Abstract

Background

To achieve early reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), proper and prompt patient transportation and activation of the catheterization laboratory are required. We investigated the efficacy of prehospital 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) acquisition and destination hospital notification in patients with STEMI.

Methods and Results

This is a systematic review of observational studies. We searched the PubMed database from inception to March 2020. Two reviewers independently performed literature selection. The critical outcome was short-term mortality. The important outcome was door-to-balloon (D2B) time. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence. For the critical outcome, 14 studies with 29,365 patients were included in the meta-analysis. Short-term mortality was significantly lower in the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification than in the control group (odds ratio 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.61–0.85; P<0.0001). For the important outcome, 10 studies with 2,947 patients were included in the meta-analysis. D2B time was significantly shorter in the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification than in the control group (mean difference −26.24; 95% CI −33.46, −19.02; P<0.0001).

Conclusions

Prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification is associated with lower short-term mortality and shorter D2B time than no ECG acquisition or no notification among patients with suspected STEMI outside of a hospital.

Key Words: Door-to-balloon time, Short-term mortality, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a significant public health problem in industrialized countries. The target duration from onset to reperfusion therapy in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is ≤120 min, and ≤90 min from first medical contact to reperfusion therapy.1–3 To achieve these targets, proper and prompt patient transportation and activation of the catheterization laboratory are required.

Several lines of evidence suggest that obtaining a prehospital 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and notifying the destination hospital help reduce mortality and door-to-balloon (D2B) time compared with no prehospital ECG in patients with STEMI.4–9 However, a prehospital 12-lead ECG is not currently widely available in Japan. Recently, several small observational studies of prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition in patients with ACS were conducted in Japan.10–12 To promote acquisition of a prehospital 12-lead ECG in Japan, we believe that more high-quality evidence from Japan is required. Therefore, we performed a systematic review investigating the impact of prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification on early mortality and D2B time in patients with suspected STEMI that included Japanese studies.

Methods

This systematic review was based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention, version 5.1.011 (https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/). The results are reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement.13,14

The systematic review team was organized by the Japan Resuscitation Council (JRC) Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) Task Force, which was established for the 2020 JRC guidelines. The Task Force were organized by the Japan Circulation Society, the Japanese Association of Acute Medicine, and the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. The JRC ACS Task Force posed the clinically relevant question to be evaluated with this systematic review.

Search Strategy and Data Sources

To guide the systematic review, the research question was posed using the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design and Time frame (PICOST) format as follows: P (patients), adult patients with suspected STEMI that occurred outside of a hospital; I (intervention), prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification; C (Comparator), no ECG acquisition or no notification; O (outcomes), critical outcome, defined as short-term mortality (30-day mortality or in-hospital mortality) from any cause, and important outcome, defined as D2B time; S (study design), randomized control trials (RCTs) or observational studies; T (time frame), all studies published before March 31, 2020.

A systematic search was conducted of the PubMed database for reports published from inception to March 31, 2020. A manual search was also performed to identify additional literature. We searched for full-text manuscripts of human studies published before March 31, 2020. We used a combination of key terms and established a full search strategy (Supplementary Appendix).

Study Selection

Two reviewers (T.N. and K.H.) independently screened titles and abstracts (first screening). Next, the same 2 reviewers independently assessed the full-text reports of potentially eligible studies for inclusion (second screening). The 2 reviewers achieved consensus on literature selection. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (H.N.). Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) prehospital ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification was used as an intervention; (2) comparison to no prehospital ECG acquisition or no notification was performed; and (3) outcomes were defined as mortality or D2B time. Pilot or single-arm studies and studies with irretrievable full-text reports were excluded. We did not restrict our analysis by country. However, we only included studies involving human subjects.

Assessment of the Risk of Bias

Two experienced reviewers (T.N. and K.H.) independently assessed the risk of bias of all included studies according to the Risk of Bias Assessment tool of Review Manager, version 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Studies were categorized as having a low, unclear, or high risk of bias in each element. The risk of bias for each element was considered high when bias was present and likely to affect outcomes and low when bias was not present or present but unlikely to affect outcomes.

Data Synthesis, Analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager, version 5.3. For each outcome, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a random-effects model. Statistical heterogeneity was determined based on I2 values, which were interpreted as follows: 0–40%, may not be important; 30–60%, moderate heterogeneity; 50–90%, substantial heterogeneity; and 75–100%, considerable heterogeneity.15 A funnel plot was constructed to assess the potential for publication bias.16

Assessment of Certainty of the Evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of the available evidence.17,18 The certainty of the evidence was assessed as high, moderate, low, or very low after evaluating the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. We generated an evidence profile table generated using GRADEpro GDT (Evidence Prime, Hamilton, ON, Canada).

Results

Literature Search

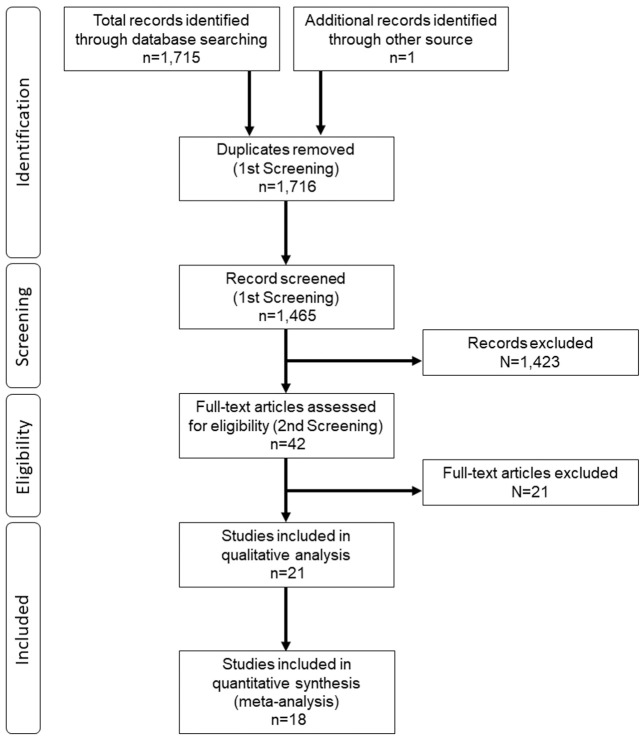

The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. In all, 1,716 citations were identified through the database and manual searches. There were no RCTs. After title and abstract assessment (first screening), 145 citations were eligible. After excluding 21 studies based on full-text assessment (second screening), 21 were included in qualitative analysis. Finally, 18 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Detailed characteristics of each study included are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarizing the evidence search and study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author | Year | Study design | Country | No. sites | No. patients | AgeA (years) | % MaleA | Mortality (%) | Mean D2BA (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital | 30 day | |||||||||

| Canto et al4 | 1997 | Prospective | US | 1,388 | 2,895 | 65 vs. 68 | 69 vs. 59 | 8.5 | Median only | |

| Dhruva et al5 | 2007 | Prospective | US | 1 | 49 | 54 vs. 56 | 75 vs. 66 | 80 vs. 146 | ||

| Brown et al6 | 2008 | Prospective | US | 1 | 48 | 57 vs. 62 | 80 vs. 71 | 6.3 | 73 vs. 130 | |

| Diercks et al7 | 2009 | Prospective | US | NCDR | 7,098 | 61 vs. 62 | 68 vs. 65 | 8.7 | Median only | |

| Rao et al8 | 2010 | Prospective | US | 3 | 349 | 60 vs. 60 | 74 vs. 69 | 1.4 | 60 vs. 91 | |

| Martinoni et al9 | 2011 | Prospective | Italia | Multicenter | 1,529 | 62 vs. 63 | 77 vs. 75 | 7.0 | Median only | |

| Camp-Rogers et al30 | 2011 | Prospective | US | 1 | 53 | 58 vs. 55 | 62 vs. 71 | 49 vs. 67 | ||

| Ong et al24 | 2013 | Prospective | Singapore | 6 | 283 | 55 vs. 56 | 94 vs. 89 | 3.2 | ||

| Horvath et al21 | 2012 | Prospective | US | 1 | 188 | 64 vs. 67 | 71 vs. 65 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 44 vs. 57 |

| Cone et al26 | 2013 | Prospective | US | 1 | 85 | 61 vs. 67 | 68 vs. 62 | 0 | 37 vs. 87 | |

| Papai et al19 | 2014 | Prospective | Hungary | 1 | 775 | 60 vs. 62 | 67 vs. 67 | 6.3 | 43 vs. 64 | |

| Quinn et al20 | 2014 | Prospective | UK | 228 | 14,063 | 71 vs. 74 | 67 vs. 60 | 6.5 | 11.0 | |

| Savage et al22 | 2014 | Prospective | Australia | 1 | 281 | 62 vs. 61 | 84 vs. 80 | 4.3 | 40 vs. 76 | |

| Squire et al25 | 2014 | Retrospective | US | 73 | 1,145 | 64 vs. 64 | 67 vs. 68 | 7.4 | 60 vs. 73 | |

| Marino et al23 | 2016 | Prospective | Brazil | 3 | 357 | 62 vs. 62 | 70 vs. 69 | 18.5 | 203 vs. 326 | |

| Kawakami et al10 | 2016 | Prospective | Japan | 1 | 162 | 37 vs. 68 | 84 vs. 97 | 1.2 | 0.6 | Median only |

| Kobayashi et al11 | 2016 | Retrospective | Japan | 1 | 112 | 61 vs. 56 | 84 vs. 84 | 5.5 | Median only | |

| Yufu et al12 | 2019 | Prospective | Japan | 1 | 46 | 71 vs. 66 | 71 vs. 72 | 70 vs. 96 | ||

AValues are shown for the intervention group vs. control group. All studies were observational. D2B time, door-to-balloon time; NCDR, National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

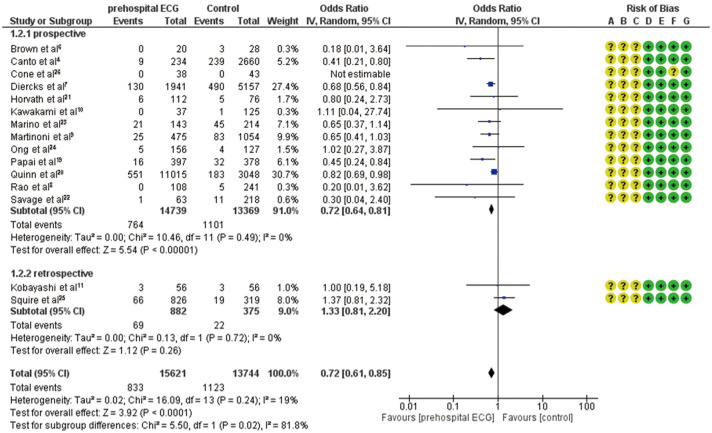

Critical Outcomes

For the critical outcome of short-term mortality from any cause, 15 observational studies with 29,365 patients were identified. The forest plot of the critical outcome with the risk of bias is shown in Figure 2. Among 29,365 patients, 833 of 15,621 patients (5.3%) in the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and hospital notification died, compared with 1,123 of 13,744 patients (8.2%) in the control group. Short-term mortality was significantly lower in the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification than in the control group (OR 0.72; 95% CI 0.61–0.85; P<0.0001). There was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2=19%). This set of 15 observational studies had low likelihood of publication bias; the funnel plot had a symmetric distribution (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing the odds ratios for the critical outcome of short-term mortality in patients with prehospital 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) acquisition and hospital notification vs. controls. The risk of bias is listed as follows: A, random sequence generation (selection bias); B, allocation concealment (selection bias); C, blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); D, blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); E, incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); F, selective reporting (reporting bias); and G, other bias. Studies were categorized as having a low (green), unclear (yellow), or high (red) risk of bias in each element. CI, confidence interval; ECG, electrocardiogram; IV, interval variable.

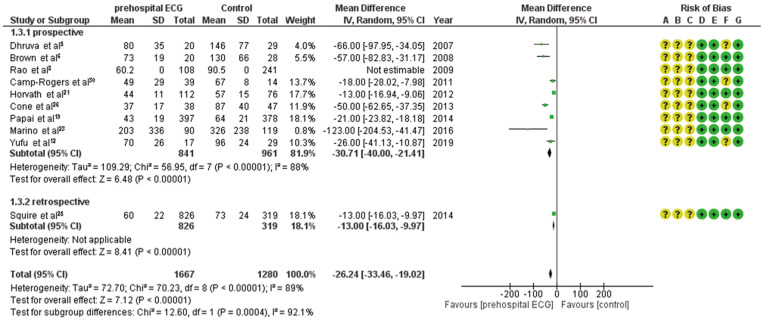

Important Outcomes

For the important outcome of D2B time, 16 observational studies were identified. However, 6 studies were excluded because D2B time was presented as a median and interquartile range. Ultimately, 10 studies with 2,947 patients were included in the meta-analysis. The forest plot of the important outcome with the risk of bias is shown in Figure 3. The group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification had significantly shorter D2B time than the control group (mean difference −26.24; 95% CI −33.46, −19.02; P<0.0001). Heterogeneity was suspected because I2 was high (89%). This set of 10 observational studies had publication bias; the funnel plot had an asymmetric distribution (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing the odds ratios for the important outcome of door-to-balloon time in patients with prehospital 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) acquisition and hospital notification vs. controls. The risk of bias is listed as follows: A, random sequence generation (selection bias); B, allocation concealment (selection bias); C, blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); D, blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); E, incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); F, selective reporting (reporting bias); and G, other bias. Studies were categorized as having a low (green), unclear (yellow), or high (red) risk of bias in each element. CI, confidence interval; ECG, electrocardiogram; IV, interval variable; SD, standard deviation.

Certainty of the Evidence

We assessed the certainty of the evidence for each outcome. We summarized our findings in the evidence profile table (Table 2). For the critical outcome, namely in-hospital mortality, the certainty of the evidence for the effect of prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification was rated as low because of the serious risk of bias. For the important outcome of D2B time, the certainty of the evidence for the effect of prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification was rated as very low because of the serious risk of bias and strong publication bias.

Table 2.

Evidence Profile

| No. studies | Study design |

Certainty assessment | Other considerations | No. patients | Effect | Certainty | Importance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Prehospital ECG |

No prehospital ECG |

Relative (95% CI) |

Absolute (95% CI) | |||||

| In-hospital outcome | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Observational studies |

Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect |

833/15,621 (5.3%) |

1,123/13,744 (8.2%) |

OR 0.72 (0.61 to 0.85) |

22 fewer per 1,000 (from 30 to 11 fewer per 1,000) |

⊕⊕○○ (Low) |

Critical |

| D2B time (mean) | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Observational studies |

Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Publication bias strongly suspected All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect |

1,667 | 1,280 | – | 26.24 lower (from 33.46 to 19.02 lower) |

⊕○○○ (Very low) |

Important |

CI, confidence interval; D2B time, door-to-balloon time; ECG, electrocardiogram; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This systematic review, which included studies from Japan, demonstrated that a prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification strategy is associated with significantly lower short-term mortality than no ECG acquisition or no notification among adult patients with suspected STEMI outside of a hospital. In addition, the prehospital 12-lead ECG strategy was associated with a significantly shorter D2B time.

To date, several small observational studies have reported that prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification may be associated with lower mortality,4,7,19,20 but this was not supported by other studies.6,8–11,21–26 There have been no RCTs evaluating this issue. The 2017 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines27 for STEMI included a Class IB recommendation to obtain a 12-lead ECG at the point of first medical contact based on only 2 studies.28,29 Our systematic review of 15 observational studies, which included studies conducted in Japan, showed that the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification had significantly lower odds of short-term outcomes than the control group. Our results are consistent with the recommendation in the ESC guidelines.27

For patients with STEMI, the JCS and ESC guidelines recommended primary percutaneous coronary intervention within 120 min of symptom onset and 90 min of first contact with medical personnel.1,27 All studies in this systematic review, including Japanese studies, reported a trend towards shorter D2B time in the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification than in the control group.5,6,8,12,19,21,23,25,26,30 Our systematic review showed that the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification had significantly shorter D2B time than the control group, by 26 min. Rapid initial response of the cardiac catheterization team and laboratory via hospital notification may have led to shorter D2B time, and possibly even lower mortality. Although prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition is not sufficiently widespread in Japan, dissemination of the prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification strategy should be considered based on our systematic review, which included studies conducted in Japan.

This study has several limitations. First, this systematic review only included observational studies, so the certainty of the evidence was low. However, we consider that our results should be taken seriously because short-term mortality is a critical outcome for patients with ACS. For D2B time, the studies that were included in the analysis had considerable heterogeneity. However, even in the studies that were excluded from the systematic review because only median D2B time was available, there was a trend towards shorter D2B time in the group with prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification (Supplementary Table). RCTs are needed to validate these findings in the future. Second, we extracted citations only from the PubMed database. Finally, there was nearly 20 years between the first (1997) and most recent (2019) studies, which may have resulted in differences in healthcare systems. Further RCTs are required to support our findings.

Conclusions

Prehospital 12-lead ECG acquisition and destination hospital notification are associated with lower short-term mortality than no ECG acquisition or no notification among patients with suspected STEMI outside of a hospital. In addition, the prehospital 12-lead ECG and destination hospital notification was associated with shorter D2B time.

Sources of Funding

Funding was provided by the Japan Resuscitation Council and the Japanese Circulation Society Emergency and Critical Care Committee.

Disclosures

T. Matoba is a member of Circulation Reports’ Editorial Team. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Contributors

T.N. contributed to the screening of articles, the data analysis, interpretation of the results, and preparation of the final report. K.H. contributed to the screening of articles and interpretation of the results. Y.T., M.K. and H.N. contributed to the formulation of the concept of the JRC ACS guidelines. Other members contributed to the final report. All authors approved the final version.

Supplementary Files

TABLE OF CONTENTS Supplementary Appendix. Combination of Key Terms and Established a Full Search Strategy Supplementary Table. Median Door to Balloon Time of the Studies Excluded From the Meta-Analysis for the Critical Outcome Supplementary Figure 1. Funnel plot of the studies included in the meta-analysis for the critical outcome Supplementary Figure 2. Funnel plot of the studies included in the meta-analysis of the important outcome

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Morio Aihara and the staff at the Japan Council for Quality Health Care (Minds Tokyo GRADE Center), for their help with the GRADE approach.

References

- 1. Kimura K, Kimura T, Ishihara M, Nakagawa Y, Nakao K, Miyauchi K, et al.. JCS 2018 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Circ J 2019; 83: 1085–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ogata S, Marume K, Nakai M, Kaichi R, Ishii M, Ikebe S, et al.. Incidence rate of acute coronary syndrome including acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and sudden cardiac death in Nobeoka City for the super-aged society of Japan. Circ J 2021; 85: 1722–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matoba T, Sakamoto K, Nakai M, Ichimura K, Mohri M, Tsujita Y, et al.. Institutional characteristics and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock in Japan: Analysis from the JROAD/JROAD-DPC database. Circ J 2021; 85: 1797–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Bowlby LJ, French WJ, Pearce DJ, Weaver WD.. The prehospital electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction: Is its full potential being realized? National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 29: 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dhruva VN, Abdelhadi SI, Anis A, Gluckman W, Hom D, Dougan W, et al.. ST-Segment Analysis Using Wireless Technology in Acute Myocardial Infarction (STAT-MI) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown JP, Mahmud E, Dunford JV, Ben-Yehuda O.. Effect of prehospital 12-lead electrocardiogram on activation of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and door-to-balloon time in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101: 158–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diercks DB, Kontos MC, Chen AY, Pollack CV Jr, Wiviott SD, Rumsfeld JS, et al.. Utilization and impact of pre-hospital electrocardiograms for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Data from the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53: 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rao A, Kardouh Y, Darda S, Desai D, Devireddy L, Lalonde T, et al.. Impact of the prehospital ECG on door-to-balloon time in ST elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2010; 75: 174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martinoni A, De Servi S, Boschetti E, Zanini R, Palmerini T, Politi A, et al.. Importance and limits of pre-hospital electrocardiogram in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary angioplasty. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011; 18: 526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kawakami S, Tahara Y, Noguchi T, Yagi N, Kataoka Y, Asaumi Y, et al.. Time to reperfusion in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with vs. without pre-hospital mobile telemedicine 12-lead electrocardiogram transmission. Circ J 2016; 80: 1624–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kobayashi A, Misumida N, Aoi S, Steinberg E, Kearney K, Fox JT, et al.. STEMI notification by EMS predicts shorter door-to-balloon time and smaller infarct size. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34: 1610–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yufu K, Shimomura T, Fujinami M, Nakashima T, Saito S, Ayabe R, et al.. Impact of mobile cloud electrocardiography system on door-to-balloon time in patients with acute coronary syndrome in Oita Prefecture. Circ Rep 2019; 1: 241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al.. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al.. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Botella J.. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods 2006; 11: 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sterne JA, Egger M.. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54: 1046–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Hill S, et al.. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: Critical appraisal of existing approaches. The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res 2004; 4: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mustafa RA, Santesso N, Brozek J, Akl EA, Walter SD, Norman G, et al.. The GRADE approach is reproducible in assessing the quality of evidence of quantitative evidence syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol 2013; 66: 736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Papai G, Racz I, Czuriga D, Szabo G, Edes IF, Edes I.. Transtelephonic electrocardiography in the management of patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Electrocardiol 2014; 47: 294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quinn T, Johnsen S, Gale CP, Snooks H, McLean S, Woollard M, et al.. Effects of prehospital 12-lead ECG on processes of care and mortality in acute coronary syndrome: A linked cohort study from the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project. Heart 2014; 100: 944–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horvath SA, Xu K, Nwanyanwu F, Chan R, Correa L, Nass N, et al.. Impact of the prehospital activation strategy in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous revascularization: A single center community hospital experience. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2012; 11: 186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Savage ML, Poon KK, Johnston EM, Raffel OC, Incani A, Bryant J, et al.. Pre-hospital ambulance notification and initiation of treatment of ST elevation myocardial infarction is associated with significant reduction in door-to-balloon time for primary PCI. Heart Lung Circ 2014; 23: 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marino BCA, Ribeiro ALP, Alkmim MB, Antunes AP, Boersma E, Marcolino MS.. Coordinated regional care of myocardial infarction in a rural area in Brazil: Minas Telecardio Project 2. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2016; 2: 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ong ME, Wong AS, Seet CM, Teo SG, Lim BL, Ong PJ, et al.. Nationwide improvement of door-to-balloon times in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction requiring primary percutaneous coronary intervention with out-of-hospital 12-lead ECG recording and transmission. Ann Emerg Med 2013; 61: 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Squire BT, Tamayo-Sarver JH, Rashi P, Koenig W, Niemann JT.. Effect of prehospital cardiac catheterization lab activation on door-to-balloon time, mortality, and false-positive activation. Prehosp Emerg Care 2014; 18: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cone DC, Lee CH, Van Gelder C.. EMS activation of the cardiac catheterization laboratory is associated with process improvements in the care of myocardial infarction patients. Prehosp Emerg Care 2013; 17: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al.. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting With ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2017; 39: 119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diercks DB, Peacock WF, Hiestand BC, Chen AY, Pollack CV Jr, Kirk JD, et al.. Frequency and consequences of recording an electrocardiogram >10 minutes after arrival in an emergency room in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (from the CRUSADE Initiative). Am J Cardiol 2006; 97: 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rokos IC, French WJ, Koenig WJ, Stratton SJ, Nighswonger B, Strunk B, et al.. Integration of pre-hospital electrocardiograms and ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks: Impact on door-to-balloon times across 10 independent regions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009; 2: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Camp-Rogers T, Dante S, Kontos MC, Roberts CS, Kreisa L, Kurz MC.. The impact of prehospital activation of the cardiac catheterization team on time to treatment for patients presenting with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med 2011; 29: 1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TABLE OF CONTENTS Supplementary Appendix. Combination of Key Terms and Established a Full Search Strategy Supplementary Table. Median Door to Balloon Time of the Studies Excluded From the Meta-Analysis for the Critical Outcome Supplementary Figure 1. Funnel plot of the studies included in the meta-analysis for the critical outcome Supplementary Figure 2. Funnel plot of the studies included in the meta-analysis of the important outcome