Abstract

Plant transformation and regeneration remain highly species- and genotype-dependent. Conventional hormone-based plant regeneration via somatic embryogenesis or organogenesis is tedious, time-consuming, and requires specialized skills and experience. Over the last 40 years, significant advances have been made to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying embryogenesis and organogenesis. These pioneering studies have led to a better understanding of the key steps and factors involved in plant regeneration, resulting in the identification of crucial growth and developmental regulatory genes that can dramatically improve regeneration efficiency, shorten transformation time, and make transformation of recalcitrant genotypes possible. Co-opting these regulatory genes offers great potential to develop innovative genotype-independent genetic transformation methods for various plant species, including specialty crops. Further developing these approaches has the potential to result in plant transformation without the use of hormones, antibiotics, selectable marker genes, or tissue culture. As an enabling technology, the use of these regulatory genes has great potential to enable the application of advanced breeding technologies such as genetic engineering and gene editing for crop improvement in transformation-recalcitrant crops and cultivars. This review will discuss the recent advances in the use of regulatory genes in plant transformation and regeneration, and their potential to facilitate genotype-independent plant transformation and regeneration.

Introduction

Plant transformation and regeneration are highly species- and genotype-dependent and are often the principal bottlenecks in applying genetic engineering and gene editing for crop trait improvement [1–4]. Plant transformation starts with delivering genes of interest into single regeneration-competent or embryogenic stem cells, typically achieved through Agrobacterium-mediated or biolistics-based methods. In vitro plant regeneration is a process of generating a whole plant from a single cell derived from various explants such as leaf, cotyledon, hypocotyl, root, microspore, and immature embryo, and usually involves the formation of callus from explants cultured on a callus-inducing medium (CIM). Callus is a highly heterogeneous group of cells with organized structures similar to lateral root primordia [5], most of which are regeneration-incompetent cells with a limited number of cells capable of proliferating. The foundation of plant regeneration lies in the totipotency of plant cells, which is the ability of a somatic or meristematic cell to regenerate into an entire plant [6]. The successful regeneration of a singular transformed cell into a fully functioning plant dictates the success of plant transformation.

Regeneration-competent cells can originate from the proliferation of pre-existing undifferentiated meristematic cells within explants that will go through direct organogenesis to develop into plantlets. This process permits the co-cultivation of explants with Agrobacterium for the delivery of the genes of interest into the regeneration-competent cells, e.g. the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of cotyledonary nodal regions of soybean where axillary meristem is located. In many plant species, however, regeneration-competent cells originate from reprogrammed differentiated somatic cells via a dedifferentiation process to regain the capacity for proliferation competence or pluripotency, i.e. the ability of plant embryogenic or stem cells to develop into all shoot and root cell types [7]. Acquisition of pluripotency converts somatic cells to regeneration-competent cells for callus induction. Thus, Agrobacterium-mediated gene delivery can be performed at different stages from isolated explants such as leaf discs or immature embryos to the resulting callus.

Through somatic embryogenesis and de novo organogenesis, transformed regeneration-competent cells develop into somatic embryos and shoot/root apical meristems (SAMs/RAMs), respectively, which develop into plantlets [6–12] (Figure 1). Somatic embryogenesis starts with the formation of an embryo-like structure from embryogenic cells like those in calli that further develops into a whole plant. Organogenesis may result in the formation of shoots and roots directly from explants (i.e. direct organogenesis) or start with the formation of SAM development from callus, and then the SAM develops into shoots that subsequently generate roots (i.e. indirect organogenesis) [13].

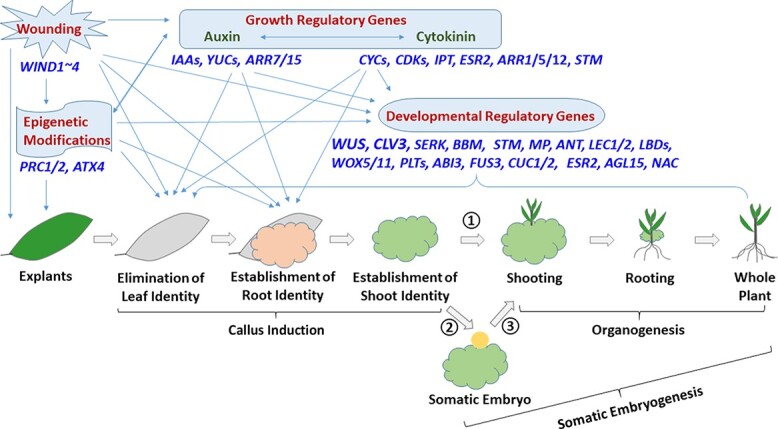

Figure 1.

Key steps and factors in exogenous hormone-induced plant regeneration. Aerial explants go through the sequential steps of elimination of leaf identity, establishment of root identity, establishment of shoot identity, followed by organogenesis (step ①) or somatic embryogenesis (steps ② and ③). Wounding, epigenetic modifications, growth regulatory genes, and developmental regulatory genes are the four classes of crucial regeneration-promoting factors. Boxed arrows, key steps. Dark red, regeneration-promoting factors. Blue, key genes for each factor. Green, plant growth hormones. Orange circle, somatic embryo.

Since various factors affect callus formation and plant regeneration, conventional plant transformation requires optimizing many external factors including explant types, plant growth regulators (mainly auxin and cytokinin that are natural or synthetic chemicals exogenously applied to modify plant growth), basal media composition, pH, light conditions, and transgenic plant selection strategies. However, recent advances in the understanding and identification of plant growth and developmental regulatory genes (also called morphogenic genes) have revealed that many of these genes are involved in the regulation of biosynthesis and signaling pathways of auxin and cytokinin and thus control the plant regeneration process [2–5,10,12,14] (Figure 1; Table 1). Plant growth regulatory genes are involved in the biosynthesis, perception and transduction of plant growth hormones that are endogenously biosynthesized within plants and regulate plant growth. Plant developmental regulatory genes are the transcriptional factors or signaling molecules that control cell fate and thus regulate plant development (e.g. organ formation) by regulating the expression of various genes. The use of growth and developmental regulatory genes could significantly improve regeneration/transformation efficiency, speed up the transformation process, and enhance the application of gene editing in various crops [15–18] (Table 1). This review will discuss: i) recent advances in the identification of the functions of growth and developmental regulatory genes and their use in plant transformation; ii) the potential of these advances to create novel approaches for genotype-independent plant transformation and regeneration; and iii) how these advances can be harnessed to provide a better understanding of plant transformation from the molecular and developmental biology perspectives.

Table 1.

Summary of plant growth and developmental regulatory genes studied in plant transgenic research

| Gene Cassette | Transformed Species | Explant | Hormone | Regeneration a | Regenerated Plant | Transform. Efficiency | Abnormal Phenotype | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue culture – based plant transformation | ||||||||

| 35S:AtWUS | Gossypium hirsutum | Hypocotyl | 2,4-D, kinetin | Embryogenesis | × | N.A. | √ | [23] |

| PG10–90:XVE-OLexA -min35S:AtWUS | Nicotiana tabacum | Leaf | BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | √ | [24,25] |

| Coffea canephora | Leaf | BAP, IAA | Embryogenesis | √ | N.A. | √ | [26,27] | |

| PG10–90:XVE OLexA -min35S:AtWOX5 or 2/8 or 2/9 | N. tabacum | Leaf | BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | N.A | √ | [24,28] |

| 35S:GAL4 -AtRKD4-GR | Phalaenopsis | Leaf | – | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ 3.6 times | × | [29] |

| 35S:AtBBM; 35S:BnBBM | N. tabacum | Leaf | IAA | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | √ | [30,31] |

| 35S:BnBBM; HaUbi:BnBBM | Brassica napus | Microspore | N.A. | Embryogenesis | × | N.A. | √ | [32] |

| 35S:TcBBM | Theobroma cacao | Cotyledonb | 2,4-D, TDZ, kinetin | Embryogenesis | × | N.A. | √ | [33,34] |

| 35S:TcBBM-GR | T. cacao | Cotyledonb | 2,4-D, TDZ, kinetin | Embryogenesis | × | N.A. | × | [35] |

| 35S:AtBBM-GR; 35S:BnBBM-GR | N. tabacum | Leaf | IAA | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | × | [30, 31] |

| 35S:BnBBM-GR | Capsicum annuum | Cotyledon | TDZ | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ | √ | [36] |

| AtHSP18.2:FLP -35S:BcBBM | Populus tomentosa | Leaf | NAA, zeatin | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [37] |

| ZmUbi:ZmBBM + NOS:ZmWUS2 | Zea mays; Oryza sativa; Sorghum bicolor; Saccharum officianrum | Immature embryo | 2,4-D, BAP | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [14] |

| ZmUbi:ZmBBM + NOS:ZmWUS2 | Z. mays; S. bicolor | Immature embryo | 2,4-D | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [16] |

| ZmPLTP:ZmBBM + ZmAxig1:ZmWUS2 | Z. mays | Immature embryo | 2,4-D, BAP | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [38] |

| ZmPLTP:ZmWUS2 | Z. mays | Immature embryo | 2,4-D, BAP | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [39] |

| ZmPLTP:ZmBBM+ ZmPLTP:ZmWUS2 | S. bicolor | Immature embryo | 2,4-D | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [40] |

| 35S:GVG-6xUAS -min35S:CcSERK1 | C. canephora | Leaf | NAA, BAP, kinetin | Embryogenesis | × | N.A. | × | [41] |

| 35S: PaHAP3A; PG10–90:XVE-OLexA -min35S:PaHAP3A | Picea abies | Embryonic cell lines | 2,4-D, BA, NAA, ABA, IBA | Embryogenesis | × | N.A. | × | [42] |

| 35S:TcLEC2-GR | T. cacao | Cotyledonb | 2,4-D, TDZ, kinetin | Embryogenesis | × | N.A. | × | [35] |

| PG10–90:XVE-OLexA -min35S:AtLEC2 | N. tabacum | Leaf | BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | √ | [24,25] |

| 35S:GmAGL15 | Glycine max | Cotyledon | 2,4-D | Embryogenesis | √ | ↑ 2 times | √ | [43] |

| 35S:GhAGL15 | G. hirsutum | Hypocotyl | 2,4-D, IAA, kinetin | Embryogenesis | × | × | × | [44] |

| 35S:BnSTM; 35S:BoSTM | B. napus | Hypocotyl | BAP, NAA | Embryogenesis | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | [45] |

| 35S:NtNTHs | N. tabacum | Leaf | BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | √ | [46] |

| 35S:ZmKn1 | N. tabacum | Leaf | – | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 3 times | √ | [47] |

| Citrus sinensis | Internode | BAP, NAA, 2,4-D | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 3 ~ 15 times | √ | [48] | |

| 35S:AtCUC1 or 2 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Seedling | IBA, IAA, 2,4-D, kinetin | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 10 times | √ | [49, 50] |

| PG10–90:XVE-OLexA -min35S:AtESR1 | A. thaliana | Root | 2,4-D, IAA, 2-iP, kinetin | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [51] |

| PG10–90:XVE-OLexA -min35S:AtESR2 | A. thaliana | Root | 2,4-D, IAA, 2-iP, kinetin | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 3 times | × | [52,53] |

| AtMP:AtMP∆ | A. thaliana | Root, leaf, petiole, cotyledon | 2,4-D, IBA, 2-iP | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | √ | [54] |

| 2 × 35S:AtGRF5; 2 × 35S:BvGRF5-L | Beta vulgaris | Cotyledon, hypocotyl | BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 6 times | × | [55] |

| 2 × 35S:AtGRF5; 2 × 35S:HaGRF5-L | Helianthus annuus | Cotyledon | BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [55] |

| PcUbi4–2:: GmGRF5-L | G. max | Primary node | IAA, kinetin, IBA, zeatin | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [55] |

| PcUbi4–2: BnGRF5-L | B. napus | Hypocotyl | 2,4-D, zeatin, kinetin | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [55] |

| BdEF1:AtGRF5; BdEF1:ZmGRF5- L1/2 | Z. mays | Immature embryo | 2,4-D, zeatin, IBA, BAP | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ | × | [55] |

| ZmUbi:GRF4-GIF1 * | Triticum aestivum | Immature embryo | 2,4-D, zeatin | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 7.8 times | × | [56] |

| O. sativa | Seed | 2,4-D, BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 2.1 times | × | ||

| C. lemon | Etiolated epicotyl | BAP, NAA, BA | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 4.7 times | × | ||

| 35S:ipt in Ac * | N. tabacum | Leaf | – | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | × | [57] |

| P. sieboldii × P. grandi-entata | Stem | IBA | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | × | ||

| 35S:GVG - 6 × UAS -min35S:pt * | N. tabacum; | Leaf | BAP, NAA | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 1.2 times | × | [58] |

| Lactuca sativa | Cotyledon | NAA | Organogenesis | √ | ↑ 3.8 times | × | ||

| Non-tissue culture – based plant transformation | ||||||||

|

Nos:ZmWUS2 -ZmUbi:IPT

*; Nos:ZmWUS2 -ZmUbi:AtSTM* |

A. thaliana; N. tabacum; Solanum lycopersicum | Agro transient | – | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | × | [59] |

| S. tuberosum; N. tabacum; Vitis vinifera | Mature plant | – | Organogenesis | √ | N.A. | × | ||

Embryogenesis, somatic embryogenesis.

Staminodes were used as the explants to induce somatic embryos, and cotyledons from the somatic embryos were used for plant transformation.

Antibiotic selectable marker-free. √, yes. ×, no.

Key steps and factors in CIM-induced plant regeneration

Exogenous hormone-induced regeneration from aerial explants starts with the elimination of leaf identity in above-ground or aerial explants [19, 20] and then root and shoot identities [21, 22] needs to be re-established in both aerial and root explants, followed by de novo plant regeneration via somatic embryogenesis or organogenesis (Figure 1). The elimination of leaf identity is mainly achieved via epigenetic changes (see below). The establishment of lateral root identity occurs in pericycle-like cells of aerial explants or xylem-pole pericycle cells of root explants, permitting the middle cell layer of the pericycle-like cells to obtain pluripotency and develop into pericycle founder cells for callus induction [14, 22]. This includes the activation of expression of ABERRANT LATERAL ROOT FORMATION4 (ALF4), the gene required for the first asymmetric division of pericycle cells during lateral root initiation, and RAM developmental regulatory genes such as PLETHORA1 (PLT1) and PLT2, WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX5 (WOX5), SHORT-ROOT (SHR), and SCARECROW (SCR) [14]. Kareem et al. [21] found that transcription factors PLT3, PLT5, and PLT7 activate the expression of PLT1 and PLT2 to establish pluripotency. Moreover, PLT3, PLT5, and PLT7 activate the expression of the shoot-promoting factor CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON2 (CUC2) via PLT-mediated upregulation of auxin biosynthesis genes YUCCA1 (YUC1) and YUC4, leading to shoot regeneration [60].

There are many genetic and environmental factors that can affect plant regeneration; among them, these four types of regeneration-promoting factors play essential roles: wounding, epigenetic modifications, growth regulatory genes, and developmental regulatory genes (Figure 1). By inducing a series of physical and chemical changes in the detached explants, wounding is the primary external trigger of callus induction from explants [5, 14]. These changes start with the perception of damage-associated molecular patterns such as extracellular ATP [61, 62] and cell wall-derived oligogalacturonic acid [63], triggering cytoplasmic calcium signaling and a burst of reactive oxygen species [61, 62]. These local wounding signals are translated into long-distance signals such as the electrical signal of cation channel GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKEs, inducing epigenetic modifications, alternations in the synthesis and accumulation of cytokinin and free auxin, and transcriptional upregulation of growth and developmental regulatory genes [10, 64] (Figure 1). Transcriptional changes include the activation of expression of callus-inductive chromatin remodeling regulator genes POLYCOMB REPRESSIVE COMPLEX2 (PRC2; see below), cell cycle genes CYCLINs (CYCs) and CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASES (CDKs), cytokinin biosynthesis gene ISOPENTENYL TRANSFERASE (IPT), auxin biosynthesis gene YUC5, and AP2/ERF transcription factors WOUND-INDUCED DEDIFFERENTIATION1 ~ 4 (WIND1 ~ 4) and ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 (ESR1) [64, 65]. Among these, activation of expression of CYCs and CDKs triggers cells to reenter the cell cycle and reacquire cell proliferative competence, a central mechanism of callus induction [66], whereas WINDs promote callus induction by directly binding to the promoter of ESR1 and upregulating its expression [67].

Epigenetic modifications of chromatin structure cause genome-wide changes in gene expression required for callus induction [11, 19, 20, 68]. This global reprogramming of epigenetic modifications includes changes in genome-wide DNA methylation (especially gene promoter DNA methylation), histone modifications in transcription start sites (TSSs) and other gene parts, and deposition of histone variants. For example, He et al. [19] discovered that genome-wide reprogramming of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) is critical in the leaf-to-callus transition since the Arabidopsis thaliana prc2 (a key gene in establishing H3K27me3) mutants were defective in callus formation. The PRC2-mediated global epigenetic changes are directly involved in the elimination of the leaf identity in aerial explants by silencing leaf-regulatory genes while removing the repressive methyl marks on auxin pathway genes YUC4 and AUXIN/INDOLE3-ACETIC ACID2 (AUX/IAA2) and root-regulatory genes WOX5 and SHR [19]. PRC2-dependent repressive histone modifications also control expression of wounding-responsive WIND genes [69], which promote callus induction by activating the cytokinin biosynthesis pathway via the upregulation of type-B ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR (ARR-B) gene expression [70]. Lee et al. [20] found that AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR7/9 (ARF7/9) and JUMONJI C DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN 30 (JMJ30) form the ARF-JMJ30 complexes to remove the methyl groups from H3K9me3 at LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES-DOMAIN16 (LBD16) and LBD29, leading to the activation of the expression of LBD16 and LBD29 for the establishment of lateral root identity. Lee et al. [71] revealed that the expression of chromatin modifier ARABIDIPSIS TRITHORAX4 (ATX4) is repressed during callus induction to eliminate leaf identity but is reactivated to facilitate shoot identity establishment by removing the methyl groups from H3K4me3 at shoot identity genes such as KNOTTED1-LIKE HOMEOBOX GENE 4 (KNAT4) and YABBY 5 (YAB5). In addition, epigenetic reprogramming also provides local changes in the epigenetic states of key genes involved in callus induction and plant regeneration. These key genes include WIND3, BABY BOOM (BBM), LEAFY COTYLEDON1 (LEC1) and LEC2, and WOX5/11 genes [11]. All of these epigenetic modifications prepare explants for callus induction and are involved in all of the steps of callus induction and plant regeneration (Figure 1).

Cytokinins and auxins are critical for and routinely used in callus induction and plant regeneration. A balanced cytokinin and auxin ratio promotes callus induction, while high and low cytokinin-to-auxin ratios tend to induce shoot and root formation, respectively [72]. For example, endogenous auxin production and enhanced cytokinin sensitivity promote pluripotency acquisition in the middle cell layer of pericycle cells for organ regeneration [22]. In the middle cell layer of pericycle cells, endogenous auxin production increases through induced expression of TRYPTOPHAN MONOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS1 (TAA1) by WOX5, PLT1 and PLT2, while cytokinin sensitivity increases through repression of ARRs-A by WOX5 and type-B ARR12. Hu et al. [73] also found that elevated endogenous auxin levels in the basal end of citrus epicotyl cuttings inhibit in vitro shoot organogenesis in a cytokinin-dependent manner. Similarly, genetic components of the biosynthesis and signaling pathways of cytokinin and auxin regulate callus formation and plant regeneration [54, 74–77]. For example, cytokinin induces expression of the D-type cyclin CYCD3 gene, whose overexpression induces callus formation in the absence of cytokinin [78]. Cytokinin also induces expression of the transcription factor gene SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM), whose protein maintains cell division and inhibits cell differentiation in SAM and enhances cytokinin levels via activation of IPT7 [79]. The overexpressed A. tumefaciens IPT gene in transgenic tobacco and cucumber induces cytokinin biosynthesis, resulting in the promotion of shoot organogenesis [77]. In addition, YUC-mediated auxin biosynthesis increases the total auxin level in leaf explants, and when polar auxin transport delivers auxin to regeneration-competent cells, it triggers WOX11 and WOX12 expression [74, 80]. WOX11 and WOX12 directly bind to the promoters of WOX5 and WOX7 and induce their expression for rapid root primordia initiation and root identity establishment [74, 80]. Auxin also inhibits the expression of type-A ARR7 and ARR15 via the auxin response transcription factor MONOPTEROS (MP) [ 81]. ARR-As negatively regulate ARR-Bs expression and thus repress cytokinin-mediated signaling [82].

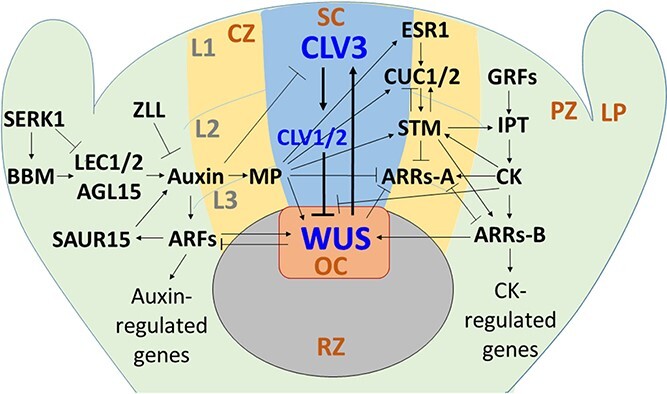

Plant developmental regulatory genes also play key roles in callus formation and plant regeneration, as these processes are orchestrated by the sequential and spatiotemporal expression of various developmental regulatory genes driving morphogenesis [2–4, 83]. The most well-known developmental regulatory gene is WUSCHEL (WUS), the first gene identified in the WOX gene family and the essential player in both organogenesis [84] and embryogenesis [85]. As a homeodomain transcription factor, WUS is synthesized in the organizing center (OC) of the SAMs and migrates into the central zone (CZ) where it activates CLAVATA3 (CLV3) transcription, which in turn inhibits WUS expression in the OC [86, 87] (Figure 2). The WUS-CLV3 negative feedback circuit regulates cell identity and maintains the existence of the OC and the shoot stem cell niche in the CZ (Figure 2). Su et al. [88] revealed that the activation of WUS transcription by auxin gradients results in the induction of embryogenic callus and somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis explants under in vitro culture conditions. Zhang et al. [89] demonstrated that the activation of WUS expression in Arabidopsis explants by the ARR-Bs/HD-ZIP III transcription factor complex in a cytokinin 2-isopentenyladenine (2-IP)-rich environment promotes organogenesis and shoot regeneration. As a result, both auxin and cytokinin activate WUS expression (Figure 1). In addition, various developmental transcription factor genes are involved in organogenesis and/or embryogenesis. These include STM [84,90], MP/ARF5 [91,92], LEC1/2 [93,94], CUC1 [90], ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3) [94, 95], FUSCA3 (FUS3) [94, 96], AINTEGUMENTA (ANT) [97], WOX12 [80], and CYCD3 [98].

Figure 2.

Shoot apical meristem (SAM), the WUS-CLV3 negative feedback loop, and the growth and developmental regulatory genes currently known to improve plant transformation efficiency. LP, leaf primordia; PZ, peripheral zone; CZ, central zone; SC, stem cells; OC, organizing center; RZ, rib zone; L1 – L3, cell layer 1–3.

These regeneration-promoting factors work together to control each step of callus formation and plant regeneration tightly and precisely (Figure 1). However, how these factors cooperate in plant regeneration is largely unknown.

The use of plant developmental regulatory genes in plant transformation

As the most important developmental regulatory gene for the maintenance of the stem cell niche in SAMs, WUS has been used for plant transformation and regeneration in multiple species. Ectopic or estradiol-inducible expression of the A. thaliana WUS (AtWUS) gene (Figure 3A) in transgenic Arabidopsis, tobacco, Gossypium hirsutum, and Coffea canephora induced vegetative-to-embryogenic transition in vegetative tissues, which could differentiate into somatic embryos [23, 24, 26, 85] or organs [84]. However, the resulting transgenic plants exhibited abnormal phenotypes such as coiled root tips, cotton-like root structures, swollen hypocotyls, and distorted leaves [24, 26]. These abnormalities indicate WUS expression needs to be under a tight control since both cytokinin and auxin signaling pathways regulate its expression and its continuous overexpression causes malformations and alterations in transgenic plant growth. WOX genes such as AtWOX2/5/8/9 have also been used individually for tobacco transformation in estradiol-inducible systems, resulting in transgenic plants with abnormal phenotypes such as dwarf plants or bulbous roots [28]. Since CLV1 works as the receptor for the secreted ligand CLV3 that negatively regulates WUS expression in the OC (Figure 2), RNAi-mediated silencing of the Brassica napus CLV1 led to an increase in genetic transformation efficiency in transgenic B. napus and triggered a bushy phenotype [99]. Therefore, strategies are needed to fine-tune WUS/WOXs and CLV1 expression to obtain normal transgenic plant regeneration (see below).

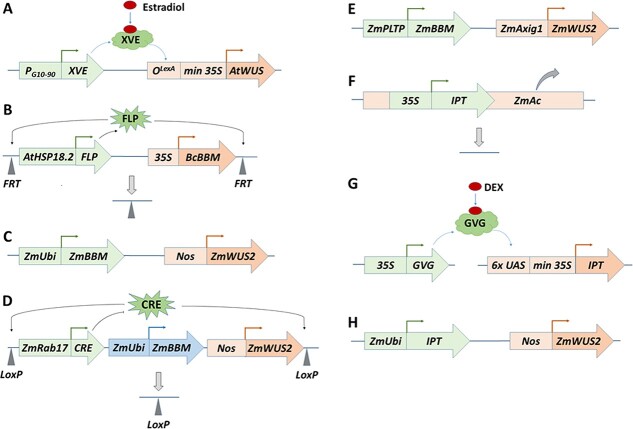

Figure 3.

Structures and mechanisms of the expression vectors that utilized growth and developmental regulatory genes in plant transformation. (A) Estradiol-inducible AtWUS expression for transformation of Coffea canephora [26]. The XVE fusion gene driven by the constitutive PG10–90 promoter contains the DNA-binding domain of the bacterial repressor LexA, the activation domain of the herpes viral protein VP16, and the carboxyl region of the human estrogen receptor. The binding of the estrogen hormone to the estrogen receptor in XVE enables XVE to bind to OLexA, the eight copies of the LexA operator sequence, leading to expression of AtWUS driven by OLexA and a minimal 35S promoter. (B) A heat shock inducible-excision system to control BcBBM expression in transgenic Chinese white poplar [37]. Heat shock treatment on the stem cuttings of transgenic Chinese white poplar activates expression of the yeast FLP recombinase that is driven by the heat shock-inducible promoter AtHSP18.2, leading to the removal of the AtHSP18.2:FLP and 35S:BcBBM cassette with one footprint (a single FRT recombination site) left in the transgenic genome. (C) Low expression of ZmWUS2 under the control of the weak Agrobacterium nopaline synthase promoter (Nos:ZmWUS2) and high expression of ZmBBM driven by the strong maize Ubiquitin promoter (ZmUbi:ZmBBM) for transformation of maize and sorghum [15]. (D) A desiccation-inducible excision system to control Nos:ZmWUS2 and ZmUbi:ZmBBM expression in transgenic maize and sorghum [15]. Desiccation of the embryogenic calli activates the expression of the CRE recombinase driven by the desiccation-inducible ZmRab17 promoter, leading to the removal of Nos:ZmWUS2, ZmUbi:ZmBBM and ZmRab17:CRE, with one footprint (a single LoxP recombination site) left in the transgenic genome. (E) Conditional expression of the ZmWUS2 and ZmBBM by the auxin-inducible promoter ZmAxig1 and the maize embryo/leaf-specific promoter ZmPLTP, respectively, for maize transformation [38]. (F) A selectable marker-free transformation system in tobacco and hybrid aspen [57]. The 35S:IPT-containing Ac transposase gene can automatically jump out of the chromosome, leaving no footprint in the transgenic genome. (G) Dexamethasone (Dex)-inducible IPT expression for transformation of tomato and lettuce [58]. The GVG fusion gene driven by the 35S promoter contains the DNA-binding domain of the yeast transcription factor GAL4, the activation domain of VP16, and the hormone-binding domain of the rat Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR). Exogenous application of the synthetic glucocorticoid DEX releases GVG into the nucleus, where it binds to the 6× UPS binding sites of GAL4 and activates the expression of AtWUS driven by 6× UPS and a minimal 35S promoter. (H) Low expression of ZmWUS2 (Nos:ZmWUS2) plus high expression of the Agrobacterium IPT (ZmUbi:IPT) for organogenesis in the seedling leaves of Arabidopsis, tobacco, and tomato, and in the mature plants of tobacco, potato and grape [59].

BBM, an APETALA2 (AP2)/ETHYLENE RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTOR (AP2/ERF) transcription factor, is another developmental regulatory gene involved in somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis via the auxin signaling pathway [32, 100, 101] (Figure 2). Khanday et al. [100, 102] reported that exogenous auxin-induced somatic embryogenesis in rice requires the presence of functional rice BBM (OsBBM) genes and the overexpression of OsBBM1 promotes somatic embryogenesis without the use of exogenous auxins, suggesting the OsBBM overexpression increases endogenous auxin production. Moreover, overexpression of BBM genes activates somatic embryo formation and/or regeneration in transgenic tobacco [30], B. napus [32], and Theobroma cacao [33]. However, like the side effects of WUS/WOXs overexpression, plants overexpressing BBMs exhibit pleiotropic phenotypes such as mild-to-severe alterations in leaf and flower morphology.

A dexamethasone (Dex)-inducible expression system has also been used to drive the expression of BBM genes, which were fused in-frame with the hormone-binding domain of the rat glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene [30, 35]. This resulted in transgenic tobacco [30] and T. cacao [35] with normal phenotypes, but caused thickened roots, pronounced apical hooks, and swelled cotyledons in transgenic Capsicum annuum [36]. Moreover, Deng et al. [37] used an inducible excision system (Figure 3B) to control the B. campestris BBM (BcBBM) overexpression in the calli of Chinese white poplar (Populus tomentosa). The site-directed recombination system containing the recombinase flippase and flippase recognition target (FRT) sites (FLP/FRT) from yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was under the control of the Arabidopsis heat shock-inducible promoter AtHSP18.2. Heat shock treatment on the transgenic stem cuttings caused the removal of the AtHSP18.2:FLP and 35S:BcBBM cassette (Figure 3B) and produced transgenic plants with normal phenotypes. It was expected that high expression of BBM induces somatic embryogenesis while low expression of BBM promotes organogenesis as reduced cell differentiation was observed in low expression lines in transgenic Arabidopsis [94].

The upstream and downstream genes in the BBM-regulated somatic embryogenesis developmental pathway have also been examined for their roles in plant transformation. SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE1 (SERK1), a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK) gene, regulates somatic embryogenesis by early activation of auxin biosynthesis, leading to the activation of expression of WUS, BBM, and the MADS-box transcription factor AGAMOUS-LIKE15 (AGL15) as well as to the repression of expression of LEC1 [41]. CcSERK1 has been used in C. canephora transformation, but attempts to generate transgenic plants were unsuccessful [41]. Transcription factors LEC1 and LEC2, two downstream proteins in the BBM-regulated somatic embryogenesis development pathway [94], work redundantly with LEC1-LIKE (L1L) and the B3 domain proteins ABI3 and FUS3 in embryogenesis [103]. LEC1 and LEC2 have been used for transformation of Picea abies [42], T. cacao [35], and tobacco [24], and the estradiol-inducible expression of AtLEC2 resulted in the regeneration of transgenic tobacco plants with curved root tips [24]. Since LEC2 directly activates the expression of AGL15, Thakare et al. [43] found that overexpression of GmAGL15 increases soybean transformation efficiency by two-fold but resulted in abnormal phenotypes in the transgenic plants. Small auxin-upregulated RNA15 (SAUR15) is an auxin-inducible negative regulator in embryogenic callus induction, and its homozygous Mu transposon insertion mutant in maize (zmsaur15) exhibited 5 times higher transformation efficiency than the wild-type maize [104].

A recent groundbreaking study was published for monocot transformation through somatic embryogenesis by fine-tuning the expression of WUS and BBM [15]. Low expression of the maize WUS2 gene by the Agrobacterium nopaline synthase promoter (Nos:ZmWUS2), a weak promoter for monocots, and high expression of the maize BBM by the strong maize Ubiquitin promoter (ZmUbi:ZmBBM) induced somatic embryogenesis and regeneration of fertile transgenic plants in immature embryos and/or callus of maize, sorghum, sugarcane and rice (Figure 3C). This approach significantly increased callus transformation efficiency, shortened regeneration time, and made various non-transformable genotypes transformable [15, 16]. For example, combined expression of Nos:ZmWUS2 and ZmUbi:ZmBBM dramatically increased transformation efficiency from 0.0–2.0% to 25.3–51.7% in four transformation-recalcitrant maize inbred lines and made another 33 out of 50 commercially important Pioneer maize inbred lines transformable [15]. However, the continuous expression of both regulatory genes caused aberrant phenotypes such as stunted, twisted, sterile plants with thick, short roots. Lowe et al. [15] designed an inducible excision strategy to remove Nos:ZmWUS2 and ZmUbi:ZmBBM in the transformed embryogenic calli by using the tyrosine recombinase CRE from the P1 bacteriophage and its recognition site LoxP (Figure 3D). Drying the embryogenic calli on filter paper for three days activated CRE expression driven by the desiccation-inducible maize promoter ZmRab17, leading to the removal of the transgenes (WUS2, BBM, and CRE) located between the two LoxP sites on the T-DNA (Figure 3D). The removal resulted in healthy, fertile T0 transgenic plants [15]. The effectiveness of this strategy was also confirmed in previously non-transformable maize and sorghum varieties [16, 17].

Moreover, Lowe et al. [38] replaced the ZmUbi promoter with a maize phospholipid transferase promoter ZmPLTP to drive BBM expression (Figure 3E); ZmPLTP has strong expression in maize embryos and leaves but low expression in ears and tassels, and undetectable expression in roots. Combined expression of Nos:ZmWUS2 and ZmPLTP:ZmBBM in immature zygotic embryos induced the formation of somatic embryos in one week, which directly developed into healthy fertile plants without callus formation. This strategy significantly shortened the transformation process since the desiccation-inducible excision method in Lowe et al. [15] requires three months of callus induction. Since the T1 seeds continuously expressing Nos:ZmWUS2 showed inconsistent germination, Lowe et al. [38] also replaced the Nos promoter with the maize auxin-inducible ZmAxig1 promoter to drive ZmWUS2 expression (Figure 3E). The expression levels of ZmAxig1:ZmWUS2 and ZmPLTP:ZmBBM were specific and low in non-embryogenic and un-induced tissues under the control of these two maize promoters, resulting in rapid somatic embryo development without callus formation so that excision is not needed to generate phenotypically normal transgenic plants. The resulting callus-free transformation approach has made all seven tested maize genotypes highly transformable [38], indicating the primary function of WUS and BBM in cell proliferation other than callus formation. Interestingly, it was recently shown that ZmPLTP:ZmWUS2 alone is sufficient to promote somatic embryogenesis and transformation of recalcitrant maize varieties in a non-cell autonomous fashion, i.e. WUS2 expression in a transformed cell could stimulate somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in neighboring cells [39]. Hoerster et al. [39] conducted maize transformation by using the mixture of two strains of A. tumefaciens containing ZmPLTP:ZmWUS2 or selectable and visual marker cassettes, and obtained T0 transgenic maize plants expressing the selectable marker gene but did not contain ZmWUS2. Similarly, Aregawi et al. [40] conducted sorghum transformation by using the mixture of two strains of A. tumefaciens with one containing ZmPLTP:ZmWUS2 and ZmPLTP:ZmBBM and the other one containing selectable marker cassettes, and obtained T0 transgenic sorghum plants expressing the selectable marker gene but did not contain ZmWUS2 and ZmBBM. This approach shortened sorghum transformation time by nearly half and made several previously untransformable genotypes transformable.

STM, a KNOX homeodomain transcription factor, is expressed in SAMs and prevents the differentiation of the meristematic cells [105]. STM induces expression of IPT7, a cytokinin biosynthesis gene, leading to an increased cytokinin level [79, 106] (Figure 1). Overexpression of the maize STM homolog Knotted1 (ZmKn1) in transgenic citrus significantly increased citrus transformation efficiency 3 ~ 15 times [48]. ZmKn1 overexpression in transgenic tobacco significantly increased transformation efficiency by 3 times via organogenesis on a hormone-free medium without antibiotic selection [47]. However, overexpression of STM homologs resulted in the regeneration of transgenic tobacco plants with a bushy phenotype [46, 47]. In addition, overexpression of CUC1 and CUC2 that positively regulate SAM formation via STM-dependent (and STM-independent) pathways resulted in enhanced transformation efficiency of Arabidopsis by 10 times via a tissue culture method, and the resulting transgenic plants showed phenotypic abnormalities [49]. The estradiol-inducible expression of ESR2, an AP2-domain transcription factor, also enhanced Arabidopsis tissue culture transformation by directly regulating CUC1 transcription [52].

Transcription factor MP, a mediator of auxin responses and regulator of cytokinin signaling and biosynthesis, can also be leveraged to increase transformation efficiency [107, 108]. When the regulatory domain of MP is removed, the resultant MPΔ becomes irrepressible but maintains the normal MP function. Overexpression of AtMPΔ increased transformation efficiency in transgenic Arabidopsis with abnormal phenotypes via the upregulation of expression of AtWUS, AtSTM, AtESR1, AtCUC1 and AtCUC2 [54,107] and repression of type-A ARR5 and ARR7 [81].

In contrast to the negative pleiotropic effects of overexpression of the aforementioned genes (i.e. WUS, WOXs, BBM, SERK1, LEC1/2, AGL15, STM/Kn1, CUC1/2, ESR2, and MPΔ) and silencing/knockout of CLV1 and SAUR15, constitutive expression of a small family of transcription factor genes GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR (GRF) and its transcriptional cofactor GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR1 (GIF) does not cause observed undesirable phenotypes in transgenic plants [55, 56], making conditional expression or excision of the transgenes unnecessary. During callus induction and plant regeneration, the miR396-regulated GRF-GIF duo can recruit SWITCH/SUCROSE NONFERMENTING (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeling complexes to regulate expression of their target genes and specify meristematic identity for organogenesis [109–111]. For example, poplar PpnGRF5–1 forms a complex with PpnGIFs and then inhibits expression of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase1 (PpnCKX1), which is a membrane-bound protein catalyzing the degradation of cytokinins [112], leading to the accumulation of cytokinins and meristematic induction [113] (Figure 2). Kong et al. [55] found that the overexpression of AtGRF5 or its homologs from various plant species enhanced shoot organogenesis and transformation efficiency in transformation-recalcitrant sugar beet, canola, soybean, and sunflower, and promoted somatic embryogenesis and transformation efficiency in maize. When compared to the control plants, a 4.5 ~ 11.5-, 1.9 ~ 2.3- and 1.1 ~ 1.4-fold increase in transformation efficiency was achieved in sugar beet, canola, and soybean, respectively. The resultant transgenic plants showed normal phenotypes. Debernardi et al. [56] demonstrated that overexpression of the wheat GRF4-GIF1 chimeric gene dramatically increases transformation efficiency and regenerates fertile transgenic plants with normal phenotypes in multiple plant species without the use of exogenous cytokinins. These species included wheat, rice, citrus as well as some difficult- or recalcitrant-to-transform species/genotypes such as commercial durum, bread wheat and a triticale line [56]. Most importantly, it was shown that overexpression of GRF4-GIF1 chimera increased the regeneration efficiency by an average of 7.8-fold and shortened the transformation process time from 91 days to 56 days in the wheat genotypes, permitting transgenic shoot selection in auxin media without using antibiotic selectable marker genes. Since there are multiple members in the GRF-GIF families, and not all GRFs or GRF-GIF pairs work equally effectively in plant transformation, research needs to be conducted to identify the GRFs or GRF-GIF pairs that have high transformation efficiency in a given economically important crop.

The use of plant growth regulatory genes in plant transformation

The IPT gene from the Ti-plasmids of A. tumefaciens catalyzes the formation of isopentenyl-adenosine-5-monophosphate (isopentenyl-AMP), the first intermediate in the cytokinin biosynthesis pathway, resulting in elevated cytokinin levels [114, 115] (Figure 2). Overexpression of an Agrobacterium IPT gene enhanced cytokinin level 23 ~ 300 times, resulting in a 24 ~ 2,000-fold increase in the cytokinin-to-auxin ratios in tobacco and cucumber [116, 117]. The abnormal phenotypes of the transgenic plants included loss of apical dominance and a poor ability to root, reduced internode elongation, and altered leaf morphology [116–118]. To overcome the negative phenotypic effects, Ebinuma et al. [57] developed a selectable marker-free transformation system by inserting the 35S:IPT cassette into an Ac-element from maize (Figure 3F) for transformation of tobacco and hybrid aspen (Populus sieboldii × P.grandidentata). Following the somatic self-excision of the IPT-containing Ac-element in the hemizygous transgenic lines where the retroelement failed to integrate into the sister chromatin, normal marker-free shoots were obtained at a frequency of 0.5 ~ 1.0%. Kunkel et al. [58] used the IPT gene for antibiotic marker-free tobacco and lettuce transformation by using a Dex-inducible IPT expression system (Figure 3G). The induced IPT expression improved transformation efficiency by 24.3 and 6.6 times in tobacco and lettuce, respectively, and produced transgenic plants without observed morphological defects.

Using Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression, a recent breakthrough in callus-free plant regeneration of multiple species was published [59]. This work revealed that low expression of ZmWUS2 (Nos:ZmWUS2) plus high expression of the Agrobacterium IPT (ZmUbi:IPT) or ZmUbi:AtSTM (Figure 3H) promoted organogenesis in aseptically grown seedling leaves of Arabidopsis, tobacco, and tomato, and in mature plants of tobacco, potato and grape [59]. When used together with a Cas9/gRNA plasmid, this novel approach produced gene-edited shoots without the use of tissue culture, offering great potential to speed up the breeding cycles for many plant species [59]. This tissue culture-free approach provides a good tool to test the effects of different candidate genes and regulatory elements on plant transformation.

Conclusion and future perspectives

With the demonstration of the dramatic effects of growth and developmental regulatory genes in plant tissue culture and transformation, regulatory genes have emerged as innovative, game-changing tools in plant transformation. These regulatory genes have been demonstrated to work efficiently in dicots, monocots and gymnosperms (Table 1) and are expected to work in various plants including specialty crops such as potato, sweetpotato, tomato and ornamentals. They offer excellent opportunities to develop genotype-independent genetic transformation methods and gene editing approaches in specialty crops.

In addition to the genes discussed above, many other upstream and downstream interacting factors promote meristem formation, shoot regeneration, or somatic embryogenesis, but have yet to be developed for use in plant transformation. These include PLTs [21], WINDs [65,119], ARRs [120], ABI3 [121], FUS3 [121], LILs [122], AGL18 [123], Pollen ole e 1 (POE1) [124], EMBRYO SAC DEVELOPMENT ARREST (EDA40) [124], SUPERMAN (SUP) [124, 125], and AT-HOOK MOTIF CONTAINING NUCLEAR LOCALIZED 15 (AHL15) [126]. Research needs to be conducted to fine-tune the expression of each of these genes to examine their effects on plant regeneration and transformation.

Future research to identify additional growth and developmental regulatory genes and novel regulatory network looks promising. Various combinations of different growth and developmental regulatory genes need to be tested rationally for their synergistic and additive effects on plant transformation. Fine-tuning the expression of these genes is critical for the regeneration of normal, fertile plants in different plant species since their constitutive/ectopic expression typically interferes with normal plant growth and development and causes undesirable pleiotropic effects. Strategies to counter these pleiotropic effects include tissue- or growth stage-specific expression, inducible or conditional expression, or removal of the transgenes. Synthetic promoters or devices could be used to conditionally express the regulatory genes [127, 128]. T-DNA read through-based transient expression [129] is also worth further testing. In addition, protein or DNA-free delivery of the regulatory proteins could be explored for their effects on plant transformation and regeneration, which could be conducted in explants cultured on callus induction media, in protoplasts [130], or suspension cells [131]. Transient or protein delivery of these regulatory genes could enable DNA-free approaches for the generation of engineered crop cultivars, which will minimize regulations and public opposition. No matter the genes or the delivery and regeneration systems, the success of next-generation agriculture will greatly depend on our ability to expand transgenic capabilities to previously recalcitrant species and elite genotypes. The recent progress in this exciting area of plant science provides an optimistic outlook for the future of crop transformation.

Contributor Information

Nathan A Maren, Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 27607, USA.

Hui Duan, USDA-ARS, U.S. National Arboretum, Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit, Beltsville Agricultural Research Center (BARC)-West, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA.

Kedong Da, Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 27607, USA.

G Craig Yencho, Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 27607, USA.

Thomas G Ranney, Mountain Crop Improvement Lab, Department of Horticultural Science, Mountain Horticultural Crops Research and Extension Center, North Carolina State University, Mills River, NC 28759, USA.

Wusheng Liu, Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 27607, USA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Yi Li, Qiudeng Que, Guo-Qing Song, Mitra Mazarei, Anna Stepanova, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. This work was financially supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) - Agriculture Research Service (ARS) Base funds to D. H., and the USDA Floriculture and Nursery Research Initiative (FNRI) grant # 8020–21000-071-23S and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Hatch project 02685 to W. L.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

References

- 1. Altpeter F, Springer NM, Bartley LEet al. Advancing crop transformation in the era of genome editing. Plant Cell. 2016;28:1510–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gordon-Kamm B, Sardesai N, Arling Met al. Using morphogenic genes to improve recovery and regeneration of transgenic plants. Plan Theory. 2019;8:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nagle M, Dejardin A, Pilate G, Strauss SH. Opportunities for innovation in genetic transformation of forest trees. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nalapalli S, Tunc-Ozdemir M, Sun Yet al. Morphogenic regulators and their application in improving plant transformation. In: Bandyopadhyay A, Thilmony R, eds. Rice Genome Engineering and Gene Editing. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 2238. Humana: New York, NY, 2021,37–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Atta R, Laurens L, Boucheron-Dubuisson Eet al. Pluripotency of Arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro. Plant J. 2009;57:626–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feher A. Callus, dedifferentiation, totipotency, somatic embryogenesis: what these terms mean in the era of molecular plant biology? Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaillochet C, Lohmann JU. The never-ending story: from pluripotency to plant developmental plasticity. Development. 2015;142:2237–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steward FC, Mapes MO, Mears K. Growth and organized development of cultured cells. II. Organization in cultures grown from freely suspended cells. Am J Bot. 1958;45:705–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu C, Hu Y. The molecular regulation of cell pluripotency in plants. aBIOTECH. 2020;1:169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ikeuchi M, Ogawa Y, Iwase A, Sugimoto K. Plant regeneration: cellular origins and molecular mechanisms. Development. 2016;143:1442–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee K, Seo PJ. Dynamic epigenetic changes during plant regeneration. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;23:235–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sugimoto K, Gordon SP, Meyerowitz EM. Regeneration in plants and animals: dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation, or just differentiation? Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hicks GS. Shoot induction and organogenesis in vitro: a developmental perspective. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 1994;30P:10–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sugimoto K, Jiao Y, Meyerowitz EM. Arabidopsis regeneration from multiple tissues occurs via root development pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;18:463–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lowe K, Wu E, Wang Net al. Morphogenic regulators baby boom and Wuschel improve monocot transformation. Plant Cell. 2016;28:1998–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mookkan M, Nelson-Vasilchik K, Hague Jet al. Selectable marker independent transformation of recalcitrant maize inbred B73 and sorghum P898012 mediated by morphogenic regulators BABY BOOM and WUSCHEL2. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:1477–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mookkan M, Nelson-Vasilchik K, Hague Jet al. Morphogenic regulator-mediated transformation of maize inbred B73. Curr Protoc Plant Biol. 2018;3:e20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Lu M-Het al. A novel ternary vector system united with morphogenic genes enhances CRISPR/Cas delivery in maize. Plant Physiol. 2019;181:1441–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He C, Chen X, Huang H, Xu L. Reprogramming of H3K27me3 is critical for acquisition of pluripotency from cultured Arabidopsis tissues. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee K, Park O-S, Seo PJ. JMJ30-mediated demethylation of H3K9me3 drives tissue identity changes to promote callus formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2018;95:961–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kareem A, Durgaprasad K, Sugimoto Ket al. PLETHORA genes control regeneration by a two-step mechanism. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1017–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhai N, Xu L. Pluripotency acquisition in the middle cell layer of callus is required for organ regeneration. Nat Plants. 2021;7:1453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bouchabké-Coussa O, Obellianne M, Linderme Det al. Wuschel overexpression promotes somatic embryogenesis and induces organogenesis in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) tissues cultured in vitro. Plant Cell Rep. 2013;32:675–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rashid SZ, Yamaji N, Kyo M. Shoot formation from root tip region: a developmental alteration by WUS in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26:1449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamaji N, Kyo M. Two promoters conferring active gene expression in vegetative nuclei of tobacco immature pollen undergoing embryogenic dedifferentiation. Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25:749–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arroyo-Herrera A, Ku-González A, Canche Ret al. Expression of WUSCHEL in Coffea canephora causes ectopic morphogenesis and increases somatic embryogenesis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2008;94:171–80. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Acereto-Escoffie PO, Chi B, Echeverría-Echeverría Set al. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Musa acuminate cv. “Grand Nain” scalps by vaccum infiltration. Sci Hortic. 2005;105:350–71. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kyo M, Maida K, Nishioka Y, Matsui K. Coexpression of WUSCHEL related homeobox (WOX) 2 with WOX8 or WOX9 promotes regeneration from leaf segments and free cells in Nicotiana tabacum L. Plant Biotechnol (Tokyo). 2018;35:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mursyanti E, Purwantoro A, Moeljopawiro S, Semiarti E. Induction of somatic embryogenesis through overexpression of ATRKD4 genes in Phalaenopsis “Sogo Vivien”. Indones J Biotechnol. 2016;20:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Srinivasan C, Liu Z, Heidmann Iet al. Heterologous expression of the BABY BOOM AP2/ERF transcription factor enhances the regeneration capacity of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Planta. 2007;225:341–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fraley RT, Rogers SG, Horsch RBet al. Expression of bacterial genes in plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4803–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boutilier K, Offringa R, Sharma VKet al. Ectopic expression of BABYBOOM triggers a conversion from vegetative to embryonic growth. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1737–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Florez SL, Erwin RL, Maximova SNet al. Enhanced somatic embryogenesis in Theobroma cacao using the homologous BABY BOOM transcription factor. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Z, Traore A, Maximova S, Guiltinan MJ. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from floral explants of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) using thidiazuron. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 1998;34:293–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shires ME, Florez SL, Lai TS, Curtis WR. Inducible somatic embryogenesis in Theobroma cacao achieved using the DEX-activatable transcription factor-glucocorticoid receptor fusion. Biotechnol Lett. 2017;39:1747–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heidmann I, Lange B, Lambalk Jet al. Efficient sweet pepper transformation mediated by the BABY BOOM transcription factor. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30:1107–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Deng W, Luo K, Li Z, Yang Y. A novel method for induction of plant regeneration via somatic embryogenesis. Plant Sci. 2009;177:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lowe K, la Rota M, Hoerster Get al. Rapid genotype “independent” Zea mays L. (maize) transformation via direct somatic embryogenesis. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol Plant. 2018;54:240–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoerster G, Wang N, Ryan Let al. Use of non-integrating Zm-Wus2 vectors to enhance maize transformation. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2020;56:265–79. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aregawi K, Shen J, Pierroz Get al. Morphogene-assisted transformation of Sorghum bicolor allows more efficient genome editing. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021. 10.1111/pbi.13754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perez-Pascual D, Jiménez-Guillen D, Villanueva-Alonzo Het al. Ectopic expression of the Coffea canephora SERK1 homolog-induced differential transcription of genes involved in auxin metabolism and in the developmental control of embryogenesis. Physiol Plant. 2018;163:530–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Uddenberg D, Abrahamsson M, Arnold S. Overexpression of PaHAP3A stimulates differentiation of ectopic embryos from maturing somatic embryos of Norway spruce. Tree Genet Genomes. 2016;12:18. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thakare D, Tang W, Hill K, Perry SE. The MADS-domain transcriptional regulator AGAMOUS-LIKE15 promotes somatic embryo development in Arabidopsis and soybean. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang Z, Li C, Wang Yet al. GhAGL15s, preferentially expressed during somatic embryogenesis, promote embryogenic callus formation in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Mol Gen Genomics. 2014;289:873–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Elhiti M, Tahir M, Gulden RHet al. Modulation of embryo-forming capacity in culture through the expression of brassica genes involved in the regulation of the shoot apical meristem. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:4069–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nishimura A, Tamaoki M, Sakamoto T, Matsuoka M. Over-expression of tobacco knotted 1-type class1 homeobox genes alters various leaf morphology. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Luo K, Zheng X, Chen Yet al. The maize Knotted1 gene is an effective positive selectable marker gene for agrobacterium-mediated tobacco transformation. Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25:403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hu W, Li W, Xie Set al. Kn1 gene overexpression drastically improves genetic transformation efficiencies of citrus cultivars. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016;125:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Daimon Y, Takabe K, Tasaka M. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes promote adventitious shoot formation on calli. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Akama K, Shiraishi H, Ohta Set al. Efficient transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana: comparison of the efficiencies with various organs, plant ecotypes and agrobacterium strains. Plant Cell Rep. 1992;12:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Banno H, Ikeda Y, Niu Q-W, Chua N-H. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ESR1 induces initiation of shoot regeneration. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ikeda Y, Banno H, Niu Q-Wet al. The ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 2 gene in Arabidopsis regulates CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 1 at the transcriptional level and controls cotyledon development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:1443–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Valvekens D, Montagu M, Lijsebettens M. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana root explants by using kanamycin selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5536–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ckurshumova W, Smirnova T, Marcos Det al. Irrepressible MONOPTEROS/ARF5 promotes de novo shoot formation. New Phytol. 2014;204:556–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kong J, Martin-Ortigosa S, Finer Jet al. Overexpression of the transcription factor GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR5 improves transformation of dicot and monocot species. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:572319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Debernardi JM, Tricoli DM, Ercoli MFet al. A GRF-GIF chimeric protein improves the regeneration efficiency of transgenic plants. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:1274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ebinuma H, Sugita K, Matsunaga E, Yamakado M. Selection of marker-free transgenic plants using the isopentenyl transferase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2117–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kunkel T, Niu Q, Chan YS, Chua NH. Inducible isopentenyl transferase as a high-efficiency marker for plant transformation. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:916–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Maher MF, Nasti RA, Vollbrecht Met al. Plant gene editing through de novo induction of meristems. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;38:84–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pinon V, Prasad K, Grigg SPet al. Local auxin biosynthesis regulation by PLETHORA transcription factors controls phyllotaxis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1107–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Choi J, Tanaka K, Cao Yet al. Identification of a plant receptor for extracellular ATP. Science. 2014;343:290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tanaka K, Choi J, Cao Y, Stacey G. Extracellular ATP acts as a damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP) signal in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bishop PD, Makus DJ, Pearce G, Ryan CA. Proteinase inhibitor-inducing factor activity in tomato leaves resides in oligosaccharides enzymically released from cell walls. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:3536–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ikeuchi M, Iwase A, Rymen Bet al. Wounding triggers callus formation via dynamic hormonal and transcriptional changes. Plant Physiol. 2017;175:1158–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Iwase A, Harashima H, Ikeuchi Met al. WIND1 promotes shoot regeneration through transcriptional activation of ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2017;29:54–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cheng Y, Liu H, Cao Let al. Down-regulation of multiple CDK inhibitor ICK/KRP genes promotes cell proliferation, callus induction and plant regeneration in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kirch T, Simon R, Grunewald M, Werr W. The DORNROSCHEN/ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION1 gene of Arabidopsis acts in the control of meristem cell fate and lateral organ development. Plant Cell. 2003;15:694–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chen T, Dent SY. Chromatin modifiers and remodelers: regulators of cellular differentiation. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ikeuchi M, Iwase A, Rymen Bet al. PRC2 represses dedifferentiation of mature somatic cells in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants. 2015;1:15089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Iwase A, Mitsuda N, Koyama Tet al. The AP2/ERF transcription factor WIND1 controls cell dedifferentiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2011;21:508–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee K, Park O-S, Choi CY, Seo PJ. ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX4 facilitates shoot identity establishment during the plant regeneration process. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019;60:826–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Skoog F, Miller CO. Chemical regulation of growth and organ formation in plant tissues cultured in vitro. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1957;11:118–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hu W, Fagundez S, Katin-Grazzini Let al. Endogenous auxin and its manipulation influence in vitro shoot organogenesis of citrus epicotyl explants. Hortic Res. 2017;4:17071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chen L, Tong J, Xiao Let al. YUCCA-mediated auxin biogenesis is required for cell fate transition occurring during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:4273–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fan M, Xu C, Xu K, Hu Y. LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN transcription factors direct callus formation in Arabidopsis regeneration. Cell Res. 2012;22:1169–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Meng WJ, Cheng ZJ, Sang YLet al. Type-B ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORs specify the shoot stem cell niche by dual regulation of WUSCHEL. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1357–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Smigochki AC, Owens LD. Cytokinin gene fused with a strong promoter enhances shoot organogenesis and zeatin levels in transformed plant cells. Proc Nati Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5131–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Riou-Khamlichi C, Huntley R, Jacqmard A, Murray JAH. Cytokinin activation of Arabidopsis cell division through a D-type cyclin. Science. 1999;283:1541–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yanai O, Shani E, Dolezal Ket al. Arabidopsis KNOXI proteins activate cytokinin biosynthesis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1566–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Liu J, Sheng L, Xu Yet al. WOX11 and 12 are involved in the first-step cell fate transition during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2014;26:1081–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zhao Z, Andersen SU, Ljung Ket al. Hormonal control of the shoot stem-cell niche. Nature. 2010;465:1089–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kiba T, Yamada H, Sato Set al. The type-a response regulator, ARR15, acts as a negative regulator in the cytokinin-mediated signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kausch AP, Nelson-Vasilchik K, Hague Jet al. Edit at will: genotype independent plant transformation in the era of advanced genomics and genome editing. Plant Sci. 2019;281:186–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gallois J-L, Woodward C, Reddy GV, Sablowski R. Combined SHOOT MERISTEMLESS and WUSCHEL trigger ectopic organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Development. 2002;129:3207–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zuo J, Niu QW, Frugis G, Chua NH. The WUSCHEL gene promotes vegetative-to-embryonic transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;30:349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Laux T, Mayer KFX, Berger J, Jürgens G. The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development. 1996;122:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yadav RK, Perales M, Gruel Jet al. WUSCHEL protein movement mediates stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2015–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Su YH, Zhao XY, Liu YBet al. Auxin-induced WUS expression is essential for embryogenic stem cell renewal during somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;59:448–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zhang TQ, Lian H, Zhou CMet al. A two-step model for de novo activation of WUSCHEL during plant shoot regeneration. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1073–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Aida M, Ishida T, Tasaka M. Shoot apical meristem and cotyledon formation during Arabidopsis embryogenesis: interaction among the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS genes. Development. 1999;126:1563–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hardtke CS, Berleth T. The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. EMBO J. 1998;17:1405–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Krogan NT, Marcos D, Weiner AI, Berleth T. The auxin response factor MONOPTEROS controls meristem function and organogenesis in both the shoot and root through the direct regulation of PIN genes. New Phytol. 2016;212:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Harada JJ. Role of Arabidopsis LEAFY COTYLEDON genes in seed development. J Plant Physiol. 2001;158:405–9. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Horstman A, Li M, Heidmann Iet al. The BABY BOOM transcription factor activates the LEC1-ABI3-FUS3-LEC2 network to induce somatic embryogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2017;175:848–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shiota H, Satoh R, Watabe Ket al. C-ABI3, the carrot homologue of the Arabidopsis ABI3, is expressed during both zygotic and somatic embryogenesis and functions in the regulation of embryo-specific ABA-inducible genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:1184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Lueruen H, Kirik V, Herrmann P, Misera S. FUSCA3 encodes a protein with a conserved VP1/ABI3-like B3 domain which is of functional importance for the regulation of seed maturation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;15:755–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Mizukami Y, Fischer RL. Plant organ size control: AINTEGUMENTA regulates growth and cell numbers during organogenesis. Proc Nati Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:942–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Dewitte W, Riou-Khamlichi C, Scofield Set al. Altered cell cycle distribution, hyperplasia, and inhibited differentiation in Arabidopsis caused by the D-type cyclin CYCD3. Plant Cell. 2003;15:79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Elhiti M, Stasolla C. In vitro shoot organogenesis and hormone response are affected by the altered levels of Brassica napus meristem genes. Plant Sci. 2008;190:40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Khanday I, Santos-Medellin S, Sundaresan V. Rice embryogenic trigger BABY BOOM1 promotes somatic embryogenesis by upregulation of auxin biosynthesis genes. BioRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.08.24.265025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kulinska-Lukaszek K, Tobojka M, Adamiok A, Kurczynska EU. Expression of the BBM gene during somatic embryogenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Biol Plant. 2012;56:389–94. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Khanday I, Skinner D, Yang Bet al. A male-expressed rice embryogenic trigger redirected for asexual propagation through seeds. Nature. 2019;565:91–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Jia H, McCarty DR, Suzuki M. Distinct roles of LAFL network genes in promoting the embryonic seedling fate in the absence of VAL repression. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:1293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Wang Y, He S, Long Yet al. Genetic variations in ZmSAUR15 contribute to the formation of immature embryo-derived embryonic calluses in maize. Plant J. 2022;109:980–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Long JA, Moan EI, Medford JI, Barton MK. A member of the KNOTTED class of homeodomain proteins encoded by the STM gene of Arabidopsis. Nature. 1996;379:66–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Jasinski S, Piazza P, Craft Jet al. KNOX action in Arabidopsis is mediated by coordinate regulation of cytokinin and gibberellin activities. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1560–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Cole M, Chandler J, Weijers Det al. DORNROSCHEN is a direct target of the auxin response factor MONOPTEROS in the Arabidopsis embryo. Development. 2009;136:1643–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Donner TJ, Sherr I, Scarpella E. Regulation of preprocambial cell state acquisition by auxin signaling in Arabidopsis leaves. Development. 2009;136:3235–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kim JH. Biological roles and an evolutionary sketch of the GRF-GIF transcriptional complex in plants. BMB Rep. 2019;52:227–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kim JH, Tsukaya H. Regulation of plant growth and development by the GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR and GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR duo. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:6093–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Luo G, Palmgren M. GRF-GIF chimeras boost plant regeneration. Trends Plant Sci. 2021;26:201–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Niemann MCE, Weber H, Hluska Tet al. The cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase CKX1 is a membrane-bound protein requiring homooligomerization in the endoplasmic reticulum for its cellular activity. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:2024–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Wu W, Li J, Wang Qet al. Growth-regulating factor 5 (GRF5)-mediated gene regulatory network promotes leaf growth and expansion in poplar. New Phytol. 2021;230:612–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Akiyoshi DE, Klee H, Amasino RMet al. T-DNA of agrobacterium tumefaciens encodes an enzyme of cytokinin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:5994–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Barry GF, Rogers SG, Fraley RT, Brand L. Identification of a cloned cytokinin biosynthetic gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:4776–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Smigocki AC, Owens LD. Cytokinin gene fused with a strong promoter enhances shoot organogenesis and zeatin levels in transformed plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5131–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Smigocki AC, Owens LD. Cytokinin-to-auxin ratios and morphology of shoots and tissues transformed by a chimeric isopentenyl transferase gene. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:808–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Ooms G, Karp A, Roberts J. From tumour to tuber; tumour cell characteristics and chromosome numbers of crown gall-derived tetraploid potato plants (Solanum tuberosum cv. ‘Maris bard’). Theor Appl Genet. 1983;66:169–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Iwase A, Mita K, Nonaka Set al. WIND1-based acquisition of regeneration competency in Arabidopsis and rapeseed. J Plant Res. 2015;128:389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Dai X, Liu Z, Qiao Met al. ARR12 promotes de novo shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis thaliana via activation of WUSCHEL expression. J Integr Plant Biol. 2017;59:747–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Parcy F, Valon C, Kohara Aet al. The ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE3, FUSCA3, and LEAFY COTYLEDON1 loci act in concert to control multiple aspects of Arabidopsis seed development. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1265–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kwong RW, Bui AQ, Lee Het al. LEAFY COTYLEDON1-LIKE defines a class of regulators essential for embryo development. Plant Cell. 2003;15:5–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Paul P, Joshi S, Tian Ret al. The MADS-domain factor AGAMOUS-Like18 promotes somatic embryogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2021;Kiab553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Lardon R, Wijnker E, Keurentjes J, Geelen D. The genetic framework of shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis comprises master regulators and conditional fine-tuning factors. Commun Biol. 2020;3:549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Prunet N, Yang W, Das Pet al. SUPERMAN prevents class B gene expression and promotes stem cell termination in the fourth whorl of Arabidopsis thaliana flowers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:7166–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Karami O, Rahimi A, Mak Pet al. An Arabidopsis AT-hook motif nuclear protein mediates somatic embryogenesis and coinciding genome duplication. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Huang D, Kosentka PZ, Liu W. Synthetic biology approaches in regulation of targeted gene expression. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2021;63:102036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Liu W, Stewart CN Jr. Plant synthetic promoters and transcription factors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;37:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Forsyth A, Weeks T, Richael C, Duan H. Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN)-mediated targeted DNA insertion in potato plants. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Liu W, Rudis MR, Cheplick MHet al. Lipofection-mediated genome editing using DNA-free delivery of the Cas9/gRNA ribonucleoprotein into plant cells. Plant Cell Rep. 2020;39:245–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Ondzighi-Assoume CA, Willis JD, Ouma WKet al. Embryogenic cell suspensions for high-capacity genetic transformation and regeneration of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.). Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12:290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]