Abstract

Postherpetic neuralgia is the most common complication of herpes zoster (shingles) in the immunocompetent host. Its mechanism is incompletely understood, but one postulate is that continuous replication of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in nerve tissues may be responsible for the pain. If this is so, antiviral treatment could be advantageous. To test this hypothesis, we performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 h [q8h]) for 14 days, followed by oral acyclovir (800 mg q6h) for 42 days in 10 subjects (median age, 71 years) who had experienced at least 6 months of severe pain (median duration of postherpetic neuralgia before enrollment, 3.2 years). Intensive and sparse pharmacokinetic sampling occurred during both dosing phases of the study. One- and two-compartment models were fitted to the oral and intravenous concentration-time data, respectively. The four men and four women assigned to acyclovir during either or both dosing phases tolerated it well. Pharmacokinetic results were similar to those previously reported in younger individuals. The mean oral clearance and elimination half-life following oral dosing were 1.47 liters/h/kg and 2.78 h, respectively. Total clearance and terminal half-life following intravenous administration were 0.16 liters/h/kg and 3.67 h, respectively. Only 1 of 10 participants reported definite improvement in the severity of postherpetic pain, and treatment had no effect on titers of humoral antibody to VZV. We concluded that 56 days of intravenous and oral acyclovir therapy were well tolerated but had little or no effect on the clinical course of postherpetic neuralgia.

Herpes zoster or shingles is the clinical expression of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. Postherpetic neuralgia—usually defined as pain lasting longer than 1 month after the rash heals—is the most common complication of shingles in immunocompetent hosts (12). Double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated that acyclovir given intravenously is effective therapy for acute herpes zoster in both normal and immunocompromised hosts (2, 3, 14). Rapid healing, resolution of acute pain, and a shortened period of virus shedding have been observed at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 8 h (q8h) for 5 to 7 days. Orally administered acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir have also been proven beneficial for shortening the course of acute herpes zoster in immunocompetent patients (1). Nevertheless, antiviral therapy for acute herpes zoster does not eliminate the risk of postherpetic neuralgia and no beneficial effect of any antiviral drug on established postherpetic neuralgia has been demonstrated (10). The possibility that postherpetic neuralgia is the result of continued replication of VZV in the sensory nerves (11) suggests that extended treatment with acyclovir could be beneficial and was the rationale for the performance of this trial. We selected the highest doses of intravenous and oral acyclovir used in clinical trials to provide the best opportunity to achieve inhibitory concentrations of the drug in nerve tissues. Because few data were available on the pharmacokinetics of high-dose intravenous and oral acyclovir in a relatively elderly population (median age, 71 years), multiple inpatient and outpatient blood samples were collected to measure acyclovir concentrations in plasma and perform pharmacokinetic analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was designed as a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted at the University of Minnesota. However, the first three subjects received open-label intravenous and oral acyclovir to ensure the safety of this regimen before proceeding to the double-blind phase. Institutional Review Board approval, approval by the Scientific Advisory Committee of the General Clinical Research Center, and informed consent from subjects prior to enrollment were required. Acyclovir sodium sterile powder for injection, oral acyclovir capsules, and matching placebo capsules were provided by Burroughs Wellcome (GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, N.C.).

Study population.

Participants were at least 18 years of age and had moderate or severe persistent postherpetic neuralgia in a unilateral thoracic or lumbar dermatome for at least 6 months that was associated with some degree of functional debility. Subjects were excluded for any of the following conditions: an immunocompromised state; a calculated creatinine clearance of <50 ml/min; inadequate contraceptive measures, if applicable; other antiherpes chemotherapy during the study or within 10 days prior to enrollment; oral, parenteral, or topical steroid therapy; or a history of allergy or intolerance to acyclovir.

Study design.

At enrollment, volunteers were randomized to receive a 1-h intravenous infusion of acyclovir (10 mg/kg) or a standard intravenous solution without acyclovir q8h for 14 days. On day 15, patients were instructed to take four capsules of either acyclovir (200 mg) or an identical placebo q6h for 42 days. Due to the lack of acyclovir pharmacokinetic data at the time of the study, the first three subjects enrolled received open-label intravenous and oral therapy. A medical history was taken and a physical examination was performed prior to study entry. The following laboratory tests were performed on days 5, 10, 15, 42, and 56: hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, white blood cell count with differential, red blood cell count, serum aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and routine urinalysis. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were measured daily during intravenous infusions. Humoral immunity to VZV was assessed on days 0, 7, 14, 28, and 56 by measuring complement-fixing or immunofluorescent-antibody titers. Participants were evaluated daily for pain response while in the General Clinical Research Center. During the outpatient phase and follow-up, pain and analgesic requirements were evaluated at weekly clinic visits or during telephone follow-up. The efficacy measurements in this study were severity of pain and VZV serology. Patients classified their pain as none, mild (pain that does not interfere with daily activities), moderate (pain that interferes with daily activities but does not cause sleeplessness), or severe (pain that causes sleeplessness). The use of analgesics was monitored.

Pharmacokinetic analyses.

Pharmacokinetic analyses were performed during the intravenous and oral segments of this study. Plasma samples were analyzed by a radioimmunoassay procedure specific for acyclovir at the University of Minnesota (coefficient of variation, <15%, limit of quantitation = 0.3 μM) (5). Following intravenous (10 mg/kg q8h) administration, peak and trough blood samples for the determination of acyclovir in plasma were collected after administration of the third dose on days 1, 5, 7, 10, and 14 from all patients. Peak concentration samples were drawn at the end of the infusion, and trough concentration samples were collected within 15 min prior to administration of the next dose. Three of the six subjects who received intravenous therapy also had samples collected prior to administration of the morning dose and at 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, and 6.5 h postdose on day 3. Following administration of oral acyclovir (800 mg q6h), plasma was collected just prior to administration of the first morning dose and 2, 4, and 6 h postdose on day 3. Peak (2 h) and trough (within 30 min prior to administration of the next dose) samples were scheduled to be collected weekly until completion of oral dosing.

The disposition of acyclovir following intravenous administration was characterized by using a linear two-compartment model with Bayesian parameter estimation. The absorption and disposition of acyclovir following oral administration were characterized by using a linear one-compartment model with a lag phase and Bayesian parameter estimation. Both models were implemented by using the ADAPT II, release 4, software package (6, 7). Intensive concentration-time data were used for modeling purposes. If these data were not available, then all peak and trough data were used for an individual patient. Maximum-likelihood parameter estimation was initially used; these results were then used to compute maximum a posteriori priors. Data were then reanalyzed by using Bayesian estimation. The a posteriori model parameters were similar to previously published data (8, 9). The parameters examined were the following: total body clearance (CLt), 0.2 liter/h/kg; terminal distribution volume (Vβ), 0.9 liter/kg; distributional clearance between the central and peripheral compartments (CLd), 0.14 liter/h/kg for intravenous administration; oral clearance (CL/F), 2.0 liters/h/kg; apparent distribution volume (V/F), 9.0 liters/kg; absorption rate constant (ka), 0.5 h−1 for oral administration. Output error was described by using a linear standard deviation variance model. Model discrimination was based on Akaike's information criterion (15) and least-squares regression.

RESULTS

Demographics.

This study was designed for 60 patients, but problems with accrual resulted in early closure. Five men and five women, 31 to 80 years of age (median age, 71 years) enrolled in this study from 13 September 1983 to 3 December 1984 (Table 1). Of the 10 subjects, 6 received intravenous acyclovir therapy, 7 received oral therapy, and 5 received both (Table 2). The median age of subjects for whom concentration-time data were available for pharmacokinetic analyses was 72.5 years; their estimated median creatinine clearance was 62.7 ml/min. The time between the acute shingles episode and study entry ranged from 8 months to 15.7 years, with a median of 3.0 years. The dermatomal location of the shingles was thoracic in nine patients and lumbar in one patient.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study volunteers

| Patient | Age (yrs) | Gendera | Time (yrs) since acute herpes zoster | Entry serum creatinine (mg/dl) | Calculated creatinine clearance (ml/min)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 | F | 3.8 | 0.8 | 68.1 |

| 2 | 73 | F | 3.8 | 0.8 | 57.3 |

| 3 | 67 | M | 2.8 | 1.1 | 74.7 |

| 4 | 77 | M | 0.7 | 0.9 | 68.1 |

| 5 | 31 | F | 0.8 | 0.8 | 102.3 |

| 6 | 68 | M | 3.6 | 0.9 | 97.8 |

| 7 | 62 | M | 15.7 | 1.1 | 82.7 |

| 8 | 72 | F | 1.1 | 1.0 | 50.6 |

| 9 | 80 | M | 3.2 | 1.0 | 53.3 |

| 10 | 75 | F | 1.9 | 0.8 | 43.2 |

| Median, mean (SD) | 70.5, 67.4 (13.8) | 3.0, 3.7 (4.4) | 0.9, 0.9 (0.1) | 68.1, 69.8 (19.8) |

F, female; M, male.

Determined by using the Cockcroft-Gault equation.

TABLE 2.

Clinical outcomes of patients treated with intravenous and oral acyclovir

| Patient no. | Treatment group (intravenous-oral) | Pain progression (study entry → study end) | Analgesics required | Subjective evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acyclovir-acyclovir | Moderate → moderate | Yes | No effect |

| 2 | Acyclovir-acyclovir | Severe → moderate | Yes | No effect |

| 3 | Acyclovir-acyclovir | Severe → severe | Yes | No effect |

| 4 | Placebo-placebo | Severe → severe | Yes | No effect |

| 5 | Placebo-acyclovir | Moderate → moderate | Yes | Variable |

| 6 | Acyclovir-placebo | Moderate → moderate | Yes | Variable |

| 7 | Acyclovir-acyclovir | Moderate → mild | No | Positive |

| 8 | Placebo-placebo | Moderate → mild | Yes | No effect |

| 9 | Acyclovir-acyclovir | Severe → severe | Yes | No effect |

| 10 | Placebo-acyclovir | Severe → severe | No | No effect |

Efficacy.

The first three participants received open-label intravenous and oral drug administration (in accordance with the protocol) to monitor safety and to obtain long-term pharmacokinetic data. Clinical outcomes following acyclovir treatment and/or placebo administration are described in Table 2. Severity of pain varied among subjects, and only two did not take analgesics. One subject (patient 7) had a positive clinical outcome with a consistent decrease in pain. He entered the study only 8 months after his episode of acute shingles and thus had a relatively brief history of postherpetic pain compared with the other participants. Therefore, no clinical benefit of acyclovir was established among this small number of volunteers.

Analysis of complement-fixing and immunofluorescent-antibody titers at enrollment and on completion of the study showed that seven subjects had a less-than-fourfold change in the titers. Three subjects had a fourfold change; two subjects had a fourfold increase in the immunofluorescent-antibody titer, and one subject had a fourfold decrease in the complement-fixing antibody titer. These data do not support any antiviral effect as reflected by humoral antibody titer changes.

Safety.

All 10 subjects were evaluated for adverse experiences and laboratory tests. No serious adverse drug experiences were reported. Three subjects experienced the following symptoms while receiving open-label intravenous acyclovir: subject 1, dry mouth and anorexia; subject 2, dizziness, lightheadedness, intermittent vertigo, anorexia, nausea, and gas pains; subject 3, thirst, dry mouth, and anorexia. One placebo recipient also reported thirst and dry mouth. One participant was undergoing treatment for presumed iron deficiency anemia after concurrent treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These symptoms were not attributed to the study compound. No abnormalities in renal or hepatic function were observed. One subject assigned to the placebo group during both phases had a hemoglobin level of 10.2 g/dl on enrollment, which increased to 12.7 g/dl at the end of the study. A second subject assigned to the acyclovir group during both study phases entered and completed the study with hemoglobin levels of 10.5 and 8.9 g/dl, respectively. Acyclovir may have contributed to this change in hemoglobin. The remaining subjects had no evidence of hematologic abnormalities before or during the trial. None of the abnormal values excluded subjects from study entry.

Pharmacokinetics.

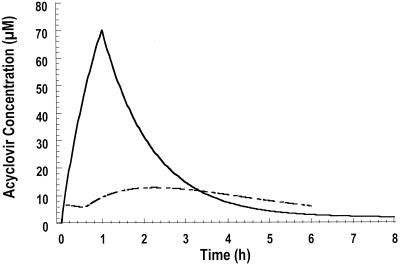

Acyclovir pharmacokinetic parameters following intravenous or oral administration are presented in Table 3. Acyclovir concentration-time data were well described by the one-compartment (oral) and two-compartment (intravenous) models. Figure 1 depicts acyclovir disposition in two subjects following oral and intravenous administration. Pharmacokinetic results were consistent with those previously derived in younger populations. Mean (±standard deviation) peak and trough acyclovir levels following intravenous administration were 66.2 ± 15.5 and 8.4 ± 1.8 μM, respectively. The highest acyclovir level observed in plasma was 120 μM at the end of an infusion. Nine of the 10 participants in this study were greater than 60 years old. All of the subjects had normal serum creatinine levels at enrollment; both serum creatinine and calculated creatinine clearances were not altered during the course of the study. In a previous study, the steady-state peak and trough levels were 91.9 ± 45.3 and 10.2 ± 6.2 μM following administration of a 10-mg/kg 1-h infusion (4). The lower mean peak value may be attributed to the slightly longer infusion times for acyclovir administration during this study. The highest mean acyclovir concentration following oral administration (9.5 ± 3.9 μM) was in the time range of 4.0 to 4.9 h, with an average time of 4.1 h. The average steady-state trough level was approximately 4.4 μM.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of acyclovir following intravenous and oral administrationa

| Parameter | Intravenous acyclovir (n = 6)

|

Oral acyclovir (n = 7)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLt (liters/h/kg) | Vβ (liters/kg) | CLd (liters/h/kg) | t1/2 (h) | CL/F (liters/h/kg) | V/F (liters/kg) | t1/2 (h) | |

| Mean | 0.16 | 0.89 | 0.15 | 3.67 | 1.47 | 5.54 | 2.78 |

| SD | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.12 | 1.85 | 0.47 | 2.43 | 1.38 |

| CV (%) | 20 | 67 | 79 | 50 | 32 | 44 | 49 |

CLt, total body clearance; CLd, distributional clearance between the central and peripheral compartments; Vβ, terminal distribution volume; t1/2, elimination half-life; CL/F, apparent clearance; V/F, apparent distribution volume; CV, coefficient of variation.

FIG. 1.

Representative acyclovir disposition following oral (800 mg q6h, dotted line) and intravenous (10 mg/kg q8h, solid line) administration.

DISCUSSION

Acyclovir does not appear to be useful for the treatment of established postherpetic neuralgia based on the findings from this small group of patients. One of the five patients who received both high-dose intravenous and oral acyclovir reported a clinical benefit, and this individual was the only one of 10 volunteers who reported a consistent improvement in the severity of pain. However, intravenous acyclovir (10 mg/kg q8h for 14 days) and/or oral acyclovir (800 mg q6h for 42 days) was well tolerated by this relatively elderly group of subjects with postherpetic neuralgia. Pharmacokinetic parameters derived from these subjects with normal renal function, whose median age was 71 years, were comparable to parameters found in younger individuals. In the five subjects who received both high-dose intravenous and oral acyclovir, no drug accumulation was observed. The acyclovir concentrations in the plasma of our subjects who received 2 weeks of intravenous acyclovir administration were comparable to historical data from younger persons with normal renal function. In contrast, acyclovir levels in plasma following chronic oral administration appeared to be higher than historical data, possibly indicating better oral absorption in our subjects.

Our study was designed to explain the effect of an antiviral drug on pain rather than viral replication. Because antiviral therapy does not appear to be a useful approach, current treatment of postherpetic neuralgia continues to require analgesics, such as the lidocaine patch, antidepressants such as nortriptyline, or the anticonvulsant gabapentin. Intensive intervention such as intrathecal administration of corticosteroids has even been tested (13). Although some progress has been made, therapies for the relief of pain following herpes zoster are urgently needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants P30-AI 27767-12 from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease and MO1 RR00400 from the National Institutes of Health Center Research Resources, by the Minnesota Medical Foundation, and by the International Center for Antiviral Research and Epidemiology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balfour H H., Jr Antiviral drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1255–1268. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balfour H H, Jr, Bean B, Laskin O L, Ambinder R F, Meyers J D, Wade J C, Zaia J A, Aeppli D, Kirk L E, Segreti A C, Keeney R E. Acyclovir halts progression of herpes zoster in immunocompromised patients. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1448–1453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bean B, Braun C, Balfour H H., Jr Acyclovir therapy for acute herpes zoster. Lancet. 1982;ii:118–121. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum M R, Liao S H T, de Miranda P. Overview of acyclovir pharmacokinetic disposition in adults and children. Am J Med. 1982;73(1A):186–192. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinnock B J, Vicary C A, Brundage D M, Balfour H H., Jr Serum is an acceptable specimen for measuring acyclovir levels. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1987;6:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(87)90117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Argenio D Z, Schumitzky A. A program package for simulation and parameter estimation in pharmacokinetic systems. Comp Programs Biomed. 1979;9:115–134. doi: 10.1016/0010-468x(79)90025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Argenio D Z, Schumitzky A. ADAPT II user's guide: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic systems analysis software. Los Angeles, Calif: Biomedical Simulations Resource; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Miranda P, Blum M R. Pharmacokinetics of acyclovir after intravenous and oral administration. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12(Suppl. B):29–37. doi: 10.1093/jac/12.suppl_b.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher C V, Chinnock B J, Chace B, Balfour H H., Jr Pharmacokinetics and safety of high-dose oral acyclovir for suppression of cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;44:158–163. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1988.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilden D H. Herpes zoster with postherpetic neuralgia—persisting pain and frustration. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:932–934. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilden D H, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B K, LaGuardia J J, Mahalingham R, Cohrs R J. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:635–645. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kost R G, Straus S E. Postherpetic neuralgia—pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:32–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607043350107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotani N, Kushikata T, Hashimoto H, Kimura F, Masatoshi M, Yodono M, Asai M, Matsuki A. Intrathecal methylprednisolone for intractable postherpetic neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1514–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepp D H, Dandliker P S, Meyers J D. Treatment of varicella-zoster virus infection in severely immunocompromised patients. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:208–212. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601233140404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaoka K, Nakagawa T, Uno T. Application of Akaike's information criterion (AIC) in the evaluation of linear pharmacokinetic equations. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1978;6:165–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01117450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]