Abstract

Understanding water use characteristics of C3 and C4 crops is important for food security under climate change. Here, we aimed to clarify how stomatal dynamics and water use efficiency (WUE) differ in fluctuating environments in major C3 and C4 crops. Under high and low nitrogen conditions, we evaluated stomatal morphology and kinetics of stomatal conductance (gs) at leaf and whole-plant levels in controlled fluctuating light environments in four C3 and five C4 Poaceae species. We developed a dynamic photosynthesis model, which incorporates C3 and C4 photosynthesis models that consider stomatal dynamics, to evaluate the contribution of rapid stomatal opening and closing to photosynthesis and WUE. C4 crops showed more rapid stomatal opening and closure than C3 crops, which could be explained by smaller stomatal size and higher stomatal density in plants grown at high nitrogen conditions. Our model analysis indicated that accelerating the speed of stomatal closure in C3 crops to the level of C4 crops could enhance WUE up to 16% by reducing unnecessary water loss during low light periods, whereas accelerating stomatal opening only minimally enhanced photosynthesis. The present results suggest that accelerating the speed of stomatal closure in major C3 crops to the level of major C4 crops is a potential breeding target for the realization of water-saving agriculture.

Major C4 crops exhibit rapid stomatal opening and closure, which contribute to greater water use efficiency compared with C3 crops.

Introduction

Due to climate change and population growth, it will become increasingly difficult to secure agricultural water for crop production, which accounts for 70% of the world freshwater use (Hirabayashi et al., 2013; Carrão et al., 2016). Therefore, understanding the water use characteristics of major Poaceae crops, which provide >60% of the world food production, is essential for forecasting future water demand and for the improvement of crop water use efficiency (WUE) (Condon, 2020).

Plant water use and photosynthesis are strongly determined by transpiration and CO2 uptake through stomata. Since about 99% of water absorbed by roots are lost by transpiration, plants strictly regulate stomatal movement in response to dynamic environmental conditions and according to physiological status (Lawson and Vialet-Chabrand, 2019; Lawson and Matthews, 2020). Leaf-level stomatal responses to various environmental cues and underlying physiological and molecular mechanisms have been well investigated (Shimazaki et al., 2007), while plant- to canopy-level water use in fluctuating environments are not. This suggests that there is still potential for improving irrigation management and developing water-saving cultivars of major cereal crops as staple food sources.

Generally, C4 plants exhibit higher photosynthetic rate (A) and lower stomatal conductance (gs) relative to their high A compared with C3 herbaceous plants, which was achieved by the CO2 concentrating mechanism (Dai et al., 1993). Consequently, C4 plants show higher leaf-level WUE calculated as the ratio of maximum A (Amax) to maximum gs or maximum transpiration rate (E) when compared among C3 and C4 grasses (Osborne and Sack, 2012; Way et al., 2014). C4 plants are classified into three subtypes based on the dominant C4 acid decarboxylation enzymes (Gutierrez et al., 1974), and all the three subtypes are shown to have high leaf-level WUE (Cano et al., 2019). It is also reported that C4 and C4-like species showed higher leaf-level WUE than C3 species and C3–C4 intermediates of Flaveria species (Vogan and Sage, 2011). Furthermore, whole-plant WUE calculated as the ratio of dry mass to cumulative water use are about two-times higher in C4 plants than in C3 plants (Shantz and Piemeisel, 1927; Ghannoum et al., 2002; Igarashi et al., 2021). In these studies, leaf-level WUE as the ratio of Amax to maximum gs (or E) at the steady state or whole-plant WUE at the harvest were evaluated, which have deepened our understanding of the differences in leaf-level and whole-plant WUE and drought tolerance among C3 and C4 plants (Leakey et al., 2019). However, A and gs rarely reach steady-state maximum values since light intensity, air temperature, and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) fluctuate greatly even under open field conditions due to solar angle, wind, sun and shade flecks, and self- and mutual shading (Pearcy, 1990; Miyashita et al., 2012; Lawson and Vialet-Chabrand, 2019). Furthermore, it is also important to evaluate whole-plant water use, which reflect plant form and light-intercepting characteristics to reveal what stomatal dynamics contribute to the higher leaf-level and whole-plant WUE under field conditions from an agronomic point of view (Monsi and Saeki, 2005). Recently, several studies have investigated dynamics of stomatal responses in fluctuating light in mutant and over expression lines of Arabidopsis thaliana and rice (Oryza sativa; Yamori et al., 2020; Kimura et al., 2020) and across plant functional types (Vico et al., 2011) or cultivars (Qu et al., 2016). McAusland et al. (2016) investigated stomatal kinetics and morphology in 15 plant species including 3 upland C3 crops (wheat [Triticum aestivum], barley [Hordeum vulgare], and oat [Avena sativa]) and 2 C4 crops (sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and maize (Zea mays)), showing that Poaceae species exhibit faster stomatal responses than dicotyledonous crops. Several studies also reported that maize, sorghum, and other C4 grasses show rapid stomatal responses under light fluctuations (Bellasio et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). These findings suggest that higher WUE of C4 crops may be attributed to rapid stomatal responses, which could be an important breeding target for improving the WUE of C3 crops. However, these findings are still limited to the leaf-level responses, and no study has compared leaf-level and whole-plant stomatal dynamics among major C3 and C4 crops. Although guard cell size is regarded as one of the key determinants of stomatal kinetics (Elliott-Kingston et al., 2016), little is known about the relationship between them among major C3 and C4 crops (Taylor et al., 2012). Nitrogen (N) is another key determinant of gs since plants grown under high nitrogen (HN) availability with higher leaf nitrogen content showed higher A and gs in both C3 and C4 species (Evans, 1989; Ghannoum et al., 2011). However, studies on how leaf nitrogen content influences stomatal kinetics at leaf and whole-plant levels in C3 and C4 crops are lacking. From a viewpoint of fertilization and water management in agriculture, it is important to clarify the effect of nitrogen fertilization level on stomatal kinetics in major C3 and C4 Poaceae crops.

Heat-based sap flow techniques such as the thermal dissipation method (Granier, 1987) and the heat ratio method (Clearwater et al., 2009) have been developed to evaluate plant water use continuously under variable field conditions. However, these methods require calibration of heat pulse velocity by gravimetrically measured water consumption and have difficulties in data collection at fine time resolutions, making these methods difficult to apply for the accurate estimation of stomatal conductance in response to short-term fluctuations of light intensity, wind, air temperature, and VPD. In addition to measuring leaf-level gas exchange by the portable photosynthesis system, we aimed to address the above issues by developing a system which enables the continuous measurement of whole-plant water consumption using electronic balances with Bluetooth communication function in controlled fluctuating LED conditions. Although whole-plant water use is evaluated gravimetrically by weighing pot weights in many studies, few studies has quantified whole-plant stomatal conductance by continuous measurements of water consumption at a fine time scale to characterize stomatal kinetics (Douthe et al., 2018; Eyland et al., 2021). Furthermore, while most studies have focused on the photosynthetic induction process via stomatal opening in response to the increased light intensity (Lawson and Vialet-Chabrand, 2019), the present study particularly focuses on the stomatal closure in response to decreased light intensity and its contribution to an increase in WUE by reducing unnecessary water loss during low light period. Here, we tested a hypothesis that C4 crop species with higher drought tolerance would show rapid stomatal closure in response to low light period to minimize unnecessary water loss, which could contribute to higher WUE of C4 crops. Since photosynthesis is limited by electron transport rather than stomatal conductance during low light period (Farquhar et al., 1980), rapid stomatal closure does not decrease CO2 assimilation but should substantially reduce water consumption. To test the hypothesis, a model that incorporates the C3 and C4 photosynthesis models with stomatal dynamics was developed. Using the model, we simulated how much photosynthesis and water consumption could be affected by accelerating/decelerating stomatal opening/closure in fluctuating light environments in the C3 and C4 species. In the present study, we selected four C3 and five C4 major Poaceae crops, and they were grown under high and low nitrogen (LN) availability to evaluate leaf-level and whole-plant stomatal dynamics and stomatal morphology.

Results

Leaf-level physiological and morphological traits

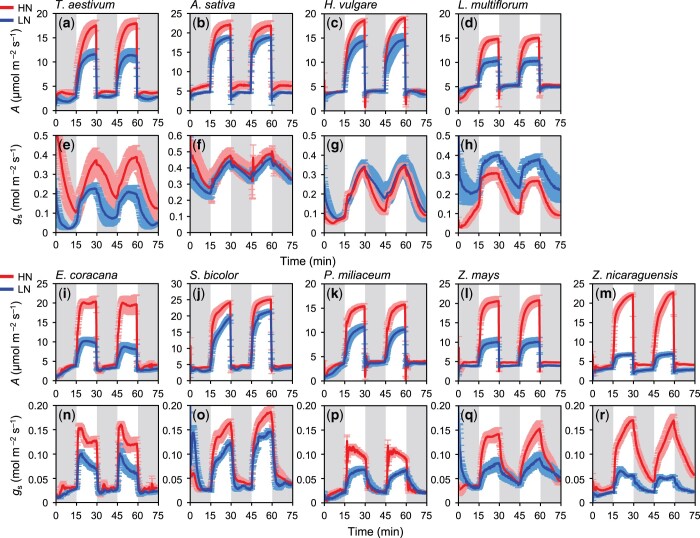

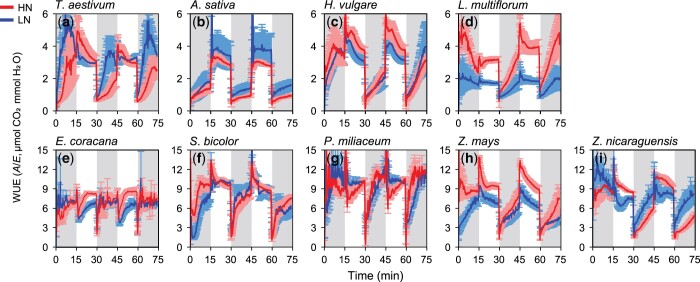

Dynamics of leaf-level photosynthetic characteristics, gs and WUE, to the fluctuating light were clearly different between the C3 and C4 Poaceae species (Figures 1 and 2). The dynamics of A was similar between the C3 and C4 species as it reached Amax during the high light period and dropped at the beginning of the low light period (Figure 1, A–D, I–M). On the other hand, the shape of gs dynamics differed markedly between the C3 and C4 species. The C3 species showed slow change in gs in response to the start of both low and high light period (Figure 1, E–H), whereas C4 species showed rapid change in gs (Figure 1, N–Q) except for Z. nicaraguensis (Figure 1R), leading to the quite different dynamics of leaf-level WUE (Figure 2). WUE was higher in the C4 species than the C3 species during the high light period. After WUE dropped in the beginning of the low light period in both C3 and C4 species, WUE gradually increased in most of the C3 species (Figure 2, A–D), whereas it rapidly increased to the values under the high light period in most of the C4 species (Figure 2, E–I). As a result, the C4 species showed significantly higher WUEHL and WUELL than the C3 species (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Dynamics of photosynthetic rate (A) and stomatal conductance (gs) at the leaf level in the controlled fluctuating light environments in four C3 and five C4 species. (A–H) four C3 and (I–R) five C4 species. Light intensity was alternately changed between low (100 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD, gray area) and high (1,000 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD, white area) at 15-min intervals for a total of 75 min. Red and blue lines represent plants grown under HN and LN conditions, respectively. Data are the mean ± se (n = 4).

Figure 2.

Dynamics of WUE in the controlled fluctuating light environments in four C3 and five C4 species. (A–D) C3 species, (E–I) C4 species. WUE was calculated as the ratio of photosynthetic rate (A) to transpiration rate (E). Light intensity was alternately changed between low (100 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD, gray area) and high (1,000 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD, white area) at 15-min intervals for a total of 75 min. Red and blue lines represent plants grown under HN and LN conditions, respectively. Data are the mean ± se (n = 4).

Table 1.

Mean WUE during the high light period (WUEHL) and low light period (WUELL) in four C3 species and five C4 species grown under high and low nitrogen conditions.

| Type | Species | N | WUEHL | WUELL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μmol CO2 mmol H2O‒1) | (μmol CO2 mmol H2O‒1) | |||

| C3 | Triticum aestivum | HN | 3.54 ± 0.27 | 1.43 ± 0.28 |

| LN | 3.22 ± 0.18 | 3.01 ± 0.52 | ||

| Avena sativa | HN | 2.98 ± 0.08 | 0.80 ± 0.04 | |

| LN | 3.89 ± 1.01 | 1.28 ± 0.26 | ||

| Hordeum vulgare | HN | 4.42 ± 0.24 | 1.69 ± 0.14 | |

| LN | 3.64 ± 0.19 | 1.81 ± 0.29 | ||

| Lolium multiflorum | HN | 3.53 ± 0.19 | 2.66 ± 0.28 | |

| LN | 1.82 ± 0.13 | 1.38 ± 0.24 | ||

| C4 | Eleusine coracana | HN | 7.72 ± 0.30 | 6.80 ± 0.43 |

| LN | 5.96 ± 0.18 | 6.65 ± 0.25 | ||

| Sorghum bicolor | HN | 9.90 ± 0.27 | 6.06 ± 0.46 | |

| LN | 9.71 ± 0.13 | 6.26 ± 0.73 | ||

| Panicum miliaceum | HN | 9.36 ± 0.29 | 9.49 ± 0.50 | |

| LN | 10.27 ± 0.22 | 8.11 ± 0.34 | ||

| Zea mays | HN | 10.16 ± 0.23 | 5.04 ± 0.78 | |

| LN | 7.38 ± 0.40 | 4.23 ± 0.69 | ||

| Zea nicaraguensis | HN | 9.70 ± 0.36 | 3.46 ± 0.16 | |

| LN | 7.99 ± 0.54 | 6.14 ± 0.63 | ||

| C3, C4 | *** | *** | ||

| Two-way ANOVA | N | ** | NS | |

| C3, C 4 × N | NS | NS |

WUEHL and WUELL were calculated as the ratio of photosynthetic ratio (A) to transpiration rate (E) during the high light period and the second and third low light period, respectively (Figure 2). Data are the mean ± se (n = 4). The effects of photosynthetic types (C3 or C4), nitrogen conditions (HN or LN), and their interaction on the characteristics were determined by two-way ANOVA (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, NS, P > 0.05).

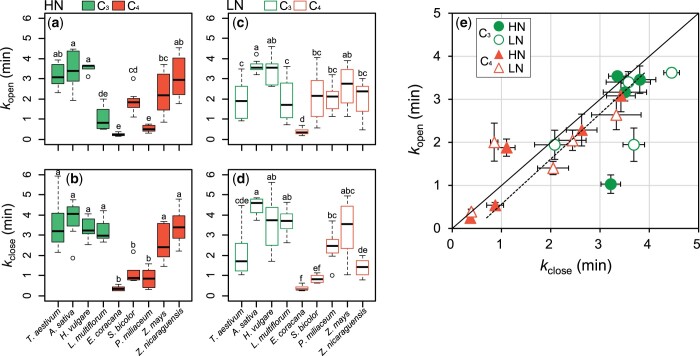

From the quantitative analysis of leaf-level stomatal dynamics, kopen and kclose were markedly different among species (Figure 3), and they were significantly different between the C3 and C4 species at each soil nitrogen condition (Supplemental Table S1). kopen and kclose were smallest in E. coracana grown under HN conditions (0.25 min and 0.36 min, respectively) and largest in A. sativa grown under LN conditions (3.62 min and 4.45 min respectively; Supplemental Table S1). kopen and kclose tended to be smaller in the C4 species under HN conditions (Figure 3, A and B), whereas they varied little among the C3 and C4 species under LN conditions except for E. coracana that showed the smallest kopen and kclose (Figure 3, A–E). Overall, kopen was significantly correlated with kclose across all the species and nitrogen conditions (Figure 3E). However, L. multiflorum showed smaller kopen and larger kclose among the C3 species, and S. bicolor showed larger kopen and smaller kclose among the C4 species. Slopen and Slclose varied little among the C3 and C4 species except for E. coracana, which showed the highest Slopen and Slclose (Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Time constants for stomatal opening (kopen) and closure (kclose) determined by the photosynthesis measurements in four C3 and five C4 species grown under HN or LN conditions. A–D, Green and orange boxes indicate C3 and C4 species, respectively. Boxplots represent the median (solid black line), first and third quartile (box limits), and maximum and minimum values (whiskers). Significant differences between the species were determined using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (P < 0.05) and are indicated by different letters. Data are the mean ± se (n = 4). E, In the relationship between kopen and kclose, solid and dotted lines represent regression line (R2 = 0.66, P < 0.01) and 1:1 line, respectively.

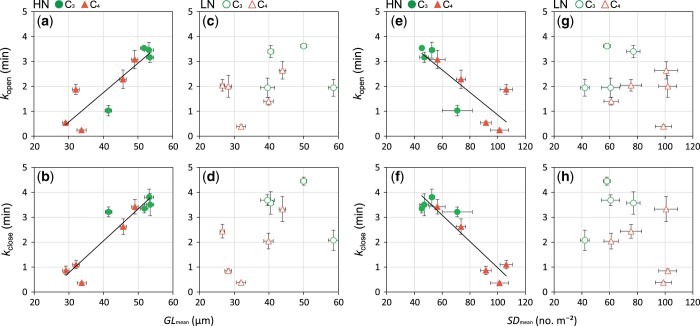

Plants grown under HN showed significantly higher Narea and Amax than those grown under LN conditions. The C3 species showed significantly higher Narea, lower stomatal density (SD), and longer guard cell than the C4 species (Supplemental Table S2). We found strong correlations between physiological and morphological characteristics of stomata only for plants grown under HN conditions (Figure 4). Across the C3 and C4 species grown under HN conditions, kopen and kclose were significantly positively correlated with guard cell length, GLmean, and significantly negatively correlated with SDmean (Figure 4, A–D). On the other hand, no significant correlations were found among these traits across the C3 and C4 species grown under LN conditions (Figure 4, C, D, G, and H). As expected, significant negative correlation was found between SDmean and GLmean across the C3 and C4 species grown under HN and LN conditions (Supplemental Figure S2, A and B).

Figure 4.

Relationship between time constants for stomatal opening (kopen) or closure (kclose) and mean GLmean or mean SDmean in four C3 and five C4 species grown under HN or LN conditions. (A, B, E, and F) HN condition and (C, D, G, and H) LN condition. Green and orange symbols indicate C3 and C4 species, respectively, and filled and open symbols indicate plants grown under HN and LN conditions, respectively. Regression lines are shown for all C3 and C4 species. Values of R2 are (A) 0.79 (P < 0.01), (B) 0.86 (P < 0.01), (E) 0.68 (P < 0.01), (F) 0.87 (P < 0.01). Data are the mean ± se (n = 4).

Whole-plant water use characteristics in fluctuating light environments

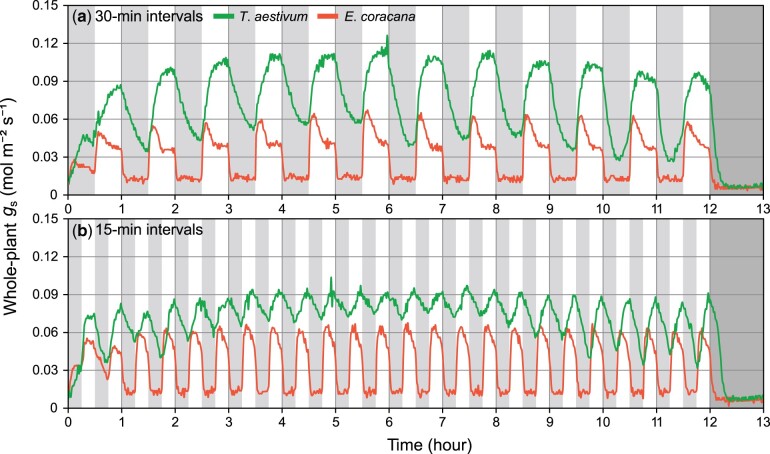

Marked differences in the dynamics of whole-plant gs were found between the C3 and C4 species and nitrogen conditions (Figure 5; Supplemental Figures S3 and S4). Triticum aestivum and E. coracana, which were shown as representatives of the C3 and C4 species, exhibited distinct diurnal patterns of gs. The dynamics of gs in E. coracana was characterized by lower whole-plant Gsmax and Gsmin, more rapid increase and decrease in gs, and consistent responses throughout the day in the fluctuating light environments at both 30-min intervals (Figure 5A) and 15-min intervals (Figure 5B). On the other hand, in T. aestivum, response of whole-plant gs to fluctuating light was slower than E. coracana, and lower Gsmax and higher Gsmin were observed in the fluctuating light environments at 15-min intervals compared with those at 30-min intervals (Figure 5B). This indicated that whole-plant gs did not reach steady state at 15-min intervals of light fluctuation. Furthermore, Gsmax and Gsmin changed diurnally in T. aestivum, whereas they were stable in E. coracana, and other C3 and C4 species showed trends similar to T. aestivum (Supplemental Figure S3) and E. coracana (Supplemental Figure S4), respectively.

Figure 5.

Dynamics of the whole-plant stomatal conductance (gs) in the controlled fluctuating light environments in T. aestivum and E. coracana. Light intensity was alternately changed between low (80 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD at 30-cm above the pot surface, gray area) and high (300 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD at 30 cm above the pot surface, white area) at 30-min intervals (A) and 15-min intervals (B) for a total of 12 h. Light was turned off from after the measurements (dark gray area). Green and orange lines represent T. aestivum (C3 species) and E. coracana (C4 species), respectively. Data are the mean of four pot plants on the balance.

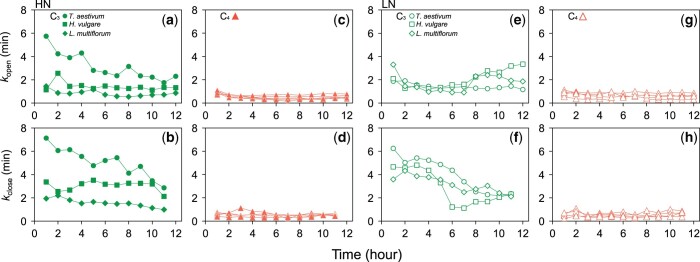

The C4 species showed significantly smaller whole-plant kopen and kclose than the C3 species (Figure 6; Supplemental Table S3). Whole-plant kopen and kclose changed diurnally in the C3 species (Figure 6, A, B, E, and F). Among the C3 species, L. multiflorum grown under HN conditions showed the smallest kopen and kclose. Whole-plant kopen and kclose were less than 1 min (Supplemental Table S3) and stable throughout the day for all the C4 species (Figure 6, C, D, G, and H).

Figure 6.

Diurnal changes in time constants for stomatal opening (kopen) or closure (kclose) calculated from the whole-plant stomatal conductance (gs) in three C3 and five C4 species grown under HN or LN conditions. (A, B, C, and D) HN condition and (E, F, G, and H) LN condition. The results obtained in fluctuating light environments at 30-min intervals are shown. Data for A. sativa grown under HN and LN and Z. nicaraguensis grown under LN were not shown since we could not fit the temporal responses of gs to the equations due to small differences in Gsmax and Gsmin (Supplemental Figures S3, C and S4I). Data are calculated from four pot plants on the balance.

Whole-plant kopen was significantly correlated with whole-plant kclose across all the species and nitrogen conditions (Supplemental Figure S5A). Whole-plant kopen and kclose were comparable in the C4 species, whereas kclose was significantly larger than kopen in the C3 species (Supplemental Table S3). Comparing the leaf-level and whole-plant stomatal characteristics obtained at moderate change (80–300 μmol m‒2 s‒1) and large change (100–1,000 μmol m‒2 s‒1) in light intensity, no significant correlations were observed between whole-plant kopen or kclose and leaf-level kopen or kclose (Supplemental Figure S5, B and C).

Simulation of the dynamic photosynthesis model

We can see how changes in light intensity and gs could affect the photosynthetic rate through changes in Aj and Cm for C3 species and Cbs for C4 species (Supplemental Figure S6). In both C3 and C4 photosynthesis models, the CO2 assimilation rate is limited by gs at high light intensity (Supplemental Figure S6, A and C), whereas it was limited by the RuBP regeneration rate at low light intensity (Supplemental Figure S6, B and D).

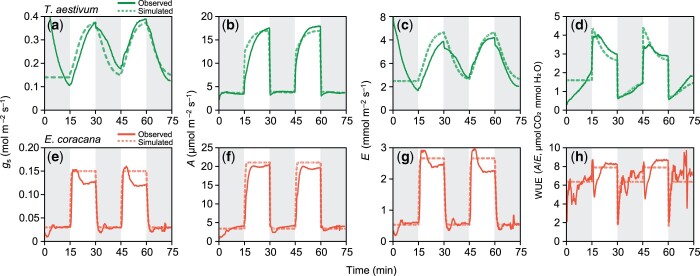

The dynamic photosynthesis model which related gs dynamics and the CO2 assimilation models could accurately predict the dynamics of A, E, and WUE calculated as A/E in the fluctuating light environments in both T. aestivum (C3 species) and E. coracana (C4 species; Figure 7). Although E. coracana might show overshoot of stomatal opening (Figure 7E), which resulted in the lower WUE (Figure 7H) at the beginning of the high light period, observed and simulated values were generally consistent. These consistencies indicate that effect of changes in kopen and kclose on A, E, and WUE can be accurately simulated in these species.

Figure 7.

Observed and simulated photosynthetic characteristics (stomatal conductance (gs), photosynthetic rate (A), transpiration rate (E), and WUE (A/E) in the controlled fluctuating light environments in T. aestivum and E. coracana grown under HN conditions. (A and E) Stomatal conductance (gs), (B, F) photosynthetic rate (A), (C, G) transpiration rate (E), and (D and H) WUE (A/E) are shown. Solid and broken lines represent observed and simulated values, respectively.

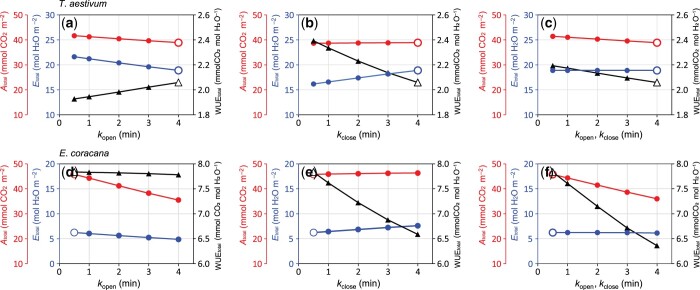

Based on the present results (Figure 3E) and previous studies (Vico et al., 2011; Israel et al., 2021) showing that kopen and kclose are not necessarily consistent with each other, we simulated the effect of both independent and simultaneous changes in kopen and kclose on A, E, and WUE. In T. aestivum with intrinsic large kopen and kclose, by decreasing kopen, i.e. accelerating stomatal opening, Atotal and Etotal increased by 7.1% and 14.5%, respectively, resulting in 6.4% decrease in WUEtotal (Figure 8A). On the other hand, decreasing kclose, i.e. accelerating stomatal closure, little affected Atotal (0.6% decrease) but decreased Etotal by 14.5%, resulting in 16.2% increase in WUEtotal (Figure 8B). This is because accelerating stomatal opening (Supplemental Figure S7A) only slightly increased A (Supplemental Figure S7B) but more substantially increased E (Supplemental Figure S7C), resulting in decreased WUE during the high light period (Supplemental Figure S7D). Meanwhile, accelerating stomatal closure (Supplemental Figure S7E) little increased A (Supplemental Figure S7F) but decreased E and increased WUE during the low light period (Supplemental Figure S7, G and H). When kopen and kclose were decreased simultaneously, Atotal increased by 6.5%, whereas Etotal did not change, resulting in only 6.5% increase in WUEtotal (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Effects of changes in time constants for stomatal opening (kopen) and closure (kclose) on total photosynthesis (Atotal), total transpiration (Etotal), and total WUEtotal during the 75 min fluctuating light period. In T. aestivum, kclose was kept constant at 4 min and kopen was varied from 4 to 0.5 (A), or kopen was kept constant at 4 min and kclose was varied from 4 to 0.5 (B). In E. coracana, kclose was kept constant at 0.5 min and kopen was varied from 0.5 to 4 (D), or kopen was kept constant at 0.5 min and kclose was varied from 0.5 to 4 (E). kopen and kclose were simultaneously varied from 0.5 to 4 and 4 to 0.5 in T. aestivum (C) and E. coracana (F), respectively. For each combination of kopen and kclose, Atotal, Etotal and WUEtotal were simulated by the dynamic photosynthesis model. Open and filled symbols represent the initial and simulated values, respectively.

In the case of E. coracana with intrinsic small kopen and kclose, increasing kopen, i.e. decelerating stomatal opening, largely decreased Atotal (22.5% decrease) and Etotal (21.8%), resulting in slight decrease in WUEtotal (0.8% decrease) (Figure 8D). Increasing kopen, i.e. decelerating stomatal closure, affected Atotal little but increased Etotal by 22%, resulting in 17% decrease in WUEtotal (Figure 8E). This is because decelerating stomatal opening (Supplemental Figure S7I), decreased A and E (Supplemental Figure S7, J and K) but affected WUE little during the high light period (Supplemental Figure S7l). Meanwhile, decelerating stomatal closure (Supplemental Figure S7M) affected A little (Supplemental Figure S7N) but increased E and decreased WUE during the low light period (Supplemental Figure S7, O and P). When kopen and kclose were increased simultaneously, Etotal little affected, whereas Atotal decreased by 21.3%, resulting in only 20% decrease in WUEtotal (Figure 8E).

Although there were no significant correlations between WUEHL and kopen (Supplemental Figure S8, A and B), there was significant negative correlation between WUELL and kclose among the C3 and C4 species grown under HN conditions consistent with the prediction (Supplemental Figure S8C).

Discussion

Rapid stomatal closure contributes to higher WUE in major C4 crops

In the present study, we found that the C4 crops exhibited substantially more rapid stomatal opening and closure than the C3 crops in the fluctuating light environments. Such rapid responses could be partly explained by the differences in stomatal morphology and density observed across all the species. The model simulation suggests that greater CO2 assimilation and higher WUE of the C4 species over the growth period are achieved by rapid stomatal opening and closure, respectively. These results further suggest that rapid stomatal closure could improve WUE of the C3 species, which may be a potential target for genetic engineering of C3 Poaceae crops.

Stomatal morphology and plant nutrient status influenced stomatal kinetics

McAusland et al. (2016) reported marked differences in kopen and kclose among 13 important crops including the crops used in the present study. In that study, it was shown that dicotyledonous crops with elliptical-shaped guard cells showed larger kopen (6.9–23.4 min), whereas Poaceae crops showed smaller kopen (0.9–4.4 min) and kclose (0.9–4.1 min), and rapid stomatal response was attributed to the dumbbell-shaped guard cells. Our results further revealed that the C4 species showed more rapid stomatal opening and closure at the leaf level even among Poaceae family with dumbbell-shaped guard cells (Figure 1), as indicated by the significantly smaller leaf-level kopen and kclose (Supplemental Table S1). Consistent with previous reports showing positive correlations between kopen and kclose among various banana varieties (Eyland et al., 2021) and among a wide range of plant species from graminoid to woody gymnosperm (Vico et al., 2011), the present study found kopen and kclose were closely related in Poaceae species (Figure 3E), suggesting the presence of common factors determining the potential of stomatal opening and closure regardless of plant functional types.

Morphological analysis suggests that factors affecting kopen and kclose are GL or SD, which is supported by the strong positive relationship between GLmean, kopen, and kclose across the C3 and C4 species grown under HN conditions (Figure 4, A, B, E, and F; Supplemental Table S2). It seems reasonable that smaller guard cells showed rapid stomatal response due to greater surface area to volume ratio and less requirements of solutes, which could cause faster expansion and contraction of guard cells by faster water influx and efflux, respectively (Drake et al., 2013; Elliott-Kingston et al., 2016). On the other hand, Zhang et al. (2019) found negative correlation between kopen and stomatal size among sixteen Oryza genotypes, indicating that the present finding may be applicable to upland crops but not to lowland crops with unlimited access to water. Recently, it is reported that the genetic variation in OsNHX1, Na+/H+ tonoplastic antiporter, is strongly associated with the time required for stomatal closure in O. sativa especially under drought stress (Qu et al., 2020), indicating the importance of considering genetic variation in stomatal physiology. Another important finding was that no significant relationship was found between kopen, kclose, and stomatal morphology under LN conditions (Figure 4, C, D, G, and H). Although no significant effect of nitrogen conditions on stomatal morphology was statistically confirmed (Supplemental Table S2), it is likely that guard cell metabolism was modulated by the changes in ion, protein, and starch content under LN conditions (Lawson and Matthews, 2020). Recent studies have also shown that subsidiary cells facilitated guard cell functions through the translocation of H+-ATPase, by serving as ion source and sink and providing mechanical strength (Higaki et al., 2014; Raissig et al., 2017; Gray et al., 2020). In these regards, single-cell metabolomics and ultrastructural observations in guard cells and subsidiary cells will uncover the factors determining stomatal kinetics as affected by soil nitrogen conditions, which could further lead to the proposal of crop-specific fertilization and water-saving managements. Interestingly, Z. mays and its wild relative Z. nicaraguensis with longer GLmean showed slower stomatal responses among the C4 species. Although these two species are diploid (Trtikova et al., 2017), it is reported that ploidy level correlates with stomatal size (Beaulieu et al., 2008; Lundgren et al., 2019). To understand the stomatal diversity among C3 and C4 Poaceae crops, it is essential to consider the process of domestication from phylogenetic and ecophysiological perspectives.

We demonstrated that the observed rapid stomatal opening and closure could contribute to the higher WUE in the C4 Poaceae crops during light transitions (Figure 2 and Table 1). Lawson and Vialet-Chabrand (2019) also theoretically evaluated potential water loss due to slower stomatal closure during shade fleck, indicating the importance of rapid stomatal closure for the improvement of WUE (Lawson and Blatt, 2014). Taken together with the previous studies, the present results suggest that leaf-level rapid stomatal closure of the C4 crops is a potential target for the improvement of C3 crop drought tolerance.

C4 species exhibited rapid stomatal responses even at the whole-plant level

We have established the system to evaluate whole-plant gs which reflects species-specific leaf arrangement and light use efficiency (Supplemental Figure S9), which also enables to evaluate diurnal patterns of water use. The system revealed that the C4 species exhibit more rapid stomatal opening and closure than the C3 species at the whole-plant level (Figure 5; Supplemental Figures S4 and S5). It is notable that Z. mays and Z. nicaraguensis showed comparable whole-plant kopen and kclose with other C4 species (Figure 6; Supplemental Table S3) despite larger leaf-level kopen and kclose (Supplemental Figure S5, B and C), suggesting that these species could respond rapidly to moderate changes in light intensity (300 μmol m‒2 s‒1) which are more frequently observed in the field environments (Miyashita et al., 2012). Meanwhile, all the C3 species showed slower stomatal responses even at the whole-plant level (Supplemental Figure S5, B and C), suggesting that the C3 species would exhibit slower stomatal response even in the field environments. Taken together, kopen and kclose could be dependent on the magnitude of light intensity change and guard cell size, which determine the amount of substances required for stomatal opening and closure, in major Poaceae crops.

Interestingly, some C3 species showed diurnal changes in whole-plant kopen and kclose (Figure 6), suggesting that diurnal changes in potassium ion and sucrose contents affected stomatal responses in those C3 species (Talbott and Zeiger, 1998; Daloso et al., 2016). We have previously argued that sugar accumulation could cause photosynthetic downregulation through a deceleration of stomatal opening and decreased maximum gs (Sugiura et al., 2019, 2020). Therefore, it is likely that stable stomatal responses in the C4 species could be attributed to lower accumulation of sugars and starch, which was achieved by higher sucrose export rate in C4 plants compared with C3 plants (Gallaher et al., 1975; Grodzinski et al., 1998).

A major limitation of the present system is that it cannot be applied to field-grown crops. It is essential to develop a new technique to understand stand-level water use characteristics and to solve the above issues in the field.

Contribution of rapid stomatal responses predicted by the dynamic photosynthesis model

Although the structure of the present model is quite simple, with a constant relationship between gsc and gmc, it successfully simulated the changes in gs, A, and WUE in the controlled fluctuating light environments (Figure 7). This demonstrates the reliability of the model structure (Supplemental Figure S6) and validity of the parameter values used for both T. aestivum and E. coracana (Table 2). Therefore, we can assume that the model can predict dynamics of gs, A, and WUE in plants with altered kopen and kclose with a certain accuracy (Supplemental Figure S7). In accordance with previous studies (Vico et al., 2011; Israel et al., 2021), kopen and kclose are not necessarily consistent with each other (Figure 3E), and kopen and kclose are not determined by stomatal morphology under LN conditions (Figure 4). These findings imply that different mechanisms could be involved in the regulation of stomatal opening and closure and motivated us to evaluate the effect of independent changes in kopen and kclose on A, E, and WUE. Israel et al. (2021) indicated a possible involvement of rate of potassium influx to guard cells with stomatal opening. Further investigation is required to uncover what physiological mechanisms are involved in stomatal closure.

Table 2.

Parameter values used for the C3 and C4 photosynthesis models

| Parameter | Unit | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| G smax | mol m‒2 s‒1 | 0.38 | 0.16 |

| r open | mol m‒2 s‒1 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| k open | min | 3.2 | 0.25 |

| G smin | mol m‒2 s‒1 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| r close | mol m‒2 s‒1 | 0.38 | 0.16 |

| k close | min | 3.5 | 0.36 |

| V cmax | μmol m‒2 s‒1 | 78.45 | 40 |

| Γ* | μmol mol‒1 | 37.74 | 10 |

| K c | μmol mol‒1 | 488 | 650 |

| K o | μmol mol‒1 | 343 | 450 |

| C a | μmol mol‒1 | 400 | 400 |

| O | mmol mol‒1 | 200 | 200 |

| J max | μmol m‒2 s‒1 | 145.10 | 120 |

| R d | μmol m‒2 s‒1 | 1.35 | 1 |

| φ r | – | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| θ r | – | 0.95 | 0.8 |

| V pmax | μmol m‒2 s‒1 | – | 120 |

| V pr | μmol m‒2 s‒1 | – | 80 |

| K p | μmol mol‒1 | – | 80 |

| g bs | mol m‒2 s‒1 | – | 0.003 |

For C3 photosynthesis model, Vcmax, Jmax, and Rd were obtained from the measurement of CO2 response curves of T. aestivum in the present study. As for the other parameters such as Γ*, Kc, and Ko, values of T. aestivum obtained in previous study were used (Silva-Pérez et al., 2017). For C4 photosynthesis model, other than stomatal kinetics of E. coracana, typical parameter values were used following previous studies (von Caemmerer, 2000; Vico and Porporato, 2008; Osborne and Sack, 2012).

The model simulation indicates that acceleration of stomatal opening would cause a large increase in water loss with little increase in CO2 assimilation, resulting in a large decrease in WUE in the C3 species T. aestivum with intrinsically large kopen (Figure 8A). This suggests that further acceleration of stomatal opening would be less beneficial for C3 Poaceae crops considering that all the C3 Poaceae crops showed kopen of <5 min, which are already much faster than other dicotyledonous crops. The importance of rapid stomatal opening for the improvement of photosynthetic induction is often discussed using dark-acclimated leaves with possibly large kopen. However, since light intensity gradually increases from dawn under field conditions, it would be appropriate to use low or high light-acclimated leaves to discuss the stomatal limitation of photosynthesis under field conditions.

Our simulation clearly indicated that rapid stomatal closure would reduce unnecessary water loss and improve WUE without decreasing Atotal in C3 species even within the range observed among the focal species (Figure 8B), but the advantage would be partially lost by the simultaneous acceleration of stomatal opening (Figure 8C). This idea is supported by the observation that T. aestivum grown under LN conditions with smaller kclose showed higher WUE compared with T. aestivum grown under HN conditions during the low light period (Figure 2A). The observed negative correlation between WUELL and kclose among the C3 and C4 species also support this idea (Supplemental Figure S8C). It is also reported that cultivars with rapid stomatal closure show higher WUE in O. sativa (Qu et al., 2016, 2020), Beta vulgaris (Barratt et al., 2021), and Musa spp (Eyland et al., 2021). Considering that agricultural water accounts for 70% of the world freshwater use (Rosegrant et al., 2009), the predicted 14.5% reduction in Etotal could make a substantial contribution to reducing agricultural water use for major upland crops such as wheat, barley, and maize. Although the evaluation of kopen and kclose is laborious as shown in the present study, measurement of SD and GL may facilitate efficient selection of varieties with high WUE. Despite showing similar GL and SD to C3 and C4 Poaceae species, C3 dicotyledonous crops with elliptical-shaped guard cells are reported to exhibit quite slow stomatal closure compared with the Poaceae species (McAusland et al., 2016). A recent study demonstrated that guard cell-specific expression of K+ channel dramatically accelerated both stomatal opening and closure in Arabidopsis, resulting in the improved WUE and growth (Papanatsiou et al., 2019). These suggest that there is much room for improving WUE by accelerating stomatal closure in those C3 dicots, which could further contribute to improving plant productivity under drought conditions. Although our model could predict A and gs with fewer parameters compared with previous dynamic photosynthesis models, incorporating metabolomic (Wang et al., 2021) and temperature-dependent biochemical models (Hikosaka et al., 2006; Yamori et al., 2012; Scafaro et al., 2011) will further clarify limiting processes of photosynthesis in fluctuating environments.

Why do C4 species show a rapid stomatal response?

The simulation results demonstrated the hypothesis that higher WUE was attributed not only to higher A and lower gs but also to rapid stomatal opening and closure minimizing unnecessary water loss in the C4 Poaceae crops (Figure 8, D–F). There is no doubt that these rapid stomatal responses enable C4 plants to adapt to drought conditions along with the CO2 concentrating mechanism. By comparing stomatal characteristics among C4 plants along precipitation and temperature gradients, it is possible to test the hypothesis that C4 species growing in more arid region would exhibit more rapid stomatal closure. In this context, it is also hypothesized that NAD-malic enzyme (NAD-ME) C4 species would show the most rapid stomatal response and highest drought tolerance among three major C4 subtypes (NAD-ME, NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME), and PEP carboxykinase (PCK)) since the abundance of NAD-ME C4 species increases with the decrease in annual precipitation (Henderson et al., 1994; Schulze et al., 1996). This hypothesis deserves to be tested, since the sole NAD-ME type C4 crop, E. coracana with higher drought tolerance (Talwar et al., 2020) showed the smallest kopen and kclose regardless of nitrogen conditions in the present study. Another important issue is whether C4 dicots exhibit rapid stomatal opening and closure like the C4 Poaceae species. Although C4 dicots such as Flaveria and Amaranthus with elliptical-shaped guard cells are known to exhibit higher leaf-level WUE at the saturating light intensity (Vogan and Sage, 2011; Tsutsumi et al., 2017), the above hypothesis has not been tested yet. The present simple dynamic photosynthesis model that can accurately evaluate CO2 assimilation, water consumption, and WUE will be useful to address which parameters are optimized thorough the stomatal behavior depending on drought, soil nutrients, and atmospheric CO2 concentration in C4 plants. For this purpose, the accuracy of the model predictions should be tested by simulating natural light fluctuation throughout day period in the gas exchange system and comparing predicted and observed A, gs, and WUE.

Conclusions

In the present study, we have quantified stomatal kinetics in four C3 and five C4 Poaceae species in controlled fluctuating light environments. We have developed a system enabling the continuous measurement of whole-plant water use throughout a day. The major C4 crops exhibited more rapid stomatal opening and closure than the C3 crops at the leaf and the whole-plant levels, which contributed to higher WUE of the C4 crops. In particular, rapid stomatal closure enhanced WUE by reducing unnecessary water loss during low light period. Morphological analysis indicated that smaller GL and higher SD could be attributed to the faster stomatal kinetics for plants grown at HN conditions. These results are supported by the sensitivity analysis by our dynamic photosynthesis model that incorporates the C3 and C4 photosynthesis models with stomatal dynamics. The present results indicate that acceleration of stomatal closure of major C3 crops to the level of major C4 crops is a potential breeding target for the realization of water-saving agriculture.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

We selected a total of nine C3 and C4 species, all belonging to the Poaceae family and regarded as major cereal crops in the world except for Zea nicaraguensis. For C3 species, we used wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. Norin 61), oat (Avena sativa cv. Tachiibuki), barley (Hordeum vulgare cv. Shunrai), and Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum cv. Waseaoba). For C4 species, we used finger millet (Eleusine coracana cv. Yukijirushi-kei), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor cv. Tsuchitaro), millet (Panicum miliaceum), maize (Zea mays cv. Honey bantam), and its wild relative Zea nicaraguensis (CIMMYT 13451).

For each species, four plants were grown in a growth room at 27°C, 40% relative humidity, and a 12/12-h photoperiod. Light was provided by white light LED source (LD93-D, GOODGOODs, Osaka, Japan), which provide a photosynthetically active photon flux density (PPFD) of 250, 300, 400 μmol m−2 s−1 at 0 cm, 30 cm, and 60 cm above the pot surface, respectively.

Seeds were sown and germinated in 500-mL plastic pots filled with peat-based compost (Natural Applied Sciences, Gifu, Japan). Plants were grown with or without nitrogen fertilizer. For plants grown under HN condition, 0.4 g of a slow-released nitrogen fertilizer containing 42% nitrogen (LP40, JCAM Agri, Tokyo, Japan), and 0.8 g of an inorganic fertilizer containing 20% of K2O and P2O5 (PK40, Onoda chemical, Tokyo, Japan) were mixed with the soil, and 50 mL of 1/500 strength nutrient solution (HYPONeX, N/P/K, 6:10:5, Hyponex Japan, Osaka, Japan) was added every 2 or 3 d. For plants grown without nitrogen fertilizer (LN), only 0.8 g of the inorganic fertilizer was mixed with the soil. Pots were placed in the same container for each species and nitrogen condition, and they were watered regularly.

Continuous measurement of whole-plant water use in fluctuating light environments

Plants were grown for different period since the growth rate was different among species dependent on seed size and nitrogen conditions. For C3 species under HN conditions, T. aestivum, A. sativa, H. vulgare, and L. multiflorum were grown for 45, 35, 45, and 45 d, respectively. For C4 species under HN conditions, E. coracana, S. bicolor, P. miliaceum, Z. mays, and Z. nicaraguensis were grown for 45, 40, 40, 40, and 50 d, respectively. For C3 species under LN conditions, T. aestivum, A. sativa, H. vulgare, and L. multiflorum were grown for 45, 35, 50, and 60 d, respectively. For C4 species under LN conditions, E. coracana, S. bicolor, P. miliaceum, Z. mays, and Z. nicaraguensis were grown for 45, 45, 55, 50, and 65 d, respectively.

We have developed a system to measure whole-plant water use continuously (Supplemental Figure S9). On two consecutive days, whole-plant water consumption was evaluated in controlled fluctuating light environments in the growth room, where light intensity was alternately changed between low (30% of maximum light intensity, 80 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD at 30 cm above the pot surface) and high (300 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD at 30 cm above the pot surface) at 30-min intervals on the first day and 15-min intervals on the second day. For each species, the soil surface was covered with a plastic sheet to prevent soil evaporation, and four pots were placed on a Bluetooth communication electronic balance with the minimum unit of 0.01 g (RJ-3200, Shinko Denshi, Tokyo, Japan) at the beginning of the light period. The balance was connected to a recording device (ZenPad 8.0, ASUS corporation, Taiwan) with an automatic logging application (Weight Data Logger, Digital Workshop Kinos, Tokyo, Japan), which were developed for the present study, and water consumption rate of the four pot plants (WC4, g s−1) was recorded at 1-min intervals. During the pot weight measurement, PPFD (S-LIA-M003, Onset Computer Corporation, Bourne, MA, USA), air temperature (Ta, °C), and relative humidity (RH, %; S-THB-M002, Onset Computer Corporation) were also measured at 1-min intervals and recorded on a data logger (HOBO Micro Station, Onset Computer Corporation).

After leaf area measurement on the third day (see below), whole-plant transpiration rate (E, mol m−2 s−1) and gs (mol m−2 s−1) were calculated from leaf area (LA4, m2) and WC4 as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where 18 is the molecular weight of water, and VPD is further calculated from Ta and RH assuming leaf temperature (TL, °C) is equal to Ta as follows:

| (3) |

We checked the validity of the assumption that TL was almost equal to Ta by direct measurements of Ta and TL, showing that the difference between Ta and TL were less than 2°C and 1°C in T. aestivum and E. coracana, respectively (Supplemental Figure S10). Briefly, T type thermocouples were attached to the abaxial side of the youngest fully expanded leaves, and TL was recorded at 1-min intervals and recorded on a data logger (Ondotori TR-55i, T&D, Nagano, Japan) at 30-min intervals of light fluctuation.

In our system, whole-plant E changed with time in species-specific manners even under steady light intensity (see “Results”), suggesting that leaves were coupled to the atmosphere if not fully (McNaughton and Jarvis 1991). Therefore, we concluded that our simplified calculation was effective to capture the species-specific patterns in the whole-plant gs in responses to the changing light intensity.

Leaf gas exchange measurement in fluctuating light environments

On the third day after the measurements of whole-plant gs, the youngest fully expanded leaves were used for photosynthesis measurements using a portable gas exchange system (LI-6800, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). The measurement started just after plants were transferred to a measurement room. The leaf chamber was maintained at 400 μmol mol−1 CO2 concentration (Ca), a leaf temperature of 25°C, and RH of 50%. To evaluate potential A and gs in controlled fluctuating light environments (McAusland et al., 2016), light intensity was alternately changed between low (100 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD) and high (1,000 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD) at 15-min intervals for a total of 75 min, and A and gs were recorded every 10 s. WUE was calculated as the ratio of A to E, and mean WUE during the high light period (WUEHL) and the second and third low light periods (WUELL) were obtained. Maximum A during the measurements was defined as Amax.

Measurements of SD and GL

After the photosynthesis measurements, nail vanish peels were taken from adaxial and abaxial sides of the same leaves. Images were obtained by light microscopy (BX41, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). SD and GL were determined from three fields of view (1.85 or 0.29 mm2 in field area) on adaxial and abaxial surfaces using ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012). Mean SD (SDmean) and GLmean were calculated as the mean values of SD and GL on adaxial and abaxial sides of the leaves, respectively.

Leaf area measurement and CN analysis

For each plant, all green leaf blades were dissected and placed between a transparent acrylic plate and a white acrylic plate. Photos were taken using smartphone camera application with skew correction function (Office Lens, Microsoft Corp, Redmond, USA), and green leaf area was determined using the ImageJ. After leaf area measurements, each plant was divided into the leaf used for photosynthesis measurement, rest of the leaves, leaf sheath, and roots. They were oven-dried for >48 h at 80°C and weighed to determine dry mass. Leaves used for photosynthesis measurement were finely ground using a mill (TissueLyser II, Retsch, Haan, Germany), and leaf nitrogen content per mass (Nmass, g N g−1) was determined with a CN analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar, Germany). Leaf mass per area (LMA, g m−2) was determined from leaf area and leaf dry mass, and leaf nitrogen content per area (Narea, g N m−2) was calculated as a product of Nmass and LMA.

Analysis of leaf-level and whole-plant stomatal dynamics

Whole-plant and leaf-level stomatal characteristics were characterized by a dynamic sigmoidal model (Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2013). To obtain time constants for stomatal opening and closure, the temporal responses of gs to increased or decreased PPFD were fitted to the following equations, respectively:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where ropen and rclose are initial values of gs before the change in PPFD, Gsmax and Gsmin are steady-state maximum or minimum gs, and kopen and kclose are time constants indicating rapidity of stomatal opening or closure. We did not use initial time lags for stomatal opening or closure in Equation (4) or (5) since the plants used in the present study showed almost no time lag (Figure 1).

Maximum rate of gs opening to an increase in PPFD (Slopen, mmol m‒2 s‒2) and that to a decrease in PPFD (Slclose, ‒mmol m‒2 s‒2) were calculated as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

Stomatal characteristics at the whole-plant level were determined for each light cycle from the temporal response of whole-plant gs obtained at 30-min intervals of light fluctuation. Meanwhile, they were not determined at 15-min intervals of light fluctuation since gs did not reach steady-state in most of C3 crops throughout a day. Leaf-level stomatal characteristics were also determined for the first and second light cycles and averaged for each plant.

Dynamic photosynthesis model in controlled fluctuating light environments

Dynamic photosynthesis model was developed by incorporating the model describing dynamics of gs (Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2013) with CO2 assimilation models for C3 photosynthesis (Farquhar et al., 1980) and C4 photosynthesis (von Caemmerer, 2000). Using the model, we simulated the effect of changes in kopen and kclose on A, E, and WUE in the C3 and C4 species. Model description is based on Osborne and Sack (2012), and A is determined for a given PPFD and gs in both C3 and C4 species.

For C3 species, A is expressed as the minimum of either the Rubisco-limited rate of photosynthesis (Ac) or the RuBP regeneration-limited rate of photosynthesis (Aj):

| (8) |

where Rd is the mitochondrial respiration rate. Ac is expressed as:

| (9) |

where Vcmax is the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation, Cm is the CO2 concentration in mesophyll cells, Γ* is the CO2 compensation point in the absence of Rd, Kc, and Ko are the Michaelis constants for CO2 and O2, respectively, and O is the O2 concentration. Aj is expressed as:

| (10) |

where J is the electron transport rate expressed as follows:

| (11) |

where Φr is the initial slope of the curve, Jmax is the maximum electron transport rate, and θr is the convexity of the curve. The equation indicates that Aj is greatly affected by PPFD. A is also expressed as follows:

| (12) |

where Ca is the atmospheric CO2 concentration and gt is the total CO2 conductance from the atmosphere to the mesophyll cells:

| (13) |

where stomatal conductance for CO2 (gsc) is gs/1.6, and mesophyll conductance for CO2 (gmc) is 1.65 × (1.6 × gsc) (Vico and Porporato, 2008; Osborne and Sack, 2012). A is determined as the intersection of the demand functions (Eqs. (9) and (10)) and the supply function (Eq. (12)).

For C4 species, PEP carboxylation is considered as the first step of the C4 photosynthesis and expressed as follows:

| (14) |

where Vpmax is the maximum PEP carboxylation rate, Kp is the Michaelis–Menten constant of PEPC for CO2, and Vpr is an upper bound of Vp limited by PEP regeneration rate. For a given gs, the Cm that determines PEP carboxylation rate can be obtained by equating Equations (14) and (12) assuming A as Vp. For C4 species, A is a function of the CO2 concentration in the bundle sheath cells (Cbs) where carbon fixation occurs, and A is expressed as follows:

| (15) |

where Lbs is the rate of CO2 leakage from the bundle sheath to the mesophyll, which is expressed as follows:

| (16) |

where gbs is the bundle sheath conductance of CO2. Finally, A is determined as the intersection of Equations (15) and (9) or (10), where Cm is replaced with Cbs for C4 species.

In addition, E is calculated from gs and VPD as follows:

| (17) |

where VPD is obtained using Equation (3).

We selected T. aestivum with larger kopen and kclose and E. coracana with the smallest kopen and kclose as representatives of C3 and C4 species, respectively. We firstly checked the accuracy of the model prediction in the controlled fluctuating light environments in T. aestivum and E. coracana using parameters obtained from the present and previous studies (von Caemmerer, 2000; Vico and Porporato, 2008; Osborne and Sack, 2012; Table 2). We then simulated the dynamics of A, E, gs, and WUE in T. aestivum and E. coracana with original and altered kopen and kclose. The effects of decreasing kopen and kclose separately or simultaneously in T. aestivum and those of increasing kopen and kclose separately or simultaneously in E. coracana on total photosynthesis (Atotal, mmol CO2 m‒2), total transpiration (Etotal, mol H2O m‒2), and total WUE (WUEtotal, mmol CO2 mol H2O‒1) as the ratio of Atotal to Etotal during the 75-min fluctuating light period were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using R (http://www.r-project.org/). Significant differences in the physiological and morphological characteristics among species were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey–Kramer. The effects of photosynthetic types (C3 or C4), soil nitrogen conditions, and their interaction on the characteristics were determined by two-way ANOVA.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Maximum slope of the response of stomatal conductance (gs) to the increased PPFD (Slopen) and that to the decreased PPFD (Slclose) in four C3 and five C4 species grown under HN or LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S2. Relationship between mean SDmean and mean GLmean in four C3 and five C4 species grown under HN or LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S3. Dynamics of the whole-plant stomatal conductance (gs) in the controlled fluctuating light environments in four C3 species.

Supplemental Figure S4. Dynamics of the whole-plant stomatal conductance (gs) in the controlled fluctuating light environments in five C4 species.

Supplemental Figure S5. Relationship between whole-plant and leaf-level stomatal characteristics in four C3 and five C4 species grown under HN or LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S6. Relationship between the CO2 assimilation rate (Ac, Aj, Vp) and CO2 concentration in mesophyll cells (Cm) or bundle sheath cells (Cbs) described by the C3 or C4 photosynthesis models.

Supplemental Figure S7. Changes in stomatal conductance (gs), photosynthetic rate (A), transpiration rate (E), and (A/E) in the controlled fluctuating light environments simulated by the dynamic photosynthesis model in T. aestivum (A–H) and E. coracana (I–P) grown under HN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S8. Relationship between WUE during high (WUEHL) and low light period (WUELL) and time constants for stomatal opening (kopen) and closure (kclose) in four C3 and five C4 species grown under HN or LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S9. Experimental design for evaluating whole-plant water consumption in controlled fluctuating light environments.

Supplemental Figure S10. Changes in leaf temperature (TL) in the fluctuating light environments at 30-min intervals in T. aestivum and E. coracana.

Supplemental Table S1. Stomatal characteristics determined by the photosynthesis measurements in four C3 species and five C4 species.

Supplemental Table S2. Physiological and morphological characteristics of the leaves used for the photosynthesis measurements in four C3 species and five C4 species.

Supplemental Table S3. Whole-plant water use characteristics determined by the continuous measurements of pot weight in the controlled fluctuating environment in four C3 species and five C4 species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Kato, Dr Oi, Dr Mano, Dr Takahashi, and Dr Nakazono for sharing plant materials and Mr Kinoshita for developing the automatic logging application for the Bluetooth communication balance. We also thank the members of Crop Science laboratory in Nagoya University for their valuable comments and encouragement.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant for basic science research project from the Sumitomo Foundation (Grant No. 190909) and Toray science foundation (Grant No. 17-5800).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Contributor Information

Kengo Ozeki, Graduate School of Bioagricultural Sciences, Nagoya University, Chikusa, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan.

Yoshiyuki Miyazawa, Campus Planning Office, Kyushu University, Nishi, Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan.

Daisuke Sugiura, Graduate School of Bioagricultural Sciences, Nagoya University, Chikusa, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan.

D.S. and K.O. designed the experiments, D.S. and K.O collected the data, D.S. and Y.M analyzed the data, and D.S. wrote the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Daisuke Sugiura (daisuke.sugiura@gmail.com).

References

- Barratt GE, Sparkes DL, McAusland L, Murchie EH (2021) Anisohydric sugar beet rapidly responds to light to optimize leaf water use efficiency utilizing numerous small stomata. AoB Plants 13: plaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Quirk J, Buckley TN, Beerling DJ (2017) A dynamic hydro-mechanical and biochemical model of stomatal conductance for C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 175: 104–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Leitch IJ, Patel S, Pendharkar A, Knight CA (2008) Genome size is a strong predictor of cell size and stomatal density in angiosperms. New Phytol 179: 975–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano FJ, Sharwood RE, Cousins AB, Ghannoum O (2019) The role of leaf width and conductances to CO2 in determining water use efficiency in C4 grasses. New Phytol 223: 1280–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrão H, Naumann G, Barbosa P (2016) Mapping global patterns of drought risk: an empirical framework based on sub-national estimates of hazard, exposure and vulnerability. Glob Environ Change 39: 108–124 [Google Scholar]

- Clearwater MJ, Luo Z, Mazzeo M, Dichio B (2009) An external heat pulse method for measurement of sap flow through fruit pedicels, leaf petioles and other small-diameter stems. Plant Cell Environ 32: 1652–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon AG (2020) Drying times: plant traits to improve crop water use efficiency and yield. J Exp Bot 71: 2239–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Ku MSB, Edwards GE (1993) C4 photosynthesis (the CO2-concentrating mechanism and photorespiration). Plant Physiol 103: 83–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daloso DM, Dos Anjos L, Fernie AR (2016) Roles of sucrose in guard cell regulation. New Phytol 211: 809–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douthe C, Medrano H, Tortosa I, Escalona JM, Hernández-Montes E, Pou A (2018) Whole-plant water use in field grown grapevine: seasonal and environmental effects on water and carbon balance. Front Plant Sci 9: 1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake PL, Froend RH, Franks PJ (2013) Smaller, faster stomata: scaling of stomatal size, rate of response, and stomatal conductance. J Exp Bot 64: 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott-Kingston C, Haworth M, Yearsley JM, Batke SP, Lawson T, McElwain JC (2016) Does size matter? Atmospheric CO2 may be a stronger driver of stomatal closing rate than stomatal size in taxa that diversified under low CO2. Front Plant Sci 7: 1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR (1989) Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia 78: 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyland D, van Wesemael J, Lawson T, Carpentier S (2021) The impact of slow stomatal kinetics on photosynthesis and water use efficiency under fluctuating light. Plant Physiol 186: 998–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher RN, Ashley DA, Brown RH (1975) 14C-photosynthate translocation in C3 and C4 plants as related to leaf anatomy. Crop Sci 15: 55–59 [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum O, von Caemmerer S, Conroy JP (2002) The effect of drought on plant water use efficiency of nine NAD-ME and nine NADP-ME Australian C4 grasses. Funct Plant Biol 29: 1337–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum O, Evans JR, von Caemmerer S (2011) Nitrogen and water use efficiency of C4 plants. In AS Raghavendra, RF Sage, eds, C4 Photosynthesis and Related CO2 Concentrating Mechanisms. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 129–146 [Google Scholar]

- Granier A (1987) Evaluation of transpiration in a Douglas-fir stand by means of sap flow measurements. Tree Physiol 3: 309–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray A, Liu L, Facette M (2020) Flanking support: how subsidiary cells contribute to stomatal form and function. Front Plant Sci 11: 881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinski B, Jiao J, Leonardos ED (1998) Estimating photosynthesis and concurrent export rates in C3 and C4 species at ambient and elevated CO2. Plant Physiol 117: 207–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M, Gracen VE, Edwards GE (1974) Biochemical and cytological relationships in C4 plants. Planta 119: 279–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, Hattersley P, von Caemmerer S, Osmond CB (1994) Are C4 pathway plants threatened by global climatic change? In ED Schulze, MM Caldwell, eds, Ecophysiology of Photosynthesis. Springer, Berlin, pp 529–549 [Google Scholar]

- Higaki T, Hashimoto-Sugimoto M, Akita K, Iba K, Hasezawa S (2014) Dynamics and environmental responses of PATROL1 in Arabidopsis subsidiary cells. Plant Cell Physiol 55: 773–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka K, Ishikawa K, Borjigidai A, Muller O, Onoda Y (2006) Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis: mechanisms involved in the changes in temperature dependence of photosynthetic rate. J Exp Bot 57: 291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi Y, Mahendran R, Koirala S, Konoshima L, Yamazaki D, Watanabe S, Kim H, Kanae S (2013) Global flood risk under climate change. Nat Clim Change 3: 816–821 [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M, Yi Y, Yano K (2021) Revisiting why plants become N deficient under elevated CO2: importance to meet N demand regardless of the fed-form. Front Plant Sci 12: 726186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel WK, Watson-Lazowski A, Chen Z-H, Ghannoum O (2021) High intrinsic water use efficiency is underpinned by high stomatal aperture and guard cell potassium flux in C3 and C4 grasses grown at glacial CO2 and low light. J Exp Bot (In press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kimura H, Hashimoto-Sugimoto M, Iba K, Terashima I, Yamori W (2020) Improved stomatal opening enhances photosynthetic rate and biomass production in fluctuating light. J Exp Bot 71: 2339–2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Blatt MR (2014) Stomatal size, speed, and responsiveness impact on photosynthesis and water use efficiency. Plant Physiol 164: 1556–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Vialet-Chabrand S (2019) Speedy stomata, photosynthesis and plant water use efficiency. New Phytol 221: 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Matthews J (2020) Guard cell metabolism and stomatal function. Annu Rev Plant Biol 71: 273–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey ADB, Ferguson JN, Pignon CP, Wu A, Jin Z, Hammer GL, Lobell DB (2019) Water use efficiency as a constraint and target for improving the resilience and productivity of C3 and C4 crops. Annu Rev Plant Biol 70: 781–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren MR, Mathers A, Baillie AL, Dunn J, Wilson MJ, Hunt L, Pajor R, Fradera-Soler M, Rolfe S, Osborne CP, et al. (2019) Mesophyll porosity is modulated by the presence of functional stomata. Nat Commun 10: 2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Vialet-Chabrand S, Davey P, Baker NR, Brendel O, Lawson T (2016) Effects of kinetics of light-induced stomatal responses on photosynthesis and water-use efficiency. New Phytol 211: 1209–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton KG, Jarvis PG. (1991) Effects of spatial scale on stomatal control of transpiration. Agric For Meteorol 54: 279–302 [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita A, Sugiura D, Sawakami K, Ichihashi R, Tani T, Tateno M (2012) Long-term, short-interval measurements of the frequency distributions of the photosynthetically active photon flux density and net assimilation rate of leaves in a cool-temperate forest. Agric For Meteorol 152: 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Monsi M, Saeki T (2005) On the factor light in plant communities and its importance for matter production. Ann Bot 95: 549–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne CP, Sack L (2012) Evolution of C4 plants: a new hypothesis for an interaction of CO2 and water relations mediated by plant hydraulics. Phil Trans R Soc B 367: 583–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanatsiou M, Petersen J, Henderson L, Wang Y, Christie JM, Blatt MR (2019) Optogenetic manipulation of stomatal kinetics improves carbon assimilation, water use, and growth. Science 363: 1456–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW (1990) Sunflecks and photosynthesis in plant canopies. Annu Rev Plant Biol 41: 421–453 [Google Scholar]

- Qu M, Hamdani S, Li W, Wang S, Tang J, Chen Z, Song Q, Li M, Zhao H, Chang T (2016) Rapid stomatal response to fluctuating light: an under-explored mechanism to improve drought tolerance in rice. Funct Plant Biol 43: 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu M, Essemine J, Xu J, Ablat G, Perveen S, Wang H, Chen K, Zhao Y, Chen G, Chu C (2020) Alterations in stomatal response to fluctuating light increase biomass and yield of rice under drought conditions. Plant J 104: 1334–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raissig MT, Matos JL, Gil MXA, Kornfeld A, Bettadapur A, Abrash E, Allison HR, Badgley G, Vogel JP, Berry JA (2017) Mobile MUTE specifies subsidiary cells to build physiologically improved grass stomata. Science 355: 1215–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosegrant MW, Ringler C, Zhu T (2009) Water for agriculture: maintaining food security under growing scarcity. Annu Rev Environ Resour 34: 205–222 [Google Scholar]

- Scafaro AP, Von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Atwell BJ (2011) Temperature response of mesophyll conductance in cultivated and wild Oryza species with contrasting mesophyll cell wall thickness. Plant Cell Environ 34: 1999–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze E-D, Ellis R, Schulze W, Trimborn P, Ziegler H (1996) Diversity, metabolic types and δ13C carbon isotope ratios in the grass flora of Namibia in relation to growth form, precipitation and habitat conditions. Oecologia 106: 352–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantz HL, Piemeisel LN (1927) The water requirements of plants at Akron. Colorado J Agric Res 34: 1093–1190 [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Doi M, Assmann SM, Kinoshita T (2007) Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 219–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Pérez V, Furbank RT, Condon AG, Evans JR (2017) Biochemical model of C3 photosynthesis applied to wheat at different temperatures. Plant Cell Environ 40: 1552–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura D, Betsuyaku E, Terashima I (2019) Interspecific differences in how sink-source imbalance causes photosynthetic downregulation among three legume species. Ann Bot 123: 715–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura D, Terashima I, Evans JR (2020) A decrease in mesophyll conductance by cell wall thickening contributes to photosynthetic down-regulation. Plant Physiol 183: 1600–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott LD, Zeiger E (1998) The role of sucrose in guard cell osmoregulation. J Exp Bot 49: 329–337 [Google Scholar]

- Talwar HS, Kumar S, Madhusudhana R, Nanaiah GK, Ronanki S, Tonapi VA (2020) Variations in drought tolerance components and their association with yield components in finger millet (Eleusine coracana). Funct Plant Biol 47: 659–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SH, Franks PJ, Hulme SP, Spriggs E, Christin PA, Edwards EJ, Woodward FI, Osborne CP (2012) Photosynthetic pathway and ecological adaptation explain stomatal trait diversity amongst grasses. New Phytol 193: 387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trtikova M, Lohn A, Binimelis R, Chapela I, Oehen B, Zemp N, Widmer A, Hilbeck A (2017) Teosinte in Europe-searching for the origin of a novel weed. Sci Rep 7: 1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi N, Tohya M, Nakashima T, Ueno O (2017) Variations in structural, biochemical, and physiological traits of photosynthesis and resource use efficiency in Amaranthus species (NAD-ME-type C4). Plant Prod Sci 20: 300–312 [Google Scholar]

- Vialet-Chabrand S, Dreyer E, Brendel O (2013) Performance of a new dynamic model for predicting diurnal time courses of stomatal conductance at the leaf level. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1529–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vico G, Porporato A (2008) Modelling C3 and C4 photosynthesis under water-stressed conditions Plant Soil 313: 187–203 [Google Scholar]

- Vico G, Manzoni S, Palmroth S, Katul G (2011) Effects of stomatal delays on the economics of leaf gas exchange under intermittent light regimes. New Phytol 192: 640–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogan PJ, Sage RF (2011) Water-use efficiency and nitrogen-use efficiency of C3-C4 intermediate species of Flaveria Juss. (Asteraceae). Plant Cell Environ 34: 1415–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S (2000) Biochemical Models of Leaf Photosynthesis, Collingwood, Australia, CSIRO Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chan KX, Long SP (2021) Toward a dynamic photosynthesis model to guide yield improvement in C4 crops. Plant J (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way DA, Katul GG, Manzoni S, Vico G (2014) Increasing water use efficiency along the C3 to C4 evolutionary pathway: a stomatal optimization perspective. J Exp Bot 65: 3683–3693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Masumoto C, Fukayama H, Makino A (2012) Rubisco activase is a key regulator of non-steady-state photosynthesis at any leaf temperature and, to a lesser extent, of steady-state photosynthesis at high temperature. Plant J 71: 871–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Kusumi K, Iba K, Terashima I (2020) Increased stomatal conductance induces rapid changes to photosynthetic rate in response to naturally fluctuating light conditions in rice. Plant Cell Environ 43: 1230–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Peng S, Li Y (2019) Increase rate of light-induced stomatal conductance is related to stomatal size in the genus Oryza. J Exp Bot 70: 5259–5269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.