Abstract

Peptide self-assembly is an exciting and robust approach to create novel nanoscale materials for biomedical applications. However, the complex interplay between intra- and intermolecular interactions in peptide aggregation means that minor changes in peptide sequence can yield dramatic changes in supramolecular structure. Here, we use two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy to study a model amphiphilic peptide, KFE8, and its N-terminal acetylated counterpart, AcKFE8. Two-dimensional infrared spectra of isotope-labeled peptides reveal that AcKFE8 aggregates comprise two distinct β-sheet structures although KFE8 aggregates comprise only one of these structures. Using an excitonic Hamiltonian to simulate the vibrational spectra of model β-sheets, we determine that the spectra are consistent with antiparallel β-sheets with different strand alignments, specifically a two-residue shift in the register of the β-strands. These findings bring forth new insights into how N-terminal acetylation may subtly impact secondary structure, leading to larger effects on overall aggregate morphology. In addition, these results highlight the importance of understanding the residue-level structural differences that result from changes in peptide sequence to facilitate the rational design of peptide materials.

Significance

Self-assembling peptides have gained considerable interest for biomedical applications. However, the design of peptide materials is complicated by the fact that seemingly minor changes to the sequence of a peptide can result in the formation of distinct structures on both the molecular and supramolecular scales. Understanding the detailed residue-level structural differences is significantly more challenging yet vital to progressing the rational design of peptide materials. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy allows us to extract these structural details, even from aggregates containing multiple peptide arrangements. The findings in this study provide insight into how N-terminal acetylation may affect aggregate structure and demonstrate that this approach may prove widely useful in elucidating the structural variations in other self-assembled peptide systems.

Introduction

Self-assembling peptides are promising candidates for biomedical applications (1,2) in areas such as drug or vaccine delivery (3, 4, 5), tissue regeneration (6, 7, 8), and bioimaging, (9) due to their diverse functionalization and amphiphilicity (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Complex drug-delivery systems combine carrier molecules and targeting ligands with the desired drug, making tunable self-assembling peptides ideal candidates for these applications. However, it can be difficult to predict a final three-dimensional structure, much less functionality, based solely on a linear sequence of amino acids. Studies have shown that relatively small changes to the sequence of amino acids can dramatically alter the final self-assembled nanostructures (16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22). For example, Xu et al. reported a series of cationic peptide surfactants AmK (m = 3, 6, 9) that differ only in the repeat length of the alanine chain (23). These peptides self-assemble into three distinct nanostructures, ranging from flat nanosheets (A3K) to long nanofibers (A6K) to short nanorods (A9K). In another example, Cui et al. studied four constitutional isomers based on the tetrapeptide, V2E2, attached to an alkyl tail (24). They found that molecules with alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues (VEVE or EVEV) self-assemble into flat nanostructures although non-alternating isomers (VVEE and EEVV) form cylindrical nanofibers.

The KFE8 family of octapeptides, which comprises varying sequences of lysine, phenylalanine, and glutamic acid residues, is a classic example of the complexity in predicting sequence-structure relationships. Numerous studies have explored the effects of varying the patterning of the residues, changing the identity of the charged residues, introducing heterochiral blocks, or capping the termini (21,22,25, 26, 27, 28). Although all variants form extended β-sheet structures, their supramolecular morphologies exhibit varying lengths, widths, and degrees of helicity or twisting. One particularly interesting variant, AcKFE8 (COCH3-FKFEFKFE-NH2), forms a left-handed helical ribbon (25). Researchers have explored the potential of this unique chiral morphology for biomedical applications (2,8,9,29): in vivo, AcKFE8 exhibits an adjuvant effect when conjugated to other epitope-targeting domains (5,30). Since neither AcKFE8 nor the various conjugated substrates have shown adjuvant effects alone, current research suggests self-assembling peptides are the key in activation of immunological responses of the epitope species. The supramolecular morphology of AcKFE8 has been well characterized (22,25,31) using imaging techniques such as atomic force microscopy and transmission electron microscopy (TEM); however, the detailed arrangement of the peptides within the aggregates remains elusive. Although Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) and circular dichroism spectra indicate that the monomers are forming antiparallel β-sheets, the specific alignment of the strands has not been experimentally determined (25,32). Thus, it is unclear why AcKFE8 forms a unique left-handed helical ribbon although its non-acetylated analogue, KFE8 (NH2-FKFEFKFE-NH2), forms ribbons with a flat morphology. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations suggest that the AcKFE8 aggregates comprise two antiparallel β-sheet ribbons that stack to create a double helical morphology with a 20-nm pitch (25,26). From these studies were proposed two possible antiparallel β-sheet conformers for these helical ribbons, varying only in the register of the strands, but there exists no direct experimental evidence for the proposed structures. The unique morphology of AcKFE8 demonstrates immense potential for biomedical applications, making it imperative to understand precisely how acetylation affects the underlying organization of peptide monomers to create this left-handed helical ribbon and thus elucidate how other peptide sequences could be driven to adopt such a structure.

In this study, we use two-dimensional infrared (2D IR) spectroscopy and isotope labeling to extract structural details of aggregates of both AcKFE8 and its non-acetylated analogue, KFE8, for comparison. 2D IR spectroscopy has been used extensively to characterized the structure and aggregation dynamics of other peptides that form β-sheet-rich aggregates, including amyloid fibrils (33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46). When peptides form organized secondary structures, vibrational coupling between backbone amide I′ modes results in frequency shifts that can be used to analyze both secondary and tertiary structures (47, 48, 49, 50). These vibrational couplings are highly sensitive to both the distance and orientation between backbone residues. Thus, when β-sheet peptides are prepared with site-specific 13C18O labeling of individual backbone carbonyls, shifting the vibrational frequency of the labeled amide I′ mode by 55 cm−1 (51, 52, 53), we can determine the precise alignment of β-strands with single-residue resolution. 2D IR spectra of labeled AcKFE8 exhibit two isotope-labeled peaks compared with a single peak present in KFE8. Using transition dipole coupling (TDC) calculations of model β-sheets to simulate vibrational spectra, we demonstrate that these spectral features are consistent with one of the structures previously proposed by MD simulations. These results demonstrate that 2D IR spectroscopy is a powerful tool for studying protein self-assembly that provides molecular insights that would be difficult or impossible to obtain with traditional experimental techniques.

Materials and methods

Materials

All reagents were used as purchased, excluding modifications made to 1-13C-phenylalanine-OH, as described in the section on preparation of 13C18O-phenylalanine. Piperazine was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), potassium bisulfate (KHSO4), dimethylformamide, diethyl ether, acetone, acetonitrile, hydrochloric acid (12.1 N), acetic anhydride, 4-nitrobenzaldehyde, and methanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). N-9-fluoroenylmethoxycarbonyl (FMOC)-protected amino acids, Oxyma, and Rink Amide ProTide resin were purchased from CEM (Matthews, NC, USA). N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide was purchased from Oakwood Chemical (Estill, SC, USA). 1-13C-L-phenylalanine (99% enriched), 18O-H2O (98% enriched), and D2O (99% enriched) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA, USA). 2% uranyl acetate solution was purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA, USA). All other reagents were purchased from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA, USA).

Solid-phase peptide synthesis and purification

AcKFE8 and KFE8 were synthesized on a Liberty Blue microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM, Matthews, NC, USA) using standard FMOC solid-phase peptide synthesis with piperazine deprotection and diisopropylcarbodiimide/Oxyma activation (54). Rink Amide ProTide resin was used as the solid support to produce an amidated C-terminus in both peptides. After final deprotection, 10% acetic anhydride was used to acetylate the N-terminus of AcKFE8 before cleaving the peptide off the resin. A solution of 95% trifluoroacetic acid, 2.5% triisopropylsilane, and 2.5% deionized water was used to cleave the peptides from the resin and remove side-chain protecting groups. The resin was removed via filtration, followed by precipitation of the crude peptide with ice-cold diethyl ether. Crude peptide was dissolved in a 50/50 water/acetonitrile solution and purified via reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (Ultimate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a binary gradient of water (solvent A) and 100% acetonitrile (solvent B) with 0.045% HCl (v/v) as the counterion. The gradient was varied from 0% to 90% Solvent B over 40 min whereas ultraviolet-visible absorbance was monitored at 214 nm and 280 nm. AcKFE8 eluted around 15 min whereas KFE8 eluted around 18 min. Molecular weight and purity of both peptides were confirmed via electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (Orbitrap XL Penn, Thermo Fisher, WA, USA). Purified peptide was lyophilized (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) and stored at −20°C. Isotope-labeled peptides were synthesized and purified in the same manner, using 13C18O18O-phenylalanine-OH, preparation described below, at the Phe-5 position during solid-phase peptide synthesis.

Preparation of 13C18O18O-phenylalanine

FMOC protection was added to the 1-13C-phenylalanine using a 1:1:1 mol ratio of 1-13C-phenylalanine-OH, NaHCO3, and FMOC-succinimide, which was stirred overnight at room temperature in a 50:50 deionized water/acetone solution. The reaction was quenched with 2 M potassium sulfate to a pH of 2. The precipitated amino acid was vacuum filtered and washed sparingly with ice-cold deionized water. To introduce 18O labeling to the FMOC-protected amino acid, an acid-catalyzed 18O exchange was conducted under N2 atmosphere on a Schlenk line as previously reported (54). Briefly, 1 g of FMOC-1-13C-phenylalanine-OH was reacted with 1 g 18OH2 in 10 mL dioxane and 2 mL HCl in dioxane. The reaction was refluxed at 150°C for 6 h. Most of the solvent was removed under vacuum on the Schlenk line followed by lyophilization until completely dry. The process was repeated once to achieve 90% 18O labeling efficiency, as verified by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. The final labeled amino acid was washed with 10 mL of cold 3:1 (v/v) ethyl acetate:hexane solution. Most of the solution was removed via rotary evaporation. The amino acid was precipitated with cold 8:1 (v/v) hexane:ethyl acetate solution, vacuum filtered, and lyophilized to completely dry powder.

Sample preparation

All peptide samples were prepared using deuterated solvents to ensure the amide I′ mode was not obstructed by the strong water bending mode in 2D IR measurements. Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving the purified proteins in D2O. After determining the concentration of the stock solution by using the absorbance at phenylalanine at 280 nm (55), the peptide was lyophilized and redissolved in deuterated hexafluoroisopropanol (d-HFIP) (98% enriched) at a concentration of 1 mM. The d-HFIP solution was allowed to sit overnight before sonication for 4 h to ensure that the peptides were disaggregated, and the backbone amides were fully deuterated. Finally, d-HFIP was removed via lyophilization, and the dry powder stored at −80⁰C. In accordance with previously published studies, samples were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized protein in unbuffered D2O at a final pD of ∼3 (22,25,31). As AcKFE8 has been shown to form the left-handed helical aggregates at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 4 mM (31), a concentration of 1 mM was selected for these studies to achieve an acceptable signal-to-noise ratio in all experiments.

TEM

TEM micrographs were taken using a Tecnai Osiris transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operating at 200 kV. Ultrathin 400 copper mesh grids with formvar (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA) were dip coated in a 1 mM peptide solution to adhere peptide to grids. The grids were stained with 2 uranyl acetate solution and dried overnight. ImageJ, a free Java-based image processing program developed by the National Institutes of Health and Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation (University of Wisconsin), was used to process all TEM micrographs. Width and pitch measurements of all peptide ribbons were determined for 100 individual peptide ribbons to calculate averages and standard deviations with a 95% confidence interval.

Dynamic light scattering

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were performed on a Nano ZS zetasizer (Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK). Measurements were averaged over 300 scans and analyzed using a count size distribution. Malvern Analytical software calculates the average number of particles in solution within a size range based on the intensity of the light scattered within the size range using a size correlation function. This size distribution is plotted via a Gaussian function. The zetasizer utilizes an 800-nm continuous wave laser with a back-scatter detector at a 45° angle from samples. Ten centimeters pathlength polystyrene cuvettes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) were used to measure samples.

2D IR spectroscopy

A detailed description of 2D IR data collection and processing methods are described elsewhere (54). Briefly, 800-nm pulses (7 mJ, 1 kHz, 60 fs) were generated by a single box ultrafast amplifier (Solstice, SpectraPhysics, Milpitas, CA, USA). A 50/50 beamsplitter was used to direct half of the beam to pump an optical parametric amplifier with difference frequency generation (TOPAS-Prime, SpectraPhysics, Milpitas, CA, USA). The resulting mid-IR light (6,100 μm, 25 μJ, 1 kHz, 70 fs) was directed into the 2D IR spectrometer (2DQuick IR, PhaseTech Spectroscopy, Madison, WI, USA). 2D IR spectra were collected using a parallel (ZZZZ) beam polarization. The t1 time delay between pump pulses was scanned from 0 to 2.54 ps in 23.8-fs steps, although the t2 waiting time between pump and probe was held constant at 0 fs. The signal was directed into a monochromator (Princeton Instruments, Trinton, NJ) and dispersed onto a mercury cadmium telluride focal-plane array detector (PhaseTech Spectroscopy, Madison, WI, USA), which can achieve a spectral resolution of 2.1 cm−1. The data were collected using the QuickControl software provided by PhaseTech and processed using custom MATLAB scripts. Peptide samples were measured by placing 5 μL of peptide solution between two CaF2 windows (Crystran, Poole, Dorset, UK) separated by a 50-μm Teflon spacer.

Construction of model β-sheet aggregates

Flat antiparallel β-sheets were constructed from β-strands of eight residues each with an interstrand distance of 4.77 Å. To simulate different strand registers, alternating strands were shifted by integer multiples of 6.5 Å, which corresponds to the length of two residues in a β-sheet.

Methods for simulating the helical β-sheet ribbons were adapted from (26). Helical aggregates were constructed by taking flat β-sheets comprising 200 strands and positioning the first strand at the desired radius (inner radius = 22.5 Å; outer radius = 35.4 Å) along the y-axis. The β-sheet extended along the x-axis, with individual strands oriented parallel to the z-axis and shifted so that the middle of the strand was at z = 0. The β-sheet was then rotated about the y-axis by an angle such that the pitch of each helix would be 19.4 nm. The helix radius (r) and the pitch (h) are related by Eq. 1,

| (1) |

where is the pitch angle. To maintain a common pitch between the two helices, the y-axis rotation angle was 53.9° for the inner helix and 41.1° for the outer helix. Each strand in a β-sheet was then individually translated in the x-direction such that the middle of the strand had an x-coordinate of 0 followed by a rotation about the z-axis to produce the helical structure. The purpose of the translation before rotation was to obtain the desired radius after rotation (by construction, only the first strand in the β-sheet had the proper radius to the z-axis). The angles that were used to rotate about the z-axis were calculated to maintain 4.77 Å between consecutive strands. Each strand in the inner and outer helix was rotated by an additional −7.2° and −5.8°, respectively, relative to the previous strand in the helix.

The way the helix was constructed resulted in different hydrogen bond distances because successive strands were no longer parallel to one another. In a flat β-sheet with an interstrand distance of 4.77 Å, the hydrogen bond distances between adjacent strands were 1.8 Å. However, after the strands were rotated to create the helix, the hydrogen bond distances reached up to 2.3 Å. We employed a simple steepest descent energy minimization to better align the strands and alleviate the elongated hydrogen bond distances. The energy minimization was completed using GROMACS v.2020.3 with standard GROMOS 53a6 bond, angle, and dihedral parameters within each strand. The interstrand hydrogen bond distances were fixed using a Lennard-Jones interaction (σ = 0.255 nm; ε = 2.0 kJ/mol) between the amide nitrogen on one strand and the carbonyl oxygen on a neighboring strand. These parameters were chosen because they had minimal effect on the strand structure and hydrogen bond distances in the β-sheet structure. The energy minimization on the double helix decreased the maximum hydrogen bond distance to roughly 2.0 Å. Although this distance could be decreased further by increasing the ε Lennard-Jones parameter, we decided against this because larger ε parameters could lead to more significant changes to the overall structure of each strand and the purpose of the energy minimization was only used to slightly re-align the strands after the helix was constructed.

Simulation of vibrational spectra

FTIR and 2D IR spectra were calculated using COSMOSS, an open-source Matlab script available on GitHub that simulates vibrational spectra by creating an excitonic coupling Hamiltonian from structural input files (56). Flat aggregates were calculated using 20 strands, although helical aggregates were simulated using approximately 105 strands (approximately 50 strands per sheet, equivalent to one full helical turn). Unlabeled residues were assigned a local mode frequency of 1,650 cm−1 based on the experimental uncoupled amide I′ frequency, although 13C18O-labeled residues were redshifted by 55 cm−1 to 1,595 cm−1 (47). Coupling constants between residues were calculated according to a TDC model. However, this model overestimates coupling between adjacent, covalently bound residues, so nearest neighbor couplings were set to a value of 0.8 cm−1, which was derived from quantum mechanical calculations (53,57). To account for sources of environmental disorder, such as hydrogen bonding between the amide groups and water (58), the local mode frequencies were varied randomly around the assigned values using a Gaussian distribution with a full width at half maximum of 10 cm−1 (40). Simulated spectra were generated by averaging over 100 samples. The calculated spectra exhibited a consistent 12–16 cm−1 red shift of both the unlabeled and labeled amide I′ modes compared with experimental spectra, suggesting that our calculations consistently predict stronger vibrational couplings than we observe experimentally. This is not surprising, as the calculations are performed on ideal β-sheets models with no structural disorder. Real peptide aggregates likely exhibit some amount of structural disorder that alters the distance and angles between vibrational modes. Such structural variations would change the coupling strengths between residues, an effect that is not accounted for in our calculations (53). We have applied a constant 14 cm−1 blue shift to the calculated spectra to allow for more straightforward comparison with experiments.

Results and discussion

Although the size and supramolecular morphology of AcKFE8 aggregates have been reported previously (22,25,31), KFE8 has yet to be investigated under similar conditions. The difference in supramolecular structure during and after aggregation is immediately apparent when imaged with TEM (Fig. 1). In bright-field TEM, regions of higher density appear darker than regions of lower density. Thus, the regions of alternating light and dark contrasts along the length of the aggregated AcKFE8 ribbons (Fig. 1 A) indicate periodic changes in thickness, a clear indication of rotation. The use of light contrasts in TEM micrographs has been used previously as an accurate means to measure protein periodicity (59, 60, 61). The AcKFE8 twisted ribbons were determined to have widths of 15.7 ± 5.4 nm (Fig. 1 B, solid line) and pitches of 14.5 ± 0.5 nm. In contrast, the non-acetylated variant self-assembled to form narrow, flat peptide ribbons with widths of 8 ± 1.3 nm (Fig. 1, C and D, solid line), with no change in contrast along the length of the aggregates. The flat ribbons also showed a tendency to stack and aggregate into larger ribbon bundles that can reach over 100 nm in width, although helical ribbons remain separate in solution. These aggregate structures were found to persist for at least 1 week after initial aggregation (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

TEM micrographs of final morphology of AcKFE8 (A) and KFE8 (C) after 24 h aggregation. White scale bars are equal to 100 nm. Size distribution of peptide ribbon widths comparing measurements from DLS (dotted dashed line) and TEM micrographs above (solid lines) of AcKFE8 (B) and KFE8 (D) after 24 h aggregation.

Previous studies have demonstrated that DLS is capable of detecting protein aggregates before they are clearly visible by electron microscopy (62). Therefore, to better understand the evolution of AcKFE8 and KFE8 aggregates, we used DLS to track the hydrodynamic radius of the protein particles at discrete timepoints throughout a 24-h aggregation window (63). DLS analysis generally assumes that all particles in the scattering volume can be approximated as spheres. Clearly, this is not the case for the ribbon aggregates observed via TEM. However, DLS studies of amyloid protein fibers commonly approximate the fibers as cylinders, in which case the effective hydrodynamic radius calculated from DLS can be interpreted in terms of the fibers’ width (64, 65, 66). The fiber lengths are not reported in these measurements, as they exceed the limit of detection for DLS. As one would expect, the hydrodynamic radii of the peptide ribbons after 24 h of aggregation are larger than the mean widths measured by TEM (Fig. 1, B and D). The general trend still holds, however, as the AcKFE8 ribbons are wider and have a broader distribution than those formed by KFE8. DLS measurements from earlier time points showed no significant variation from the measurements at 24 h; thus, we conclude that the β-sheet ribbons form rapidly (in less than 5 min after initiating aggregation) and their supramolecular morphology remains unchanged, even when the samples were rechecked after a week of aggregation. Although TEM and DLS reveal distinct differences in the size and supramolecular morphology of the peptide aggregates, they do not possess sufficient structural resolution to indicate why N-terminal acetylation causes such dramatic changes in the aggregate structures.

To determine the residue-level structural differences that underlie the dramatically different supramolecular morphologies of AcKFE8 and KFE8, we collected 2D IR spectra of both peptides at three time points during aggregation: 5 min, 6 h, and 24 h. Fig. 2 shows the 2D IR spectra for each peptide variant after 24 h. In these spectra, peaks appear in pairs along the vertical pump axis; within each pair, the blue peak represents the fundamental vibrational transition and the yellow peaks represents the overtone vibrational transition. Both AcKFE8 (Fig. 2 A) and KFE8 (Fig. 2 B) exhibit strong amide I′ peak pairs at a probe frequency of 1,622 cm−1. This vibrational frequency is characteristic of highly ordered β-sheet structures (47,50) and is present immediately after self-assembly is initiated (Fig. S2). In soluble monomeric proteins that adopt β-sheet structures, the frequency of the amide I′ mode tends to correlate directly with the number of β-strands: as the number of strands increases, the amide I′ mode is further red shifted due to increasing delocalization of the vibration across the β-strands (67). For large, β-sheet-rich protein aggregates, however, the β-sheets are sufficiently extensive that the frequency shift appears to reach an asymptotic limit. Instead, the precise amide I′ frequency of these aggregates is determined by a variety of structural factors that affect vibrational coupling strengths, including interstrand spacings and the relative orientations of the amide I′ groups (44). The nearly identical 2D IR spectra in Fig. 2, A and B suggest that residues in AcKFE8 and KFE8 experience, on average, nearly identical vibrational couplings and thus must adopt very similar β-sheet structures.

Figure 2.

2D IR contour maps of AcKFE8 (A) and KFE8 (B) with nodal slope line (black line). Inverse nodal slope regression (C) of AcKFE8 (blue line) and KFE8 (red line) over 24 h aggregation is shown. Error bars for each time point represent the standard deviation over three measurements. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although the vibrational frequencies were identical for both peptides and remain constant over 24 h of aggregation, lineshape analysis revealed slight differences between variants. Here, we use inverse slope, defined as the 1/slope of the nodal line between the fundamental and overtone peaks, to quantify the inhomogeneity of the 2D IR lineshapes. Inverse slope values can vary between 0 (for purely homogenous, round lineshapes) and 1 (for inhomogeneous lineshapes that are elongated along the diagonal). Samples rarely exhibit purely homogeneous or inhomogeneous lineshapes, and thus, the inverse slope serves as a measure of the ratio of inhomogeneous to homogenous contributions (68,69). The spectral lineshapes, which reflect the distribution of vibrational frequencies within the sample, are directly related to the structural distribution of the proteins (40,47). The inverse slope of both variants decreases over the course of 24 h (Fig. 2 C). As the frequency of the amide I′ vibrational mode does not change during this period, we attribute the increased lineshape homogeneity to a subtle annealing of the ribbon structures, resulting in increased structural homogeneity, rather than a significant change in the structure of the β-sheets (44). In addition, AcKFE8 exhibits a consistently higher inverse slope than KFE8, indicating a higher degree of inhomogeneity throughout the course of aggregation. Thus, although amide I′ frequencies suggest that AcKFE8 and KFE8 must adopt nearly identical β strand configurations, the lineshapes reveal that AcKFE8 monomers experience more variation around this “average” structure. This result agrees with the measured TEM and DLS distributions and indicates that AcKFE8 is more heterogeneous on both the molecular and supramolecular scale. The higher inverse slope could signal the presence of multiple, slightly different strand alignments, as suggested by MD simulations (25, 26, 27).

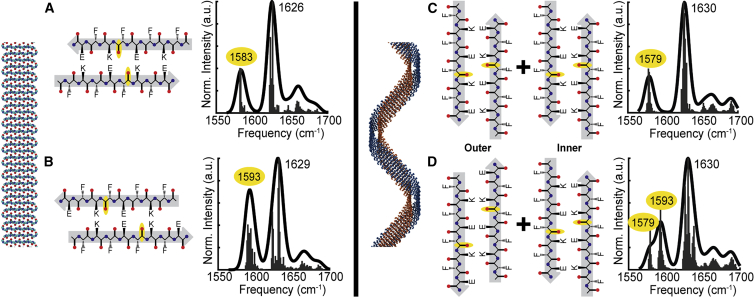

To test this hypothesis, we employ site-specific isotope labeling to probe the detailed alignment of the β-strands in each aggregate. Isotope labels are ideal structural probes, as they do not perturb peptide structure or dynamics. Introducing a 13C18O label into a backbone amide I′ group redshifts the frequency of that oscillator by 55 cm−1, isolating it from the other residues in the peptide (40,41,46,47). This allows the vibrational couplings between specific residues, which are exquisitely sensitive to both the distance and relative orientation of the amide I′ groups (50,70), to be measured directly. In one of the strand alignments proposed from MD simulations, the N-terminus is slightly exposed (Fig. 3 A), although in the second strand alignment, the register of the β-strands is shifted by two residues such that the C-terminus is exposed (Fig. 3 B). Comparing these strand alignments, we can see that residue F5 is well aligned across the strands in the N-exposed alignment but staggered between strands in the C-exposed alignment. Thus, we would expect residue F5 to experience strong coupling (+9.6 cm−1 according to TDC) in the N-exposed alignment, although coupling will be negligible (−0.2 cm−1 according to TDC) in the C-exposed alignment.

Figure 3.

Simulated antiparallel β-sheet structures and corresponding calculated FTIR spectra. Flat β-sheets were simulated from either N-terminal exposed (A) and C-terminal exposed (B) strand alignments. Left-handed double helical β-sheets were simulated using the N-exposed strand alignment for the inner β-sheet and either the N-exposed (C) or C-exposed (D) strand alignment for the outer β-sheet. The location of the 13C18O-labeled F5 residue is highlighted in yellow in each β-strand. The frequencies of the unlabeled and 13C18O-labeled amide I′ modes are labeled in the simulated spectra, with the isotope-labeled mode highlighted in yellow. To see this figure in color, go online.

To confirm the sensitivity of residue F5 to the two strand alignments, we simulate their vibrational spectra (56). The isotope-labeled mode appears at 1,583 cm−1 in the N-terminal strand alignment (Fig. 3 A), which is significantly red shifted compared with the 1,593 cm−1 peak calculated for the C-exposed strand alignment (Fig. 3 B). For comparison, we calculated an isotope-diluted spectrum in which only a single strand contained the 13C18O label at Phe-5 (Fig. 5 A); in this scenario, all coupling to the isotope-labeled amide I′ mode is eliminated and the labeled mode appears as a broad, weak feature at its native or local mode, frequency of 1,594 cm−1 (35,36). These results match our predictions that residue F5 is strongly coupled in the N-exposed alignment and virtually uncoupled in the C-exposed alignment. Thus, the coupling at residue F5 should serve as a sensitive reporter of the β strand alignment in both variants.

Figure 5.

Simulated and experimental spectra of isotope-diluted and doubly isotope-labeled peptides. Simulations of an antiparallel β-sheet with 10% isotope labeling (A) exhibit a fully uncoupled 13C18O peak at 1,594 cm−1, comparable to the experimental spectra collected for isotope diluted samples of both AcKFE8 (C) and KFE8 (D). Simulations of the mixed N-exposed and C-exposed helix doubly labeled with 13C18O at residues F3 and F5 (B) predict an intense coupled peak at 1,578 cm−1 and a weak uncoupled peak at 1,594 cm−1, which closely matches experimental spectra of double-labeled AcKFE8 (E). The locations of the 13C18O-labeled residues are highlighted in yellow in each β strand. The frequencies of the unlabeled and 13C18O-labeled amide I′ modes are labeled in the simulated spectra, with the isotope-labeled mode highlighted in yellow. Experimental pump slice amplitudes were fit to a sum of Gaussian functions, with the combined fit of the traces (dotted orange line) and fits for the unlabeled (purple) and 13C18O-labeled (green and blue) peaks plotted individually. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although these were the most favorable structures according to MD simulations (25,26), we tested other strand alignments to ensure that 2D IR spectra could distinguish between any possible structures. Two new structures were simulated with an additional two-residue shift in register toward either the N- or C-terminus; single-residue register shifts were neglected as they would eliminate the favorable pi-stacking interactions between phenylalanine residues. The calculated spectra exhibit significant disordered features, as increased staggering of the strands causes the termini to extend far past the core β-sheet structure (Fig. S4, A and B). The experimental 2D IR spectra show minimal contributions from disordered structures (Fig. 4, A and B); as such, these additional structures are discounted.

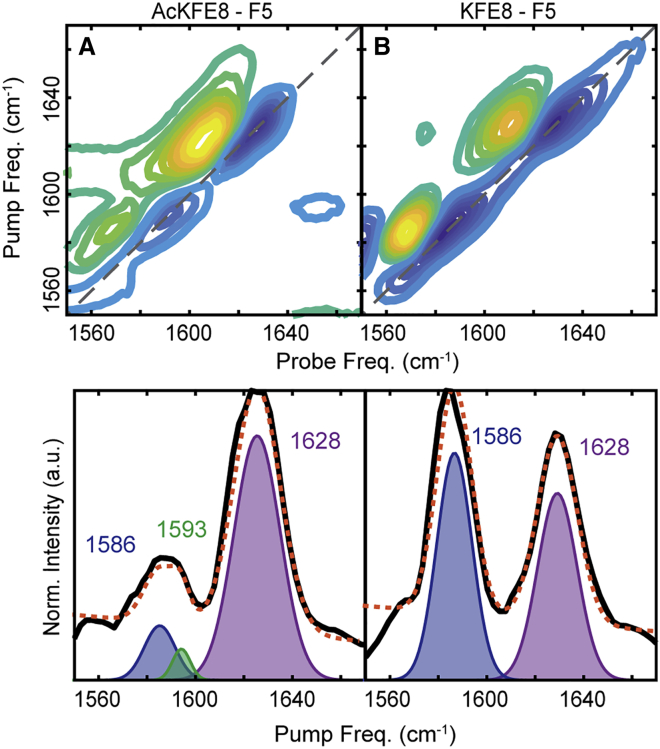

Figure 4.

2D IR spectra and pump slice amplitudes of single-isotope-labeled AcKFE8 (A) and KFE8 (B). The slices were fit to a sum of Gaussian functions, with the combined fit of the traces (dotted orange line) and fits for the unlabeled (purple) and 13C18O-labeled (green and blue) peaks plotted individually. To see this figure in color, go online.

To determine how helical twisting of the β-sheet aggregates would alter coupling, we simulated the vibrational spectra of the two helical β-sheet aggregates that have been proposed as likely structures for AcKFE8 (25,26). In both models, the inner β-sheet is formed with the N-exposed strand alignment; the models differ, however, in whether the outer β-sheet contains N-exposed (Fig. 3 C) or C-exposed (Fig. 3 D) strands. The latter model was initially proposed (25), but subsequent MD studies suggested that the former was more energetically favorable (26). Our calculations show that the double N-exposed helix (Fig. 3 C) produces spectral features that look nearly identical to those of a single, flat N-exposed β-sheet (Fig. 3 A). The mixed N-exposed and C-exposed helix (Fig. 3 D) produces spectral features that look like a sum of the N-exposed (Fig. 3 A) and C-exposed alignments (Fig. 3 B). Thus, we conclude that helical twisting of the β-sheets does not significantly alter coupling at residue F5.

Experimental 2D IR spectra of AcKFE8 and KFE8 labeled with 13C18O at residue F5 are shown in Fig. 4. Linear traces of the 2D IR spectra are calculated using the pump slice amplitude method (71) to reduce spectral artifacts and allow better comparison with calculated 1D IR spectra. Both variants exhibit an unlabeled amide I′ mode centered at 1,628 cm−1, which is 6 cm−1 higher than observed for the unlabeled species (Fig. 2, A and B). This shift can be attributed to isotope labeling of residue F5 disrupting the coupling of the β-sheets. Introduction of the heavier isotopes shift the frequency of the labeled mode by 55 cm−1, which is sufficient to eliminate coupling between labeled and unlabeled oscillators. As residue F5 is located in the center of the β-strands, the isotope label effectively sections the β-sheet into two smaller sheets (one with four residues per strand and one with three), which yield broader, higher frequency amide I′ peaks (36,53). KFE8 exhibits an isotope-labeled feature at a probe frequency of 1,586 cm−1 (Fig. 4 B), indicative of strong coupling at residue F5, which is consistent with an N-terminal exposed strand alignment (Fig. 3 A).

The experimental spectrum of AcKFE8 exhibits a broad feature in the isotope-labeled region between 1,580 and 1,600 cm−1 (Fig 4 A). This feature could not be fit to a single Gaussian peak but did fit well to a sum of two Gaussian peaks centered at 1,586 cm−1 and 1,593 cm−1. These features closely match our calculated spectra for the double helical structure containing both N-exposed and C-exposed strand alignments (Fig. 3 D), with the 1,586 cm−1 isotope mode corresponding to the N-exposed strand alignment of the inner β-sheet and the 1,593 cm−1 isotope mode corresponding to the C-exposed alignment of the outer β-sheet.

In addition to creating frequency shifts, vibrational coupling delocalizes the vibrational mode of multiple oscillators and thus redistributes the transition dipole distribution (72). Recent studies have demonstrated that transition dipole strengths are an even more sensitive measure of coupling between peptide residues than frequency shifts (73). Furthermore, these studies have shown that 2D IR is exquisitely sensitive to changes in transition dipole strength (72,73). Unfortunately, the weak signal strength of the isotope label in AcKFE8 makes it impossible to accurately quantify the transition dipole strength of this feature. Thus, we must restrict our analysis to qualitative comparison of the signal intensities. The significant difference in the labeled amide I′ peak intensity between AcKFE8 and KFE8 (Fig. 4) suggests that residue F5 experiences much stronger coupling in KFE8 than in the acetylated variant. This supports our structural assignments as residue F5 is strongly coupled across all strands in the N-exposed alignment. In contrast, at most half of the labeled F5 residues are strongly coupled in AcKFE8: the N-exposed inner helix would maintain coupling, although the C-exposed outer helix would exhibit minimal coupling. Furthermore, it has been shown that transition dipole strength is more sensitive than the overall mode frequency to subtle changes in coupling that arise from structural variations, such as interstrand spacings and dihedral angles (44). Thus, although both simulations and experiments exhibit the same coupled frequency for isotope-labeled F5, the dramatically reduced intensity of the coupled peak in AcKFE8 may reflect increased disruption of the coupling induced by the helical twist.

To confirm that the peaks observed in Fig. 4 truly arise from vibrational coupling between F5 residues, the AcKFE8 and KFE8 were prepared under isotope dilution conditions. If the isotope-labeled peaks shift back to the local mode frequency of 1,595 cm−1 (Fig. 5 A), we can attribute their red-shifted frequencies in pure samples to vibration coupling; if one or both peaks remain unchanged in frequency upon isotope dilution, we must consider that other effects, such as solvent environment or hydrogen bonding, are responsible for their low frequencies (35,46). For samples containing only 10% isotope-labeled peptides, the resulting 2D IR spectra are identical for both variants with a single, weak peak at 1,596 cm−1 (Fig. 5, C and D). Thus, we confirm that the two isotope-labeled modes in AcKFE8 arise from two different coupling constants between F5 residues: 10 cm−1 and 3 cm−1. These values align well with predicted coupling strengths within antiparallel β-sheet and with our calculations.

In addition, we synthesized another variant of AcKFE8 that is doubly labeled at residues F3 and F5 to determine whether coupling could be restored. Simulations of the mixed N-exposed and C-exposed double helix (Fig. 5 B) show with labeling at residues F3 and F5 show an extremely intense isotope peak at 1,578 cm−1, indicating strong coupling between the majority of the labeled residues. The correlates to coupling between residues F3 and F5 in the C-exposed strand alignment and between all F5 residues in the N-exposed strand alignment. There is also a much weaker peak at 1,594 cm−1, indicating the presence of uncoupled isotope labels. This is not surprising, as residue F3 does not align within the N-exposed strand alignment. In stark contrast, the intensities are reversed in the simulated spectrum of a double helix containing only N-exposed strands (Fig. S4 C): the uncoupled peak is more intense than the coupled peak, as residue F3 is never fully coupled. The experimental spectrum of double-labeled AcKFE8 (Fig. 5 E) also exhibits an extremely intense isotope peak at 1,574 cm−1, which confirms that coupling is re-established. When fitting the experimental spectrum, we found that including a small contribution from uncoupled isotope modes at 1,593 cm−1 did improve the overall goodness of fit (see comparison in Fig. S5) but could not be confidently assigned due to significant overlap with the intense coupled peak. Nevertheless, we can conclude that AcKFE8 adopts both N-exposed and C-exposed strand alignments whereas KFE8 adopts only the N-exposed alignment. Although this is in general agreement with the MD simulations (25,26), it contradicts their final conclusion that the purely N-exposed double helical structure was more likely. Instead, AcKFE8 adopts the structure determined to be less energetically favorable in the second study (26), a double helix comprising both C-exposed and N-exposed strand alignments.

Conclusion

N-terminal acetylation is a relatively minor variation in primary sequence that drastically changes morphology and functionality. Although the acetylated and non-acetylated variants generated nearly identical spectra in unlabeled 2D IR spectroscopy studies, site-specific isotope labeling revealed multiple β-sheet configurations within the seemingly homogenous aggregates formed by AcKFE8. In combination with TDC calculations of model antiparallel β-sheets, we show the unique twisted ribbon morphology in AcKFE8 arises from the formation of two β-sheets with different strand registers. In contrast, the unacetylated variant KFE8 only adopts a single β-strand alignment and forms flat ribbons. We hypothesize that KFE8 must maintain an N-exposed strand alignment to allow for solvent stabilization of the charged N-terminus. Acetylation eliminates this N-terminal charge, loosening the constraints on strand alignment and allowing either the N- or C-terminus to be exposed to solvent. These results increase our understanding of how changes in linear sequence directly affect peptide secondary structure. Our approach can be applied readily to the systematic study of a broad range of sequence variations, including those that occur naturally as post-translational modifications or the mutations associated with different phenotypes in amyloid disease (74,75). A better link between primary sequence and structure will aid both the understanding of human disease and the rational design of protein biomaterials using self-assembling peptides.

Author contributions

W.B.W. and L.E.B. designed the research; W.B.W. collected experimental data; C.J.T. constructed the helical aggregates; W.B.W. and L.E.B. calculated theoretical vibrational spectra; W.B.W. analyzed the data; and W.B.W. and L.E.B. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank James McBride at the Vanderbilt Institute for Nanoscale Engineering for assistance with electron microscopy. This project was supported by startup funding from Vanderbilt University.

Editor: Elsa Yan.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.03.003.

Supporting material

material

References

- 1.Lee S., Trinh T.H.T., et al. Ryou C. Self-assembling peptides and their application in the treatment of diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5850. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rad-Malekshahi M., Lempsink L., et al. Mastrobattista E. Biomedical applications of self-assembling peptides. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016;27:3–18. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eskandari S., Guerin T., et al. Stephenson R.J. Recent advances in self-assembled peptides: implications for targeted drug delivery and vaccine engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017;110–111:169–187. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Y., Norberg P.K., et al. Collier J.H. A supramolecular vaccine platform based on α-helical peptide nanofibers. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017;3:3128–3132. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudra J.S., Sun T., et al. Collier J.H. Modulating adaptive immune responses to peptide self-assemblies. ACS Nano. 2012;6:1557–1564. doi: 10.1021/nn204530r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller R.E., Grodzinsky A.J., et al. Frisbie D.D. Effect of self-assembling peptide, chondrogenic factors, and bone marrow-derived stromal cells on osteochondral repair. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010;18:1608–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bury M.I., Fuller N.J., et al. Sharma A.K. The promotion of functional urinary bladder regeneration using anti-inflammatory nanofibers. Biomaterials. 2014;35:9311–9321. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore A.N., Hartgerink J.D. Self-assembling multidomain peptide nanofibers for delivery of bioactive molecules and tissue regeneration. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:714–722. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni M., Zhuo S. Applications of self-assembling ultrashort peptides in bionanotechnology. RSC Adv. 2019;9:844–852. doi: 10.1039/C8RA07533F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera Estrada L.P., Champion J.A. Protein nanoparticles for therapeutic protein delivery. Biomater. Sci. 2015;3:787–799. doi: 10.1039/c5bm00052a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boekhoven J., Zha R.H., et al. Stupp S.I. Alginate–peptide amphiphile core–shell microparticles as a targeted drug delivery system. RSC Adv. 2015;5:8753–8756. doi: 10.1039/C4RA16593D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molino N.M., Wang S.-W.W. Caged protein nanoparticles for drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014;28:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartgerink J.D., Beniash E., Stupp S.L. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genové E., Shen C., et al. Semino C.E. The effect of functionalized self-assembling peptide scaffolds on human aortic endothelial cell function. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3341–3351. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowerman C.J., Nilsson B.L. Review self-assembly of amphipathic β-sheet peptides: insights and applications. Biopolymers. 2012;98:169–184. doi: 10.1002/bip.22058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Y., Qian Z., et al. Wei G. Amphiphilic peptides A 6 K and V 6 K Display distinct Oligomeric structures and self-assembly dynamics: a combined all-atom and Coarse-Grained simulation study. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:2940–2949. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourbo V., Matmor M., et al. Ashkenasy G. Self-assembly and self-replication of short amphiphilic β-sheet peptides. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2011;41:563–567. doi: 10.1007/s11084-011-9257-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Maltzahn G., Vauthey S., et al. Zhang S. Positively charged surfactant-like peptides self-assemble into nanostructures. Langmuir. 2003;19:4332–4337. doi: 10.1021/LA026526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vauthey S., Santoso S., et al. Zhang S. Molecular self-assembly of surfactant-like peptides to form nanotubes and nanovesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:5355–5360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072089599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altman M., Lee P., et al. Zhang S. Conformational behavior of ionic self-complementary peptides. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1095–1105. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.6.1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee N.R., Bowerman C.J., Nilsson B.L. Effects of varied sequence pattern on the self-assembly of amphipathic peptides. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:3267–3277. doi: 10.1021/bm400876s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clover T.M., O’neill C.L., et al. Rudra J.S. Self-assembly of block heterochiral peptides into helical Tapes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:19809–19813. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu H., Wang J.J., et al. Lu J.R. Hydrophobic-region-induced transitions in self-assembled peptide nanostructures. Langmuir. 2009;25:4115–4123. doi: 10.1021/la802499n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui H., Cheetham A.G., et al. Stupp S.I. Amino acid sequence in constitutionally isomeric tetrapeptide amphiphiles Dictates architecture of one-dimensional nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12461–12468. doi: 10.1021/ja507051w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marini D.M., Hwang W., et al. Kamm R.D. Left-handed helical ribbon intermediates in the self-assembly of a-sheet peptide. Nano Lett. 2002;2:295–299. doi: 10.1021/nl015697g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang W., Marini D.M., et al. Zhang S. Supramolecular structure of helical ribbons self-assembled from a β-sheet peptide. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:389–397. doi: 10.1063/1.1524618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou P., Deng L., et al. Xu H. Different nanostructures caused by competition of intra- and inter-β-sheet interactions in hierarchical self-assembly of short peptides. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;464:219–228. doi: 10.1016/J.JCIS.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee N.R., Bowerman C.J., Nilsson B.L. Sequence length determinants for self-assembly of amphipathic β-sheet peptides. Biopolymers. 2013;100:738–750. doi: 10.1002/bip.22248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan T., Yu X., et al. Sun L. Peptide self-assembled nanostructures for drug delivery applications. J. Nanomater. 2017;2017:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2017/4562474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudra J.S., Banasik B.N., Milligan G.N. A combined carrier-adjuvant system of peptide nanofibers and toll-like receptor agonists potentiates robust CD8+ T cell responses. Vaccine. 2018;36:438–441. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowerman C.J., Ryan D.M., et al. Nilsson B.L. The effect of increasing hydrophobicity on the self-assembly of amphipathic β-sheet peptides. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:1058. doi: 10.1039/b904439f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bibian M., Mangelschots J., et al. Ballet S. Rational design of a hexapeptide hydrogelator for controlled-release drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:759–765. doi: 10.1039/C4TB01294A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang C., Hochstrasser R.M. Two-dimensional infrared spectra of the 13 C 18 O isotopomers of alanine residues in an α-helix. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:18652–18663. doi: 10.1021/jp052525p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strasfeld D.B., Ling Y.L., et al. Zanni M.T. Tracking fiber formation in human islet amyloid polypeptide with automated 2D-IR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6698–6699. doi: 10.1021/ja801483n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shim S.-H., Gupta R., et al. Zanni M.T. Two-dimensional IR spectroscopy and isotope labeling defines the pathway of amyloid formation with residue-specific resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:6614–6619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805957106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y.S., Liu L.L., et al. Hochstrasser R.M. Two-dimensional infrared spectra of isotopically diluted amyloid fibrils from Aβ40. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:7720–7725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802993105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim Y.S., Hochstrasser R.M. Applications of 2D IR spectroscopy to peptides, proteins, and hydrogen-bond dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:8231–8251. doi: 10.1021/jp8113978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim Y.S., Liu L., et al. Hochstrasser R.M. 2D IR provides evidence for mobile water molecules in beta-amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:17751–17756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909888106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunkelberger E.B., Buchanan L.E., et al. Zanni M.T. Deamidation accelerates amyloid formation and alters amylin fiber structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12658–12667. doi: 10.1021/ja3039486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moran S.D., Woys A.M., et al. Zanni M.T. Two-dimensional IR spectroscopy and segmental 13C labeling reveals the domain structure of human γD-crystallin amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:3329–3334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117704109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchanan L.E., Dunkelberger E.B., et al. Zanni M.T. Mechanism of IAPP amyloid fibril formation involves an intermediate with a transient -sheet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:19285–19290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314481110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L., Buchanan L.E., et al. Skinner J.L. CRC Press; 2013. Ultrafast Infrared Vibrational Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buchanan L.E., Carr J.K., et al. Zanni M.T. Structural motif of polyglutamine amyloid fibrils discerned with mixed-isotope infrared spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2014;111:5796–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401587111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lomont J.P., Ostrander J.S., et al. Zanni M.T. Not all β-sheets are the same: amyloid infrared spectra, transition dipole strengths, and couplings investigated by 2D IR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:8935–8945. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b06826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lomont J.P., Rich K.L., et al. Zanni M.T. Spectroscopic signature for stable β-amyloid fibrils versus β-sheet-rich Oligomers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:144–153. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b10765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchanan L.E., Maj M., et al. Zanni M.T. Structural polymorphs suggest competing pathways for the formation of amyloid fibrils that Diverge from a common intermediate species. Biochemistry. 2018;57:6470–6478. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamm P., Zanni M. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2011. Concepts and Methods of 2D Infrared Spectroscopy. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh A., Ostrander J.S., Zanni M.T. Watching proteins wiggle: mapping structures with two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:10726–10759. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ganim Z., Hoi S.C., et al. Tokmakoff A. Amide I two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:432–441. doi: 10.1021/ar700188n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Demirdöven N., Cheatum C.M., et al. Tokmakoff A. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of antiparallel β-sheet secondary structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7981–7990. doi: 10.1021/ja049811j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buchanan L.E., Dunkelberger E.B., Zanni M.T. In: Protein Folding and Misfolding: Shining Light by Infrared Spectroscopy. Fabian H., Naumann D., editors. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2012. Examining amyloid structure and kinetics with 1D and 2D infrared spectroscopy and isotope labeling; pp. 217–237. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woys A.M., Almeida A.M., et al. Zanni M.T. Parallel β-sheet vibrational couplings revealed by 2D IR spectroscopy of an isotopically labeled macrocycle: quantitative benchmark for the interpretation of amyloid and protein infrared spectra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19118–19128. doi: 10.1021/ja3074962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strasfeld D.B., Ling Y.L., et al. Zanni M.T. Strategies for extracting structural information from 2D IR spectroscopy of amyloid: application to islet amyloid polypeptide. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:15679–15691. doi: 10.1021/jp9072203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Middleton C.T., Woys A.M., et al. Zanni M.T. Residue-specific structural kinetics of proteins through the union of isotope labeling, mid-IR pulse shaping, and coherent 2D IR spectroscopy. Methods. 2010;52:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roeters S.J., Iyer A., et al. Woutersen S. Evidence for intramolecular antiparallel beta-sheet structure in alpha-synuclein fibrils from a combination of two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep41051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ho J.-J., Ghosh A., et al. Zanni M.T. Heterogeneous amyloid β-sheet polymorphs identified on hydrogen bond promoting surfaces using 2D SFG spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2018;122:1270–1282. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b11934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hahn S., Kim S.S., et al. Cho M. Characteristic two-dimensional IR spectroscopic features of antiparallel and parallel β -sheet polypeptides: simulation studies. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:084905. doi: 10.1063/1.1997151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Myshakina N.S., Ahmed Z., Asher S.A. Dependence of amide vibrations on hydrogen bonding. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:11873–11877. doi: 10.1021/jp8057355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marini M., Limongi T., et al. Di Fabrizio E. Imaging and structural studies of DNA–protein complexes and membrane ion channels. Nanoscale. 2017;9:2768–2777. doi: 10.1039/C6NR07958J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beales P.A., Geerts N., et al. Vanderlick T.K. Reversible assembly of stacked membrane nanodiscs with reduced dimensionality and variable periodicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3335–3338. doi: 10.1021/ja311561d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen F., Strawn R., Xu Y. The predominant roles of the sequence periodicity in the self-assembly of collagen-mimetic mini-fibrils. Protein Sci. 2019;28:1640–1651. doi: 10.1002/pro.3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Georgalis Y., Starikov E.B., et al. Wanker E.E. Huntingtin aggregation monitored by dynamic light scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:6118–6121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aggeli A., Fytas G., et al. Boden N. Structure and dynamics of self-assembling β-sheet peptide Tapes by dynamic light scattering. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:378–388. doi: 10.1021/bm000080z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murphy R.M., Pallitto M.M. Probing the kinetics of β-amyloid self-association. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:109–122. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Streets A.M., Sourigues Y., et al. Quake S.R. Simultaneous measurement of amyloid fibril formation by dynamic light scattering and fluorescence reveals complex aggregation kinetics. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hill S.E., Robinson J., et al. Muschol M. Amyloid protofibrils of lysozyme nucleate and Grow via Oligomer fusion. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3781–3790. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zandomeneghi G., Krebs M.R.H., et al. Fändrich M. FTIR reveals structural differences between native β-sheet proteins and amyloid fibrils. Protein Sci. 2009;13:3314–3321. doi: 10.1110/ps.041024904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fenn E.E., Fayer M.D. Extracting 2D IR frequency-frequency correlation functions from two component systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2011;135:074502. doi: 10.1063/1.3625278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee M.W., Carr J.K., et al. Meuwly M. 2D IR spectra of cyanide in water investigated by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;139:054506. doi: 10.1063/1.4815969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paul C., Wang J., et al. Axelsen P.H. Vibrational coupling, isotopic editing, and β-sheet structure in a membrane-bound polypeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5843–5850. doi: 10.1021/ja038869f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valentine M.L., Al-Mualem Z.A., Baiz C.R. Pump slice amplitudes: a simple and robust method for Connecting two-dimensional infrared and fourier transform infrared spectra. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2021;125:6498–6504. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.1c04558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grechko M., Zanni M.T. Quantification of transition dipole strengths using 1D and 2D spectroscopy for the identification of molecular structures via exciton delocalization: application to α-helices. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;137:184202. doi: 10.1063/1.4764861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dunkelberger E.B., Grechko M., Zanni M.T. Transition dipoles from 1D and 2D infrared spectroscopy help reveal the secondary structures of proteins: application to amyloids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:14065–14075. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b07706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hubin E., Deroo S., et al. Sarroukh R. Two distinct β-sheet structures in Italian-mutant amyloid-beta fibrils: a potential link to different clinical phenotypes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015;72:4899–4913. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1983-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iyer A., Roeters S.J., et al. Subramaniam V. The impact of N-terminal acetylation of α-synuclein on phospholipid membrane binding and fibril structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:21110–21122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.726612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

material