Abstract

Given that children and adolescents are at critical periods of development, they may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using a descriptive phenomenological approach, 71 parents’ observations of their child’s mental health difficulties were explored. Parents sought out treatment because their children were experiencing significant distress. Data used were transcribed from baseline questionnaires and therapy summaries. Data analysis revealed three themes: emotion regulation difficulties, hypervigilance, and despair. The search for strategies and tailored interventions to help mitigate the potential harmful and long-term mental health impacts of the pandemic should be at the forefront of research and clinical practice.

Keywords: Youth, Mental Health, COVID-19, Psychopathology, Treatment, Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, children and adolescents have been exposed to stressful situations, including loved ones contracting COVID-19, having to postpone significant life events such as school graduations, dealing with family financial loss, facing fears of contracting COVID-19, overusing the internet and social media, decreased access to health services, experiencing limited social contact with peers and family members; and having to manage drastic changes in daily activity and routines (Brooks et al., 2020; Drouin et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020). Some of these changes, particularly increased screen time and school closures, have led to a decrease in physical activity which has had significant effects on mood (Alonso-Martínez et al., 2021; Gul & Demirci, 2021). Online schooling has also been associated with unique challenges, including lack of assistance and supervision of schoolwork due to parents also having to work, difficulties with accessing technology devices needed for virtual schooling, and challenges managing distractions at home (Bartek et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2020). Likely due to these factors, many children and adolescents are having trouble staying focused, which is negatively impacting academic performance (García & Weiss, 2020; Zhao et al., 2020). Despite these difficulties, studies have also reported themes of resiliency as well as positive effects of the pandemic such as youths’ ability to use positive coping skills, changes in routine that have led to more time spent with family, and reductions in stress (Bruining et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2021).

Stressors related to the pandemic have had a direct effect on the mental health of children and adolescents. Studies have shown an increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, stress, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and sleep problems among this population during the COVID-19 pandemic (de Miranda et al., 2020; Gul & Demirci, 2021; Jones et al., 2021; Murata et al., 2020; Tanga et al., 2021). Further, youth are struggling with feelings of loneliness, helplessness, fear, worry (e.g., with either being exposed to COVID-19 or infecting others), boredom, and irritability (Loades et al., 2021; Orgilés et al., 2020; Saurabh & Ranhan, 2020). Behaviorally, youth are engaging in clinging behaviors and are having difficulties with independent sleep (e.g., asking parents to sleep in their bed), falling and staying asleep, enuresis, following house rules, concentration, and are hyperactive and restless (Jiao et al., 2020; Mallik & Radwan, 2021; Orgilés et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020; Wang et al, 2020). These symptoms and behaviors can be further exacerbated among youth who have had a family member infected or lost due to COVID-19 (Mallik & Radwan, 2021; Sahoo, Mehra, et al., 2020; Sahoo, Rani, et al., 2020).

The studies mentioned above provide an important starting point to understand youths’ mental health challenges during the pandemic. Understanding these mental health challenges is important because youth are particularly vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic given that they are in a critical period of neurological and psychological development (de Miranda et al., 2020). For example, younger children that are exposed to high levels of stress and isolation are more susceptible to developing long-term psychiatric disorders (de Figueiredo et al., 2021; Fegert et al., 2020; Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007; Jones et al., 2021). Moreover, youth may lack the ability to perceive and fully comprehend current stressors as well as the short- and long-term consequences of the pandemic (Crescentini et al., 2020; de Figueiredo et al., 2021; Imran et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2021). The psychological capabilities of resiliency and coping are also still being developed in children and adolescents. Thus, it may be more difficult for them to recover from the stressors of the pandemic compared to adults (Fields & Prinz, 1997; Jones et al., 2021; Mallik & Radwan, 2021; Power et al., 2020). For these reasons, it is important to understand the psychological effects of the pandemic among this vulnerable population to preserve and promote their mental health (de Miranda et al., 2020).

The Present Study

While several studies have examined the mental health of youth during the pandemic, there has been less research on the psychological effects of the pandemic among children and adolescents compared to other populations such as adults and the elderly (de Miranda et al., 2020; Gul & Demirci, 2021; Jones et al., 2021; Moulin et al., 2021). Within the United States, there has been a 31% increase in pediatric visits for mental health reasons from April 2020 to October 2020 (Leeb et al., 2020). Therefore, it is important to understand the symptoms and behaviors that may be related to an increase in health visits for mental health reasons during the pandemic. Most studies to date are quantitative in nature. Qualitative inquiries, like the current study, can provide rich data needed to more comprehensively elucidate the lived experiences of youth and their families during the pandemic (Churchill, 2018). The aim of the present study was to provide an in-depth exploratory qualitative analysis of parents’ observations of mental health struggles experienced by their children during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Participants

Study participants included parents who were recruited to participate in Coping with COVID, a free parent-led telehealth service to address behavioral and emotional concerns of their children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Parents were eligible to participate if they had a child between the ages of 5 and 13 years old who was experiencing mild to moderate stress or anxiety related to or exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Of note, the study sample reflected parents seeking help because their children were experiencing considerable concerns, which does not necessarily reflect the experiences of children in general. Participating families resided in the state of Texas, with all treatment sessions conducted via telehealth. Additionally, eligible parents had to be able to read and understand English and have a child who could communicate verbally. Children with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, conduct disorder, psychotic disorder, or oppositional defiant disorder were considered for eligibility on a case-by-case basis or referred to services that may be better suited to their specific needs. Three children within the current study had a prior diagnosis. The participants’ (N = 71) demographic profiles included in the current study are presented in Table 1. Parent’s mean age was 42.1 years (SD = 6.6), child mean age was 8.3 years (SD = 2.5) parent mean age was 42.1 years (SD = 6.6). Children’s ages ranged from 5 to 13 years. Majority of participants were 8 years old (17.6%) followed by 5 years (16.2%), 6 years (16.2%), 7 years (9.5%), 10 years (9.5%), 9 years (8.1%), 11 years (8.1%), and 12 years (8.1%).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Profile (Parent: n = 71; Child: n = 74)

| Demographic variables | Parent (n=71) | Child (n=74) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| N (%) | N (%) | |

|

| ||

| Sex (Female) | 68 (95.8) | 37 (50.0) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Latino/a/Hispanic | 5 (7.0) | 5 (6.8) |

| Black/African American | 3 (4.2) | 6 (8.1) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian | 12 (16.9) | 11 (14.9) |

| White | 48 (67.6) | 45 (60.8) |

| Arabic | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Multiracial | 2 (2.8) | 6 (8.1) |

| Age | ||

| 5 to 8 years | - | 44 (59.5) |

| 9 to 13 years | - | 30 (40.5) |

| 25 to 34 years | 7 (9.5) | - |

| 35 to 44 years | 37 (52.1) | - |

| 45 to 54 years | 24 (33.8) | - |

| 55 to 64 years | 3 (4.2) | - |

| Relation to Child (n = 71) | ||

| Biological parent | 67 (94.4) | - |

| Adoptive parent | 4 (5.6) | - |

| Marital Status (n = 71) | ||

| Never Married | 3 (4.2) | - |

| Separated | 1 (1.4) | - |

| Divorced | 8 (11.3) | - |

| Married/Domestic Partnership | 59 (83.1) | - |

| Highest level of education (n = 71) | ||

| High school diploma/GED | 2 (2.8) | - |

| Some college | 5 (7.0) | - |

| Associate degree | 2 (2.8) | - |

| Bachelor’s degree | 23 (32.4) | - |

| Master’s degree | 22 (31.0) | - |

| Postgraduate degree | 17 (23.9) | - |

| Employment (n = 71) | ||

| Employed full time | 38 (53.5) | - |

| Employed half time | 5 (7.0) | - |

| Unemployed looking for work | 4 (5.6) | - |

| Unemployed not looking for work | 24 (33.8) | - |

| Total household income ($) (n = 71) | ||

| 0 to 9,999 | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 10,000 to 19,999 | 1 (1.4) | - |

| 20,000 to 29,999 | 1 (1.4) | - |

| 30,000 to 39,999 | 0 (0.0) | - |

| 40,000 to 49,999 | 4 (5.6) | - |

| 50,000 to 59,999 | 4 (5.6) | - |

| 60,000 to 69,999 | 4 (5.6) | - |

| 70,000 to 79,999 | 6 (8.5) | - |

| 80,000 or over | 51 (71.8) | - |

Notes. Three parents participants participated in the program twice with different children.

Recruitment Process

From July 2020 to May 2021, families were recruited through social media, community organizations, and referrals from providers. Parents interested in the program contacted the Coping with COVID research team via email or telephone. At this point of contact, a member of the research team would first explain the parent-led structure of the program, timelines for participation in sessions, and the expected time commitment involved in program participation. Parents then participated in a 45-minute screening and baseline questionnaire over the telephone. After parents completed the baseline questionnaire and were accepted into the Coping with COVID program based on clinical protocol (inclusion/exclusion criteria), they completed consent forms for receiving telepsychiatry from the Baylor College of Medicine Psychiatry Clinic. By completing these telepsychiatry consent forms, parents consented to receiving telepsychiatry/telemedicine from physicians, psychologists, and other health care providers at the Baylor College of Medicine. Parents who returned these consent forms were then initiated on the Coping with COVID therapy program. This study was a retrospective analysis of questionnaire responses and clinical notes obtained from the charts of parents who participated in Coping with COVID. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Baylor College of Medicine and Affiliated Hospitals approved this retrospective chart review and waived the requirement of obtained informed consent for the retrospective collection and review of participants’ questionnaire responses and therapy notes from their charts. Three parents within the current study who had completed the Coping with COVID program with one child elected to participate in Coping with COVID a second time with another child who also met eligibility criteria.

Design

This qualitative study used a descriptive phenomenological approach to analyze the data (Giorgi, 1997), which has been used to explore poorly understood aspects of phenomena (Bradfield et al., 2020). This approach is rooted in description as opposed to an explanation of cause and effect and attempts to make meaning of each participant’s unique lived experience (Churchill & Wertz, 2002). Through phenomenological reductions, the researcher is reflective of their own biases and attempts to bracket, to the best of their abilities, their prior beliefs to experience the phenomenon freshly (Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003). In practicing these reductions, the researcher puts themselves fully into the participants’ shoes to experience their world experience as if it were being lived for that particular person. Reductions allow the researcher to be open to the descriptions of the other even if it is contradictory to one’s own experience (Garza, 2007). Given that the lived experiences of parents during the COVID-19 pandemic is a new area of study, the descriptive phenomenological approach is considered ideal (Bradfield et al., 2020) to address the aim of describing mental health difficulties among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the phenomenological approach will allow us to explore and understand this new topic in depth as our goal is not necessarily to derive a conclusion but instead to explore the richness of parents’ experiences by listening and observing (Churchill, 2018).

Data Collection

The data sources used for this current study were (1) the baseline questionnaire, (2) de-identified therapy notes, and (3) summaries documented in the electronic medical record (Epic). To maintain participants’ confidentiality, this data was stored in a password-protected database on the Baylor College of Medicine secure network and assigned an alphanumeric identity. Children’s parents provided consent to receive clinical care in the form of parent-led treatment, which represented standard practice. All clinical notes were contained within the parent’s medical record or the therapist’s file, both of which the caregiver could access with request.

Baseline data were collected from a questionnaire administered by a program coordinator with a bachelor-level qualification and training on conducting eligibility assessments. This 45-minute telephone call with the parent collected demographic information and the presenting problems that led to program enrollment. The questionnaire consisted of both multiple-choice and open-ended questions in which responses could be written in sentence form. In the baseline questionnaire, parents shared observations of their child’s emotional and behavioral problems during the COVID-19 pandemic when indicating top problems on the form (Ehrenreich-May et al., 2018). The current study used demographic multiple-choice data from the questionnaire to create the demographic characteristics table. Given that parents’ top problems were written in sentence form on the questionnaire, these data were pulled for the qualitative analysis.

After completing the baseline questionnaire, parents were then able to participate in the free telehealth service. The telehealth service consisted of six 50-minute therapy sessions in which the therapists used a modified version of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders in Children/Adolescents (UP-C/A; Ehrenreich-May et al., 2018). Therapy sessions were conducted by three advanced-level doctoral students in psychology with prior experience delivering cognitive behavioral therapy with children, adolescents, and families. The doctoral students participated in virtual clinical training conducted by an instructor who was certified in delivering the UP-C/A. Doctoral students also attended weekly supervisions and consultations led by a trained UP-C/A licensed psychologist.

After each session was completed, each graduate student wrote down accounts of participants’ lived experiences brought up during the session. These notes were collected as de-identified therapy notes and included information about top problems (as identified via the UP-C/A) such as emotional and behavioral concerns. A short summary of the therapists’ notes were also stored electronically on Epic and Epic notes contained core information from the session. Therapists were provided a template to use when writing notes to maintain consistency. In writing therapy notes and summaries, the therapist sought to create a concrete and detailed description of the participants’ experiences and actions (Giorgi, 1997). Once therapy notes and summaries were written, the therapists de-identified their notes and transferred these notes to a secure server to house the qualitative data.

Data Analysis

The analysis consisted of four concrete steps, including (1) reading the data, (2) breaking the data into meaningful parts, (3) organization and expression of the data from a psychological perspective, and (4) synthesis and summary of the data (Giorgi, 1997). In the first step, the researcher is confronted with descriptive accounts of participants’ experiences and begins familiarizing themself with the data by reading transcripts repeatedly (Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003). In becoming familiar with the data, the researcher looks at the readings holistically and retains a global sense of the data as opposed to trying to identify themes which will be identified later in subsequent steps (Giorgi, 1997). During the second step, the researcher begins to identify key passages, in view of the study’s aim, and intentionally identifies meaning units (Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003). In the third step, the researcher organizes and transforms the data by bringing to light trends seen among participants’ descriptions. In identifying patterns, the researcher can discern essential features of the phenomenon. To make essential features more detailed, the researcher may want to include subthemes. During the final step, the participants’ everyday experience is transformed into psychologically sensitive language and summarized.

These steps were conducted separately by three authors and the therapists (A.B., A. C., and K. Z.), who also provided treatment through the Coping with COVID program. Given the likelihood that all researchers would not have identified identical key passages (Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003), the three authors then met altogether to discuss findings and reach a consensus.

Results

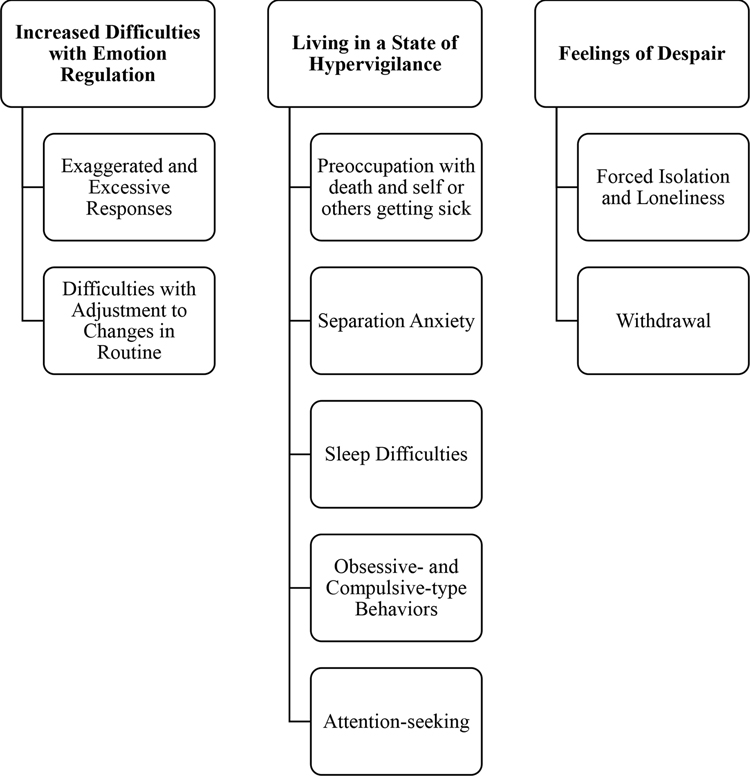

The data analysis revealed three main themes: increased difficulties with emotion regulation, living in a state of hypervigilance, and feelings of despair. Descriptions of parents’ experiences of their child’s increased difficulties with emotion regulation revealed two subthemes: exaggerated and excessive responses and difficulties with adjustment to changes in routine. Descriptions of parents’ experiences of their child living in a state of hypervigilance revealed five subthemes: preoccupation with death and self or others getting sick, separation anxiety, sleep difficulties, obsessive- and compulsive-type behaviors, and attention-seeking. Finally, descriptions of parents’ experience of their child’s feelings of despair revealed two subthemes: forced isolation and loneliness and withdrawal. The themes are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Themes and Subthemes Derived From the Data.

The meaning units of parents’ observations of youths’ mental health difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic are supported by quotations from therapy notes. These quotations are italicized. Words that have been added to these quotes with the intention of providing context are indicated by square brackets []. A unique identifier code indicates the participant interviewed and the age and sex of their child respectively. For example, (P1:10yF) indicates the unique identifier (i.e., 1) for a participant whose child was a 10-year-old female.

Theme 1: Increased Difficulties With Emotion Regulation

Parents disclosed that their children were having difficulty managing their strong and uncomfortable emotions during the pandemic. Additionally, their child’s behaviors in response to emotions were more extreme than they had been prior to the pandemic. Behaviors observed by parents included screaming, crying, fighting with siblings and family members, not following house rules, hitting, kicking objects, and slamming doors. Given the new intensity of felt emotions, it was difficult for children to cope and return to baseline or a parasympathetic state. When faced with changes in routine, and since their emotional state was already fragile, it was challenging for them to adjust to new situations such as virtual schooling.

Subtheme: Exaggerated and Excessive Responses

Parents noticed that their child’s ability to regulate emotions had changed drastically since the start of the pandemic. Many parents expressed how their child’s responses to emotions were new and different and that their child was able to regulate emotions more effectively prior to the pandemic: [Parent] has noticed new behaviors such as tantrums (screaming, crying, and kicking the ground). [She] never had behavioral problems before COVID (P2:6yF). Similarly, other parents expressed: He was able to manage his emotions prior to COVID but since then it has been increasingly difficult for him to do so (P13:6yM).

One way that parents experienced their child’s emotional reactions during the COVID-19 pandemic was that their child seemed to be in a persistent underlying uncomfortable emotional state: [She] often appears teary-eyed (P2:6yF). It’s like [she has] an unnamable want that she doesn’t know how to satisfy or what will satisfy it which leads to crying very suddenly or being angry (P10:12yF). Parents also noticed that their child’s emotional state appeared fragile, and it was easy to upset them: [She is] reactive and cries about everything now (P20:6yF). [Her] emotions are all over the place. [She is] happy one second and mad the other (P2:6yF).

When their child became upset, parents experienced their child’s reaction as exaggerated or excessive: [He] becomes easily frustrated and overreacts (P43:10yM). Child blows fears about what is happening in the world out of proportion (P6:5yM). Additionally, behavioral difficulties (e.g., meltdowns, hitting) either increased in intensity, were more frequent, or new behaviors were apparent: [There is] increased frequency and intensity of meltdowns (P31:8yF). [She] has struggled with anger since 3 but it has been exacerbated with COVID. (P7:11yF). [He] has gotten a lot more physical when frustrated [and] angry. (P16:13yM). Those parents with a child who had a previous mental health diagnosis also noticed that their symptoms related to the diagnosis worsened: [His] ADHD [has] exacerbated (P16:13yM). Given that emotional responses had increased in intensity, it was difficult for children to recover from strong emotions: Difficulty managing emotions and calming down, inappropriate interactions with family, hits sister and mom, angry, crying a lot, hitting and kicking, [and is] explosive (P44:8yM).

Subtheme: Difficulties With Adjustment to Changes in Routine

Parents disclosed that their children had a low tolerance for changes in routine in general: Changes in routine [have] really affected him (P14:7yM). When faced with a change in routine, children often displayed behavioral outbursts: When things do not happen in a certain way [she] is angry. [She] slams doors and makes inappropriate verbal comments (P1:10yF). Parents expressed that their children were also bored and less active given physical distancing restrictions: [She] is sad and bored that she cannot engage in previous pleasurable activities due to COVID-19 restrictions (P5:6yF).

The transition from going to school in-person to learning virtually was especially difficult for children: [She’s had] difficulty transitioning to online learning and becomes frustrated and angry when completing schoolwork. [She] shuts down and is talking back. [She] asks for help but it turns into a fight when mother tries to help her with schoolwork (P5:6yF). Once children were attending virtual school, it was stressful and challenging for them to adapt to this new learning style: [She] does not know how to deal with stress related to virtual schooling. [With respect to] virtual schooling, the small breakout rooms are challenging, and it creates frustration. She interrupts others and engages in sarcasm (P1:10yF). [The] online school breakout rooms are challenging. [He has a] difficult time paying attention (P3:8yM). Parents disclosed that it was difficult for their child to engage and participate in school: [He] does not want to participate or engage in virtual schooling and brings up emotions such as anger and anxiety (P3:8yM). As a result, their children’s academic performance suffered: [He] failed 3 classes even though he has always had straight A’s [and has] decreased motivation and attention (P45:12yM). Ultimately, parents felt like their children were giving up and uninterested in participating: He has been in virtual school, and he has lower tolerance for school. He is more likely to give up (P19:10yM). With their child’s academic performance suffering, parents felt like they needed to send their child back to school when it was an option for them to do so: He is going back to school in person because he is slacking off and has been having difficulty focusing with virtual schooling (P17:11yM).

Theme 2: Living in a State of Hypervigilance

Parents felt like their children were living in a constant state of hypervigilance. They were hyperaware of themselves and/or others contracting COVID-19, and they knew the ultimate threat of getting sick was death. Within this hyperaware state, children would often jump to conclusions or think the worst would happen if they did not follow COVID-19 precautions or if they and/or others contracted COVID-19. Children experienced their world as being out of control and had difficulty coping with uncertainty. In order to seek relief, children engaged in several behaviors (e.g., rituals, excessive handwashing, not eating with others, monitoring other’s prevention behaviors, making sure parents were in close proximity so they knew nothing bad would happen to them) in an attempt to seek control. However, uncertainty remained despite these efforts, which made it difficult for them to fall and stay asleep at night.

Subtheme: Preoccupation With Death and Self or Others Getting Sick

Parents noticed that their children were worried that people close to them would get sick. Children were mostly concerned about their parents or grandparents contracting COVID-19: [She] has anxiety and is scared something will happen to her mom, scared she will get COVID or that her grandparents will get it (P10:12yF). The anxiety manifested behaviorally as seeking reassurance, asking questions, and grabbing parents in an attempt to prevent them from going out into society: [She is] worried that something bad will happen to parents and needs reassurance (P4:13yF). [He is] worried something will happen to [his] mom with respect to COVID. [He] grabs onto mother and repeatedly asks questions. For example, has dad been in an accident? (P6:5yM).

Parents commented that their children were also worried about themselves getting sick: [He] will state that he is scared of getting sick (P19:10yM). [He is] crying at night (around bedtime), says stomach hurts, says “I don’t want to die” (P30:8yM). Children were aware that the ultimate threat of catching COVID-19 was death, and this fear preoccupied their minds regularly: [He is] preoccupied with death and contracting COVID. [He] ruminates on anxious thoughts and asks questions about death (P6:5yM). Children generally felt that they were following steps themselves to prevent contracting COVID-19 but were worried about other people’s choices which were beyond their control: [She is] worried that relatives are not being as careful as her with respect to COVID precautions (P2:6yF). [He is] scared of other people’s choices (i.e. not wearing a mask) (P57:5yM). Not being able to control other people’s behaviors and whether or not they would contract COVID-19 as a result of others not following precautions, likely increased their anxiety about going back out into society. Parents noticed that their children were hesitant to return to school once in-person classes were an option: [She is] fearful of returning to campus because of COVID (P41:13yF). [He has] fear of going to school in person and anxiety about leaving the house (P47:13yM).

Subtheme: Separation Anxiety

Parents observed that their children did not want to be alone. Generally, children felt safer and more secure only when they were near their parents: He wants parents to be around when doing virtual schooling (P13:6yM). [He has] increased fear and needs mom to be near him at all times. [He is] scared of being by self (P27:9yM). Children also regressed in terms of tasks they could do independently. Parents noticed that their children had increased difficulty engaging in tasks on their own that they were once able to complete independently, particularly bedtime routines: Mother has to go into child’s bedroom every 10 minutes until she falls asleep because she has a fear of being upstairs. All of March child slept in parent’s room because worried about homework and COVID (P4:13yF). [He has] difficulties with brushing teeth independently [and] fear of going upstairs independently (P15:8yM). If parents attempted to get their child to engage in tasks independently, their child would either cling to them or yell for them in hopes that they would return so that nothing bad would happen to them or their parents: [She has] lots of anxiety when parents leave the room and would yell for them (P12:6yF). When parents leave the room, he is worried something bad will happen to them and will start clinging to parents (P15:8yM).

Subtheme: Sleep Difficulties

Parents expressed that since the pandemic started, they noticed that their child had increased difficulties with sleep. Children were having difficulty falling asleep: She stays up a lot more often and mother has started to give her Melatonin (P20:6yF). and staying asleep: [He has] sleep problems and is waking up very early (1AM to 4AM) (P17:11yM). Nocturnal enuresis and nightmares were also preventing them from sleeping through the night: [She is] bedwetting [and has] sleep disturbances (P54:6yF). [She is] having nightmares and waking up at night screaming (P2:6yF).

Subtheme: Obsessive- and Compulsive-Type Behaviors

Parents noticed that their children began to exhibit OCD-like behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children started to engage in rituals so that nothing bad would happen to themselves or loved ones: When [her] father leaves home, [she] has to pray [and] takes keys if father does not kiss her goodbye. [She] has to engage in kissing in a certain way and has to apologize for anything bad that she did (P4:13yF). [He engages in] compulsions for up to 2 hours [and has a] nighttime ritual [and] checks locks (P64:9yM). Parents mentioned that they felt like their children experienced a sense of loss of control: Parent thinks that child wants more control and is frustrated by lack of control (P9:5yF). In order to have some control over their lives, children wanted things done in a certain way or they would become upset: Did not want mother to throw things away. [He engages in] hoarding behaviors which are new, and mother thinks it is to increase control. [He experiences a] loss of control and in order to get control he does not let people move his things (if his mother moves one LEGO he becomes upset) (P6:5yM).

Specifically, related to fears of contracting COVID-19, parents noticed that their children experienced contamination fears and would engage in behaviors to try to prevent themselves from becoming contaminated: [He is] scared of other people touching him (like when he was playing football with friends) (P15:8yM). Prevention strategies used by their children were often excessive and severe: His skin/hands are turning raw from obsessive hand/body washing. [He] uses hot water [and is] flying through soap and Clorox. [His] parents are having to wrap hands and put on lotion gloves because child’s hands were cracking and blistering due to handwashing. [He] questions everything related to COVID contamination and will ask mom every day for reassurance about cleanliness [and] safety from COVID. (P16a:13yM). In addition to handwashing, children were fearful of eating with others: [He has] anxiety about eating food around people because of germs (spit particles) and has recently stopped eating at the dinner table with family (P19:10yM). [She] won’t eat something that others in the family [have] touched (P10:12yF). If children found themselves in a situation in which someone was eating, they particularly did not like the sound of chewing: [She] doesn’t like chewing noises and coughing. Does not like to hear brother chewing in the car (her brother eats breakfast in the car), and she will kick him. [She] engages in compulsions such as clearing throat, adjusting pants, putting her ear to her shoulder when she hears other people chewing or coughing (P21:6yF).

Subtheme: Attention-Seeking

Parents noticed that their children needed more attention from them than usual. If parents were trying to work from home or give attention to other family members, their children would become upset and seek out their attention by having a meltdown: [She] started to have more meltdowns when parents are unable to provide her immediate attention (for example, when working from home). [She is] interrupting parents and wants lots of attention. If she does not get attention, she has a meltdown, tantrums, or shuts down. [She is] jealous when parents spend time together (P8:5yF).

Theme 3: Feelings of Despair

Parents disclosed that their children felt forced into isolation. While engaging in physical distancing, children felt lonely, frustrated, bored, and sad. A sense of despair dominated their social lives, and children began to withdraw and isolate. They were not interested in engaging in activities they once found pleasurable or trying out new and/or modified activities that were considered more appropriate during the pandemic.

Subtheme: Forced Isolation and Loneliness

Parents identified that their children were feeling isolated, lonely, and sad when following physical distancing practices: [She is] feeling isolated because she cannot interact with friends (P1:10yF). [She has feelings of] sadness about not being able to see grandparents due to COVID (P2:6yF). Loneliness and despair over life not being the same (P18:6yF). Children missed the social interactions that were automatically provided to them from going to school, and not being able to receive these interactions regularly was frustrating: [He] has anger and frustration because he cannot go to school. He is very social and dependent on his friends (P13:6yM). Social isolation has led to become physically angry (throwing objects) (P16:13yM).

Subtheme: Withdrawal

Parents noticed that their children began to withdraw and did not want to engage in activities that they once found pleasurable: [She is] not interested in playing with friends (P1:10yF). She does not want to go outside or do fun things (P9:5yF). [She is] isolating from family (P41:13yF). Children also struggled to find interest in alternative activities: Because of COVID restrictions, [there is a] sense of sadness/bored[om] and [she] will not want to engage in other activities (P5:6yF). [She] feels like she cannot do anything fun. [She] shuts down, doesn’t want to listen and cries (P8:5yF). Loss of socialization, sports, and extracurricular activities and responds with avoidance by not wanting to get on family Zoom calls (P13:6yM).

Discussion

The current study qualitatively examined descriptions of parents’ experiences of their child’s mental health difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of note, parents opted in for treatment because their children were experiencing significant distress related to the pandemic. Therefore, this sample does not necessarily reflect the experiences of children in general. Findings revealed that children and adolescents struggled with several symptoms which were categorized under three main themes: increased difficulties with emotion regulation, living in a state of hypervigilance, and feelings of despair. Parents perceived these difficulties in their children to be new or exaggerated and pervasive, which prompted them to participate in our study and undergo treatment in which therapists used a modified parent-led transdiagnostic intervention to help parents manage their child’s behaviors and emotions during the pandemic. Common symptoms described by parents included difficulties regulating emotions and adjusting to changes in routine, preoccupation with death and sickness, separation anxiety, sleep difficulties, obsessive- compulsive type behaviors, attention-seeking, loneliness, and withdrawal.

Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Loades et al., 2021; Orgilés et al., 2020; Saurabh & Ranhan, 2020), emotions such as loneliness, fear, worry, and irritability were also observed in the current study. Additionally, behavioral difficulties such as clinging, sleep, and following house rules were also noted among parents which were similar to other study’s findings (e.g., Jiao et al., 2020; Mallik & Radwan, 2021; Orgilés et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020; Wang et al, 2020). One striking observation by parents was that their children began to exhibit OCD-like behaviors during the pandemic. Most of the recent pandemic literature on OCD symptoms in youth focuses on those youth who had OCD prior to the pandemic and examined how these symptoms have worsened (Nissen et al., 2020; Tanir et al., 2020; Storch et al., 2021). However, many participants in our study saw their children struggling with OCD-like behaviors for the first time and it appears that the pandemic was a trigger to symptom development. Participants in our study attributed the development of OCD-like behaviors due to a felt sense of loss of control in their children during the pandemic and contamination fears. Unfortunately, given the brevity of sessions, it is unclear if these symptoms resolved with the passing of time and/or COVID-related risk levels (e.g. community case levels, or vaccination rollout). More research is needed on this subpopulation of children that developed OCD-behaviors during the pandemic. One possible explanation could be that the pandemic was a trigger and the precipitating event that led to the presentation of OCD in children who were potentially genetically predisposed. It is also worth noting that with both business and school closures during the pandemic, parents were at home with their children and therefore there were more opportunities for observation. It is possible that these children had subclinical symptoms of OCD prior to the pandemic but these symptoms were not seen as severe enough for parents to make significant note of until these symptoms were exacerbated due to COVID-19.

The current results also further highlight the need for psychological interventions to be tailored and available to help youth cope with public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Tang et al., 2021). To engage families with children experiencing various challenges during the pandemic, interventions could broadly address common mental health difficulties and their longer-term effects on sleep hygiene and activity re-engagement. Furthermore, the demand for mental health services during the course and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to remain high, and it is imperative that we ensure that youth have access to effective treatment services (Waddell et al., 2020). Evident from the current study and others (e.g., de Miranda et al., 2020; Gul & Demirci, 2021; Jiao et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2021; Loades et al., 2021; Mallik & Radwan; Murata et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2020; Pisano et al., 2020; Saurabh & Ranhan, 2020; Tanga et al., 2021; Wang et al, 2020), youth have had a variety of mental health difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic, and mental health providers should be prepared to treat many types of symptoms related to the toll of the pandemic.

Limitations

The current study shed further light on mental health concerns in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic (Leeb et al., 2020). The qualitative nature of this study enabled us to expand upon results from previous quantitative studies. Specifically, the descriptive phenomenological approach used in this study allowed us to explore parents’ descriptions in an in-depth manner to understand specific symptoms that youth are struggling with during the pandemic.

Despite the study’s strengths, the current study had several limitations. First, this study focused on only one perspective, which was the negative aspects of the pandemic that contributed to poor mental health in children and adolescents. Assessment of mental health resiliency factors and potential positive aspects of the pandemic should be explored in future work (e.g., reduction of social pressure, more time to think and reflect) (Bruining et al., 2020). Second, the data reflect experiences specific to families at that specific point in time. The COVID pandemic can be expected to have different effects on child mental health depending on a multitude of factors including the local severity of COVID impacts, access to health care, local public policy, access to vaccination, etc. Given that the need for mental health services during the course of the pandemic will likely remain high (Waddell et al., 2020), it is important that researchers continue to collect data on how children and adolescents are coping with the pandemic over time and in different locations. Third, recruitment efforts may have left out valuable populations, as the sample included parents who volunteered to participate in the current study. Fourth, the data included only parent reports, so we were unable to corroborate parents’ perspectives with their child’s experience. Fifth, given that sessions were not video or audio recorded, therapists wrote down parent observations by recall. Therefore, the data collected may be subject to recall errors. Sixth, the sample was highly educated and higher income which is not representative of the entire state of Texas. Seventh, the sample consisted of parents who sought treatment due to their children’s mental health concerns. Therefore, the study did not include a sample that was randomly selected. Finally, the sample included mostly mothers. Thus, father’s perspectives of their child’s mental health difficulties during the pandemic were limited in the current study.

Implications for Practice

The current study reveals the unique experiences of parents’ observations and management of mental health struggles in their children. The detailed knowledge gained in this study provides important insight into understanding specific mental health difficulties that youth faced during the COVID-19 pandemic which may be helpful to practitioners in supporting families during the pandemic. Specifically, the present study found from parents’ accounts that youth reportedly struggled with emotion regulation, hypervigilance, and feelings of despair.

Mental health providers can use already available evidence-based interventions to treat disorders such as anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, behavioral problems, and post-traumatic stress that have developed or worsened within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Comer et al., 2019; Dorsey et al. 2016; Freeman et al., 2018; Higa-Mcillan et al., 2016; Kaminski & Claussen, 2017; McCart & Sheidow, 2016; Waddell et al., 2020; Weersing et al., 2017). Providers can also direct caregivers to resources developed by established agencies to help manage their child’s mental health needs during the pandemic (Imran et al., 2020). Within the context of the pandemic more specifically, several components within mental health treatment are crucial, including daily routines, sleep hygiene, activity engagement, parent-child communication and validation, and limits on screen time (Bartek et al., 2021; Imran et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020). These domains improve the mood of children and adolescents and are protective factors against symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress (Bartek et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2020; Imran et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021).

With the recent rise of the Delta variant in the United States, families will need continued support managing such symptoms. Consequently, disseminating strategies and tailoring interventions to help mitigate the potential harmful and long-term impact of the pandemic should be at the forefront of clinical practice. Moreover, public health interventions that address population mental health need to be more widespread. Practitioners could use websites, school resource pages, and handouts at primary care centers in order to promote public health interventions.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Greater Houston Community Foundation and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P50HD103555 for use of the Clinical and Translational and Preclinical-Clinical Core facilities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alonso-Martínez AM, Ramírez-Vélez R, García-Alonso Y, Izquierdo M, & García-Hermoso A (2021). Physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep and self-regulation in Spanish preschoolers during the COVID-19 lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartek N, Peck JL, Garzon D, & VanCleve S (2021). Addressing the clinical impact of COVID-19 on pediatric mental health. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 35(4), 377–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield Z, Hauck Y, Duggan R, & Kelly M (2020). Midwives’ experiences of learning and teaching being ‘with woman’: A descriptive phenomenological study. Nurse Education in Practice, 43, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, & Rubin GJ (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruining H, Bartels M, Polderman TJC, & Popma A (2020). COVID-19 and child and adolescent psychiatry: An unexpected blessing for part of our population? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill SD (2018). Explorations in teaching the phenomenological method: Challenging psychology students to “grasp at meaning” in human science research. Qualitative Psychology, 5(2), 207–227. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill SD, & Wertz FJ (2002). An introduction to phenomenological research psychology: Historical, conceptual, and methodological foundations. In Schneider KJ, Bugental JFT, and Pierson JF (Eds.), The handbook of humanistic psychology: Leading edges in theory, research, and practice (pp. 247–262). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Hong N, Poznanski B, Silva K, & Wilson M (2019). Evidence base update on the treatment of early childhood anxiety and related problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crescentini C, Feruglio S, Matiz A, Paschetto A, Vidal E, Cogo P, Fabbro F (2020). Stuck outside and inside: An exploratory study on the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on Italian parents and children’s internalizing symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Figueiredo CS, Sandre PC, Portugal L, Mázala-de-Oliveira T, da Silva Chagas L, Raony Í, Ferreira ES, Giestal-de-Araujo E, Dos Santos AA, & Bomfim PO (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Miranda DM, da Silva Athanasio B, Oliveria ACS, & Simoes-e-Silva AC (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, McLaughlin KA, Kerns SEU, Harrison JP, Lambert HK, Briggs EC, Cox JR, & Amaya-Jackson L (2016). Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 303–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin M, McDaniel BT, Pater J, & Toscos T (2020). How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(11), 727–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich-May J, Kennedy SM, Sherman JA, Bilek EL, Buzzella BA, Bennett SM, & Barlow DH (2018). The unified protocols for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents (UP-A) and children (UP-C): Therapist guide. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, & Clemens V (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(20), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields L, & Prinz RJ (1997) Coping and adjustment during childhood and adolescence. Clinical Psychology Review, 17(8), 937–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J, Benito K, Herren J, Kemp J, Sung J, Georgiadis C, Arora A, Walther M & Garcia A (2018). Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: Evaluating, improving, and transporting what works. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(5), 669–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, Wang Y, & Dai J (2020) Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García E, & Weiss E (2020). COVID-19 and student performance, equity, and U.S. education policy. Economic Policy Institute.

- Garza G (2007). Varieties of phenomenological research at the University of Dallas: An emerging typology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(4), 313–342. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi A, 1997. The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 28, 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi A, & Giorgi B (2003). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In Camic PM, Rhodes JE, and Yardley L, (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 243–273). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Gul MK, & Demirci E (2021). Psychiatric disorders and symptoms in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Eurasian Journal of Medicine and Oncology, 5(1), 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M, & Quevedo K (2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review Psychology, 58, 145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran N, Zeshan M, & Pervaiz Z (2020). Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 pandemic. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36, COVID19-S67-S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, Fang SF, Jiao FY, Pettoello-Mantovani M, & Somekh E (2020). Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. The Journal of Pediatrics, 221, 264–266.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EAK, Mitra AK, & Bhuiyan AR (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski J & Claussen A (2017). Evidence based update for psychosocial treatments for disruptive behaviors in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(4), 477–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb R, Bitsko R, Radhakrishnan L, Martinez P, Njai R, & Holland K (2020). Mental health–related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 1–October 17, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6945a3.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, Linney C, McManus MN, Borwick C, & Crawley E (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik CI, & Radwan B (2021). Impact of lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic in changes of prevalence of predictive psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCart MR, & Sheidow AJ (2016). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 45(5), 529–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin F, El-Aarbaoul T, Bustamante JJH, Héron M, Mary-Krause M, Rouquette A, Galéra C, & Melchior M (2021). Risk and protective factors related to children’s symptoms of emotional difficulties and hyperactivity/inattention during the COVID-19-related lockdown in France: Results from a community sample. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, Marengo L, Krancevich K, Chiyka E, Hayes B, Goodfriend E, Deal M, Zhong Y, Brummit B, Coury T, Riston S, Brent DA, & Melhem NM (2020). The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depression and Anxiety, 38, 233–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen JB, Højgaard D, & Thomsen PH (2020). The immediate effect of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 20(511), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgilés M, Morales A, Delvecchio E, Mazzeschi C, & Espada JP (2020). Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisano L, Galimi D, & Cerniglia (2020). A qualitative report on exploratory data on the possible emotional/behavioral correlates of Covid-19 lockdown in 4–10 years children in Italy. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Power E, Hughes S, Cotter D, & Cannon M (2020). Youth mental health in the time of COVID-19. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37, 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S, Mehra A, Suri V, Malhotra P, Yaddanapudi N, Puri GD, & Grover S (2020). Handling children in COVID wards: A narrative experience and suggestions for providing psychological support. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S, Rani S, Shah R, Singh AP, Mehra A, & Grover S, 2020. COVID-19 pandemic-related anxiety in teenagers. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(3), 328–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh K, & Ranjan S (2020). Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to Covid-19 pandemic. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 87(7), 532–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah K, Mann S, Singh R, Bangar R, & Kulkarni R (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and adolescents. Cureus, 12(8), e10051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Sheu JC, Guzick AG, Schneider SC, Cepeda SL, Rombado BR, Gupta R, Hoch CT, & Goodman WK (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on exposure and response prevention outcomes in adults and youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanga S, Xiang M, Cheung T, & Xiang Y-T. (2021). Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanir Y, Karayagmurlu A, Kaya İ, Kaynar TB, Türkmen G, Dambasan BN, Meral Y, & Coşkun M (2020). Exacerbation of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Researc. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell C, Schwartz C, Barican J, Yung D, & Gray-Grant D (2020). COVID-19 and the Impact on Children’s Mental Health. Children’s Health Policy Centre and Simon Fraser University. https://rcybc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CHPC-Impact-of-COVID-on-Children_5-Nov-2020_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, & Ho RC (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing RV, Jeffreys M, Do MT, Schwartz KTG, & Bolano C (2017). Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(1), 11–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Guo Y, Xiao Y, Zhu R, Sun W, Huang W, Liang D, Tang L, Zhang F, Zhu D, & Wu J (2020). The effects of online homeschooling on children, parents, and teachers of grades 1–9 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical Science Monitor, 26, e925591–1–e925591–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]