Abstract

Existing quinolones are known to target the type II topoisomerases in bacteria. In order to determine which of these targets are of key importance in Streptococcus pneumoniae treated with BMS-284756 (T-3811ME), a novel des-F(6) quinolone, resistant mutants were selected in several steps of increasing resistance by plating pneumococci on a series of blood agar plates containing serial twofold-increasing concentrations of drug. After incubation, colonies that arose were selected and passaged twice on antibiotic-containing media at the selection level. Mutants generally showed increases in resistance of four- to eightfold over the prior level of susceptibility. Mutants in the next-higher level of resistance were selected from the previous round of resistant mutants. Subsequently, chromosomal DNA was prepared from parental (R6) pneumococci and from at least three clones from each of four levels of increasing antibiotic resistance. Using PCR primers, 500- to 700-bp amplicons surrounding the quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR) of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes were prepared from each strain. Internal primers were used to sequence both DNA strands in the regions of approximately 400 bp centered on the QRDR. Mutations identified with increasing levels of resistance included changes in GyrA at Ser-81 and Glu-85 and changes in ParC at Ser-79 and Asp-83. Changes in GyrB and ParE were not observed at the levels of resistance obtained in this selection. The resistance to comparator quinolones (levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and moxifloxacin) also increased in four- to eightfold steps with these mutations. The intrinsically greater level of antibacterial activity and thus lower MICs of BMS-284756 observed at all resistance levels in this study may translate to coverage of these resistant pneumococcal strains in the clinic.

Members of the fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics exert their antibacterial effects through inhibition of the bacterial type II topoisomerases DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV (6, 15). DNA gyrase, which introduces negative supercoils into DNA, is a tetramer composed of two subunits of GyrA and two of GyrB (20). Topoisomerase IV is believed to participate in chromosome separation after replication and is a tetramer of two ParC and two ParE subunits (8, 18). Both enzymes participate in maintaining an overall level of DNA supercoiling that is essential to chromosome integrity, cell physiology, and viability (33, 40). The killing action of quinolones is currently hypothesized to take place through the trapping of DNA-protein cleaved complexes, with a subsequent release of lethal double-stranded DNA breaks (4, 6, 7, 32).

Resistance to the fluoroquinolones is very frequently associated with amino acid changes in key highly conserved residues in the GyrA subunit or the ParC subunit (13, 14, 31). In the case of gyrase, these areas where changes are frequently found are believed to lie along a helical surface of the gyrase that interacts with the DNA (3) and have been designated the quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR) (14, 15, 31, 41). The analogous QRDR in ParC is highly similar in amino acid composition (8, 14) and may interact with DNA similarly to gyrase, although no crystal structure has been published to date. Less frequently, changes can also be seen in quinolone-resistant mutants in regions of the GyrB and ParE subunits (14, 28). Efflux has also been implicated in quinolone resistance in bacteria, including Streptococcus pneumoniae (2).

Studies with earlier fluoroquinolones indicated that resistant gram-positive cocci had topoisomerase IV as the primary target (9, 17, 22, 23), in contrast to gram-negative organisms, for which initial resistance mutations arose in GyrA (13, 14, 39). However, sparfloxacin, gemifloxacin, and moxifloxacin were found to initially select GyrA mutations in S. pneumoniae, indicating that structural modifications of this class of drugs could impact the primary target affinity (12, 25, 30, 38). Clinafloxacin was shown to have comparable albeit somewhat unequal targeting against both gyrase and topoisomerase and also exhibited a preference for first-step mutations against GyrA (26). With the increased understanding of the structure-activity relationships among the fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics (1, 5), it has been possible to greatly improve the intrinsic activity of these compounds against gram-positive pathogens (15, 16).

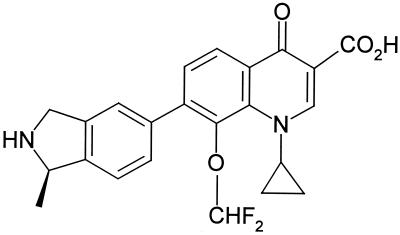

The new quinolone BMS-284756 (T-3811ME) lacks the classical C-6 fluorine of fluoroquinolones (35). This C-6 fluorine was believed to be essential for the enhanced potency of recent fluoroquinolones (5). In BMS-284756, the C-8 O-methoxyl group, believed to be important in improved activity (19), has been modified to a difluoro-methoxy substituent, and the fluorine on the 6 position has been removed (Fig. 1). BMS-284756 has a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity, with exceptional activity against gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. pneumoniae and the staphylococci) and intracellular pathogens, good activity against anaerobes, and the potential to cover quinolone-resistant pathogens in the clinic (10).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of BMS-284756, a des-F(6) quinolone.

The gram-positive pathogen S. pneumoniae is a key pathogen for coverage by this compound. S. pneumoniae is a leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia, as well as meningitis, sinusitis, and otitis. It was desirable to determine the rate and types of mutations that might lead to increased resistance to BMS-284756 in the pneumococcus. In the present study, the stepwise-increased resistance mutations selected by BMS-284756 were characterized, and the effect on the MIC of the selecting drug and other key quinolone compounds was determined. Chromosomal DNA from these resistant mutants was used as a source to amplify and sequence the QRDR of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE to follow mutational changes resulting from the selection of resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth media.

S. pneumoniae, strain R6, was used as the parent strain. Liquid cultures were grown at 37°C in Todd-Hewitt–0.5% yeast extract (YE) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with 400 μg of fresh, filter-sterilized sodium bicarbonate solution (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo)/ml. Solid media for maintenance was Trypticase soy agar (Difco) with 4% defibrinated sheep red blood cells (SRBC) (Remel Microbiology Products, Lenexa, Kans.) Selection for resistant mutants was done on Todd-Hewitt–0.5% YE and 1.5% agar, cooled to 50°C, with addition of 4% SRBC and appropriate concentrations of the selecting antibiotic.

Stepwise mutant selection.

A 50-ml culture of pneumococci (either parental or drug-resistant isolate) was grown into late log phase in Todd-Hewitt–0.5% YE broth and sodium bicarbonate, chilled on ice, and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 12 min. at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in 2 ml of cold Todd-Hewitt broth, and 0.4 ml (ca. 4 × 109 to 8 × 109 CFU; determined by serial dilution and plate counts) was spread on the surface of several 150- by 15-mm petri plates containing two-, four-, and eightfold MICs of antibiotic in Todd-Hewitt–0.5% YE, 4% SRBC, and 1.5% agar. After incubation for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, small pneumococcal colonies were observed. The total number of colonies on the antibiotic-containing plates was used, in conjunction with the viable cell counts, to calculate the frequency of resistance. Several of these colonies were selected under a dissecting microscope with a sterile wire loop and individually streaked onto fresh Todd-Hewitt YE blood agar plates containing the concentration of selecting antibiotic (BMS-284756 or ciprofloxacin) in the agar. After 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, a colony from each of these mutants was again passaged on antibiotic-containing agar. For each resistant mutant strain selected, growth from the last plate was suspended in Todd-Hewitt–8% sterile glycerol, flash frozen in an ethanol-dry ice bath, and stored at −80°C.

An individual mutant colony selected at one level of resistance was used to select the next round of mutants at a higher MIC level using the procedure above. This iterative process led to increasingly higher-level antibiotic-resistant pneumococci with multiple mutational changes in quinolone target proteins. At each selection level, mutants appeared on plates at two- to fourfold the drug MIC of the preceding level; there were no recoverable colonies at eightfold the prior MIC at any antibiotic selection level.

MIC determinations.

BMS-284756 and analogs were obtained from Toyama Chemical Company (Toyama, Japan). Ciprofloxacin was obtained from Bayer Corporation, (West Haven, Conn.). Levofloxacin was obtained from the manufacturer or was extracted from tablets. Levofloxacin was extracted from 500-mg commercial tablets, purified by recrystallization, and determined to be >99.9% pure by high-pressure liquid chromatography analysis. Moxifloxacin was extracted from 400-mg commercial tablets, purified by recrystallization, and determined to be >99.9% pure by high-pressure liquid chromatography analysis. Compounds were solubilized in sterile water at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and stored at −80°C. MICs were determined by serial twofold dilutions of drug in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton (Difco Laboratories) broth plus Todd Hewitt (50:50) broth, with an inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU of pneumococci/ml. Results were recorded after 20 h of incubation in 5% CO2 at 37°C.

DNA sequencing.

Cultures of resistant clones were prepared by spreading thawed cells on blood agar plates and incubating them for 14 to 16 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Growth from these plates was suspended in 10 ml of Todd-Hewitt plus YE and sodium bicarbonate at 37°C, and at an A610 of 0.5 to 0.7, cells were collected at 4,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were resuspended in a solution containing 2.5 ml of cold 10 mM Tris-Cl and 1 mM EDTA (Sigma Chemical Co.) at pH 8.0, and 0.05% deoxycholate and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (Sigma Chemical Co) were added, with incubation for 15 min in a 37°C water bath, resulting in rapid cell lysis. Proteinase K (500 μg/ml) (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) was added for an additional 10 min, and then an equal volume of phenol-chloroform- isoamyl alcohol solution (Gibco BRL) was added followed by gentle mixing by inversion. After separation of the layers by centrifugation, the aqueous layer was twice extracted with chloroform, followed by addition of a 0.3 M final concentration of sodium acetate and two volumes of ethanol. The DNA pellet was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min and was washed serially with 70% ethanol and 95% ethanol before final drying and resuspension in 0.05 ml of water.

Regions of 0.5 to 0.7 kb surrounding the QRDR of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE were amplified with appropriate custom primers (Table 1) (Gibco Life Technologies) by PCR with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) using chromosomal DNA from parental R6 and resistant mutant strains. Internal sequencing primers (Table 1) for both the forward and reverse strands were used to sequence the DNA on an ABI Prism 3100 capillary sequencing machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) using BigDye Dye Terminator chemistry. Approximately 300 to 400 base pair reads centered on the QRDR were obtained on both strands. In addition, sets of gene-flanking amplifying primers and sequencing primers spaced every 400 bp were used for full-length sequencing of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE of the R6 parent strain and the fourth-level resistant strain. DNA sequence data were analyzed using either Sequencher (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.) or the LaserGene analysis suite (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.). Sequence reads were assembled with Sequencher or the Seqman program and converted to amino acid sequence using the Editseq program. Multiple protein alignments of the QRDR areas and the full-length translated gene sequences were performed with the MegAlign program using the Clustal algorithm.

TABLE 1.

DNA primers used for PCR amplification and internal sequencing primers of the QRDR in the four quinolone target genes of S. pneumoniae R6 parental and resistant mutants

| Descriptiona | Sequence |

|---|---|

| gyrA-amplifying primer—forward (bp 1–27) | 5′ ATGCAGGATAAAAATTTAGTGAATGTC |

| gyrA-amplifying primer—reverse (bp 842–868) | 5′ ACCATGTAAGGAAATTCTGTAACAACG |

| gyrA-sequencing primer—forward (bp 187–203) | 5′ GCTTAAAACCTGTTCAC |

| gyrA-sequencing primer—reverse (bp 464–480) | 5′ TATCACGAAGCATTTCC |

| gyrB-amplifying primer—forward (bp 910–936) | 5′ GATTATGCTCGTAAGAATAAGTTACTG |

| gyrB-amplifying primer—reverse (bp 1718–1744) | 5′ GAATAGTCGGTTTGGTACGACCTTCAC |

| gyrB-sequencing primer—forward (bp 1318–1344) | 5′ TCAGCCAAATCTGGTCG |

| gyrB-sequencing primer—reverse (bp 1621–1638) | 5′ CTTGACACCATAGATTGG |

| parC-amplifying primer—forward (bp 1–27) | 5′ ATGTCTAACATTCAAAACATGTCCCTG |

| parC-amplifying primer—reverse (bp 780–806) | 5′ TTCAATTTCAGTCTTGGAACGAACAAC |

| parC-sequencing primer—forward (bp 169–185) | 5′ TTCGTGATGGGTTGAAG |

| parC-sequencing primer—reverse (bp 435–451) | 5′ GCAATTTCAGACAAACG |

| parE-amplifying primer—forward (bp 941–967) | 5′ ACCTTGAAGGTTCAGACTATCGTGAGG |

| parE-amplifying primer—reverse (bp 1770–1797) | 5′ TTCTGGGTTCATGGTTGTTTCCCAGAGC |

| parE-sequencing primer—forward (bp 1167–1183) | 5′ TGAAGCAGCACGTAAGG |

| parE-sequencing primer—reverse (bp 1487–1507) | 5′ TAATGATCTTATCATAGTTGG |

Base pairs are numbered from the beginning of the gene.

DNA transformation.

DNA containing the full-length double-mutant gyrA or parC gene was generated by PCR using chromosomal DNA of the fourth-level resistance mutant and oligonucleotide primers which flanked the respective gene sequences. S. pneumoniae R6 was grown to an A610 of 0.25 in Todd-Hewitt–YE and flash frozen in aliquots of 1 ml in 8% glycerol at −80°C. For use, cells were slowly thawed and diluted 1:10 in a solution containing Todd-Hewitt–0.5% YE, 2% bovine serum albumin, 10 mM CaCl2, and synthetic competence peptide CSP-1 (Research Genetics, Huntsville, Ala.) at 100 ng/ml (11). After 10 min, 0.2 ml of the diluted cells received 1 μg of DNA generated by PCR with either the gyrA or parC genes. Identically treated competent control cells that received no DNA were also included in each experiment. After incubation for 2.5 h at 37°C, the cells were plated on Todd-Hewitt–YE agar plates with appropriate concentrations of selecting antibiotic. In the case of GyrA, BMS-284756 at concentrations of 0.06, 0.12, and 0.25 μg/ml was used; for ParC, ciprofloxacin at concentrations of 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml was employed. The plates were incubated for 40 to 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells that received DNA typically yielded 300 to 400 resistant colonies per plate, whereas control cells without transforming DNA resulted in no colonies recovered on antibiotic-containing agar. Several transformant colonies were picked under a dissecting microscope and passaged twice on Todd-Hewitt–YE with antibiotic concentrations identical to those used in the initial transformation selection. Cells were collected via a wire loop from the plates, suspended in Todd-Hewitt plus 8% glycerol, and frozen at −80°C. Cells were thawed and grown in liquid Todd-Hewitt–YE, and MICs were determined as described above.

RESULTS

In order to obtain a reasonable number of resistant mutants, it was necessary to place high numbers of organisms (ca. 4 × 109 to 8 × 109 CFU) on the surfaces of large (150-mm-diameter) blood agar plates containing antibiotic. Mutants were isolated at drug levels of two- to fourfold above the MIC at any given resistance level, but higher drug concentrations did not yield resistant colonies. Initial development of resistance to BMS-284756 was estimated to be in the 1 × 10−9 to 2 × 10−9 range at 4 times the MIC and less than 8 × 10−9 at 8 times the MIC, from comparison of the number of resistant colonies obtained versus the total number of organisms spread on the selecting plate. In contrast, a similar number of pneumococci spread on a ciprofloxacin plate at 4 times the MIC resulted in isolation of resistant mutants at frequencies of 2 × 10−7 to 1 × 10−8.

Using the des-F(6) fluoroquinolone BMS-284756 as a selection agent, it was possible to define four discrete steps to high-level resistance (i.e., above the anticipated breakpoint) for S. pneumoniae R6. Table 2 illustrates the MICs of four quinolone compounds obtained for the parent strain and for three independent mutants selected at each of four levels of increasing resistance to BMS-284756. In contrast, when ciprofloxacin was used as the selecting antibiotic, it yielded high-level ciprofloxacin resistance mutants (with resistance above the MIC breakpoint) after two selection steps (Table 3). When used as a selecting agent, BMS-284756 remained more potent at all levels of resistance than the three other comparator quinolones tested in the present study, with the exception of ciprofloxacin at the highest level of resistance obtained, where it was equipotent. The two levels of ciprofloxacin-selected resistance mutants retained their susceptibility to BMS-284756, due to an intrinsic potency of the des-F(6) quinolone that was greater than that of earlier compounds.

TABLE 2.

MICs of comparator quinolones for BMS-284756-selected mutants

| Strain group and IDa | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS-284756 | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| R6 parent | 0.015 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.125 |

| 1st level—A | 0.125 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| 1st level—B | 0.06 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| 1st level—C | 0.06 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| 2nd level—A | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 4 |

| 2nd level—B | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 4 |

| 2nd level—C | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 4 |

| 3rd level—A | 2 | 16 | 16 | 8 |

| 3rd level—B | 2 | 16 | 16 | 4 |

| 3rd level—C | 2 | 16 | 16 | 4 |

| 4th level—A | 16 | 32 | 64 | 64 |

| 4th level—B | 8 | 16 | 64 | 64 |

| 4th level—C | 16 | 16 | 64 | 64 |

ID, identification. Strains were derived from S. pneumoniae R6 as described in Materials and Methods. Each level of increasing strain resistance is derived from the preceding level of lower resistance by selection with BMS-284756. At least three independent mutants (designated A, B, and C) at each level were selected and subjected to MIC testing.

TABLE 3.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations of key quinolone antibiotics against ciprofloxacin-selected mutants

| Strain group and IDa | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | BMS-284756 | Levofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| R6 parent | 0.5 | 0.015 | 0.5 | 0.125 |

| 1st level—A | 2 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.25 |

| 1st level—B | 2 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.25 |

| 1st level—C | 2 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.25 |

| 2nd level—A | 16 | 0.25 | 16 | 2 |

| 2nd level—B | 16 | 0.5 | 16 | 2 |

| 2nd level—C | 16 | 0.5 | 16 | 2 |

ID, identification. Strains were derived from S. pneumoniae R6 as described in Materials and Methods. Each level of increasing strain resistance is derived from the preceding level of lower resistance by selection with ciprofloxacin. Three independent mutants (A, B, and C) for each level are presented.

Sequencing of the QRDR of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes from each of three independent mutants at each resistance level revealed that in all cases, a change in the amino acid sequence at the previously reported “hot spots” for quinolone resistance could account for the observed MIC changes (Table 4). In the case of BMS-284756-selected mutants, the initial change at the first level was observed in the gyrA sequence, which changed at Ser-81 to either Phe or Tyr. The second-level BMS-284756 resistance mutants had an additional change in ParC at Ser-79, to Phe. Third-level BMS-284756 resistance mutants had a second mutation in GyrA at Glu-85, to Lys or Gly, and fourth-level BMS-284756 high-resistance mutants acquired a second change in ParC at Asp-83, to Gly. No changes were observed in the present study in the sequences of GyrB or ParE in regions where mutations have been previously reported that are associated with quinolone resistance (24, 28).

TABLE 4.

Changes in the QRDR of GyrA and ParC in BMS-284756-selected resistance mutantsa

| Strain or mutant group | Mutations in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| GyrAb | ParCc | |

| R6 parent | S81, E85 | S79, D83 |

| 1st level resistant | S81F, E85 S81Y, E85 | S79, D83 |

| 2nd level resistant | S81Y, E85 | S79F, D85 |

| 3rd level resistant | S81Y, E85K S81Y, E85G | S79F, D85 |

| 4th level resistant | S81Y, E85K | S79F, D85G |

No changes were observed in GyrB or ParE in the present set of mutants.

Amino acid position and mutations of key amino acids in the QRDR of the GyrA protein, as derived from DNA sequences at each resistance level. Amino acid changes were determined for each of three independent isolates, and where variants among the mutants were present, both changes at that level are shown.

Amino acid positions and mutations of the QRDR of the ParC protein, as derived from DNA sequence at each resistance level. Amino acid changes were determined for each of three independent isolates.

In order to verify that no additional changes had occurred outside of the QRDR, the full-length sequences of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes of both the parent R6 and the final, fourth-level resistance mutant were compared. In the case of the translated protein sequences of gyrA and parC, the only differences between the parent and fourth-level mutant were the two amino acid changes previously seen in each of these proteins from the QRDR sequence data. The derived GyrB and ParE protein sequences were identical between the parent strain and that in the fourth level of resistance.

The two levels of resistance selected with ciprofloxacin in the present study yielded an initial change in ParC at Ser-79 to Tyr, followed by a second-level mutation at Ser-81 of GyrA to Phe (Table 5). These are identical to changes previously reported upon selection of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants (23). Again, in this study, no changes in either the GyrB or ParE QRDR were observed, although others have reported mutational changes in these proteins upon resistance selection after multiple serial passages in antibiotic-containing broth (C. L. Clark, K. Nagai, T. A. Davies, B. Dewasse, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1041, 2000).

TABLE 5.

Changes in the QRDR of GyrA and ParC in quinolone-resistant mutants selected with ciprofloxacina

| Strain or mutant group | Mutation(s) in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| GyrAb | ParCc | |

| R6 parent | S81 | S79 |

| 1st level resistant | S81 | S79Y |

| 2nd level resistant | S81F, S81Y | S79Y |

No changes were observed in GyrB or ParE in the present set of mutants.

Amino acid sequence and changes at key amino acids within the QRDR of the GyrA protein, as derived from DNA sequence. Changes were sequenced for three isolates.

Amino acid sequences and changes of the QRDR of the ParC protein, as derived from the DNA sequence. Changes were sequenced for three isolates.

In order to characterize the effects of the double mutants of gyrA and parC without the confounding effects of other mutations in the background, the gyrA gene (with corresponding Ser81→Phe and Glu85→Lys mutations in GyrA) and the parC gene from the fourth-level mutant (with corresponding Ser79→Phe and Asp83→Gly mutations in ParC) were amplified by PCR. These genes were transformed into the parental R6 strain and selected on appropriate antibiotics at several concentrations, and the resulting resistant transformants were tested against a battery of quinolone compounds (Table 6). Both double mutants individually conferred high-level resistance to the tested quinolone compounds, albeit not to the degree observed in the highest-level mutants that possessed both gyrA and parC double mutations. Of particular note is the fact that the double ParC mutation was associated with higher drug MICs, regardless of whether the primary resistance mutation selected by a drug was in GyrA (BMS-284756 and moxifloxacin) or ParC (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin).

TABLE 6.

MICs of comparator quinolones for the parent strain and transformants that were constructed with either GyrA or ParC double-mutation DNA

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS- 284756 | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| R6 parent | 0.015 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.125 |

| Double GyrA transformant | 0.5 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| Double ParC transformant | 1 | 16 | 16 | 4 |

DISCUSSION

The potent intrinsic activity of the novel des-F(6) quinolone BMS-284756 against gram-positive pathogens suggests that it would find a place in the clinic in treatment of serious infections, including those associated with S. pneumoniae (10, 35). As can be seen in Table 2, the MICs for fully susceptible S. pneumoniae are the lowest of those of the four tested compounds. The present study was designed to explore in the laboratory the levels of decreased drug susceptibility and the associated resistance mutations that arose in the pneumococcus against BMS-284756. The study determined the types of mutations that were selected in the gyrase and topoisomerase drug targets and the levels of resistance that could be achieved with single and multiple mutations in these targets. In the present study, four levels of additive resistance to BMS-284756 were selected. In all cases, the increased resistance could be accounted for by changes within the QRDR of two target protein subunits, GyrA and ParC. Sequencing of the initial parent strain and final fourth-level resistance mutant found no additional changes outside the QRDR for gyrA or parC and no changes in the translated sequences of gyrB and parE. It is presumed that since the fourth-level strain was derived from the preceding resistance levels, any additional sequence changes associated with resistance would have carried through to the fourth level.

Using BMS-284756 as the selecting agent, it was observed that the initial-level mutant colonies appeared on drug-containing agar plates at a 10- to 50-fold-lower rate than was observed with ciprofloxacin as the selecting agent. Lower levels of resistance development have also been reported for several recent compounds, among which are gemifloxacin, clinafloxacin, sparfloxacin, and moxifloxacin (12, 25, 26, 30). The first-level mutations with an increase in the BMS-284756 MIC of four- to eightfold all had first-level mutational changes in the GyrA protein at Ser-81, a well-known quinolone “hot spot” for resistance (14, 36, 38, 39). Thus, BMS-284756 joins other recent quinolone compounds, such as sparfloxacin, gemifloxacin, and moxifloxacin, in having GyrA as the initial resistance target (12, 25, 30). In contrast, ciprofloxacin initially selected ParC changes, followed by GyrA changes at the second level of resistance, as previously reported (23).

The second-level resistance mutants, selected with BMS-284756 from the first-level Ser→Tyr mutant, had a two- to fourfold MIC increase in BMS-284756 resistance over the first-level resistance group and had a previously described QRDR change in the ParC protein at position 79 (Ser→Phe) (17, 22, 23, 29, 34, 36, 38). The other three drugs tested showed significant (8- to 16-fold) changes in their MICs when this mutation was added to the initial GyrA change. As expected, given the identical mutations, very similar MIC changes were also observed in the ciprofloxacin-selected mutants, which had initial ParC first-level and subsequent GyrA second-level mutations. In contrast, the sparfloxacin MIC has been reported to be unaffected by ParC single mutations (12, 25).

The third level of resistance to BMS-284756 that was selected revealed a second change in the GyrA protein in the QRDR area of these strains. Double mutations in the GyrA protein at these amino acid residues have been reported for other quinolone-selected mutants (17, 22, 23, 29, 34, 36, 38). The additional change in GyrA at this level appears to preferentially affect resistance to BMS-284756, compared to that to the other tested compounds. The fourth-level mutant, which had the highest level of resistance obtained in this study, was a result of the addition of a second, previously reported change in the topoisomerase IV ParC subunit (17). It is in these later-step mutants that the pneumococcus achieves a level of resistance that would be greater than the anticipated MIC breakpoint of susceptibility for this compound against pneumococci, based on reported concentrations at which 90% of the pneumococci were inhibited (10) and preliminary human dosage and pharmacokinetic information for BMS-284756 (D. Grasella, D. Gajjin, A. Bello, Z. Ge, and L. Christopher, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 2259, 2000). Mean minimal concentrations of drug in serum after single doses of 400 and 800 mg are 6.4 and 10.9 μg/ml, respectively, with a mean half-life of 12 to 13 h.

The effect of either the GyrA or ParC single mutations suggested that it would be of interest to investigate the effects of the double mutations in GyrA and ParC individually. Using genetic transformation, S. pneumoniae strains were constructed with GyrA (Ser 81→Phe, Glu85→Lys) and separately with a similar construct of ParC (Ser79→Phe, Asp83→Gly) in the parent background. The effects of the individual target protein double mutations were tested against the quinolone panel, and either double mutant was found to mediate substantial increases in MICs of all of the tested quinolones. This result and the results for the single gyrA and parC mutants were surprising in that despite the predilection for selecting gyrA mutations prior to parC mutations, both BMS-284756 and moxifloxacin induced equal if not slightly higher levels of resistance in the presence of either single- or double-mutant parC with the parental susceptible gyrA allele. This may indicate that BMS-284756 and moxifloxacin may have a more balanced affinity for the two target enzymes, with a slight initial preference for GyrA as an initial target. A similar explanation of dual targeting has been proposed recently for gemifloxacin (12). However, it has been noted that in vitro studies with purified pneumococcal gyrase and topoisomerase indicate that at least under these conditions, topoisomerase IV is always more sensitive to inhibition by all quinolones tested to date, regardless of the primary target for resistant mutant selection by individual compounds (21, 27). Further work is needed to understand this anomalous behavior and the in vivo mechanisms of cell killing by quinolones.

It has been suggested that potent quinolones may be less likely to select resistance due to their ability to kill both parent organism and less-susceptible single-step mutants (37). The present data would suggest that the high level of intrinsic activity of BMS-284756, along with the multiple mutational steps necessary for high-level resistance, will make BMS-284756 useful in minimizing the selection of quinolone-resistant mutants. This compound will also have utility in many cases where preexisting low-level quinolone resistance, selected by the use of quinolones with borderline activity, is present in community populations of S. pneumoniae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Hale for comments and Brian Dougherty, French Lewis, and Patricia Poundstone of the Applied Genomics Department for their able assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alovera F L, Pan X-S, Morris J E, Manzo R H, Fisher L M. Engineering the specificity of antibacterial fluoroquinolones: benzenesulfonamide modifications at C-7 of ciprofloxacin change its primary target in Streptococcus pneumoniae from topoisomerase IV to gyrase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:320–325. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.320-325.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenwald N P, Gill M J, Wise R. Prevalence of putative efflux mechanism among fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2032–2035. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabral J H, Jackson A P, Smith C V, Shikotra N, Maxwell A, Liddington R C. Crystal structure of the breakage-reunion domain of DNA gyrase. Nature. 1997;388:903–906. doi: 10.1038/42294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C-R, Malik M, Snyder M, Drlica K. DNA gyrase and topoisomerase on the bacterial chromosome: quinolone-induced DNA cleavage. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:627–637. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domagala J M. Structure-activity and structure-side-effect relationships for the quinolone antibacterials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:685–706. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377–392. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drlica K. Mechanism of fluoroquinolone action. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:504–508. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA topoisomerase IV as a quinolone target. Curr Opin Anti-Infect Investig Drugs. 1999;1:435–442. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Crouzet J. Analysis of gyrA and grlA mutations in stepwise-selected ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1554–1558. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung-Tomc J C, Minassian B, Kolek B, Juczko E, Alekunes L, Stickle T, Washo T, Gradelski E, Valera L, Bonner D P. Antibacterial spectrum of a novel des-fluoro(6)quinolone, BMS-284756. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3351–3356. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3351-3356.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havarstein L S, Coomaraswamy G, Morrison D A. An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11140–11144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaton V J, Ambler J E, Fisher L M. Potent antipneumococcal activity of gemifloxacin is associated with dual targeting of gyrase and toposiomerase IV, an in vivo target preference for gyrase and enhanced stabilization of cleavable complexes in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3112–3117. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3112-3117.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooper D C. Bacterial topoisomerases, anti-topoisomerases and anti-topoisomerase resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S54–S63. doi: 10.1086/514923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper D C. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Drug Resist Updates. 1999;2:38–55. doi: 10.1054/drup.1998.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper D C. Mode of action of fluoroquinolones. Drugs. 1999;58(Suppl. 2):6–10. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooper D C. Mechanisms of action of antimicrobials: focus on fluoroquinolones. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(Suppl. 1):S9–S15. doi: 10.1086/319370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janoir C, Zeller V, Kitzis M-D, Moreau N J, Gutmann L. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2760–2764. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato J-I, Nishimura Y, Imamura R, Niki H, Hiraga S, Suzuki H. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell. 1990;63:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90172-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu T, Zhao X, Drlica K. Gatifloxacin activity against quinolone-resistant gyrase: enhancement of bacteriostatic and bacteriocidal activities by the C-8-O-methoxy group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2969–2974. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuuchi K, Mizuuchi M, O'Dea M H, Gellert M. Cloning and simplified purification of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase A and B proteins. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9199–9201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrisey I, George J T. Purification of pneumococcal type II topoisomerases and inhibition by gemifloxacin and other quinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45(Suppl. S1):101–106. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.suppl_3.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz R, De la Campa A G. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of quinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan X-S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding DNA topoisomerase IV: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4060–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4060-4069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Targeting of DNA gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae by sparfloxacin: selective targeting of gyrase or topoisomerase IV by quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;41:471–474. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV are dual targets of clinafloxacin action in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV: overexpression, purification and differential inhibition by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1129–1136. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perichon B, Tankovic J, Courvalin P. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1166–1167. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pestova E, Beyer R, Cianciotto N P, Noskin G A, Peterson L R. Contribution of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase mutations in Streptococcus pneumoniae to resistance to novel fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2000–2004. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pestova E, Millichap J J, Noskin G A, Peterson L R. Intracellular targets of moxifloxacin: a comparison with other fluoroquinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:583–590. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piddock L J V. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance: an update 1994–1998. Drugs. 1999;58(Suppl. 2):11–18. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snyder M, Drlica K. DNA gyrase on the bacterial chromosome: DNA cleavage induced by oxolini acid. J Mol Biol. 1984;131:287–302. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staczek P, Higgins N P. Gyrase and topo IV modulate chromosome domain size in vivo. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1435–1448. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart B A, Johnson A P, Woodford N. Relationship between mutations in parC and gyrA of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and resistance to ciprofloxacin and grepafloxacin. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:1103–1106. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-12-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahata M, Mitsuyama J, Yamashiro Y, Yonezawa M, Araki H, Todo Y, Minami S, Watanabe Y, Narita H. In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activities of T-3811ME, a novel des-F(6)-quinolone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1077–1084. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tankovic J, Perichon B, Duval J, Courvalin P. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2505–2510. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomson K S. Minimizing quinolone resistance: are the new agents more or less likely to cause resistance? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:719–723. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.6.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varon E, Janoir C, Kitzis M-D, Gutmann L. ParC and GyrA may be interchangeable initial targets of some fluoroquinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:302–306. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willmott C J, Maxwell A A. A single point mutation in the DNA gyrase A protein greatly reduces binding of fluoroquinolones to the gyrase-DNA complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:126–127. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu H-Y, Shyy S, Wang J C, Liu L F. Transcription generates positively and negatively supercoiled domains in the template. Cell. 1988;53:433–440. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1271–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]