Abstract

Electrochemical reduction of CO2 to value-added chemicals and fuels shows great promise in contributing to reducing the energy crisis and environment problems. This progress has been slowed by a lack of stable, efficient and selective catalysts. In this paper, density functional theory (DFT) was used to study the catalytic performance of the first transition metal series anchored TM–Bβ12 monolayers as catalysts for electrochemical reduction of CO2. The results show that the TM–Bβ12 monolayer structure has excellent catalytic stability and electrocatalytic selectivity. The primary reduction product of Sc–Bβ12 is CO and the overpotential is 0.45 V. The primary reduction product of the remaining metals (Ti–Zn) is CH4, where Fe–Bβ12 has the minimum overpotential of 0.45 V. Therefore, these new catalytic materials are exciting. Furthermore, the underlying reaction mechanisms of CO2 reduction via the TM–Bβ12 monolayers have been revealed. This work will shed insights on both experimental and theoretical studies of electroreduction of CO2.

These new TM–Bβ12 monolayers will display excellent catalytic performance for electroreduction of CO2. Primary reduction product of Sc is CO (overpotential 0.45 V). Primary product Ti–Zn is CH4, and Fe–Bβ12 has 0.45 V overpotential.

1. Introduction

With the development of society and the economy, the energy crisis and the greenhouse effect have received more and more attention because of the serious impact on the environment.1 The conversion of CO2 into fuels and various chemicals would not only effectively alleviate the dependence on fossil fuels, but also potentially reduce the harm caused by the greenhouse effect.2–6 Carbon dioxide as a non-polar molecule is often considered an inert material with a unique linear structure. This determines the chemical reaction of CO2 under special conditions (such as high temperature, high pressure with a catalyst). Based on factors such as energy requirements, process speed, and cost, electrochemistry is a promising method for these reactions due to its advantages such as mild reaction conditions.7–12

Due to their high specific surface area, reduced dimensionality and exotic properties, two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets have become an ideal platform for the design of novel electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction.13–16 Borophene is a novel 2D material under active investigation with fascinating and diverse properties and potential.17 Recently, honeycomb borophene has been experimentally fabricated on an Al(111) substrate.18 This experimental work then triggered the theoretical discovery of a new 2D anti-van't Hoff/Le Bel ptAl array AlB6 which is predicted to have rare triple Dirac cone electronic structure as well as superconductivity.19 This is an example of how the properties of borophene can be enhanced and extended by alloying with other elements. This may provide new opportunities to design functional materials or catalysts.

To the best of our knowledge, the application of TM–Bβ12 monolayers as new single-atom catalysts for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction (CRR) has not been achieved. Therefore, we performed a systematic study on the catalytic performance of TM–Bβ12 (TM = Sc–Zn) monolayers for CRR using density functional theory (DFT). The results show that for the 10 materials studied, all have good stability and CRR selectivity. For Sc, the primary reduction product is CO. For the other materials, the primary product is CH4, with the overpotential as low as 0.45 V. We predict that these monolayers will be promising CRR catalysts.

2. Computational methods

Structural optimization, total energy and electronic properties (density of states, charge analysis) were calculated using spin polarized density functional theory. All of the calculations were carried out using the DMol3 module of Materials Studio 2016.20 Exchange correlation used the generalized gradient approximation (GGA).21 Exchange correlation functions used Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof (PBE), and basis sets used double numerical polarization (DNP) basis sets and all-electronic methods to process the electrons in the system.22 In order to better describe the adsorption of molecules on the catalyst surface, the van der Waals Correction (DFT-D2) was added to the calculation.23 Since electrochemical catalysis is carried out in aqueous solution, the conductor-like screening model (COSMO) was used as the solvation model for better agreement with the experiment, and the dielectric constant of water (ε) is set to 78.54.24 In order to eliminate the interactions between adjacent images, the vacuum layer thickness was selected to be 15 Å. In order to improve the accuracy of the calculations, the energy convergence criterion was 10−6 eV, and smearing of 0.005 Ha was added to accelerate the energy convergence. In structural optimization and electronic structure calculations, Monkhorst-Pack k-point grids of 5 × 5 × 1 and 12 × 12 × 1 were used respectively.

The adsorption energy is a measure of the interaction between intermediates and the TM–Bβ monolayer. Formula (1) defines the adsorption energy (for example, for CH4):

| Eads = ETM–Bβ12–CH4 − ETM–Bβ12 − ECH4 | 1 |

where ETM–Bβ12–CH4, ETM–Bβ12 and ECH4 represent the total energy of CH4 adsorbed on the TM–Bβ12 surface, the energy of the TM–Bβ12 monolayer, and the energy of a single CH4 molecule, respectively. The concept of Gibbs free energy is introduced in order to determine the optimal reaction paths of CRR. Formula (2) defines the Gibbs free energy:

| ΔG = ΔE + ΔEZPE − TΔS + ΔGpH + ΔGU | 2 |

The electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 involves electron transfer, so the energy of this reaction can be calculated by the reference standard hydrogen electrode method proposed by Nørskov and co-workers.25 In the formula ΔE is the reaction energy of each protonation step, ΔEZPE and ΔS are the change of zero point energy and entropy value, and T is the thermodynamic temperature of the reaction (298.15 K). ΔGpH is due to the effect of different pH values of the solution on the Gibbs free energy of reaction (ΔGpH = 2.303kBTpH). The pH value in acidic solution is assumed to be 0. ΔGU is due to the influence of different electrode potentials on the free energy of reaction. ΔGU can be produced by the formula

| ΔGU = − neU | 3 |

In this formula, n is the number of transfer electrons, and e is the electron charge, and U is the electrode potential. The catalytic performance of the TM–Bβ12 monolayers can be evaluated using the limit potential (UL) and the overpotential (η). The limit potential is calculated by the formula

| UL = −ΔGmax/ne | 4 |

where ΔGmax is the change of free energy of the decisive step. The overpotential is calculated by the difference between the equilibrium potential and the limit potential. The formula is

| η = Uequilibrium − UL | 5 |

The higher the overpotential, the more difficult the reaction. Therefore, a good CRR catalyst must have a small overpotential.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural features of the TM–Bβ12 monolayer

Fig. 1 shows top and side views of the TM–Bβ12 monolayers in the 3 × 3 computational supercell. In this paper, we studied the 10 metals of the first transition metal series. The results show that all 10 metal atoms protrude from the surface of the monolayer (as shown in Fig. 1b and c). This may be due to the fact that the B–B bond lengths are quite small, so that the space in the six-membered ring is limited, and so the TM atoms must protrude from the plane. It can be seen from Table 1 that the bond lengths of the metal atoms with the boron atoms (RTM–B) are in the range of 2.399 to 1.895 Å, and from Sc to Zn the overall trend is decreasing. In addition, the height of the metal atoms up from the surface of the boron monolayer (Rout) is also decreasing from 1.818 to 1.353 Å. In order to study the charge transfer in these materials, Hirshfeld charge analysis was carried out.26 From the data in Table 1, all metal atoms have a partial positive charge, while the adjacent six B atoms have a partial negative charge. This shows that the metal atoms transfer electrons to the B atoms, which causes the metal atoms to have partial ionic bonds with their neighbors. In addition, the calculation results show that except for Mn, Fe, and Co the remaining seven metals have zero spin. The maximum magnetic moment is for Mn with 3.91 μB.

Fig. 1. Optimized geometric structure of the TM–Bβ12 monolayers in the 3 × 3 computational supercell. (a) Top view, (b) and (c) side views. The pastel pink, orange and purple balls represent B, TM (TM = Sc, Cu and Zn) and TM (TM = Ti–Ni), respectively. Rout is the distance between the metal atom and the plane of the Bβ12 sheet.

Calculated Hirshfeld charge on the metal atoms (QTM), and the boron atoms (QB), Hirshfeld spin of the metal atoms (spin-TM), the height of the metal atom protruding from the surface of the monolayer (Rout), and the TM–B bond length (RTM–B) of the metal atoms with the boron atoms.

| TM–Bβ12 | Q TM/e | Spin-TM | Q B/e | R out/Å | R TM–B/Å |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sc | 0.933 | 0.000 | −0.081 | 1.748 | 2.399 |

| Ti | 0.676 | 0.000 | −0.069 | 1.818 | 2.138 |

| V | 0.485 | 0.000 | −0.048 | 1.717 | 2.022 |

| Cr | 0.465 | 0.000 | −0.059 | 1.564 | 1.949 |

| Mn | 0.138 | 3.910 | −0.013 | 1.487 | 1.917 |

| Fe | 0.047 | 2.743 | −0.002 | 1.370 | 1.897 |

| Co | 0.059 | 1.801 | −0.005 | 1.353 | 1.895 |

| Ni | 0.038 | 0.000 | −0.004 | 1.461 | 1.934 |

| Cu | 0.422 | 0.000 | −0.061 | 1.424 | 2.214 |

| Zn | 0.521 | 0.000 | −0.057 | 1.541 | 2.262 |

3.2. Stability of single TM atoms embedded in Bβ12

For the catalyst to be durable in practical applications, its structure must have excellent stability. Therefore, to evaluate the stability and viability of these monolayers as potential electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction, we calculated the binding energies of single atoms, three and four dispersed atoms, and clusters (composed of three and four metal atoms) onto the Bβ12 monolayer. We also calculated the cohesive energy of the bulk metals. For ease of discussion, we label the relevant energy values as ESAC1b, ESAC3b, ESAC4b, ECL3b, ECL4b and Ec. The detailed results are shown in Table S1.† A typical example comparing ESAC3bvs. ECL3b and ESAC4bvs. ECL4b for Fe–Bβ12 can be found in Fig. S2.†

If the absolute value of the binding energy (ESAC1b) is larger than the absolute value of the cohesive energy (Ec) of the corresponding bulk metal, this means that the metal atom is more likely to bind with the Bβ12 monolayer, thus indicating that the TM–Bβ12 monolayer has excellent stability. It can be seen from Table S1† that the absolute value of ESAC1b (except Sc and Ti) are smaller than the absolute value of Ec. Considering the binding energies of the clusters of 3 and 4 metal atoms with Bβ12 monolayer (ECL3b and ECL4b), the absolute values of ECL3b and ECL4b (except Zn) are smaller than the absolute value of ESAC3b and ESAC4b of the corresponding 3 and 4 dispersed metal atoms with Bβ12 monolayer (as shown from Fig. 2 and Table S2†), which indicates that the dispersed metal atoms have stronger binding ability to the Bβ12 monolayer than the metal clusters (except for Zn). Therefore, the metal atoms are more likely to bind to the Bβ12 monolayer. Furthermore, the binding energy for individual atoms is relatively large and ranges from 3 to 6 eV (other than Zn) so the TM–Bβ12 monolayers (other than Zn) have strong stability.

Fig. 2. E SAC3 and ESAC4b are the binding energies of embedded three and four metal atoms with the Bβ12 monolayer. ECL3b and ECL4b are the binding energies of metal clusters (comprised of three and four metal atoms) with the Bβ12 monolayer.

3.3. First hydrogenation: selectivity for CRR vs. HER

Since CO2 reduction occurs in aqueous solution, the proton–electron pair (H+ + e−) required for CRR is mainly derived from water. The metal atom directly accepts a proton–electron pair to produce H* (* + H+ + e− → H*). If the reaction continues, H2 will be desorbed from the surface of the catalyst. This is called the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). HER as a side reaction of CRR could potentially reduce the efficiency of the catalysts, so the selectivity of these new materials for CRR versus HER must be considered. The first step of the protonation of CRR is based on the path CO2 + H+ + e− → C*OOH or O*CHO to produce two intermediates, C*OOH or O*CHO. The Gibbs free energy change for the first hydrogenation step can be used to determine whether the monolayer binding with C*OOH or O*CHO (or with H*) is stable. The more negative the Gibbs free energy change, the more stable the binding. Because the metal active sites of the TM–Bβ12 monolayer surface are limited, if the monolayer binds to C*OOH or O*CHO stably, the active site will be occupied, which will make H* difficult to form. Thus, the catalyst has a good CRR selectivity. It can be seen from Fig. 3, that for the monolayers considered, all metals are below the dotted line, indicating strong CRR selectivity (see Table S2†).

Fig. 3. ΔGCOOH* and ΔGOCHO* are the Gibbs free energy change of the first protonation step in CRR and ΔGH* is for HER. Catalysts below the dotted line are CRR selective.

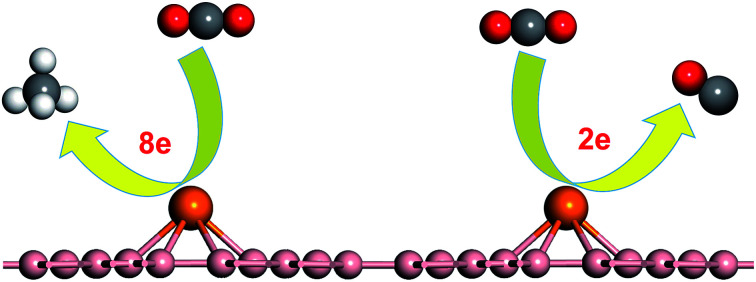

3.4. Reaction pathway analysis of CRR

The optimal reaction paths and catalytic products of these materials during CRR will now be discussed. Scheme 1 shows the most favorable reaction pathways of CRR. Fig. 4 shows the important intermediates for the whole 8e− reaction process. Each step in the protonation of CRR has two different H-adding positions (onto the C atom, or onto the O atom). Therefore CRR has many possible reaction paths. In addition, it is possible for CO2 to produce different reduction products by accepting different numbers of proton–electron pairs. The most likely reaction paths and reaction products for CRR on these materials, will be determined by the reaction Gibbs free energy change, the overpotential, the adsorption energy, and other factors.

Scheme 1. Most likely reaction pathways for the electroreduction of CO2 on TM–Bβ12.

Fig. 4. Optimized geometric structures of key reaction intermediates of CRR.

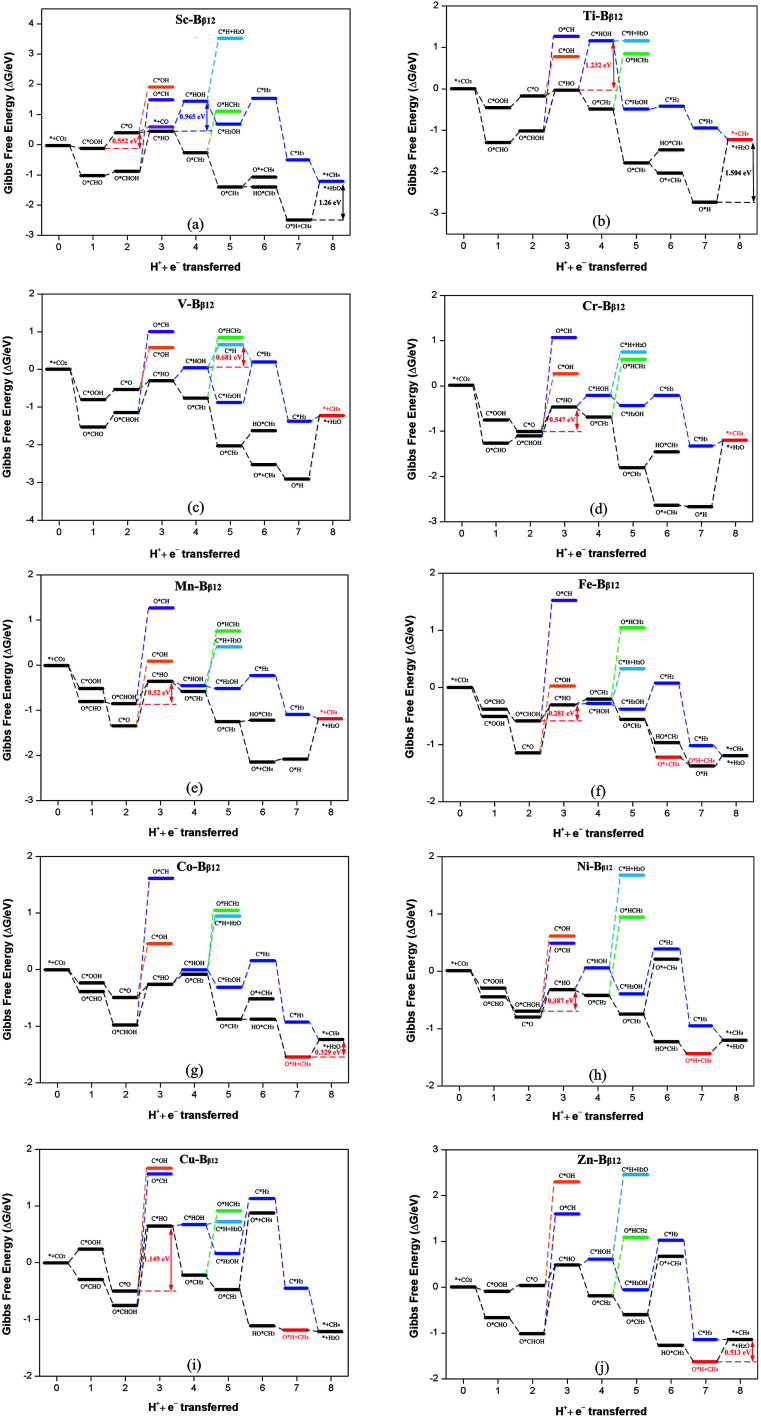

The intermediates C*OOH and O*CHO can continue to protonate and then follow the path C*OOH + H+ + e− → C*O and O*CHO + H+ + e− → O*CHOH to produce C*O and O*CHOH, respectively. If the adsorption energy of CO and HCOOH are small enough, they will become products and desorb from the surface (C*O + H2O → * + CO or O*CHOH → * + HCOOH). Conversely, if the adsorption energy of CO and HCOOH are large, it makes them difficult to desorb, but then they can continue to be reduced as reaction intermediates. Table S3† shows that the adsorption energy of Sc–Bβ12 for CO and HCOOH are −0.40 and −1.02 eV, respectively, which indicates that the adsorption energy of CO is smaller than that of HCOOH, and it is therefore easier to desorb from the surface to become a reduction product. Therefore, the reduction product of CRR for Sc is mainly CO (as shown in Fig. 5a). In addition, for Ti through Zn, the adsorption energy of CO and HCOOH are in the range of −0.92 to −2.24 eV and −0.78 to −1.35 eV, respectively, indicating that it is difficult to get 2e− products from these materials, for both CO and HCOOH. Therefore, CO and HCOOH can continue to participate in the reaction as reaction intermediates.

Fig. 5. Gibbs free energy profiles for CRR along the most favorable pathways for (a) Sc–Bβ12, (b) Ti–Bβ12, (c) V–Bβ12, (d) Cr–Bβ12, (e) Mn–Bβ12, (f) Fe–Bβ12, (g) Co–Bβ12, (h) Ni–Bβ12, (i) Cu–Bβ12 and (j) Zn–Bβ12 at zero potential. A CO2 molecule in the gas phase with a clean catalyst surface sets the free energy zero point.

CO and HCOOH can continue to be protonated to produce three intermediates: C*HO, C*HO and O*CH. Compared to C*OH and O*CH, the Gibbs free energy change for C*HO is smaller, so it is easier to form C*HO. It can be seen from Fig. 5b, c, d, g, i and j that Ti, V, Cr, Co, Cu and Zn are more likely to follow the path C*OOH → C*O → C*HO to produce C*HO. On the other hand Mn, Fe, Ni are more likely to produce C*HO according to the path O*CHO → O*CHOH → C*HO + H2O (as shown in Fig. 5e, f and h). Scheme 1 shows that C*HO can continue to hydrogenate to give the products HCHO (4e−), CH3OH (6e−) and CH4 (8e−). Table S3† shows the adsorption energies of HCHO and CH3OH for Ti through Zn are in the range of −0.73 to −2.24 eV and −0.78 to −1.35 eV, respectively. The adsorption energy of CH4 is in the range of −0.12 to −0.52 eV, which indicates that the products of these 9 catalysts from Ti to Zn are mostly CH4. As can be seen from Scheme 1, creating CH4 from the intermediate C*HO has four main pathways:

(1) C*HO → C*HOH → C*H + H2O → C*H2 → C*H3 → * + CH4

(2) C*HO → C*HOH → C*H2OH → C*H2 + H2O → C*H3 → * + CH4

(3) C*HO → O*CH2 → O*CH3 → O* + CH4 → O*H → * + H2O

(4) C*HO → O*CH2 → O*HCH2 → O*HCH3 → O*H + CH4 → * + H2O

According to the principle that the lower the energy barrier, the more likely the reaction, V will primarily follow path (1), Ti, Cr and Mn will primarily follow path (2), Fe will primarily follow path (3), and Co, Ni, Cu and Zn will primarily follow path (4).

The overpotential determines how efficient these catalysts will be in practical application. The smaller the overpotential, the smaller the applied voltage required for CRR, and the easier the reaction. Therefore, in order to have a strong catalytic effect, these new materials must have a small overpotential. Table 2 summarizes the potential determining steps, limit potential, and overpotential of these materials. The results show that the primary catalytic product of Sc is CO and its corresponding overpotential is 0.45 V. The remaining 9 materials primarily produce CH4, with overpotentials from 0.45 to 1.40 V. Only the overpotentials for Ti and Cu are greater than 1 V, while the other overpotentials are all less than 0.85 V. This is comparable to or even lower than the 1 V overpotential of CRR by polycrystalline copper that has been studied extensively in the past.27–29 The performance of the new TM–Bβ12 monolayers is comparable to that of Cu atomic chain decorated boron nanosheets.30 In addition, the overpotential of the CRR catalyst designed in this paper is comparable to or even smaller than that of other promising experimentally known catalysts in the literature. Examples include: monodisperse Au nanoparticles (η = 0.26 V),31 the modified Cu electrode from the reduction of thick Cu2O films (η = 0.50 V),32 N-doped carbon nanotubes (η = 0.54 V),33 and nanoporous Ag (η < 0.50 V).34 Therefore, we predict that the TM–Bβ12 monolayer will have excellent catalytic activity for CRR.

Calculated potential determining steps (PDS), limiting potentials (UL/V), equilibrium potential of different reduction products (Ueq/V, vs. SHE, pH = 0) and overpotentials (η/V) for the CRR.

| TM–Bβ12 | PDS | U L | U eq (product) | η |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sc–Bβ12 | C*OOH → C*O + H2O | −0.552 | −0.106 (CO) | 0.446 |

| Ti–Bβ12 | C*HO→ C*HOH | −1.232 | 0.169 (CH4) | 1.401 |

| V–Bβ12 | C*HOH → C*H + H2O | −0.681 | 0.169 (CH4) | 0.850 |

| Cr–Bβ12 | C*O → C*HO | −0.547 | 0.169 (CH4) | 0.716 |

| Mn–Bβ12 | O*CHOH → C*HO + H2O | −0.520 | 0.169 (CH4) | 0.689 |

| Fe–Bβ12 | O*CHOH → C*HO + H2O | −0.281 | 0.169 (CH4) | 0.450 |

| Co–Bβ12 | O*H → * + H2O | −0.329 | 0.169 (CH4) | 0.498 |

| Ni–Bβ12 | O*CHOH → C*HO + H2O | −0.387 | 0.169 (CH4) | 0.556 |

| Cu–Bβ12 | C*O → C*HO | −1.149 | 0.169 (CH4) | 1.318 |

| Zn–Bβ12 | O*H → * + H2O | −0.513 | 0.169 (CH4) | 0.682 |

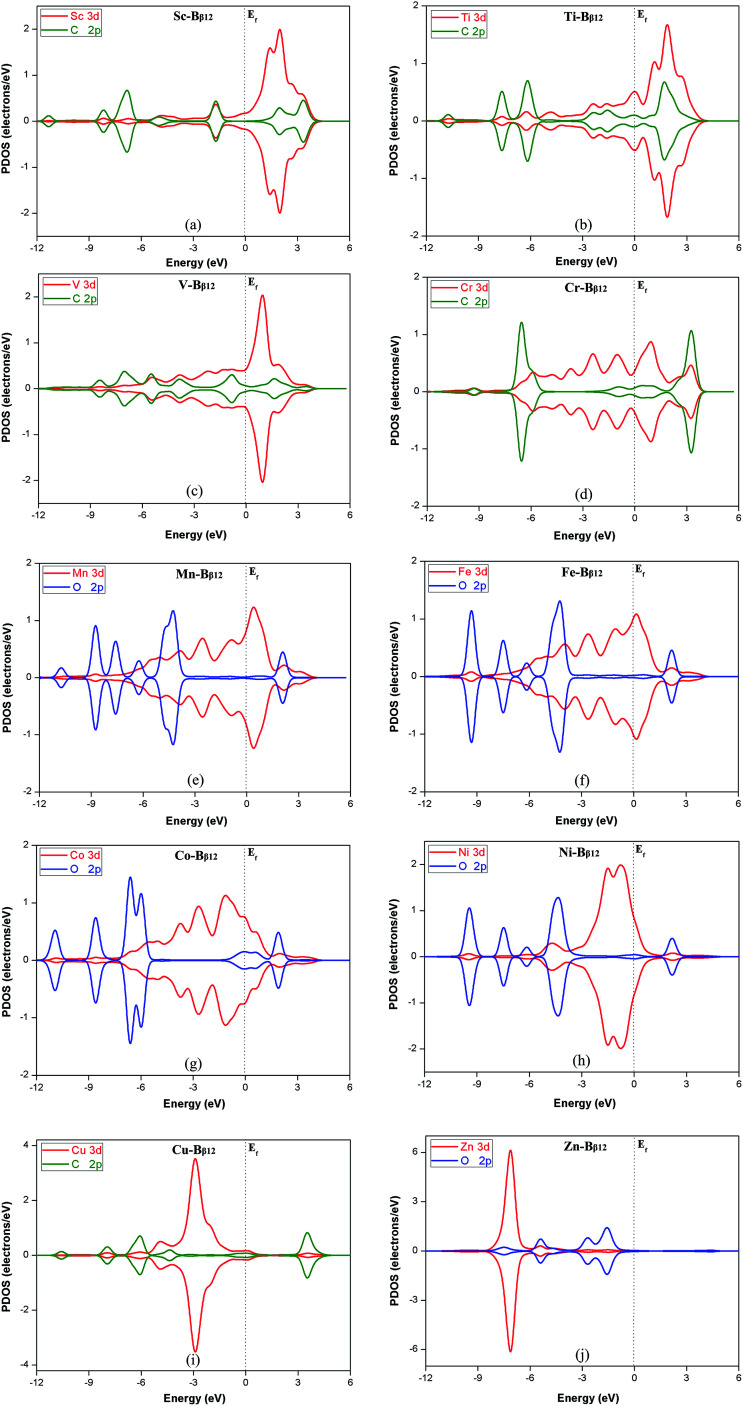

3.5. Electronic structure analysis

For these new catalysts, the interaction between the transition metal atoms and the β-type B monolayer will greatly affect the CRR catalytic performance. From the PDOS diagram of Fig. S1,† it can be seen that the 3d orbitals of the metal atoms in the monolayer overlap with the 2p orbitals of the B atoms, which indicates that there is a strong interaction between the metal atoms and the B monolayer. For the 9 monolayers with primary reduction product CH4, the 3d orbitals of Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni overlap better with the B-2p orbitals. This indicates that their interaction with the B monolayer is stronger than for the other metals. Moreover, it can be seen from Table 2 that the overpotentials are also smaller than for the other metals (except for Zn). Thus, we can conclude that the stronger the interaction of the metal atoms with the B monolayer, the lower the overpotential for catalytic CO2 reduction. In addition, it can be seen from Table 2 that the overpotentials of Fe, Co and Ni are relatively close and lower than for the other metals. Table 1 shows that Fe, Co and Ni carry much less charge than the other metals. We see that the amount of electrons transferred when the metal atom interacts with the B monolayer correlates with the catalytic ability of these materials.

In addition, the strength of the interaction between the reaction intermediates and the monolayers has a great influence on whether CRR can proceed smoothly. If the monolayer binds the intermediates too strongly, the catalyst can lose its activity and the so-called poisoning phenomenon can appear. Conversely, if the binding is too weak, the intermediate will easily fall off the surface of the catalyst, which will make the reduction reaction not likely to continue. Therefore, it is necessary to have a suitable adsorption energy for the intermediates on the catalysts. In addition, the interaction between the reaction intermediates and the TM–Bβ12 monolayers have a great influence on the magnitude of the overpotential of CRR. If the interaction is too strong, the Gibbs free energy of the protonation reaction at the potential determining step will increase, and the energy barrier of the reaction will also increase. The higher the energy barrier of the potential determining step, the bigger the overpotential of the reaction. According to the organometallic catalyst metal coordination theory, the intermediate and TM–Bβ12 mainly interact through the σ-bond and the π-bond. Fig. 6 show the PDOS diagrams of the reaction intermediates in the potential determining step of different TM–Bβ12 monolayers catalyzed CO2 reduction reactions. The 3d orbitals of the metal atoms in the TM–Bβ monolayers and the carbon or oxygen in the intermediates overlap with different degrees. For Ti, V, and Cu (Fig. 6b, c and i), the metal atom states overlap with the 2p orbitals of carbon or oxygen in the intermediates more than the other metals. This indicates that Ti, V, and Cu monolayers interact more strongly with the intermediates of the potential determining step. Table 2 also shows that their corresponding overpotentials are higher than the other metals. This can explain that why Ti, V, and Cu monolayers have relatively high energy barriers for CRR.

Fig. 6. Projected partial density of states (PDOS) of (a) C*OOH adsorbed on Sc–Bβ12, (b) C*HO on Ti–Bβ12, (c) C*HOH on V–Bβ12, (d) C*O on Cr–Bβ12, (e) O*CHOH on Mn–Bβ12, (f) O*CHOH on Fe–Bβ12, (g) O*H on Co–Bβ12, (h) O*CHOH on Ni–Bβ12, (i) C*O on Cu–Bβ12 (j) O*H on Zn–Bβ12. The dotted line denotes the Fermi level. The red, blue and green lines represent the 3d orbital of the metal atom, and the 2p orbital of the oxygen and carbon atom, respectively.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this paper used density functional theory to study the catalytic properties of TM–Bβ12 monolayers. The results show that the metal atoms can be stably combined with the β-type boron monolayer. The catalysts show excellent CRR selectivity. The primary reduction product for Sc is CO, with 0.45 V overpotential. The primary product for the other metals (Ti–Zn) is CH4 and the overpotentials are all lower than 0.90 V (except for Ti and Cu which are greater than 1.30 V). Remarkably, the overpotential for Fe is only 0.45 V. Therefore, these new TM–Bβ12 materials are predicted to be remarkable CRR catalysts. Our results also provide theoretical support for future experimental study of these materials.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.–H. L. and L.-M. Y. gratefully acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21673087 and 21873032), Startup Fund (2006013118 and 3004013105) from Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019kfyRCPY116). The authors thank the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute (MSI) at the University of Minnesota for supercomputing resources.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9ra04135d

References

- Davis S. J. Caldeira K. Matthews H. D. Future CO2 Emissions and Climate Change from Existing Energy Infrastructure. Science. 2010;329:1330–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.1188566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Wang S. Ma X. Gong J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:3703–3727. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15008A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G. Sibener S. J. Schatz G. C. Ceyer S. T. Mavrikakis M. CO2 Hydrogenation to Formic Acid on Ni(111) J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012;116:3001–3006. doi: 10.1021/jp210408x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Habisreutinger S. N. Schmidt-Mende L. Stolarczyk J. K. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 on TiO2 and Other Semiconductors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:7372–7408. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J. Jiang Y. Jiang Z. Wang X. Wang X. Zhang S. Han P. Yang C. Enzymatic conversion of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:5981–6000. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00182J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klankermayer J. Wesselbaum S. Beydoun K. Leitner W. Selective Catalytic Synthesis Using the Combination of Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen: Catalytic Chess at the Interface of Energy and Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:7296–7343. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattrell M. Gupta N. Co A. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 to hydrocarbons to store renewable electrical energy and upgrade biogas. Energy Convers. Manage. 2007;48:1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2006.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A. A. Nørskov J. K. Activity Descriptors for CO2 Electroreduction to Methane on Transition-Metal Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:251–258. doi: 10.1021/jz201461p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J. Liu Y. Hong F. Zhang J. A review of catalysts for the electroreduction of carbon dioxide to produce low-carbon fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:631–675. doi: 10.1039/C3CS60323G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Chan S. H. Sun Q. Heterogeneous catalytic conversion of CO2: a comprehensive theoretical review. Nanoscale. 2015;7:8663–8683. doi: 10.1039/C5NR00092K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back S. Yeom M. S. Jung Y. Active Sites of Au and Ag Nanoparticle Catalysts for CO2 Electroreduction to CO. ACS Catal. 2015;5:5089–5096. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b00462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D. D. Liu J. L. Qiao S. Z. Recent Advances in Inorganic Heterogeneous Electrocatalysts for Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:3423–3452. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. Ma T. Tao H. Fan Q. Han B. Fundamentals and Challenges of Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Using Two-Dimensional Materials. Chem. 2017;3:560–587. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-H. Yang L.-M. Ganz E. Efficient and Selective Electroreduction of CO2 by Single-Atom Catalyst Two-Dimensional TM–Pc Monolayers. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018;6:15494–15502. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b03945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-H. Yang L.-M. Ganz E. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 by single atom catalyst TM–TCNQ monolayers. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7:3805–3814. doi: 10.1039/C8TA08677J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-H. Yang L.-M. Ganz E. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 by two-dimensional transition metal porphyrin sheets. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7:11944–11952. doi: 10.1039/C9TA01188A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shang J. Ma Y. Gu Y. Kou L. Two dimensional boron nanosheets: synthesis, properties and applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:28964–28978. doi: 10.1039/C8CP04850A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. Kong L. Chen C. Gou J. Sheng S. Zhang W. Li H. Chen L. Cheng P. Wu K. Experimental realization of honeycomb borophene. Sci. Bull. 2018;63:282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B. Zhou Y. Yang H.-M. Liao J.-H. Yang L.-M. Yang X.-B. Ganz E. Two−Dimensional Anti−Van't Hoff/Le Bel Array AlB6 with High Stability, Unique Motif, Triple Dirac Cones, and Superconductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:3630–3640. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delley B. From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;113:7756–7764. doi: 10.1063/1.1316015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P. Burke K. Ernzerhof M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delley B. An all-electron numerical method for solving the local density functional for polyatomic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1990;92:508–517. doi: 10.1063/1.458452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;27:1787–1799. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmeisl J. Logadottir A. Nørskov J. K. Electrolysis of water on (oxidized) metal surfaces. Chem. Phys. 2005;319:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2005.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nørskov J. K. Rossmeisl J. Logadottir A. Lindqvist L. Kitchin J. R. Bligaard T. Jónsson H. Origin of the Overpotential for Oxygen Reduction at a Fuel–Cell Cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:17886–17892. doi: 10.1021/jp047349j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld F. L. Bonded-atom fragments for describing molecular charge densities. Theor. Chim. Acta. 1977;44:129–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00549096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A. A. Abild-Pedersen F. Studt F. Rossmeisl J. Nørskov J. K. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010;3:1311–1315. doi: 10.1039/C0EE00071J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl K. P. Cave E. R. Abram D. N. Jaramillo T. F. New insights into the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on metallic copper surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012;5:7050–7059. doi: 10.1039/C2EE21234J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C. Chan K. Yoo J. S. Nørskov J. K. Barriers of Electrochemical CO2 Reduction on Transition Metals. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016;20:1424–1430. doi: 10.1021/acs.oprd.6b00103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H. Li Y. Sun Q. Cu atomic chains supported on β-borophene sheets for effective CO2 electroreduction. Nanoscale. 2018;10:11064–11071. doi: 10.1039/C8NR01855C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W. L. Michalsky R. Metin O. Lv H. F. Guo S. J. Wright C. J. Sun X. L. Peterson A. A. Sun S. H. Monodisperse Au nanoparticles for selective electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16833–16836. doi: 10.1021/ja409445p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. W. Kanan M. W. CO2 Reduction at low overpotential on Cu electrodes resulting from the reduction of thick Cu2O films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7231–7234. doi: 10.1021/ja3010978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. Kang P. Ubnoske S. Brennaman M. K. Song N. House R. L. Glass J. T. Meyer T. J. Polyethylenimine-enhanced electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to formate at nitrogen-doped carbon nanomaterials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:7845–7848. doi: 10.1021/ja5031529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q. Rosen J. Zhou Y. Hutchings G. S. Kimmel Y. C. Chen J. G. Jiao F. A selective and efficient electrocatalyst for carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3242. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.