Abstract

In females, reproductive success is dependent on the expression of a number of genes regulated at different levels, one of which is through epigenetic modulation. How a specific epigenetic modification regulates gene expression and their downstream effect on ovarian function are important for understanding the female reproductive process. The trimethylation of histone3 at lysine27 (H3K27me3) is associated with gene repression. JMJD3 (or KDM6b), a jumonji domain–containing histone demethylase specifically catalyzes the demethylation of H3K27me3, that positively influences gene expression. This study reports that the expression of JMJD3 specifically in the ovarian granulosa cells (GCs) is critical for maintaining normal female fertility. Conditional deletion of Jmjd3 in the GCs results in a decreased number of total healthy follicles, disrupted estrous cycle, and increased follicular atresia culminating in subfertility and premature ovarian failure. At the molecular level, the depletion of Jmjd3 and RNA-seq analysis reveal that JMJD3 is essential for mitochondrial function. JMJD3-mediated reduction of H3K27me3 induces the expression of Lif (Leukemia inhibitory factor) and Ctnnb1 (β-catenin), that in turn regulate the expression of key mitochondrial genes critical for the electron transport chain. Moreover, mitochondrial DNA content is also significantly decreased in Jmjd3 null GCs. Additionally, we have uncovered that the expression of Jmjd3 in GCs decreases with age, both in mice and in humans. Thus, in summary, our studies highlight the critical role of JMJD3 in nuclear–mitochondrial genome coordination that is essential for maintaining normal ovarian function and female fertility and underscore a potential role of JMJD3 in female reproductive aging.

Keywords: ovary, JMJD3, epigenetics, fertility, mitochondrial dysfunction, reproductive aging

At the center of normal female fertility lies the proper growth and development of mammalian ovarian follicles leading to successful ovulation. This requires a complex multicellular crosstalk, involving balance and coordination of many cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, cell survival, and atresia. These dynamic processes require the activation and deactivation of number of genes that are regulated by modulating chromatin structure and gene transcription through diverse genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Gene expression is regulated at different levels, one of which is the post-translational modification of histone tails involving various epigenetic enzymes. These epigenetic enzymes through histone modifications, such as acetylation, deacetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, and/or ubiquitination, transiently alter the chromatin landscape rendering a gene active or inactive. While studies (1-3) have revealed that epigenetic modifications play a critical role in follicular development and normal ovarian function, the understanding of how a specific epigenetic modulator and/or a particular modification regulate a definite underlying ovarian function or its effect on overall female fertility is still limited.

One of the most common and best-studied post-translational histone modifications is histone methylation, primarily due to its importance in transcriptional regulation of gene expression in various organisms (4-6). Methylation of histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is generally associated with transcriptional activation (7), while trimethylation of histone 3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) is associated with gene repression (5, 6, 8-10). Steady-state levels of H3K27me3 are usually maintained by the functional balance between the enzymes that add this modification (the histone methyltransferases EZH1 and EZH2) and the enzymes that remove it (the Jumonji C domain–containing histone demethylase family, Kdm6a/UTX and Kdm6b/Jmjd3) (5, 6, 11, 12). Specifically, Jumonji domain–containing protein 3 (JMJD3) is involved in several cellular processes, such as differentiation, proliferation, senescence, and apoptosis (13) The regulation of JMJD3 is highly gene- and context-specific and is involved in several tissue responses, such as vertebrate development, cancer, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases (14-19).

In this study, we have generated genetically modified mice lacking histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27) demethylase JMJD3 specifically in the granulosa cells (GCs) of the ovary and provide direct genetic and molecular evidence that JMJD3 is a key regulator of ovarian function and essential for normal female fertility. The ovarian follicle primarily consists of theca cells (TCs), GCs, and the oocyte. During ovarian follicular development, prior to ovulation, follicles undergo different stages of development that involve rapid proliferation and differentiation of GCs that are required to support extensive oocyte growth. The energy requirement needed for these processes form an indispensable factor for normal follicle development. Therefore, optimum mitochondrial function is considered a fundamental requirement to meet the energy demands during the ovarian cycle. However, little is known about the regulation of mitochondrial function in GCs and the role this process plays in ovarian function and female fertility. Given that GC apoptosis plays a key role in follicular atresia (20), and multiple apoptotic pathways originate from the mitochondria (21), understanding the regulation of mitochondrial function in GCs is also critical. Here we report that JMJD3 through regulation of mitochondrial function in GCs promotes follicle growth, controls female fertility, and prevents ovarian aging.

Material and Methods

Generation of GC-specific Jmjd3 Knockout Mice

Mouse studies were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University (MSU) under the approval number PROTO202000156. To generate GC-specific JMJD3 KO mice, Jmjd3 floxed mice (Jackson laboratory, strain B6.Cg-Kdm6tm1.1Rbo/J; stock #029615) were mated with Amhr2-Cre (for GC-specific –/–) mice (MMRRC at UNC, strain B6;129S7-Amhr2tm3(cre)Bhr/Mmnc). First Jmjd3-loxPflox/flox females were crossed with Amhr2-cre males. The Amhr2-Cre transgene has been used extensively to drive GC-specific recombination of a gene of interest (22-24). Thereafter, the Amhr2-Cre/+;Jmjd3-loxPflox/+ females were backcrossed with Jmjd3-loxPflox/flox males to generate female heterozygous control Amhr2-Cre/+;Jmjd3-loxPflox/+ mice and Amhr2-Cre/;Jmjd3-loxPflox/flox mice conditionally deleted for Jmjd3 in the GCs (25). Genomic DNA was isolated from 21-day-old animals, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping with appropriate primers (25) was used to identify mice with Wt, floxed, and cre transgene, revealing bands of 368, 400, and 500 bp, respectively.

Estrous Cycle, Fertility Test, GC Isolation, and Superovulation

Estrous cycle was determined by daily vaginal smears for 2 weeks and then reproductive performance of wild-type (wt) and GC-Jmjd3KO animals were determined by a 12-week-long continuous mating study, as described previously (26). For GC isolation, ovaries were harvested at diestrus, trimmed of fat and bursa and GCs were isolated pre-antral and antral follicles by puncturing the follicles with a 30-gauge needle as described previously (27-29) Superovulation was performed only in the experiment where ovulated oocytes were counted. For all other experiments animals were not primed. Superovulation protocol involved a single intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) followed 48 hours later by 10 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (Sigma, #CG10). After an additional 18 hours, oocyte/cumulus masses were surgically isolated from the ampulla and counted.

Ovarian Histology

Ovarian morphology was determined using paraffin-embedded ovarian sections and previously published criteria for follicle counting (30, 31). Briefly, ovaries (n = 3, ovaries from 3 different Wt, Het, and GC-Jmjd3KO animals) were collected at diestrus, paraffin embedded, processed for sectioning (5-µm sections taken at 30-µm intervals), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for morphological analysis using previously published criteria (30-32). Briefly, follicle numbers were evaluated as (1) primordial follicles, identified by an oocyte partially or completely encapsulated by flattened squamous cells; (2) primary follicles, single layer of cuboidal GCs around the oocyte; (3) secondary to tertiary follicles (pre-antral), 2 layers or more of cuboidal GCs (no antrum); (4) antral follicles, presence of an antrum; and (5) corpus luteum. Atretic pre-antral follicles were identified by the presence pyknotic nuclei in ≥10% GCs with nonintact oocytes (convoluted and condensed or fragmented). Antral follicles were considered atretic based on any 2 of the following criteria: disorganized/uneven GC layer or GCs pulling away from the basement membrane, presence of pyknotic bodies in ≥10% GCs or in the antrum, broken basement membrane, and nonintact (degenerating or fragmented) oocyte.

Granulosa Cell Culture and siRNA Knockdown

GCs were isolated by needle puncture under the microscope and cultured for 48 hours in DMEM/F-12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin, as described previously (33). SiRNA-mediated knockdown experiments were performed as described previously (6, 29, 33) using nontargeting siRNA (Nsp) pool or mouse siRNA ON-TARGET Plus SMARTpool siRNAs (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The siRNAs used were mouse Kdm6b (Jmjd3) siRNA (M-063799-1-0005, Dharmacon), mouse Lif siRNA(M-047120-01-0005, Dharmacon), mouse Ctnnb1 (M-040628-00-0005, Dharmacon), and nontargeting pool (D-001810-10-05, Dharmacon).

Immunohistochemistry was performed using the ABC method (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for paraffin-embedded ovarian sections, as described previously (31). The antibody used was rabbit anti-JMJD3 (34).

Immunofluorescence

For immunostaining, Optimal Cutting Temperature OCT-embedded ovarian tissue sections were incubated with rabbit anti-JMJD3 antibody (34) followed by goat antirabbit IgG (H+L) Alexa Fluor 568 (Thermofisher, #A-11011). Thereafter, slides were mounted with VECTASHIELD® antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Lab, #H-1200-10) and imaged using immunofluorescent microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE, Ti) and NIS Elements AR analysis software.

Serum Hormone Levels

Serum luteinizing hormone (LH) (assay sensitivity ≤5.2 mIU/mL) and FSH (assay sensitivity ≤0.5 mIU/mL) level was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits following the manufacturer’s instructions (35, 36).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blots were performed as described previously (33, 37, 38). Antibodies used were rabbit anti-JMJD3 (34), rabbit anti-GAPDH (39), rabbit anti-BAK (40), rabbit anti-BAX (41), rabbit anti-BMF (42), rabbit anti-p53 (43), rabbit anti-pSTAT3 (44), mouse anti-STAT3 (45), rabbit anti-H3K27me3 (46), rabbit anti-H3 (47), rabbit anti-LIF (Leukemia inhibitory factor) (48), rabbit anti-β Catenin (49). All antibodies used were at 1:1000 dilution.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR was performed by the ∆/∆ Ct method as described previously (6, 33) using 1 μg of RNA for all the qRT-PCR reactions with Taqman gene expression assay primers (assay IDs: Mm01332680_m1- Jmjd3, Mm00437433_m1-Adcyap1, Mm01176594_g1- Upk1a, Mm00659043_m1-Myl1, Mm04225292_g-mt-nd3, Mm04225306_g1- mt-nd4l, Mm00434762_g1-Lif, Mm00452131_m1-Sirt3, Mm00483029_g1-Ctnnb1, Mm02601633_g1-Rpl19). Each target gene was normalized to Rpl19.

RNA Isolation and RNA-seq

Total RNA isolation, library construction and RNA-sequencing services were carried out by Genewiz, Inc. as described previously (6, 38). For RNA-seq, total RNA was extracted from GCs isolated from Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO animals (GCs from 5 animals were pooled together to make n = 1 and 3 such pooled samples/genotype were used for the RNA-seq studies) using Qiagen RNeasy Plus Universal mini kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA samples were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and RNA integrity was checked using Agilent TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). RNA integrity number for all the samples was between 9.7 and 10. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using 500 ng of RNA, and the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina following the manufacturer’s instructions (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). The sequencing library was validated on the Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as well as by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). The sequencing libraries were clustered on a single lane of a flow cell. After clustering, the flow cell was loaded on the Illumina HiSeq instrument (4000 or equivalent) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2 × 150 bp paired end configuration. The total number of reads/sample were 45 to 50 million. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the HiSeq Control Software. Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina HiSeq was converted into fastq files and demultiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq 2.17 software. One mismatch was allowed for index sequence identification.

Bioinformatics Analysis for RNA-seq

Raw data quality was judged based on Illumina’s Q score, which represents the error rate at each base, built on a log10 score. Thereafter, sequence reads were trimmed to remove possible adapter sequences and nucleotides with poor quality using Trimmomatic v.0.36. The trimmed reads were mapped to the reference Mus musculus GRCm38 genome available on ENSEMBL using the STAR aligner v.2.5.2b. The STAR aligner uses a splice aligner that detects splice junctions and incorporates them to help align the entire read sequences. BAM files were generated as a result of this step. Unique gene hit counts were calculated by using feature Counts from the Subread package v.1.5.2. Only unique reads that fell within exon regions were counted. After extraction of gene hit counts, the gene hit counts table was used for downstream differential expression analysis. Using DESeq2 R package, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified between Wt (n = 3) and GC-Jmjd3KO (n = 3). The heat maps were constructed using rlog transformed values obtained from RNA-seq data followed by z-normalization. The Wald test was used to generate P values and the Benjamini–Hochberg test for adjusted P values. Genes with adjusted P ≤ .05 and absolute log2 fold changes >.5 were called as DEGs for each comparison. For gene ontology analysis, significantly differentially expressed genes were clustered by their gene ontology and the enrichment of gene ontology terms were tested using Fisher’s exact test (GeneSCF v1.1-p2). Pathways with P ≤ .05 were considered statistically significant. A list of all the differentially expressed genes is in the Supplemental Data (25). The RNAseq data is available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE195498) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE195498).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using MAGnify chromatin immunoprecipitation system (Invitrogen) as previously described (6, 29, 33, 38). Chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated with Dynabeads coupled with rabbit anti-H3K27me3 ChIP grade antibody (Abcam, #ab6002; 2 µg per ChIP reaction) and rabbit-IgG as nonspecific control (Invitrogen, #49-2024; 1 µg per ChIP reaction). Quantitative PCR was performed using PerfeCTa SYBR Green Supermix, ROX (VWR, #95055-500) with primers designed within 500 bp from Transcription Start Site (TSS) (identified using the eukaryotic promoter database) of the mouse Lif and Ctnnb1 promoters (25).

TUNEL Assay

The TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assay was performed by using an ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis detection kit (Millipore Sigma, #S701) as described previously (31).

JC-1 Dye Assay

For mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ M), JC-1 activity was measured using the JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (Cayman Chemicals, #10009172). This assay is based on the concept that in healthy cells with high mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ M), JC-1 spontaneously forms complexes known as J-aggregates with intense red fluorescence. Conversely, in apoptotic or unhealthy cells with low Δψ M, JC-1 remains in the monomeric form, which shows only green fluorescence. Nonspecific and Jmjd3 siRNA treated GC cultures were stained with JC-1 staining solution for 30 minutes (37°C), washed twice with assay buffer, and then JC-1 aggregates were measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 535 nm and 595 nm respectively. JC-1 monomers were measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 535 nm. The ratio of fluorescent intensity of J-aggregates and J-monomers (red:green) was used as an indicator of cell health. For fluorescence microscopy, the stained cells were visualized by fluorescence microscope (TE2000-U Inverted Microscope, Nikon). All procedures were conducted under dark conditions.

Oxygen Consumption Rate

The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured according to the manufacturer’s protocol using a phosphorescent oxygen probe (Cayman Chemical, #600800). Nonspecific and Jmjd3 siRNA-treated GC cultures were subjected to 10 µL of phosphorescent oxygen probe solution and the phosphorescent signal was measured kinetically for 120 minutes using a SpectraMax M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices). GCs treated with Antimycin A, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, blank wells (no cells) with phosphorescent oxygen probe solution and cells without any probe were used as negative controls. Glucose oxidase (reference for oxygen depletion) was used as positive control.

Determination of ATP Level

ATP content in GCs was measured by ATPlite™ Luminescence ATP Detection Assay System (Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences B.V., #6016943) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were normalized to total protein, and metabolite contents were expressed as nm/mg protein.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed in the MSU flow cytometry core facility using APC Annexin V (BioLegend, #640920) containing Helix NP™ Green (BioLegend, #425303) and Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA); 1 × 105 cells were analyzed per sample in 3 independent experiments. Quadrants were set based on heat-killed control samples. FCS Express software (De Novo Software) was used for analysis.

Mitochondrial DNA Content

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content was calculated using quantitative real-time PCR as described previously (50-52). GCs were lysed using mammalian cell lysis buffer (Abcam) (with 200 µg/mL Proteinase K and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and samples were used directly for PCR analysis. The mtDNA content was calculated using quantitative real-time PCR by measuring the threshold cycle ratio (ΔCt) of a mitochondria-encoded gene B6 (B6F 5′-AACCTGGCACTGAGTCACCA-3′ and B6R 5′-GGGTCTGAGTGTATATATCATGAAGAGAAT-3′) vs a nuclear gene NDUFV1 (NDUFV1F 5′-CTTCCCCACTGGCCTCAAG-3′ and NDUFV1R 5′-CCAAAACCCAGTGATCCAGC-3′). Data were expressed as mtDNA/nuclear DNA. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

Collection of Human Granulosa Lutein Cells

Isolation of granulosa lutein cells during oocyte retrieval from patients undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) was performed as described previously (53). Briefly, follicular fluids were obtained from oocyte aspiration during routine IVF procedure and clumps of granulosa lutein cells were isolated from the follicular fluid after oocyte retrieval under dissecting scope using a Pasteur pipette. Thereafter, granulosa lutein cells were washed and subjected to 60% percoll gradient to remove red blood cells and frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA isolation. Women (n = 8) between the ages of 25 and 30 years undergoing oocyte retrieval due to male factor were used as controls and women (n = 8) between the ages of 37 and 42 years undergoing IVF were used for the advanced age group.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad Software). Statistical comparisons were made by paired/unpaired Student’s t test (for comparing 2 groups), a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s (for comparing multiple groups), or a 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc analysis (for comparing multiple groups and variables), and results with P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Lack of JMJD3 in Granulosa Cells of the Ovary Causes Subfertility and Premature Ovarian Failure

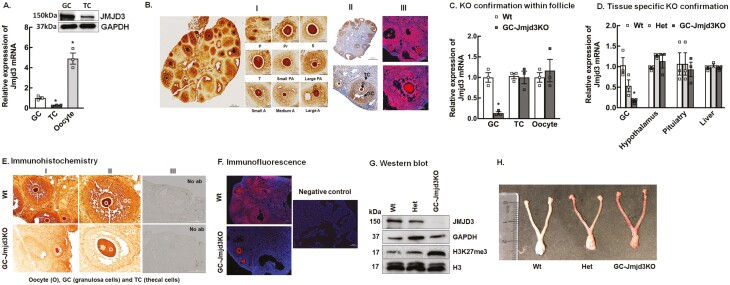

While the role of JMJD3 in ovarian cancer is well established (54-56), the expression and the physiological role of JMJD3 in normal ovary governing female fertility is not known. Our results show that Jmjd3 mRNA (Fig. 1A) and JMJD3 protein (Fig. 1A, inset, and 1B) is expressed primarily in the GCs and oocytes of the follicle and is very limited in the theca cells (Fig. 1A, inset, and 1B). To elucidate the physiological role of JMJD3 in female reproduction, we generated GC-specific Jmjd3KO mice by crossing loxp-flanked Jmjd3 allele (Jmjd3loxp/loxp) mice with Amhr2-Cre mice (25). To confirm that Amhr2-Cre-mediated recombination was restricted to the GCs and not in other cell types of the follicle or in peripheral tissues, Jmjd3 mRNA levels were determined in GCs, oocytes, theca cells of the follicle (Fig. 1C), as well as in the hypothalamus, pituitary and liver (Fig. 1D) isolated from wt, heterogeneous (het) littermates, and GC-Jmjd3KO animals. The efficiency of Jmjd3 KO was further established by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1E), immunofluorescence (Fig. 1F), and Western blot analysis (Fig. 1G) that showed reduction of JMJD3 specifically in the GCs isolated from the GC-Jmjd3KO animals compared to wt and het littermates. Furthermore, given that JMJD3 specifically demethylates the trimethyl mark on H3K27, H3K27me3 levels were significantly higher in GCs isolated from GC-Jmjd3KO animals than from het littermates and wt mice (Fig. 1G). To determine whether knockout of Jmjd3 using the Amhr2 promoter to drive Cre expression altered the gross morphology of the female ovary and uterus, we also examined the reproductive organs from 8- to 9-week-old female mice at estrus. Under macroscopic examination, the ovaries, and uteri of GC-specific Jmjd3KO animals appeared to be normal compared with wt and het animals (Fig. 1H).

Figure 1.

Expression of Jmjd3 in ovarian cells and development of granulosa cell-specific Jmjd3 knockout mouse model (A) Expression of Jmjd3 mRNA in granulosa cells (GCs), theca cells (TCs), and oocytes isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt mice. The mRNA levels were measured by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized to Rpl19 mRNA using the ΔΔCt method. Results are represented as means ± SEM (n = 3, *P < .01 vs GCs using Student’s t-test). Representative Western blot (inset) of JMJD3 expression in GCs and TCs isolated from Wt mice (n = 3). (B) Representative immunohistochemistry (panel I and II) and immunofluorescence (panel III) of JMJD3 expression in the ovarian section of 8- to 9-week-old Wt mice. P, primordial follicle; Pr, primary follicle; S, secondary follicle; t, tertiary follicle; PA, pre-antral follicle; A, antral follicle. (C) Relative expression of Jmjd3 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in granulosa cells (GCs), theca cells (TCs), oocytes isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 3) and normalized to Rpl19 (*P < .01 vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (D) Relative expression of Jmjd3 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in granulosa cells, hypothalamus, pituitary and liver isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt, heterozygous (Het), and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 3) and normalized to Rpl19 (*P < .01 vs Wt using 2-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test). (E,F) Representative immunohistochemistry (E) and immunofluorescence (F) pictures of ovarian sections showing JMJD3 expression in follicles isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-specific Jmjd3KO mouse. GC, granulosa cells; O, oocyte; TC, theca cells. (G) Representative immunoblots demonstrating the expression JMJD3 and H3K27me3 levels in granulosa cells isolated from Wt, heterozygous (Het) litter mates and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. GAPDH and H3 are used as internal controls (n=3). (H) Granulosa cell–specific Jmjd3 knockout mice have normal reproductive organs. Macroscopic comparison of the female utero-genital tract at estrus between 8- to 9-week-old Wt, heterozygous (Het) litter mates, and GC-Jmjd3KO mice.

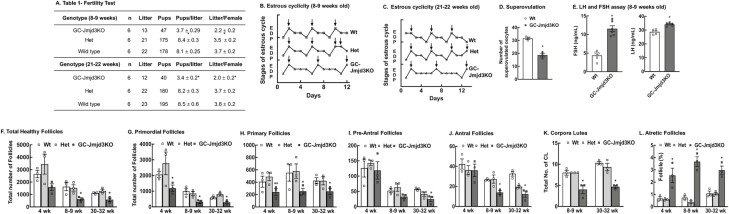

To evaluate the reproductive performance of GC-Jmjd3KO mice, a 12-week-long mating study was conducted in 8- to 9-week-old and 20- to 22-week-old animals (Fig. 2A). At both age groups, GC-Jmjd3KO animals were subfertile, with smaller litter size and fewer number of litters compared to wt and het mice. Furthermore, GC-Jmjd3KO mice had longer estrous cycle (Fig. 2B and 2C) than het littermates (5.3 ± 0.1 vs 3.72 ± 0.2 days for mice aged 8-9 weeks and 4.9 ± 0.2 vs 3.5 ± 0.2 days for mice aged 20-22 weeks ) due to increased duration of diestrus (25). Notably, superovulation failed to rescue the subfertility phenotype (Fig. 2D), as the number of superovulated oocytes were significantly lower in GC-Jmjd3KO mice than in wt animals (18.7 ± 1.5 vs 31.7 ± 0.9). Together, these studies demonstrate that ablation of Jmjd3 in the GCs of the follicle is enough to cause disruption of estrous cycle and reduced fertility in female mice by 8-9 weeks of age leading to premature ovarian failure. Serum levels of both FSH and LH were also elevated (Fig. 2E) in GC-Jmjd3KO animals and compared with wt at estrus, which is in accordance with characteristics associated with premature ovarian failure (57-59).

Figure 2.

Expression of Jmjd3 in granulosa cells is important for female fertility. (A) Fertility test: Wt, Het and GC-Jmjd3KO female animals were subjected to 12-week-long continuous mating study with Wt males. Two females were housed with 1 8- to 10-week-old fertile Wt male mouse. The male was replaced every 2 weeks with another fertile male. Cages were monitored daily, and number of pups and litters were recorded. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6, *P < .01 vs Wt using ANOVA). (B,C) Knockout of Jmjd3 disrupts estrous cyclicity. Representative estrous cycles of individual Wt, Het, and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Estrus stage is denoted by an arrow in each case. Estrus stage is denoted by arrow in each case (E, estrus; D, diestrus; P, proestrus;). Six mice were taken from each genotype to test the estrous cyclicity. (D) Number of superovulated oocytes in 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Mice were given a single intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Biovendor) followed 48 hours later by 10 IU of human chronic gonadotropin (Sigma). After 18 hours, oocyte/cumulus masses were surgically isolated from the ampulla and counted. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 mice, *P < .01 vs Wt, using Student’s t test). (E) Serum concentration of LH and FSH in Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3, *P < 0.01 vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (F-K) Follicle numbers in the ovaries of 4-, 8- to 9-, and 30- to 32-week-old Wt, Het, and GC-Jmjd3KO female mice. The types of follicles counted are (F) total, (G) primordial (Pr), (H) primary (P), (I) pre-antral (PA), (J) antral (A) and (K) corpus luteum (CL) (n = 3 ovaries per genotype; *P < .05 vs Wt, **P < 0.05 vs Het using Student’s t-test). (L) Ovaries of GC-Jmjd3KO mice have increased percentage of atretic follicle compared to Wt mice (n = 3, *P < .05 vs Wt using Student’s t-test).

Ovaries From GC-specific Jmjd3KO Mice Have Fewer Healthy Follicles and Increased Follicular Atresia

To gain further insight into the reduced fertility of the GC-specific Jmjd3KO mice, ovarian morphology was studied and compared with corresponding het littermates and wt animals. In general, irrespective of age, GC-Jmjd3KO mice had significantly fewer healthy follicles (Fig. 2F). Further analysis into specific types of follicles revealed that the number of healthy primordial (Fig. 2G) and primary follicles (Fig. 2H) were significantly lower in GC-Jmjd3KO mice at all ages than in wt and het mice. In contrast, at 4 weeks of age, the number of healthy preantral (Fig. 2I) and antral follicles (Fig. 2J) in GC-Jmjd3KO ovaries were similar to ovaries from wt and het littermates. However, with age the number of healthy pre-antral and antral follicles decreased significantly in GC-Jmjd3KO mice (Fig. 2I and J). The numbers of corpora lutea were also significantly lower in 8- to 9-week-old and 30- to 32-week-old GC-Jmjd3KO mice (Fig. 2K), reflecting the observed subfertility phenotype in these animals. Additionally, GC-Jmjd3KO ovaries contained a considerably higher percentage of atretic follicles relative to het littermates and wt mice (Fig. 2L). Representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained ovarian sections from 4 weeks, 8- to 9-week-old, and 30- to 32-week-old wt, het littermates, and GC-Jmjd3KO mice are elsewhere (25).

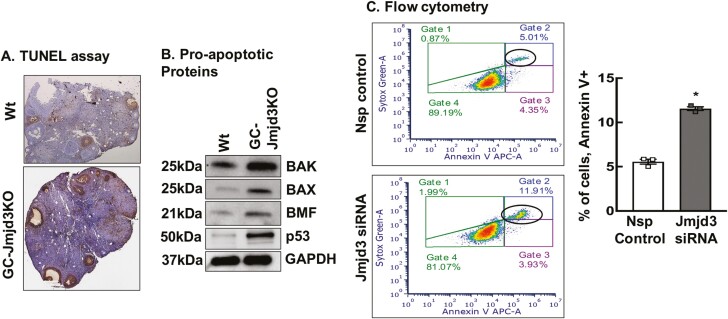

Evidence of increased atresia was also evident from the higher rate of DNA fragmentation determined by TUNEL staining in ovaries (Fig. 3A) as well as increased expression of pro-apoptotic proteins BAK, BAX, BMF, and p53 in GCs isolated from 8- to 9-week-old GC-Jmjd3KO mice relative to wt animals (Fig. 3B). In fact, siRNA-mediate knockdown of Jmjd3 in primary mouse GCs from wt mice increased GC apoptosis, as determined by flow cytometry for Annexin V expression (Fig. 3C), thereby providing a direct relationship between Jmjd3KO in GCs and increased rate of follicular atresia.

Figure 3.

Ablation of Jmjd3 promotes the granulosa cell apoptosis. (A) Ovaries from GC-Jmjd3KO females have a higher rate of apoptosis. TUNEL-stained sections of ovarian tissue from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO animals (n = 3). (B) Pro-apoptotic protein levels in 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO animals (n = 6). (C) Representative figure of Annexin V-APC and PI-stained flow cytometry analysis showing the extent of apoptosis in Jmjd3 siRNA treated mouse granulosa cells. Histogram represents the percentage of apoptotic primary mouse GCs treated with nonspecific siRNA (Nsp) control or Jmjd3 siRNA for 48 hours. Data are displayed as means ± SEM (n = 3 experiments and for each experiment, GCs isolated from 3 mice were pooled together *P < .01 vs. Nsp siRNA using Student’s t-test).

JMJD3 Regulates the Expression of Genes Critical for Granulosa Cell Function

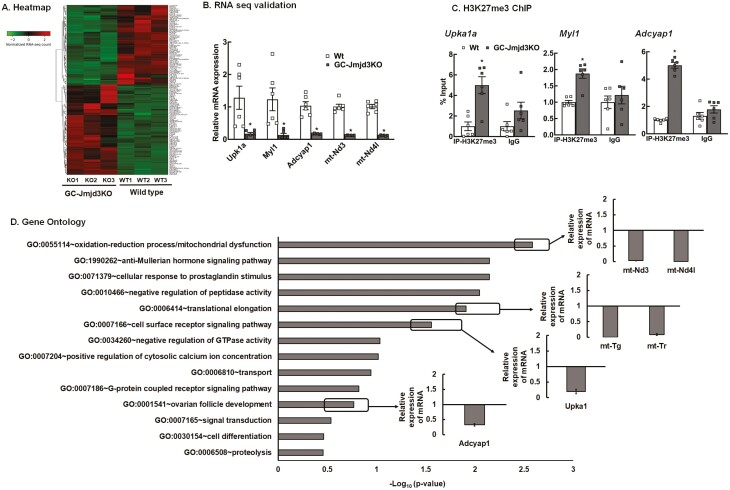

In order to understand how JMJD3 functions in GCs, we initially performed a RNA-seq analysis in GCs isolated from wt and GC-Jmjd3KO animals. The overall similarity among samples was assessed by the Euclidean distance between samples (25). DESeq2 analysis identified a total of 145 annotated significant DEGs (ENSEMBL). Out of these genes, 77 were upregulated and 68 were downregulated genes fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM > 1). The global transcriptional change across the 2 groups compared (wt vs GC-Jmjd3KO) is represented by hierarchical clustering of all the significant DEGs (Fig. 4A) and a volcano plot (25). The complete list of significant DEGs is presented elsewhere (25). Top DEGs—Upk1a (uroplakin1A, a member of the transmembrane 4 superfamily), Myl1 (myosin light chain 1), and Adcyap1 (adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide 1)—were selected to verify the RNA-seq data by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 4B). Moreover, ChIP-qPCR studies (Fig. 4C) with H3K27me3 antibody show an increased level of the H3K27me3 mark on the promoter region of the above-mentioned genes in GCs isolated from GC-Jmjd3KO mice. This establishes that the downregulation of these genes is directly due to increased levels of H3K27me3, a gene repressive mark caused by ablation of JMJD3, a demethylase that specifically removes the trimethyl mark on H3K27.

Figure 4.

Knockout of Jmjd3 alters global transcriptome level in mouse granulosa cells (A) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in granulosa cells isolated from 8- to 9-week-old GC-Jmjd3KO and Wt mice (n = 3 samples and for each samples, GCs isolated from 5 mice were pooled) sorted by adjusted P value by plotting their log2 transformed expression values in samples. (B) Relative expression of Upk1a, Myl1, Adcyap1, mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in the GCs isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Data are displayed as means ± SEM (n = 6) and normalized to Rpl19 *P < .05 vs Wt using Student’s t-test. (C) Anti-H3K27me3 ChIP-assay in GCs isolated from ovaries of 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice showing H3K37me3 levels within the promoter (–500 bp from TSS) of Upk1a, Myl1, Adcyap1 genes. IgG represents non-specific antibody. Values represent percentage input. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 experiments, for each experiment GCs isolated from 3 mice were pooled together: and *P < .05, vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (D) Gene ontology analysis: Gene ontology terms of significantly enriched pathways with an adjusted P < .05 in the differentially expressed gene sets.

Gene ontology enrichment analysis (Fig. 4D) of the DEGs revealed oxidation–reduction process (mitochondrial dysfunction), Anti-Müllerian hormone signaling, translation elongation, cell surface/G protein–coupled receptor signaling pathways and ovarian follicle development as some of the primary biological processes to be significantly affected by ablation of JMJD3 specifically in the GCs. These pathways/genes provide an insight into the role of JMJD3 in regulating follicular development and overall female fertility. Given that GC-Jmjd3KO mice show an increased rate of GC apoptosis (follicular atresia) and the important role of mitochondria in apoptosis, further validation by quantitative real-time PCR shows that mitochondrial genes, mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l, are significantly downregulated in GCs from GC-Jmjd3KO mice compared with wt animals (Fig. 4B). mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l encode for NADH dehydrogenase 3 (ND3) and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4L (ND4L) protein, respectively, which are located in the inner membrane of the mitochondria and play a major role in the electron transport chain (60-62). Therefore, we hypothesized that in GCs, JMJD3 regulates mitochondrial function and mitochondrial dysfunction is an underlying cause for the increased GC apoptosis/follicle atresia and subfertility observed in the GC-Jmjd3KO animals.

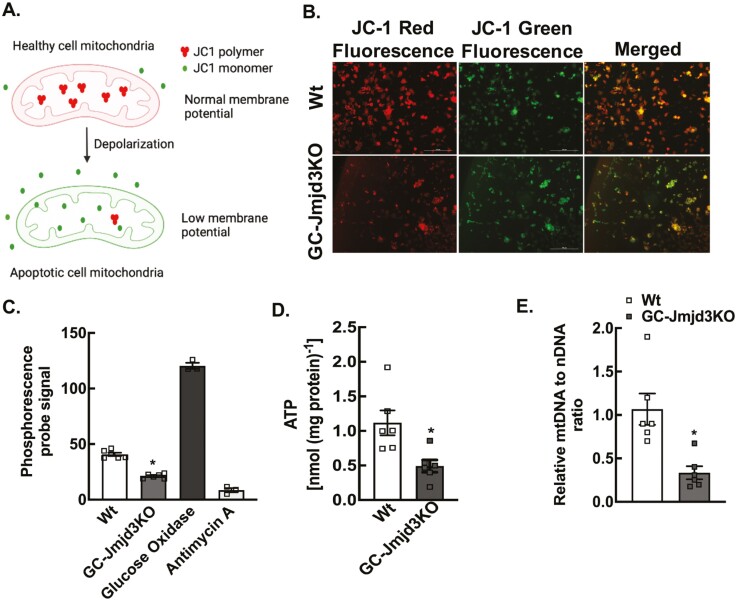

Ablation of JMJD3 in GCs Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction

To determine if indeed JMJD3 regulates mitochondrial function in GCs, we evaluated mitochondrial membrane potential, total ATP level, and OCR, both in vivo (in GCs isolated from GC-Jmjd3KO animals) and in vitro (in primary mouse GC cultures from wt mice treated with Jmjd3 siRNA). Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential was measured with JC-1 dye. In healthy cells with high mitochondrial membrane potential, JC-1 dye translocates into the mitochondria and aggregates, emitting red fluorescence (Fig. 5A). In contrast, in apoptotic or unhealthy cells with low mitochondrial membrane potential, JC-1 remains in a monomeric form, which emits only green fluorescence (Fig. 5A). Results show that ablation of Jmjd3 in GCs significantly decreases mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 5B). Moreover, mitochondrial respiration was significantly altered in Jmjd3KO GCs, exhibiting ~2-fold decrease in OCR (measured by phosphorescent oxygen probe, Cayman Chemicals) (Fig. 5C) and in total ATP levels (Fig. 5D) compared with GCs isolated from wt mice. Similar results were also observed in siRNA-mediated Jmjd3 knocked down primary mouse GC cultures (25). To evaluate whether Jmjd3 has any effect on mitochondrial biogenesis through mitochondrial genomic changes, mtDNA content relative to the nuclear DNA content was determined using a qPCR-based procedure. Results show that the ratio of mtDNA to nuclear DNA content was notably decreased by ~3-fold in Jmjd3KO GCs compared with age-matched wt GCs (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Ablation of Jmjd3 disrupts cellular respiration and ATP production in granulosa cells. (A) Schematic representation of JC-1 dye in regulating membrane potential. Higher ratio of red to green fluorescence represents higher polarization of mitochondrial membrane. (B) Representative pictures demonstrating mitochondrial membrane potential measured by JC-1 labeling in granulosa cells isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice (scale bar = 200 µm). (C) Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) in granulosa cells isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Glucose oxidase and Antimycin A represent positive and negative controls, respectively. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6; *P < .01 vs Wt using 1-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test). (D) ATP levels in Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO female mice. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 for each genotype; *P < .05 vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (E) Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content represented as ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear DNA (mtDNA/nDNA) in granulosa cells isolated from ovaries of 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6, *P < .01 vs Wt using Student’s t-test).

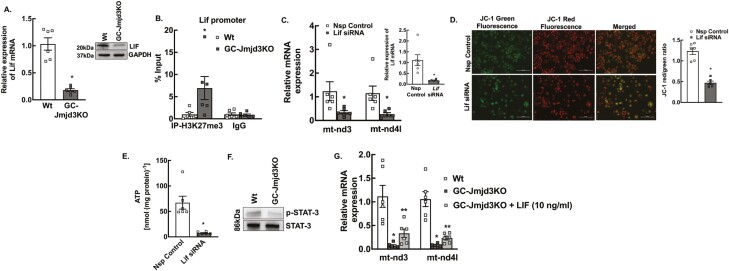

JMJD3 Regulates Crosstalk Between Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genome

In our effort to elucidate how the nuclear effects of JMJD3 regulate the expression of mitochondrial genome encoding genes like mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l, we performed bioinformatics analysis to identify upstream signaling pathways involved in regulating these genes. We found that mRNA and protein levels of Lif/LIF, which is a key upstream regulator of mitochondrial genes (63), were significantly downregulated (Fig. 6A) in GCs of GC-Jmjd3KO animals (as well as when Jmjd3 knocked down by siRNA in primary mouse GC cultures from wt mice) (25).

Figure 6.

Jmjd3 affects mitochondrial function by regulating Lif expression. (A) Relative expression of Lif mRNA and LIF protein (inset) levels by quantitative PCR and Western blot, respectively, in mouse granulosa cells isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6) and normalized to Rpl19 (*P < .01 vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (B) Anti-H3K27me3 ChIP-assay in granulosa cells isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice showing H3K37me3 levels within the promoter region (–500 bp from TSS) of Lif. IgG represents non-specific antibody. Values represent percentage input. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 experiments and for each experiment granulosa cells isolated from 3 mice were pooled together; and *P < .05 vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (C) mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l mRNA levels in primary cultures of granulosa cells treated with nonspecific (Nsp) control or Lif-specific siRNA for 48 hours. Inset represents the confirmation of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Lif (inset). Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 experiments, for each experiment GCs isolated from 2 mice were pooled together) and normalized to Rpl19 (*P < .01 vs Nsp control using Student’s t-test). (D) Representative figure of mitochondrial membrane potential change measured by JC-1 labeling in primary granulosa cells cultures isolated from 8- to 9-week-old mice and treated with nonspecific (Nsp) control or Lif-specific siRNA (Scale bar = 200 µm). Bar diagram shows the quantification of the JC-1 red-to-green ratio. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6, *P < .01 vs Nsp control using Student’s t-test). (E) ATP levels in granulosa cells treated with nonspecific (Nsp) control or Lif-specifc siRNA. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6; *P < .01 vs Nsp control using Student’s t-test). (F) Representative Western blot of phosphorylated-STAT3 (p-STAT3, Tyr705) and total STAT3 levels in GCs isolated from GC-Jmjd3 KO and Wt mice (n = 3). (G) mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l mRNA levels in primary cultures of GCs treated with/without LIF (10 ng/mL, 18 hours) isolated from GC-Jmjd3KO mice compared with Wt animals. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6) and normalized to Rpl19 (*P < .01 vs Wt and **P < .05 vs GC-Jmjd3KO using Student’s t-test).

Since JMJD3 decreases the H3K27me3 repressive mark resulting in gene expression, ablation of JMJD3 would increase H3K27me3, causing gene repression. Given that Lif expression is downregulated in GC-Jmjd3KO mice, we hypothesized that KO of Jmjd3 in GCs increases H3K27me3 levels that inhibit expression of Lif and in turn causes decreased expression of mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l. We therefore performed ChIP-PCR analysis with H3K27me3 antibody in GCs that showed increased level of H3K27me3 on the promoter of Lif in GC-Jmjd3KO compared with wt mice (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Lif (Fig. 6C, inset) in primary mouse GC cultures resulted in decreased expression of mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l (Fig. 6C) as well as significantly decreased mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 6D) and total ATP level (Fig. 6E).

LIF actions are mediated through the JAK/STAT pathway (64, 65). Our results are in accordance with these studies as GCs isolated from GC-Jmjd3KO mice (with decreased Lif expression, Fig. 6A) have lower levels of phosphorylated STAT3 than Wt animals (Fig. 6F) and siRNA-mediated Lif knockdown in GCs (from Wt mice) also lowers activated STAT3 levels (25). Notably, LIF treatment (for 18 hours, 10 ng/mL, Sigma) of Jmjd3 null GCs partially rescued the expression of mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l (~5 and ~3 fold vs untreated Jmjd3 null GCs, respectively Fig. 6G).

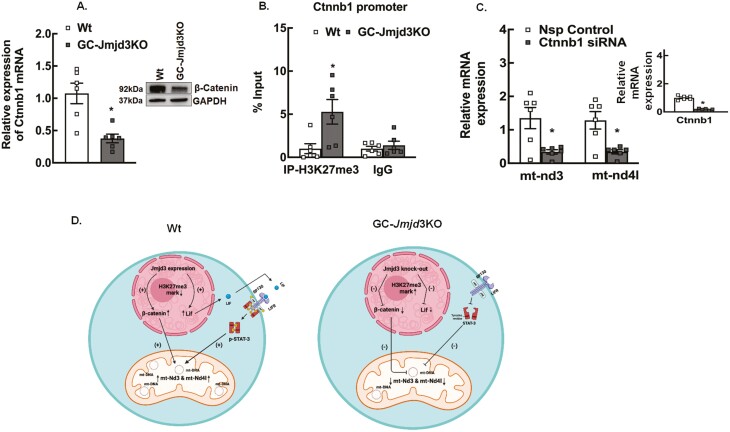

Similar to Lif, we also found that the expression of Ctnnb1 (β-catenin) mRNA and protein levels to be significantly downregulated (Fig. 7A and (25)) while H3K27me3 levels were increased in the Ctnnb1 promoter (Fig. 7B) region in GCs of GC-Jmjd3KO animals. β-Catenin has been reported (66-69) to play a role in mitochondrial function and biogenesis, and consequently our results show that siRNA-mediated knockdown of Ctnnb1 decreased mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l expression (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Regulation of β-catenin expression is another way JMJD3 influences mitochondrial gene expression and biogenesis. (A) Relative expression of Ctnnb1 mRNA and β-catenin protein levels (inset) in granulosa cells isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice. The mRNA levels were measured by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized to Rpl19 mRNA using the ΔΔCt method. Results are represented as means ± SEM (n = 6, for *P < .01 vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (B) Anti-H3K27me3 ChIP-assay in granulosa cells isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt and GC-Jmjd3KO mice showing H3K37me3 levels within the Ctnnb1 promoter (–500 bp from TSS). IgG represents nonspecific antibody. Values represent percentage input. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 experiments and for each experiment granulosa cells from 3 mice were pooled together: and *P < .05, vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (C) Effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of Ctnnb1 on mt-Nd3 and mt-nd4l mRNA levels in primary granulosa cell cultures isolated from 8- to 9-week-old Wt mice treated with nonspecific (Nsp) control and Ctnnbl-specific siRNA. Data are displayed as means ± SEM (n = 6 experiments, for each experiment GCs isolated from 2 mice were pooled together, *P < .05 vs Nsp control using Student’s t-test) and normalized to Rpl19. (D) Proposed model. JMJD3 directly induces Lif and Ctnnb1 expression by decreasing the H3K27me3 gene repressive mark on their promoter region. LIF in turn induces the expression of mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l by activating STAT3. Ctnnb1 (ß-catenin) also influences the expression of these genes as well as regulated mitochondrial biogenesis.

Together these studies demonstrate (Fig. 7D) that JMJD3 directly induces Lif and Ctnnb1 expression by decreasing the H3K27me3 gene repressive mark on their promoter region. LIF in turn induces the expression of mt-Nd3 and mt-Nd4l by activating STAT3. Ctnnb1 (β-catenin) also influences the expression of these genes as well as regulated mitochondrial biogenesis (66, 67).

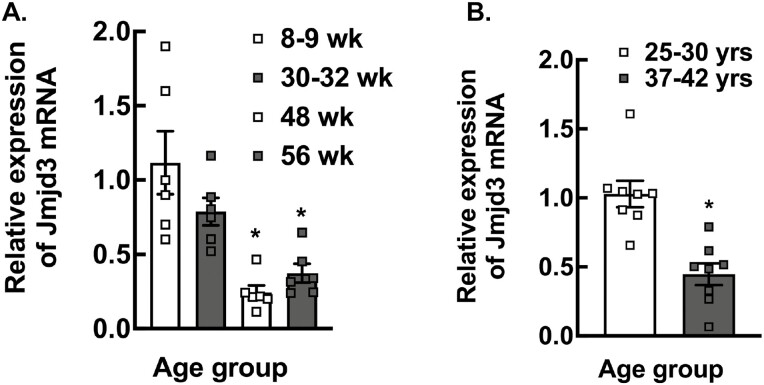

Expression of Jmjd3 in Mouse GCs and Human Granulosa lutein Cells Decrease With Age

There have been a number of studies (70) that have reported changes in epigenetic marks and expression of epigenetic enzymes in oocytes of females of advanced age. Mitochondrial dysfunction has also been associated with female reproductive aging (71, 72). Therefore, we investigated the expression of Jmjd3 in mouse GCs with respect to age. Our results show that in mice, the expression of Jmjd3 in GCs progressively decreases with age of the animal (Fig. 8A). To determine whether there is a relationship between Jmjd3 expression and reproductive aging in humans, we extended our investigation to human granulosa lutein cells isolated during oocyte retrieval from patients undergoing IVF. Results (Fig. 8B) show that Jmjd3 mRNA levels are significantly lower in granulosa lutein cells from women of advanced age (37-42 years) than in younger women (25-30 years).

Figure 8.

Age-dependent expression of Jmjd3 mRNA. (A) Relative expression of Jmjd3 mRNA levels in mouse granulosa cells (Wt) with respect to age. Data are displayed as means ± SEM (n = 6 for each genotype) and normalized to Rpl19 (*P < .01, vs Wt using Student’s t-test). (B) Relative expression of Jmjd3 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR in human granulosa lutein cells isolated from women of different age groups (25-30 years old and 37-42 years old) undergoing IVF cycle. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 6) and normalized to Rpl19 (*P < .01, vs 25- to 30-year-old age group using Student’s t-test).

Discussion

This study highlights 3 main points. First, the expression and function of JMJD3, a histone demethylase in GCs of follicles, is critical for normal ovarian function and female fertility. Second, it provides an insight into the coordination of nuclear–mitochondrial genomes via epigenetic pathways and its effect on downstream ovarian physiology. Third, our studies show that JMJD3 may be involved in ovarian aging.

Ovarian follicular development is a complex process that involves the establishment of a finite pool of primordial follicles and culminating either in degradation of the follicles through atresia (apoptosis) or in ovulation of a mature oocyte. Previously (6) we reported that the expression of a large number of genes in the GCs critical for female fertility is regulated by decreasing the H3K27me3 gene repressive mark. The targeted disruption of Jmjd3 in GCs now shows for the first time that JMJD3 function within the GCs is a critical mediator of follicle health. The loss of Jmjd3 in GCs leads to (1) reduced number of follicles at an early age that becomes severe progressively with time, (2) increased level of GC apoptosis and follicular atresia, (3) very few corpora lutea reflective of disruptive estrus cycle and ovulatory dysfunction, and (4) reduced responses to FSH and LH, all of which result in subfertility leading to a premature ovarian failure phenotype. Interestingly, the JmjC domain superfamily consists of a diverse range of demethylases that can remove all 3 mono-, di-, and trimethyl groups. Among these proteins, UTX (ubiquitously transcribed X-chromosome tetratricopeptide repeat protein) is very closely related to JMJD3 and can also specifically demethylate H3K27me3 (73). We speculate that, due to this overlapping role of UTX, the ablation of Jmjd3 in GCs, while it disrupts follicular development resulting in subfertility, does not make the animals completely infertile. Moreover, high expression of Jmjd3 also in the oocytes might be another underlying cause of the subfertility rather than a complete infertile phenotype in the GC-Jmjd3KO animals. Development of Jmjd3/Utx double KO mouse in GCs and/or oocytes might result in complete infertility thereby highlighting the overlapping roles of JMJD3 and UTX in both these cell types within the follicle.

At the molecular level, the depletion of Jmjd3 in vivo reveals novel evidence that JMJD3 is essential in the normal functioning of the mitochondria. The importance of the mitochondria in maintaining normal fertility as well as the association of its dysfunction with female sub/infertility and ovarian aging is now well established (21, 71, 74-78). The mitochondrial genome encodes 2 rRNAs, 22 tRNAs, and 37 mRNAs for 13 polypeptides of the oxidative phosphorylation system (79). Out of these 37 mRNAs, ablation of Jmjd3 in GCs decreases the expression of 4 critical mitochondrial genes, mt-Nd3, mt-Nd4l (codes for subunits 3 and 4L of NADH dehydrogenase which form the core subunit of complex I in the mitochondrial membrane respiratory chain) and mt-Tg, mt-Tr (mitochondrially encoded tRNAs that transfer glycine and arginine amino acids, respectively, during translation of the 13 subunits of the electron transport chain). The downregulation of these genes manifest in disruption of the mitochondrial electron transport chain as observed in the Jmjd3 null GCs. Moreover, mtDNA copy number is also significantly decreased in GCs from Jmjd3KO mice, which may further contribute to the increased rate of GC apoptosis in the KO animals.

This study also provides a molecular insight into the role of JMJD3 in the communication between nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. Our studies show that JMJD3-mediated reduction of H3K27me3 occupancy at the promoter region of Lif and Ctnnb1 (β-catenin), induces the expression of these genes. The transcription factor STAT3 is activated by LIF (65, 80) and STAT3 may localize to the mitochondria (81, 82), interact with complex I (83), or bind to mtDNA (63, 84) to increase mitochondrial gene expression (63) as well as modulate the respiratory activity of cells (63). In accordance with the above studies, our results directly link the Jmjd3/H3K27me3/Lif/STAT3 axis to downstream mitochondrial gene expression and activity in GCs, thereby providing a mechanistic understanding of how JMJD3 influences mitochondrial function. The fact that LIF treatment only partially rescues mt-Nd3, mt-Nd4l expression in Jmjd3 null GCs, highlights that JMJD3, through modulation of the H3K27me3 mark, regulates multiple genes/pathways that may have overlapping and/or redundant effects on mitochondrial function. JMJD3/Ctnnb1 (β-catenin) is 1 such possible pathway by which JMJD3 may also regulate mitochondrial gene expression/function. For example, β-catenin has been reported to play a role in mitochondrial function and regulating ATP synthesis in number of different cell types and tissues (68, 69, 85). Our studies also show that Ctnnb1 knockdown decreases mt-Nd3, mt-Nd4l expression in Wt GCs, thereby establishing that, similar to LIF, β-catenin (Ctnnb1) too can regulate mitochondrial gene expression. Moreover, in cancer cells, β-catenin regulates mtDNA levels (67). Given that the mtDNA/nDNA ratio is significantly low in Jmjd3 null GCs, it can be speculated that the regulation of Ctnnb1 (β-catenin) expression by JMJD3 is an underlying mechanism by which mitochondrial biogenesis is regulated in GCs of GC-Jmjd3KO mice.

This concept that JMJD3 is involved in nuclear–mitochondrial crosstalk has been reported in Caenorhabditis elegans and mice, where JMJD2 and JMJD3 induce the expression of UPRmt effectors (mitochondrial unfolded protein response) in the nucleus in response to mitochondrial stress, which in turn modulate mitochondrial function (86). This conserved pathway has been suggested to play a role in determining the rate of aging downstream of mitochondrial dysfunction. Interestingly, the reproductive phenotype along with the ovarian morphology and mitochondrial dysfunction observed in the GC-Jmjd3KO animals are in line with characteristics associated with reproductive aging (70, 87, 88). In females, oocyte competence has primarily been the determining factor for reproductive aging (70, 89, 90) and downregulation of a number of germ-line/oocyte-specific genes (90, 91) or changes in the expression of epigenetic enzymes in the oocytes (70) have been predominantly considered as the underlying mechanism of ovarian aging. However, age-related changes in the GCs or the ovarian micro-environment have a profound effect on oocyte competence that could also push the ovary toward aging. For example, dysregulation of energy homeostasis due to mitochondrial dysfunction generates reactive oxygen species in GCs that have a major impact on ovarian senescence (92). Given the role of JMJD3 in maintaining mitochondrial function in GCs reported here, this study for the first time highlights a potential role of JMJD3 in reproductive aging and implicates the decrease in GC Jmjd3 expression with age as 1 of the probable causes of ovarian dysfunction seen in females of advanced age. A potential role of JMJD3 in the oocytes also cannot be discounted and whether the expression of Jmjd3 also decreases with age in the oocytes and its implication in reproductive aging needs to be investigated.

Interestingly, our studies suggest that GC-Jmjd3KO animals may be born with a diminished ovarian reserve, since the total number of follicles in these animals is significantly lower even at 4 weeks of age. Therefore, the premature ovarian failure (aging) phenotype in GC-Jmjd3KO animals can partially be attributed to diminished ovarian reserve. While further investigation is needed to determine if indeed depletion of Jmjd3 in GCs causes diminished ovarian reserve at birth, there are number of studies that have reported a relationship between diminished ovarian reserve and mitochondrial biogenesis in GCs (93, 94). Moreover, our RNA-seq/qRT-PCR data reveals low expression of Lhx9 and Lif genes, which have been reported to be involved in primordial/primary follicle formation. Lhx9 coding for LIM homeobox protein 9, is a transcription factor for early oogenesis/folliculogenesis (95) while Lif has been shown to play a critical role in primordial to primary follicle transition (96). Moreover, β-catenin, which is also downregulated in GC-Jmjd3KO animals, is expressed in fetal gonads and plays a critical role in gonadal development (97) and folliculogenesis (98). Therefore, it can be speculated that the subfertility and premature ovarian failure phenotype seen in GC-Jmjd3KO animals is a cumulative effect of increased atresia and due to possible low ovarian reserve.

In summary, this study establishes JMJD3, a histone demethylase, as a critical regulator of follicular development that is essential to maintain normal female fertility. We have uncovered that targeted deletion of Jmjd3 in GCs results in downregulation of genes involved in mitochondrial electron transport chain causing dysregulation of mitochondrial function, and lower mtDNA content contributing to accelerated follicular depletion and subfertility, a phenotype similar to that observed in women with premature ovarian failure. In addition, expression of Jmjd3 in GCs decreases with age both in mice and in humans, thereby highlighting a potential role of JMJD3 in female reproductive aging.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nandini Chatterjee for helping with genotyping and Western blot experiments.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- FSH

follicle-stimulating hormone

- GC

granulosa cell

- H3K43

histone 3 at lysine 4

- H3K273

histone 3 at lysine 27

- IVF

in vitro fertilization

- JmjC

Jumonji C

- JMJD3

Jumonji domain–containing protein-3

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TC

theca cell

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling

- wt

wild-type

Financial Support

NIH R01HD086062, USDA-HATCH project MICL02383, Michigan State University-General Funds and MSU AgBioResearch to A.S. and NIH R01GM131398 to J.W.

Disclosure

A.S. and N.G. are listed as co-owners of a US patents related to therapeutic use of AMH for regulation of fertility. N.G. is a shareholder in Fertility Nutraceuticals, LLC, and owner of the Center for Human Reproduction. N.G. receives patent royalties from Fertility Nutraceuticals, LLC. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Das L, Parbin S, Pradhan N, Kausar C, Patra SK. Epigenetics of reproductive infertility. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2017;9(4):509-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jiang SW, Brost B, Dowdy S, Xie X, Jin F. Epigenetic regulation in reproductive medicine and gynecologic cancers. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2010;2010:567260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pan Z, Zhang J, Li Q, et al. Current advances in epigenetic modification and alteration during mammalian ovarian folliculogenesis. J Genet Genomics. 2012;39(3):111-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wiles ET, Selker EU. H3K27 methylation: a promiscuous repressive chromatin mark. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2017;43:31-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ma X, Hayes E, Biswas A, et al. Androgens regulate ovarian gene expression through modulation of Ezh2 expression and activity. Endocrinology. 2017;158(9):2944-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roy S, Huang B, Sinha N, Wang J, Sen A. Androgens regulate ovarian gene expression by balancing Ezh2-Jmjd3 mediated H3K27me3 dynamics. PLoS Genet. 2021;17(3):e1009483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, et al. Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature. 2002;419(6905):407-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cao R, Zhang Y. The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14(2):155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129(4):823-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jamieson K, Rountree MR, Lewis ZA, Stajich JE, Selker EU. Regional control of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Neurospora. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(15):6027-6032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439(7078):811-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647(1-2):21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burchfield JS, Li Q, Wang HY, Wang RF. JMJD3 as an epigenetic regulator in development and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;67:148-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohtani K, Zhao C, Dobreva G, et al. Jmjd3 controls mesodermal and cardiovascular differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2013;113(7):856-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mansour AA, Gafni O, Weinberger L, et al. The H3K27 demethylase Utx regulates somatic and germ cell epigenetic reprogramming. Nature. 2012;488(7411):409-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderton JA, Bose S, Vockerodt M, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase, KDM6B, is induced by Epstein-Barr virus and over-expressed in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncogene. 2011;30(17):2037-2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Hiltunen M, Kauppinen A. Histone demethylase Jumonji D3 (JMJD3/KDM6B) at the nexus of epigenetic regulation of inflammation and the aging process. J Mol Med (Berl). 2014;92(10):1035-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Das ND, Jung KH, Chai YG. The role of NF-kappaB and H3K27me3 demethylase, Jmjd3, on the anthrax lethal toxin tolerance of RAW 264.7 cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tang Y, Li T, Li J, et al. Jmjd3 is essential for the epigenetic modulation of microglia phenotypes in the immune pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(3):369-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hughes FM Jr, Gorospe WC. Biochemical identification of apoptosis (programmed cell death) in granulosa cells: evidence for a potential mechanism underlying follicular atresia. Endocrinology. 1991;129(5):2415-2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong Z, Huang M, Liu Z, et al. Focused screening of mitochondrial metabolism reveals a crucial role for a tumor suppressor Hbp1 in ovarian reserve. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(10):1602-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jorgez CJ, Klysik M, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Matzuk MM. Granulosa cell-specific inactivation of follistatin causes female fertility defects. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(4):953-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boerboom D, Paquet M, Hsieh M, et al. Misregulated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling leads to ovarian granulosa cell tumor development. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9206-9215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeyasuria P, Ikeda Y, Jamin SP, et al. Cell-specific knockout of steroidogenic factor 1 reveals its essential roles in gonadal function. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(7):1610-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sambit Roy NS, Huang B, Cline-Fedewa H, Gleicher N, Wang J, Sen A. Jumonji domain–containing protein-3 (JMJD3/Kdm6b) is critical for normal ovarian function and female fertility. figshare. Deposited February 11, 2022. Doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.19162070.v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Goldman JM, Murr AS, Cooper RL. The rodent estrous cycle: characterization of vaginal cytology and its utility in toxicological studies. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2007;80(2):84-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hernandez Gifford JA, Hunzicker-Dunn ME, Nilson JH. Conditional deletion of beta-catenin mediated by Amhr2cre in mice causes female infertility. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(6):1282-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peluso JJ, Pappalardo A. Progesterone regulates granulosa cell viability through a protein kinase G-dependent mechanism that may involve 14-3-3sigma. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(6):1870-1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sen A, De Castro I, Defranco DB, et al. Paxillin mediates extranuclear and intranuclear signaling in prostate cancer proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2469-2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kano M, Sosulski AE, Zhang L, et al. AMH/MIS as a contraceptive that protects the ovarian reserve during chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(9):E1688-E1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sen A, Hammes SR. Granulosa cell-specific androgen receptors are critical regulators of ovarian development and function. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(7):1393-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pedersen T, Peters H. Proposal for a classification of oocytes and follicles in the mouse ovary. J Reprod Fertil. 1968;17(3):555-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roy S, Gandra D, Seger C, et al. Oocyte-derived factors (GDF9 and BMP15) and FSH regulate AMH expression via modulation of H3K27AC in granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2018;159(9):3433-3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. RRID:AB_2909496. https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_2909496&l=AB_2909496 [Google Scholar]

- 35. RRID:AB_2848134. https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_2848134&l=AB_2848134 [Google Scholar]

- 36. RRID:AB_2909630. https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_2909630&l=AB_2909630 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Evaul K, Hammes SR. Cross-talk between G protein-coupled and epidermal growth factor receptors regulates gonadotropin-mediated steroidogenesis in Leydig cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(41):27525-27533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sinha N, Roy S, Huang B, Wang J, Padmanabhan V, Sen A. Developmental programming: prenatal testosterone-induced epigenetic modulation and its effect on gene expression in sheep ovary†. Biol Reprod. 2020;102(5):1045-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_10622025&l=AB_10622025 RRID:AB_10622025.

- 40.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_10828597&l=AB_10828597 RRID:AB_10828597.

- 41.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_10695870&l=AB_10695870 RRID:AB_10695870.

- 42.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_10835694&l=AB_10835694 RRID:AB_10835694.

- 43.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_331476&l=AB_331476 RRID:AB_331476.

- 44.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_2491009&l=AB_2491009 RRID:AB_2491009.

- 45.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_331757&l=AB_331757 RRID:AB_331757.

- 46.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_2616029&l=AB_2616029 RRID:AB_2616029.

- 47.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_331563&l=AB_331563 RRID:AB_331563.

- 48.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_11152046&l=AB_11152046 RRID:AB_11152046.

- 49.https://scicrunch.org/resources/Antibodies/search?q=AB_11127855&l=AB_11127855 RRID:AB_11127855.

- 50. Saben JL, Boudoures AL, Asghar Z, et al. Maternal metabolic syndrome programs mitochondrial dysfunction via germline changes across three generations. Cell Rep. 2016;16(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang RS, Chang HY, Kao SH, et al. Abnormal mitochondrial function and impaired granulosa cell differentiation in androgen receptor knockout mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):9831-9849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu X, Trakooljul N, Hadlich F, Murani E, Wimmers K, Ponsuksili S. Mitochondrial-nuclear crosstalk, haplotype and copy number variation distinct in muscle fiber type, mitochondrial respiratory and metabolic enzyme activities. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ma X, Hayes E, Prizant H, Srivastava RK, Hammes SR, Sen A. Leptin-induced CART (Cocaine- and Amphetamine-Regulated Transcript) is a novel intraovarian mediator of obesity-related infertility in females. Endocrinology. 2016;157(3):1248-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liang S, Yao Q, Wei D, et al. KDM6B promotes ovarian cancer cell migration and invasion by induced transforming growth factor-β1 expression. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(1):493-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mo J, Wang L, Huang X, et al. Multifunctional nanoparticles for co-delivery of paclitaxel and carboplatin against ovarian cancer by inactivating the JMJD3-HER2 axis. Nanoscale. 2017;9(35): 13142-13152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sakaki H, Okada M, Kuramoto K, et al. GSKJ4, A Selective Jumonji H3K27 demethylase inhibitor, effectively targets ovarian cancer stem cells. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(12):6607-6614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roudebush WE, Kivens WJ, Mattke JM. Biomarkers of ovarian reserve. Biomark Insights. 2008;3:259-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jiao X, Meng T, Zhai Y, et al. Ovarian reserve markers in premature ovarian insufficiency: within different clinical stages and different etiologies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:601752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang D, Liu Y, Zhang Z, et al. Basonuclin 1 deficiency is a cause of primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27(21):3787-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cardol P, Lapaille M, Minet P, Franck F, Matagne RF, Remacle C. ND3 and ND4L subunits of mitochondrial complex I, both nucleus encoded in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, are required for activity and assembly of the enzyme. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5(9):1460-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sarzi E, Brown MD, Lebon S, et al. A novel recurrent mitochondrial DNA mutation in ND3 gene is associated with isolated complex I deficiency causing Leigh syndrome and dystonia. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(1):33-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Grosso S, Carluccio MA, Cardaioli E, et al. Complex I deficiency related to T10158C mutation ND3 gene: A further definition of the clinical spectrum. Brain Dev. 2017;39(3):261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Carbognin E, Betto RM, Soriano ME, Smith AG, Martello G. Stat3 promotes mitochondrial transcription and oxidative respiration during maintenance and induction of naive pluripotency. EMBO J. 2016;35(6):618-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pastuschek J, Poetzsch J, Morales-Prieto DM, Schleußner E, Markert UR, Georgiev G. Stimulation of the JAK/STAT pathway by LIF and OSM in the human granulosa cell line COV434. J Reprod Immunol. 2015;108:48-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Onishi K, Zandstra PW. LIF signaling in stem cells and development. Development. 2015;142(13):2230-2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mezhybovska M, Yudina Y, Abhyankar A, Sjölander A. Beta-catenin is involved in alterations in mitochondrial activity in non-transformed intestinal epithelial and colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(9):1596-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vergara D, Stanca E, Guerra F, et al. β-catenin knockdown affects mitochondrial biogenesis and lipid metabolism in breast cancer cells. Front Physiol. 2017;8:544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Balatskyi VV, Vaskivskyi VO, Myronova A, et al. Cardiac-specific β-catenin deletion dysregulates energetic metabolism and mitochondrial function in perinatal cardiomyocytes. Mitochondrion. 2021;60:59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lehwald N, Tao GZ, Jang KY, et al. β-Catenin regulates hepatic mitochondrial function and energy balance in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):754-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chamani IJ, Keefe DL. Epigenetics and female reproductive aging. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Keefe DL, Niven-Fairchild T, Powell S, Buradagunta S. Mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid deletions in oocytes and reproductive aging in women. Fertil Steril. 1995;64(3):577-583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Eichenlaub-Ritter U, Vogt E, Yin H, Gosden R. Spindles, mitochondria and redox potential in ageing oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2004;8(1):45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Swigut T, Wysocka J. H3K27 demethylases, at long last. Cell. 2007;131(1):29-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhang M, Bener MB, Jiang Z, et al. Mitofusin 1 is required for female fertility and to maintain ovarian follicular reserve. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(8):560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Conca Dioguardi C, Uslu B, Haynes M, et al. Granulosa cell and oocyte mitochondrial abnormalities in a mouse model of fragile X primary ovarian insufficiency. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22(6):384-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang M, Bener MB, Jiang Z, et al. Mitofusin 2 plays a role in oocyte and follicle development, and is required to maintain ovarian follicular reserve during reproductive aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(12):3919-3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Benkhalifa M, Ferreira YJ, Chahine H, et al. Mitochondria: participation to infertility as source of energy and cause of senescence. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;55:60-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chiang JL, Shukla P, Pagidas K, et al. Mitochondria in ovarian aging and reproductive longevity. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;63:101168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. D’Souza AR, Minczuk M. Mitochondrial transcription and translation: overview. Essays Biochem. 2018;62(3):309-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Schuringa JJ, van der Schaaf S, Vellenga E, Eggen BJ, Kruijer W. LIF-induced STAT3 signaling in murine versus human embryonal carcinoma (EC) cells. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274(1): 119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wegrzyn J, Potla R, Chwae YJ, et al. Function of mitochondrial Stat3 in cellular respiration. Science. 2009;323(5915):793-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Meier JA, Larner AC. Toward a new STATe: the role of STATs in mitochondrial function. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(1):20-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lahiri T, Brambilla L, Andrade J, Askenazi M, Ueberheide B, Levy DE. Mitochondrial STAT3 regulates antioxidant gene expression through complex I-derived NAD in triple negative breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(5):1432-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Macias E, Rao D, Carbajal S, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J. Stat3 binds to mtDNA and regulates mitochondrial gene expression in keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(7):1971-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wang Z, Havasi A, Gall JM, Mao H, Schwartz JH, Borkan SC. Beta-catenin promotes survival of renal epithelial cells by inhibiting Bax. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(9):1919-1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Merkwirth C, Jovaisaite V, Durieux J, et al. Two conserved histone demethylases regulate mitochondrial stress-induced longevity. Cell. 2016;165(5):1209-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yang L, Lin X, Tang H, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutation exacerbates female reproductive aging via impairment of the NADH/NAD+ redox. Aging Cell. 2020;19(9):e13206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kirkwood TB. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell. 2005;120(4):437-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Igarashi H, Takahashi T, Nagase S. Oocyte aging underlies female reproductive aging: biological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Reprod Med Biol. 2015;14(4):159-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sharov AA, Falco G, Piao Y, et al. Effects of aging and calorie restriction on the global gene expression profiles of mouse testis and ovary. BMC Biol. 2008;6:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hamatani T, Falco G, Carter MG, et al. Age-associated alteration of gene expression patterns in mouse oocytes. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(19):2263-2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Tatone C, Amicarelli F. The aging ovary – the poor granulosa cells. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(1):12-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Boucret L, Chao de la Barca JM, Morinière C, et al. Relationship between diminished ovarian reserve and mitochondrial biogenesis in cumulus cells. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(7):1653-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Li H, Wang X, Mu H, et al. Mir-484 contributes to diminished ovarian reserve by regulating granulosa cell function via YAP1-mediated mitochondrial function and apoptosis. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18(3):1008-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pangas SA, Rajkovic A. Transcriptional regulation of early oogenesis: in search of masters. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(1): 65-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nilsson EE, Kezele P, Skinner MK. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) promotes the primordial to primary follicle transition in rat ovaries. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;188(1-2):65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Liu CF, Bingham N, Parker K, Yao HH. Sex-specific roles of beta-catenin in mouse gonadal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(3):405-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hernandez Gifford JA. The role of WNT signaling in adult ovarian folliculogenesis. Reproduction. 2015;150(4):R137-R148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.