Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown a sex difference in the association between hypertension and cardiovascular disease; however, the precise mechanism remains unclear. Because there are strong associations between metabolic risk factors (MRFs) and hypertension, a sex‐specific analysis of MRFs before hypertension onset could offer new insights and expand our understanding of sex differences in cardiovascular disease. We evaluated cumulative exposure to major MRFs and rate of change of those factors, including body mass index, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol among individuals who did and did not develop hypertension at follow‐up.

Methods and Results

We included 5374 participants (2191 men) initially without hypertension with age range of 20–50 years at baseline who participated in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study, and had been examined at least 3 times during the study period (1999–2018). In both sexes, the cumulative exposure to all MRFs (except for fasting plasma glucose and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in men) were higher in those who developed hypertension, compared with those who did not develop hypertension. However, women experienced greater cumulative exposure to major MRFs, compared with their male counterparts. Also, they experienced a faster increase in waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol than men. Furthermore, rapid increase in systolic blood pressure began earlier in women than men, at the age of 30 years. We also found that those men who developed hypertension experienced unfavorable change in major MRFs during young adulthood (<50 years of age).

Conclusions

Women exhibited more metabolic disturbances than men before onset of hypertension, which may explain the stronger impact of hypertension for major types of cardiovascular disease in women, compared with men.

Keywords: burden, hypertension, metabolic, risk factor, trajectory

Subject Categories: Hypertension

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- FH‐CVD

family history of CVD

- FPG

fasting plasma glucose

- IGC

individual growth curve

- Ln‐triglycerides

log transformation of triglycerides

- MRFs

metabolic risk factors

- PAL

physical activity level

- TLGS

Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study

- WC

waist circumference

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

In this study, during a median follow‐up of >15 years, those with incident hypertension had greater cumulative exposure and faster rates of change of major metabolic risk factors compared with those without incident hypertension.

The differences in cumulative exposure to all metabolic risk factors except for total cholesterol, between those with and without incident hypertension, were significantly higher in women, compared with men.

We found a faster change in waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in women with and without incident hypertension, compared with their male counterparts.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The trajectory of metabolic risk factors may provide additional insight into the pathophysiology and treatment of hypertension.

The higher cumulative exposure and rate of change of major metabolic risk factors before hypertension among women may explain the stronger impact of hypertension on cardiovascular disease in women compared with men.

Prevention and management efforts for cardiovascular disease risk should focus on reducing the hypertension risk burden in women.

Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality worldwide. 1 In 2016, 40.5 million (71%) of worldwide deaths were from noncommunicable diseases. Of these, 17.9 million (44%) deaths were because of CVD, with hypertension as the leading risk factor. 2 Longitudinal studies in major industrialized countries have shown that systolic blood pressure (SBP) rises steadily with increasing age. 3 , 4 Thus, for much of the last century, a progressively increasing blood pressure (BP) was thought to be the consequence of the aging process. 5 However, little to no increase in SBP with aging has been observed in nonindustrialized countries. 3 , 4 , 5 This difference in the age‐associated increase in SBP between populations in industrialized and nonindustrialized countries is generally attributed to environmental and lifestyle factors. 5 Overall, it has been shown that BP level is lower in women than in men during the reproductive years. Also, current studies have reported that at a younger age, women have a lower BP level and less hypertension than similarly aged men, whereas this reverses at older age. 6 Nevertheless, few studies have reported a greater burden of hypertension for women than men. For example, women with hypertension exhibit higher prevalence of arterial stiffness, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, atrial fibrillation, and dementia at an older age compared with hypertensive men. 7 , 8 In the cohort study of UK Biobank, including 471 998 participants, women with hypertension had a 50% higher risk of myocardial infarction, compared with men with hypertension. 9 Also, in another study with 471 971 UK Biobank participants, hypertension was associated with a 36% higher risk of ischemic stroke in women than men. 10 A longitudinal cohort study in the United States among 26 461 participants demonstrated that the excess risk of stroke associated with hypertension was 7% greater in women than men. 11 The INTERHEART global case–control study including 27 098 participants from 52 countries showed that hypertension was associated with a 27% greater excess risk of myocardial infarction in women than men. 12

The mechanisms of sex differences in CVD risk among individuals with hypertension remain unclear. 9 , 10 On the other hand, increasing evidence indicates a strong association between metabolic risk factors (MRFs) and hypertension 13 , 14 in both sexes. Investigation of these MRFs by sex among those who develop hypertension may have important implications for the design of more specific and effective interventions for both sexes. However, most previous studies have focused on these MRFs in a single or limited number of measurements, 15 , 16 ignoring the fact that single measures of MRFs may not reflect the cumulative or lifetime exposures to MRFs. 17 , 18 The trajectory analysis is an effective method that captures changes of risk factor over time. This method allow us to estimate cumulative exposure to MRFs based on their trajectories, which gives a more accurate estimate of the effects of these factors over years, 19 and may contribute to understanding of mechanisms leading to sex differences in hypertension and CVD risk. 20 , 21 , 22 To the best of our knowledge, no study has comprehensively examined the sex difference in cumulative exposure to major MRFs preceding hypertension among adults. We have recently found significant sex differences in the impact of different MRFs on development of hypertension using the single measurement of these factors. 14 The current study extended our previous work in 2 major ways. First, we used repeated measurement of major MRFs including body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), SBP, diastolic BP (DBP), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides, and HDL‐C (high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol) from the TLGS (Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study). Second, using the trajectory of the MRFs among individuals free of hypertension at baseline, we estimated rate of change and cumulative exposure to MRFs in those who did and did not develop hypertension at follow‐up.

Methods

Transparency and Reproducibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Population

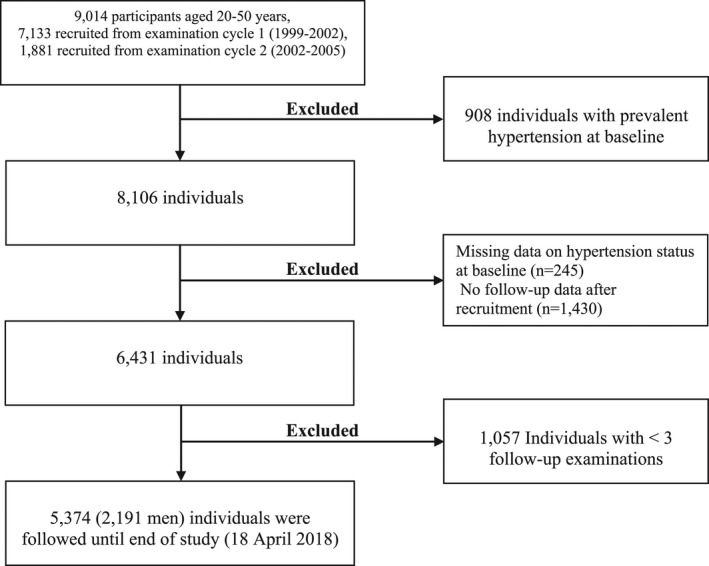

The TLGS is a prospective cohort study of a random sample of residents living in Tehran, capital of Iran, which was designed to understand the risk factors and outcomes for noncommunicable diseases. 23 , 24 The protocol of the TLGS was based on the World Health Organization–recommended model for field surveys of diabetes and other noncommunicable diseases. 25 The first phase of the TLGS was started in 1999 to 2001 in district No. 13, 1 of the 22 districts of Tehran. Age distribution and socioeconomic status of the population in this district was representative of the overall population of Tehran at the recruitment time. 26 , 27 Among 20 medical health centers in district No. 13, 3 health centers were chosen; then, a total of 15 005 individuals aged ≥3 years (response rate: 57.5%) 27 who were under the coverage of these 3 health centers were selected using the multistage cluster random sampling method. There was no significant different between responders and nonresponders. 27 Reexaminations were conducted in intervals of 3 years, and 3550 individuals were added in the second examination. 28 Until now, 6 examinations (phase) 1 (1999–2001), 2 (2002–2005), 3 (2005–2008), 4 (2009–2011), 5 (2012–2015), and 6 (2015–2018) have been conducted in TLGS (Data S1). For the present study, 9014 participants aged 20 to 50 years from the first (n=7133) and second (n=1881) phases were selected and followed until the end of the study (April 18, 2018). We excluded 908 individuals with prevalent hypertension at baseline, 245 people who had missing data on hypertension status at baseline, and 1430 individuals with no follow‐up data after recruitment. Because at least 3 measurements of MRFs were required for studying the trajectory of MRFs, we further excluded 1057 people who did not participate at least 2 times before hypertension incidence or before the last participation for those who did not develop hypertension. Finally, 5374 adults (2191 men) formed the study population (Figure 1). At baseline, <5% of the study population had missing values for several MRFs and other covariates; thus, we chose not to exclude these individuals. The study populations participated 3 to 6 times during the study period (5 times on average). The number of participants who participated 3, 4, 5, and 6 times was 662, 872, 1667, and 2173, respectively. It should be noted that some individuals also had missing values in MRFs in a number of follow‐up examinations. Therefore, the number of participations may not necessarily be equal to the number of measurements. This type of missing values for MRFs is not problematic, because the person‐period data set does not include records for these unobserved phases in longitudinal analysis. 29 Second, <5% of MRFs values were missing in person‐period format. In Table S1 we have presented detailed information about the data set. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. All participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1. Study sample selection flow chart, Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study.

Measurements

Information on age, smoking status, medication use, and family history of CVD (FH‐CVD) was obtained using standardized questionnaires. At each phase, participants also underwent measurements of their anthropometric measures, BP, and biochemical measurements using standardized protocols and assays. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg while the participants were wearing light clothing and no shoes. Body height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm in a standing position. BMI was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by height (meters) squared, and WC was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with participants in a standing position. SBP and DBP were calculated as the average of 2 sequential measurements taken on the left arm of the seated participants who had been resting for at least 5 minutes using a standard mercury column sphygmomanometer with appropriate‐sized cuff. Peripheral blood samples were collected in the morning after a 12‐hour overnight fast for measurements of FPG, TC, triglycerides, and HDL‐C. 24 In the first phase, the Lipid Research Clinics questionnaire 30 was used to measure the physical activity level (PAL). From the second phase, PAL was assessed by the Modifiable Activity Questionnaire. 31

Definition of Terms

Participants self‐reported their smoking status as current smoker versus nonsmoker. A current smoker was a person who smoked cigarettes or other smoking implements daily or occasionally. Nonsmokers included never‐smokers and ex‐smokers. FH‐CVD was defined as reports of coronary heart disease or stroke occurring in relatives before 55 years of age in male relatives and before 65 years of age in female relatives. We categorized PAL as low and high. In the first phase, low PAL was defined as doing exercise or labor <3 times a week, and in the second phase, it was defined as metabolic equivalent tasks minutes of <600 metabolic equivalent tasks per week. 32 Hypertension incidence was defined as a BP level ≥140/90 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive medication.

Statistical Analysis

Because distribution of triglycerides was positively skewed, the natural log transformation of triglycerides (Ln‐triglycerides) was used in all analysis. The characteristics of the study participants at the baseline are described as means for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables, and were compared between those who did and did not develop hypertension. Also, we compared baseline characteristics between participants and nonparticipants. Nonparticipants included those with missing data on hypertension status at baseline, individuals without any follow‐up data, and those with <3 times of participation in the study. The comparisons were done using the Student t test and Pearson χ2 test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

We defined hypertension onset as the first examination at which hypertension criteria were met. For each participant meeting hypertension criteria in a phase, all data after hypertension occurrence were truncated. The trajectories of MRFs were modeled separately in men and women using individual growth curve (IGC) analysis, as we have previously described. 33

Conceptually, IGC models allow researchers to measure change over time in a phenomenon. The time in our study was defined as participant’s age, and we assessed how a MRF varies as a function of age. IGC constructs growth curves of MRFs using the random‐effects mixed model, which incorporates fixed and random effects. Fixed effects are the average change over time or age, and random effects are the individual differences around the fixed effects. In fact, IGC allows investigating 2 levels of variability of a response variable: level (1) within subjects, and level (2) between subjects. One of the advantages of this approach is that it allows for repeated measurements and different numbers of unequally spaced observations across individuals. 29 , 34 We followed the modeling strategy suggested by Mirman 34 and Singer 29 for IGC analysis. Three possible polynomial curves (linear, quadratic, and cubic) of the MRFs were fitted.

For example, to examine a quadratic growth form, the level 1 model could be written as follows:

In this equation, b0i is intercept, b1i carries information about the linear effect of age, and b2i shows the quadratic effect of participant’s age. All of these coefficients are the parameters of the IGC models that vary from individual to individual, and were estimated using the maximum likelihood method. The coefficient of b1i in an IGC model was defined as linear rate of change. For example, if b1i=1.5 and b2i=−0.04, because b1i is positive, the trajectory initially rises, but because b2i is negative, this increase does not persist. 29

The goodness of fit of the models was assessed using likelihood ratio tests and Akaike information criterion. Age and its higher‐order terms were included 1 by 1 in the models. We did not include higher‐order terms of age if they were not significant, or made lower‐order terms not significant, or did not improve the Akaike information criterion values. We centered the age at the grand mean age (41.5 years) to remove collinearity between age and its higher‐order terms in IGC models. 29 We also divided the terms age2 and age3 by 10 and 20, respectively, to stabilize the variance terms. 19 , 29 The characteristics of models are presented in Tables S2 and S3. The cumulative exposure to MRFs was measured as the area under the curve (AUC) of growth curves using the integral of the growth curves for each individual from 20 to 70 years of age divided by 50 to get the annual cumulative exposure to each MRF. 19 , 33 The linear rate of changes of MRFs for each person was defined as the combined (fixed plus random) coefficients of age term in IGC models.

We used 2‐way ANCOVA to test significant differences in the group means of MRFs, AUCs, rates of change, and intercepts. This method allowed us to investigate the simultaneous effects of hypertension status and sex on each MRF by including an interaction term of sex and hypertension status. Also, ANCOVA had an additional benefit of allowing us to adjust for the covariates. The differences in group means were adjusted for baseline age. Also, we further adjusted for FH‐CVD, smoking status, and PAL to examine a significant interaction in the presence of potential confounders. 14 The ANCOVA was applied by general linear model using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20, and IGC analysis was performed in R 3.6.2 using the nlme package 35 and a 2‐sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The characteristics of the study population at the baseline are summarized in Table 1. Of the 5374 participants, (41%) were men, with the mean (SD) ages 33.8 (8.1) and 33.1 (8.1) years in men and women, respectively. In general, individuals without incident hypertension were younger, and had lower levels of BMI, WC, FPG, SBP, DBP, Ln‐triglycerides, and TC, compared with individuals who developed hypertension. They were also less likely to have FH‐CVD and to have low PAL. Baseline characteristics of participants and nonparticipants are presented in Table 2. Participants had lower levels of all MRFs except for TC, compared with nonparticipants. They were also less likely to smoke and more likely to have low PAL.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Men and Women by Hypertension Status at Follow‐Up

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Without hypertension n=1700 |

With hypertension n=491 |

Without hypertension n=2525 |

With hypertension n=658 |

|

| Age, y | 33.2 (8.1) | 35.8 (7.9) | 31.9 (8.0) | 37.7 (7.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.7 (3.9) | 26.4 (3.8) | 25.5 (4.4) | 28.7 (4.7) |

| WC, cm | 85.5 (10.7) | 89.2 (10.2) | 81.5 (11.2) | 89.4 (11.4) |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.0 (0.9) | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.8 (0.7) | 5.1 (1.4) |

| SBP, mm Hg | 110.0 (9.8) | 116.5 (9.5) | 106.4 (9.9) | 115.2 (9.9) |

| DBP, mm Hg | 72.2 (7.8) | 77.5 (7.2) | 71.3 (7.96) | 77.9 (6.5) |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) |

| Ln‐triglycerides, mmol/L | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.9 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.1) | 4.8 (1.0) | 5.2 (1.0) |

| Smokers | 611 (36.0) | 141 (29.0) | 105 (4.2) | 21 (3.2) |

| Family history of CVD (yes) | 230 (13.5) | 93 (18.9) | 350 (13.9) | 127 (19.3) |

| Physical activity (low) | 1144 (70.8) | 389 (81.2) | 1631 (68.8) | 477 (74.4) |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean (SD), and categorical data are presented as frequency (%).

BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Ln‐triglycerides, natural log of triglyceride; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; and WC, waist circumference.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants and Nonparticipants*

|

Nonparticipants n=2732 |

Participants n=5374 |

P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 1228 (44.9) | 2191 (40.8) | <0.001 |

| Age, y | 33.3 (8.7) | 33.4 (8.2) | 0.756 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.1 (4.8) | 25.7 (4.4) | 0.001 |

| WC, cm | 85.6 (12.2) | 84.5 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.1 (1.3) | 4.9 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 111.4 (11.3) | 109.6 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 74.6 (8.4) | 73.0 (8.1) | <0.001 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.011 |

| Ln‐triglycerides, mmol/L | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.9 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.1) | 0.510 |

| Smokers | 581 (23.0) | 878 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| Family history of CVD (yes) | 390 (14.3) | 800 (14.9) | 0.486 |

| Physical activity (low) | 1640 (68.5) | 3641 (71.3) | 0.016 |

Values present mean (SD) for continuous variables and frequency (%) for categorical variables. P values show statistical differences based on t test and χ2 test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Ln‐triglycerides, natural log of triglyceride; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; and WC, waist circumference.

Nonparticipants included those with missing data on hypertension status at baseline, individuals without any follow‐up data, and those with <3 times of participation in the study.

The median (interquartile range) follow‐up of participants was 15.4 (12.5–16.5) years. Study sample included 1149 (491 men) new cases of hypertension. The mean (SD) age of onset of hypertension was 45.9 (8.3) and 47.8 (7.9) years in men and women, respectively.

The mean of MRFs adjusted for baseline age in ANCOVA model are shown in Table 3. Among men and women, levels of BMI, WC, SBP, DBP, TC, and Ln‐triglycerides were higher in those who developed hypertension than those who did not develop it. Furthermore, among those who developed hypertension, women had higher levels of BMI and HDL‐C, but lower level of SBP and Ln‐triglycerides than their male counterparts. Among individuals without incident hypertension, women had significantly higher BMI and HDL‐C, but lower level of WC, FPG, SBP, DBP, and Ln‐triglycerides, compared with their male counterparts (Table 3). There was a significant interaction between sex and hypertension status regarding baseline characteristic, so that the differences between individuals with and without incident hypertension were greater in women than in men for baseline levels of BMI, WC, FPG, SBP, and Ln‐triglycerides. The interaction remained significant after further adjustment for smoking status, PAL, and FH‐CVD (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Adjusted Mean of Metabolic Risk Factors at Baseline Among Individuals Who Did and Did Not Develop Hypertension

| Men (n=2191) | Women (n=3183) | P for sex difference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Without hypertension (n=1700) |

With hypertension (n=491) |

P value* |

Without hypertension (n=2525) |

With hypertension (n=658) |

P value* | Without hypertension | With hypertension | P interaction † | P interaction ‡ | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.8 (0.1) | 26.1 (0.2) | <0.001 | 25.7 (0.1) | 28.1 (0.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WC, cm | 85.6 (0.2) | 88.2 (0.4) | <0.001 | 82.2 (0.4) | 87.5 (0.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.273 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.03 (0.02) | 5.07 (0.04) | 0.359 | 4.89 (0.01) | 5.08 (0.03) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.894 | 0.023 | 0.025 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 110.1 (0.2) | 116.3 (0.4) | <0.001 | 106.5 (0.1) | 115.0 (0.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 72.2 (0.1) | 77.3 (0.3) | <0.001 | 71.5 (0.1) | 77.4 (0.3) | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.677 | 0.067 | 0.056 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 0.97 (0.01) | 0.96 (0.01) | 0.503 | 1.17 (0.01) | 1.12 (0.01) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.073 | 0.051 |

| Ln‐triglycerides, mmol/L | 0.46 (0.01) | 0.57 (0.02) | <0.001 | 0.21 (0.01) | 0.40 (0.02) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.032 | 0.069 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.96 (0.02) | 5.17 (0.04) | <0.001 | 4.95 (0.02) | 5.10 (0.04) | 0.001 | 0.735 | 0.277 | 0.422 | 0.292 |

Values show the mean (SE) adjusted for baseline age in ANCOVA model. BMI indicates body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Ln‐triglycerides, natural logarithm of triglyceride; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; and WC, waist circumference.

P values were adjusted by Bonferroni method and show the statistical difference between those with and without hypertension.

P value shows the significance of interaction term of sex by hypertension status in ANCOVA model adjusted for baseline age.

P value shows the significance of interaction term of sex by hypertension status in ANCOVA model adjusted for baseline age, smoking status, physical activity level, and family history of cardiovascular disease.

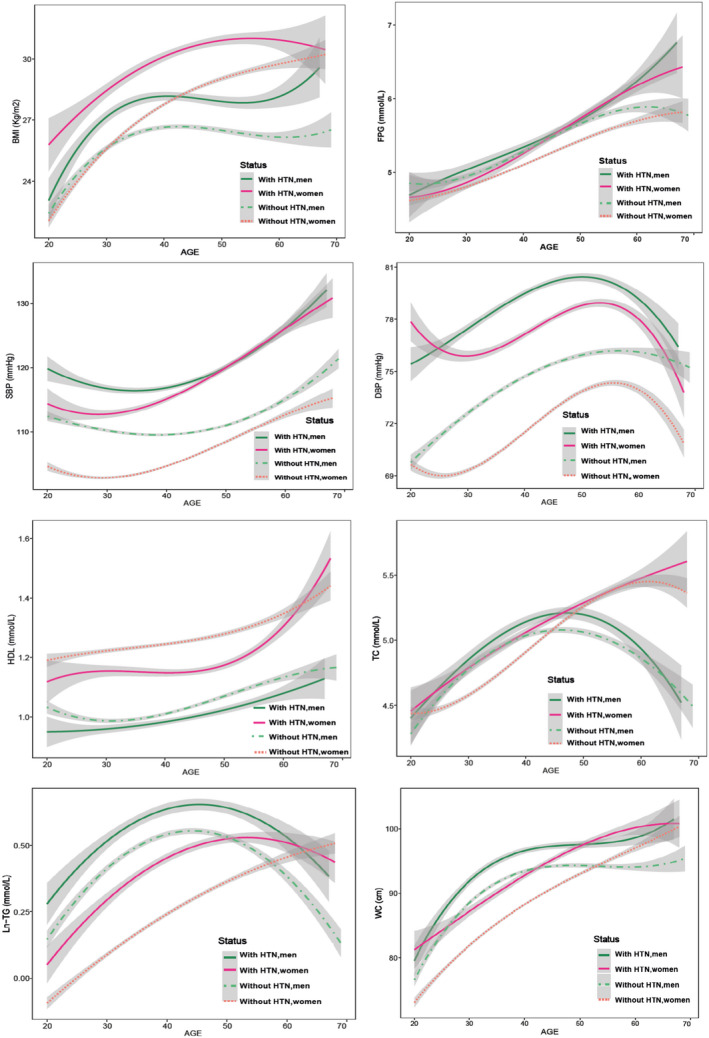

The parameters of the final IGC models for each MRF are presented in Tables S4 and S5. Also, in Figure S1, we have shown the means of predicted values of each MRF among men and women. For easier comparison, in Figure 2, the smoothed curves of each MRF across age are depicted.

Figure 2. Smoothed curves of predicted value for metabolic risk factors by sex and hypertension status.

Gray shading indicates ±SE. BMI indicates body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HTN, hypertension; Ln‐triglycerides, natural logarithm of triglyceride; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; and WC, waist circumference.

The AUC values of MRFs are shown in Table 4. Among women, the age‐adjusted AUC of all MRFs except for HDL‐C were significantly higher in those with incident hypertension, compared with those without incident hypertension. Also, men who developed hypertension had higher AUC for all MRFs except for HDL‐C and FPG. We found that among those with and without incident hypertension, women had significantly higher AUC of BMI, HDL‐C, and TC than men. There were significant interactions between sex and hypertension status regarding AUC of all MRFs except for TC, so that the magnitude of difference between those with and without incident hypertension were remarkably higher in women, compared with men, which remained significant after further adjustment for confounders.

Table 4.

Adjusted Mean of AUC of Metabolic Risk Factors Among Individuals Who Did and Did Not Develop Hypertension

| Men (n=2191) | Women (n=3183) | P for sex difference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Without hypertension (n=1700) |

With hypertension (n=491) |

P value* |

Without hypertension (n=2525) |

With hypertension (n=658) |

P value* |

Without hypertension |

With hypertension | P interaction † | P interaction ‡ | |

| AUC measures (ʃ) | ||||||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.3 (0.1) | 27.8 (0.2) | <0.001 | 27.8 (0.2) | 30.3 (0.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WC, cm | 92.5 (0.2) | 96.2 (0.4) | <0.001 | 90.2 (0.2) | 95.9 (0.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.578 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 5.6 (0.02) | 5.6 (0.04) | 0.074 | 5.3 (0.01) | 5.5 (0.03) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.087 | 0.007 | 0.009 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 113.6 (0.2) | 121.3 (0.3) | <0.001 | 109.2 (0.1) | 121.0 (0.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.525 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 74.9 (0.1) | 79.7 (0.2) | <0.001 | 72.2 (0.1) | 78.2 (0.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 1.1 (0.01) | 1.1 (0.01) | 0.232 | 1.3 (0.01) | 1.2 (0.01) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Ln‐triglycerides, mmol/L | 0.4 (0.01) | 0.5 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.01) | 0.4 (0.01) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.006 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.81 (0.01) | 4.89 (0.02) | 0.012 | 4.96 (0.01) | 5.04 (0.02) | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.957 | 0.882 |

Values were adjusted for baseline age in ANCOVA model. BMI indicates body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Ln‐triglycerides, natural logarithm of triglyceride; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; and WC, waist circumference.

P values were adjusted by Bonferroni method and show the statistical difference between those with and without hypertension.

P value shows the significance of interaction term of sex by hypertension status in ANCOVA model adjusted for baseline age.

P value shows the significance of interaction term of sex by hypertension status in ANCOVA model adjusted for baseline age, smoking status, physical activity level and family history of CVD.

The average of rates of change of MRFs adjusted for age are shown in Table 5. We found that for the positive values for rates of change all MRFs in both sexes, the larger its value, the more rapid the change. Accordingly, men who developed hypertension had faster rates of change in BMI, SBP, Ln‐triglycerides, and TC, compared with men who did not develop it. Among women, those who developed hypertension had significantly faster rates of change in all MRFs except for BMI and Ln‐triglycerides, compared with women who did not develop it. Testing for sex difference showed that women had a higher rate of change in all MRFs except for FPG compared with men among both groups of individuals with and without incident hypertension.

Table 5.

Adjusted Mean of Rate of Change of Metabolic Risk Factors Among Individuals Who Did and Did Not Develop Hypertension

| Men | Women | P for sex difference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Without hypertension (n=1700) |

With hypertension (n=491) |

P value* |

Without hypertension (n=2525) |

With hypertension (n=658) |

P value* | Without hypertension | With hypertension | P interaction † | P interaction ‡ | |

| Rate of change | ||||||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.10 (0.001) | 0.13 (0.002) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.001) | 0.19 (0.002) | 0.926 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WC, cm | 0.52 (0.002) | 0.52 (0.005) | 0.631 | 0.70 (0.002) | 0.75 (0.004) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| FPG, mmol/L | 0.04 (0.003) | 0.05 (0.006) | 0.138 | 0.03 (0.003) | 0.05 (0.005) | 0.048 | 0.258 | 0.728 | 0.827 | 0.837 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 0.19 (0.004) | 0.35 (0.008) | <0.001 | 0.28 (0.003) | 0.56 (0.007) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 0.29 (0.001) | 0.29 (0.001) | 0.336 | 0.30 (0.001) | 0.35 (0.001) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L § | 0.010 (0.000) | 0.010 (0.000) | 0.109 | 0.012 (0.000) | 0.011 (0.000) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.011 | 0.004 |

| Ln‐triglycerides, mmol/L § | 0.002 (0.000) | 0.001 (0.000) | <0.001 | 0.010 (0.000) | 0.010 (0.000) | 0.887 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L § | 0.003 (0.000) | 0.001 (0.000) | <0.001 | 0.024 (0.000) | 0.024 (0.000) | 0.027 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Values show the mean (SE) adjusted for baseline age in ANCOVA model. BMI indicates body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Ln‐triglycerides, natural logarithm of triglyceride; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; and WC, waist circumference.

P values were adjusted by Bonferroni method and show the statistical difference between those with and without hypertension.

P value shows the significance of interaction term of sex by hypertension status in ANCOVA model adjusted for baseline age.

P value shows the significance of interaction term of sex by hypertension status in ANCOVA model adjusted for baseline age, smoking status, physical activity level, and family history of cardiovascular disease.

Maximum 3 digits have been shown after the decimal point for SE.

We found significant interaction between sex and hypertension status in rates of change of MRFs, so that the differences in rates of change in BMI, Ln‐TG, and TC between individuals with and without incident hypertension were greater in men, compared with women, even after adjustment for confounders. However, the differences in rate of change of WC, SBP, DBP, and HDL‐C were higher between women with and without incident hypertension, compared with their male counterparts.

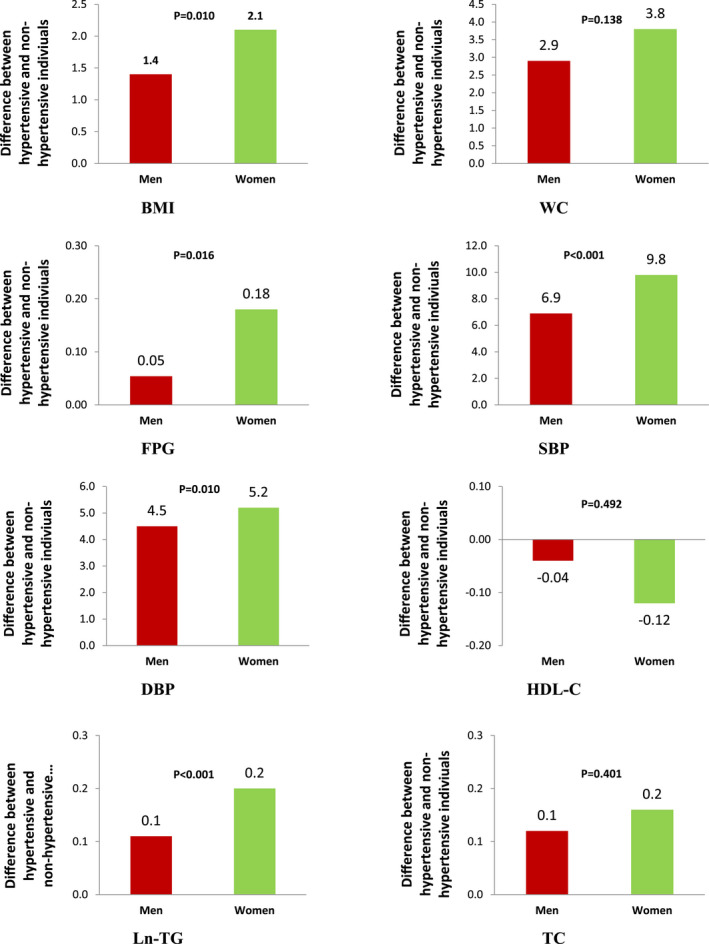

The combined intercepts in each IGC are shown in Figure 3. Because we centered age at 41.5 years, the values show the mean of each MRF at the age of 41.5 years. The differences in mean of BMI, FPG, SBP, DBP, and Ln‐triglycerides between those with and without incident hypertension were greater in women, compared with their male counterparts at the age of 41.5 years.

Figure 3. Differences in age‐adjusted mean values of metabolic risk factors at the age of 45.1 years among hypertensive and nonhypertensive individuals; P values show the statistical significance of interactions of sex by hypertension status.

BMI indicates body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; Ln‐TG, natural logarithm of triglyceride; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; and WC, waist circumference.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report rate of change and cumulative exposure to MRFs preceding hypertension, over a long period. Our results from >5000 Iranian adults, with repeated measurements of MRFs, showed that in both sexes, those with incident hypertension had greater cumulative exposure and faster rates of change of major MRFs compared with those without incident hypertension. However, differences between those with and without incident hypertension were greater in women than men for cumulative exposure to all MRFs except for TC, and for rate of change of WC, SBP, DBP, and HDL‐C.

The sex difference in trajectory BP measures during life course has been recently shown in a multicohort study with a multiethnic population. 36 The study included 32 833 participants (54% women) aged 18–85 years from 4 community cohorts. The trajectory analysis showed a sharper increase in SBP in women, compared with men, which began in the third decade and continued through the life course. In agreement with this study and a number of other studies in industrialized countries, 3 , 4 we found that BP elevation in women begins at the age of 30 years, indicating that among women, the accelerated rise in BP measures begins before they are likely thinking about their risk for heart disease. 20 We further found that women with incident hypertension, compared with men, experienced greater changes in the cumulative exposure and faster rates of change of BP measures over time. Trajectory patterns showed that although women with incident hypertension had lower level of SBP than in men during young adulthood, their SBP rose faster than that of the men, beginning at age 30 years and increased steadily until the age of 50 years, where BP values diverged in men and women.

Such overt sex differences in trajectory of BP elevation may be because of the variety of underlying mechanisms, including variable associations with other MRFs, which are also known to differ between men and women. 6 , 18 We observed that women with incident hypertension, compared with men, experienced greater cumulative exposure to BMI and faster rate of change of WC over time. Previous studies have reported that obesity increases BP in both sexes, but the stronger relation has been established in women, 6 , 37 , 38 so that a comparable increase in BMI causes a greater increase in SBP in women than in men. 6 , 39 Also, a 3‐fold higher risk of hypertension has been reported for obese premenopausal women than for lean women. 6 In our study, the higher cumulative exposure to BMI in women may contribute to the greater change in their BP measures, compared with men. The earlier and steeper BP trajectory and the higher exposure to BMI in women may explain the greater impact of hypertension on major types of CVD including stroke, 10 , 11 , 40 myocardial infarction, 9 , 12 and heart failure 41 in women than men.

Also, it is well established that obese women develop more obesity‐related comorbidities such as hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes than men. 6 In line with current evidence, we found a higher change in triglycerides, HDL‐C, and FPG in women with incident hypertension, compared with men, which may be related to the higher cumulative exposure to BMI in women than men. We observed that among men who developed hypertension, BMI and WC increased rapidly from a low level to their peaks at the age of 40 years, whereas their female counterparts started out at a higher level of BMI and WC, and an accelerated rise in BMI and WC continued beyond the menopausal transition. Also, the peaks of the triglycerides and TC trajectories occurred at earlier ages (around age 45 years) in men who developed hypertension, compared with women, and then started to decline. The rapid increase in BMI and lipids levels among men before the age of 45 years may contribute to the higher prevalence of hypertension in men, compared with women, during young adulthood. 6 , 42 Closely related was the finding that the mean age of hypertension incidence was lower in men than in women (45.9 versus 47.8) in our study.

We further found that women who did not develop hypertension tended to have a higher cumulative exposure to BMI and TC, and faster rates of change in all MRFs except for FPG, than men. Given that obesity has more deleterious effects on cardiovascular health in women compared with men, 6 , 43 and cardioprotection normally observed in premenopausal women is lost by the presence of obesity, 6 development of weight management interventions may improve hypertension and CVD outcomes among Iranian women, considering the higher prevalence of obesity and physical inactivity among them. 44

On the other hand, men who did not develop hypertension had higher cumulative exposure to SBP, DBP, triglycerides, and lower exposure to HDL‐C than their female counterparts, and also, the peaks of BMI, WC, triglycerides, and TC occurred between the ages of 40 and 50 years, indicating that Iranian men may be at higher risk of premature CVD than women. 45 Thus, more tailored interventions should be implemented early in life to prevent hypertension and CVD among Iranian men.

The key strength of our study was a relatively large sample with up to 6 repeated measurements during a 20‐year period. We used direct measurements of weight, height, WC, and MRFs in each follow‐up. Our study also had several limitations. First, ≈32% of eligible participants at baseline were excluded from the analysis (nonparticipants). The statistically but not clinically important differences were observed between the participants versus nonparticipants in some baseline variables. Because participants were generally healthier than nonparticipants, the results may be biased toward an underestimation of incidence of hypertension and thus AUC of MRFs. Second, our findings are subject to residual confounding by other lifestyle factors such as dietary intake. Third, PALs were measured by 2 different questionnaires in the first and second phases. Although we defined a categorical variable (low and high) for PAL, the measurement error because of self‐reported PAL may remain. Additionally, self‐reported smoking status may be less accurate, especially among women, because of increased awareness of the social undesirability of smoking. Finally, our results were obtained from the population of the Tehran urban area. Because complex cultural, economic, and social factors lead to differences in the lived experience between men and women that can also affect physiology and vascular biology, 36 our findings may not be generalizable to other countries and also other rural areas of Iran.

Conclusions

We observed that women who developed hypertension, compared with men, experienced more metabolic disturbances before onset of hypertension, which may explain the greater impact of hypertension on major types of CVD including stroke, myocardial infarction, and heart failure in women than in men. Moreover, men in our study experienced unfavorable change of major MRFs during young adulthood, which will set the stage for development of premature CVD in men. The trajectory of MRFs may provide additional insight into the pathophysiology and treatment of hypertension and optimize prevention and management efforts in both women and men.

Sources of Funding

The TLGS was supported by National Research Council of the Islamic Republic of Iran (grant no. 121).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1

Tables S1–S5

Figure S1

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted in the framework of the TLGS. We express our appreciation to all participants of the study.

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.021922

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

References

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics‐2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD, Bonita R, Rehm J, Kruk ME, Riley LM, Dain K, Kengne AP, Chalkidou K, et al. NCD countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non‐communicable disease mortality and progress towards sustainable development goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2018;392:1072–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mueller NT, Noya‐Alarcon O, Contreras M, Appel LJ, Dominguez‐Bello MG. Association of age with blood pressure across the lifespan in isolated yanomami and yekwana villages. JAMA Cardiology. 2018;3:1247–1249. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodriguez BL, Labarthe DR, Huang B, Lopez‐Gomez J. Rise of blood pressure with age. New evidence of population differences. Hypertension. 1994;24:779–785. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.24.6.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng S, Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, Vasan RS. Blood pressure tracking over the adult life course: patterns and correlates in the Framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2012;60:1393–1399. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.201780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colafella KMM, Denton KM. Sex‐specific differences in hypertension and associated cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:185. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cifkova R, Pitha J, Krajcoviechova A, Kralikova E. Is the impact of conventional risk factors the same in men and women? Plea for a more gender‐specific approach. Int J Cardiol. 2019;286:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beale AL, Meyer P, Marwick TH, Lam CS, Kaye DM. Sex differences in cardiovascular pathophysiology: why women are overrepresented in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2018;138:198–205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Millett ER, Peters SA, Woodward M. Sex differences in risk factors for myocardial infarction: cohort study of UK biobank participants. BMJ. 2018;363:k4247. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peters SA, Carcel C, Millett ER, Woodward M. Sex differences in the association between major risk factors and the risk of stroke in the UK Biobank cohort study. Neurology. 2020;95:e2715–e2726. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madsen TE, Howard G, Kleindorfer DO, Furie KL, Oparil S, Manson JE, Liu S, Howard VJ. Sex differences in hypertension and stroke risk in the REGARDS study: a longitudinal cohort study. Hypertension. 2019;74:749–755. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anand SS, Islam S, Rosengren A, Franzosi MG, Steyn K, Yusufali AH, Keltai M, Diaz R, Rangarajan S, Yusuf S, et al. Risk factors for myocardial infarction in women and men: insights from the INTERHEART study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:932–940. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Piskorz D. Hypertension and metabolic disorders, a glance from different phenotypes. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020;2:100032. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2020.100032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asgari S, Moazzeni SS, Azizi F, Abdi H, Khalili D, Hakemi MS, Hadaegh F. Sex‐specific incidence rates and risk factors for hypertension during 13 years of follow‐up: the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Global Heart. 2020;15:29. doi: 10.5334/gh.780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xiao J, Hua T, Shen H, Zhang M, Wang X‐J, Gao Y‐X, Lu Q, Wu C. Associations of metabolic disorder factors with the risk of uncontrolled hypertension: a follow‐up cohort in rural China. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00789-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hänninen M‐R, Niiranen T, Puukka P, Jula A. Metabolic risk factors and masked hypertension in the general population: the Finn‐Home study. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28:421–426. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oparil S, Acelajado MC, Bakris GL, Berlowitz DR, Cífková R, Dominiczak AF, Grassi G, Jordan J, Poulter NR, Rodgers A, et al. Hypertension. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18014. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ji H, Kim A, Ebinger JE, Niiranen TJ, Claggett BL, Merz CNB, Cheng S. Cardiometabolic risk‐related blood pressure trajectories differ by sex. Hypertension. 2020;75:e6–e9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cook NR, Rosner BA, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Using the area under the curve to reduce measurement error in predicting young adult blood pressure from childhood measures. Stat Med. 2004;23:3421–3435. doi: 10.1002/sim.1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2010;18:598–603. doi: 10.1007/s12471-010-0841-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Bairey Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE. Cardiovascular disease in women: clinical perspectives. Circ Res. 2016;118:1273–1293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Kararigas G. Mechanistic pathways of sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:1–37. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Azizi F. Tehran lipid and glucose study: a national legacy. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2018;16:e84774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Azizi F, Ghanbarian A, Momenan AA, Hadaegh F, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, Mehrabi Y, Zahedi‐Asl S. Prevention of non‐communicable disease in a population in nutrition transition: Tehran lipid and glucose study phase II. Trials. 2009;10:5. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dowse GK, Zimmet P. A model protocol for a diabetes and other noncommunicable disease field survey. World Health Stat Q. 1992;45:360–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azizi F, Zadeh‐Vakili A, Takyar M. Review of rationale, design, and initial findings: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2018;16. doi: 10.5812/ijem.84777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Azizi F, Rahmani M, Emami H, Mirmiran P, Hajipour R, Madjid M, Ghanbili J, Ghanbarian A, Mehrabi J, Saadat N, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in an Iranian urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study (phase 1). Sozial‐und Präventivmedizin. 2002;47:408–426. doi: 10.1007/s000380200008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khalili D, Azizi F, Asgari S, Zadeh‐Vakili A, Momenan AA, Ghanbarian A, Eskandari F, Sheikholeslami F, Hadaegh F. Outcomes of a longitudinal population‐based cohort study and pragmatic community trial: findings from 20 years of the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2018;16:e84748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change And Event Occurrence. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ainsworth BE, Jacobs DR Jr, Leon AS. Validity and reliability of self‐reported physical activity status: the lipid research clinics questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:92–98. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Momenan AA, Delshad M, Sarbazi N, Rezaei Ghaleh N, Ghanbarian A, Azizi F. Reliability and validity of the modifiable activity questionnaire (MAQ) in an Iranian urban adult population. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jeon CY, Lokken RP, Hu FB, Van Dam RM. Physical activity of moderate intensity and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:744–752. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramezankhani A, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. Sex differences in rates of change and burden of metabolic risk factors among adults who did and did not go on to develop diabetes: two decades of follow‐up from the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:3061–3069. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mirman D. Growth Curve Analysis and Visualization Using r. CRC Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R core team (2017) . nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R Package Version 3. 2017;1–131.

- 36. Ji H, Kim A, Ebinger JE, Niiranen TJ, Claggett BL, Merz CNB, Cheng S. Sex differences in blood pressure trajectories over the life course. JAMA Cardiology. 2020;5:19–26. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang Y, Hou L‐S, Tang W‐W, Xu F, Xu R‐H, Liu X, Liu YA, Liu J‐X, Yi Y‐J, Hu T‐S, et al. High prevalence of obesity‐related hypertension among adults aged 40 to 79 years in southwest China. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fujita M, Hata A. Sex and age differences in the effect of obesity on incidence of hypertension in the Japanese population: a large historical cohort study. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilsgaard T, Schirmer H, Arnesen E. Impact of body weight on blood pressure with a focus on sex differences: the Tromsø study, 1986–1995. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2847–2853. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Howard VJ, Madsen TE, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, Rhodes JD, Soliman EZ, Kissela BM, Safford MM, Moy CS, McClure LA, et al. Sex and race differences in the association of incident ischemic stroke with risk factors. JAMA Neurology. 2019;76:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Messerli FH, Rimoldi SF, Bangalore S. The transition from hypertension to heart failure: contemporary update. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ahmad A, Oparil S. Hypertension in women: recent advances and lingering questions. Hypertension. 2017;70:19–26. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.08317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wenger NK. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes for women‐biology, bias, or both? JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:27–28. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Esteghamati A, Abbasi M, Alikhani S, Gouya MM, Delavari A, Shishehbor MH, Forouzanfar M, Hodjatzadeh A, Ramezani RD. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and risk factors associated with hypertension in the Iranian population: the national survey of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases of Iran. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:620–626. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eslami A, Mozaffary A, Derakhshan A, Azizi F, Khalili D, Hadaegh F. Sex‐specific incidence rates and risk factors of premature cardiovascular disease. A long term follow up of the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Tables S1–S5

Figure S1