Abstract

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is indicative of terminal malignancy with a uniformly fatal prognosis. Often, two distinct compartments of tumour microenvironment, the effusion and disseminated pleural tumours, co-exist in the pleural cavity, presenting a major challenge for therapeutic interventions and drug delivery. Clinical evidence suggests that MPE comprises abundant tumour-associated myeloid cells with the tumour-promoting phenotype, impairing antitumour immunity. Here we developed a liposomal nanoparticle loaded with cyclic dinucleotide (LNP-CDN) for targeted activation of stimulators of interferon genes signalling in macrophages and dendritic cells and showed that, on intrapleural administration, they induce drastic changes in the transcriptional landscape in MPE, mitigating the immune cold MPE in both effusion and pleural tumours. Moreover, combination immunotherapy with blockade of programmed death ligand 1 potently reduced MPE volume and inhibited tumour growth not only in the pleural cavity but also in the lung parenchyma, conferring significantly prolonged survival of MPE-bearing mice. Furthermore, the LNP-CDN-induced immunological effects were also observed with clinical MPE samples, suggesting the potential of intrapleural LNP-CDN for clinical MPE immunotherapy.

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) secondary to metastatic cancer represents an enormous challenge in clinical patient management1–3. The appearance of MPE is an ominous prognostic sign for patients with cancer; the average survival of patients with MPE is 4–9 months1–3. Moreover, accumulation of pleural effusion commonly causes dyspnoea that severely compromises quality of life. The current standard of care treatment for MPE includes catheter drainage or chemical/surgical pleurodesis but is largely palliative4,5.

MPE is a build-up of extra fluid in the space between the lungs and chest wall, comprising tumour cells and various types of immune cells. Accompanying MPE, disseminated and unresectable tumour foci (carcinomatosis) often develop on the pleural surface. Clinical immunopathological studies suggest that the tumour microenvironment (TME) of MPE is profoundly immunosuppressive with abundant tumour-promoting myeloid immune cells and high levels of immunosuppressive cytokines, which negatively affects antitumour immunity2,6–9. Moreover, variable levels of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression have been detected on tumour cells in clinical MPE10–12, and recent clinical trials with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 in patients with MPE have observed some meaningful antitumour activity10–14. Previous attempts to boost the anti-MPE immune response involved intrapleural administration of immunostimulants such as bacterial antigens, pro-inflammatory cytokines, oncolytic virus or adenoviral cytokine genes15–18. While variable degrees of efficacy have been reported, many of them were found either to overcome insufficiently the immunosuppressive TME or cause adverse effects2,19. Thus, developing a new intrapleural strategy that effectively converts the immune cold into proinflammatory MPE is imperative to improve MPE immunotherapy.

The stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway has recently been identified to play an important role in antitumour immunity20,21. As a potent STING agonist, the cyclic dinucleotide (CDN), 2’3’-cGAMP, functions in the cytosol to ligate STING and activate the STING pathway and type I interferon (IFN) production22. While recent preclinical studies involving intratumoral injection of CDN have demonstrated its ability to enhance antitumour immunity in solid tumours23–26, the potential of intrapleural CDN has not been explored. However, there are some concerns with the use of free CDN in MPE. Built from labile phosphodiester bonds, the CDN is susceptible to degradation by ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (ENPP1)27–29. Soluble ENPP1 exists in human and mouse serum and higher levels of ENPP1 have been reported in malignant effusion27,29,30. Moreover, recent studies have shown that activation of the STING pathway within tumour-resident antigen-presenting cells (APCs) is necessary for the induction of anticancer CD8+ T cell immunity21,31,32, whereas non-targeted, free CDN can induce T cell apoptosis33,34 or increase the resistance of tumour cells to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)35.

To overcome the immune cold MPE, we synthesized CDN-loaded, phosphatidylserine (PS)-coated liposomes (LNP-CDN) that demonstrate favourable pharmacokinetic profiles in MPE and selective targeting of intrapleural phagocytes. Loading of CDN complexed with calcium phosphate (CaP) enables pH-responsive release of CDN from the endosome to the cytosol, where it ligates STING to initiate STING signalling. To gain insights into the immunological effects of intrapleural LNP-CDN on individual immune cell populations, we conducted single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of MPE in mouse models. We then investigated if LNP-CDN-induced pro-inflammatory MPE and upregulation of PD-L1 would set the stage for response to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy against MPE in mouse models. Furthermore, MPE samples of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were obtained to demonstrate that the immunological effects induced by LNP-CDN in mice could be reproduced in humans.

Intrapleurally injected LNP-CDN targets phagocytes in MPE.

We synthesized a series of LNPs with variable surface compositions of different phospholipids with/without polyethylene glycol (PEG), to load CDN complexed with CaP (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among them, the PS-coated LNPs with/without DSPE-PEG2000 (10%; LNP-1 and LNP-2) exhibited excellent in vitro phagocyte targeting specificity and PS-mediated cell uptake (Supplementary Fig. 1). The PEGylated LNP-2 was stable over time with little CDN release at pH 7.4, but destabilized rapidly to release CDN at an acidic pH (Supplementary Fig. 1). In vivo pharmacokinetic data revealed that LNP-2 achieved better MPE retention and less extrathoracic distribution than the non-PEGylated LNP-1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, LNP-2-based LNP-CDN was chosen to use in this study.

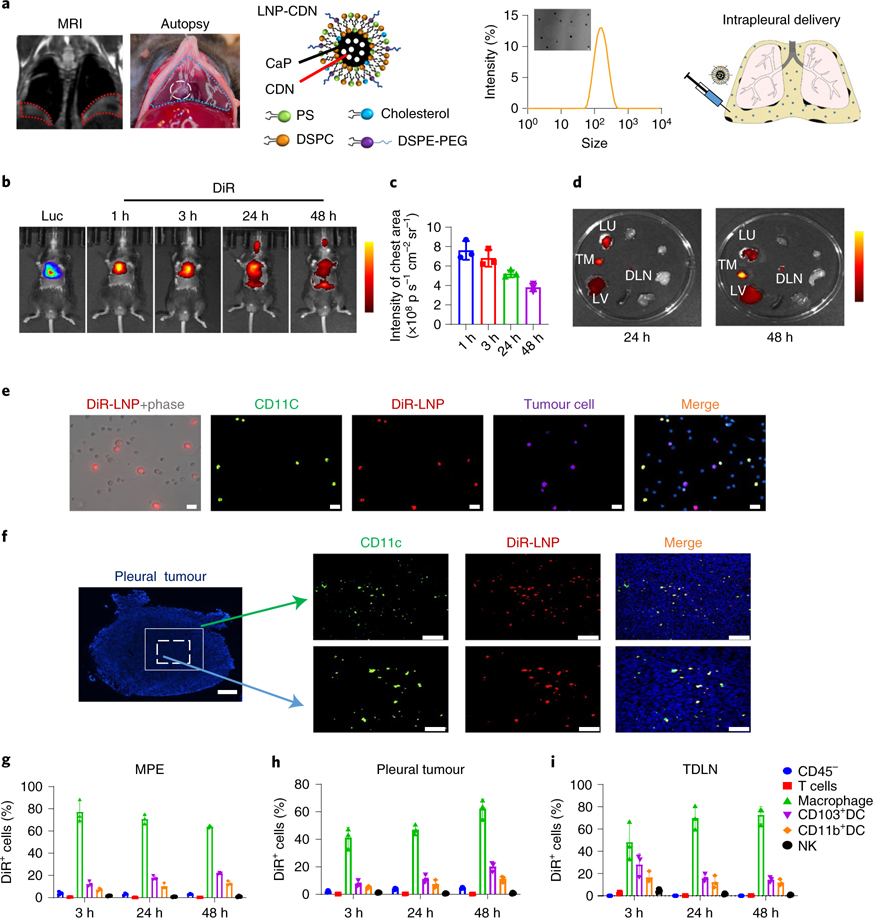

LNP-CDN has an average diameter of ~120 nm and a negative surface charge of −15 mV (Fig. 1a). A mouse MPE model of Lewis lung cancer (LLC) developed both the fluid in the pleural cavity and multifocal tumours on the pleural surface, clearly seen by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and at autopsy (Fig. 1a). An in vivo imaging system (IVIS) at different times post-intrapleural injection of 1,1’-dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,’3’-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (DiR)-labelled LNP clearly showed that the majority of signals remained in the chest region and were sustained for at least 48 h (Fig. 1b,c). Ex vivo IVIS detected DiR-LNP signals in pleural tumours, tumour-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs), lung and liver (Fig. 1d), which were quantitated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Supplementary Fig. 2). There was minimal DiR-LNP in the blood and other major organs. Immunocytochemistry of the cells collected from MPE after intrapleural DiR-LNP revealed predominant uptake of LNP-CDN by CD11c+ monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs; Fig. 1e). Immunohistochemistry of pleural tumour tissues depicted well-dispersed LNPs that also colocalized well with CD11c+ monocytes/macrophages and DCs (Fig. 1f). Consistently, our flow data showed that DiR-LNPs were captured primarily by macrophages, CD103+ DCs and CD11b+ DCs, while minimal uptake was observed in tumour cells, T cells or natural killer (NK) cells in MPE, pleural tumours and TDLNs (Fig. 1g–i). CD103+ DCs are considered as the most competent APCs to cross-prime CD8+ T cells36–38. Together, these data indicate that intrapleural LNP-CDN enables phagocyte-targeted delivery of CDN in both MPE and pleural tumours in the pleural cavity. Notably, LNP-CDN itself or carried by APCs can migrate from MPE to TDLNs, which probably potentiates APC-mediated cross-priming of cytotoxic T cells in TDLNs.

Fig. 1 |. Intrapleurally administered LNP targets phagocytes in MPe and pleural tumours.

a, Establishment of a mouse MPE model and intrapleural injection of LNP-CDN with a diameter of 120 nm, measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering. MRI and autopsy confirmed the development of intrapleural effusion and pleural tumours derived from LLC-Luc cells. b–c, In vivo IVIS imaging (b) and quantitative photon counts (c) over time post-intrapleural DiR-labelled LNPs. d, Representative ex vivo IVIS imaging (of three independent experiments) of major organs from MPE mice receiving intrapleural DiR-LNP. DLN, draining lymph node; LU, lung; LV, liver; TM, (pleural) tumour. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biologically independent mice per time point. Scale bar, yellow to dark red, signal intensity high to low. e, Live cells were collected from the MPE 24 h postintrapleural DiR-LNP for immunofluorescence microscopy. Double staining showed DiR-LNPs (red) colocalizing predominantly with CD11c+ phagocytes (green). LLC-Luc tumour cells (purple), 4′−6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue); scale bars, 20 μm. Representative images of three independent experiments. f, A representative pleural tumour was dissected from the pleural cavity 24 h after intrapleural DiR-LNP. Immunofluorescence staining showed that DiR-LNPs penetrated well intratumorally and colocalized with CD11c+ phagocytes. Whole pleural tumour, scale bar, 250 μm; top scale bars, 100 μm; bottom scale bars, 50 μm. Representative images of three independent animals. g–i, Flow cytometry analysis at different times after intrapleural DiR-LNP determined the percentage of DiR+ cells within their respective population in MPE (g) pleural tumours (h) and TDLNs (i) Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biologically independent mice.

Intrapleural LNP-CDN reprograms myeloid immune cells.

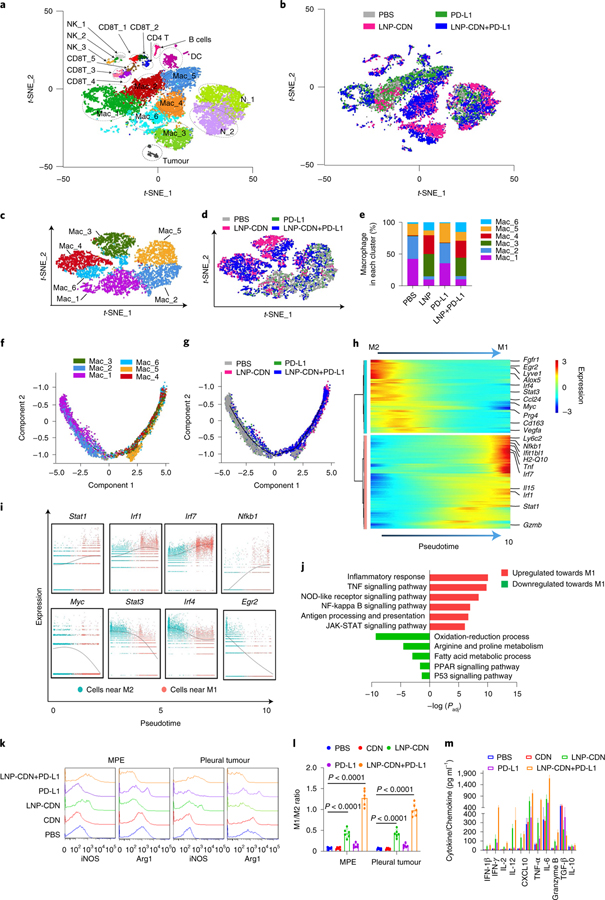

To elucidate the immune landscape in MPE and its response to intrapleural LNP-CDN, we applied scRNA-seq without bias to characterize cell type-specific transcriptional profiles after intrapleural PBS, LNP-CDN, anti-PD-L1 antibody (Ab) or LNP-CDN+ anti-PD-L1 Ab. About 4,000 single cells from the pooled MPE of three LLC MPE-bearing mice per condition were subjected to scRNA-seq. As depicted in t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) projection, unsupervised clustering singled out 20 distinct cell clusters, comprising tumour cells and various immune cells of monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, DCs, NKs, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T and B cells (Fig. 2a,b). Clearly, MPE contained a large number of myeloid cells including macrophages (Cd68 and Adgre1; ~55%) and neutrophils (Ly6g; ~30%). In-depth scRNA-seq clustering of the macrophage population yielded six subclusters (Fig. 2c). Mac_3, Mac_4 and Mac_6 were exclusively induced after LNP-CDN alone or in combination with anti-PD-L1 Ab (Fig. 2c–e), which showed significantly upregulated M1-associated genes (Supplementary Fig. 3). By contrast, Mac_1 and Mac_2 that exhibited high expression of M2-associated genes were primarily found in the PBS control or anti-PD-L1 alone group, while Mac_5 was a mixture of cells from each treatment (Fig. 2c–e and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 |. Intrapleural LNP-CDN reprograms immunosuppressive myeloid cells towards pro-inflammatory phenotype and remodels the immune landscape in MPe.

a, Unsupervised scRNA-seq of pooled whole MPE cells (n = 3 mice per treatment) obtained 48 h later revealed 20 colour-coded cell clusters. b, t-SNE plot of all cells colour-coded by treatment. c, t-SNE subclustering of six colour-coded subsets of intrapleural macrophages combined from all four treatments. d,e, t-SNE plot, colour-coded by treatment (d) and bar plot (e) showing subpopulations of macrophages distinctly separated between LNP-CDN or combination treatment and PBS or anti-PD-L1 alone, of which Mac_3, Mac_4 and Mac_6 were exclusive to LNP-CDN alone or in combination with anti-PD-L1. f, Macrophage subclusters (Mac_1 to Mac_6) superimposed on pseudotime trajectory. g, Macrophage superimposed on the pseudotime trajectory colour-coded by treatment. h, Heatmap of differentially expressed genes ordered based on their common kinetics through pseudotime during M2 to M1 repolarization. Cells (columns) are ordered along the M2 to M1 path. i, Representative gene expression of transcriptional factors involved in M2 to M1 repolarization plotted as a function of pseudotime. Each dot in the scatter plot represents the gene expression of a single cell. j, Selected significantly enriched terms in the GO and KEGG analyses based on the gradually upregulated (red) and downregulated (green) genes in M2 to M1 repolarization. The full list can be seen in Supplementary Table 1. k,l, Representative flow plots (k) showing intrapleural LNP-CDN-induced right shift of iNOS expression (M1-like marker) while a left shift of arginase1 (M2-like marker) on macrophages in both MPE and pleural tumours, and increased ratios of M1:M2 (l). Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. m, ELISA of various cytokines and chemokines in pleural fluid under the indicated treatment. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice.

To investigate the transcriptome dynamics during macrophage repolarization, we applied the Monocle2 method for trajectory analysis. Monocle determines and orders single cells along a trajectory of two alternative cellular fates, namely the M2 and M1 fates (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 4). Mac_1 and Mac_2 were located close to the M2 fate, while Mac_3 to Mac_6 were closer to the M1 fate (Fig. 2f). LNP-CDN alone or in combination clearly induced macrophage repolarization and gradual transition from the M2 to the M1 fate (Fig. 2g). Moreover, the trajectory heatmap revealed sequential gene expression changes (Fig. 2h). Clearly, gradually upregulated or downregulated expression of genes was shown during the switch from M2 to M1 (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, we examined the enriched functions associated with these transitional genes by extracting functional gene ontology (GO) terms and biological pathways (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways). We identified gene enrichment associated with antigen processing and presentation and the biological process related to inflammatory response during M2 to M1 repolarization (Fig. 2j).

To validate the scRNA-seq immunophenotyping, we conducted flow cytometry and found that LNP-CDN indeed skewed the M2 (F4/80 + arginase 1+) to M1-like macrophages (F4/80 + iNOS+) in both MPE and pleural tumours (Fig. 2k,l). On the contrary, intrapleural free CDN had no immunological effects, which probably resulted from rapid degradation of CDN by ENPP1, which was detected at a high concentration of 7,200 pg ml−1 in MPE (Supplementary Fig. 5). Intrapleural LNP-CDN plus anti-PD-L1 Ab was found to further enhance further the ratio of M1/M2 (Fig. 2k,l). An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) also detected increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as type I IFNs, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12 and the IL-15–IL-15R complex in MPE after intrapleural LNP-CDN (Fig. 2m). Together, these data clearly indicate that the TME in MPE is profoundly immunosuppressive with enrichment of M2/N2-like myeloid cells but intrapleural LNP-CDN effectively repolarizes these myeloid cells towards the pro-inflammatory phenotype.

LNP-CDN promotes cytotoxic effector CD8+ T cells and NK cells.

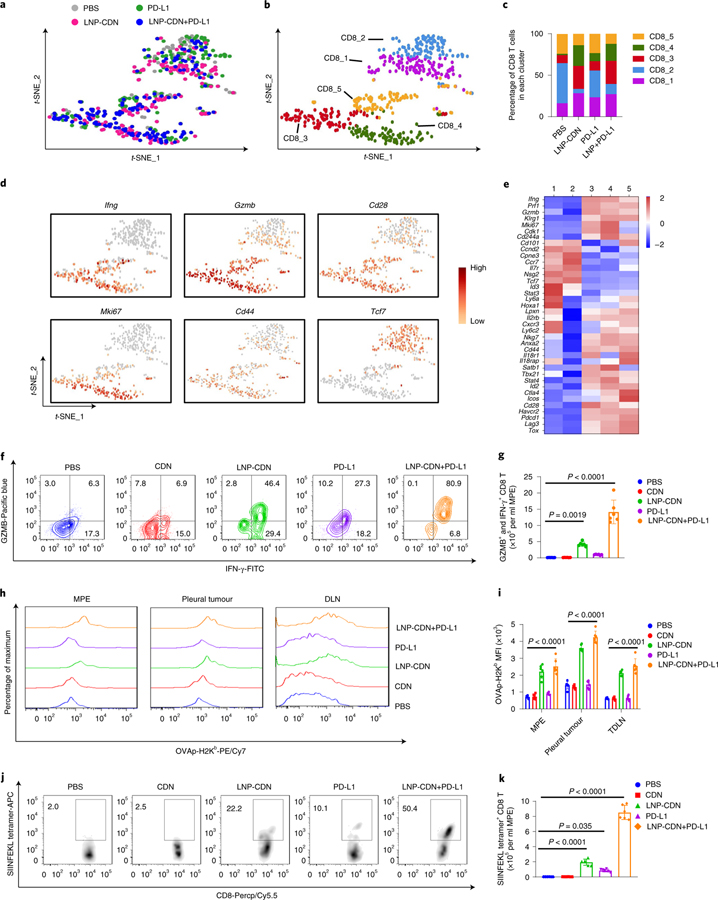

In addition to its effects on myeloid cells, intrapleural LNP-CDN led to marked expansion of MPE-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). scRNA-seq depicted five distinct subclusters of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3b). CD8_3 and CD8_4 were predominantly induced after intrapleural LNP-CDN and to a lesser degree by anti-PD-L1 Ab (Fig. 3b,c). While both the subclusters exhibited upregulated expression of effector molecules (Ifng, Prf1, Gzmb and Klrg1) and costimulatory receptors (Cd28 and Icos), consistent with an activating effector phenotype, CD8_4 was found to have higher expression of cell cycle transcripts (Cdk1, Mki67 and Pcna) (Fig. 3d,e). CD8T_1, also largely expanded by LNP-CDN, presented a naive-like phenotype (Tcf7+, Ccr7+, Pdcd1−) but also expressed high levels of stem cell antigen 1 (Sca-1 or Ly6a), the haematopoietic stem cell engraftment genes Hoxa1 and Lpxn and memory markers such as Il2rb and Cxcr3 (Fig. 3d,e), probably associated with the stem-like memory CD8+ T phenotype39–41. Conversely, most T cells under PBS treatment were located in CD8_2 and CD8_5 (Fig. 3b,c), of which CD8_2 showed high expression of Ccr7, Il7r and Tcf7 but low expression of Cd44, probably indicative of naive-like T cells, while CD8_5 expressed high levels of Tox, Pdcd1, Lag3 and Ctla4 (Fig. 3d,e and Supplementary Fig. 8), commonly linked to T cell exhaustion42,43. We also applied the Monocle2 to CD8+ T cells and yielded trifurcating trajectories (Supplementary Fig. 9). Concurring with the t-SNE characterization, CD8T_1 and CD8T_2 were enriched in the memory/naive branch, CD8T_3 and CD8T_4 were largely located in the effector branch, while CD8T_5 was found primarily in the exhausted branch (Supplementary Fig. 9). In response to LNP-CDN or LNP-CDN+ anti-PD-L1, CD8+ T cells were found to accumulate on the effector trajectory with some on the memory/naive trajectory (Supplementary Fig 9). Similarly, bulk RNA-seq analysis showed that the combination immunotherapy enriched genes in multiple signalling pathways relevant to T cell proliferation and activation, differentiation and migration and T cell-mediated immunity and cytotoxicity (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11).

Fig. 3 |. Intrapleural LNP-CDN promotes polyfunctional CD8+ effector T cells, expands stem-like memory CD8+ T cells and generates tumour-specific cytotoxic T cells in MPe.

a, t-SNE plots of intrapleural Cd8a+ T cells colour-coded by treatment. b, t-SNE projection showing Cd8a+ T cells colour-coded by subclusters. c, Bar plots showing the frequency of Cd8a+ T cells within each cluster as a function of treatment. d, Gene expression patterns projected onto t-SNE plots of Ifng, Gzmb, Cd28, Mki67, Cd44 and Tcf7 (scale, log2 fold change). e, Heatmap showing z-scores of differentially expressed individual genes in subcluster 1–5 shown in b. a–e Data are from one experiment with n = 3 MPE samples pooled per treatment. The full differential expression gene list between subclusters is provided in Supplementary Table 4. f, Flow plots showing polyfunctional CD8+ T cells with double-positive staining for IFN-γ and Gzmb. g, Number of cells with double-positive staining quantitated. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. h,i, Representative flow plots (h) and quantitative data (i) of the OVA peptide SIINFEKL–MHC class I molecule Kb complex on CD103+ (CD11c+, CD103+, CD11b−) DCs in MPE, pleural tumours and TDLNs. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. j,k, Representative flow plots (j) and quantitative data (k) of the SIINFEKL tetramer + CD8+ T cells in MPE under the indicated treatment. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s pos-hoc test.

Notably, LNP-CDN alone or combined with anti-PD-L1 Ab significantly increased the number of polyfunctional CD8+ T cells with both IFN-γ+ and granzyme B (Gzmb)+ in MPE and pleural tumours (Fig. 3f,g and Supplementary Fig. 7). Utilizing the LLC-ovalbumin (OVA) MPE-bearing mice, our data showed that there was a significant increase in the uptake of exogenous OVA-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) by CD103+ DCs (Supplementary Fig. 12) and presentation of the SIINFEKL–MHC class I complex on CD103+ DCs in MPE, pleural tumours and TDLNs (Fig. 3h,i) post-intrapleural LNP-CDN. LNP-CDN also led to more than a tenfold increase in SIINFEKL tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in MPE (Fig. 3j,k); a marked increase in SIINFEKL tetramer+ CD8+ T cells was also seen in pleural tumours, TDLNs and spleen (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 13). In different cohorts of the MPE mice, sequential analysis of MPE from the same individuals showed that a single intrapleural dose of LNP-CDN or LNP-CDN+ anti-PD-L1 was able to promote the pro-inflammatory TME and activate CD8+ T cells and their cytotoxic functions in MPE (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). Taken together, these data demonstrate that intrapleural LNP-CDN promotes APC sensing of tumour antigen (TA) and cross-priming of tumour-specific CD8+ T cells and expands the populations of both polyfunctional effector CD8+ T cells and stem-like memory CD8+ T cells in MPE.

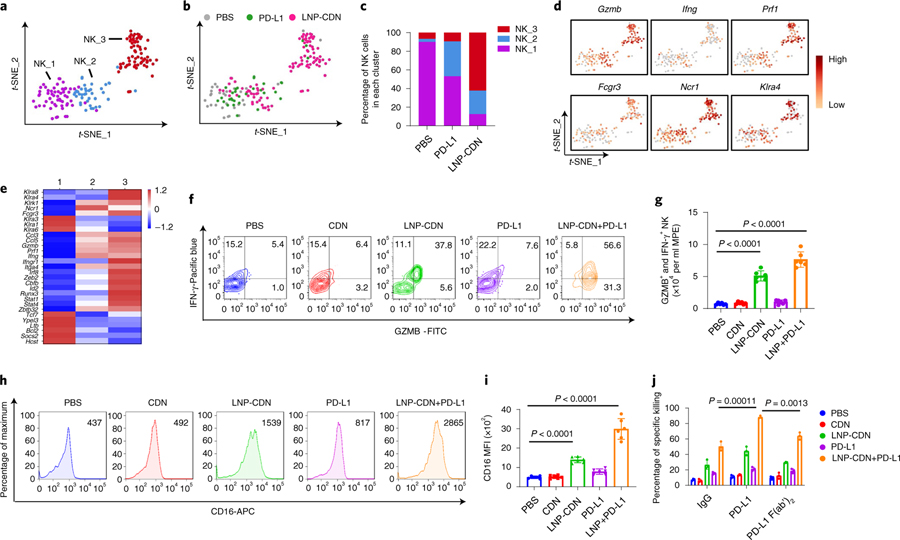

Recent clinical studies indicate that NK cells in MPE present a low cytotoxic phenotype44,45. We investigated if intrapleural LNP-CDN could reinvigorate the antitumour function of NK cells in MPE. scRNA-seq profiling revealed distinct clustering patterns between PBS and LNP-CDN treatment (Fig. 4a,b). NK_2 and NK_3 were markedly expanded after intrapleural LNP-CDN (Fig. 4c), which exhibited increased expression of genes encoding activating NK receptors (Ncr1, Klrk1, Fcgr3, Klra8 and Klra4), effector molecules (Ifng, Gamb and Prf1) and activating transcription factors (Irf8, Zeb2 and Cbfb) (Fig. 4d,e). In contrast, NK cells under PBS control were confined to NK_1 (Fig. 4b,c), expressing high levels of genes associated with inhibitory NK receptors (Klra1, Klra3 and Klra6) (Fig. 4d,e). In line with the t-SNE clusters, the trajectory analysis revealed that LNP-CDN or LNP-CDN+ anti-PD-L1 skewed NK cells from the immature to mature state (Supplementary Fig. 16).

Fig. 4 |. LNP-CDN promotes the effector function and cytotoxic activity of NK cells.

a, t-SNE projection showing three colour-coded subclusters of Klrb1c+ NK cells in MPE. b, The t-SNE plot in a, colour-coded by treatment. c, Bar plots showing the frequency of NK cells within each cluster as a function of treatment. d, Gene expression patterns projected onto the t-SNE plots of Gzmb, Ifng, Prf1, Fcrg3, Ncr1 and Klra4 (log2 fold change). e, Heatmap showing the z-scores of differentially expressed individual genes in each subcluster from a. a–e Data are from one experiment with n = 3 MPE samples pooled per treatment. f, Flow plots showing polyfunctional NK cells with double-positive staining for IFN-γ and Gzmb. g, Number of cells with double-positive staining quantitated. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. h,i, Representative flow plots (h) and quantitative data (i) of CD16 expression in NK cells under the indicated treatment. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. j, Ex vivo cell killing of NK cells isolated from the MPE of LLC mice under the indicated treatment in the presence of the IgG2b isotype, anti-mouse PD-L1 or PD-L1 F(ab’)2. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Flow cytometry revealed that intrapleural LNP-CDN with/without anti-PD-L1 Ab promoted polyfunctional production of IFN-γ and Gzmb (Fig. 4f,g), and expression of the activating Fcγ receptor (FcγR), CD16, in NK cells (Fig. 4h,i and Supplementary Fig. 17). Moreover, an in vitro tumour cell killing assay showed that NK cells isolated from the MPE pretreated with LNP-CDN killed significantly more LLC cells compared to the PBS control (Fig. 4j). Adding anti-PD-L1 Ab led to even more deaths of LLC cells (Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 18). Besides its function to disrupt the PD-1–PD-L1 axis, the IgG2b isotype of anti-PD-L1, 10 F.9G2, is known to interact with mouse FcγRs to induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) against PD-L1+ tumour cells46. Indeed, anti-PD-L1 F(ab’)2 was found to have lower cytotoxicity in the above cytolysis study. Together, these data demonstrate that intrapleural LNP-CDN revamps the cytotoxic activity of NK cells, which is further enhanced by combining with anti-PD-L1 Ab through its blocking of PD-1/PD-L1 interaction and the ADCC effect.

Intrapleural LNP-CDN enhances anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy.

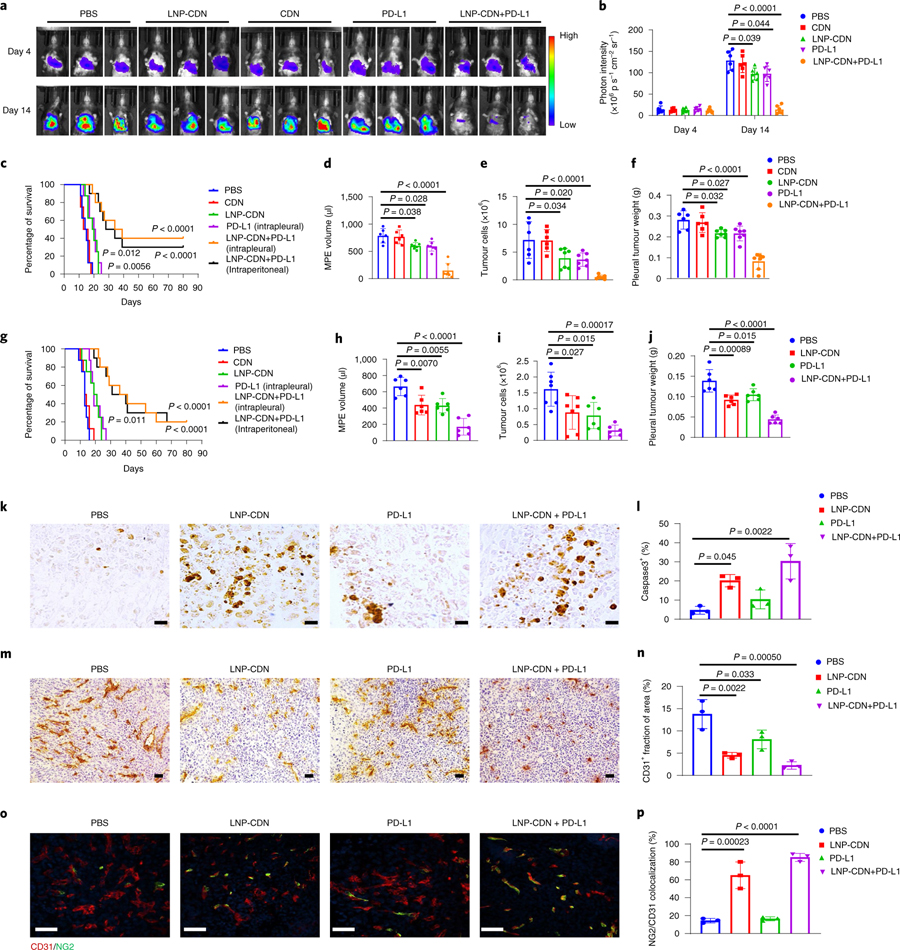

It is known that PD-L1 is inducible by IFNs to serve as a counter-regulatory mechanism47–49. LNP-CDN was found to increase the expression of PD-L1 and MHC class I on tumour cells at the transcript and protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 19). Thus, combining anti-PD-L1 Ab to counteract overexpressed PD-L1 may be a rational strategy to augment anticancer immunity. Anti-PD-L1 Ab is commonly administered systemically. To explore an alternative administration, we compared intrapleural versus intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of anti-PD-L1 Ab in this study. Pharmacokinetic data showed that the intrapleural approach achieved a tenfold and threefold higher pleural concentration of anti-PD-L1 Ab at 3h and 24h, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18). Intrapleural anti-PD-L1 also led to significantly higher Ab concentrations in pleural tumours and TDLNs but much lower blood concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 18). Thus, we included intrapleural anti-PD-L1 Ab in our treatment study but with less than one-third of the i.p. dose (100 μg). Intrapleural LNP-CDN or anti-PD-L1 (30 μg) monotherapy delayed tumour growth and MPE progression; the combination treatment resulted in a further decrease in MPE volume and pleural tumour burden and significantly prolonged survival in wild-type but not STING−/− mice bearing LLC stably transfected with firefly luciferase (LLC-Luc) MPE (Fig. 5a–f and Supplementary Fig. 18). There was no significant difference in survival benefit between intrapleural and systemic anti-PD-L1 Ab (Fig. 5c). Similar antitumour immune responses and therapeutic efficacy of the combination immunotherapy were also observed in the CMT-167-Luc MPE model (Fig. 5g–j and Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). Immunohistochemistry of pleural tumours revealed significantly more apoptotic cells induced by the combination treatment (Fig. 5k,l). Intriguingly, in contrast to the enlarged and distorted angiogenic vessels observed in pleural tumours with PBS control, LNP-CDN alone or in combination resulted in ‘normalized’ blood vessels (Fig. 5m–p). Through bulk RNA-seq, the combination treatment was found to upregulate the expression of vascular normalization/stabilization genes and anti-angiogenic genes, while downregulating pro-angiogenic genes (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11).

Fig. 5 |. Intrapleural LNP-CDN in combination with anti-PD-L1 Ab suppresses pleural tumour growth, reduces MPe volume and prolongs survival of MPe mice.

a, Intrapleural tumour burden monitored with BLI of mice with the indicated treatment on days 4 and 14. b, Quantitative photon counts within the chest area. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 6 biologically independent mice. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. c, Kaplan–Meier survival assay of LLC MPE mice with the indicated treatment. n = 10 in the LNP-CDN+ PD-L1 group, n = 8 in the other groups. P = 0.012 in LNP-CDN versus PBS and P = 0.0056 in PD-L1 versus PBS, respectively; two-sided log-rank test. d–f, MPE volume (d), non-haematological cell (CD45−) counts in MPE by flow cytometry (e) and pleural tumour weight (f) were measured on day 14 in the LLC-Luc MPE mice (n = 6 in the PBS and CDN groups, n = 7 in the other group). Data are shown as the mean ± s.d.; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. g–j, Kaplan–Meier survival assay of CMT167-Luc MPE mice with the indicated treatment (g), MPE volume (h), non-haematological cell (CD45−) counts in MPE (i) and pleural tumour weight (j) on day 14 in the CMT167-Luc MPE mice. n = 10 in the LNP-CDN+ PD-L1 group, n = 8 in the other groups for the survival assay; P = 0.011 in LNP-CDN versus PBS; two-sided log-rank test. n = 6 per group for the MPE evaluation in h–j. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. Two-sided log-rank test for the survival assay, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for the others. k–p, Immunohistochemical staining (k) and quantification (l) of active caspase3+ apoptotic cells, immunohistochemical staining (m) and quantification (n) of CD31+ cells and immunofluorescence staining (o) and quantification (p) of CD31+ and NG2+ cells in pleural tumours of n = 3 biologically independent mice with LLC-Luc MPE under the indicated treatment. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. Scale bars, 20 μm (k) or 50 μm (m and o). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Because MPE is often associated with NSCLC, we created a mouse model with concomitant lung cancer and MPE and treated mice with intrapleural combination immunotherapy. Assessment of the treatment effects by IVIS and ex vivo examinations of lung tumour foci showed that combination immunotherapy significantly inhibited lung tumour growth (Supplementary Fig. 22), indicating that antitumour immune responses are not confined to the pleural cavity but extended to the lung parenchyma. Moreover, long-term surviving MPE mice resisted secondary LLC tumour but not B6 melanoma challenge, suggesting that combination treatment triggers tumour-specific antitumour memory (Supplementary Fig. 23).

To determine if the observed antitumour immune responses were derived from the integrative efforts of both innate and adaptive immune cells, we conducted depletion studies and analysed the effects of loss of individual immune cells. Depletion of macrophages/DCs in MPE by LNP-clodronate (LNP-Clod) completely abrogated the treatment-induced cytotoxicity observed in both in vivo apoptosis assay and Kaplan–Meier survival study (Supplementary Fig. 18). Sequential depletion studies revealed that depleting CD8+ T cells or NK cells starting 1 day before treatment or depleting CD8+ T cells 7 days after treatment largely abolished the antitumour effects of combination immunotherapy (Supplementary Fig. 18). However, loss of NK cells at the latter time had little impact on animal survival. These data suggested the critical role of NK cells during the early phase of antitumour immunity. Together, these data indicate that the observed anticancer immunity is indeed macrophage/DC-initiated/mediated and collaborative efforts of the innate and adaptive effector lymphocytes are required to execute the antitumour activity.

Intrapleural LNP-CDN and anti-PD-L1 Ab were well tolerated by the MPE mice. Safety studies showed no abnormality in blood liver enzyme levels or morphological changes in major organs from the short-term treated or the long-term surviving mice (Supplementary Fig. 24), supporting the notion that intrapleural LNP-CDN alone or in combination with anti-PD-L1 Ab is safe.

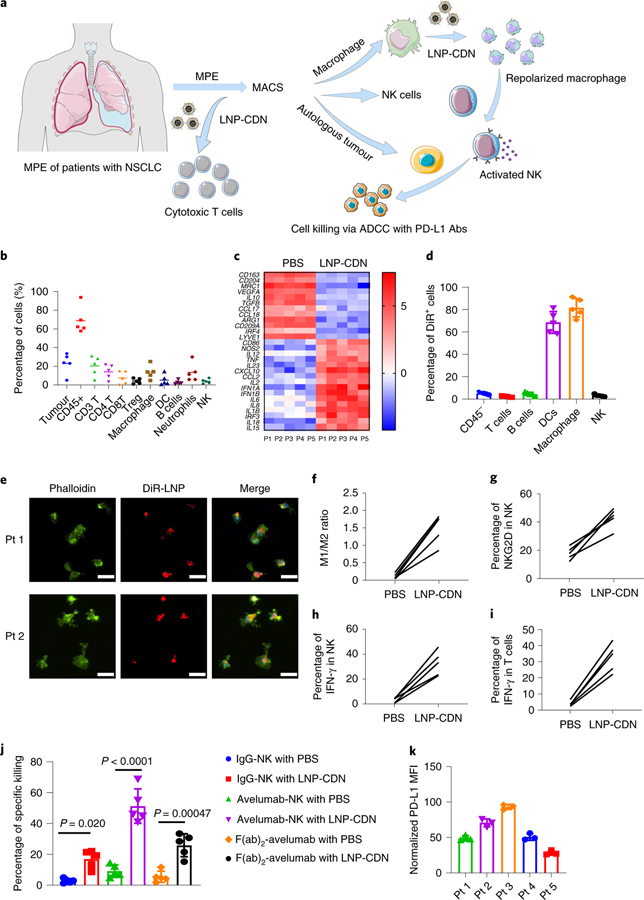

Immunological effects of LNP-CDN are confirmed in human MPE.

To assess the translational potential of intrapleural LNP-CDN, we obtained clinical MPE samples (n = 5 patients) during thoracentesis of patients with NSCLC with confirmed MPE cytology (Fig. 6a). Flow cytometry of MPE identified tumour cells (~30%) and diverse immune cells (~60%) with a wide range of variation between individual patients (Fig. 6b). Among the immune cells, CD3+ T cells, monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils were more prevalent. Despite the high percentage of T lymphocytes, the fraction of CD8+ T cells was much lower than that of CD4+ T cells and a considerable number of CD4+ regulatory T cells were present (Fig. 6b). Monocytes/macrophages isolated from each patient’s MPE exhibited homogeneously upregulated expression of M2-associated genes (Fig. 6c). ELISA detected low levels of IFNs and other pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in MPE (Supplementary Fig. 25). These data are in good agreement with previous clinical observations, suggesting the immune cold MPE50–53.

Fig. 6 |. LNP-CDN reprograms tumour-associated macrophages, activates cytotoxic effector NK cells and CD8+ T cells and enhances the cytotoxic activity of NK cells in the MPe of patients with NSCLC.

a, Schemes of treating patients’ MPE with LNP-CDN. b, Cellular compositions of MPE freshly obtained from patients with NSCLC (n = 5) determined by flow cytometry. Each spot represents an individual MPE sample. Tumor and CD45+ cells were the percentage of live cells; other immune cells were the percentage of CD45+ cells. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. c, Pairwise comparison of gene expression profiles showing LNP-CDN induced M1-associated genes while suppressing M2-associated genes in macrophages. The heatmap data are shown as the mean log2 fold change normalized to normal human PBMCs. d, Specific uptake of DiR-LNP by macrophages and DCs in patients’ MPE (n = 5) by flow cytometry. The percentage of DiR+ cells in their own population are presented. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. e, Immunofluorescence imaging of the uptake of DiR-LNP (red) by macrophages (green) isolated from representative patients’ MPE. Scale bars, 20 μm. Representative images of three independent experiments. f, Flow plots showing increased ratios of M1 (CD80)/M2 (CD206) after LNP-CDN treatment of individual MPE samples (n = 5). g,h, LNP-CDN activated NK cells in patients’ MPE (n = 5). Sorted NK cells from patient MPEs were cocultured with supernatant from LNP-CDN-treated macrophages for 18 h; the cell surface expression of NKG2D (g) and intracellular expression of IFN-γ (h) were determined by flow cytometry. i, LNP-CDN activated CD8+ T cells in patients’ MPE (n = 5). j, NK cell cytotoxicity and PD-L1 Ab-mediated ADCC enhanced by LNP-CDN. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 5 patient samples. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. k, Heterogeneous expression of PD-L1 on tumour cells observed among the samples of five individual patients. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biologically independent experiments.

To study the utility of LNP-CDN in human MPE, we first evaluated its targeting specificity by incubating DiR-LNP with fresh MPE or isolated macrophages from MPE (Supplementary Fig. 26 and 27). Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence microscopy revealed the predominant uptake of DiR-LNP by monocytes/macrophages and DCs (Fig. 6d,e). We next investigated the ex vivo effects of LNP-CDN on various immune cells in MPE. Incubation of LNP-CDN with isolated macrophages induced increased expression of M1-associated genes in all five patient samples (Fig. 6c,f). We also isolated NK cells from individual samples and treated NK cells with the supernatant from the above LNP-CDN-treated macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 27). Flow cytometry detected a marked increase in expression of the activating receptor, NKG2D and production of intracellular IFN-γ (Fig. 6g,h). Moreover, incubation of LNP-CDN with fresh MPE led to a drastic increase in IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells in all five samples (Fig. 6i). Furthermore, the LNP-CDN-activated NK cells demonstrated enhanced cytolysis of autologous tumour cells (Fig. 6j). As variable levels of PD-L1 were expressed on pleural tumour cells in all samples (Fig. 6k), combining avelumab, the clinically approved IgG1 anti-PD-L1 monoclonal Ab, further increased NK cell cytotoxicity (Fig. 6j). Together, these data support the potential use of intrapleural LNP-CDN in human MPE.

Conclusions

Consistent with previous reports, our data showed that MPE in mice and humans was profoundly immunosuppressive with abundant tumour-promoting myeloid cells. Despite being a potent STING agonist, 2’3’-cGAMP CDN has a short biological half-life in MPE because MPE contains a high level of ENPP1 that degrades CDN. We developed the CDN-loaded liposomal nanoparticle LNP-CDN, which protected CDN from enzymatic degradation in MPE and exhibited its specific targeting of macrophages and DCs to activate STING signalling. Through scRNA-seq, intrapleural LNP-CDN was found to induce drastic changes in the transcriptional landscape in MPE by reprogramming myeloid cells, activating DCs for cross-presentation of TA, promoting polyfunctional NK cells and CD8+ T cells and expanding stem-like memory CD8+ T cells. We further showed that LNP-CDN-induced remodelling of the MPE TME set a stage for response to anti-PD-L1 ICB.

In the context of clinical practice, LNP-CDN can be administered serially via indwelling pleural catheters. Clinically, the presence of MPE often precludes surgical intervention and many patients with MPE are not fit for chemotherapy due to their extremely poor condition. Thus, successful management of MPE may renew opportunities for combining with other treatment options to maximize therapeutic efficacy.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of LNP-CDN.

The liposome LNP-CDN with CaP core complexed with CDN (LNP) was prepared in two steps using the water-in-oil reverse microemulsion method54,55. 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine,18:0 PC (DSPC), cholesterol, brain l-α-phosphatidylserine (PS), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DSPA) and 18:1 Liss Rhod PE, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (Rhod-b)) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. 2’3’-cGAMP, cyclic [G(2’,5’)pA(3’,5’)p] (CDN)) was purchased from InvivoGen. The CaP core with single-layer anionic lipid coating (PS:DSPC:cholesterol = 5:4:1) was prepared and 4 lipid mixtures (molar ratios) for the outlayer coating of LNP were prepared: (1) LNP-1, brain-PS:DSPC: cholesterol = 5:4:1; (2) LNP-2, brain-P S:DSPC:cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000 = 5:4:1:1; (3) LNP-3, DSPA:DSPC: cholesterol = 5:4:1; 4. DOTAP:PS:DSPC: cholesterol =1:5:4:1. LNP-CaP nanoparticles with bilayer lipid coating were formed by adding 1 ml of PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and rehydrating under water bath sonication for 5 min and sonic probe at 20 W for another 2 min at 70 °C. The resulting nanoparticles were further filtered with a 0.45 μM membrane to remove the free lipid aggregates and stored at 4 °C. To load the CDN, half of the desired CDN content was mixed with each of the CaCl2 and Na2HPO4 solutions. To fluorescently label NPs, 18:1 Liss Rhod PE (Rhod-b) was added to the second lipid mixture with a molar ratio of 1%; alternatively, DiR was used for labelling the NPs by adding DiR directly to the second lipid mixture at a molar ratio of 5%. Loading of CDN without the use of CaP in liposomes (lipid mixture, 20 mM, brain-PS:DSPC:cholesterol:DSPE-PEG2000 = 5:4:1:1) was also prepared using the above thin-film hydration method.

The size, size distribution and zeta potential of LNP-CDN in aqueous solution were measured with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS90 and analysed by Zetasizer (7.12). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements were performed on an FEI Tecnai Bio Twin transmission electron microscope.

The release of CDN from LNPs was assessed by the dialysis of LNP-CDN solution against release medium at different pHs (pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0) at various time points by Agilent 1100 HPLC. The LNPs were incubated in PBS (pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0; 0.01 M) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (v/v) at 37 °C for 12 h to study particle stability and pH-responsive ability.

Cell lines.

The mouse NSCLC LLC (ATCC), CMT-167 (clone CMT64; Sigma-Aldrich), OVA-transfected LLC (LLC-OVA) and B16 melanoma (provided by Y. Lu; Wake Forest) cells, LLC-Luc cells or cells stably transfected with red fluorescent protein (LLC-RFP) and CMT cells stably transfected with firefly luciferase (CMT-Luc) were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U ml−1 of penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 of streptomycin and maintained in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% carbon dioxide at 37 °C. Cell lines were confirmed Mycoplasma negative every 2 weeks.

Animal model.

All animal experiments complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and research and were performed with approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine. Mice were group-housed in autoclaved caging (Allentown Caging) on corn cob bedding (1/4” Bed-o-Cob; Andersons Lab Bedding) and provided with compressed paper nesting material (Lab Supply). Animals were provided with rodent chow ad libitum (Purina ProLab diet). Animals were maintained in an AAALAC-accredited facility in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition). They were maintained on a 12–12 light–dark cycle with a temperature of 20–23 °C and humidity of 48–52%.

For the NSCLC MPE model, 6–8-week-old C57BL/6 mice (female:male at 1:1; Charles River Laboratories) were injected intrapleurally with LLC-Luc (2 × 105) or CMT167-Luc (2 × 105) lung cancer cells. STING knockout mice (B6(Cg)-Sting1tm1.2Camb/J, 6–8 weeks old, female:male at 1:1; The Jackson Laboratory) were also used for the MPE model. Development of MPE was monitored by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) or MRI. For the subcutaneous tumour model, 1 × 106 of LLC cells (left flank) and 5 × 105 B16 melanoma cells (right flank) were injected. Tumour volumes were measured longitudinally by a caliper up to 3 weeks. The maximum tumour burden in mice allowed by the IACUC of Wake Forest University School of Medicine is less than 20 mm in any one direction (WF IACUC SOP#19). We strictly followed the guidelines in this study.

In vivo bio-distribution of DiR-LNP.

Mice with an established LLC-Luc MPE model were intrapleurally injected with LNPs labelled with DiR and longitudinally monitored at 1, 3, 24 and 48 h post-injection using the IVIS Lumina system. Randomly selected animals were killed at 24 and 48 h (n = 3 per time point) and major organs were dissected and imaged ex vivo by IVIS. MPE cells were collected and costained with anti-mouse CD11c-FITC (1:100 dilution; BioLegend, clone N418) and anti-luciferase (1:800 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, catalogue no. L0159) followed by cy3-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and observed using a fluorescence microscope. DiR signals were recorded and merged with the CD11c image and the luciferase-stained image of the same field. Isolated pleural tumours were also preserved and sectioned for immunofluorescence microscopy as described above. DiR+ cells in MPE, pleural tumours and DLNs were also assessed by flow cytometry. To quantify the tissue concentrations of LNPs, LLC-Luc mice with MPE were killed at 1, 2, 8, 24, 48 and 72 h after intrapleural injection of Rhod-b-labelled LNPs (n = 3 per time point). Major organs and blood were collected for HPLC analyses.

scRNA-seq of MPE cells.

LLC MPE mice (n = 3 per treatment) were treated with intrapleural PBS, LNP-CDN (1 μg), anti-PD-L1 Ab (clone 10F.9G2; 30 μg; Bio X Cell) or LNP-CDN plus anti-PD-L1 Ab. Forty-eight hours later, pleural fluid cells were collected and pooled from n = 3 MPE mice under each treatment. Biological replicates were then processed at the single-cell suspension stage with an equivalent number of cells from each replicate. Four thousand cells from each of the mixed samples for each condition were loaded onto the 10x Genomics Chromium System. Library preparation was performed using the 10x Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kit V3 according to the manufacturer’s instructions by the Cancer Genomics Shared Resource (CGSR) of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center and passed quality control. Libraries were sequenced using a NovaSeq 6000 system (one library per lane) at the CGSR.

scRNA-seq analysis.

The Cell Ranger Single Cell Software Suite v.3.0.2 (10x Genomics) was used to perform sample de-multiplexing, alignment, filtering and universal molecular identifier counting. The data for each respective subpopulation were aggregated for direct comparison of single-cell transcriptomes. We used the Seurat toolkit to perform principal component analysis and t-SNE analysis. For the t-SNE projection and clustering analysis, we used the first 50 principal components. Clusters consisting of cells with low/null expression of Gapdh and Eno1 (non-cells), or coexpression of cell type-exclusive markers (doublets) were removed from further analysis. Clusters containing the following cell types were identified using cell type markers: CD4 T cells (Cd3e and Cd4), CD8 T cells (subclusters CD8T_1 to CD8T_5, Cd3e and Cd8a), DCs (H2-Aa and Itgax), B cells (Cd79d and Ly6d), NK cells (Klrb1c), macrophages (subclusters Mac_1 to Mac_6, Adgre1 and Itgam), N_2 neutrophils (Ly6g, Arg2 and Ccl17), N_1 neutrophils (Ly6g and Cxcl10) and tumour cells (Rpl29 and Krt18). Cell type assignments for each cluster were verified by comparing with the ImmGen datasets. Cluster frequencies by library were normalized to the number of cells per library. Differential gene expression of macrophages, NK cells, CD8 T cells and tumour cells within their subclusters was also analysed by Loupe Browser v.5.0.0 and visualized by their values of log2 fold change (P < 0.05) under each treatment.

Trajectory analysis.

Monocle 2 v.2.20.0 was used for the trajectory analysis of cell populations including macrophages, NK cells and T cells to reveal the dynamic process of cell and gene expression changes. Genes used for cell ordering were determined in an unsupervised way by their differential expression across cells. Dimensionality reduction and trajectory construction was performed on the selected genes with default methods and parameters, through the DDRTree method and orderCells function. Cells in less differentiation type, for example, M2 phenotype, informed us of the start point and initial state of the pseudotime. The visualization function plot_cell_trajectory was used to plot the minimum spanning tree on cells. The functions plot_genes_in_pseudotime and plot_genes_branched_heatmap were used to visualize gene expression changes along the cell trajectory.

Flow cytometry.

LLC or CMT MPE mice were randomly grouped and treated on day 11 with intrapleural PBS, free CDN (1 μg), LNP-CDN (1 μg), anti-PD-L1 Ab (30 μg) or LNP-CDN plus anti-PD-L1 Ab. Mice were killed on day 13 and pleural fluid was gently aspirated using a 1 ml syringe through the diaphragm and its volume was measured with a 1 ml pipette. Solid tumours on the pleural surface and mediastinal lymph nodes were also collected and processed for analysis.

Flow cytometry was performed on a BD Canto II flow cytometer; data were collected with the FACSDiva software v.6.1.3 and analysed using the FlowJo software v.10.1 (FlowJo LLC). A list of antibodies used is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. All antibodies for mouse flow cytometry were used at a 1:100 dilution. Doublets and debris of dead cells were excluded before various gating strategies were applied (Supplementary Figs. 28 and 29). Gates and quadrants were set based on isotype control staining and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values were calculated by subtracting the MFI of the isotype control antibodies.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on the cryosections (10 μm) of different tissues, including heart, lung, liver, spleen, intestine and skin from healthy or MPE mice. For immunofluorescence staining of T cells, cryosections (10 μm) of LLC-Luc lung MPE-bearing tumour tissues obtained from the above treatment group were immunostained with anti-mouse CD8α-PerCP/Cyanine5.5 (1:200 dilution; BioLegend) or anti-mouse FoxP3-Alexa Fluor 647 antibody (1:250 dilution; BioLegend). For immunofluorescence staining of vasculature, anti-mouse CD31 (1:200 dilution; BD Biosciences) and anti-mouse NG2 (1:100 dilution; Abcam), followed by goat anti-rat Cy3 (1:400 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:100 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch). For PD-L1, apoptosis or vasculature staining, anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody (1:2,000 dilution; B7-H1; Bio X Cell), anti-mouse cleaved caspase 3 antibody (1:400 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-mouse CD31 antibody (1:200 dilution; BD Biosciences), followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:500 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch) or goat anti-rat secondary antibody (1:500 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch) were applied, respectively. Sections were then developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine kits (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with haematoxylin.

In vivo experimental treatment in MPE mouse models.

LLC-Luc MPE or CMT-Luc MPE mice, after confirming tumour formation by IVIS, were randomly grouped (n = 8–10 per group) and treated on day 4 and repeated on days 6 and 8 as follows: (1) PBS (intrapleural injection); (2) LNP-CDN (1 μg × 3, intrapleural injection); (3) free CDN (1 μg × 3, intrapleural injection); (4) anti-PD-L1 Ab (10F.9G2; 30 μg × 3, intrapleural injection); (5) LNP-CDN (intrapleural injection) + anti-PD-L1 (intrapleural injection); (6) LNP-CDN (intrapleural injection) + anti-PD-L1 (intraperitoneal injection, 100 μg × 3). For depletion of macrophages and DCs in pleural fluid, mice were injected i.p. with 200 μg of LNP-Clod 1 day before treatment and followed by one or three doses of intrapleural LNP-Clod. To study the role of the STING pathway, STING knockout mice were also treated with LNP-CDN + PD-L1. To deplete CD8 T cells or NK cells throughout the treatment, 400 μg of anti-mouse NK1.1 (clone PK136; Bio X Cell) or anti-mouse CD8a antibody (clone 2.43; Bio X Cell) were injected i.p. 1 day before the treatment and 100 μg of anti-mouse NK1.1 or anti-mouse CD8a were coinjected intrapleurally with LNP-CDN at the time of treatment, followed by twice per week i.p. injection of 100 μg of anti-mouse NK1.1 or anti-mouse CD8a throughout treatment. For different groups of mice, CD8 T cells or NK cells were depleted starting 7 days after the initial treatment by i.p. injection of the Abs twice per week throughout treatment. The development of pleural tumours and MPE were monitored longitudinally by BLI. MPE volume and solid tumour weight were measured on day 14. Tumour cell numbers in the fluid and memory CD8 T cells were evaluated by flow cytometry. Mice survival (n = 8–10 per group) was followed up to 80 days.

Human MPE sample acquisition.

In this study, malignant pleural effusion samples (100 ml per patient) from five patients diagnosed with NSCLC were collected during thoracentesis and distributed by tumour tissue and pathology shared resource (TTPSR) of the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center Comprehensive Cancer Center. Acquisition of de-identified MPE samples from TTPSR for research use was in accordance with the institutional review board of Wake Forest University (protocol no. IRB00040151). All patients provided written informed consent.

MPE preparation from human samples.

MPE from patients was centrifuged at 800g for 10 min at 4 °C; supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C. The cell pellets containing red blood cells were treated with 2 ml of ACK lysing buffer at 4 °C for 10 min followed by adding 10 ml of PBS to stop the lysis. Cell suspensions were further centrifuged at 500g for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended with PBS buffer to single-cell solutions for the following analyses.

Flow cytometry of cellular compositions of human MPE.

As described above, flow cytometry was performed on a BD Canto II flow cytometer and analysed using the FlowJo software. A list of the anti-human antibodies used is summarized in Supplementary Table 2. All antibodies for human flow cytometry were used at a 1:100 dilution.

For the T cell activation study, fresh MPE was incubated with LNP-CDN (100 nM) overnight. MPE cells were treated with a phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-ionomycin cocktail according to the manufacturer’s specification (BioLegend) before intracellular IFN-γ staining.

Isolation and culture of macrophages and NK cells from patients’ MPE samples.

Monocytes/macrophages from MPE were isolated by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) using magnetic beads conjugated with human CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The sorted macrophage purity was higher than 85% as confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting using anti-human CD14 and anti-human CD68 monoclonal Abs (Supplementary Fig. 25).

NK cells from MPE were purified by MACS with the human NK Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and non-NK cells were depleted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NK cell purity was assessed by flow cytometry using anti-human CD3 and CD56 monoclonal Abs.

Autologous tumour cells from patients’ MPE were separated by MACS with the human tumour Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec), which depleted tumour-associated cells such as lymphocyte subpopulations, fibroblasts and endothelial cells.

Ex vivo treatment of macrophages from the patient sample with LNP-CDN.

Sorted macrophages (106 in 60 mm culture dishes) were treated with PBS or LNP-CDN (100 nM) for 18 h and the culture medium was collected for ELISA assay of cytokines and further coculture with NK cells. Macrophages after LNP-CDN treatment were stained with M1 macrophage marker (anti-human iNOS, anti-human human leukocyte antigen–DR isotype and anti-CD80 monoclonal Abs) and M2 macrophage marker (anti-human CD206 and anti-human CD163 monoclonal Abs) for flow analysis.

Real-time PCR of M1- and M2-like gene profiles.

The total RNAs of macrophages after treatment were extracted for real-time PCR analysis with M1 signature genes (such as CD86, IL12, IL15, IL6, IL1B, IFN1B, and so on) and M2 signature genes (MRC1, CD163, IL10, TGFB1, and so on); details are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Individual gene expression was normalized with the housekeeping gene GAPDH and compared with gene expression level from healthy human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

Ex vivo NK cell activation mediated by LNP-CDN-induced activation of macrophages.

One million (106) NK cells were cultured with 4 ml of supernatants collected from autologous macrophages previously treated with PBS or LNP-CDN for 18 h in 60 mm culture dishes. NK cells were collected by centrifuging at 500g for 5 min at 4 °C. After the addition of autologous tumour cells (E:T = 20:1) for another 16 h, NK cells were collected from the supernatants for ELISA assay of IFN-γ and Gzmb. Anti-human NKG2D, anti-human Nkp46 and anti-human FcγRIII monoclonal Abs were stained as surface markers of NK activation and the intracellular expression of IFN-γ was determined by flow cytometry after ex vivo stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-ionomycin cocktail.

The cytotoxicity and ADCC effects of NK cells were assessed in the presence of human IgG1 isotype, anti-human PD-L1, avelumab (10 μg ml−1) or avelumab F(ab’)2. The effector to target cell ratios were titrated and a ratio of 20:1 was used throughout the experiment.

Statistics and reproducibility.

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (2016) and Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software). Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-tests were conducted for comparisons between two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test was performed to compare more than two groups. The survival assay was analysed using a log-rank test. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were repeated three times independently with similar results.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The scRNA-seq data are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession no. GSE164487. The bulk messenger RNA-seq data are available in the GEO under accession no. GSE179783. Source data are provided with this paper. The authors declare that other data supporting the findings of this study are available within this article and its supplementary information; all additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (no. 1R01CA264102-01 to D.Z.) and Wake Forest Comprehensive Cancer Center no. P30 CA01219740. W.Z. is supported by the Hanes and Willis Family Professorship and a Fellowship from the National Foundation for Cancer Research. A.A.H is supported by funding from the Department of Veteran’s Affairs (no. 2I01BX002559-07) and from the National Institutes of Health (no. 1R01CA244212-01A1). We thank W. Cui, L. Craddock and J. Chou of the Cancer Genomics shared Resource for conducting the scRNA-seq. We thank L. McWilliams, Biorepository Coordinator, for handling and delivering the patient samples. We also thank R. Singh, Cancer Biology, X. Yuan and C. Arledge, Biomedical Engineering, for technical and collegial support. We acknowledge the use of Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com) templates, which are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), to compile Fig. 6a.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-021-01032-w.

Additional information

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-021-01032-w.

Peer review information Nature Nanotechnology thanks Jinming Gao, Daniel Sterman and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zamboni MM, da Silva CT Jr., Baretta R, Cunha ET & Cardoso GP Important prognostic factors for survival in patients with malignant pleural effusion. BMC Pulm. Med. 15, 29 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murthy P et al. Making cold malignant pleural effusions hot: driving novel immunotherapies. Oncoimmunology 8, e1554969 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgensztern D, Waqar S, Subramanian J, Trinkaus K & Govindan R Prognostic impact of malignant pleural effusion at presentation in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 7, 1485–1489 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Thoracic Society. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162, 1987–2001 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stathopoulos GT & Kalomenidis I Malignant pleural effusion: tumor-host interactions unleashed. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186, 487–492 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lievense LA et al. Pleural effusion of patients with malignant mesothelioma induces macrophage-mediated T cell suppression. J. Thorac. Oncol. 11, 1755–1764 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnenberg AD, Luketich JD & Donnenberg VS Secretome of pleural effusions associated with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and malignant mesothelioma: therapeutic implications. Oncotarget 10, 6456–6465 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornelissen R et al. Extended tumor control after dendritic cell vaccination with low-dose cyclophosphamide as adjuvant treatment in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193, 1023–1031 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy V, Katzman D & Sterman DH Intrapleural immunotherapy: an update on emerging treatment strategies for pleural malignancy. Clin. Respir. J. 13, 272–279 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanna S et al. Malignant mesothelioma effusions are infiltrated by CD3(+) T cells highly expressing PD-L1 and the PD-L1(+) tumor cells within these effusions are susceptible to ADCC by the anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab. J. Thorac. Oncol. 11, 1993–2005 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng YH et al. PD-L1 expression of tumor cells, macrophages, and immune cells in non-small cell lung cancer patients with malignant pleural effusion. J. Thorac. Oncol. 13, 447–453 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghanim B et al. Tumour cell PD-L1 expression is prognostic in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the impact of C-reactive protein and immune-checkpoint inhibition. Sci. Rep. 10, 5784 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassan R et al. Efficacy and safety of avelumab treatment in patients with advanced unresectable mesothelioma: phase 1b results from the JAVELIN Solid Tumor Trial. JAMA Oncol. 5, 351–357 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alley EW, Katz SI, Cengel KA & Simone CB II Immunotherapy and radiation therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 6, 212–219 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakker W, Nijhuis-Heddes JM & van der Velde EA Post-operative intrapleural BCG in lung cancer: a 5-year follow-up report. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 22, 155–159 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanagawa H et al. Intrapleural instillation of interferon gamma in patients with malignant pleurisy due to lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 45, 93–99 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sartori S et al. Prospective randomized trial of intrapleural bleomycin versus interferon alfa-2b via ultrasound-guided small-bore chest tube in the palliative treatment of malignant pleural effusions. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 1228–1233 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goey SH et al. Intrapleural administration of interleukin 2 in pleural mesothelioma: a phase I–II study. Br. J. Cancer 72, 1283–1288 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnenberg AD, Luketich JD, Dhupar R & Donnenberg VS Treatment of malignant pleural effusions: the case for localized immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 7, 110 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barber GN STING: infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 760–770 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo SR et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing mediates innate immune recognition of immunogenic tumors. Immunity 41, 830–842 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X & Chen ZJ Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 339, 786–791 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng L et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon-dependent antitumor. Immun. Immunogenic Tumors Immun. 41, 843–852 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baird JR et al. Radiotherapy combined with novel STING-targeting oligonucleotides results in regression of established tumors. Cancer Res. 76, 50–61 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shae D et al. Endosomolytic polymersomes increase the activity of cyclic dinucleotide STING agonists to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 269–278 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park CG et al. Extended release of perioperative immunotherapy prevents tumor recurrence and eliminates metastases. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaar1916 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L et al. Hydrolysis of 2’3’-cGAMP by ENPP1 and design of nonhydrolyzable analogs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 1043–1048 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato K et al. Structural insights into cGAMP degradation by Ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1. Nat. Commun. 9, 4424 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onyedibe KI, Wang M & Sintim HO ENPP1, an old enzyme with new functions, and small molecule inhibitors-A STING in the tale of ENPP1. Molecules 24 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belli SI, van Driel IR & Goding JW Identification and characterization of a soluble form of the plasma cell membrane glycoprotein PC-1 (5’-nucleotide phosphodiesterase). Eur. J. Biochem. 217, 421–428 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuertes MB et al. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8+ dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 208, 2005–2016 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond MS et al. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1989–2003 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulen MF et al. Signalling strength determines proapoptotic functions of STING. Nat. Commun. 8, 427 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerboni S et al. Intrinsic antiproliferative activity of the innate sensor STING in T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 214, 1769–1785 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J et al. Type I IFN protects cancer cells from CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity after radiation. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 4224–4238 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broz ML et al. Dissecting the tumor myeloid compartment reveals rare activating antigen-presenting cells critical for T cell immunity. Cancer Cell 26, 938 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laoui D et al. The tumour microenvironment harbours ontogenically distinct dendritic cell populations with opposing effects on tumour immunity. Nat. Commun. 7, 13720 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spranger S, Dai D, Horton B & Gajewski TF Tumor-residing Batf3 dendritic cells are required for effector T cell trafficking and adoptive T cell therapy. Cancer Cell 31, 711–723 e714 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabatino M et al. Generation of clinical-grade CD19-specific CAR-modified CD8+ memory stem cells for the treatment of human B-cell malignancies. Blood 128, 519–528 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gattinoni L, Speiser DE, Lichterfeld M & Bonini C T memory stem cells in health and disease. Nat. Med. 23, 18–27 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gattinoni L Memory T cells officially join the stem cell club. Immunity 41, 7–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou T et al. IL-18BP is a secreted immune checkpoint and barrier to IL-18 immunotherapy. Nature 583, 609–614 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott AC et al. TOX is a critical regulator of tumour-specific T cell differentiation. Nature 571, 270–274 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bosi A et al. Natural killer cells from malignant pleural effusion are endowed with a decidual-like proangiogenic polarization. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2438598 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vacca P et al. NK cells from malignant pleural effusions are not anergic but produce cytokines and display strong antitumor activity on short-term IL-2 activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 550–561 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dahan R et al. FcgammaRs modulate the anti-tumor activity of antibodies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. Cancer Cell 28, 285–295 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ & Sharpe AH The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev. Immunol. 23, 515–548 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinter AL et al. The common gamma-chain cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 induce the expression of programmed death-1 and its ligands. J. Immunol. 181, 6738–6746 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bald T et al. Immune cell-poor melanomas benefit from PD-1 blockade after targeted type I IFN activation. Cancer Disco. 4, 674–687 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhupar R et al. Characteristics of malignant pleural effusion resident CD8(+) T cells from a heterogeneous collection of tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeLong P et al. Regulatory T cells and cytokines in malignant pleural effusions secondary to mesothelioma and carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 4, 342–346 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu MF et al. The M1/M2 spectrum and plasticity of malignant pleural effusion-macrophage in advanced lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 70, 1435–1450 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo M et al. Autologous tumor cell-derived microparticle-based targeted chemotherapy in lung cancer patients with malignant pleural effusion. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaat5690 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J, Yang Y & Huang L Calcium phosphate nanoparticles with an asymmetric lipid bilayer coating for siRNA delivery to the tumor. J. Control. Release 158, 108–114 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Y et al. An inhalable nanoparticulate STING agonist synergizes with radiotherapy to confer long-term control of lung metastases. Nat. Commun. 10, 5108 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The scRNA-seq data are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession no. GSE164487. The bulk messenger RNA-seq data are available in the GEO under accession no. GSE179783. Source data are provided with this paper. The authors declare that other data supporting the findings of this study are available within this article and its supplementary information; all additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.