Abstract

Background

Survivors of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) are at increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), in the form of recurrent stroke and myocardial Infarction. We investigated whether long‐term blood pressure (BP) variability represents a risk factor for MACCE after ICH, independent of average BP.

Methods and Results

We analyzed data from prospective ICH cohort studies at Massachusetts General Hospital and the University of Hong Kong. We captured long‐term (ie, visit‐to‐visit) BP variability, quantified as individual participants’ variation coefficient. We explored determinants of systolic and diastolic BP variability and generated survival analyses models to explore their association with MACCE. Among 1828 survivors of ICH followed for a median of 46.2 months we identified 166 with recurrent ICH, 68 with ischemic strokes, and 69 with myocardial infarction. Black (coefficient +3.8, SE 1.3) and Asian (coefficient +2.2, SE 0.4) participants displayed higher BP variability. Long‐term systolic BP variability was independently associated with recurrent ICH (subhazard ratio [SHR], 1.82; 95% CI, 1.19–2.79), ischemic stroke (SHR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.06–2.47), and myocardial infarction (SHR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.05–2.24). Average BP during follow‐up did not modify the association between long‐term systolic BP variability and MACCE.

Conclusions

Long‐term BP variability is a potent risk factor for recurrent hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction after ICH, even among survivors with well‐controlled hypertension. Our findings support the hypothesis that combined control of average BP and its variability after ICH is required to minimize incidence of MACCE.

Keywords: hypertension, intracranial hemorrhage, secondary prevention

Subject Categories: Hypertension, Intracranial Hemorrhage, Secondary Prevention

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HKU

Hong Kong University

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- MACCE

major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Survivors of intracerebral hemorrhage displaying higher long‐term blood pressure variability were at higher risk for recurrent hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction

Even survivors with well‐controlled hypertension were at higher risk for stroke and myocardial infarction when displaying higher long‐term blood pressure variability

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Optimal prevention of recurrent stroke and myocardial infarction among survivors of intracerebral hemorrhage likely requires both lowering average blood pressure and controlling its long‐term variability.

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is the most severe form of stroke, accounting for almost half of all stroke‐related morbidity and mortality. 1 Primary ICH represents an acute manifestation of underlying cerebral small vessel disease, a progressive degenerative condition of small caliber arterial and venous cerebral vessels and a leading cause of both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke worldwide. 2 Because of underlying cerebral small vessel disease over one third of all survivors of ICH will suffer from recurrent stroke (either ischemic or hemorrhagic) in the 10‐year period following the acute hemorrhage. 3 Recent studies also highlighted that survivors of ICH are at higher risk for myocardial Infarction (MI). 4 Taken together, recurrent vascular events represent major contributors to functional decline, decreased quality of life, diminished productivity, and prolonged disability after ICH. 5

Elevated blood pressure (BP) has been associated with cerebral small vessel disease severity and represents an established modifiable risk factor for recurrent stroke after ICH. 3 , 6 , 7 Recent studies indicate that increased BP variability could also play a crucial role in hypertensive end‐organ damage (independently of mean BP measurements), therefore affecting risk of stroke, coronary heart disease, end‐stage renal disease, and all‐cause mortality. 8 , 9 A recent post hoc analysis of the PRASTRO‐I trial (Comparison of Prasugrel and Clopidogrel in Japanese Patients With Ischemic Stroke‐I) demonstrated that higher visit‐to‐visit BP variability is associated with increased recurrent stroke risk after noncardioembolic infarcts. 10 However, crucial evidence regarding the association between BP variability and vascular events after ICH is currently lacking.

We therefore sought to determine whether survivors of ICH with increased long‐term BP variability are at higher risk for MACCE, that is, recurrent hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, and MI. We specifically sought to investigate whether the association between BP variability and MACCE after ICH is affected by underlying hypertension severity (ie, average BP). To address these questions, we leveraged longitudinal data from 2 ongoing, single‐center prospective studies of ICH with standardized capture of vascular events and visit‐to‐visit BP variability during follow‐up.

Methods

Data Availability

The authors certify they have documented all data, methods, and materials used to conduct the research presented. Anonymized data pertaining to the research presented will be made available upon reasonable request from external investigators.

Participating Studies and Enrollment Eligibility Criteria

Participants were individuals aged 18 years or older admitted at participating institutions with a new diagnosis of acute, primary ICH. For the purpose of the present study we included consecutive ICH cases presenting to either (1) Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) between January 2006 and December 2017 6 , 11 ; or (2) Hong Kong University (HKU) from January 2011 to March 2019. 12 Eligible individuals were initially identified via daily manual review of medical records, and ICH diagnosis was subsequently confirmed by brain computed tomography (CT) scan obtained within 24 hours of symptoms’ onset. Individuals with ICH secondary to trauma, conversion of an ischemic infarct, rupture of a vascular malformation or aneurysm, and brain tumor were excluded. Because we focused on recurrent major vascular events as outcomes of interest, only individuals alive at time of discharge from the acute ICH hospitalization were included in subsequent analyses. Study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Baseline Data Collection

Trained study staff collected demographic, social, and medical history in both studies via in‐person interview of patients (and/or reliable informants) and review of electronic medical records at time of enrollment. Participants and/or informants provided self‐identified race and ethnicity, choosing from categories recommended by the National Institutes of Health for use in research studies. 11 All available CT scans were deidentified, digitalized, and uploaded to the central neuroimaging repository at both sites. Admission (ie, first available) CT scans were analyzed to determine ICH location, hematoma volume, and presence of intraventricular blood according to a previously validated methodology. 6 All neuroimaging was analyzed blinded to clinical information.

Longitudinal Follow‐Up

For the MGH‐ICH study, survivors of ICH and their caregivers were interviewed by dedicated study staff (blinded to baseline and neuroimaging information) at 3, 6, and 12 months after index ICH and every 6 months thereafter, based on established protocols. 6 Participants from the HKU‐ICH study were followed up by clinicians 3, 6, and 12 months after index ICH and every 6 months thereafter. 12 In both studies we supplemented patient‐based collection of follow‐up data with semiautomated review of longitudinal electronic health records to confirm and augment participant‐reported information. We specifically collected information on antihypertensive medication use during follow‐up. In both studies if participants or caregivers reported new neurologic symptoms, recurrent stroke, MI, hospital admission, or death, pertinent medical records and radiology reports were reviewed by study staff to minimize loss to follow‐up. 6 Adjudication of recurrent ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke events required direct review of neuroimaging scans.

Capture of Blood Pressure and Antihypertensive Medication Data

MGH‐ICH and HKU‐ICH research staff collected information on BP measurements obtained in an outpatient medical setting by medical personnel (self‐reported or home measurements were not taken into consideration) according to previously published methods. 6 , 11 , 13 Eligible outpatient encounters for BP capture included both prespecified follow‐ups (at 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and thereafter every 6 months from ICH in both studies), as well as additional outpatient clinical encounters initiated by patients or prompted by clinical needs (both related to stroke care and to other noncerebrovascular medical problems). For all encounters BPs were measured using an automated BP machine with the patient in a sitting position, after a 5‐minute rest. For all measurements 2 BP readings were obtained, and the average BP was recorded. For both studies we specifically excluded BP measurements obtained in inpatient settings (including emergency departments) to avoid capturing short‐term BP variability attributable to acute medical events. At‐home BP measurements (whether from a visiting medical professional or self‐monitoring) were also not considered for the purpose of our analyses. Only measurements including value for both systolic and diastolic BP were considered eligible for analysis. All patients with 1 or more missing BP measurements or medication use data at any time point during follow‐up were excluded.

Definition of Variables

Age at index ICH was analyzed as a continuous variable. Race or ethnicity was analyzed as a set of dichotomous variables. Measurements of systolic and diastolic BP were calibrated on 10 mm Hg increases and entered in survival models (discussed later) as time‐varying variables, as previously described. 6 , 11 Systolic and diastolic BP long‐term variability were quantified by computing variation coefficients (ie, ratios of SD during follow‐up over the mean value) for each variable, which were then subdivided into quintiles for analyses purposes. 11 The number of antihypertensive agents prescribed during follow‐up was analyzed as an ordinal variable with levels corresponding to concomitant use of none, 1, 2, or 3 or more agents. Outcomes of interest were MACCE, specifically including recurrent ICH, incident ischemic stroke, incident MI, and vascular death (defined as mortality attributed to recurrent ICH, ischemic stroke, or MI). 14 Recurrent ICH was defined as the first episode during follow‐up of new‐onset of neurological symptoms attributable to an intraparenchymal hemorrhage distinct from the initial event, as confirmed by CT imaging. Incident ischemic stroke was defined as the first episode during follow‐up of new‐onset of neurological symptoms attributable to a cerebral infarct, as confirmed by CT or magnetic resonance imaging. Incident MI was defined as the first episode during follow‐up of new‐onset of clinical symptoms consistent with acute myocardial ischemia and/or infarct due to abrupt reduction in coronary blood flow, as demonstrated by both elevated cardiac biomarkers and ECG changes in the appropriate clinical context.

Statistical Analysis

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of Long‐Term BP Variability

Continuous variables were expressed as either mean with SD or median with interquartile range. Categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages of subtotal. Categorical variables were compared using chi‐square or Fisher exact tests (2 tailed) and continuous variables using the Mann‐Whitney U rank‐sum or Student t test, as appropriate. We used linear regression models to identify factors associated with systolic and diastolic BP. For both models we initially included all factors associated with BP variability in univariable analyses at significance level of P<0.20. We subsequently used backward elimination procedures to arrive at a minimal model including only variables associated at P<0.05. We prespecified adjustment for patient age, sex, self‐reported race or ethnicity, participating study (dichotomous variable indicating MGH versus HKU data source), year of index ICH (in 2‐year increments), and number of available BP measurements.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses of Recurrent Acute Vascular Events

We determined factors associated with recurrent vascular events in univariable analyses using Kaplan‐Meier plots, with significance testing via the log‐rank test. Patient data were censored only in case of death or loss to follow‐up. We performed multivariable analyses of survival outcomes using competing risk regression models via the Fine and Gray method, to account for competing risks between recurrent vascular events and death. 15 We created separate multivariable models for all MACCE, recurrent ICH, incident ischemic stroke, and incident MI. For all multivariable models we initially included all factors associated with outcomes of interest in univariable analyses at significance level of P<0.20. Systolic and diastolic BP measurements and their variation coefficients were modeled as time‐varying variables, in agreement with previously published methodology. 6 Briefly, for each study time period (ie, 3 to 6 months, 6 to 12 months, and every 6‐month interval thereafter) we first calculated mean systolic and diastolic BP variables using all available measurements. These were then included in our multivariable models as time‐varying variables. For each participants and within each study period we then calculated the variation coefficient for both systolic and diastolic BP, after ensuring we had at least 3 separate measurements available (to guarantee the stability of our long‐term variability estimates). These were then also included in our multivariable models as time‐varying variables. We subsequently used backward elimination procedures to arrive at a minimal model including only variables associated at P<0.05. We prespecified adjustment for patient age, sex, self‐reported race or ethnicity, participating study (dichotomous variable indicating MGH versus HKU data source), year of index ICH (in 2‐year increments), and number of available BP measurements. Of note, all survival analyses were first conducted separately in the MGH‐ICH and HKU‐ICH and then in a combined data set with adjustment for data source (as described previously). We conducted tests of heterogeneity for all associations tested, but found no evidence of differential effects based on data source (all heterogeneity P values >0.20). The proportional hazard assumption was tested for all survival analyses using graphical checks and Schoenfeld residuals‐based tests.

Additional Analyses

We prespecified several additional analyses. First, we explored additional metrics of long‐term BP variability for association with MACCE, including (1) SD, another commonly reported metric of variability; (2) BP range, that is, difference between maximum and minimum values in each follow‐up period; and (3) average real variability, which better captures long‐term variations in BP over time. Second, we sought to determine whether the association between BP variability was affected by hypertension severity (ie, average BP) during follow‐up. To do so, we created multivariable models for association between BP variability and vascular events (ICH, ischemic stroke, MI) within strata defined by hypertension stages (ie, normal BP, elevated BP, hypertension stage 1, and hypertension stage 2) as codified in the 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Guidelines for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. 16 Differences in observed effect sizes based on hypertension severity were explored using forest plots, and statistical significance was determined via heterogeneity of effects testing (as implemented in the metareg function in R). Finally, in order to address potential indication bias we also repeated all analyses investigating the association between long‐term BP variability and MACCE after removing (1) all survivors of ICH with prior history of ischemic stroke or MI and (2) all survivors of ICH on antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy at time of index ICH.

Multiple Testing Adjustment

We corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini‐Hochberg false discovery rate method for adjustment. 17 We report P values after false discovery rate adjustment, applied to all predictors included in univariable and multivariable models (owing to multiple models being created as part of planned analyses). All significance tests were 2 tailed and significance set at P<0.05 (after adjustment). All analyses were performed using R software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing), version 4.1.1.

Results

Study Participants and Follow‐Up Information

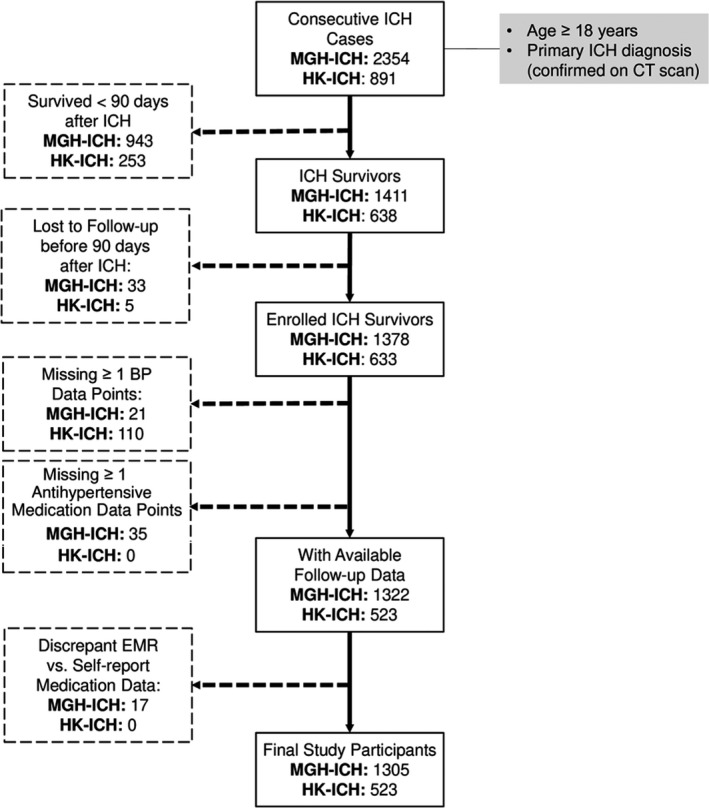

We screened 3245 consecutive patients with ICH (MGH‐ICH study: 2354; HKU‐ICH study: 891) for inclusion in the present study. After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1), we included 1828 survivors of ICH (MGH‐ICH study: 1305, HKU‐ICH study: 523) in all subsequent analyses. Aside from expected differences in self‐reported race and ethnicity, survivors of ICH enrolled at MGH were more likely to be female; older; have a prior medical history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and atrial fibrillation; use statins before index ICH; and present with lobar index ICH (all P<0.05, Table 1). We found that study participants enrolled at HKU presented with higher systolic and diastolic BP at time of hospital admission (both P<0.05). Antihypertensive agents’ prescription patterns also differed between studies (Table 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

BP indicates blood pressure; CT, computed tomography; EMR, electronic medical records; HK, Hong Kong University; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; and MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Table 1.

Study Participants’ Characteristics

| Variables | MGH‐ICH | HKU‐ICH | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of individuals (%) | 1305 (100) | 523 (100) | … |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y, mean, SD | 69.5 (12.1) | 67.3 (14.4) | 0.011 |

| Sex, male | 696 (53) | 326 (62) | <0.001 |

| Race or ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| White | 1125 (86) | 3 (1) | |

| Black | 49 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Hispanic | 59 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Asian | 48 (4) | 517 (99) | |

| Multiple race and ethnicity | 11 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Medical history | |||

| Hypertension | 1021 (78) | 305 (58) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 249 (19) | 99 (19) | 0.99 |

| Coronary artery disease | 255 (20) | 35 (7) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 213 (16) | 38 (7) | <0.001 |

| Prior ICH | 64 (5) | 31 (6) | 0.39 |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 121 (9) | 66 (13) | 0.054 |

| Medication use | |||

| Before index ICH | |||

| Antiplatelet agents | 250 (19) | 107 (20) | 0.54 |

| Oral anticoagulation | 123 (9) | 42 (8) | 0.36 |

| Statins | 455 (35) | 122 (23) | <0.001 |

| After index ICH | |||

| Antiplatelet agents | 153 (12) | 72 (14) | 0.25 |

| Oral anticoagulation | 25 (1) | 13 (3) | 0.46 |

| Statins | 382 (29) | 170 (33) | 0.19 |

| BP at time of index ICH | |||

| Admission systolic BP (mean, SD) | 179 (28) | 183 (29) | 0.008 |

| Admission diastolic BP (mean, SD) | 95 (21) | 99 (19) | 0.034 |

| ICH location | |||

| Lobar | 601 (46) | 116 (22) | <0.001 |

| Nonlobar | 692 (53) | 404 (77) | |

| Mixed | 12 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Hypertension management after ICH | |||

| No. of antihypertensive agents | 0.11 | ||

| None | 114 (9) | 26 (5) | |

| 1 | 296 (23) | 157 (30) | |

| 2 | 447 (34) | 185 (35) | |

| 3 or more | 448 (34) | 155 (30) | |

| Antihypertensive agents classes | 0.021 | ||

| Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker | 811 (62) | 265 (51) | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 503 (39) | 413 (79) | |

| Diuretics | 295 (23) | 31 (6) | |

| Beta blockers | 756 (58) | 188 (36) | |

| Alpha blockers | 124 (10) | 86 (16) | |

Values presented as number (percentage), unless otherwise specified. P values represent results of univariable comparisons between the MGH and HKU studies. BP indicates blood pressure; HKU‐ICH, Hong Kong University ICH study; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; MGH‐ICH, Massachusetts General Hospital ICH study.

We followed participants enrolled at MGH for a total of 5973 person‐years, with median of 50.6 months (interquartile range 41.6–62.3), with a yearly loss to follow‐up rate of 1.1%. During follow‐up in the MGH study we identified 129 recurrent ICH events (annual rate of 4.2%, 95% CI, 3.4–5.4), 43 ischemic stroke events (annual rate of 1.4%, 95% CI, 0.7–2.1), and 40 MI events (annual rate of 1.2%, 95% CI, 0.6–2.0). Study participants enrolled at HKU were followed for a total of 1710 person‐years, with median of 34.6 months (interquartile range 23.5–49.8) and yearly loss to follow‐up rate of 1.4%. Among survivors of ICH enrolled at HKU we observed 37 recurrent ICH events during follow‐up (annual rate 2.9%, 95% CI, 2.0–3.6), 25 ischemic stroke events (annual rate 1.6%, 95% CI, 1.1–2.7), and 29 MI events (annual rate 1.8%, 95% CI, 1.3–3.0).

Determinants of Long‐Term Blood Pressure Variability After Intracerebral Hemorrhage

We conducted univariable and multivariable analyses to identify factors associated with systolic and diastolic BP variability long term. We identified association in univariable analyses (all P<0.05) between greater long‐term systolic BP variability and the following patient characteristics: self‐reported Black and Asian race, history of diabetes, history of hypercholesterolemia, and greater disability after ICH (higher modified Rankin Scale score at discharge). Of note, we found Asian ICH survivors to display higher BP variability in both the MGH (coefficient +2.9, SE 1.0, P=0.043) and HKU (coefficient +2.1, SE 0.4, P=0.011) studies, with no evidence of effect heterogeneity (P=0.45). We also found that higher mean systolic BP during follow‐up was associated with greater long‐term systolic BP variability (coefficient +1.5, SE 0.2, P<0.001). We determined use of calcium channel blockers to be associated with lower long‐term systolic BP variability (coefficient −2.1, SE 0.5, P=0.009), whereas use of beta blockers was associated with greater long‐term systolic BP variability (coefficient +3.3, SE 0.7, P=0.014). Multivariable analyses (Table 2) confirmed that all aforementioned variables were independently associated with systolic BP variability long‐term.

Table 2.

Predictors of BP Variability After ICH

| Variable | Coefficient (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP variability | ||

|

Average systolic BP during follow‐up (per 10 mm Hg incr.) |

+1.1 (0.3) | 0.035 |

| Race: Black | + 3.6 (1.1) | 0.031 |

| Race: Asian | +2.5 (0.3) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes | + 1.7 (0.4) | 0.041 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | +1.8 (0.3) | 0.011 |

| Discharge modified Rankin Scale score (for each point) | +0.7 (0.2) | 0.021 |

| Calcium channel blockers | −2.2 (0.6) | 0.012 |

| Beta blockers | +3.1 (0.6) | 0.009 |

| Diastolic BP variability | ||

| Average diastolic BP during follow‐up (per 10 mm Hg incr.) | +1.9 (0.4) | 0.038 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | +1.1 (0.2) | 0.027 |

All analyses adjusted for age, sex, race or ethnicity, study source (Massachusetts General Hospital vs Hong Kong University), and year of enrollment. BP indicates blood pressure; and ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

Among patient characteristics, history of hypercholesterolemia was associated with greater diastolic BP variability (coefficient 1.4, SE 0.2, P=0.028). We also determined that higher mean diastolic BP during follow‐up was associated with greater diastolic BP variability (coefficient +1.7, SE 0.3, P<0.022). We found no medication exposures to be associated with diastolic BP variability (all P>0.20). Upon creation of a multivariable model we confirmed that average BP during follow‐up and history of hypercholesterolemia were independently associated with diastolic BP variability (Table 2).

Long‐Term BP Variability and Vascular Events After Intracerebral Hemorrhage

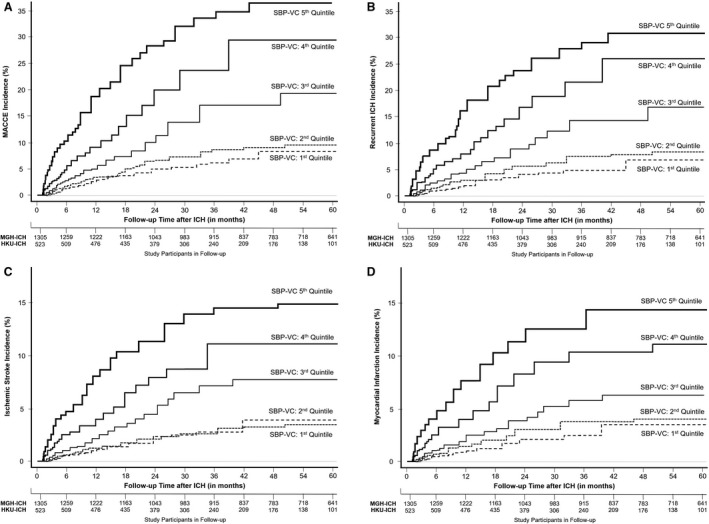

In univariable analyses, individuals’ systolic BP variation coefficients were associated with risk of all MACCE combined (subhazard ratio [SHR], 1.70 per quintile; 95% CI, 1.14–2.52), recurrent ICH (SHR, 1.77 per quintile; 95% CI, 1.14–2.73), ischemic stroke (SHR, 1.68 per quintile; 95% CI, 1.08–2.59), and MI (SHR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.06–2.25). Diastolic BP variation coefficients were not associated with recurrent vascular events after ICH (all P>0.05). We present risk of MACCE (Figure 2A), recurrent ICH (Figure 2B), ischemic stroke (Figure 2C), and MI (Figure 2D) by quintiles of systolic BP variation coefficient in Figure 2. In multivariable analyses (Table 3) we found that systolic BP long‐term variation coefficient was independently associated with all acute vascular outcomes of interest. We present results demonstrating association between MACCE risk after ICH and other long‐term BP variability metrics in Table S1. We also found (Table S2) similar association between long‐term systolic BP variability and risk of MACCE after removal of survivors of ICH (1) with prior history of ischemic stroke or MI or (2) on antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy at time of index ICH.

Figure 2. Blood pressure variability and risk of recurrent vascular events after ICH.

Kaplan‐Meier plots of risk for all MACCE events (A), recurrent ICH (B), ischemic stroke (C), and myocardial infarction (D), based on long‐term systolic blood pressure variability during follow‐up, expressed as quintiles of variation coefficient values. HKU indicates Hong Kong University; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; SBP, systolic blood pressure; and VC, variation coefficient.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analyses of Risk Factors for Major Adverse Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Events After ICH

| All MACCE | Intracerebral hemorrhage | Ischemic stroke | Myocardial infarction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | SHR (95% CI) | P value | SHR (95% CI) | P value | SHR (95% CI) | P value | SHR (95% CI) | P value |

| Education (>12 y) | 0.68 (0.50–0.92) | 0.01 | 0.66 (0.57–0.93) | 0.021 | 0.70 (0.51–0.94) | 0.028 | 0.74 (0.56–0.96) | 0.032 |

| Prior ICH | 1.31 (0.97–1.75) | 0.084 | 2.30 (1.10–4.78) | 0.029 | 1.40 (0.91–2.19) | 0.17 | 1.34 (0.84–2.12) | 0.23 |

| Prior transient ischemic attack/ischemic stroke | 1.55 (1.05–2.27) | 0.029 | 1.61 (0.93–2.76) | 0.094 | 1.88 (1.09–3.22) | 0.029 | 1.25 (0.91–1.70) | 0.16 |

| Race: White | 0.61 (0.41–0.89) | 0.012 | 0.57 (0.34–0.96) | 0.041 | 0.79 (0.65–0.98) | 0.028 | 0.68 (0.45–1.02) | 0.069 |

|

Systolic BP (per 10 mm Hg incr.) |

1.33 (1.08–1.63) | 0.008 | 1.34 (1.05–1.70) | 0.019 | 1.28 (1.03–1.59) | 0.029 | 1.41 (1.05–1.87) | 0.019 |

|

Systolic BP variation coefficient (per quintile) |

1.75 (1.16–2.63) | 0.008 | 1.81 (1.19 – 2.80) | 0.007 | 1.65 (1.05–2.57) | 0.033 | 1.54 (1.04–2.24) | 0.029 |

All analyses adjusted for age, sex, race or ethnicity, study source (Massachusetts General Hospital vs Hong Kong University), year of enrollment, and number of available BP measurements. BP indicates blood pressure; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; SHR, subhazard ratio.

Blood Pressure Variability, Hypertension Severity, and Vascular Events After Intracerebral Hemorrhage

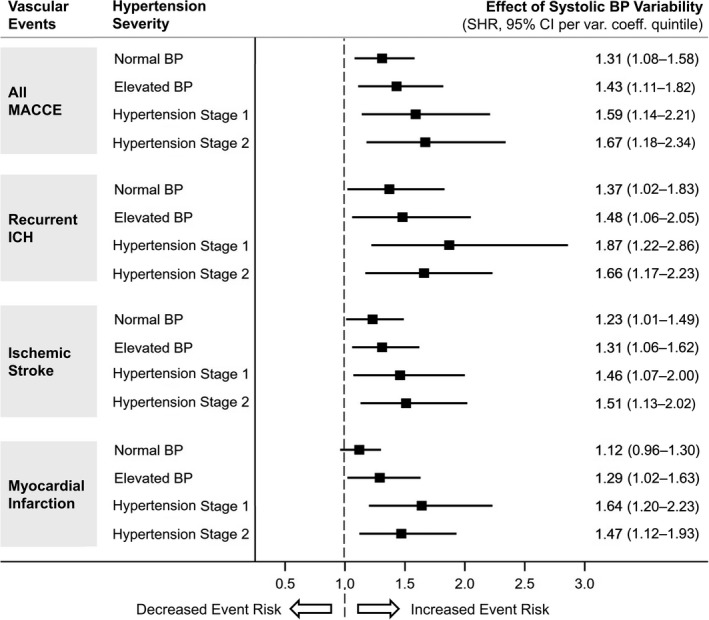

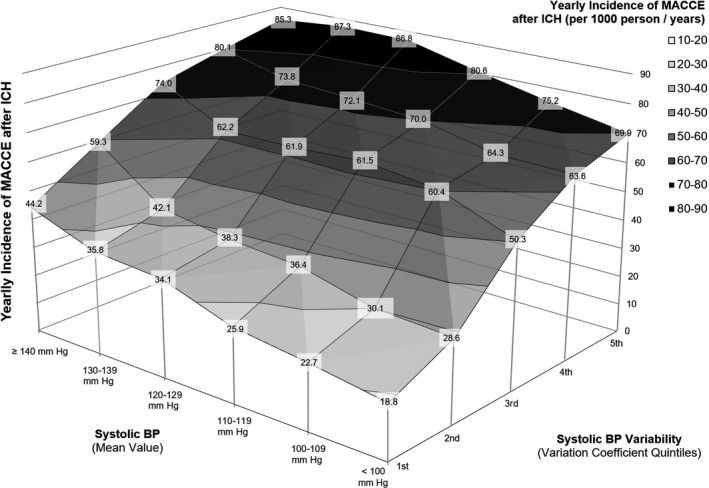

As mentioned previously, we found that systolic BP variation coefficients during follow‐up were associated with recurrent ICH, ischemic stroke, and MI after adjustment for average BP measurements and other relevant patient characteristics and medication exposures (Table 3). In addition, we constructed identical multivariable models within patient subgroups defined by stages of hypertension severity, that is, normal BP, elevated BP, hypertension stage 1, and hypertension stage 2. 16 We allowed for individual participants’ hypertension severity information to vary over time, thus modeling the relationship between average BP and variability dynamically during follow‐up. We found that higher long‐term systolic BP variability was associated with increased risk for all MACCE, recurrent ICH, and ischemic stroke across all stages of hypertension severity, including among patients with normal BP (Figure 3). Long‐term systolic BP variability was associated with MI among survivors of ICH in the elevated BP, hypertension stage 1 and hypertension stage 2 subgroups (Figure 3). We provide a graphical representation of the combined effect of average SBP measurements and their long‐term variability on yearly MACCE incidence during follow‐up in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Hypertension severity, blood pressure variability, and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events after ICH.

Forest plot presenting the association between long‐term systolic BP variability (per quintile of variation coefficient) and MACCE (all events, recurrent ICH, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction) with participants’ subgroups identified by hypertension severity (based on average BP) during follow‐up. BP indicates blood pressure; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; and SHR, subhazard ratio.

Figure 4. Blood pressure control and incidence of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events after ICH.

Surface area graph presenting the yearly incidence of MACCE after ICH (Per 1000 person/years) based on combined values of average systolic BP and BP variation coefficients (by quintiles) during follow‐up. For each subgroup identified by combination of average BP and variation coefficients we report in the labels the exact MACCE yearly incidence observed in our study. Different colors identify combinations of average Bp and its variability at comparable risk for MACCE during follow‐up. BP indicates blood pressure; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; and MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

Discussion

We conducted a longitudinal multicenter study of survivors of ICH and identified associations between long‐term systolic BP variability and risk of MACCE (all events, hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke, and MI) after the initial cerebral hemorrhage. These associations were independent of average BP during follow‐up. We specifically demonstrated that elevated long‐term systolic BP variability is associated with increased risk for MACCE even among patients with normal BP (as defined based on average BP during follow‐up). Our findings support the hypothesis that lowering average BP may not be sufficient to minimize risk of acute vascular events after ICH unless long‐term variability is also brought under control.

Multiple studies previously demonstrated associations between higher average BP and recurrent stroke risk after ICH. 6 , 11 In the PROGRESS (Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study) trial, BP lowering with perindopril in the treatment arm reduced recurrent stroke after ICH by almost half. 7 , 18 Our study adds a critical piece of evidence by clarifying that long‐term BP variability is also likely to play a key role. Because we were able to analyze data for a relatively large group of high‐risk patients, we found evidence that the associations between long‐term BP variability and MACCE are independent of hypertension severity. These findings support focusing future clinical and research efforts on BP control after hemorrhagic stroke to include evaluation of variability over time.

We also found that use of specific antihypertensive medications after ICH was associated with long‐term systolic BP variability. Specifically, use of beta blockers was associated with higher systolic BP variability, whereas use of calcium channel blockers was associated with lower BP variability. These findings are consistent with previous reports from studies of long‐term BP variability after ischemic stroke. 19 , 20 Current European (European Stroke Organisation) and North American (American Heart Association/American Stroke Association) ICH management guidelines do not recommend use or avoidance of specific antihypertensive agents after ICH. 21 , 22 Based on our findings, additional studies (including randomized clinical trials) investigating the specific impact of different antihypertensive classes on MACCE risk after ICH are warranted. Evaluating risks and benefits for MACCE in general versus specific acute vascular events will be of key importance, because individual antihypertensive agents may exert differential effects on risk for hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke, or cardiac ischemia. 23 , 24

Expanding upon previous studies demonstrating evidence of racial or ethnic disparities in average BP after ICH, we found that Black and Asian survivors of ICH also displayed evidence of higher long‐term systolic BP variability. 11 , 25 In turn, these systematic differences in long‐term BP variability control are likely to contribute to established racial or ethnic disparities in recurrent stroke risk after ICH, as we previously demonstrated for average BP. 11 We are limited in our ability to further explore factors accounting for these disparity by the nature of information collected as part of our study. Existing evidence indicates that disparities in access to care, medication affordability, and other factors reflecting systemic racism in the United States are likely to play a major role in explaining disparities among Black survivors of ICH. 26 , 27 Conversely, we found Asian survivors of ICH to be more likely to display higher long‐term BP variability both in the United States and in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, a high‐resource setting with universal health care coverage and a unique historical and socioeconomic context. 28 , 29 Ultimately, additional studies are warranted to clarify social and biological determinants of racial or ethnic disparities in long‐term BP variability after ICH.

Our study has several limitations. First, both the MGH‐ICH and HKU‐ICH cohorts are retrospective analyses of prospective observational studies employing unblinded hypertension control strategies, as determined by individual patients and care providers. Additionally, acute cerebrovascular events have previously been shown to result in subsequent increases in BP variability, which may represent a noncausative marker for increased cerebrovascular and cardiovascular riska. 10 , 30 , 31 Our approach, therefore, cannot identify causal relationships and we are limited to establishing associations between BP measurements and MACCE incidence. Both studies also captured BP measurements using a nonstandardized approach, which may have resulted in imprecise quantification of hypertension severity. In the HKU‐ICH study in particular, ≈17% of eligible patients lacked sufficient BP measurement data. However, nonstandardized BP capture would not be expected to generate false positives associations but rather bias our results toward the null hypothesis. Both enrollment sites are tertiary care centers with expertise in ICH research and care. Our results may not, therefore, be generalizable to survivors of ICH at large, because of the introduction of severity bias in our analyses. However, we previously reported highly consistent findings for the association between elevated BP and recurrent stroke when comparing MGH‐ICH results to those generated by the ERICH (Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage) study, conducted at different academic and community‐based hospitals in the United States. 11 We could not control for several covariates influencing risk of MACCE (eg, physical activity, diet, social determinants of health, and smoking) that were not part of originally collected participant data. Finally, we focused exclusively on long‐term BP variability and its association with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes, as we lack data required to investigate the potential role of short‐term (ie, circadian) variability. Our study also displays numerous strengths. First, we provided novel evidence for long‐term BP variability influencing risk of MACCE among survivors of ICH, a high‐risk population. 4 , 6 , 32 Our analyses focused on highly relevant clinical end points, thus emphasizing the need to further investigate the impact of long‐term BP variability on MACCE risk after ICH. Second, we studied a relatively large sample of consecutive ICH cases from 2 large longitudinal studies using highly compatible, consistently applied enrollment criteria and follow‐up methodologies. Third, considering the differences between the participating studies in geographical location, racial or ethnic demographics, health care delivery, and sociocultural factors, the consistency of our primary findings suggests remarkable generalizability to survivors of ICH at large. Finally, enrollment of a large number of high‐risk participants allowed us to adequately power subgroup analyses across hypertension severity stages, thus providing more robust evidence for an association between long‐term BP variability and MACCE incidence that is independent of average BP.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that long‐term BP variability is associated with increased risk of MACCE after ICH and that this effect is independent of hypertension severity (ie, average BP). This novel finding is of critical importance in the secondary prevention of vascular events in this high‐risk patient population. Future studies exploring biological mechanisms linking long‐term BP variability to MACCE are warranted, ultimately leading to randomized clinical trials examining the effect of long‐term BP variability control following primary ICH.

Sources of Funding

The authors’ work on this study was supported by funding from the US National Institutes of Health (K23NS100816, R01NS093870, R01NS103924, and R01AG26484) and Health and Medical Research Fund, Innovation and Technology Fund for Better Living, The Government of the Hong Kong SAR. The funding entities had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures

Dr Castello, Ms. Abramson, Ms. Keins, Dr Ian YH Leung, Dr William YH Leung, Mr Wong, Ms. Kourkoulis, Dr Myserlis, Mr Warren, Mr Henry, Dr Chan, Dr Cheung, Dr Ho, Dr Gurol, Dr Takahashi, and Dr Towfighi report no conflicts of interest. Dr Teo is supported by Queen Mary Hospital and the Hong Kong Neurological Society Scholarship for Young Neurologist. Dr Viswanathan is supported by P50AG005134. Dr Greenberg is supported by R01AG26484. Dr Christopher D. Anderson is supported by R01NS103924, U01NS069763, the AHA‐Bugher Foundation, receives sponsored research support from Massachusetts General Hospital and Bayer AG, and consulting for ApoPharma and Invitae. Dr Lau is supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund, Innovation and Technology Fund for Better Living, University Grants Committee, The Government of the Hong Kong SAR; has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and received grant support from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai, Pfizer and Sanofi. Dr Rosand is supported by the AHA‐Bugher Foundation, R01NS036695, UM1HG008895, R01NS093870, R24NS092983, and has consulted for New Beta Innovations, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer Inc. Dr Biffi is supported by Massachusetts General Hospital, the AHA‐Bugher Foundation, and by K23NS100816.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S2

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions: Concept and design: Rosand, Biffi. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the article: Castello, Teo, Rosand, Biffi. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Castello, Biffi. Obtained funding: Teo, Greenberg, Anderson, Lau, Rosand, Biffi. Administrative, technical, or material support: Kourkoulis, Warren. Dr Biffi and Dr Castello had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Supplemental Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.024158

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

References

- 1. Poon MT, Fonville AF, Al‐Shahi Salman R. Long‐term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:660–667. doi: 10.1136/Jnnp-2013-306476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cannistraro RJ, Badi M, Eidelman BH, Dickson DW, Middlebrooks EH, Meschia JF. CNS small vessel disease: a clinical review. Neurology. 2019;92:1146–1156. doi: 10.1212/Wnl.0000000000007654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biffi A, Murphy MP, Kubiszewski P, Kourkoulis C, Schwab K, Gurol ME, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A, Anderson CD, Rosand J. APOE genotype, hypertension severity and outcomes after intracerebral haemorrhage. Brain Commun. 2019;1. doi: 10.1093/Braincomms/Fcz018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murthy SB, Diaz I, Wu X, Merkler AE, Iadecola C, Safford MM, Sheth KN, Navi BB, Kamel H. Risk of arterial ischemic events after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020;51:137–142. doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.119.026207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Truelsen T, Krarup L‐H, Iversen HK, Mensah GA, Feigin VL, Sposato LA, Naghavi M. Causes of death data in the global burden of disease estimates for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45:152–160. doi: 10.1159/000441084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biffi A, Anderson CD, Battey TWK, Ayres AM, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A, Rosand J. Association between blood pressure control and risk of recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA. 2015;314:904–912. doi: 10.1001/Jama.2015.10082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arima H, Tzourio C, Anderson C, Woodward M, Bousser M‐Ge, Macmahon S, Neal B, Chalmers J. Effects of perindopril‐based lowering of blood pressure on intracerebral hemorrhage related to amyloid angiopathy: the progress trial. Stroke. 2010;41:394–396. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.563932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barnett MP, Bangalore S. Cardiovascular risk factors: it's time to focus on variability! J Lipid Atheroscler. 2020;9:255–267. doi: 10.12997/Jla.2020.9.2.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stevens SL, Wood S, Koshiaris C, Law K, Glasziou P, Stevens RJ, McManus RJ. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2016;354:I4098. doi: 10.1136/Bmj.I4098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toyoda K, Yamagami H, Kitagawa K, Kitazono T, Nagao T, Minematsu K, Uchiyama S, Tanahashi N, Matsumoto M, Nagata I, et al. Blood pressure level and variability during long‐term prasugrel or clopidogrel medication after stroke: PRASTRO‐I. Stroke. 2021;52:1234–1243. doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.120.032824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodriguez‐Torres A, Murphy M, Kourkoulis C, Schwab K, Ayres AM, Moomaw CJ, Young Kwon S, Berthaud JV, Gurol ME, Greenberg SM, et al. Hypertension and intracerebral hemorrhage recurrence among white, black, and hispanic individuals. Neurology. 2018;91:E37–E44. doi: 10.1212/Wnl.0000000000005729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teo K‐C, Lau GKK, Mak RHY, Leung H‐Y, Chang RSK, Tse M‐Y, Lee R, Leung GKK, Ho S‐L, Cheung RTF, et al. Antiplatelet resumption after antiplatelet‐related intracerebral hemorrhage: a retrospective hospital‐based study. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:85–91. doi: 10.1016/J.Wneu.2017.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Teo KC, Lau G, Mak R, Leung HY, Chang R, Tse MY, Lee R, Leung G, Ho SL, Cheung R, Siu D, Chan KH. Antiplatelet resumption after antiplatelet‐related intracerebral hemorrhage: a retrospective hospital‐based study. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:85‐91. doi: 10.1016/J.Wneu.2017.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Biffi A, Kuramatsu JB, Leasure A, Kamel H, Kourkoulis C, Schwab K, Ayres AM, Elm J, Gurol ME, Greenberg SM, et al. Oral anticoagulation and functional outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:755–765. doi: 10.1002/Ana.25079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine J P. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–609. doi: 10.1161/Circulationaha.115.017719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APHA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College Of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:E13–E115. doi: 10.1161/Hyp.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keselman HJ, Cribbie R, Holland B. Controlling the rate of type I error over a large set of statistical tests. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2002;55:27–39. doi: 10.1348/000711002159680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chapman N, Huxley R, Anderson C, Bousser MG, Chalmers J, Colman S, Davis S, Donnan G, MacMahon S, Neal B, et al. Effects of a perindopril‐based blood pressure‐lowering regimen on the risk of recurrent stroke according to stroke subtype and medical history: the progress trial. Stroke. 2004;35:116–121. doi: 10.1161/01.Str.0000106480.76217.6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Webb AJS, Rothwell PM. Effect of dose and combination of antihypertensives on interindividual blood pressure variability: a systematic review. Stroke. 2011;42:2860–2865. doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.110.611566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O'brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, Sever PS. Effects of beta blockers and calcium‐channel blockers on within‐individual variability in blood pressure and risk of stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:469–480. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70066-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hemphill JC III, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, Becker K, Bendok BR, Cushman M, Fung GL, Goldstein JN, Macdonald RL, Mitchell PH, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46:2032–2060. doi: 10.1161/Str.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Steiner T, Salman R‐S, Beer R, Christensen H, Cordonnier C, Csiba L, Forsting M, Harnof S, Klijn CJM, Krieger D, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:840–855. doi: 10.1111/Ijs.12309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ziff OJ, Samra M, Howard JP, Bromage DI, Ruschitzka F, Francis DP, Kotecha D. Beta‐blocker efficacy across different cardiovascular indications: an umbrella review and meta‐analytic assessment. BMC Med. 2020;18:103. doi: 10.1186/S12916-020-01564-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mehlum MH, Liestøl K, Kjeldsen SE, Wyller TB, Julius S, Rothwell PM, Mancia G, Parati G, Weber MA, Berge E. Blood pressure‐lowering profiles and clinical effects of angiotensin receptor blockers versus calcium channel blockers. Hypertension. 2020;75:1584–1592. doi: 10.1161/Hypertensionaha.119.14443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zahuranec DB, Wing JJ, Edwards DF, Menon RS, Fernandez SJ, Burgess RE, Sobotka IA, German L, Trouth AJ, Shara NM, et al. Poor long‐term blood pressure control after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43:2580–2585. doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.112.663047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levine DA, Duncan PW, Nguyen‐Huynh MN, Ogedegbe OG. Interventions targeting racial/ethnic disparities in stroke prevention and treatment. Stroke. 2020;51:3425–3432. doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.120.030427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Doyle SK, Chang AM, Levy P, Rising KL. Achieving health equity in hypertension management through addressing the social determinants of health. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21:58. doi: 10.1007/S11906-019-0962-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lim MK, Ha SCN, Luk KH, Yip WK, Tsang CSH, Wong MCS. Update on the Hong Kong reference framework for hypertension care for adults in primary care settings‐review of evidence on the definition of high blood pressure and goal of therapy. Hong Kong Med J. 2019;25:64–67. doi: 10.12809/Hkmj187701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lai FTT, Guthrie B, Wong SYS, Yip BHK, Chung GKK, Yeoh E‐K, Chung RY. Sex‐specific intergenerational trends in morbidity burden and multimorbidity status in Hong Kong community: an age‐period‐cohort analysis of repeated population surveys. BMJ Open. 2019;9:E023927. doi: 10.1136/Bmjopen-2018-023927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Béjot Y. Targeting blood pressure for stroke prevention: current evidence and unanswered questions. J Neurol. 2021;268:785–795. doi: 10.1007/S00415-019-09443-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ma Y, Song A, Viswanathan A, Blacker D, Vernooij MW, Hofman A, Papatheodorou S. Blood pressure variability and cerebral small vessel disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of population‐based cohorts. Stroke. 2020;51:82–89. doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.119.026739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casolla B, Moulin S, Kyheng M, Henon H, Labreuche J, Leys D, Bauters C, Cordonnier C. Five‐year risk of major ischemic and hemorrhagic events after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019;50:1100–1107. doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.118.024449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S2

Data Availability Statement

The authors certify they have documented all data, methods, and materials used to conduct the research presented. Anonymized data pertaining to the research presented will be made available upon reasonable request from external investigators.