aging project, and the Minority Aging Research Study. Also, we appreciate staff of the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

FUNDING SOURCES

The study was supported by grants R01AG56352, R01AG47976, P30AG10161, R01AG15819, R01AG17917, RF1AG022018, R01NS084965 and RF1AG059621 from National Institutes of Health, and the Illinois Department of Public Health.

Non-Standard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- CVD

Cerebrovascular disease

- ROS

Religious Orders Study

- MAP

Rush Memory and Aging Project

- MARS

Minority Aging Research Study

- FRS

general cardiovascular Framingham risk score

- CAA

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Shahram Oveisgharan: None.

Lei Yu: None.

Ana W. Capuano: None.

Zoe Arvanitakis: Grants from NIH during the conduct of the study and grants from Amylyx outside the submitted work.

Lisa L. Barnes: None.

Julie A. Schneider: Personal fees from Eli Lilly Inc. (AVID radiopharmaceutical) and personal fees from National Hockey League outside the submitted work.

David A. Bennett: None.

Aron S. Buchman: None.

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: No conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 7];139. Available from: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windham BG, Deere B, Griswold ME, Wang W, Bezerra DC, Shibata D, Butler K, Knopman D, Gottesman RF, Heiss G, et al. Small Brain Lesions and Incident Stroke and Mortality: A Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med 2015;163:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A, Giambrone AE, Gialdini G, Finn C, Delgado D, Gutierrez J, Wright C, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, Pandya A, et al. Silent Brain Infarction and Risk of Future Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stroke. 2016;47:719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thong JYJ, Hilal S, Wang Y, Soon HW, Dong Y, Collinson SL, Anh TT, Ikram MK, Wong TY, Venketasubramanian N, et al. Association of silent lacunar infarct with brain atrophy and cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2013;84:1219–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhamoon MS, Cheung Y-K, Moon Y, DeRosa J, Sacco R, Elkind MSV, Wright CB. Cerebral white matter disease and functional decline in older adults from the Northern Manhattan Study: A longitudinal cohort study. PLOS Med. 2018;15:e1002529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorelick PB, Furie KL, Iadecola C, Smith EE, Waddy SP, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bae H-J, Bauman MA, Dichgans M, Duncan PW, et al. Defining Optimal Brain Health in Adults: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2020 Jan 7];48. Available from: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Schneider JA. Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:S161–S189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes L L, Shah R C, Aggarwal N T, Bennett D A, Schneider J A. The Minority Aging Research Study: Ongoing Efforts to Obtain Brain Donation in African Americans without Dementia. Curr. Alzheimer Res 2012;9:734–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General Cardiovascular Risk Profile for Use in Primary Care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medi-Span: Master drug data base documentation manual.

- 11.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Lamar M, Shah RC, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Late-life blood pressure association with cerebrovascular and Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2018;91:e517–e525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oveisgharan S, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L, Farfel J, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease and common neuropathologies of aging. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 2018;136:887–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2004;62:1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Cochran EJ, Bienias JL, Arnold SE, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Relation of cerebral infarctions to dementia and cognitive function in older persons. Neurology. 2003;60:1082–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oveisgharan S, Arvanitakis Z, Yu L, Farfel J, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease and common neuropathologies of aging. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:887–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle PA, Yu L, Leurgans SE, Wilson RS, Brookmeyer R, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Attributable risk of Alzheimer’s dementia attributed to age-related neuropathologies: Age-Related Neuropathology Alzheimer’s dementia. Ann. Neurol 2019;85:114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHutchison CA, Backhouse EV, Cvoro V, Shenkin SD, Wardlaw JM. Education, Socioeconomic Status, and Intelligence in Childhood and Stroke Risk in Later Life: A Meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2017;28:608–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Walsh M, Hanna S, Iorio A, Devereaux PJ, McGinn T, Guyatt G. Discrimination and Calibration of Clinical Prediction Models: Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature. JAMA. 2017;318:1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2019;74:1376–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikram S, Pachika A, Schuster H, Ghotra A, Dotson L, Akbar S, Khan AR. Single-Center Retrospective Study of Risk Factors and Predictive Value of Framingham Risk Score of Patients with ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction. South. Med. J 2018;111:226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flueckiger P, Longstreth W, Herrington D, Yeboah J. Revised Framingham Stroke Risk Score, Nontraditional Risk Markers, and Incident Stroke in a Multiethnic Cohort. Stroke. 2018;49:363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Microinfarct Pathology, Dementia, and Cognitive Systems. Stroke. 2011;42:722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchman AS, Yu L, Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Brain pathology contributes to simultaneous change in physical frailty and cognition in old age. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1536–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchman AS, Leurgans SE, Nag S, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Cerebrovascular Disease Pathology and Parkinsonian Signs in Old Age. Stroke. 2011;42:3183–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conner SC, Pase MP, Carneiro H, Raman MR, McKee AC, Alvarez VE, Walker JM, Satizabal CL, Himali JJ, Stein TD, et al. Mid-life and late-life vascular risk factor burden and neuropathology in old age. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol 2019;acn3.50936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abner EL, Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA, Fardo DW, Woltjer RL, Cairns NJ, Yu L, Dodge HH, Xiong C, et al. Diabetes is associated with cerebrovascular but not Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:882–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujihara K, Suzuki H, Sato A, Ishizu T, Kodama S, Heianza Y, Saito K, Iwasaki H, Kobayashi K, Yatoh S, et al. Comparison of the Framingham Risk Score, UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Risk Engine, Japanese Atherosclerosis Longitudinal Study-Existing Cohorts Combine (JALS-ECC) and Maximum Carotid Intima-Media Thickness for Predicting Coronary Artery Stenosis in Patients with Asymptomatic Type 2 Diabetes. J. Atheroscler. Thromb 2014;21:799–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruzin JJ, Schneider JA, Capuano AW, Leurgans SE, Barnes LL, Ahima RS, Arnold SE, Bennett DA, Arvanitakis Z. Diabetes, Hemoglobin A1C, and Regional Alzheimer Disease and Infarct Pathology: Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord 2017;31:41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brundel M, Reijmer YD, van Veluw SJ, Kuijf HJ, Luijten PR, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ, on behalf of the Utrecht Vascular Cognitive Impairment (VCI) Study Group. Cerebral Microvascular Lesions on High-Resolution 7-Tesla MRI in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63:3523–3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, van Veluw SJ, Wong A, Liu W, Shi L, Yang J, Xiong Y, Lau A, Biessels GJ, Mok VCT. Risk Factors and Cognitive Relevance of Cortical Cerebral Microinfarcts in Patients With Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke. 2016;47:2450–2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oveisgharan S, Hachinski V. Executive dysfunction is a strong stroke predictor. J. Neurol. Sci 2015;349:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zammit AR, Hall CB, Bennett DA, Ezzati A, Katz MJ, Muniz-Terrera G, Lipton RB. Neuropsychological latent classes at enrollment and postmortem neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1195–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Levine SR, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Purpose in Life and Cerebral Infarcts in Community-Dwelling Older People. Stroke. 2015;46:1071–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hachiya T, Kamatani Y, Takahashi A, Hata J, Furukawa R, Shiwa Y, Yamaji T, Hara M, Tanno K, Ohmomo H, et al. Genetic Predisposition to Ischemic Stroke: A Polygenic Risk Score. Stroke. 2017;48:253–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutten-Jacobs LC, Larsson SC, Malik R, Rannikmäe K, MEGASTROKE consortium, International Stroke Genetics Consortium, Sudlow CL, Dichgans M, Markus HS, Traylor M. Genetic risk, incident stroke, and the benefits of adhering to a healthy lifestyle: cohort study of 306 473 UK Biobank participants. BMJ. 2018;k4168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou SH-Y, Shulman JM, Keenan BT, Secor EA, Buchman AS, Schneider J, Bennett DA, De Jager PL. Genetic Susceptibility for Ischemic Infarction and Arteriolosclerosis Based on Neuropathologic Evaluations. Cerebrovasc. Dis 2013;36:181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]