Abstract

This study tested a model wherein the family conflict, depression, and antisocial behavior of 254 adolescents (mean age = 17 years; 63% female) are prospectively related to functioning within a marital (51%) or dating relationship in young adulthood (mean age = 23 years). Family aversive communication in adolescence and adolescent antisocial behavior predicted couple physical aggression. Family aversive communication predicted dyadic satisfaction and aversive couple communication for married women and dating men. Among those with partners who reported little antisocial behavior, adolescent antisocial behavior inversely predicted couple satisfaction and facilitative behavior. Partner antisocial behavior did not mediate the relation between adolescent characteristics and couple functioning. Findings emphasize the importance of the early family environment and psychopathology of the adolescent in the development of adaptive couple relationships.

Conflictual romantic relationships are prevalent and costly, both to the individual and to society. Prevalence estimates from community (Elliott, Huizinga, & Morse, 1986; O’Leary et al., 1989) and college samples (Sugarman & Hotaling, 1989) indicate that about one third to one half of all respondents engage in physical aggression against their partners. Rates of physical aggression are particularly high in the early 20s, when dating is most frequent (O’Leary, Malone, & Tyree, 1994). From a social learning and social interactional perspective, the origins of conflictual young adult relationships most likely occur in childhood or adolescence, as youngsters acquire a repertoire of behaviors for managing their relationships in the family and subsequently with dating partners. In the present study, we proposed and tested a model wherein an adolescent’s antisocial behavior, depression, and conflict in the family of origin relate prospectively to four aspects of couple relationships in young adulthood: the dyad’s satisfaction, their observed facilitative and aversive communication during a problem-solving interaction, and their reported physical aggression. We also examined the role of the antisocial behavior of participants’ partners in young adulthood, both as an independent predictor of couple functioning and as a possible mediator or moderator of the roles of adolescent depressive symptoms, family conflict, and antisocial behavior (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The theoretical relation between adolescent predictors and young adult adjustment, a = mediating effect of partner antisocial behavior; b = moderating effect of partner antisocial behavior; c = moderating effect of gender and marital status.

In a study of couples in marital treatment, Cascardi and Vivian (1995) concluded that most cases of physical aggression appeared to be due to engagement in conflict by both partners. This conclusion is supported by findings from studies showing that couple relationships are both dyadic and reciprocal (Bookwala, Frieze, Smith, & Ryan, 1992; Foo & Margolin, 1995; Gwartney-Gibbs, Stockard, & Bohmer, 1987; Sugarman & Hotaling, 1989). Thus, the focus of this study was on the functioning of the couple rather than individual members of the dyad.

With few exceptions (e.g., Capaldi & Clark 1998; Capaldi & Crosby, 1997; Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Simons, 1998; Simons, Wu, Johnson, & Conger, 1995), most previous studies have used retrospective reports from a single respondent to examine the predictors of dysfunctional couple relationships. Capaldi’s work, an important exception, prospectively predicted the functioning of dating couples using multimethod data collected on men, beginning when they were boys in the fourth grade. These data are limited, however, in that, whereas measures of couple functioning were obtained from both members of the dyad, child and adolescent measures were obtained only from men. The present study expanded the work of Capaldi and associates by including measures obtained in adolescence from both men and women to predict couple functioning of these individuals prospectively in young adulthood.

Examining the relation of adolescent antisocial behavior and subsequent couple dysfunction is well justified. Several studies have suggested continuity in antisocial behavior from early childhood through adulthood (Loeber, 1982; Olweus, 1979). According to Riggs and O’Leary’s (1989) model of dating violence, individuals with a history of aggression with others are more likely to aggress against a date. Supporting this model of aggression, retrospective studies showed a relation between early antisocial behavior (Bookwala et al., 1992; Riggs, 1993) and delinquency (Malamuth, Sockloskie, Koss, & Tanaka, 1991) and subsequent couple aggression, with a stronger relation for men than for women (Riggs, O’Leary, & Bresline, 1990). In prospective studies, Capaldi and Clark (1998) and Gorman-Smith and Tolan (1998) found relations between antisocial behavior in adolescence and subsequent aggression to partner.

Both social learning theory and coercion theory predict an association between conflict within the family during adolescence and a conflictual dyadic relationship in young adulthood. Social learning theory predicts that behavior patterns learned in childhood or adolescence are practiced during courtship and marriage. Coercion theory (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992; Snyder, 1995) predicts that ineffective parental management styles and subsequent coercive parent–child interactions produce coercive, unskilled responses to peers and subsequently to partners. Retrospective studies have provided empirical support for the theoretical relation between early family relationships and dating and marital dysfunction, showing that parental aggression toward the child (Malamuth et al., 1991; Riggs et al., 1990) and witnessing aggression between parents (Kalmuss, 1984) are major precursors to dating aggression.

Our model included depression in adolescence as a predictor of couple functioning. Depression is associated both with dysfunctional family relationships characterized by low family support, lack of approval, and conflictual family interactions (Cole & McPherson, 1993; Hops, Lewinsohn, Andrews, & Roberts, 1990; Sheeber, Hops, Alpert, Davis, & Andrews, 1997; Stark, Humphrey, Crook, & Lewis, 1990) and with antisocial behavior (Capaldi, 1992; Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991). Further, depression is a frequent correlate of distressed and conflictual relationships among dating and married couples (Biglan et al., 1985; Cascardi, O’Leary, Lawrence, & Schlee, 1995), particularly for women (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997), and studies suggest that depression may precede the dysfunctional relationship (Cascardi et al., 1995).

We included partner antisocial behavior in our model because couple functioning is dependent on both members of the dyad. We speculated that the antisocial behavior of the partner might not only be an independent predictor of couple functioning but also might mediate and/or moderate the relation between adolescent characteristics and couple functioning. Our hypothesis regarding mediation is derived from the literature on assortative mating, which posits that individuals select a mate with similar characteristics (Caspi & Herbener, 1990; Elder, Caspi, & Downey, 1986; Quinton, Pickles, Maughan, & Rutter, 1993), Thus, as Caspi and Herbener (1990) suggested, an antisocial or depressed individual might select an antisocial partner who in turn might reinforce the dysfunctional behavior of the adolescent, thus encouraging the continuity of this behavior. Alternatively, the level of partner antisocial behavior may moderate the relationship in that romantic involvement with a prosocial partner might weaken the link between adolescent and young adult dysfunction. Quinton and colleagues (Pickles & Rutter, 1991; Quinton et al., 1993) showed that the presence of a nondeviant partner promoted a switch out of maladaptive functioning into more adaptive functioning in both at-risk and normal populations. Alternatively, a partner with high antisocial behavior might amplify the effect of the adolescent’s antisocial behavior on the functioning of the couple.

Although couple aggression is one important marker of couple dysfunction, it is not the only indicator of a potentially troubled relationship. Several studies show an inverse relation between the extent of couple physical aggression and both couple satisfaction (Makepeace, 1987; Marshall & Rose, 1987) and couple communication (Cordova, Jacobson, Gottman, Rushe, & Cox, 1993; Margolin, John, & Gleberman, 1988). Further, couple communication skills correlate with marital satisfaction (e.g., Margolin & Wampold, 1981) and longitudinally predict declines in marital satisfaction and marital stability (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Thus, we included measures of couple satisfaction and examined couple aversive and facilitative behavior observed in each couple’s discussion of a conflictual issue as indicators of their communication skills.

This study extended and improved on past studies in several ways. First, the study drew from a community sample. Second, the study was prospective, beginning when the participants were in high school and following them into young adulthood. A third major improvement was the multisource, multimethod data, which included clinical interviews, questionnaires, and direct observation. A final strength of the study was the relatively large sample, which allowed us to examine the roles of gender and marital status (married vs. dating) in predicting couple dysfunction. Studies noting substantial gender differences in correlates of satisfaction and violence (e.g., Foo & Margolin, 1995; Gwartney-Gibbs et al., 1987; Markman, Silvern, Clements, & Kraft-Hanak, 1993) substantiate the importance of examining gender. Theoretical views such as feminist theory (e.g., Saunders, 1986) also argue that aggression in young adulthood would be more strongly predicted by the antisocial behavior in adolescence of boys than by the antisocial behavior of girls. Marital status was important to consider in light of numerous studies showing that dyadic satisfaction declines and dyadic conflict, violence, and abuse increase as a function of the couple’s level of commitment (Arias, Samios, & O’Leary, 1987; Belknap, 1989; Stets & Pirog-Good, 1990) and the length of their relationship (Arias et al., 1987; Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Capaldi & Crosby, 1997; Kurdek, 1998; Stets & Pirog-Good, 1990).

This study tested a prospective model of the relation of adolescent characteristics to the quality of couple relationships as a function of gender and marital status. We hypothesized that family conflict in adolescence, adolescent antisocial behavior, and adolescent depressive symptoms would predict couple functioning. The antisocial behavior of the partner was also expected to predict couple dysfunction, moderating and/or mediating the effects of adolescent characteristics on couple functioning.

Method

Participants

As part of an epidemiological study of depression in midadolescence (Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley, & Andrews, 1993), a representative community sample of 716 adolescents (mean age = 16.8 years; 55% female, n = 391) and their parents from six high schools in two urban communities in western Oregon participated at Time 1 (T1) of the investigation. The T1 sample was part of a larger random sample stratified by school, grade, and gender that was recruited from high school populations in two urban and three rural communities (see Lewinsohn et al., 1993, for a detailed description). Participants from the urban communities in this random sample were later asked to participate in a second study requiring additional assessments (the present study). Sixty percent of those contacted agreed to participate in the second study. A comparison of participants in the second study with those who declined revealed no significant differences on demographic variables, measures of family relationships, or measures of adolescent psychopathology. These adolescents were representative of adolescents in their respective communities (see Hops & Seeley, 1992, for additional details).

The adolescents who provided T1 data for the present study were reassessed the following year (Time 2 [T2]); however, these data are not relevant to the analyses reported here. Six years after the T1 assessment (Time 3 [T3]), 604 participants (58% female, n = 349) were again assessed at ages 20 to 24 (mean age = 23.1 years). A comparison of those who completed both the T1 and T3 assessment with those who completed only the T1 assessment revealed no differences in age, the level of education of either parent, or whether or not they resided in a single-parent household in high school. However, those who participated in the T3 assessment were more likely to be a Caucasian than a minority, χ2(1, N = 716) = 8.84, p < .01, and more likely to be female, χ2(1, N = 716) = 21.86, p < .001, than those who did not.

Of the 604 participants completing both the T1 and T3 assessments, 365 (130 men, 235 women) had a romantic partner (i.e., reported being married, engaged, living together, or having dated the partner for at least 1 month) of the opposite gender, who also completed part or all of the assessment battery at T3.1 Of the 365 participants with an opposite-gender romantic partner, 153 (42%) were married, 49 (14%) were living together but were not married, 161 (44%) were dating, and 2 (1%) did not indicate their relationship with their partner. Those with an opposite-gender romantic partner did not differ from those without a partner in age; race; education of parents; living situation (e.g., living with parents) in adolescence; or measures of adolescent depression, adolescent antisocial behavior, or family conflict. However, women were significantly more likely to have a romantic opposite-gender partner than were men, χ2(1, N = 604) = 10.54, p < .001.

The T3 sample contained 314 respondents who were dating or married at the time of the young adult assessment.2 Of these, 254 had complete data for the T1 predictor measures and at least one of the T3 measures of partner antisocial behavior used in this study. Those with and without complete data on the predictor variables did not differ on age at T1, gender, race, or any of the predictor variables that were not missing.

At the adolescent assessment (T1), the participants used in the present study were an average 16.70 years old (SD = 1.27); 93% were Caucasian, 63% were female, 74% had mothers and 78% had fathers with more than a high school education, and 23% lived in a single-parent household. At the young adult assessment (T3), the participants were an average 22.51 years old (SD = 1.31) and 51% were married. A small proportion of participants (5%) had not graduated from high school, 25% had completed only high school, and the remainder had some trade school or college education. The married couples were married an average of 2.18 years (SD = 1.58), and dating couples were dating an average of 1.65 years (SD = 1.75). Partners involved in the young adult assessment ranged in age from 17 to 37 years (M = 24.18. SD = 3.18); 92% were Caucasian, 3% had not completed high school, 23% had completed only high school, and the remainder had some higher education.

Assessment Procedures

At T1, parents and adolescents completed a battery of questionnaires, adolescents participated in a structured diagnostic interview, and parents and adolescents participated in two 10-min problem-solving interactions that were videotaped for later coding. Six years later, at T3, target young adults and a mate or romantic partner identified by the target young adult completed a battery of questionnaires. Young adults living within 100 mi (160 km) of the research institute were asked to complete questionnaires at the institute and to participate in two 10-min videotaped problem-solving interactions with these opposite-gender partners. If the couple lived more than 100 mi (160 km) from the institute, they completed questionnaires by mail. Among those married and dating young adults whose opposite-gender partners completed questionnaires (n = 254), 135 (53%) participated in the interaction task. Most of the 119 young adults who did not participate in the interaction task lived out of the area (81%, n = 96). A small proportion declined to participate because they did not have time (9%), did not want to be videotaped (5%), or gave other reasons for not participating in the interaction task (6%). Couples with and without observational data did not differ significantly on any of the predictor or criterion variables used in this study. Nor did they differ in age of the target adolescent at T1, mother education, or target education at T3. Those without observational data did, however, have more educated fathers at T1 than those who participated in the observations, t(175) = −2.01, p < .05.

Measures

Predictor variables based on the T1 assessment included measures of adolescent depressive symptoms, family conflict, and adolescent antisocial behavior. We also included partner antisocial behavior assessed at T3 as a predictor variable. Criterion variables collected at T3 assessed four dimensions of couple functioning: couple satisfaction/adjustment, couple aversive communication and facilitative communication, and physical aggression in the relationship. We included variables assessed with different methods at T1 to index each T1 construct examined in this study. Because some of the criterion variables at T3 involved self-report questionnaires completed by the target participant, we did not use T1 variables based on adolescent self-report questionnaires to avoid shared method variance as an explanation for significant correlations. Instead, T1 variables were based on parent report, diagnostic interviews scored by the interviewer, and direct observations of family communication.

T1 parent questionnaire measures.

Parents completed both the Anxiety/Depression and the Delinquency subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) as measures of the adolescent’s depression and antisocial behavior. Internal consistencies in this sample for these subscales were .87 and .88 for mother and father scores, respectively, on the Anxiety/Depression subscale and .79 for both mother and father scores on the Delinquency subscale. Parents completed a subscale consisting of seven items selected from the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Prinz, Foster, Kent, & O’Leary, 1979) and five items from the Cohesion subscale of the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos, 1974) as a measure of parent–adolescent conflict. Previous psychometric work (Andrews, Lewinsohn, Hops, & Roberts, 1993) supported the use of this score as an assessment of parent–adolescent conflict. Internal consistencies of these mother and father conflict scales in this sample were .71 and .75, respectively. Parents also completed the Issues Checklist (Prinz et al., 1979) as a measure of parent–adolescent conflict. The Issues Checklist contains a list of 44 possible topics about which parents and adolescents could disagree. Parents and adolescents independently indicate which topics arose, how often they discussed each in the past 2 weeks, and the anger levels of those discussions. Average anger intensity scores were used in this study. These scores discriminate distressed from nondistressed adolescents and parents and correlate negatively with observed problem solving between parents and adolescents (Robin & Foster, 1989). When both parents provided data, we averaged the mother’s and father’s report on each of these measures to provide an index of parental perceptions. When only 1 parent provided data (e.g., single-parent families), the variable consisted of the report of the participating parent. This not only allowed us to deal with missing data to maximize the sample size but also resulted in a measure that was more reliable than data from a single source (Strahan, 1980).

Diagnostic interview.

Adolescents were interviewed at T1 with a version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K–SADS) that combined features of the Epidemiologic version (K–SADS–E; Orvaschel, Puig-Antich, Chambers, Tabrizi, & Johnson, 1982) and the Present Episode version and included all the symptoms for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., rev.; DSM–III–R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) or DSM (4th ed., American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnoses of conduct disorders. A score representing lifetime symptoms of conduct disorder was used as a measure of adolescent antisocial behavior. As a measure of depression, the interviewers completed a 14-item version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960) for any current or past episode of depression, following the procedures developed by Endicott, Cohen, Nee, Fleiss, and Sarantakos (1981). They based their ratings on responses to the depression items on the K–SADS–E. The current depressive symptom score from the HRSD was used in this study.

As described by Lewinsohn et al. (1993), all the interviews were videotaped and reliability ratings were obtained on a randomly selected 12% by an experienced interviewer. In addition, a child psychiatrist who was unaware of other indicators of the participants’ diagnosis provided symptom ratings and diagnoses for participants over time. Kappas for several diagnoses (including conduct disorder and major depression) were equal to or greater than .80. The degree of agreement between the symptom ratings of the interviewers and the child psychiatrist on the videotaped cases was reflected in an average kappa of .83 (see Lewinsohn et al., 1993, for more information regarding interviewer training and procedures).

Problem-solving interactions.

Topics for the parent–child interactions were identified using parent and adolescent responses on the Issues Checklist (Prinz et al., 1979), a list of 44 topics about which adolescents and parents frequently disagree. Topics for the problem-solving interactions with opposite-gender partners were chosen from a list of 15 issues from the DAS (Spanier, 1976) about which partners typically disagree. The topics chosen were those that both participants (e.g., the adolescent and his or her parent or both members of the couple) identified as areas of conflict. Participants were asked to discuss and try to resolve each of the issues (see Hops & Seeley, 1992. for a more detailed presentation of assessment procedures).

Trained observers coded the interactions between the adolescent and their parents during the problem-solving discussions at T1 and the interactions between target young adult and their partner at T3 using the Living in Family Environments (LIFE; Hops, Biglan, Tolman, Arthur, & Longoria, 1995) coding system. Numerous studies support the construct, discriminant, and concurrent validity of the LIFE coding system (see Hops, Davig, & Longoria, 1995, for review). Using the LIFE coding system, consisting of 8 affect and 22 verbal content codes, observers recorded the behavior of each participant in real time. Two constructs were used in the present investigation: the number of aversive behaviors per minute (rate per minute) and the rate per minute of facilitative behavior displayed by each of the participants. Both affect and content were used to code each behavior. Aversive behavior was a composite that included all content codes accompanied by aversive affect (e.g., irritability), as well as statements coded as disapproving, threatening, or argumentative.3 The facilitative behavior composite included all codes with happy or caring affect, as well as all approving or affirming statements and statements that serve to maintain the conversation.

Twenty percent of the videotapes were randomly selected and coded by a second observer for reliability purposes. The intraclass correlations for aversive behavior and facilitative behavior between adolescents and their parent at T1 for the subsample who had dating or marital partners at T3 were .68 and .61 for adolescent and parent aversive behavior, respectively, and .89 and .90 for adolescent and parent facilitative behavior, respectively, indicating adequate interobserver agreement (Hartmann & Wood, 1982). The intraclass correlations for the interactions between the target young adults and their partners indicated good interobserver agreement (.81 and .83 for participant and partner aversive behavior, respectively, and .81 and .82 for participant and partner facilitative behavior, respectively).

T3 questionnaire measures.

As a measure of couple satisfaction, both young adults and their partners completed the DAS (Spartier, 1976). The DAS assesses the quality of dyadic satisfaction, dyadic cohesion, dyadic consensus, and affectional expression. The DAS discriminates between divorced and married couples, correlates with other measures of marital satisfaction, and has satisfactory internal consistency reliability (Spanier, 1976). For this sample, the internal consistency reliability was .94 for the target young adults and .92 for their partners.

The presence of physical aggression in the relationship was measured using the Violence subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979), which assesses the frequency of seven acts of physical aggression given to and received from the partner. If either partner indicated giving or receiving a physically aggressive act, this act was scored as occurring in the relationship. Within this sample, 25% threatened to hit or throw something at their partner; 21% threw something at their partner; 33% pushed, shoved, or grabbed their partner; 22% hit or tried to hit their partner; 6% hit or tried to hit their partner with a hard object; 2% threatened their partner with a knife or gun; and 2% used a knife or gun against their partner.

Similar to previous studies (DeMaris, 1987; Heyman & Schlee, 1997; Kalmuss & Straus, 1982), we dichotomized physical aggression (i.e., present vs. absent). If either partner indicated giving or receiving any physically aggressive act, physical aggression was scored as present in the relationship. This was also necessary to deal with the highly skewed distribution of the physical aggression variable when scored as a continuous variable, which resulted in major violations of the homoscedasticity assumption of multiple regression—a problem that various transformations failed to alleviate.4 According to this criterion, 47% of the married couples and 37% of the dating couples reported some physical aggression in their relationship. Agreement (kappa; Cohen, 1960) between partners on whether any physical aggression had occurred in the relationship was .49. Reciprocity of physical aggression was reasonably high, with a phi correlation of .61 (p < .001) between aggression directed toward one member of the dyed (scored “yes” if either reported any form of physical aggression) with aggression toward the other member of the dyad, supporting our conceptualization of physical aggression as reciprocal and dyadic.

As measures of antisocial behavior, the young adult’s partner completed the Self-Report of Delinquency Scale (Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985), reporting on the frequency of 20 activities that may be against the rule or law, and the Delinquency subscale from the Young Adult Self-Report (YASR; Achenbach, 1991), an extension of the Youth Self-Report (Acbenbach, 1991). Internal consistencies for the present sample were .64 for the Self-Report of Delinquency Scale and .68 for the YASR Delinquency subscale.

Results

Descriptive Information

Means and standard deviations of each measure of family conflict, adolescent antisocial behavior, adolescent depression, partner antisocial behavior, and each of the T3 criterion variables within the sample are shown in Table 1. An examination of these means suggests that this sample is similar to other normative and community/nonclinic samples on T1 and T3 variables for which such data are available (e.g., Acbenbach, 1991, 1997; Lewinsohn et al., 1993; Spanier, 1976; Straus, 1979). On the basis of the t scores (averaged across parents) on the CBCL Delinquency and Anxiety/Depression subscales, a small percentage of the adolescents were above the cutoff (67) for clinical depression (5%) and delinquency (8%; Achenbach, 1991). On the basis of average couple scores on the DAS, 10% of the couples were distressed, with scores of 100 or less.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Predictor and Criterion Measures

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | ||

| Family conflict | ||

| CBQ and FES Cohesion subscalea | 1.54 | 1.77 |

| Issues Checklista | 1.54 | 0.50 |

| Observed family aversive communicationb | 0.20 | 0.40 |

| Adolescent depression | ||

| CBCL Anxiety/Depression subscalea | 3.57 | 3.80 |

| HRSDc | 1.28 | 3.31 |

| Adolescent antisocial behavior | ||

| CBCL Delinquency subscalea | 1.87 | 2.68 |

| Lifetime conduct disorders (interview) | 0.45 | 0.85 |

| Partner antisocial behavior | ||

| YASR Delinquency subscaled | 1.43 | 1.42 |

| Self-Report of Delinquency Scaled | 4.48 | 6.37 |

| Criterion | ||

| Couple satisfaction (DAS)e | 116.72 | 14.81 |

| Observed couple aversive communicationb | 0.38 | 0.43 |

| Observed couple facilitative communicationb | 3.11 | 1.05 |

| Occurrence of couple physical aggression (CTS) | 0.42 | 0.49 |

Note. CBQ = Conflict Behavior Questionnaire; FES = Family Environment Scale; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; YASR = Young Adult Self-Report; DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale; CTS = Conflict Tactics Scale.

Parent report.

Rate per minute.

Interviewer rating.

Partner report.

Average across couples.

Correlations Among Variables and Creation of Composites

To reduce the number of variables included in the analyses and to increase the reliability of our adolescent measures, we created composites from those T1 variables hypothesized to measure the same construct if their intercorrelation equaled or exceeded .30. The resulting composites, calculated by averaging the standardized variables included in the composite, were as follows: parent–adolescent conflict, a combination of the parent report on the Issues Checklist and the parent report on the FES Cohesion/CBQ scale (r = .36, p < .001); adolescent antisocial behavior, a combination of the parent report on the CBCL Delinquency subscale and the interviewer’s recording of the adolescent’s lifetime incidence of symptoms of conduct disorder from the KSADS–E (r = .54, p < .001); and partner antisocial behavior, the combination of partners’ self-report on the Self-Report of Delinquency Scale and partners’ self-report on the YASR Delinquency subscale (r = .34, p < .001). Because observed family aversive communication at T1 did not correlate highly with the other measures of family conflict (r = .25, p < .001, with the FES Cohesion/CBQ scale; r = .18, p < .01, with the Issues Checklist), we retained family aversive communication as a separate predictor. Similarly, parent rating on the CBCL Anxiety/Depression subscale correlated only .26 (p < .001) with interviewer ratings on the HRSD, so we retained both variables as separate predictors. Therefore, we had six predictor variables: (a) parent reports of parent-adolescent conflict, (b) observed family aversive communication, (c) parent report of adolescent depression, (d) interviewer rating on the HRSD, (e) adolescent antisocial behavior, and (f) partner antisocial behavior.

Table 2 shows the correlations among predictor and criterion variables. As expected from the literature, the correlations among the T1 predictor constructs and variables and among the T3 criterion variables were low to moderate. Several of the univariate correlations between family aversive communication, parent–adolescent conflict, adolescent and partner antisocial behavior, and the criterion variables were significant, albeit small. The univariate correlations between the two measures of depression and the criterion variables were not significant.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Predictors and Criterion Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | ||||||||||

| 1. Parent–adolescent conflict | — | |||||||||

| 2. Family aversive communication | .26*** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Parent-rated depression | .38*** | .02 | — | |||||||

| 4. HRSD | .06 | .06 | .26*** | — | ||||||

| 5. Adolescent antisocial behavior | .36*** | .08 | .48*** | .19** | — | |||||

| 6. Partner antisocial behavior | .15* | −.02 | .01 | −.05 | .07 | — | ||||

| Criterion variables | ||||||||||

| 7. Couple satisfaction | −.15 | −.23*** | −.04 | −.02 | −.13* | −.27*** | — | |||

| 8. Couple aversive communication | .17* | .18* | .09 | .04 | .13 | .04 | −.44*** | — | ||

| 9. Couple facilitative communication | −.20* | −.12 | −.10 | −.09 | −.12 | .06 | .35*** | −.50*** | — | |

| 10. Couple physical aggression | .09 | .22*** | .08 | −.02 | .20* | .14* | − 36*** | .20* | −.18* | — |

Note. HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Overview of Data Analysis

We predicted couple satisfaction, couple aversive communication, and couple facilitative communication using hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses and predicted presence or absence of couple physical aggression using logistic regression. All the predictors were centered using procedures described by Aiken and West (1991) to maximize interpretability of interactions and to minimize problems associated with collinearity. Additionally, dummy coding was used for gender (0 = female, 1 = male) and marital status (0 = married, 1 = dating). We found no evidence of multicollinearity among predictor variables or violations of other assumptions of regression, except as described below.

The main effects of gender and marital status and the two- and three-way interactions of each of these variables and their combination with each predictor variable and partner antisocial behavior resulted in a large number of potential predictors. To limit the number of interactions included in our final hypothesis-testing regression analyses, we initially examined main and interaction effects of gender and marital status in separate preliminary regressions for each T1 predictor.5 In each of these preliminary analyses, variables were entered in the following order: (a) marital status or gender; (b) the interaction of gender and marital status; (c) the T1 predictor; (d) partner antisocial behavior; (e) the interaction of partner antisocial behavior with the T1 predictor and the two-way interactions of marital status and gender with the T1 predictor and partner antisocial behavior; and (f) the three-way interactions between marital status, gender, and the T1 predictor and partner antisocial behavior, the three-way interactions between partner antisocial behavior, marital status, and the T1 predictor, and the three-way interactions between partner antisocial behavior, gender, and the T1 predictor,6 Significant effects involving marital status and gender, and significant interactions involving partner antisocial behavior, at any step of these preliminary analyses were included in subsequent hypothesis-testing analyses.

Hypothesis-testing analyses incorporated all the T1 predictors, partner antisocial behavior, and significant interactions identified in the preliminary analyses involving marital status, gender, and partner antisocial behavior into a single model predicting each couple outcome. To obtain the unique incremental variance associated with each block of variables, we entered variables in blocks in the following order: (a) marital status and gender, if significant in the preliminary models or if needed for the higher order interactions; (b) interaction of marital status with gender, if significant or needed; (c) all the T1 adolescent predictors (i.e., parent reports of parent-adolescent conflict, observed family aversive communication, parent report of adolescent’s depression, HRSD, and the adolescent antisocial behavior construct); (d) partner antisocial behavior; (e) all the two-way interactions (including the interactions of partner antisocial behavior with each independent variable and interactions of the predictors and partner antisocial behavior with gender or marital status), if significant or needed to interpret a three-way interaction; and (f) any significant three-way interactions.

In spite of the preliminary analyses, our hypothesis-testing models contained a relatively large number of interactions. For reasons of parsimony, we trimmed these models using backward elimination of nonsignificant interactions (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). We started with the highest order interaction, then eliminated the nonsignificant interaction (p> .05) with the smallest effect size from the model and reestimated the model. This process continued until all the nonsignificant three- and two-way interactions had been removed from the model, with the exception of the two-way interactions that were necessary to interpret significant three-way interactions. Because all the T1 predictors were theoretically related to couple functioning and were the focus of our hypotheses, all five T1 predictors were included in all the models, as was partner antisocial behavior. We present the results of the final trimmed models in Table 3.

Table 3.

Final Models Predicting Young Adult Relationship Functioning From Adolescent Predictors and Partner Antisocial Behavior

| Couple satisfaction | Couple aversive communication | Couple facilitative communication | Couple physical aggression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | β | t(239) | β | t(122) | β | t(127) | β | Improvement χ2(1, N = 252) | OR |

| Step 1 | |||||||||

| Marital status | 2.63 | 1.17 | −0.01a | −1.42 | −1.06 | 7.10** | 2.89b | ||

| Gender | −2.37 | −0.89 | −0.01 | −1.43 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.02 | ||

| Step 2 | |||||||||

| Marital Status × Gender | −1.04 | −0.29 | 0.11 | 1.79 | 0.73 | 1.09 | 2.07 | ||

| Step 3 | |||||||||

| Parent-adolescent conflict | 0.65 | 0.46 | 0.01 | 0.22 | −0.20 | −1.36 | −0.30 | 1.62 | 1.35b |

| Family aversive communication | −10.69 | −3.86*** | 0.23 | 2.20* | −0.19 | −0.64 | 2.19 | 16.65*** | 8.92 |

| Parent-rated depression | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.01 |

| HRSD | −0.13 | −0.48 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | −0.40 | −0.06 | 1.47 | 1.07b |

| Adolescent antisocial behavior | −0.90 | −1.38 | 0.00 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −1.80 | 0.25 | 4.69* | 1.28 |

| Step 4 | |||||||||

| Partner antisocial behavior | −6.56 | −4.72*** | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.15 | 0.93 | 0.64 | 2.79 | 1.90 |

| Step 5 | |||||||||

| Partner Antisocial Behavior × Adolescent Antisocial Behavior | 3.04 | 3.45*** | 0.26 | 2.91** | |||||

| Partner Antisocial Behavior × Parent-Rated Depression | −0.17 | 5.80* | 1.18b | ||||||

| Gender × Family Aversive Communication | 7.66 | 1.06 | −0.14 | −1.01 | |||||

| Marital Status × Family Aversive Communication | 11.69 | 1.94 | −0.26 | −1.93 | |||||

| Gender × Partner Antisocial Behavior | 0.46 | 0.26 | 1.59 | ||||||

| Marital Status × Partner Antisocial Behavior | 0.71 | 1.31 | 2.03 | ||||||

| Step 6 | |||||||||

| Gender × Marital Status × Family Aversive Communication | −29.71 | −2.34* | 0.82 | 3.07* | |||||

| Gender × Marital Status × Partner Antisocial Behavior | 2.43 | 4.72* | 11.32 | ||||||

Note. Regression coefficients are based on centered independent variables with gender coded as 0 (female) or 1 (male) and marital status coded as 0 (married) or 1 (dating). If no value was entered for a given variable, that variable was not included in the final model. OR = odds ratio; HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

The dependent variable is the inverse of aversive communication; direction of regression coefficients are reversed to show the direction of relation of predictors to aversive communication.

Reciprocal of the OR.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We examined significant interactions using procedures recommended by Holmbeck (1997) and by Aiken and West, (1991). Specifically, we interpreted significant interactions involving partner antisocial behavior by plotting simple regression lines for high (1 SD above the mean), low (1 SD below the mean), and moderate (at the mean) partner antisocial behavior, then testing the significance of the simple slope of each regression line (Aiken & West, 1991). We interpreted significant interactions with gender and marital status by testing the significance of the simple slope of each regression line associated with each gender in combination with each marital status. These tests of simple slopes controlled for all the previous steps in the respective regression.

Couple Satisfaction

Preliminary analyses examining individual predictor variables one by one indicated that gender and marital status significantly interacted with both family aversive communication and parent report of adolescent depression. Therefore, we included these interactions in hypothesis-testing regression analyses of couple satisfaction using hierarchical regression with backward elimination of nonsignificant interactions as described above. Regression coefficients and associated t values noted in Table 3 are based on the final trimmed model. Gender, marital status, and their interaction failed to account for significant variance when entered in Steps 1 and 2. At Step 3, the T1 predictors explained 7% of the variance in couple satisfaction, ΔF(5, 244) = 3.60, p < .01; only family aversive communication contributed significant unique variance at this step (sr = −.20). At Step 4, partner antisocial behavior significantly contributed to the prediction of couple satisfaction, accounting for an additional 7% of the variance, ΔF(1, 243) = 21.21, p < .001, sr = −.27. At Step 5, the two-way interactions explained an additional 4% of the variance in couple satisfaction, ΔF(3, 240) = 4.37, p < .01. At this step, the only two-way interaction that contributed significant unique variance was the interaction of partner antisocial behavior with adolescent antisocial behavior (sr = .2l). Finally, at the last step of the regression, the three-way interaction between gender, marital status, and family aversive communication, added significantly to the prediction equation (ΔR2 = .018), ΔF(1,239) = 5.45, p < .05, sr = −.13. The final model explained 21% of the variance in couple satisfaction, F(13, 239) = 4.88, p < .001.

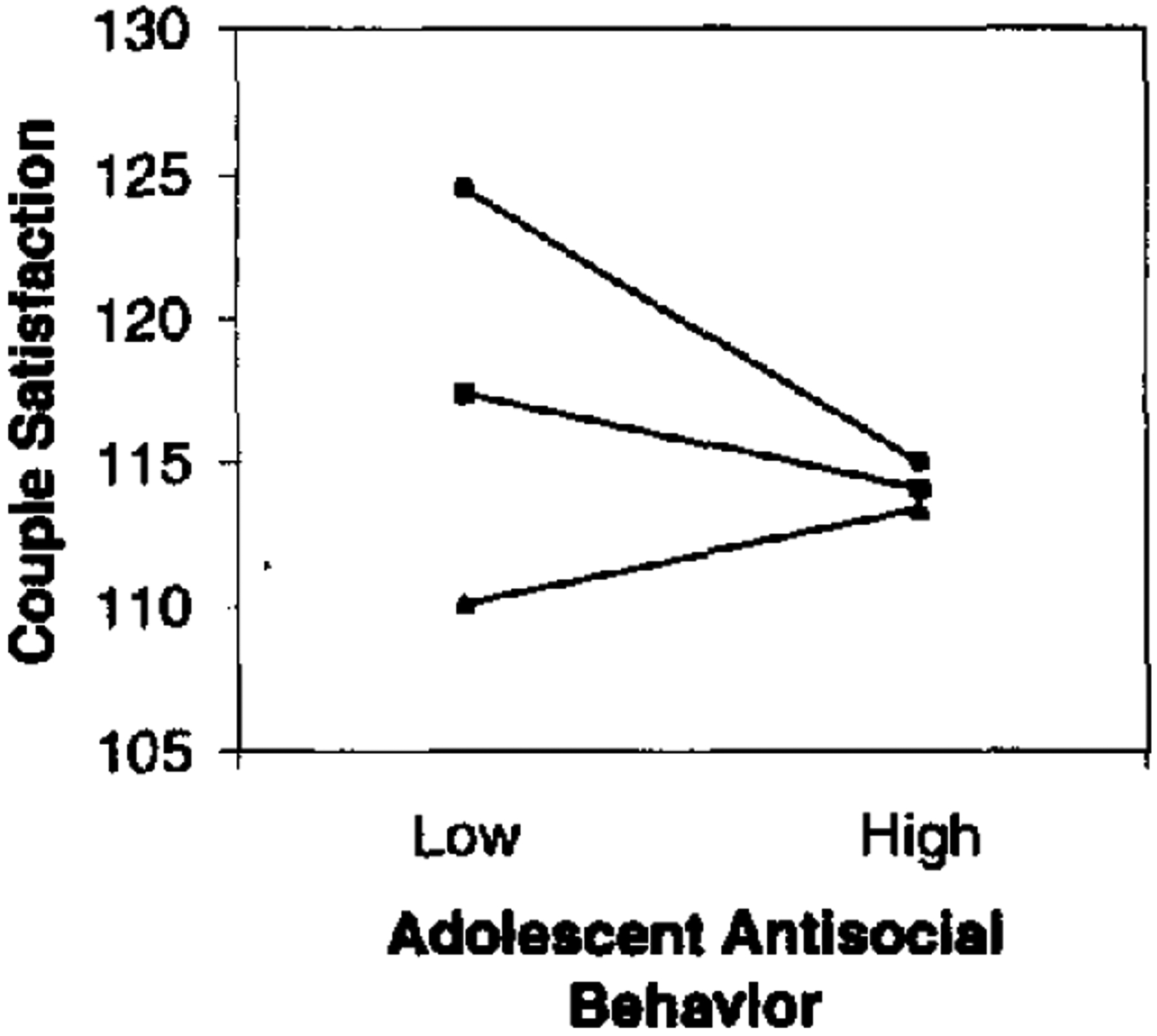

Figure 2 shows a plot of the simple slopes for the regression of couple satisfaction on adolescent antisocial behavior for values corresponding to high, low, and medium partner antisocial behavior. Analysis of simple slopes showed that the simple slope of the regression of couple satisfaction on adolescent antisocial behavior differed significantly from zero only for those whose partners reported low levels of antisocial behavior (B = −3.11), t(242) = −3.27, p < .001, but not for those whose partners reported medium (B = −1.03) or high (B = 0.99) levels of antisocial behavior. Figure 2 depicts the significant inverse relation between couple satisfaction and adolescent antisocial behavior for those with low partner antisocial behavior. Thus, adolescent antisocial behavior inversely predicted couple satisfaction only for those with prosocial partners.

Figure 2.

The relation between adolescent antisocial behavior and couple satisfaction as a function of partner antisocial behavior. The filled triangle represents high partner antisocial behavior, the filled square represents medium partner antisocial behavior, and the filled circle represents low partner antisocial behavior.

We examined the interaction of family aversive communication with gender and marital status by calculating the simple slope for the regression of couple satisfaction on family aversive communication for each combination of gender and marital status. Simple slopes differed significantly from zero for married women (B = −10.69), t(239) = −3.83, p < .001, and for dating men (B = −21.05), t(239) = −2.38, p < .05. Slopes were not significant for married men (B = −3.03) or for dating women (B = 1.01).

Couple Aversive Communication

Because examination of residuals indicated violation of the assumption of heteroscedasticity, and because couple aversive communication was highly skewed, we used an inverse transformation of the couple aversive communication variable. However, for ease of presentation, the direction of all the regression coefficients and associated t values are reversed, so that high scores on couple aversive communication still reflect high levels of dysfunction. Preliminary analyses showed significant three-way interactions between gender; marital status; and parent–adolescent conflict, family aversive communication, and depression. Therefore, we included these effects in the hierarchical regression used to test our hypotheses. However, only the interaction of gender, marital status, and family aversive communication remained significant in the hypothesis-testing analysis. None of the steps in the regression accounted for significant variance until Step 6. Despite this, at Step 3, the unique contribution of family aversive communication was significant (sr = .18). At Step 6, the three-way interaction between gender, marital status, and family aversive communication added significant incremental variance (ΔR2 = .07), ΔF(1, 122) = 9.41, p < .01, to the prediction of couple aversive communication in young adulthood. The final trimmed model shown in Table 3 explained 16% of the variance in couple aversive communication, F(12, 122) = 1.99, p < .05.

Examination of the three-way interaction indicated results similar to those obtained in the prediction of couple satisfaction. Specifically, the simple slope for the regression of dyadic aversive communication on family aversive communication differed significantly from zero for married women (B = 0.23), t(122) = 2.20, p < .05, and for dating men (B = 0.64), t(122) = 3.18, p < .01, but was not significant for dating women (B = 0.03) and for married men (B = 0.00)

Couple Facilitative Communication

In the preliminary analyses, the interactions of the HRSD and family aversive communication with both gender and marital status were significant. However, these three-way interactions and associated two-way interactions were not significant in the hypothesis-testing analysis, when all the T1 predictors were included. The main effects of gender and marital status were also not significant in the hypothesis-testing analysis. As the final trimmed model shows in Table 3, the block of T1 variables and partner antisocial behavior did not significantly explain dyadic facilitative communication. However, the interaction of partner antisocial behavior with adolescent antisocial behavior contributed significantly to the prediction of dyadic facilitative communication (ΔR2 = .06), ΔF(1, 127) = 8.47, p < .01. The final model explained 12% of the variance in couple facilitative communication, F(7, 127) = 2.39, p < .05.

Figure 3 shows the regression of couple facilitative communication on adolescent antisocial behavior at low, medium, and high levels of partner antisocial behavior. The simple slope differed significantly from zero only for those with partners with low antisocial behavior (B = −0.27), t(127) = −2.68, p < .01, but not for those with partners medium (B = −0.12) or high (B = 0.00) in antisocial behavior. Thus, similar to the results predicting couple satisfaction, adolescent antisocial behavior inversely predicted couple facilitative communication only for young adults who dated or for married partners with infrequent antisocial behavior.

Figure 3.

The relation between adolescent antisocial behavior and dyadic facilitative communication as a function of partner antisocial behavior. The filled triangle represents high partner antisocial behavior, the filled square represents medium partner antisocial behavior, and the filled circle represents low partner antisocial behavior.

Couple Physical Aggression

Logistic regression examined the relation between the predictors and the occurrence and nonoccurrence of physical aggression in the relationship as reported by either member of the couple. Preliminary analyses showed two significant three-way interactions involving gender and marital status, one with partner antisocial behavior and the other with parent report of adolescent depression, so these effects were included in the hypothesis-testing regression. As shown in Table 3, only the three-way interaction involving partner antisocial behavior, gender, and marital status was retained in the trimmed model. At Steps 1 and 2, the blocks of variables that included marital status and gender and their interaction did not significantly predict couple physical aggression. Although the overall regression was not significant at these steps, marital status contributed significant unique variance at Step 1. At Step 3, the block of T1 adolescent measures contributed significantly to the prediction of physical aggression, Δχ2(5, N = 252) = 26.65, p < .001. Both family aversive communication and adolescent antisocial behavior contributed significant unique variance at this step. At Step 4, partner antisocial behavior added significant variance to the prediction of dyadic physical aggression, Δχ2(1, N = 252) = 7.11, p < .01. The block of two-way interactions contributed significantly to the prediction of dyadic physical aggression at Step 5, Δχ2(3, N = 252) = 9.86, p < .05. The interactions between partner antisocial behavior and parent-rated adolescent depression and between gender and partner antisocial behavior were significant at this step. The three-way interaction between marital status, gender, and partner antisocial behavior contributed significantly at Step 6, Δχ2(1, N = 252) = 4.72, p < .05. The final model was significant, χ2(13, N = 252) = 52.82, p < .001, yielding a Nagelkerke estimate of R2 of .25 (see Table 3).

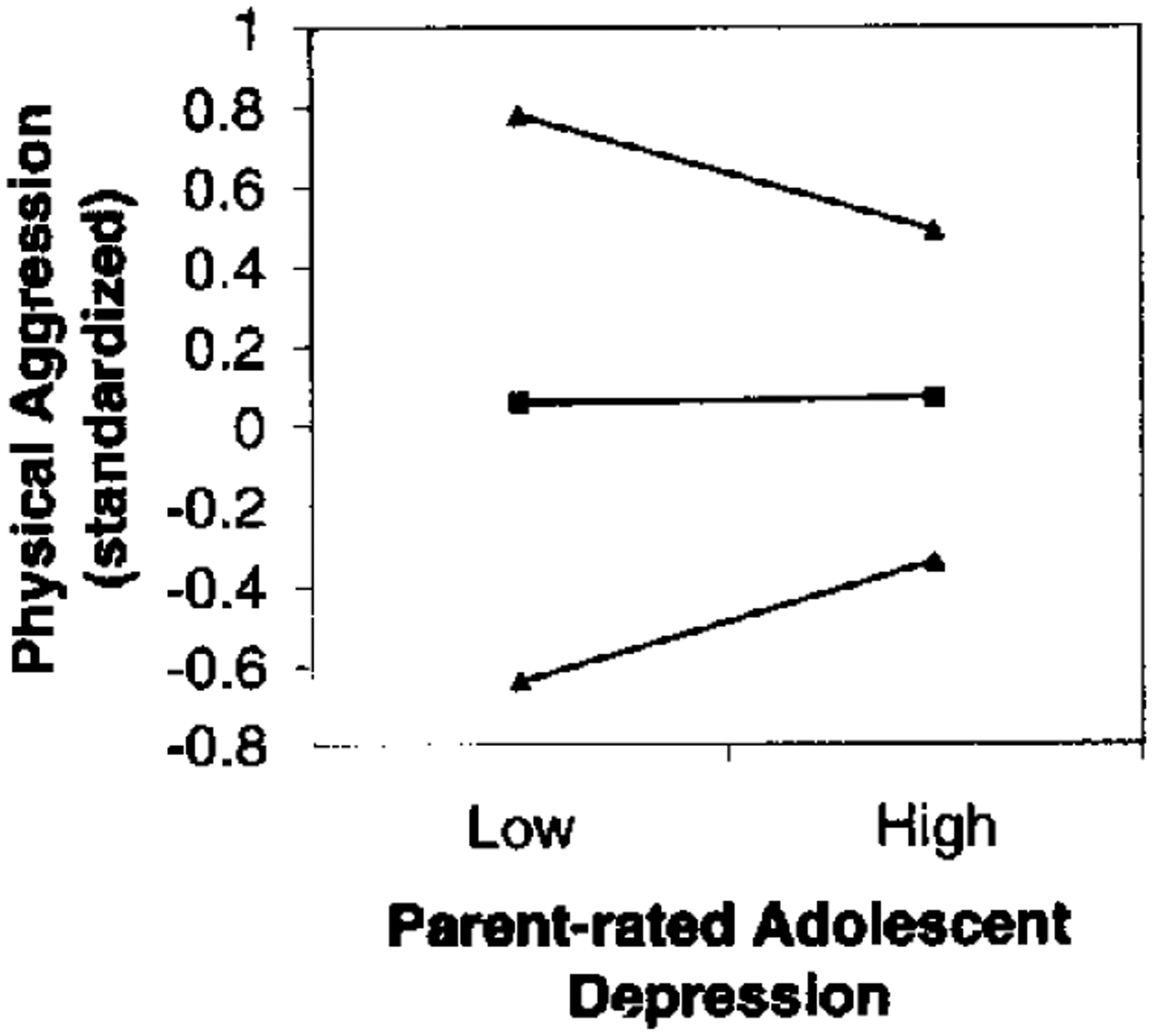

As shown in Figure 4, the relation between parent-rated adolescent depression and couple physical aggression was negative for those with partners who reported high levels of antisocial behavior (B = −0.09), positive for those with partners who reported low levels of antisocial behavior (B = 0.10), and unrelated for those with partners who reported medium levels of antisocial behavior (B = 0.00). Although the difference between simple slopes associated with high and low levels of partner antisocial behavior was significant, as shown by the significance of the interaction effect (p < .05; Aiken & West, 1991), none of the simple slopes were significantly different from zero.

Figure 4.

The relation between parent-related adolescent depression and physical aggression (standardized) as a function of partner antisocial behavior. The filled triangle represents high partner antisocial behavior, the filled square represents medium partner antisocial behavior, and the filled circle represents low partner antisocial behavior.

Because the results of this analysis did not clearly indicate the source of the significant interaction, we examined the relation between partner antisocial behavior and couple physical aggression at high, medium, or low levels of adolescent depression. This analysis showed that the simple slope was significantly different from zero for those with low parent-rated adolescent depression (B = 1.10, odds ratio [OR] = 3.00), improvement χ2(1, N = 252) = 11.92, p < .001, but not for those with high (B = 0.03) or medium (B = −0.61) parent-rated adolescent depression. Thus, the significant interaction emerged from the finding that partner antisocial behavior was related to couple physical aggression only among young adults whose parents reported them to be low in depression during the adolescent assessment.

Examination of the three-way interaction of partner antisocial behavior with gender and marital status showed a significant relation between partner antisocial behavior and physical aggression for dating women (B = 1.35, OR = 3.86), improvement χ2(1, N = 252) = 9.50, p < .01, but not for married women (B = 0.64), dating men (B = −0.61), or married men (B = 1.11). Thus, among dating women, the greater the level of antisocial behavior reported by their male partner, the greater the woman’s risk for experiencing physical aggression in the relationship.

In summary, family aversive communication and adolescent antisocial behavior were independent predictors of couple physical aggression for all the participants. For dating women and for those with lower levels of parent-rated depression in adolescence, the antisocial behavior of their partner also predicted couple physical aggression.

Partner Antisocial Behavior as a Mediating Variable

One purpose of this study was to examine whether partner antisocial behavior might mediate the relation between T1 predictors and the criterion variables. According to Baron and Kenny (1986), a variable must meet three criteria to function as a mediator: First, the relation between the predictor and the hypothesized mediating variable must be significant. To investigate whether partner antisocial behavior met this criterion, we examined the extent to which T1 variables and constructs predicted partner antisocial behavior. To eliminate problems with violation of the homoscedasticity assumption, we transformed partner antisocial behavior using a logarithmic transformation. In this regression, we entered gender and marital status at Step 1, followed by the five T1 predictors at Step 2. Step 1 accounted for 8% of the variance in predicting partner antisocial behavior, ΔF(2, 251) = 10.16, p < .001. Marital status predicted log-transformed partner antisocial behavior (B = 0.005, p < .001, sr = .28), as did gender (B = −0.003, p < .05, sr = −.12). Dating couples had partners who reported higher levels of antisocial behavior than did married couples, and male partners reported more antisocial behavior than did female partners. After controlling for marital status and gender, we found that the block of T1 adolescent variables did not add significant incremental variance. However, adolescent antisocial behavior uniquely predicted partner antisocial behavior (B = 0.001, p < .05, sr = .12). This analysis failed to support the hypothesis that partner antisocial behavior would mediate relationships between adolescent depression, family conflict, or family aversive communication and couple outcomes but indicated that partner antisocial behavior might mediate the relationship between adolescent antisocial behavior and couple outcomes.

A second criterion for mediation is that the relation between the hypothesized mediating variable and the criterion must be significant. Examination of the univariate correlations in Table 3 showed significant correlations between partner antisocial behavior and couple satisfaction and the presence or absence of couple physical aggression (ps < .05), satisfying this second criterion of mediation for these two variables.

Third, once the hypothesized mediating variable is controlled for, the previous significant relation between the predictor and the criterion should become nonsignificant. We reexamined our earlier regression results to see whether findings involving partner antisocial behavior met this criterion. Before entering partner antisocial behavior in the regression, we found that adolescent antisocial behavior independently predicted only couple physical aggression (B = 0.25) and did not predict other measures of couple functioning. The effect of adolescent antisocial behavior changed little (B = 0.23) and remained significant after adding partner antisocial behavior to the model predicting couple physical aggression. Thus, the third criterion of mediation was not met. Consequently, although partner antisocial behavior did not mediate the relation between adolescent antisocial behavior and couple functioning, both adolescent antisocial behavior and partner antisocial behavior were independently related to physical aggression.

Discussion

This prospective study examined a model predicting couple functioning in young adulthood from the adolescent’s antisocial behavior, depression, and conflict in the family of origin. We explored four dimensions of couple functioning: dyadic satisfaction, couple facilitative and aversive communication, and couple physical aggression. Gender and marital status were also included as possible moderators of these relationships, as was the self-reported level of antisocial behavior of the participant’s romantic partner. The present results provide partial support for the proposed model. Family aversive communication during adolescence predicted three of the four measures of couple functioning, namely dyadic physical aggression (for the entire sample) and satisfaction with their relationship and aversive communication (for married women and dating men). Adolescent antisocial behavior predicted dyadic physical aggression (for the entire sample) and inversely predicted couple satisfaction and facilitative communication (for those with partners with low antisocial behavior). Partner antisocial behavior did not mediate the relation between adolescent predictors and young adult couple functioning but predicted physical aggression for dating women and for those with low levels of parent-rated depressive symptoms.

The relation between family aversive communication during adolescence and young adult functioning of the marital or dating dyad suggests the importance of family conflict during adolescence to the dyadic functioning of young adults and their partners within dating and marital relationships and provides indirect support for the strong association reported by Capaldi and Clark (1998) between unskilled parenting and sons’ later aggression toward a partner. These findings are also consistent with those of other studies showing that family conflict is related positively to deficient parenting practices (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997) and inversely to the acquisition of social skills necessary for engaging in productive social relationships (Patterson et al., 1992; Pettit, Clawson, Dodge, & Bates, 1996).

The aversive communication variable included parent-to-parent aversive exchanges as well as parent-teen communication. Thus, this finding also indirectly supports research noting a relation between interparent conflict and the child’s subsequent functioning within a relationship (Widom, 1989). The present results point to the importance of the family environment in adolescence, particularly communication patterns, in the development of adult social relationships and highlight the possible long-term effects of family-of-origin discord on the functioning of the dating or married couple.

These data also point to the importance of nonphysical aggression as a possible marker for physical aggression. The aversive communication observed between parents and adolescents was verbal and nonverbal and included any forms of sarcasm, insults, and criticisms, as well as irritability and obscene or condescending gestures. That this form of interaction, assessed observationally during a 20-min problem-solving discussion, predicted physical aggression in couples 6 years later suggests that we should not take verbal aggression lightly.

Another important finding of the present study is the significant prospective association between adolescent antisocial behavior and the young couple’s physical aggression for young women as well as men. These findings replicate a previous prospective study with men (Capaldi & Clark, 1998) and provide support for the continuity of aggression from adolescence to young adulthood. These findings emphasize a need for research to identify protective factors that will deter adolescents with patterns of conduct disturbance from violent relationships as they reach adulthood.

The significant interaction between the antisocial behavior of the partner and the psychopathology of the adolescent in the prediction of several aspects of couple functioning suggests that the level of psychopathology of both members of the dyad contributes to the functioning of the couple. However, contrary to our predictions, having a partner with low antisocial behavior did not protect the at-risk adolescent from a dysfunctional relationship in young adulthood. Whereas Quinton and colleagues (Pickles & Rutter, 1991; Quinton et al., 1993) found that having a supportive partner with low levels of antisocial behavior promoted a switch from maladaptive functioning to more adaptive functioning, we found a negative relation between adolescent antisocial behavior and subsequent couple satisfaction and facilitative communication for those with a prosocial partner. If one assumes continuity of antisocial behavior from adolescence to young adulthood, the pattern of these relationships suggests that the greater the mismatch between young adults and their partners in terms of antisocial behavior, the less their facilitative communication and satisfaction within the relationship. Caspi and Herbener (1990) hypothesized that a match between the antisocial behavior of adolescents and that of their partners increases the likelihood of maintenance of antisocial behavior through reinforcement. Perhaps individuals who are more prosocial are less tolerant of antisocial tendencies in their partners and withdraw from the relationship behaviorally and psychologically when paired with antisocial partners. Regardless of the process, this mismatch suggests an unhappy relationship and perhaps one that will have a short life span.

The finding that family aversive communication positively predicted couple aversive communication and inversely predicted couple satisfaction only for dating men and married women is perplexing. One possible explanation comes from the finding that dating men and married women view themselves as more powerful than do dating women and married men (Murstein & Adler, 1995). Perhaps negative communication patterns learned in the family of origin are expressed only in secure relationships or are suppressed when the individual feels less powerful and therefore perhaps less safe in expressing negative emotions. These negative communication patterns may include negative control tactics shown to be related to couple satisfaction and aggression (Ehrensaft, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Heyman, O’Leary, & Lawrence, 1999). Clearly, future investigations need to replicate these findings and to explore viable explanations for these relationships.

Our findings did not provide support for the mediational role of partner antisocial behavior in explaining the link between adolescent predictors and the functioning of the dyad. However, male partners’ antisocial behavior positively predicted couple physical aggression for dating women and was important in predicting several outcomes, most often in interaction with other variables. Given their concurrent assessment, we cannot say with certainty that partner antisocial behavior preceded the relationship outcomes. However, given the stability of antisocial behavior (Loeber, 1982; Olweus, 1979), it is more likely that the partner’s antisocial behavior preceded the couple’s functioning than vice versa. This implies that partner choice is a key young adult decision. Clearly, the determinants that lead some to date or marry individuals with aggressive tendencies would be important to determine.

Several findings related to the marital status and gender of the couple are noteworthy. First, dating couples reported higher levels of partner antisocial behavior than did married couples. This could easily occur if many distressed dating relationships dissolve prior to marriage or if young adults are willing to date a partner with some undesirable behaviors but not willing to marry him or her. A second set of findings relates to assertions of feminist theory that female aggression is usually in retaliation or self-defense (Saunders, 1986). If this were the case, one would expect the partner’s antisocial behavior to predict couple physical aggression for women (whose partners are men and therefore should be the instigators of physical aggression) but not for men (whose female partners’ aggression should be limited to self-protection in the relationship but not to general levels of aggression in other settings) and adolescent antisocial behavior to predict couple physical aggression for men but not women. Providing minor support for this theory, partners’ current antisocial behavior predicted couple physical aggression for dating women with male partners but not for either the male subsample or for married women. However, in contrast to the predictions of this theory, gender did not interact with adolescent antisocial behavior in the prediction of couple physical aggression or other indices of couple functioning. Higher levels of antisocial behavior in both male and female adolescents increased their risk for involvement in physically aggressive relationships in their early 20s. Unfortunately, our measure of physical aggression did not enable us to disentangle the process by which these relationships form and evolve.

In general, findings presented here corroborate and extend previous cross-sectional and monoinformant studies. However, despite its strengths, the study has limitations. First, the sample was relatively racially and demographically homogeneous. In addition, because initial sampling occurred in high schools, the highest risk adolescents (i.e., dropouts) may not have been sampled. Second, the antisocial partner construct used only self-report, and some additional measures would have been desirable. Two of the criterion measures, couple satisfaction and couple physical aggression, consisted of the average report of the partner and the target young adult, which suggests that shared method variance may have played a role in the relation between partner antisocial behavior and these variables.

Third, the predictors, despite being significantly related to couple outcomes, often accounted for relatively small amounts of variance. Methodological and substantive considerations may have contributed to this. One of the methodological issues involved in data analyses concerned missing data. It was not uncommon for a parent to decline to participate or for a questionnaire to be incomplete; however, because we averaged across parents, we were able to use parent-report data from all the participants with at least 1 parent. Thus, scores were sometimes composed of different components for different participants, which may have added error to these scores, reducing the magnitude of correlations. A second explanation for the low magnitude of correlations lies in the fact that we sampled adolescent behavior and couple behavior only at single time points. Conflict and depression in particular can be somewhat fluid in adolescence, and it may be that stable patterns of behavior would have stronger predictive relations to young adult outcomes.

A final reason for the relatively low-magnitude correlations is conceptual. We chose to take a broad-brush approach to looking at family and couple relationships. It may be that particular aspects of family conflict and communication (e.g., the relationship between the adolescent and the opposite-gender parent or particular patterns of communication rather than overall aversiveness), not the more global variables included here, undergird the skills that adolescents take into relationships in young adulthood. These more molecular relationships are obscured by the construct approach used here and warrant further elaboration in future studies.

The present study makes an important contribution by using multimethod data to predict young adults’ relationship satisfaction, physical aggression, and communication from prospective predictors measured in adolescence. Our study further extends others’ findings by examining the associations in a relatively large community sample of men and women. The findings of this study support prevention efforts to reduce the likelihood of a dysfunctional and physically aggressive couple relationships by focusing both on building family communication skills among family members during the adolescent years and reducing antisocial behavior. Such prevention efforts would be expected to promote the development of positive, skilled interactions with intimate partners in young adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5 RO1 MH43311-10 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Support was also provided by Grant MH 50259 from the NIMH Prevention, Early Intervention, and Epidemiology Branch.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Anthony Alpert, Betsy Davis, Fuzhong Li, and Elizabeth Mondulick for helping with data analysis and article preparation.

Footnotes

A preliminary version of the results described in this article was previously presented at the 7th Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Adolescence, San Diego, California, February 1998.

Three participants had a romantic partner of the same gender. Data from these individuals are not presented in this study.

We excluded couples who were living together from analyses because previous literature indicates that these couples often differ from married and dating couples (Stets & Straus, 1989) and because of the relatively small number of these couples in the present sample. Analyses of variance comparing dating, married, and cohabiting couples supported this decision in that cohabiting couples consistently resembled neither married nor dating couples. Married, dating, and cohabiting couples differed significantly in their mean Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) scores, F(2, 359) = 7.19, p < .001, and observed facilitative behavior, F(2, 170) = 13.67, p < .001. Tukey’s post hoc tests showed that the cohabiting couples reported significantly lower DAS scores (M = 94.14) than did either the married (M = 101.93) or dating couples (M = 102.53). The dating couples displayed significantly higher rates of facilitative behavior in the problem-solving discussions (M = 3,47) than did either the married (M = 2.81) or cohabiting couples (M = 2.39). A chi-square examining presence or absence of physical aggression also showed significant differences among the groups, χ2(2, N = 359) = 17.34, p < .001; 65% of the cohabiting couples reported some physical aggression compared with 47% of the married couples and 33% of the dating couples.

To derive the measure of aversive behavior used in this study, we slightly modified the LIFE aggressive behavior construct from the way it was used in previous studies. Specifically, we eliminated oppositional statements made in a neutral tone of voice from the composition of the category on the grounds that many view neutral opposition as appropriate problem-solving behavior rather than as aversive behavior.

Although we scored the CTS dichotomously for this study, we also calculated couple physical aggression scores, which were scored continuously. This variable correlated higher than the dichotomous CTS score with partner antisocial behavior (r = .36, p < .001), suggesting that partner antisocial behavior may be particularly related to the severity of physical aggression reported by the couple.

This procedure capitalized on power, increasing the probability to detect effects associated with gender and marital status. Although, admittedly, the large number of analyses capitalized on chance, we maintained our alpha level at p < .05 because, in these preliminary analyses, we were concerned with prematurely eliminating significant interactions with gender and marital status.

We did not evaluate the significance of the four-way interactions because of the general difficulties of interpreting four-way interactions.

Contributor Information

Judy A. Andrews, Oregon Research Institute

Sharon L. Foster, California School of Professional Psychology

Deborah Capaldi, Oregon Social Learning Center.

Hyman Hops, Oregon Research Institute.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1997). Manual for the Young Adult Behavior Checklist and Young Adult Self-Report. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, & Roberts RE (1993). Development and psychometric properties of abbreviated scales for the measurement of psychosocial variables related to depression in adolescents. Psychological Reports, 73, 1019–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias I, Samios M, & O’Leary KD (1987). Prevalence and correlations of physical aggression during dating courtship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 2, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 512, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap J (1989). The sexual victimization of unmarried women in nonrelative acquaintances. In Pirog-Good MA & Stets JE (Eds.), Violence in dating relationships: Emerging social issues (pp. 205–218). New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Hops H, Sherman L, Friedman LS, Arthur J, & Osteen V (1985). Problem-solving interactions of depressed women and their husbands. Behavior Therapy, 16, 431–451. [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, Frieze IH, Smith C, & Ryan K (1992). Predictors of dating violence: A multivariate analysis. Violence and Victims, 7, 297–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM (1992). Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive mood in early adolescent boys: II. Two year follow-up at 8th grade. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 125–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, & Clark S (1998). Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for young at-risk males. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1175–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, & Crosby L (1997). Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development, 6, 184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, O’Leary KD, Lawrence EE, & Schlee KA (1995). Characteristics of women physically abused by their spouses who seek treatment regarding marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 616–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, & Vivian D (1995). Context for specific episodes of marital violence: Gender and severity of violence differences. Journal of Family Violence, 10, 265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, & Herbener ES (1990). Continuity and change: Assortative marriage and the consistency of personality in adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, & Cohen P (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, & McPherson AE (1993). Relation of family subsystems to adolescent depression: Implementing a new family assessment strategy. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Rushe R, & Cox G (1993). Negative reciprocity and communication in couples with a violent husband. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, & Dodge KA (1997). Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited. Psychological Inquiry, 8, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A (1987). The efficacy of a spouse abuse model in accounting for courtship violence. Journal of Family Issues, 8, 291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Heyman RE, O’Leary KD, & Lawrence E (1999). Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr., Caspi A, & Downey G (1986). Problem behavior and family relationships: Life course and intergenerational themes. In Sorensen AB, Weinert FE, & Sherrod LR (Eds.), Human development and the life course: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 293–340). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, & Ageton SS (1985). Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, & Morse BJ (1986). Self reported violent offending: A descriptive analysis of juvenile violent offenders and their offending careers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 4, 472–514. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Cohen J, Nee J, Fleiss J, & Sarantakos S (1981). Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—Extracted from regular and change versions of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35, 837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo L, & Margolin G (1995). A multivariate investigation of dating aggression. Journal of Family Violence, 10, 351–377. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, & Tolan PH (1998, February). Relationship and predatory violence among inner-city minority youths. Paper presented at the 7th Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Adolescence, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Gwartney-Gibbs PA, Stockard J, & Bohmer S (1987). Learning courtship aggression: The influence of parents, peers and personal experiences. Family Relations, 36, 276–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology and Neurosurgery, 23, 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]