Abstract

Chromium is a harmful contaminant showing mutagenicity and carcinogenicity. Therefore, detection of chromium requires the development of low-cost and high-sensitivity sensors. Herein, blue-fluorescent carbon quantum dots were synthesized by one-step hydrothermal method from alkali-soluble Poria cocos polysaccharide, which is green source, cheap and easy to obtain, and has no pharmacological activity due to low water solubility. These carbon quantum dots exhibit good fluorescence stability, water solubility, anti-interference and low cytotoxicity, and can be specifically combined with the detection of Cr(VI) to form a non-fluorescent complex that causes fluorescence quenching, so they can be used as a label-free nanosensor. High-sensitivity detection of Cr(VI) was achieved through internal filtering and static quenching effects. The fluorescence quenching degree of carbon dots fluorescent probe showed a good linear relationship with Cr(VI) concentration in the range of 1–100 μM. The linear equation was F0/F = 0.9942 + 0.01472 [Cr(VI)] (R2 = 0.9922), and the detection limit can be as low as 0.25 μM (S/N = 3), which has been successfully applied to Cr(VI) detection in actual water samples herein.

Keywords: Carbon dots, Alkali-soluble Poria cocos polysaccharide, Cr(VI) detection, Internal filtering effect, Static quenching effect

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Carbon dots was synthesized from alkaloid-soluble Poria cocos polysaccharide, which used for Cr (VI) detection.

-

•

High sensitivity and selectivity detection of Cr(VI) based on internal filtering effect and static quenching mechanism.

-

•

The method analysis speed is quick, sensitive, raw materials for convenient, inexpensive.

-

•

The method has been applied to the determination of Cr(VI) in actual samples with satisfactory recovery.

1. Introduction

Chromium is one of the most common heavy-metal pollutants detected in industrial wastewater [1,2]. There are two primary oxidation states: trivalent chromium (Cr(III)) and hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) [3,4]. Among them, Cr(III) is an essential nutrient for organisms as it exhibits little fluidity, little toxicity, and no harm. Owing to the high oxidation potential of Cr(VI) and the liquid inside the cell membranes of organisms, Cr(VI) has mutagenic and carcinogenic effects on the human body, which are extremely harmful to health [5,6]. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency suggested that the concentration of Cr(VI) in drinking water should be lower than 100 ppb (µg/L) [7]. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the concentration of Cr(VI) for the characteristics of migration and cumulative effect in water samples [8]. Many analytical methods have been developed for accurate ion detection, such as colorimetry [9,10], electrochemical methods [11,12], atomic absorption spectrometry [[13], [14], [15]], inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry [16], chromatography [17], and spectrophotometry [18]; however, their practical applications in various fields are hindered by the need for expensive instruments and environment unfriendly chemicals [19]. Conversely, the fluorescent probe method has the advantages of simple sample pretreatment [20], fast response, wide linear dynamic range, small interference, high sensitivity [21], and can meet the requirements of industrial applications [22].

Carbon dots (CDs) are environment friendly fluorescent nanomaterials exhibiting low toxicity, good water solubility, and excellent optical properties compared with traditional quantum dots, which are the best alternative to fluorescent probes in biosensors and biological imaging [23,24]. Various raw materials can be used for CD synthesis; these usually include inorganic materials [25,26], biological materials [[27], [28], [29]], and waste materials [30] and are mainly synthesized through hydrothermal or microwave treatment. However, there are few reports on the synthesis of cheap, easily available, and environmentally friendly Chinese herbal medicine, monomer, or extract of Chinese herbal medicine as the source material. Currently, there are many studies on using CDs as sensors for metal ion detection, whose main detection principle is the quenching effect caused by the varying affinity between the CD's surface functional groups and the target. Sun et al. [31] synthesized fluorescent carbon quantum dots with Lycii Fructus as the raw material. Abundant hydroxyl groups on the surface formed a complex with Fe3+ through coordination, exhibiting an internal filtering effect, which could quench the fluorescence of CDs. Wu et al. [32] synthesized low-cost and environment friendly photoluminescence carbon quantum dots with giant knotweed rhizome as the carbon source and utilized the interaction between carboxyl and Hg2+ on the surface of CDs to form chelates, which were detected through electron or energy transfer.

The application of alkali-soluble Poria cocos polysaccharide is greatly restricted owing to its poor water solubility. Structural modification is usually conducted in studies to obtain substances displaying biological activities. Based on the abundant carbon and oxygen elements in polysaccharides, they can be used as raw materials for the synthesis of CDs. Therefore, it was considered as a potential raw material to synthesize CDs derived from traditional Chinese medicine, in an attempt to improve its water solubility and broaden its application range. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study wherein CDs were synthesized using a novel, simple, and green hydrothermal synthesis method with nonactive Poria cocos polysaccharide and ethylenediamine. CDs were characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–vis), and fluorescence (FL) spectroscopy. The prepared CDs exhibited good light stability and anti-interference ability. Herein, we propose an effective fluorescence sensor to achieve high selectivity and sensitivity detection of Cr(VI) (Scheme 1). Owing to the overlap between the ultraviolet absorption band of Cr(VI) and the excitation band of CDs, the detection mechanism of Cr(VI) is related to the internal filtration effect (IFE) and static quenching effect. Within the linear concentration range, the fluorescence intensity of CDs is quenched by Cr(VI) with high selectivity and the detection limit is 0.25 μM. This fluorescent “on-off” probe detection technique has been successfully applied to the detection of chromium ions in real water samples.

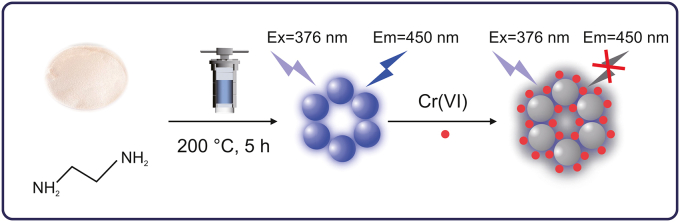

Scheme 1.

Schematic of the preparation and detection of Cr(VI) using CDs fluorescent probe. Ex: excitation; Em: emission: CDs: carbon dots.

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and chemicals

Poria cocos polysaccharide was purchased from Chengdu Chroma-Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Ethylenediamine and quinine sulfate were purchased from Aladdin Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and the dialysis bag (retained molecular weight: 1000 Da) were purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The standard Cr(VI) stock solution was prepared from K2Cr2O7. Other metal ion stock solutions were prepared from their nitrate, sulfate, or chloride salts. All other reagents were of analytical grade and were used directly without further purification. Milli-Q ultrapure water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm was used in all aqueous solutions.

2.2. Apparatus

TEM was conducted using a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 transmission electron microscope (FEI Co., Portland, ME, USA) at an operating voltage of 200 kV. Absorption spectra were obtained on a SPECORD S600 UV–vis spectrometer (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). Fluorescence spectra were measured on an F-4600 Spectro fluorophotometer (HITACHI Co., Ltd., Hitachi, Japan) with excitation and emission slits of 5 nm and a photomultiplier tube voltage of 600 V. Zeta potentials were measured on a ZEN3690 (Malvern Co., Worcestershire, UK) at room temperature. FTIR spectra were investigated using KBr pellets on a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 4000–500 cm−1. XPS was conducted on a Kratos AXIS SUPRA spectrometer (Shimadzu, Shanghai, China). Fluorescence lifetime was recorded on an FLS1000 fluorescence spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., Edinburgh, UK).

2.3. Synthesis of CDs

CDs were synthesized via a one-step hydrothermal method using Poria cocos polysaccharide as the carbon source. Briefly, Poria cocos polysaccharide (0.45 g) was dissolved in 30 mL of distilled water and was subjected to ultrasound for 5 min. Then, 5.5 mL of ethylenediamine was added to the above solution and was subjected to ultrasound for 15 min. Subsequently, the mixture solutions were transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave having a 50 mL capacity and heated at 200 °C for 5 h. After cooling to room temperature, a dark brown solution was obtained after centrifugation at 11,400 g for 15 min and filtered using a 0.22-μm membrane to remove large particles. The resultant solution was subjected to dialysis (molecular weight cut off = 1000 Da) for 24 h at room temperature. Finally, the CDs were freeze-dried under vacuum to obtain a brown solid.

2.4. Fluorescence quantum yield (QY) measurement

Quinine sulfate in 0.1 M H2SO4 (QY [33] is 0.54 at 360 nm, η = 1.33) was used as the standard substance to determine the fluorescence QY of synthetic CDs, which was determined according to the following formula:

| (1) |

The QYs of CDs and quinine sulfate are expressed by QY and QYR, respectively. I represents the integrated fluorescence intensity at the same excitation wavelength. A is the absorbance measured with a UV–vis spectrophotometer. ηS and ηR represent the solvent refractive index of CDs and quinine sulfate, respectively.

2.5. Fluorescent measurement of Cr(VI)

Typical detection and measurement methods involved the following ones. First, a certain number of CDs were dissolved in PBS (pH = 6.5, 0.01 M) solution to prepare the final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Second, different concentrations of Cr(VI) were added; after incubation for 25 min at 37 °C, their fluorescence emission spectrum was recorded under an excitation wavelength of 376 nm. The selectivity for Cr(VI) ions was tested by adding other metal ions instead of Cr(VI) in a similar manner.

2.6. Real sample assay

Water samples were collected from tisanes, rainwater, and river water. Syringe filters (0.22 μm) were used to filter water samples, which were then spiked with various concentrations of Cr(VI) before mixing with CDs. The fluorescence spectra of the samples were recorded after 25 min of incubation at 37 °C.

2.7. MTT assay

An MTT assay was used to evaluate the in vivo toxicity of CDs. First, HepG2 cells were collected, the cell suspension concentration was adjusted to 1 × 105 cells/mL, and the cell suspension and PBS were added to each well of the 96-well plate and cultured in an incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. When the cells covered the bottom of the well, the culture was discarded. Second, 200 μL of CDs with different concentrations (repeated six times for each concentration) were added and cultured in an incubator at 37 °C for 24 h. Third, 20 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT solution was added and cultured for 4 h. Then, 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added. Finally, the absorbance of each well was measured at 490 nm after shaking for approximately 10 min.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of CDs

CDs were synthesized from Poria cocos polysaccharide and ethylenediamine via a one-step hydrothermal process and were characterized via TEM, FTIR, and XPS. The TEM image depicted in Fig. 1A shows that CDs have spherical monodisperse particles, and the diameter range of CD particles is extremely narrow (2–10 nm) with an average particle size of 4.61 nm. To confirm the presence of various functional groups in CDs, we recorded the FTIR spectra (Fig. 1B). The broad absorption peak centered at 3364 cm−1 is attributed to the characteristic stretching vibrations of O–H and N–H bonds, and the peak at 2925 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibrations of C–H. The peaks at 1642 and 1408 cm−1 are associated with COO− stretching vibrations. The characteristic absorption bands of C–N and N–H stretching vibrations appeared at 1581 and 854 cm−1, respectively. Furthermore, the peak at 1027 cm−1 can be attributed to the C–O band [7,34]. The surface element characteristics of CDs were further confirmed using XPS. In the XPS spectra (Fig. 1C), the three peaks at 284.6, 399.1, and 532.2 eV correspond to C1s, N1s, and O1s, respectively, clearly indicating that the CDs contain C, N, and O, atomic ratio (%) of C:N:O = 69.19:5.05:25.77 (the inset of Fig. 1C). As shown in Fig. 1D, the high-resolution spectrum of the C1s signal contains six binding energy peaks of –COOH at 289.71 eV, C N/O–C O at 288.59 eV, C–OH at 287.06 eV, C–O/C–N at 285.99 eV, C–N at 285.45 eV, and C–C/C C at 284.80 eV [[35], [36], [37], [38]]. The partial XPS spectrum of N1s can be divided into five component peaks with binding energies at about 402.10, 400.50, 400.26, 399.69, and 399.01 eV, respectively, which are due to the existence of N–O, N–H, graphitic nitrogen (C)3–N, pyrrolic nitrogen, and pyridinic nitrogen, respectively (Fig. 1E). In the high-resolution O1s XPS spectrum (Fig. 1F), the three peaks at 534.70, 533.34, and 531.61 eV are attributed to H–O–H, C=O, and C–OH [39], respectively. FTIR and XPS data reveal that the synthesized CDs have abundant hydrophilic groups, such as hydroxyl (−OH), carboxyl (−COOH), and amine (−NH2) moieties, which could help to improve the solubility of CDs in aqueous solution.

Fig. 1.

(A) Transmission electron microscopy image of CDs (inset: the size distribution). (B) Fourier transform infrared spectra of CDs. (C) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra of CDs. (D) C1s. (E) N1s. (F) O1s spectra of CDs.

3.2. Photoluminescence (PL) properties of CDs

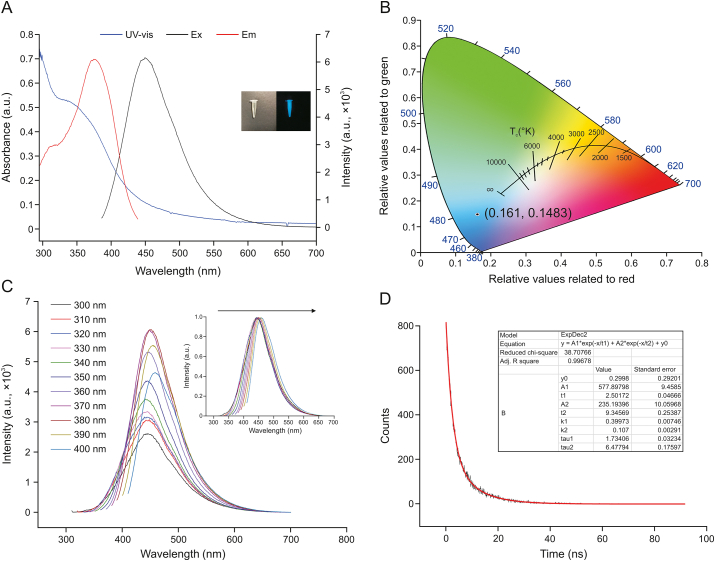

The optical properties of CDs were characterized through fluorescence spectroscopy and UV–vis absorption. In the UV–vis absorption spectrum of the CDs in Fig. 2A, two strong absorption bands at approximately 297 and 320 nm can be observed. The absorption peak at 297 nm corresponded to the π–π∗ transition of C C/C N [40]. A weak shoulder peak at 320 nm is attributed to the n–π∗ transitions in the C O/C–NH2 moieties on the surface of CDs [41,42]. CDs emit strong blue fluorescence under irradiation with a 365 nm UV lamp (inset in Fig. 2A). In addition, Fig. 2A shows a strong fluorescence emission peak at 450 nm under excitation at 376 nm. As is shown in Fig. 2B, the blue fluorescence of as-synthesized CDs was further confirmed through the CIE coordinates at (0.161, 0.1483), which were acquired from the fluorescence emission data at the 376 nm excitation. Moreover, the fluorescence spectrum of CDs at different excitations was recorded, as shown in Fig. 2C. By increasing the excitation wavelength from 300 to 400 nm, the PL peak of CDs showed a redshift (the inset in Fig. 2C) and the PL intensity of CDs first increased and subsequently decreased. These observations suggested that the CDs were excitation-dependent emission CDs, which could be attributed to different size distributions and surface states formed by different functional groups. To clarify the fluorescence mechanism of CDs, we measured the fluorescence lifetime (Fig. 2D). Based on the nonlinear least-squares analysis, the decay curve could be fitted to biexponential functions Y(t) with an average lifetime of 6.24 ns. In addition, the fluorescence QY of CDs was measured to be about 4.82% with quinine sulfate (54%) as fluorescence standard by reference method.

Fig. 2.

(A) Ultraviolet−visible spectroscopy (UV−vis) absorption spectrum, fluorescence excitation, and emission spectra of CDs. The inset shows photographs of CDs solution in ambient light (left) and under irradiation by 365 nm UV light (right). (B) Image of CIE coordinates showing the blue color of CDs. (C) The fluorescence spectrum of CDs under different excitation wavelengths (inset: corresponding normalized spectra). (D) Decay curve of CDs (λex = 376 nm and λem = 450 nm).

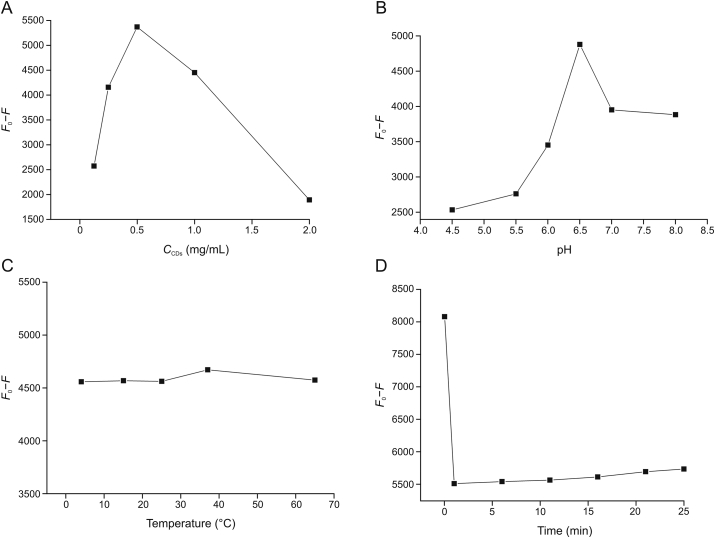

In addition, the stability of the obtained CDs was further studied. In Fig. 3A, CDs exhibit strong fluorescence stability under a xenon lamp for 30 min. The fluorescence intensity of the CDs first increased and subsequently decreased in the pH range from 1 to 13 (Fig. 3B), which is ascribed to the surface of the CDs being rich in carboxyl and hydroxyl groups. Furthermore, CDs rich in negative charge on the surface were protonated in the low-pH environment, which led to their aggregation and fluorescence quenching [[43], [44], [45]] (Fig. 3B). As depicted in Fig. 3C, no obvious variation in the intensity was found with the increase of NaCl concentration (0–2.0 mol/L), indicating the high salt tolerance of the CDs. Finally, CDs also exhibit high resistance to photobleaching and the fluorescence intensity remains constant for at least half a month, as shown in Fig. 3D. These results suggest that CDs may have more potential practical applications. In general, they exhibited inherent water solubility, good anti-interference property, and high PL stability under weak acidity conditions and had potential in metal ion detection and biological application.

Fig. 3.

(A) Effect of the irradiation time of a xenon lamp on the fluorescence intensity of CDs. (B) Effect of pH on the fluorescence intensity of CDs. (C) Effect of the ionic strength of NaCl (0–2.0 mol/L) on the fluorescence intensity of CDs. (D) Effect of the storage time on the fluorescence intensity of CDs.

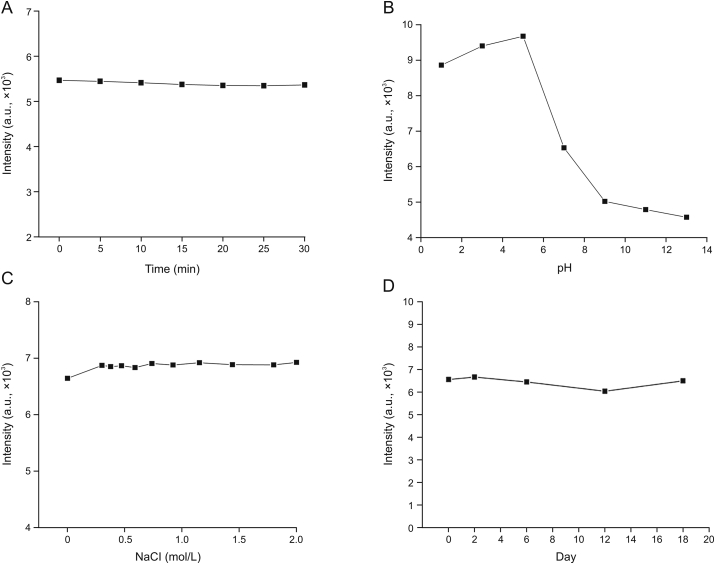

3.3. Optimization of analytical parameters

The sensitivity of the detection method strongly depends on the relevant experimental parameters, including the concentration of CDs, pH values of the solution, incubation time, and temperature, which were evaluated by the fluorescence quenching efficiency (ΔF) (ΔF refers to F0–F, and F0 and F represent the fluorescence intensities of CDs at 376 nm in the absence and presence of Cr(VI) ion). The corresponding results are presented in Fig. 4. For optimizing each parameter, all other parameters were determined under optimal conditions.

Fig. 4.

(A) Effect of the concentration of CDs on the fluorescence intensity of system. (B) Effect of the pH of PBS on the fluorescence intensity of system. (C) Effect of the temperature on the fluorescence intensity of system. (D) Effect of the reaction time on the fluorescence intensity of system.

As illustrated in Fig. 4A, the influence of different concentrations of CDs on the FL intensity was investigated, ΔF is maximum when the concentration is 0.5 mg/mL. Therefore, a 0.5 mg/mL CDs solution was selected herein. Moreover, upon increasing the pH of PBS, the ΔF increased progressively, reached maximum at pH = 6.5, and then decreased. Thus, PBS (pH = 6.5) was used as the aqueous medium for Cr(VI) detection (Fig. 4B). Fig. 4C shows that temperatures within the range of 15−65 °C influence the fluorescence intensity of CDs; therefore, 37 °C was selected as the test temperature. In addition, the effect of the reaction time on Cr(VI) detection is shown in Fig. 4D. Within 25 min, the fluorescence quenching intensity reached a quenching equilibrium. Hence, 25 min was identified to be the incubation time for Cr(VI).

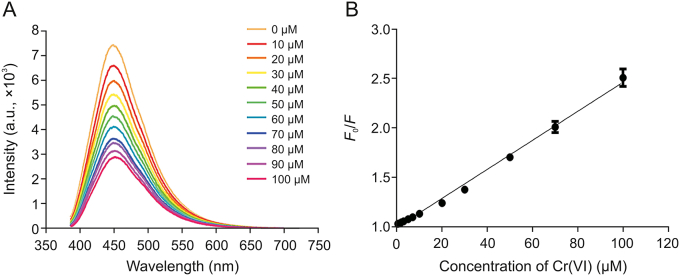

3.4. Fluorescence sensing of Cr(VI)

To explore the selectivity of the sensor system and the influence of different ions on the fluorescence intensity of CDs, each metal ion of 100 μM was added to 0.5 mg/mL CD solution under optimal experimental conditions. The reaction system was then placed in a PBS with a pH of 6.5 at 37 °C and incubated for 25 min. As shown in Fig. 5, CDs show significant fluorescence reduction in Cr(VI) in the presence of various metal ions, indicating that CDs have good selectivity and a unique effect on Cr(VI). To study the sensitivity of Cr(VI) further, Fig. 6A shows the fluorescence spectra of CDs after adding different concentrations of Cr(VI). When the concentration of Cr(VI) was increased, the PL strength of CDs decreased continuously, confirming the applicability of Cr(VI) as a “turn-off” fluorescent probe. Fig. 6B suggests a good linear relationship between Cr(VI) concentration and the PL strength of CDs in the range of 1–100 μM. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.9942. The detection limit of Cr(VI) was 0.25 μM calculated using 3δ/k (δ stands for the standard deviation of 11 blank samples, and k is the slope of the calibration curve). The detection limit of our fluorescent probe is below the World Health Organization (WHO)'s maximum limit of 50 μg/L in drinking water [20]. Furthermore, some performance comparisons of the proposed method with other published analytical techniques are provided in Table 1 [[2], [43], [46], [47], [48]]. The results showed that our sensor provided an acceptable method for the detection of Cr(VI) with a wide detection range and low detection limit under optimal operating conditions.

Fig. 5.

Selectivity of the CDs (0.5 mg/mL) for Cr(VI) and various common metal ions (100 μM) in PBS (0.01 M, pH 6.5).

Fig. 6.

(A) Photoluminescence (PL) emission spectra of the CDs in the presence of different concentrations of Cr(VI) (from 0 to 100 μM). (B) The linear plots of F0/F versus the concentration of Cr(VI) in the range from 1 to 100 μM (F0 and F represent the PL intensity of the initial and added Cr(VI), respectively).

Table 1.

CDs prepared herein were compared with Cr(VI) detection performance previously reported in the literature.

| Probe | Linear range (μM) | LOD (μM) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-dots | 80–1000 | 140 | [46] |

| NPS-CDs | 1–500 | 0.23 | [43] |

| CG-CDs | 5–200 | 4.16 | [47] |

| CDs | 0.5–263 | 0.26 | [48] |

| CCDs | 5–125 | 1.17 | [2] |

| CDs | 1–100 | 0.25 | This work |

C-dots: carbon quantum dots; NPS-CDs: nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur tri-doped carbon dots; CG-CDs: carbon dots from citric acid and glycine; CCDs: cobalt(II)-doped carbon dots.

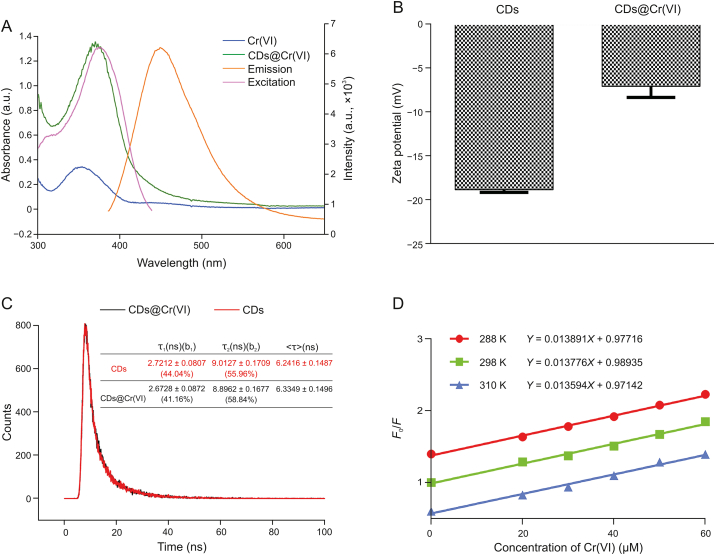

3.5. Mechanism for detecting Cr(VI) by CDs

To explore the fluorescence quenching mechanism of CDs by Cr(VI), the fluorescence excitation spectra (purple) and emission spectra (orange) of CDs and UV–vis absorbance spectrum of Cr(VI) (blue) and CDs@Cr(VI) (green) were investigated (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 7A, the UV–vis absorption peaks of Cr(VI) and CDs@Cr(VI) were obvious at 352 and 368 nm and CDs exhibited excitation and emission peaks at 376 and 450 nm, respectively. The results showed that the absorption spectrum of Cr(VI) substantially overlapped with the excitation spectrum of CDs and led to a part of the excitation light to CDs being absorbed and shielded by Cr(VI). Thus, the IFE occurred and the fluorescence of CDs could be successfully quenched by Cr(VI). With the introduction of Cr(VI), the zeta potential of aqueous solutions of CDs (Fig. 7B) ranged from −18.8 to −7.06 mV, possibly owing to Cr(VI) binding to carboxyl or hydroxyl groups and the consumption of negative charges. As shown in Fig. 7C, no obvious changes in the lifetime indicate that the fluorescence quenching of CDs by Cr(VI) is attributed to the static quenching effect. To investigate the FL quenching mechanism further, the FL quenching data were analyzed using a Stern–Volmer (SV) plot because both static quenching and dynamic quenching can be theoretically described using the SV equation (2)

| (2) |

where and are the fluorescence intensities of the fluorophore in the absence and presence of the quencher, is the SV quenching constant, and is the concentration of the quencher. and represent the quenching rate and the fluorescence lifetime in the presence of a quenchless agent, respectively.

Fig. 7.

(A) Overlapping of the absorption spectrum of Cr(VI) and CDs@Cr(VI) with the emission and excitation of CDs. (B) Zeta potential values of the CDs and CDs@Cr(VI). (C) Fluorescence decay traces of CDs and CDs@Cr(VI). (D) Stern–Volmer curve for CDs@Cr(VI) system.

As shown in Fig. 7D, the FL intensity ratio (F0/F) is linear.

| F0/F = 0.97716 + 0.013891[Cr(VI)], R2 = 0.9965, T = 288 K |

| F0/F = 0.98935 + 0.013776[Cr(VI)], R2 = 0.9919, T = 298 K |

| F0/F = 0.97142 + 0.013594[Cr(VI)], R2 = 0.9903, T = 310 K |

Thus, decreased with increase in temperature, was 6.24 ns, and the (2.1785 × 1012 L/(mol∙s), 37 °C) was much higher than the maximum collision quenching constant (2.0 × 1010 L/(mol∙s) [49]), which further proves the existence of a static quenching process rather than a dynamic quenching process.

3.6. Cr(VI) detection in real samples

Standard recovery experiments were performed using tisanes, rainwater, and river water samples to determine whether the CD fluorescence method could be used to determine Cr(VI) concentrations in actual samples. Each water sample was passed through a 0.22-μm micropore membrane filter and was then centrifuged at 10,000 r/min for 10 min before being analyzed. As shown in Table 2, the experimental results showed that recoveries of Cr(VI) reached 94.37%–100.19%, 86.06%–96.13%, and 82.52%–117.73% with the relative standard deviation (RSD) of 0.27%–2.69%, 0.97%–1.52%, and 1.18%–1.77%, all of which were less than 5%. According to the WHO, the permitted limit for Cr(VI) in drinking water is 0.05 mg/L (approximately 1 μM), suggesting that CDs can be used for quantitative detection of Cr(VI) [50].

Table 2.

Determination of Cr(VI) in actual water samples.

| Samples | Spiked (μM) | Founda(μM) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) (n=3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tisanes | 20 | 18.87 | 94.37 | 2.69 |

| 40 | 38.58 | 96.46 | 1.58 | |

| 60 | 60.12 | 100.19 | 0.27 | |

| Rainwater | 20 | 17.21 | 86.06 | 1.52 |

| 40 | 38.65 | 96.63 | 0.97 | |

| 60 | 57.68 | 96.13 | 1.24 | |

| River water | 20 | 16.50 | 82.52 | 1.20 |

| 40 | 38.51 | 96.29 | 1.77 | |

| 60 | 70.63 | 117.73 | 1.18 |

The mean of three measurements.

3.7. CD cytotoxicity evaluation

To develop fluorescent carbon quantum dot probes for in vitro cellular imaging and intracellular Cr(VI) monitoring, the cytotoxicity of CDs was researched through the traditional MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 8, the cell viabilities of HepG2 cells were higher than 80% even when these cells were incubated with 2.0 mg/mL of CDs for as long as 24 h. The results showed that CDs had low cytotoxicity, which provides a basis for the biological application of CDs.

Fig. 8.

Determination of cytotoxicity of CDs using the MTT assay.

4. Conclusions

To sum up, a simple one-step hydrothermal method for the synthesis of carbon quantum dots with blue fluorescence emission was established with Poria cocos polysaccharide as the precursor. Carbon quantum dots show excellent fluorescence performance due to static quenching and internal filtering effects, so Cr(VI) can quench the fluorescence intensity of CDs. Therefore, a fluorescence analysis platform for the detection of Cr(VI) has been established, which can be used for the sensitive and selective detection of Cr(VI) in real samples, with satisfactory results and broad application prospects in environmentally and biologically related fields. In addition, carbon quantum dots with fluorescence probe detection performance were synthesized with nonpharmacologically active Poria cocos polysaccharide as the precursor because it can be easily obtained in a high volume and is inactive. Therefore, this precursor can be used in ion detection after modification to broaden the application range of nonpharmacologically active Chinese medicine component nanoparticles.

CRediT author statement

Qianqian Huang: Writing - Original draft preparation, Methodology, Software, Conceptualization; Qianqian Bao: Visualization, Investigation; Chengyuan Wu: Visualization, Investigation; Mengru Hu: Data curation; Yunna Chen: Data curation; Lei Wang: Supervision; Weidong Chen: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine (Grant No.: 2018zrzd04), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No.: 1908085QH351), Major Science and Technology Projects of Anhui Province (Grant No.: 18030801131), National Key Research and Development Project (Grant No.: 2017YFC1701600), and Anhui Province's Central Special Fund for Local Science and Technology Development (Grant No.: 201907d07050002).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Contributor Information

Lei Wang, Email: wanglei@ahtcm.edu.cn.

Weidong Chen, Email: wdchen@ahtcm.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhang H., Huang Y., Hu Z., et al. Carbon dots codoped with nitrogen and sulfur are viable fluorescent probes for chromium(Ⅵ) Microchim. Acta. 2017;184:1547–1553. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang H.-Y., Wang Y., Xiao S., et al. Rapid detection of Cr(Ⅵ) ions based on cobalt(Ⅱ)-doped carbon dots. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017;87:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu L., Peng X., Li H., et al. On–off–on fluorescent silicon nanoparticles for recognition of chromium(Ⅵ) and hydrogen sulfide based on the inner filter effect. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017;238:196–203. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang S., Jin L., Liu J., et al. A label-free yellow-emissive carbon dot-based nanosensor for sensitive and selective ratiometric detection of chromium (Ⅵ) in environmental water samples. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020;248 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nghia N.N., Huy B.T., Lee Y.I. Colorimetric detection of chromium(Ⅵ) using graphene oxide nanoparticles acting as a peroxidase mimetic catalyst and 8-hydroxyquinoline as an inhibitor. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:36. doi: 10.1007/s00604-018-3169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tai D., Liu C., Liu J. Facile synthesis of fluorescent carbon dots from shrimp shells and using the carbon dots to detect chromium(Ⅵ) Spectrosc. Lett. 2019;52:194–199. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ming F., Hou J., Hou C., et al. One-step synthesized fluorescent nitrogen doped carbon dots from thymidine for Cr (Ⅵ) detection in water. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;222 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M., Shi R., Gao M., et al. Sensitivity fluorescent switching sensor for Cr (Ⅵ) and ascorbic acid detection based on orange peels-derived carbon dots modified with EDTA. Food Chem. 2020;318 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravindran A., Elavarasi M., Prathna T.C., et al. Selective colorimetric detection of nanomolar Cr (Ⅵ) in aqueous solutions using unmodified silver nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012;166–167:365–371. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo J.-F., Huo D.-Q., Yang M., et al. Colorimetric detection of Cr (Ⅵ) based on the leaching of gold nanoparticles using a paper-based sensor. Talanta. 2016;161:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korshoj L.E., Zaitouna A.J., Lai R.Y. Methylene blue-mediated electrocatalytic detection of hexavalent chromium. Anal. Chem. 2015;87:2560–2564. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin W., Wu G., Chen A. Sensitive and selective electrochemical detection of chromium(Ⅵ) based on gold nanoparticle-decorated titania nanotube arrays. Analyst. 2014;139:235–241. doi: 10.1039/c3an01614e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H., Du P., Chen J., et al. Separation and preconcentration system based on ultrasonic probe-assisted ionic liquid dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction for determination trace amount of chromium(Ⅵ) by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry. Talanta. 2010;81:176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiran K., Kumar K.S., Prasad B., et al. Speciation determination of chromium(Ⅲ) and (Ⅵ) using preconcentration cloud point extraction with flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS) J. Hazard Mater. 2008;150:582–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yilmaz E., Soylak M. Ultrasound assisted-deep eutectic solvent based on emulsification liquid phase microextraction combined with microsample injection flame atomic absorption spectrometry for valence speciation of chromium(Ⅲ/Ⅵ) in environmental samples. Talanta. 2016;160:680–685. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagendorfer H., Goessler W. Separation of chromium(Ⅲ) and chromium(Ⅵ) by ion chromatography and an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer as element-selective detector. Talanta. 2008;76:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roig-Navarro A.F., Martinez-Bravo Y., López F.J., et al. Simultaneous determination of arsenic species and chromium(VI) by high-performance liquid chromatography–inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2001;912:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajesh N., Jalan R.K., Hotwany P. Solid phase extraction of chromium(Ⅵ) from aqueous solutions by adsorption of its diphenylcarbazide complex on an Amberlite XAD-4 resin column. J. Hazard Mater. 2008;150:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Y., Chen Y., Liu J., et al. Ratiometric fluorescent detection of chromium(Ⅵ) in real samples based on dual emissive carbon dots. Talanta. 2018;185:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Fang X., Zhao H., et al. A highly sensitive and selective detection of Cr(Ⅵ) and ascorbic acid based on nitrogen-doped carbon dots. Talanta. 2018;181:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang S., Qiu H., Zhu F., et al. Graphene quantum dots as on-off-on fluorescent probes for chromium(Ⅵ) and ascorbic acid. Microchim. Acta. 2015;182:1723–1731. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng S., Gao Z., Liu H., et al. Feasibility of detection valence speciation of Cr(Ⅲ) and Cr(Ⅵ) in environmental samples by spectrofluorimetric method with fluorescent carbon quantum dots. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;212:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y., Duan W., Song W., et al. Red emission B, N, S-co-Doped carbon dots for colorimetric and fluorescent dual mode detection of Fe3+ ions in complex biological fluids and living cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:12663–12672. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L., Shi L., Jia J., et al. Fe3+detection, bioimaging, and patterning based on bright blue-fluorescent N-doped carbon dots. Analyst. 2020;145:5450–5457. doi: 10.1039/d0an01042a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng M., Li Y., Liu S., et al. One-Pot to synthesize multifunctional carbon dots for near infrared fluorescence imaging and photothermal cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:23533–23541. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b07453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao M., Xia C., Xia J., et al. A yellow carbon dots-based phosphor with high efficiency for white light-emitting devices. J. Lumin. 2019;206:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y., Gao Z., Yang X., et al. Fish-scale-derived carbon dots as efficient fluorescent nanoprobes for detection of ferric ions. RSC Adv. 2019;9:940–949. doi: 10.1039/c8ra09471c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atchudan R., Edison T.N.J.I., Perumal S., et al. Betel-derived nitrogen-doped multicolor carbon dots for environmental and biological applications. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;296 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu Y., Li C., Chen C., et al. Saccharomyces-derived carbon dots for biosensing pH and vitamin B 12. Talanta. 2019;195:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn J., Song Y., Kwon J., et al. Food waste-driven N-doped carbon dots: applications for Fe3+ sensing and cell imaging. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019;102:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun X., He J., Yang S., et al. Green synthesis of carbon dots originated from Lycii Fructus for effective fluorescent sensing of ferric ion and multicolor cell imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2017;175:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu D., Huang X., Deng X., et al. Preparation of photoluminescent carbon nanodots by traditional Chinese medicine and application as a probe for Hg2+ Anal. Methods. 2013;5:3023–3027. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azizi M., Valizadeh H., Shahgolzari M., et al. Synthesis of self-targeted carbon dot with ultrahigh quantum yield for detection and therapy of cancer. ACS Omega. 2020;5:24628–24638. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie Y., Cheng D., Liu X., et al. Green hydrothermal synthesis of N-doped carbon dots from biomass highland barley for the detection of Hg2+ Sensors (Basel) 2019;19:3169. doi: 10.3390/s19143169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L., Zhang Z., Gao Z., et al. Facile synthesis of N,B-co-doped carbon dots with the gram-scale yield for detection of iron (Ⅲ) and E. coli. Nanotechnology. 2020;31 doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ab9b4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhunia S.K., Maity A.R., Nandi S., et al. Imaging cancer cells expressing the folate receptor with carbon dots produced from folic acid. Chembiochem. 2016;17:614–619. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng J., Gao W., Gupta B.K., et al. Graphene quantum dots derived from carbon fibers. Nano Lett. 2012;12:844–849. doi: 10.1021/nl2038979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu S., Cui J., Huang J., et al. Facile one-pot synthesis of highly fluorescent nitrogen-doped carbon dots by mild hydrothermal method and their applications in detection of Cr(Ⅵ) ions. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;206:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atchudan R., Edison T.N.J.I., Aseer K.R., et al. Hydrothermal conversion of Magnolia liliiflora into nitrogen-doped carbon dots as an effective turn-off fluorescence sensing, multi-colour cell imaging and fluorescent ink. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2018;169:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao M., Li Y., Zhao Y., et al. A novel method for the preparation of solvent-free, microwave-assisted and nitrogen-doped carbon dots as fluorescent probes for chromium(Ⅵ) detection and bioimaging. RSC Adv. 2019;9:8230–8238. doi: 10.1039/c9ra00290a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li P., Hong Y., Feng H., et al. An efficient “off-on” carbon nanoparticle-based fluorescent sensor for recognition of chromium(Ⅵ) and ascorbic acid based on the inner filter effect. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:2979–2988. doi: 10.1039/c7tb00017k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang L., Zhang L., Chen Z., et al. Ammonium citrate derived carbon quantum dot as on-off-on fluorescent sensor for detection of chromium(Ⅵ) and sulfites. Mater. Lett. 2017;191:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang S., Yang E., Yao J., et al. Nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur tri-doped carbon dots are specific and sensitive fluorescent probes for determination of chromium(Ⅵ) in water samples and in living cells. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:851. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3941-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hua J., Jiao Y., Wang M., et al. Determination of norfloxacin or ciprofloxacin by carbon dots fluorescence enhancement using magnetic nanoparticles as adsorbent. Microchim. Acta. 2018;185:137. doi: 10.1007/s00604-018-2685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang R., Wang X., Sun Y. One-step synthesis of self-doped carbon dots with highly photoluminescence as multifunctional biosensors for detection of iron ions and pH. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017;241:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu K.-H., Lin J.-H., Lin C.-Y., et al. A fluorometric paper test for chromium(Ⅵ) based on the use of N-doped carbon dots. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:227. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H., Liu S., Xie Y., et al. Facile one-step synthesis of highly luminescent N-doped carbon dots as an efficient fluorescent probe for chromium(Ⅵ) detection based on the inner filter effect. New J. Chem. 2018;42:3729–3735. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao Y., Jiao Y., Lu W., et al. Carbon dots with red emission as a fluorescent and colorimeteric dual-readout probe for the detection of chromium(Ⅵ) and cysteine and its logic gate operation. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2018;6:6099–6107. doi: 10.1039/c8tb01580e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Q., Liang J., Han H. Probing the interaction of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with bovine serum albumin by spectroscopic techniques. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:10454–10458. doi: 10.1021/jp904004w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bauer G., Neouze M.-A., Limbeck A. Dispersed particle extraction—a new procedure for trace element enrichment from natural aqueous samples with subsequent ICP-OES analysis. Talanta. 2013;103:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]