Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease is fast becoming a disease of the East. Of all its entities, Crohn’s disease is the most diverse and debilitating due to its nature of transmural granulomatous inflammation. The clinical picture varies according to the disease location and severity. This translates to tailoring the treatment according to individual disease. The management should be predominantly medical since recurrence rates post-surgery are objectionable. But surgery, as a measure to tackle complications under cover of adequate medical and nutritional therapy, can be lifesaving. Herein, we describe a series of seven cases where surgery was crucial in the management of Crohn’s disease.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprising Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and indeterminate colitis are idiopathic, granulomatous, relapsing inflammatory diseases of the bowel [1]. Although IBD is considered a disease of the West, recent trends show an increasing incidence in Asia [2]. Factors like urbanization, Western diet and improved diagnostic facilities are believed to attribute to this effect. With mounting evidence hinting that the burden of IBD in the East may surpass that of the West in the recent future, one needs to be acquainted with all possible clinical scenarios and various treatment strategies.

The chronic nature of IBD with its intestinal and extra intestinal manifestations causes significant burden on the physical and economic status of the affected individual [1]. CD, especially, can affect any part of the alimentary tract from the mouth to the anus causing a myriad of clinical pictures. Unlike UC, the treatment for CD is predominantly medical and surgery is reserved to tackle complications [3]. We describe a series of seven cases of CD compiled over a period of 24 months, that presented with different complications where surgery played a key role in the disease management.

CASE SERIES

Case 1

A 55-year-old female presented with diffuse, colicky abdominal pain, fever and vomiting for 10 days. She gave a history of intermittent diarrhoea with significant weight loss over 6 months. The patient had undergone laparotomy for ileal perforation 1 year ago. On clinical examination, she had tenderness and rigidity of abdomen in all quadrants with absent bowel sounds. Emergency computed tomography (CT) abdomen revealed pneumoperitoneum with multiple air pockets and fluid collections along the distal ileum.

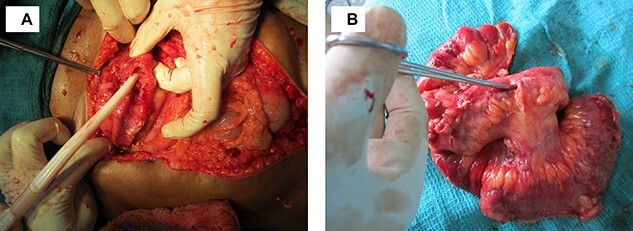

Based on these, a diagnosis of bowel perforation was established, and emergency laparotomy was undertaken. Intraoperative findings were dense adhesions with pus pockets involving distal ileum, caecum and sigmoid colon with multiple perforations in the distal ileum about 25 cm from the ileocaecal junction. The perforated segment was resected (Fig. 1A, B), and the ends brought out as ileostomy in the right iliac fossa. Following histopathology confirming features of CD, the patient was managed medically with steroids and anti-TNF agents. Closure of ileostomy was performed after 18 months, during a remission phase.

Figure 1.

Multiple ileal perforations (A) Intraoperative—largest perforation pointed (B) Resected specimen.

Case 2

A 33-year-old male came with right lower abdominal pain and fever for 2 days. Clinical exam revealed McBurney’s point tenderness with right iliac guarding. CT abdomen showed an inflamed appendix in the retrocaecal position. He underwent emergency appendicectomy for acute appendicitis (Fig. 2). On receiving a pathological diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, colonoscopy was done. No other affected areas were noted in the colon. He has been under follow-up for 2 years with no further symptoms.

Figure 2.

Acute retrocaecal appendicitis.

Case 3

A 48-year-old male presented with lower abdominal pain, fever and vomiting for 3 days duration. He mentioned history of alternating bowel habits for 5 years. Abdomen examination showed tenderness and guarding over the right iliac and supra pubic regions. CT abdomen showed an inflamed appendix with possible perforation. He underwent an emergency appendicectomy. Intraoperatively, he had an inflamed appendix with a perforated tip and a contained collection. Histopathology showed non-caseating, transmural granulomatous inflammation. Post-operative colonoscopy showed skip lesions in some areas of ascending and transverse colon.

He was started on 5-ASA. He improved and has had satisfactory disease control for 2 years.

Case 4

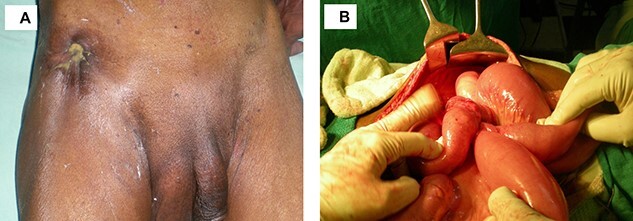

A 63-year-old male presented with abdominal pain and distension for 3 days preceded by constipation for 6 days. He also mentioned an ulcer over his right groin discharging faeces on and off for 1 year and past history of intermittent diarrhoea with rectal bleeding for over 10 years. On examination, he had a 2 × 3cm ulcer with inverted edges over the right inguinal region, 1 cm above the inguinal ligament and 2 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, discharging faeculent material. The abdomen was distended with absent bowel sounds. CT fistulogram showed inflammatory wall thickening of distal ileal loops causing partial bowel obstruction and an enterocutaneous fistula from the ileocaecal to the inguinal region.

On laparotomy, this patient had an ileocecal mass with a cecal fistula arising from the posteroinferior surface of the caecum. A loop of proximal ileum was densely adherent to the anterior surface of the ileocecal junction (Fig. 3A, B). There was no significant contamination of the peritoneal cavity. Hence, a limited resection of the ileocecal region was performed and ileocolic and ileoileal anastomoses were done after resection of the adherent loop. The abdominal wound was managed by debridement and delayed closure. Histopathology showed features of Crohn’s inflammation and follow-up colonoscopy showed several diseased areas in the colon and rectum. The patient recovered well with nutritional support, antibiotics and additional anti-TNF therapy.

Figure 3.

Enterocutaneous fistula (A) pre-operative (B) intra-operative-Ileocaecal mass adherent to the abdominal wall.

Case 5

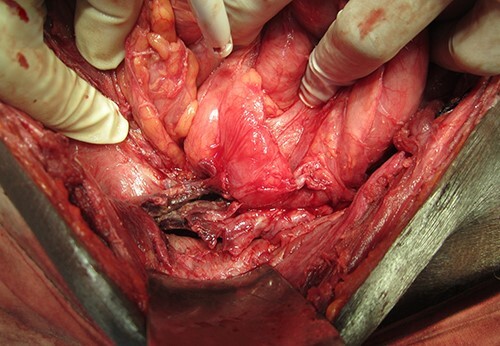

A 50-year-old male presented with abdominal pain, distension and constipation for 5 days with past history of alternating bowel habits for many years. Examination revealed a distended abdomen with diffuse tenderness, lower abdominal rigidity and absent bowel sounds. Emergency CT abdomen showed evidence of gangrenous bowel loops in ileocaecal region causing obstruction.

Emergency laparotomy revealed a gangrenous loop of distal ileum densely adherent to the caecum (Fig. 4). Attempts to release this segment from the posterolateral region failed and so a proximal ileostomy was done. Histopathology of partially resected specimen showed mucosa with deep inflammatory ulcers and transmural fissuring. The patient was started on 5-ASA and steroids. Anti-TNF agents were contemplated but he was lost to follow-up after 2 months.

Figure 4.

Distal ileal gangrene causing obstruction—gangrenous ileal loop adherent to the caecum and lateral abdominal wall.

Case 6

A 19-year-old female presented with history of offensive discharge from an opening near anus for 1 month with pain and fever for 2 days. She had a history of rectal bleeding on and off for 2 years. Examination revealed a fistula-in-ano discharging pus with external opening at 7 o’clock. The anal mucosa was inflamed and irregular. MR fistulogram showed a low fistula-in-ano with external opening at 7 o’clock and a corresponding internal opening with an adjacent perianal abscess. Colonoscopy revealed aphthous ulcers in the colon with cobblestone appearance and classic skip lesions.

This patient’s perianal abscess adjoining the fistula was drained. The fistulous track was explored and a loose seton was placed. She showed signs of resolution of fistula with antibiotics and anti-TNF therapy.

Case 7

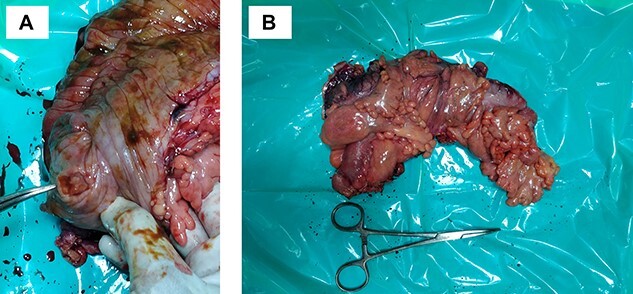

A 56-year-old male presented with episodic diarrhoea with rectal bleeding for 6 months and an unintentional significant weight loss. He also gave history of alternating bowel habits, multiple joint aches and low back ache for over 5 years. The clinical signs were scarce except for mild tenderness in the right iliac region. On colonoscopy, there were discrete, deep, longitudinal ulcers in the ascending colon and caecum. Histopathology showed invasive adenocarcinoma in biopsies from the caecal ulcer and chronic reactive inflammation elsewhere.

So, he underwent a right hemicolectomy with ileocolic anastomosis (Fig. 5 A and B). Histopathology revealed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma invading the muscularis propria (pT3) with no regional nodal involvement or metastases. The patient was offered adjuvant chemotherapy and is on regular follow-up.

Figure 5.

Colonic malignancy (A) malignant caecal ulcer (B) resected specimen.

DISCUSSION

CD causes granulomatous transmural inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. This predisposes the affected individual to suffer more debilitating symptoms than UC [1]. Its etiopathogenesis is an interaction between genetic and environmental factors complexed with immune dysregulation triggered by gut microbiota alterations [4]. The recent concept of ‘envirotype’ shaping the patient’s microbiome is reiterated by the study in immigrants, where only the second generation developed incidence of IBD matching the local population signifying an early environmental exposure causing the dysbiosis [5]. In the previous years, IBD was considered a disease of the Western world, but now is increasingly being reported in the East [2]. Despite the incidence being lesser than the West, we were able to surgically manage seven CD patients in 24 months at a tertiary care facility in South India.

CD occurs in a bimodal fashion with the first peak in second to third decade and the second peak in the sixth decade [6]. The common initial symptoms are diarrhoea, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, fever and unexplained weight loss. The symptomatology, however, can vary widely based on the affected site and severity. CD manifesting as an initial perianal pathology or an isolated appendicitis-like clinical presentation is not unheard of. About 25% of the patients with ileal CD and 50% with colonic CD have appendicular disease [7]. Two of our cases came with the initial presentation of appendicitis. Perianal disease may occur in a wide range of patients (18%–43%) and at a higher frequency in case of colonic CD [8].

The Vienna classification (1998) and its refinement, the Montreal classification (2005) aim at typing the disease based on the age of onset, disease location and disease behaviour. The disease location tends to be stable for many years whereas the disease behaviour can drastically change from inflammatory (non-stricturing, non-penetrating) to either the stricturing type or the penetrating type [9]. Isolated colonic disease runs a less aggressive course but is more likely to present with perianal and extra intestinal symptoms [10]. As the disease progresses, complications like intestinal obstruction, perforation, entero-enteric or enterocutaneous fistulisation, recurrent perianal sepsis, malabsorption and malignant transformation occur. Although lesser than UC, CD possesses a 5% risk of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) after a disease duration of 20 years [11]. Age at diagnosis, extent and severity of colitis, male gender and family history of sporadic CRC are also risk factors for malignancy [12]. Development of CRC with <8 years of colitis is cited to be rare, yet the patient in our study had had symptoms only for 5 years.

Treatment options in CD are guided by disease severity and individual response to treatment, with the aim of inducing and maintaining remission. Mild disease requires agents like 5-ASA and derivatives while moderate disease requires systemic steroids. Long course antibiotics are needed to treat flares. The use of immunomodulators and biological agents like TNF inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of severe CD [13]. Newer agents like anti integrins and anti-IL 12/23 agents are being used in treatment failure or resistant cases [14]. Specific problems like nutritional deficiencies, extraintestinal manifestations, enterocutaneous fistula and infections must be addressed accordingly.

Surgical management in CD is not curative but is essential to overcome specific complications. The recurrence rate following surgery is as high as 40% [15]. This precludes surgery for mild disease. Disease location and symptoms dictate the terms for surgery. The usual indications are disease refractory to medical treatment, intractable bleeding, strictures causing obstruction, free perforation and malignancy [12]. Segmental resections are carried out for recurrent, localized strictures. In our study, both case 1 who had multiple ileal perforations and case 4 who had an intestinal obstruction with enterocutaneous fistula, underwent segmental resections. Patients with disease confined to appendix benefit from appendicectomy but postoperative fistulization might occur. The two patients who presented with appendicitis (cases 2 and 3) in our study responded well to appendicectomy. Fistulas need surgical treatment under the cover of biologic agent therapy [16]. Simple low-lying perianal fistula is treated by fistulotomy or a draining seton whereas a complex fistula may need a combination of procedures like seton, fibrin glue instillation, extracellular matrix plugs, endorectal advancement flaps or a faecal diversion [8]. Our study patient underwent a seton placement and recovered with infliximab therapy. The scope for extensive surgeries like total proctocolectomy and subtotal colectomy in CD is limited since surgical treatment is aimed at managing only the worst affected segments.

CONCLUSION

CD can present in a diverse manner. With increasing incidence in the Eastern world, high suspicion is needed to diagnose CD masquerading with atypical presentations. Treatment for CD must be tailored on individual basis. Although elective surgery must be reserved only for refractory cases, many patients benefit from surgery as an emergency measure to handle complications. A multi-disciplinary approach combining surgery, when needed, along with medical and nutritional therapy will go a long way in improving the quality of life in patients with CD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the valuable assistance provided by Prof S.R.Dhamotharan in case selection for this study. We thank Dr Jeremiah Stanley for his inputs in manuscript preparation.

PATIENTS’ CONSENT

We have the permission of the patients to report these cases and none of the photographs reveal the identity of the patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- 1. Veauthier B, Hornecker JR. Crohn’s disease: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2018;98:661–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;35:380–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2012;380:1590–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petagna L, Antonelli A, Ganini C, Bellato V, Campanelli M, Divizia A, et al. Pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease inflammation and recurrence. Biol Direct 2020;15:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gearry RB. IBD and environment: are there differences between East and West. Dig Dis 2016;34:84–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Assadsangabi A, Lobo AJ. Diagnosing and managing inflammatory bowel disease. Practitioner 2013;257:13, 2–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaoul R, Rimar Y, Toubi A, Mogilner J, Polak R, Jaffe M. Crohn’s disease and recurrent appendicitis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:6891–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pogacnik JS, Salgado G. Perianal Crohn’s disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2019;32:377–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Louis E, Collard A, Oger AF, Degroote E, El Yafi AN, FA, Belaiche J.. Behaviour of Crohn’s disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut 2001;49:777–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arora U, Kedia S, Garg P, Bopanna S, Jain S, Yadav DP, et al. Colonic Crohn’s disease is associated with less aggressive disease course than ileal or ileocolonic disease. Dig Dis Sci 2018;63:1592–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dulai PS, Sandborn WJ, Gupta S. Colorectal cancer and dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of disease epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2016;9:887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gajendran M, Loganathan P, Catinella AP, Hashash JG. A comprehensive review and update on Crohn’s disease. Dis Mon 2018;64:20–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cheifetz AS. Management of active Crohn disease. JAMA 2013;309:2150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lémann M. Treatment of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. Bull Acad Natl Med 2007;191:1125–41discussion 1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiarello MM, Cariati M, Brisinda G. Colonic Crohn’s disease - decision is more important than incision: a surgical dilemma. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021;13:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gómez-Senent S, Barreiro-de-Acosta M, García-Sánchez V. Enterocutaneous fistulas and Crohn’s disease: clinical characteristics and response to treatment. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2013;105:3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]