Abstract

Background

Elevated plasma ceramides are independent predictors of cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with advanced epicardial coronary artery disease. Our understanding of plasma ceramides in early epicardial coronary artery disease, however, remains limited. We examined the role of plasma ceramides in early coronary atherosclerosis characterized by coronary endothelial dysfunction.

Methods and Results

Participants presenting with chest pain and nonobstructive epicardial coronary artery disease underwent coronary endothelial function. Patients (n=90) demonstrated abnormal coronary endothelial function with acetylcholine (≥20% decrease in coronary artery diameter or ≤50% increase in coronary blood flow). A total of 30 controls had normal coronary endothelial function. Concentrations of plasma ceramide 18:0 (P=0.038), 16:0 (P=0.021), and 24:0 (P=0.019) differed between participants with normal and abnormal coronary endothelial function. Ceramide 24:0 (odds ratio [OR], 2.23 [95% CI, 1.07–4.66]; P=0.033) and 16:0 (OR, 1.91×106 [95% CI, 11.93–3.07×1011]; P=0.018) were independently associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction. Among participants with endothelium‐dependent coronary dysfunction (n=78), ceramides 16:0 (OR, 5.17×105 [95% CI, 2.83–9.44×1010]; P=0.033), 24:0 (OR, 2.98 [95% CI, 1.27–7.00]; P=0.012), and 24:1/24:0 (OR, 4.39×10−4 [95% CI, 4×10−7–0.48]; P=0.030) were more likely to be elevated.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated an association between increased circulating ceramide levels and coronary endothelial dysfunction in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease. This study supports the role of plasma ceramides as a potential biomarker or a therapeutic target for early coronary atherosclerosis in humans.

Keywords: ceramides, coronary artery disease, endothelial dysfunction

Subject Categories: Endothelium/Vascular Type/Nitric Oxide, Biomarkers, Coronary Artery Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ΔCAD,

change in coronary artery diameter;

- ΔCBF

change in coronary blood flow

- CED

coronary endothelial dysfunction

- CFR

coronary flow reserve

- MACE

major adverse cardiac events

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Plasma ceramide levels are elevated in humans with early coronary atherosclerosis and coronary endothelial dysfunction in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Circulating ceramides may be a biomarker and therapeutic target for early coronary atherosclerosis in humans.

Early coronary atherosclerosis is characterized by coronary endothelial dysfunction (CED). CED occurs within epicardial arteries and subsequent downstream high‐resistance arterial networks that regulate the myocardial blood supply and perfusion. 1 Coronary atherogenesis at its earliest stages segmentally disrupts the endothelial landscape. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 This often diagnostically occult progression of CED evolves to manifest clinically with eventual ventricular dysfunction, myocardial ischemia, increased mortality, and increased risk for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Thus, identification of nontraditional risk factors for early coronary atherosclerosis has been an area of increasing clinical and academic interest.

An emerging nontraditional risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis has been identified among known biologically active lipid species. Circulating long‐chain and very‐long‐chain sphingolipids affect functional and structural processes associated with endothelial dysfunction through oxidative, thrombotic, inflammatory, apoptotic, and atherogenic pathways. Theoretically these observations may translate to the progression of coronary artery disease in humans; however, our current understanding of the direct mechanism underlying the influence of ceramide (Cer) on human coronary atherogenesis relies predominantly on animal and ex vivo studies. 11 , 12 At present, investigations in humans focus on clinical observations and outcomes. Literature supports a strong association between elevated concentrations in plasma ceramides and advanced coronary atherosclerosis with an emphasis on the strong predictive association between plasma ceramide concentrations and cardiovascular risk. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

Although studies in humans are currently limited by indirect observations, clinical investigation of individual acyl chain species concentrations sheds light on our understanding of their possible independent roles in the progression of coronary disease. Emerging evidence suggests the role of circulating ceramides in various pathways of atherogenesis with predominant associations between ceramide 18:0, ceramide 16:0, and ceramide 24:1 and their respective roles in the inflammatory, thrombotic, and low‐density lipoprotein (LDL)–mediated pathways of atherogenesis. The association of these circulating ceramide acyl species in late coronary atherosclerosis is now robustly described; however, our understanding of the role ceramide acyl species may play in humans with very early coronary disease remains limited. 12 , 13 , 17 , 20 , 21 , 22 The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that elevated levels of circulating plasma ceramides are associated with CED. In this case‐control analysis, we examine the relationship between plasma ceramides and a range of coronary function abnormalities associated with early coronary atherosclerosis.

Methods

Ethical Statement

Supporting data are available from corresponding author upon reasonable request. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Participants

Consecutive randomly selected patients presenting for clinically indicated coronary angiographic evaluation of chest pain and coronary arteries with <40% obstruction (n=1991) between the years 1992 and 2019 were reviewed. Patients with abnormal CED (n=90) were randomly selected and defined as participants with abnormal coronary endothelial function. These participants had either (1) >20% constriction change in coronary artery diameter following intracoronary acetylcholine injection indicating epicardial endothelial dysfunction or (2) a ≤50% increase change in coronary blood flow (ΔCBF) indicating microvascular endothelial dysfunction. 6 , 23 Eligible participants underwent indicated angiogram and routine blood sample collection in 2019. Controls (n=30) had normal coronary endothelial function testing and were propensity matched by age and sex.

Endothelial Function Testing

A detailed methodology has been previously published. 24 , 25 , 26 Briefly, patients presenting for clinically indicated angiography underwent invasive coronary function testing. Participants had not received oral nitrates, lipid‐lowering drugs, antioxidants, or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors for 2 weeks before intervention. Other medications such as calcium‐channel blockers or β‐adrenergic blockers were discontinued at least 48 hours before the interventional study. Diagnostic coronary angiography was then performed to assess epicardial coronary artery, microvascular endothelium, and microvascular endothelium‐independent function in concordance with the International Microcirculation Working Group expert review. 27 Participants with significant obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease (defined as >40% coronary diameter stenosis) were excluded. During angiography of eligible participants, a Doppler guidewire (FloWire; Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) was advanced to the mid‐portion of the left anterior descending coronary artery.

To assess nonendothelium microvascular function, incremental doses of intracoronary adenosine (18 µg–72 µg) were administrated as consecutive boluses until maximal hyperemia was observed. Endothelium‐independent microvascular function was determined by highest observed coronary flow reserve (CFR) in response to increasing doses of intracoronary adenosine.

Endothelium dependent function was assessed by 3 consecutive boluses of acetylcholine in the mid‐left anterior descending coronary artery at 3‐minute intervals with increasing concentrations of 10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 mmol/L. After each dose of acetylcholine, a single operator measured the diameter of the mid‐left anterior descending coronary artery 5‐mm distal to the Doppler wire tip with a coronary angiogram tool (Medis Cor, Leiden, The Netherlands). We calculated coronary blood flow=Π (mean peak velocity/2)×(coronary artery diameter/2)2. The ΔCBF, a measure of microvascular function, was calculated as the percentage difference between coronary blood flow at basal flow and maximal hyperemia after acetylcholine injection. We defined microvascular CED as <50% increase in coronary blood flow after intracoronary acetylcholine infusion. We defined endothelium‐independent microvascular dysfunction as CFR <2.0.

Clinical and Biochemical Data

Demographic data were obtained at the time of coronary angiography. 5 , 28 Conventional cardiovascular risk factors were obtained from medical records, including associated comorbidities, smoking status, body mass index, glomerular filtration rate, and pharmacologic therapy. Comorbidities were defined as follows: diabetes was defined as a documented comorbidity and/or use of hypoglycemic agents, hypertension was defined as a documented comorbidity and/or use of antihypertensive agents, hyperlipidemia was defined as elevated lipid laboratory data and/or use of lipid‐lowering agents. Blood samples were obtained within 2 weeks before angiography. Routine laboratory analysis (lipid profile, hs‐CRP [high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein]) and cytokine measurement was performed. Frozen plasma specimens stored in EDTA collected from fasting participants before coronary angiography were analyzed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. The following ceramide acyl chain species were selected based on their association with cardiovascular risk: ceramide 18:0, ceramide 16:0, ceramide 24:0, ceramide 24:1, and ratios of each with ceramide 24:0. 13 , 17 , 18 Ceramide concentrations obtained by mass spectrometry were examined for significant confounding outlier data. Among participants, there were significant outliers identified in ceramide 16:0, ceramide 24:01, and ceramide 24:1/24:0 (n=6, n=4, n=1, respectively), which were excluded from further analysis. No significant outliers were observed among other ceramide acyl species (Figure S1).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were listed as mean±SD when data are normally distributed and median with interquartile range when data are skewed. Demographic, clinical, angiographic, and lipid data were compared between participants with and without CED with an unpaired t test. Correlations were examined between plasma ceramides and sex, age, hs‐CRP, and inflammatory markers (IL [interleukin]‐2, IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐10, IFNγ [interferon γ], and TNFα [tumor necrosis factor α]). An unpaired t test examined plasma ceramide levels between patients who were and were not treated with lipid‐lowering therapy. The independent association of each plasma ceramide was then assessed by a multivariable regression analysis with 3 separate variables used to characterize CED: percentage ΔCBF, ΔCAD and CFR. Regressions were adjusted by 3 consecutive models for factors known to affect cardiovascular risk and potential lipid confounders. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex; model 2 was further adjusted for hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and lipid‐lowering drug use; and model 3 was further adjusted for LDL and non–high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. A receiver operating characteristic curved assessed the predictive accuracy of plasma ceramide concentrations in predicting CED. Area under the curve (AUC) assessed discrimination of CED by plasma ceramide species. A subgroup analysis of participants with endothelial‐dependent vascular dysfunction (defined by CFR >2) was conducted in the same manner. Data were analyzed using Stata software (StataCorp. 2017; Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp LLC., College Station, TX).

Results

Ceramides and CED

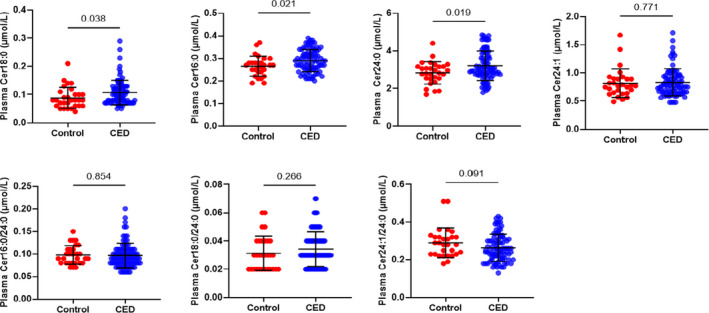

Between participants with and without CED, there was no significant difference in demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). Table 2 summarizes Measures obtained by coronary angiograph and serum lipid data of patients undergoing elective angiography for chest pain Participants with CED had a median CFR of 2.5 (2.2; 2.9), median ΔCBF of −1.74 (−32; 24), and median ΔCAD of −25 (−39; −11). Controls had a median CFR of 3.2 (2.8; 3.7), median ΔCBF of 114 (89; 161), and median ΔCAD of −4 (−11; 1). There was a significant difference in all 3 of these physiologic measures that characterize CED between the patient and control groups. Between participants with normal coronary endothelial function and those with CED, we observed a significant difference in plasma concentrations of ceramides 18:0 (P=0.038), 16:0 (P=0.021), and 24:0 (P=0.019) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable |

Patients* (n=90) |

Controls* (n=30) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 56±10 | 57±9 | 0.944 |

| Female sex | 67 (74) | 24 (80) | 0.542 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30±6 | 28±5 | 0.410 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 122 (112; 138) | 120 (112; 130) | 0.447 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 77 (70; 82) | 74 (70; 80) | 0.520 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoked | 55 (61) | 17 (57) | 0.912 |

| Former smoker | 31 (34) | 10 (33) | 0.912 |

| Current smoker | 4 (4) | 3 (10) | 0.265 |

| Hypertension | 38 (42) | 15 (50) | 0.462 |

| Diabetes | 11 (12) | 4 (13) | 0.875 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 54 (60) | 14 (47) | 0.205 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 73 (64; 82) | 74 (61; 92) | 0.967 |

| Aspirin use | 58 (64) | 19 (63) | 0.913 |

| β‐blocker use | 42 (47) | 9 (30) | 0.116 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 48 (53) | 12 (40) | 0.209 |

| Antihypertensive use | 29 (32) | 11 (37) | 0.658 |

BMI indicates body mass index; and eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Data are presented as number (percentage), mean±SD, or median (interquartile range).

Table 2.

Coronary Angiography and Lipid Data

| Variable | Patients* | n | Controls* | n | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFR | 2.5 (2.2; 2.9) | 90 | 3.2 (2.8; 3.7) | 30 | <0.000 |

| ΔCBF, % | −1.74 (−32; 24) | 90 | 114 (89; 161) | 30 | <0.000 |

| ΔCAD, % | −25 (−39; −11) | 90 | −4 (−11; 1) | 30 | <0.000 |

| Myocardial infarction–heart ceramide risk score | 3 (2; 6) | 90 | 2.5 (1; 4) | 30 | |

| Risk category | |||||

| Higher risk | 1 (1) | 90 | 1 (3) | 30 | 0.415 |

| Increased risk | 13 (14) | 90 | 4 (13) | 30 | 0.881 |

| Moderate risk | 36 (40) | 90 | 15 (50) | 30 | 0.749 |

| Lower risk | 36 (40) | 90 | 15 (50) | 30 | 0.341 |

| Lipid profile | |||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 181 (164; 207) | 88 | 177 (160; 208) | 29 | 0.693 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 101 (83; 123) | 88 | 100 (84.5–107.5) | 29 | 0.494 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 56 (43; 64) | 88 | 58 (46; 76) | 29 | 0.587 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 109 (83; 141) | 87 | 107 (74.5; 131) | 29 | 0.671 |

| Plasma ceramides | |||||

| 18:0, μmol/L | 0.10 (0.08; 0.13) | 90 | 0.08 (0.06; 0.10) | 30 | 0.038 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | 0.29 (0.25; 0.33) | 86 | 0.27 (0.24; 0.28) | 28 | 0.021 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.78 (0.66; 0.95) | 90 | 0.77 (0.65; 0.90) | 30 | 0.771 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 3.05 (2.73; 3.85) | 87 | 2.82 (2.54; 3.16) | 29 | 0.019 |

| 16:0/24:0 | 0.09 (0.08; 0.11) | 90 | 0.10 (0.08; 0.11) | 30 | 0.854 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 0.03 (0.03; 0.04) | 90 | 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) | 30 | 0.266 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 0.25 (0.21; 0.31) | 89 | 0.28 (0.23–0.32) | 29 | 0.091 |

ΔCAD indicates change in coronary artery diameter; ΔCBF, change in coronary blood flow; CFR, coronary flow reserve; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; and LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Data are presented as number (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

Figure 1. Ceramide levels in patients with and without CED.

CED indicates coronary endothelial dysfunction; and Cer, ceramide.

We observed no difference in plasma ceramide levels between women (n=91) and men (n=29; Table 3). When we isolated patients with coronary endothelium‐dependent dysfunction (CFR >2), there remained no difference in plasma ceramide concentrations by sex (Table 4). No significant correlation between plasma ceramides and age was observed (Table 5).

Table 3.

Plasma Ceramide Levels by Sex

| Plasma ceramide | Female sex* | n | Male sex* | n | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18:0, μmol/L | 0.09 (0.07; 0.12) | 91 | 0.10 (0.08; 0.13) | 29 | 0.365 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | 0.27 (0.25; 0.32) | 87 | 0.28 (0.24; 0.31) | 27 | 0.844 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.77 (0.66;0.94) | 90 | 0.82 (0.74; 0.92) | 29 | 0.374 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 2.69 (2.69; 3.38) | 90 | 3.09 (2.79; 3.88) | 26 | 0.414 |

| 16:0/24:0 | 0.09 (0.08; 0.11) | 91 | 0.09 (0.08; 0.11) | 29 | 0.996 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) | 91 | 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) | 29 | 0.506 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 0.26 (0.22; 0.31) | 90 | 0.25 (0.21; 0.32) | 28 | 0.795 |

*Data are presented as median (interquartile range).

Table 4.

Plasma Ceramide Levels by Sex in Patients With Coronary Endothelial Dysfunction

| Plasma ceramide | Female sex* | n | Male sex* | n | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18:0, μmol/L | 0.09 (0.08; 0.13) | 67 | 0.11 (0.07; 0.13) | 23 | 0.787 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | 0.29 (0.25; 0.33) | 64 | 0.29 (0.25; 0.31) | 22 | 0.664 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.76 (0.66; 0.96) | 67 | 0.83 (0.74; 0.94) | 23 | 0.381 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 3.00 (2.69; 3.71) | 66 | 3.11 (2.85; 3.88) | 21 | 0.570 |

| 16:0/24:0 | 0.09(0.08; 0.11) | 67 | 0.09 (0.08; 0.11) | 23 | 0.814 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 0.03 (0.03; 0.04) | 67 | 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) | 23 | 0.955 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 0.25 (0.21; 0.31) | 67 | 0.24 (0.20; 0.34) | 22 | 0.825 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range).

Table 5.

Correlation Between Plasma Ceramides and Age

| Plasma ceramide | Correlation with age |

|---|---|

| 18:0, μmol/L | 0.08 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | 0.05 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.09 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 0.04 |

| 16:0/24:0 | 0.05 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 0.13 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 0.11 |

Correlation coefficients for circulating plasma ceramides and age.

Plasma hs‐CRP data were available for 100 participants. We did not observe a strong correlation between hs‐CRP and plasma ceramides (Table 6). Exploring this further, a linear regression controlled for age and sex showed no significant association between hs‐CRP and plasma ceramides (Table 7).

Table 6.

Correlation Between Plasma Ceramides and hs‐CRP

| Plasma ceramide | Correlation with hs‐CRP |

|---|---|

| 18:0, μmol/L | 0.17 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | 0.02 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.13 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 0.06 |

| 16:0/24:0 | −0.03 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 0.14 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 0.08 |

Correlation coefficients for circulating concentrations of ceramides and hs‐CRP. hs‐CRP indicates high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein.

Table 7.

Linear Association Between Plasma Ceramides and High‐Sensitivity C‐Reactive Protein

| Plasma ceramide | Standardized β coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 18:0, μmol/L | 6.20 | 0.088 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | −0.01 | 0.998 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.82 | 0.209 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 0.23 | 0.294 |

| 16:0/24:0 | −1.51 | 0.807 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 19.46 | 0.139 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 1.22 | 0.825 |

Linear regression is controlled for age and sex.

Inflammatory data were available for 58 participants. We did not observe a significant correlation between plasma ceramides and other inflammatory markers (IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐10, IFNγ, TNFa; Table 8). There was a significant difference in plasma ceramide 18:0/24:0 levels (P=0.037) between patients who were and were not treated with lipid‐lowering agents (Table 9).

Table 8.

Correlation Between Plasma Ceramides and Inflammatory Markers

| Plasma ceramide | IL‐2 | IL‐4 | IL‐5 | IL‐6 | IL‐8 | IL‐10 | IFNγ | TNFα |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18:0 0, μmol/L | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.23 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| 16:0 0, μmol/L | −0.08 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 |

| 24:1 0, μmol/L | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.22 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.09 |

| 16:0/24:0 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.06 |

| 18:0/24:0 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.09 |

| 24:1/24:0 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.08 |

Correlation coefficients for circulating inflammatory markers and plasma ceramides. IFNγ indicates interferon γ; IL, interleukin; and TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

Table 9.

Plasma Ceramide Levels Stratified by the Use of Lipid‐Lowering Therapy

| Plasma ceramide | No lipid therapy* (n=60) | Lipid‐lowering therapy* (n=60) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18:0, μmol/L | 0.08 (0.07; 0.12) | 0.10 (0.07; 0.13) | 0.096 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | 0.29 (0.26; 0.35) | 0.28 (0.24; 0.31) | 0.305 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.78 (0.69; 0.93) | 0.77 (0.63; 0.96) | 0.813 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 3.05 (2.73; 3.87) | 2.93 (2.68; 3.43) | 0.950 |

| 16:0/24:0 | 0.09 (0.08; 0.11) | 0.09 (0.08; 0.11) | 0.337 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) | 0.03 (0.03; 0.04) | 0.037 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 0.25 (0.22; 0.31) | 0.26 (0.21; 0.32) | 0.620 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range).

Table 10 summarizes linear regression models adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors and confounding lipids. When adjusted for cardiovascular comorbidities, LDL cholesterol, and non‐HDL cholesterol, lower CFR was associated with elevated circulating ceramides 18:0/24:0 (β, −12.8; P=0.016), 16:0/24:0 (β, −5.57; P=0.015), and 24:1/24:0 (β, −1.74; P=0.022). There was no linear association between change in epicardial coronary artery diameter or coronary blood flow in response to acetylcholine and circulating plasma ceramide levels.

Table 10.

Association Between Plasma Ceramides and CFR

| Adjusted model | Standardized β coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.170 |

| Sex | −0.20 | 0.116 |

| Plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 | −9.78 | 0.034 |

| 2 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.169 |

| Sex | −0.22 | 0.108 |

| Hypertension | 0.09 | 0.426 |

| Diabetes | −0.06 | 0.718 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −0.04 | 0.757 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 0.02 | 0.869 |

| Plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 | −9.88 | 0.040 |

| 3 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.114 |

| Sex | −0.19 | 0.180 |

| Hypertension | 0.06 | 0.599 |

| Diabetes | −0.01 | 0.964 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −0.02 | 0.873 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | −0.01 | 0.961 |

| LDL cholesterol | −0.01 | 0.115 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 0.01 | 0.097 |

| Plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 | −12.80 | 0.016 |

| 1 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.123 |

| Sex | −0.19 | 0.148 |

| Plasma ceramides 16:0/24:0 | −5.35 | 0.014 |

| 2 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.162 |

| Sex | −0.22 | 0.115 |

| Hypertension | 0.07 | 0.560 |

| Diabetes | −0.06 | 0.741 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −0.07 | 0.637 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | −0.03 | 0.803 |

| Plasma ceramides 16:0/24:0 | 0.016 | |

| 3 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.091 |

| Sex | −0.19 | 0.185 |

| Hypertension | 0.03 | 0.783 |

| Diabetes | −0.02 | 0.941 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −0.05 | 0.735 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | −0.05 | 0.761 |

| LDL cholesterol | −0.00 | 0.454 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | −0.00 | 0.405 |

| Plasma ceramides 16:0/24:0 | −5.57 | 0.015 |

| 1 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.154 |

| Sex | −0.20 | 0.117 |

| Plasma ceramides 24:1/24:0 | −1.38 | 0.044 |

| 2 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.175 |

| Sex | −0.23 | 0.094 |

| Hypertension | 0.10 | 0.409 |

| Diabetes | −0.06 | 0.727 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −0.06 | 0.671 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | −0.02 | 0.878 |

| Plasma ceramides 24:1/24:0 | −1.42 | 0.044 |

| 3 | ||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.113 |

| Sex | −0.20 | 0.164 |

| Hypertension | 0.06 | 0.613 |

| Diabetes | −0.02 | 0.908 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −0.02 | 0.888 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | −0.08 | 0.601 |

| LDL cholesterol | −0.01 | 0.140 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 0.01 | 0.146 |

| Plasma ceramides 24:1/24:0 | −1.74 | 0.022 |

Linear regression models consecutively adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors and lipids. HDL indicates high‐density lipoprotein; and LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Table 11 summarizes significant multivariable logistic regressions progressively adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, lipid‐lowering drug use, LDL cholesterol, and non‐HDL cholesterol. In each progressive model, ceramides 24:0 (OR, 2.23 [95% CI, 1.07–4.66,]; P=0.033) and 16:0 (OR, 1.91×106 [95% CI, 11.93–3.07×1011]; P=0.018) remained independently associated with CED. When adjusted for age and sex, ceramide 18:0 (OR, 7.26×105 [95% CI, 1.32–3.99×1011]; P=0.045) was independently associated with CED, but not when further adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors, LDL cholesterol, and non‐HDL cholesterol. Ceramides 24:1, 18:0/24:0, 16:0/24:0, and 24:1/24:0 were not associated with CED.

Table 11.

Association Between Circulating Plasma Ceramides and CED

| Adjusted model | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | 0.819 |

| Sex | 0.82 | 0.29–2.31 | 0.704 |

| Plasma ceramide 18:0, μmol/L | 7.26×105 | 1.32–3.99×1011 | 0.045 |

| 2 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.95–1.04 | 0.897 |

| Sex | 0.85 | 0.28–2.59 | 0.777 |

| Hypertension | 0.61 | 0.25–2.59 | 0.285 |

| Diabetes | 0.75 | 0.20–2.88 | 0.677 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.25 | 0.43–3.63 | 0.679 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.50 | 0.55–4.04 | 0.428 |

| Plasma ceramide 18:0, μmol/L | 4.73×105 | 0.49–4.55×1011 | 0.063 |

| 3 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.96 –1.05 | 0.875 |

| Sex | 0.76 | 0.25–2.35 | 0.640 |

| Hypertension | 0.69 | 0.27–1.75 | 0.439 |

| Diabetes | 0.68 | 0.17–2.74 | 0.592 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.00 | 0.30–3.30 | 0.996 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.82 | 0.57–5.87 | 0.311 |

| LDL cholesterol | 1.03 | 0.99–1.08 | 0.154 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 0.97 | 0.93–1.01 | 0.182 |

| Plasma ceramide 18:0, μmol/L | 1.10×107 | 0.87–1.40×1014 | 0.052 |

| 1 | |||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | 0.824 |

| Sex | 0.69 | 0.23–2.10 | 0.516 |

| Plasma ceramide 24:0, μmol/L | 2.12 | 1.10–4.08 | 0.024 |

| 2 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.95–1.05 | 0.940 |

| Sex | 0.80 | 0.24–2.65 | 0.716 |

| Hypertension | 0.51 | 0.19–1.34 | 0.172 |

| Diabetes | 0.82 | 0.21–3.29 | 0.783 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.22 | 0.40–3.75 | 0.723 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.84 | 0.64–5.29 | 0.255 |

| Plasma ceramide 24:0, μmol/L | 2.33 | 1.15–4.72 | 0.019 |

| 3 | |||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 0.804 |

| Sex | 0.76 | 0.23–2.53 | 0.658 |

| Hypertension | 0.57 | 0.21–1.54 | 0.268 |

| Diabetes | 0.77 | 0.19–3.10 | 0.709 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.09 | 0.33–3.63 | 0.892 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.86 | 0.56–6.16 | 0.309 |

| LDL cholesterol | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | 0.908 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | 0.938 |

| Plasma ceramide 24:0, μmol/L | 2.23 | 1.07–4.66 | 0.033 |

| 1 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | 0.956 |

| Sex | 0.61 | 0.20–1.84 | 0.377 |

| Plasma ceramide 16:0, μmol/L | 7.64×104 | 4.71–1.24×109 | 0.023 |

| 2 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | 0.868 |

| Sex | 0.67 | 0.20–2.27 | 0.521 |

| Hypertension | 0.48 | 0.18–1.27 | 0.139 |

| Diabetes | 0.88 | 0.22–3.56 | 0.859 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.30 | 0.41–4.07 | 0.658 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.69 | 0.57–5.02 | 0.342 |

| Plasma ceramide 16:0, μmol/L | 3.06×105 | 7.64–1.22×10 t | 0.019 |

| 3 | |||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.97–1.07 | 0.565 |

| Sex | 0.65 | 0.19–1.07 | 0.489 |

| Hypertension | 0.54 | 0.20–1.43 | 0.214 |

| Diabetes | 0.79 | 0.19–3.28 | 0.750 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.28 | 0.38–4.35 | 0.689 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.54 | 0.46–5.13 | 0.481 |

| LDL cholesterol | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | 0.922 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 0.99 | 0.96–1.03 | 0.736 |

| Plasma ceramide 16:0, μmol/L | 1.91×106 | 11.93–3.07×1011 | 0.018 |

Logistic regression models consecutively adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors and lipids. HDL indicates high‐density lipoprotein; and LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Ceramides and Endothelial‐Dependent Vascular Dysfunction

To assess the relationship between plasma ceramide levels and endothelial function exclusively, we excluded individuals with non‐endothelium‐dependent CFR defined as CFR ≤2. A subanalysis isolating patients with predominant endothelial‐dependent vascular dysfunction (n=78) was then performed with the same age‐matched and sex‐matched controls (n=30) without CED (Table 12).

Table 12.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Participants With Normal Endothelial Function and Endothelium‐Dependent Dysfunction

| Variable |

Patients* (n=78) |

Controls* (n=30) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 54±10 | 57±9 | 0.839 |

| Female sex | 59 (76) | 24 (80) | 0.634 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30±6 | 28±5 | 0.274 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 125±17 | 120 (112; 130) | 0.540 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 76±9 | 74 (70; 80) | 0.638 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoked | 50 (64) | 17 (57) | 0.800 |

| Former smoker | 24 (31) | 10 (33) | 0.800 |

| Current smoker | 4 (5) | 3 (10) | 0.362 |

| Hypertension | 32 (59) | 15 (50) | 0.404 |

| Diabetes | 10 (13) | 4 (13) | 0.944 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 47 (60) | 14 (47) | 0.206 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 75±15 | 74 (61; 92) | 0.681 |

| Aspirin use | 50 (64) | 19 (63) | 0.941 |

| β‐blocker use | 37 (47) | 9 (30) | 0.103 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 41 (53) | 12 (40) | 0.246 |

| Antihypertensive use | 23 (29) | 11 (37) | 0.476 |

BMI indicates body mass index; and eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Data are presented as number (percentage), mean±SD, or median (interquartile range).

A 2‐tailed t test demonstrated a significant difference in the levels of plasma ceramides 16:0 (P=0.038), 24:0 (P=0.01), and 24:1/24:0 (P=0.011) between the patient and control groups (Table 13). A linear regression adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors and confounding lipids examining the independent association of plasma ceramides and CED was performed using the previously described 3 models. Restricted change in coronary artery diameter in response to acetylcholine was associated with high circulating levels of ceramide 18:0/24:0 when adjusted for age, sex, and cardiovascular comorbidities (β, −418; P=0.020), but not when further adjusted for LDL cholesterol and non‐HDL cholesterol (Table 14). There was no linear association between change in coronary blood flow in response to acetylcholine and circulating plasma ceramide levels.

Table 13.

Coronary Angiography and Lipid Data of Participants With Normal Endothelial Function and Endothelium‐Dependent Dysfunction

| Variable | Patients* | n | Controls* | n | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFR | 2.7 (2.3–2.9) | 78 | 3.2 (2.8; 3.7) | 30 | <0.000 |

| ΔCBF, % | −8.7 (−34; 24) | 78 | 114 (89; 161) | 30 | <0.000 |

| ΔCAD, % | −27 (−40; −11) | 78 | −4 (−11; 1) | 30 | <0.000 |

| Myocardial infarction–heart ceramide risk score | 3.5 (2; 5) | 78 | 2.5 (1; 4) | 30 | |

| Risk category | |||||

| Higher risk | 1 (1) | 78 | 1 (3) | 30 | 0.483 |

| Increased risk | 8 (10) | 78 | 3 (10) | 30 | 0.919 |

| Moderate risk | 34 (44) | 78 | 11 (37) | 30 | 0.518 |

| Lower risk | 35 (45) | 78 | 15 (50) | 30 | 0.636 |

| Lipid profile | |||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 185 (165; 206) | 76 | 177 (160; 208) | 29 | 0.681 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 105 (84; 121) | 76 | 100 (84.5; 107.5) | 29 | 0.437 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 129 (103; 151) | 76 | 58 (46; 76) | 29 | 0.501 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 112 (82; 140) | 75 | 107 (74.5; 131) | 29 | 0.454 |

| Plasma ceramides | |||||

| 18:0, μmol/L | 0.09 (0.07; 0.13) | 78 | 0.08 (0.06; 0.10) | 30 | 0.060 |

| 16:0, μmol/L | 0.29 (0.25; 0.33) | 74 | 0.27 (0.24; 0.28) | 28 | 0.038 |

| 24:1, μmol/L | 0.77 (0.66; 0.94) | 78 | 0.77 (0.65; 0.78) | 30 | 0.945 |

| 24:0, μmol/L | 3.07 (2.78; 3.85) | 75 | 2.82 (2.54; 3.16) | 29 | 0.007 |

| 16:0/24:0 | 0.09 (0.08; 0.10) | 78 | 0.10 (0.08; 0.11) | 30 | 0.563 |

| 18:0/24:0 | 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) | 78 | 0.03 (0.02; 0.04) | 30 | 0.466 |

| 24:1/24:0 | 0.24 (0.20; 0.29) | 77 | 0.28 (0.23; 0.32) | 29 | 0.011 |

ΔCAD indicates change in coronary artery diameter; ΔCBF, change in coronary blood flow; CFR, coronary flow reserve; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; and LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Data are presented as number (percentage) or median (interquartile range).

Table 14.

Association Between Plasma Ceramides and Change in Coronary Artery Diameter in Study Participants With Endothelium‐Dependent Vascular Dysfunction (CFR >2)

| Adjusted model | Standardized β coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| Age | 0.44 | 0.032 |

| Sex | 10.20 | 0.033 |

| Plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 | −428.86 | 0.016 |

| 2 | ||

| Age | 0.53 | 0.011 |

| Sex | 9.25 | 0.056 |

| Hypertension | −4.68 | 0.262 |

| Diabetes | 9.44 | 0.149 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −5.12 | 0.378 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | −6.59 | 0.242 |

| Plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 | −418.38 | 0.020 |

| 3 | ||

| Age | 0.45 | 0.031 |

| Sex | 9.11 | 0.072 |

| Hypertension | −3.69 | 0.389 |

| Diabetes | 10.28 | 0.149 |

| Hyperlipidemia | −6.61 | 0.275 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | −2.53 | 0.676 |

| LDL cholesterol | 0.59 | 0.017 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | −0.51 | 0.020 |

| Plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 | −322.55 | 0.084 |

HDL indicates high‐density lipoprotein; and LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Table 15 details significant multivariable logistic regression models. We observed a significant association between elevated circulating ceramides 16:0 (OR, 5.17×105 [95% CI, 2.83–9.44×1010]; P=0.033), 24:0 (OR, 2.98 [95% CI, 1.27–7.00]; P=0.012), and 24:1/24:0 (OR, 4.39 ×10−4 [95% CI, 4×10−7–0.48]; P=0.030) and CED in all models progressively adjusted for age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, and confounding lipids. Ceramides 18:0, 24:1, 18:0/24:0, and 16:0/24:0 were not associated with CED.

Table 15.

Association Between Elevated Circulating Plasma Ceramides and Endothelium‐Dependent Vascular Dysfunction (CFR >2)

| Adjusted model | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.92–1.04 | 0.919 |

| Sex | 0.62 | 0.20–1.92 | 0.407 |

| Plasma ceramide 16:0, μmol/L | 3.05×104 | 1.79–5.20×108 | 0.038 |

| 2 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.95–1.05 | 0.996 |

| Sex | 0.70 | 0.20–2.43 | 0.573 |

| Hypertension | 0.46 | 0.17–1.23 | 0.123 |

| Diabetes | 0.93 | 0.22–3.84 | 0.917 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.50 | 0.45–4.96 | 0.511 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.36 | 0.43–4.31 | 0.595 |

| Plasma ceramide 16:0, μmol/L | 7.97×104 | 2.04–2.88×109 | 0.036 |

| 3 | |||

| Age | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 0.692 |

| Sex | 0.67 | 0.19–2.36 | 0.535 |

| Hypertension | 0.53 | 0.20–1.44 | 0.214 |

| Diabetes | 0.81 | 0.19–3.49 | 0.781 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.48 | 0.42–5.23 | 0.545 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.33 | 0.38––4.60 | 0.653 |

| LDL cholesterol | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 0.689 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 0.546 |

| Plasma ceramide 16:0, μmol/L | 5.17×105 | 2.83–9.44×1010 | 0.033 |

| 1 | |||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.94–1.03 | 0.564 |

| Sex | 0.77 | 0.25–2.44 | 0.664 |

| Plasma ceramide 24:0, μmol/L | 2.59 | 1.26–5.32 | 0.010 |

| 2 | |||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.94–1.04 | 0.664 |

| Sex | 0.98 | 0.28–3.42 | 0.973 |

| Hypertension | 0.45 | 0.16–1.22 | 0.117 |

| Diabetes | 1.06 | 0.24–4.55 | 0.942 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.25 | 0.38–4.16 | 0.715 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.71 | 0.54–5.38 | 0.362 |

| Plasma ceramide 24:0, μmol/L | 3.02 | 1.35–6.77 | 0.007 |

| 3 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.95–1.05 | 0.874 |

| Sex | 0.96 | 0.27–3.41 | 0.949 |

| Hypertension | 0.50 | 0.18–1.39 | 0.184 |

| Diabetes | 0.97 | 0.22–4.24 | 0.969 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.20 | 0.34–4.25 | 0.779 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.68 | 0.48–5.93 | 0.418 |

| LDL cholesterol | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 0.737 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 0.664 |

| Plasma ceramide 24:0, μmol/L | 2.98 | 1.27–7.00 | 0.012 |

| 1 | |||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | 0.804 |

| Sex | 0.93 | 0.32–2.70 | 0.888 |

| Plasma ceramides 24:1/24:0 | 4.63×10−4 | 8.80×10−7–0.24 | 0.016 |

| 2 | |||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | 0.759 |

| Sex | 1.06 | 0.34–3.31 | 0.921 |

| Hypertension | 0.54 | 0.21–1.41 | 0.212 |

| Diabetes | 0.76 | 0.19–3.08 | 0.702 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.93 | 0.60–6.24 | 0.272 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.27 | 0.41–3.90 | 0.676 |

| Plasma ceramides 24:1/24:0 | 3.65×10−4 | 5.64×10−7–0.24 | 0.017 |

| 3 | |||

| Age | 1.00 | 0.95–1.05 | 0.967 |

| Sex | 1.05 | 0.32–3.43 | 0.931 |

| Hypertension | 0.60 | 0.23–1.59 | 0.306 |

| Diabetes | 0.73 | 0.17–3.06 | 0.666 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.64 | 0.47–5.66 | 0.438 |

| Lipid‐lowering drug use | 1.28 | 0.37–4.44 | 0.698 |

| LDL cholesterol | 1.00 | 0.95–1.05 | 0.975 |

| Non‐HDL cholesterol | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | 0.949 |

| Plasma ceramides 24:1/24:0 | 4.39×10−4 | 4×10−7–0.48 | 0.030 |

HDL indicates high‐density lipoprotein; and LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Elevated Ceramides in the Prediction of CED

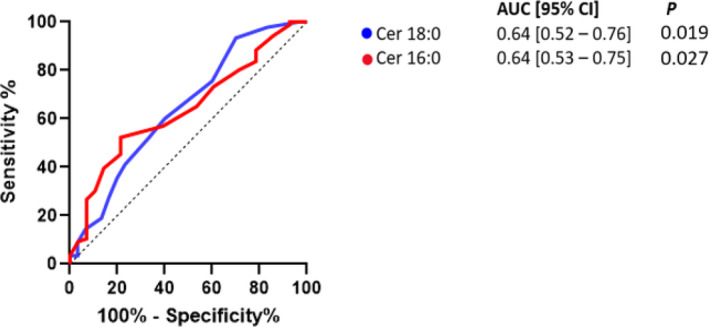

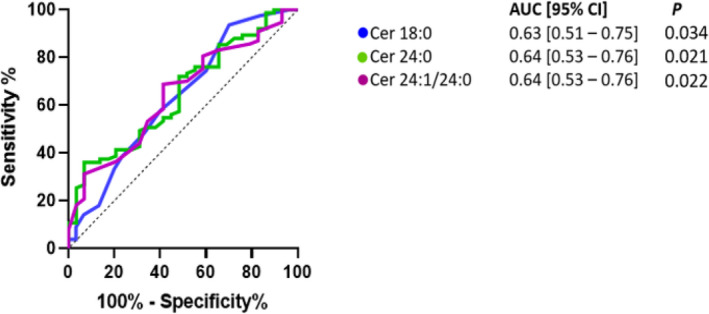

A receiver operating characteristic curve among all study participants suggested plasma ceramides 18:0 (AUC, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.52–0.76]; P=0.019) and 16:0 (AUC, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.53–0.75]; P=0.027) predicted CED with reasonable accuracy (Figure 2). Endothelial‐dependent coronary dysfunction was predicted with reasonable accuracy by plasma ceramides 18:0 (AUC, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.51–0.75]; P=0.034), 24:0 (AUC, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.53–0.76]; P=0.021), and 24:1/24:0 (AUC, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.53–0.76]; P=0.022; Figure 3). A receiver operator curve was not significant when combining subtypes of ceramide acyl species among all study participants (AUC, 0.53 [95% CI, 0.27–0.59]; P=0.360) and with endothelial‐dependent coronary dysfunction (AUC, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.44–0.59]; P=0.675).

Figure 2. Predictive assessment of plasma ceramides levels in coronary endothelial dysfunction.

AUC indicates area under the curve; and Cer, ceramide.

Figure 3. Predictive assessment of plasma ceramide levels in coronary endothelial dysfunction in patients with endothelium‐dependent dysfunction.

AUC indicates area under the curve; and Cer, ceramide.

Discussion

Summary of Findings

First, elevated levels of plasma ceramides 18:0, 24:0, and 16:0 are independently associated with early coronary atherosclerosis in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease. Second, higher plasma levels of circulating ceramides 18:0, 18:0/24:0, 16:0/24:0, and 24:1/24:0 are associated with abnormal microvascular function. Third, in participants with predominant endothelium‐dependent dysfunction, plasma ceramides 16:0, 24:0, and 24:1/24:0 are associated with CED. Thus, we present the first study associating elevated plasma ceramides with early coronary atherosclerosis. The current study supports a potential role of serum ceramides as a marker and a potential therapeutic target in early coronary atherosclerosis in humans.

Ceramides and Early Atherosclerosis

Despite our growing understanding of potential mechanisms and specific associations of individual ceramide acyl species and cardiovascular disease, literature associating individual ceramides with aspects of atherosclerosis remains largely inconsistent. 14 , 29 Scientists postulate that specific acyl species may be more associated with varying atherogenic pathways in humans–that is, ceramide is 18:0 associated with the inflammatory pathway, ceramide 16:0 is associated with the thrombotic pathway, and ceramide 24:1 is associated with the LDL pathway of atherogenesis. 11 , 17 , 29 , 30 In support of these associations, we present data that further suggest an association between elevated circulating ceramide 18:0 and ceramide 16:0 in humans with observed endothelial dysfunction related to early atherosclerosis. Furthermore, a linear association shows a positive association between hs‐CRP and circulating ceramide 18:0, which may be in part attributed to its role in the inflammatory pathway of atherosclerosis.

Studies examining the association between ceramide 24:0 and cardiovascular disease are widely inconsistent, and our overall understanding of their role in atherogenesis in humans remains limited; however, there may be a role in early atherosclerosis as alluded to by our findings. Traditionally, the abundant very‐long‐chain sphingolipid ceramide 24:0 has been measured to normalize other circulating ceramide species relative to its abundance. Interestingly, our findings suggest an inverse correlation between ceramide 24:0 and early coronary atherosclerosis. When we examine patients with endothelium‐dependent dysfunction (CFR >2), the normalized ratio ceramide 24:1/24:0 is further associated with early atherosclerosis, which may suggest the role of ceramides in the LDL pathway in these participants. We interpret these findings with the understanding that atherogenesis is a progressive and dynamic process over time and that these associations may be unique to participants with early coronary atherosclerosis.

Existing literature remains inconsistent regarding the specific consequence of elevated individual ceramides. Clinically, ceramide 16:0 has repeatedly been shown to be associated with recurrent MACE and acute coronary syndrome, whereas ceramide 18:0 appears to be associated with MACE alone. 16 , 21 , 31 , 32 The most inconsistent data exist for the association of circulating ceramide 24:0 and cardiovascular disease. Most large studies investigating the association between cardiovascular disease and ceramide 24:0 remain consistent and observe no association. 13 , 22 , 31 Few other studies suggest an inverse association between ceramide 24:0 and coronary atherosclerosis. An examination of ceramide 24:0 in patients from the Framingham Heart Study and Study of Health in Pomerania in participants with coronary artery disease observed the relative risk of coronary artery disease for each 3‐unit increase in ceramide 24:0 was 0.79 when adjusted for confounding lipids and cardiovascular risk factors. 19 Additional studies have supported that elevated levels of ceramide 24:0 may be associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular event in patients with preexisting coronary artery disease. 22 , 30 , 33 Our study interestingly finds a positive association between ceramide 24:0 in participants with early coronary atherosclerosis. Discrepancies in specific associations may be in part secondary to population selection (ie, healthy participants with stable coronary disease, participants with heart failure, population studies). Our particular cohort with early coronary disease and endothelial dysfunction remains unique and distinct from the populations, which likely underlie our specific findings.

Elevated Plasma Ceramides and Non‐Endothelium‐Dependent Dysfunction

The mechanistic role of ceramides in endothelial and microvascular dysfunction is likely multifactorial. Ceramides are biologically active lipids key to cell membrane integrity and are either synthesized de novo or transported by LDL into the endothelium where they facilitate various metabolic pathways. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 Notably, ceramides have been observed to mediate endothelium‐dependent flow‐induced dilation by facilitating the production of endothelium‐derived hydrogen peroxide rather than the preferred nitrous oxide. 38 Although this process may to an extent preserve flow‐induced dilation in an early atherosclerotic artery, hydrogen peroxide leads to adverse consequences to endothelial function over time. 39 , 40 , 41 In addition to the chemical consequence of these bioactive lipids, ceramides add structural consequence to arteries by progressively infiltrating plaque, further impairing microvascular function.

In early coronary artery disease, lower CFR is associated with higher levels of circulating plasma ceramides. Impaired non‐endothelium‐dependent dysfunction (typically when CFR <2.5) has been used as a marker to predict the development of cardiovascular events such as heart failure, chest pain, ischemia, recurrent hospitalizations, long‐term adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and acute coronary syndrome. 5 , 42 , 43 In our cohort with no coronary artery stenosis, impaired dilation represents non‐endothelium‐dependent dysfunction (typically when CFR <2.5). We found lower CFR to be associated with higher plasma levels of ceramides 18:0/24:0, 16:0/24:0, and 24:1/24:0. This association may be in part secondary to changes in endothelial reactive oxygen species related to vascular ceramide infiltration. Ceramide‐infiltrated endothelium favors hydrogen peroxide rather than physiologically preferred NO as a mediator of flow‐induced dilation. Compounded structural change of endothelium by early lipid infiltration further limits the dilatory capacity of coronary vessels and overall results in limited CFR. 44

Few other studies highlight the association of circulating ceramides and impaired vascular hemodynamics in early coronary disease. A prospective community‐based cohort study demonstrated decreased survival free of stroke and myocardial infarction participants with an average burden of coronary artery disease and elevated plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 (hazard ratio [HR], 3.00 [95% CI, 1.17–7.68]) and 24:1/24:0 (HR, 2.93 [95% CI, 1.52–5.67]). 21 Interestingly, ceramide 24:1/24:0 was identified in this study as a marker for high cardiovascular risk in patients with a low atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score. This highlights the suspicion that ceramides are not only constituents of obstructive plaque but are also drivers of endothelial disease, which carries a risk for adverse cardiac outcomes independent of coronary plaque burden. 17 , 20 , 21 , 45 In the The European Collaborative Project on Inflammation and Vascular Wall Remodeling in Atherosclerosis‐Intravascular Ultrasound study examining 581 patients with coronary artery disease, elevated plasma ceramide 16:0/24:0 was associated with vulnerable plaque characteristics determined by intravascular ultrasound and MACE. 46 Endothelial dysfunction is known to be associated with characteristics of vulnerable plaque. Although mounting clinical science increases our suspicion for ceramides as possible independent drivers of endothelial dysfunction and eventual coronary atherosclerosis, further direct investigation in humans is needed to support these observations. Our novel findings associate elevated circulating ceramides in a unique cohort of patients at the earliest detectable stages of coronary artery disease and emphasize their potential role in the contribution of impaired vascular hemodynamics.

Coronary Artery Diameter

We observe impaired coronary artery dilation related to elevated plasma ceramide levels. Change in coronary artery diameter in response to intracoronary administration of acetylcholine can be used to evaluate the endothelium‐dependent flow–diameter relationship of coronary arteries. A normal endothelial response to acetylcholine is vasodilation, whereas an abnormal response is either no change in coronary artery diameter or vasoconstriction. 47 This normal coronary vasodilation occurs under balanced circumstances. Intravascular acetylcholine acts on endothelial muscarinic receptors that facilitate smooth muscle vasoconstriction and endothelial‐mediated NO release; the summative effect in normal physiology is vessel dilation. In normal endothelium, this smooth muscle vasoconstriction is counteracted by NO‐mediated vasodilation, resulting in overall coronary dilation following acetylcholine exposure. If a coronary artery vasoconstricts following acetylcholine exposure, we presume that acetylcholine acts on smooth muscle muscarinic receptors to vasoconstrict in an environment unopposed by NO activity. The consequent imbalance signifies endothelial dysfunction. 12 Among patients with predominant endothelium‐dependent dysfunction, we observed an association between elevated levels of ceramides 18:0/24:0 and coronary artery dilation in response to intracoronary acetylcholine. These findings suggest endothelial cell rather than smooth muscle dysfunction. Recent evidence supports the potential role of ceramides 18:0/24:0 in advanced coronary atherosclerosis. Meeusen et al observed an association between elevated plasma ceramides 18:0/24:0 and MACE when adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors in participants undergoing nonurgent coronary angiography. Of these participants, 54% were observed to have obstructive coronary artery disease. 13 Our findings extend previous observations by highlighting an association between CED and specifically elevated plasma ceramide species implicated in adverse outcomes of advanced coronary disease.

Limitations

Several limiting factors of this case‐control analysis should be discussed. First, our retrospective analysis examined the clinical association between elevated plasma ceramides and early coronary atherosclerosis. We did not examine the biologic and pathophysiologic mechanisms that may underly these associations. Regarding angiographic evaluation, occult atherosclerosis not observed by the procedural operator may confound vascular hemodynamic data and may not be specific to microcirculation abstraction. The implications of the associations highlighted by this study require future validation. Lastly, in the current analysis, multiplicity control methodologies were not employed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we present evidence that supports the association between elevated plasma ceramides and early coronary atherosclerosis defined by endothelial dysfunction and absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. We speculate the mechanism of injury to be related to smooth muscle damage as suggested by our presented association of plasma ceramides and CFR. Emerging data further suggest systemic vascular implications of elevated plasma ceramide levels, including stroke. 48 , 49 , 50 Circulating plasma ceramides may be a novel therapeutic target and could be used to stratify risk. Emerging studies suggest therapies that reduce circulating plasma ceramides; however, further studies are required to determine the long‐term outcomes of ceramide‐lowering therapy on outcomes. 51 , 52 Further studies are needed to investigate the effects of lowering plasma ceramide levels in patients with CED on cardiovascular outcomes.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Mayo Foundation.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Figure S1

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 14.

References

- 1. Camici PG, Crea F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:830–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Godo S, Corban MT, Toya T, Gulati R, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Association of coronary microvascular endothelial dysfunction with vulnerable plaque characteristics in early coronary atherosclerosis. EuroIntervention. 2020;16:387–394. doi: 10.4244/eij-d-19-00265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Choi BJ, Prasad A, Gulati R, Best PJ, Lennon RJ, Barsness GW, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Coronary endothelial dysfunction in patients with early coronary artery disease is associated with the increase in intravascular lipid core plaque. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2047–2054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gössl M, Yoon MH, Choi BJ, Rihal C, Tilford JM, Reriani M, Gulati R, Sandhu G, Eeckhout E, Lennon R, et al. Accelerated coronary plaque progression and endothelial dysfunction: serial volumetric evaluation by IVUS. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sara JD, Widmer RJ, Matsuzawa Y, Lennon RJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Prevalence of coronary microvascular dysfunction among patients with chest pain and nonobstructive coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1445–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gutiérrez E, Flammer AJ, Lerman LO, Elízaga J, Lerman A, Fernández‐Avilés F. Endothelial dysfunction over the course of coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3175–3181. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herrmann J, Lerman A. The endothelium: dysfunction and beyond. J Nucl Cardiol. 2001;8:197–206. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2001.114148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suwaidi JA, Hamasaki S, Higano ST, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR Jr, Lerman A. Long‐term follow‐up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2000;101:948–954. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.9.948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marks DS, Gudapati S, Prisant LM, Weir B, diDonato‐Gonzalez C, Waller JL, Houghton JL. Mortality in patients with microvascular disease. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004;6:304–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.03254.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gdowski MA, Murthy VL, Doering M, Monroy‐Gonzalez AG, Slart R, Brown DL. Association of isolated coronary microvascular dysfunction with mortality and major adverse cardiac events: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of aggregate data. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014954. doi: 10.1161/jaha.119.014954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bismuth J, Lin P, Yao Q, Chen C. Ceramide: a common pathway for atherosclerosis? Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cogolludo A, Villamor E, Perez‐Vizcaino F, Moreno L. Ceramide and regulation of vascular tone. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:411. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meeusen JW, Donato LJ, Bryant SC, Baudhuin LM, Berger PB, Jaffe AS. Plasma ceramides. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:1933–1939. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.118.311199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tippetts TS, Holland WL, Summers SA. The ceramide ratio: a predictor of cardiometabolic risk. J Lipid Res. 2018;59:1549–1550. doi: 10.1194/jlr.C088377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mantovani A, Bonapace S, Lunardi G, Canali G, Dugo C, Vinco G, Calabria S, Barbieri E, Laaksonen R, Bonnet F, et al. Associations between specific plasma ceramides and severity of coronary‐artery stenosis assessed by coronary angiography. Diabetes Metab. 2020;46:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Carvalho LP, Tan SH, Ow G‐S, Tang Z, Ching J, Kovalik J‐P, Poh SC, Chin C‐T, Richards AM, Martinez EC, et al. Plasma ceramides as prognostic biomarkers and their arterial and myocardial tissue correlates in acute myocardial infarction. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hilvo M, Vasile VC, Donato LJ, Hurme R, Laaksonen R. Ceramides and ceramide scores: clinical applications for cardiometabolic risk stratification. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.570628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hilvo M, Wallentin L, Ghukasyan Lakic T, Held C, Kauhanen D, Jylhä A, Lindbäck J, Siegbahn A, Granger CB, Koenig W, et al. Prediction of residual risk by ceramide‐phospholipid score in patients with stable coronary heart disease on optimal medical therapy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015258. doi: 10.1161/jaha.119.015258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peterson LR, Xanthakis V, Duncan MS, Gross S, Friedrich N, Völzke H, Felix SB, Jiang H, Sidhu R, Nauck M, et al. Ceramide remodeling and risk of cardiovascular events and mortality. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7. doi: 10.1161/jaha.117.007931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meeusen JW, Donato LJ, Kopecky SL, Vasile VC, Jaffe AS, Laaksonen R. Ceramides improve atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment beyond standard risk factors. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;511:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vasile VC, Meeusen JW, Medina Inojosa JR, Donato LJ, Scott CG, Hyun MS, Vinciguerra M, Rodeheffer RR, Lopez‐Jimenez F, Jaffe AS. Ceramide scores predict cardiovascular risk in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:1558–1569. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.120.315530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laaksonen R, Ekroos K, Sysi‐Aho M, Hilvo M, Vihervaara T, Kauhanen D, Suoniemi M, Hurme R, März W, Scharnagl H, et al. Plasma ceramides predict cardiovascular death in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes beyond LDL‐cholesterol. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1967–1976. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taqueti VR, Di Carli MF. Coronary microvascular disease pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic options: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2625–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Widmer RJ, Flammer AJ, Herrmann J, Rodriguez‐Porcel M, Wan J, Cohen P, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Circulating humanin levels are associated with preserved coronary endothelial function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H393–H397. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00765.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cannon RO III. Does coronary endothelial dysfunction cause myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease? Circulation. 1997;96:3251–3254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmad A, Corban MT, Toya T, Sara JD, Lerman B, Park JY, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Coronary microvascular endothelial dysfunction in patients with angina and nonobstructive coronary artery disease is associated with elevated serum homocysteine levels. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017746. doi: 10.1161/jaha.120.017746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Widmer RJ, Samuels B, Samady H, Price MJ, Jeremias A, Anderson RD, Jaffer FA, Escaned J, Davies J, Prasad M, et al. The functional assessment of patients with non‐obstructive coronary artery disease: expert review from an international microcirculation working group. EuroIntervention. 2019;14:1694–1702. doi: 10.4244/eij-d-18-00982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Targonski PV, Bonetti PO, Pumper GM, Higano ST, Holmes DR Jr, Lerman A. Coronary endothelial dysfunction is associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events. Circulation. 2003;107:2805–2809. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000072765.93106.ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mah M, Febbraio M, Turpin‐Nolan S. Circulating ceramides‐ are origins important for sphingolipid biomarkers and treatments? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.684448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Song JH, Kim GT, Park KH, Park WJ, Park TS. Bioactive sphingolipids as major regulators of coronary artery disease. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2021;29:373–383. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2020.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Havulinna AS, Sysi‐Aho M, Hilvo M, Kauhanen D, Hurme R, Ekroos K, Salomaa V, Laaksonen R. Circulating ceramides predict cardiovascular outcomes in the population‐based FINRISK 2002 cohort. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2424–2430. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.116.307497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu J, Pan W, Shi R, Yang T, Li Y, Yu G, Bai Y, Schuchman EH, He X, Zhang G. Ceramide is upregulated and associated with mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sigruener A, Kleber ME, Heimerl S, Liebisch G, Schmitz G, Maerz W. Glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid species and mortality: the Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health (LURIC) study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bikman BT, Summers SA. Ceramides as modulators of cellular and whole‐body metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4222–4230. doi: 10.1172/jci57144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhou K, Blom T. Trafficking and functions of bioactive sphingolipids: lessons from cells and model membranes. Lipid Insights. 2015;8:11–20. doi: 10.4137/lpi.s31615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bartke N, Hannun YA. Bioactive sphingolipids: metabolism and function. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:S91–S96. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800080-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jadczyk T, Baranski K, Syzdol M, Nabialek E, Wanha W, Kurzelowski R, Ratajczak MZ, Kucia M, Dolegowska B, Niewczas M, et al. Bioactive Sphingolipids, complement cascade, and free hemoglobin levels in stable coronary artery disease and acute myocardial infarction. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2018/2691934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Freed JK, Beyer AM, LoGiudice JA, Hockenberry JC, Gutterman DD. Ceramide changes the mediator of flow‐induced vasodilation from nitric oxide to hydrogen peroxide in the human microcirculation. Circ Res. 2014;115:525–532. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.115.303881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1014–R1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00124.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cai H. NAD(P)H oxidase‐dependent self‐propagation of hydrogen peroxide and vascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;96:818–822. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163631.07205.fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brandes RP, Kreuzer J. Vascular NADPH oxidases: molecular mechanisms of activation. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nakanishi K, Fukuda S, Shimada K, Miyazaki C, Otsuka K, Maeda K, Miyahana R, Kawarabayashi T, Watanabe H, Yoshikawa J, et al. Impaired coronary flow reserve as a marker of microvascular dysfunction to predict long‐term cardiovascular outcomes, acute coronary syndrome and the development of heart failure. Circ J. 2012;76:1958–1964. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tsukamoto O, Kitakaze M. Reserve of coronary flow deserves predictor of cardiovascular events. Circ J Japan. 2012;76:1834–1835. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weil BR, Canty JM Jr. Ceramide signaling in the coronary microcirculation: a double‐edged sword? Circ Res. 2014;115:475–477. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Poss AM, Maschek JA, Cox JE, Hauner BJ, Hopkins PN, Hunt SC, Holland WL, Summers SA, Playdon MC. Machine learning reveals serum sphingolipids as cholesterol‐independent biomarkers of coronary artery disease. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:1363–1376. doi: 10.1172/jci131838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheng JM, Suoniemi M, Kardys I, Vihervaara T, de Boer SPM, Akkerhuis KM, Sysi‐Aho M, Ekroos K, Garcia‐Garcia HM, Oemrawsingh RM, et al. Plasma concentrations of molecular lipid species in relation to coronary plaque characteristics and cardiovascular outcome: results of the ATHEROREMO‐IVUS study. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Horio Y, Yasue H, Rokutanda M, Nakamura N, Ogawa H, Takaoka K, Matsuyama K, Kimura T. Effects of intracoronary injection of acetylcholine on coronary arterial diameter. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:984–989. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90743-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ighodaro ET, Graff‐Radford J, Syrjanen JA, Bui HH, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr, Zuk SM, Vemuri P, Mielke MM. Associations between plasma ceramides and cerebral microbleeds or lacunes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:2785–2793. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.120.314796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gui YK, Li Q, Liu L, Zeng P, Ren RF, Guo ZF, Wang GH, Song JG, Zhang P. Plasma levels of ceramides relate to ischemic stroke risk and clinical severity. Brain Res Bull. 2020;158:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2020.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fiedorowicz A, Kozak‐Sykała A, Bobak Ł, Kałas W, Strządała L. Ceramides and sphingosine‐1‐phosphate as potential markers in diagnosis of ischaemic stroke. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2019;53:484–491. doi: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2019.0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ye Q, Svatikova A, Meeusen JW, Kludtke EL, Kopecky SL. Effect of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors on plasma ceramide levels. Am J Cardiol. 2020;128:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tarasov K, Ekroos K, Suoniemi M, Kauhanen D, Sylvänne T, Hurme R, Gouni‐Berthold I, Berthold HK, Kleber ME, Laaksonen R, et al. Molecular lipids identify cardiovascular risk and are efficiently lowered by simvastatin and PCSK9 deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E45–E52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1