Abstract

Background

The scope of pericardial involvement in COVID‐19 infection is unknown. We aimed to evaluate the prevalence, associates, and clinical impact of pericardial involvement in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19.

Methods and Results

Consecutive patients with COVID‐19 underwent clinical and echocardiographic examination, irrespective of clinical indication, within 48 hours as part of a prospective predefined protocol. Protocol included clinical symptoms and signs suggestive of pericarditis, calculation of modified early warning score, ECG and echocardiographic assessment for pericardial effusion, left and right ventricular systolic and diastolic function, and hemodynamics. We identified predictors of mortality and assessed the adjunctive value of pericardial effusion on top of clinical and echocardiographic parameters. The study included 530 patients. Pericardial effusion was found in 75 (14%), but only 17 patients (3.2%) fulfilled the criteria for acute pericarditis. Pericardial effusion was independently associated with modified early warning score, brain natriuretic peptide, and right ventricular function. It was associated with excess mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 2.44; P=0.0005) in nonadjusted analysis. In multivariate analysis adjusted for modified early warning score and echocardiographic and hemodynamic parameters, it was marginally associated with mortality (HR, 1.86; P=0.06) and improvement in the model fit (P=0.07). Combined assessment for pericardial effusion with modified early warning score, left ventricular ejection fraction, and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion was an independent predictor of outcome (HR, 1.86; P=0.02) and improved model fit (P=0.02).

Conclusions

In hospitalized patients with COVID‐19, pericardial effusion is prevalent, but rarely attributable to acute pericarditis. It is associated with myocardial dysfunction and mortality. A limited echocardiographic examination, including left ventricular ejection fraction, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and assessment for pericardial effusion, can contribute to outcome prediction.

Keywords: acute pericarditis, COVID‐19, echocardiography, pericardial effusion

Subject Categories: Echocardiography, Ultrasound, Prognosis, Pericardial Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- MEWS

modified early warning score

- TAPSE

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Although acute pericarditis is infrequent among hospitalized patients with COVID‐19, pericardial effusion is common and associated with myocardial dysfunction and excess mortality.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Clinicians taking care of patients with COVID‐19 can use a limited echocardiographic examination for risk stratification, including left ventricular ejection fraction, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and the presence of pericardial effusion.

COVID‐19 infection has a wide range of disease severity, from asymptomatic or mild, self‐limiting illness to severe progressive pneumonia, multiorgan failure, and death. 1 , 2 Reports suggest that cardiac complications are common and are associated with increased mortality. 3 , 4 We have previously shown that the most common cardiac manifestation in consecutive hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 infection is right ventricular (RV) dysfunction or dilatation (39%), followed by left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction (16%) and systolic dysfunction (10%). 5 A recent report evaluated the incidence of cardiac manifestations in a large group of consecutive patients with acute COVID‐19 infection, excluding patients with previous cardiovascular disease. Systolic dysfunction based on low ejection fraction occurred in 3.4%, but in 24% when based on abnormal longitudinal strain. Diastolic dysfunction occurred in 20%, and RV systolic dysfunction was noted in 18%. 6 Cardiac monitoring using clinical, laboratory, and imaging parameters can be used to help risk stratify patients with COVID‐19. 2 , 5 , 7 However, most reports on cardiac involvement focus on myocardial involvement, and reports describing pericardial disease are less common, mostly retrospective or based on systematic literature review, assessing only patients with clinically indicated echocardiographic examinations. 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 More important, none of these reports used a prospectively defined echocardiographic protocol. We sought to define the prevalence and associates of pericardial involvement in consecutive COVID‐19 hospitalized patients of all disease grades, who underwent a prospectively predefined comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation, and to determine its prognostic effect.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. We prospectively studied consecutive adult patients (aged ≥18 years) admitted between March 21, 2020, and September 16, 2020, to the Tel Aviv Medical Center because of COVID‐19 infection. All patients had a diagnosis of COVID‐19 infection confirmed by a positive reverse‐transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay. Demographic data, comorbid conditions, medications, physical examination, laboratory, and ECG findings were systematically recorded. Patients were risk stratified according to their COVID‐19 modified early warning score (MEWS). MEWS is predictive of the need for invasive mechanical ventilation and mortality among patients with COVID‐19. 5 , 21 , 22 All patients underwent comprehensive transthoracic echocardiography within 48 hours of admission as part of a predefined step‐by‐step protocol. Clinical and imaging data were collected prospectively, including the presence or absence of pericardial effusion. For the diagnosis of pericarditis, we used the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for diagnosis and management of pericardial disease based on at least 2 of the 4 criteria of: pericardial chest pain, pericardial rub, new widespread ST‐segment elevation or PR depression on ECG, and pericardial effusion (new or worsening). 23 Mortality analysis started at time of baseline echocardiographic examination and included in‐hospital mortality. Mortality was ascertained until the end of follow up, beyond hospitalization and irrespective of discharge date, for all patients, by telephone calls, and was complete for all the patients. The ethics committee of the Tel Aviv Medical Center approved the study (institutional review board number 0196‐20‐TLV) and voided the requirement of informed consent for the echocardiographic assessment.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed in a standard manner with the same equipment (CX 50; Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA) by cardiologists with expertise in echocardiographic recording and interpretation. In accordance with current guidelines, 24 the following measures were undertaken to minimize the risk of infection: (1) All echocardiographic studies were bedside studies performed at the designated COVID‐19 intensive care or internal ward units. (2) All echocardiographic examinations were performed with small, dedicated scanners because of their easier disinfection. (3) Echocardiographic scanners were set aside in each COVID‐19–designated ward to minimize the risk of infection spread. (4) Personal protection at the time of echocardiographic recordings included N‐95 respirator masks, fluid‐resistant gowns, gloves, head covers, and eye shields. (5) Electrocardiographic monitoring during imaging was omitted, and all measurements were performed offline to reduce exposure and contamination. LV diameters, ejection fraction, and mass were measured as recommended. 25 Measurements of mitral inflow included the peak early filling (E wave) and late diastolic filling (A wave) velocities, E/A ratio, and deceleration time of early filling velocity. Early diastolic mitral septal and lateral annular velocities (e′) were measured in the apical 4‐chamber view. 26 Left atrial volume was calculated with the biplane area‐length method at end systole. Forward stroke volume was calculated from the LV outflow tract with subsequent calculation of cardiac output.

From 4‐chamber views encompassing the entire RV, end‐systolic and end‐diastolic RV areas and tricuspid annulus were measured. RV function was evaluated by tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), systolic tricuspid lateral annular velocity measured in the apical 4‐chamber view, and fractional area change. 25 , 27 Hemodynamic right‐sided assessment included the measurement of the pulmonic flow acceleration time to assess pulmonary vascular resistance. 28

Statistical Analysis

Continuous normally distributed parameters were presented as means±SD and compared using the Student t test. Nonnormally distributed data were presented by median and first and third quartiles and compared using the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro‐Wilk test and visual inspection of quantile‐quantile plots. Categorical data were compared between groups using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test, and expressed as numbers and/or percentages. To analyze the association of pericardial effusion with clinical and cardiac findings, we first performed binary logistic regression univariate analyses with clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic parameters as independent variables and presence of pericardial effusion as dependent variable. For the multivariable analysis, in the first step, all the variables with significant univariate association with pericardial effusion (P<0.05) were grouped into clinical, laboratory, and LV and RV parameters, because many were significantly correlated. In the second step, we assessed correlations between the selected variables within each group to avoid collinearity (R2>0.7; P<0.0001). If any such pairs were found, one of the predictor variables was selected for inclusion in the final analysis and the other was ignored. The variable with the lowest P value was chosen to be included in the final multivariable analysis. To assess if pericardial effusion is independently associated with mortality, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, allowing calculation of adjusted hazard ratio (HR). We first performed univariate Cox hazard analyses with clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic parameters as independent variables and mortality as dependent variable. For the multivariable analysis, in the first step, all the variables with significant univariate association with mortality (P<0.05) were grouped into clinical, laboratory, and LV and RV parameters, because many were significantly correlated. In the second step to detect multicollinearity, we used correlation factor analyses to determine if any pairs of predictor variables were highly correlated (correlation coefficients >0.7) and therefore likely to result in multicollinearity. If any such pairs were found, one of the predictor variables was selected for inclusion in the final analysis and the other was ignored. The variable with the lowest P value was chosen to be included in the final Cox hazard multivariable analysis. Time of follow‐up was calculated between baseline echocardiography and death, or last date of follow‐up. Analysis for survival was obtained for all patients. The survival estimate was calculated using the Kaplan‐Meier method and compared by log‐rank test. Different multivariable nested models were compared with regard to their model fit by computing a χ2 difference test. All data were analyzed with the JMP System software version 14.0 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). All authors participated in designing the study, collecting and analyzing data, and drafting and revising the article.

Results

Prevalence of Pericardial Effusion and Pericarditis

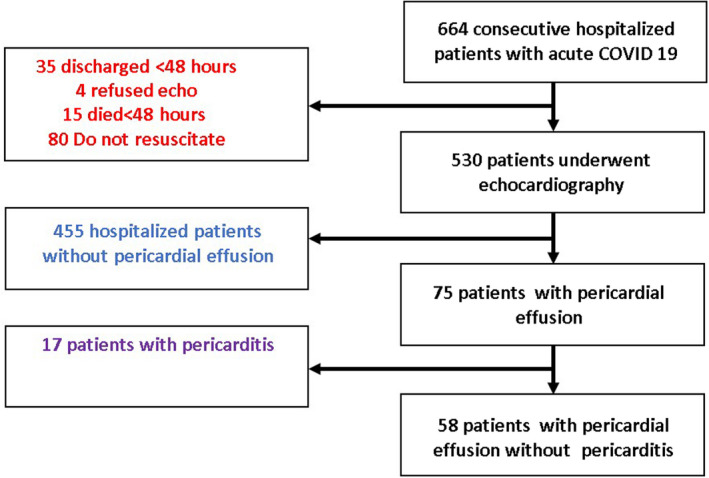

Clinical data were collected for 664 consecutive patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 infection. A total of 134 patients were excluded because they did not undergo echocardiographic assessment (35 were discharged within 48 hours of admission, 4 patients refused, 80 patients had a “do not intubate/resuscitate” status and received palliative care, and 15 patients died within 48 hours from admission). The patient flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing patient selection for the final cohort.

The final study group included 530 patients (aged 63.1±18.3 years; 62% men) who underwent clinical and echocardiographic evaluation. At the time of the baseline evaluation, all patients had COVID‐19 symptoms, and were stratified according to mild/moderate disease (oxygen saturation ≥94% in room air) in 278 (52%), severe disease (need for oxygen supplement) in 233 (44%), and critical disease (need for mechanical ventilation or use of vasopressors and/or extracorporeal life support) in 19 (4%). Of these patients, 75 (14.2%) had pericardial effusion. Pericardial effusion was mild in 72 patients, and moderate in 3 patients. None of the patients in our cohort required pericardial drainage. Only 17 of 75 (22.7%) of the patients with pericardial effusion fulfilled the definition criteria for pericarditis, based on the combination of typical ECG changes (7 patients) and/or typical chest pain (12 patients). There were no patients without pericardial effusion who fulfilled the definition criteria for pericarditis.

Association of Pericardial Effusion With Clinical and Echocardiographic Parameters

Baseline demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic parameters, stratified by patients with or without pericardial effusion, are shown in Table 1. Patients with pericardial effusion were older, had worse disease severity, had higher MEWS, had higher brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and had lower hemoglobin, but did not differ in levels of troponin‐I or CRP (C‐reactive protein). They also had higher prevalence of ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation. Patients with pericardial effusion had poorer RV echocardiographic functional parameters (TAPSE and systolic tricuspid lateral annular velocity), lower cardiac index, higher E/e', higher estimated right atrial pressure, and higher pulmonary vascular resistance. Table 2 shows the odds ratio (OR) of univariate and multivariate analysis for association of pericardial effusion with clinical and echocardiographic parameters. The final univariate and multivariate parameters entered into the model are described under the headings “Univariate analysis OR” and “Multivariable analysis OR.” These analyses suggest that pericardial effusion is independently associated with worse MEWS, higher BNP, and poorer RV function. Table S1 shows the main echocardiographic findings categorized by COVID‐19 severity (mild/moderate versus severe and critical).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Stratified by the Presence or Absence of Pericardial Effusion

| Variables | Pericardial effusion (n=75) | Without pericardial effusion (n=455) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, mean±SD, y | 69.1±16.4 | 62.4±17.6 | 0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 40 (53.3) | 287 (63.08) | 0.12 |

| Disease severity, n (%) | 0.09 | ||

| Mild/moderate | 39 (52) | 239 (53) | 0.03 |

| Severe | 29 (39) | 204 (45) | |

| Critical | 7 (9) | 12 (2) | |

| Modified early warning score, mean±SD | 6.0±3.6 | 4.3±3.4 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index, mean±SD, kg/m2 | 27.6±5.6 | 27.3±5.8 | 0.69 |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 21 (28) | 65 (14.2) | 0.005 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 9 (12) | 38 (8.4) | 0.28 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 12 (16) | 43 (9.45) | 0.1 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 30 (40) | 137 (30.1) | 0.1 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 49 (65.3) | 202 (44.4) | 0.001 |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 4 (5.3) | 10 (2.2) | 0.12 |

| Autoimmune diseases, n (%) | 4 (5.3) | 29 (6.3) | 0.73 |

| Temperature, mean±SD, o C | 37.45±0.99 | 37.51±0.9 | 0.59 |

| Respiratory rate, mean±SD, breaths/min | 17.6±10.2 | 20.14±5.63 | 0.72 |

| O2 saturation, mean±SD, % | 92.08±10.13 | 93.22±7.22 | 0.36 |

| Heart rate, mean±SD, beats/min | 74.1±15.9 | 77.2±14.8 | 0.12 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean±SD, mm Hg | 135.94±24.1 | 135.46±31.08 | 0.87 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean±SD, mm Hg | 71.72±13.83 | 76.95±13.15 | 0.003 |

| Hemoglobin, mean±SD, g/dL | 12.5±2.43 | 13.33±1.9 | 0.006 |

| White blood cells, mean±SD, 103/μL | 8.33±5.54 | 8.2±13.04 | 0.88 |

| Platelets, mean±SD, 103/μL | 216.75±95.89 | 203±59±81.84 | 0.26 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mean±SD, mg/dL | 26.21±24.66 | 20.86±16.42 | 0.077 |

| Thyroid‐stimulating hormone, mean±SD, μIU/mL | 3.3±8.1 | 1.9±5.5 | 0.19 |

| Free thyroxine, mean±SD, ng/dL | 1.2±0.3 | 1.2±0.3 | 0.81 |

| Creatinine, mean±SD, mg/dL | 1.23±1.05 | 1.17±1.37 | 0.65 |

| CRP, mean±SD, mg/L | 94.39±84.51 | 85.58±77.41 | 0.4 |

| D‐dimer, mean±SD, mg/L | 2.75±5.44 | 1.89±3.63 | 0.2 |

| Troponin‐I, mean±SD, ng/L | 267.4±31.5 | 86.2±18 | 0.35 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide, mean±SD, pg/mL | 410.63±915.93 | 130.19±238.57 | 0.044 |

| Bilateral infiltrate, n (%) | 28 (45.16) | 183 (45.75) | 0.85 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 8 (16.67) | 14 (4.59) | 0.0047 |

| ST/T‐wave changes, n (%) | 11 (22.92) | 49 (16.07) | 0.299 |

| Echocardiography | |||

| LVEF, mean±SD, % | 56.36±7.42 | 57.62±6.22 | 0.29 |

| Left ventricle end‐diastolic diameter, mean±SD, mm | 43.15±6.77 | 44.27±6.73 | 0.2 |

| Left ventricle end‐diastolic index, mean±SD, mm/m2 | 23.5±3.4 | 23.5±4.1 | 0.79 |

| Left ventricle end‐systolic diameter, mean±SD, mm | 28.12±7.32 | 28.92±6.53 | 0.38 |

| Left ventricle end‐systolic index, mean±SD, mm/m2 | 15.4±3.6 | 15.2±4.3 | 0.75 |

| Left atrial volume index, mean±SD, mL/m2 | 34.8±17.3 | 30.8±13.1 | 0.09 |

| RV end‐diastolic area index, mean±SD, cm2/m2 | 11.3±2.7 | 11.2±2.5 | 0.77 |

| RV end‐systolic area index, mean±SD, cm2/m2 | 6.5±1.7 | 6.6±2.1 | 0.82 |

| RV fractional area change, mean±SD, % | 41.5±13.0 | 42.2±11.9 | 0.82 |

| TAPSE, mean±SD, cm | 2.01±0.5 | 2.31±0.67 | <0.0001 |

| RV S’, mean±SD, cm/s | 10.33±2.87 | 11.29±2.7 | 0.01 |

| Stroke volume index, mean±SD, mL/m2 | 31.0±9.5 | 32.6±9.3 | 0.24 |

| Cardiac index, mean±SD, L/min per m2 | 2.25±0.78 | 2.60±1.88 | 0.02 |

| E‐wave velocity, mean±SD, cm/s | 72.51±24.09 | 65.44±19.84 | 0.02 |

| A‐wave velocity, mean±SD, cm/s | 66.81±22.15 | 62.24±19 | 0.14 |

| E/A velocity ratio | 1.07±0.4 | 1.5±8.05 | 0.29 |

| e’ Septal velocity, mean±SD, cm/s | 6.24±1.84 | 6.71±2.08 | 0.055 |

| e’ Lateral velocity, mean±SD, cm/s | 7.58±2.54 | 8.73±3.12 | 0.001 |

| E/e’ average velocity ratio, mean±SD | 11.6±5.73 | 9.57±4.54 | 0.006 |

| Right atrial pressure, mean±SD, mm Hg | 9.5±4 | 7.3±3.48 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonic flow acceleration time, mean±SD, ms | 73.33±26.47 | 90.13±26.58 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance index, mean±SD, dynes*s/cm5 per m2 | 309.4±148 | 214.0±148 | <0.0001 |

LVEF indicates left ventricular ejection fraction; RV, right ventricle; RV S’, systolic tricuspid lateral annular velocity; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Table 2.

OR for Association of Pericardial Effusion and Clinical, Laboratory, and Echocardiographic Parameters

| Parameter | Univariate analysis OR | Multivariate analysis OR |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical and laboratory | ||

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.04)* | |

| MEWS | 1.13 (1.05–1.21)* | 1.16 (1.03–1.32)* |

| Hemoglobin | 0.82 (0.73–0.93)* | |

| BUN | 1.01 (1.002–1.02) † | |

| Creatinine | 1.03 (0.88–1.22) | |

| BNP | 1.001 (1.0003–1.002)* | 1.001 (1.004–1.002)* |

| Troponin‐I | 1.000 (0.99–1.004) | |

| CRP | 1.001 (0.99–1.004) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2.33 (1.32–4.1)* | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.04 (1.06–3.9) † | |

| Left ventricle | ||

| LVEF | 0.97 (0.94–1.02) | |

| Stroke volume index | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | |

| Cardiac index | 0.63 (0.42–0.95) † | |

| E/e' velocity ratio | 1.07 (1.03–1.12)* | |

| Right ventricle | ||

| TAPSE | 0.31 (0.18–0.53)* | 0.47 (0.21–0.97) † |

| RV S’ | 0.86 (0.78–0.96)* | |

| RA pressure | 1.15 (1.08–1.22)* | |

| Pulmonic acceleration time | 0.97 (0.96–0.98)* | |

| Calculated PVR index | 1.005 (1.003–1.007)* | |

| χ2 Value for multivariate model | 31.8 | |

| P value for multivariate model | <0.0001 | |

| AUC for multivariate model | 0.77 | |

AUC indicates area under the curve; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C‐reactive protein; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MEWS, modified early warning score; OR, odds ratio; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RA, right atrial; RV S’, systolic tricuspid lateral annular velocity; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

P<0.005.

P<0.05.

Association of Pericardial Effusion With All‐Cause Mortality

There were 97 deaths (18.3%) among the 530 patients who underwent echocardiography. All‐cause mortality was higher in patients with pericardial effusion (25/75 [33.3%] versus 72/455 [15.8%]; P=0.0007). Kaplan‐Mayer analysis for overall survival, stratified by the presence of pericardial effusion, is shown in Figure 2. Univariate associates of mortality are shown in Table S2. Clinical parameters associated with mortality were age, MEWS, troponin‐I, and BNP. LV echocardiographic parameters associated with mortality included LV ejection fraction (LVEF), stroke volume index, and E/e'. RV echocardiographic parameters associated with mortality included RV end‐systolic area, TAPSE and systolic tricuspid lateral annular velocity, right atrial pressure, and shorter pulmonic acceleration time. Multivariate associates of mortality are shown in Table 3. The final univariate and multivariate parameters entered into the Cox hazard model are described under the headings “Univariate analysis HR” and “Multivariable analysis HR.” In multivariate analysis adjusted for echocardiographic and hemodynamic parameters, pericardial effusion was marginally associated with mortality (HR, 1.83 [95% CI, 0.95–3.4]; P=0.06), and improved the model fit in nested model (P=0.05 for χ2 difference test). In multivariate analysis adjusted for echocardiographic variables, hemodynamic parameters, and MEWS, pericardial effusion was marginally associated with mortality (HR, 1.86 [95% CI, 0.95–3.5]; P=0.06), and marginally improved the model fit in nested model (P=0.07 for χ2 difference test). In multivariate analysis adjusted for significant clinical parameters, echocardiographic variables, hemodynamic parameters, and MEWS, pericardial effusion was marginally associated with mortality (HR, 1.96 [95% CI, 0.89–4.09]; P=0.09), and marginally improved the model fit in nested model (P=0.09 for χ2 difference test).

Figure 2. Outcome of patients with COVID‐19 infection, stratified according to presence or absence of pericardial effusion.

Overall survival in patients with COVID‐19 infection, comparing patients with pericardial effusion (blue line) and no pericardial effusion (red line).

Table 3.

HR for Association of Pericardial Effusion With Mortality

| Variable | Univariate analysis HR | Multivariate analysis HR |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality with echocardiographic findings | ||

| Pericardial effusion | 2.44 (1.50–3.83); P=0.0005 | 1.83 (0.95–3.4); P=0.06 |

| Ejection fraction | 0.95 (0.93–0.98); P=0.0008 | 1.02 (0.98–1.07); P=0.26 |

| Stroke volume index | 0.95 (0.91–0.98); P=0.001 | 0.95 (0.91–0.99); P=0.01 |

| E/e' average | 1.09 (1.06–1.11); P<0.0001 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10); P=0.003 |

| Pulmonic AT | 0.97 (0.96–0.98); P<0.0001 | 0.98 (0.96–0.99); P=0.003 |

| TAPSE | 0.4 (0.27–0.63); P<0.0001 | 1.10 (0.57–1.64); P=0.74 |

| χ2 Value for model | 46.7 | |

| P value for model | <0.0001 | |

| AIC | 534 | |

| χ2 Value for model without pericardial effusion | 42.9 | |

| P value for χ2 difference test for nested model | 0.05 | |

| Mortality with echocardiographic findings and MEWS | ||

| Pericardial effusion | 2.44 (1.50–3.83); P=0.0005 | 1.86 (0.95–3.5); P=0.06 |

| Ejection fraction | 0.95 (0.93–0.98); P=0.0008 | 1.04 (0.98–1.09); P=0.1 |

| Stroke volume index | 0.95 (0.91–0.98); P=0.001 | 0.96 (0.93–0.99); P=0.04 |

| E/e' average velocity | 1.09 (1.06–1.11); P<0.0001 | 1.08 (1.03–1.12); P=0.0006 |

| Pulmonic AT | 0.97 (0.96–0.98); P<0.0001 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00); P=0.45 |

| TAPSE | 0.4 (0.27–0.63); P<0.0001 | 1.10 (0.71–1.43); P=0.55 |

| MEWS | 1.4 (1.32–1.51); P<0.0001 | 1.47 (1.33–1.64); P<0.0001 |

| χ2 Value for model | 102.6 | |

| P value for model | <0.0001 | |

| AIC | 452.9 | |

| χ2 Value for model without pericardial effusion | 99.1 | |

| P value for χ2 difference test for nested model | 0.07 | |

| Mortality with echocardiographic findings, MEWS, and other clinical parameters | ||

| Pericardial effusion | 2.44 (1.50–3.83); P=0.0005 | 1.96 (0.89–4.09); P=0.09 |

| Ejection fraction | 0.95 (0.93–0.98); P=0.0008 | 1.02 (0.98–1.09); P=0.24 |

| Stroke volume index | 0.95 (0.91–0.98); P=0.001 | 0.96 (0.92–1.01); P=0.13 |

| E/e' average velocity | 1.09 (1.06–1.11); P<0.0001 | 0.97 (0.90–1.09); P=0.25 |

| Pulmonic AT | 0.97 (0.96–0.98); P<0.0001 | 1.001 (0.98–1.02); P=0.87 |

| TAPSE | 0.4 (0.27–0.63); P<0.0001 | 0.59 (0.25–1.36); P=0.22 |

| MEWS | 1.4 (1.32–1.51); P<0.0001 | 1.27 (1.13–1.43); P<0.0001 |

| Troponin | 4.1 (2.7–6.2); P<0.0001 | 1.000 (0.99–1.00001); P=0.17 |

| BNP | 4.9 (3.0–8.3); P<0.0001 | 1.0001 (1.006–1.009); P=0.04 |

| Age | 1.07 (1.06–1.09); P<0.0001 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10); P=0.002 |

| χ2 Value for model | 77.2 | |

| P value for model | <0.0001 | |

| AIC | 326.1 | |

| χ2 Value for model without pericardial effusion | 74.4 | |

| P value for χ2 difference test for nested model | 0.09 | |

| Mortality with focused echocardiography | ||

| Pericardial effusion | 2.44 (1.50–3.83); P=0.0005 | 2.3 (1.39–3.68); P=0.0007 |

| Ejection fraction | 0.95 (0.93–0.98); P=0.0008 | 0.97 (0.94–1.00); P=0.05 |

| TAPSE | 0.4 (0.27–0.63); P<0.0001 | 0.55 (0.34–0.88); P=0.01 |

| χ2 Value for model | 29.7 | |

| P value for model | <0.0001 | |

| AIC | 1020.5 | |

| χ2 Value for model without pericardial effusion | 19.6 | |

| P value for χ2 difference test for nested model | 0.0001 | |

| Mortality with focused echocardiography and MEWS | ||

| Pericardial effusion | 2.44 (1.50–3.83); P=0.0005 | 1.86 (1.09–3.07); P=0.02 |

| Ejection fraction | 0.95 (0.93–0.98); P=0.0008 | 0.97 (0.95–1.00); P=0.05 |

| TAPSE | 0.4 (0.27–0.63); P<0.0001 | 0.88 (0.59–1.13); P=0.41 |

| MEWS | 1.4 (1.32–1.51); P<0.0001 | 1.39 (1.29–1.49); P<0.0001 |

| χ2 Value for model | 118.7 | |

| P value for model | <0.0001 | |

| AIC | 797.6 | |

| χ2 Value for model without pericardial effusion | 113.0 | |

| P value for χ2 difference test for nested model | 0.02 | |

AIC indicates Akaike information criterion; AT, acceleration time; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; HR, hazard ratio; MEWS, modified early warning score; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Focused Cardiac Ultrasound and Pericardial Effusion

We analyzed whether addition of evaluation for pericardial fluid increases the predictive ability above a simple echocardiographic assessment using only TAPSE and ejection fraction, without Doppler parameters. Although this simplified evaluation was inferior to the complete echocardiographic examination that included the Doppler hemodynamic parameters, it was still significantly associated with mortality and additive to clinical assessment and MEWS (Table 3). In multivariate analysis adjusted for TAPSE and ejection fraction, pericardial effusion was associated with mortality (HR, 2.3 [95% CI, 1.39–3.68]; P=0.0007), and improved the model fit in nested model (P=0.0001 for χ2 difference test). In multivariate analysis adjusted for TAPSE, LVEF, and MEWS, pericardial effusion was associated with mortality (HR, 1.86 [95% CI, 1.09–3.07]; P=0.02), and improved the model fit in nested model (P=0.02 for χ2 difference test).

Discussion

This study evaluates the prevalence, associates, and clinical implication of pericardial involvement in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. Its main findings are as follows: (1) The prevalence of pericardial effusion in a cohort of hospitalized patients across all disease severity of COVID‐19 infection is around 14%. (2) Pericardial effusion is associated with COVID‐19 severity, worse RV systolic function, and elevated BNP, but rarely with acute pericarditis or myocardial injury. (3) Pericardial effusion is associated with excess mortality. (4) Combining assessment for pericardial effusion with a simple focused echocardiographic evaluation (LVEF and TAPSE) is a strong predictor of outcome in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 infection.

Prevalence and Associates of Pericardial Effusion

The association of pericardial disease with infections was first reported in 1933. 29 Since then, it was described in various viral infections, with Enteroviruses, Coxsackie, and Herpesviruses being the most common. 23 , 30 The data on pericardial disease in other coronaviruses are scarce and based only on case reports. 10 , 31 Our data show that in consecutive hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 infection, the prevalence of pericardial effusion was nearly 15%, but only 17 of 530 (3.2%) had pericarditis. Several recent small prospective studies in critically ill patients with COVID‐19 11 , 12 , 13 have described a prevalence ranging from 43% to 90% for pericardial effusion. Other publications have dealt with the prevalence and clinical impact of pericardial effusion in acute COVID‐19 infection. 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 However, all these reports were either retrospective or based on systematic literature review, assessing only patients with clinically indicated echocardiographic examinations. Our study used a prospectively defined protocol and included unselected hospitalized patients encompassing all grades of disease severity, which can better evaluate the prevalence and clinical impact of pericardial effusion in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. Recently, Brito et al 32 studied the presence of pericardial inflammation in a small cohort of 54 athletes recovering from COVID‐19 infection. Although 39.5% had pericardial late enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, only 6% had associated pericardial effusion by echocardiography. The possible reasons for the lower prevalence of pericardial effusion compared with the present cohort are the younger age of patients, milder disease (all athletes were not hospitalized, and had either mild or asymptomatic disease), and performing the echocardiography at a later stage (around 28 days after COVID‐19 diagnosis).

A large retrospective trial reported a pericarditis prevalence of 1.5% in patients with COVID‐19 in the United States based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10), diagnosis codes. 20 The use of retrospective data and diagnosis codes, in contrast to the present study, may contribute to underestimation of the prevalence of pericarditis in patients with COVID‐19.

Surprisingly, the prevalence of pericarditis in patients with pericardial effusion was low, and neither CRP nor troponin‐I levels were associated with pericardial effusion. The data suggest that pericardial or myocardial inflammation does not play a major role in the cause of pericardial effusion in patients with COVID‐19 infection.

Outcome

Hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 infection and pericardial effusion had a worse outcome compared with patients without pericardial effusion in nonadjusted analysis. There are several possible mechanisms for pericardial involvement in patients with COVID‐19. These include direct viral injury to the myocardium, extending to the pericardium; activation of exaggerated inflammatory response to the viral infection with secondary myocardial and pericardial involvement; acute respiratory distress syndrome, resulting in cardiac hypoxic injury extending to the pericardium; or hypoxia causing pulmonary hypertension, leading to pericardial effusion. 8 , 10 Mechanisms related to secondary injury are implied by our data, showing pericardial effusion in patients with COVID‐19 infection is strongly associated with worse pulmonary disease and RV dysfunction, as well as with elevated BNP. Thus, we believe that a pericardial effusion is usually a surrogate marker of more severe COVID‐19 infection. More important, although several case reports have shown that pericardial effusions may deteriorate to tamponade, 16 , 18 causing direct hemodynamic compromise and death, this is extremely rare, and was not the mechanism of mortality in any one of the patients. In multivariate analysis adjusted for clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic parameters, pericardial effusion was marginally associated with mortality in hospitalized patients. In a previous work, we were able to show that noninvasive echocardiographic hemodynamic parameters, such as low forward flow, high left and right filling pressures, and high RV afterload, are strongly associated with mortality. 33 , 34 This emphasized the importance of obtaining Doppler‐based hemodynamic parameters in patients with severe COVID‐19 infection. However, at the same time, we showed that in patients with mild disease, or low MEWS, mortality is low, irrespective of hemodynamic parameters. Thus, to decrease the risk of exposure, we recommended complete hemodynamic evaluation only when clinically indicated, or in patients with high MEWS. In the present work, we demonstrate that once comprehensive noninvasive hemodynamic evaluation is performed, pericardial effusion has only marginal additive value for predicting mortality. However, once limited echocardiography is performed, simple evaluation for the presence of pericardial effusion has significant additive predictive value in hospitalized patients.

Focused Cardiac Ultrasound and Clinical Implications

Recent documents published by the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography recommended a focused cardiac ultrasound approach in patients with COVID‐19. 24 , 35 In a previous work, 33 we found that a limited echocardiographic evaluation, including only TAPSE and LVEF, provides valuable information for clinical management. Recent advances in ultrasound technology have led to the miniaturization of machines to the size of a mobile telephone, which do not provide spectral Doppler functions. 36 We show that in the context of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19, assessment for presence of pericardial effusion, combined with LVEF and TAPSE from the 4‐chamber view alone, carries significant prognostic data, on top of clinical evaluation and risk scores. This may further help risk stratify patients with COVID‐19 in a reality of overwhelmed health systems.

Study Limitations

This single‐center study included only hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. The fact that only a minority of patients with COVID‐19 are admitted to the hospital may lead to overestimation of the prevalence and clinical impact of pericardial effusion in COVID‐19. Furthermore, the presence of preexisting pericardial effusion cannot be excluded, resulting in possible overestimation of the true incidence of pericardial effusion. Eighty patients were excluded because they had “do not resuscitate/intubate” orders and thus received palliative care and died shortly after admission without echocardiographic assessment. This may create an opposite bias, resulting in underestimation of the prevalence and impact of pericardial effusion in patients with COVID‐19. Pre–COVID‐19 echocardiograms were not evaluated, and some of the findings may have preceded COVID‐19 infection. Echocardiography was performed by cardiologists with expertise in echocardiography using a mobile system and not a pocket‐size handheld device. Thus, our hypothesis about the use of handheld devices for limited examinations should serve as an incentive to explore this concept in dedicated prospective series.

Conclusions

In a large prospective cohort of consecutive hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 infection encompassing the entire spectrum of disease severity, pericardial effusion is common, but rarely is attributable to acute pericarditis or myocarditis. Nevertheless, it is associated with myocardial dysfunction and excess mortality. To achieve significant clinical value for risk stratification, a limited echocardiographic examination, including LVEF, TAPSE, and evaluation for presence of pericardial effusion, is sufficient.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from NOVARTIS Israel Ltd.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S2

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.024363

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

References

- 1. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Kim R, Jerome KR, Nalla AK, Greninger AL, Pipavath S, Wurfel MM, Evans L, et al. Covid‐19 in critically Ill patients in the Seattle region — case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C, Hui DSC, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, Sayer G, Griffin JM, Masoumi A, Jain SS, Burkhoff D, Kumaraiah D, Rabbani L, et al. COVID‐19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Szekely Y, Lichter Y, Taieb P, Banai A, Hochstadt A, Merdler I, Gal Oz A, Rothschild E, Baruch G, Peri Y, et al. Spectrum of cardiac manifestations in COVID‐19: a systematic echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2020;142:342–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pournazari P, Spangler AL, Ameer F, Hagan KK, Tano ME, Chamsi‐Pasha M, Chebrolu LH, Zoghbi WA, Nasir K, Nagueh SF. Cardiac involvement in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 and its incremental value in outcomes prediction. Sci Rep. 2021;11:19450. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98773-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, Wang H, Wan J, Wang X, Lu Z. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kermani‐Alghoraishi M, Pouramini A, Kafi F, Khosravi A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and severe pericardial effusion: from pathogenesis to management: a case report based systematic review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46:100933. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2021.100933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diaz‐Arocutipa C, Saucedo‐Chinchay J, Imazio M. Pericarditis in patients with COVID‐19: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Med. 2021;22:693–700. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Furqan MM, Verma BR, Cremer PC, Imazio M, Klein AL. Pericardial diseases in COVID19: a contemporary review. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23:90. doi: 10.1007/s11886-021-01519-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu Y, Xie J, Gao P, Tian R, Qian H, Guo F, Yan X, Song Y, Chen W, Fang L, et al. Swollen heart in COVID‐19 patients who progress to critical illness: a perspective from echo‐cardiologists. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:3621–3632. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duerr GD, Heine A, Hamiko M, Zimmer S, Luetkens JA, Nattermann J, Rieke G, Isaak A, Jehle J, Held S, et al. Parameters predicting COVID‐19‐induced myocardial injury and mortality. Life Sci. 2020;260:118400. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doyen D, Dupland P, Morand L, Fourrier E, Saccheri C, Buscot M, Hyvernat H, Ferrari E, Bernardin G, Cariou A, et al. Characteristics of cardiac injury in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2021;159:1974–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tung‐Chen Y. Acute pericarditis due to COVID‐19 infection: an underdiagnosed disease? Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;155:44–45. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2020.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fox K, Prokup JA, Butson K, Jordan K. Acute effusive pericarditis: a late complication of COVID‐19. Cureus. 2020;12:e9074. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Asif T, Kassab K, Iskander F, Alyousef T. Acute pericarditis and cardiac tamponade in a patient with covid‐19: a therapeutic challenge. EJCRIM. 2020;7:001701. doi: 10.12890/2020_001701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, Cani DS, Cerini M, Farina D, Gavazzi E, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:819–824. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hua A, O’Gallagher K, Sado D, Byrne J. Life‐threatening cardiac tamponade complicating myo‐pericarditis in COVID‐19. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2130. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li K, Wu J, Wu F, Guo D, Chen L, Fang Z, Li C. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID‐19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 2020;55:327–331. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buckley BJR, Harrison SL, Fazio‐Eynullayeva E, Underhill P, Lane DA, Lip GYH. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of myocarditis and pericarditis in 718,365 COVID‐19 patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021;51:e13679. doi: 10.1111/eci.13679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liao X, Wang B, Kang Y. Novel coronavirus infection during the 2019–2020 epidemic: preparing intensive care units—the experience in Sichuan Province, China. Int Care Med. 2020;46:357. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05954-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lichter Y, Topilsky Y, Taieb P, Banai A, Hochstadt A, Merdler I, Gal Oz A, Vine J, Goren O, Cohen B, et al. Lung ultrasound predicts clinical course and outcomes in COVID‐19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1873–1883. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06212-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Barón‐Esquivias G, Bogaert J, Brucato A, Gueret P, Klingel K, Lionis C, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2921–2964. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirkpatrick JN, Mitchell C, Taub C, Kort S, Hung J, Swaminathan M. ASE statement on protection of patients and echocardiography service providers during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3078–3084. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf FA, Gillebert TC, Klein AL, Lancellotti P, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:277–314. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Topilsky Y, Khanna AD, Oh JK, Nishimura RA, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Jeon YB, Sundt TM, Schaff HV, Park SJ. Preoperative factors associated with adverse outcome after tricuspid valve replacement. Circulation. 2011;123:1929–1939. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.991018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kitabatake A, Inoue M, Asao M, Masuyama T, Tanouchi J, Morita T, Mishima M, Uematsu M, Shimazu T, Hori M, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of pulmonary hypertension by a pulsed Doppler technique. Circulation. 1983;68:302–309. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.68.2.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bing HI. Epidemical pericarditis. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 1933;80:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koontz CH, Ray CG. The role of Coxsackie group B virus infections in sporadic myopericarditis. Am Heart J. 1971;82:750–758. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(71)90195-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Al‐Abdallat MM, Payne DC, Alqasrawi S, Rha B, Tohme RA, Abedi GR, Al Nsour M, Iblan I, Jarour N, Farag NH, et al. Hospital‐associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1225–1233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brito D, Meester S, Yanamala N, Patel HB, Balcik BJ, Casaclang‐Verzosa G, Seetharam K, Riveros D, Beto RJ, Balla S, et al. High prevalence of pericardial involvement in college student athletes recovering from COVID‐19. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szekely Y, Lichter Y, Hochstadt A, Taieb P, Banai A, Sapir O, Granot Y, Lupu L, Merdler I, Ghantous E, et al. The predictive role of combined cardiac and lung ultrasound in coronavirus disease 2019. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2021;34:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taieb P, Szekely Y, Lupu L, Ghantous E, Borohovitz A, Sadon S, Lichter Y, Ben‐Gal Y, Banai A, Hochstadt A, et al. Risk prediction in patients with COVID‐19 based on haemodynamic assessment of left and right ventricular function. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22:1241–1254. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeab169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Skulstad H, Cosyns B, Popescu BA, Galderisi M, Salvo GD, Donal E, Petersen S, Gimelli A, Haugaa KH, Muraru D, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and cardiac imaging: EACVI recommendations on precautions, indications, prioritization, and protection for patients and healthcare personnel. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21:592–598. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cardim N, Dalen H, Voigt J‐U, Ionescu A, Price S, Neskovic AN, Edvardsen T, Galderisi M, Sicari R, Donal E, et al. The use of handheld ultrasound devices: a position statement of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (2018 update). Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:245–252. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S2