Abstract

Aims and method

This is a longitudinal cohort study describing the demand, capacity and outcomes of adult specialist eating disorder in-patient services covering a population of 3.5 million in a South-East England provider collaborative before and since the COVID-19 pandemic, between July 2018 and March 2021.

Results

There were 351 referrals for admission; 97% were female, 95% had a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa and 19% had a body mass index (BMI) <13. Referrals have increased by 21% since the start of pandemic, coinciding with reduced capacity. Waiting times have increased from 33 to 46 days. There were significant differences in outcomes between providers. A novel, integrated enhanced cognitive behaviour theapy treatment model showed a 25% reduction in length of stay and improved BMI on discharge (50% v. 16% BMI >19), compared with traditional eclectic in-patient treatment.

Clinical implications

Integrated enhanced cognitive behaviour theapy reduced length of stay and improved outcomes, and can offer more effective use of healthcare resources.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, in-patient treatment, access and waiting times, COVID-19, eating disorders

National background

In the 2019 Health Survey for England, 16% of adults aged ≥16 years (19% of women and 13% of men) screened positive for a possible eating disorder. This included 4% (5% of women and 3% of men) who reported that their feelings about food had interfered with their ability to work, meet personal responsibilities or enjoy a social life.1 This is almost a threefold increase since 2007.2 These findings may be surprising, but are consistent with international epidemiological data.3

In parallel, hospital admissions in England of people with eating disorders have increased from 4849 in 2007–2008 to 19 116 in 2018–2019.4 This shows an almost fourfold increase in demand, and there has been no investment in specialist eating disorder in-patient services during this time. Approximately 70% of people needing hospital admission are adults with anorexia nervosa.

On 6 November 2020, after the inquest into five avoidable deaths, the coroner for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, concluded that National Health Service (NHS) treatment for patients with anorexia nervosa is ‘not a safe system’ and risks ‘future deaths’.5 These statements mirror the 2017 Parliamentary Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) report.6 Three years ago, the PHSO made several helpful recommendations, including reviewing medical education, improving the workforce, ensuring the parity of funding of services across the age range and strengthening coordination of care. There has been limited progress since.7

Child and adolescent eating disorder services have received substantial investment since 2015,7 and progress toward meeting the referral to treatment waiting time standard has been monitored (https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/cyped-waiting-times/). These standards require child and adolescent eating disorder services to begin out-patient treatment within 1 week for urgent cases and 4 weeks for non-urgent cases. However, neither the standards nor monitoring are in place for adults, and the much-awaited funding into community eating disorder services has not yet reached the front line. Adult in-patient eating disorder services are part of specialist services and have been commissioned by NHS England. Over the past few years, NHS England has initiated a shift of commissioning to regional NHS collaborations, with the intention of transformation of care pathways focusing on the health of local populations, with the aim of improving outcomes and cost-savings.

Aims and objectives

In this paper, we describe demand and capacity for hospital treatment of patients with severe eating disorders in the Healthy Outcomes for People with Eating Disorders (HOPE) provider collaborative in South-East England since July 2018, and examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we compare the outcomes between different in-patient services, using the traditional eclectic treatment model with a new integrated enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (I-CBT-E) treatment across the care pathway.

Method

This is a longitudinal cohort study, involving all patients with eating disorders referred for admission from a total population of 3.5 million in South-East England. The study has been approved by the Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust Audit Department. Patient consent was not needed for the study.

The HOPE provider collaborative

The HOPE network was one of the first pilot sites of adult eating disorders selected by NHS England. It was established in shadow commissioning form in July 2018. The main goal of the network was to bring together in-patient and community services from several organisations providing in-patient and out-patient services for adults with eating disorders. Initially, the network included a total population of 5.2 million.

The footprint was reduced in September 2019, and the following partners have remained in the provider collaborative: Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Swindon, Wiltshire), Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Gloucestershire Health and Care NHS Foundation Trust and the Priory Group (in-patient provision in Bristol).

The total population of the geographical footprint is 3.5 million. Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust provides 14 beds in Oxford, and 6 beds in Marlborough. In addition, Oxford has six day patients and Marlborough has four. Berkshire and Gloucestershire have day services for 8 and 12 patients, respectively. The Bristol Priory is an independent partner in the provider collaborative providing specialist eating disorder beds; however, as it has a national contract with NHS England, their beds are not aligned with the HOPE provider collaborative.

This provider collaborative has developed a more collaborative and joined-up approach to admissions and discharge planning, with the aim of improving access closer to home and joint working between in-patient and out-patient teams. A weekly joint clinical activity panel consisting of senior clinicians from each organisation and a single point of access for all referrals has been established, to ensure that decisions about admissions are made by highly experienced clinicians. Referrals and outcomes have been systematically monitored since July 2018, for the whole geographical area.

There was also an agreement to monitor outcomes, and compare the NHS England standard eclectic model of care8 with a new, integrated stepped-care model using I-CBT-E in Oxford, building on the pioneering work of Dalle Grave et al.9 I-CBT-E offers a single evidence-based psychological model delivered by a multidisciplinary team, starting before admission and continuing across the treatment pathway (40 sessions in total). A detailed I-CBT-E formulation ensures continuity, consistency and a personalised treatment plan.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected capacity as a result of infection control measures across the care pathway. In-patient and out-patient services needed to reduce the number of people in poorly ventilated and crowded buildings. Day services had to be closed because of environmental and staffing challenges. Furthermore, remote working may have caused delays in recognition of deterioration of non-cooperating patients (both in primary and secondary care).

Demographic and clinical data

This paper analyses data from the partners who have been part of the provider collaborative since the beginning (Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Berkshire) for the period from July 2018 to 1 April 2021. The data collected concerns referrals, including demographic and clinical information, such as diagnoses and severity of physical risk related to malnutrition, and outcome of referrals, including length of admission and travelling distance. Body mass index (BMI) was recorded on referral, admission and discharge for those admitted. No additional outcome data was recorded for patients not admitted.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of the referred patients. Categorial variables were compared by χ2-test, and continuous variables by independent t-test and ANOVA, using SPSS for Windows version 22.

Results

Between July 2018 and 1 April 2021 there were 351 referrals for admission; 97% were female and mean age was 29.6 ± 11 years. According to DSM-5 severity ratings, 56.3% had extreme anorexia nervosa, 20.8% had severe anorexia nervosa, 17.9% had mild-to moderate anorexia nervosa, 1.8% had severe or extreme bulimia nervosa and 3.2% had other specified feeding or eating disorder. Approximately 65% of referrals were urgent or emergencies since the establishment of the provider collaborative. Urgency of referral was determined by the risk to the patient's health and safety, including level of malnutrition and risk to self; 19% of referrals had a BMI <13, which is an indicator of potentially life-threatening malnutrition, and a further 37% had extreme malnutrition. This pattern of referrals remained unchanged after the COVID-19 pandemic, but the absolute numbers increased by 21%.

There were no significant differences in mean age (29.20 ± 10.5 years v. 30.1 ± 11.9 years), gender (97% v. 99% female), diagnosis (95% v. 96% anorexia nervosa) or need for compulsory admissions (84.6% v. 83.4% informal), before or since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the outcome of referrals

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 63.6% of patients were admitted, which has increased to 65% since the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). The number of patients waiting has increased by 20%. However, this is likely to increase further with time, as the in-patient capacity for admission is insufficient, not just within the footprint, but also nationally. The reason for no admission was usually because of the patient refusal and/or ongoing out-patient treatment. Approximately half of these patients were admitted following a second referral.

Table 1.

Outcome of referrals before and since COVID-19 (number of patients and percentages)

| Before COVID-19 | Since COVID-19 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not admitted | Not admitted | 65 (38%) | 55 (35%) | 120 (36%) |

| In-patient unit in the HOPE provider collaborative area | Cotswold House Oxford | 50 (29%) | 50 (32%) | 100 (30%) |

| Cotswold House Marlborough | 15 (9%) | 22 (14%) | 37 (11%) | |

| Bristol Priory | 9 (5%) | 12 (8%) | 21 (6%) | |

| Out of area | Priory OOA | 15 (9%) | 14 (9%) | 29 (9%) |

| NHS OOA | 14 (8%) | 3 (2%) | 17 (5%) | |

| Cygnet | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 6 (2%) |

HOPE: Healthy Outcomes for People with Eating Disorders; OOA: Out of area placement; NHS, National Health Service Providers.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 43% of referrals could be admitted within the network, which has increased to 54% since the COVID-19 pandemic. The Priory Group provided 5% of admissions within the geographical area and a further 9% out of area.

Waiting times and travelling distance

The distance from home to hospital increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (from 41.4 ± 60 miles to 56 ± 78 miles). Eight patients were admitted to Priory Glasgow because of a lack of bed availability in England. Waiting times increased from 33 ± 44 days to 46 ± 43days (t-test = 0.03)

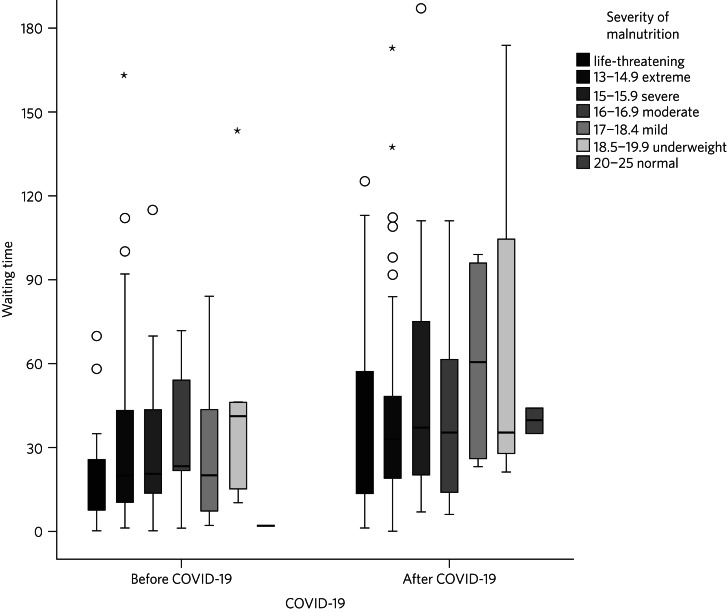

Even pre-COVID-19, the HOPE network already had a large demand/supply mismatch, with insufficient specialist beds within the network and lengthy waiting times even for patients with extreme or life-threatening malnutrition. This causes a vicious cycle of delayed and high-risk referrals requiring urgent admissions. Figure 1 demonstrates the variation in waiting times before and since the COVID-19 pandemic. It shows huge variations, even for the most high-risk patients, reflecting the reduced capacity in the system. One of the additional challenges is the lack of striated beds, which makes it difficult to meet the needs of patients who present with a high level of behavioural disturbance resulting from comorbidities such as autism spectrum disorders or personality disorders.

Fig. 1.

Waiting times for admission depending on severity of malnutrition.

The reduced specialist in-patient and day treatment capacity has had a significant impact on community teams in the footprint. Because of the lack of prompt access to specialist eating disorder units, approximately 19% of patients have required acute admission to general hospitals for emergency medical treatment. This represents a 20% increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, when acute hospital capacity is also reduced.

Differences between in-patient providers

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were significant differences between individual in-patient services in terms of length of stay (Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2021.73).

As part of the establishment of the provider collaborative, Cotswold House Oxford has been pioneering the implementation of an integrated stepped-care treatment, based on an intensive CBT-E model developed between Professor Fairburn in Oxford and Dr Dalle Grave in Italy.10 The model advocates integration of NICE-approved psychological treatment across the care pathway, with clear goal-oriented, time-limited admissions, followed by day and out-patient treatment. Given the differences between the Italian healthcare system and the NHS, we adapted the model by including a crisis admission pathway for those patients who refused full weight restoration but agreed to informal treatment. The details of the treatment will be discussed in a separate paper.

Here, we summarise the comparison between the outcomes of patients who were admitted to the Oxford unit and other specialist units that use the current standard eclectic treatment approach promoted by NHS England. Previous internal service evaluation of the Oxford pilot programme before the COVID-19 pandemic showed improved outcomes, reduction of restrictive practices (such as needing to use nasogastric feeding under restraints), improved patient outcomes and reduced length of stay. Despite the challenges, this has been maintained through the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2): 50.5% patients reached a BMI >19 compared with 16% in all other providers (χ2 = 0.000).

Table 2.

Comparison of the traditional eclectic in-patient treatment with the Oxford pilot programme (integrated CBT-E)

| In-patient treatment model | n | Mean | s.d. | Significance (two-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral BMI | Integrated CBT-E | 90 | 14.7 | 2.05 | 0.377 |

| Eclectic model | 92 | 14.5 | 1.96 | ||

| Discharge BMI | Integrated CBT-E | 88 | 18.2 | 2.27 | 0.0001 |

| Eclectic model | 84 | 17.0 | 1.89 | ||

| Length of admission (days) | Integrated CBT-E | 88 | 85.1 | 54.1 | 0.01 |

| Eclectic model | 92 | 107.2 | 68.8 | ||

| Home mileage to in-patient unit | Integrated CBT-E | 76 | 20.62 | 16.5 | 0.000 |

| Eclectic model | 79 | 67.1 | 80.5 | ||

| Age (years) | Integrated CBT-E | 90 | 32.2 | 13.2 | 0.005 |

| Eclectic model | 94 | 27.55 | 8.80 | ||

| Waiting time for admission (days) | Integrated CBT-E | 89 | 33.48 | 39.7 | 0.95 |

| Eclectic model | 92 | 33.1 | 42.3 |

CBT-E, enhanced cognitive behaviour theapy; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper providing a systematic analysis of referral patterns, access, waiting times and outcomes for adults with eating disorders requiring specialist in-patient treatment in England. The main strength of the study is the systematic data collection for 2.5 years, across a large geographical area with a population of 3.5 million. As the joint data collection had been established in July 2018, we have also been able to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on this patient population and corresponding services. Although regional, our data derive from a large geographical area, representing 6% of the population of England, so we believe that our findings are representative of most adult eating disorder services elsewhere in the country.

Referrals have increased by 20% since the COVID-19 pandemic, and this has resulted in increasing number of patients needing admission to acute hospitals and further away from home. Waiting times for admission were long even before the COVID-19 pandemic, and <50% of patients could be admitted close to home. Of those admitted, approximately a third were placed out of area. Out-of-area placements are well-known to cause distress to patients and families, and have been shown to have longer length of stay and poorer outcomes.11 Most worryingly, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with life-threatening malnutrition had to wait several weeks for admission, and this timescale has increased further since the pandemic, placing patients, staff and provider organisations at risk.

Although current national-level data by NHS Benchmarking on bed occupancy in hospitals suggest that demand is not dangerously high, this is not an appropriate indicator of how pressured specialist eating disorder services are across the care pathway. Infection control requirements and workforce impact of COVID-19 mean that the majority of NHS services are running at reduced capacity. Many services are struggling with reduced staffing levels resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, in specialist eating disorder services, monitoring risks and ensuring patient flow between in-patient, day and out-patient services has become much more challenging in an already pressurised system.

The physical environment is important to ensure patient and staff safety. The Royal College of Psychiatrists has been campaigning for improving mental health estates and facilities.12 This has become even more pressing since the COVID-19 pandemic: improving services to meet increasing demand requires capital investment into NHS mental health services

Following the high-profile reports into avoidable deaths, there has been an acknowledgement that adult community eating disorder services need to be funded to reach parity across the age range,6,13 and this is reflected in the new NHS England commissioning guidance for adult eating disorder services. However, this is still aspirational, and many adult patients struggle to access care or face long waiting times. This may explain the high number of patients in our network referred to hospital with a BMI of <13, in a life-threatening emergency, which has increased by 20% during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a concern, as although the Royal College of Psychiatrists published the ‘Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa’ (MARSIPAN) guidelines to improve patient safety in emergencies,14,15 their implementation has been inconsistent in acute hospitals, as shown by the recently reported tragedies. This is partly because of the limited training of eating disorders for doctors and allied health professionals, an area of concern that was identified by the PHSO.16

Although it is possible that the much needed investment into adult community eating disorder services in the next few years will reduce the need for in-patient treatment in the future, this is going to take several years. In-patient provision needs to be increased to meet current demand, which has quadrupled since 2007–2008 in England.4 Furthermore, recent national epidemiological data1 indicate increasing prevalence across the lifespan, and this is consistent with increasing referrals to the community teams and the increasing rates of hospital admissions. NHS-led provider collaboratives will only succeed if funding meets the need in the population served.

However, it is important to consider the significant variations in length of stay and short-term outcomes between providers. Our findings are consistent with previous research. In 2013, a UK-wide cohort study of adult specialist eating disorder units reported an average length of stay of 182 days and an average discharge BMI of 17.3,17 with only 22% reaching a BMI of 19 by discharge. In our study, only 16% of patients admitted to a unit offering standard eclectic treatment reached a discharge BMI >19, as opposed to 50% in the I-CBT-E pilot programme (within a 25% shorter length of stay), Discharge BMI is an important predictor of medium- and long-term outcomes.18,19 Although this was not a randomised controlled trial, the treatment model is based on a previous randomised controlled trial, and published manuals.9,10,20,21

The findings of the Oxford pilot programme (I-CBT-E) utilising an evidence-based and integrated stepped-care approach suggests that, with service transformation, reduced length of stay, improved patient outcomes and reduced restrictive practices are achievable. This can ensure use of existing limited in-patient capacity more effectively, and suggests a significant opportunity for cost-savings. This is particularly important, as a large proportion of patients in the cohort had an illness duration of >10 years. Our findings replicate previous studies from Italy,22,23 and suggest that the model is generalisable to the NHS. However, adaptation would require the redesigning of care pathways, staffing levels and skill mix. CBT-E training is freely available online (https://www.cbte.co/for-professionals/training-in-cbt-e/) and has been tested in previous research.24

The main limitations of our study are that we only had BMI as a consistent indicator of outcome at discharge, and that the comparison between in-patient providers was not based on randomisation. However, randomisation would not have been practically possible, given the limited capacity and the dispersal of beds in a wide geographical area in England and Scotland. Further work with our partners will explore more details of the longer-term psychosocial and health economic outcomes.

A multicentre, randomised controlled trial would be desirable, but it is important to note that the current NHS England standard contract is based on expert opinion rather than trial evidence, or robust outcome monitoring.

Clinical implications

It has been frequently stated that anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality of any mental disorder affecting young people and adults.25,26 We should not accept this: people should not die of anorexia nervosa or any eating disorder, as they are treatable mental disorders.27 Severe complications, such as malnutrition, are safely reversible, even in the most extreme cases.

The I-CBT-E model is based on a cohesive, integrated stepped-care approach for people with severe eating disorders, and wider implementation in the NHS has the potential to both improve short-term and long-term outcomes, with the added benefit of cost-savings. A national audit of demand, capacity and treatment outcomes would help to establish the need for specialist eating disorder beds, as well as explore the differences between various treatment models. There is an urgent need for capital investment into NHS mental health facilities to ensure a safe environment for patients and staff in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all of our partners for submitting the data, Beris Cummings and Este Botha for data collection and Dr Andrew Ayton for proofreading.

About the authors

Agnes Ayton is a Consultant Psychiatrist with Cotswold House, Oxford, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. David Viljoen is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist with Cotswold House Oxford, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Sharon Ryan is a Quality Improvement Lead with HOPE and CAMHS PC, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Ali Ibrahim is a Consultant Psychiatrist with the Berkshire Eating Disorder Service, Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, UK. Duncan Ford is a Provider Collaboratives Lead with Thames Valley Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK; and Provider Collaboratives Lead at the HOPE Adult Eating Disorder Provider Collaborative, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Author contributions

A.A. and A.I. developed the initial idea. D.V., S.R. and D.F. helped with the design and data collection. A.A. wrote the first draft and all authors contributed to the final draft and the revised version.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2021.73.

click here to view supplementary material

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, A.A., upon reasonable request.

Declaration of interest

None.

References

- 1.NHS Digital. Health Survey for England, 2019: Data Tables. NHS Digital, 2020 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2019/health-survey-for-england-2019-data-tables).

- 2.McManus SM, Howard ., Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R. Adult Psychiatric Morbidity in England, 2007: Results of a Household Survey. The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2007. (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-in-england-2007-results-of-a-household-survey). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galmiche M, Dechelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr 2019; 109(5): 1402–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS Digital. Finished Admission Episodes (FAEs) with a Primary or Secondary Diagnosis of Eating Disorder. NHS Digital, 2018 (https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/find-data-and-publications/supplementary-information/2019-supplementary-information-files/obesity/finished-admission-episodes-faes-with-a-primary-or-secondary-diagnosis-of-eating-disorder).

- 5.Ayton A. Investment in training, evidence based treatment, and research are necessary to prevent future deaths in eating disorders. BMJ 2020; 371: m4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman. Ignoring the Alarms: How NHS Eating Disorder Services Are Failing Patients. Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman, 2017. (https://www.ombudsman.org.uk/publications/ignoring-alarms-how-nhs-eating-disorder-services-are-failing-patients).

- 7.NHS England. Children and Young People's Eating Disorders Programme. NHS England, 2015. (https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/cyp/eating-disorders/). [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS England. NHS Standard Contract for Specialised Eating Disorders (Adults). NHS England, 2013. (https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2014/12/c01-spec-eat-dis-1214.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalle Grave R. Multistep Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders: Theory, Practice, and Clinical Cases. Jason Aronson, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalle Grave R, Conti M, Calugi S. Effectiveness of intensive cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2020; 53(9): 1428–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS. Out of Area Placements in Mental Health Services. NHS Digital, 2021. (https://files.digital.nhs.uk/B1/222D10/oaps-rep-apr-2021.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royal College of Psychiatrists. Next Steps For Funding Mental Healthcare in England. RCPsych, 2020. (https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/policy/next-steps-for-funding-mental-healthcare---infrastructure-royal-college-of-psychiatrists-august-2020.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee. Ignoring the Alarms Follow-Up: Too Many Avoidable Deaths from Eating Disorders. HMSO, 2019. (https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubadm/855/85502.htm). [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Royal Colleges of Psychiatrists, Physicians and Pathologists. MARSIPAN: Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa, 2nd Edition. CR189. The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2014. (https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr189.pdf?sfvrsn=6c2e7ada_2).

- 15.Junior MARSIPAN Group. Junior MARSIPAN: Management of Really Sick Patients under 18 with Anorexia Nervosa. CR168. The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2012. (https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr168.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayton A, Ibrahim A. Does UK medical education provide doctors with sufficient skills and knowledge to manage patients with eating disorders safely? Postgrad Med J 2018; 94(1113): 374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goddard E, Hibbs R, Raenker S, Salerno L, Arcelus J, Boughton N, et al. A multi-centre cohort study of short term outcomes of hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa in the UK. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13: 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redgrave GW, Schreyer CC, Coughlin JW, Fischer LK, Pletch A, Guarda AS. Discharge body mass index, not illness chronicity, predicts 6-month weight outcome in patients hospitalized with anorexia nervosa. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 641861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redgrave GW, Coughlin JW, Schreyer CC, Martin LM, Leonpacher AK, Seide M, et al. Refeeding and weight restoration outcomes in anorexia nervosa: challenging current guidelines. Int J Eat Disord 2015; 48(7): 866–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Conti M, Doll H, Fairburn CG. Inpatient cognitive behaviour therapy for anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom 2013; 82(6): 390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O'Connor ME, Palmer RL, Dalle Grave R. Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with anorexia nervosa: a UK-Italy study. Behav Res Ther 2013; 51(1): R2–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calugi S, El Ghoch M, Dalle Grave R. Intensive enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a longitudinal outcome study. Behav Res Ther 2017; 89: 41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, El Ghoch M, Conti M, Fairburn CG. Inpatient cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: immediate and longer-term effects. Front Psychiatr 2014; 5: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairburn CG, Allen E, Bailey-Straebler S, O'Connor ME, Cooper Z. Scaling up psychological treatments: a countrywide test of the online training of therapists. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19(6): e214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulik CM, Flatt R, Abbaspour A, Carroll I. Reconceptualizing anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019; 73(9): 518–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoang U, Goldacre M, James A. Mortality following hospital discharge with a diagnosis of eating disorder: national record linkage study, England, 2001-2009. Int J Eat Disord 2014; 47(5): 507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholls D, Becker A. Food for thought: bringing eating disorders out of the shadows. Br J Psychiatry 2020; 216(2): 67–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2021.73.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, A.A., upon reasonable request.