Abstract

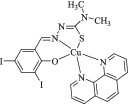

Two new mixed‐ligand complexes with general formula [Cu(SB)(L')]ClO4 (1 and 2) were synthesized and characterized by different spectroscopic and analytical techniques including Fourier transform infrared (FT‐IR) and UV–Vis spectroscopy and elemental analyses. The SB ligand is an unsymmetrical tridentate NN'O type Schiff base ligand that was derived from the condensation of 1,2‐ethylenediamine and 5‐bromo‐2‐hydroxy‐3‐nitrobenzaldehyde. The L' ligand is pyridine in (1) and 2,2′‐dimethyl‐4,4′‐bithiazole (BTZ) in (2). Crystal structure of (2) was also obtained. The two complexes were used as anticancer agents against leukemia cancer cell line HL‐60 and showed considerable anticancer activity. The anticancer activity of these complexes was comparable with the standard drug 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU). Molecular docking and pharmacophore studies were also performed on DNA (PDB:1BNA) and leukemia inhibitor factor (LIF) (PDB:1EMR) to further investigate the anticancer and anti‐COVID activity of these complexes. The molecular docking results against DNA revealed that (1) preferentially binds to the major groove of DNA receptor whereas (2) binds to the minor groove. Complex (2) performed better with 1EMR. The experimental and theoretical results showed good correlation. Molecular docking and pharmacophore studies were also applied to study the interactions between the synthesized complexes and SARS‐CoV‐2 virus receptor protein (PDB ID:6LU7). The results revealed that complex (2) had better interaction than (1), the free ligands (SB and BTZ), and the standard drug favipiravir.

Keywords: anticancer, COVID‐19, mixed‐ligand, molecular docking, unsymmetrical Schiff base

Two new mixed‐ligand Schiff base complexes were synthesized and characterized and were studied as anticancer and anti‐COVID‐19 agents by experimental and/or computational methods including molecular docking and pharmacophore modeling.

1. INTRODUCTION

Schiff base ligands and their transition metal complexes have played a great role in the design and development of metallodrugs.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ] These ligands and complexes are, to some extent, easily synthesized and their structural and electronic features could be smoothly tuned by the presence of various substituents. From a different point of view, mixed‐ligand strategy also provides a new route to the synthesis of unique complexes with tuned stereo‐electronic characteristics. In this regard, the synthesis of mixed‐ligand Schiff base complexes could provide a distinctive opportunity for the study of a variety of complexes with special applications.

Thiazoles are heterocyclic compounds that contain both sulfur and nitrogen in the same ring. Thiazoles are bioactive materials that are found in a wide range of drugs and natural molecules.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] Thiamine is perhaps the most well‐known compound containing thiazole ring,[ 11 ] but other important compounds such as dasatinib (used for treatment of leukemia),[ 12 ] bleomycin and its analogues (used for treatment of different cancers),[ 13 ] sulfathiazole and sulfamethizole (used as antibiotics),[ 14 ] and pramipexole (antidepressant)[ 15 ] are also known.

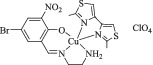

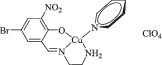

We have previously synthesized a series of mixed‐ligand Schiff base complexes[ 16 , 17 , 18 ] and have studied their antibacterial properties. Those complexes had the general formula [Cu(SB)(L')]ClO4, in which the SBs were unsymmetrical tridentate NN'O type Schiff base ligands and the L's were either pyridine or bipyridine/phenanthroline derivatives. The interesting features of the Schiff base ligands, along with the bithiazole ligands and their complexes, have motivated us to synthesize a series of new complexes that contain both of these ligands. Hence, herein, we report the synthesis and characterization of two new mixed‐ligand Schiff base complexes with the same general formula, in which the SB is the Schiff base ligand derived from the condensation of 5‐bromo 2‐hydroxy 3‐nitrobenzaldehyde with ethylenediamine and the co‐ligand L' is pyridine in (1) or 2,2′‐dimethyl‐4,4′‐bithiazole (which will be abbreviated as Btz) in (2) (Scheme 1). The crystal structure of (2) was also obtained. The two complexes were studied as anticancer agent against HL‐60 leukemia cell line and showed considerable activity that is comparable with the standard drug 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU). Molecular docking and pharmacophore studies were also performed to further investigate the anticancer properties of the studied complexes and their corresponding free ligands. The theoretical and experimental results show good correlation.

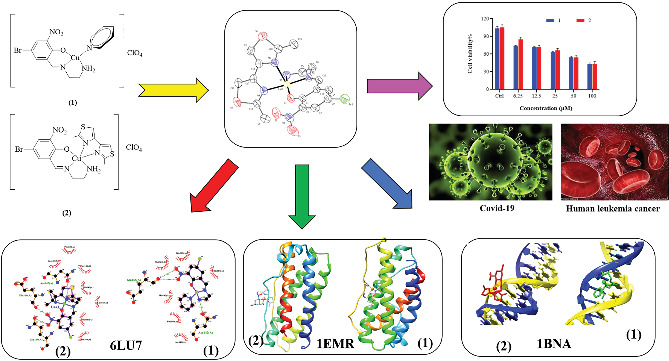

SCHEME 1.

Schematic representation of the synthesis of complexes (1) and (2)

From a different point, designing new drugs for the COVID‐19 pandemic and the investigation of their inhibitory action could effectively accelerate the drug discovery.[ 19 ] SARS‐CoV‐2, also known as 2019‐nCoV, is a novel coronavirus that originated in Wuhan, China, and swept the globe in late 2019.[ 20 , 21 , 22 ] COVID‐19 was the disease caused by the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus, and it was similar to diseases caused by past coronavirus epidemics, such as SARS‐CoV[ 23 ] and MERS.[ 24 ] It presents as a dry cough, fever, exhaustion, and a loss of smell or taste in the respiratory system. In this regard, herein, we report the use of molecular docking and pharmacophore studies to investigate the interaction of the synthesized complexes and the corresponding free ligands with SARS‐CoV‐2 virus receptor protein (PDB ID:6LU7).[ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ] The results revealed that complex (2) had better interaction than (1), the free ligands (SB and BTZ), and the standard drug favipiravir.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1. Materials and instrumentation

1,2‐Ethylenediamine, 5‐bromo‐2‐hydroxybenzaldehyde, and the solvents were purchased from Merck Millipore. Cu(ClO4)2·6H2O was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. These chemicals were used as received. 5‐Bromo‐2‐hydroxy‐3‐nitrobenzaldehyde was synthesized as described elsewhere.[ 29 , 30 ] 2,2′‐Dimethyl‐4,4′‐bithiazole was also synthesized following a literature procedure.[ 31 ] Fourier transform infrared (FT‐IR) spectra were obtained as KBr pellets by a Bruker FT‐IR instrument. UV–Vis spectra were recorded by a Shimadzu UV‐1650 PC spectrophotometer. Elemental analyses were performed on a Perkin‐Elmer 2400II CHNS‐O analyzer.

2.1.1. X‐ray crystallography

SCXRD data were collected on a MAR345 dtb diffractometer equipped with an image plate detector using Mo‐Kα X‐ray radiation. The structure was solved by direct methods using SHELXS‐97 and refined using the full‐matrix least‐squares method on F2, SHELXL‐2016. All non‐hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. The structure was deposited in Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center with deposition number CCDC 2089608.

2.1.2. Cell proliferation and viability assay

The human leukemia cancer cells (HL‐60) were maintained in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum and a pen strep antibiotic (100 μg ml−1 of penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 of streptomycin), and this test was performed at 37°C with a humid atmosphere in a CO2 incubator. When cancer cells reached 80% confluence, they could be used to treat cancer cells. To perform these experiments, we first prepared stock solutions of the complexes that were diluted in RPMI 1640.[ 32 , 33 ]

For cytotoxicity assessments, cancer cells were incubated at 37°C and were plated in 96‐well plates overnight. Then, 200 μl of the mixture of compounds and culture medium with different concentrations (100, 50, 25, 12.5, and 6.25 μM) were plated in 96‐well plates to investigate inhibition of cell growth for 48 h. These experiments were replicated three times. After the end of treatments and complication incubation, 10 μl of MTT (3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazoliumbromide) (5 mg ml−1) solution in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (5 mg ml−1) was added to each well. Then, the 96‐well plates were covered with aluminum foil and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. After draining the culture medium, 100 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to 96‐well plates. Absorbance values were determined at 570 nm using an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader. Cell viability is expressed using control wells as 100% viability and their absorption values are expressed. The IC50 values were evaluated for the sensitivity of treated compounds.[ 34 , 35 ]

2.1.3. Docking studies

Molecular docking simulation was used for further studying the anticancer activity of the complexes as well as their possible anti‐COVID‐19 activity. The crystal structures of 1BNA (BDNA Dodecamer: right‐handed double‐stranded B helix as rigid molecule with the sequence [5′‐D(CpGpCpGpApApTpTpCpGpCpG)‐3′]), human leukemia inhibitor factor (LIF) as receptor (PDB ID:1emr as rigid molecule), and SARS‐CoV‐2 virus receptor (PDB ID:6LU7 as rigid molecule) protein were downloaded from PubChem. The complex (1) and the free ligands (SB) and (BTZ) were optimized via standard 6‐311G** basis sets that were used for C, H, N, O, and Br atoms whereas the LANL2DZ basis set along with the effective core potential (ECP) functions was employed for Cu. Crystallographic data for complex (2) were taken as a CIF file and converted to the PDB format using Mercury software. The molecular docking simulation and calculations were performed by AutoDock 4.2 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) with AutoGrid 4, meaning all non‐ring torsions were maintained. Primarily, the heteroatoms including water molecules around the duplex were removed using AutoDock tools; Kollman united atom type charges, polar hydrogen atoms, and Gasteiger partial charges were then added to the receptor molecule. All the docking simulations were defined by the use of a grid box with 92 × 124 × 126 Å points with a grid‐point spacing of 0.375 Å for BNA, a grid box with a size of 122 × 98 × 126 Å and a grid‐point spacing of 0.375 Å for LIF, and a grid box with a size of 100 × 86 × 126 Å and a grid‐point spacing of 0.758 Å for 6LU7. In this study, we used a Lamarckian genetic algorithm method. The number of evaluations and the number of genetic algorithm runs were set to 200. We examined the structures and selected the structures with the lowest energy from similar structures. After that, the interactions of BNA, 1EMR, and 6LU7 and their binding modes with compounds were analyzed using the AutoDock program, UCSF Chimera 1.5.1 software, Discovery Studio 3.0 from Accelrys, and DS Visualizer.[ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] Morever, docking studies were performed on all of the complexes and their corresponding ligands for three times and the average ± SD are reported.

2.1.4. Pharmacophore profile

To explain the interactions between the synthesized complexes and standard drugs with 1EMR, DNA, and COVID‐19, a pharmacophore modeling was conducted. Controlling DNA and protein are key components for successful treatment, particularly in cancer cells. Pharmit link (http://pharmit.csb.edu) created this interaction profile. Moreover, the interaction bonds were categorized as H‐bond acceptor (H‐Acc.), H‐bond donor (H‐Don.), and hydrophobic (Hyd).[ 40 ]

2.2. Synthesis of the complexes

2.2.1. Synthesis

Synthesis of unsymmetrical Schiff base ligands with symmetrical aliphatic diamines such as ethylenediamine, propanediamine, and other symmetrical aliphatic diamines is extremely difficult. Attempts to synthesize such unsymmetrical so‐called half‐units usually result in symmetrical tetradentate Schiff base ligands, making the synthesis of their corresponding complexes even more difficult. Many researchers have attempted to discover new synthetic methods for such unsymmetrical Schiff base complexes. We were unable to synthesize free unsymmetrical Schiff base ligands from ethylenediamine, but we were able to apply a template technique that works well for the synthesis of Cu(II) complexes containing the required unsymmetrical NN'O type ligand. The related co‐ligand, pyridine, could be easily replaced with chelating co‐ligands, allowing for the creation of a wide range of Cu(II) complexes.

2.2.2. Synthesis of [Cu(SB)(py)]ClO4 (1)

In a typical experiment, 1.23 g of 5‐bromo‐2‐hydroxy‐3‐nitrobenzaldehyde (5.00 mmol) was dissolved in 30 ml of methanol in a round‐bottom flask. While this solution was being continuously stirred at room temperature, 5 ml of an aqueous solution of Cu(ClO4)2·6H2O (5.00 mmol, 1.85 g) was slowly added, followed by the addition of 0.80 g (10.00 mmol) of pyridine. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h. A total of 0.30 g of 1,2‐ethylenediamine (5.00 mmol) dissolved in 5 ml of methanol was then added dropwise to the reaction mixture. This reaction mixture was further stirred for 3 h without heating and the reaction progress was followed by thin‐layer chromatography (TLC). The green powder precipitate was collected by filtration and washed with diethyl ether and air dried. The yield was 90%. The powder was recrystallized from methanol and needle shaped green pure polycrystals were collected by filtration and air dried. Selected infrared (IR) (cm−1) 3263, 3191, 3139, 3110, 3083, 2977 1635, 1608, 1100, 748, 678, and 624. UV–Vis. 10−5 M of solution in dichloromethane [λ max nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)]: 258 (104,000), 263 (78,700), 382 (36,500), 618 (560). Anal. Calcd for C14H14BrClCuN4O7: C, 31.77; H, 2.67; N, 10.59. Found: C, 31.83; H, 2.70; N, 10.51.

2.2.3. Synthesis of [Cu(SB)(Btz)]ClO4 (2)

A total of 0.14 g (0.33 mmol) of (1) was dissolved in 20 ml of methanol in a round‐bottom flask while being magnetically stirred. Afterwards, 20 ml of a methanolic solution of 2,2′‐dimethyl‐4,4′‐bithiazole (0.66 mmol, 0.12 g) was slowly added to the reaction mixture. The obtained reaction mixture was then heated at 50°C. The reaction progress was checked by TLC, and after 3 h, the dark green powder precipitate was collected by filtration and was washed with 10 ml of diethyl ether and air dried. This solid was recrystallized from methanol/acetonitrile 1:1 solution. The yield was 93%. Selected IR (cm−1) 3294, 3249, 3164, 3105, 1629, 1600, 1529, 1444, 1101, 775, 705, and 622. UV–Vis. 10−5 M of solution in dichloromethane [λ max nm (ε, M−1 cm−1)]: 230 (103,000), 264 (68,000), 404 (9300), 640 (120). Anal. Calcd for C17H17ClBrCuN5O7S2: C, 31.59; H, 2.65; N, 10.83. Found: C, 31.50; H, 2.61; N, 10.91.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1. Synthesis

The synthesis procedure is shown in Scheme 1. The synthesis of unsymmetrical Schiff base ligands from aliphatic diamines is extremely difficult and usually results in symmetrical ligands even when the aldehyde:amine ratio is 1:1 at low temperatures. Hence, we used a modified template method to synthesize the complexes. Complex (1) was prepared by the reaction between ethylenediamine, 5‐bromo‐2‐hydroxy‐3‐nitrobenzaldehyde, Cu(ClO4)2·6H2O, and pyridine in methanol at room temperature. Complex (2) was readily prepared by ligand substitution of the monodentate pyridine co‐ligand by bidentate N‐donor heterocyclic co‐ligand (Btz) in methanol at room temperature.

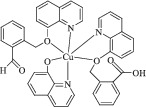

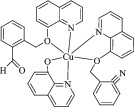

3.2. Crystallographic data collection and determination of the structure of [Cu(SB)(Btz)]ClO4 (2)

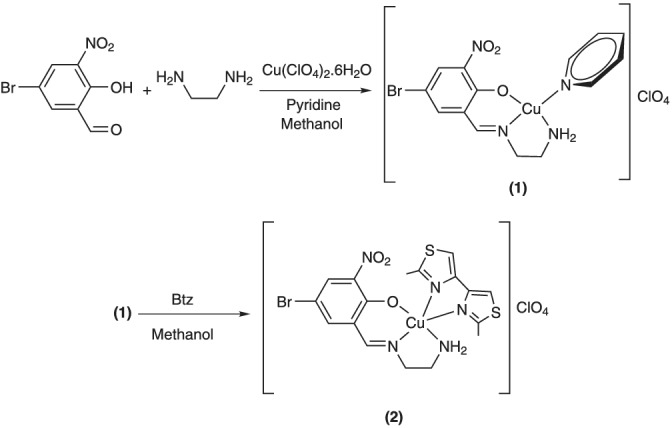

Dark green single crystals were obtained by slow evaporation of methanol/acetonitrile (1:1) solution after several days. Table 1 summarizes the crystallographic data for (2). Selected bond lengths and bond angles around the central metal ion are also collected in Table 2. Figure 1 shows the labeled molecular structure of complex (2) with atom numbering scheme. In the structure of the cationic part of the complexes, an NN'O type unsymmetrical Schiff base ligand exists along with a 2,2′‐dimethyl‐4,4′‐bithiazole co‐ligand. The Schiff base ligand is the mono‐condensed form of the reaction between 1,2‐ethylenediamine and 5‐bromo‐2‐hydroxy‐3‐nitrobenzaldehyde. In this complex, one of the NH2 groups of ethylenediamine moiety is directly coordinated to the metal center, and the other NH2 group is condensed to 5‐bromo‐2‐hydroxy‐3‐nitrobenzaldehyde, forming the unsymmetrical Schiff base ligand. The Schiff base ligand is deprotonated from the O atom of the salicylaldehyde moiety and has a (−1) charge, Hence, the Cu2+ central metal ion's charge is balanced by the presence of one perchlorate anion and the overall charge of the complex is neutral. The central metal ion in (2) is penta‐coordinated and the geometry around the Cu(II) ion is slightly distorted square‐based pyramid (SBP). The trigonality index (τ) that was calculated from is equal to 0.197.[ 41 ] In this equation, β is the greatest angel and α is the second greatest angel. The τ values range from 0 to 1, which corresponds to ideal SBP and trigonal bipyramidal (TBP) structures, respectively. Three of the basal positions in the SBP structure are occupied by the NN'O coordinating atoms of the Schiff base ligand, including N atom from the NH2 group, the N′ from the azomethine group, and the O atom from the phenoxide group. The fourth basal position is occupied by the N atom from the bithiazole ligand. The apical position is also occupied by the other N atom of the bithiazole ligand.

TABLE 1.

Data collection, structure refinement, and crystal data

| Compound | (2) |

|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C17H17BrCuN5O3S2·ClO4 |

| Formula weight | 646.38 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic |

| Space group | P |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å, °) | |

| a (Å) | 9.5383 (19) |

| b (Å) | 10.402 (2) |

| c (Å) | 13.634 (3) |

| α (°) | 77.63 (3) |

| β (°) | 78.25 (3) |

| γ (°) | 83.61 (3) |

| Volume (Å3) | 1290.4 (5) |

| Z | 2 |

| Radiation type | Mo Kα |

| Absorption coefficient (mm−1) | 2.71 |

| Reflections | |

| Unique (R int) | 0.045 |

| Number of parameters | 321 |

| Goodness‐of‐fit on F 2 | 1.08 |

|

R(F) [I > 2σ(I)] wR(F 2) [I > 2σ(I)] |

0.051 0.136 |

| Δρ max, Δρ min (e Å−3) | 0.45, −0.68 |

TABLE 2.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (°) around the central metal ion

| Bond length (Å) | Bond angle (°) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu1—N1 | 2.005(4) | N1—Cu1—N4 | 83.38(16) |

| Cu1—O1 | 1.973(3) | N1—Cu1—N5 | 100.44(14) |

| Cu1—N4 | 2.103(4) | N1—Cu1—N3 | 175.01(14) |

| 1Cu1—N5 | 2.415(4) | O1—Cu1—N1 | 92.38(14) |

| Cu1—N3 | 2.093(4) | O1—Cu1—N4 | 163.21(16) |

| O1—Cu1—N5 | 104.84(14) | ||

| N4—Cu1—N5 | 91.93(15) | ||

| N3—Cu1—N4 | 92.01(16) | ||

| N3—Cu1—N5 | 77.76(14) | ||

FIGURE 1.

Molecular structure of (2) with atom numbering scheme. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and uncoordinated perchlorate anion are omitted for clarity

As could be seen from Table 2, the N1—Cu1—N3 and O1—Cu1—N4 angles are 175.01° and 163.21°, respectively, which shows deviation from ideal SBP structure. The Cu(II) ion is also located about 0.13 Å above the plane defined by the four basal coordinating atoms, which further confirms the mentioned slight deviation from SBP structure. These data are similar to previously published complexes with the same scaffold.[ 16 , 17 , 18 ] Besides, there are two moderate and two weak hydrogen bonds (H. bonds) (N4‐H4A … O5, N4‐H4B … O4, and C11‐H11 … O4, C15‐H15A … O6 with distances D … A of 3.198, 3.220, and 3.496, 3.411 Å, respectively), together with one relatively weak halogen bond of Br1 … O7, 3.263 Å, between perchlorate ions and complexes, stabilizing the 3D crystal structure.

3.3. Description of the IR and UV–Vis spectra of the complexes

As shown in Scheme 1, the three most specific functional groups in the complexes are azomethine (C═N), NH2, and perchlorate anion. The FT‐IR spectrum of the complexes showed signals related to these groups. The sharp bands at 1629 and 1635 cm−1 for complexes (1) and (2) were assigned to the (C═N) stretching vibration. The two bands at around 3300 and 3200 cm−1 correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the NH2 group, respectively. A sharp band at around 1100 cm−1 was also assigned to the stretching vibration of the uncoordinated perchlorate anion.[ 42 ] Other signals such as δ(CCH) of the aromatic rings, aliphatic (CCH) and δ(C═C) were observed at around 3100, 3000, and 1600–1400 cm−1. In the UV–Vis spectra of these complexes, π → π* transitions of the phenyl rings and azomethine groups are observed as two intense bands at about 231 and 264 nm. The other signals above 392 nm could be assigned as the ligand to metal charge transfer (LMCT) transition. The very weak signals above 600 nm, which could only be observed at higher concentrations, were assigned to the d → d transition.[ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]

3.4. Biological studies

3.4.1. Assessment of cytotoxicity using MTT assay

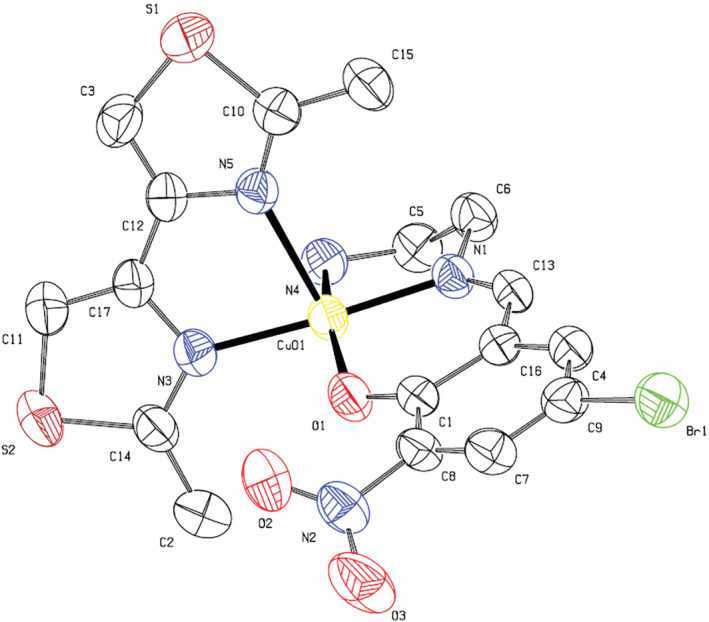

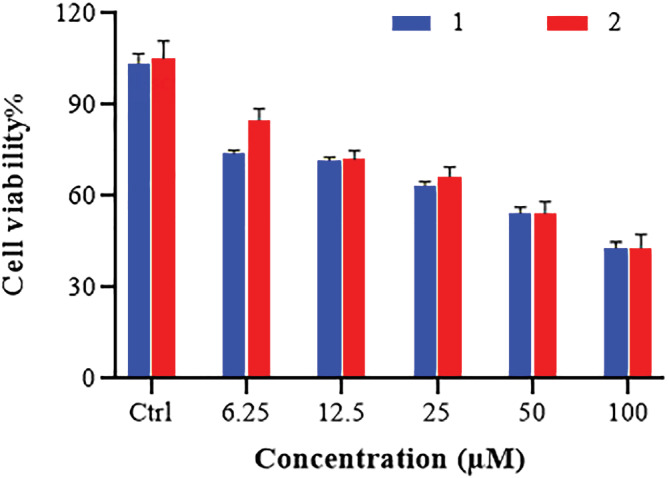

The HL‐60 cell line is a human leukemia cell line that has been used to study blood cell development and physiology in the laboratory. The early detection and treatment of leukemia cancer with appropriate medications such as Schiff base compounds could help reduce the number of leukemia cancer victims. To investigate cytotoxic effects, the compounds were incubated for 48 h against HL‐60 cancer cell line. The charts of dose‐dependent effects of complexes on the viability of each HL‐60 cell line are presented in Figure 2. A logical relationship was found between IC50 and concentration values. In this figure, the cell viability decreased with the increasing concentration of the complexes. These complexes showed good cytotoxic and dose‐dependent activity against HL‐60 cancer cells. Although at higher concentrations, the performance of the two complexes was almost identical, it could be seen that complex (2), which is penta‐coordinated with BTZ ligand, can slightly better destroy cancer cells at lower concentrations. The standard drug was 5‐FU. As you can see in Table 3, the inhibitory concentration of complexes against the HL‐60 cancer cell line and the IC50 value for the complexes were almost similar. The results are also comparable with the standard drug 5‐FU.[ 49 , 50 ]

FIGURE 2.

Dose‐dependent effects of Cu(II) complexes on cell viability of HL‐60 cell line by the MTT assay

TABLE 3.

Inhibitory concentration (IC50, μM) for complexes and the standard drug

| Drugs | IC50, μM ± SD |

|---|---|

| (1) | 66.10 ± 1.88 |

| (2) | 65.06 ± 3.27 |

| 5‐FU | 61.23 ± 2.03 |

Abbreviation: 5‐FU, 5‐fluorouracil.

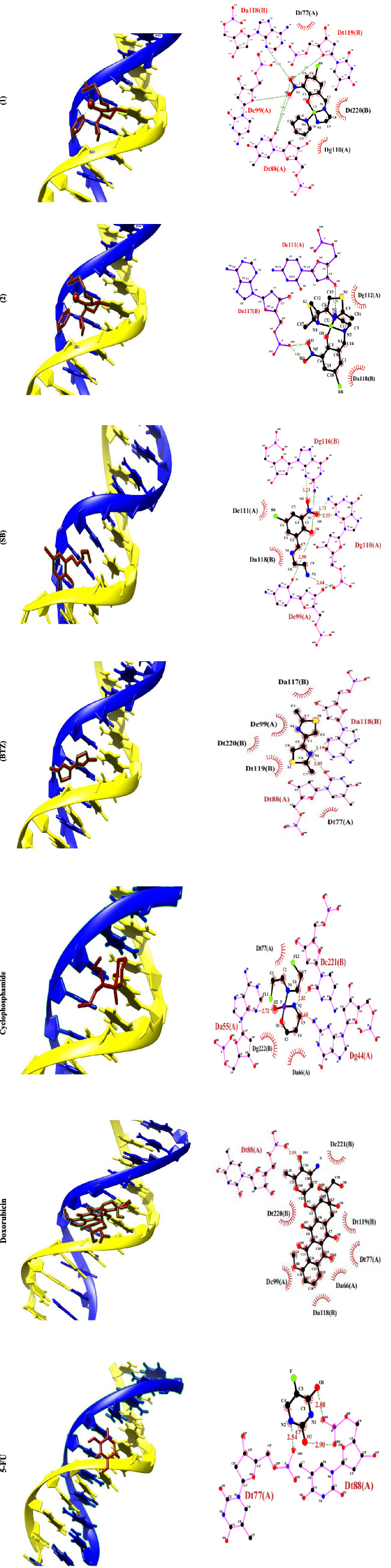

3.4.2. Molecular docking with DNA duplex of sequence (PDB ID:1BNA) as receptor

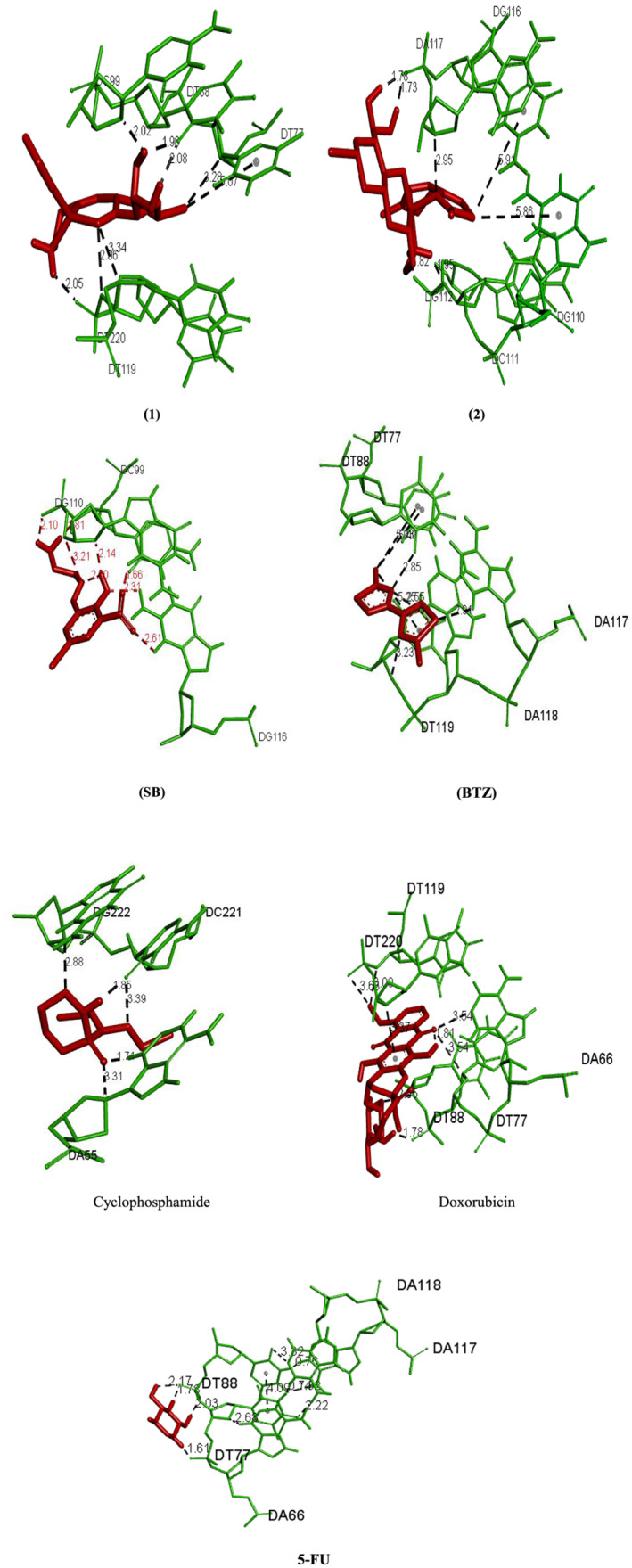

Molecular docking is an attractive tool to investigate the DNA interactions of new compounds and the development of new drugs. Dodecamer sequence (BDNA) is very abundant in natural DNA. These compounds can attach in different modes to a specific binding site of a protein or DNA.[ 51 , 52 ] Computer‐based simulations help us predict the pharmacological action of drugs at the molecular level.[ 26 , 53 , 54 ] The lowest energy conformations were rated based on docking calculations of the lowest free binding energy. The docking results are shown in Figure 3 and are listed in Table 4. The minimum energy of each compound was applied inside the DNA double helix. The standard anticancer chemotherapeutic drugs including cyclophosphamide, 5‐FU, and doxorubicin were also used. The calculated binding free energies (ΔG binding) for the complexes (1 and 2), ligands (SB and BTZ), and drugs to DNA (cyclophosphamide, 5‐FU, and doxorubicin) were −10.10 ± 0.01, −8.39 ± 0.01, −7.95 ± 0.14, −6.37 ± 0.01, −4.66 ± 0.18, −10.90 ± 0.06, and −7.00 ± 0.01 kcal mol−1, respectively, and the binding of the compounds to the DNA was spontaneous. Comparison of the ΔG binding reveals the higher tendency of (1) to bind to DNA among the studied drugs.[ 55 ] The final energy value was calculated from vdW + H‐bond + desolve energy (kcal mol−1), which is related to the formation of H. bonds between the compounds and the receptor. As could be seen from Figure 3, complex (1) and BTZ ligand are located in the major groove of DNA whereas complex (2) and SB ligand are located in the minor groove. The studied standard drugs are also in the major groove and are more compatible with complex (1) in binding with DNA. This could be the reason for slightly better activity of complex (1) than (2). The hydrogen‐bonding interactions of the compounds and binding sites are illustrated in Figure 4. There are four H. bonding interactions between the NH2 group of complex (1) and the phosphate oxygen atoms of DNA helix at 2.05, 2.08, 1.96, and 2.02 Å. On the other hand, complex (2) interacted with DNA through H. bonding with DG112 (1.82, 1.95 Å) and DA117 (1.73, 1.78 Å). Ligand (SB) interacted with DNA through eight H. bonding with DG110 (1.66 Å), DG116 (2.31, 2.60 Å), DC99 (1.81 Å), and DG110 (2.10, 2.13, 3.20 Å), and intermolar bonding was found at 2.19 Å. In BTZ ligand, three H. bonding to DA117 (2.90 Å), DA118 (2.54 Å), DT119 (3.22 Å), DT77 (5.40 Å), DT88 (5.03 Å), and DT119 (5.24 Å) were found. Moreover, cyclophosphamide interacted with groups of cytosine DC110 (1.85 Å), DA55 (2.72 Å), and DA66 (2.73 Å) by forming H. bonds; meanwhile, doxorubicin displayed H. bond interaction with DT220 (3.00, 3.63 Å), DA66, and DT77 (3.54 Å), DT88 (1.78, 2.95 Å). 5‐FU displayed H. bond interaction with DT88 (2.17, 1.78, 2.03 Å) and DT77 (1.61 Å).

FIGURE 3.

Docking conformation and 2D structure of the complexes (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), and anticancer drugs (cyclophosphamide, 5‐fluorouracil [5‐FU], and doxorubicin) to DNA

TABLE 4.

DNA docking results ± SD for (1), (2), free ligands, and the anticancer drugs to DNA (kcal mol−1)

| (1) | (2) | (SB) | (BTZ) | Cyclophosphamide | Doxorubicin | 5‐FU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated free binding energy[ a ] | −10.10 ± 0.01 | −8.39 ± 0.01 | −7.95 ± 0.14 | −6.37 ± 0.01 | −4.66 ± 0.18 | −10.90 ± 0.06 | −7.00 ± 0.01 |

| Final intermolecular energy | −11.29 ± 0.01 | −9.29 ± 0.01 | −9.74 ± 0.14 | −6.66 ± 0.01 | −6.57 ± 0.09 | −14.18 ± 0.05 | −7.60 ± 0.01 |

| vdW + Hbond + desolve energy | −9.10 ± 0.01 | −6.53 ± 0.01 | −6.67 ± 0.31 | −6.64 ± 0.01 | −6.33 ± 0.19 | −11.77 ± 0.27 | −2.22 ± 0.01 |

| Electrostatic energy | −2.19 ± 0.01 | −2.75 ± 0.01 | −3.07 ± 0.46 | −0.02 ± 0.01 | −0.12 ± 0.01 | −2.41 ± 0.30 | −5.38 ± 0.01 |

| Final total internal energy | −1.27 ± 0.02 | −1.36 ± 0.01 | −0.97 ± 0.45 | −0.21 ± 0.01 | −0.64 ± 0.18 | −3.71 ± 0.15 | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

| Torsional free energy | 1.19 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 1.79 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 1.79 ± 0.01 | 3.28 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.01 |

| Unbound system's energy | −1.27 ± 0.02 | −1.36 ± 0.01 | −0.97 ± 0.45 | −0.21 ± 0.01 | −0.64 ± 0.18 | −3.71 ± 0.15 | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

Abbreviation: 5‐FU, 5‐fluorouracil.

ΔG binding = ΔG vdW + hb + desolve + ΔG elec + ΔG total + ΔG tor − ΔG unb.

FIGURE 4.

H. bonding interactions of complexes (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), and anticancer drugs to DNA (cyclophosphamide, 5‐fluorouracil [5‐FU], and doxorubicin)

The drug–receptor residue interactions between the studied complexes, ligands, and standard drugs, with DNA, are summarized in Table 5. The binding of the compounds to the DNA was spontaneous. According to data from density functional theory, positive electron density on the surface of complexes facilitates the metal drug's access to DNA phosphate groups.[ 56 ] The DNA docking data for (1) and (2) indicated that both complexes had a high affinity for binding to the target DNA duplex. In consideration of the interaction strength, however, complex (1) had higher affinity (−10.10 ± 0.01 kcal mol−1) than complex (2) (−8.39 ± 0.01 kcal mol−1). Furthermore, (1) interacted with the DNA binding sites via a H. bond and π‐alkyl hydrophobic interactions. On the other hand, (2) was linked to DNA via π‐sulfur and H. bond interactions. The ligand binding energies were also −7.95 ± 0.14 and −6.37 ± 0.01 for the SB and BTZ, respectively. Compared with copper complexes reported in literature, we found that the presence of withdrawing substitutions such as bromine and nitro groups shows better binding energy, compared with the electron‐donating groups.[ 36 , 57 ]

TABLE 5.

The drug–receptor residue interaction between compounds, with DNA

| Compound | Drug residue | Receptor residue | Type of H for drugs | Type of H for receptor | Interaction | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | NH2 complex | DT220:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.05 |

| H15 aldehyde | DT88:O2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.07 | |

| H16 aldehyde | DT88:O2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.96 | |

| H16 aldehyde | DC99:O4 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.01 | |

| Br aldehyde | DT77:C1 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 3.28 | |

| O aldehyde | DT110:C4 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 3.34 | |

| Br | DA66 | Alkyl | Pi‐orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.02 | |

| Br | DT77 | Alkyl | Pi‐orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.06 | |

| (2) | NH2 complex | DG112:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.81 |

| NH2 complex | DC111:O3 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.95 | |

| H19 aldehyde | DA117:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.78 | |

| H18 aldehyde | DA117:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.72 | |

| N aldehyde | DA117:C4 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 2.94 | |

| S BTZ ligand | DG110 | Sulfur | Pi‐orbitals | π‐Sulfur | 5.85 | |

| S BTZ ligand | DG116 | Sulfur | Pi‐orbitals | π‐Sulfur | 5.91 | |

| (SB) | O ligand | DG110:H3 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 1.66 |

| O ligand | DG116:H21 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.31 | |

| O ligand | DG116:H3 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.60 | |

| NH2 ligand | DC99:O3 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.81 | |

| NH2 ligand | DG110:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.10 | |

| H aldehyde | DG110:O4 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.13 | |

| H aldehyde | N aldehyde | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.19 | |

| N aldehyde | DG110:C5 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 3.20 | |

| (BTZ) | S ligand | DA117:H3 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.90 |

| S ligand | DA118:H3 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.54 | |

| N ligand | DT119:C5 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 3.22 | |

| C ligand | DT77 | Alkyl | π‐Orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.40 | |

| C ligand | DT88 | Alkyl | π‐Orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.03 | |

| C ligand | DT119 | Alkyl | π‐Orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.24 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | O | DA55:H3 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 1.70 |

| H | DC221:O2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.84 | |

| O | DA66:O4 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.73 | |

| O | DA55:C1 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 3.30 | |

| C | DG222:O4 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 2.88 | |

| C | DC221:O2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 3.39 | |

| Doxorubicin | NH2 ligand | O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.80 |

| H | DT81:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.77 | |

| O | DA66:C2 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 3.54 | |

| O | DT71:C1 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 3.54 | |

| O | DT88:C5 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 2.94 | |

| C | DT119:O3 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 2.99 | |

| C | DT220:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 3.62 | |

| Ph ring | DT220:C4 | Pi‐orbitals | C–H | π‐σ | 3.37 | |

| 5‐FU | H | DT88:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.77 |

| H | DT77:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.60 | |

| H4 | DT88:OP1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.17 | |

| H5 | DT88:OP2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.05 |

Abbreviation: 5‐FU, 5‐fluorouracil.

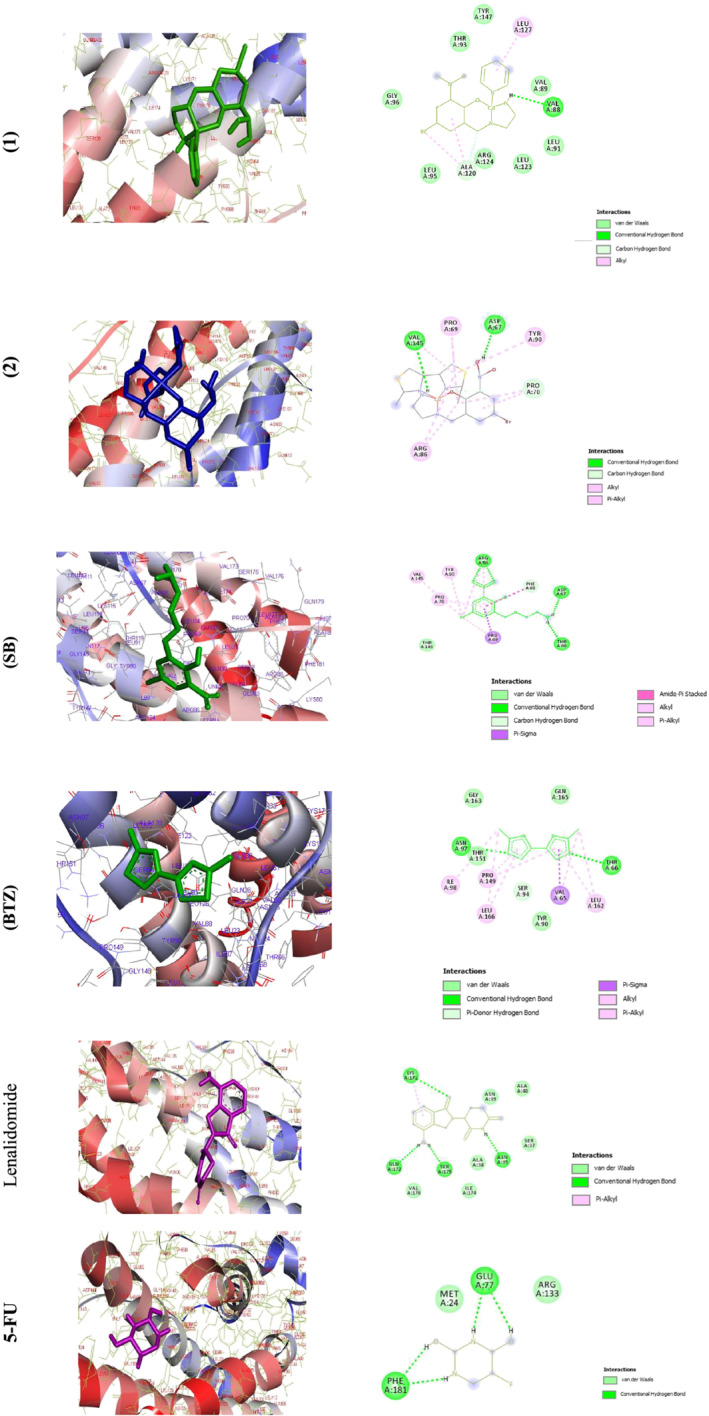

3.4.3. Molecular docking with human LIF protein as receptor (PDB ID:1emr)

LIF was first purified and cloned because of its capacity to induce the differentiation of the M1 murine myeloid leukemia cell line.[ 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 ] In this study, the docking calculations were performed to describe the mode of binding to LIF. The values of docking energies were −7.20 ± 0.04, −8.43 ± 0.01, −7.07 ± 0.20, −5.52 ± 0.01, −7.39 ± 0.08, and −4.60 ± 0.01 kcal mol−1 for (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), lenalidomide, and 5‐FU, respectively (Figure 5 and Table 6). Comparing the relative binding energies (ΔG binding) proved that complex (2) was more effective than (1) and the anticancer compounds (5‐FU and lenalidomide). The order of the binding energies was (2) > (1) > (SB) > (BTZ). The 2D diagrams are shown in Figure 5. The interaction between (1) and LIF was dominated by the H. bond to Val A88. In addition, two hydrogen‐bond interactions are suggested between Val A145 and Asp A67 residue with NH2 and NO2 groups for (2), respectively. The interaction between (SB) and LIF was dominated by the H. bond, C–H. bond, π‐σ‐Hyd., amide‐π‐Hyd., alkyl Hyd., and π‐alkyl Hyd. to ARG86 (four interactions at 1.74, 1.80, 4.90, and 5.48 Å), ASP67 (1.90 and 2.89 Å), THR66 (1.95 Å), N ligand (2.02 Å), PHE68 (3.71 Å), PRO69 (3.61, 3.75, and 4.73 Å), VAL145 (4.63 Å), TYR90 (4.91 Å), and PRO70 (4.47 Å). In ligand (BTZ), two H. bondings between S atom to THR6 and ASN97 were found at 2.85 and 2.73 Å. One π‐Don. H. bond between a ring of the ligand to SER94 was found at 2.76 Å. One π‐σ‐Hyd. bond between a ring of the ligand to VAL65 was found at 3.79 Å. Four alkyl Hyd. bondings between C of the ligand and ILE98, LEU166, VAL65, and LEU162 were found at 4.03, 5.14, 3.93, and 4.95 Å. Four π‐alkyl Hyd. bondings between a ring of the ligand to PRO149 (two), LEU166, and LEU162 were found at 5.06, 4.93, 5.28, and 4.94 Å, respectively. Moreover, further pi‐alkyl bonds were observed for (1), cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin. 5‐FU showed π‐hydrophobic bonds and (2) showed pi‐sulfur bonds. Molecular docking studies by BDNA and 1emr for (1) and (2) proved that the complexes could be potent anticancer agents. The higher tendency of (1) to interact with BDNA and (2) with 1mer may clarify the similar anticancer activity of these complexes but with a different mechanism of actions. The drug–receptor residue interactions between complexes and standard drugs, with 1EMR, are shown in Table 7. As you can see in Table 7, H. bonds and alkyl hydrophobic interactions result in better binding of complexes to proteins. Complex (2) has more protein interactions and also has more negative binding energy.[ 63 ]

FIGURE 5.

Docking conformation of complexes (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), lenalidomide, and 5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU) with LIF

TABLE 6.

Docking results ± SD of (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), and anticancer drugs to LIF (1emr) (kcal mol−1)

| (1) | (2) | (SB) | (BTZ) | Lenalidomide | 5‐FU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated free binding energy[ a ] | −7.20 ± 0.04 | −8.43 ± 0.01 | −7.07 ± 0.20 | −5.52 ± 0.01 | −7.39 ± 0.01 | −4.60 ± 0.01 |

| Final intermolecular energy | −8.39 ± 0.04 | −9.32 ± 0.01 | −8.86 ± 0.20 | −5.81 ± 0.01 | −7.99 ± 0.01 | −5.19 ± 0.01 |

| vdW + Hbond + desolve energy | −7.17 ± 0.04 | −8.87 ± 0.02 | −6.5 ± 0.35 | −5.74 ± 0. 11 | −7.95 ± 0.05 | −2.77 ± 0.04 |

| Electrostatic energy | −1.22 ± 0.02 | −0.44 ± 0.01 | −2.35 ± 0.19 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | −0.03 ± 0.02 | −2.41 ± 0.04 |

| Final total internal energy | −1.93 ± 0.40 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | −0.76 ± 0.04 | −0.23 ± 0.01 | −0.23 ± 0.21 | 0.57 ± 0.01 |

| Torsional free energy | 1.19 ± 0.01 | −0.44 ± 0.01 | 1.79 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.01 |

| Unbound system's energy | −1.93 ± 0.40 | −1.74 ± 0.80 | −0.76 ± 0.04 | −0.23 ± 0.01 | −0.23 ± 0.21 | 0.57 ± 0.01 |

Abbreviation: 5‐FU, 5‐fluorouracil.

ΔG binding = ΔG vdW + hb + desolve + ΔG elec + ΔG total + ΔG tor − ΔG unb.

TABLE 7.

The drug–receptor residue interactions between compounds and 1emr

| Compound | Drug residue | Receptor residue | Type of H for drugs | Type of H for receptor | Interaction | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | NH2 complex | Val88:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.88 |

|

H16 aldehyde O aldehyde |

— | H‐Don., H‐Acc. | — | H. bond | 2.26 | |

| C aldehyde | ALA120:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 3.75 | |

| Aldehyde ring | ALA120 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.59 | |

| Br | ALA120 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 3.26 | |

| Pyridine ring | LEU127 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.86 | |

| (2) | NH2 complex | VAL145:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.15 |

|

H19 aldehyde O aldehyde |

— | H‐Don., H‐Acc. | — | H. bond | 2.14 | |

|

H19 aldehyde N aldehyde |

— | H‐Don., H‐Acc. | — | H. bond | 2.21 | |

| H18 aldehyde | ASP67:OD2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.70 | |

| O aldehyde | PRO70:CD | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 3.63 | |

| BTZ ring | PRO69 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 3.69 | |

| Ring aldehyde | Pro70 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 3.66 | |

| BTZ ring | ARG86 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 5.16 | |

| BTZ ring | VAL145 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 5.27 | |

| C complex | PRO69 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.49 | |

| CH3 BTZ | PRO70 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.65 | |

| CH3 BTZ | ARG86 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 3.24 | |

| BTZ ring | TYR90 | Alkyl | Pi‐orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.14 | |

| (SB) | O ligand | ARG86:HE | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 1.74 |

| O ligand | ARG86:HH11 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 1.80 | |

| NH2 ligand | ASP67:OD2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.90 | |

| NH2 ligand | A:THR66:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.95 | |

| H ligand | N ligand | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.02 | |

| C ligand | ASP67:OD2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 2.89 | |

| C ligand | PHE68:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 3.71 | |

| Ring of ligand | PRO69:CA | π‐Orbital | C–H | π‐σ‐Hyd. | 3.61 | |

| Ring of ligand | PHE68:C,O;PRO69:N | π‐Orbital | Amide | Amide‐π‐Hyd. | 4.73 | |

| Br ligand | PRO69 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 3.75 | |

| Br ligand | ARG86 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.90 | |

| Br ligand | A:VAL145 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.63 | |

| Br ligand | A:TYR90 | Alkyl | π‐Orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.91 | |

| Ring of ligand | A:PRO70 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.47 | |

| Ring of ligand | A:ARG86 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.48 | |

| (BTZ) | S ligand | THR66:HN | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.85 |

| S ligand | ASN97:HD21 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.73 | |

| Ring of ligand | A:SER94:HG | π‐Orbital | H‐Don. | π‐Don. H. bond | 2.76 | |

| Ring of ligand | VAL65:CG1 | π‐Orbital | C–H | π‐σ‐Hyd. | 3.79 | |

| C ligand | ILE98 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.03 | |

| C ligand | LEU166 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 5.14 | |

| C ligand | VAL65 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 3.93 | |

| C ligand | LEU162 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.95 | |

| Ring of ligand | PRO149 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.06 | |

| Ring of ligand | LEU166 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.93 | |

| Ring of ligand | PRO149 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.28 | |

| Ring of ligand | A:LEU162 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.94 | |

| Lenalidomide | O | LYS171:HZ3 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 3.06 |

| H | ASN35:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.96 | |

| H | SER175:OG | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.79 | |

| H | GLN172:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.22 | |

| Ph ring | Lys171 | Pi‐orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.67 | |

| 5‐FU | H | GLU77:OE1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.76 |

| H | PHE181:OXT | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.77 | |

| H4 | GLU77:OE1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.08 | |

| H5 | PHE181:OXT | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.78 |

Abbreviation: 5‐FU, 5‐fluorouracil.

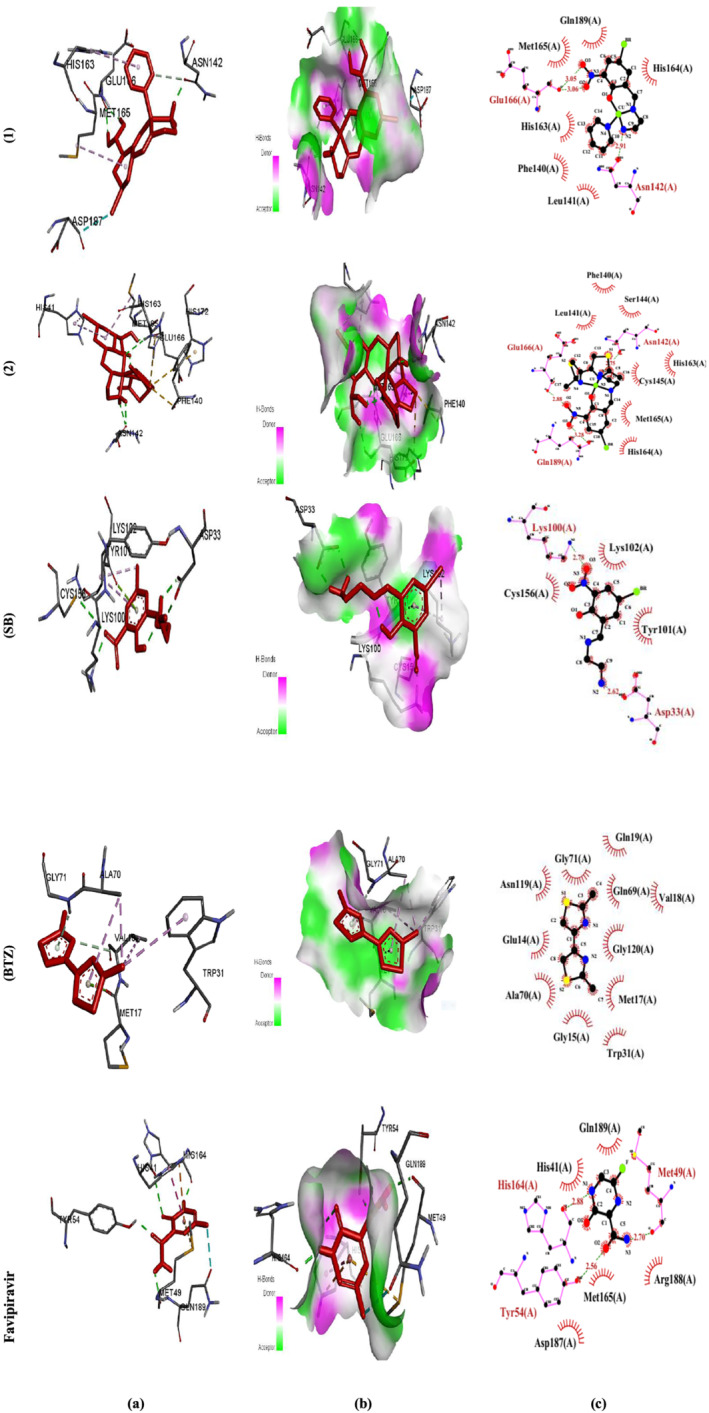

3.4.4. Molecular docking with SARS‐CoV‐2 virus (COVID‐19 disease) as receptor (PDB ID:6LU7) protein

Molecular docking was used to investigate how the complexes interacted with 6LU7 as the receptor protein. The values of docking energies for complexes (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), and favipiravir were −7.58 ± 0.04, −8.28 ± 0.07, −6.25 ± 0.22, −4.98 ± 0.01, and −3.77 ± 0.06 kcal mol−1, respectively (Table 8). Comparing the relative binding energies (ΔG binding) proved that complex (2) was more effective than (1) and the standard drug favipiravir. The order of the binding energies was (2) > (1) > (SB) > (BTZ). The drug–receptor residue interactions between the complexes and favipiravir with 6LU7 are shown in Table 9. In complex (1), three H. bondings between one of the H atoms of the NH2 group as well as the H15 and H16 to ASN142, GLU166 were found at 1.91, 2.12, and 2.06 Å. C–H. bonding between C pyridine and ASN142 was also found at 3.24 Å. Alkyl hydrophobic bonding between phenyl ring from aldehyde moiety and MET165 was observed at 5.24 Å and another alkyl hydrophobic bonding to HIS163 was also found at 5.29 Å. Br to ASP 187 interaction was found at 3.53 Å. In complex (2), six H. bondings between NH2, H18, and H19 to ASN142, GLU166, and BTZ were found at 2.69, 2.51, 2.22, 2.20, 2.13, and 2.10 Å. Two π‐sulfur bondings to HIS163 and HIS172 were found at 4.88 and 5.73 Å and two π‐alkyl hydrophobic bondings to HIS41 were also found at 4.51 and 5.38 Å. In (SB) ligand, five H. bondings between O and H ligand atoms to LYS100, SYS156, ASP33 (two), and N of ligand were found at 1.77, 3.73, 2.00, 1.69, and 1.77 Å. One π‐lone pair bonding between a ring of ligand and TYR101 was found at 2.99 Å. One alkyl Hyd. and π‐alkyl Hyd. to LYS102 were found at 4.24 and 4.75 Å. In (BTZ) ligand, C–H. bond between the N atom to VAL18 was found at 3.78 Å. One π‐donor‐H. bond between a ring of ligand to GLY71 was found at 2.37 Å. One π‐lone pair bond to MET17 was found. Two alkyl Hyd. bonds between C atom to ALA70 and VAL18 were found at 3.49 and 5.40 Å. Two π‐alkyl Hyd. bonds to TRP31 and ALA70 were found at 4.71 and 4.77 Å. The graphical representation of the molecular docking, that is, drugs–receptor H. bond interactions, receptor side surface H. bond interactions, and 2D‐ligand–receptor H. bond interactions, was shown for all of the studied materials[ 64 , 65 ] (Figure 6a–c). Compared with the other copper complexes reported in the literature,[ 66 ] these complexes showed more negative binding energies, which could be attributed to the electron‐withdrawing groups of the aldehyde and BTZ moieties.

TABLE 8.

Docking results ± SD of the compounds (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), and anticancer drugs to 6LU7 (kcal mol−1)

| (1) | (2) | (SB) | (BTZ) | Favipiravir | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated free energy of binding[ a ] | −7.58 ± 0.04 | −8.28 ± 0.07 | −6.25 ± 0.22 | −4.98 ± 0.01 | −3.77 ± 0.06 |

| Final intermolecular energy | −8.78 ± 0.04 | −9.17 ± 0.06 | −7.86 ± 0.51 | −5.28 ± 0.01 | −4.07 ± 0.06 |

| vdW + Hbond + desolve energy | −8.25 ± 0.03 | −8.63 ± 0.06 | −4.45 ± 0.53 | −5.24 ± 0.01 | −4.00 ± 0.09 |

| Electrostatic energy | −0.52 ± 0.01 | −0.54 ± 0.01 | −3.59 ± 0.32 | −0.04 ± 0.01 | −0.07 ± 0.03 |

| Final total internal energy | −1.50 ± 0.06 | −2.37 ± 0.10 | −0.97 ± 0.13 | −0.23 ± 0.01 | −0.23 ± 0.25 |

| Torsional free energy | 1.19 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 1.79 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.01 |

| Unbound system's energy | −1.50 ± 0.06 | −2.37 ± 0.10 | −0.97 ± 0.13 | −0.23 ± 0.01 | −0.23 ± 0.25 |

ΔG binding = ΔG vdW + hb + desolve + ΔG elec + ΔG total + ΔG tor − ΔG unb.

TABLE 9.

The drug–receptor residue interactions between compounds with 6LU7

| Compound | Drug residue | Receptor residue | Type of H for drugs | Type of H for receptor | Interaction | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | NH2 complex | ASN142:OD1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.91 |

| H15 aldehyde | GLU166:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.12 | |

| H16 aldehyde | GLU166:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.06 | |

| C pyridine | ASN142:OD1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | C–H. bond | 3.24 | |

| Br | ASP187:C | Halogen | H‐Acc. | Halogen | 3.53 | |

| Ph ring | MET165 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 5.24 | |

| Py ring | HIS163 | Alkyl | Pi‐orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.29 | |

| (2) | O aldehyde | GLU166:HN | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.69 |

| NH2 complex | ASN142:OD1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.51 | |

| NH2 complex | ASN142:OD1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.22 | |

| H19 aldehyde | GLU166:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.20 | |

| H19 aldehyde | O aldehyde | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.13 | |

| H18 aldehyde | N BTZ | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.10 | |

| S BTZ | PHE140:O | Sulfur | O, N, S | Sulfur‐X | 3.17 | |

| S BTZ | HIS163 | Sulfur | π‐Orbital | π‐Sulfur | 4.88 | |

| S BTZ | HIS 172 | Sulfur | π‐Orbital | π‐Sulfur | 5.73 | |

| Ph ring | MET 165 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.93 | |

| Br | HIS41 | Alkyl | π‐Orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.51 | |

| Ph ring | HIS41 | Alkyl | π‐Orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 5.38 | |

| (SB) | O ligand | LYS100:HZ2 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 1.77 |

| O ligand | CYS156:SG | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 3.73 | |

| H ligand | ASP33:OD2 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.00 | |

| H ligand | ASP33:OD1 | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.69 | |

| H ligand | N ligand | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.77 | |

| Ring of ligand | TYR101:O | π‐Orbital | Lone pair | π‐Lone pair | 2.99 | |

| Br | LYS102 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 4.24 | |

| Ring of ligand | LYS102 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.75 | |

| (BTZ) | N ligand | VAL18:CA | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | C–H. bond | 3.78 |

| Ring of ligand | GLY71:HN | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | π‐Don‐H. bond | 2.37 | |

| Ring of ligand | MET17:O | π‐Orbital | Lone pair | π‐Lone pair | 2.87 | |

| C ligand | ALA70 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 3.49 | |

| C ligand | VAL18 | Alkyl | Alkyl | Alkyl Hyd. | 5.40 | |

| C ligand | TRP31 | Alkyl | π‐Orbital | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.77 | |

| Ring of ligand | A:ALA70 | π‐Orbital | Alkyl | π‐Alkyl Hyd. | 4.71 | |

| Favipiravir | O ligand | HIS41:HD1 | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 2.93 |

| O ligand | TYR54:HH | H‐Acc. | H‐Don. | H. bond | 1.97 | |

| H | HIS164:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 1.98 | |

| H | MET49:O | H‐Don. | H‐Acc. | H. bond | 2.14 | |

| F | GLN189:OE1 | Halogen | Halogen Acc. | Halogen | 3.07 | |

| Ph ring | HIS41:NE2 | Pi‐orbital | Positive | Electrostatic (pi‐cation) | 4.18 | |

| Ph ring | MET49:SD | Pi‐orbital | Sulfur | Π‐Sulfur | 4.59 | |

| Ph ring | HIS41 | Pi‐orbital | Pi‐orbital | Hyd. (π–π stacked) | 3.95 |

FIGURE 6.

Molecular docking results of (1), (2), (SB), (BTZ), and favipiravir with 6LU7. (a) Molecular docking, (b) H. bond receptor‐side surface interactions, and (c) 2D diagram representation

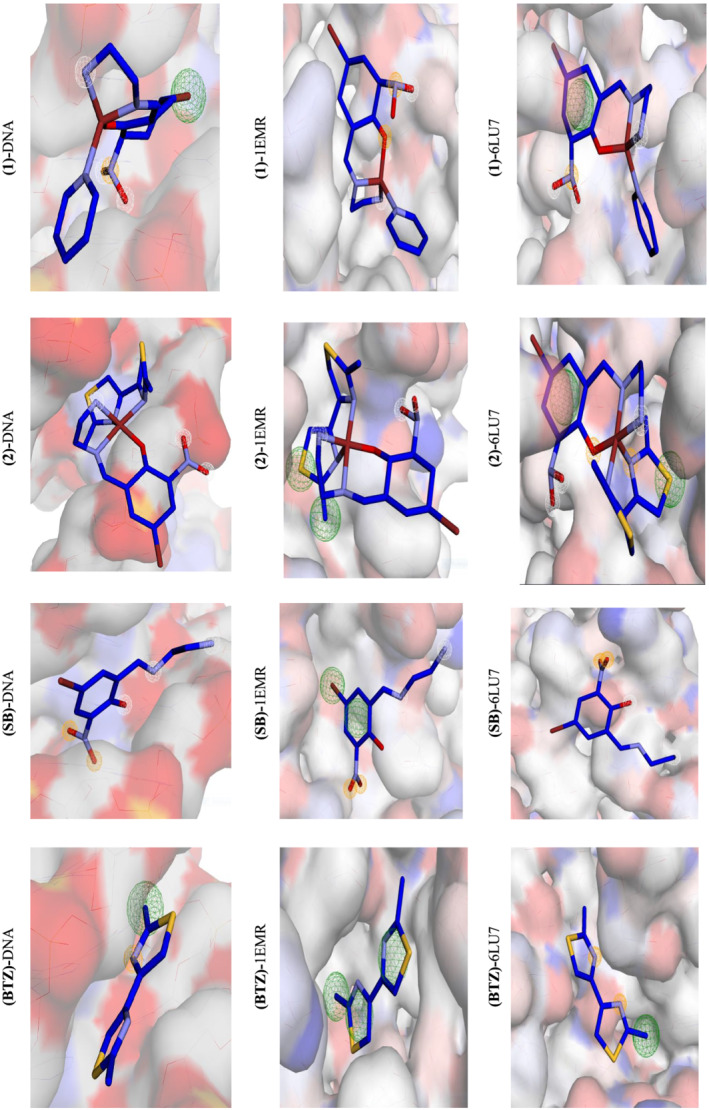

3.4.5. Pharmacokinetics studies

Using the AutoDock 4.2 program, pharmacophore modeling for the Schiff base drugs was created. To find pharmacophore modeling, we used the pharmit website (http://pharmit.csb.edu). (1) and (2) were saved as PDB files and then imported into the pharmit as a ligand to be docked with DNA, 6LU7, and 1EMR. All of the studied chemicals interacted well with DNA, 6LU7, and 1EMR protein pockets as shown in Figure 7. The number of bonds counted with 1EMR, 6LU7, and DNA appeared as follows[ 67 ]:

FIGURE 7.

Interaction profile according to pharmacophore study of the complexes (1), (2), (SB), and (BTZ)

With DNA: (1) H‐donor = 3, H‐acceptor = 0, hydrophobic = 1; (2) H‐donor = 3, H‐acceptor = 0, hydrophobic = 1; (SB) H‐donor = 3, H‐acceptor = 3, hydrophobic = 0; and (BTZ) H‐donor = 0, H‐acceptor = 1, hydrophobic = 1.

With 1EMR: (1) H‐donor = 2, H‐acceptor = 3, hydrophobic = 0; (2) H‐donor = 3, H‐acceptor = 1, hydrophobic = 2; (SB) H‐donor = 1, H‐acceptor = 3, hydrophobic = 2; and (BTZ) H‐donor = 0, H‐acceptor = 0, hydrophobic = 3.

With 6LU7: (1) H‐donor = 3, H‐acceptor = 3, hydrophobic = 1; (2) H‐donor = 3, H‐acceptor = 3, hydrophobic = 1; (SB) H‐donor = 2, H‐acceptor = 2, hydrophobic = 0; and (BTZ) H‐donor = 0, H‐acceptor = 2, hydrophobic = 1.

From pharmacophore results, it was found that the SB ligand has high number of interactions with DNA and 1EMR. These results suggest that the SB ligands and their corresponding complexes may play an important rule in the drug design for anticancer purposes. The results for 6LU7 suggest that the complexes acted better than the ligands and the presence of the SB ligands are again important. Table 10 compares the binding energies of other comparable complexes to 6LU7 to demonstrate the merit of this work. Table 10 shows that our results are similar to, and in some cases superior than, those previously published.

TABLE 10.

Comparison of the binding energies of new and previously reported complexes obtained from molecular docking to 6LU7 (kcal mol−1)

4. CONCLUSION

Two new mixed‐ligand complexes containing an NN'O type unsymmetrical tridentate Schiff base ligand as the main ligand and pyridine (1) or 2,2′‐dimethyl‐4,4′‐bithiazole (BTZ) co‐ligands (2) were synthesized and characterized. These two complexes were used as anticancer agents against leukemia cancer cell line HL‐60. Molecular docking and pharmacophore studies were performed on BDNA and LIF to further investigate the anticancer activities of the complexes. The same computational studies were performed on SARS‐CoV‐2 virus receptor protein (PDB ID:6LU7).

From molecular docking studies, the obtained data reveal the following remarks:

Complex (1) showed better docking score with DNA (−10.10 ± 0.005). On the other hand, complex (2) showed better results with 1EMR (−8.43 ± 0.005 kcal mol−1) and with COVID‐19 (−8.28 ± 0.070 kcal mol−1). The order of the binding best energy for (1) is as follows: DNA > 6LU7 > 1EMR, and for (2) as 6LU7 > DNA > 1EMR. The order of the binding best energy for (SB) and (BTZ) is as follows: DNA > 1EMR > 6LU7.

NH2, H15, H16, H18, H19,O, N, BTZ rings, ph rings, Br, and pyridine rings were the ligational sites that interacted with protein pockets by predominantly H‐don. and H‐acc. interactions.

The C═N groups and the BTZ both contributed to stable docking positions.

Finally, this in silico approach confirmed the activity of Cu(II) complexes in controlling human cancer cells, which agreed with in vitro results.

The anticancer activity of these complexes was comparable with the standard drug 5‐FU.

The results of pharmacophore are consistent with the results of molecular docking and experimental results, and complex (2) showed the best performance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Liana Ghasemi: Data curation; software. Mahdi Behzad: Conceptualization; supervision. Ali khaleghian: Investigation. Alireza Abbasi: Investigation. Anita Abedi: Investigation.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information

Ghasemi L., Behzad M., Khaleghian A., Abbasi A., Abedi A., Appl Organomet Chem 2022, 36(5), e6639. 10.1002/aoc.6639

CCDC number 2089608 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for complex (2). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif (supporting information).

REFERENCES

- 1. Dralle Mjos K., Orvig C., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4540. 10.1021/cr400460s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zehra S., Roisnel T., Arjmand F., ACS Omega 2019, 4, 7691. 10.1021/acsomega.9b00131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palopoli C., Ferreyra J., Conte‐Daban A., Richezzi M., Foi A., Doctorovich F., Anxolabéhère‐Mallart E., Hureau C., Signorella S. R., ACS Omega 2019, 4, 48. 10.1021/acsomega.8b03018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salihović M., Pazalja M., Špirtović Halilović S., Veljović E., Mahmutović‐Dizdarević I., Roca S., Novaković I., Trifunović S., J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1241, 130670. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu M., Yang H., Li D., Yao Q., Wang H., Zhang Z., Dou J., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 522, 120384. 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lima L. M. A., Murakami H., Gaebler D. J., Silva W. E., Belian M. F., Lira E. C., Crans D. C., Inorganics 2021, 9, 42. 10.3390/inorganics9060042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rouf A., Tanyeli C., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 911. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.10.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kamal A., Syed M. A., Mohammed S. M., Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2015, 25, 335. 10.1517/13543776.2014.999764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borcea A. M., Ionuț I., Crișan O., Oniga O., Molecules 2021, 26, 624. 10.3390/molecules26030624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petrou A., Fesatidou M., Geronikaki A., Molecules 2021, 26, 3166. 10.3390/molecules26113166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Breslow R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 3719. 10.1021/ja01547a064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keating G. M., Drugs 2017, 77, 85. 10.1007/s40265-016-0677-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Froudarakis M., Hatzimichael E., Kyriazopoulou L., Lagos K., Pappas P., Tzakos A. G., Karavasilis V., Daliani D., Papandreou C., Briasoulis E., Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013, 87, 90. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borisenko V. E., Koll A., Kolmakov E. E., Rjasnyi A. G., J. Mol. Struct. 2006, 783, 101. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2005.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tan S. M., Wan Y. M., Psychiatry Res. 2016, 243, 365. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alimirzaei S., Behzad M., Abolmaali S., Abbasi Z., J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1200, 127148. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.127148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Albobaledi Z., Esfahani M. H., Behzad M., Abbasi A., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 499, 119185. 10.1016/j.ica.2019.119185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Esfahani M. H., Iranmanesh H., Beves J. E., Kaur M., Jasinski J. P., Behzad M., J. Coord. Chem. 2019, 72, 2326. 10.1080/00958972.2019.1643846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh G., Pawan, Mohit, Diksha, Suman, Priyanka, Sushma, Saini A., Kaur A., J. Mol. Struct, In Press, 1250. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Štekláč M., Zajaček D., Bučinský L., J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1245, 130968. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D., J. Virol. 2020, 92, 418, 418423. 10.1002/jmv.25681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qu Y.‐M., Kang E.‐M., Cong H.‐Y., Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 34, 101619. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheng V. C., Lau S. K., Woo P. C., Yuen K. Y., Clinic. Microb. Rev. 2007, 20, 660. 10.1128/CMR.00023-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zaki A. M., Van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T. M., Osterhaus A. D., Fouchier R. A., New England J. Medic. 2012, 367, 1814. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Irfan A., Imran M., Khalid N., Hussain R., Basra M. A. R., Khaliq T., Shahzad M., HussienAsma M., AbdulQayyum T. M., Al‐Sehemi A. G., Assiri M. A., J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101358. 10.1016/j.jscs.2021.101358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Irfan A., Imran M., Khalid M., Sami Ullah M., Khalid N., Assiri M. A., Thomas R., Muthu S., Basra M. A. R., Hussein M., Al‐Sehemi A. G., Shahzad M., J.Saudi. Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101277. 10.1016/j.jscs.2021.101277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Absalan A., Doroud D., Salehi‐Vaziri M., Kaghazian H., Ahmadi N., Zali F., Pouriavali's M. H., Mousavi‐Nasab S. D., Gastro. Hepa. Bed Bench 2020, 13, 355. 10.22037/ghfbb.v13i4.2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Keiretsu S., Bhujbal S. P., Cho S. J., Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17716. 10.1038/s41598-020-74468-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abbasi Z., Behzad M., Ghaffari A., Amiri Rudbari H., Bruno G., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2014, 414, 414, 78. 10.1016/j.ica.2014.01.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rajesh K., Somasundaram M., Saiganesh R., Balasubramanian K. K., J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 5867. 10.1021/jo070477u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khavasi H. R., Abedi A., Amani V., Potash B., Safari N., Polyhedron 2008, 27, 1848. 10.1080/00958970902948138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abbasi Z., Salehi M., Kubicki M., Khaleghian A., J.Coord.Chem. 2017, 70, 2074. 10.1080/00958972.2017.1323082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Malekshah R. E., Salehi M., Kubicki M., J. Coord. Chem. 2018, 71, 952. 10.1080/00958972.2018.1447668 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Behzad M., Seifikar Ghomi L., Damercheli M., Mehravi B., Shafiee Ardestani M., Samari Jahromi H., Abbasi Z., J. Coord. Chem. 2016, 69, 2469. 10.1080/00958972.2016.1198786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sadia M., Khan J., Naz R., Zahoor M., Shah S., Ullah R., Naz S., Bari A., Mahmood H. M., Ali S., Ansari S., Sohaib M., J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101333. 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.101331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roozbahani P., Salehi M., Malekshah R. E., Kubicki M., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2019, 496, 119022. 10.1016/j.ica.2019.119022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karami K., Rahimi M., Zakariazadeh M., Buyukgungor O., Momtazi‐Borojeni A. A., Esmaeili S. A., J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1177, 430. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.09.063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ghorai P., Saha R., Bhuiya S., Das S., Brandão P., Ghosh D., Bhaumik T., Bandyopadhyay P., Chattopadhyay D., Saha A., Polyhedron 2018, 141, 153. 10.1016/j.poly.2017.11.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Basha M. T., Alghanmi R. M., Shehata M. R., Abdel‐Rahman L. H., J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1183, 298. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abumelha H. M., Alkhatib F., Alzahrani S., Abualnaja M., Alsaigh S., Alfaifi M. Y., Althagafi I., El‐Metwaly N., J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 328, 115483. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Addison A. W., Rao N. T., Reedijk J., van Rijn J., Verschoor G. C., J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 7, 1349. 10.1039/DT9840001349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hasanzadeh Esfahani M., Iranmanesh H., Beves J. E., Kaur M., Jasinski J. P., Behzad M., J. Coord. Chem. 2019, 72, 2326. 10.1080/00958972.2019.1643846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rajarajeswari C., Ganeshpandian M., Palaniandavar M., Riyasdeen A., Akbarsha M. A., J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 140, 255. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ganeshpandian M., Ramakrishnan S., Palaniandavar M., Suresh E., Riyasdeen A., Akbarsha M. A., J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 140, 202. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lashanizadegan M., Asna Ashari H., Sarkheil M., Anafcheh M., Jahangiry S., Polyhedron 2021, 200, 115148. 10.1016/j.poly.2021.115148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Palaniammal A., Vedanayaki S., Mater. Today: Proc. 47, 1988. 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.04.142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kargar H., Adabi Ardakani A., Nawaz Tahir M., Ashfaq M., Munawar K. S., J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1229, 129842. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sakthivel R. V., Sankudevan P., Vennila P., Venkatesh G., Kaya S., Serdaroglu G., J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1233, 130097. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Costa R. G. A., da Anunciação T. A., Araujo M. S., Souza C. A., Dias R. B., Sales C. B. S., Rocha C. A. G., Soares M. B. P., Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 122, 109713. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sheryn W., Ninomiya M., Koketsu M., Aishah Hasbullah S., Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 3856. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2019.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Almarhoon Z. M., Al‐Onazi W. A., Alothman A. A., Al‐Mohaimeed A. M., Al‐Farraj E. S., J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 8152721. 10.1155/2019/8152721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dhahagani K., Mathan Kumar S., Chakkaravarthi G., Anitha K., Rajesh J., Ramu A., Rajagopal G., Acta A Mol. Bio. Mol. Spec. 2014, 117, 87. 10.1016/j.saa.2013.07.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Malekshah R. E., Salehi M., Kubicki M., Khaleghian A., J. Coord. Chem. 2018, 8972, 1. 10.1080/00958972.2018.1447668 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shamsi M., Yadav S., Arjmand F., J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2014, 5, 1. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ramezani N., Moghadam M. E., Behzad M., J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 26, 283. 10.1007/s00775-021-01851-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Baskaran S., Krishnan M. M., Arumugham M. N., Kumar R., J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1224, 129236. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang X.‐L., Zheng K., Wang L.‐Y., Li Y.‐T., Wu Z.‐Y., Yan C.‐W., Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 3, 730. 10.1002/aoc.3497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nicola N. A., Babon J. J., Cytokine Growth F R. 2015, 26, 533. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sun Q., Gao G., Xiong J., Wu Q., Liu H., Med. Hypotheses 2012, 79, 864. 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gearing D. P., Gough N. M., King J. A., Hilton D. J., Nicola N. A., Simpson R. J., Nice E. C., Kelso A., Metcalf D., J. EMBO 1987, 6, 3995. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02742.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Plun‐Favreau H., Perret D., Diveu C., Froger J., Chevalier S., Lelie'vre E., Gascan H., Chabbert M., J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27169. 10.1074/jbc.M303168200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang Y., Willson T., Metcalf D., Cary D., Hilton D. J., Clark R., Nicola N. A., J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 34370. 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Munshi A. M., Bayazeed A. A., Abualnaja M., Morad M., Alzahrani S., Alkhatib F., Shah R., Zaky R., El‐Metwaly N. M., Inorg. Chem. Communicat. 2021, 127, 108542. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.118100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Irfan A., Imran M., Khalid M., Ullah M. S., Khalid N., Assiri M. A., Thomas R., Muthu S., Basra M. A. R., Hussein M., J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101277. 10.1016/j.jscs.2021.101277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Nature 2020, 582, 289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Abdel‐Rahman L. H., Basha M. T., Al‐Farhan B. S., Shehata M. R., Mohamed S. K., Ramli Y., J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1247, 131348. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Adam M. S. S., Shaaban S., Khalifa M. E., Alhasani M., El‐Metwaly N. A., J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 335, 116554. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ali A., Sepay N., Afzal M., Sepay N., Alarifi A., Shahid M., Ahmad M., Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 110, 104772. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mohan B., Choudhary M., J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1246, 131246. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information