Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Increased morbidity and mortality from lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) has been suggested in HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) children; however, the contribution of respiratory viruses is unclear. We studied the epidemiology of LRTI hospitalization in HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) and HEU infants aged <6 months in South Africa.

METHODS:

We prospectively enrolled hospitalized infants with LRTI from 4 provinces from 2010 to 2013. Using polymerase chain reaction, nasopharyngeal aspirates were tested for 10 viruses and blood for pneumococcal DNA. Incidence for 2010–2011 was estimated at 1 site with population denominators.

RESULTS:

We enrolled 3537 children aged <6 months. HIV infection and exposure status were determined for 2507 (71%), of whom 211 (8%) were HIV infected, 850 (34%) were HEU, and 1446 (58%) were HUU. The annual incidence of LRTI was elevated in HEU (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–1.5) and HIV infected (IRR 3.8; 95% CI 3.3–4.5), compared with HUU infants. Relative incidence estimates were greater in HEU than HUU, for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV; IRR 1.4; 95% CI 1.3–1.6) and human metapneumovirus–associated (IRR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–2.0) LRTI, with a similar trend observed for influenza (IRR 1.2; 95% CI 0.8–1.8). HEU infants overall, and those with RSV-associated LRTI had greater odds (odds ratio 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–3.8, and 12.2, 95% CI 1.7–infinity, respectively) of death than HUU.

CONCLUSIONS:

HEU infants were more likely to be hospitalized and to die in-hospital than HUU, including specifically due to RSV. This group should be considered a high-risk group for LRTI.

Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) are a common cause of death in children aged <1 year, globally and in South Africa.1,2 Several studies have documented increased burden and severity of acute LRTI in HIV-infected children compared with HIV-uninfected children.3–5

A few studies have reported LRTI to be more common and severe in HIV-exposed but uninfected (HEU) children compared with HIV-unexposed but uninfected (HUU) children; however, there are no data on viral cause-specific incidence of severe LRTI in these children.6–9 In addition, findings have not been consistent, and 1 study reported similar rates of LRTI in HEU and HUU children.10 Similarly, several studies have reported increased mortality rates in HEU infants, whereas others have not found this association.7,11–14 Factors shown to be predictive of mortality in HEU children include malnutrition, clinically diagnosed Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia or very severe pneumonia, severe anemia, not breastfeeding, and advanced maternal HIV.7,10,15,16

The recent expansion of access to strategies for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) has led to marked reductions in HIV acquisition among children born to HIV-infected women, including in South Africa (2.7% in 2011)17; however, the prevalence of HIV among pregnant women and consequently in utero HIV exposure of fetuses, has remained unchanged (30% in 2011).17,18

We aimed to compare the incidence of hospitalization for LRTI, overall and by viral etiology, in HUU, HEU, and HIV-infected infants aged <6 months using data from sentinel surveillance in South Africa. In addition, we aimed to compare the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of HUU, HEU, and HIV-infected infants and assess whether HEU infants are at increased risk of mortality compared with HUU infants.

METHODS

Description of the Surveillance Program

We included data collected from January 2010 through December 2013 from active, prospective, hospital-based surveillance (the Severe Acute Respiratory Illness [SARI] Program) in 3 of the 9 provinces of South Africa (Chris Hani-Baragwanath Academic Hospital [CHBAH] in an urban area of Gauteng Province, Edendale Hospital in a periurban area of KwaZulu-Natal Province, and Matikwana and Mapulaneng Hospitals in a rural area of Mpumalanga Province). In June 2010, an additional surveillance site was introduced at Klerksdorp Hospital in a periurban area of the North West Province.19

Case Definition

A case of hospitalized LRTI was defined as a hospitalized infant with ≤7 days’ symptom duration meeting age-appropriate clinical case definitions (aged 2 days through <3 months of age with physician-diagnosed sepsis or LRTI or aged 3 to <6 months with physician-diagnosis of bronchitis, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, and/or pleural effusion). We included infants aged <3 months with physician-diagnosed sepsis because LRTI could present nonspecifically in this age group.

Study Procedures

All patients admitted from Monday through Friday were eligible for enrollment. The total number of infants admitted meeting study case definitions and numbers enrolled were documented for the entire study period. In 2013, at CHBAH, enrollment of patients was limited to systematically varying 2 of every 5 working days because of high patient numbers and limited resources. Study staff completed case report forms until discharge and collected nasopharyngeal aspirates and blood specimens. All decisions on medical care, including mechanical ventilation and testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, were undertaken at the discretion of the attending physician. Data in case report forms were reviewed regularly to identify inconsistencies, and regular site visits were conducted to ensure adherence to study procedures.

Evaluation of HIV infection and exposure status

The determination of HIV infection and exposure status used information from testing undertaken as part of standard of care during the current admission20 and through anonymized linked dried blood spot specimen testing by HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as part of surveillance. HUU infants were defined as infants with a negative HIV PCR result on admission and a documented or reported negative maternal HIV status. HEU infants were defined as infants with a negative HIV PCR result on admission and a documented or reported positive maternal HIV status. HIV-infected infants were defined as infants with a positive HIV PCR result and CD4+ T-cell counts were determined by flow cytometry as part of standard of care.21 Maternal breastfeeding was not considered in assessment of HIV infection status because PCR results at the time of admission in infants aged <6 months are likely to reflect current infant HIV status irrespective of whether infection was acquired at birth or through breastfeeding. Definitions for other underlying conditions are provided in the Methods section of the online Supplemental Information.

Laboratory Methods

For additional details, please see the online Supplemental Information.

Nasopharyngeal aspirates were immersed in universal transport medium at 4° to 8°C and transported to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases within 72 hours of collection. Specimens were tested by multiplex real-time reverse-transcription PCR for 10 respiratory viruses including influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); enterovirus; human metapneumovirus (hMPV); adenovirus; and human rhinovirus.22 Streptococcus pneumoniae was identified by quantitative real-time PCR detecting the lytA gene from whole blood specimens.23

Estimation of Incidence

Incidence estimates were calculated for Soweto (CHBAH) because population denominators were available for this site. This hospital is the only public hospital serving a community of ~12 000 infants aged <6 months in 2012 among whom <10% have private medical insurance.24 Consequently, the majority of individuals requiring hospitalization from this community are admitted to CHBAH. We estimated the incidence of hospitalization stratified by HIV infection and exposure status for the years 2010 and 2011 because data on HIV prevalence in pregnant women and rates of MTCT were only available for these years.17, 25 We assumed that the HIV exposure and infection status among infants with unknown status was similar to those with known status. We calculated the annual incidence of LRTI hospitalization for infants <6 months of age per 100 00 individuals, by HIV exposure and infection status, by dividing the number of enrolled SARI cases each year (adjusted for nonenrollment on weekends and through refusal) in each category (HUU, HEU, and HIV-infected) by midyear population estimates for each group, multiplied by 100 000. We obtained estimates of the numbers of infants in the population in each HIV exposure group using population denominators for infants aged <1 year from the 2011 census for Region D (Soweto) and dividing these by 2. We then applied published data on HIV prevalence in pregnant women and rates of MTCT from the 2011 National South African PMTCT survey for Gauteng Province, where Soweto is located.25, 26 Etiology-specific numbers were estimated by multiplying the adjusted numbers of SARI cases by the age- and HIV exposure status-specific detection rates for each pathogen. We calculated the relative risk of SARI and etiology-specific hospitalization comparing HUU to HEU and HIV-infected infants. Confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by using the Poisson distribution for incidence rates (IRs) and log binomial model for incidence rate ratios (IRRs).

Factors Associated With HIV Exposure Status and Death

For the analysis of factors associated with HIV-exposure status and death we included infants from any surveillance site from 2010 through 2013 with known HIV exposure status and in-hospital outcome. We implemented 2 multivariable models to identify factors associated with 2 outcome variables: (1) HIV infection/exposure status and (2) mortality. Multinomial regression was used for the comparison of factors associated with HIV infection/exposure. Multinomial regression allows modeling of outcome variables with >2 categories and relates the probability of being in category j to the probability of being in a baseline category. A complete set of coefficients was estimated for each of the j levels being compared with the baseline, and the effect of each predictor in the model was measured as relative risk ratio (RRR). For this analysis, HUU infants were used as the referent group and compared with HEU and HIV-infected infants. The model to assess factors associated with mortality was implemented using logistic regression. For both models, we assessed all variables that were significant at P < .2 on univariate analysis and dropped nonsignificant factors (P ≥ .05) with stepwise backward selection. Patients with missing data for included variables were dropped from the model. In addition, for the mortality analysis, we excluded variables considered to be on the causal pathway for mortality (eg, length of hospital stay, ICU admission). The statistical analysis was implemented using Stata version 12 (StataCorp Inc, College Station, TX). We conducted a sensitivity analysis of the association between HIV exposure and infection status and mortality restricted to individuals with documented maternal HIV status and a separate analysis excluding infants with suspected sepsis. Results of these analyses are reported in the online Supplemental Information.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Enrolled Infants

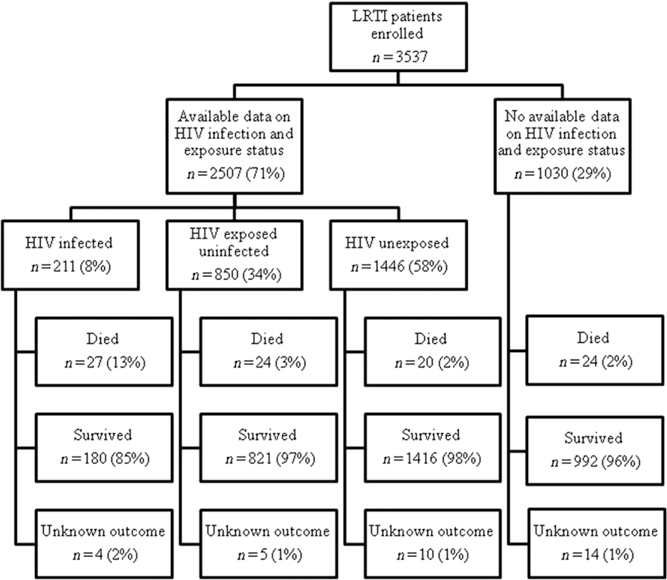

From January 2010 through December 2013, 3537 infants aged <6 months fulfilling the LRTI case definition were enrolled (Fig 1). HIV infection and exposure status were determined in 2507 (71%) enrolled infants. Maternal HIV status was obtained from medical records or laboratory report (vs maternal verbal report) in 27% (229/850) of HEU infants and 19% (268/1446) of HUU infants. The proportion of infants with available HIV exposure status information was 66% (578/878) in 2010, 73% (805/1096) in 2011, 72% (687/949) in 2012, and 71% (437/614) in 2013 (P = .001). A higher proportion of infants had available HIV exposure status information at Edendale (81%, 454/562) and Matikwana/Mapulaneng Hospitals (82%, 367/450) than CHBAH (67%, 1511/2263) or Klerksdorp Hospital (67%, 175/262) (P < .001). Infants with known HIV exposure status did not differ from those with unknown HIV exposure status with regard to other epidemiologic or clinical characteristics such as age group, symptom duration, or in-hospital outcome (data not shown). The proportion of enrolled infants who were HIV infected was 6% (87/1511) at CHBAH, 15% (54/367) at Matikwana/Mapulaneng, 9% (41/454) at Edendale, and 17% (29/175) at Klerksdorp (P < .001). The proportion of infants who were HEU was 31% (468/1511) at CHBAH, 30% (110/367) at Matikwana/Mapulaneng, 44% (201/454) at Edendale, and 41% (71/175) at Klerksdorp (P < .001).

FIGURE 1.

Patients aged <6 months with LRTI enrolled into the SARI surveillance program, South Africa, 2010–2013.

Only 7% (196/2391) of infants had an underlying medical condition other than HIV infection, the commonest of which was premature birth (n = 164). Among infants with available data, 22% (170/773) were malnourished, the overall case fatality ratio was 3% (71/2488), and 2% (55/2493) were admitted to the ICU. Tuberculosis testing was performed on 372 (15%) children, from whom M tuberculosis was identified in 37 (10%) cases (18/195 [9%] in HUU, 13/134 [10%] in HEU, and 6/43 [14%] in HIV infected, P = .640). An additional 43 children were started on tuberculosis treatment based on clinical suspicion without laboratory confirmation (19/1434 [1%] in HUU, 12/845 [1%] in HEU, 12/207 [6%] in HIV-infected, P < .001). Supplemental oxygen was administered to 47% (1160/2493) of enrolled infants. The percentage of infants aged >6 weeks who had received age-appropriate doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine was 76% (1113/1455). Information on receipt of antiretroviral treatment (ART) was only available for 48 of 211 (23%) HIV-infected infants, and 16 (33%) had reported receipt of ART. CD4+ T-cell count was only available for 56 (27%) of HIV-infected infants, and 82% (n = 46) had CD4+ T lymphocytes <25%.27

Incidence of Hospitalization in HUU, HEU, and HIV-Infected Infants in Soweto

The annual incidence (per 100 000 population) of LRTI hospitalization among infants <6 months of age in Soweto was lowest in HUU infants (10 404; 95% CI 9947–10 877), and 1.4-fold higher in HEU (14 288; 95% CI 13 437–15 178; IRR 1.4; 95% CI 1.3–1.5) and 3.7-fold greater among HIV-infected infants (38 445; 95% CI 33 080–44 438; IRR 3.7; 95% CI 3.2–4; Table 1). Among viruses with high likelihood of etiologic attribution, RSV-associated (IRR 1.4; 95% CI 1.3–1.5), hMPV-associated (IRR 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–2.0), and influenza-associated (IRR 1.2; 95% CI 0.8–1.8) LRTI point estimates of incidence were higher in HEU relative to HUU infants, although this was not statistically significant for influenza (for which there was the lowest number of cases, n = 56). For other viruses, estimates were generally similar, although numbers were small in some groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Incidence Rates and Incidence Rate Ratios by HIV Infection and Exposure Status for Infants Aged <6 Months Hospitalized With LRTI in Soweto, South Africa, 2010–2011

| Case | Unadjusted No. of Cases | Incidence Rates per 100 000 Population | Incidence Rate Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HUU (95% CI) | HEU (95% CI) | HIV-Infected (95% CI) | HEU/HUU (95% CI) | HIV-Infected/HUU (95% CI) | ||

|

| ||||||

| All LRTI | 1410 | 10 313 (9858–10 784) | 14 097 (13 252–14 982) | 39 622 (34 179–45 692) | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)a | 3.8 (3.3–4.5)a |

| RSV-associated LRTI | 469 | 3507 (3244–3787) | 5003 (4505–5541) | 6709 (4589–9471) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6)a | 1.9 (1.3–2.7)a |

| Rhinovirus-associated LRTI | 426 | 3074 (2827–3357) | 4581 (4105–5097) | 10 063 (7420–13 342) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7)a | 3.3 (2.4–4.4)a |

| Adenovirus-associated LRTI | 165 | 1253 (1097–1424) | 1563 (1291–1877) | 4612 (2890–6983) | 1.2 (1.0–1.6)a | 3.7 (2.3–5.7)a |

| Enterovirus-associated LRTI | 102 | 680 (567–809) | 1196 (959–1474) | 2935 (1605–4924) | 1.8 (1.3–2.3)a | 4.3 (2.3–7.5)a |

| hMPV-associated LRTI | 78 | 573 (470–692) | 816 (622–1050) | 1887 (863–3582) | 1.4 (1.1–2.0)a | 3.3 (1.5–6.5)a |

| Influenza-associated LRTI | 56 | 434 (344–539) | 503 (354–693) | 1677 (724–3304) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 3.9 (1.6–8.0)a |

| PIV1-associated LRTI | 23 | 139 (91–204) | 354 (231–518) | 0 | 2.5 (1.4–4.6)a | 0 |

| PIV2-associated LRTI | 12 | 107 (65–165) | 95 (38–196) | 0 | 0.9 (0.3–.2) | 0 |

| PIV3-associated LRTI | 72 | 557 (455–675) | 693 (516–912) | 1258 (4616–2738) | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 2.3 (0.8–5.1) |

| Pneumococcus-associated LRTIb | 16 | 139 (90–204) | 109 (47–214) | 629 (130–1838) | 0.8 (0.3–1.8) | 4.5 (0.9–14.7) |

PIV, parainfluenza virus.

Statistically significant values at P < .05.

As determined by lytA PCR on blood.

Characteristics of HUU, HEU, and HIV-Infected Infants

Compared with HUU on multivariable analysis, and controlling for hospital, race, and year of admission, HEU infants were more likely to be hospitalized for 2 to 7 days (adjusted relative risk ratio [aRRR] 1.5; 95% CI 1.3–1.9) or >7 days (aRRR 1.8; 95% CI 1.4–2.4) compared with <2 days; to require mechanical ventilation (aRRR 2.3; 95% CI 1.1–5.0); and to die in-hospital (aRRR 2.1; 95% CI 1.1–3.9; Supplemental Table 4).

Compared with HUU on multivariable analysis controlling for hospital, age, and year, HIV-infected infants were less likely to test positive for RSV (aRRR 0.3; 95% CI 0.2–0.04); however, HIV-infected infants were more likely to be hospitalized for >7 days (aRRR 5.6; 95% CI 3.1–10.0) compared with <2 days, to require oxygen (aRRR 2.0; 95% CI 1.3–2.9) or ventilation (aRRR 2.9; 95% CI 1.1–7.7), and to die in-hospital (aRRR 6.3; 95% CI 3.1–13.1; Supplementa Table 4).

Factors Associated With In-Hospital Mortality

On multivariable analysis, HEU had 2 times (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.1; 95% CI 1.1–4.5), and HIV-infected 5 times (aOR 5.3; 95% CI 2.4–11.8), greater odds of in-hospital mortality compared with HUU infants. PCR detection of pneumococcus in blood was associated with increased mortality (aOR 4.8; 95% CI 1.8–12.7), and detection of any virus (vs no virus detected) was associated with decreased mortality (aOR 0.5; 95% CI 0.2–0.9; Table 2). Mortality was substantially higher at Matikwana/Mapulaneng Hospitals (aOR 17.2; 95% CI 7.0–45.0) compared with CHBAH. When stratified by etiology, for most pathogens, case fatality ratios were elevated in HEU and HIV-infected individuals compared with HIV-uninfected individuals, although numbers of cases and deaths were low in some subgroups (Table 3). Case fatality ratios were significantly elevated for HEU infants with RSV compared with HUU infants.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and Multivariable Analysis Showing Factors Associated With Mortality in HIV-Infected, HEU, and HUU Infants Aged <6 Months Hospitalized With LRTI at 4 Surveillance Sites in South Africa, 2009–2013

| Case Fatality Ratio | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n/N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | aOR (95% CI) | P | |

|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age group | |||||

| ≤28 d | 20/571 (4) | Reference | .751 | — | — |

| >28 d | 75/2933 (3) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | — | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 42/2022 (2) | Reference | .008 | — | — |

| Female | 53/1482 (4) | 1.7 (1.2–2.6) | — | ||

| Race | |||||

| Nonblack | 2/63 (3) | Reference | .821 | — | — |

| Black | 93/3436 (3) | 0.8 (0.2–3.5) | — | ||

| Hospital | |||||

| CHBAH | 27/2247 (1) | Reference | <.001 | Reference | <.001 |

| Matikwana/Mapulaneng | 54/448 (12) | 11.3 (7.0–18.1) | 17.2 (7.0–45.0) | ||

| Edendale | 6/550 (1) | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 1.9 (0.6–6.8) | ||

| Klerksdorp | 8/251 (3) | 2.6 (1.2–5.8) | 1.6 (0.2–13.9) | ||

| Coinfections/underlying medical conditions | |||||

| HIV status | |||||

| HUU | 20/1436 (1) | Reference | <.001 | Reference | <.001 |

| HEU | 24/845 (3) | 2.1 (1.1–3.8) | 2.1 (1.1–4.5) | ||

| HI | 27/207 (13) | 10.6 (5.8–19.3) | 5.3 (2.4–11.8) | ||

| Underlying conditionsa | |||||

| No | 94/3483 (3) | Reference | .678 | — | |

| Yes | 1/21 (5) | 1.8 (0.2–13.5) | — | ||

| Malnutrition | |||||

| No | 17/843 (2) | Reference | .003 | — | |

| Yes | 14/242 (6) | 3.0 (1.4–6.1) | |||

| Pneumococcal coinfection on PCR | |||||

| No | 47/1883 (3) | Reference | .004 | Reference | .001 |

| Yes | 7/93 (8) | 3.2 (1.4–7.2) | 4.8 (1.8–12.7) | ||

| Any viral coinfectionb | |||||

| No | 4/907 (4) | Reference | <.001 | Reference | .010 |

| Yes | 49/2462 (2) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | ||

| Up-to-date for age for PCVc | |||||

| No | 21/466 (5) | Reference | .042 | — | — |

| Yes | 39/1488 (3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | — | — | |

PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. —, not evaluated on multivariable analysis.

Chronic illness, including chronic lung, renal, liver, cardiac disease and diabetes; other immunocompromising conditions (excluding HIV), including organ transplant, primary immunodeficiency, immunotherapy, and malignancy; and other risk factors, including neurologic disorders, malnutrition, and chromosomal abnormalities.

At least 1 of influenza A and B viruses and parainfluenza virus types 1–3, RSV, enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, and human rhinovirus.

Vaccination status determined only for infants eligible to receive the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Additional variables evaluated in the multivariable model but not found to be statistically significant on univariate analysis included year of hospitalization, previous hospitalization, and presence of laboratory-confirmed tuberculosis.

TABLE 3.

Case Fatality Ratio by HIV Infection and Exposure Status Among Infants Aged <6 Months Hospitalized With LRTI at 4 Sites, South Africa, 2009–2013

| Patient Testing Positive by PCR for | Case Fatality Ratio, n/N (%) | ORa (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| HUU | HEU | HI | HEU/HUU | HI/HUU | |

|

| |||||

| RSV | 0/523 (0) | 5/292 (2) | 5/26 (19) | 12.2 (1.7–infinity)b | 158.0 (20.8–infinity)b |

| Rhinovirus | 9/477 (2) | 7/288 (2) | 7/65 (11) | 1.3 (0.5–3.5) | 6.3 (2.3–17.5)b |

| Adenovirus | 2/228 (1) | 3/119 (3) | 5/25 (20) | 2.9 (0.5–17.7) | 28.3 (5.1–155 0)b |

| PIV 1, 2, or 3 | 2/135 (1) | 3/74 (4) | 1/17 (6) | 2.8 (0.3–34.1) | 3.9 (0.1–77.8) |

| hMPV | 1/86 (1) | 0/52 (0) | 0/9 (0) | 1.7 (0–64.5) | 9.6 (0–372.7) |

| Enterovirus | 2/76 (3) | 0/59 (0) | 2/11 (18) | 0.5 (0–6.9) | 7.9 (0.5–121.2) |

| Influenza | 1/54 (2) | 2/28 (7) | 1/6 (17) | 4.1 (0.4–47.1) | 10.6 (0.6–196.4) |

| Pneumococcusc | 2/47 (4) | 3/26 (12) | 2/9 (22) | 2.9 (0.5–18.2) | 6.4 (0.8–53.3) |

| No virus/pneumococcus | 9/322 (3) | 7/185 (4) | 11/89 (12) | 1.4 (0.5–3.7) | 4.9 (2.0–12.2)b |

HI, HIV infected; PIV, parainfluenza virus.

Exact logistic regression used where values in numerator = 0.

Significant results.

On lytA PCR of blood.

DISCUSSION

As a result of the widespread implementation of interventions for PMTCT in South Africa, the numbers of HIV-infected infants continue to decline,17 while the number of HEU infants remains high. We have shown that HEU infants aged <6 months experienced elevated incidence of LRTI hospitalization when compared with HUU infants in Soweto, South Africa. When stratified by etiology, among pathogens with a high etiologic fraction, this association was specifically observed for RSV and hMPV. In addition, once hospitalized, HEU infants were more likely to have a prolonged hospitalization and to die in-hospital compared with HUU infants, highlighting the need for this group to be considered an at-risk group for severe pneumonia.

National guidelines revised in 2013 recommend the initiation of ART in all HIV-infected infants aged <6 months.28 Access to ART for HIV-infected infants has increased in recent years, with an estimated pediatric ART coverage of 63% in South Africa in 2013.29 Despite this reported increased coverage of ART, in our study, HIV-infected infants experienced a 4 times greater risk of hospitalization and 3 times greater in-hospital mortality compared with HUU infants. Estimates of the relative risk of hospitalization are slightly greater than previous estimates for infants aged <12 months from the same study site comparing HIV-infected to HIV-uninfected infants irrespective of HIV exposure status.3 The slightly higher relative risk is to be expected when comparing to a baseline of only HUU as the composite incidence of HEU and HUU together would be somewhat elevated due to the higher incidence in the HEU group. RSV was identified less frequently in HIV-infected than HEU infants, although the incidence of hospitalization for RSV-associated LRTI was greater (although not statistically significantly so) in HIV-infected infants. This is likely because of the proportionately greater contribution of opportunistic pathogens such as Pneumocystis jirovecii and Mycobacterium tuberculosis to LRTI in HIV-infected infants, as has been described previously.3,30,31 We collected results of clinician testing for tuberculosis and clinician initiation of tuberculosis treatment and evaluated this in multivariate models; however, laboratory confirmation of tuberculosis in young infants may be difficult because disease is often paucibacilliary.32

We found a 1.4 times increased incidence of LRTI hospitalization in HEU compared with HUU infants, which was similar to the 1- to 2-fold increased risk of all-cause and LRTI hospitalization in HEU compared with HUU infants reported by others.8,33 Our estimate likely represents a minimum estimate because we relied on maternal history of HIV infection status to determine HIV exposure status. It is possible that some HIV-infected women may have falsely reported their HIV status as HIV uninfected, whereas the converse is unlikely to have occurred. This may have led to some misclassification of HIV exposure status with some HEU infants included in the HUU group, with consequent underestimation of the relative risk of hospitalization in HEU.

In our study, compared with HUU infants, HEU infants hospitalized with LRTI were twice as likely to die in hospital, had longer hospital stays and were more likely to receive mechanical ventilation. Published cohort studies have found that HEU have 2 to 4 times greater risk of all-cause death compared with HUU infants.7,34, 35 Furthermore, infants testing positive for pneumococcus were 5 times more likely to die. This association with more severe outcomes for pneumococcus-associated pneumonia has been previously demonstrated.3 Studies have found whole blood lytA PCR to be specific for pneumococcal pneumonia in young infants; however, positive results may reflect occult bacteremia in some infants.36–38 Patients with any respiratory viral infection were also less likely to die. Respiratory viral pneumonia has been associated with lower case-fatality ratios compared with bacterial pneumonia in previous studies.3 A substantially higher mortality was identified at the Agincourt surveillance site compared with CHBAH. This site is the only rural site included in the surveillance, and worse outcome may relate to delays in access to care or increased burden of underlying illness or poorer quality of care, but data to support these hypotheses are not available.

There are few published data on the relative risk of LRTI hospitalization for specific etiologies in HEU infants.39 Point estimates of relative risk for hospitalization in HEU compared with HUU infants for all 3 viruses with a high etiologic fraction that were evaluated (RSV, hMPV, and influenza) were similar to the overall estimate for LRTI, although the incidence was not statistically significantly elevated for influenza, possibly because of the small numbers of cases of influenza included.40 A nationwide study from South Africa found that HEU patients aged <6 months had 3 to 4 times increased incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease, compared with HUU infants.39

Bacterial coinfection may have contributed to some of the observed increase in hospitalization and in-hospital mortality in patients with confirmed viral infection; however, the numbers of patients testing lytA-positive with available HIV infection and exposure information (n = 16) were too few to explore this hypothesis or make any firm conclusions about pneumococcal epidemiology in HUU. Interpretation of incidence and case-fatality ratios for viruses with a low etiologic fraction is challenging.40

Studies have shown an elevated mortality in HEU infants aged <6 months.7 This elevated mortality as well as the observed increased risks of hospitalization in our study may be the result of immunologic deficits that have been documented in HEU infants.41–44 The degree of maternal immunosuppression has been shown to be an important predictor of infant survival, and ART use in pregnancy may have an impact on infant birth weight and immune response, but we did not have data on maternal CD4+ T-cell count or use of ART during pregnancy in our study to assess this association.45,46 Other possible reasons for the increased risk of severe outcomes observed in HEU infants include possible increased exposure to maternally derived pathogens including cytomegalovirus, reduced transfer of protective antibodies from severely immunosuppressed mothers, and possible impaired responses to some vaccines.46

Our study had several limitations. HIV exposure status was only available for 70% of infants, which could have led to bias if the characteristics of infants with available data differed from those without available data. We did not collect data on breastfeeding, which is an important predictor of mortality in the first 6 months of life.47 Other unmeasured confounders such as patient socioeconomic status could have confounded the associations observed. Patients who die may be less likely to be enrolled, which could lead to underestimation of mortality.48 We were only able to estimate incidence from 1 large urban site for 2 of the study years, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings in South Africa. Low case numbers may have reduced our power to detect differences in incidence for certain pathogens. Additional uncertainty may have been introduced through adjustment for nonenrollment, and this was not included in the estimation of confidence intervals. We obtained denominators in infants aged <6 months by dividing published numbers aged <1 year by 2. This may have introduced bias because mortality may be higher in the first 6 months of life.

CONCLUSIONS

We have described a higher incidence of hospitalization and worse in-hospital outcomes for HEU infants and HIV-infected infants aged <6 months compared with HUU infants. Almost 30% of infants born in South Africa each year are HEU, and this group might benefit from interventions to reduce the burden of LRTI, including access to pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, which has been shown to be effective for HEU infants.17,49 In addition, ongoing access to PMTCT for HIV-infected pregnant women and improved access to ART for HIV-infected infants is important to reduce the LRTI burden in HIV-infected infants.

Supplementary Material

WHAT'S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Increased morbidity and mortality from lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) has been suggested in perinatal HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) children; however, the contribution of respiratory viruses to this has not been defined.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

HEU infants had increased risk of LRTI hospitalization than HIV-unexposed uninfected infants, including specifically due to respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus infection. HEU infants overall, and infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection, had greater odds of death than HIV-unexposed uninfected.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: This study received funding from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases/National Health Laboratory Service and was supported in part by funds from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta, Georgia), Preparedness and Response to Avian and Pandemic Influenza in South Africa (Cooperative Agreement U51/IP000155–04). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. The funders had no role in study design, implementation, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and takes final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Drs Cohen and von Gottberg have received grants from Pfizer and Sanofi. Dr Wolter has received grants from Pfizer. Dr Madhi has received honorarium from GSK, Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi and MERCK. The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Drs Cohen and von Gottberg have received grants from Pfizer and Sanofi. Dr Wolter has received grants from Pfizer. Dr Madhi has received honorarium from GSK, Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi, and MERCK. The other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Dr C. Cohen conceptualized and designed the study, supervised patient enrolment and data collection at the sites, performed the data analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Moyes, Groome, Walaza, Naby, Mekgoe, Kahn, A. Cohen, von Mollendorf, and Madhi were responsible for patient enrollment and data collection at sites and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Tempia was responsible for patient enrollment and data collection at sites, assisted with data analysis, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Pretorius performed the laboratory testing and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs von Gottberg, Wolter, and Venter performed the laboratory testing and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Universities of the Witwatersrand (reference M081042) and KwaZulu-Natal (reference BF157/08). This surveillance was deemed nonresearch by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and did not require human subjects review by that institution. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- aRRR

adjusted relative risk ratio

- ART

antiretroviral treatment

- CHBAH

Chris Hani-Baragwanath Academic Hospital

- CI

confidence interval

- HEU

HIV-exposed uninfected

- hMPV

human metapneumovirus

- hRV

human rhinovirus

- HUU

HIV-unexposed uninfected

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

- LRTI

lower respiratory tract infection

- OR

odds ratio

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PMTCT

prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV

- RRR

relative risk ratio

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- SARI

severe acute respiratory illness

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics South Africa. Statistical Release P030903. Mortality and Causes of Death in South Africa, 2009: Findings From Death Notification. Pretoria, South Africa: Statistics South Africa, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. ; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379(9832): 2151–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen C, Walaza S, Moyes J, et al. Epidemiology of viral-associated acute lower respiratory tract infection among children <5 years of age in a high HIV prevalence setting, South Africa, 2009–2012. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(1):66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madhi SA, Petersen K, Madhi A, Khoosal M, Klugman KP. Increased disease burden and antibiotic resistance of bacteria causing severe community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(1):170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zar HJ, Madhi SA. Childhood pneumonia—progress and challenges. S Afr Med J. 2006;96(9 pt 2):890–900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mussi-Pinhata MM, Freimanis L, Yamamoto AY, et al. ; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development International Site Development Initiative Perinatal Study Group. Infectious disease morbidity among young HIV-1-exposed but uninfected infants in Latin American and Caribbean countries: the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development International Site Development Initiative Perinatal Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/3/e694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marinda E, Humphrey JH, Iliff PJ, et al. ; ZVITAMBO Study Group. Child mortality according to maternal and infant HIV status in Zimbabwe. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(6):519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slogrove A, Reikie B, Naidoo S, et al. HIV-exposed uninfected infants are at increased risk for severe infections in the first year of life. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58(6):505–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNally LM, Jeena PM, Gajee K, et al. Effect of age, polymicrobial disease, and maternal HIV status on treatment response and cause of severe pneumonia in South African children: a prospective descriptive study. Lancet. 2007;369(9571):1440–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preidis GA, McCollum ED, Mwansambo C, Kazembe PN, Schutze GE, Kline MW. Pneumonia and malnutrition are highly predictive of mortality among African children hospitalized with human immunodeficiency virus infection or exposure in the era of antiretroviral therapy. J Pediatr. 2011;159(3):484–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chilongozi D, Wang L, Brown L, et al. ; HIVNET 024 Study Team. Morbidity and mortality among a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected pregnant women and their infants from Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(9):808–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spira R, Lepage P, Msellati P, et al. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in children: a five-year prospective study in Rwanda. Mother-to-Child HIV-1 Transmission Study Group. Pediatrics. 1999;104(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/104/5/e56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutcliffe CG, Scott S, Mugala N, et al. Survival from 9 months of age among HIV-infected and uninfected Zambian children prior to the availability of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):837–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro RL, Lockman S, Kim S, et al. Infant morbidity, mortality, and breast milk immunologic profiles among breast-feeding HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Botswana. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(4):562–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatesh KK, Lurie MN, Triche EW, et al. Growth of infants born to HIV-infected women in South Africa according to maternal and infant characteristics. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(11):1364–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taron-Brocard C, Le Chenadec J, Faye A, et al. ; France REcherche Nord&Sud Sida-HIV Hepatites—Enquete Perinatale Francaise—CO1/CO11 Study Group. Increased risk of serious bacterial infections due to maternal immunosuppression in HIV-exposed uninfected infants in a European country. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(9):1332–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barron P, Pillay Y, Doherty T, et al. Eliminating mother-to-child HIV transmission in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(1):70–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epidemiology and Surveillance, National Department of Health. The National Antenatal Sentinel HIV and Syphilis Prevalence Survey, South Africa, 2011. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen C, Moyes J, Tempia S, et al. Severe influenza-associated respiratory infection in high HIV prevalence setting, South Africa, 2009–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(11):1766–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh E, Cohen C, Govender N, Meiring S. A description of HIV testing strategies at 21 laboratories in South Africa. Commun Dis Surveillance Bull. 2008;6(4):16–17 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glencross D, Scott LE, Jani IV, Barnett D, Janossy G. CD45-assisted PanLeucogating for accurate, cost-effective dual-platform CD4+ T-cell enumeration. Cytometry. 2002;50(2):69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pretorius MA, Madhi SA, Cohen C, et al. Respiratory viral coinfections identified by a 10-plex real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assay in patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory illness—South Africa, 2009–2010. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(suppl 1):S159–S165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carvalho MG, Tondella ML, McCaustland K, et al. Evaluation and improvement of real-time PCR assays targeting lytA, ply, and psaA genes for detection of pneumococcal DNA. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(8):2460–2466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Day C, Gray A. Health and related indicators. In Padarath A, English R, eds. South African Health Review 2012/13. Durban, South Africa: Health Systems Trust; 2013:17 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goga A, Dinh T, Jackson D, Group SS. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the National Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) Programme on Infant HIV Measured at Six Weeks Postpartum in South Africa, 2010. Pretorius, South Africa: South African Medical Research Council, National Department of Health of South Africa and PEPFAR/US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goga A, Dinh T, Jackson D, Group SS. Effectiveness of the National Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) Programme in South Africa—2011 National SAPMTCT survey results. Report released by Minister Aaron Motsoaledi, 2012

- 27.WHO Case Definitions of HIV for Surveillance and Revised Clinical Staging and Immunologic Classification of HIV-Related Disease in Adults and Children. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 28.The South African Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines 2013. Pretorius, South Africa: National Department of Health South Africa; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2013. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en_1.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2016

- 30.Madhi SA, Schoub B, Simmank K, Blackburn N, Klugman KP. Increased burden of respiratory viral associated severe lower respiratory tract infections in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus type-1. J Pediatr. 2000;137(1): 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moyes J, Cohen C, Pretorius M, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus-associated acute lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected South African children, 2010–2011. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(suppl 3):S217–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marais BJ, Hesseling AC, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Enarson DA, Beyers N. The bacteriologic yield in children with intrathoracic tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(8):e69–e71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koyanagi A, Humphrey JH, Ntozini R, et al. ; ZVITAMBO Study Group. Morbidity among human immunodeficiency virus-exposed but uninfected, human immunodeficiency virus-infected, and human immunodeficiency virus-unexposed infants in Zimbabwe before availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(1):45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brahmbhatt H, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected children of HIV-infected and uninfected mothers in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(4):504–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landes M, van Lettow M, Chan AK, Mayuni I, Schouten EJ, Bedell RA. Mortality and health outcomes of HIV-exposed and unexposed children in a PMTCT cohort in Malawi. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azzari C, Cortimiglia M, Moriondo M, et al. Pneumococcal DNA is not detectable in the blood of healthy carrier children by real-time PCR targeting the lytA gene. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(pt 6):710–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rouphael N, Steyn S, Bangert M, et al. Use of 2 pneumococcal common protein real-time polymerase chain reaction assays in healthy children colonized with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(4):452–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dagan R, Shriker O, Hazan I, et al. Prospective study to determine clinical relevance of detection of pneumococcal DNA in sera of children by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(3):669–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Von Mollendorf C, von Gottberg A, Tempia S, et al. Increased risk and mortality of invasive pneumococcal disease in HIV-exposed-uninfected infants <1 year of age in South Africa, 2009–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1346–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pretorius M, Tempia S, Walaza S, et alThe role of influenza, RSV and other common respiratory viruses in severe acute respiratory infections and influenza-like illness in a population with a high HIV sero-prevalence, South Africa 2012–2015. J Clin Virol. 2015;75:21–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Moraes-Pinto MI, Almeida AC, Kenj G, et al. Placental transfer and maternally acquired neonatal IgG immunity in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(5):1077–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rich KC, Siegel JN, Jennings C, Rydman RJ, Landay AL. Function and phenotype of immature CD4+ lymphocytes in healthy infants and early lymphocyte activation in uninfected infants of human immunodeficiency virus-infected mothers. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4(3):358–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velilla PA, Montoya CJ, Hoyos A, Moreno ME, Chougnet C, Rugeles MT. Effect of intrauterine HIV-1 exposure on the frequency and function of uninfected newborns’ dendritic cells. Clin Immunol. 2008;126(3):243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nielsen SD, Jeppesen DL, Kolte L, et al. Impaired progenitor cell function in HIV-negative infants of HIV-positive mothers results in decreased thymic output and low CD4 counts. Blood. 2001;98(2):398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox MP, Brooks DR, Kuhn L, et al. Role of breastfeeding cessation in mediating the relationship between maternal HIV disease stage and increased child mortality among HIV-exposed uninfected children. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(2):569–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afran L, Garcia Knight M, Nduati E, Urban BC, Heyderman RS, Rowland-Jones SL. HIV-exposed uninfected children: a growing population with a vulnerable immune system? Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;176(1):11–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro RL, Lockman S. Mortality among HIV-exposed infants: the first and final frontier. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(3):445–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammitt LL, Kazungu S, Morpeth SC, et al. A preliminary study of pneumonia etiology among hospitalized children in Kenya. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 2):S190–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen C, von Mollendorf C, de Gouveia L, et al. ; South African Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Case-Control Study Group. Effectiveness of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in HIV-infected and -uninfected children in south africa: a matched case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(6):808–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization; UNICEF. WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Malnutrition in Infants and Children. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.