Abstract

Critical gaps exist in our knowledge on how best to provide quality person-centered care to long-term care (LTC) home residents which is closely tied to not knowing what the ideal staff is complement in the home. A survey was created on staffing in LTC homes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to determine how the staff complement changed. Perspectives were garnered from researchers, clinicians, and policy experts in eight countries and the data provides a first approximation of staffing before and during the pandemic. Five broad categories of staff working in LTC homes were as follows: (1) those responsible for personal and support care, (2) nursing care, (3) medical care, (4) rehabilitation and recreational care, and (5) others. There is limited availability of data related to measuring staff complement in the home and those with similar roles had different titles making it difficult to compare between countries. Nevertheless, the survey results highlight that some categories of staff were either absent or deemed non-essential during the pandemic. We require standardized high-quality workforce data to design better decision-making tools for staffing and planning, which are in line with the complex care needs of the residents and prevent precarious work conditions for staff.

Keywords: long-term care homes, COVID-19, workforce, staff complement, common data elements

Introduction

There are critical gaps in our knowledge on how best to provide high-quality person-centered care to long-term care (LTC) home residents, given that they often live with high levels of frailty due to multiple chronic conditions; many are near the end of their life, and all have complex care needs. It is known that the LTC home workforce does not have optimal skills to meet all the care needs of individuals residing in these homes (Hamers, 2011; Koopmans et al., 2018) nor are there enough staff to do so (Kaasalainen et al., 2021; Boscart et al., 2018). Evidence exists that the LTC sector suffers from unsatisfactory labor conditions due to structural and institutional factors producing precarious working conditions for the staff (Fagertun, 2021; McGilton et al., 2020; Scales, 2021).

These realities were thrown into sharp focus during the severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (COVID-19) pandemic when there was a reduced workforce available to meet care needs, not only in numbers but also the range of healthcare staff available to provide services; this increased the risk of adverse outcomes for residents including the highest number of deaths in LTC homes globally (Ioannidis, 2020; Labrague et al., 2021; Lombardo et al., 2020). We need a greater understanding of who is working in LTC homes in order to develop high-quality workforce data elements that could be used globally to generate evidence to support workforce planning in the LTC home sector and contribute to enhancing the quality of care.

To highlight important observations related to who was in the house (LTC homes) during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers in eight countries identified categories of staff working in LTC homes and exploring changes that occurred during the pandemic. Long-term care may involve a wide range of personal, social, and medical services provided to those with difficulty performing activities of daily living due to functional and cognitive limitations. These services can be provided in a myriad location such as in private homes, adult day-care settings, assisted living facilities, and LTC or nursing homes (Zimmerman & Sloane, 2007). This paper focuses on LTC homes in eight countries that are institutional facilities that provide 24-hour personal and nursing care to those who cannot receive such care in their own homes due to insufficient social and healthcare supports. Specifically, the following three questions are addressed:

What categories of staff worked in LTC homes in eight countries before the COVID-19 pandemic?

What categories of staff worked in LTC homes in eight countries during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic?

What type of support and services were provided by different categories of staff during this period?

Methods

A consortium of international researchers from various countries established the WE-THRIVE (Worldwide Elements to Harmonize Research in Long-Term Care Living Environments) group with the aim to develop common data elements for LTC homes (Corazzini et al., 2019) and the “Workforce and Staffing” group took the lead to collect data on staffing trends in LTC homes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, the group created a survey that included the following specific items: type of staff and personnel worked, their titles in different regions, who worked before the pandemic, who continued to be present during the pandemic, type of support provided (such as virtual or in-person, and their frequency), and impact on resident care. Next, the survey was trialed by one researcher (KM), who completed it with an administrator and researcher actively involved in the LTC home sector. Based on the findings, the Workforce and Staffing group made minor changes to the survey before final implementation. The Workforce and Staffing group researchers completed the survey by consulting virtually with clinicians, experts, and researchers in their networks. These individuals had practical and/or administrative and research expertise related to LTC homes and many of whom were involved in advisory committees and health system leadership teams. Thus, they were able to provide a general overview LTC homes in their regions and not a specific one. These data were supplemented by published scientific and lay press documents and government statistics obtained by the Workforce and Staffing group researchers from their respective countries to provide a comprehensive response to survey questions and highlight their country specific trends. All the data were acquired between July and August 2021 with a focus on the first wave of the pandemic. The countries included: Canada, China, England, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. The current study is a first approximation of cross-national comparison of staffing trends in LTC homes in eight countries during an unprecedented event of the COVID-19 pandemic. The data was synthesized according to personnel type (or the closest equivalent in each country) that worked in the LTC homes to look for variation in staff composition between countries, specifically before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The work presented here is not an exhaustive review of what happened with staffing in LTC homes in each country during the pandemic, but an attempt to share insights about challenges and trends. Ethics approval was not required for this study.

Results

The survey results revealed a wide variety of staff were working in the LTC home sector internationally. Before the pandemic, in all countries, personal care, nursing care, and medical care staff were present. The numbers and categories of staff on site markedly decreased when the pandemic was declared in March 2020. Several essential members of the workforce were either absent, such as clergy, or worked virtually, such as physicians and social workers. Most staff that continued to work on site was unregulated, and who provided essential care with less support and oversight than was available pre-pandemic, to meet the needs of the LTC home residents, given the absolute reductions in staffing numbers. The summary of findings is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Findings.

| Staff Categories | Personal and Support Care Staff | Nursing Care | Medical Care | Rehabilitation and Recreational Care | Others | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RN | RPN | NP | PCP | Specialists | PT | OT | RT | Social Care | Clergy | Management | ||

| Present in-person before COVID-19 | Y (all) | Y (all) | 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8 | 1, 7, and 8 | Y (all) | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8 | 1,2, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 | 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 | 1, 3, 5, 7, and 8 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8 | 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 | Y (all) |

| Nature of employment | Part-time/zero hour scheduling Low wages |

Few hours a week or month | Churches offer service, no remuneration from LTCHs | |||||||||

| - Employed by LTCH | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1, 6, 7, and 8 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| - External contractor/self-employed | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1 and 7 | √ | √ | |||||

| Present during first wave of COVID-19 | Y (all) | Y (all) | 1, 2, 6, 7, and 8 | 1, 7, 8 | 1, 4, 7, and 8 | N | 1, 6, and 8 | 7 and 8 | 1 and 8 | 2 | 1, 6, and 8 | Y (all) |

| - IP | √ | √ | √ | √ | 6, 8 1 | √ 1 | √ 1 | √ 1 | √1 | |||

| - Virtual | 3 2 | √ | Mostly | 1 | √ | Sometimes virtually present | ||||||

| - DNA/absent | Sometimes absent due to shortage | √ | 2, 4, 5, and 7 | 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 | 3, 5, and 7 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8 | 3, 4, and 7 | |||||

| Overall impact of short staffing | ||||||||||||

| - Missed basic care | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| - Reduced care quality | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| - Untenable workload | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| - Less data collection and reporting | √ | |||||||||||

| - Increase reliance on agency staff | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

1 Canada; 2 China; 3 England; 4 Norway; 5 Spain; 6 Sweden; 7 Switzerland; 8 United States of America; Y: present; N: not present; RN: registered nurse; RPN: registered practical nurse; PCP: primary care physician; PT: physiotherapist; OT: occupational therapist; RT: recreation therapist; V: virtual; IP: in-person; DNA: deemed non-essential/absent; LTCH: long-term care home.

1Not present always due to sickness and quarantine.

2residential care homes.

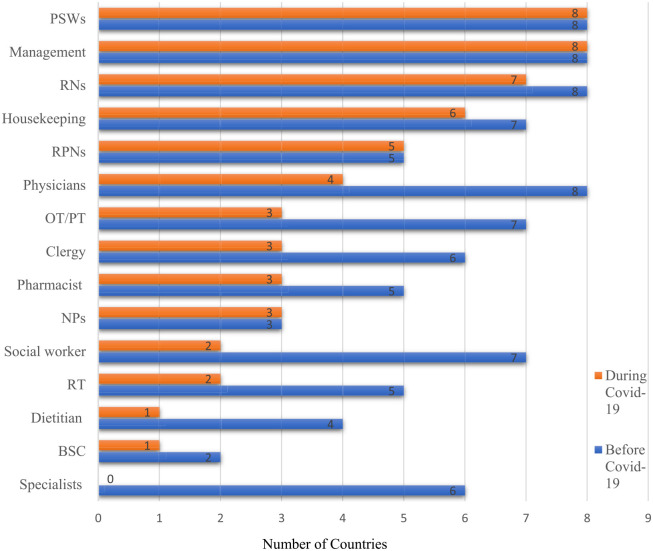

Figure 1 displays a comparison of staff present in LTC homes before and during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in eight countries. We organized the workforce data results in five broad categories based on their prominence in data and their direct involvement in resident care. The five broad categories included: (1) staff responsible for personal and support care, (2) nursing care that included registered nurses (RNs) and registered practical nurses (RPNs), (3) medical care that included nurse practitioners (NPs) and physicians, (4) rehabilitation and recreational care that included physiotherapists (PTs), physiotherapy assistants (PTA), occupational therapists (OTs), occupational therapy assistants (OTA), and therapeutic recreationists, and (5) others including social care staff, clergy, and management personnel. Where available, reports are cited in the results section to add further evidence to the data collected by experts, and the list of additional reports is attached as an online supplement (See Supplemental 1. Reports Referred by Researchers to Complete the Survey). The details on each of the above categories are presented below.

Figure 1.

Staff working in LTC homes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. RN: registered nurses; PSW: personal support worker; OT/PT: occupational therapist/physiotherapist; RPN: registered practical nurse; RT: recreation therapist; NP: nurse practitioner; BSC: behavior support clinician.

Personal and Support Care Staff

Personal and support care staff were also called personal support workers, nursing aids, and care workers depending on the terminology specific to the country. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, these staff were consistently “in the house” in all countries. However, short staffing of these workers had already been a long-standing problem in many countries because of factors such as low wages, less competitive job market in relation to other industries, for example, retail and fast food such as in the United States, and part-time job offerings with inconsistent hours, all of which resulted in many of them working in more than one setting (Van Houtven et al., 2020). Exceptions to this are Chinese and Swiss nursing aides, who typically worked for only one facility.

During the pandemic, these staff were present in-person and often managed greater responsibilities than before due to a reduced presence of other professional staff. (Jacobsen et al., 2021). Shortage of direct care staff was a huge challenge in the United States with many states and the federal government organizing “strike teams” to support understaffed nursing homes experiencing outbreaks (Andersen et al., 2021; Brown, 2020). In some countries, many of these staff were expected to work in only one LTC home to mitigate the risks associated with staff moving between the facilities, despite their personal need to work more than one job in order to make a decent living wage. Some countries chose to house the staff in the LTC homes to reduce community exposure. For example, during the first wave of pandemic when lockdown was imposed, nursing aides were required to live in nursing homes to avoid community exposure (e.g., in China). Similar anecdotes have been mentioned for some homes in the United Kingdom and Spain, although it was not a widespread practice (elDiarios.es, 2020).

Nursing Care Staff

All countries had nurses in the homes prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, LTC homes have had a lower ratio of nurses and other regulated staff than unregulated staff. For example, only 30% of care workers in Norway are RNs, and in Sweden, the numbers are even lower, with approximately 9% of the workforce consisting of registered nurses (Szebehely, 2020). Regulations in the United States require only one RN on site in a LTC home eight straight hours per day, every day of the week, while another RN should be on call if a practical nurse is working (Popejoy et al., 2022). Whereas in England, it was reported that homes that have nursing have nurses in their workforce, but those that are called residential care homes rely on community nurses to support care of complex residents. Also, there have been challenges in recruiting and retaining nurses to work in care homes as pay and benefits are more competitive and attractive in the National Health Service settings in the United Kingdom and in the public healthcare system in Spain. In Sweden, an RN is generally responsible for 30 residents during the daytime on weekdays and is responsible for 100–150 residents on evenings and weekends while sometimes being on call for some LTC home units. In China, junior nurses generally perform hands-on tasks, and more experienced senior nurses work as directors of nursing.

As the pandemic started, all countries had nurses in the house, however their numbers further decreased. In England, community nurses were less available to residential homes (homes that do not employ RNs) given the demands in other parts of the care system, but in later stages of the pandemic, they were available for virtual consultations. In Canada and Spain, their number reduced mainly due to sick calls and quarantine requirements. In Sweden, the Health and Social Care Inspectorate (The Health and Care Inspectorate [IVO], 2021) concluded that the availability of RNs was low due to the insufficient numbers from the outset; as well, their geographical area of responsibility was too expansive making it impossible to assess residents' conditions on site. Indeed, it was reported that many RNs were instructed to refrain from visiting patients with COVID-19 symptoms (IVO, 2021). RNs in Norway were deployed to units with COVID-19 cases, leading to fewer nurses in other units in LTC homes. Reports from Switzerland indicate that 44% of nursing homes compensated for staffing shortages with agency staff (Fries et al., 2021). Similar trends were seen in Canada and England, where due to sickness and quarantine, agency staff were called in to care for residents they were not familiar with. These nurses were seen as exacerbating infection control challenges due to their inexperience and travel from COVID-19 hot spot areas. In a May 2020 survey, nearly 16% of nursing homes in the United States reported shortages of nurses. Factors driving these shortages included COVID-19 infections among staff and limited personal protective equipment (PPE) (Xu et al., 2020).

Medical Care Staff

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries had physicians visit the homes on a regular basis and/or as needed. Some differences were noted, however, such as in Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland, as it was reported that LTC home residents usually kept their general practitioners (GP) when admitted to the facility. In the United States, every LTC home is required by federal regulations to employ a medical director, whose predominant focus is on the coordination of care and care quality standards rather than on providing direct services (Nanda, 2015). Main specialists in all countries were geriatricians, but some residents also had in-person access to a cardiologist, optometrist, podiatrist, dentist, psychiatrist, and/or psychologist. Many of these specialists (e.g., in Canada, Sweden, and Switzerland) required the resident to be transferred out of the LTC home to their office for an appointment. Overall, findings suggest that there were differences in accessing specialists to visit residents in LTC homes globally before the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, physicians were available virtually via video or telephone in most countries as they worked in multiple places. It was reported that in Canada and Switzerland, some homes had access to physicians’ in-person, and some worked closely with hospitals to manage acute episodic conditions of residents. In the United States, non-emergency healthcare was mostly eliminated or encouraged via telehealth. Although physicians were available virtually/by telephone or in-person in most cases in Sweden, it was reported that 20% of the residents with COVID-19 infection in LTC homes did not receive an individual medical assessment during the first wave of the pandemic. In China, in-person care and service were only provided if physicians were hired by residential care facilities, and those who worked in a part-time capacity provided virtual consultation only. No specialists were available in LTC homes in most countries as the pandemic began. Some specialists were available for virtual consultations; however, it was not always possible due to lack of staff to assist with setting up the call. In some cases, palliative care was also considered non-emergency care.

It is important to highlight the presence of NPs in the LTC home landscape. Before the pandemic, not all countries had NPs in their healthcare system. Where the role existed, only a few countries had NPs in their LTC home sector. For example, in Canada, some homes employed them as attending NPs and some had NP-led outreach teams responsible for several homes with the goal of averting hospital transfers by treating residents in-house. In the United States, all states have NPs; however, they can work at their full scope of practice in 24 states only. In England, NPs are not employed by LTC homes, but they may visit to consult and offer input for some residents and in Spain, Norway, Sweden, and China there is not an established role for NPs.

During the pandemic, in Canada and the United States, the role of NPs was expanded where they were allowed to work at their full scope of practice (McGilton et al., 2021; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020). They worked with physicians who worked remotely, helped hospital teams with decanting, addressed urgent and episodic clinical issues, including end-of-life care, and facilitated advance care planning and goals of care discussions with residents and their family care partners (McGilton et al., 2021; Vellani et al., 2021).

Rehabilitation and Recreation Care Staff

The presence of OT and PT staff varied in different countries even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some homes in Canada and Switzerland recruit OTs as part of their staff complement. Countries such as England, Norway, and Sweden oftentimes do not have OTs employed by LTC homes, but the services are offered by external consultants or in short-term units where residents are rehabilitated post-acute care admission to return to community. In the USA, federal regulations require every nursing home to establish an activities program that is run by an OT or an OTA. In the US, OTs and PTs may be hired as contract staff and work closely with LTC home teams. In China, only large homes had staff that performed similar functions as OTs and PTs; however, they have different designations. Whereas in Spain, they work in part-time capacity, depending on the size of the home.

In Canada, the number of therapeutic recreationists, who engage residents in joyful and meaningful activities in LTC homes can be as low as 1 per 60 residents (Therapeutic Recreation Ontario [TRO], 2020). Many other countries have incorporated similar staff coordinating residents’ activities, but their numbers are few. In England, their role existed in some homes; however, data related to their numbers is generally not available, whereas recreational therapy staff are not generally hired as part of the workforce in China.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, OTs continued to be present in the United States but were absent from LTC homes in most other countries as they were deemed non-essential. In Canada, many OTs and PTs reorganized their interventions to be delivered one-on-one rather than in a group. In Switzerland, 90% of the LTC homes restricted access of OTs, PTs, and other therapeutic personnel during the first wave, and 84% restricted group activities to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks (Fries et al., 2021). In Spain, OTs, PTs, and recreation therapy staff were removed from their regular function and deployed to perform direct care due to staff shortages.

Others

The presence of other categories of staff such as social workers, clergy, and management personnel before and during the pandemic was also reported on across the eight countries. Requirements for employing a licensed social worker onsite tend to be minimal or non-existent depending on the country, and although most countries had social workers in some capacity prior to the pandemic, their roles ranged from serving in a recreation activity such as in China, to being responsible for all psychosocial needs, such as in the United States. Social workers are generally not employed in Swedish LTC homes given that LTC homes follow a social model of care, where all staff are obligated to provide social care based on each resident’s personal needs and interests. In terms of clergy, there is large variation with regards to their presence in LTC Homes. For example, in Norway, clergy is present at the time of residents’ deaths. In Switzerland, counselors are hired and paid by churches to provide end-of-life support several hours every week. It was reported that in Sweden, Canada, and the United States, spiritual care was generally provided by local churches on a voluntary basis.

With regard to management personnel, the structure varied based on the type of home (e.g., for profit vs. not-for-profit). For example, it was reported that in England, homes part of large corporate groups had regional senior staff such as for human resources, finance, quality improvement, education, and training, while smaller care homes mostly had a proprietor and care home manager. In China, management teams served as steering members of the leadership and supervision committee and made sure that LTC homes operated safely and efficiently.

Social workers were generally absent from the homes during the pandemic, except in China and the United States. In China, they served in management committees to help with implementing infection prevention and control procedures, and communication with families. In the United States, social work services were discouraged early in wave one due to a shortage of PPE and some LTC homes deemed them non-essential. During this period, they worked remotely, like Canada. Later, social services became more critical than ever when visitation restrictions removed family members from the LTC homes. Clergy was generally not accessible during the pandemic in most places, while there are some reports of virtual services such as in Switzerland. Management personnel generally worked from home to curtail the spread of COVID-19 in several countries. It was reported that some were off sick in Canada requiring hospital teams to provide voluntary management coverage. In the United States, management staff were mostly present in-person onsite.

Overall, the researchers’ impressions of the impact of the staffing changes during COVID-19 were also highlighted (see Table 1). Short staffing was multifactorial caused by acute issues resulting from the pandemic, superimposed on the chronic insufficiencies in the LTC homes. They led to missed basic care and reduced care quality for residents. Also, staff experienced untenable workloads, with an increased reliance on the agency staff who had no prior rapport with the residents.

Discussion

The current study provides first approximation data from eight countries including Canada, China, England, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States and focused on the staffing trends before the COVID-19 pandemic and what changed during the first wave of the pandemic. It was evident that there is limited availability of data in general related to staffing categories working in LTC homes, and different job titles were used for the same type of staff in different countries, making synthesis more challenging. Nevertheless, the survey results highlighted that some staff personnel were either absent or worked remotely during the pandemic. Various types of staff were thus deemed non-essential with regards to fighting the virus at the LTC homes. The pandemic has provided us with an opportunity to think about who were considered essential and why, how, and who made these determinations impacting the care and quality of life of residents. In terms of who was in the house pre-pandemic, most experts from the eight countries reported on having the five categories of staff working in their LTC homes: personal and support care workers, nursing and medical care staff, rehabilitation, recreational and social care staff, and management. However, during the pandemic, rehabilitation, social care, and medical care staff were less frequently present.

With reference to who stayed in the house during the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some similarities between countries as reported by our experts. Care workers and registered staff remained and were deemed essential. However, short-staffing and reliance on contract staff exacerbated across the LTC homes due to illness, quarantine requirements, and staffing policies such as zoning and cohorting, but more staff were needed than before to manage higher acuity and greater care needs caused by the pandemic. There is evidence that unregulated staff such as personal support workers and other support or assistant staff saw a dramatic increase in their workloads and experienced shifting of tasks due to a lack of regulated staff (Doctors Without Borders, n.d.; Jacobsen et al., 2021; Spilsbury et al., 2020). Many additional barriers led to further worsening of COVID-19 case numbers in the LTC homes for those who remained in the home during the pandemic, for example, staffing shortages, frequent staff turnover, lack of leadership support, lack of PPE, and lack of training and education (Snyder et al., 2021). COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity for natural experiments where members of different disciplines tried their best to provide for their residents’ need. However, previous studies have shown significant improvement in outcomes (e.g., pressure ulcers and restraint use) when there was a higher proportion of RNs to RPNs or PSWs (Clemens et al., 2021). Thus, future studies should examine the impact on quality of other factors such as skill mix of the LTC home staff, transdisciplinary models of care, access to technology, leadership support, access to training, and other resources.

During the pandemic, in most countries, OTs, PTs, and social workers were deemed non-essential which most likely not only caused residents’ functional decline and deconditioning and social isolation but also increased incidents of responsive behaviors in those living with dementia. COVID-19-related restrictions made it impossible to offer group activities resulting in more than half of the residents requiring behavioral interventions not receiving them (Gerritsen & Oude Voshaar, 2020). Although virtual interventions were suggested, they were not as effective given the time, resources, and efforts required to set them up, and many homes lacked the basic technological infrastructure to accommodate virtual care (Chu et al., 2021). Given that many residents survived a COVID-19 infection, they missed the rehabilitation needed to overcome the functional decline they suffered during the infection (Spilsbury et al., 2020). While the vast majority of COVID-19 deaths occurred in LTC homes, there was a lack of prioritization of LTC home residents’ social, rehabilitation, and recreational needs (TRO, 2020; Genoe & Johnstone, 2021). Subsequently, there is need for the governments to recognize the role of OTs, PTs, social workers, and therapeutic recreationists and include them in LTC home staff mix while increasing their ratio to residents and the average hour of care provided by each of these staff category. In addition, considering them essential during future pandemics may be also a wise policy and practice decision.

In terms of medical coverage across the countries, most of the physicians worked remotely in the LTC homes. This led to legislative changed enabling NPs to work at their full scope of practice and support the national pandemic response (McGilton et al., 2021; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020). Consequently, their role should be expanded and further explored in other countries given the impact they have on staff and resident outcomes.

Across most of the countries, most managers worked within the home to provide leadership during COVID-19. In order to optimize staff well-being, the role of LTC home leadership is deniably critical to ensure staff flexibility and task shifting if required (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; World Health Organization, 2017). Amid this crisis, it is clear that all levels of staff needed support and psychosocial care to strengthen resilience (Bern-Klug & Beaulieu, 2020). It is therefore critical that supervisors are trained to develop salient qualities necessary to support the physical and psychosocial well-being of staff and to mitigate staff turnover. There is evidence of variability in what constitutes the most appropriate staffing level to positively impact high-quality indicators for resident care, even in regions where minimum staffing regulations are in place (Clemens et al., 2021). Hence, there is need to develop evidence-informed models of care for optimal staff and skill mix needed to better respond to complexities around resident care. And appropriate workforce planning is only possible if comprehensive high-quality data is collected and available on who is actually present in the LTC homes and the impact of absence of those deemed “non-essential.”

Limitations

There are limitations to the findings of this survey report. It was gathered by international researchers who consulted with known experts, clinicians, and researchers and reports accessible in their countries. There is a risk of selection bias in terms of the inclusion of reports and experts in acquiring the data for this study. However, to reduce the potential bias, the survey was devised by the full research team and tested by the senior researcher in the team and modified before it was implemented. The current study only reports on five major categories of staff common in eight countries missing on the perspectives related to others. The data provided here is the first approximation to more precise determination when common data elements are identified.

Conclusion

There is a widespread appreciation for the need for change in LTC home sector, given force by the experiences of a pandemic. However, it is now time that changes are materialized in policy initiatives. We require standardized high-quality workforce data for the LTC home sector that should also include information on staff turnover; their psychological well-being and workplace-related infections and injuries; and the different categories of personnel who are actually in the house. The end goal is that better decision-making tools are designed for staffing and planning in the LTC home sectors, which are in line with the complex care needs of the residents, and which prevent further development of precarious work conditions in the LTC sector.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ggm-10.1177_23337214221090803 for Who’s in the House? Staffing in Long-Term Care Homes Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic by Shirin Vellani, Franziska Zuniga, Karen Spilsbury, Annica Backman, Nancy Kusmaul, Kezia Scales, Charlene H. Chu, José Tomás Mateos, Jing Wang, Anette Fagertun and Katherine S. McGilton in Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs: Shirin Vellani  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6032-0266

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6032-0266

Franziska Zuniga  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8844-4903

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8844-4903

Nancy Kusmaul  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2278-8495

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2278-8495

Katherine S. McGilton  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2470-9738

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2470-9738

References

- Andersen L. E., Tripp L., Perz J.F., Stone N.D., Viall A. H., Ling S.M., Fleisher L.A. (2021). Protecting nursing home residents from Covid-19: Federal strike team findings and lessons learned. NEJM catalyst innovations in care delivery.https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0144. [Google Scholar]

- Bern-Klug M., Beaulieu E. (2020). COVID-19 highlights the need for trained social workers in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(7), 970-972. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscart V. M., Sidani S., Poss J., Davey M., d’Avernas J., Brown P., Heckman G., Ploeg J., Costa A. P. (2018). The associations between staffing hours and quality of care indicators in long-term care. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 750. 10.1186/s12913-018-3552-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. (2020). Multiple states using strike teams to combat COVID-19 in nursing homes. McKnights Long-Term Care News.https://www.mcknights.com/news/multiple-states-using-strike-teams-to-combat-covid-19-in-nursing-homes/. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Sharing and shifting tasks to maintain essential healthcare during COVID-19 in low resource, non-US settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/global-covid-19/task-sharing.html#print. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2020). COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf.

- Chu C. H., Ronquillo C., Khan S., Hung L., Boscart V. (2021). Technology Recommendations to Support Person-Centered Care in Long-Term Care Homes during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 33(4-5), 539-554. 10.1080/08959420.2021.1927620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S., Wodchis W., McGilton K., McGrail K., McMahon M. (2021). The relationship between quality and staffing in long-term care: A systematic review of the literature 2008–2020. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 122(3), 104036. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corazzini K. N., Anderson R. A., Bowers B. J., Chu C. H., Edvardsson D., Fagertun A., Gordon A. L., Leung A. Y. M., McGilton K. S., Meyer J. E., Siegel E. O., Thompson R., Wang J., Wei S., Wu B., Lepore M. J. WE-THRIVE (2019). Toward common data elements for international research in long-term care homes: Advancing person-centered care. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 20(5), 598-603. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctors Without Borders., (n.d.). Poco, tarde y mal El inaceptable desamparo de las personas mayores en las residencias durante la COVID-19 en España. https://www.msf.es/sites/default/files/documents/medicossinfronteras-informe-covid19-residencias.pdf

- elDiarios. (2020). Trabajadores de otras tres residencias de mayores se encierran para proteger a los ancianos y a sus familias [Press release]. https://www.eldiario.es/extremadura/trabajadores-residencias-mayores-encierran-proteger_1_1221239.html

- Fagertun A. (2021). Absorbing care through precarious labou: the shifting boundaries of politics in Norwegian healthcare. In Pine H. H. F. (Ed), Intimacy and mobility in an era of hardeining borders: Gender, reproduction, regulation (pp. 199-217). Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fries S., Trageser J., von Stokar T., Vettori A., von Dach A., Ehmann B., Mäder A. (2021). Situation von älteren menschen und menschen in alters-, pflege- und betreuungsinstitutionen während der Corona-pandemie. Grafikband mit Ergebnissen der Befragung von institutionsleitenden. Zürich: Infras. [Google Scholar]

- Genoe M. R., Johnstone J. L. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on therapeutic recreation practice in long-term care homes across Canada. World Leisure Journal, 63(3), 265-280. 10.1080/16078055.2021.1957011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen D. L., Oude Voshaar R. C. (2020). The effects of the COVID-19 virus on mental healthcare for older people in The Netherlands. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(11), 1353-1356. 10.1017/S1041610220001040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers J. (2011). De intramurale ouderenzorg: nieuwe leiders, nieuwe kennis, nieuwe kansen. Den Haag: Raad voor de Volksgezondheid en Zorg. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J. P. A. (2020). Global perspective of COVID-19 epidemiology for a full-cycle pandemic. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 50(12), e13423. 10.1111/eci.13423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen F. E. A., Arntzen C., Devik S. A., Førland O., Krane M.S., Madsen L., Moholt J., Olsen R. M., Tingvold L., Tranvåg O., Ågotnes G., Aasmul I. (2021). Erfaringer med COVID-10 i norske sykehjem. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/5d388acc92064389b2a4e1a449c5865e/no/sved/12jacobsen-mfl.-2021.pdf

- Kaasalainen S., Mccleary L., Vellani S., Pereira J. (2021). improving end-of-life care for people with dementia in ltc homes during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 24(3), 164-169. 10.5770/cgj.24.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans L., Damen N., Wagner C. (2018). Does diverse staff and skill mix of teams impact quality of care in long-term elderly health care? An exploratory case study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 988. 10.1186/s12913-018-3812-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague L. J., de Los Santos J. A. A., Fronda D. C. (2021). Factors associated with missed nursing care and nurse-assessed quality of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(1), 62-70. 10.1111/jonm.13483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo F. L., Salvi E., Lacorte E., Piscopo P., Mayer F., Ancidoni A., Remoli G., Bellomo G., Losito G., D’Ancona F., Canevelli M., Onder G., Vanacore N, … Italian National Institute of Health Nursing Home Study, … Group (2020). Adverse events in Italian nursing homes during the COVID-19 epidemic: A national survey. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 578465-578465. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.578465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilton K. S., Backman A., Boscart V., Chu C., Gea Sánchez M., Irwin C., Meyer J., Spilsbury K., Zheng N., Zúñiga F. (2020). Exploring a common data element for international research in long-term care homes: A measure for evaluating nursing supervisor effectiveness. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 6, 2333721420979812. 10.1177/2333721420979812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilton K. S., Krassikova A., Boscart V., Sidani S., Iaboni A., Vellani S., Escrig-Pinol A. (2021). Nurse Practitioners Rising to the Challenge During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic in Long-Term Care Homes. The Gerontologist (61(4)615-623). 10.1093/geront/gnab030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda A. (2015). The roles and functions of medical directors in nursing homes. Rhode Island Medical Journal, 98(3), 20-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popejoy L. L., Vogelsmeier A. A., Canada K. E., Kist S., Miller S. J., Galambos C., Alexander G. L., Crecelius C., Rantz M. (2022). A call to address rn, social work, and advanced practice registered nurses in nursing homes: Solutions from the missouri quality initiative. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 37(1), 21-27. 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales K. (2021). Transforming direct care jobs, reimagining long-term services and supports. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 23(2), 207-213. 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder R. L., Anderson L. E., White K. A., Tavitian S., Fike L. V., Jones H. N., Jacobs-Slifka K. M., Stone N. D., Sinkowitz-Cochran R. L. (2021). A qualitative assessment of factors affecting nursing home caregiving staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One, 16(11), e0260055. 10.1371/journal.pone.0260055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilsbury K., Devi R., Daffu-O’Reilly A., Griffiths A., Haunch K., Jones L., Meyer J. (2020). LESS COVID-19. Learning by experience and supporting the care home sector during the COVID-19 pandemic: Key lessons learnt, so far, by frontline care home and NHS staff. https://niche.leeds.ac.uk/news/niche-leeds-and-national-care-forum-publish-less-covid-19-report/

- Szebehely M. (2020). Internationella erfarenheter av covid-19 i äldreboenden. underlagsrapport till SOU 2020: 80 äldreomsorgen under pandemin, stockholm Hentet fra. https://www.regeringen.se/4af363/contentassets.

- The Health and Care Inspectorate (IVO). (2021). Conditions for good care and treatment at SÄBO are lacking and lead to shortcomings. https://www.ivo.se/publicerat-material/nyheter/2021/forutsattningar-for-god-vard-och-behandling-pa-sabo-saknas-och-leder-till-brister/

- Therapeutic Recreation Ontario (TRO). (2020). Therapeutic Recreation Ontario: A Blueprint to combat LTC residents’ helplessness, loneliness and boredom. https://www.trontario.org/files/Advocacy/TRO-LTC-Commission-Submission-Nov-2020.pdf

- Van Houtven C. H., DePasquale N., Coe N. B. (2020). Essential long-term care workers commonly hold second jobs and double- or triple-duty caregiving roles. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8), 1657-1660. 10.1111/jgs.16509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani S., Boscart V., Escrig-Pinol A., Cumal A., Krassikova A., Sidani S., Zheng N., Yeung L., McGilton K. S. (2021). Complexity of nurse practitioners' role in facilitating a dignified death for long-term care home residents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(5), 433. 10.3390/jpm11050433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Global health workforce shortage to reach 12.9 million in coming decades. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/health-workforce-shortage/en/

- Xu H., Intrator O., Bowblis J. R. (2020). Shortages of staff in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: What are the driving factors? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(10), 1371-1377. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Sloane P. D. (2007). Long Term Care. In Birren J. E. (Ed), Encyclopedia of Gerontology (2nd ed., pp. 99-107). NY: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ggm-10.1177_23337214221090803 for Who’s in the House? Staffing in Long-Term Care Homes Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic by Shirin Vellani, Franziska Zuniga, Karen Spilsbury, Annica Backman, Nancy Kusmaul, Kezia Scales, Charlene H. Chu, José Tomás Mateos, Jing Wang, Anette Fagertun and Katherine S. McGilton in Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine