Abstract

Somatostatin neurons in the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA/Sst) can be parsed into subpopulations that project either to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) or parabrachial nucleus (PBN). We have shown recently that inhibition of CeA/Sst-to-NST neurons increased the ingestion of a normally aversive taste stimulus, quinine HCl (QHCl). Because the CeA innervates other forebrain areas such as the lateral hypothalamus (LH) that also sends axonal projections to the NST, the effects on QHCl intake could be, in part, the result of CeA modulation of LH-to-NST neurons. To address these issues, the present study investigated whether CeA/Sst-to-NST neurons are distinct from CeA/Sst-to-LH neurons. For comparison purposes, additional experiments assessed divergent innervation of the LH by CeA/Sst-to-PBN neurons. In Sst-cre mice, two different retrograde transported flox viruses were injected into the NST and the ipsilateral LH or PBN and ipsilateral LH. The results showed that 90% or more of retrograde-labeled CeA/Sst neurons project either to the LH, NST, or PBN. Separate populations of CeA/Sst neurons projecting to these different regions suggest a highly heterogeneous population in terms of synaptic target and likely function.

Keywords: herpes simplex virus, taste, NST, PBN, amygdala, hypothalamus

Introduction

The nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) is the first central synapse of gustatory afferents originating from branches of the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves (Hamilton and Norgren 1984; Corson et al. 2012). From the NST, gustatory information is sent to the pontine parabrachial nucleus (PBN). In addition to the thalamocortical pathway, PBN gustatory efferents project to ventral forebrain nuclei such as the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and central nucleus of amygdala (CeA) (Norgren and Leonard 1971). It is well known that these same forebrain areas project back to the NST and PBN to modulate taste-evoked neural responsiveness (Cho et al. 2003; Lundy and Norgren 2004; Li and Cho 2006; Kang and Lundy 2009a). For example, activation of the LH and CeA most often produces an excitatory effect on NST taste neurons. In contrast, inhibition and excitation of PBN taste neurons occurred equally as often during LH activation, whereas CeA activation predominately inhibited PBN taste neurons. Yet, the impact of such neuromodulation on taste-guided behavior as well as the neurochemical identity of relevant descending pathways are not fully understood.

In behaving animals, electrical stimulation of the CeA was shown to increase the number of Fos-immunoreactive neurons in the NST and PBN as well as aversive taste-reactivity responses to quinine HCl (QHCl). In contrast, stimulation of the LH decreased the number of aversive responses to QHCl with little change in Fos immunoreactivity (Riley and King 2013). Although these results are suggestive of a role in taste-guided behavior to an aversive stimulus, the use of electrical stimulation is limited in that it cannot distinguish between activation of different neuronal subtypes present in the CeA and LH (Moga and Gray 1985; Moga et al. 1990a, 1990b; Broberger et al. 1998; Sakurai et al. 1998; Kim et al. 2017; McCullough et al. 2018). Thus, more work is needed to identify the anatomic substrates through which descending pathways exert their influence on ingestive behavior.

For the CeA, the identity of one such substrate is somatostatin-expressing neurons (Sst). They are a major source of descending input to taste responsive areas of the brainstem and CeA/Sst-to-NST and CeA/Sst-to-PBN projecting neurons are largely distinct from one another (Panguluri et al. 2009; Magableh and Lundy 2014; Bartonjo and Lundy 2020). We have shown recently that manipulating the neural activity of CeA/Sst-to-NST neurons altered the concentration-dependent intake of QHCl (Bartonjo et al. 2022). Specifically, licking to high concentrations of QHCl was substantially increased by optogenetic inhibition of this descending pathway compared to Control mice. This finding suggests that the ability of animals to respond appropriately to changes in the intensity of an aversive taste stimulus can be fine-tuned by descending input from CeA/Sst neurons to the NST. The extent to which increased acceptance of QHCl can be solely attributed to the CeA/Sst-to-NST pathway, however, is tentative because the CeA is interconnected with other brain regions such as LH that also innervates the NST (Ottersen 1980; Ono et al. 1985; Reppucci and Petrovich 2016; Barbier et al. 2018).

To address this uncertainty, the present study assessed whether CeA/Sst neurons that project to the NST or PBN have divergent innervation of the LH. We chose to focus on the LH because previous research implicates this region in behavioral responsiveness to QHCl (Ferssiwi et al. 1987; Riley and King 2013). We used cre-dependent Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) injections into the NST and ipsilateral LH or PBN and ipsilateral LH of Sst-cre mice to quantify single- and double-labeled CeA/Sst neurons. The HSV used is replication-deficient (e.g. does not result in trans-synaptic transport) and travels in the retrograde direction (e.g. from axon terminal to cell body) (Palmer et al. 2000; Neve et al. 2005; Epstein 2009; Fenno et al. 2014). Our results show that the CeA is composed of several distinct populations of Sst-expressing neurons that give rise to CeA/Sst-to-NST, CeA/Sst-to-PBN, and CeA/Sst-to-LH pathways. That these cell populations are distinct provides the opportunity for future investigations to delineate their contribution(s) to taste processing and ingestive behavior.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Transgenic mice homozygous for cre recombinase in somatostatin (Sst) expressing neurons (Sstm2.1(cre) Zjh/J) and wild-type mice (C57BL/J6) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Taniguchi et al. 2011). The two strains were bred at the University of Louisville to generate mice heterozygous for cre recombinase expression in Sst neurons. The mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled colony room on a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to normal rodent chow and distilled water unless otherwise noted. All procedures conformed to NIH guidelines and were approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 12 mice were used for this study, 6 for NST/LH injections (4 males, 2 females) and another 6 for PBN/LH injections (3 males, 3 females).

Surgery

The mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and Anased (10 mg/kg) mixture. If needed, an additional dose of ketamine (50 mg/kg) was administered to maintain a deep level of anesthesia, which was determined using toe pinch reflex. The scalp was shaved and disinfected using Prevantics Swab (Professional Disposables International). Mice were secured in a stereotaxic apparatus and ophthalmic ointment was applied to both eyes. Body temperature was maintained at 35 ± 1 °C by a feedback-controlled heating pad and rectal temperature probe. A midline incision was made to expose the skull, and the skull was leveled with reference to bregma and lambda cranial sutures. Two small holes were drilled through the bone to allow ipsilateral access to either NST and LH or PBN and LH. The analgesic Meloxicam (5 mg/kg) was administered prior to wound incision and again for at least 2 days post-surgery.

HSV injections

The coordinates used for viral injections into NST and PBN were, respectively, 6.1 mm posterior to bregma, 1.3 mm lateral to midline, 3.9 mm ventral to the surface of the cerebellum and 5.1 mm posterior to bregma, 1.3 mm lateral to midline, 3.6 mm ventral to the surface of the inferior colliculus (Bartonjo and Lundy 2020). The coordinates for LH injections were 1.3 mm posterior to bregma, 1.1 mm lateral to midline, and 4.7 mm ventral to the cortical surface. Viral injections were performed using a 10-μL nanofil syringe (34 g beveled needle, WPI) mounted in a microprocessor-controlled injector (UltraMicroPump, WPI) attached to the stereotaxic instrument. The syringe was first front-filled with light mineral oil followed by either HSV-EF1alpha-DIO-EYFP (RN415, 2.5 × 109 infectious units/mL) for NST or PBN injections and HSV-EF1alpha-DIO-mCherry (RN413, 2.5 × 109 infectious units/m) for LH injections [Dr. Rachael Neve, Massachusetts General Hospital (Neve et al. 2005)]. Because the mCherry and EYFP genes are preceded by DIO, a double-floxed inverse open reading frame, expression of transgene is restricted to Sst-expressing neurons (Taniguchi et al. 2011; Li et al. 2013; Fenno et al. 2014; Yu et al. 2016). Prior research indicates that injection of multiple HSV constructs do not negatively interact with one another and are capable of retrograde transport to identify double-labeled neurons that project to distinct target areas (Kim and Cho 2017; Lorsch et al. 2019; Bartonjo and Lundy 2020). The microprocessor was set to deliver 300 nL of the virus at a rate of 40 nL/min, and the syringe retracted 5 min post-injection. A different syringe was used for each virus. Once the viral injections were completed, the incision was sealed using Vetbond tissue glue and triple antibiotic ointment was applied to the skin around the incision. Animals were monitored for an additional 1 h on a heating pad and then returned to the home cage once ambulatory.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy

Three weeks post-surgery, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of a lethal dose of ketamine/anased mixture (300 mg/kg [ketamine]/30 mg/kg [anased]) followed by thoracotomy and transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Extracted brains were post-fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. Two brain blocks, one containing NST and PBN and another containing CeA and LH, were made. The blocks were cut (60 μm) using a vibrating microtome (Leica). Every other section was collected, blocked with 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) in 0.1% triton-X phosphate-buffered saline (TPBS) followed by incubation at 4 °C overnight on a shaker in 1:1000 dilution (in 0.1% TPBS and 5% NDS) of goat anti-GFP (Novus Biologicals) and rabbit anti-DsRed (Novus Biologicals) primary antibodies. After four rinses in TPBS (10 min each), the tissue sections were incubated (at room temperature) for 1 h in 1:100 dilution (in 0.1% TPBS and 5% NDS) of Alexa Fluor-488 donkey anti-goat and Alexa Fluor-546 donkey anti-rabbit (Fisher Scientific). After rinsing three times in phosphate-buffered saline and once in phosphate buffer (10 min each), the sections were mounted on microscope slides (HistoBond Adhesive Microscope Slides, VWR) and allowed to dry for 1 h. The sections were rehydrated with deionized water followed by Fluoromount-G mounting medium and coverslips.

Data analysis

Images of injection sites and retrograde-labeled cells positive for EYFP and mCherry were obtained using sequential scanning with an Olympus confocal microscope. In alternate tissue sections (10 per animal), the number of fluorescent positive cells in each Z stack (3 μm/slice) of the CeA and LH was calculated (Olympus FluoView software). The CeA was identified as the area approximately 0.7 to 1.8 mm posterior to bregma ventral to the striatum, medial to the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala, and lateral to the optic tract. The LH was identified as the area approximately 1.2 to 2.2 mm posterior to bregma ventral to the zona incerta, medial to the internal capsule/cerebral peduncle, and lateral to the fornix. The color segmentation function in ImageJ software was used to separate and count labeled neurons (Bartonjo and Lundy 2020). The separate color channels were converted to 8-bit images, auto-threshold adjusted (white objects on black background, otsu, or triangle method), and a Gaussian blur applied (sigma radius = 2). The appropriate scale was set (0.85 pixels/μm (10× magnification)) and the analyze particles function (size ≥ 20 μm2) was used to count labeled cells (CeA sections: green and red channels; LH sections: green channel only). For CeA, the image calculator function “AND” was used to identify overlapping pixels in the separate channels. Using the analyze particles function on the resultant image, overlapping elements with size ≥ 20 μm2 were considered double labeled. Manual counts on select sections were similar to automated calculations. Data measurements passed normality (Shapiro-Wilk) and equality of variance tests (Brown-Forsythe) and were statistically analyzed using independent t-tests (SigmaPlot 14.5). The results are presented as mean ± s.e. and P < 0.05 was considered as evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

The software package RStudio was used to calculate complementary estimates of effect size (Hedges’ g (g)) and corresponding confidence intervals (95% CI) (Lakens 2013; Yigit and Mendes 2018). Hedges’ g is considered less biased compared to Cohen’s d for smaller sample sizes and represents the difference of the means in units of the pooled standard deviation.

Results

NST-LH injections

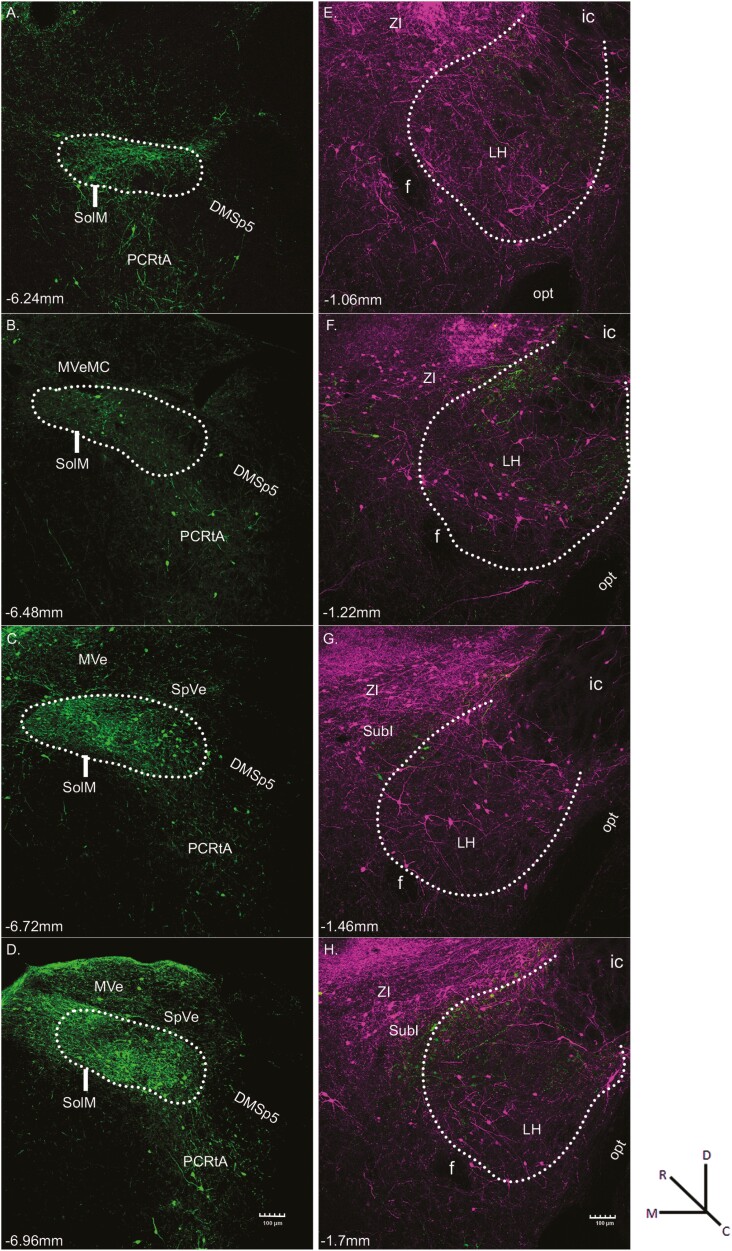

Microscopic examination of tissue from HSV-EYFP injections into the NST showed neurons and fibers expressing Sst (green fluorescence) throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the NST with minimal fluorescence in the ventrally located reticular formation or laterally located dorsomedial spinal trigeminal nucleus (Fig. 1A–D). The green cells in the NST likely reflect Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas indicate Sst neurons that project to the NST or possibly virus spread outside the NST taken up by Sst-expressing interneurons (Travers 1988; Beckman and Whitehead 1991; Balaban and Beryozkin 1994; Thek et al. 2019).

Fig. 1.

Representative fluorescent images resulting from the injection of HSV-Ef1α-DIO-EYFP into the NST (A-D, green) and HSV-Ef1α-DIO-mCherry into the LH (E-H, magenta) of an Sst-cre mouse. Sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). White dots outline the approximate boundaries of the NST and the LH. Within the NST, green fluorescence indicates Sst-expressing neurons that project locally within the NST. Within the LH, the magenta fluorescent cells indicate Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas such as ZI and SubI indicate Sst neurons that project to the LH. The green fluorescent cells represent Sst-positive LH-to-NST projection neurons, while the green fluorescent fibers likely represent retrograde-labeled axons from higher structures. The approximate level relative to bregma is shown at the bottom left of each photomicrograph (Paxinos and Franklin 2001). Magnification was 10× (0.85 pixels/μm). Abbreviations: DMsp5, dorsomedial spinal trigeminal nucleus; anterior part; f, fornix; ic, internal capsule; LH, lateral hypothalamus; MVe, medial vestibular nucleus; MVeMC, medial vestibular nucleus, magnocellular part; opt, optic tract; PCRtA, parvicellular reticular nucleus, alpha part; SolM, nucleus of the solitary tract, medial part; SpVe, spinal vestibular nucleus; SubI, substantia innominata; ZI, zona incerta.

Photomicrograph examples of HSV-mCherry injection into the LH of the same mouse are shown in Fig. 1E–H where neurons and fibers expressing Sst (magenta fluorescence) were located primarily within the LH and dorsally in the adjacent substantia innominata (SubI) and zona incerta (ZI). The magenta fluorescent cells in the LH likely reflect Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in SubI and ZI indicate Sst neurons that project to the LH or possibly virus spread outside the LH taken up by Sst-expressing interneurons (Grove 1988a; Grove 1988b; Li et al. 2021). The green cells represent Sst-positive LH-to-NST projection neurons, while green fibers likely represent retrograde-labeled axons from higher structures that pass through the LH.

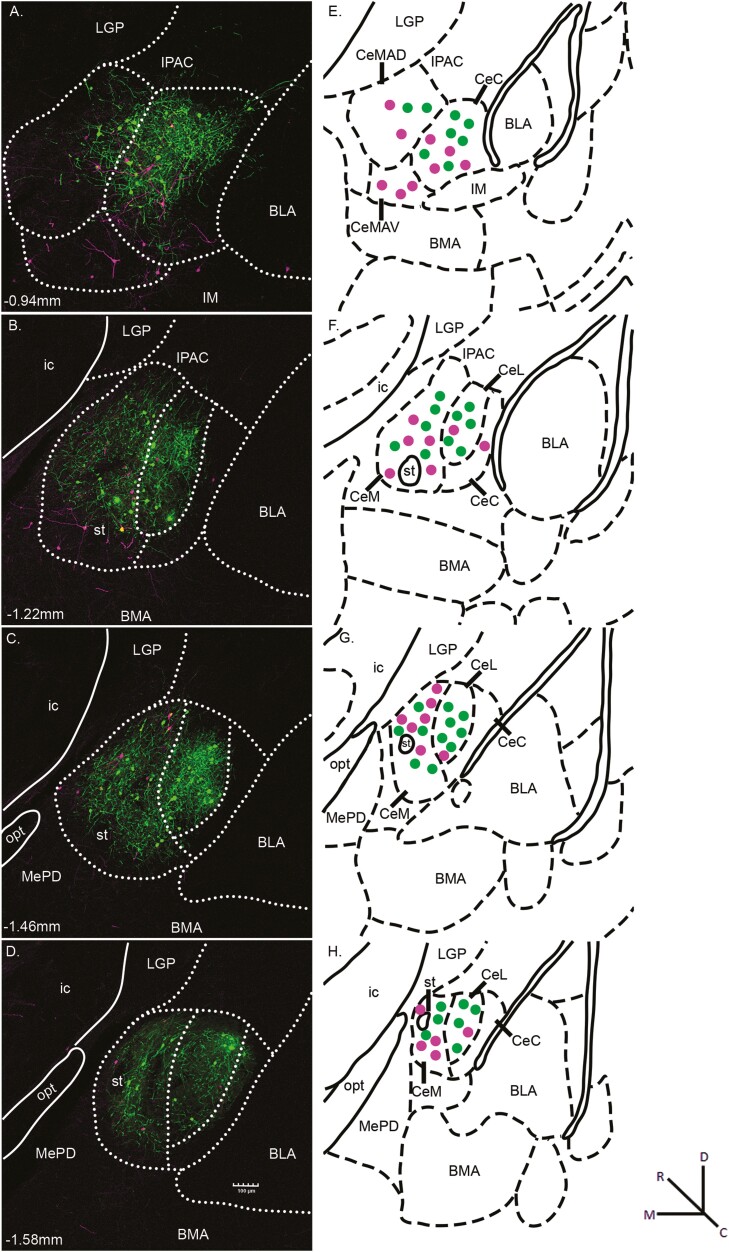

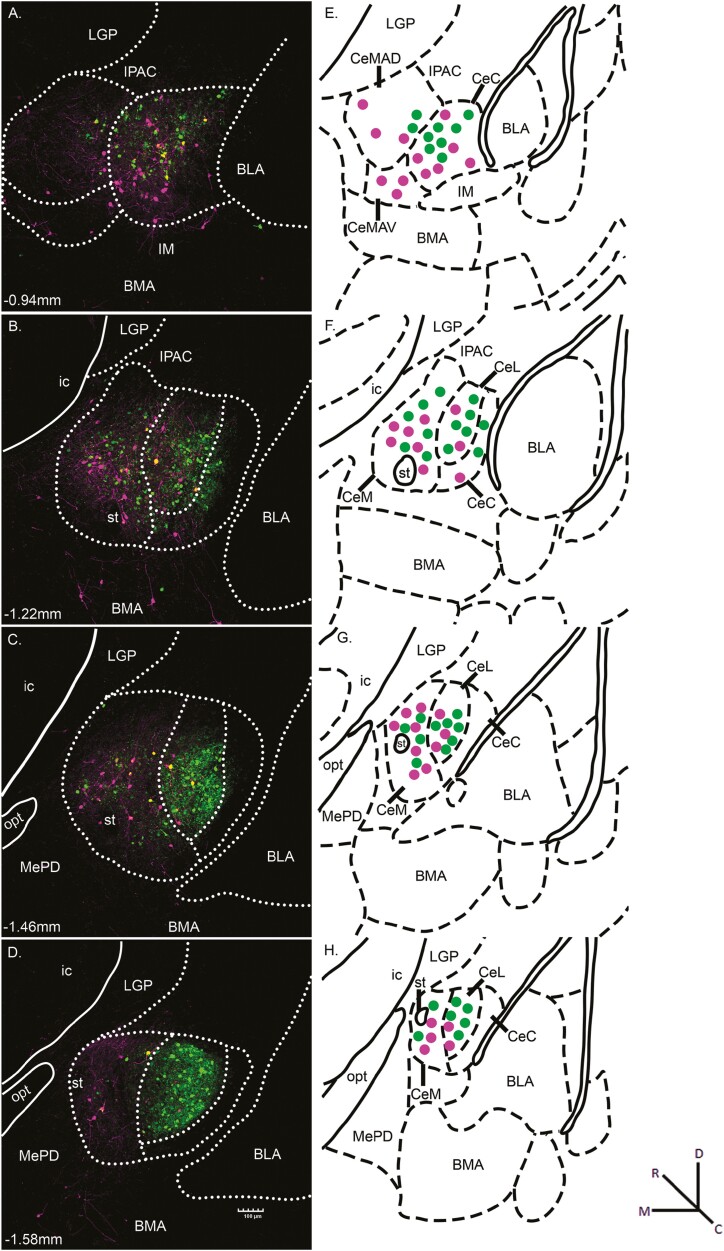

Expression of both fluorescent markers was observed throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the amygdala. Photomicrograph examples of retrograde-labeled Sst-expressing neurons at four different levels of the CeA are shown in Fig. 2A–D. Panels E–H show corresponding stereotaxic atlas drawings depicting the general location of CeA/Sst neurons projecting to the NST (green) and LH (magenta). In the schematic, no attempt was made to signify double-labeled neurons (yellow in Fig. 2A and B) or provide an exact representation of the total number of cells in each photomicrograph. In one animal, the HSV injection aimed at LH was misplaced medial to the fornix and resulted in retrograde labeled CeA/Sst neurons located in the medial nucleus of the amygdala rather than the central nucleus (not shown).

Fig. 2.

(A-D) Representative photomicrographs of CeA/Sst neurons projecting to the NST (green) and LH (magenta) from HSV injections depicted in Fig. 1. Yellow fluorescence indicates Sst neurons that project both to the NST and LH. The white dotted lines outline the approximate boundaries of the CeC, CeL, and CeM divisions of the CeA. The approximate levels relative to bregma are indicated at the bottom left corner of each photomicrograph. Magnification of fluorescent images was 10× (0.85 pixels/μm). (E-H) Corresponding diagrams labeled with amygdala subnuclei as defined in Paxinos and Franklin (2001). The general location of retrograde labeled neurons is represented by green (NST projecting) and magenta (LH projecting) dots. Abbreviations: BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; BMA, basomedial amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; CeC, central amygdaloid nucleus, capsular part; CeL, central amygdaloid nucleus, lateral division; CeM, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division; CeMAD, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division, anterodorsal part; CeMAV, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division, anteroventral part; IM, intercalated amygdaloid nucleus, main part; ic, internal capsule; IPAC, interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure; LGP, lateral globus pallidus; MePD, medial amygdaloid nucleus, posterodorsal part; opt, optic tract; st, stria terminalis.

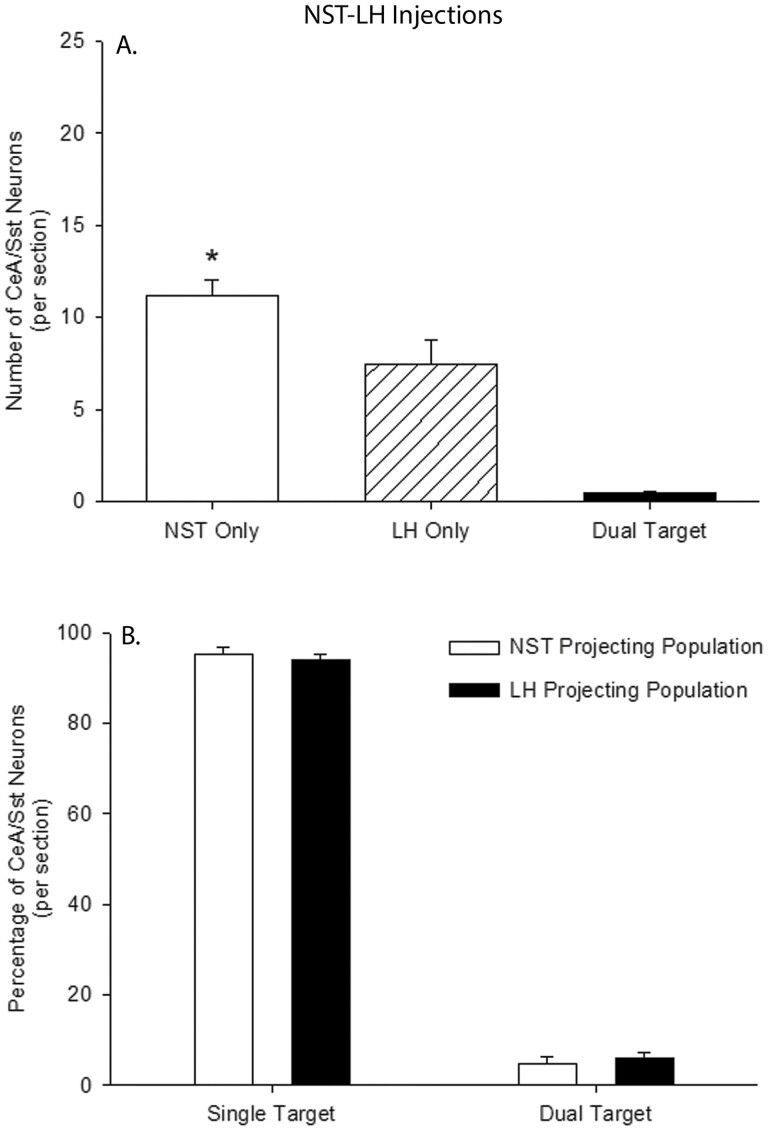

We counted a total of 658 CeA/Sst neurons that projected to the NST and 437 projecting to the LH. A greater number of retrograde-labeled CeA/Sst neurons was associated with the NST injections (11.1 ± 0.95 cells per section) compared to LH injections (7.4 ± 1.4 cells per section; Fig. 3A, t(10) = 2.36, P = 0.03, g = 1.26, 95% CI (0.13, 3.01)). Out of the 1,095 retrograde labeled neurons, only 27 contained both fluorescent markers and were considered dual-target neurons (Fig. 3A; 0.46 ± 0.12 cells per section). Expressed as a percentage of their respective population, greater than 90% of CeA/Sst cells project either to the NST or LH (Fig. 3B). Injection site was not associated with differences in the percentage of single-target (t(10) = 0.67, P = 0.52, g = 0.35, 95% CI (−0.86, 1.74)) or dual-target neurons (t(10) = −0.67, P = 0.52, g = −0.35, 95% CI (−1.74, 0.85)). For the LH, the mean number of LH/Sst-to-NST neurons was 5.73 ± 0.89 per section.

Fig. 3.

(A) The per section average of retrograde labeled Sst neurons in the CeA following HSV injections into the NST and LH of Sst-cre mice. Open bar represents the average number of Sst cells that are only projected to the NST, cross-hatched bar Sst cells that are only projected to the LH, and filled bar Sst cells that are projected both to the NST and LH. *, NST Only >LH Only. (B) The mean percentage of single- and double-labeled Sst neurons in the CeA following HSV injections into the NST (open bars) and LH (filled bars).

PBN-LH injections

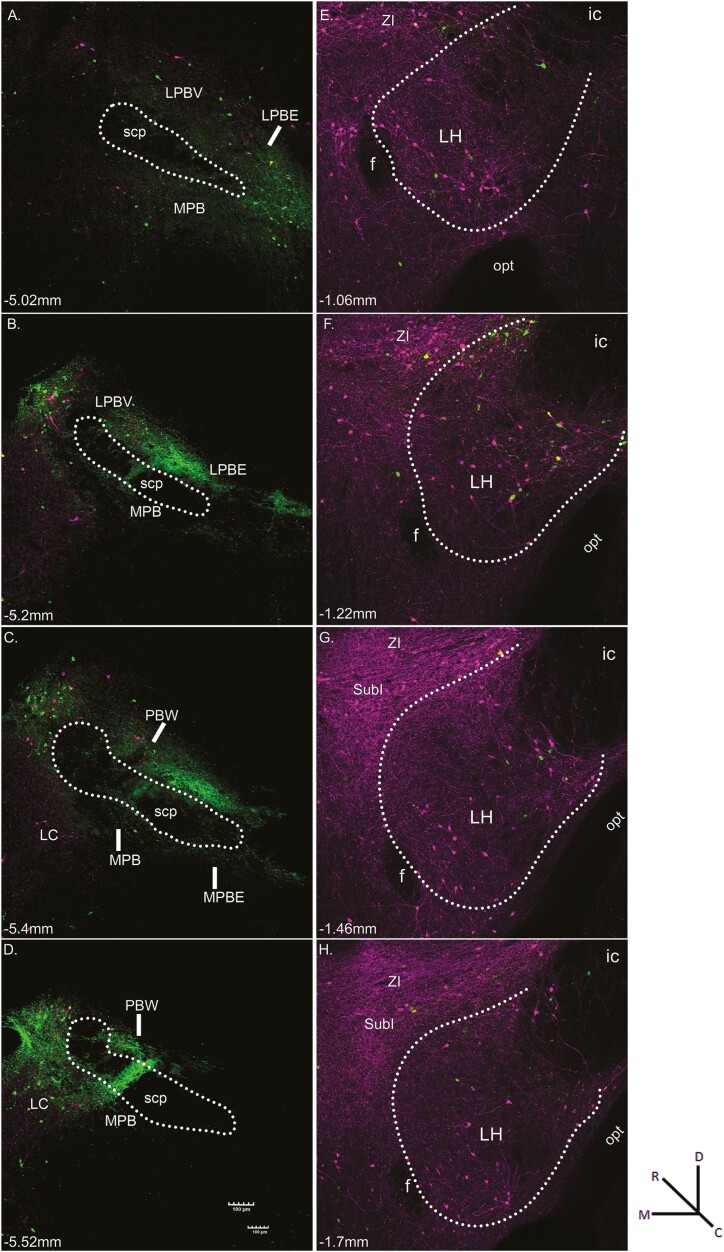

Microscopic examination of tissue from HSV-EYFP injections into the PBN showed neurons and fibers expressing Sst (green fluorescence) surrounding the superior cerebellar peduncle (scp) at each level (Fig. 4A–D). The green cells in the PBN likely reflect Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas such as LC indicate Sst neurons that project to the PBN or possibly virus spread outside the PBN taken up by Sst-expressing interneurons (Giehl and Mestres 1995; Luppi et al. 1995). The magenta fluorescent cells represent Sst positive PBN-to-LH projection neurons (Norgren 1976). Photomicrograph examples of HSV-mCherry injection into the LH of the same mouse are shown in Fig. 4E–H where, again, neurons and fibers expressing Sst (magenta fluorescence) were located primarily within the LH and dorsally in the adjacent SubI and ZI. The green cells represent Sst-positive LH-to-PBN projection neurons, while green fibers likely represent retrograde-labeled axons from higher structures that pass through the LH. Similar to NST/LH injected mice, PBN/LH viral injections resulted in dense expression of fluorescent markers throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the amygdala. Photomicrograph examples of retrograde-labeled Sst-expressing neurons in CeA are shown in Fig. 5A–D with corresponding stereotaxic atlas drawings in panels E–H.

Fig. 4.

Representative fluorescent images resulting from the injection of HSV-Ef1α-DIO-EYFP into the PBN (A-D, green) and HSV-Ef1α-DIO-mCherry into the LH (E-H, magenta) of an Sst-cre mouse. Sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). White dots outline the approximate boundaries of the LH and superior cerebellar peduncle (scp) in the PBN. Within the PBN, the green fluorescent cells indicate Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas such as LC indicate Sst neurons that project to the PBN. The magenta fluorescent cells represent Sst-positive PBN-to-LH projection neurons. Within the LH, the magenta fluorescent cells indicate Sst-expressing interneurons, while those in surrounding areas such as ZI and SubI indicate Sst neurons that project to the LH. The green fluorescent cells represent Sst-positive LH-to-PBN projection neurons, while the green fluorescent fibers likely represent retrograde-labeled axons from higher structures. The approximate level relative to bregma is shown at the bottom left of each photomicrograph. Magnification was 10 × (0.85 pixels/micron). Abbreviations: f, fornix; ic, internal capsule; LC, locus coeruleus; LH, lateral hypothalamus; LPBE, lateral parabrachial nucleus, external part; LPBV, lateral parabrachial nucleus, ventral part; MPB, medial parabrachial nucleus; MPBe, medial parabrachial nucleus, external part; opt, optic tract; PBW, parabrachial nucleus, waist part; scp; superior cerebellar peduncle; SubI, substantia innominata; ZI, zona incerta.

Fig. 5.

(A-D) Representative photomicrographs of CeA/Sst neurons projecting to the PBN (green) and LH (magenta) from HSV injections depicted in Fig. 4. Yellow fluorescence indicates Sst neurons that project both to the PBN and LH. The white dotted lines outline the approximate boundaries of the CeC, CeL, and CeM divisions of the CeA. The approximate levels relative to bregma are indicated at the bottom left corner of each photomicrograph. Magnification of fluorescent images was 10 × (0.85 pixels/μm). (E-H) Corresponding diagrams labeled with amygdala subnuclei as defined in Paxinos and Franklin (2001). The general location of retrograde labeled neurons is represented by green (PBN projecting) and magenta (LH projecting) dots. Abbreviations: BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; BMA, basomedial amygdaloid nucleus, anterior part; CeC, central amygdaloid nucleus, capsular part; CeL, central amygdaloid nucleus, lateral division; CeM, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division; CeMAD, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division, anterodorsal part; CeMAV, central amygdaloid nucleus, medial division, anteroventral part; IM, intercalated amygdaloid nucleus, main part; ic, internal capsule; IPAC, interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure; LGP, lateral globus pallidus; MePD, medial amygdaloid nucleus, posterodorsal part; opt, optic tract; st, stria terminalis.

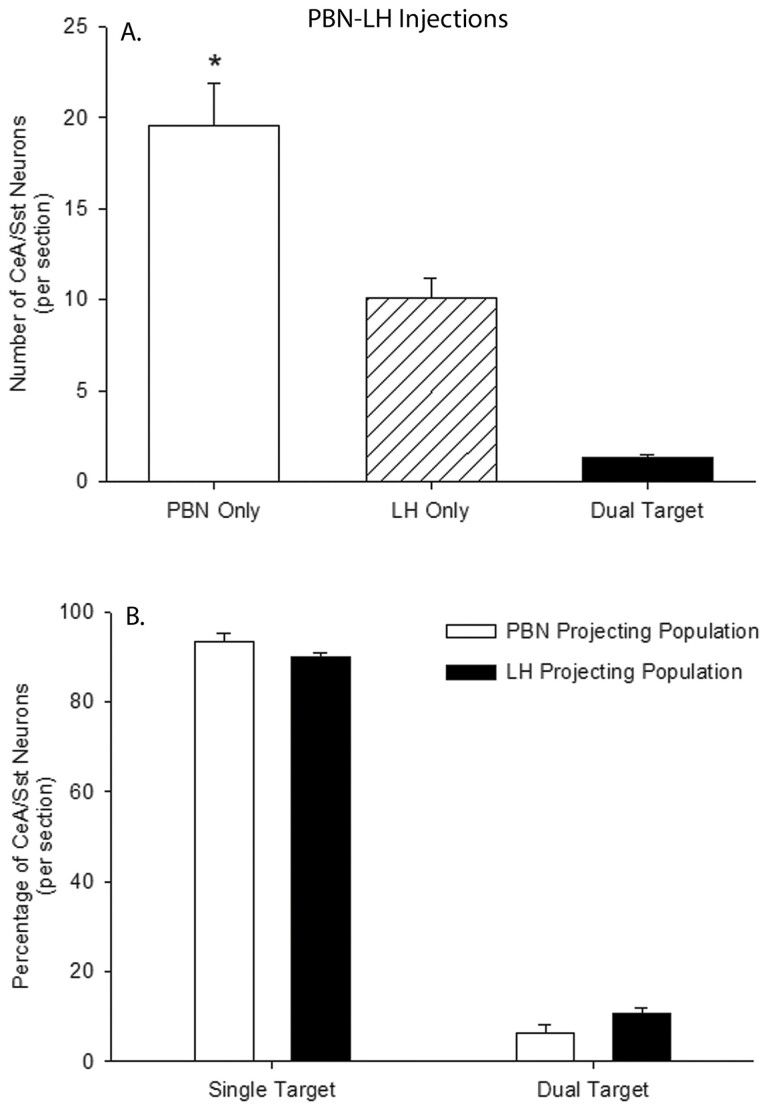

A total of 1,176 CeA/Sst neurons that projected to the PBN and 607 that projected to the LH were counted. A larger population of CeA/Sst neurons was associated with PBN injections (19.6 ± 2.5 cells per section) compared to LH injections (10.1 ± 1.2 cells per section; Fig. 6A, t(10) = 3.7, P = 0.004, g = 1.97, 95% CI (0.81, 4.10)). Out of the 1,783 retrograde-labeled neurons, only 78 contained both fluorescent markers and were considered dual-target neurons (Fig. 6A; 1.3 ± 0.2 cells per section). Expressed as a percentage of their respective population, 90% or more of CeA/Sst cells project either to the PBN or LH (Fig. 6B). Injection site was not associated with differences in the percentage of single-target (t(10) = 1.74, P = 0.11, g = 0.93, 95% CI (−0.21, 2.54)) or dual-target neurons (t(10) = −1.97, P = 0.07, g = −1.05, 95% CI (−2.71, 0.09)). Similar to NST injections, PBN injections resulted in retrograde labeled Sst neurons in the LH (3.83 ± 0.82 cells per section).

Fig. 6.

(A) The per section average of retrograde labeled Sst neurons in the CeA following HSV injections into the PBN and LH of Sst-cre mice. Open bar represents the average number of Sst cells that are only projected to the PBN, cross-hatched bar Sst cells that are only projected to the LH, and filled bar Sst cells that are projected both to the PBN and LH. *, PBN Only > LH Only. (B) The mean percentage of single- and double-labeled Sst neurons in the CeA following HSV injections into the PBN (open bars) and LH (filled bars).

Additional analyses comparing NST/LH and PBN/LH injected mice (compare Figs. 3A and 6A) revealed that the injection pair was not associated with differences in the number of single-labeled CeA/Sst-to-LH projecting neurons (t(10) = −1.56, P = 0.15, g = −0.83, 95% CI (−2.40, 0.31)). In contrast, PBN injections were associated with a greater number of single-labeled CeA/Sst neurons compared to NST injections (t(10) = −3.39, P = 0.006, g = −1.81, 95% CI (−3.85, −0.66)). Finally, PBN/LH injections were associated with a greater number of dual-labeled CeA/Sst neurons compared to NST/LH injections (t(10) = −3.64, P = 0.004, g = −1.94, 95% CI (−4.04, −0.77)). Albeit the number of dual-target neurons was minimal for both injection groups. Together, the present results show that CeA neurons marked by Sst expression can be delineated into subpopulations that project to either the NST, PBN, or LH.

Discussion

The objective of the present experiments was to further elaborate on the heterogeneity of a large subpopulation of CeA neurons that express the neuropeptide Sst. The present findings mirror results from previous studies showing that the medullary reticular formation, NST, and PBN are largely innervated by distinct populations of CeA neurons (Kang and Lundy 2009b; Zhang et al. 2011) and, at least for the NST and PBN, a subpopulation of these neurons express Sst (Bartonjo and Lundy 2020). The present results extend these observations by demonstrating that an additional subset of CeA/Sst neurons project to the LH and are largely distinct from CeA/Sst-to-NST and CeA/Sst-to-PBN projecting neurons.

To the best of our knowledge, only three prior studies have assessed the role of CeA/Sst neurons on ingestive behavior. In two of these studies, CeA/Sst neurons as a whole were targeted for optogenetic manipulation that resulted in either increased or decreased intake of water (Yu et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2017). The third study used retrograde transported HSV to specifically target CeA/Sst-to-NST neurons for optogenetic manipulation (Bartonjo et al. 2022). During brief-access licking sessions, the intake of water and sucrose was unaffected by altering the neural activity of the CeA/Sst-to-NST pathway, while intake of QHCl was increased by inhibiting this pathway. These inconsistencies regarding water intake are not easily explained but are likely due to procedural differences among studies as well as the fact that the latter experiment from our laboratory targeted a defined projection of CeA/Sst neurons rather than simply targeting the whole population.

Beyond manipulating the neural activity of cell-type/target-specific neurons, the interconnectivity of brain regions also must be considered. Specifically, the LH and the CeA are reciprocally connected to each other, and the LH also innervates the NST to modulate processing of taste information (Ottersen 1980; Ono et al. 1985; Cho et al. 2002; Kang and Lundy 2010; Reppucci and Petrovich 2016; Barbier et al. 2018). Given this interconnectivity, there was uncertainty that the observed increase in acceptance of QHCl described above resulted solely from inhibiting CeA/Sst neurons with direct projections to the NST. The present anatomical study sheds light on this interpretational caveat by showing that CeA/Sst-to-NST neurons are distinct from CeA/Sst neurons projecting to the LH. Thus, altered responding to QHCl was likely the result of specific manipulation of CeA/Sst-to-NST neurons rather than indirect modulation of CeA/Sst-to-LH neurons that, in turn, project to the NST. It is possible, however, that independent perturbation of CeA/Sst-to-LH as well as CeA/Sst-to-PBN pathways might also influence QHCl and/or sucrose sensitivity.

In summary, the CeA comprises a wide array of molecularly distinct cell populations and contributes to the control of a wide range of behaviors (Tye et al. 2011; Li et al. 2013; Yu et al. 2016; Douglass et al. 2017; McCullough et al. 2018). Despite this molecular diversity, a particular cell type can have a divergent function such as the contribution of CeA/Sst neurons to expression of conditioned fear and ingestive behavior. In light of previous research and the current study, this likely relies on engagement of target-specific subpopulation(s) of CeA/Sst neurons. At least for the NST, CeA/Sst neurons have been shown to innervate both the rostral and caudal divisions (Saha et al. 2002; Bartonjo and Lundy 2020) and, thus, likely function to modulate both oral and visceral sensory information, respectively. In the future, it will be necessary to identify additional cell-type/target-specific pathways to provide a more thorough understanding of the molecular basis of amygdala function (Douglass et al. 2017; Torruella-Suarez et al. 2020; Bartonjo et al. 2022).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rachael Neve, co-director of the Gene Delivery Technology Core at Massachusetts General Hospital, for the Herpes Simplex Virus.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21DC015759. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article.

References

- Balaban CD, Beryozkin G.. Vestibular nucleus projections to nucleus tractus solitarius and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve: potential substrates for vestibulo-autonomic interactions. Exp Brain Res. 1994;98:200–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier M, Fellmann D, Risold PY.. Morphofunctional organization of the connections from the medial and intermediate parts of the central nucleus of the amygdala into distinct divisions of the lateral hypothalamic area in the rat. Front Neurol. 2018;9:688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartonjo J, Masterson S, St. John SJ, Lundy R.. Perturbation of amygdala/somatostatin-nucleus of the solitary tract projections reduces sensitivity to quinine in a brief-access test. Brain Res. 2022;1783:147838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartonjo JJ, Lundy RF.. Distinct populations of amygdala somatostatin-expressing neurons project to the nucleus of the solitary tract and parabrachial nucleus. Chem Senses. 2020;45:687–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman ME, Whitehead MC.. Intramedullary connections of the rostral nucleus of the solitary tract in the hamster. Brain Res. 1991;557:265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broberger C, De Lecea L, Sutcliffe JG, Hokfelt T.. Hypocretin/orexin- and melanin-concentrating hormone-expressing cells form distinct populations in the rodent lateral hypothalamus: relationship to the neuropeptide Y and agouti gene-related protein systems. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:460–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YK, Li CS, Smith DV.. Taste responses of neurons of the hamster solitary nucleus are enhanced by lateral hypothalamic stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1981–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YK, Li CS, Smith DV.. Descending influences from the lateral hypothalamus and amygdala converge onto medullary taste neurons. Chem Senses. 2003;28:155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson J, Aldridge A, Wilmoth K, Erisir A.. A survey of oral cavity afferents to the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:495–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AM, Kucukdereli H, Ponserre M, Markovic M, Grundemann J, Strobel C, Alcala Morales PL, Conzelmann KK, Luthi A, Klein R.. Central amygdala circuits modulate food consumption through a positive-valence mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1384–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AL. HSV-1-derived amplicon vectors: recent technological improvements and remaining difficulties--a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenno LE, Mattis J, Ramakrishnan C, Hyun M, Lee SY, He M, Tucciarone J, Selimbeyoglu A, Berndt A, Grosenick L, et al. Targeting cells with single vectors using multiple-feature Boolean logic. Nat Methods. 2014;11:763–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferssiwi A, Cardo B, Velley L.. Gustatory preference-aversion thresholds are increased by ibotenic acid lesion of the lateral hypothalamus in the rat. Brain Res. 1987;437:142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giehl K, Mestres P.. Somatostatin-mRNA expression in brainstem projections into the medial preoptic nucleus. Exp Brain Res. 1995;103:344–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove EA. Neural associations of the substantia innominata in the rat: afferent connections. J Comp Neurol. 1988a;277:315–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove EA. Efferent connections of the substantia innominata in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1988b;277:347–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RB, Norgren R.. Central projections of gustatory nerves in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;222:560–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Lundy RF.. Terminal field specificity of forebrain efferent axons to brainstem gustatory nuclei. Brain Res. 2009a;1248:76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Lundy RF.. Terminal field specificity of forebrain efferent axons to brainstem gustatory nuclei. Brain Res. 2009b;1248:76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Lundy RF.. Amygdalofugal influence on processing of taste information in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:726–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Zhang X, Muralidhar S, LeBlanc SA, Tonegawa S.. Basolateral to central amygdala neural circuits for appetitive behaviors. Neuron 2017;93:1464–1479.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WB, Cho JH.. Synaptic targeting of double-projecting ventral CA1 hippocampal neurons to the medial prefrontal cortex and basal amygdala. J Neurosci. 2017;37:4868–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Penzo MA, Taniguchi H, Koper CD, Huang ZJ, Li B.. Experience-dependent modification of a central amygdala fear circuit. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:332–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CS, Cho YK.. Efferent projection from the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis suppresses activity of taste-responsive neurons in the hamster parabrachial nuclei. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R914–R926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Rizzi G, Tan KR.. Zona incerta subpopulations differentially encode and modulate anxiety. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabf6709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorsch ZS, Hamilton PJ, Ramakrishnan A, Parise EM, Salery M, Wright WJ, Lepack AE, Mews P, Issler O, McKenzie A, et al. Stress resilience is promoted by a Zfp189-driven transcriptional network in prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:1413–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy RF. Jr., Norgren R.. Activity in the hypothalamus, amygdala, and cortex generates bilateral and convergent modulation of pontine gustatory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004; 91:1143–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppi PH, Aston-Jones G, Akaoka H, Chouvet G, Jouvet M.. Afferent projections to the rat locus coeruleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing with cholera-toxin B subunit and Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. Neuroscience 1995;65:119–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magableh A, Lundy R.. Somatostatin and corticotrophin releasing hormone cell types are a major source of descending input from the forebrain to the parabrachial nucleus in mice. Chem Senses. 2014;39:673–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough KM, Morrison FG, Hartmann J, CarlezonWA, Jr, Ressler KJ.. Quantified coexpression analysis of central amygdala subpopulations. eNeuro 2018;5:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Herbert H, Hurley KM, Yasui Y, Gray TS, Saper CB.. Organization of cortical, basal forebrain, and hypothalamic afferents to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990a;295:624–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Gray TS.. Evidence for corticotropin-releasing factor, neurotensin, and somatostatin in the neural pathway from the central nucleus of the amygdala to the parabrachial nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1985;241:275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Saper CB, Gray TS.. Neuropeptide organization of the hypothalamic projection to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990b;295:662–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve RL, Neve KA, Nestler EJ, CarlezonWA, Jr.. Use of herpes virus amplicon vectors to study brain disorders. Biotechniques 2005;39:381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R. Taste pathways to hypothalamus and amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1976;166:17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R, Leonard CM.. Taste pathways in rat brainstem. Science 1971;173:1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T, Luiten PG, Nishijo H, Fukuda M, Nishino H.. Topographic organization of projections from the amygdala to the hypothalamus of the rat. Neurosci Res. 1985;2:221–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottersen OP. Afferent connections to the amygdaloid complex of the rat and cat: II. Afferents from the hypothalamus and the basal telencephalon. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:267–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JA, Branston RH, Lilley CE, Robinson MJ, Groutsi F, Smith J, Latchman DS, Coffin RS.. Development and optimization of herpes simplex virus vectors for multiple long-term gene delivery to the peripheral nervous system. J Virol. 2000;74:5604–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panguluri S, Saggu S, Lundy R.. Comparison of somatostatin and corticotrophin-releasing hormone immunoreactivity in forebrain neurons projecting to taste-responsive and non-responsive regions of the parabrachial nucleus in rat. Brain Res. 2009;1298:57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ.. 2001. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reppucci CJ, Petrovich GD.. Organization of connections between the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and lateral hypothalamus: a single and double retrograde tracing study in rats. Brain Structure Function 2016;221:2937–2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley CA, King MS.. Differential effects of electrical stimulation of the central amygdala and lateral hypothalamus on fos-immunoreactive neurons in the gustatory brainstem and taste reactivity behaviors in conscious rats. Chem Senses. 2013;38:705–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Henderson Z, Batten TF.. Somatostatin immunoreactivity in axon terminals in rat nucleus tractus solitarii arising from central nucleus of amygdala: coexistence with GABA and postsynaptic expression of sst2A receptor. J Chem Neuroanat. 2002;24:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richarson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 1998;92:573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, Kvitsiani D, Fu Y, Lu J, Lin Y, et al. A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron 2011;71:995–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thek KR, Ong SJM, Carter DC, Bassi JK, Allen AM, McDougall SJ.. Extensive inhibitory gating of viscerosensory signals by a sparse network of somatostatin neurons. J Neurosci. 2019;39:8038–8050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torruella-Suarez ML, Vandenberg JR, Cogan ES, Tipton GJ, Teklezghi A, Dange K, Patel GK, McHenry JA, Hardaway JA, Kantak PA, et al. Manipulations of central amygdala neurotensin neurons alter the consumption of ethanol and sweet fluids in mice. J Neurosci. 2020;40:632–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB. Efferent projections from the anterior nucleus of the solitary tract of the hamster. Brain Res. 1988;457:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye KM, Prakash R, Kim SY, Fenno LE, Grosenick L, Zarabi H, Thompson KR, Gradinaru V, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K.. Amygdala circuitry mediating reversible and bidirectional control of anxiety. Nature. 2011;471:358–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yigit S, Mendes M.. which effect size measure is appropriate for one-way and two-way ANOVA models? A Monte Carlo simulation study. Revstat Statist J. 2018;16:295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Garcia da Silva P, Albeanu DF, Li B.. Central Amygdala somatostatin neurons gate passive and active defensive behaviors. J Neurosci. 2016;36:6488–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Kang Y, Lundy RF.. Terminal field specificity of forebrain efferent axons to the pontine parabrachial nucleus and medullary reticular formation. Brain Res. 2011;1368:108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article.